Significance

Cone cyclic guanosine- 3′,5′-monophosphate (cGMP)-phosphodiesterase (PDE6C) is the essential signaling molecule for daytime vision. Unlike its rod counterpart, PDE6C remained enigmatic structurally and biochemically. We present cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures of human cone PDE6C in various liganded states that provide a platform for understanding unique features and dynamics of the cone enzyme contributing to the distinct physiology of cone photoreceptors. Further, this study sets a framework for elucidation of the mechanisms of the retinal diseases caused by mutations in the PDE6C gene.

Keywords: phosphodiesterase 6, photoreceptor, phototransduction, cryo-EM

Abstract

Cone cGMP-phosphodiesterase (PDE6) is the key effector enzyme for daylight vision, and its properties are critical for shaping distinct physiology of cone photoreceptors. We determined the structures of human cone PDE6C in various liganded states by single-particle cryo-EM that reveal essential functional dynamics and adaptations of the enzyme. Our analysis exposed the dynamic nature of PDE6C association with its regulatory γ-subunit (Pγ) which allows openings of the catalytic pocket in the absence of phototransduction signaling, thereby controlling photoreceptor noise and sensitivity. We demonstrate evolutionarily recent adaptations of PDE6C stemming from residue substitutions in the Pγ subunit and the noncatalytic cGMP binding site and influencing the Pγ dynamics in holoPDE6C. Thus, our structural analysis sheds light on the previously unrecognized molecular evolution of the effector enzyme in cones that advances adaptation for photopic vision.

Rods and cones utilize a similar G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR)-signaling phototransduction pathway with cGMP as the second messenger. In rods and cones, the key pathway molecules, GPCR (visual pigment), G-protein (transducin), and effector (phosphodiesterase-6), are represented by highly homologous isoforms (1, 2). While cones are the primary active photoreceptors mediating daytime color vision, biochemical and structural studies of phototransduction have been focused largely on rods that mediate responses to dim light. The phototransduction components are highly concentrated in a specialized outer segment compartment of photoreceptor cells. The relative abundance and ease of isolation of phototransduction proteins from native rod-rich mammalian retinas have facilitated solution of the pioneering crystal structures of rod transducin-α (Gαt) and rhodopsin, and more recently, the cryo-EM structure of rod holoPDE6 (3–5). The paucity of cones in mammalian retinas and the lack of an efficient system for expression of the functional full-length cone PDE6C have hindered understanding the structure and functional dynamics of this enzyme isoform.

There are notable differences between the rod and cone effector enzymes that apparently contribute to the critical differences in rod and cone physiology (6). Rod holoPDE6 is a catalytic heterodimer composed of PDE6A (PDE6α) and PDE6B (PDE6β) subunits with each catalytic subunit bound to a copy of rod-specific inhibitory subunit (Pγr) (7). In contrast, cone holoPDE6 is a catalytic homodimer of PDE6C (PDE6α′) subunits bound to cone-specific Pγc inhibitory subunits. Each catalytic PDE6 subunit contains tandem N-terminal regulatory GAF domains (named for cyclic GMP, Adenylyl cyclase, FhlA), GAF-A and GAF-B, and a conserved C-terminal catalytic domain. Similar domain organization is shared by several PDE families, including PDE2 and PDE5 (8). Notably, the GAF-A domains in PDE5 and PDE6 harbor noncatalytic cGMP-binding sites (8, 9). In PDE5, noncatalytic cGMP-binding leads to direct allosteric activation of cGMP hydrolysis. In rod PDE6, the GAF-A bound cGMP does not alter the enzyme catalytic properties, but it appears to increase the affinity of Pγ or drug binding at the catalytic site (10). Reciprocally, Pγ-binding enhances the affinity of noncatalytic cGMP binding in rod PDE6 (11, 12). The structure of rod PDE6 has revealed the structural routes for allosteric communication between the GAF-A domains and the catalytic domains (5). However, the physiological significance, if any, of the allosteric regulation of rod PDE6 by noncatalytic cGMP remains unknown. This is because rod PDE6 binds noncatalytic cGMP very tightly, and it is unclear if cGMP ever dissociates from its GAF-A sites in vivo (13). In fact, all structures of rod PDE6 contain cGMP bound to the GAF-A domain (5, 14). In contrast, the affinity of the PDE6C GAF-A for cGMP is significantly lower, and the apo-GAF-A/GAF-B construct of PDE6C has been structurally characterized (15–17). Therefore, cGMP occupancy of the GAF-A domains in PDE6C may change under physiological conditions, thereby influencing responses of cone photoreceptors. Accordingly, the allosteric routes and mechanisms structurally described for rod PDE6 (5, 16), may in fact be more physiologically relevant for cones.

Recently, we have established the heterologous expression of PDE6C in insect Sf9 cells, allowing purification and characterization of the enzyme (18). Here, we utilized this expression system to determine high-resolution structures of cone PDE6 by single-particle cryo-EM. We solved the structures of the (PDE6C)2Pγc2 and (PDE6C)2Pγr2 complexes and examined the conformational heterogeneity and dynamics of Pγ binding essential to the enzyme function. Furthermore, we analyzed the structure of PDE6C with Pγ removed by limited tryptic proteolysis, which revealed dramatic rearrangement of the PDE6C catalytic dimers. This finding suggests the key role of Pγ in constraining the inherent flexibility of the PDE6 catalytic dimers, which may underlie a chaperone-like effect of Pγ in the clinically important process of PDE6 maturation. Overall, our structures highlight molecular differences between the cone and rod PDE6 isoforms that are critical to the physiology of cone photoreceptors. We found that these differences were accentuated by recent molecular evolution of PDE6C.

Results

Structures of the PDE6C/5′-GMP Complexes with Pγr and Pγc.

We demonstrated earlier that coexpression of PDE6C with a specialized cochaperone aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-interacting protein-like 1 (AIPL1) and Pγ in insect cells leads to expression of holoPDE6C fully equivalent to native PDE6 from mouse retina (18). We used both Pγc and Pγr in our studies to evaluate potential contributions of the Pγ isoforms to differences in properties of the cone and rod enzymes. Analysis of the purified samples by mass photometry (MP) indicated a monodisperse species with predicted molecular weight for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 or (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Given the large thermodynamic stabilization of the PDE6C GAF-A domain through cGMP-binding (19), we preincubated the samples of purified holoPDE6C with cGMP prior to grid preparation. cGMP was added at the concentration that would not be significantly reduced due to basal hydrolysis by the enzyme.

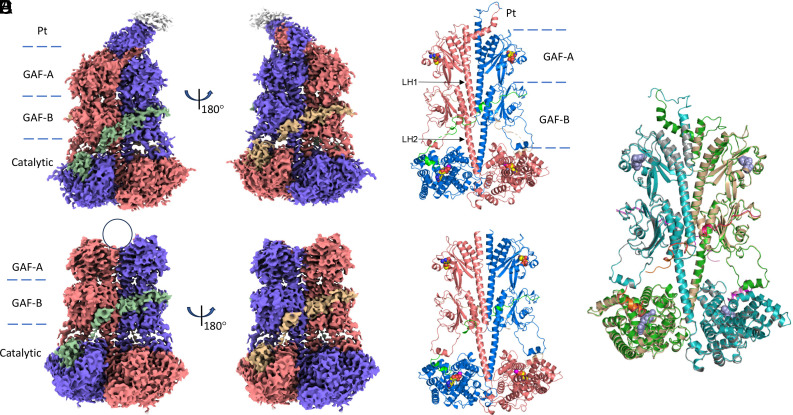

The cryo-EM dataset collected for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex was larger than that for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 complex, yielding a map with more features. Accordingly, we describe the reconstruction with Pγr first. The consensus map based on the class 1 particles was refined to an overall gold-standard FSC (GSFSC) resolution of 3.1 Å, and it was used for the model building (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Table S1). In addition to well-resolved GAF-A, GAF-B, and catalytic domains of PDE6C, this map contained defined density for the N-terminal “pony-tail” motif (Pt) as well as densities for the Pγr C-terminus blocking the PDE6C catalytic site and the polycationic/Gly-rich Pγr region bound to the GAF-B domains (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The structure of holoPDE6C closely resembles the structure of rod PDE6 (PDB 6MZB, RMSD 1.3 Å) with few notable differences (5, 14). Similarly to rod PDE6AB, catalytic PDE6C subunits are arranged in a homodimer with a pseudo-twofold symmetry (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, even though the PDE6C Pt motif is formed by two identical subunits, it is folded asymmetrically as in PDE6AB (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) (5). Symmetrical folding of the Pt motif in PDE6C is prevented by a clash between the chains (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). According to the local resolution estimation map, the Pt motif is the most flexible, whereas the GAF-B and catalytic domains are most structured (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). Nonetheless, the R29W mutation in the Pt motif is found in patients with achromatopsia (20–22), suggesting a functional role for this dynamic structural element. The R29W substitution causes steric clash with the GAF-A domain of the partner subunit (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Fig. 1.

