Abstract

Members of the Sso7d/Sac7d family are small, abundant, non-specific DNA-binding proteins of the hyperthermophilic Archaea Sulfolobus. Crystal structures of these proteins in complex with oligonucleotides showed that they induce changes in the helical twist and marked DNA bending. On this basis they have been suggested to play a role in organising chromatin structures in these prokaryotes, which lack histones. We report functional in vitro assays to investigate the effects of the observed Sso7d-induced structural modifications on DNA geometry and topology. We show that binding of multiple Sso7d molecules to short DNA fragments induces significant curvature and reduces the stiffness of the complex. Sso7d induces negative supercoiling of DNA molecules of any topology (relaxed, positively or negatively supercoiled) and in physiological conditions of temperature and template topology. Binding of Sso7d induces compaction of positively supercoiled and relaxed DNA molecules, but not of negatively supercoiled ones. Finally, Sso7d inhibits the positive supercoiling activity of the thermophile-specific enzyme reverse gyrase. The proposed biological relevance of these observations is that these proteins might model the behaviour of DNA in constrained chromatin environments.

INTRODUCTION

Variations of DNA supercoiling are intimately concerned with packaging of DNA and with its manipulation in crucial biological processes such as chromosome condensation, regulation of gene expression and unravelling of topological domains after completion of DNA replication. Moreover, DNA supercoiling regulates the double helix stability, providing melting potential (if negative) or stabilisation (if positive) (1). DNA superhelicity is regulated by the complex interplay of topoisomerases and DNA-binding proteins. In Eubacteria and Eukarya DNA is overall negatively supercoiled, due to the action of gyrase and the wrapping around of core histones, respectively. In contrast, episomal DNAs have been found to be from relaxed to positively supercoiled in several thermophilic Archaea (2,3). Positive supercoiling correlates with the presence of the peculiar enzyme reverse gyrase (reviewed in 4,5), which has been found in all hyperthermophilic organisms tested, suggesting that it plays a key role in the stabilisation of DNA to high temperatures (1,6,7).

Archaeal strains belonging to the subdomain Euryarchaeota contain structural and functional homologues of eukaryal histones (8–10). In contrast, members of the subdomain Crenarchaeota have neither histones nor gyrase. In the hyperthermophilic genus Sulfolobus the protein family Sso7d has been suggested to play an ‘architectural’ role. These are 7 kDa, basic, highly abundant, non-specific DNA-binding proteins, and include the almost identical members Sso7d, Sac7d and Ssh7d found in different Sulfolobus strains. Diverse activities have been reported for these proteins: stabilisation of the double helix (11), annealing of DNA above its melting point (12), ATPase activity and rescue of aggregated proteins (13). Moreover, they distort DNA conformation, introducing unwinding of the helix (14,15) and negative supercoiling (16,17; see below). The relationships between those different activities, as well as their role in vivo, are currently not understood; unfortunately, due to the lack of genetic tools for Sulfolobus, it is not possible to directly address these questions.

X-ray structures of complexes containing one protein molecule and short oligonucleotides indicated that binding of Sso7d and Sac7d cause a sharp kink in DNA and introduces significant unwinding of the helix (14,15). X-ray scattering has been used to study the interaction of Sac7d with longer linear DNA molecules and used to draw a molecular model (18). In this model the protein molecules bind outside the double helix and induce repeating compensatory kinks in the DNA, with little change in its overall topology and no noticeable supercoiling or compaction; on this basis, involvement of these proteins in packing of DNA and supercoiling has been questioned. Functional data do not completely support the predictions of this model. In electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) both Sso7d and Ssh7d failed to show detectable compaction of linear, negatively supercoiled and nicked DNA molecules (12,17), but in ligase-mediated supercoiling assays both Sso7d and Ssh7d induced negative supercoiling of nicked DNA molecules (16,17).

We have set up a number of functional in vitro assays to clarify the reasons for these discrepancies and to test the effects Sso7d on DNA conformation when it is topologically closed. We show that Sso7d induces: (i) curvature of short DNA molecules in solution; (ii) negative supercoiling of DNA molecules of any topology (relaxed, negatively or positively supercoiled); (iii) compaction of relaxed and positively supercoiled DNA minicircles, but not of negatively supercoiled ones. Induction of negative supercoiling also occurs under conditions mimicking those in vivo, in the presence of endogenous topoisomerase (Topo) VI. Finally, we show that Sso7d inhibits the positive supercoiling activity of reverse gyrase. The implications of these results on Sso7d function and its possible role in the control of DNA conformation and packing are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins

Reverse gyrase was prepared from Sulfolobus shibatae as described (19). Recombinant Topo VI was prepared as described (20). Sso7d from Sulfolobus solfataricus was prepared as described (21). Topo I was purchased from Promega.

