Abstract

Background:

Most patients undergoing breast surgery with free nipple grafts lose nipple erection (NE) function. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of nerve preservation and reconstruction with targeted nipple–areola complex reinnervation (TNR) on NE following gender-affirming mastectomy with free nipple grafting.

Methods:

Patients undergoing gender-affirming mastectomy with free nipple grafts were prospectively enrolled. Subjects who underwent TNR were compared with controls who did not undergo TNR. Postoperative patient-reported NE function was scored using a 4-point Likert scale. Objective NE evaluation consisted of the change in areola circumference and nipple height following cold application using a thermal device and 3-dimensional imaging.

Results:

Twenty patients (11 subjects and 9 controls) with comparable age, body mass index, and mastectomy weight were included. At an average follow-up of 16.8 (±7.0) months, significantly more subjects reported NE than controls (72.8% versus 38.9%, P = 0.03), with a higher median NE score (3 [range 1–4] versus 1 [range 1–2], P = 0.0005). Following cold application, subjects had a greater mean reduction in areola circumference (−4.16 ± 3.3 versus −1.67 ± 1.9 mm, P = 0.02) and a greater mean increase in nipple height (+0.86 ± 0.8 versus +0.37±0.3 mm, P = 0.04) compared with controls. Improved patient-reported NE function correlated with better cold detection thresholds (P = 0.01).

Conclusions:

TNR was associated with improved patient-reported and objective NE following gender-affirming mastectomy. Improved NE correlated with improved cold detection, suggesting the role of both sensory and autonomic innervation in mediating NE.

Takeaways

Question: Most patients undergoing breast surgery with free nipple grafts lose nipple erection function. This study evaluated the effect of targeted nipple-areola complex reinnervation (TNR) on nipple erection function of free nipple grafts following gender-affirming mastectomy.

Findings: Among 20 patients who underwent gender-affirming mastectomy, those who underwent TNR had significantly higher patient-reported nipple erection scores as well as objective reductions in areola circumference and increase in nipple height on 3-dimensional imaging as compared with controls who did not undergo TNR. Improved cold detection was associated with better nipple erection.

Meaning: TNR improved patient-reported and objective nipple erection of free nipple grafts.

INTRODUCTION

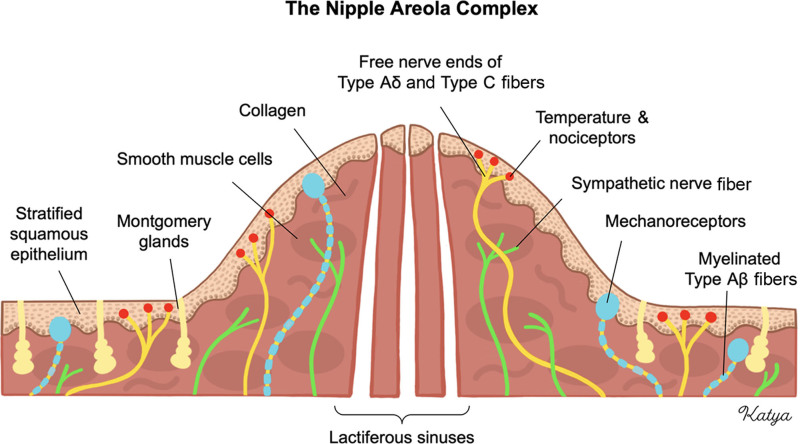

The nipple-areola complex (NAC) is a highly specialized tissue of the mammary gland.1 A stratified squamous epithelium overlies a dermis containing abundant circular smooth muscle fibers.2 The NAC is extensively innervated by lateral and medial cutaneous branches of the third to fifth intercostal nerves.3 Numerous sensory receptors are distributed throughout the epidermis and dermis, and their signals are processed by large myelinated (type Aβ) and small thinly myelinated (type Aδ) or small unmyelinated (type C) afferent sensory nerve fibers.4,5 Conversely, autonomic functions of the NAC are regulated by efferent sympathetic fibers innervating structures such as smooth muscle cells and glands.6–8 There is no evidence of parasympathetic regulation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The NAC and its sensory and autonomic innervation. Sensory innervation is governed by large, myelinated fibers (type Aβ) for mechanoception, as well as small, thinly myelinated or unmyelinated fibers (type Aδ and type C) for temperature and nociception. Autonomic functions are governed by unmyelinated sympathetic nerve fibers that innervate smooth muscle cells and glands.