Cryo-EM structures of the complexes of PDE6C with Pγr and Pγc in the presence of cGMP. (A) The final cryo-EM map for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex. The densities corresponding to the PDE6C subunits are colored in salmon and blue, whereas the densities for the Pγr subunits are colored in green and wheat. Pt–pony-tail motif. (B) The structure of the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex modeled into cryo-EM map is shown in cartoon. Dashed lines delimit Pt-motif, the GAF-A, GAF-B, and catalytic domains (PDB 9CXH). The linker helices connecting GAF-A with the GAF-B domains (LH1) and GAF-B with the catalytic domains (LH2) are indicated by arrows. cGMP bound to the GAF-A domains and 5′-GMP bound to the catalytic pockets are shown as spheres colored by element. Zn2+ and Mg2+ are shown as gray and magenta spheres, respectively. (C and D) The final cryo-EM map (C) for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 complex and the structure modeled into cryo-EM map shown in cartoon (D) (PDB 9CXG). The color scheme as in (A) and (B). (E) Superimposition of the structures of the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 (9CXH) and (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 (9CXG) complexes. PDE6C chains are colored green and cyan (9CXH) and wheat and gray (9CXG). Pγr chains are colored orange and pink, Pγc chains are colored magenta and hot pink. cCMP and 5′-GMP are shown as blue spheres.

The map reconstructed for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 complex was principally equivalent to that for the complex with Pγr (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Initial refinements with no symmetry imposed (C1) revealed very little or no density for the Pt motif or other asymmetrical features, and the final refinement was conducted with the C2 symmetry averaging yielding a map at 3.0 Å GSFSC resolution (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Figs. S4B and S6 and Table S1). The density for the catalytic domains of PDE6C in complex with Pγc was slightly noisier compared to that in complex with Pγr possibly reflecting their higher mobility. The local refinement map was used to validate the modeling of the catalytic domains (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). The modeled structure of the (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 complex superimposes closely with that of the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex (RMSD 0.6 Å) (Fig. 1E). The better density for the PDE6C N terminus allowed us to model more N-terminal residues of PDE6C in the structure of the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex (starting with residues 18 in chain A and 33 in chain B) compared to the complex with Pγc (starting with residues 55 in chain A and 53 in chain B). With PDE6C residues 2 to 830 present in the expressed protein, the C termini were modeled equivalently in both structures terminating at residues 825 in chain A and 823 in chain B. Due to lack of density, the N termini of Pγ in both structures (Pγc-1-20, Pγr-1-24) could not be modeled. Additionally, the map for (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 has poor density for residues Pγc-46-48 and Pγc-57-59, which correspond to residues well-resolved in (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2.

Among common features between cone and rod PDE6 is a potential allosteric signal transduction route from the cGMP-bound GAF-A to the catalytic domain via GAF-B. The allosteric path first described for rod PDE6 is well preserved in PDE6C (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B) (5). In this path, the GAF-A β1-β2 loop makes contacts with the β4 strand and the β6-β5 loop of the GAF-B domain, whereas the GAF-B β1-β2 loop interacts extensively with the catalytic domain. Underscoring the significance of the allosteric communication for PDE6C stability and function, several residues directly involved in the interdomain contacts are mutated in achromatopsia (16, 22). These residues include R102 and R104 in the GAF-A β1-β2 loop and L298 in the GAF-B β1-β2 loop (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) (20, 22–24). Another route for potential allosteric communication between the GAF-B domains and the catalytic domain is via the bound Pγ subunits (5, 16). Interestingly, PDE6C H262 makes a hydrogen bond with Y323 and also interacts with the Gly-rich region of Pγ (Pγr-54-60) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The Y323N mutation is associated with achromatopsia (20–22), whereas mutation of a rod PDE6B counterpart of H262, H258N, is linked to the Rambusch autosomal dominant congenital stationary night blindness (22, 25, 26). Thus, the structure of PDE6C sets a framework for elucidation of the mechanisms of the retinal diseases caused by mutations in the PDE6C gene.

Deficient Interaction of the Pγ Subunit with the GAF-A of PDE6C.

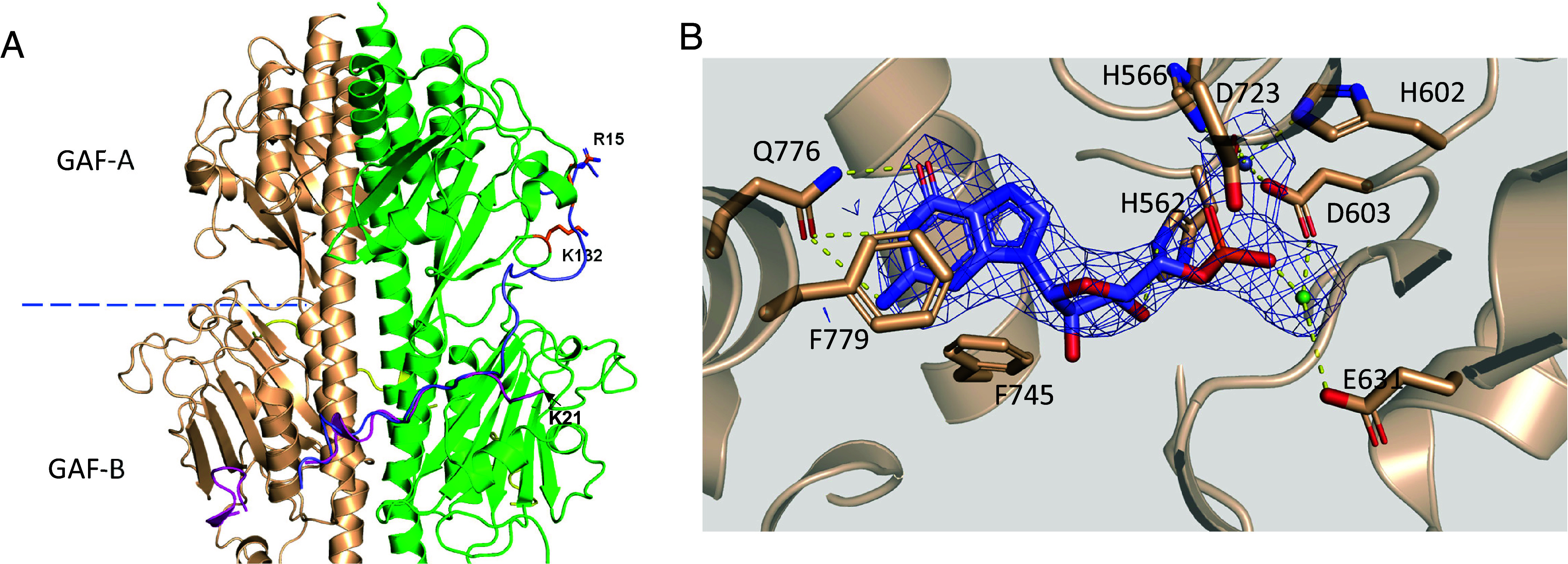

Despite similarities in the overall fold and relative domain orientation of cone and rod PDE6 catalytic subunits, minor yet potentially functionally relevant differences in the topology of the catalytic dimers exist (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 and Supporting Text). A key distinct feature of holoPDE6C is the weakened or absent interaction between GAF-A and the N-terminal region of Pγ (Pγr-11-24, Pγc-7-20) (Fig. 2A). In the structure of rod PDE6, Pγr makes extensive contacts with the GAF-A domains in close proximity to the cGMP-binding site (5). In the structures of PDE6C with Pγr or Pγc, the densities for the N-terminal residues of Pγ are missing and the first modeled residue (PγrK25, PγcK21) points away from the GAF-B and GAF-A domains (Fig. 2A). Apparently, the binding of Pγ to the PDE6C GAF-A domain, if any, is significantly more dynamic compared to that in rod PDE6. The interaction deficit might be due to a steric clash between the side chain of K132 and the backbone of Pγr18GGP20(Pγc14GGP16). In addition, residue PγrR15 essential for Pγr binding the GAF-A domains of PDE6AB (5), is not conserved in Pγc (Fig. 2A). Although the GAF-A β1-β2 loop in PDE6C comes into close proximity with the Pγ backbone at Pγr-F30/ Pγc-F26, it does not make a contact with Pγ.

Fig. 2.

(A) Deficient interaction of the Pγ subunit with the GAF-A of PDE6C. The GAF-A/GAF-B domains and the Pγ subunits (magenta and yellow) are from the structure of the (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 complex (PDB 9CXG). The first modeled residue of Pγc K21 points away from the GAF-B and GAF-A domains. Pγr assumes similar conformation in the structure of the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex (PDB 9CXH). Pγr from the structure of rod PDE6 (blue) is superimposed from PDB 6MZB. Residue PγrR15 (sticks) essential for Pγr binding the GAF-A domains of PDE6AB, is not conserved in Pγc. Pγ would clash with PDE6C K132 and not be able to interact with the PDE6C GAF-A domain as it does with the GAF-A domain of rod PDE6. (B) Key contacts of 5′-GMP in the catalytic pocket (PDB 9CXH). The guanine ring makes hydrogen bonds with the side chain of conserved Q776, which serves as a key selectivity determinant. The two divalent ions in the active site critical for cGMP hydrolysis, Zn2+ and Mg2+, are coordinated by conserved H and D residues. The electron density for ligand is shown from a 2.8 Å map after homogeneous refinement with C2 symmetry (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

The Catalytic Pockets in HoloPDE6C Are Accessible to cGMP.

