Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to explain the roles of physical and verbal aggression, emotional immaturity, and lying behavior in the predictive relationship between emotional abuse and delinquent tendencies among juveniles and students in Punjab, Pakistan.

Methods

Data were collected from 232 juveniles incarcerated in the Borstal Jails of Faisalabad and Bahawalpur. A comparative sample of 276 students from government schools was collected through purposive sampling. The comparative sample was matched for socioeconomic status, gender, location, and age. Translated (Urdu) versions of the standardized scales were used to measure the respective constructs. Path analysis was conducted to determine the mediating effects of lying (as a personality trait), emotional immaturity, and physical-verbal aggression on the relationship between emotional abuse and delinquent tendencies. Multigroup analysis was performed to determine the strength and significance of each path for juveniles and students.

Results

Emotional abuse positively predicted delinquent tendencies and emotional maturity, lying as a personality trait, and physical-verbal aggression mediated this relationship among juveniles and students. A decline in emotional maturity was a stronger predictor of delinquent tendencies among juveniles, whereas physical-verbal aggression played a stronger role for students.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the indirect effects of emotional abuse on delinquent tendencies. This study also highlights the intense effect of emotional abuse on juvenile delinquents’ emotional maturity and supports the importance of utilizing positive methods when dealing with adolescents, especially school personnel and clinical psychologists who interact with adolescents with problematic behaviors.

Keywords: Emotional abuse, Aggression, Delinquent tendencies, Juveniles, Students

INTRODUCTION

Extremism is a major concern in Pakistan. Juvenile delinquency is a criminal act committed by individuals under 18 years of age. Crime commencement at such a young age places individuals at risk for recidivism. Punjab is the most populous province in Pakistan and has a high reported incidence of juvenile delinquency compared to other provinces [1]. Studies conducted with juvenile delinquents have shown the influence of harsh parenting, child abuse, and aggressive behavior on the development of juvenile delinquency [2-5]. However, major limitations of these studies included the use of a qualitative design, small sample size, a focus on prevalence, and use of non-parametric analysis. The literature on juvenile delinquency is still developing in Pakistan, especially when it comes to explaining the phenomenon from multiple perspectives [6-9].

Sampling and the lack of advanced analysis are typically the main concerns in studies conducted in Punjab province of Pakistan. Punjab has two Borstal Institutions and Juvenile Jails (BIJJ) in Bahawalpur and Faisalabad. These institutions have a higher number of incarcerated juvenile delinquents compared with sampling based on juvenile delinquents imprisoned in different district jails of Punjab [1,10]. In district jails, the cohabitation of juveniles with adults, shorter duration of imprisonment, and convenient sampling make generalizability a main concern for research. Similarly, the literature typically focuses on a single sample and does not propose a comparative analysis, especially with reference to the mechanisms that could explain the pathways from predictors to delinquency [2-7].

Adolescence is a critical developmental stage characterized by rapid biological, hormonal, and psychological changes. During this time, individuals strive to achieve social independence and form their own identities [11,12]. This period of transition inherently brings about numerous stressors and strains, making adolescents particularly vulnerable to emotional disturbances such as anxiety, depression, and anger [13]. General strain theory (GST), as proposed by Robert Agnew, posits that strain can arise from sources such as the inability to achieve positively valued goals, removal of positively valued stimuli, and presentation of negative stimuli [14]. In adolescence, these sources of strain can include academic failure, loss of significant relationships, or exposure to abusive and harsh parenting. Strain generates negative emotions such as anger, frustration, and depression. These emotions create pressure and motivate individuals to take action to alleviate their distress. Owing to their developing emotional regulation and coping mechanisms, adolescents may struggle to manage these intense feelings effectively [12,13]. When avenues for positive coping are unavailable or ineffective, individuals may turn to negative coping strategies, such as delinquent behavior or aggression, to reduce their negative emotions. In the present study, GST was used as a theoretical framework in which emotional abuse is a major precursor to emotional immaturity, lying, and aggressive behavior as intervening mechanisms in explaining delinquent tendencies [14].

Rapid biological and hormonal changes during adolescence, the struggle to gain autonomy, and societal pressures make adolescence rebellious towards authority figures within their family, school, or society [15]. Such individuals often perceive stress or strain as unjust and intense, causing a decline in social control and exerting pressure on them to take matters into their own hands, resulting in deviant activities [14]. Among the different stressors that prevail in the home environment, psychological maltreatment is often difficult to distinguish from suboptimal parenting [16]. Researchers have noted that psychological maltreatment, as observed by children, is challenging to define [17]. In 2002, Glaser stated that psychological maltreatment is difficult to identify as it exists within a relationship instead of an event [16]. It often manifests as emotional distress or maladaptive behavior. Psychological maltreatment or emotional abuse is defined as a set of verbal or non-verbal behaviors in a parent–child relationship that includes commission (rejection and terrorizing) performed actively or passively, with or even without the intention to harm the child [16]. Emotional abuse negatively affects children’s physical, intellectual, social, and emotional development [12]. Parents’ maltreatment toward their children negatively affects the child’s development, making healing difficult [3]. It affects a child’s personality and disrupts their emotional and cognitive development depending on the intensity and duration of maltreatment [18].

Studies indicate that children who experience maltreatment often struggle to manage their emotions, making them more susceptible to emotional and behavioral issues [19]. Sexual offenders have been found to exhibit immature emotional congruence, meaning that they emotionally regress to a childlike state [20]. Emotional immaturity in adolescents can be influenced by factors in the home environment, such as parental control, social isolation, and unnecessary freedom or protectiveness [21]. Emotional maturity is defined as the ability to think and learn, which supports individuals during times of stress and hardship and prevents impulsive reactions [22]. It is determined by emotional stability, progress, social adjustment, personality integration, and a sense of independence [23]. When emotional maturity is not fully developed or is disrupted, it can result in emotional irritation and aggressive behaviors such as anger, harshness, and hostility. Emotionally immature individuals may exhibit childlike, egocentric, and argumentative behaviors and have a high sense of self-love and sympathy. They tend to become emotionally excited quickly and frustrated over minor issues and failures [24].

