Abstract

Background

In a phase 1b/2a clinical trial of efzofitimod in patients with corticosteroid-requiring pulmonary sarcoidosis, treatment resulted in dose-dependent improvement in key end-points. We undertook a post hoc analysis pooling dose arms that achieved therapeutic concentrations of efzofitimod (Therapeutic group) versus those that did not (Subtherapeutic group).

Methods

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells incubated with tuberculin-coated beads were exposed to varying concentrations of efzofitimod in an in vitro assay to determine concentrations that inhibited granuloma formation. In the post hoc analysis, we compared time-to-first-relapse and changes in pulmonary function after a protocolised corticosteroid taper in the Therapeutic and Subtherapeutic groups.

Results

Efzofitimod at ≥300 nM (19 µg·mL−1) inhibited granuloma formation in vitro. Based on mean efzofitimod serum concentrations achieved in the phase 1b/2a study, the 3 and 5 mg·kg−1 dose arms were pooled as the Therapeutic group, while the 1 mg·kg−1 arm was pooled with the placebo arm as the Subtherapeutic group. Relapse rates were 54.4% and 7.7% in the Subtherapeutic group and Therapeutic group, respectively. Median time-to-first-relapse in the Subtherapeutic group was 126 days, whereas in the Therapeutic group, only one of 17 patients relapsed by the end of the 24-week study (p=0.017). Slopes analysis showed that forced vital capacity increased in the Therapeutic group, but decreased in the Subtherapeutic group, over the course of the trial (p=0.035).

Conclusion

Treatment with efzofitimod at therapeutic doses, as compared with a subtherapeutic dose or placebo, was associated with a lower rate of relapse as corticosteroids were tapered.

Shareable abstract

This post hoc analysis of a phase 1b/2a trial, informed by results from an in vitro assay, shows that therapeutic doses of efzofitimod decreased relapses after tapering corticosteroids in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis https://bit.ly/4dJfqCf

Introduction

Efzofitimod (formerly ATYR1923; aTyr Pharma, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), a novel immunomodulatory agent currently in development for the treatment of interstitial lung disease, was found in a recent multiple ascending dose (1, 3 and 5 mg·kg−1) phase 1b/2a study to be safe and well tolerated in patients with chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis on corticosteroids [1]. The study also showed a dose- and exposure (concentration)-dependent reduction of the mean daily dose of oral corticosteroid needed to maintain disease stability, with concomitant increases in quality of life scores and a trend towards improvement in pulmonary function [1, 2]. The exposure-dependent response in the phase 1b/2a study implied that efzofitimod was most effective at higher doses, while less effective or not effective at lower doses. In drug development, the relationship between exposure and response is often established from in vitro assays. The current study was designed to examine the relationship between concentrations of efzofitimod that are effective in vitro and efficacy outcomes in sarcoidosis patients treated with different doses of the drug in the phase 1b/2a trial.

The hallmark of sarcoidosis is formation of non-caseating granulomas in the lungs and other affected tissues. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with sarcoidosis can also form granulomas in culture, and this process can be quantified using an in vitro granuloma formation assay [3, 4]. In the in vitro assay, PBMCs cultured in the presence of tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) aggregate and form multicellular structures with histopathological and molecular features that closely resemble those of granulomas in human sarcoidosis tissues [5, 6]. The assay provides a platform for testing the ability of drugs to inhibit granuloma formation in vitro and for determining concentrations at which a test drug may be efficacious in vivo. As such, the in vitro assay was recently used to predict the dose range expected to be effective in a clinical study of a monoclonal antibody being developed for treatment of sarcoidosis [4]. In the current study, we applied a similar approach to determine concentrations of efzofitimod that inhibit granuloma formation in vitro, and related the results to serum concentrations of the drug achieved with the doses used in the phase 1b/2a trial.

Here we present a post hoc analysis of the phase 1b/2a study demonstrating the favourable effects of treatment with efzofitimod at doses determined to be therapeutic based on the in vitro assay, as compared to a subtherapeutic dose pooled with placebo, on relapse rates and pulmonary function in subjects with chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis while they underwent a protocolised oral corticosteroid taper.

Methods

In vitro study

Blood for the in vitro assay was drawn under a protocol approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board. The assay protocol was similar to that previously described [3, 4]. All enrolled subjects (n=8) had active pulmonary sarcoidosis, were nonsmokers, had a negative tuberculin skin test and/or QuantiFERON-TB Gold test, and had not been treated with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive medications (e.g. methotrexate, azathioprine, anti-tumour necrosis factor monoclonal antibodies) in the preceding 6 months. Sarcoidosis was deemed to be active based on the presence of intolerable symptoms, progressive lung dysfunction and/or high risk for other organ damage due to the disease, as assessed by one of the authors, who is a sarcoidosis specialist physician (E.D. Crouser). Prior to initiation of treatment, blood was drawn for isolation of PBMCs. PBMCs were plated and cultured for 7 days in the presence of either uncoated polystyrene beads (UNC) or beads coated with tuberculin PPD [3, 7]. In addition, PBMCs were treated with either vehicle or efzofitimod at 30 nM, 300 nM or 1 µM, or prednisone at 1 or 10 µM as positive control, for 30 min prior to addition of PPD-coated beads and throughout the subsequent 7-day culture period. After 7 days, granuloma formation was evaluated by light microscopy, analysed using Materials Image Processing and Automated Reconstruction (MIPAR v2.2.5; Worthington, OH, USA), and expressed as area fraction per cent of uncoated beads, as previously described [3, 4, 7].

