ABSTRACT

Background

Parasites are a major concern for profitable poultry production worldwide as they impede the health, welfare and production performance of poultry.

Objectives

The present study was designed to detect the diversity of parasitic fauna and associated factors of gastrointestinal (GI) helminths and lice in indigenous chickens.

Methods

A total of 310 indigenous chickens were collected from different villages at Gauripur and Mymensingh Sadar, Mymensingh, and Bangladesh, and various parasites were identified.

Results

Out of 310 indigenous semi‐scavenging chickens, 281 were infected with one or more species of helminths with an overall prevalence of 90.6%. The identified species of helminths were Ascaridia galli (60.6%), Heterakis gallinarum (29.0%) and Cheilospirura hamulosa (14.2%), Catatropis verrucosa (7.7%), Echinostoma revolutum (7.4%), Raillietina spp. (76.5%) and Hymenolepis spp. (5.8%). The prevalence of lice infestations was 74.2%, and identified species were Menopon gallinae (72.6%), Goniodes gigas (11.6%) and Lipeurus caponis (10.3%). Co‐infections with helminths were 65.8% and with lice were 19.4% in chickens. Univariate analysis was performed to measure the association between predictor variables and parasitic infections by considering several biotic and abiotic variables, including age, sex, flock size, farming nature, use of anthelmintic/insecticides and socio‐economic status of owners. No significant (p < 0.05) variation was found in helminth infections but large flock size (87.0%) and mixed farming nature (81.2%) were significantly associated with lice infestations in chickens.

Conclusions

Awareness related to the management system of chickens rearing need to be increased for formulating control strategy against parasitic infections in indigenous chickens in Bangladesh.

Keywords: chickens, ecto‐parasites, helminths, lice, prevalence

GI helminth and lice are highly prevalent in indigenous semi‐scavenging chickens.

Seven species of helminths were detected, and Raillietina was predominant.

Three species of lice were identified and Menopon gallinae was most abundant.

Co‐infection was observed in helminth infections and lice infestation.

Large flock size and mixed farming were significantly related with lice infestations.

1. Introduction

Bangladesh has one of the highest proportions of impoverished livestock keepers in the world. Rearing of small poultry flock (5–10 birds) by the poor and marginalized farmers is a common practice in Bangladesh. About 90% of rural farmers, especially women rear poultry for solvency that ultimately enhances the empowerment of women. Over the last few decades, the demand of poultry products for human consumption has been increasing that triggers a substantial growth of poultry production (Ola‐Fadunsin et al. 2019). Poultry industry plays a significant role in increasing the national economy in most of the countries of the world (Shifaw et al. 2021). Both ecto‐ and endo‐parasites are major concern for the sustainable growth of poultry production due to their harmful impacts on health, welfare and production performance. Nematodes, cestodes, trematodes and protozoa are important endoparasites identified from gastrointestinal (GI) tract (GIT), whereas lice, mites, fleas and ticks are important ectoparasites of indigenous chickens collected from skin and feathers (Poulsen et al. 2000; Shanta et al. 2006). Menacanthus stramineus, Menopon gallinae, Goniodes gigas, Liperus caponis, Cuclotogaster heterographus, Cnemidocoptes mutans, Cnemidocoptes pilae, Cnemidocoptes galline and Dermanyssus gallinae are common ectoparasites in indigenous chickens causing discomfort, anaemia, underweight, reduced egg production and mortality (Furgasa 2021; Shanta et al. 2006). They also play vital roles as mechanical or biological vectors in transmitting various pathogenic organisms such as viruses, bacteria and fungi (Mekuria and Gezahegn 2010; Tamiru et al. 2014). Among endoparasites, about 200 species of cestodes infect avian and mammalian hosts, including humans (Ramnath et al. 2014). In addition, Davainea, Raillietina, Hymenolepis and Choanotaenia have been reported commonly in small intestine of chickens (Jatoi et al. 2013; Siddiqui et al. 2023). Trematodes, including Brachylaima spp., Catatropis verrucosa, Echinostoma revolutum, Echinocardium recurvatum, Postharmostomum commutatum, Prosthogonimus spp. and Philophthalmus are prevalent in indigenous chickens globally (Paul et al. 2012; Yousfi et al. 2013). In the case of nematode, Allodapa suctoria, Ascaridia galli, Capillaria, Cheilospirura hamulosa, Dispharynx nasuta, Echinuria uncinata, Gongylonema congolense, Heterakis gallinarum, Strongyloides avium, Syngamus trachea, Tetrameres americana and Trichostrongylus tenuis are usually affect chickens (Ara et al. 2021; Luka and Ndams 2007; Permin et al. 1997; Ritu et al. 2024).

Parasitic infections, as their direct effects, increase feed conversion ratio (FCR), decrease growth rate, egg quality and egg production, and eventually cause death of birds particularly in severe cases (Rufai and Jato 2017; Sreedevi et al. 2016). Moreover, parasitic infections suppress immune responses and make the birds more vulnerable to secondary infectious diseases (Dalgaard et al. 2015; Dube et al. 2010; Horning et al. 2003; Pleidrup et al. 2014; Sharma, et al. 2019, Shohana et al. 2023). A plethora of data on prevalence of parasitic infections in semi‐scavenging chickens have been reported by scientists worldwide (da Silva et al. 2018; Percy et al. 2012; Tomza‐Marciniak et al. 2014), including India (Kumar et al. 2015) and the prevalence may reach up to 100% in scavenging indigenous chickens (Rabbi et al. 2006; Sherwin et al. 2013). Many factors are involved that affect the prevalence of parasitic infections in scavenging chickens, including geo‐climatic condition of the area, availability of the intermediate hosts, rearing system, management practices, awareness of the people and availability of quality veterinary services (Magwisha et al. 2002). Temperature and humidity act as important determinants for the prevalence of parasitic infections by directly influencing the development and survival of the infective stage in the external environment (Dube et al. 2010; Magwisha et al. 2002; Naphade and Chaudhari 2013; Ola‐Fadunsin et al. 2019).