Studies have shown that maltreatment has long-lasting effects on children, especially on the development of delinquent tendencies [12,25]. This concept is crucial in the Pakistani context, where parental harshness and rude behavior are considered signs of authority and dominance, accompanied by their influential impact on teaching children discipline and morality [4,5]. Opinion formation and expression are not encouraged among adolescents in collectivistic cultures, but are often discouraged and snubbed at an early stage [26]. Even educated and well-established families use rejection, inattentiveness, and criticism as corrective measures to shape their children’s behavior in a socially desirable manner [5]. Social control theory maintains that inhumane treatment weakens the social bonds between relationships [27] and lowers the sense of security and communication in family relations. Children tend to show conforming behaviors on the surface, but deep down, they deceive their closest bonds.

Children’s perceptions of their parents and parenting styles influence the personalities of children with conduct disorders [28]. Children who score high on the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ) lie scale show symptoms of conduct disorders and have negative perceptions of their parents [29]. Children often engage in polite (socially acceptable) and instrumental (socially unacceptable) lying paradigms. Instrumental liars are young children with high social skills but low theory-of-mind scores, whereas polite liars are older and have high theory-of-mind scores. These findings suggest that children use lies selectively to achieve their social goals, and that their behavior may change from self-motivated to other-motivated as they age, reflecting the transition toward socially accepted behavior [30]. Taking the construct of a lie as representative of conformity, according to Edwin Sutherland’s differential association theory proposed in 1939 [31], criminal behavior is learned socially through attachment to antisocial, abusive, and law-breaking people. Furthermore, it progresses through imitation or internalization. Researchers [32] have argued that lying at an early age is a strong and robust correlate of delinquent behavior and is associated with various delinquent behaviors, including late bedtimes, spending time with delinquent friends, and concealing one’s whereabouts. Dykstra [33] noted that lying in itself poisons an individual’s social relationships, causing anger and distrust. Lying behavior show less parental regard and stronger loyalty toward other groups (e.g., deviant friends).

Jhangiani and Tarry [34] have defined aggressive behavior as actions intended to hurt and frighten others. Social learning theory supports the notion that parental maltreatment and abusive behavior teaches children that aggression is an acceptable form of action. In Pakistan, where society is marked by injustice and intolerance, exposure to daily violence is common. Mushtaq and Kayani [9] identified factors such as revenge, joy, materialism, frustration, and academic injustice as contributors to adolescent aggression in Pakistan. Physically aggressive children are at risk for violent crime, drug abuse, and depression, and can become victims of abuse and neglectful parenting [35]. Boys often exhibit aggression due to maltreatment, and behavioral excesses such as using physical and verbal aggression to disturb others can lead to delinquency [36,37]. Emotional rejection by one’s parents is a significant risk factor for aggressive and delinquent behaviors [38]. The family environment, especially if characterized by conflict, hostility, and abuse, can teach children aggressive, deviant, and violent behavior [39].

The present study assumes that emotional abuse predicts emotional immaturity, lying tendencies, and aggressive behavior as core pathways, with significant predictive effects on delinquent tendencies among adolescents in Pakistan. Juvenile delinquents and students were compared to determine the condition or reason why some individuals experience emotional abuse but do not develop juvenile delinquency despite having delinquent tendencies. Thus, the aims of this study are as follows:

1) To establish the psychometric properties of the instruments used for the current study sample.

2) To test the mediating roles of emotional maturity, lying, and physical and verbal aggression in the relationship between emotional abuse and delinquent tendencies.

3) To differentiate between the proposed paths in juvenile and student samples.

METHODS

Sample

To meet the objectives of this study, information was collected from 508 respondents, including 232 juvenile delinquents from the two BIJJs in Punjab and 276 students from government schools in the respective cities of Bahawalpur and Faisalabad, to control the impact of location. Therefore, in Bahawalpur, data were collected from 87 delinquents, as one participant was not sufficiently mentally stable to provide data, and five individuals were not identifiable or accessible owing to an outdated list of juvenile delinquents. In Faisalabad, data were collected from 145 juveniles, as two were not sufficiently mentally stable for collecting data and three were receiving treatment at the hospital on the premises of Faisalabad. The comparative group was selected on a similar basis of area, gender, age, and monthly income considered as socioeconomic status (SES). The control group was recruited from government schools in Bahawalpur (n=100) and Faisalabad (n=176).

Sample inclusion criteria

Participants were included based on the presence of juvenile delinquents in the BIJJs of Punjab during data collection. Only two BIJJs work for the rehabilitation of juvenile delinquents in Punjab province: BIJJ Bahawalpur and BIJJ Faisalabad. For security reasons, the authorities were granted a short time for data collection. Voluntary participation was considered a basic parameter for data collection. Data were collected from schools in the same cities after controlling for age, gender, monthly income, and location differences.

Sample exclusion criteria

Juvenile delinquents detained outside BIJJ, such as those in district or central jails, were excluded. Female juvenile delinquents were not included in the study because no rehabilitation institutions for girls are in Punjab or any other area of Pakistan.

Instruments

Emotional Maturity Scale

The Emotional Maturity Scale was developed by Singh and Bhargava [23] and measures five broad aspects of emotional maturity: emotional stability, emotional progression, social adjustment, personality integration, and independence. It is a self-report scale with 48 items, and responses are provided on a 5-point Likert scale (5=always, 4=mostly, 3=uncertain, 2=usually, 1=never). A high score on the scale indicates a high degree of emotional maturity, and vice versa. Each factor has 10 items, except for the fifth factor, which has eight items. The possible score range for the composite scale is 48–240.

Physical and Verbal Aggression Scale

A short version of the Physical and Verbal Aggression Scale was used to measure the physical and verbal dimensions of aggression [11]. This 9-item scale evaluates the behaviors of children and young adolescents aimed at physically and verbally harming others. It includes items such as ‘‘I kick or punch” or “I say bad things about others.” Items are rated on a 5-point scale (1=never, 2=a few times, 3=sometimes, 4=many times, and 5=always). The sum of the scores for all items provides a composite score for physically and verbally aggressive behavior. The possible score range is 5–45. The author reported the alpha reliability of the scale as α=0.80. In this study, this scale was used in Pakistan for the first time and translated into Urdu.