Surprisingly, despite the occlusion of the catalytic opening by the C-terminus of Pγ, the catalytic pockets in both (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 and (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 complexes contained electron density for ligand. Compared with the substrate cGMP, the reaction product 5′-GMP provided a slightly better fit for the density (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S10). This and the fact that the enzyme is catalytically active led us to assign the ligand as 5′-GMP. The positioning and contacts of 5′-GMP are very similar to those in the complex of PDE9 with 5′-GMP (PDB 3DYS) (27). The guanine ring adopts an anti-conformation and is buttressed by hydrophobic side chains of F779 and I724 on one side and V741 and F745 on the opposite side (Fig. 2B). The guanine ring makes hydrogen bonds with the side chain of conserved Q776, which serves as a key selectivity determinant in cGMP-specific PDEs (27). The two divalent ions in the active site critical for cGMP hydrolysis, Zn2+ and Mg2+, are coordinated by conserved H and D residues (Fig. 2B).

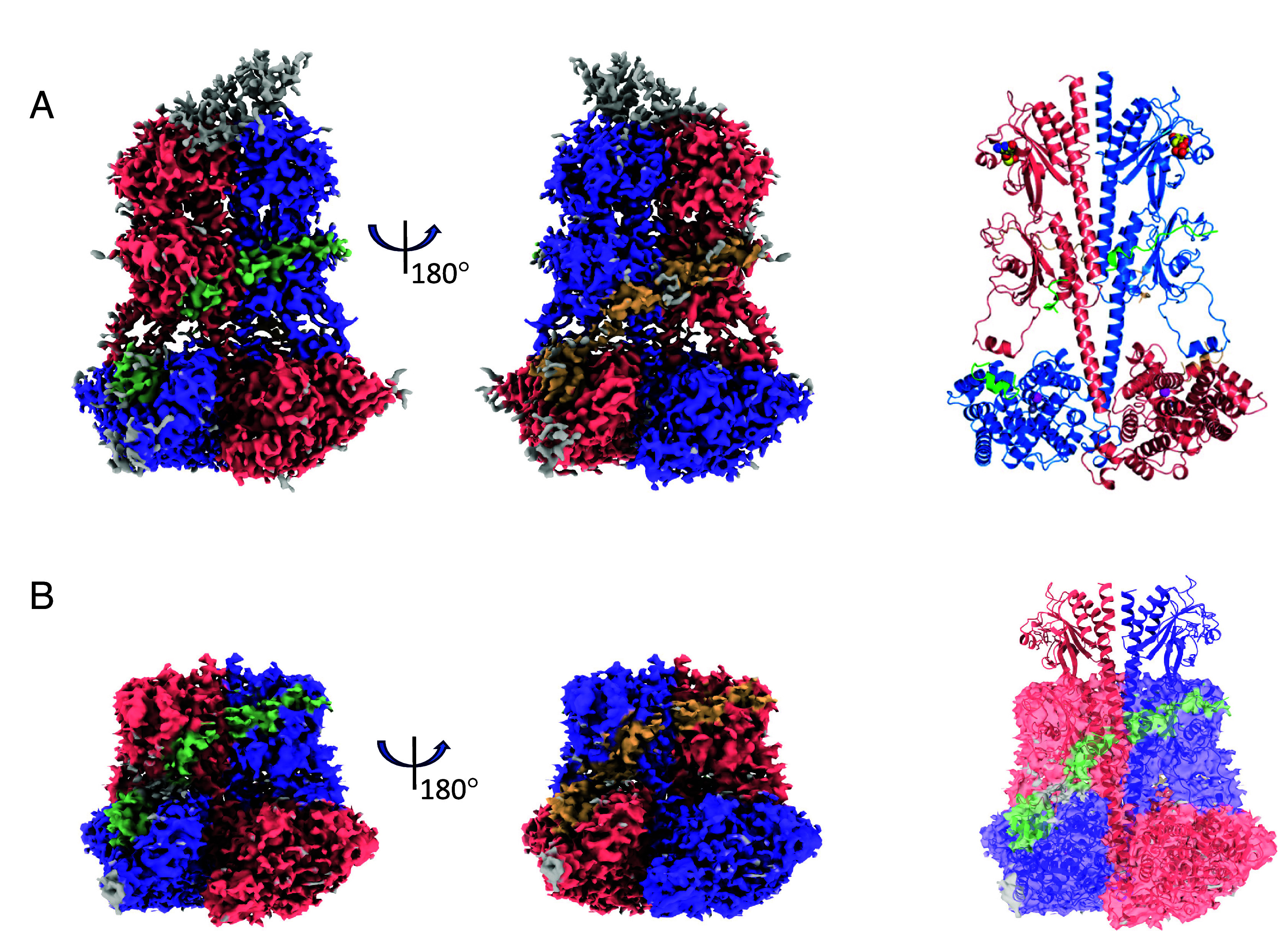

Disorganization of the PDE6C GAF-A Domains in the Absence of Noncatalytic cGMP.

To determine the structure of apoPDE6C with unliganded catalytic sites and/or GAF-A domains, we analyzed the sample of (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex in the absence of added cGMP. Two maps of the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex were reconstructed based on the major particle subsets (Fig. 3 A and B and SI Appendix, Figs. S11 and S12). The first map (class 1 particles) with the overall GSFSC resolution of 3.0 Å allowed modeling of all three structural domains: GAF-A, GAF-B, and the catalytic domain. This holoPDE6C structure closely resembles the structure of PDE6C with 5′-GMP in the catalytic pocket (RMSD 0.25 Å) (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Table S1). The second map had resolution (3.1 Å) similar to that of the first map, yet the density for the GAF-A (230 N-terminal residues) was strikingly lacking (Fig. 3B). Still, this partial map and the partial structure model aligned well with the full map and the structure (RMSD 1.5 Å). Class 2 particles missing the density for the GAF-A domain comprised ~17% of structured PDE6C molecules in the sample. Such “GAF-A-less” particles were not observed for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex with the addition of exogenous cGMP. We surmised that this reconstruction was based on PDE6C particles with no cGMP bound to the GAF-A domains. Our analysis revealed very few asymmetric particles apparently containing density for only one GAF-A domain (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A). Thus, disorder of a single empty-pocket GAF-A domain either leads to destabilization of a partner cGMP-occupied GAF-A domain or facilitates dissociation of cGMP from the second GAF-A site. Both PDE6C maps, with and without the GAF-A bound cGMP, showed densities for the polycationic/Gly-rich region and the C termini of Pγr and no ligand density in the catalytic pocket (Fig. 3 A and B).

Fig. 3.

Disorganization of the PDE6C GAF-A domains in the absence of noncatalytic cGMP. (A and B) Maps and structures of the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex were obtained based on two major particle subsets. (A) The first map based on 83% of particles features all three structural domains: GAF-A, GAF-B, and the catalytic domain. Approximately 50 N-terminal residues of the Pt motif are not modeled due to poor density. cGMP bound to the GAF-A domains is shown as spheres. Zn2+ and Mg2+ in the catalytic pocket are shown as gray and magenta spheres, respectively. There is no ligand in the catalytic pocket. (B) The second map based on 17% of particles lacks the density for the GAF-A (230 N-terminal residues). The coloring scheme is as in Fig. 1.

Rearrangement and Destabilization of the PDE6C Catalytic Dimer in the Absence of the Pγ Subunit.

Extensive symmetrical interactions of each Pγ molecule with the GAF-B and catalytic domains of PDE6C point to a scaffolding role of Pγ in maintaining the overall structural design of the enzyme. To probe PDE6C structure in the absence of Pγ, we analyzed PDE6C sample in which the Pγ subunit was removed by limited tryptic proteolysis (tPDE6C) (28). The final partial map of tPDE6C at 4.1 Å GSFSC resolution was matched to the dimer of GAF-B domains (SI Appendix, Figs. S13 and S14, Table S1, and Supporting Text). Rigid body modeling of the tPDE6C structure according to an altered arrangement of α-helices of the GAF-B domains pointed to potential disruption of the dimeric interface at the GAF-A domains as well as the catalytic domains (SI Appendix, Fig. S14 B and C). To assess potential conformation(s) of tPDE6C, we conducted molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using the rigid body model as a starting conformation. These MD simulations suggested that the arrangement of α-helices of the GAF-B domains observed in tPDE6C is stabilized by packing of the GAF-B domains against the GAF-A and catalytic domains (SI Appendix, Fig. S16 and Supporting Text).