NAC erection (NE) is a unique physiological response to cold sensation and mechanical stimulation, as well as emotional and sexual arousal. During NE, the nipple becomes prominent, whereas the areola reduces in size. Although NE likely involves a combination of neural, muscular, and vascular phenomena, the underlying mechanisms have been minimally studied and remain largely unknown. Previous studies have mainly suggested NE to be a result of sympathetic stimulation of smooth muscle fiber contraction.8,9 Other mechanisms such as nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation also seem to be involved.10,11 Some authors have suggested the role of local mechanisms independent of sensory or autonomic innervation by the intercostal nerves.12

Free nipple grafting is commonly performed in various breast procedures, including breast reconstruction; gender-affirming mastectomy; gynecomastia mastectomy; and occasionally, breast reduction surgery. Free nipple grafting involves harvesting the native NAC as a skin graft and then transplanting it to a new location on the breast or chest. However, most patients undergoing free nipple grafting experience long-term loss of NE function.13–15 Previous studies have shown that loss of normal nipple appearance and function following free nipple grafting is associated with reduced surgical outcomes and diminished patient satisfaction and acceptance of body image.16,17

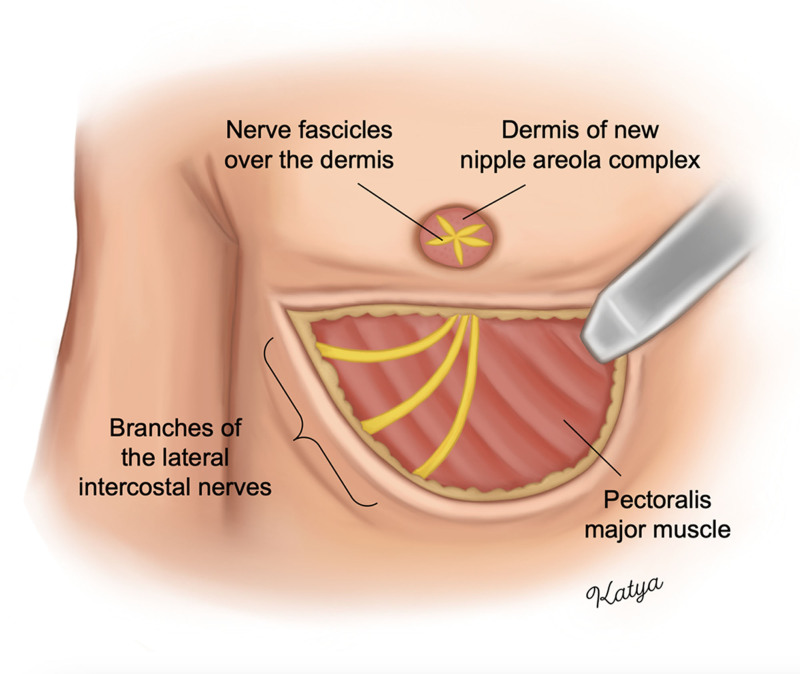

Targeted NAC reinnervation (TNR) is a technique that aims to preserve and reconstruct the lateral intercostal nerves to the NAC during breast or chest surgery.18,19 TNR is performed through either direct coaptation or the use of a nerve allograft or autograft depending on whether the intercostal nerves can be preserved in sufficient length to directly reach the NAC (Fig. 2). Previous prospective studies have shown that subjects undergoing TNR during gender-affirming mastectomy with free nipple grafting had improved quantitative and patient-reported sensation to light touch, pressure, temperature, and erogenous sensation as compared with control patients who did not undergo TNR.20,21 Interestingly, subjects in that study also reported improved NE function; however, NE was not analyzed objectively.21

Fig. 2.