Statistical analysis: in vitro study

Data derived from independent experiments were expressed as boxplots. Statistical impact relative to sample size was further evaluated by employing Cohen's d effect size [8], which considers the magnitude of the change in the experimental value and the standard deviation of the measurements (i.e., a sensitivity index). A strong effect size is reflected by a Cohen's d value exceeding 0.8 [8]. SigmaPlot 15.0 and SYSTAT 13.2 (Grafiti LLC, Palo Alto, CA, USA) software were used for graphics and statistical analysis, respectively. The significance of differences in granuloma area fraction among treatment groups was assessed with the Mann–Whitney U-test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Post hoc analysis of phase 1b/2a clinical trial

A post hoc analysis was performed on data from the previously reported phase 1b/2a study [1]. Briefly, the clinical study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with three sequential ascending dose cohorts. Subjects were randomised 2:1 to receive either efzofitimod (1, 3 or 5 mg·kg−1 in the first, second and third cohorts, respectively) or placebo. The study enrolled symptomatic (Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnoea Scale score ≥1) subjects with a ≥6-month history of biopsy-confirmed sarcoidosis [9], pulmonary parenchymal involvement detected by chest imaging and treatment with oral corticosteroids (OCS) at a prednisone-equivalent dose of 10 to 25 mg·day−1 without change for at least 4 weeks. Concomitant treatments (other than biologics) [10] for sarcoidosis were allowed and required to be maintained at a stable dose for the duration of the study. Subjects in each cohort received six doses of efzofitimod or placebo, administered intravenously at 4-week intervals. During the course of the trial, subjects were required to decrease their OCS dose as outlined in a pre-specified taper protocol. A successful taper was defined as reduction of the OCS dose to a prednisone-equivalent of 5 mg per day or less for at least 5 consecutive days. The protocol allowed for return to a higher OCS dose as “rescue” therapy for increased symptoms (cough or dyspnoea) judged by the investigator to represent significant clinical worsening. Time-to-first-relapse was defined as the interval from the date of the first successful OCS taper to the date when “rescue” therapy was first required. Increases in OCS dose for reasons other than worsening sarcoidosis were not counted as relapses.

The key efficacy parameters for the post hoc analysis were time-to-first-relapse and changes in pulmonary function. The pulmonary function parameters evaluated included forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Per cent predicted values for FVC and FEV1 were determined using race/ethnicity-specific Global Lung Initiative (GLI) reference equations [11] based on patients’ self-reported race/ethnicity. Per cent predicted values for DLCO were determined using reference equations in place at each study centre at the time of the trial.

Statistical analysis: post hoc study

Bsased on findings from the in vitro granuloma formation study (see Results below), the 3 and 5 mg·kg−1 dose arms were pooled as the Therapeutic group, and the 1 mg·kg−1 arm was pooled with the placebo arm as the Subtherapeutic group. The primary efficacy analysis was in the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population, defined as all randomised patients who received at least one administration of study drug or placebo. We compared the Therapeutic and Subtherapeutic groups for end-points pre-specified in the Statistical Analysis Plan, including time-to-first-relapse after OCS taper, and changes in FVC, FEV1 and DLCO % predicted (DLCO pp) over the 24 weeks of the study. Time-to-first-relapse in the two groups was analysed with the log-rank test and is presented as a Kaplan–Meier plot. Subjects who were not able to taper their OCS dose to 5 mg prednisone-equivalent or less during the study were included in the analysis as censored values on Day 1. Changes in FVC and FEV1 over the course of the trial in the two groups were analysed using the random coefficient regression model (RCRM), as in the primary publication [1]. An interaction term was added to the RCRM to assess whether there was evidence that improvements in FVC were consistent for patients with differing values of FEV1/FVC ratio at baseline (data not shown). The change from baseline in DLCO pp at weeks 12, 20 and 24 was calculated for each individual, and the significance of differences between treatment groups was analysed using a mixed-effects model for repeated measures. Baseline pulmonary function values were used as covariates in the analysis. For all tests, statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

