Abstract

Study Objectives

Sleep spindles, defining electroencephalographic oscillations of nonrapid eye movement (NREM) stage 2 sleep (N2), mediate sleep-dependent memory consolidation (SDMC). Spindles are also thought to protect sleep continuity by suppressing thalamocortical sensory relay. Schizophrenia is characterized by spindle deficits and a correlated reduction of SDMC. We investigated whether this relationship is mediated by sleep fragmentation.

Methods

We detected spindles (12–15 Hz) during N2 at central electrodes in overnight polysomnography records from 56 participants with chronic schizophrenia and 59 healthy controls. Our primary measures of sleep continuity were the sleep fragmentation index and, in a subset of the data, visually scored arousals. SDMC was measured as overnight improvement on the finger-tapping motor sequence task.

Results

Participants with schizophrenia showed reductions of both spindle density (#/min) and SDMC in the context of normal sleep continuity and architecture. Spindle density predicted SDMC in both groups. In contrast, neither increased sleep fragmentation nor arousals predicted lower spindle density or worse SDMC in either group.

Conclusions

Our findings fail to support the hypothesis that sleep fragmentation accounts for spindle deficits, impaired SDMC, or their relationship in individuals with chronic schizophrenia. Instead, our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that spindle deficits directly impair memory consolidation in schizophrenia. Since sleep continuity and architecture are intact in this population, research aimed at developing interventions should instead focus on understanding dysfunction within the thalamocortical-hippocampal circuitry that both generates spindles and synchronizes them with other NREM oscillations to mediate SDMC.

Keywords: schizophrenia, sleep spindles, sleep continuity, memory consolidation, sleep fragmentation index, arousals, thalamic reticular nucleus, motor sequence task

Statement of Significance.

In addition to their well-established role in sleep-dependent memory consolidation (SDMC), sleep spindles may also contribute to sleep continuity. In schizophrenia, reduced spindle density correlates with impaired SDMC. Here, we investigated whether sleep fragmentation might underlie this relationship. Our findings failed to support this possibility. Instead, they are consistent with the hypothesis that reduced spindle density in individuals with chronic schizophrenia directly impairs SDMC. Since both sleep continuity and architecture are generally intact in this population, future research aimed at developing interventions to improve memory might instead focus on understanding dysfunction within the thalamocortical-hippocampal circuitry that both generates spindles and synchronizes them with other NREM sleep oscillations to mediate SDMC.

Sleep spindles, defining electroencephalographic (EEG) oscillations of nonrapid eye movement (NREM) stage 2 sleep (N2), are brief bursts of synchronous activity in the 10–15 Hz range in a waxing, waning envelope [1]. In addition to their well-established role in memory consolidation, spindles are thought to maintain sleep continuity by suppressing sensory relay from the thalamus to the cortex during sleep [2]. Schizophrenia is characterized by spindle deficits that correlate with impaired sleep-dependent memory consolidation (SDMC; for review see [3]). Here, we investigate whether sleep fragmentation may underlie this relationship.

The physiology of sleep spindles is relatively well understood based on decades of animal and human studies [4–6]. Spindles are generated in the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN) and are propagated to the cortex via thalamocortical circuitry [7, 8]. They are a key facilitator of the synaptic plasticity involved in memory [9]. Spindles correlate with SDMC, learning efficiency, and IQ [10]. In schizophrenia, reduced spindle activity [11–13] is associated with impaired sleep-dependent consolidation of both procedural and declarative memory, lower IQ, and worse executive function [14–16]. Animal and human studies provide evidence that spindles also play a role in maintaining sleep continuity. Sensory-projecting TRN neurons that are involved in spindle generation suppress cortical sensory processing during both sleep and wake [17]. In mice, optogenetically induced spindles increase the duration of NREM sleep [18]. In humans, the cortical response to noise is suppressed during spindles [19–22] and higher spindle density correlates with higher noise tolerance during sleep [23]. Difficulties in maintaining sleep, including increased awakenings and wake-time after sleep onset (WASO), are often reported in individuals with schizophrenia (c.f. meta-analysis [24]). In addition, rodent models relevant to schizophrenia show reduced spindles in the context of sleep fragmentation [25, 26]. The hypothesized dual function of spindles in maintaining sleep continuity and consolidating memory raises the question of whether impaired SDMC in schizophrenia is more likely to be a direct effect of reduced spindles or due to sleep fragmentation (i.e. does the spindle deficit in schizophrenia lead to greater sleep fragmentation, which, in turn impairs memory?). If the spindle-SDMC relationship was mediated by sleep fragmentation, we would expect greater fragmentation to correlate with lower spindle density, which, in turn, would correlate with more impaired SDMC. Alternatively, if impaired SDMC in schizophrenia was a direct effect of the spindle deficit, and not any sleep fragmentation that results from it, we would expect reduced spindle density, but not increased sleep fragmentation, to predict worse SDMC.