For accurate diagnosis, detailed knowledge on species compositions of parasites and their locations within the hosts are necessary (Asumang et al. 2019). Previous investigations indicate the existence of parasites in indigenous chickens in different areas of Bangladesh (Shanta et al. 2006). However, over the decades, there are great changes in climatic conditions and management practices, including anthelmintic usages. On the other hand, studies on ectoparasitic infestations in Bangladesh have yet not been well addressed. Therefore, the present study was designed to find out the parasitic diversity and associated factors of parasitic infections in semi‐scavenging indigenous chickens in Bangladesh.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

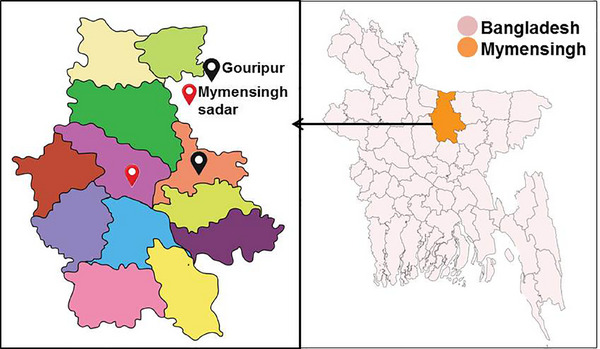

The study was conducted in semi‐scavenging indigenous chickens from different villages at Gauripur and Mymensingh Sadar upazila, Mymensingh district (Figure 1). The samples were processed and examined at the laboratory of the Department of Parasitology, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh, Bangladesh.

FIGURE 1.

Map of study area. The semi‐scavenging indigenous chickens were collected from different villages at Gauripur and Mymensingh Sadar upazila, Mymensingh district.

2.2. Study Period

The investigation was carried out during the period from April 2022 to March 2023.

2.3. Sample Size Determination

A simple random sampling strategy was used to investigate parasitic infections in chickens. The sample size was determined to be 309 from the study area using the formula, n = 1.962 (P exp(1 − P exp))/d 2, where n = sample size, P = expected prevalence, d = desired precision (Thrusfield 1995). The expected prevalence was used as 0.72 (72.47%) as per the available literature (Paul et al. 2012), a precision of 5% (d = 0.05), and confidence level 95% (i.e., 1.96). However, a total of 310 chickens were examined for this study.

2.4. Questionnaire Survey

During selection of chickens, the information related to age, sex, flock size, farming nature, use of anthelmintics and socioeconomic status of the owners were recorded by examining the chickens and conducting interviews with owners. Chickens were divided into two groups such as young (≤6 months, n = 208) and adult (>6 months, n = 102). Both male (n = 191) and female (n = 119) chickens were examined. Sex of chickens was determined by physical characteristics, including larger combs, hackles wattles and sickle feathers in males than in females, as well as more angular, masculine‐looking heads. On the other hand, females appeared more polished or feminine. Flock size was divided into small flock size (≤5 bird/flock) and large flock size (6–20 bird/flock). The farming nature of chickens was divided into single and mixed (co‐rearing). Farmers’ education levels were divided into two categories such as illiterate and literate. Socio‐economic status was classified as poor and medium.

2.5. Collection of Ecto‐Parasites

The selected semi‐scavenging chickens were thoroughly investigated by close inspection, digital palpation, parting of feathers against their natural direction for the detection of ecto‐parasitic infestations. Ecto‐parasites were manually collected from the different parts of the body.

2.6. Collection of Helminth Parasites

Adult parasites were isolated from different organs by post‐mortem examinations following the procedures described by Ritu et al. (2024).

2.7. Preparation of Samples and Microscopic Identification

The parasites were collected, washed with PBS and preserved in 70% glycerin alcohol. For trematodes, cestodes and ecto‐parasites, the permanent slide was prepared. Helminths were flattened and fixed with a mixture of alcohol, formalin and acetic acid (AFA) solution and dehydrated twice in 50% alcohol followed by 70% alcohol for 20 min in each case. Then the samples were treated with 70% iodine alcohol until violet colour developed followed by treatment with 70% alcohol for 20 min. Then, the samples were stained with semicon's carmine. The samples were then dehydrated with 70%, 80% and 90% alcohol for 20 min in each case and 100% alcohol for 1 h. The samples were placed in anelin oil until sunk, washed monetarily with xylin and finally mounted with canada balsam. For nematode parasites, temporary slide was prepared by adding one drop of lukewarm lactophenol. For ecto‐parasites, lice were washed with PBS and treated with 10% potassium hydroxide until the specimen become clear. Then the lice were dehydrated and permanent. Therefore, parasites were identified using microscope according to the morphological features described by Soulsby (1982) and Wall and Shearer (1997).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 to determine the level of significance between variables and parasitic infections. First, data were arranged for univariate analysis to find out the effect of individual factor on parasitic infections. The prevalence and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using sample‐size.net/confidence‐interval‐proportion. A statistically significant value was defined as p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. GI Helminths Were Predominant in Indigenous Semi‐Scavenging Chickens

