ABSTRACT

The role of farmed animals in the viral spillover from wild animals to humans is of growing importance. Between July and September of 2023 infectious disease outbreaks were reported on six Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus) farms in Shandong and Liaoning provinces, China, which lasted for 2–3 months and resulted in tens to hundreds of fatalities per farm. Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus (SFTSV) was identified in tissue/organ and swab samples from all the 13 foxes collected from these farms. These animals exhibited loss of appetite and weight loss, finally resulting in death. In autopsy and histopathology, prominently enlarged spleens and extensive multi-organ hemorrhage were observed, respectively, indicating severe systemic effects. Viral loads were detected in various tissues/organs, including brains from 9 of the 10 foxes. SFTSV was also detected in serum, anal swabs, as well as in environmental samples, including residual food in troughs used by dying foxes in follow-up studies at two farms. The 13 newly sequenced SFTSV genomes shared >99.43% nucleotide identity with human strains from China. Phylogenetic analyses showed that the 13 sequences belonged to three genotypes, and that two sequences from Liaoning were genomic reassortants, indicative of multiple sources and introduction events. This study provides the first evidence of SFTSV infection, multi-tissue tropism, and pathogenicity in farmed foxes, representing an expanded virus host range. However, the widespread circulation of different genotypes of SFTSV in farmed animals from different provinces and the diverse transmission routes, highlight its increasing and noticeable public health risk in China.

KEYWORDS: Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome viruses, disease outbreak, Arctic fox, fur farms, phylogenetic analysis

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is an emerging fatal viral illness that affects both people and animals. The clinical signs and symptoms of SFTS include fever, respiratory, gastrointestinal, hemorrhagic, neurological presentations, and even death [1]. Since 2009, sporadic outbreaks of SFTS have been reported in China, South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and Thailand [2–6]. The latest data revealed that the reported incidence of SFTS in China rose during the period 2010 to 2021, resulting in over 1.87 cases per million in 2021 and with a case fatality rate ranging from 5.07% to 6.17% [7]. It has been estimated that ∼0.25 billion people reside in high-risk areas in China where the model-predicted probability of SFTS virus (SFTSV) presence exceeds 50% [8]. However, as SFTS is not a notifiable disease in China and elsewhere, the real disease burden of SFTS remains obscure and has been likely underestimated.

The causative agent, SFTSV, belongs to the species Bandavirus dabieense (formerly known as Dabie bandavirus), genus Bandavirus, and family Phenuiviridae [9]. It possesses a segmented genome of three negative-sense, single-stranded RNAs that vary in length from 1746 to 6368 nucleotides [10,11]. SFTSV has been reported to have an extremely broad host range, and has been identified in domestic animals and wild animals [12], including bovines, goats, dogs, deer, hedgehogs, cats, cheetahs [13], rodents, weasels [14], raccoons [15], and mink [16]. SFTSV is primarily transmitted to humans and animals through tick bites, but can also be spread by contact with contaminated blood or body fluids [17,18]. Limited human-to-human [19], animal-to-human [20,21], and animal-to-animal [22] transmissions during SFTSV outbreaks have also been reported. The continually expanding host range and diverse transmission routes of SFTSV make it a clear threat to public and animal health.

Foxes can harbour and spread a number of viral pathogens (such as rabies virus, canine distemper virus, parvoviruses, adenoviruses, circoviruses, and flaviviruses) [23], and also have contact with vector species such as mosquitoes and ticks. As the largest producer of fur-bearing animals worldwide, China accounts for more than half of the global production of fur. Currently, there are approximately 3.44 million farmed foxes in China [24], predominantly kept in cage systems and commonly feeding on raw foods such as fish meat and poultry by-products. Of note, the close contact between farmed foxes and farmers could facilitate the viral spillover from foxes to humans.

From 1 July to 30 September 2023, suspected infectious disease outbreaks were reported on six Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus) farms in Shandong and Liaoning provinces, China. As of 26 September 2023, the outbreaks had resulted in the deaths of tens to hundreds of Arctic foxes on each farm. In this study, we describe the pathological examination, etiological investigation, and phylogenetic characterization of SFTSV sampled from 13 dead foxes from these six farms.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

From July 2023, suspected infectious disease outbreaks were reported on six Arctic fox farms in Shandong province (farms 1 and 3 from Yantai, farms 2 and 5 from Weihai, and farm 4 from Weifang) and Liaoning province (farm 6 from Dalian), China. The diseased foxes exhibited symptoms such as decreased appetite, green or black feces, lethargy, runny nose, weight loss, and death within two to three days after the onset of symptoms.

To determine the causative agent, 13 dead foxes (denoted SD01–SD11, DL01-DL02) were collected from these farms from 26 September to 13 November 2023. Tissue/organ samples including heart, liver, spleen, lungs, trachea, kidneys, brain, turbinates, intestines, bladder, and pancreas were collected for pathological examination and molecular diagnostics. Among these, SD01, SD02, and SD03 from farm 1 showed symptoms on September 24 and died on September 26, while SD04, SD05, and SD06 from farm 2 showed symptoms on September 25 and died on September 26. We then conducted follow-up sampling on farms 1 and 2 on October 7 and 8, respectively, with 34 serum, swab, and fecal samples taken from dying foxes on the farms, as well as 16 environmental samples, collected for pathogen-targeted diagnosis.