To evaluate these possibilities, we characterized archival overnight polysomnography (PSG) data from participants with chronic schizophrenia and demographically matched healthy controls using the sleep fragmentation index (SFI) [27, 28]. While the SFI can be easily derived from sleep staging, it only captures arousals that are longer than 15 s and result in a transition to N1 or wake [1]. To ensure that our findings with SFI replicated using a more sensitive measure of sleep fragmentation (i.e. one that includes shorter arousals and those that do not result in a transition), we visually identified arousals in a subset of our data. To measure SDMC, we used the finger-tapping motor sequence task (MST), which is the most extensively validated probe of SDMC. We have reported on its sleep dependence in healthy adults [29] and on the failure of sleep-dependent improvement in schizophrenia [15, 30]. All participants were trained on the MST before sleep and were tested the following morning. We hypothesized that in schizophrenia, (i) reduced spindle density would predict worse SDMC, as in prior findings from these samples and others [15, 31–33], and (ii) that sleep fragmentation would not correlate with either spindle density or SDMC based on previous findings of spindle and SDMC deficits in the context of normal sleep quality and architecture in schizophrenia [11, 12, 15, 31, 34]. This would indicate that sleep fragmentation was unlikely to mediate the relationship of spindle density with SDMC.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The final sample was comprised of 56 participants with chronic schizophrenia and 59 healthy controls from three published studies: Dataset (1) 28 controls, 26 schizophrenia [31]; Dataset (2) 17 controls, 19 schizophrenia [15, 35]; Dataset (3) 14 controls, 11 schizophrenia [13]. For two control and eight schizophrenia participants who were in more than one study, only data from the most recent study were included. MST data from one control and one schizophrenia participant were missing, and data from two schizophrenia participants were excluded due to experimenter error during data collection. Diagnoses of schizophrenia were confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV [36]. Three schizophrenia participants were unmedicated and the rest were maintained on stable doses of antipsychotic drugs (APDs) and adjunctive medications for at least 6 weeks before participation (Supplementary Table S1). Healthy controls were screened to exclude a personal history of mental illness [37] and a family history of schizophrenia spectrum disorder or psychosis. All participants were screened to exclude diagnosed sleep disorders, except insomnia. Schizophrenia and control groups were matched for age and sex, but controls had significantly higher mean parental education (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants characteristics

| Control (n = 59) M±SD, range |

Schizophrenia (n = 56) M±SD, range |

F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 35 ± 8 [22–55] | 36 ± 9 [18–60] | .51 | .48 |

| Sex | 44M/15F | 43M/13F | χ 2 = .08 | .78 |

| Parental education (years) | 15 ± 3 [10, 22] | 14 ± 3 [6, 21] | 4.81 | .03 * |

| Rating scales scores/level of severity (schizophrenia only) | ||||

| PANSS total | 62 ± 18 (Mild) | |||

| PANSS positive | 14 ± 6 (Mild) | |||

| PANSS negative | 17 ± 6 (Mild) | |||

| PANSS general | 31 ± 9 (Mild) | |||

| SANS | 34 ± 19 (Minimal) | |||

| Medication dosages | ||||

| Chlorpromazine equivalents (mg)* | 474 ± 384 | |||

M±SD: Mean ± Standard Deviation; PANSS: Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; SANS: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms.

aChlorpromazine equivalent dosage was calculated only for medicated patients.

Procedures

SDMC of the MST.

The MST requires participants to repeatedly type a 5-digit sequence (e.g. 4-1-3-2-4) on a numerically labeled keyboard with their left hand, “as quickly and accurately as possible” for twelve 30 s typing trials separated by 30 s rest periods. The sequence is displayed at the top of the screen, and dots appear beneath it with each keystroke. Participants train on 12 trials before sleep and are tested on an additional 12 trials after sleep. Performance is measured as the number of correctly typed sequences per trial, which reflects both the speed and accuracy of performance [29, 38–40].

Before analysis, outlier trials were detected and removed. To identify outliers, MST performance in each session was modeled using a piecewise power function [30]. The training and test data for each condition were fit to the equation, , where Y = correct sequences typed on trial t; I = initial performance (on trial 1); C = change in performance from trial 1 to the asymptote (amount learned); 1-R = the learning rate; t = trial number; D = overnight improvement; d = 0 (for training) or d = 1 (for testing); and e is a stochastic error term. Trials more than 2 SD below the mean of the squared residuals of individual MST performance on each trial were excluded (118 out of 2712 trials; 5% controls, 4% patients). Since there is no basis for excluding trials on which participants performed better than expected, we kept trials that were 2 SD above the mean.

Learning during training was calculated as both the percent and absolute change in correctly typed sequences from the first trial to the average of the three trials with the best performance. Overnight improvement was calculated as the percent change in correctly typed sequences from the average of the best three training trials at night to the first three test trials the following morning. We measured MST performance before sleep using the best three training trials instead of the last three, which has been typically used [29] since the average of the best three trials better reflects optimal presleep performance. For the measurement of overnight improvement, if any of the first three test trials were excluded, the remaining trials were averaged.

Polysomnography

Details of PSG data collection can be found in the primary publications [13, 15, 31]. All overnight sleep recordings took place in the General Clinical Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital. PSG data were downsampled to 100 Hz. Data from datasets 1 and 2 were rereferenced to linked mastoids. Data from dataset 3 were referenced to the contralateral mastoid. EEG data were band-pass filtered at 0.3–35 Hz and the artifact rejected using Luna v0.26 (http://zzz.bwh.harvard.edu/luna/), BrainVision Analyzer 2.0 (BrainProducts, Germany), and custom scripts in Matlab (MathWorks, Natick MA).

Sleep architecture and fragmentation

Each 30-s epoch was scored according to standard criteria as WAKE, Rapid Eye Movement Sleep (REM), N1, N2, or N3 by expert raters blind to diagnosis [1]. Time in each sleep stage was calculated both as total minutes and percent of total sleep time (TST). WASO was measured in minutes. We could not retrieve lights-on and -off markers, but sleep efficiency did not differ between groups in the original reports [13, 15, 31]. We measured sleep fragmentation with the SFI, which captures transitions to wake and to N1 sleep [28]. In a subset of the data (dataset 1), we also scored arousals according to standard AASM criteria [41]. Scoring was conducted by experts (OL, LZ, RP) with established inter-rater reliability who were blind to diagnosis. An arousal is defined as an abrupt shift of EEG frequency to alpha, theta, and/or frequencies greater than 16 Hz (but not sigma) lasting at least 3 s, preceded by at least 10 seconds of stable sleep. Outcome measures of sleep fragmentation were SFI (# transitions/h of TST), arousal density (# arousals/h of TST), and mean arousal length (sec). SFI and arousals were calculated for all sleep and for N2 sleep alone.