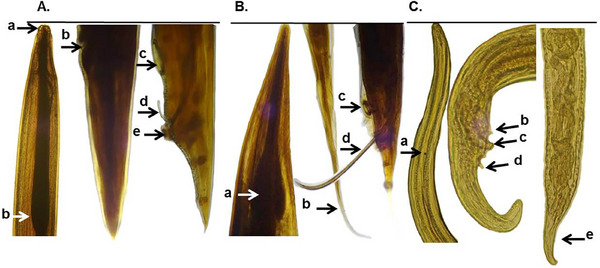

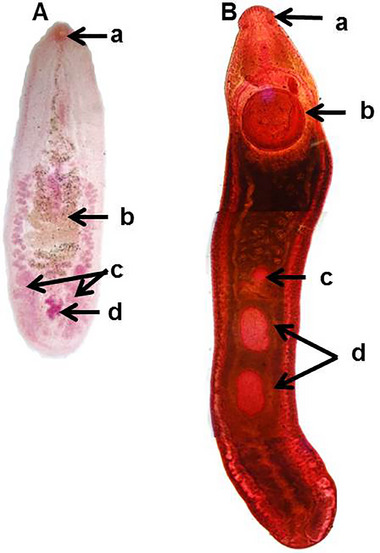

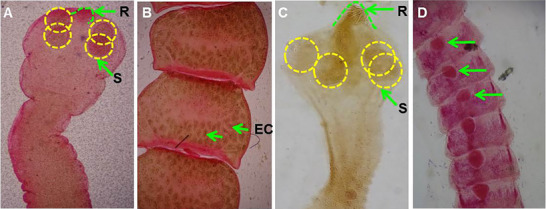

In this study, a total of 310 semi‐scavenging backyard chickens were examined, and 90.6% (281 out of 310) were found infected with one or more different species of helminths. Seven species of helminths were identified, of which three species of nematodes such as A. galli (188 out of 310, 60.6%), H. gallinarum (90 out of 310, 29.0%) and C. hamulosa (44 out of 310, 14.2%) (Figure 2); two species of trematodes: C. verrucosa (24 out of 310, 7.7%) and E. revolutum (23 out of 310, 7.4%) (Figure 3) and two species of cestodes: Raillietina spp. (237 out of 310, 76.5%) and Hymenolepis spp. (18 out of 310, 5.8%) (Figure 4). Out of seven identified helminths, Raillietina was the most prevalent (76.4%) parasites. Among the helminth infections, cestodes (77.1%) were predominant than nematodes (70.6%) and trematodes (11.3%). Infections with more than one species of helminths were detected in 65.8% samples (204 out of 310) (Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

Microscopic features of nematodes isolated from indigenous semi‐scavenging chickens. (A) Ascaridia galli, three lips at the anterior end (a) and simple oesophagus with no posterior bulb (b), vulvar opening of female (b), circular precloacal sucker (c), spicule (d) with a thick cuticular rim (e) of male. (B) Heterakis gallinarum, oesophagus with strong posterior bulb (a), tail of female (b), a prominent circular precloacal sucker (c) and unequal spicules (d) of male. (C) Cheilospirura hamulosa, cordon present at the anterior portion (a), pre‐cloacal (b) and post‐cloacal (d) papillae of male and tapering end of female (e).

FIGURE 3.

Microscopic features of trematodes recovered from indigenous semi‐scanenging chickens. (A) Catatropis verrucosa, oral sucker (a), uterus transversely coiled (b), testes horizontal at the posterior end of the body (c), ovary (d) in between testes (c). (B) Echinostoma revolutum, head collar with spines (a), large posterior (b) in anterior portion, ovary pretesticular (c) and lobulated testes tandem in position (d).

FIGURE 4.

Microscopic features of cestodes collected from indigenous semi‐scavenging chickens. (A) Scolex of Raillietina with armed rostellum (R) and four suckers (S) in scolex; (B) segment of Raillietina, egg within egg capsule (EC); (C) scolex of Hymenolepis with armed rostellum (R) and four suckers (S) in scolex; (D) segment of Hymenolepis having single set of reproductive organ (arrow).

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of gastrointestinal (GI) helminth infections in indigenous semi‐scavenging chickens in Mymensingh.

| Name of parasites | No. of infected chickens | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI of prevalence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nematodes | Ascaridia galli | 188 | 60.6 | 54.9–66.1 |

| Heterakis gallinarum | 90 | 29.0 | 24.0–34.4 | |

| Cheilospirura hamulosa | 44 | 14.1 | 10.2–18.5 | |

| Sub‐total | 219 a | 70.6 | 65.2–75.6 | |

| Trematodes | Catatropis verrucosa | 24 | 7.7 | 5.0–11.3 |

| Echinostoma revolutum | 23 | 7.4 | 4.7–10.9 | |

| Sub‐total | 35 a | 11.3 | 7.9–15.3 | |

| Cestodes | Raillietina spp. | 237 | 76.4 | 71.3–81.0 |

| Hymenolepis spp. | 18 | 5.8 | 3.4–9.0 | |

| Sub‐total | 239 a | 77.1 | 72.0–81.6 | |

| Mixed Infections | 204 | 65.8 | 60.5–71.1 | |

| Overall (310) | 281 a | 90.6 | 86.8–93.6 | |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Total no. of chickens affected is less than the summation of individual infection because the same chicken was infected with more than one type of gastro‐intestinal parasites.

3.2. Factors Related to GI Helminth Infections in Indigenous Semi‐Scavenging Chickens

To find out the factors associated with GI helminth infections in indigenous semi‐scavenging chickens, various predictor variables such as age, sex, flock size, farming nature, use of anthelmintics and socio‐economic status of farmers were considered. The univariate analysis revealed no statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference between the groups of the studied variables regarding helminth infections in indigenous chickens. However, adult chickens (94.1%), females (91.6%), chickens reared in large flock size (92.4%), mixed farming nature (92.7%), chickens those did not receive anthelmintics (90.9%) and reared by owners with poor socio‐economic status (93.1%) were more prone to GI helminth infections (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Factors associated with gastrointestinal (GI) helminth infections in indigenous semi‐scavenging chickens.