Sample pretreatment and RNA extraction

The tissue/organ, swab, fecal and environmental samples collected were pre-treated, including homogenization with grinding beads in sterile PBS (10% weight/volume), followed by centrifugation at 2500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Total RNA was extracted from the supernatants of tissue/organ, swab, fecal and environmental samples, as well as the serum samples, using RNAiso Plus reagent (TAKARA Biotech Corporation, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Metatranscriptomic sequencing and virus discovery

RNA samples extracted from the major tissues/organs of the 13 dead foxes were merged into 13 libraries, each containing heart, liver, spleen, lung, trachea, kidney, and brain tissues from one fox. The libraries were sequenced using a metatranscriptomic sequencing protocol [25]. RNA quality was assessed using the RNA 6000 Nano Kit and the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, USA). Paired-end (150 bp) total RNA sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Beijing Novogene Co., Ltd). Approximately 10 Gb of raw sequencing data was obtained for each library.

Raw sequencing reads from each library were adaptor-trimmed and quality-controlled using the Fastp program as described previously [26]. The remaining reads were subjected to de novo genome assembly using the Trinity program [27]. The assembled contigs were annotated against the nucleotide (nt) database and non-redundant (nr) protein databases (downloaded on 2 February 2022) using Blastn and Diamond Blastx searches [28], respectively.

As the assembled contigs revealed the presence of SFTSV in all the 13 libraries, the reads were mapped directly to the SFTSV reference genomes using Bowtie2 [29], and consensus genomes were obtained using Geneious (version 11.1.5) (https://www.geneious.com). The coverage and depth of the assembled genomes were calculated with SAMtools v1.10 [30] based on the SAM files from Bowtie2. The cytochrome oxidase I (COI) gene was assembled from the 13 sequencing libraries and used to identify the fox species. To further confirm the viral sequences, overlapping primers were designed based on the assembled sequences of SFTSV and used for Sanger sequencing to amplify viral genome sequences (Supplementary Table 1).

Targeted testing

To determine the viral titre of SFTSV in individual tissues/organs pooled into the positive libraries, real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) was performed using the Taqman One-Step RT–PCR Master Mix reagents (ThermoFisher), with specific primers (5′-GGGTCCCTGAAGGAGTTGTAAA-3′ and 5′-TGCCTTCACCAAGACTATCAATGT-3′) and probe (5′-FAM-TTCTGTCTTGCTGGCTCCGCGC-BHQ3′) [31].

Histopathological observations

Fragments of the virus positive tissues/organs (including heart, liver, spleen, lungs, trachea, kidneys, and brain) of the dead foxes, were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. The fixed samples were embedded in paraffin-wax, sectioned at 4μm-thick, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to observe macroscopic lesions.

Phylogenetic analyses

To reveal the evolutionary relationships of the SFTSV associated with the fox farm outbreaks to those viruses sampled previously, complete consensus sequences comprising the viral L, M, and S gene segments were subjected to phylogenetic analysis. Reference genomes of representative SFTSV strains available from NCBI/GenBank were retrieved using Blastn on 26 April 2024, and compiled into a data set with the SFTSV sequences generated in the present study. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using MAFFT v7.490. Phylogenetic analysis of the aligned L, M, and S data sets was conducted using RaxML v8.1.6 [32], employing the GTRGAMMA nucleotide substitution model with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Phylogenetic trees were visualized using FigTree v1.4.3. The L, M, and S gene segment clades of SFTSV were defined in parallel using the two available genotyping systems (C1–C6, A–F) designated in a previous study [33–36].

Results

Initial SFTSV outbreak information

Between 1 July 2023 and 30 September 2023, a total of six farms (farms 1 to 6) in Yantai, Weihai, and Weifang cities in Shandong province, and Dalian city in Liaoning province, China, reported suspected outbreaks of SFTSV (Table 1). These farms were geographically distant. Arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus) were bred on all the farms, including blue and white Arctic foxes based on their fur colour. The size of these farms ranged from 700 to 11,000 foxes.

Table 1.

Summary of the epidemiological information of each farm in Shandong and Liaoning provinces, China, 2023.

| Farm ID | Farm information | Outbreak information | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Species of breeding foxes | Stages of breeding foxes | No. breeding foxes | No. (%) symptomatic foxes | Outbreak duration (No. days) | Clinical signs and symptoms of the sick foxes | Disease transmission | |

| Farm 1 | Yantai, Shandong Province | Blue and white Arctic foxes | Juveniles | ∼3400 | ∼900 (26.5) | Aug 28a–Nov 05b (70 days) | Decreased appetite, green poop, death | Yesc |

| Farm 2 | Weihai, Shandong Province | Blue and white Arctic foxes | Juveniles | ∼1400 | ∼450 (32.1) | Sep 01–Oct 15 (44 days) | Decreased appetite, death | Yes |

| Farm 3 | Yantai, Shandong Province | White Arctic foxes | Juveniles | ∼11000 | ∼400 (3.64) | Sep 15–Nov 12 (58 days) | Decreased appetite, death | Yes |

| Farm 4 | Weifang, Shandong Province | Blue Arctic foxes | Juveniles | ∼700 | ∼55 (7.86) | Jul 01–Nov 01 (123 days) | Decreased appetite, lethargy, runny nose, green poop, death | Yes |

| Farm 5 | Weihai, Shandong Province | Blue Arctic foxes | Juveniles | ∼3400 | ∼1000 (29.4) | Sep 30–Nov 10 (41 days) | Decreased appetite, death | Yes |

| Farm 6 | Dalian, Liaoning Province | Blue Arctic foxes | Juveniles | ∼1400 | ∼200 (14.3) | Aug 07–Nov 15 (69 days) | Decreased appetite, black poop, death | Yes |

Date of symptom onset of index case.

Date of endpoint; the time when similar symptoms were no longer observed in foxes raised on the farms.

Transmission among foxes.