Emotional abuse scale

The emotional abuse scale used in this study is a subscale of the Child Abuse Scale developed by Malik and Shah [2]. The emotional abuse scale contains 14 items. The response format is a 4-point rating scale in which response categories range from 1=“never” to 4=“always.” The sum of the 14-item scores is used for the total score, with a range of 14–56. The author reported the alpha reliability coefficient for the emotional abuse subscale as α=0.90 [2].

EPQ-lie subscale

In this study, the translated version of the lie scale was taken from the EPQ developed by Eysenck and Eysenck in 1976 and translated by Naqvi and Kamal [40]. It assesses lying when the respondent endorses a set of rarely performed acts as habitual and when the respondent denies frequently performed undesirable acts. The EPQ-lie subscale contains 20 items. Low scores indicate that the respondent is not dissimulating, whereas high scores indicate a tendency to provide fabricated or socially desirable responses. The alpha reliability of this scale has been reported as 0.70 [40].

Revised Self-Reported Delinquency Scale

The Self-Reported Delinquency Scale comprises 27 items measuring different aspects of delinquency, including theft, drug abuse, lying, non-compliance with adults, police encounters and escape, violence-related delinquency, cheating and gambling, and sex-related delinquency (harassment, homosexuality, and heterosexuality) [41]. The factor structure of the scale was revised to include six subscales measuring risk-taking, sex-related, threat-related, police encounters, drugrelated, and attention-seeking delinquent tendencies [10]. The scale comprises all positively stated statements that measure delinquent behavior. Responses are provided on a 5-point Likert scale (0=“never,” 1=“one time,” 2=“2–5 times,” 3=“5–10 times,” and 4=“10 or more times”). The higher the score on the Revised Self-Reported Delinquency Scale subscale, the stronger the tendency for a particular delinquency. The range of alpha reliability values for the subscales has been reported as 0.71–0.78 [10].

Procedure

The institutional heads of the jails and schools provided permission for the study. Separate informed consent was obtained from each respondent to ensure their willingness to participate. Before obtaining informed consent, the researcher’s institution and the researcher were introduced in detail, which included the qualifications of the researcher, purpose of the study, and its impact on society overall. Group administration was performed using student and juvenile delinquent samples. Interviews were conducted with illiterate juvenile delinquents. Detailed instructions were provided, including the number of questions on the demographic sheet and how to answer each question. Respondents were informed that they could leave at any time during data collection. Executive District Officers-Education and the principals of government schools in Bahawalpur and Faisalabad permitted data collection, and the questionnaires were approved by the authorities before data were collected. The researcher assured the confidentiality of the information and explained that the data would only be used for research purposes. Detailed instructions on how to read and select options from the response format were provided. The data were analyzed using AMOS (22 version; IBM, New York, USA).

Compliance with ethical standards

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of National Institute of Psychology Research Committee. The study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee (National Ethics Committee for Psychological Research [NECPR]) and certified to be performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from the institutional head and each participant separately after describing the purpose of the research and the assurance that data would be used for research purposes only, would not be shared without their consent, and that their identity would be kept anonymous.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the demographic variables of both samples. The participants’ ages ranged from 12 to 18 years among juvenile delinquents (mean [M]=16.81 years, standard deviation [SD]=2.03 years) and students (M=16.32 years, SD=1.71 years). Illiteracy was more prevalent among juvenile delinquents. SES ranged from 500 Pakistani rupees (PKRs) to 120000 PKRs (1.8 to 431 USD) in juvenile delinquents (M=18505.07 PKRs, SD=17391.28 PKRs) and students (M=23966.02 PKRs, SD=20037.78 PKRs). Standardized instruments were used to measure the psychological constructs. Table 2 presents the psychometric properties of the translated instruments.

Table 1.

Description of demographic characteristics as a percentage of the sample (n=508)

| Characteristics | Juvenile delinquents (n=232) | Students (n=276) |

|---|---|---|

| Current age | ||

| 12-14 yr | 26 (11.21) | 27 (9.78) |

| 15-16 yr | 75 (31.90) | 129 (46.74) |

| 17-18 yr | 132 (56.90) | 120 (43.48) |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 81 (34.91) | - |

| 1 Class-Primary | 56 (24.14) | - |

| 6 Class-Matric | 87 (37.50) | 150 (54.35) |

| 1st Year-Bachelors | 8 (3.45) | 126 (45.65) |

| Family system | ||

| Nuclear | 124 (53.45) | 151 (54.71) |

| Joint | 108 (46.55) | 123 (44.57) |

| Missing | - | 2 (0.72) |

| Area of living | ||

| Rural | 144 (62.07) | 61 (22.10) |

| Urban | 87 (37.50) | 215 (77.90) |

| Missing | 1 (0.43) | - |

| Socioeconomic status* | ||

| 500-10000 PKRs | 92 (39.66) | 68 (24.64) |

| 10001-20000 PKRs | 67 (28.88) | 97 (35.14) |

| 20001-50000 PKRs | 43 (18.53) | 76 (27.54) |

| 50001-120000 PKRs | 12 (5.17) | 18 (6.52) |

| Missing | 18 (7.76) | 17 (6.16) |

Values are presented as n (%). *Socioeconomic status was calculated on the basis of monthly income. PKRs, Pakistani rupees

Table 2.

Psychometric properties of the main study variables (n=508)

| Sr. no. | Variables | Items | α | M±SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potential | Actual | |||||

| 1. | Revised Self-reported Delinquency Scale | 27 | 0.92 | 15.60±17.08 | 0-108 | 0-99 |