| Variables | Groups | No. of infected chickens | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI of prevalence | Odds ratio (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Gouripur (118) | 109 | 92.4 | 86.0–96.4 | 1.408 (0.537) |

| Mymensingh Sadar (192) | 172 | 89.6 | 84.4–93.5 | ||

| Age | >6 months (102) | 96 | 94.1 | 87.6–97.8 | 1.989 (0.207) |

| ≤6 months (208) | 185 | 88.9 | 83.9–92.9 | ||

| Sex | Female (191) | 175 | 91.6 | 86.7–95.1 | 1.341 (0.583) |

| Male (119) | 106 | 89.1 | 82.0–94.1 | ||

| Flock size | 6–20 (131) | 121 | 92.4 | 86.4–96.3 | 1.436 (0.488) |

| ≤5 (179) | 160 | 89.4 | 83.9–93.5 | ||

| Farming nature | Mixed (165) | 153 | 92.7 | 87.6–96.2 | 1.693 (0.250) |

| Single (145) | 128 | 88.3 | 81.9–93.0 | ||

| Use of anthelmintics | Not used (287) | 261 | 90.9 | 87.0–94.0 | 1.505 (0.217) |

| Used (23) | 20 | 87.0 | 66.4–97.2 | ||

| Socio‐economic status | Poor (72) | 67 | 93.1 | 84.5–97.7 | 1.502 (0.565) |

| Medium (238) | 214 | 89.9 | 85.4–93.4 |

3.3. Lice Infestations Were Prevalent in Indigenous Semi‐Scavenging Chickens

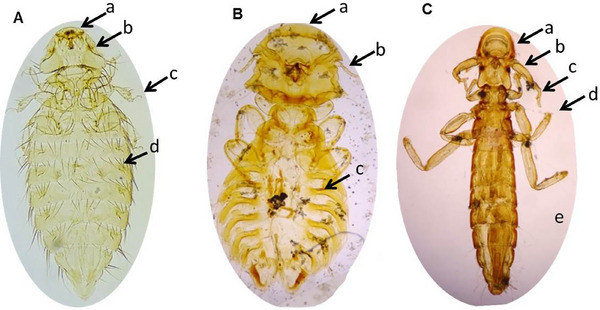

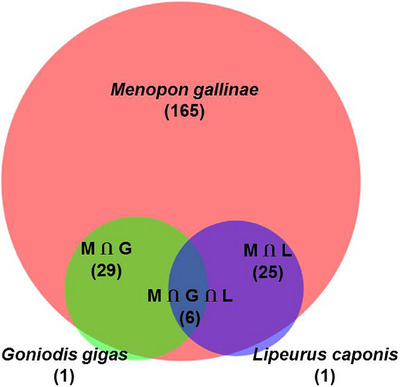

As mentioned above, all indigenous chickens (n = 310) were subjected to routine examination for the detection of ecto‐parasitic infestations. Only three species of lice were detected and the overall prevalence of lice infestations was 74.2% (230 out of 310). We identified M. gallinae (225, 72.6%), G. gigas (36, 11.6%) and L. caponis (32, 10.3%) on the basis of their key morphological features (Table 3 and Figure 5). Co‐infections with more than one lice were detected in 19.4% (60 out of 310) chickens. The combination of M. gallinae and G. gigas (48.3%, 29 out of 60), M. gallinae and L. caponis (41.7%, 25 out of 60) and G. gigas and L. caponis (10.0%, 6 out of 60) was recorded (Figure 6).

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of ecto‐parasitic infestations in indigenous semi‐scavenging chickens in Mymensingh.

| Name of parasites | No. of infected chickens | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI of prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menopon gallinae | 225 | 72.6 | 67.6–77.5 |

| Goniodes gigas | 36 | 11.6 | 8.2–15.7 |

| Lipeurus caponis | 32 | 10.3 | 7.2–14.3 |

| Mixed infections | 60 | 19.4 | 15.1–24.2 |

| Overall (310) | 230 a | 74.2 | 68.9–78.9 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Total no. of chickens affected is less than the summation of individual infection because the same chicken was infected with more than one type of ecto‐parasites.

FIGURE 5.

Morphological features of lice collected from indigenous chickens. (A) Menopon gallinae (10×); head rounded and broader than thorax (a), antenna lies in a groove (b), two claws in each tarsus (c), one row of abdominal setae in each segment (d). (B) Goniodes gigas (10×); head is rounded and broader than thorax (a), antenna with five segments (b), two claws in each tarsus (c). (C) Lipeurus caponis (10×); head longer than wide (a), antenna with five segments (b), first pair of leg shorter (c), two claws in each tarsus (d) and abdomen long, slender but wide in the middle (e).

FIGURE 6.

A Venn diagram representing co‐infestation of Menopon gallinae (M), Goniodes gigas (G) and Lipeurus caponis (L).

3.4. Factors That Influence Lice Infestations in Indigenous Semi‐Scavenging Chickens

To identify the factors influence the lice infestations in indigenous chickens, several biotic and abiotic factors such as area, age, sex, flock size, farming nature, use of insecticides and socio‐economic status of owners were studied and subjected to univariate analysis. Among these factors, large flock size (87.0%) and mixed farming (81.2%) were significantly (p < 0.05) associated with lice infestations in chickens (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Factors associated with ecto‐parasitic infestations in indigenous chickens.

| Variables | Groups | No. of infected chickens | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI of prevalence | Odds ratio (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Mymensingh (192) | 150 | 78.1 | 71.6–83.8 | 1.696 (0.059) |

| Gouripur (118) | 80 | 67.8 | 58.6–76.1 | ||

| Age | >6–12 months (102) | 81 | 79.4 | 70.3–86.8 | 1.527 (0.183) |

| 1–6 months (208) | 149 | 71.6 | 64.9–77.7 | ||

| Sex | Male (119) | 90 | 75.6 | 66.9–83.0 | 1.130 (0.751) |

| Female (191) | 140 | 73.3 | 66.4–79.4 | ||

| Flock size | 6–20 (131) | 114 | 87.0 | 80.0–92.2 | 3.64 (<0.0001) |

| ≤5 (179) | 116 | 64.8 | 57.3–71.8 | ||

| Farming nature | Mixed (165) | 134 | 81.2 | 74.4–86.9 | 2.206 (0.003) |

| Single (145) | 96 | 66.2 | 57.9–73.9 | ||

| Use of insecticides | Not used (287) | 217 | 75.6 | 70.2–80.5 | 2.38 (0.07) |

| Used (23) | 13 | 56.5 | 34.5–76.8 | ||

| Socio‐economic status | Poor (72) | 58 | 80.5 | 69.5–88.9 | 1.589 (0.210) |

| Normal (238) | 172 | 72.2 | 66.1–77.9 |

4. Discussion

Indigenous chickens are major concern to the public health because they serve as potential reservoirs of various pathogens. Semi‐scavenging rearing of chickens increases the chances of close contact with other domestic, peri domestic and wild birds resulting in the transmission of different types of pathogens, including parasites (Pohjola et al. 2016; Whitehead and Roberts 2014). In the present study, we identified several species of helminths and lice in semi‐scavenging indigenous chickens.