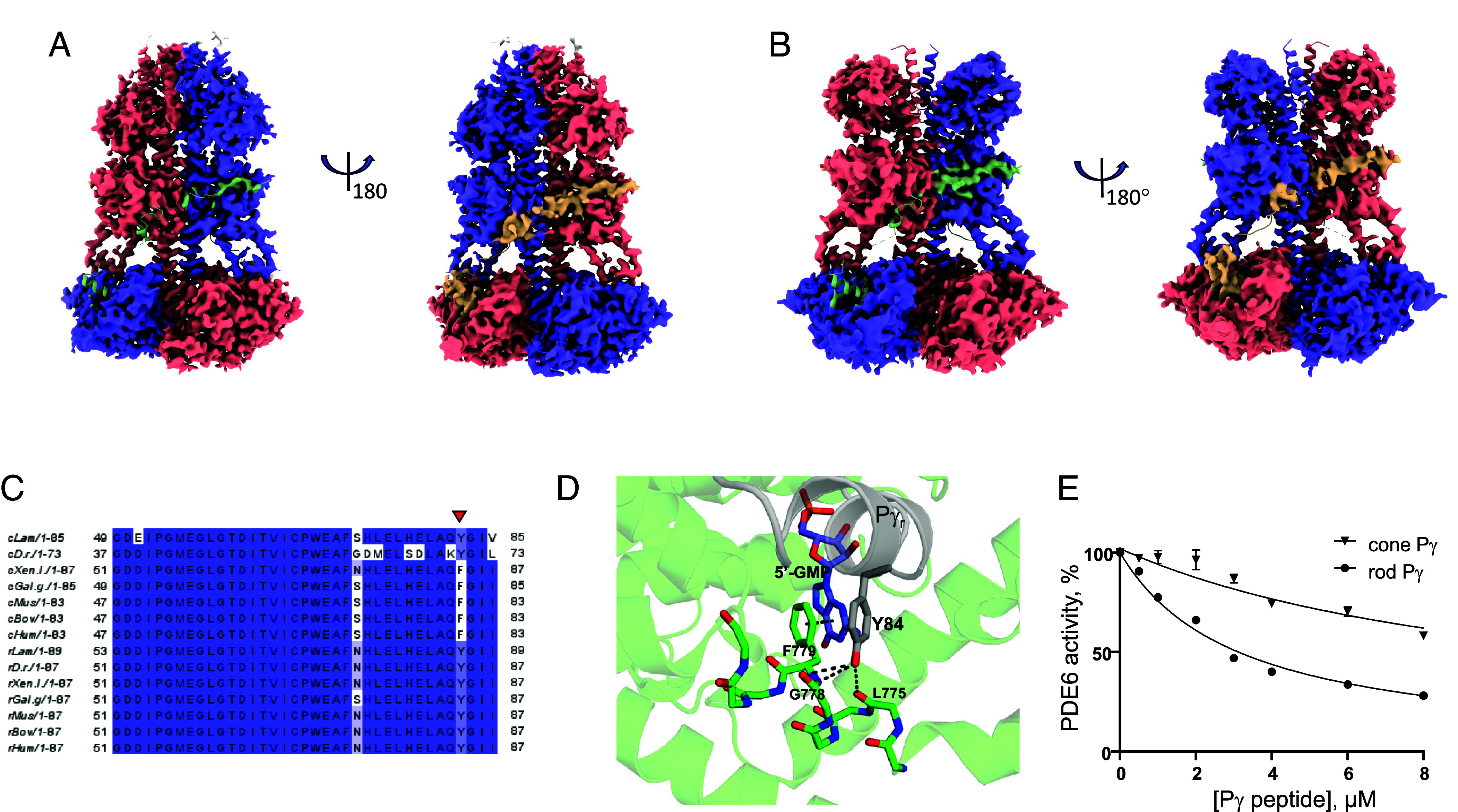

Conformational Heterogeneity and Dynamics of Pγ in the Complex with PDE6C.

To examine conformational heterogeneity and dynamics of holoPDE6C, we conducted 3D variability analysis (3DVA) implemented in CryoSparc (29). 3DVA of the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex in the presence of cGMP using full mask revealed that the key variability components (VC) are linked to changes in the Pt motif. When the Pt-motif was masked out, 3DVA exposed interdomain movements and changes in the occupancy of the Pγ-binding sites. Specifically, VA1 resolves asymmetrical bending of the GAF-A domains toward the catalytic domains with one GAF-A domain bending more thereby leading to twisting (SI Appendix, Fig. S17). VA2 shows concurrent decreases in Pγr density at both PDE6C catalytic subunits of the dimer (SI Appendix, Fig. S18). The observed changes in Pγr density and the presence of 5′-GMP in the catalytic pocket suggested transient opening of the latter due to displacement of the Pγr C-terminus or dissociation of Pγr from PDE6C. To explore the occupancy of the Pγr binding sites in more detail, we conducted 3DVA on the symmetry-expanded dataset masking a single Pγr-bound PDE6C catalytic subunit (except for the Pt motif) and focusing on VC displaying differential densities for Pγr (SI Appendix, Fig. S19). In this analysis, VC2 resolves clear changes in the density for the masked copy of Pγr from the catalytic site fully blocked by the Pγr C-terminus to the fully exposed catalytic site. Following clustering of the particles along VC2 and duplicates’ removal from the clusters with no density for the Pγr C-terminus, the fractions of PDE6C molecules with a single and both open catalytic sites were estimated at ~20% and ~1.4%, respectively (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S20A). Conspicuously, reconstruction of PDE6C with a single open catalytic site indicated that the density for the Pγr polycationic/Gly-rich region at the GAF-B domain persists (Fig. 4A). Thus, Pγr may remain bound to PDE6C even when Pγr C-terminus is detached. Remarkably, the open catalytic pocket remained occupied by 5′-GMP (SI Appendix, Fig. S21). Although the Pγ density in the map with both open catalytic sites is very poor (SI Appendix, Fig. S20A), the fact that, in contrast to tPDE6C, these molecules are structured supports the remaining interaction with Pγr at the GAF-B domains. 3DVA on the symmetry-expanded dataset for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 was conducted as for the complex with Pγr using a mask enclosing a single Pγc-bound PDE6C catalytic subunit (SI Appendix, Fig. S22A). Similarly to the 3DVA with Pγr, reduction in the density for the masked copy of Pγc was observed with VC2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S22B). Clustering of the particles along VC2 followed by duplicates’ removal from the clusters with no density for the Pγc C-terminus revealed increased fractions of molecules with a single (~28%) and both open catalytic sites (2.2%) (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Figs. S20B and S22).

Fig. 4.

Conformational heterogeneity and dynamics of Pγ in the complex with PDE6C. (A) Map for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex in the presence of cGMP with a single open catalytic site. The map reconstruction is based on the ~20% particles used in the processing of the final map and selected from the 3DVA. (B) Map for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 complex in the presence of cGMP with a single open catalytic site. The map reconstruction is based on the ~28% particles used in the processing of the final map and selected from the 3DVA. (A and B) The densities corresponding to the PDE6C subunits are colored in salmon and blue, whereas the densities for the Pγr and Pγc subunits are colored in green and wheat. The Pγ subunits are superimposed from the final models of the complexes. The sites with the Pγ C-terminus shown in the green cartoon lack corresponding density. (C) Clustal Omega multiple sequence alignment of the C termini of Pγ subunits. Cone Pγ subunits: cLam, lamprey A3RLS1; cD.r., Danio rerio NP_957079; cHum, human Q13956; cBov, bovine P22571; cMus, murine NP_076387; cGal.g, chicken AAO67734; cXen.l, Xenopus laevis AAH74358. Rod Pγ subunits: rLam, lamprey A4LAP0; rD.r., Danio rerio NP_997964; rHum, human P18545; rBov, bovine P04972; rMus, murine P09174; rGal.g, chicken NP_989776; rXen.l, Xenopus laevis AAH74367. The Y/F substitution in cone Pγ subunits (except in fish) indicated by red arrow. (D) The Y/F substitution disrupts hydrogen bonding between Y84 hydroxyl group and backbone atoms of PDE6C. Interactions between rod PγY84 and backbone atoms of PDE6C (PDB 9CXH). Similar interactions present between PγY84 and rod PDE6AB (PDB 6MZB). Distances between the hydroxyl group of Y84, and backbone oxygen of G778, backbone nitrogen of F779 and backbone oxygen of L775 are 3.3 Å each. F779 side chain is involved in π–π stacking (4 Å) with the guanosine group of 5′-GMP. For clarity, only the side chain of F779 is shown. The backbone of PDE6C residues 774 to 782 is shown as sticks, and the rest of the PDE6C molecule is shown as cartoon with transparency set to 0.7. (E) Inhibition of PDE6 by the C-terminal peptides of rod and cone Pγ. Activity of tPDE6 from mouse retina was measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of Pγr -63-87 or Pγc-59-83. Representative experiment is shown. From three similar experiments (Mean ± SD), Ki = 2.5 ± 0.4 μM for Pγr-63-87, maximal inhibition 100%; Ki = 8.2 ± 2.4 μM for Pγc-59-83, maximal inhibition 95%. t test P = 0.015.

Reduced Pγ-Occupancy of the PDE6C Catalytic Sites in the Absence of Noncatalytic cGMP.

To determine whether noncatalytic cGMP-binding in PDE6C alters the occupancy of the Pγr binding sites, we conducted 3DVA and clustering analysis of the symmetry-expanded dataset for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex in the absence of cGMP. 3DVA of class 1 particles indicated that ~19% of them had only one Pγr blocking the catalytic site, whereas both catalytic sites were open in ~1% particles (SI Appendix, Fig. S23A). 3DVA of class 2 particles showed a significant increase in fraction of PDE6C molecules with one (~43%) or both (~8%) catalytic sites open (SI Appendix, Fig. S23B).

Weaker Interaction of the PDE6 Catalytic Domain with the C-Terminus of Cone Pγ.