Ring-closure assay

The 129 bp EcoRI DNA fragment contained 98 bp of the upstream region of the S.solfataricus lrs14 gene, including the binding site of Lrs14 (22), plus 31 bp from the pGEM-T vector polylinker. The end-labelled fragment (1 ng) was incubated with the appropriate protein for 20 min at 30°C, then T4 DNA ligase was added and reactions were incubated for an additional 30 min at 30°C. After incubation, 1% SDS, 1 M NaCl was added and samples were extracted with 1 vol chloroform (SEVAG extraction) (23) and ethanol precipitated. Samples were loaded on 5% polyacrylamide gels and run at room temperature in 0.5× TBE buffer.

Preparation of minicircle topoisomers

The procedure described (24) was followed. The end-labelled 371 bp AclI fragment from pUC18 was incubated (0.11 µg/ml, final volume 250 µl) in ligase buffer in the presence of 400 U T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) and ethidium bromide at 0.2, 0.6 or 1.2 µg/ml for 18 h at 16°C. Samples were deproteinised by SEVAG extraction followed by ethanol precipitation and loaded on preparative 5% polyacrylamide gels. Minicircles were gel purified by SEVAG extraction and ethanol precipitation.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The standard reaction mixture (10 µl) contained 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, 10% glycerol, 12 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 1 × 104 c.p.m. labelled DNA probe; samples were preincubated for 10 min, then the appropriate amount of Sso7d was added and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. Samples were immediately loaded on non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× TBE buffer and run at 60 V for 18 h at room temperature.

Topo I assays

Assays were performed as reported (25) with the following modifications. Sso7d–DNA binding reaction mixes prepared as described above were incubated with 2 U of DNA Topo I for 1 h at 37°C. After SEVAG extraction and ethanol precipitation, samples were loaded on non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gels and run at room temperature in 0.5× TBE buffer.

Topo VI assays

Relaxed to positively supercoiled pBR322 was prepared by incubation with netropsin (26). Plasmid DNA (30 µg/ml, final reaction volume 200 µl) was equilibrated with netropsin (4 µg/ml) for 10 min, then 2 U of Topo I/µg DNA was added and the samples were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After incubation samples were SEVAG extracted, ethanol precipitated and analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Topo VI assays were performed as reported (20), with modifications. The standard reaction mixture (20 µl) contained 35 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 30 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM spermidine, 2 mM ATP, 200 ng pBR322 plasmid DNA, 100 ng purified Topo VI and 75 ng Sso7d, if needed. After incubation at the indicated temperature for 5 min, reactions were stopped by cooling, addition of 1% SDS, SEVAG extraction and ethanol precipitation. Reaction products were analysed by 2-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels in TBE buffer at room temperature. Negatively to positively supercoiled plasmids were separated using no intercalating agent in the first dimension and 10 ng/ml ethidium bromide in the second dimension. Running conditions were 25 mA for 16–17 h and 15 mA for 22 h, respectively. Stained gels were photographed under UV light using the SONY UVP Image Store 5000 system.

Reverse gyrase assays

Assays were performed as reported (19), with modifications. The standard reaction mixture (20 µl) contained 35 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, 30 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, different amounts of Sso7d, 320 ng negatively supercoiled pTZ18R and 9 U reverse gyrase. After incubation for 20 min at 72°C, reactions were stopped by cooling, addition of 1% SDS, SEVAG extraction and ethanol precipitation. Reaction products were analysed by 2-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis as described above.