Sleep spindles

Spindle analyses were restricted to central electrodes (C3, Cz, and C4), which were common to all datasets. Spindles were automatically detected during N2 in the 12–15 Hz band-pass-filtered data at each electrode using a validated wavelet-based algorithm [15, 42]. The threshold for spindle detection, nine times the median signal amplitude of artifact-free epochs, maximized between-class variance (spindle vs. nonspindle) [43]. The outcome measure was N2 spindle density (spindles per minute) averaged across electrodes.

We focused on N2 spindle activity since it reliably differentiates schizophrenia from control participants and correlates with SDMC of the MST in ours [15, 31] and other studies [29, 44], in the context of largely intact spindle morphology and coupling [45, 46].

Statistical analysis

Linear regression models were used to investigate group differences in sleep fragmentation, sleep architecture, spindle density, and SDMC. Group and Age were included as factors. Cohort (datasets 1, 2, 3) was included in all analyses as a nuisance factor, since the samples were collected from 2007 to 2019. An interaction term of Group by Age was included to investigate whether relationships with Age differed by Group. To examine the relation of arousal density with SFI, we used a linear regression model with Group and Age as factors. To evaluate potential effects of treatment with APDs in patients, we investigated the relations of APD dose, measured as chlorpromazine equivalents [47], with sleep fragmentation measures, spindle density, and MST improvement, including Age as a covariate [44].

To evaluate whether the relation of reduced spindle density with impaired SDMC in schizophrenia can be explained by sleep fragmentation, we measured the correlations of 1) spindle density with overnight improvement on the MST, 2) spindle density with SFI and arousal density, and 3) SFI and arousal density with overnight improvement. We used linear regression models with Group, Age, and Cohort as factors. Interaction terms of SFI, arousal density, and spindle density with Group were included in the models to determine whether the relations differed by Group. To examine whether SFI might affect the relation of spindle density with SDMC we also tested the interaction of spindle density with SFI. To adjust for comparisons across multiple regression models, we used False Discovery Rate, with a false positive rate of .05, applied to the omnibus p-values [48, 49]. Only models with adjusted p ≤ .05 are reported as significant.

Results

Group differences in sleep architecture and continuity

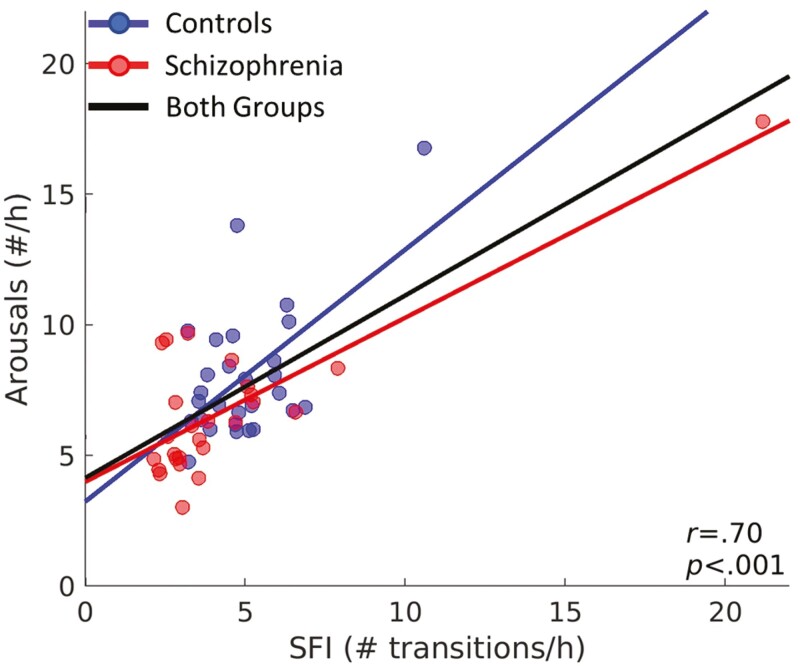

TST, WASO, and sleep architecture did not differ by Group (Table 2). The schizophrenia group had numerically lower SFI (p = .18) and arousal density (p = .06) than controls. Arousal density was highly correlated with SFI (F(1,49) = 47.22, p < .001; Figure 1) and this relationship did not differ by Group (F(1,49) = 1.88, p = .18). Group differences in SFI divided by sleep stage and transitions to N1 versus Wake are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Schizophrenia participants had less fragmented REM, fewer total transitions to N1, and fewer transitions from N2 to N1 than controls.

Table 2.

Effects of group and age on sleep continuity, sleep architecture, spindle density, and SDMC

| Control | Schizophrenia | Group | Age | Group × Age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Sleep continuity | ||||||||

| TST (min) | 451 ± 74 | 464 ± 106 | 1.13 | .29 | 8.46 | .004 * | .001 | .97 |

| WASO (min) | 45 ± 29 | 48 ± 56 | .03 | .87 | 8.07 | .005 * | 3.07 | .08 |

| SFI (# transitions/h of TST) | 5.3 ± 1.9 | 4.8 ± 3.7 | 1.86 | .18 | 3.41 | .07 | 3.63 | .06 |

| bArousal density (#/h of TST) | 8.0 ± 2.6 | 6.7 ± 2.9 | 3.80 | .06 | 1.21 | .28 | 2.26 | .14 |

| bArousal length (sec) | 9.9 ± 1.7 | 10.2 ± 1.7 | .30 | .58 | .02 | .90 | .09 | .77 |