| 2. | Risk taking | 8 | 0.77 | 5.39±5.78 | 0-32 | 0-31 |

| 3. | Sex related | 5 | 0.78 | 3.47±4.42 | 0-20 | 0-20 |

| 4. | Threat related | 3 | 0.73 | 1.15±2.25 | 0-12 | 0-12 |

| 5. | Police encountering | 3 | 0.71 | 1.67±2.45 | 0-12 | 0-12 |

| 6. | Drugs related | 3 | 0.73 | 1.55±2.70 | 0-12 | 0-12 |

| 7. | Attention seeking | 5 | 0.71 | 2.38±3.36 | 0-20 | 0-20 |

| 8. | Emotional Maturity Scale | 46 | 0.91 | 86.59±24.91 | 46-230 | 46-204 |

| 9. | Emotional stability | 9 | 0.71 | 18.38±6.35 | 9-45 | 9-45 |

| 10. | Emotional progression | 10 | 0.75 | 19.64±6.81 | 10-50 | 10-47 |

| 11. | Social adjustment | 9 | 0.67 | 15.39±5.11 | 9-45 | 9-45 |

| 12. | Personality integration | 10 | 0.78 | 16.86±6.41 | 10-50 | 10-50 |

| 13. | Independence | 8 | 0.71 | 16.34±5.86 | 8-40 | 8-40 |

| 14. | Emotional abuse scale | 14 | 0.86 | 19.31±5.98 | 14-56 | 14-49 |

| 15. | Physical and Verbal Aggression | 9 | 0.86 | 15.26±6.50 | 9-45 | 9-45 |

| 16. | Lie (EPQ) | 17 | 0.77 | 21.94±3.46 | 17-34 | 17-32 |

EPQ, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; M, mean; SD, standard deviation; Sr. no., serial number

Table 2 shows the psychometric properties of the instruments translated into Urdu for the main study. Internal scale consistency was measured based on alpha reliabilities, which were within acceptable ranges for this research.

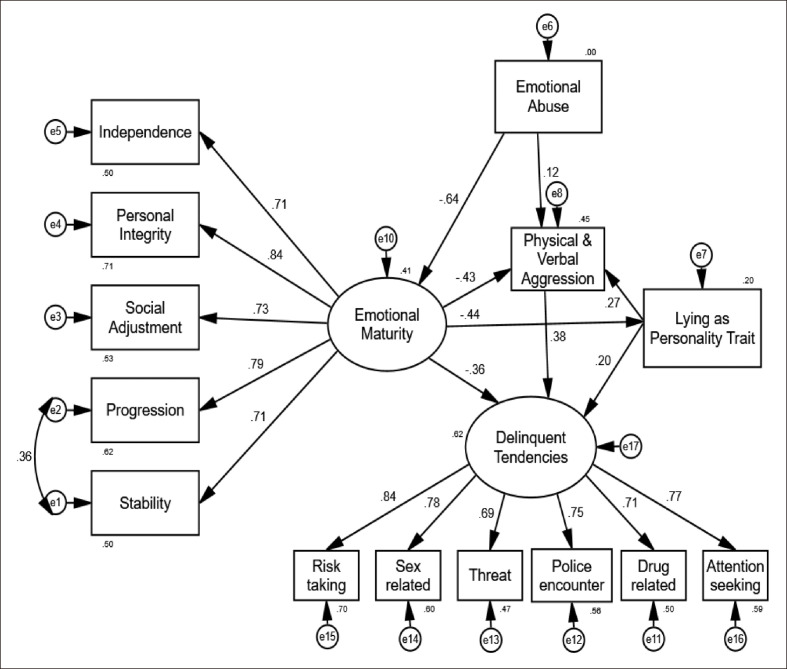

A hybrid model (comprising both measurement and structural models) was used to examine the mediating effects of the variables on the relationship between emotional abuse and delinquent tendencies. Table 3 and Fig. 1 present the results. Covariances were added between the errors of conceptually interrelated subscales. Modification indices based on the suggested paths from emotional maturity to personality traits (lie), emotional maturity to physical and verbal aggression, and lying to physical and verbal aggression were added. Substantial theoretical and logical evidence supports this path. Model fit also improved significantly. An illustrated representation of the fitted model is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 3.

Predicting delinquent tendencies from emotional abuse through path analysis

| Paths | Direct | Indirect | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| EA → EM | -0.64 (-0.70, -0.58)*** | - | -0.64 (-0.70, -0.58)*** |

