Abstract

Objective

Loneliness and psychological distress are serious challenges for older adults to cope with and factors threatening life quality and happiness during their remaining years. Older people’s attitudes and evaluations towards loneliness potentially affect psychological distress. Therefore, the current study aimed to examine the relationship between the stigma of loneliness and the psychological distress of older adults, further exploring the mediating effect of distress disclosure and loneliness.

Methods

Conducted during February and March 2024, the questionnaire survey included 933 older adults (age 65–89) using the Stigma of Loneliness Scale (SLS), Distress Disclosure Index (DDI), UCLA Loneliness scale (ULS-6), and 6-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6). The obtained data were for descriptive statistical analysis, correlation analysis, and chain mediation model testing.

Results

Stigma of loneliness was significantly positively correlated with loneliness and psychological distress (r=0.61–0.69, p<0.01), and distress disclosure was negatively correlated with stigma of loneliness, loneliness, and psychological distress (r=−0.37–−0.48, p<0.01). Stigma of loneliness can not only directly affect the psychological distress of older adults (effect value=0.38), but also indirectly affect psychological distress through the mediating roles of distress disclosure (effect value=0.04) and loneliness (effect value=0.20), and the chain mediating effect of the two (effect value=0.05).

Conclusion

The study redounds to the in-depth understanding of the effect of the stigma of loneliness on psychological distress among older people and its internal mechanism. The research results contribute to theoretical reference in explaining the formation background of psychological distress among older cohorts, which intends to provide empirical evidence for intervention studies of reducing psychological distress.

Keywords: older adults, stigma of loneliness, psychological distress, distress disclosure, loneliness

Introduction

At present, the escalating aging tendency evolves into a pivotal challenge that calls for the collaboration of governments to correspond together.1 China has the largest older population in the world and the fastest aging tendency. According to data released by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, in 2010, there were 120 million people over the age of 65 in China, accounting for 8.87% of the total population, and in 2020, those over 65 exceeded 190 million, accounting for 13.50% of the total. Gradually, mental health problems of older adults receive more and more attention from scholars.2 Previous studies have found that older adults are at high risk of psychological distress, and depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia are the most common psychological problems.3,4 For instance, evidence from systematic review and meta-analysis shows more than 1/3 of older adults suffer from depression on a global scale, and the prevalence rate is rising year by year.5 In the past two decades, mental health problems have seen an increase among the Chinese older population, encompassing threats to the quality of life and well-being in later life.6,7

Older people may suffer constant loneliness after being plagued by experiencing cognitive function decline, unstable health conditions, depressing events (death of close relatives and friends), and shrinking or unmet income.8 As a recent study result pointed out, older adults have a higher level of loneliness than young and middle-aged cohorts based on the meta-analysis of research data from 106 countries.9 The stigma of loneliness reflects individuals’ attitudinal tendency and cognition evaluation towards loneliness. Current studies have expounded on the relationship between loneliness and psychological distress, however, the pronounced evidence of the impact of stigma of loneliness on psychological distress and its mechanism is less noted.3,10

The Relationship Between Stigma of Loneliness and Psychological Distress

The stigma of loneliness refers to stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination the old carried towards loneliness, along with internalizing and applying those stereotypes to one’s loneliness.11,12 For older adults, loneliness is a topic filled with susceptibility, stigmatization, and intractability, which in turn may bring on complicated emotional reactions including agony, shame, and wrath.13 A study showed that older people maintain a critical and negative attitude towards people who feel lonely and tend to attribute loneliness to negative behavior patterns and personality defects.14 In mainstream narratives, the role of social context factors played in the formation and maintenance of loneliness is largely ignored, and the impact of personal defects and lack of social skills on loneliness is overemphasized, thus leading to the prevalence of stigma.15 Loneliness is often depicted as a repulsive experience with negative emotions engaged in sorrow, boredom, fear, anxiety, desperation, and helplessness, as well as people who feel lonely are also subject to images of being shameful and problematic.16

When loneliness is regarded as a specific issue associated with aging and senility, older adults may suffer from aging discrimination and loneliness stigma as a result.17 Loneliness stigma is normally widespread among the older population accompanying its negative effects on cognition, emotion, and behaviors, thereinto, the rise of psychological distress is one of the typical consequences of loneliness stigma.18 The “Why try” stigma effect can contribute to explaining how stigma-related information affects individuals’ mental health. Self-stigma emerges once a person realizes stereotypes associated with loneliness, feels identified and then applies the stereotypes to oneself.19 The direct consequence triggered by self-stigma lies in the scope of decreased self-esteem and self-efficacy, potential concealment, social withdrawal, and ineffectiveness of the acts, which may threaten mental health20 That is to say, older adults may encounter declined self-esteem and social efficacy and even depression as stigma of loneliness levels up.21 Besides, self-devaluation and self-discrimination stemming from stigma are also influential precursors of psychological distress.22 As highlighted in social rank theory, feelings of defeat and entrapment are typical features leading to depression, and this feeling mainly stems from the individual’s belief that he or she is inferior to others.23

There is plenty of empirical evidence that supports the relationship between loneliness stigma and psychological distress.18 For instance, Fan et al found that loneliness stigma is positively and significantly correlated with shyness, social interaction anxiety, social phobia, and psychological distress, and negatively and significantly with self-esteem.24 The results of qualitative studies showed that older adults believe loneliness shares the meaning of aging, personal trouble, and cognitive and emotional sickness, encompassing subsequent feelings of unwanted, forgotten, abandoned, rejected, dumped, and hopeless.25,26 Following this, as the stigma of loneliness exacerbates, so does the likelihood of mental illness among older adults.