TNR during double incision gender-affirming mastectomy with free nipple grafting. Branches of the third through fifth lateral intercostal nerves are preserved to their distal length. If the nerves cannot directly reach the NAC, a nerve allograft or autograft is used. The distal nerve ends are passed through the superior skin flap into the deepithelialized area of the new NAC. The nerve fascicles are split, fanned out, and sutured over the dermis of the new NAC. The free nipple graft is then placed over the new NAC and nerve fascicles.

Given the current lack in our understanding of the mechanisms mediating NE and the importance of restoring NAC function to improve breast surgery outcomes, this study aimed to evaluate the effect of TNR on both patient-reported and objective NE function of free nipple grafts following gender-affirming mastectomy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This prospective cohort study obtained institutional review board approval at the Massachusetts General Hospital (2021-P002932). Consecutive patients undergoing double incision gender-affirming mastectomy with free nipple grafting between 2021 and 2023 were prospectively enrolled. Patients were offered the possibility to undergo TNR during their preoperative consultation.

TNR was performed as previously described.18 The free nipple grafting dimensions ranged from 2.0 to 2.5 cm in height and width and were thinned to preserve the dermis. Nerve allografts (Axogen, Jacksonville, FL) were used if the intercostal nerve branches could not reach the NAC directly. The cost associated with the use of a nerve allograft is between 2000 and 5000 US dollars. All cases were covered by insurance. Exclusion criteria included age younger than 18 years, previous breast or chest surgery, diabetes, neurological or peripheral nerve disorders, and postoperative complications (free nipple graft necrosis, hematoma, seroma, and wound dehiscence).

Patient evaluation was performed in a quiet and temperature-controlled clinic room. Patient-reported NE was evaluated using the following question: “Has your nipple conserved the ability to become erect (such as when you are feeling cold or during erogenous sensation)?” and patients responded using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little bit, 3 = quite a bit, and 4 = a lot). Results were recorded in REDCap (version 8.1.20; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN).

Patients then underwent objective evaluation of NE function by measuring the change in areola circumference and nipple height with cold application to the free nipple grafts. Three-dimensional (3D) imaging of the chest was obtained before and after cold application using VECTRA XT 3D Imaging System (Canfield Scientific, Inc., Fairfield, NK). Cold was applied using a thermal sensory testing device with a 1.5 × 1.5 cm contact area probe (TSA2, MEDOC, Israel). The probe gradually cooled down to 0°C from a baseline temperature of 32°C at a rate of −1°C/s. Patients were asked to report when they started to feel cold, and the corresponding temperature was recorded as their cold detection threshold.

Images were analyzed using the VECTRA Analysis Module software. After being registered to a 3D-axis grid, each patient’s pre- and post-cold images were registered to each other using specific landmarks. Areola circumference was measured using the “closed-loop” function, whereas nipple height was measured using the “straight line across” function.

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We described continuous variables using means and SDs, or median and range or interquartile range, depending on normality. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. Comparative analyses were conducted using Student t tests. A value of P less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 20 patients who underwent double incision gender-affirming mastectomy with free nipple grafting were included, resulting in a total of 40 free nipple grafts that were evaluated. There were 11 subjects who underwent TNR and 9 control patients who did not undergo TNR. The mean age of the study population was 23.9 years (±5.4 y), the mean body mass index (BMI) was 26.2 kg/m2 (±5.0 kg/m2), and the mean mastectomy weight was 547.7 g (±279.9 g). The mean age, BMI, and mastectomy weight were statistically comparable between subjects and controls (P > 0.05). See Table 1 for patient demographics.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Variable | Total (n = 20) | Subjects (n = 11) | Controls (n = 9) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 23.9 (5.4) | 23.9 (5.8) | 23.8 (5.2) | 0.96 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 26.2 (5.0) | 26.6 (3.1) | 25.8 (5.2) | 0.23 |

| Mastectomy weight, g, mean (SD) | 547.7 (297.9) | 536.2 (279.1) | 557.3 (279.1) | 0.83 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.51 | |||

| White | 17 (85.0) | 10 (90.9) | 7 (77.8) | — |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (10.0) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (11.1) | — |

| Black | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | — |

*Statistical significance with a P value < 0.05.