In vitro study

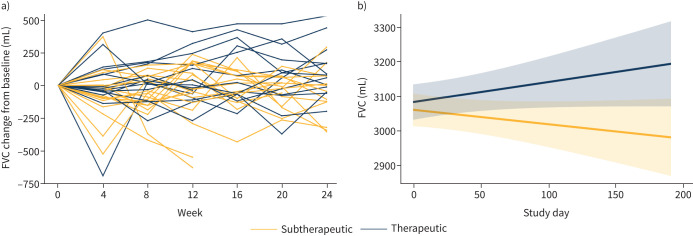

Eight subjects were studied (supplementary table S1). The half maximal effective concentration (EC50) for efzofitimod binding to its human receptor neuropilin 2 [12] is 30 nM (1.9 µg·mL−1) [13]. Thus, we tested the effect of efzofitimod at 30 nM, 300 nM and 1 µM on granuloma formation in the in vitro assay. Treatment with efzofitimod at 30 nM (1.9 μg·mL−1) did not significantly affect granuloma formation; whereas treatment at 300 nM decreased granuloma area fraction by ∼60% (p<0.05) (figure 1). Based on the finding that efzofitimod at 300 nM (19 µg·mL−1) reduced granuloma formation in vitro, we considered this concentration as one that would potentially be therapeutically effective in patients with sarcoidosis.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of efzofitimod (Efzo) and prednisone (Pred) on granuloma size in the in vitro assay. In the absence of an inhibitory drug, PPD-coated beads (PPD) stimulated granulomas occupying an area ∼4.5-fold greater than the area occupied by aggregates formed in response to uncoated beads (UNC). Treatment with efzofitimod at 300 nM and 1 μM and prednisone at 10 μM significantly decreased the area occupied by granulomas stimulated by PPD-coated beads. Granuloma formation is represented as relative granuloma area fraction, calculated as the fraction of imaged area occupied by granulomas stimulated by PPD-coated beads divided by the fraction of imaged area occupied by aggregates formed in the presence of uncoated beads, expressed as per cent. Boxplots show the minimum, first quartile (25th percentile), median, third quartile (75th percentile) and maximum for each condition. n=8; *p<0.05 (Cohen's d >1.7) and **p<0.01 (Cohen's d >2.2) compared to stimulation with PPD-coated beads alone; ***p<0.001 (Cohen's d >2.4) compared to culture with uncoated beads (UNC). PPD: purified protein derivative.

Post hoc analysis of the Phase 1b/2a trial

The area under the efzofitimod concentration-time curve (AUC) over the 4-week (672-h) dosing interval for the 1, 3 and 5 mg·kg−1 dose groups was 3710, 12 077 and 16 122 µg·h·mL−1, respectively. The calculated average concentration (Cavg) over the dosing interval (AUC in µg·h·mL−1 divided by 672 h) at 1 mg·kg−1 (5.5 µg·mL−1) was less than the effective concentration in the in vitro assay, while that for the 3 mg·kg−1 (18.0 µg·mL−1) and 5 mg·kg−1 (24.0 µg·mL−1) doses was similar to or greater than the concentration that inhibited granuloma formation in vitro (19 µg·mL−1). Therefore, for the post hoc analysis, the 3 mg·kg−1 and 5 mg·kg−1 cohorts were considered to have received effective doses of efzofitimod and pooled as the Therapeutic group, while the 1 mg·kg−1 cohort arm was considered to have received a less than effective dose of the drug and pooled with the placebo cohort as the Subtherapeutic group.

Patient characteristics

The phase 1b/2a study enrolled 37 subjects. Based on the justification for pooling described above, 20 were pooled in the Subtherapeutic group, and 17 were pooled in the Therapeutic group. Demographics, disease characteristics, and baseline immunosuppressive therapies for subjects in the two groups are shown in table 1. The mean age of study participants was 52.4 years, 54% were female, and 38% were African American. Pulmonary function parameters were notable for mild to moderate reductions in FVC, FEV1 and DLCO in both the Subtherapeutic and Therapeutic groups. At enrolment, all patients were on oral corticosteroid therapy at prednisone-equivalent doses of 10 to 25 mg·day−1, and 14 of 37 (38%) were also on non-steroid immunomodulatory medications. The mean prednisone-equivalent dose at baseline was 13.2 mg, and at least 20% of patients in each group were on ≥20 mg·day−1. Baseline measures were defined as the last measure assessed on or before the first efzofitimod (or placebo) dose. Overall, demographics, disease parameters and baseline medications were similar in the two groups.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics, baseline disease characteristics and baseline immunosuppressive therapy

| Subtherapeutic | Therapeutic | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients n | 20 | 17 |

| Patient demographics | ||

| Age years, mean±sd (≥65 years) | 53.3±10.4 (1) | 51.2±10.0 (2) |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 11 (55) | 9 (53) |

| Race (White/African American), n | 14/6 | 9/8 |

| Baseline disease characteristics, mean±sd | ||

| FVC % pred | 73.7±11.5 | 83.8±12.7 |

| FVC mL | 2816±739 | 3396±1018 |

| FEV1 % pred | 65.2±17.0 | 77.5±15.6 |

| FEV1 mL | 1942.3±546.8 | 2502.6±915.9 |

| DLCO % pred | 62±20 | 67±20 |

| Duration of disease years | 5.5±4.7 | 6.9±7.9 |

| Baseline Dyspnoea Index Score | 4.6±1.8 | 6.9±2.7 |

| Baseline therapy, n (%) | ||

| Prednisone-equivalent dose mg·day−1 | ||

| 20–25 | 4 (20) | 4 (24) |

| 15 to <20 | 2 (10) | 5 (29) |

| 10 to <15 | 14 (70) | 8 (47) |

| Mean | 12.5 | 14.1 |

| Non-steroid immunomodulator | 9 (45) | 5 (29) |

| Methotrexate | 6 | 3 |

| Azathioprine | 2 | 1 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1 | 0 |

| Leflunomide | 0 | 1 |

FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide.