| EA → Lie | - | 0.28 (0.23, 0.33)*** | 0.28 (0.23, 0.33)*** |

| EA → PVA | 0.12 (0.02, 0.23)*** | 0.35 (0.28, 0.43)*** | 0.47 (0.39, 0.54)*** |

| EA → DT | - | 0.47 (0.40, 0.53)*** | 0.47 (0.40, 0.53)*** |

| EA → ASD | - | 0.36 (0.30, 0.42)*** | 0.36 (0.30, 0.42)*** |

| EA → DRD | - | 0.39 (0.33, 0.45)*** | 0.39 (0.33, 0.45)*** |

| EA → SRD | - | 0.36 (0.30, 0.41)*** | 0.36 (0.30, 0.41)*** |

| EA → THR | - | 0.32 (0.26, 0.38)*** | 0.32 (0.26, 0.38)*** |

| EA → PEN | - | 0.35 (0.29, 0.41)*** | 0.35 (0.29, 0.41)*** |

| EA → DRT | - | 0.33 (0.27, 0.39)*** | 0.33 (0.27, 0.39)*** |

| EA → EMI | - | -0.46 (-0.51, -0.40)*** | -0.46 (-0.51, -0.40)*** |

| EA → PI | - | -0.54 (-0.59, -0.49)*** | -0.54 (-0.59, -0.49)*** |

| EA → SA | - | -0.47 (-0.52, -0.41)*** | -0.47 (-0.52, -0.41)*** |

| EA → EMP | - | -0.51 (-0.56, -0.45)*** | -0.51 (-0.56, -0.45)*** |

| EA → EMS | - | -0.46 (-0.51, -0.40)*** | -0.46 (-0.51, -0.40)*** |

| EM → Lie | -0.44 (-0.51, -0.37)*** | - | -0.44 (-0.51, -0.37)*** |

| EM → PVA | -0.43 (-0.54, -0.31)*** | -0.11 (-0.16, -0.09)*** | -0.54 (-0.64, -0.44)*** |

| EM → DT | -0.36 (-0.48, -0.25)*** | -0.29 (-0.36, -0.24)*** | -0.66 (-0.74, -0.56)*** |

| EM → ASD | - | -0.50 (-0.58, -0.42)*** | -0.50 (-0.58, -0.42)*** |

| EM → DRD | - | -0.55 (-0.62, -0.47)*** | -0.55 (-0.62, -0.47)*** |

| EM → SRD | - | -0.51 (-0.58, -0.43)*** | -0.51 (-0.58, -0.43)*** |

| EM → THR | - | -0.45 (-0.53, -0.37)*** | -0.45 (-0.53, -0.37)*** |

| EM → PEN | - | -0.49 (-0.57, -0.41)*** | -0.49 (-0.57, -0.41)*** |

| EM → DRT | - | -0.46 (-0.54, -0.38)*** | -0.46 (-0.54, -0.38)*** |

| EM → EMI | 0.71 (0.65, 0.75)*** | - | 0.71 (0.65, 0.75)*** |

| EM → PI | 0.84 (0.80, 0.88)*** | - | 0.84 (0.80, 0.88)*** |

| EM → SA | 0.73 (0.67, 0.79)*** | - | 0.73 (0.67, 0.79)*** |

| EM → EMP | 0.78 (0.74, 0.83)*** | - | 0.78 (0.74, 0.83)*** |

| EM → EMS | 0.71 (0.64, 0.76)*** | - | 0.71 (0.64, 0.76)*** |

| Lie → PVA | 0.27 (0.19, 0.34)*** | - | 0.27 (0.19, 0.34)*** |

| Lie → DT | 0.20 (0.13, 0.28)*** | 0.10 (0.06, 0.15)*** | 0.30 (0.22, 0.38)*** |

| Lie → ASD | - | 0.23 (0.17, 0.29)*** | 0.23 (0.17, 0.29)*** |

| Lie → DRD | - | 0.25 (0.18, 0.32)*** | 0.25 (0.18, 0.32)*** |

| Lie → SRD | - | 0.23 (0.17, 0.30)*** | 0.23 (0.17, 0.30)*** |

| Lie → THR | - | 0.21 (0.15, 0.26)*** | 0.21 (0.15, 0.26)*** |

| Lie → PEN | - | 0.23 (0.16, 0.29)*** | 0.23 (0.16, 0.29)*** |

| Lie → DRT | - | 0.21 (0.15, 0.27)*** | 0.21 (0.15, 0.27)*** |

| PVA → DT | 0.38 (0.27, 0.49)*** | - | 0.38 (0.27, 0.49)*** |

| PVA → ASD | - | 0.29 (0.20, 0.38)*** | 0.29 (0.20, 0.38)*** |

| PVA → DRD | - | 0.31 (0.22, 0.41)*** | 0.31 (0.22, 0.41)*** |

| PVA → SRD | - | 0.29 (0.21, 0.38)*** | 0.29 (0.21, 0.38)*** |

| PVA → THR | - | 0.26 (0.18, 0.34)*** | 0.26 (0.18, 0.34)*** |

| PVA → PEN | - | 0.28 (0.20, 0.37)*** | 0.28 (0.20, 0.37)*** |

| PVA → DRT | - | 0.27 (0.19, 0.35)*** | 0.27 (0.19, 0.35)*** |

| DT → ASD | 0.77 (0.71, 0.81)*** | - | 0.77 (0.71, 0.81)*** |

| DT → DRD | 0.84 (0.80, 0.87)*** | - | 0.84 (0.80, 0.87)*** |

| DT → SRD | 0.78 (0.73, 0.82)*** | - | 0.78 (0.73, 0.82)*** |

| DT → THR | 0.69 (0.62, 0.74)*** | - | 0.69 (0.62, 0.74)*** |

| DT → PEN | 0.75 (0.70, 0.79)*** | - | 0.75 (0.70, 0.79)*** |

| DT → DRT | 0.70 (0.63, 0.76)*** | - | 0.70 (0.63, 0.76)*** |

Values are presented as β (95% CI). ***p<0.001. ASD, attention seeking; CI, bias corrected 95% confidence interval; DRD, drug related; DRT, risk taking; DT, delinquent tendencies; EA, emotional abuse; EM, emotional maturity; EMI, independence; EMP, progression; EMS, stability; PEN, police encountering; PI, personal integrity; PVA, physical and verbal aggression; SA, social adjustment; SRD, sex related; THR, threat

Fig. 1.

Paths explaining the effect of emotional abuse on delinquent tendencies among study samples.

Fig. 1 shows the paths that connect emotional abuse to delinquent tendencies in the combined sample. All observed variables are shown in rectangles, whereas the latent variables are described in ovals. Standardized maximum likelihood parameter estimates and error variance measuring the residual variance component were used to indicate the amount of unexplained variance. The model fit indices for the proposed model were χ2 ratio=2.63, comparative fit index=0.97, Tucker–Lewis index=0.96, and root mean square error of approximation=0.04, with PCLOSE=0.999. Fig. 1 shows that emotional maturity, physical and verbal aggression, and lying were personality traits that mediate the relationship between emotional abuse and delinquent tendencies. The modification indices indicated that emotional maturity predicts lying as a personality trait and aggression. Trait lying also predicted physical and verbal aggression, which was directly linked to delinquent tendencies.

To present a detailed path analysis for both the direct and indirect paths, the values in Table 3 indicate that lying as a personality trait had an indirect effect on delinquent tendencies, whereas physical and verbal aggression had significant direct and indirect effects. Emotional maturity also had indirect and direct effects on physical and verbal aggression and delinquent tendencies. Further, a multigroup analysis was performed to differentiate the levels of strength of the paths in the juvenile delinquent and student samples.

As a prerequisite for the multigroup analysis, emotional maturity and delinquent tendencies were considered observed variables. The findings of the global test showed a significant chi-squared difference (χ2 difference=52.39 (8), p<0.001) between the unconstrained (χ2(df)=37.70 (4)) and constrained model (χ2(df)=90.09 (12)). The results of the local tests are compared in Table 4.

Table 4.