The affected foxes exhibited generic symptoms, including decreased appetite, lethargy, weight loss, finally leading to death. The outbreaks lasted for 2–3 months and similar cases continued to occur in foxes housed in the same cage and in cages adjacent to those hosting symptomatic animals (Table 1). The number of sick foxes ranged from 55 to 1000, representing 3.64% to 32.1% of the total fox population on the farms.

Identification of SFTSV in dead foxes

In the original case study, a total of 131 tissue/organ samples including heart, liver, spleen, lung, trachea, kidney, brain, nasal turbinate, intestine, bladder, and pancreas, were collected from the 13 dead foxes from farms 1 to 6 between 26 September and 5 November 2023 (Supplementary Table 2). We performed metatranscriptomic sequencing of 87 tissues/organs to identify the causative agent. The tissues/organs from a single fox were pooled into 13 RNA sequencing libraries. Overall, total RNA sequencing generated more than 30,042,032 paired-end reads in each library, which were then de novo assembled for virus identification. SFTSV was identified in all the 13 pools and the relative abundance of SFTSV ranged from 76 to 1,202,010 reads (Table 2). No other potential pathogenic genes were detected. Thirteen SFTSV genome sequences were successfully generated and validated by Sanger sequencing (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). The COI gene sequences of the 13 libraries were identical and shared the highest nucleotide identity (98.80% to 99.70%) with the Arctic fox COI gene (Table 2). The raw sequencing data, all viral genomes, and the COI gene sequences generated in this study have been deposited into China National Microbiology Data Center (NMDC; accession No. NMDC40065198 – NMDC40065210, NMDCN0005EF1 – NMDCN0005EH9, NMDCN0005EFA – NMDCN0005EFV, NMDCN0005EHA – NMDCN0005EHB, NMDCN0005EG0, NMDCN0005EH0 NMDCN0005EGA, and NMDCN0005EGV; Supplementary Table 3).

Table 2.

Information on the 13 SFTSV-positive samples from the farmed foxes, China.

| Sample | Farm ID | Case information | Contig and sequence information | Species identification using the COI gene | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Date of symptom onset | Date of death | Raw reads (PE) | Mapped readsd | Lengthe | Mapped readsf | Length | Identityg | ||

| SD01 | Farm 1 | Blue Arctic fox | Sep 24 | Sep 26 | 80,282,118a | 265,650/144,048/71,590 | 6370/3379/1744 | 53,382 | 647 | 99.70% |

| SD02 | Farm 1 | Blue Arctic fox | Sep 24 | Sep 26 | 86,578,556a | 451,334/225,868/131,304 | 6374/3380/1746 | 66,978 | 647 | 99.70% |

| SD03 | Farm 1 | White Arctic fox | Sep 24 | Sep 26 | 65,946,936a | 1,202,010/434,642/315,478 | 6368/3383/1744 | 46,322 | 647 | 99.70% |

| SD04 | Farm 2 | Blue Arctic fox | Sep 25 | Sep 26 | 62,641,462a | 96,340/54,750/23,114 | 6371/3378/1744 | 35,120 | 647 | 99.70% |

| SD05 | Farm 2 | White Arctic fox | Sep 25 | Sep 26 | 62,285,214a | 8704/5800/2234 | 6368/3378/1744 | 18,004 | 647 | 99.70% |

| SD06 | Farm 2 | Blue Arctic fox | Sep 25 | Sep 26 | 54,042,830b | 212,156/115,886/50,016 | 6373/3392/1744 | 51,902 | 647 | 99.70% |

| SD07 | Farm 3 | White Arctic fox | Oct 18 | Oct 26 | 49,166,286a | 187,574/124,500/60,478 | 6354/3357/1730 | 34,100 | 647 | 99.70% |

| SD08 | Farm 3 | White Arctic fox | Oct 18 | Oct 26 | 55,085,056a | 18,810/11,652/5938 | 6346/3355/1725 | 39,460 | 647 | 99.70% |

| SD09 | Farm 4 | Blue Arctic fox | Oct 22 | Oct 26 | 30,042,032a | 182/128/76 | 5635/3000/1532 | 84 | 645 | 98.80% |

| SD10 | Farm 5 | Blue Arctic fox | Oct 24 | Oct 26 | 54,210,892c | 694,394/299,232/183,984 | 6355/3369/1728 | 43,152 | 647 | 99.70% |

| SD11 | Farm 5 | Blue Arctic fox | Oct 24 | Oct 26 | 69,988,104c | 346,322/137,286/102,190 | 6360/3369/1736 | 33,184 | 647 | 99.70% |

| DL01 | Farm 6 | Blue Arctic fox | Nov 5 | Nov 13 | 33,441,522a | 1644/616/652 | 6319/3282/1701 | 100 | 647 | 99.70% |

| DL02 | Farm 6 | Blue Arctic fox | Nov 5 | Nov 13 | 30,613,378a | 942/450/398 | 6308/3305/1700 | 218 | 647 | 99.70% |

Note: The RNA libraries used for metatranscriptome sequencing included tissues from one fox.

Seven tissues (heart, liver, spleen, lung, trachea, kidney, and brain).

Five tissues (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney).

Six tissues (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and brain).

Number of reads mapped to the L segment/M segment/S segment of the SFTSV reference genome sequence from the nr databases.

Length of sequences of the L segment/M segment/S segment of the SFTSV genome sequenced in this study.

Number of sequence reads mapped to the COI gene of the Vulpes lagopus voucher ROM 97263 (Accession number: JF443550.1).

Pairwise sequence identity of the COI gene with those of the Vulpes lagopus voucher ROM 97263 (Accession number: JF443550.1).