The Mediating Effect of Distress Disclosure

Distress disclosure is an individual’s tendency to disclose negative life events or psychological distress.27 It is propitious to improve the understanding and empathy of those around, which can lead to additional supportive resources and a reduction in psychological distress.28 People who conceal painful messages from others receive less assistance and support and may experience more psychological distress as time goes on.29,30 As pointed out in a systematic review, disclosure facilitates the release of negative and depressive emotions and the acquisition of belonging or togetherness, therefore, alleviating stress and depression symptoms.31 Moreover, in the counselling field, distress disclosure is utilized as an essential therapeutic approach, encouraging clients to express their distress verbally and nonverbally.32 For instance, expressive writing redounds to reduce physiological arousal towards emotionally charged memories, while suppression is related to unhealthy health conditions.33 Additionally, a longitudinal study discovered that expressive-disclosure group intervention can diminish depression and psychological distress and enhance life quality and health conditions.34

Research has already previously found that stigma is associated with a higher tendency to conceal and less distress disclosure in older adults.35 Stigma heightens individuals’ negative attitudes and expectations towards social support and increases their concern about negative consequences, which in turn reduces their discussion about their problems and avoids interpersonal contact.36,37 Furthermore, older adults are prone to take concealment as stigma management strategy, adopting methods of passive acceptance, patience, internalization of sentiment, or distraction to pull down the negative effect of loneliness.38 Barreto et al thought that individuals with high stigma of loneliness are more likely to attribute the causal factors of loneliness to intrinsic and uncontrollable facets and have a higher tendency to conceal loneliness and perceive a relatively intense stigma when they feel lonely.39 As a result, as the stigma of loneliness increases, the level of distress disclosure in older adults may decline. In addition, Qin et al found that stigma can reduce an individual’s disclosure self-efficacy, which in turn leads to decreased self-esteem and increased depression.40

The Mediating Effect of Loneliness

Loneliness, other than objective isolation, manifests itself as a kind of negative emotional experience stimulated by falling short of subjective expectations compared to one’s real quality and quantity of relationships.41 Loneliness is prevalent in people of different ages, especially in older people, who more frequently suffer loneliness.9 In tracking studies of adults over 50, it was found that people tend to regard loneliness as a feature of older people and that age stereotypes can exacerbate potential loneliness.42 A systematic evaluation showed that individual loneliness was influenced by psychological and social factors, among which internalized stigma, perceived discrimination, and low self-esteem were the predisposing factors of loneliness.43

Stigma raises individuals’ sense of rejection and feeling left out, and reduces the opportunity and motivation for social interaction, resulting in a lower sense of belonging and worse loneliness.5 The conceptualization model of stigma asserts that stigma is the majority of people in society or people with high power, who identify and mark a feature of a specific population with their status loss and devaluing discrimination.11 Therefore, under the influence of stigma, loneliness is derogated and devalued and people featured with loneliness are also marginalized and suffer from a higher degree of loneliness. Previous studies discovered that loneliness stigma is significantly positively associated with loneliness.18,24 Neves et al noted that loneliness stigma reduces the willingness to ask for assistance, resulting in the long-term existence of loneliness and the accumulation of negative emotions, imposing a continuing negative influence on mental health.25

Loneliness as a factor threatening the mental health of older adults is inclined to aggravate psychological distress.44,45 Compared to older adults who do not feel lonely, those who feel lonely have poorer resilience, perceived social support, cognitive ability, and sleep quality, higher stress and fear of aging and death, and worse mental health.46–48 In addition, loneliness can improve individual sensitivity to threatening signals, amplify external attribution biases, stimulate social withdrawal, and disrupt interpersonal communication as a consequence of enduring insufficient available social resources.49–51

Evidence from longitudinal studies suggested that loneliness is the leading factor variable of psychological distress in older adults.52 For instance, Yan et al found their loneliness can indirectly affect psychological distress through the mediation effect of perceived social support and perceived internal control.53 As pointed out in a Meta-Analysis, loneliness positively predicted depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, and negatively predicted general mental health, quality of life, well-being, sleep, and cognitive function.54 Thus, it was posited that a significant positive correlation between loneliness and psychological distress. Moreover, Fan et al found that there was a significant positive correlation between loneliness stigma, loneliness, and psychological distress.24 Corrigan et al noted that self-stigma can indirectly affect depression through the mediating role of unworthiness and incapability.55

The Chain Mediating Role of Distress Disclosure and Loneliness

According to the theory of social penetration theory, disclosure is the basis for individuals to construct and maintain social networks, and it is also a basic form of social exchange.56 Disclosure promotes the formation, maintenance, and development of intimate relationships, and can effectively reduce loneliness.57 As relationships develop deeper, the contents of both sides of the communication are more extensive and in-depth and gradually involve their distressful feelings or negative information.58 Studies have found that the individual disclosure of the distressful message is attuned to improve social support and diminish negative emotions.41 Furthermore, distress disclosure augments the chances for one to be noticed, understood, and helped by people around, contributing to obtaining appropriate support, thus enhancing the sense of social connection and reducing social loneliness.59 Korem noted that disclosure is a crucial skill for individuals to build friendships and shows a positive value in reducing loneliness.60

Some empirical evidence underscores the relationship between distress disclosure and loneliness.61 For instance, Chen et al found that self-disclosure can reinforce friendships, reducing loneliness.62 Bruno et al thought that disclosure plays a mediating role in the relationship between guilt and loneliness.63 Therefore, as distress disclosure strengthens, loneliness may also decline. Moreover, Keum et al found that feeling understood by others and loneliness played a chain mediator in the relationship between distress disclosure and psychological distress.64 Ho et al showed that loneliness and cyber victimization mediate in the effects of disclosure on psychological distress.65

Research Questions

In summary, this study constructed a chain mediation model (see Figure 1) based on the survey data of older adults over 65 years old to explore the relationship between stigma of loneliness and psychological distress, as well as the mediating role of distress disclosure and loneliness. The study aimed to provide empirical evidence to explain the underlying causes of psychological distress in older adults from the perspective of the stigma of loneliness and to provide a theoretical reference for the introduction of interventions. Hypotheses were raised as follows:

H1: loneliness stigma is significantly and positively correlated with the psychological distress of older adults.

H2: distress disclosure plays a mediating role in the relationship between stigma of loneliness and psychological distress in older adults.

H3: loneliness plays a mediating role in the relationship between loneliness stigma and psychological distress in older adults.