Differential paths for juvenile delinquents and students for proposed model

| Path name | Juveniles beta | Students beta | Difference in betas | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA → EM | 0.58*** | 0.53*** | 0.05** | The positive relationship between EA and EM is stronger for juveniles. |

| EM → Lie | 0.39*** | 0.48*** | -0.09* | The positive relationship between EM and Lie is stronger for students. |

| EA → PVA | 0.09 | 0.20*** | -0.11 | The positive relationship between EA and PVA is only significant for students. |

| Lie → PVA | 0.31*** | 0.36*** | -0.05 | There is no difference. |

| EM → PVA | 0.44*** | 0.22*** | 0.22*** | The positive relationship between EM and PVA is stronger for juveniles. |

| EM → DT | 0.32*** | 0.09 | 0.23*** | The positive relationship between EM and DT is stronger for juveniles. |

| Lie → DT | 0.29*** | 0.35*** | -0.06 | There is no difference. |

| PVA → DT | 0.31*** | 0.40*** | -0.09 | There is no difference. |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. DT, delinquent tendencies; EA, emotional abuse; EM, emotional maturity; PVA, physical and verbal aggression

The findings presented in Table 4 show that for juvenile delinquents, the inverse relationship between emotional abuse and emotional maturity, emotional maturity, and physical and verbal aggression, and further with delinquent tendencies, is stronger than that in students. This indicates that decreased emotional maturity is the main reason for aggression and delinquent tendencies among juveniles. For students, decreased emotional maturity predicts lying as a personality trait, whereas emotional abuse predicts further physical and verbal aggression. Emotional maturity was not found to have a central role in the relationship between emotional abuse and delinquent tendencies among students; however, it was very important for juvenile delinquents. The effects of emotional abuse on physical and verbal aggression were mediated by a decrease in emotional maturity and an increase in lying traits among juveniles.

DISCUSSION

The circumstances in Pakistan have long been characterized by political and economic instability. With the continuous deterioration of the gross domestic product, challenges such as unemployment, poverty, and unplanned urbanization have negative effects on not only adults but also adolescents, indirectly and directly affected by these macro-level societal issues [10]. Disturbances in the home environment can lead to the development of deep-rooted antisocial behaviors [2,4,7]. The purpose of the current study was to explain the relationship between emotional abuse and delinquent tendencies through the paths of emotional immaturity, trait lying, and aggression. Path analysis and model testing showed that emotional abuse led to delinquent tendencies through emotional immaturity, lying, and physical and verbal aggression.

The present study focused solely on boys, as BIJJs are only authorized to accommodate male juveniles [1]. Therefore, the findings of the study were thoroughly affected by the respondents’ male gender. In Pakistani culture, sons are often given special treatment that fosters sense of entitlement and are treated insensitively in the society to make them strong breadwinners of the family [2,3,5,7]. Typically, male adolescents in Pakistan lack direct guidance and self-discipline [42,43]. Being male is a privilege in a collectivistic culture, where inheritance, power dominance, and nutritional opportunities are provided to a specific gender. Disinhibition and impulsiveness among males are also attributed to the cultural context [10,41]. Adolescence is characterized by emotional instability and growth. Therefore, strain during this period has longterm effects on individuals.

The findings of this study are consistent with those reported in the Western literature. Specifically, emotional immaturity acts as a pivotal mediator in linking emotional abuse and delinquency among adolescents in Pakistan [42,44]. Behaviors such as rejection, terrorizing others, and neglect, which constitute emotional abuse, profoundly disrupt adolescents’ emotional and psychological development, leading to emotional immaturity. This state, characterized by heightened emotional reactivity and poor emotional regulation, makes adolescents more susceptible to engaging in delinquent behaviors as maladaptive coping mechanisms [45]. In Pakistan, with high societal and familial pressures and often harsh parental discipline, the impact of emotional abuse on emotional development is particularly significant [7]. Emotional immaturity in these adolescents often manifests as aggression, deceit, and defiance, which are hallmarks of delinquent behavior. Therefore, addressing emotional immaturity through therapeutic interventions is essential for breaking the cycle of abuse and delinquency, promoting healthier emotional development, and reducing criminal behavior among Pakistani youth [45].

The lens of lying or deception adds more layers to the relationship between emotional abuse, emotional immaturity, and delinquent tendencies. The literature shows that the EPQ can also be used to assess a stable personality trait, measuring a lack of insight or deceptiveness [46]. Studies have shown that to achieve their social goals, children use deception to show acceptable behavior while concealing their acts and intentions through instrumental and polite lies [30]. Lying about everyday activities often reflects a child’s immaturity, and the present study found that emotional immaturity predicts lying as a trait in which deception becomes a stable characteristic. The relationship between lies (considered social desirability) and aggression is explained by a child’s social desirability under the supervision of abusive parents, which significantly predicts all forms of aggression [46]. Thus, consistent with the findings of the present study, emotional abuse leads to delinquent tendencies either directly [47] or through physical and verbal aggression [48] and lying [49], where a path also leads from lying to physical and verbal aggression.

Similarly, Berzenski and Yates [18] found that the relationship between emotional abuse and violence is mediated by behavioral components (i.e., impulsivity). The literature also supports the mediating role of aggression between stressors and crime [50,51]. Pakistani studies indirectly indicate that 43% (24% related to revenge and 19% to land disputes) of crimes during adolescence are based on handling a situation aggressively [6,7]. Khurshid et al. [7] reported that disrupted family relationships increase the level of aggression and severity of crime among juvenile delinquents. Shahid and Mushtaq [8] also reported a significant relationship between clinical anger and deviant behavior. The current study validates these findings by providing a holistic view in which emotional abuse predicts delinquent tendencies through emotional and behavioral components. The current study also contributes to the domestic literature by focusing on students, whereas previous studies have explored aggression or delinquent tendencies among juvenile delinquents and children living on the streets [6-8,41].

This study contributes to the literature by examining the serial mediation between emotional abuse and delinquent tendencies in multiple aspects. It is important to highlight that a rebellious attitude typically indicates antisocial behavior. Thus, in Eastern countries, conformity is a desirable characteristic and culturally considered a protective factor against delinquency [52,53]. The findings of the current study contradict these assumptions and provide a perspective in which parental emotional abuse affects children’s emotional development [48]. Children show conforming or agreeable behavior, but from a holistic perspective, this passive conformity predicts aggression and delinquency among adolescents in Pakistan. This also suggests that conformity to emotionally abusive parents is shown as an escape to shorten the abusive interaction [43,54,55], whereas the current study contributes to the literature showing that emotional immaturity exhibited through lying/deception further strengthens aggressive and delinquent tendencies among juvenile delinquents and students in Punjab, Pakistan. For practitioners, this study suggests the need to provide emotion-focused therapeutic interventions in correctional institutions. Educationists need to internalize values and beliefs, as superficial conformity can lead to frustration and delinquent behavior.