In this study, the overall prevalence of GI helminth infections was very high in the study area. The earlier reports regarding the prevalence of GI helminth infections are in‐line with the findings of the present study. Rabbi et al. (2006) and Ferdushy, Hasan, and Kadir (2016) recorded a very high prevalence of GI helminth infection in indigenous chickens in Mymensingh (100%) and Narsingdi (84.6%) districts of Bangladesh. Moreover, studies from the neighbouring country, India also reported the same prevalence (90.9%) of helminth infections (Yadav and Tandon 1991). The high prevalence of parasitic infections in indigenous chickens might be related to the management system, control strategies of parasites and climatic condition of the study area (Magwisha et al. 2002; Yadav and Tandon 1991). The subtropical climatic conditions of Bangladesh and India such as warm and humid summers, heavy rainfall and moderately to cold winters are suitable for the growth and survival of the developmental stages of a wide variety of parasites (Dey et al. 2020).

In this study, seven species of helminth parasites were detected by post‐mortem examination indicating existence of wide range of parasites in the studied area. Similar finding had also been demonstrated in different parts of the world. For example, seven species of helminths had been detected in Nigeria (Adang et al. 2014) from slaughtered chickens, four in Iran (Badparva et al. 2015) and three species in Poland by coprological examination (Tomza‐Marciniak et al. 2014). However, 16 species, the largest range of helminths species had been detected in South Africa from slaughtered birds (Mukaratirwa and Khumalo 2010). Diagnosis of parasitic infections from coproscopic examination did not provide the accurate diversity of helminth infections due to missing of eggs or developmental stages. However, the post‐mortem examination reveals the exact results, thus emphasizing the limitations of diagnosis of GI helminth from faecal samples (Permin and Hansen 1998). The existence of a wide range of helminth parasites might be due to favourable environmental condition, availability of intermediate host, management system of chickens, reluctance to take veterinary service and lack of appropriate control strategy against parasites.

The present study revealed that cestodes (77.1%) and nematodes (70.6%) were more prevalent than trematodes (11.3%). In this study, the examined chickens were reared in semi‐scavenging system by extensive management system, which enhances the exposure in chickens to the developmental stages of GI parasites along with their intermediate/paratenic hosts such as insects and earthworms (Mwale and Masika 2011). The intermediate/paratenic hosts, including ants, flies, grasshoppers and earthworm are commonly found in the terrestrial environment. In contrast, fresh water snails act as the intermediate host for trematodes but chickens are terrestrial scavengers. Chickens usually do not scavenge in the open water bodies; therefore, the chance of ingestion of snail by chickens is very low. However, trematode infections induce behavioural changes of snail and alter their normal responses to the environmental stimuli and can migrate to the land or vegetation.

The present study indicated that lice infestations were also very high in indigenous semi‐scavenging chickens in the studied area. During collection of data, the awareness of the owners related to parasitic infections revealed less attention regarding the hygienic management and control strategy. Lice are most prevalent and extensively spreading ecto‐parasites in different parts of the world and a major constraint in profitable chicken production globally (Bala et al. 2011; Onyekachi 2021; Tamiru et al. 2014). The prevalence of lice infestation is influenced by geo‐climatic conditions such as temperature, rainfall and humidity and husbandry practice. Lice are permanent ecto‐parasites and exist in specific location of the host body (Wall and Shearer 2008). The direct effects of lice infestations in chickens are restlessness, irritation, loss of blood, dermatitis, tissue damage resulting decrease in egg and meat production (Ikpeze et al. 2008; Mekuria and Gezahegn 2010; Tamiru et al. 2014) and eventually death of heavily infested chicks, leading to significant losses to the poultry industry (Murillo and Mullens 2016). In addition, lice are suspected to transmit a number of pathogens such as filarial nematodes from wild and peri domestic birds, including Pelecitus fulicaeatrae, Sarconema eurycera and Eulimdana sp. Lice also transmit opportunistic bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes (Burkhart and Burkhart 2007) and lice‐borne infectious diseases (LBD), including epidemic typhus by Rickettsia prowazekii, louse‐borne relapsing fever by Borrelia recurrentis and trench fever by Bartonella quintana causing public health hazard (Deng et al. 2023).

The present study detected three species of lice, namely, M. gallinae (72.6%), G. gigas (11.6%) and L. caponis (10.3%), which confirms the findings of Furgasa (2021) in Ethiopia and Bala et al. (2011) in Nigeria. However, a total of six species of lice have been recorded by the scientists in the USA (Murillo and Mullens 2016) indicating a very wide distribution of these ecto‐parasites in both tropical and temporal zones. Co‐infestations with multiple species of lice were very common, which were also observed in Ethiopia (Amede, Tilahun, and Bekele 2011; Tamiru et al. 2014) and Iraq (Al‐Saffar and Al‐Mawla 2008). Lice are transmitted by direct contact with the infested individuals. In semi‐scavenging system, although birds are allowed to scavenge freely at day period, they are kept in confinement at night which facilitates lice infestation. Therefore, lice infestations are commonly found in semi‐scavenging indigenous chickens than those reared in cage and confined flocks (Murillo and Mullens 2016).

Among the identified lice, M. gallinae (72.6%) was most prevalent which is in agreement with the findings of Mansur et al. (2019) in Algeria. However, a low prevalence of this louse had also been reported in Bulgaria (35.9%) (Prelezov, Groseva, and Gundasheva 2006) and Iran (13.66 %) (Rezaei et al. 2016). Variation of prevalence in different regions may be due to different climatic condition, nutritional status, inadequate health care service and management practices (Arya, Negi, and Singh 2013).