| Sleep architecture (min) | ||||||||

| N1 | 40 ± 21 | 36 ± 21 | 1.12 | .29 | .32 | .58 | .01 | .92 |

| N2 | 249 ± 53 | 261 ± 81 | 1.43 | .23 | 3.38 | .07 | 0 | .99 |

| N3 | 71 ± 35 | 80 ± 54 | 1.22 | .27 | 1.24 | .27 | .43 | .51 |

| REM | 91 ± 30 | 88 ± 39 | .23 | .63 | 6.07 | .02 | .39 | .53 |

| Sleep architecture (%) | ||||||||

| N1 | 9 ± 4 | 8 ± 5 | .37 | .55 | 4.01 | .05 | .07 | .78 |

| N2 | 55 ± 9 | 56 ± 12 | .53 | .47 | 0 | .99 | .08 | .78 |

| N3 | 16 ± 7 | 17 ± 10 | .72 | .40 | .02 | .88 | .39 | .53 |

| REM | 20 ± 7 | 18 ± 7 | 2.51 | .12 | 1.48 | .22 | .67 | .41 |

| Sleep spindles | ||||||||

| Spindle density (#/min) | 4.4 ± 2.1 | 2.7 ± 1.6 | 78.08 | <.001 * | 11.13 | .001 * | .11 | .74 |

| Memory consolidation | ||||||||

| MST improvement (%) | 8.1 ± 13.1 | −.9 ± 18.3 | 10.90 | .001 * | 6.68 | .01 * | .59 | .44 |

aArousals were visually scored only in dataset 3.

*Only models with p ≤ .05 after multiple comparison correction are denoted as significant.

Figure 1.

Relationship between SFI and arousal density. Arousal density plotted against SFI. Circles represent data for each individual. Regression lines are plotted for each group separately and for the combined groups. The relation of arousal density with SFI remained significant even after excluding the outlying datapoint [21, 18] with high leverage (r = .57, p < .001).

Group differences in learning, SDMC, and sleep spindles

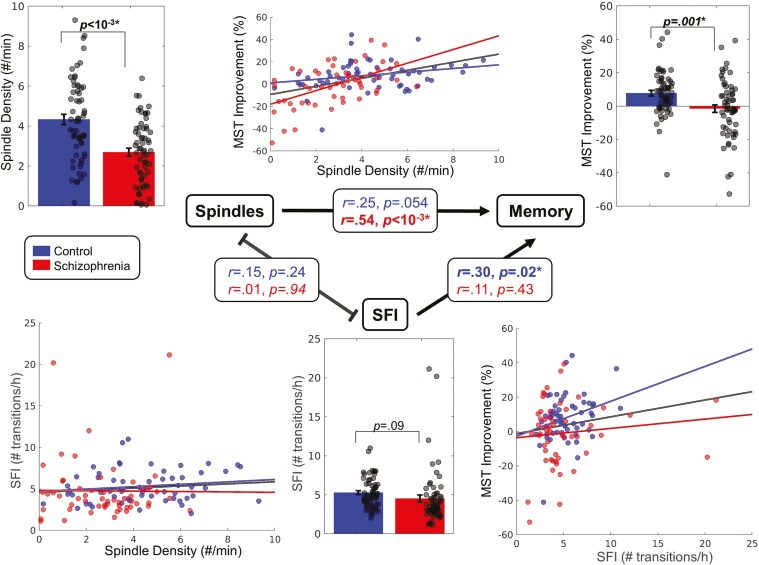

Schizophrenia participants had a higher learning rate during training (Control: 64 ± 43%, Schizophrenia: 96 ± 54%; F(1,103) = 12.89, p < .001) but did not differ in the number of sequences gained (Control: 7.4 ± 3.3, Schizophrenia: 6.5 ± 3.7; F(1,103) = 0.97, p = .33). Consistent with previous studies (for meta-analysis see [50]) controls showed significant overnight improvement on the MST (8.1%; t(57) = 4.71, p < .001), while patients showed no improvement (−0.9%, t(52) = −0.35, p = .73), and differed from controls in this regard (F(1,105) = 10.97; p = .001). Also consistent with previous studies (for meta-analysis see [34]), spindle density was lower in patients than controls (39% reduction, p < .001; Figure 2, Table 2).

Figure 2.

Relations between sleep spindle density, SFI, and SDMC of the MST. Bar graphs depicting group differences in spindle density (top left), SFI (bottom middle), and MST improvement (top right) for each group (mean ± SE). Scatter plots show the relations of spindle density with SFI (bottom left), spindle density with MST improvement (top middle), and SFI with MST improvement (bottom right). Regression lines are shown for each group and for the groups together. The central triangle depicts relations between variables. Arrows represent significant relationships.

Relations of sleep spindles, sleep fragmentation, and SDMC

Relations of spindle density and sleep fragmentation with SDMC.

In the full dataset, higher spindle density predicted greater overnight improvement on the MST (F(1,104) = 9.92, p = .002). This relationship differed by Group (F(1,104) = 7.15, p = .008), reflecting a stronger correlation in schizophrenia (r = .54, p < .001; Figure 2) than controls: (r = .25, p = .054) and remained significant even when SFI was included in the model as a covariate (F(1,104) = 9.01, p = .003). The interaction of spindle density with SFI did not predict overnight improvement (F(1,103) = 0.05, p = .83) indicating that SFI did not change the effect of spindle density on SDMC. The results were similar when the measures of SFI were restricted to N2: Spindle density predicted overnight improvement (F(1,104) = 8.25, p = .005), but the interaction of spindle density with N2 SFI did not (F(1,103) =0.82, p = .37). This was also true in the schizophrenia group alone: spindle density predicted overnight improvement (F(1,46)=9.78, p = .003), but the interaction of spindle density with SFI did not (F(1,46)=0.11, p = .74).

Relations of spindle density with sleep fragmentation.