Efficacy assessments

Relapse and time-to-first-relapse

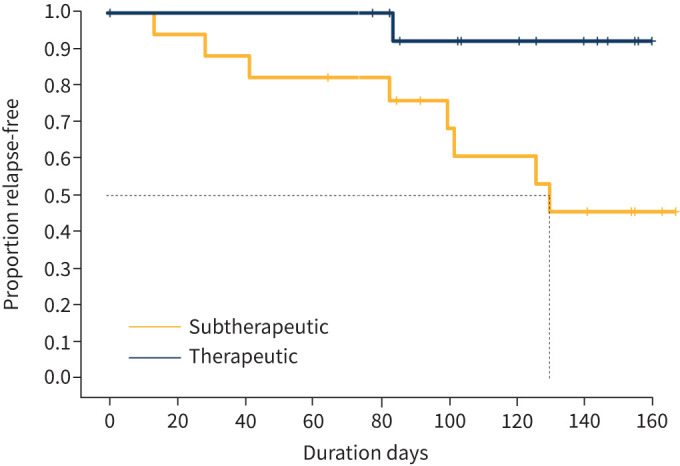

Of the 37 randomised patients, 32 achieved a reduction of OCS to a prednisone-equivalent dose of ≤5 mg for at least 5 consecutive days. Of the five patients who were unable to taper to 5 mg or less, three were in the Subtherapeutic group and two were in the Therapeutic group. As shown in figure 2, time-to-first-relapse was significantly shorter in the Subtherapeutic group than in the Therapeutic group. The median time-to-first-relapse in the Subtherapeutic group was 126 days, whereas only one of 17 patients in the Therapeutic group had relapsed by the end of the study (p=0.017). The relapse rate in the Subtherapeutic group was 54.4%, compared to 7.7% in the Therapeutic group (table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Time-to-first-relapse after oral corticosteroid taper in the Subtherapeutic and Therapeutic groups. There were fewer relapses, and time to-first-relapse was significantly longer in the Therapeutic group compared to the Subtherapeutic group (log-rank test, p=0.017).

TABLE 2.

Time-to-first-relapse and pulmonary function by treatment group

| Subtherapeutic# | Therapeutic¶ | Treatment effect | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapses | ||||

| Subjects tapered, n | 17 | 15 | ||

| Subjects with relapse, n (%) | 8 (54.4) | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Time-to-first-relapse days, median | 126 | NE | NE | 0.017 |

| FVC | ||||

| n | 13 | 13 | ||

| Week 24 FVC mL, mean±sd | 2537±818 | 3615±1253 | ||

| Week 24 FVC mL, adjusted mean+ | 2985 | 3165 | 180 | 0.035 |

| FEV1 | ||||

| n | 13 | 13 | ||

| Week 24 FEV1 mL, mean±sd | 1734±961 | 2685±1047 | ||

| Week 24 FEV1 mL, adjusted mean+ | 2146 | 2232 | 86 | 0.196 |

| D LCO | ||||

| Baseline | ||||

| n | 19 | 14 | ||

| % pred, mean±sd | 62±20 | 67±20 | ||

| Week 12 | ||||

| n | 17 | 9 | ||

| %, mean±sd | 61±20 | 68±26 | ||

| %, adjusted mean§ | 57.9 | 67.2 | 9.3 | 0.013 |

| Week 20 | ||||

| n | 12 | 11 | ||

| %, mean±sd | 60±18 | 68±23 | ||

| %, adjusted mean§ | 61.2 | 63.5 | 2.3 | 0.630 |

| Week 24 | ||||

| n | 10 | 11 | ||

| %, mean±sd | 53±15 | 70±23 | ||

| %, adjusted mean§ | 57.7 | 65.1 | 7.4 | 0.104 |

NE: not estimable; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide. #: n=20; ¶: n=17; +: based on a slopes analysis adjusted for covariates; §: based on mixed model for repeated measures adjusted for covariates.