In patients who underwent TNR, the mean number of intercostal nerve branches that were coapted to the NAC was 2.6 (±0.5). Nerves were directly coaptated to the NAC without the use of an allograft in 12 (54.5%) mastectomies, with an allograft in 8 (36.4%) mastectomies, and with a combination of direct coaptation and allograft in 2 (9.1%) mastectomies. The mean allograft length was 2.8 cm (±1.0 cm). See Table 2 for TNR characteristics.

Table 2.

TNR Characteristics

| Variable | Total Reinnervated Free Nipple Grafts (n = 22) |

|---|---|

| Technique | |

| Direct coaptation only, n (%) | 12 (54.5) |

| Allograft only, n (%) | 8 (36.4) |

| Direct coaptation and allograft, n (%) | 2 (9.1) |

| No. reconstructed nerves, n, mean (SD) | 2.6 (0.5) |

| Allograft length, cm, mean (SD) | 2.8 (1.0) |

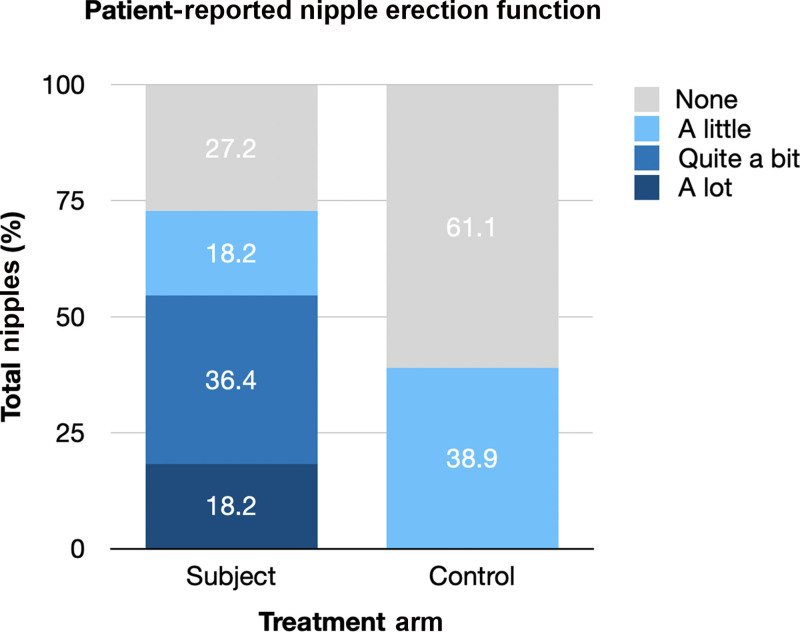

Evaluation of patient-reported and objective NE function was performed at an average follow-up of 16.80 (±7.0) months and the average follow-up was similar between subjects and control patients (17.82 ± 6.2 versus 15.56 ± 8.0 months, P = 0.32). Significantly more subjects reported any degree of NE function as compared with control patients (72.8% versus 38.9%, P = 0.03), and subjects had a significantly higher median NE function score (3 [range 1–4] versus 1 [range 1–2], P = 0.0005). In subjects, “a lot” (score 4 of 4) of NE function was reported in 4 (18.2%) cases, “quite a bit” (score 3 of 4) in 8 (21.1%), “a little bit” (score 2 of 4) in 4 (18.2%), and “none” (score 1 of 4) in 6 (27.3%). In controls patients, a lot (score 4 of 4) of NE function was reported in 0 (0.0%) cases, quite a bit (score 3 of 4) in 0 (0.0%), a little bit (score 2 of 4) in 7 (38.9%), and none (score 1 of 4) in 11 (61.1%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Patient-reported NE function was scored using a 4-point Likert scale (1= none, 2 = a little, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = a lot). Significantly more subjects who underwent TNR reported any NE function as compared with control patients who did not undergo TNR (72.8% vs 38.9%, P < 0.01).