H4: the stigma of loneliness can indirectly affect psychological distress through the chain mediation effect of distress disclosure and loneliness.

Figure 1.

Theoretical hypothesis model diagram.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-seven systematically trained graduate and undergraduate students took advantage of their vacation time (from February to March 2024) to complete the current survey. The students majored in psychology, public health management, and clinical medicine. The survey took a convenience sampling approach and a snowball approach. The investigators were all members of the research group, had studied relevant courses, and had experience in conducting questionnaires. Before starting the survey, the researchers explained in detail to the investigators the purpose, importance, process, guidance and possible solutions to the problems encountered. At the end of the training, the investigators conducted a pre-survey of the older people in the vicinity of the school to familiarize themselves with the communication skills and to be proficient in conducting the survey. In the formal survey, they went to parks, communities, markets, universities for the aged, or villages in their hometowns or near schools to survey Chinese older adults who met the inclusion criteria. At the end of the survey, participants were asked to recommend other older adults who met the inclusion criteria to continuously expand the sampling. The survey covered 7 provinces in China, including Zhejiang, Shandong, Henan, Sichuan, Jilin, Guizhou, and Gansu. The investigators detailed the purpose of the survey and the confidentiality and anonymity of the data and obtained the informed consent of the participants. After the survey, the investigators thanked the participants and presented them with a small gift. This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jilin International Studies University (Approval No. JY202403006).

G*Power 3.1 was used to calculate the minimum sample size required for the study. The multiple linear regression analysis method was selected, and the effect size ƒ2 value was set to 0.15, the power value was 0.95, the α value was 0.001, and the output of minimum sample size was 208 people. The inclusion criteria for participants were: (1) age ≥ 65 years; (2) voluntarily participate in this survey; (3) no communication barriers, able to communicate normally; (4) No serious mental illness or clinical illness. The exclusion criteria were: (a) a clear refusal to participate in the survey; (b) cognitive impairment or memory impairment; (c) illiterate, unable to read or understand the content of the questionnaire; (d) there is a communication barrier. In the end, a total of 933 older adults were surveyed, including 441 males (74.56±5.37) and 492 females (73.24±5.40).

Measures

All the scales included in this study have been revised to Chinese, and the validity of the Chinese version of the scale has been verified in Chinese older adults. The scoring method, number of items and dimension division of the Chinese version of the scale are consistent with those of the original scale. In this study, the scores of each scale were calculated according to the scale description.

Stigma of Loneliness Scale (SLS)

The current study adopted the Chinese version of SLS developed by Ko et al to assess loneliness stigma in older adults.18 The Chinese version has shown favorable reliability and validity among college students and adults.24,66 The SLS of 10 items is scored on a 5-level scale and is divided into two dimensions: Self-Stigma of Loneliness and Public Stigma of Loneliness. Item example: “If I were lonely, I would feel ashamed” All items are scored positively, and the sum of the scores of each item is the total score. The possible range of scores on the scale is between 10 and 50. Higher scores indicate higher levels of loneliness stigma among older adults. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for the total scale and each dimension were 0.92, 0.89, and 0.90, respectively.

Distress Disclosure Index (DDI)

DDI was used to assess the propensity of older adults to voluntarily disclose negative emotions and feelings of distress.27 The Chinese version of the scale has been widely applied among older adults, adults, and various patient populations.30,67,68 Item example: “When I feel upset, I usually confide in my friends.” The scale consists of 12 items, which are scored on a 5-level scale, with some items being scored backwards. The possible range of scores on the scale is between 12 and 60. The higher the total score, the higher the degree to which the individual expresses distress disclosure. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.84.

UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-6)

The UCLA Loneliness scale was widely used to assess loneliness in people of all ages.69 The Chinese version of ULS-6 has shown favorable psychometric features in Chinese older adults.70 The scale consists of 6 items and is scored on a 4-point scale. Item example: “I feel left out”. The possible range of scores on the scale is between 6 and 24. Higher scores indicate higher levels of loneliness in older adults. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.79.

6-Item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6)

The psychological distress scale of two versions consisting of 6 or 10 items, could be used to evaluate mental health status in older adults.71 The effectiveness of the Chinese version of K6 has been verified in the older Chinese population.72 The scale consists of 6 items, which are scored on a 5-level scale and are scored as “0–4” respectively. Item example: “During the last 30 days, how often did you feel hopeless?”. The possible range of scores on the scale is between 0 and 24. The higher the score, the higher the level of psychological distress in the elderly. In the study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.89.

Data Analysis

We used SPSS 20.0 for descriptive statistical analysis, correlation analysis, and chain mediation model testing. Pearson correlation analysis aimed to investigate the correlation between stigma of loneliness, distress expression, loneliness, and psychological distress. In the chain mediation model, stigma of loneliness was seen as the independent variable, psychological distress as the dependent variable, distress disclosure and loneliness as the mediating variables, and gender, age, marital status, and education level as the control variables. All variables were normalized and calculated using Model 6 in PROCESS v4.0. The study used the Bootstrap method and repeated samples 5000 times to examine the effectiveness of the indirect path. If the 95% confidence interval does not include 0, the indirect path is significant.

Results

Common Method Bias Analysis

The study adopted Harman’s single-factor test to explore whether different variables meet common method biases. All variables were subjected to exploratory factor analysis with the results of factor analysis that were not rotated being examined.73 The results showed that the variance explanation rate of the first common factor is 26.80%, which is less than the critical value of 40%. These results indicated no serious common method biases in this study.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