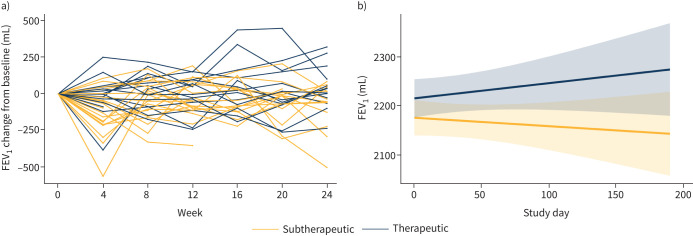

FVC and FEV1

A slopes analysis showed that over the course of the trial, FVC increased from baseline in the Therapeutic group, but decreased from baseline in the Subtherapeutic group (p=0.035; figure 3b). The mean FVC at the end of the study was 3165 mL in the Therapeutic group and 2985 mL in the Subtherapeutic group (mean difference 180 mL, p=0.035; table 2). The results were similar when the data were analysed as FVC per cent predicted (FVCpp; data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Change in forced vital capacity (FVC) over the course of the study in the Subtherapeutic and Therapeutic groups. a) Change from baseline in FVC for individual patients in the Subtherapeutic and Therapeutic groups; b) slopes analysis of change in FVC in the Subtherapeutic and Therapeutic groups. Pale yellow and blue areas represent 95% confidence limits of the slopes for the Subtherapeutic and Therapeutic groups, respectively. The FVC increased in the Therapeutic group and decreased in the Subtherapeutic group over the course of the study, and the difference in FVC slopes between the two groups was significant (p=0.035).

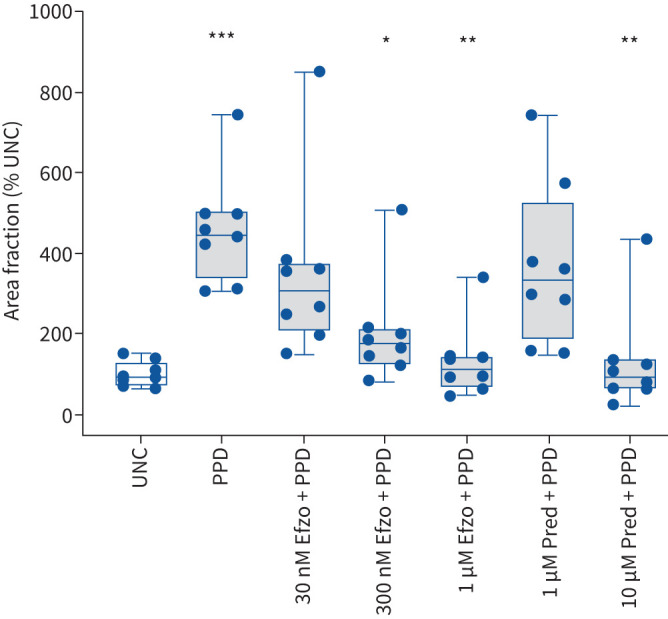

Slopes analysis also showed that FEV1 increased in the Therapeutic group, but decreased in the Subtherapeutic group, over the course of the trial, although the trend did not reach statistical significance (p=0.196; figure 4 and table 2). This was also the case when the data were analysed as FEV1 per cent predicted (data not shown). There was no evidence that variation in baseline FEV1/FVC was associated with differential effects of efzofitimod on FVC (p=0.466; interaction test).

FIGURE 4.

Change in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) over the course of the study in the Subtherapeutic and Therapeutic groups. a) Change from baseline in FEV1 for individual patients in the Subtherapeutic and Therapeutic groups; b) slopes analysis of change in FEV1 in the Subtherapeutic and Therapeutic groups. Pale yellow and blue areas represent 95% confidence limits of the slopes for the Subtherapeutic and Therapeutic groups, respectively. The FEV1 increased in the Therapeutic group and decreased in the Subtherapeutic group over the course of the study, but the difference in FEV1 slopes between the two groups was not significant (p=0.196).

D LCO

We were unable to perform a slopes analysis for DLCO measurements over the course of the trial because DLCO was only measured at a few selected times during the trial. However, by the end of the 24-week study, the adjusted mean per cent predicted DLCO was 7.4% greater in the Therapeutic group than in the Subtherapeutic group (table 2). While this change favoured the Therapeutic group, the trend did not reach statistical significance (p=0.104).

Discussion

In the phase 1b/2a trial, efzofitimod was safe and well tolerated, and treatment was associated with statistically significant dose-dependent improvement in patient-related outcomes assessed using multiple validated sarcoidosis-specific instruments [1]. Although the study was not powered to determine the drug's efficacy in maintaining disease control as OCS were tapered or in terms of pulmonary function, treatment was associated with dose-dependent trends towards improvement in these secondary end-points. In addition, Walker et al. [2] recently performed an exposure–response analysis that revealed exposure-dependent trends supporting the efficacy of efzofitimod in OCS tapering and FVC. These findings prompted the current post hoc analysis, in which we leveraged the opportunity to determine a concentration of efzofitimod that effectively inhibited granuloma formation in vitro in order to identify which dose(s) of the drug used in the clinical trial resulted in serum concentrations that might similarly inhibit granulomatous inflammation in vivo, and thereby further evaluate its therapeutic potential in patients with sarcoidosis.