The 13 complete SFTSV genomes shared >95.23% nucleotide identities in the L, M, and S gene segments with each other (Supplementary Table 4). The viral sequences from animals sampled on the same farm shared >99.84% nucleotide identity. In addition, they shared >99.43% nucleotide identities with their most closely related SFTSV sequences available in GenBank in all the three gene segments (Supplementary Table 3). A Blastn search revealed that the L gene sequences of human sequences AHZ/2011, SD2011-040, HB2016-003, and LN2011-xq from China, the M gene sequences of AHZ-2019-WXP, JS4/2010, HB2016-003, and LN2013-035, and the S gene sequences of Henan-74/2018, SD2011-040, SDPLP01/2011, and LN2012-41 available from GenBank, shared the highest nucleotide identities with the 13 novel SFTSV strains.

We further investigated the tissue tropism of SFTSV in farmed foxes. Real-time RT–PCR testing revealed that, among the tissue samples collected in the case study, all the 120 tissue/organ samples from 12 deceased foxes (SD01 to SD08, SD10, SD11, DL01, and DL02) tested positive for SFTSV, including 9 brain samples (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2). In contrast, only 1 of the 11 tissue samples (trachea) collected from fox SD09 from farm 4 tested positive for SFTSV. All 6 oral swabs and 6 anal swabs collected from dead foxes from farms 1 and 2 tested positive for SFTSV (Table 3).

Table 3.

SFTSV testing by specimen type using real-time RT-PCR in case studies and follow-up studies on six fox farms.

| Farm ID | Case study | Follow-up study | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of dead foxes sampleda | No. of positive / no. of tested samples (%) collected from dead foxes | No. positive / no. tested samples (%) collected from dying foxes on farmsc | No. positive / no. tested environmental samples (%) collected from farmsc | |||||||||

| Tissuesb | Oral swab | Anal swab | Serum | Nasal swab | Anal swab | Feces | Sink | Feedd | Tick | Residual feede | ||

| Farm 1 | 3/3 (SD01, SD02, SD03) | 10/10 (100), 11/11 (100), 11/11 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 5/5 (100) | 6/6 (100) | NA | 5/5 (100) | 0/1 (0) | 0/4 (0) | 0/1 (0) | 3/3 (100) |

| Farm 2 | 3/3 (SD04, SD05, SD06) | 11/11 (100), 11/11 (100), 9/9 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 4/4 (100) | 4/4 (100) | 2/2 (100) | 8/8 (100) | 0/1 (0) | 0/4 (0) | NA | 2/2 (100) |

| Farm 3 | 2/2 (SD07, SD08) | 11/11 (100), 11/11 (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Farm 4 | 1/1 (SD09) | 1/11 (9.01) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Farm 5 | 2/2 (SD10, SD11) | 9/9 (100), 9/9 (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Farm 6 | 2/2 (DL01, DL02) | 8/8 (100), 9/9 (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

These dead foxes usually exhibited the clinical signs and symptoms listed in Table 1.

Tissues sampled from the SFTSV infected foxes, including heart, liver, spleen, lung, trachea, kidney, brain, nasal turbinate, intestine, bladder, and pancreas as listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Serums, swabs, and feces from dying foxes, and environmental specimens in follow-up study from farm 1 were sampled on Oct 7 2023, and those from farm 2 on Oct 8 2023.

Samples from the stored feed in the warehouse.

Samples from the residual feed in troughs used by the dying foxes; “NA,” not applicable.

Confirmation of SFTSV in follow-up studies

On 7 and 8 October 2023, follow-up sampling was conducted on farms 1 and 2. A total of 34 samples were collected from dying foxes, including 9 serum samples, 10 nasal swab samples, 2 oral swab samples, and 13 fecal samples. Real-time RT–PCR testing showed that all these samples (100%) tested positive for SFTSV (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 5). In addition, 16 environmental samples were collected from the farms, including 2 sink samples, 8 samples from the stored feed in warehouse, one tick, and 5 samples from the residual feed in troughs used by the dying foxes. Only the residual food from troughs tested positive for SFTSV, while all other environmental samples tested negative for SFTSV, including the tick found at farm 1 (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 5).