The details of participants’ social demographic information are shown in Table 1. The mean and standard deviations of stigma of loneliness, distress disclosure, loneliness, and psychological distress in older adults are shown in Table 2. The results of Pearson correlation analysis (see Table 2) showed that loneliness stigma was significantly positively correlated with loneliness and psychological distress (r=0.61–0.69, p<0.01), and distress disclosure was negatively correlated with loneliness stigma, loneliness and psychological distress (r=−0.37–-0.48, p<0.01).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Information of Participants (n=933)

| n (M) | % (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 73.86 (65–89) | 5.43 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 441 | 47.27 |

| Female | 492 | 52.73 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 829 | 88.85 |

| Unmarried | 7 | 0.75 |

| Divorced or widowed | 97 | 10.40 |

| Education | ||

| Primary and below | 517 | 55.41 |

| Junior high school | 231 | 24.76 |

| High or vocational school | 124 | 13.29 |

| College | 27 | 2.89 |

| Undergraduate | 23 | 2.47 |

| Postgraduate | 11 | 1.18 |

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis Results for Each Variable (n=933)

| Range | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Stigma of loneliness | 10–46 | 22.61 | 7.84 | – | |||

| 2.Distress disclosure | 17–60 | 38.95 | 7.16 | −0.37** | – | ||

| 3. Loneliness | 6–21 | 12.16 | 3.32 | 0.61** | −0.48** | – | |

| 4.Psychological distress | 0–24 | 7.47 | 4.67 | 0.67** | −0.45** | 0.69** | – |

Note: **p<0.01.

Abbreviations: M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

Testing for the Chain-Mediating Model

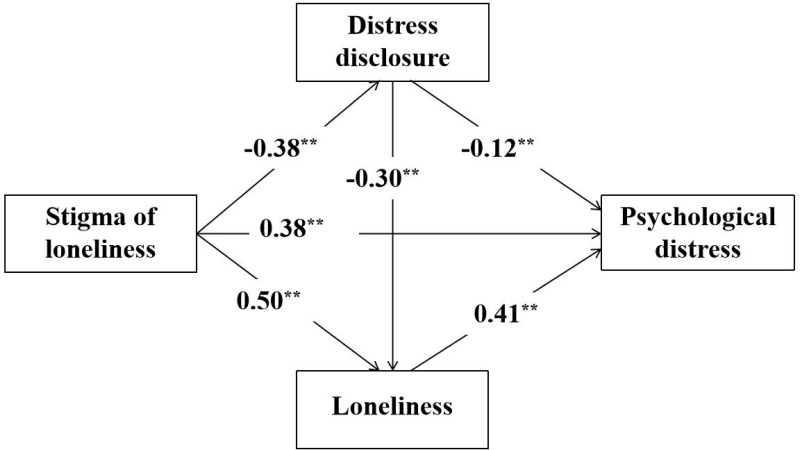

The results of the chain mediation model analysis (see Figure 2 and Table 3) showed that the total effect size of loneliness stigma on psychological distress in older adults was 0.668 and the path coefficient was significant (β=0.67, t=27.20, p<0.01) without adding mediating variables. After adding mediating variables, stigma of loneliness had a significant predictive effect on distress disclosure (β=−0.38, t=−12.47, p<0.01), loneliness (β=0.50, t=18.80, p<0.01), and psychological distress (β=0.38, t=13.91, p<0.01). In addition, distress disclosure had a significant predictive effect on loneliness (β=−0.30, t=−11.28, p<0.01) and psychological distress (β=−0.12, t=−4.67, p<0.01). Moreover, loneliness had a significant predictive effect on psychological distress (β=0.41, t=14.25, p<0.01).

Figure 2.

Diagram of the chain mediating effect model.

Note:**p<0.01.

Table 3.

Analysis Results of the Chain Mediation Model of Loneliness Stigma on Psychological Distress in Older Adults (n=933)

| Predictors | K6 | DDI | ULS-6 | K6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Gender | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.22 | 3.59** | 0.07 | 1.46 | 0.01 | 0.31 |

| Age | 0.01 | 1.26 | −0.01 | −1.41 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.96 |

| Marriage | 0.03 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 0.32 | −0.05 | −1.22 | 0.05 | 1.47 |

| Education | 0.02 | 0.72 | 0.03 | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.96 |

| SLS | 0.67 | 27.20** | −0.38 | −12.47** | 0.50 | 18.80** | 0.38 | 13.90** |

| DDI | −0.30 | −11.28** | −0.12 | −4.67** | ||||

| ULS-6 | 0.41 | 14.25** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.45 | 0.58 | ||||

| F | 148.18** | 34.13** | 126.00** | 184.90** | ||||

Note: **p<0.01.

Abbreviations: SLS, Stigma of loneliness scale; DDI, Distress disclosure index; ULS-6, UCLA Loneliness scale; K6, 6-item Kessler psychological distress scale; M, Mean; SD, Standard Deviation.

Furthermore, the Bootstrap method was used to calculate the significance of the indirect path of stigma of loneliness on psychological distress by repeated sampling 5000 times. The results showed (see Table 4) that stigma of loneliness could indirectly affect psychological distress through three pathways, and the 95% confidence interval of each path did not include 0. The total effect of stigma of loneliness on psychological distress in older adults was 0.67 and the indirect effect was 0.29, accounting for 43.71% of the total effect size.

Table 4.

Results of the Bootstrap Method of the Mediating Effect Test (n=933)

| Effect Size | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | Relative Mediation Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Total effect | 0.67 | 0.03 | 0.62 | 0.72 | |

| Direct effect | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 56.72% |

| Indirect effect | 0.29 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 43.28% |

| Stigma of loneliness→ Distress disclosure → Psychological distress | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 5.97% |

| Stigma of loneliness→ Loneliness → Psychological distress | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 29.85% |

| Stigma of loneliness→ Distress disclosure → Loneliness→ Psychological distress | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 7.46% |

Discussions

At present, China’s older population exceeds 20% of the total population, which indicates that China has entered a moderately aging society. To achieve the goal of active aging, we need to pay attention not only to the physical health and sleep quality of the cohort but also to their mental health, social health, and cognitive function.74 Their mental health has been one of the many issues that lie in critical focus areas. To reveal the impact of stigma of loneliness on the psychological distress of older adults and its mechanism, this study constructed a chain mediation model based on the “why try” effect of stigma, the conceptualization model, and the theory of social penetration. The study found that in the influence of the stigma of loneliness on the psychological distress of older adults, distress disclosure and loneliness played a chain mediating role.