Spindle density did not correlate with WASO (F(1,108) = 0.02, p = .90) or with SFI across all sleep (F(1,108) = 0.61, p = .44) or during N2 alone (F(1,108) = 2.03, p = .16; Figure 2). In the subset of the sample with scored arousals, spindle density did not correlate with arousal density (F(1,49) = 0.56, p = .46) or length (F(1,49) = 0.003, p = .96) and the results were similar when arousal measures were restricted to N2 (arousal density: F(1,49) = 3.26, p = .08, arousal length F(1,49) = 0.22, p = .64).

Relations of SDMC with sleep fragmentation.

Surprisingly, higher SFI predicted greater MST overnight improvement (F(1,104) = 5.47, p = .02). This relationship was primarily driven by controls (Control: r = .30, p = .02; Schizophrenia: r = .11, p = .43; Figure 2), but the interaction with Group did not reach significance (F(1,104) = 0.50, p = .48). WASO did not correlate with overnight improvement (F(1,104) = 1.04, p = .31) nor did arousal density (F(1,48) = 0.42, p = .52) or length (F(1,48) = 0.23, p = .63). Neither N2 arousal length (F(1,49) = 3.07, p = .09) nor arousal density (F(1,49) = 1.89, p = .18) significantly predicted MST overnight improvement.

Control analyses

Effects of age on sleep and memory.

Consistent with the literature [51–53], aging was associated with a decline in sleep quality. Older individuals had less TST (Control: r = −.52, p < .001; Schizophrenia: r = −.34, p = .01) and more WASO (Control: r = .32, p = .02; Schizophrenia: r = .40, p = .002), and these relations did not differ by Group. Neither SFI nor arousal density and length correlated with age, and these relations did not differ by Group (Table 2). Both spindle density (Control: r = −.33, p = .01, Schizophrenia: r = −.41, p = .002) and MST overnight improvement (Control: r = −.41, p = .001, Patients: r = −.37, p = .006) decreased with age and these relationships did not differ by Group. The amount of time spent in REM decreased with Age (Control: r = −.27, p = .04; Schizophrenia: r = −.34, p = .01) similarly for both groups (Group by Age: F(1,109) = 0.39, p = .53), but this relation did not pass correction for multiple comparisons (Table 2).

Sex differences in sleep and memory.

There were no sex differences in spindle density (F(1,108) = 0.08, p = .78), MST improvement (F(1,104) = 0.26, p = .61), SFI (F(1,108) = 2.39, p = .12), arousal density (F(1,50) = 0.56, p = .46), or arousal length (F(1,50) = 0.53, p = .47).

Effects of antipsychotic dose on sleep and memory.

APD dose did not correlate with TST (F(1,51) = 0.04, p = .84), WASO (F(1,51) = 1.07, p = .30), SFI (F(1,51) = 0.32, p = .58), arousal density (F(1,23) = 0.01, p = .92), or arousal length (F(1,23) = 3.45, p = .08). Higher APD dose was significantly correlated with lower spindle density (F(1,51) = 6.54, p = .01), but not with MST overnight improvement (F(1,51) = 1.76, p = .19). Including APD dose as a covariate did not change the relationship of spindle density with either SDMC (F(1,50) = 8.46, p = .006) or SFI (F(1,50) = 0.57, p = .46) in schizophrenia. When we exclude the three unmedicated patients, the correlations of spindle density with SDMC (F(1,45) = 7.16, p = .01) and SFI (F(1,48) = 0.22, p = .64) in schizophrenia do not change.

Discussion

Our findings fail to support the hypothesis that the relationship of reduced sleep spindles with impaired SDMC is mediated by sleep fragmentation in individuals with chronic schizophrenia. As previously reported in the present samples, patients with schizophrenia showed reduced spindles and a correlated impairment of SDMC in the context of intact learning during training and normal sleep continuity, quality, and architecture [13, 15, 31, 35]. Here, we show that in schizophrenia, neither reduced spindle density nor impaired SDMC correlates with sleep fragmentation measured as either the SFI or arousals suggesting that sleep fragmentation does not mediate the relation of spindle deficits with impaired SDMC. Instead, our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the lower rate of spindles leads to worse SDMC in individuals with chronic schizophrenia.

Sleep disturbances are commonly seen in schizophrenia (for review see [54]). These include reduced TST and increased sleep onset latency and WASO, which are consistently found in APD-naïve and unmedicated schizophrenia patients, but not in patients taking APDs (see meta-analysis [24]). Both first- and second-generation APDs (with the possible exception of risperidone) increase TST and sleep efficiency [55, 56]. Thus, treatment with APDs may account for findings of intact sleep quality (except for longer sleep onset latency), architecture, and continuity in medicated patients with chronic schizophrenia in this and prior studies [3, 11, 12, 45]. Despite APD treatment, spindle deficits and impaired SDMC remain [3, 45, 57], even in early course medicated schizophrenia patients [46].

Spindle deficits are a highly consistent finding in schizophrenia [45] (meta-analysis [34]), including in APD-naïve patients and unaffected first-degree relatives [16, 58, 59], suggesting that the spindle deficit is an endophenotype [60]. A large body of work in rodents and humans demonstrates that spindles act in concert with cortical slow oscillations and hippocampal sharp wave ripples to mediate SDMC during NREM sleep [61–64]. Spindles and their coupling with slow oscillations can be enhanced pharmacologically and with noninvasive brain stimulation in humans, including those with schizophrenia [31, 35, 65]. In some studies, this enhancement corresponds with improved SDMC [66–74]. This work advances spindle physiology as a promising target for therapy to improve cognitive deficits in schizophrenia (for review see [75]).