Gross lesions, and histopathological lesions in dead foxes

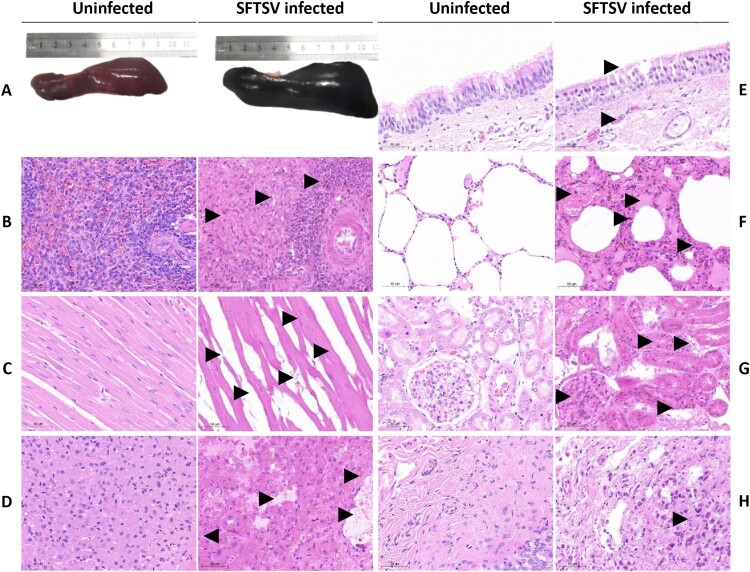

A typical enlarged purple-black spleen was observed in all the 13 foxes examined (Figure 1A). However, no obvious gross lesions were found in other tissues of the SFTSV-infected foxes. Histopathologically, hemorrhage was observed in multiple organs. Throughout the spleen, there was extensive infiltration of red blood cells in the white pulp, with a decreased number of lymphocytes (Figure 1B). The remaining lymphocytes were surrounded by a large number of red blood cells, with hemosiderin deposition. Within the heart, the volume of cardiomyocyte nuclei became smaller, with narrowed myocardial fibre and wider intercellular spaces (Figure 1C). Broken muscle fibres and a minimal hemosiderin deposition could be found in the heart. The central veins and hepatic sinusoids in the liver were dilated and congestive, with hemosiderin deposition (Figure 1D). Within the trachea mucosa, there was detachment of epithelial cells, with congestion of the submucosal capillaries (Figure 1E). Within the lung, the alveolar septa became wider (Figure 1F). There was congestion of small pulmonary veins and capillaries in the alveolar walls, filled with red blood cells and hemosiderin deposition. Abundant serous fluid was present in the alveolar spaces. Within the kidney, glomeruli were enlarged (Figure 1G). There was degeneration and detachment in the tubular epithelial cells. Tubular lumens became narrower, with numerous protein casts and hemosiderin deposition. In addition, there was severe sloughing of the bladder mucosal epithelium (Figure 1H).

Figure 1.

Gross and hispathological lesions in SFTSV-infected foxes and uninfected control foxes. (A) Compared to control foxes, the spleen in SFTSV-infected fox is visibly enlarged. (B–H) Pathological changes in spleen, heart, liver, trachea, lung, kidney, and bladder from SFTSV-infected foxes are labelled with arrows: (B) red blood cells infiltrate the white pulp of the spleen, with fewer lymphocytes surrounded by hemosiderin deposits; (C) the heart shows reduced cardiomyocyte nuclei size, thinner myocardial fibres, and minor fibre breakage; (D) liver central veins are dilated and congested with hemosiderin deposition; (E) the trachea exhibits epithelial detachment and submucosal capillary congestion; (F) lungs display widened alveolar septa and fluid-filled alveolar spaces; (G) enlarged kidney glomeruli with tubular degeneration; (H) severe sloughing of the bladder mucosal epithelium. Panels B–H, original magnification ×40.

Genomic evolution of circulating SFTSV

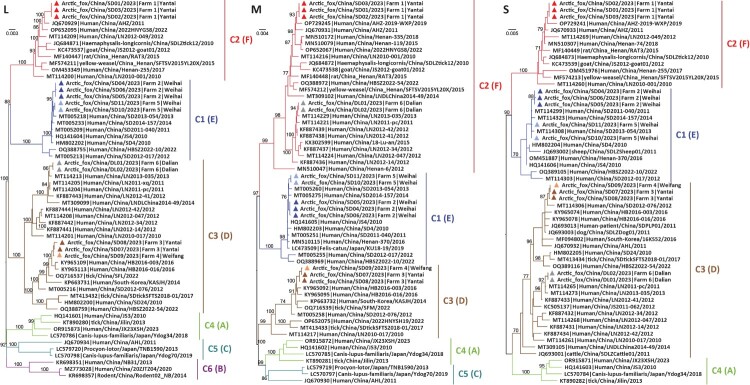

To better understand SFTSV evolution, we performed phylogenetic analyses of 57 representative SFTSV L gene segment sequences, 58 M sequences, and 57 S sequences, including the 13 SFTSV genome sequences described in the current study (Figure 2). According to the nomenclature of the two available genotyping systems [33–36], our phylogenetic analyses revealed that the Chinese SFTSV strains fell into multiple clades: genotypes C1–C6 (equivalent to genotypes A–F in the other classification scheme) for the L gene, C1–C5 (equivalent to genotypes A, C, D, E, and F) for the M gene, and C1–C4 (equivalent to genotypes A, D, E, and F) for the S gene (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of 13 SFTSV genomes from the farm outbreaks and representative sequences available from GenBank. Branch colours in the L, M, and S gene segment phylogenetic trees represent SFTSV clade: denoted C1–C6 (equivalent to genotypes A∼F in another classification scheme). The red, blue, brown, light brown, light blue, and grey triangles denote the 13 SFTSV strains identified from six farms in this study. The trees are mid-point rooted and the scale bars represent the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

The 13 sequences identified from the deceased foxes in 2023 fell into three clades in the L, M, and S gene segment trees: C1, C2, and C3 (equivalent to genotypes E, F, and D; Figure 2). Specifically, in all three gene segment phylogenies sequences SD04, SD05, SD06, SD10, and SD11 from farms 2 and 5 in Weihai city, Shandong province belonged to clade C1, sequences SD01, SD02, and SD03 from farm 1 in Yantai city, Shandong province belonged to clade C2, while sequences SD07 and SD08 from farm 3 in Yantai city, Shandong province, and SD09 from farm 4 in Weifang city, Shandong province belonged to clade C3. In contrast, although sequences DL01 and DL02 from farm 6 in Liaoning province fell within clade C3 in the L and S gene trees, their M gene sequences belonged to clade C2, therefore indicative of genomic reassortment. Of note, the same reassortment event was observed in eight human SFTSV sequences (LN2011-pc, LN2012-14, LN2012-34, LN2013-035, LN2012-41, LN2012-42, LN2012-047, and LNDLChina2014-49) sampled from Liaoning province between 2011 and 2014, and one human strain (HBSZ2022-54/Suizhou/2022) sampled from Hubei province in 2022.