The present findings revealed that flock size and farming nature were significantly (p < 0.05) associated with lice infestation in semi‐scavenging chickens. Tamiru et al. (2014) in Ethiopia and Bal et al. (2016) in India also recorded a higher infestation of lice in large flock. Transmission of lice from one bird to others mainly depends on direct contact. In large flock size, due to close contact of birds, the chance of transmitting infestation is increased (Dey et al. 2020). In this study, ecto‐parasitic infestation was found more in mixed birds farming (81.2%) than that of single chicken farming (66.2%). Higher prevalence ecto‐parasites had also been detected in mixed farming in Kenya (Sabuni et al. 2010) and Meerut (Kansal and Singh 2014). Farming nature is an important factor in the transmission of diseases. In the rural area of Bangladesh mixed farming is widely practised.

In univariate analysis, data related to anthelmintic/insecticides treated or untreated chickens surprisingly showed a very high prevalence of parasite in anthelmintic treated (87.0%) and insecticides treated (56.5%) chickens. This might be due to information gap in data recording in treatment pattern by the farmers, inaccurate dosing and drug quality. However, the possibility of development of anthelmintic resistance (AR) against the available and commonly used anthelmintic/insecticides cannot be ruled out, and AR against albendazole, mebendazole and piperazine has recently been detected in Bangladesh (Ritu et al. 2024).

5. Conclusions

The present study revealed a very high rate of GI helminth infections and lice infestations in indigenous scavenging chickens. Seven species of helminths have been detected, of which cestodes infections are predominant. Three species of lice have been identified, and M. gallinae (72.6%) is the most abundant. Co‐infections have been found in helminth infections and lice infestation in chickens. Among biotic and abiotic factors, only large flock size and mixed farming nature are significantly associated with lice infestations. It is essential to increase the awareness related to management system of chickens. The findings of the present study will assist in formulating a control strategy against parasitic infections in indigenous chickens.

Author Contributions

Kausar‐A‐Noor: writing–original draft, methodology, formal analysis, software and data curation. Md. Mehadi Hasan: investigation, methodology, validation, software, data curation and writing–original draft. Anisuzzaman: writing–review and editing, validation, formal analysis and data curation. Mohammad Zahangir Alam: writing–review and editing, investigation, software and formal analysis. Mst. Sawda Khatun: investigation, methodology, visualization and formal analysis. Anita Rani Dey: conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing–review and editing, project administration, supervision, validation and resources.

Ethics Statement

During performing this research, the authors maintained the all possible ethical standards in their works. The Animal welfare and ethical committee of Bangladesh Agricultural University (AWEEC/BAU/2022 (3)) approved the research works.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/vms3.70211.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Bangladesh Agricultural University (Project No.: 2019/759/BAU) for funding the research.

Funding: The authors acknowledge Bangladesh Agricultural University (Project No.: 2019/759/BAU) for funding the research.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Adang, K. , Asher R., and Abba R.. 2014. “Gastro‐Intestinal Helminths of Domestic Chickens (Gallus gallus domestica) and Ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) Slaughtered at Gombe Main Market, Gombe State, Nigeria.” Asian Journal of Poultry Science 8, no. 2: 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Saffar, T. , and Al‐Mawla E.. 2008. “Some Hematological Changes in Chickens Infected With Ectoparasites in Mosul.” Iraqi Journal of Veterinary Sciences 22, no. 2: 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Amede, Y. , Tilahun K., and Bekele M.. 2011. “Prevalence of Ectoparasites in Haramaya University Intensive Poultry Farm.” Global Veterinaria 7, no. 3: 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Ara, I. , Khan H., Syed T., and Bhat B.. 2021. “Prevalence and Seasonal Dynamics of Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Domestic Fowls (Gallus gallus domesticus) in Kashmir, India.” Journal of Advanced Veterinary and Animal Research 8, no. 3: 448–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya, S. , Negi S., and Singh S. K.. 2013. “Prevalence of Menopon gallinae Linn.(Insecta, Phthiraptera, Menoponidae, Amblycera) Upon Poultry Birds (Gallus gallus domesticus) of Selected Locality of District Chamoli Garhwal (Uttarakhand), India.” Journal of Applied and Natural Science 5, no. 2: 400–405. [Google Scholar]

- Asumang, P. , Delali J. A., Wiafe F., et al. 2019. “Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Parasites in Local and Exotic Breeds of Chickens in Pankrono–Kumasi, Ghana.” Journal of Parasitology Research 2019: 5746515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badparva, E. , Ezatpour B., Azami M., and Badparva M.. 2015. “First Report of Birds Infection by Intestinal Parasites in Khorramabad, West Iran.” Journal of Parasitic Diseases 39: 720–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal, G. , Panda M., Mohanty B., and Dehuri M.. 2016. “Incidence of Ectoparasites in Indigenous Fowls in and Around Bhubaneswar, Odisha.” Indian Journal of Poultry Science 51, no. 1: 113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bala, A. , Anka S., Waziri A., and Shehu H.. 2011. “Preliminary Survey of Ectoparasites Infesting Chickens (Gallus domesticus) in Four Areas of Sokoto Metropolis.” Nigerian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 19, no. 2: 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart, C. N. , and Burkhart C. G.. 2007. “Fomite Transmission in Head Lice.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 56, no. 6: 1044–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard, T. S. , Skovgaard K., Norup L. R., et al. 2015. “Immune Gene Expression in the Spleen of Chickens Experimentally Infected With Ascaridia galli .” Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology 164, no. 1–2: 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, G. S. , Romera D. M., da Silva Conhalato G., Soares V. E., and Meireles M. V.. 2018. “Helminth Infections in Chickens (Gallus domesticus) Raised in Different Production Systems in Brazil.” Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports 12: 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.‐P. , Fu Y.‐T., Yao C., et al. 2023. “Emerging Bacterial Infectious Diseases/Pathogens Vectored by Human Lice.” Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 55: 102630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A. R. , Begum N., Alim M. A., Malakar S., Islam M. T., and Alam M. Z.. 2020. “Gastro‐Intestinal Nematodes in Goats in Bangladesh: A Large‐Scale Epidemiological Study on the Prevalence and Risk Factors.” Parasite Epidemiology Control 9: e00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube, S. , Zindi P., Mbanga J., and Dube C.. 2010. “A Study of Scavenging Poultry Gastrointestinal and Ecto‐Parasites in Rural Areas of Matebeleland Province, Zimbabwe.” International Journal of Poultry Science 9: 911–915. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdushy, T. , Hasan M. T., and Kadir A. K. M. G.. 2016. “Cross Sectional Epidemiological Investigation on the Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Helminths in Free Range Chickens in Narsingdi District, Bangladesh.” Journal of Parasitic Diseases 40, no. 3: 818–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furgasa, W. 2021. “Investigation of Major Ecto‐Parasite Affecting Backyard Chickens in Bishoftu Town, Ethiopia.” Journal of Medicine and Healthcare 143: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Horning, G. , Rasmussen S., Permin A., and Bisgaard M.. 2003. “Investigations on the Influence of Helminth Parasites on Vaccination of Chickens Against Newcastle Disease Virus Under Village Conditions.” Tropical Animal Health and Production 35: 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikpeze, O. O. , Amagba I. C., and Eneanya C. I.. 2008. “Preliminary Survey of Ectoparasites of Chicken in Awka, South‐Eastern Nigeria.” Animal Research International 5, no. 2: 848–851. [Google Scholar]