3DVA of the cryo-EM data for the PDE6C complexes with Pγr and Pγc indicated that the C-terminus of Pγc may bind to the catalytic domain less tightly. The fraction of PDE6C molecules with one open catalytic site increased when Pγr was substituted by Pγc. PDE6C contact residues of Pγc and Pγr are different at one position, PγcF80/PγrY84 (Fig. 4C). The Y/F substitution disrupts hydrogen bonding between Y84 hydroxyl group and backbone atoms of PDE6C (Fig. 4D). To probe the interactions of PDE6 with the C termini of Pγr and Pγc, we examined the ability of synthetic C-terminal Pγ peptides to inhibit trypsin-activated PDE6 from mouse retina extracts (30, 31). In agreement with earlier analysis, synthetic peptide corresponding to 25 C-terminal residues of Pγr, Pγr-63-87, inhibited tPDE6 with the Ki value of 2.5 ± 0.4 µM (Fig. 4E) (31). However, equivalent Pγc peptide, Pγc-59-83, was significantly less potent (Ki 8.2 ± 2.4 µM) (Fig. 4E). Thus, our data point to a weaker interaction of the PDE6 catalytic domain with the C-terminus of Pγc compared to that of Pγr. Furthermore, the full-length Pγc was also significantly less potent (Ki 75.5 ± 12.8 pM) than Pγr (Ki 29.4 ± 6.3 pM) in inhibiting tPDE6 isolated from bovine rod outer segment membranes (SI Appendix, Fig. S24). The weaker interaction of the Pγc C-terminus with the catalytic domain is in good agreement with biochemical data showing more efficient activation of cone PDE6 by Gαt in solution compared to that for rod PDE6 (15).

Structural Basis for Distinct cGMP Binding Affinities of the Cone and Rod PDE6 GAF-A Domains.

cGMP makes similar electrostatic and hydrophobic contacts with the GAF-A domains in PDE6C and PDE6AB (SI Appendix, Fig. S25 A and B) (5, 19). Structure comparison suggests that distinct noncatalytic cGMP binding properties of the cone and rod enzymes might be underlined by a) the deficit in interaction between Pγ and the PDE6C GAF-A domain, and/or b) the PDE6A-F113/PDE6C-L115 substitution in the GAF-A β2 sheet (SI Appendix, Fig. S25C). The bulky side chain of PDE6A-F113 is in close proximity (~4 Å) to Pγr, and it points into the binding pocket making π–π stacking interaction with the guanine ring (PDB 6MZB) (Fig. 5A) (5). Furthermore, F113 appears to contribute to the narrower opening of the GAF-A cGMP binding pocket in PDE6A compared to that in PDE6C (SI Appendix, Fig. S26). To probe the role of PDE6C-L115 we introduced the L/F substitution in the chicken PDE6C GAF-A/GAF-B construct (aa 42-458) amenable to heterologous expression in Escherichia coli (16). Since cGMP-binding to PDE6 GAF-A domains is very tight, we used a kinetic cold chase type of experiment rather than an equilibrium binding assay to assess the effect of the mutation. The rate of dissociation of [3H]cGMP from PDE6C-42-458 (koff 0.015 ± 0.001 min−1) was markedly slowed by the L/F mutation (koff 0.002 ± 0.0003 min−1) (Fig. 5B). The deficit in interaction between Pγ and the PDE6C GAF-A domain raised a question of whether or not Pγ affects noncatalytic cGMP binding in PDE6C. The dissociation of [3H]cGMP from PDE6C-42-458 was modestly inhibited in the presence of 50 µM Pγc (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

cGMP-binding by PDE6C GAF-A domain. (A) In PDE6C proteins of higher vertebrates, L (human PDE6C-L115), is localized at the opening of the GAF-A cGMP-binding pocket (PDB 9CXG). Rod PDE6 isoforms contain F at this position. The bulky side chain of PDE6A-F113 points into the binding pocket making π–π stacking interaction with the guanine ring. The side chain of F113 is superimposed from PDB 6MZB. (B) The rate of dissociation of cGMP bound to chicken PDE6C-42-458 was measured following the protein preincubation with [3H]cGMP and cold chase with an excess of unlabeled cGMP by the filter binding assay. For the WT+Pγc samples, 50 µM Pγc was added prior to the addition of unlabeled cGMP. The koff values from the exponential decay fits to the data are 0.015 ± 0.001 min−1 for PDE6C-42-458 and 0.002 ± 0.0003 min−1 for the L/F mutant, 0.012 ± 0.002 min−1 for PDE6C-42-458 plus 50 µM Pγc (Mean ± SD, n = 3). t test: WT vs. L/F P < 0.0001; WT vs. WT+ Pγc P = 0.017. (C) The steady state binding curves as determined using BLI for MBP-Pγc binding to PDE6C-42-458 in the presence or absence of cGMP. The KD values (Mean ± SD, n = 3): KD 36.1 ± 8.3 µM; +cGMP, KD 10.0 ± 1.9 µM. t test P = 0.007.

Noncatalytic cGMP Enhances Binding of Pγ to the GAF-B Domains of PDE6C.

Local resolution estimation map (SI Appendix, Fig. S12) and 3DVA for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex lacking density for the GAF-A domain indicate increased dynamics of Pγ, suggesting that noncatalytic cGMP increases the binding affinity of PDE6C for Pγ. To directly examine the effect of cGMP on the Pγc interaction with PDE6C-42-458, the latter was coupled to a streptavidin biosensor and the binding was assessed using Biolayer Interferometry assay (BLI) in the presence or absence of cGMP. To enhance the BLI response signal we utilized the MBP-fusion protein of Pγc. These experiments reveal significantly tighter interaction of Pγc with PDE6C-42-458 in the presence of cGMP (Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S27). Hence, the BLI data directly demonstrate that cGMP binding to the GAF-A domain allosterically increases the binding affinity of PDE6C for Pγc.

Discussion

The cryo-EM structure of human cone PDE6 revealed the molecular features and conformational heterogeneity that suggest protein dynamics essential to distinct physiology of cones and rods. Differences in biochemical properties of the phototransduction effector enzymes, rod and cone PDE6, are among the principal mechanisms that have been proposed to account for the faster signaling and lower sensitivity of cones (6). PDE6 activity in the dark or in background light is a critical parameter that controls cGMP turnover rate and the properties of photoresponse (32, 33). Exchange of cone for rod PDE6 catalytic subunits in mouse rod photoreceptors led to a higher basal PDE6 activity and faster phototransduction deactivation, which are consistent with faster and less sensitive cone photoresponses (6). Faster phototransduction deactivation also leads to a reduced rise of steady PDE6C activity in background light, which may allow cones to avoid saturation (6).

One of the main structural differences between rod and cone PDE6 holoenzymes is the observed deficit of interaction between the N-terminal region of Pγr or Pγc and the GAF-A domain of PDE6C. The N-terminal residues making contacts with the GAF-A domains of PDE6AB are conserved in Pγr but not Pγc subunits. As a result, the overall affinity of Pγr for PDE6AB is greater than the affinity of Pγc for PDE6C. The weakened or absent interaction of the PDE6C GAF-A domain with Pγc may lead to infrequent events of Pγc dissociation from PDE6C entirely. This does not occur in rod PDE6, as its spontaneous activity is independent of exogenous Pγ (32). The presence of minor populations of particles with the 2D classes similar to those for tPDE6C suggests that, under our experimental conditions, both copies of Pγ dissociate completely in a minor fraction of PDE6C molecules (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). This leads to a dramatic rearrangement and destabilization of the PDE6C catalytic dimer that has been exposed by the cryo-EM reconstruction of tPDE6C. Such rearrangement is consistent with earlier negative-stain EM imaging of rod tPDE6, although the nature of the conformational change cannot be ascertained from the previous analysis (34). Partial unraveling of the dimerization interface suggests that tPDE6 may conformationally resemble an intermediate in PDE6 maturation (18). Therefore, the scaffolding and stabilizing effect of Pγ is likely underlying its role as cochaperone in maturation of PDE6 (35).

Another consequence of the deficient GAF-A/Pγ interaction is a more dynamic interaction of the Pγ polycationic/Gly-rich region with the PDE6C GAF-B domains, which in turn appears to influence the binding of the Pγ C-terminus at the catalytic site. Our 3DVA uncovered PDE6C molecules with the bound Pγ polycationic/Gly-rich region but the Pγ C-terminus is detached, and the catalytic site is open. This conformational state of PDE6 is likely to be a primary source for the spontaneous PDE6 activity (32). The fraction of PDE6C molecules with an open catalytic site is increased in two holoPDE6C preparations: a) when Pγr is substituted by Pγc, and b) when cGMP dissociates from the PDE6C GAF-A domains. The cryo-EM analysis of holoPDE6C in the absence of added cGMP showed the presence of a sizable fraction of PDE6C molecules with a greatly increased mobility of the GAF-A domains due to loss of bound cGMP. This PDE6C fraction contained the highest proportion of PDE6 molecules with one or both catalytic sites open. Earlier cryo-EM studies have not revealed the existence of rod PDE6 with unliganded GAF-A domains (5, 14, 36). Thus, our structural analysis agrees with the biochemical evidence of a lower affinity of cGMP for the PDEC GAF-A domain compared to the PDE6AB GAF-A domains (13, 15, 16). It suggests that on cGMP dissociation, the destabilization signal from the GAF-A domains is relayed allosterically to Pγ binding sites via LH1, LH2, and the GAF-A/GAF-B β1β2 loops. Conversely, as our BLI analysis shows, cGMP-binding to the GAF-A domain increases Pγ affinity for PDE6C.