Discussion

SFTS is a viral disease mainly transmitted by ticks, first identified in China in 2009 and subsequently reported in several East Asian countries and recently in Vietnam, and Pakistan [2–6,37]. The causative agent, SFTSV, is primarily transmitted by Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks [38]. Human infection with SFTSV manifests as fever, thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), and leukopenia (low white blood cell count), and may progress to multi-organ failure, particularly in elderly patients [39], leading to a high mortality rate. The incidence of SFTS in China has been steadily rising, with significant regional outbreaks in recent years. While the epidemiological characteristics of SFTS in humans have been studied, its circulation in livestock and wildlife, as well as the potential for sustained cross-species transmission to humans, remains poorly understood.

We performed an etiological investigation of concurrent infectious disease outbreaks on six Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus) farms in Shandong and Liaoning provinces, China, from July to September of 2023. The outbreaks lasted for 2–3 months, and resulted in the death of tens to hundreds of foxes per farm. Variation in outbreak spread and severity across these six farms may be attributed to several factors, including: (1) differing collection dates such that the disease process varied among breeding plants; (2) farm management practices (e.g. providing sufficient shade, maintaining clean feed and water); (3) biosecurity protocols (e.g. limiting access for contaminated vehicles, timely quarantining sick foxes, and eliminating carrier foxes) [40,41]; (4) population density (e.g. preventing overcrowded conditions of foxes) [40,42]; and (5) the effectiveness of health monitoring systems at each farm [41]. Continuous pathogen monitoring from the beginning of future infectious disease outbreaks, combined with rigorous multiple regression analysis, would enable more accurate assessment of fatality rates, identification of the factors responsible for the outbreaks, and the measurement of disease severity.

Both metatranscriptomic and molecular detection of the tissues sampled from the six farms across Yantai, Weihai, and Weifang cities in Shandong province, as well as Dalian city in Liaoning province, revealed the presence of SFTSV. Similar to the previous identification of SFTSV in goats, pigs, rodents, cheetah, raccoons, and mink [12,13,15], this study broadened our understanding of the host range of SFTSV and emphasized the potential importance of these animal hosts in the SFTSV ecosystem [43]. Although further validation through animal studies are necessary to confirm SFTSV as the direct causation of these outbreaks, our study highlights the wide prevalence of SFTSV infection in fox farming industry in Shandong and Liaoning, and its potential threat to occupational population in these regions and elsewhere.

The 13 infected Arctic foxes in this study exhibited SFTS-like symptoms, including decreased appetite, lethargy, and weight loss, eventually leading to death. Similarly, fatal SFTSV-infections have also been reported in cats [44], cheetahs [13], and mink [45]. However, this severe presentation contrasts with the typically mild or subclinical infections observed in other hosts, such as goats [46] and raccoons [15], which generally exhibit limited viremia and no obvious clinical signs. Hence, our data suggest a higher susceptibility or a more intense immune response to SFTSV in foxes. Gross pathological comparisons with cheetahs [13] and mink [45] revealed spleen enlargement in infected foxes, although no gastrointestinal tract damage was observed. Histopathological results showed extensive hemorrhages and substantial iron-hemoglobin deposits in the spleen, heart, liver, lungs, and kidneys. The white pulp of the spleen exhibited significant red blood cell infiltration and lymphocyte depletion, with degeneration in cardiomyocytes, lung tissue, and renal tubules. These findings indicate a severe multisystem impact of SFTSV infection in foxes. However, lesions observed in other hosts, such as necrotic foci in the spleen’s follicular zone in infected cats [47] and hepatocellular necrosis in mink [45], were absent in foxes. Further experimental studies are necessary to explore the mechanisms shaping these host-specific variations in SFTSV clinical symptoms, autopsy and pathological changes, such as host immune responses, or viral virulence.

Of note, SFTSV RNA was present in multiple organs of the infected foxes, including the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, brain, and intestine [14,48]. In particular, spleen was found to be the major target organ, which exhibited especially high viral loads. This is consistent with earlier observations in animal models (e.g. mice), where high viral loads in the spleen were typically associated with severe pathological changes [49]. Further, the neurotropism of SFTSV was previously reported in an aged ferret model [48], and SFTSV RNA was also found in the brain in 9 of the 10 dead foxes in this study. However, the symptoms of neurotropism of SFTSV in the infected foxes remain to be determined. Viral RNA was also detected in tissues such as the trachea, nasal turbinate, bladder, and pancreas, which have not been previously reported. Furthermore, SFTSV nucleic acid was positive in oral swabs and serum in the case studies and the follow-up studies. These results suggest that foxes could be potent hosts for SFTSV, which is crucial for assessing the potential of the virus to spread among wildlife populations.

Previously, high levels of SFTSV RNA were also found in the serum, saliva, rectal swabs, and urine of infected cats [20]. During the second round of sampling at farms 1 and 2, we collected the food residue from the troughs of the dying foxes and the stored food in the farm warehouse. Interestingly, food residue in the troughs tested positive for SFTSV RNA, while the stored food from the warehouse tested negative. Furthermore, we detected the virus in serum, oral swabs, anal swabs, nasal swabs, and environmental samples. This suggests that SFTSV might be potentially transmitted through the oral route.

The source of the SFTSV infection in the diseased foxes is unclear. Given the outdoor farming setting, several known wild animal hosts of SFTSV, such as ticks [33,50] and rodents [51], could be present in fox farms. However, only one tick was found at farm 1, and no ticks were found in other farms. In the future, larger sample sizes from multiple species within the same farm should be collected to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the SFTSV transmission patterns among wild animal populations [52]. Additionally, farmed animals such as mink, are sometimes raised alongside foxes in the same farms [16,45,53]. Notably, on 21 October 2023, two SFTS-like patients were identified in a mink farm in Weihai city, Shandong province, China [54]. As such, the detection of SFTSV in farmed animals has important implications for both animal and human health. Moreover, the high nucleotide identity (>99.43%) between the 13 newly sequenced SFTSV genomes from foxes and the human sequences from China highlights the potential transmission risk to humans, particularly those in close contact with the infected foxes such as breeding personnel.