Several lines of evidence suggest that spindles may also contribute to maintaining sleep continuity by gating the relay of sensory information from the thalamus to the cortex in the context of noise [2, 18–23]. In the present study, however, lower spindle density did not correlate with increased SFI or arousals in either group. This may reflect that arousals did not result from external stimuli (i.e. spindles may play a protective role only in noisy environments). Alternatively, it may refute the spindle gating hypothesis. In the present study, spindles correlated with SDMC in both groups, consistent with their well-established mnemonic function.

Unsurprisingly, we replicated previous findings of age-related decreases in TST, along with the increases of WASO in healthy individuals [53, 76], and found similar relationships in schizophrenia. We also replicated prior work showing declines in spindle density with age [51] and extended these findings to schizophrenia. Overnight consolidation of the MST also declined with age in both controls and individuals with schizophrenia. Previous studies of the effects of aging on procedural memory consolidation in healthy adults report either declines or no change [77–80].

A limitation of this study is that we scored arousals in only a subset of the data. Scoring arousals visually is a time-consuming task that is associated with low interrater reliability [81]. Although they capture different aspects of sleep disruption, we and others find that SFI and arousals are highly correlated [27], suggesting that they both accurately reflect sleep continuity. Another potential limitation is that all but three schizophrenia participants were medicated and we cannot rule out the possibility of medication effects on our measures. We note that even in samples not treated with APDs (i.e. healthy controls, APD-naïve patients with schizophrenia, and their first-degree relatives), sleep quality does not correlate with spindle density [16], suggesting that it does not account for the relations of spindle density with SDMC in these groups.

In summary, our findings support the hypothesis that in individuals with chronic schizophrenia, spindle deficits impair SDMC independently of any effects of sleep fragmentation. Since sleep continuity and architecture are intact in this group, future research aimed at developing interventions to improve memory should focus on understanding dysfunction in the thalamocortical-hippocampal circuitry that generates spindles and coordinates them with other NREM sleep oscillations to mediate SDMC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

In honor of Bob Stickgold, our beloved friend and collaborator, and demigod of sleep research. In memory of Robert McCarley who challenged us with the question that motivated this manuscript many years ago.

Contributor Information

Dimitrios Mylonas, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Psychiatry, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, MA, USA.

Rudra Patel, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Olivia Larson, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Lin Zhu, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Mark Vangel, Department of Biostatistics, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Radiology, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, MA, USA .

Bryan Baxter, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Psychiatry, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, MA, USA.

Dara S Manoach, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Psychiatry, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, MA, USA.

Author contributions

Dimitrios Mylonas (Conceptualization [equal], Data curation [equal], Formal Analysis [lead], Investigation [equal], Methodology [lead], Visualization [lead], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Rudra Patel (Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal], Writing—original draft [equal]), Olivia Larson (Data curation [equal], Formal Analysis [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal]), Lin Zhu (Formal Analysis [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal]), Mark Vangel (Formal Analysis [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal]), Bryan Baxter (Formal Analysis [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal]), and Dara Manoach (Conceptualization [lead], Data curation [equal], Formal Analysis [equal], Funding acquisition [lead], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [equal], Resources [lead], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal])

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01-MH 092638 to D.S.M. and utilized resources provided by the National Center for Research Resources UL1TR001102-01 to Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan SF.. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specification. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(7):121–131.17557422 [Google Scholar]