The dynamical nature of the Pγ C-terminus interaction explains the presence of 5′-GMP in the catalytic pocket of PDE6C in the presence of exogenous cGMP. Recent structure of rod PDE6 in the presence of constitutively active mutant of Gαt and cGMP shows ligand in the catalytic site, which was modeled as the substrate (14). From the reduced density for Pγ, the authors concluded that the ligand competes with Pγ for binding to PDE6AB (14). Possibly, the observed changes in the Pγ density were due to the varying ratios of rod PDE6 and Gαt. Our 3DVA suggests that 5′-GMP does not compete with Pγ for binding to the PDE6C catalytic site, and the structures of both rod and cone PDE6 offer no structural rationale for such competition. The catalytic pocket of PDE6C is structurally very similar to the catalytic sites of cGMP-specific PDE5 and PDE9 (27, 37). The residues involved in cGMP binding and hydrolysis are conserved in all three enzymes. Detailed structural and kinetic analysis of the catalytic mechanism of PDE9 demonstrated that cGMP binding, dissociation, and hydrolysis are fast in relation to product dissociation (27). 5′-GMP modeled into the density superimposes well with 5′-GMP in the structure of the PDE9 enzyme•product (EP) complex (PDB 3DYS) (27). The key outstanding question is the basis for exceptional catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) of PDE6, which exceeds that for PDE5 and PDE9 by orders of magnitude and approaches efficiency of diffusion limited enzymes. It is yet unknown if the catalytic efficiency of PDE6 is intrinsic to its catalytic domain, or if it is a function in the context of the entire catalytic dimer.

Prompted by the cryo-EM structures and the 3DVA data, we identified recently evolved features of holoPDE6C influencing the Pγ dynamics. Intriguingly, both Pγc and Pγr in lamprey and fish contain Y at the position corresponding to PγrY84 (38). The Y/F substitution arose thereafter in Pγc subunits, and F in this position is strictly conserved in Pγc from amphibians to mammals. We found that the Pγc C-terminal peptide inhibits PDE6 less potently compared to its rod counterpart. Based on our findings, we hypothesize that Pγc and Pγr evolved in two important steps. First, Pγr evolved from a duplicated ancestral cone-like Pγ gene by acquiring the N-terminal sequence for recognition of the PDE6 GAF-A domain. This adaptation enhanced the Pγr-binding affinity and decreased the basal activity of rod PDE6. Subsequently, Pγc evolved in the opposite direction by acquiring the Y/F substitution, which reduced the Pγc-binding affinity and increased the basal activity of cone PDE6. The second recently evolved feature of cone PDE6C is the F/L substitution in the GAF-A domain, which arose in lizards and is conserved in higher vertebrates. We demonstrated that the F/L substitution in the GAF-A domain of PDE6C reduces its affinity for cGMP, which in turn, allosterically controls PDE6C affinity for Pγc. The two adaptations in holoPDE6C point to a previously unrecognized molecular evolution of the effector enzyme in cones after the emergence of the rod isoforms. These evolutionary steps might have been a part of adaptation of cones to terrestrial light environments.

Methods

Cloning, Protein Expression, and Purification.

For expression in insect cells, PDE6C, AIPL1, and Pγr were cloned in the pFastBacHT A vector (Invitrogen) as described previously (18). DNA encoding Pγc with the Twin-Strep-tag was amplified from modified pET21a vector and cloned into the pFastBacHT A vector using Gibson assembly (39). For expression of the MBP-fusion protein of Pγc, Pγc was PCR-amplified and cloned into NcoI-XhoI sites of modified pET21a vector with N-terminal His6-MBP-tag and TEV protease cleavage site. A gene fragment encoding chicken ggPDE6C GAF-A/GAF-B (res. 42 to 458) with the C terminal Avi- and His6-tags was synthesized by Twist Bioscience and cloned into the pET21a vector using Gibson assembly (39). GAF-A/GAF-B L115F mutant was generated using site-directed mutagenesis.

For cryo-EM studies, EGFP-PDE6C coexpressed with AIPL1 and Pγc or Pγr was purified by immunoaffinity chromatography over EGFP-nanobody resin followed by (PDE6C)2•(Pγ)2 release with 3C protease and size exclusion chromatography as described (18). The chicken PDE6C GAF-A/GAF-B construct (42-458) and chicken PDE6C GAF-A/GAF-B L115F mutant were expressed in Rosetta (DE3) E. coli cells using 2XTY media. The proteins were purified using Ni-NTA resin (EMD Millipore) followed by ion-exchange chromatography on a HiTrap Q HP column (GE Healthcare) and by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, and 5% glycerol. The MBP-fused Pγc was expressed in Rosetta (DE3) cells. After Ni-NTA chromatography, the protein was further purified by cation exchange chromatography using SP Sepharose Fast Flow resin (GE Healthcare) and by SEC on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg column equilibrated with 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, and 5% glycerol.

CryoEM Sample Preparation, Data Collection, and Processing.

The samples of holoPDE6C with Pγc and Pγr were concentrated to 0.4 mg/mL and incubated with 5 mM cGMP for 10 min at 25 °C. The sample of tPDE6C was prepared by treating the holoPDE6C with 80 µg/mL trypsin for 10 min on ice followed by the addition of fivefold excess of soybean trypsin inhibitor and 30 µM sildenafil for 5 min at 25 °C. Finally, the sample was incubated with 5 mM cGMP for 10 min at 25 °C. For the sample of tPDE6C reconstituted with Pγc, Pγc was added at a molar ratio of ~1:2 followed by incubation at 25 °C for 10 min prior to SEC on a Superose 6 10/300 GL (GE Healthcare) as described (18).

Samples (3 µL) were applied on glow-discharged holey carbon grids (R 1.2/1.3, Quantifoil) and the grids were blotted in a Vitrobot (Thermo Fisher) (humidity 100%, 4 °C) for 3 s before plunge freezing in liquid ethane. Samples were imaged on a Titan Krios TEM (ThermoFisher Scientific) equipped with a Gatan K3 direct electron detector at a magnification of 105,000 and physical pixel sizes of 0.825 to 0.827 Å (0.4125 to 0.4135 Å superresolution mode). The movies were collected with 40 frames each with a defocus range of −1.0 to −3.0 μm and a total exposure of 60 e−/Å2. 19,888 and 6,737 movies were collected for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 and (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 complexes in the presence of cGMP, respectively. 6,598 movies were collected for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex in the absence of cGMP, and 6,932 movies were collected for tPDE6C.

The cryo-EM data processing for all reconstructions was performed using cryoSPARC V4.4.1 (29). The movies were motion-corrected using patch motion correction with binning by 2 followed by patch CTF estimation. For particle picking in all datasets, a Topaz picking model was generated using Topaz train job and 16,751 particles from 2D classes with high-resolution features as an input. The latter particles were selected after multiple rounds of 2D classification of particles picked by blob picker from the dataset for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex. For all datasets, after Topaz picking and extraction with additional binning by 2, several rounds of 2D classification were performed to select the 2D class averages with high-resolution features. Typically, ab initio models were reconstructed with the selected particles followed by 2 to 3 rounds of heterogeneous refinement and homogeneous refinement. For the final refinement steps, particles were re-extracted without binning. Nonuniform refinement was used to generate final maps if it led to an improved GSFSC resolution and/or map quality as assessed by visual inspection in Coot (40). Global CTF and/or local CTF refinement were performed as implemented in cryoSPARC.

Flow charts for cryo-EM data processing for different samples are shown in SI Appendix, Figs. S2, S6, S11, and S13. Specifically, for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex in the presence of cGMP, ab initio reconstruction and heterogeneous 3D refinement of the particles from 2D classes with high-resolution features revealed two particle populations, one dominant (83%) and one minor (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). A map reconstructed based on the dominant subset of particles featured well-resolved GAF-A, GAF-B, and catalytic domains of PDE6C (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Further 3D classification without alignment revealed three subsets of PDE6C particles at a more finite level of heterogeneity (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Since the 3D classes indicated asymmetrical features, the maps were refined without imposing twofold symmetry. The map based on class 1 particles (~26%) contained additional resolved density for the N-terminal “pony-tail” motif (Pt). The other two maps lacked the Pt density and differ in the resolution of the GAF-A domain, which was well structured for the class 2 particles (~38%) and somewhat less structured for the class 3 particles (~36%) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The consensus map based on the class 1 particles was refined to an overall GSFSC resolution of 3.1 Å.

3DVA.

The final maps refined in C1 (no symmetry imposed) were used as inputs for 3DVA and filtering resolution to 6 Å. If a final map was refined in C2, a corresponding map refined in C1 was used instead. Masks for 3DVA were from final refinement jobs or partial masks prepared using Color Zone tool in ChimeraX (41). Partial masks were generated by placing the structures of holoPDE6C into masks, coloring masks by selected residues, and splitting the masks according to colors. To assess the occupancy of the Pγ binding sites, 3DVAs were conducted on the symmetry-expanded datasets masking a single PDE6C catalytic subunit and its copy of Pγ. Typically, four VC from 3DVA output were examined by running 3D Variability Display job in a simple mode with 10 frames to identify VC that best resolves changes in the density for the masked copy of Pγ at the catalytic site. Selected VC was then used as input into 3D Variability Display job in a cluster mode with 20 clusters. The volumes reconstructed from each of the 20 clusters were inspected in UCSF Chimera. Particles from clusters with no Pγ density at the catalytic site were combined and submitted to Remove Duplicate Particles job. Accepted particles were regarded as particles with a single open catalytic site, whereas rejected particles were regarded as particles with both catalytic sites open.