Our phylogenetic analysis revealed that the SFTSV sequences in this study primarily clustered within Chinese-associated lineages and were genetically distinct from those sequences sampled in Japan [55]. This indicates that the current SFTSV variants in foxes are regionally endemic within China. Of note, the 13 SFTSV genomes in this study belonged to multiple clades (i.e. C1, C2, and C3). Among these sequences, SD01, SD02, SD03 from farm 1 in Yantai city, Shandong province, and SD07 and SD08 from farm 3 in Yantai city, Shandong province, were located into two different branches (i.e. genotypes) in the L, M, and S gene trees – C2 and C3. Hence, there were multiple introductions of SFTSV into these fox farms which might reflect geographical and ecological factors specific to the individual fox farms. In contrast, sequences SD04, SD05, and SD06 from farm 2, as well as SD10 and SD11 from farm 5 in Weihai city, Shandong province, represent the same SFTSV genotype, with their L, M, and S genes falling within the same evolutionary lineage – C1. The identification of the same SFTSV genotype across fox farms suggests that it is the genotype most commonly found in tick populations, although the potential movement of the breeding foxes infected with SFTSV and other hosts (e.g. cats and dogs) cannot be excluded. In turn, the identification of reassortment events involving the M gene segments of sequences DL01 and DL02 underscores the potential for SFTSV to change its genome constellation, which could potentially alter viral pathogenicity or transmissibility [12,56]. Hence, these findings emphasize the importance of the co-circulation of multiple SFTSV genotypes such that ongoing genomic surveillance is needed to monitor the emergence of novel variants that may pose a greater risk to public health.

In summary, this study describes concurrent SFTSV outbreaks in multiple fox farms in Shandong and Liaoning provinces, expanding our understanding of viral host range and revealing the complex transmission dynamics of SFTSV. SFTSV RNA was detected in many different tissues/organs in the infected foxes, and our results highlight the potential role of wildlife in the spread of emerging infectious diseases [57]. Considering the close contact between humans and animals in the farms, enhancing surveillance and biosecurity measures to mitigate the risk of zoonotic diseases in fur-producing industry is of clear importance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Qi Liu, Shan Li, Mengyuan Cao, Shuqi Liu, and Wei Zhu for their assistance with sample collection and laboratory testing, Yunxiao Wang for metatranscriptomic sequencing, Tao Hu for genomic data processing, and Weijia Xing for epidemiological data processing in this manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China [grant number 2023YFC2307503]. J.L. was supported by the Taishan Scholars Programme of Shandong Province [grant number tsqn202211217] and the National High-Level Talents Special Support Plan – “Ten Thousand Plan” – Young Top – Notch Talent Support Program. J.W. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 32373001] and the Hebei Natural Science Foundation [grant number C2021204105]. H.Z. was supported by the Taishan Scholars Programme of Shandong Province [grant number tsqn202306264]. C.L. was supported by the Youth Innovation Team of Shandong Higher Education Institution [grant number 2021KJ064]. W.S. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China for Distinguished Young Scholars [grant number 32325003].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethics statement

The procedures for sampling were reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences (No. W201905250136). All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

References

- 1.Li H, Lu QB, Xing B, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of laboratory-diagnosed severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in China, 2011–17: a prospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(10):1127–1137. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30293-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu XJ, Liang MF, Zhang SY, et al. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):1523–1532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim KH, Yi J, Kim G, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, South Korea, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(11):1892–1894. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.130792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi T, Maeda K, Suzuki T, et al. The first identification and retrospective study of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Japan. J Infect Diseases. 2014;209(6):816–827. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishijima K, Phichitraslip T, Naimon N, et al. High seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus infection among the dog population in Thailand. Viruses. 2023;15(12):2403. doi: 10.3390/v15122403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran XC, Yun Y, Van An L, et al. Endemic severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(5):1029–1031. doi: 10.3201/eid2505.181463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang XX, Du SS, Li AQ, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in China, 2018-2021. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2024;45(1):112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao GP, Wang YX, Fan ZW, et al. Mapping ticks and tick-borne pathogens in China. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1075. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21375-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). ICTV 2023 Master Species List (MSL39). 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 4]. Available from: https://ictv.global/msl

- 10.Lee SY, Kang JG, Jeong HS, et al. Complete genome sequences of two severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus strains isolated from a Human and a dog in the Republic of Korea. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2019;8(31). doi: 10.1128/MRA.01695-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Q, He B, Huang SY, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, an emerging tick-borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(8):763–772. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70718-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casel MA, Park SJ, Choi YK.. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus: emerging novel phlebovirus and their control strategy. Exp Mol Med. 2021;53(5):713–722. doi: 10.1038/s12276-021-00610-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuno K, Nonoue N, Noda A, et al. Fatal tickborne phlebovirus infection in captive cheetahs, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(9):1726–1729. doi: 10.3201/eid2409.171667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang XY, Du YH, Wang HF, et al. Prevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in animals in Henan Province, China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s40249-019-0569-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tatemoto K, Ishijima K, Kuroda Y, et al. Roles of raccoons in the transmission cycle of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. J Vet Med Sci. 2022;84(7):982–991. doi: 10.1292/jvms.22-0236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Yang M, Zhou H, et al. Outbreak of natural severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus infection in farmed minks, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30(6):1299–1301. doi: 10.3201/eid3006.240283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim WY, Choi W, Park SW, et al. Nosocomial transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Korea. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(11):1681–1683. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang X, Wu W, Wang H, et al. Human-to-human transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome bunyavirus through contact with infectious blood. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(5):736–739. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung IY, Choi W, Kim J, et al. Nosocomial person-to-person transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(5):633e1–633e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamanaka A, Kirino Y, Fujimoto S, et al. Direct transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus from domestic cat to veterinary personnel. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(12):2994–2998. doi: 10.3201/eid2612.191513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kida K, Matsuoka Y, Shimoda T, et al. A case of cat-to-human transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2019;72(5):356–358. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2018.526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mekata H, Umeki K, Yamada K, et al. Nosocomial severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in companion animals, Japan, 2022. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29(3):614–617. doi: 10.3201/eid2903.220720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourg M, Nobach D, Herzog S, et al. Screening red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) for possible viral causes of encephalitis. Virol J. 2016;13(1):151. doi: 10.1186/s12985-016-0608-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xinmiao L. Molecular epidemiology of enterocytozoon bieneusi and cryptosporidium in fox and Raccoon Dog [master’s thesis]. [Zhengzhou (Henan)]: Henan Agricultural University; 2022.