- Jatoi, A. S. , Jaspal M. H., Mahmood S., et al. 2013. “Incidence of Cestodes in Indigenous (Desi) Chickens Maintained in District Larkana.” Sarhad Journal of Agriculture 29: 449–453. [Google Scholar]

- Kansal, G. , and Singh H. S.. 2014. “Incidence of Ectoparasites in Broiler Chicken in Meerut.” IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science 7, no. 1: 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. , Garg R., Ram H., Maurya P., and Banerjee P.. 2015. “Gastrointestinal Parasitic Infections in Chickens of Upper Gangetic Plains of India With Special Reference to Poultry Coccidiosis.” Journal of Parasitic Diseases 39: 22–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luka, S. , and Ndams I.. 2007. “Short Communication Report: Gastrointestinal Parasites of Domestic Chicken Gallus gallus domesticus Linnaeus 1758 in Samaru, Zaria Nigeria.” Science World Journal 2, no. 1: 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Magwisha, H. , Kassuku A., Kyvsgaard N., and Permin A.. 2002. “A Comparison of the Prevalence and Burdens of Helminth Infections in Growers and Adult Free‐Range Chickens.” Tropical Animal Health and Production 34: 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansur, M. , Mahmoud N., Allamoushi S., and El Aziz M. A.. 2019. “Biodiversity and Prevalence of Chewing Lice on Local Poultry.” Journal of Dairy, Veterinary and Animal Research 8: 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mekuria, S. , and Gezahegn E.. 2010. “Prevalence of External Parasite of Poultry in Intensive and Backyard Chicken Farm at Wolayta Soddo Town, Southern Ethiopia.” Veterinary World 3, no. 22: 533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Mukaratirwa, S. , and Khumalo M.. 2010. “Prevalence of Helminth Parasites in Free‐Range Chickens From Selected Rural Communities in KwaZulu‐Natal Province of South Africa.” Journal of the South African Veterinary Association 81, no. 2: 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillo, A. C. , and Mullens B. A.. 2016. “Diversity and Prevalence of Ectoparasites on Backyard Chicken Flocks in California.” Journal of Medical Entomology 53, no. 3: 707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwale, M. , and Masika P. J.. 2011. “Point Prevalence Study of Gastro‐Intestinal Parasites in Village Chickens of Centane District, South Africa.” African Journal of Agricultural Research 6, no. 9: 2033–2038. [Google Scholar]

- Naphade, S. , and Chaudhari K.. 2013. “Studies on the Seasonal Prevalence of Parasitic Helminths in Gavran (Desi) Chickens From Marathwada Region of Maharashtra.” International Journal of Fauna and Biological Studies 1, no. 2: 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ola‐Fadunsin, S. D. , Uwabujo P. I., Sanda I. M., et al. 2019. “Gastrointestinal Helminths of Intensively Managed Poultry in Kwara Central, Kwara State, Nigeria: Its Diversity, Prevalence, Intensity, and Risk Factors.” Veterinary World 12, no. 3: 389–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyekachi, O. 2021. “Prevalence of Ectoparasites Infestation of Chicken in Three Poultry Farms in Awka.” Asian Basic and Applied Research Journal 3: 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, D. R. , Dey A. R., Bilkis F., Begum N., and Mondal M. M. H.. 2012. “Epidemiology and Pathology of Intestinal Helminthiasis in Fowls.” Eurasian Journal of Veterinary Sciences 28, no. 1: 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Percy, J. , Pias M., Enetia B. D., and Lucia T.. 2012. “Seasonality of Parasitism in Free Range Chickens From a Selected Ward of a Rural District in Zimbabwe.” African Journal of Agricultural Research 7, no. 25: 3626–3631. [Google Scholar]

- Permin, A. , and Hansen J. W.. 1998. Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Control of Poultry Parasites. Rome: FAO. [Google Scholar]