Model Building and Refinement.

A homology model for human PDE6C was generated with SWISS-MODEL (42) using the cryoEM structure of rod holoPDE6 (PDB 6MZB) (43). This model was docked into the consensus EM maps for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex in the presence of cGMP using fit-in-map tool in UCSF Chimera (44). The model was subsequently refined using NAMDinator and iterative cycles in Phenix real space refine and manual modification in Coot (40, 45, 46). The resulting structure was then used as the starting models for the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex in the absence of cGMP and the (PDE6C)2•(Pγc)2 complex in the presence of cGMP, which were refined in the respective maps using NAMDinator, Phenix real space refine, and manual modification in Coot (40, 45, 46).

BLI Binding Assay.

An Octet RED96 system and streptavidin (SA)-coated biosensors (Sartorius-) were used to measure association and dissociation kinetics for MBP-Pγc binding to the C-terminally Avi-tagged in vitro biotinylated chicken PDE6C GAF-A/GAF-B (42-458). Binding studies were performed with biosensors in 0.2 mL of sample in each well stirred at 1,000 rpm in buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM TCEP, and 1 mg/mL BSA at 26 °C. PDE6C-42-458 protein was loaded onto SA sensors at a concentration of 10 µg/mL for 100 s. To probe the effect of cGMP, PDE6C-42-458 was incubated with 100 µM cGMP for 30 min before loading on the sensors. Reference sensors without loaded PDE6C-42-458 were used to correct for nonspecific binding. The affinity constant KD was calculated from fitting steady-state data to the equation for one site-specific binding using the GraphPad Prism 8 software.

PDE6 Activity Assays.

Trypsin-activated PDE6 from mouse retina was used to probe inhibition of PDE6 activity by synthetic peptides Pγr -63-87 and Pγc -59-83. Pγr -63-87 and Pγc -59-83 were custom-made by Sigma-Genosys and Abclonal, respectively, and purified by reverse-phase HPLC. Mouse retinas were homogenized by sonication (two 5-s pulses) in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4, and 1 mM βME (2 retinas per 200 µL), spun at 20,000 × g for 3 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris and treated with trypsin (100 μg/mL) for 10 min at 25 °C. Trypsin activity was terminated by the addition of 10× soybean trypsin inhibitor (SBTI, Sigma) and incubation for 5 min at 25 °C, followed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 3 min at 4 °C. The final dilution of trypsin-treated retinal lysates in the assays of PDE6 activity was 1:2,500. PDE6 from bovine rod outer segment membranes was extracted and tPDE6 was prepared as described previously (47). Bovine rod tPDE6 (10 pM final concentration) was used in the assays of PDE6 activity inhibition by the full-length Pγr and Pγc. The PDE6 activity assays were conducted in 40 µL (final volume) of 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5) buffer containing 120 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 1 mM BME, 0.1 U bacterial alkaline phosphatase, 10 μM [3H]cGMP (100,000 cpm) (PerkinElmer) in the presence or absence of Pγr -63-87, Pγc -59-83 or the full-length Pγ proteins for 15 to 20 min at 25 °C. The assay buffer for bovine rod PDE6 also contained 50 µg/mL BSA. The reaction was stopped by adding AG1-X2 cation exchange resin (0.5 mL of 20% bed volume suspension) (Bio-Rad). Samples were incubated for 6 min at 25 °C with occasional mixing and spun at 10,000 g for 3 min. 0.25 mL of the supernatant was removed for counting in a scintillation counter.

Assay of cGMP Dissociation Rate from PDE6C-42-458.

To obtain [3H]cGMP-bound PDE6C-42-458 and the L/F mutant, the proteins (0.5 µM) were incubated with 0.1 µM [3H]cGMP in a 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, and 5% glycerol for 45 min at 25 °C. Where indicated, 50 µM Pγc was added followed by additional incubation for 7 min at 25 °C. Dissociation of [3H]cGMP was initiated by addition of 200 µM of unlabeled cGMP. 100 µL aliquots from the mixture were withdrawn at different time points and filtered through presoaked 0.45 µm nitrocellulose membranes (25 mm diameter, Whatman, Cytiva). After rinsing 2 times with 1 mL of ice-cold 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, and 5% glycerol, [3H]cGMP bound to the membranes was determined in a scintillation counter.

Mass Photometry.

Mass Photometry experiments were performed on a Refeyn TwoMP (Refeyn Ltd.) (48). No.1.5, 24 mm × 50 mm microscope coverslips (Thorlabs Inc.) were cleaned by serial rinsing with Milli-Q water and HPLC-grade isopropanol (Sigma Aldrich), on which a CultureWell gasket (Grace Bio-labs) was then placed. All measurements were performed at 25 °C in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) without calcium and magnesium (Thermo Fisher). For each measurement, 15 µL of DPBS buffer was placed in the well for focusing, after which 5 µL of 50 to 100 nM protein was introduced and mixed. Movies were recorded for 60 s at 50 fps under standard settings. MP measurements were calibrated using protein standard mixture: β-amylase (56, 112, and 224 kDa), and thyroglobulin (670 kDa). MP data were processed using DiscoverMP (Refeyn Ltd.).

MD Simulations.

MD simulations were performed with YASARA Structure 18.2.7 using the md_runfast macro. For the starting conformation, a rigid body model of tPDE6C was generated. To model tPDE6C, two copies of the PDE6C GAF-B domain lacking the β1-β2 loop were extracted from the structure of the (PDE6C)2•(Pγr)2 complex, individually fit into the final map of tPDE6C using UCSF Chimera, and refined using NAMDinator. Next, two copies of the PDE6C catalytic subunits (Pt motif deleted) from the PDE6C structure were individually aligned with the two copies of the PDE6C GAF-B domain in the map of tPDE6C. The GAF-B β1-β2 loops were remodeled to remove clashes and place the loop contact residues with the catalytic domains in the exact same position as in holoPDE6C, and the resulting model was energy minimized with YASARA.

The simulations were run in cuboid simulation cells with 30 Å extension of the cell on each side of the protein using the AMBER14 force field in water at a temperature of 310°K, pH of 7.4, and NaCl concentration of 0.9%. Particle mesh Ewald summation was used to compute long-range columbic interactions with a periodic cell boundary and a cutoff of 8 Å. Four independent MD runs were performed with simulation times ranging from 460 to 550 ns.

Statistical Analyses.

Unless otherwise indicated, measurements were taken from at least three independent experiments, and data are shown as mean value and SD. Measurements between two groups were compared using the t test. GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used for data fitting and analysis.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grant RO1 EY-10843 to N.O.A. We would like to acknowledge use of resources at the Carver College of Medicine’s Protein and Crystallography Facility at the University of Iowa. We would like to thank Dr. Omar Davulcu (Pacific Northwest Center for Cryo-EM (PNCC), Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU)) for cryo-EM data collection. A portion of this research was supported by NIH grant U24GM129547 and performed at the PNCC at OHSU and accessed through Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory (grid.436923.9), a Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility sponsored by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research.