The in vitro human granuloma formation assay we employed is an established model that recapitulates morphological and molecular features of granulomas in patients with sarcoidosis [3, 5, 6]. The assay has been used previously to determine the concentration of another agent in development for treatment of sarcoidosis to inform the dose range to be tested in a clinical trial [4]. In the current study, we found that efzofitimod at 300 nM (19 µg·mL−1) significantly inhibited granuloma formation in vitro (figure 1). Pharmacokinetic data from the clinical trial indicated that the Cavg for the 3 mg·kg−1 dose cohort (18 µg·mL−1) was similar to, and for the 5 mg·kg−1 cohort (24 µg·mL−1) above, the effective concentration in vitro. On the other hand, the Cavg for the 1 mg·kg−1 cohort was well below the effective concentration in vitro. This provided the rationale to pool the 3 and 5 mg·kg−1 cohorts as the Therapeutic group, and the 1 mg·kg−1 cohort with the placebo cohort as the Subtherapeutic group, then to compare outcomes in the two groups.

Time-to-first-relapse after an initial successful OCS taper and change in FVC over the course of the study were pre-specified secondary and exploratory end-points, respectively, in the phase 1b/2a clinical trial. Our analysis shows a highly significant reduction in relapses after OCS taper in the Therapeutic group (7.7%) compared to the Subtherapeutic group (54.4%) and a markedly longer time-to-first-relapse in the Therapeutic group (figure 2, table 2). Regarding changes in pulmonary function, FVC increased in the Therapeutic group and decreased in the Subtherapeutic group over the course of the trial, such that the mean FVC was significantly (180 mL) greater in the Therapeutic group than the Subtherapeutic group at the end of the trial (figure 3b, table 2). FEV1 similarly increased in the Therapeutic group and decreased in the Subtherapeutic group, although the difference at the end of the trial (86 mL) did not reach statistical significance (figure 4b, table 2). Notably, it was the pooling of treatment cohorts into Therapeutic and Subtherapeutic groups based on results from the in vitro granuloma assay that allowed us to glean the therapeutic benefit of efzofitimod with respect to these secondary end-points in the clinical trial.

The European Respiratory Society (ERS) clinical practice guidelines recommend corticosteroids as first-line therapy for treatment of symptomatic pulmonary sarcoidosis to improve or preserve pulmonary function and quality of life [10]. The ERS guidelines also recommend methotrexate or other non-steroid immunomodulators in patients who have continued disease activity despite corticosteroid therapy to improve or preserve pulmonary function [10]. Conversely, discontinuing corticosteroids has been associated with clinical worsening in pulmonary sarcoidosis [14]. In the phase 1b/2a efzofitimod clinical trial [1], all patients were treated with corticosteroids and 14/37 (38%) were on methotrexate or another non-steroid immunomodulator at study entry (table 2). In this context, the reduction in relapses and improvement in FVC and FEV1 in the Therapeutic group at the same time that corticosteroids were tapered strongly suggests a therapeutic benefit of efzofitimod at the 3 and 5 mg·kg−1 doses.

While corticosteroids have been the cornerstone of sarcoidosis therapy for decades, long-term treatment, especially at high doses, is associated with substantial toxicity and decreased quality of life [15–17]. Therefore, the ability of a new therapy to maintain disease control while discontinuing or lowering the dose of corticosteroids is an outcome of clinical importance that is also meaningful to patients. The post hoc analysis presented here suggests that therapeutic doses of efzofitimod can be effective in achieving this goal.

To assess the effect of efzofitimod on lung function, we focused on three pulmonary function parameters: FVC, FEV1 and DLCO. On average, each of these was mildly to moderately decreased in our study population (table 1). These results are similar to those recently reported from a large tertiary sarcoidosis specialty centre [18]. In that study, 56% of patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis had abnormal lung function. Of these, 47% had restrictive impairment, 22% had obstructive impairment, 16% had combined restriction and obstruction, and 15% had an isolated reduction in DLCO [18]. Consistent with the observation that restrictive impairment is the most common physiological abnormality in pulmonary sarcoidosis, FVC is the most frequently reported pulmonary function parameter in clinical studies, and the one most likely to improve in response to therapy [19]. Likewise, efzofitimod treatment had the largest impact on FVC, which increased in the Therapeutic group and decreased in the Subtherapeutic group, leading to a statistically significant difference of 180 mL by the end of the 24-week study (figure 3, table 2). This degree of difference in FVC is large by comparison with the effect of infliximab in the landmark randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial with that agent [20], and in the same range as the increase in FVC seen in two uncontrolled case series in which infliximab was used at higher doses [21, 22]. Although not approved for use in sarcoidosis by either the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency, infliximab is now guideline-recommended therapy for severe sarcoidosis that cannot be controlled with corticosteroids and other immunomodulators [10].

Like FVC, FEV1 increased progressively in the Therapeutic group and decreased in the Subtherapeutic group over the course of the 24-week clinical trial, although the difference between the groups did not reach statistical significance (figure 4, table 2). Similarly, DLCO increased in the Therapeutic group and decreased in the Subtherapeutic group, but the difference was not significant at the end of the trial (table 2). To determine the importance of the trends toward improvement in FEV1 and DLCO in response to efzofitimod, larger clinical trials are required.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, it has the inherent limitation of a post hoc analysis of data from a prospective study. Mitigating this, however, the outcomes we analysed were pre-specified end-points in the phase 1b/2a clinical trial. In addition, we used the same mITT approach and data handling rules specified in advance and applied in the primary report of results from the clinical trial [1].