The study found that distress disclosure mediates the relationship between stigma of loneliness and psychological distress in older adults. The “Why try” effect suggests that there is a complex interplay between distress disclosure and stigma.19 As the theory suggested, individuals may both intentionally reduce distress disclosure due to concerns about stigmatization and negative outcomes, and take disclosure as an effective strategy to cope with stigma.75 The results of this study showed that stigma can inhibit people’s expression of negative information and feelings about themselves. Older adults experience hopelessness, emptiness, failure, self-blame, guilt, and shame as a result of their loneliness, however, fearful of the consequences of disclosure, tend to conceal and endure distress rather than reveal their true feelings.21 Mianzi, a concept that is rooted in Chinese culture, refers to a person obtaining prestige and reputation by playing a particular role or presenting success through interpersonal contact.76 What differs from Western honor and dignity cultures is that individuals’ Mianzi is approached from cooperation in the society featured with a stable and rigid hierarchy.77 Since Mianzi is endowed by others and society, the Chinese feel reluctant to share their dilemmas with others to avoid losing Mianzi or social status.78 Hence, as loneliness is strengthened, older people may be prone to associate loneliness with Mianzi loss and reduce their disclosure to others. Furthermore, under the influence of loneliness stigma, older adults actively choose to reduce their exposure to avoid others’ blame for failure, frailty, and debility, as well as negative self-evaluation, which unfortunately and potentially leads to psychological distress.13

In the current study, loneliness plays a mediating role in the relationship between stigma of loneliness and psychological distress in older adults. Loneliness is often accompanied by a series of negative and unrecognized labels, existing obvious stigma.74 An important factor that makes it difficult to escape loneliness is the stigma of loneliness.10 Mann et al noted that changing negative perceptions and working to reduce stigma are effective interventions for loneliness.79 The current results of this study are consistent with Mann et al, suggesting that the stigma of loneliness plays an important role in the formation and intervention of loneliness in older adults. According to the “Why Try” effect, the most typical harm brought by stigma is declined self-esteem and self-efficacy.55 Stigma can give rise to undermined confidence in improving relationships and reducing loneliness, a debilitating sense of competence and worth in achieving goals, and feelings of hopelessness and helplessness.80 Thus, as the stigma of loneliness exacerbates, the levels of self-esteem, self-efficacy, hope, and social support in older adults also decline, which is detrimental to the acquisition and maintenance of interpersonal relationships and leads to higher levels of loneliness.81,82 In addition, long-term loneliness can impair executive functioning and cognitive abilities in older adults, increase sensitivity to negative cues, and disrupt interpersonal relationships, thereby, causing heightened psychological distress.83

The study discovered that distress disclosure and loneliness play a chain mediating role in the impact of stigma of loneliness on psychological distress in the aged. The results suggest that the stigma label associated with loneliness reduces people’s motivation to exposure (such as loneliness experiences and distressful feelings), which is not conducive to the availability of supportive resources and the alleviation of loneliness, aggravating psychological distress. In most previous studies, distress disclosure has been regarded as an effective way to develop intimate relationships, cope with stress, and solve problems, ending with promoting mental health.84 The current study concluded similarly that distress disclosure is propitious to the reduction of loneliness and psychological distress. However, there is a certain risk that talking over distress information may cause individuals to be susceptible to feeling vulnerable, embarrassed, rejected, mocked, excluded, criticized, or disappointed in not getting the desired result, which will exacerbate loneliness and psychological distress.85,86 The effectiveness of distress disclosure may depend on cultural or contextual factors. For instance, compared with their Western counterparts, Asian people are easily affected by the multi-facets of fear of losing Mianzi, maintenance of relationships, and humble characters, less expressing self-pains to others.87 Moreover, the advantages attached to the disclosure of painful information vary in different cultural contexts.88 Therefore, the aged should keep their eyes on specific context and characteristics of those being targeted to disclose with.

This study surveyed older adults to explore the relationship between stigma of loneliness and psychological distress and its mechanism, which in turn contributes certain theoretical significance. First, this study applied the “Why try” effect to the field of stigma of loneliness to explain the formation mechanism of psychological distress in the aged, expanding the application scope of this theory. Second, combined with the theory of social penetration and the conceptualization model of stigma, this study incorporated distress disclosure and loneliness into the mediation model, revealing how loneliness stigma affects the psychological distress of older adults, which can theoretically be referenced for potential interventions. Third, what older adults have suffered comes not only solely from the effect of stigma of loneliness but also from other types of stigma, which function in conjunction together to threaten mental health. Furthermore, previous literature stated that the mental health of older adults is a product of multiple factors such as age, marriage status, economic income, number of children, family relationships, social media usage, and physiological health.89–91 The results of the current study manifest an efficient supplement of studies in the field of stigma and mental health, facilitating the unveiling of the influential factors of the mental health of older adults.

A certain practical value is embedded in the study results. First, the results discuss the potential factors and mechanisms that affect mental health in older adults with the lens focused on the social context in which Chinese governments, corresponding to aging issues, have put efforts into constructing a positive aging society and set maintenance and reinforcement of older people’s mental health as a critical goal. As shown in the results, the intervention practice is necessary to focus on older adults’ loneliness and their attitude towards loneliness, to encourage them to take appropriate ways of expressing negative feelings to others and to obtain social support promptly for reducing psychological distress.

Second, the results verified that distress disclosure is positively valued in reducing loneliness and psychological distress, which can be theoretical support for the formulation of intervention programs based on distress disclosure and provide empirical evidence for the application of distress disclosure in counselling psychology.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

It is noteworthy that there are some limitations. First, the study mainly relies on existing theoretical and empirical evidence to construct the relationship between variables and takes a cross-sectional study design to verify the hypotheses. Future studies could adopt longitudinal study design to prudently discuss the relationship between the stigma of loneliness, distress disclosure, loneliness, and psychological distress or resort to cross-lag models to explore the interaction between variables. In addition, future research can also adopt the ecological instantaneous assessment method to capture the subtle changes between variables from a dynamic perspective, to improve the ecological validity of the research conclusions. Second, all data from the study were self-reported by older adults, and it was difficult to rule out the effects of subjective evaluation bias or social approval effects.