Author contributions

N.O.A. designed research; S.S., D.S., K.B., and N.O.A. performed research; S.S., D.S., and N.O.A. analyzed data; S.S. and D.S. input in manuscript writing; and N.O.A. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Some study data are available. Electron density maps and structure files have been deposited with the following PDB and EMDB IDs: 9CXH (49)/EMD-45991 (50), 9CXI (51)/EMD-45992 (52), 9CXJ (53)/EMD-45993 (54), 9CXG (55)/EMD-45990 (56), and EMD-45989 (57).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Arshavsky V. Y., Burns M. E., Current understanding of signal amplification in phototransduction. Cell. Logist. 4, e29390 (2014), 10.4161/cl.29390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu Y., Yau K. W., Phototransduction in mouse rods and cones. Pflugers Arch. 454, 805–819 (2007), 10.1007/s00424-006-0194-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noel J. P., Hamm H. E., Sigler P. B., The 2.2 A crystal structure of transducin-alpha complexed with GTP gamma S. Nature 366, 654–663 (1993), 10.1038/366654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palczewski K., et al. , Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science 289, 739–745 (2000), 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gulati S., Palczewski K., Engel A., Stahlberg H., Kovacik L., Cryo-EM structure of phosphodiesterase 6 reveals insights into the allosteric regulation of type I phosphodiesterases. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav4322 (2019), 10.1126/sciadv.aav4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majumder A., et al. , Exchange of cone for rod phosphodiesterase 6 catalytic subunits in rod photoreceptors mimics in part features of light adaptation. J. Neurosci. 35, 9225–9235 (2015), 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3563-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cote R. H., Photoreceptor phosphodiesterase (PDE6): Activation and inactivation mechanisms during visual transduction in rods and cones. Pflugers Arch. 473, 1377–1391 (2021), 10.1007/s00424-021-02562-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conti M., Beavo J., Biochemistry and physiology of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: Essential components in cyclic nucleotide signaling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 481–511 (2007), 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.150444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamazaki A., Sen I., Bitensky M. W., Casnellie J. E., Greengard P., Cyclic GMP-specific, high affinity, noncatalytic binding sites on light-activated phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 11619–11624 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X. J., Cahill K. B., Elfenbein A., Arshavsky V. Y., Cote R. H., Direct allosteric regulation between the GAF domain and catalytic domain of photoreceptor phosphodiesterase PDE6. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29699–29705 (2008), 10.1074/jbc.M803948200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamazaki A., Bartucca F., Ting A., Bitensky M. W., Reciprocal effects of an inhibitory factor on catalytic activity and noncatalytic cGMP binding sites of rod phosphodiesterase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 3702–3706 (1982), 10.1073/pnas.79.12.3702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mou H., Cote R. H., The catalytic and GAF domains of the rod cGMP phosphodiesterase (PDE6) heterodimer are regulated by distinct regions of its inhibitory gamma subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27527–27534 (2001), 10.1074/jbc.M103316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillespie P. G., Beavo J. A., cGMP is tightly bound to bovine retinal rod phosphodiesterase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 4311–4315 (1989), 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aplin C., Cerione R. A., Probing the mechanism by which the retinal G protein transducin activates its biological effector PDE6. J. Biol. Chem. 300, 105608 (2024), 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillespie P. G., Beavo J. A., Characterization of a bovine cone photoreceptor phosphodiesterase purified by cyclic GMP-sepharose chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 8133–8141 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta R., et al. , Structural analysis of the regulatory GAF domains of cGMP phosphodiesterase elucidates the allosteric communication pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 432, 5765–5783 (2020), 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granovsky A. E., et al. , Probing domain functions of chimeric PDE6alpha’/PDE5 cGMP-phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 24485–24490 (1998), 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh S., et al. , Reconstitution of the phosphodiesterase 6 maturation process important for photoreceptor cell function. J. Biol. Chem. 300, 105576 (2024), 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez S. E., et al. , The structure of the GAF A domain from phosphodiesterase 6C reveals determinants of cGMP binding, a conserved binding surface, and a large cGMP-dependent conformational change. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25913–25919 (2008), 10.1074/jbc.M802891200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grau T., et al. , Decreased catalytic activity and altered activation properties of PDE6C mutants associated with autosomal recessive achromatopsia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 719–730 (2011), 10.1093/hmg/ddq517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiadens A. A., et al. , Homozygosity mapping reveals PDE6C mutations in patients with early-onset cone photoreceptor disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 85, 240–247 (2009), 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gopalakrishna K. N., et al. , Mechanisms of mutant PDE6 proteins underlying retinal diseases. Cell Signal. 37, 74–80 (2017), 10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Georgiou M., et al. , Deep phenotyping of PDE6C-associated achromatopsia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 60, 5112–5123 (2019), 10.1167/iovs.19-27761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weisschuh N., et al. , Mutations in the gene PDE6C encoding the catalytic subunit of the cone photoreceptor phosphodiesterase in patients with achromatopsia. Hum. Mutat. 39, 1366–1371 (2018), 10.1002/humu.23606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gal A., et al. , Heterozygous missense mutation in the rod cGMP phosphodiesterase beta-subunit gene in autosomal dominant stationary night blindness. Nat. Genet. 7, 64–68 (1994), 10.1038/ng0594-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muradov K. G., et al. , Mutation in rod PDE6 linked to congenital stationary night blindness impairs the enzyme inhibition by its gamma-subunit. Biochemistry 42, 3305–3310 (2003), 10.1021/bi027095x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu S., et al. , Structural basis for the catalytic mechanism of human phosphodiesterase 9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13309–13314 (2008), 10.1073/pnas.0708850105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurley J. B., Stryer L., Purification and characterization of the gamma regulatory subunit of the cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase from retinal rod outer segments. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 11094–11099 (1982). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Punjani A., et al. , cryoSPARC: Algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017), 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muradov H., et al. , Analysis of PDE6 function using chimeric PDE5/6 catalytic domains. Vision Res. 46, 860–868 (2006), 10.1016/j.visres.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barren B., et al. , Structural basis of phosphodiesterase 6 inhibition by the C-terminal region of the gamma-subunit. EMBO J. 28, 3613–3622 (2009), 10.1038/emboj.2009.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rieke F., Baylor D. A., Molecular origin of continuous dark noise in rod photoreceptors. Biophys. J. 71, 2553–2572 (1996), 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79448-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikonov S., Lamb T. D., Pugh E. N. Jr., The role of steady phosphodiesterase activity in the kinetics and sensitivity of the light-adapted salamander rod photoresponse. J. Gen. Physiol. 116, 795–824 (2000), 10.1085/jgp.116.6.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z., et al. , Domain organization and conformational plasticity of the G protein effector, PDE6. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 12833–12843 (2015), 10.1074/jbc.M115.647636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gopalakrishna K. N., Boyd K., Yadav R. P., Artemyev N. O., Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein-like 1 is an obligate chaperone of phosphodiesterase 6 and is assisted by the gamma-subunit of its client. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 16282–16291 (2016), 10.1074/jbc.M116.737593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao Y., et al. , Structure of the visual signaling complex between transducin and phosphodiesterase 6. Mol. Cell 80, 237–245 (2020), 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H., et al. , Multiple conformations of phosphodiesterase-5: Implications for enzyme function and drug development. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21469–21479 (2006), 10.1074/jbc.M512527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muradov H., Boyd K. K., Kerov V., Artemyev N. O., PDE6 in lamprey Petromyzon marinus: Implications for the evolution of the visual effector in vertebrates. Biochemistry 46, 9992–10000 (2007), 10.1021/bi700535s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibson D. G., Enzymatic assembly of overlapping DNA fragments. Methods Enzymol. 498, 349–361 (2011), 10.1016/B978-0-12-385120-8.00015-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casanal A., Lohkamp B., Emsley P., Current developments in Coot for macromolecular model building of electron cryo-microscopy and crystallographic data. Protein Sci. 29, 1069–1078 (2020), 10.1002/pro.3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pettersen E. F., et al. , Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 30, 70–82 (2021), 10.1002/pro.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waterhouse A., et al. , SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W296–W303 (2018), 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee K., et al. , The structure of an Hsp90-immunophilin complex reveals cochaperone recognition of the client maturation state. Mol. Cell 81, 3496–3508 (2021), 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pettersen E. F., et al. , UCSF Chimera–A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004), 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kidmose R. T., et al. , Namdinator–Automatic molecular dynamics flexible fitting of structural models into cryo-EM and crystallography experimental maps. IUCrJ 6, 526–531 (2019), 10.1107/S2052252519007619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afonine P. V., et al. , Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 74, 531–544 (2018), 10.1107/S2059798318006551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Artemyev N. O., Hamm H. E., Two-site high-affinity interaction between inhibitory and catalytic subunits of rod cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase. Biochem. J. 283, 273–279 (1992), 10.1042/bj2830273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sonn-Segev A., et al. , Quantifying the heterogeneity of macromolecular machines by mass photometry. Nat. Commun. 11, 1772 (2020), 10.1038/s41467-020-15642-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Srivastava D., Singh S., Artemyev N., Structure of PDE6C in complex with the rod inhibitory Pγ subunit in the presence of cGMP. Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/9CXH. Deposited 31 July 2024.

- 50.Srivastava D., Singh S., Artemyev N., Structure of PDE6C in complex with the rod inhibitory Pγ subunit in the presence of cGMP. Electron Microscopy Databank. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-45991. Deposited 31 July 2024

- 51.Srivastava D., Singh S., Artemyev N., Structure of PDE6C in complex with the rod inhibitory Pγ subunit in the absence of added cGMP. Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/9CXI. Deposited 31 July 2024.

- 52.Srivastava D., Singh S., Artemyev N., Structure of PDE6C in complex with the rod inhibitory Pγ subunit in the absence of added cGMP. Electron Microscopy Databank. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-45992. Deposited 31 July 2024.

- 53.Srivastava D., Singh S., Artemyev N., Structure of PDE6C in complex with the rod inhibitory Pγ subunit with disordered GAF-A region. Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/9CXJ. Deposited 31 July 2024.

- 54.Srivastava D., Singh S., Artemyev N., Structure of PDE6C in complex with the rod inhibitory Pγ subunit with disordered GAF-A region. Electron Microscopy Databank. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-45993. Deposited 31 July 2024.

- 55.Srivastava D., Singh S., Artemyev N., Structure of PDE6C in complex with the cone inhibitory Pγ subunit in the presence of cGMP. Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/9CXG. Deposited 31 July 2024.

- 56.Srivastava D., Singh S., Artemyev N., Structure of PDE6C in complex with the cone inhibitory Pγ subunit in the presence of cGMP. Electron Microscopy Databank. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-45990. Deposited 31 July 2024.

- 57.Srivastava D., Singh S., Artemyev N., Structure of PDE6C without the inhibitory Pγ subunit. Electron Microscopy Databank. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-45989. Deposited 31 July 2024.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

Some study data are available. Electron density maps and structure files have been deposited with the following PDB and EMDB IDs: 9CXH (49)/EMD-45991 (50), 9CXI (51)/EMD-45992 (52), 9CXJ (53)/EMD-45993 (54), 9CXG (55)/EMD-45990 (56), and EMD-45989 (57).