- 25.Xu L, Song M, Tian X, et al. Five-year longitudinal surveillance reveals the continual circulation of both alpha- and beta-coronaviruses in plateau and gansu pikas (Ochotona spp.) at Qinghai Lake, China. Emerging Microbes Infect. 2024;13(1):2392693. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2024.2392693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu T, Li J, Zhou H, et al. Bioinformatics resources for SARS-CoV-2 discovery and surveillance. Brief bioinform. 2021;22(2):631–641. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH.. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2015;12(1):59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langmead B, Salzberg SL.. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun Y, Liang M, Qu J, et al. Early diagnosis of novel SFTS bunyavirus infection by quantitative real-time RT-PCR assay. J Clin Virol. 2012;53(1):48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lv Q, Zhang H, Tian L, et al. Novel sub-lineages, recombinants and reassortants of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017;8(3):385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshikawa T, Fukushi S, Tani H, et al. Sensitive and specific PCR systems for detection of both Chinese and Japanese severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus strains and prediction of patient survival based on viral load. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(9):3325–3333. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00742-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu Y, Li S, Zhang Z, et al. Phylogeographic analysis of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus from zhoushan islands, china: Implication for transmission across the ocean. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19563. doi: 10.1038/srep19563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park D, Kim KW, Kim YI, et al. Deciphering the evolutionary landscape of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus across east asia. Virus Evol. 2024;10(1):veae054. doi: 10.1093/ve/veae054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen S, Saqib M, Khan HS, et al. Risk of infection with arboviruses in a healthy population in Pakistan based on seroprevalence. Virol Sin. 2024;39(3):369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2024.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo LM, Zhao L, Wen HL, et al. Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks as reservoir and vector of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(10):1770–1776. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.150126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li JC, Zhao J, Li H, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and treatment of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Infect Med (Beijing). 2022;1(1):40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.imj.2021.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.College of veterinary medicine. Preventing disease on the farm. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 11]. Available from: https://vetmed.wsu.edu/preventing-disease-on-the-farm/ [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mallapaty S. Fur farming a ‘viral highway’ that could spark next pandemic, say scientists. Nature. 2024;633(8030):506. doi: 10.1038/d41586-024-02871-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warwick C, Pilny A, Steedman C, et al. One health implications of fur farming. Front Ani Sci. 2023;4:1249901. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2023.1249901 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao L, Zhai S, Wen H, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus, Shandong Province, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(6):963–965. doi: 10.3201/eid1806.111345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ando T, Nabeshima T, Inoue S, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in cats and its prevalence among veterinarian staff members in Nagasaki, Japan. Viruses-Basel. 2021;13(6):1142. doi: 10.3390/v13061142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meng X, Sun J, Yao M, et al. Isolation and identification of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus from farmed mink in Shandong, China. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2024;2024:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2024/9604673 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiao Y, Qi X, Liu D, et al. Experimental and natural infections of goats with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus: evidence for ticks as viral vector. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(10):e0004092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakai Y, Kuwabara Y, Ishijima K, et al. Histopathological characterization of cases of spontaneous fatal feline severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(4):1068–1076. doi: 10.3201/eid2704.204148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park SJ, Kim YI, Park A, et al. Ferret animal model of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome phlebovirus for human lethal infection and pathogenesis. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(3):438–446. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0317-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin C, Liang M, Ning J, et al. Pathogenesis of emerging severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in C57/BL6 mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(25):10053–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120246109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wen HL, Zhao L, Zhai S, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, Shandong Province, China, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(1):1–5. doi: 10.3201/eid2001.120532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gu XL, Su WQ, Zhou CM, et al. SFTSV infection in rodents and their ectoparasitic chiggers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(8):e0010698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park SW, Song BG, Shin EH, et al. Prevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks in South Korea. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5(6):975–977. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang GS, Wang JB, Tian FL, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus infection in minks in China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017;17(8):596–598. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2017.2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li J, Wang C, Li X, et al. Direct transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus from farm-raised fur animals to workers in Weihai, China. Virol J. 2024;21(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s12985-024-02387-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshikawa T, Shimojima M, Fukushi S, et al. Phylogenetic and geographic relationships of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in China, South Korea, and Japan. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(6):889–898. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yun SM, Park SJ, Kim YI, et al. Genetic and pathogenic diversity of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) in South Korea. JCI insight. 2020;5(2):e129531. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.129531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhuang L, Sun Y, Cui XM, et al. Transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus by Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(5):868–871. doi: 10.3201/eid2405.151435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.