Third, this study only examines the impact of loneliness stigma on psychological distress and its mechanism and does not delve into the interaction between variables. Previous studies have found that individuals with high levels of psychological distress have higher self-isolation and concealment tendencies, and loneliness and the degree of stigma attached to loneliness are more severe.92 Therefore, in future research, a cross-lag design can be considered to deeply analyze the interaction between loneliness stigma, distress disclosure, loneliness, and psychological distress. More studies could consider diverse measurements such as clinical interviews or third-party observations to improve the reliability of the study conclusion. Besides, the current study only included gender, age, marital status, and education as controllable variables, but other variables (eg socioeconomic status, physical health, and access to social support) may also have an effect. Fourth, introduce bias may exist due to the investigators of postgraduate and undergraduate students being trained. In the survey process, students may not completely comply with the standardized recruitment procedure or find it hard to be consistent with recruitment work in different regions.

Conclusions

This study explored the relationship between stigma of loneliness and psychological distress in older Chinese adults and analyzed its potential mechanism. The study found that the stigma of loneliness is associated with the psychological distress of the aged and the chain mediating effect of distress disclosure and loneliness in the relationship between the two. The current results can provide a theoretical reference for explaining the causes of psychological distress in older adults and provide empirical evidence for intervention research aimed at reducing psychological distress in the older cohort.

Funding Statement

This paper is the research result of the key project of education of National Social Science Foundation, “Research on Community Education System from the perspective of Lifelong Learning for All” (No. AKA210019).

Abbreviations

SLS, Stigma of Loneliness Scale; DDI, Distress Disclosure Index; ULS-6, UCLA Loneliness Scale; K6, 6-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale.