RESULTS

Sso7d curves small DNA circles

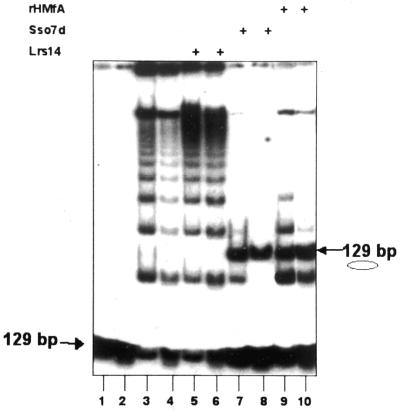

Resolution of the 3-dimensional structure of complexes formed by Sso7d and Sac7d with short oligonucleotides showed that both proteins induce a sharp kink in DNA (14,15). Small-angle X-ray scattering data were obtained for multimeric Sac7d complexes with long DNA polymers and were used to construct a molecular model, in which the repeated bends induced by protein binding are compensatory and the resulting complex has an extended, rod-shaped structure (18). One prediction of this model is that a DNA fragment saturated with the protein behaves as a stiff molecule, in contrast to what was observed for most bending proteins that curve or loop the double helix. To gain more information on the DNA-bending activity of Sso7d we used the ring-closure assay (27). This assay uses short (70–150 bp) linear DNA substrates with cohesive ends that behave as rigid molecules in solution. Proteins that bend DNA stimulate intramolecular ligation of such fragments, whereas proteins that increase the rigidity/persistence length of DNA inhibit circularisation. We have performed such an assay using a 129 bp DNA fragment (Fig. 1) that was multimerised by T4 DNA ligase, but did not allow efficient circularisation, under the conditions used. To ensure the formation of saturating complexes we used a ratio of 26 Sso7d molecules/bp, a large stoichiometrical excess considering that the binding site of the protein is 3 bp (14); under these conditions there is no free DNA (data not shown). As a positive control we used the histone homologue HMfA of Methanothermus fervidus, which is known to bend DNA (28). The addition of Sso7d or HMfA induced the formation of a new band absent in the control. Digestion with endonuclease Bal31 and restiction enzymes showed that this band corresponds to the circular monomer (data not shown). In the Sso7d reactions the circle band dominated, whereas bands corresponding to multimers were significantly reduced, indicating that the Sso7d-induced circularisation is very efficient. As a negative control we used the S.solfataricus DNA-binding protein Lrs14 (22), which did not stimulate the formation of circles. This result provides experimental proof of the structural prediction that Sso7d induces bending of DNA molecules in solution; most important, in contrast to the prediction of the above-described model, it shows that the saturating complex behaves as a curved rather than a stiffened molecule. This suggests that the repeated bends induced by multiple protein molecules are not compensatory but rather in phase, i.e. are oriented the same with respect to the interior of the loop.

Figure 1.

Ring-closure assay. Each lane contained 1 ng (0.6 nM) of end-labelled 129 bp DNA fragment. Each pair of lanes shows replicated independent experiments. Lanes 1 and 2, the input fragment; lanes 3 and 4, the fragment incubated with T4 DNA ligase. In the other lanes the fragment was incubated, before ligation, with: lanes 5 and 6, 600 ng (2 µM) Lrs14; lanes 7 and 8, 300 ng (2 µM) Sso7d; lanes 9 and 10, 300 ng (2 µM) HMfA. The protein/DNA ratio was 26 molecules/bp for all proteins.

Sso7d induces linking number reduction of different DNA topoisomers

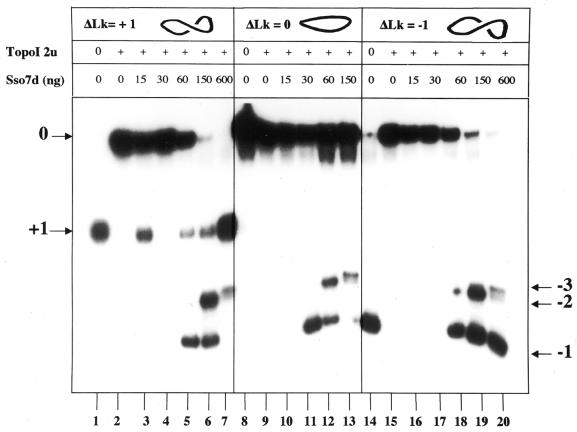

We next addressed the question of negative supercoiling. This activity has been reported for Sso7d and Ssh7 on nicked plasmids in ligase-mediated assays (16,17). We extended this analysis using Topo I assays on DNA minicircles (25). Our approach provides a double advantage with respect to the reported one. First, by exploiting eukaryal DNA Topo I to trap supercoils induced by protein binding, it allows the use of topologically closed substrates. Second, it uses DNA minicircles, which can be obtained of any topology (i.e. relaxed, or negatively or positively supercoiled) and provides a simple system to study protein-induced DNA conformational changes. Using a 371 bp fragment we prepared minicircle DNA topoisomers of ΔLk = +1, 0 and –1, respectively (where Lk is the linking number). After binding with Sso7d, complexes were subjected to Topo I treatment and analysed by non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, allowing for separation of different topoisomers. Topoisomers incubated with Sso7d alone showed no topological change (data not shown); topoisomers treated with Topo I alone were completely relaxed to ΔLk = 0 (Fig. 2, lanes 2, 9 and 15). In contrast, incubation of all topoisomers with increasing amounts of Sso7d followed by Topo I action resulted in production of negative minicircles of ΔLk = –1, –2 and –3 (lanes 5–7, 11–13 and 18–20). The extent of linking number reduction was a function of Sso7d concentration, but not of the input DNA topology; indeed, whatever the starting ΔLk (+1, 0 or –1), the most negative product observed showed ΔLk = –3. This is likely the highest number of superturns that can be introduced in a molecule of this length; indeed, the energy required to introduce a given ΔLk into a DNA circle is inversely proportional to the size of the circle and below 500 bp the energy required to change Lk by one unit is large (29).