Second, while equating the concentration of efzofitimod that decreased granuloma formation in the in vitro assay to a serum concentration expected to be therapeutically efficacious in sarcoidosis patients is a rational approach, whether activity in vitro correlates with the ability to suppress granulomatous inflammation in vivo has not been established. Importantly, our finding that relapses decreased and pulmonary function improved while corticosteroids were tapered in the Therapeutic group suggests that an in vitro–in vivo correlation may indeed exist.

Third, there are no universally accepted criteria for relapse in pulmonary sarcoidosis, and various studies have defined relapse differently [23–26]. Most authors consider recurrent symptoms, worsening radiographic findings, and/or decline in pulmonary function occurring within 1 to 12 months after medication taper as markers of disease relapse [23–26]. Since radiographic findings may not worsen and pulmonary function may not decline before symptoms increase as corticosteroids are tapered, particularly when other immunomodulatory therapy is in place, our study focused on recurrence of symptoms as the primary indicator of relapse or disease progression. In the double-blind clinical trial, investigators at each study site were required to adjudicate whether any report of new symptoms was due to worsening sarcoidosis or attributable to another cause in order to ensure that relapses were properly captured, and that resumption of prednisone or a dose increase for non-sarcoidosis reasons was not counted [26].

Finally, the primary end-point of the phase 1b/2a trial was safety and tolerability of efzofitimod at a range of doses (1, 3 and 5 mg·kg−1), while effects on steroid tapering and on pulmonary function were secondary and exploratory end-points, respectively. The sample size was therefore small, such that the study was not powered to show therapeutic efficacy. For this reason, the favourable effects of efzofitimod on relapse rates and pulmonary function in the Therapeutic group (pooled 3 and 5 mg·kg−1 dose cohorts) shown in our post hoc analysis must be considered preliminary evidence of clinical benefit. An ongoing phase 3 trial of efzofitimod at 3 and 5 mg·kg−1 versus placebo over 48 weeks has a targeted enrolment of 264 subjects with corticosteroid-requiring pulmonary sarcoidosis [27]. Hopefully, this study will provide definitive evidence as to the efficacy of efzofitimod in preventing relapses, preserving pulmonary function and other clinical outcomes while tapering corticosteroids.

Conclusion

In conclusion, using an established assay with cultured human PBMCs, we identified a concentration of efzofitimod at or above which granuloma formation was inhibited in vitro. This, in combination with pharmacokinetic data from the phase 1b/2a study, allowed us to designate patients treated with efzofitimod at 3 and 5 mg·kg−1 as having received therapeutic doses (the Therapeutic group) and those dosed at 1 mg·kg−1 as having received a subtherapeutic dose (combined with the placebo cohort as the Subtherapeutic group). Our post hoc analysis revealed that over half of patients in the Subtherapeutic group relapsed after a successful corticosteroid taper, while fewer than 10% of those in the Therapeutic group relapsed. The analysis also showed that efzofitimod at therapeutic doses favourably impacted pulmonary function: FVC increased significantly, and there were trends towards improvement in FEV1 and DLCO in the Therapeutic group compared to the Subtherapeutic group. These findings build upon the results reported from the primary analysis of the phase 1b/2a trial [1] and subsequent exposure–response analysis [2] supporting the efficacy of efzofitimod in allowing corticosteroid tapering and improving quality of life measures and stability of pulmonary function in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Ultimately, however, the true therapeutic benefit of efzofitimod as a novel biologic therapy for sarcoidosis will depend on larger randomised controlled studies, such as the phase 3 clinical trial currently underway.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00536-2024.SUPPLEMENT (603.5KB, pdf)

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Naresh Hegde (RxMD, Chennai, India) for proofreading and submission of the manuscript.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Ethics statement: The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were reviewed and approved by the central Western Institutional Review Board–Copernicus Group, North Carolina (IRB00000533), and the following local boards: Cleveland Clinic, Ohio (IRB00000684); Medical University of South Carolina, South Carolina (IRB00001888); University of Illinois, Illinois (IRB00000083); University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Texas. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Conflict of interest: O.N. Obi has received support for the conduct of clinical trials from aTyr Pharma, Novartis, Kinevant and Xentria, has served as consultant for CSL-Behring and Xentria, served on the scientific advisory board (SAB) of the Foundation of Sarcoidosis Research, and currently serves on the SAB of the Ann Theodore Foundation. E.D. Crouser has received grant support from aTyr Pharma, Xentria, 23&ME, Star Therapeutics, Milken Institute/Ann Theodore Foundation and the Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research, and has served as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim, SarcoMedUSA and Merck. M.W. Julian and L.W. Locke have no conflict of interest to declare. A. Chandrasekaran, P. Ramesh, N. Kinnersley and V. Niranjan declare that support provided by them was contracted and funded by aTyr Pharma. R.P. Baughman has received support for clinical trials from aTyr Pharma, Celgene, Actelion, Genentech, Gilead, Bellerophon, Bayer, Mallinckrodt and the Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research, and served as consultant to AstraZeneca, Actelion, aTyr, Kinevant, Xentria, Mallinckrodt, Boehringer Ingelheim, Foresee Pharmaceuticals and the Ann Theodore Foundation, and been on a speaker's bureau for Mallinckrodt. D.A. Culver has received grant support and/or consulting fees from the Ann Theodore Foundation, aTyr Pharma, Kinevant, Molecure, Mallinckrodt, Merck, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Foree Pharmaceuticals and the Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research. P.H.S. Sporn has received support for the conduct of clinical trials from aTyr Pharma, Novartis, Xentria and the Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research, and has served as a consultant to ANI Pharmaceuticals.