Ethics

Approved by the Jilin International Studies University (Approval No. JY202403006).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Foster L, Walker A. Active ageing across the life course: towards a comprehensive approach to prevention. Biomed Res Int. 2021. doi: 10.1155/2021/6650414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee C, Kuhn I, McGrath M, et al. A systematic scoping review of community-based interventions for the prevention of mental ill-health and the promotion of mental health in older adults in the UK. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(1):27–57. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mushtaq A, Khan MA. Social isolation, loneliness, and mental health among older adults during COVID-19: a scoping review. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2024;67(2):143–156. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2023.2237076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lei X, Matovic D, Leung T, Viju A, Wuthrich VM. The relationship between social media use and psychosocial outcomes in older adults: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriat. 2024;36(9):714–746. doi: 10.1017/S1041610223004519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai H, Jin Y, Liu R, et al. Global prevalence of depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological surveys. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;80:103417. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khodabakhsh S. Factors affecting life satisfaction of older adults in Asia: a systematic review. J Happiness Stud. 2022;23(3):1289–1304. doi: 10.1007/s10902-021-00433-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang T, Jiang J, Tang X. Prevalence of depression among older adults living in care homes in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;125:104114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Susanty S, Nadirawati N, Setiawan A, et al. Overview of the prevalence of loneliness and associated risk factors among older adults across six continents: a meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatrics. 2025;128(105627):105627. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2024.105627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surkalim DL, Luo M, Eres R, et al. The prevalence of loneliness across 113 countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022;376:e067068. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-067068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ong AD, Uchino BN, Wethington E. Loneliness and health in older adults: a mini-review and synthesis. Gerontology. 2016;62(4):443–449. doi: 10.1159/000441651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Link BG. On the history and growth of the stigma concept: a reflection on the positioning of social relationships in stigma research. J Social Issues. 2023;79(1):528–535. doi: 10.1111/josi.12582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan Z, Shi X, Zhang W, Zhang B. The effect of parental regulatory focus on the loneliness stigma of college children. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):273. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-17714-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neves BB, Petersen A. The social stigma of loneliness: a sociological approach to understanding the experiences of older people. Sociological Rev. 2024;00380261231212100. doi: 10.1177/00380261231212100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauge S, Kirkevold M. Older Norwegians’ understanding of loneliness. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2010;5(1):4654. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v5i1.4654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barreto M, Doyle DM, Qualter P. Changing the narrative: loneliness as a social justice issue. Political Psychology. 2024;45(S1):157–181. doi: 10.1111/pops.12965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenna-Plumley PE, Turner RN, Yang K, Groarke JM. Experiences of loneliness across the lifespan: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2023;18(1):2223868. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2023.2223868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manchester H, Barke J, Naughton-Doe R, Willis PB. Ethical issues when interviewing older people about loneliness:: reflections and recommendations for an effective methodological approach. Ageing Soc. 2022;44:1681–1699. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X2200099X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko SY, Wei M, Rivas J, Tucker JR. Reliability and validity of scores on a measure of stigma of loneliness. Counsel Psychol. 2022;50(1):96–122. doi: 10.1177/00110000211048000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Rüsch N. Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(2):75–81. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00218.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin S, Corrigan P, Margaglione M, Smith A. Self-Stigma’s effect on psychosocial functioning among people with mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2023;211(10):764–771. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiller M, Hammen CC, Shahar G. Links among the self, stress, and psychological distress during emerging adulthood: comparing three theoretical models. Self Identity. 2016;15(3):302–326. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2015.1131736 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Link BG, Phelan J. Stigma power. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wetherall K, Robb KA, O’Connor RC. Social rank theory of depression: a systematic review of self-perceptions of social rank and their relationship with depressive symptoms and suicide risk. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:300–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan Z, Shi X, Yang S, Sun Y, Chen R. Reliability and validity evaluation of the stigma of loneliness scale in Chinese college students. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):238. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-17738-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neves BB, Sanders A, Warren N, Ko PC. Loneliness in later life as existential inequality. Sociology. 2024;58(3):659–681. doi: 10.1177/00380385231208649 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen-Mansfield J, Eisner R. The meanings of loneliness for older persons. Aging Mental Health. 2020;24(4):564–574. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1571019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahn JH, Hessling RM. Measuring the tendency to conceal versus disclose psychological distress. J Socl Clin Psychol. 2001;20(1):41–65. doi: 10.1521/jscp.20.1.41.22254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taniguchi-Dorios E, Thompson CM, Reid T. Testing a model of disclosure, perceived support quality, and well-being in the college student mental illness context: a weekly diary study. Health Commun. 2023;38(11):2516–2526. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2022.2086841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ugwu LE, Idemudia ES, Akokuwebe ME, Onyedibe MCC. Beyond the shadows of trauma: exploring the synergy of emotional intelligence and distress disclosure in Nigerian adolescents’ trauma journey. South Afr J Psychol. 2024;54(1):35–50. doi: 10.1177/00812463241227515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan Z, Shi X, Hu C, Zhu L, Wang Z. Reliability and validity of self-concealment scale in Chinese older adults. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:4341–4352. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S434491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonsalves P, Nair R, Roy M, Pal S, Michelson D. A systematic review and lived experience synthesis of self-disclosure as an active ingredient in interventions for adolescents and young adults with anxiety and depression. Administration Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. 2023;50(3):488–505. doi: 10.1007/s10488-023-01253-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lh A, Kivlighan Jr DM. Working alliance, therapist expressive skills, and client outcome in psychodynamic therapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2022;69(1):74–84. doi: 10.1037/cou0000489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamagawa R, Moss-Morris R, Martin A, Robinson E, Booth RJ. Dispositional emotion coping styles and physiological responses to expressive writing. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18(3):574–592. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carmack CL, Basen-Engquist K, Yuan Y, et al. Feasibility of an expressive-disclosure group intervention for post-treatment colorectal cancer patients: results of the Healthy Expressions study. Cancer. 2011;117(21):4993–5002. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyons BJ, Zatzick CD, Thompson T, Bushe GR. Stigma identity concealment in hybrid organizational cultures. J Social Issues. 2017;73(2):255–272. doi: 10.1111/josi.12215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tay S, Alcock K, Scior K. Mental health problems among clinical psychologists: stigma and its impact on disclosure and help-seeking. J Clin Psychol. 2018;74(9):1545–1555. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dodson TS, Beck JG. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and attitudes about social support: does shame matter? J Anxiety Disord. 2017;47:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kharicha K, Manthorpe J, Iliffe S, et al. Managing loneliness: a qualitative study of older people’s views. Aging Mental Health. 2021;25(7):1206–1213. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1729337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barreto M, van Breen J, Victor C, et al. Exploring the nature and variation of the stigma associated with loneliness. J Soc Pers Relat. 2022;39(9):2658–2679. doi: 10.1177/02654075221087190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qin S, Sheehan L, Yau E, et al. Self-Stigma, secrecy, and disclosure among Chinese with serious mental illness. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2023. doi: 10.1007/s11469-023-01176-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lam JA, Murray ER, Yu KE, et al. Neurobiology of loneliness: a systematic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46(11):1873–1887. doi: 10.1038/s41386-021-01058-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pikhartova J, Bowling A, Victor C. Is loneliness in later life a self-fulfilling prophecy? Aging Mental Health. 2016;20(5):543–549. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1023767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lim MH, Gleeson JFM, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Penn DL. Loneliness in psychosis: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(3):221–238. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1482-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erzen E, Çikrikci Ö. The effect of loneliness on depression: a meta-analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64(5):427–435. doi: 10.1177/0020764018776349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mann F, Wang J, Pearce E, et al. Loneliness and the onset of new mental health problems in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(11):2161–2178. doi: 10.1007/s00127-022-02261-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akeren Z, Akeren I. The effect of loneliness on fear of aging: mediated by social support. Educat Gerontol. 2024;50:1–14. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2024.2374621 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanprakhon P, Suriyawong W, Chusri O, Rattanaselanon P. Exploring the association between loneliness, subjective cognitive decline, and quality of life among older Thai adults: a convergent parallel mixed-method study. J Appl Gerontol. 