- Permin, A. , Magwisha H., Kassuku A., et al. 1997. “A Cross‐Sectional Study of Helminths in Rural Scavenging Poultry in Tanzania in Relation to Season and Climate.” Journal of Helminthology 71, no. 3: 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleidrup, J. , Dalgaard T. S., Norup L. R., et al. 2014. “ Ascaridia galli Infection Influences the Development of Both Humoral and Cell‐Mediated Immunity After Newcastle Disease Vaccination in Chickens.” Vaccine 32, no. 3: 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohjola, L. , Nykasenoja S., Kivisto R., et al. 2016. “Zoonotic Public Health Hazards in Backyard Chickens.” Zoonoses and Public Health 63, no. 5: 420–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen, J. , Permin A., Hindsbo O., Yelifari L., Nansen P., and Bloch P.. 2000. “Prevalence and Distribution of Gastro‐Intestinal Helminths and Haemoparasites in Young Scavenging Chickens in Upper Eastern Region of Ghana, West Africa.” Preventive Veterinary Medicine 45, no. 3–4: 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelezov, P. , Groseva N. I., and Gundasheva D.. 2006. “Pathomorphological Changes in the Tissues of Chickens, Experimentally Infected With Biting Lice (Insecta: Phthiraptera).” Veterinarski Arhiv 76, no. 3: 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbi, A. , Islam A., Majumder S., Anisuzzaman A., and Rahman M.. 2006. “Gastrointestinal Helminths Infection in Different Types of Poultry.” Bangladesh Journal of Veterinary Medicine 4, no. 1: 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ramnath, J. , Jyrwa D. B., Dutta A. K., Das B., and Tandon V.. 2014. “Molecular Characterization of the Indian Poultry Nodular Tapeworm, Raillietina echinobothrida (Cestoda: Cyclophyllidea: Davaineidae) Based on rDNA Internal Transcribed Spacer 2 Region.” Journal of Parasitic Diseases 38: 22–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, F. , Hashemnia M., Chalechale A., Seidi S., and Gholizadeh M.. 2016. “Prevalence of Ectoparasites in Free‐Range Backyard Chickens, Domestic Pigeons (Columba livia domestica) and Turkeys of Kermanshah Province, West of Iran.” Journal of Parasitic Diseases 40: 448–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritu, S. N. , Labony S. S., Hossain M. S., et al. 2024. “ Ascaridia galli, a Common Nematode in Semi‐Scavenging Indigenous Chickens in Bangladesh: Epidemiology, Genetic Diversity, Pathobiology, Ex Vivo Culture and Anthelmintic Efficacy.” Poultry Science 103: 103405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufai, M. , and Jato A.. 2017. “Assessing the Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Tract Parasites of Poultry and Their Environmental Risk Factors in Poultry in Iwo, Osun State Nigeria.” Ife Journal of Science 19, no. 1: 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sabuni, Z. , Mbuthia P., Maingi N., et al. 2010. “Prevalence of Ectoparasites Infestation in Indigenous Free‐Ranging Village Chickens in Different Agro‐Ecological Zones in Kenya.” Livestock Research for Rural Development 22, no. 11: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Shanta, I. , Begum N., Anisuzzaman A., Bari A., and Karim M.. 2006. “Prevalence and Clinico‐Pathological Effects of Ectoparasites in Backyard Poultry.” Bangladesh Journal of Veterinary Medicine 4, no. 1: 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, N. , Hunt P. W., Hine B. C., and Ruhnke I.. 2019. “The Impacts of Ascaridia galli on Performance, Health, and Immune Responses of Laying Hens: New Insights Into an Old Problem.” Poultry Science 98, no. 12: 6517–6526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin, C. M. , Nasr M. A., Gale E., et al. 2013. “Prevalence of Nematode Infection and Faecal Egg Counts in Free‐Range Laying Hens: Relations to Housing and Husbandry.” British Poultry Science 54, no. 1: 12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifaw, A. , Feyera T., Walkden‐Brown S. W., Sharpe B., Elliott T., and Ruhnke I.. 2021. “Global and Regional Prevalence of Helminth Infection in Chickens Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis.” Poultry Science 100, no. 5: 101082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shohana, N. N. , Rony S. A., Ali M. H., et al. 2023. “ Ascaridia galli Infection in Chicken: Pathobiology and Immunological Orchestra.” Immunity, Inflammation and Disease 11, no. 9: e1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, T. R. , Hoque M. R., Roy B. C., Alam M. Z., Khatun M. S., and Dey A. R.. 2023. “Morphological and Phylogenetic Analysis of Raillietina spp. In Indigenous Chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) in Bangladesh.” Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 30, no. 10: 103784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby, E. J. L. 1982. Helminths, Arthropod and Protozoa of Domesticated Animals. London: Bailliere Tindall and Cassell Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Sreedevi, C. , Jyothisree C., Rama Devi V., Annapurna P., and Jeyabal L.. 2016. “Seasonal Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Parasites in Desi Fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus) in and Around Gannavaram, Andhra Pradesh.” Journal of Parasitic Diseases 40: 656–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamiru, F. , Dagmawit A., Askale G., Solomon S., Morka D., and Waktole T.. 2014. “Prevalence of Ectoparasite Infestation in Chicken in and Around Ambo Town, Ethiopia.” Journal of Veterinary Science and Technology 5, no. 189: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Thrusfield, M. 1995. Veterinary Epidemiology. Cambridge: Blackwell Science Ltd., Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Tomza‐Marciniak, A. , Pilarczyk B., Tobianska B., and Tarasewicz N.. 2014. “Gastrointestinal Parasites of Free‐Range Chickens.” Annals of Parasitology 60, no. 4: 305–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall, R. , and Shearer D.. 1997. Veterinary Entomology: Arthropod Ectoparasites of Veterinary Importance. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, R. L. , and Shearer D.. 2008. Veterinary Ectoparasites: Biology, Pathology and Control. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, M. , and Roberts V.. 2014. “Backyard Poultry: Legislation, Zoonoses and Disease Prevention.” Journal of Small Animal Practice 55, no. 10: 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A. K. , and Tandon V.. 1991. “Helminth Parasitism of Domestic Fowl (Gallus domesticus L.) in a Subtropical High‐Rainfall Area of India.” Beitrage Zur Tropischen Landwirtschaft Und Veterinarmedizin 29, no. 1: 97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousfi, F. , Senouci K., Medjoual I., Djellil H., and Slimane T. H.. 2013. “Gastrointestinal Helminths in the Local Chicken Gallus Gallus domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Traditional Breeding of North‐Western Algeria.” Biodiversity Journal 4, no. 1: 229–234. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.