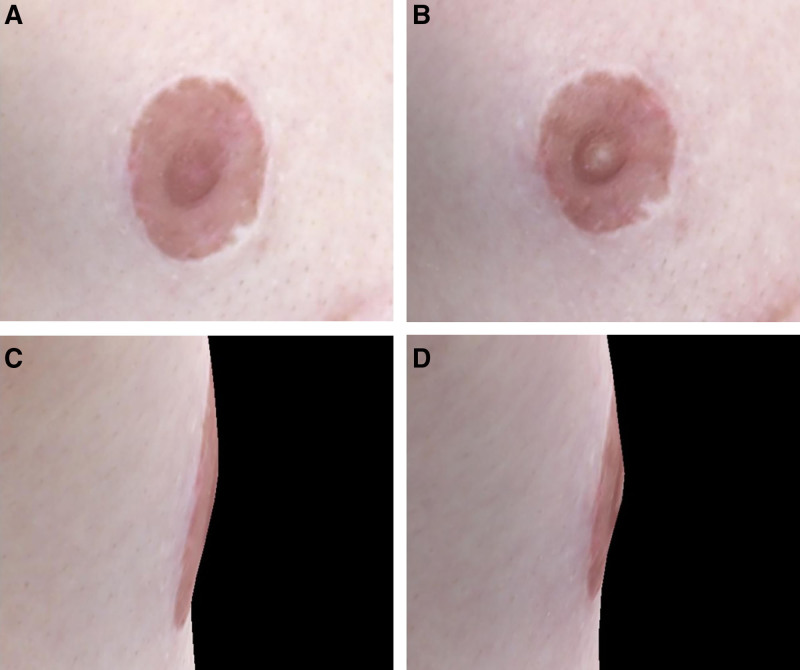

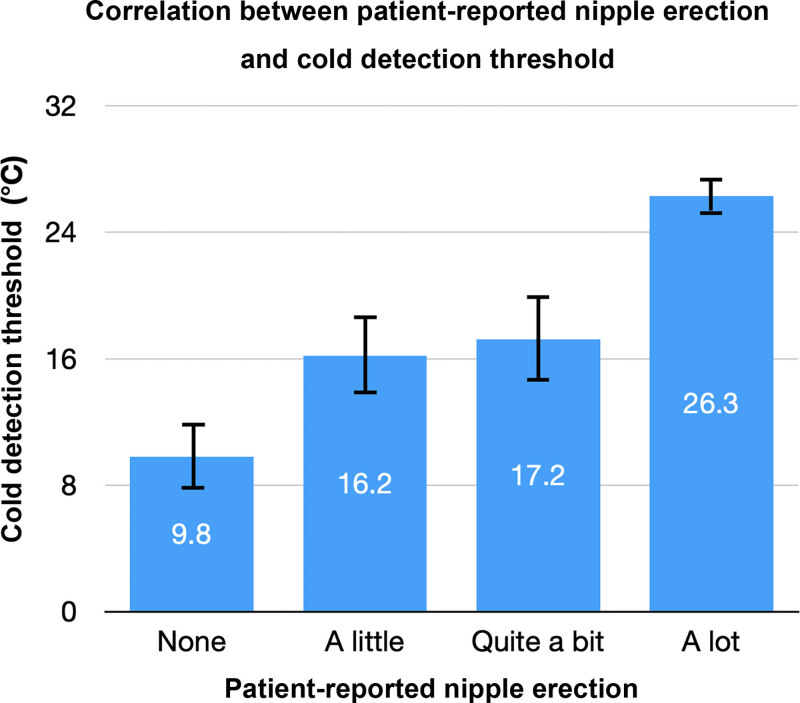

Before cold application, the average baseline areola circumference of the free nipple graft was 73.9 mm (±9.4 mm) and the average nipple height was 4.5 mm (±1.3 mm), and both were similar between subjects and control patients (P > 0.05). Following cold application to the free nipple graft, patients had a significantly greater mean reduction in areola circumference as compared with controls (−4.16 ± 3.3 versus −1.67 ± 1.9 mm, P = 0.02), and a significantly greater mean increase in nipple height (+0.86 ± 0.8 versus +0.37 ± 0.3 mm, P = 0.04). Patients started to feel cold sooner than control patients (mean cold detection threshold 21.25°C ± 7.3°C versus 10.92°C ± 3.0°C, P = 0.001) (see Table 3 and Fig. 4). Patient-reported NE function score was significantly correlated with cold detection threshold (P = 0.01) (Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Mean Change in Areola Circumference and Nipple Height Measurements Before and After Cold Application to the Free Nipple Grafts