Figure 2.

Sso7d induces negative supercoiling of different topoisomers. Lanes 1, 8 and 14, topoisomers +1, 0 and –1 (371 bp), respectively; lanes 2, 9 and 15, topoisomers +1, 0 and –1, respectively, incubated with 2 U Topo I; lanes 3–7, topoisomer +1 complexed with the indicated amounts of Sso7d, incubated with Topo I; lanes 10–13, topoisomer 0 complexed with the indicated amounts of Sso7d, incubated with Topo I; lanes 16–20, topoisomer –1 complexed with the indicated amounts of Sso7d, incubated with Topo I. Each lane contained 0.8 ng DNA. The Sso7d/DNA ratios ranged from 1.8 to 36 molecules/bp. In lane 3 the Topo I reaction was incomplete, leading to persistence of the substrate; repetition of the experiment showed that Sso7d used at 10, 15 or 30 ng had no effect on the +1 minicircle (data not shown). Arrows indicate the position of marker topoisomers. Topoisomers –2 and –3 deviated from the predicted migration (i.e. were slower than topoisomer –1), suggesting a structural departure from the B-form of the double helix that can be induced by negative torsional stress (23).

Sso7d partially inhibited Topo I activity, in particular at high concentration, likely due to competition for the substrate. Similar results were obtained with minicircles of 221 bp (not shown).

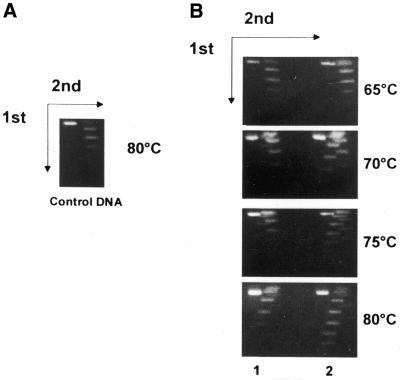

Sso7d induces negative supercoiling under physiological conditions

Having shown that Sso7d induces negative supercoiling of DNA molecules of any topology, we sought to test this activity under experimental conditions as close as possible to those in vivo. To perform incubations at high temperature, we exploited the thermophilic Topo VI (20,30) purified from S.shibatae; moreover, considering the current opinion that DNA is from relaxed to positively supercoiled in hyperthermophiles we chose a mixture of positive and relaxed plasmid topoisomers as substrates (Fig. 3A). We performed topological assays and analysed the reaction products by 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3). Consistent with its known activity, Topo VI was able to relax positive topoisomers to ΔLk = 0 at temperatures ranging from 65 to 75°C (Fig. 3B, lanes 1); at 80°C topoisomers with ΔLk = –1 and –2 were also produced, which correspond to the relaxed state of the plasmid at this temperature (31). Addition of Sso7d (1 molecule/32 bp) induced the formation of negatively supercoiled topoisomers with a maximum ΔLk of –7 (lanes 2). Negative topoisomers were produced more efficiently at higher temperatures, probably reflecting the thermophilicity of Topo VI. This experiment shows that Sso7d induces a Lk reduction under physiological conditions of temperature and DNA topology.

Figure 3.

Sso7d induces negative supercoiling in combination with Topo VI. (A) Relaxed to positively supercoiled pBR322 DNA plasmid incubated at 80°C for 5 min. (B) Relaxed to positively supercoiled pBR322 DNA plasmid incubated with 100 ng purified Topo VI (lanes 1) or the same amount of Topo VI plus 75 ng Sso7d (lanes 2) for 5 min at the indicated temperatures. The Sso7d/DNA ratio was 1 molecule/32 bp. Samples were separated on a 2-dimensional agarose gel as described in Materials and Methods. Under the conditions used negatively supercoiled topoisomers migrate in the left half of each lane and positively supercoiled topoisomers in the right.