Support statement: This study was supported by aTyr Pharma.

References

- 1.Culver DA, Aryal S, Barney J, et al. Efzofitimod for the treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Chest 2023; 163: 881–890. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2022.10.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker G, Adams R, Guy L, et al. Exposure-response analyses of efzofitimod in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Front Pharmacol 2023; 14: 1258236. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1258236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crouser ED, White P, Caceres EG, et al. A novel in vitro human granuloma model of sarcoidosis and latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2017; 57: 487–498. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0321OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Offman E, Singh N, Julian MW, et al. Leveraging in vitro and pharmacokinetic models to support bench to bedside investigation of XTMAB-16 as a novel pulmonary sarcoidosis treatment. Front Pharmacol 2023; 14: 1066454. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1066454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhargava M, Liao SY, Crouser ED, et al. The landscape of transcriptomic and proteomic studies in sarcoidosis. ERJ Open Res 2022; 8: 00621-2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00621-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Locke LW, Crouser ED, White P, et al. IL-13-regulated macrophage polarization during granuloma formation in an in vitro human sarcoidosis model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2019; 60: 84–95. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0053OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crouser ED, Locke LW, Julian MW, et al. Phagosome-regulated mTOR signalling during sarcoidosis granuloma biogenesis. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2002695. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02695-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd Edn. Hillsdale, NJ, L. Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, et al. Diagnosis and detection of sarcoidosis. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 201: e26–e51. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202002-0251ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baughman RP, Valeyre D, Korsten P, et al. ERS clinical practice guidelines on treatment of sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J 2021; 58: 2004079. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04079-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: 1324–1343. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baughman RP, Niranjan V, Walker G, et al. Efzofitimod: a novel anti-inflammatory agent for sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2023; 40: e2023011. doi: 10.36141/svdld.v40i1.14396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Z, Chong Y, Crampton S, et al. ATYR1923 specifically binds to neuropilin-2, a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of immune-mediated diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 201: A3074. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pietinalho A, Tukiainen P, Haahtela T, et al. Oral prednisolone followed by inhaled budesonide in newly diagnosed pulmonary sarcoidosis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study. Finnish Pulmonary Sarcoidosis Study Group. Chest 1999; 116: 424–431. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.2.424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judson MA, Chaudhry H, Louis A, et al. The effect of corticosteroids on quality of life in a sarcoidosis clinic: the results of a propensity analysis. Respir Med 2015; 109: 526–531. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan NA, Donatelli CV, Tonelli AR, et al. Toxicity risk from glucocorticoids in sarcoidosis patients. Respir Med 2017; 132: 9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broos CE, Poell LHC, Looman CWN, et al. No evidence found for an association between prednisone dose and FVC change in newly-treated pulmonary sarcoidosis. Respir Med 2018; 138S: S31–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharp M, Psoter KJ, Balasubramanian A, et al. Heterogeneity of lung function phenotypes in sarcoidosis: role of race and sex differences. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2023; 20: 30–37. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202204-328OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baughman RP, Lower E. D. Geraint James Lecture: The sarcoidosis saga: what insights from the past will guide us in the future. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2023; 40: e2023057. doi: 10.36141/svdld.v40i4.15282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baughman RP, Drent M, Kavuru M, et al. Infliximab therapy in patients with chronic sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174: 795–802. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-402OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vorselaars AD, Crommelin HA, Deneer VH, et al. Effectiveness of infliximab in refractory FDG PET-positive sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 175–185. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00227014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schimmelpennink MC, Vorselaars ADM, van Beek FT, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab biosimilar Inflectra. Respir Med 2018; 138S: S7–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottlieb JE, Israel HL, Steiner RM, et al. Outcome in sarcoidosis. The relationship of relapse to corticosteroid therapy. Chest 1997; 111: 623–631. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.3.623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunninghake GW, Gilbert S, Pueringer R, et al. Outcome of the treatment for sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994; 149: 893–898. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.4.8143052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Y, Wang H, Xu Q, et al. Risk factors of relapse in pulmonary sarcoidosis treated with corticosteroids. Clin Rheumatol 2019; 38: 1993–1999. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04507-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baughman RP, Judson MA. Relapses of sarcoidosis: what are they and can we predict who will get them? Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 337–339. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ClinicalTrials.Gov . Efficacy and Safety of Intravenous Efzofitimod in Patients With Pulmonary Sarcoidosis. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Date last accessed: 25 June 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT05415137

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00536-2024.SUPPLEMENT (603.5KB, pdf)