CONCLUSION

The present study found that for juvenile delinquents, emotional immaturity mediates the relationship between emotional abuse and delinquent tendencies. Displays of delinquent tendencies became more evident among juveniles when they showed a predictive relationship between emotional immaturity and deceptive traits. For students, the physical and verbal aggression paths more strongly predicted delinquent tendencies due to emotional abuse. This study used a large comparative sample to test the intervening relationships among juvenile delinquents in Pakistan.

Limitations and suggestions

One limitation of this study is that it included data from only two cities in Punjab, Pakistan. For an accurate representation, more data from multiple cities are required. The model was developed using a cross-sectional design. Thus, validation of the model using a longitudinal research design is highly recommended. The use of self-report measures for adolescents has inherent limitations in that adolescents have underdeveloped insights into their selves and behaviors. When participants aged 12–18 years assess their own levels of aggression, emotional abuse, lying, and delinquent tendencies, the objectivity of the evaluation may be significantly compromised. Thus, parental reporting can be used to verify adolescents’ behavioral components. Similarly, for future studies, it is recommended that official data be used to verify self-reported details. This study validated GST in adolescents in Pakistan and suggested that personality components could further clarify the model. This study is limited to a psychological perspective only, whereas incorporating social factors such as antisocial peers or neighborhoods and antisocial personality traits can explain the phenomenon of delinquency on a broader spectrum.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for assistance in data collection Mubushrah Ishfaq and Namood-e-Sahar for updating references in the article.

Footnotes

Availability of Data and Material

The data included information from minors that are incarcerated in juvenile jails of Punjab, Pakistan. Thus, original data can only be shared after obtaining third party (IG Prison Punjab) permission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Nimrah Ishfaq, Anila Kamal. Data curation: Nimrah Ishfaq. Formal analysis: Nimrah Ishfaq. Methodology: Anila Kamal. Project administration: Anila Kamal. Resources: Nimrah Ishfaq. Software: Nimrah Ishfaq. Supervision: Anila Kamal. Validation: Anila Kamal. Visualization: Nimrah Ishfaq. Writing—original draft: Nimrah Ishfaq. Writing—review & editing: Anila Kamal.