Sso7d can compact DNA minicircles

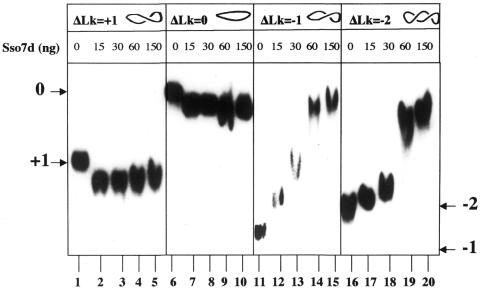

Involvement of proteins of the Sso7d family in DNA packing has been questioned. In EMSAs both Sso7d and Ssh7d failed to induce compaction of linear, nicked and negatively supercoiled molecules (12,17), and in the molecular model of the complex constructed by Krueger et al. (18) Sac7d does not compact linear DNA molecules. However, binding of Sso7d to positive or relaxed DNA molecules has not been studied. We decided, therefore, to perform such an analysis using our minicircles. We used topoisomers showing ΔLk = +1, 0, –1 and –2 [corresponding to torsional stress (σ) values of +0.028, 0, –0.028 and –0.056, respectively] in EMSAs with increasing amounts of Sso7d (Fig. 4). Complexes formed by Sso7d with different topoisomers showed different electrophoretic mobilities: at any DNA/protein ratio used, the two negative topoisomers were retarded (lanes 12–15 and 17–20), whereas both the positive and the relaxed ones were accelerated (lanes 2–5 and 7–10). The electrophoretic behaviour of the protein–DNA complexes was not affected by temperature in the range 25–90°C (not shown). Acceleration of a DNA–protein complex indicates a DNA conformational change resulting in reduction of its hydrodynamic volume, i.e. compaction. By these criteria, positive and relaxed topoisomers were compacted by Sso7d, whereas negative topoisomers were not. We discuss below a possible mechanism to explain these observations (see Discussion).

Figure 4.

Sso7d compacts positive and relaxed topoisomers. Minicircles of the 371 bp fragment were used. Lanes 1–5, topoisomer +1, in the absence (lane 1) and presence of increasing amounts of Sso7d (lanes 2–5); lanes 6–10, topoisomer 0, in the absence (lane 6) and presence of increasing amounts of Sso7d (lanes 7–10); lanes 11–15, topoisomer –1, in the absence (lane 11) and presence of increasing amounts of Sso7d (lanes 12–15); lanes 16–20, topoisomer –2, in the absence (lane 16) and presence of increasing amounts of Sso7d (lanes 17–20). Each lane contained 0.8 ng DNA. The protein/DNA ratios ranged from 1.8 to 18 molecules/bp. Incubation was for 15 min at 37°C. Complexes were separated on non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gels.

Sso7d inhibits reverse gyrase activity

The experiments reported above show that Sso7d in combination with the cutting-religating activity provided by a topoisomerase (Topo I or Topo VI) results in a reaction opposite to that catalysed by the thermophile-specific reverse gyrase enzyme. In an ATP-dependent reaction, reverse gyrase is able to introduce positive superturns into any DNA molecule, producing relaxed/positively supercoiled topoisomers, depending upon the starting topology, the enzyme concentration and the reaction conditions (19).

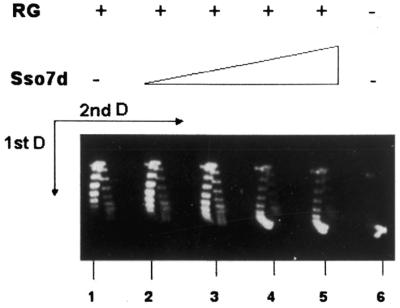

In order to test the effect of Sso7d on reverse gyrase activity, we performed a standard assay using a negatively supercoiled DNA plasmid as substrate (Fig. 5, lane 6). As expected, incubation with reverse gyrase produced relaxed and positively supercoiled molecules (lane 1). Addition of increasing amounts of purified Sso7d progressively inhibited this reaction (lanes 2–5).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of reverse gyrase activity by Sso7d. Samples contained 320 ng pTZ18R plasmid alone (lane 6) or were incubated with 9 U reverse gyrase (lane 1) or 9 U reverse gyrase plus 0.075, 0.15, 0.3 and 0.6 µg Sso7d, respectively (lanes 2–5). The Sso7d/DNA ratios ranged from 1 molecule/48 bp to 1 molecule/6 bp. Incubation was for 20 min at 72°C. Reaction products were separated on a 2-dimensional gel (see legend to Fig. 3). RG, reverse gyrase.

Recently Guagliardi et al. (13) have shown that Sso7d has ATPase activity, raising the possibility that reverse gyrase inhibition might be a consequence of ATP depletion in the reaction. We could rule out this explanation on the basis of the enzymological parameters of the ATP hydrolysis reactions by Sso7d and reverse gyrase. Sso7d hydrolyses ATP with a Km of 0.2 mM and a Vmax of 13.6 pmol Pi released/min/µg at 70°C, and the reaction is linear up to 30 min (13). We calculated that during the 20 min of our reverse gyrase assay the highest amount of Sso7d used would hydrolyse 163 pmol ATP, thus reducing the initial concentration (1 mM) by less than 1%. Reverse gyrase is fully active in the presence of 10 µM ATP (32).