2024;2024:7334648241253989. doi: 10.1177/07334648241253989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang H, Hou Y, Zhang L, Yang M, Deng R, Yao J. Chinese elderly migrants’ loneliness, anxiety and depressive symptoms: the mediation effect of perceived stress and resilience. Front Public Health. 2022;10:998532. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.998532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lucjan P, Bird T, Murray C, Lorimer A. Loneliness and psychotic-like experiences in middle-aged and older adults: the mediating role of selective attention to threat and external attribution biases. Aging Mental Health. 2024;28:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2024.2372072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song W, Zhou Y, Chong ZY, Xu W. Social support, attitudes toward own aging, loneliness and psychological distress among older Chinese adults: a longitudinal mediation model. Psychol Health Med. 2024;29(3):542–555. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2023.2260965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park J, Jang Y, Oh H, Chi I. Loneliness as a mediator in the association between social isolation and psychological distress: a cross-sectional study with older Korean immigrants in the United States. Res Aging. 2023;45(5–6):438–447. doi: 10.1177/01640275221098180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lara E, Matovic S, Vasiliadis HM, et al. Correlates and trajectories of loneliness among community-dwelling older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: a Canadian longitudinal study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023;115:105133. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2023.105133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yan L, Ding X, Gan Y, Wang N, Wu J, Duan H. The impact of loneliness on depression during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: a two-wave follow-up study. Curr Psychol. 2024;43(43):33555–33564. doi: 10.1007/s12144-024-05898-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park C, Majeed A, Gill H, et al. The Effect of loneliness on distinct health outcomes: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;294:113514. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corrigan PW, Nieweglowski K, Sayer J. Self-stigma and the mediating impact of the “why try” effect on depression. J Community Psychol. 2019;47(3):698–705. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gordon CL, Luo S. The Personal Expansion Questionnaire: measuring one’s tendency to expand through novelty and augmentation. Pers Individ Dif. 2011;51(2):89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Willems YE, Finkenauer C, Kerkhof P. The role of disclosure in relationships. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;31:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang JH, Wang CC. Self-disclosure among bloggers: re-examination of social penetration theory. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;15(5):245–250. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2011.0403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang J, Xiang X, Yang X, Mei Q, Cheng L. The effect of self-disclosure on loneliness among patients with coronary heart disease: the chain mediating effect of social support and sense of coherence. Heart Lung. 2024;64:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2023.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Korem A. Opening the door of self-disclosure: supporting adolescents’ journey from loneliness to friendship. Eur Psychol. 2023;28(2):122–132. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pang T, Wang H, Zhang X, Zhang X. Self-Concept clarity and loneliness among college students: the chain-mediating effect of fear of negative evaluation and self-disclosure. Behav Sci. 2024;14(3):194. doi: 10.3390/bs14030194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen L, Cheng R, Hu B. The Effect of self-disclosure on loneliness in adolescents during covid-19: the mediating role of peer relationships. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:710515. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.710515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bruno S, Lutwak N, Agin MA. Conceptualizations of guilt and the corresponding relationships to emotional ambivalence, self-disclosure, loneliness and alienation. Pers Individ Dif. 2009;47(5):487–491. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.04.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keum BT, Oliffe JL, Rice SM, et al. Distress disclosure and psychological Distress among men: the role of feeling understood and loneliness. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(13):10533–10542. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02163-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quynh Ho TT, Nguyen HT. Self-disclosure on social networking sites, loneliness and psychological distress among adolescents: the mediating effect of cyber victimization. Eur J Develop Psychol. 2023;20(1):172–188. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2022.2068523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fan Z, Shi X, Liu X, Zhang Y, Xu J. Reliability and validity test of the stigma of loneliness scale in Chinese middle-aged population. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2024;32(3):606–611+554. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2024.03.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang J, Li Y, Gao R, Chen H, Yang Z. Relationship between mental health literacy and professional psychological help-seeking attitudes in China: a chain mediation model. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):956. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-05458-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hu C, Weng Y, Wang Q, et al. Fear of progression among colorectal cancer patients: a latent profile analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2024;32(7):469. doi: 10.1007/s00520-024-08660-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alsubheen SA, Oliveira A, Habash R, Goldstein R, Brooks D. Systematic review of psychometric properties and cross-cultural adaptation of the University of California and Los Angeles loneliness scale in adults. Curr Psychol. 2021;1–15. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02494-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Niu L, Jia C, Ma Z, Wang G, Yu Z, Zhou L. The validity of proxy-based data on loneliness in suicide research: a case-control psychological autopsy study in rural China. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1687-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lantos D, Moreno-Agostino D, Harris LT, Ploubidis G, Haselden L, Fitzsimons E. The performance of long vs. short questionnaire-based measures of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress among UK adults: a comparison of the patient health questionnaires, generalized anxiety disorder scales, malaise inventory, and Kessler scales. J Affect Disord. 2023;338:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shon EJ. Measurement equivalence of the Kessler 6 Psychological Distress Scale for Chinese and Korean immigrants: comparison between younger and older adults. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2020;29(2):e1823. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kerr NA, Stanley TB. Revisiting the social stigma of loneliness. Pers Individ Dif. 2021;171:110482. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Corrigan PW, Rao D. On the self-stigma of mental illness: stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(8):464–469. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li H. Towards an emic understanding of Mianzi giving in the Chinese context. J Politeness Res. 2020;16(2):281–303. doi: 10.1515/pr-2017-0052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leung AKY, Cohen D. Within- and between-culture variation: individual differences and the cultural logics of honor, face, and dignity cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;100(3):507–526. doi: 10.1037/a0022151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.She Z, Xu H, Cormier G, Drapeau M, Duncan BL. Culture matters: Chinese mental health professionals’ fear of losing face in routine outcome monitoring. Psychother Res. 2024;34(3):311–322. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2023.2240949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mann F, Bone JK, Lloyd-Evans B, et al. A life less lonely: the state of the art in interventions to reduce loneliness in people with mental health problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(6):627–638. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1392-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Corrigan PW, Bink AB, Schmidt A, Jones N, Rüsch N. What is the impact of self-stigma? Loss of self-respect and the “why try” effect. J Ment Health. 2016;25(1):10–15. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1021902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Casali N, Feraco T, Ghisi M, Meneghetti C. “Andrà tutto bene”: associations Between Character Strengths, Psychological Distress and Self-efficacy During Covid-19 Lockdown. J Happiness Stud. 2021;22(5):2255–2274. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00321-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Orth U, Robins RW, Meier LL, Conger RD. Refining the vulnerability model of low self-esteem and depression: disentangling the effects of genuine self-esteem and narcissism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2016;110(1):133–149. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cognit Sci. 2009;13(10):447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kahn JH, Hucke BE, Bradley AM, Glinski AJ, Malak BL. The Distress Disclosure Index: a research review and multitrait-multimethod examination. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(1):134–149. doi: 10.1037/a0025716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pathmalingam T, Moola FJ, Woodgate RL. Illness conversations: self-disclosure among children and youth with chronic illnesses. Chronic Illn. 2023;19(3):475–494. doi: 10.1177/17423953221110152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Korsbek L. Disclosure: what is the point and for whom? J Ment Health. 2013;22(3):283–290. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2013.799264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim HS, Sherman DK, Taylor SE. Culture and social support. Am Psychol. 2008;63(6):518–526. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kahn JH, Wei M, Su JC, Han S, Strojewska A. Distress disclosure and psychological functioning among Taiwanese nationals and European Americans: the moderating roles of mindfulness and nationality. J Couns Psychol. 2017;64(3):292–301. doi: 10.1037/cou0000202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marzo RR, Khanal P, Ahmad A, et al. Quality of life of the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic in asian countries: a cross-sectional study across six countries. Life. 2022;12(3):365. doi: 10.3390/life12030365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Marzo RR, Khanal P, Shrestha S, Mohan D, Myint PK, Su TT. Determinants of active aging and quality of life among older adults: systematic review. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1193789. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1193789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen HWJ, Marzo RR, Sapa NH, et al. Trends in health communication: social media needs and quality of life among older adults in Malaysia. Healthcare. 2023;11(10):1455. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11101455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Adlington K, Vasquez C, Pearce E, et al. “Just snap out of it” - The experience of loneliness in women with perinatal depression: a Meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-04532-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]