- 2. McCormick DA, Bal T.. Sensory gating mechanisms of the thalamus. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4(4):550–556. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90056-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manoach DS, Stickgold R.. Abnormal sleep spindles, memory consolidation, and schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2019;15:451–479. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steriade M, Domich L, Oakson G, Deschenes M.. The deafferented reticular thalamic nucleas generates spindle rhythmicity. J Neurophysiol. 1987;57(1):260–273. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1152/jn.1987.57.1.260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steriade M, Deschenes M, Domich L, Mulle C.. Abolition of spindle oscillations in thalamic neurons disconnected from nucleus reticularis thalami. J Neurophysiol. 1985;54(6):1473–1497. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1152/jn.1985.54.6.1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Steriade M, McCormick DA, Sejnowski TJ.. Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science (New York, N.Y.). 1993;262(5134):679–685. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.8235588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Contreras D, Steriade M.. Spindle oscillation in cats: the role of corticothalamic feedback in a thalamically generated rhythm. J Physiol. 1996;490 (Pt 1)(1):159–179. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Contreras D, Destexhe A, Sejnowski TJ, Steriade M.. Control of spatiotemporal coherence of a thalamic oscillation by corticothalamic feedback. Science (New York, N.Y.). 1996;274(5288):771–774. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.274.5288.771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sejnowski TJ, Destexhe A.. Why do we sleep? Brain Res. 2000;886(1-2):208–223. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03007-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fogel SM, Smith CT.. The function of the sleep spindle: a physiological index of intelligence and a mechanism for sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(5):1154–1165. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferrarelli F, Peterson MJ, Sarasso S, et al. Thalamic dysfunction in schizophrenia suggested by whole-night deficits in slow and fast spindles. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1339–1348. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ferrarelli F, Huber R, Peterson MJ, et al. Reduced sleep spindle activity in schizophrenia patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(3):483–492. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manoach DS, Thakkar KN, Stroynowski E, et al. Reduced overnight consolidation of procedural learning in chronic medicated schizophrenia is related to specific sleep stages. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(2):112–120. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Göder R, Graf A, Ballhausen F, et al. Impairment of sleep-related memory consolidation in schizophrenia: relevance of sleep spindles? Sleep Med. 2015;16(5):564–569. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wamsley EJ, Tucker MA, Shinn AK, et al. Reduced sleep spindles and spindle coherence in schizophrenia: mechanisms of impaired memory consolidation? Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(2):154–161. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Manoach DS, Demanuele C, Wamsley EJ, et al. Sleep spindle deficits in antipsychotic-naïve early course schizophrenia and in non-psychotic first-degree relatives. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8(OCT):762. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Halassa MM, Chen Z, Wimmer RD, et al. State-dependent architecture of thalamic reticular subnetworks. Cell. 2014;158(4):808–821. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim A, Latchoumane C, Lee S, et al. Optogenetically induced sleep spindle rhythms alter sleep architectures in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(50):20673–20678. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1217897109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schabus M, Dang-Vu TT, Heib DPJ, et al. The fate of incoming stimuli during NREM sleep is determined by spindles and the phase of the slow oscillation. Front Neurol. 2012;3(April):1–11. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fneur.2012.00040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dang-Vu TT, Bonjean M, Schabus M, et al. Interplay between spontaneous and induced brain activity during human non-rapid eye movement sleep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(37):15438–15443. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1112503108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cote KA, Epps TM, Campbell KB.. The role of the spindle in human information processing of high-intensity stimuli during sleep. J Sleep Res. 2000;9(1):19–26. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00188.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elton M, Winter O, Heslenfeld D, Loewy D, Campbell K, Kok A.. Event-related potentials to tones in the absence and presence of sleep spindles. J Sleep Res. 1997;6(2):78–83. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1997.00033.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dang-Vu TT, McKinney SM, Buxton OM, Solet JM, Ellenbogen JM.. Spontaneous brain rhythms predict sleep stability in the face of noise. Curr Biol. 2010;20(15):R626–R627. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chan MS, Chung KF, Yung KP, Yeung WF.. Sleep in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of polysomnographic findings in case-control studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;32:69–84. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Phillips KG, Bartsch U, McCarthy AP, et al. Decoupling of sleep-dependent cortical and hippocampal interactions in a neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia. Neuron. 2012;76(3):526–533. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aguilar DD, Strecker RE, Basheer R, McNally JM.. Alterations in sleep, sleep spindle, and EEG power in mGluR5 knockout mice. J Neurophysiol. 2020;123(1):22–33. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1152/jn.00532.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haba-Rubio J, Ibanez V, Sforza E.. An alternative measure of sleep fragmentation in clinical practice: the sleep fragmentation index. Sleep Med. 2004;5(6):577–581. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morrell MJ, Finn L, Hyon K, Peppard PE, Badr MS, Young T.. Sleep fragmentation, awake blood pressure, and sleep-disordered breathing in a population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(6):2091–2096. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.9904008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walker MP, Brakefield T, Morgan A, Hobson JA, Stickgold R.. Practice with sleep makes perfect: sleep-dependent motor skill learning. Neuron. 2002;35(1):205–211. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00746-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Manoach DS, Cain MS, Vangel MG, Khurana A, Goff DC, Stickgold R.. A failure of sleep-dependent procedural learning in chronic, medicated schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(12):951–956. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mylonas D, Baran B, Demanuele C, et al. The effects of eszopiclone on sleep spindles and memory consolidation in schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45(13):2189–2197. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41386-020-00833-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Albouy G, Fogel S, Pottiez H, et al. Daytime sleep enhances consolidation of the spatial but not motoric representation of motor sequence memory. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e52805. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0052805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Seeck-Hirschner M, Baier PC, Sever S, Buschbacher A, Aldenhoff JB, Göder R.. Effects of daytime naps on procedural and declarative memory in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(1):42–47. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lai M, Hegde R, Kelly S, et al. Investigating sleep spindle density and schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;307:114265. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wamsley EJ, Shinn AK, Tucker MA, et al. The effects of eszopiclone on sleep spindles and memory consolidation in schizophrenia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Sleep. 2013;36(9):1369–1376. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5665/sleep.2968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J.. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition with Psychotic Screen (SCID-I/P W/PSY SCREEN). NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33;quiz 34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walker MP, Stickgold R.. Sleep-dependent learning and memory consolidation. Neuron. 2004;44(1):121–133. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Walker MP, Stickgold R, Alsop D, Gaab N, Schlaug G.. Sleep-dependent motor memory plasticity in the human brain. Neuroscience. 2005;133(4):911–917. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Walker MP, Brakefield T, Seidman J, Morgan A, Hobson JA, Stickgold R.. Sleep and the time course of motor skill learning. Learn Mem. 2003;10(4):275–284. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1101/lm.58503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, Harding SM, Marcus CL, Vaughn BV.. The AASM Manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events. Am Acad Sleep Med. 2013;53(9):1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Warby SC, Wendt SL, Welinder P, et al. Sleep-spindle detection: crowdsourcing and evaluating performance of experts, non-experts and automated methods. Nat Methods. 2014;11(4):385–392. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nmeth.2855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Otsu N. Threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1979;9(1):62–66. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1109/tsmc.1979.4310076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nishida M, Walker MP.. Daytime naps, motor memory consolidation and regionally specific sleep spindles. PLoS One. 2007;2(4):e341. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0000341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kozhemiako N, Wang J, Jiang C, et al. Non-rapid eye movement sleep and wake neurophysiology in schizophrenia. Elife. 2022;11:e76211. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.7554/eLife.76211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Denis D, Baran B, Mylonas D, et al. NREM sleep oscillations and their relations with sleep-dependent memory consolidation in early course psychosis and first-degree relatives. Schizophr Res. 2024;274:473–485. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.schres.2024.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):663–667. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.4088/jcp.v64n0607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D.. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann Stat. 2001;29(4):1165–1188. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1214/aos/1013699998 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D.. False discovery rate-adjusted multiple confidence intervals for selected parameters. J Am Stat Assoc. 2005;100(469):71–81. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1198/016214504000001907 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Demirlek C, Bora E.. Sleep-dependent memory consolidation in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2023;254:146–154. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.schres.2023.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Purcell SM, Manoach DS, Demanuele C, et al. Characterizing sleep spindles in 11,630 individuals from the National Sleep Research Resource. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15930. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms15930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Floyd JA, Medler SM, Ager JW, Janisse JJ.. Age-related changes in initiation and maintenance of sleep: a meta-analysis. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(2):106–117. doi: https://doi.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV.. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1255–1273. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ferrarelli F. Sleep disturbances in schizophrenia and psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2020;221:1–3. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cohrs S. Sleep disturbances in patients with schizophrenia: impact and effect of antipsychotics. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(11):939–962. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.2165/00023210-200822110-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Krystal AD, Goforth HW, Roth T.. Effects of antipsychotic medications on sleep in schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(3):150–160. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f39703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kozhemiako N, Jiang C, Sun Y, et al. A Spectrum of Altered Non-Rapid Eye Movement Sleep in Schizophrenia. Sleep. Published online September 19, 2024:zsae218. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/sleep/zsae218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schilling C, Schlipf M, Spietzack S, et al. Fast sleep spindle reduction in schizophrenia and healthy first-degree relatives: association with impaired cognitive function and potential intermediate phenotype. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;267(3):213–224. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00406-016-0725-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. D’Agostino A, Castelnovo A, Cavallotti S, et al. Sleep endophenotypes of schizophrenia: slow waves and sleep spindles in unaffected first-degree relatives. NPJ Schizophr. 2018;4(1):2. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41537-018-0045-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Manoach DS, Pan JQ, Purcell SM, Stickgold R.. Reduced sleep spindles in schizophrenia: a treatable endophenotype that links risk genes to impaired cognition? Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(8):599–608. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Siapas AG, Wilson MA.. Coordinated interactions between hippocampal ripples and cortical spindles during slow-wave sleep. Neuron. 1998;21(5):1123–1128. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80629-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mölle M, Born J.. Slow oscillations orchestrating fast oscillations and memory consolidation. Prog Brain Res. 2011;193:93–110. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/B978-0-444-53839-0.00007-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Born J, Wilhelm I.. System consolidation of memory during sleep. Psychol Res. 2012;76(2):192–203. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00426-011-0335-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Latchoumane CFV, Ngo HVV, Born J, Shin HS.. Thalamic spindles promote memory formation during sleep through triple phase-locking of cortical, thalamic, and hippocampal rhythms. Neuron. 2017;95(2):424–435.e6. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Weinhold SL, Lechinger J, Timm N, Hansen A, Ngo HVV, Göder R.. Auditory stimulation in-phase with slow oscillations to enhance overnight memory consolidation in patients with schizophrenia? J Sleep Res. 2022;31(6):e13636. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jsr.13636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kaestner EJ, Wixted JT, Mednick SC.. Pharmacologically increasing sleep spindles enhances recognition for negative and high-arousal memories. J Cogn Neurosci. 2013;25(10):1597–1610. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1162/jocn_a_00433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mednick SC, McDevitt EA, Walsh JK, et al. The critical role of sleep spindles in hippocampal-dependent memory: a pharmacology study. J Neurosci. 2013;33(10):4494–4504. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3127-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Niknazar M, Krishnan GP, Bazhenov M, Mednick SC.. Coupling of thalamocortical sleep oscillations are important for memory consolidation in humans. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144720–e0144714. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0144720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Leminen MM, Virkkala J, Saure E, et al. Enhanced memory consolidation via automatic sound stimulation during non-REM sleep. Sleep. 2017;40(3):zsx003. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/sleep/zsx003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ngo HVV, Martinetz T, Born J, Mölle M.. Auditory closed-loop stimulation of the sleep slow oscillation enhances memory. Neuron. 2013;78(3):545–553. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ong JL, Lo JC, Chee NIYN, et al. Effects of phase-locked acoustic stimulation during a nap on EEG spectra and declarative memory consolidation. Sleep Med. 2016;20:88–97. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ong JL, Patanaik A, Chee NIYN, Lee XK, Poh JH, Chee MWL.. Auditory stimulation of sleep slow oscillations modulates subsequent memory encoding through altered hippocampal function. Sleep. 2018;41(5):zsy031. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/sleep/zsy031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Papalambros NA, Weintraub S, Chen T, et al. Acoustic enhancement of sleep slow oscillations in mild cognitive impairment. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(7):1191–1201. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1002/acn3.796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Papalambros NA, Santostasi G, Malkani RG, et al. Acoustic enhancement of sleep slow oscillations and concomitant memory improvement in older adults. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017;11(March):1–14. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Manoach DS, Mylonas D, Baxter B.. Targeting sleep oscillations to improve memory in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2020;221:63–70. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.schres.2020.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Moraes W, Piovezan R, Poyares D, Bittencourt LR, Santos-Silva R, Tufik S.. Effects of aging on sleep structure throughout adulthood: a population-based study. Sleep Med. 2014;15(4):401–409. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.11.791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Tucker M, McKinley S, Stickgold R.. Sleep optimizes motor skill in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):603–609. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03324.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Spencer RMC, Gouw AM, Ivry RB.. Age-related decline of sleep-dependent consolidation. Learn Mem. 2007;14(7):480–484. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1101/lm.569407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Pace-Schott EF, Spencer RMC.. Age-related changes in consolidation of perceptual and muscle-based learning of motor skills. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5(NOV):83. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Peters KR, Ray L, Smith V, Smith C.. Changes in the density of stage 2 sleep spindles following motor learning in young and older adults. J Sleep Res. 2008;17(1):23–33. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00634.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Loredo JS, Clausen JL, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE.. Night-to-night arousal variability and interscorer reliability of arousal measurements. Sleep. 1999;22(7):916–920. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/sleep/22.7.916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.