DISCUSSION

To investigate the structural modifications of DNA induced by Sso7d we have performed a number of functional in vitro assays. The most important results of the present study are as follows. (i) Binding of multiple Sso7d molecules to short DNA fragments in solution induces significant curvature and reduces the stiffness/persistence length of the complex. (ii) Sso7d induces negative supercoiling of DNA molecules of any topology (relaxed or positively or negatively supercoiled) under physiological conditions. (iii) Binding of Sso7d induces compaction of positively supercoiled and relaxed DNA molecules, but not of negatively supercoiled ones. (iv) Sso7d inhibits the positive supercoiling activity of reverse gyrase.

Many architectural proteins from organisms of the three domains, including eukaryal and archaeal histones and bacterial HU-like proteins, are able to compact DNA by wrapping it around a protein core. A consequence of this mechanism is that DNA of any conformation (linear, relaxed or supercoiled) can be bent and compacted. In contrast, H-NS of Escherichia coli compacts DNA, inducing DNA looping through protein–protein interactions (33). In both cases concomitant DNA supercoiling is observed. Although we have shown that Sso7d is able to induce DNA bending, negative supercoiling and compaction, several lines of evidence suggest that it follows neither mechanism. Structural data showed that bending by Sac7d and Sso7d is achieved through intercalation of specific amino acids into the DNA minor groove, the same mechanism described for the eukaryotic TATA-binding protein (14,15). In the Sac7d–DNA complex the DNA is not wrapped around the protein, but rather the protein binds the DNA outer surface, and there is no evidence of DNA looping (18). Sso7d, unlike the above-reported proteins, is able to compact relaxed or positively supercoiled DNA, but not negatively supercoiled or linear molecules. Taking into account our data and previous work, we propose the following model that could explain apparently conflicting observations. (To simplify we will assume that Sso7d, Sac7d and other members are all functionally equivalent.) These proteins unwind DNA, increasing the helical periodicity (14,15). In a topologically closed DNA molecule, reduction of Tw (where Tw is the helical twist) must be compensated by a positive Wr (where Wr is the writhe) and/or ΔTw elsewhere in the molecule (to meet the equation Lk = Tw + Wr), as long as the protein is bound. The effects of Tw and Wr variations can be analysed using different assays. In topology assays these compensatory distortions are relaxed by a topoisomerase, with a corresponding Lk reduction. Indeed, in our Topo I and Topo VI experiments Sso7d induced an Lk reduction of any type of topologically closed DNA molecules. On the other hand, the effects of a Wr increase on the geometry of constrained DNA, analysed by EMSA, depend on its topology: a Wr increase will compact positive and relaxed molecules, while it will relax and decompact negative ones. We therefore suggest that the observed compaction of positive and relaxed minicircles is a geometrical consequence of the unwinding activity of Sso7d, and can only be appreciated when DNA is topologically constrained. Retardation of complexes formed with negative topoisomers is likely the result of two factors: an increase in the frictional coefficient due to protein mass/charge, and relaxation. A similar compaction mechanism has been hypothesised for the architectural protein MC1 of Methanosarcina spp. (34); Sso7d and MC1, although not related in sequence, might be functionally analogous in organising and maintaining chromatin structure in the absence of histones.

Whatever the mechanism, the observed effects of Sso7d on DNA structure may have biological relevance. We have shown that Sso7d is able to compact DNA substrates with σ values ranging between 0 and +0.028. Interestingly, σ values of various plasmids of Sulfolobales have been found within this range (3), suggesting that, at least in principle, Sso7d has the potential to induce DNA compaction in vivo. Moreover, the Topo VI experiment shows that Sso7d induces an Lk reduction under conditions mimicking those in vivo, i.e. with complex positive/relaxed substrates, at high temperatures and in cooperation with the endogenous thermophilic topoisomerase Topo VI.

Although positive supercoiling has been associated with life at high temperature, hyperthermophilic organisms also require specific mechanisms able to introduce negative supercoiling. This assumption is supported by several lines of evidence: first, hyperthermophilic Eubacteria (7), and possibly also some Archaea (35), contain gyrase, an enzyme which introduces negative superturns; second, plasmid DNA is found negatively supercoiled in Thermotoga and Archaeoglobus (7,36) and, moreover, a rapid reduction in plasmid Lk takes place in Sulfolobus and Thermococcus during cold shock (3). In hyperthermophilic Eubacteria such function is fulfilled by DNA gyrase, whereas hyperthermophilic Euryarchaea possess canonical histones. In the Crenarchaeon Sulfolobus, which lacks both histones and gyrase, cooperation between the Sso7d and Topo VI activities might be used in vivo to induce negative supercoiling.