| Variable, Mean (SD) | Total (n = 38) | Subjects (n = 22) | Controls (n = 18) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in areola circumference, mm | −2.87 (2.9) | −4.16 (3.3) | −1.67 (1.9) | 0.02* |

| Change in nipple height, mm | +0.59 (0.6) | +0.86 (0.8) | +0.37 (0.3) | 0.04* |

| Cold detection threshold, °C | 17.81 (7.8) | 21.25 (7.3) | 10.92 (3.0) | 0.001* |

| Follow-up, mo | 16.80 (7.0) | 17.82 (6.2) | 15.56 (8.0) | 0.32 |

Statistical significance with a P value >0.05.

Fig. 4.

This is a case of a 21-year-old trans male patient 22 months status post double incision gender-affirming mastectomy with free nipple grafting. The patient reported “quite a bit” (score 3 of 4) of NE function. Following cold application to the right free nipple graft, the areola circumference reduced from 81.76 to 74.07 mm (−7.69 mm), as shown in (A) and (B), whereas the nipple height increased from 2.46 to 5.32 mm (+2.86 mm), as shown in (C) and (D).

Fig. 5.

Improved patient-reported NE function was significantly correlated with improved mean cold detection threshold (P = 0.01). Patient-reported NE was scored using a 4-point Likert scale (1= none, 2 = a little, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = a lot).

TNR through direct coaptation did not result in improved patient-reported or objective NE or cold detection compared with the use of nerve allograft (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the effect of nerve preservation and reconstruction with TNR on NE function of free nipple grafts in patients undergoing gender-affirming mastectomy. We found that patients who underwent TNR had significantly improved patient-reported and objective NE function compared to control patients who did not undergo TNR.

In terms of patient-reported outcomes, approximately 70% of patients who underwent TNR reported NE, including nearly 20% reporting a lot of function (score 4 of 4). This was significantly more than control patients, where most patients reported no NE function (score 0 of 0) and 40% reported a little NE (score 2 of 4). These findings are similar to those of a previous study finding that 42% of patients undergoing breast reconstruction with free nipple grafting without reinnervation reported NE function.13 Our patient-reported findings were supported by objective measurements showing greater areola contraction and greater nipple projection in patients who underwent TNR as compared with those who did not. These results suggest that TNR may effectively improve NE function following breast surgery involving free nipple grafting.

The underlying physiological mechanisms of NE remain incompletely understood.9,10 Our study found that greater NE function was correlated with improved cold detection, suggesting the importance of both afferent sensory and efferent autonomic sympathetic functions in mediating NE in response to local cold application. Interestingly, one case report described a patient who underwent autologous breast reconstruction with free nipple grafting with preserved NE function 2 weeks postoperatively.12 This patient had objective NE in response to cold and tactile stimuli, but not sexual arousal, and with absent NAC sensation.12 The authors of that report suggested that local factors were responsible in mediating NE given that NE was already observed shortly following the surgery, and given the absence of sensory function. Although it is possible that local factors may play a role in mediating NE, our study suggests an important contribution of both sensory and autonomic innervation provided by the intercostal nerves.

Furthermore, we found that direct coaptation of nerves to the NAC versus the use of allograft did not influence long-term NE function and cold detection thresholds. Although direct coaptation may allow for earlier restoration of nerve-mediated functions as compared with the use of allograft, long-term outcomes may be similar, likely due to the relatively short allograft lengths needed in this patient population.