Funding Statement

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Murtaza A, Nawaz Manj Y, Hashmi AH, Zara MU, Akhtar M, Asfand A. Causes leading to juvenile delinquency: a case study conducted at Punjab, Pakistan. Khaldunia J Soc Sci. 2021;1:41–52. doi: 10.36755/khaldunia.v1i1.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malik FD, Shah AA. Development of child abuse scale: reliability and validity analyses. Psychol Dev Soc. 2007;19:161–178. doi: 10.1177/097133360701900202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fayaz I. Child abuse: effects and preventive measures. Int J Indian Psychol. 2019;7:871–884. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik F. Determinants of child abuse in Pakistani families: parental acceptance-rejection and demographic variables. Int J Bus Soc Sci. 2010;1:67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadiq S, Bashir A. Parental discipline and harsh punishment as a predictor of delinquent tendencies among adolescents in Pakistan. Int J Technol Res Sci. 2018;2:823–828. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahmood K, Cheema MA. Empirical analysis of juvenile crime in Punjab, Pakistan. Pak J Life Soc Sci. 2004;2:136–138. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khurshid M, Loona MI, Bhatti MI. Impact of family relations on aggression among juvenile delinquents in Punjab, Pakistan. Asian J Int Peace Sec. 2021;5:34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahid A, Mushtaq A. Mediating role of negative emotions in association between imprisonment strain and institutional misconduct among juvenile offenders of Punjab prisons. Pak J Criminol. 2023;15:225–244. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mushtaq M, Kayani MM. Exploring the factors causing aggression and violence among students and its impact on our social attitude. Educ Res Int. 2013;2:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishfaq N, Kamal A. Empirical evidence of multi-facets of delinquency in Pakistan: revised self-reported delinquency scale. Pak J Psychol Res. 2019;34:115–137. doi: 10.33824/PJPR.2019.34.1.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caprara GV, Pastorelli C. Early emotional instability, prosocial behaviour, and aggression: some methodological aspects. Eur J Pers. 1993;7:19–36. doi: 10.1002/per.2410070103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel LJ, Welsh BC. Juvenile delinquency: theory, practice, and law. 12th ed. Cengage Learning; Belmont: 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alcaide M, Garcia OF, Queiroz P, Garcia F. Adjustment and maladjustment to later life: evidence about early experiences in the family. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1059458. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1059458.8d5895b673a74fb295fa4dba811af974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brezina T. General strain theory [Internet] Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2017. [cited 2024 Apr 20]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.249 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alderman EM, Breuner CC, Grubb LK, Powers ME, Upadhya K, Wallace SB. Unique needs of the adolescent. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20193150. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hibbard R, Barlow J, MacMillan H. Psychological maltreatment. Pediatrics. 2012;130:372–378. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slep AMS, Glaser D, Manly JT. Psychological maltreatment: an operationalized definition and path toward application. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;134:105882. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berzenski SR, Yates TM. A developmental process analysis of the contribution of childhood emotional abuse to relationship violence. J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma. 2010;19:180–203. doi: 10.1080/10926770903539474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abrams Z. What neuroscience tells us about the teenage brain. Mon Psychol. 2022;53:66. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McPhail IV, Nunes KL, Hermann CA, Sewell R, Peacock EJ, Looman J, et al. Emotional congruence with children: are implicit and explicit child-like self-concept and attitude toward children associated with sexual offending against children? Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47:2241–2254. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rukmini S, Ramaswamy C. Relationship between emotional maturity and academic achievement among adolescents. Int J Indian Psychol. 2021;9:268–274. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hermann CA, McPhail IV, Helmus LM, Hanson RK. Emotional congruence with children is associated with sexual deviancy in sexual offenders against children. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2017;61:1311–1334. doi: 10.1177/0306624X15620830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh Y, Bhargava M. Manual for emotional maturity scale. National Psychological Corporation; Agra: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piccerillo L, Digennaro S. Adolescent social media use and emotional intelligence: a systematic review. Adolescent Res Rev. In press 2024 doi: 10.1007/s40894-024-00245-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller RT, Thornback K, Bedi R. Attachment as a mediator between childhood maltreatment and adult symptomatology. J Fam Viol. 2012;27:243–255. doi: 10.1007/s10896-012-9417-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan Y, Gauvain M, Schwartz SJ. Do parents' collectivistic tendency and attitudes toward filial piety facilitate autonomous motivation among young Chinese adolescents? Motiv Emot. 2013;37:701–711. doi: 10.1007/s11031-012-9337-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costello BJ, Laub JH. Social control theory: the legacy of Travis Hirschi's causes of delinquency. Annu Rev Criminol. 2020;3:21–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev-criminol-011419-041527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mak MCK, Yin L, Li M, Cheung RYH, Oon PT. The relation between parenting stress and child behavior problems: negative parenting styles as mediator. J Child Fam Stud. 2020;29:2993–3003. doi: 10.1007/s10826-020-01785-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sen A, Mukherjee T. A study of personality dimensions, perception of parents and parenting style in conduct disorder children. Indian J Clin Psychol. 2012;39:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavoie J, Yachison S, Crossman A, Talwar V. Polite, instrumental, and dual liars: relation to children's developing social skills and cognitive ability. Int J Behav Dev. 2017;41:257–264. doi: 10.1177/0165025415626518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boman JH, 4th, Agnich L, Miller BL, Stogner JM, Mowen TJ. The "other side of the fence": a learning- and control-based investigation of the relationship between deviance and friendship quality. Deviant Behav. 2019;40:1553–1573. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2019.1596451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li T, Huang Y, Jiang M, Ma S, Ma Y. Childhood psychological abuse and relational aggression among adolescents: a moderated chain mediation model. Front Psychol. 2023;13:1082516. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1082516.7bdf3191b81a4a68970a8f0b07ba33aa [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dykstra V. Brock Univ.; St. Catharines: 2019. Lying to parents and friends: a longitudinal investigation of the relation between lying, relationship quality, and depression in late-childhood and early adolescence [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jhangiani R, Tarry H. Chapter 9: aggression. 9.2: the biological and emotional causes of aggression [Internet] Pressbooks; Ottawa: 2022. [cited 2024 Apr 20]. Available from: https://opentextbc.ca/socialpsychology/chapter/the-biological-and-emotionalcauses-of-aggression . [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fagan AA. Child maltreatment and aggressive behaviors in early adolescence: evidence of moderation by parent/child relationship quality. Child Maltreat. 2020;25:182–191. doi: 10.1177/1077559519874401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scarpa A, Haden SC, Abercromby JM. Pathways linking child physical abuse, depression, and aggressiveness across genders. J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma. 2010;19:757–776. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2010.515167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sias TN. West Virginia Univ.; Morgantown (WV): 2014. A developmental perspective: early childhood externalizing behaviors pathway to delinquency in adolescence [dissertation] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gault-Sherman M. It's a two-way street: the bidirectional relationship between parenting and delinquency. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41:121–145. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9656-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amadi AG, Nnubia UE. Relationship between home environment and child deviant behaviours in Rivers State, Nigeria. J Educ Soc Behav Sci. 2021;34:9–18. doi: 10.9734/jesbs/2021/v34i830347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naqvi I, Kamal A. Translation and adaptation of eysenck personality questionnaire [Junior] and its validation with laborer adolescents. Pak J Psychol. 2010;41:23–48. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naqvi I, Kamal A. Personality traits predicting the delinquency among laborer adolescents. FWU J Soc Sci. 2013;7:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu Z, Liu G, Chen X, Zhang W. Effects of childhood abuse experiences on peer victimization in adolescence: the mediating role of self-control, aggression, and depression. Curr Psychol. 2024;43:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12144-024-05948-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwok SYCL, Gu M, Kwok K. Childhood emotional abuse and adolescent flourishing: a moderated mediation model of self-compassion and curiosity. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;129:105629. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cristofanelli S, Testa S, Centonze E, Baccini G, Toniolo F, Vavalle V, et al. Exploring emotion dysregulation in adolescence and its association with social immaturity, self-representation, and thought process problems. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1320520. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1320520.d8439bd5418b4eda95364b8fb0914c54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishfaq N, Kamal A. Translation and validation of emotional maturity scale on juvenile delinquents of Pakistan. Psycho Lingua. 2018;48:140–148. doi: 10.1037/e592422010-029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu M. Predicting effects of personality traits, self-esteem, language class risk-taking and sociability on Chinese university EFL learners' performance in English. J Second Lang Teach Res. 2012;1:30–57. doi: 10.5420/jsltr.01.01.3318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zafar I. Parental child abuse [Internet] The Nation; Lahore: 2013. [cited 2024 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.nation.com.pk/E-Paper/Islamabad/2013-10-07/page-6/detail-3 . [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nesheen F, Alam S. Emotional abuse: agony for adolescents. Int J Indian Psychol. 2015;2:5–11. doi: 10.25215/0203.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan S. Comparison between the personality dimensions of delinquents and non-delinquents of Khyber Pukhtunkhwa (KPK), Pakistan. Open J Soc Sci. 2014;2:135–138. doi: 10.4236/jss.2014.25027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monteiro I, Ramião E, Figueiredo P, Barroso R. The role of temperament in mediating the association between adolescence dating violence and early traumatic experiences. Youth. 2022;2:285–294. doi: 10.3390/youth2030021.3898b19cb7db4962babd5950db3b1c45 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.You S, Lim SA. Development pathways from abusive parenting to delinquency: the mediating role of depression and aggression. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;46:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weaver CM, Shaw DS, Crossan JL, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. Parent-child conflict and early childhood adjustment in two-parent low-income families: parallel developmental processes. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2015;46:94–107. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0455-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saladino V, Mosca O, Lauriola M, Hoelzlhammer L, Cabras C, Verrastro V. Is family structure associated with deviance propensity during adolescence? The role of family climate and anger dysregulation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9257. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steketee M, Aussems C, Marshall IH. Exploring the impact of child maltreatment and interparental violence on violent delinquency in an international sample. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36:NP7319–NP7349. doi: 10.1177/0886260518823291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bunch JM, Iratzoqui A, Watts SJ. Child abuse, self-control, and delinquency: a general strain perspective. J Crim Justice. 2018;56:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2017.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]