We have shown that Sso7d inhibits reverse gyrase activity, suggesting that Sso7d action might counteract the overwinding effect of the enzyme. Further experiments are required to understand the mechanism of this inhibition. Simple explanations are that Sso7d limits DNA accessibility to the enzyme or stabilises the double helix to the reverse gyrase-induced unwinding. Recently Sso7d has been reported to inhibit the cutting activity of the Holliday junction-resolving enzyme Hjc by competition for the substrate (37). However, we cannot rule out an active antagonism between the positive supercoiling activity of reverse gyrase and the negative supercoiling activity of Sso7d.

It will be interesting to investigate the interplay between proteins of the Sso7d family and other factors potentially implicated in control of DNA conformation and packing, such as the abundant DNA-binding proteins of the Sso10b family (38) and Smj12, a protein identified in S.solfataricus with positive supercoiling activity (39).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Dave Musgrave for the generous gift of HMfA and to Giovanni Imperato and Ottavio Piedimonte for technical assistance. A.N. was awarded a Marie Curie EC fellowship to visit the laboratory of P.F. This work was partially supported by the EC project ‘Extremophiles as cell factories’ and by the CNR Special Program ‘Biomolecole per la salute umana’.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lopez-Garcia P. (1999) DNA supercoiling and temperature adaptation: a clue to early diversification of life? J. Mol. Evol., 49, 439–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charbonnier F. and Forterre,P. (1994) Comparison of plasmid DNA topology among mesophilic and thermophilic eubacteria and archaebacteria. J. Bacteriol., 176, 1251–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez-Garcia P. and Forterre,P. (1997) DNA topology in hyperthermophilic Archaea: reference states and their variation with growth phase, growth temperature and temperature stresses. Mol. Microbiol., 23, 1267–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duguet M. (1995) Reverse gyrase. In Eckstein,F. and Lilley,D.M.J. (eds), Nucleic Acids and Molecular Biology. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany, Vol. IX, pp. 84–114.

- 5.Forterre P., Bergerat,A. and Lopez-Garcia,P. (1996) The unique DNA topology and DNA topoisomerases of hyperthermophilic Archaea. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 18, 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forterre P., Boutier de la Tour,C., Philippe,H. and Duguet,M. (2000) Reverse gyrase from hyperthermophiles, probable transfer of a thermoadaptation trait from Archaea to Bacteria. Trends Genet., 16, 152–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guipaud O., Marguet,E., Noll,K., Bouthier de la Tour,C.B. and Forterre,P. (1997) Both DNA gyrase and reverse gyrase are present in the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 10606–10611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandman K. and Reeve,J.N. (2000) Structure and functional relationships of archaeal and eukaryal histones and nucleosomes. Arch. Microbiol., 17, 165–169. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Reeve J.N., Sandman,K. and Daniels,C.J. (1997) Archaeal histones, nucleosomes and transcription initiation. Cell, 89, 999–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musgrave D.M., Forterre,P. and Slesarev,A. (2000) Negative constrained DNA supercoiling in archaeal nucleosomes. Mol. Microbiol., 35, 341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumann H., Knapp,S., Lundback,T., Ladenstein,R. and Hard,T. (1994) Solution structure and DNA-binding properties of a small thermostable protein from the Archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Nature Struct. Biol., 1, 808–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guagliardi A., Napoli,A., Rossi,M. and Ciaramella,M. (1997) Annealing of complementary DNA strands above the melting point of the duplex promoted by an archaeal protein. J. Mol. Biol., 267, 841–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guagliardi A., Cerchia,L., Moracci,M. and Rossi,M. (2000) The chromosomal protein Sso7d of the Crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus rescues aggregated proteins in an ATP hydrolysis-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 31813–31818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agback P., Baumann,H., Knapp,S., Ladenstein,R. and Hard,T. (1998) Architecture of nonspecific protein–DNA interactions in the Sso7d–DNA complex. Nature Struct. Biol., 5, 579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson H., Gao,Y.G., McCrary,B.S., Edmondson,S.P., Shriver,J.W. and Wang,A.H.J. (1998) The hyperthermophile chromosomal protein Sac7d sharply kinks DNA. Nature, 392, 202–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez-Garcia P., Knapp,S., Ladenstein,R. and Forterre,P. (1998) In vitro DNA binding of the archaeal protein Sso7d induces negative supercoiling at temperatures typical for thermophilic growth. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 2322–2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mai V.Q., Chen,X., Hong,R. and Huang,L. (1998) Small abundant DNA binding proteins from the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus shibatae constrain negative DNA supercoils. J. Bacteriol., 180, 2560–2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krueger J.K., McCrary,B.S., Wang,A.H., Shriver,J.W., Trewhella,J. and Edmondson,S.P. (1999) The solution structure of the Sac7d/DNA complex: a small-angle X-ray scattering study. Biochemistry, 38, 10247–10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadal M., Couderc,E., Duguet,M. and Jaxel,C. (1994) Purification and characterization of reverse gyrase from Sulfolobus shibatae. Its proteolytic product appears as an ATP-independent topoisomerase. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buhler C., Gadelle,D., Forterre,P., Wang,J.C. and Bergerat,A. (1998) Reconstitution of DNA topoisomerase VI of the thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus shibatae from subunits separately overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 5157–5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guagliardi A., Cerchia,L., De Rosa,M., Rossi,M. and Bartolucci,S. (1992) Isolation of a thermostable enzyme catalyzing disulfide bond formation from the archaebacterium Sulfolobus solfataricus. FEBS Lett., 303, 27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Napoli A., van der Oost,J., Sensen,C.W., Charlebois,R.L., Rossi,M. and Ciaramella,M. (1999) An Lrp-like protein of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus which binds to its own promoter. J. Bacteriol., 181, 1474–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goulet I., Zivanovic,Y. and Prunell,A. (1987) Helical repeat of DNA in solution. The V curve method. Nucleic Acids Res., 15, 2803–2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zivanovic Y., Goulet,I. and Prunell,A. (1986) Properties of supercoiled DNA in gel-electrophoresis. The V-like dependence of mobility on topological constraint. DNA–matrix interactions. J. Mol. Biol., 192, 645–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zivanovic Y., Duband-Goulet,I., Shultz,P., Stofer,E., Oudet,P. and Prunell,A. (1990) Chromatin reconstitution on small DNA rings. III. Histone H5 dependence of DNA supercoiling in the nucleosome. J. Mol. Biol., 214, 479–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Storl K., Burckhardt,G., Lown,J.W. and Zimmer,C. (1993) Studies on the ability of minor groove binders to induce supercoiling in DNA. FEBS Lett., 334, 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodges-Garcia Y., Hagerman,P.J. and Pettijohn,D.E. (1989) DNA ring closure mediated by protein HU. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 14621–14623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey K.A., Chow,C.S. and Reeve,J.N. (1999) Histone stoichiometry and DNA circularization in archaeal nucleosomes. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 532–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shore D. and Baldwin,R.L. (1983) Energetics of DNA twisting. II. Topoisomer analysis. J. Mol. Biol., 170, 983–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergerat A., de Massy,B., Gadelle,D., Varoutas,P.C., Nicolas,A. and Forterre,P. (1997) An atypical topoisomerase II from Archaea with implications for meiotic recombination. Nature, 386, 414–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duguet M. (1993) The helical repeat of DNA at high temperature. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forterre P., Mirambeau,G., Jaxel,C., Nadal,M. and Duguet,M. (1985) High positive supercoiling in vitro catalyzed by an ATP and polyethylene glycol-stimulated topoisomerase from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. EMBO J., 4, 2123–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dame R.T., Wyman,C. and Goosen,N. (2000) H-NS mediated compaction of DNA visualised by atomic force microscopy. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 3504–3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teyssier C., Toulmé,F., Touzel,J.-P., Gervais,A., Maurizot,J.-C and Culard,F. (1996) Preferential binding of the archaebacterial histone-like MC1 protein to negatively supercoiled DNA minicircles. Biochemistry, 35, 7954–7958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klenk H.-P., Clayton,R.A., Tomb,J.-F., White,O., Nelson,K.E., Ketchum,K.A., Dodson,R.J., Gwinn,M., Hickey,E.K., Peterson,J.D. et al. (1997) The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature, 390, 364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopez-Garcia P., Forterre.P., van der Oost,J. and Erauso,G. (2000) Plasmid pGS5 from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Archaeoglobus profundus is negatively supercoiled. J. Bacteriol., 182, 4998–5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kvaratskhelia M., Wardleworth,B.N., Bond,C.S., Fogg,J.M., Lilley,D.M. and White,M.F. (2002) Holliday junction resolution is modulated by archaeal chromatin components in vitro. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 2992–2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xue H., Guo,R., Wen,Y., Liu,D. and Huang,L. (2000) An abundant DNA binding protein from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus shibatae affects DNA supercoiling in a temperature-dependent fashion J. Bacteriol., 182, 3929–3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Napoli A., Kvaratskelia,M., White,M.F., Rossi,M. and Ciaramella,M. (2001) A novel member of the bacterial-archaeal regulator family is a non-specific DNA-binding protein and induces positive supercoiling. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 10745–10752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]