Given that loss of normal nipple function following free nipple grafting has been shown to be associated with reduced patient satisfaction and acceptance of body image, improving NE function and sensation with TNR may improve postoperative outcomes.16,17

Patients undergoing gender-affirming mastectomy with TNR are counseled on the possibility of requiring a nerve allograft if the intercostal nerves cannot be preserved in sufficient length to reach the new NAC directly. They are also informed of the additional 30–60 minutes of operative time.22 Expected outcomes, including restoration of NAC and chest sensation typically beginning 3–6 months postoperatively, are discussed. Patients are also counseled on the risk of transient nipple hypersensitivity until 3 months postoperatively.20

The limitations of this study mainly included its small sample size and that subjects were not blinded or randomized to the reinnervation intervention. Furthermore, the evaluation of NE function preoperatively and then postoperatively at multiple follow-ups, or at least at the same follow-up period in all patients, would have provided additional information. Moreover, although age, BMI, and mastectomy were statistically comparable between both study groups, other variables which may have influenced outcomes were not analyzed, including preoperative NAC size and surgeon experience and technique. Furthermore, patient-reported NE function did not distinguish NE in the context of cold sensation versus erogenous sensation, and objective NE function was only measured in the context of cold exposure. Finally, we did not evaluate patient preoperative concern for NE function to understand the importance of preserving this function in patients undergoing gender-affirming mastectomy. Future studies should aim to stratify NE function based on different stimuli.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, intercostal nerve preservation and reconstruction with TNR during gender-affirming mastectomy with free nipple grafting was associated with improved postoperative patient-reported and objective NE function. Additionally, greater NE function correlated with improved cold detection thresholds. These findings suggest the importance of both afferent sensory and efferent autonomic intercostal nerve fiber functions in mediating NE and suggest the effectiveness of TNR in improving NE following breast surgery involving free nipple grafts.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Valerio is a consultant for Axogen, Integra Lifesciences, and Checkpoint Surgical. Dr. Gfrerer is a consultant for Biocircuit. Dr. Austen Jr. is a consultant for and receives royalties from Sientra, Cytrellis, and Durvena. Dr. Carruthers is a consultant for Tela Bio. The other authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Published online 13 January 2025.

Disclosure statements are at the end of this article, following the correspondence information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stone K, Wheeler A. A review of anatomy, physiology, and benign pathology of the nipple. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3236–3240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koyama S, Wu H-J, Easwaran T, et al. The nipple: a simple intersection of mammary gland and integument, but focal point of organ function. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2013;18:121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smeele HP, Bijkerk E, van Kuijk SMJ, et al. Innervation of the female breast and nipple: a systematic review and meta-analysis of anatomical dissection studies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;150:243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misery L, Talagas M. Innervation of the male breast: psychological and physiological consequences. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2017;22:109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gadhvi M, Moore MJ, Waseem M. Physiology, sensory system. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eriksson M, Lindh B, Uvnäs-Moberg K, et al. Distribution and origin of peptide-containing nerve fibres in the rat and human mammary gland. Neuroscience. 1996;70:227–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franke-Radowiecka A, Kaleczyc J, Klimczuk M, et al. Noradrenergic and peptidergic innervation of the mammary gland in the immature pig. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2002;40:17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCorry LK. Physiology of the autonomic nervous system. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furlan A, La Manno G, Lübke M, et al. Visceral motor neuron diversity delineates a cellular basis for nipple- and pilo-erection muscle control. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1331–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tezer M, Ozluk Y, Sanli O, et al. Nitric oxide may mediate nipple erection. J Androl. 2012;33:805–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacasse P, Farr VC, Davis SR, et al. Local secretion of nitric oxide and the control of mammary blood flow. J Dairy Sci. 1996;79:1369–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Vrij EL, van der Lei B, Huijing MA. Preserved nipple erectile function after free nipple areolar complex transplantation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2019;72:1700–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zenn MR, Garofalo JA. Unilateral nipple reconstruction with nipple sharing: time for a second look. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1648–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knox ADC, Ho AL, Leung L, et al. A review of 101 consecutive subcutaneous mastectomies and male chest contouring using the concentric circular and free nipple graft techniques in female-to-male transgender patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:1260e–1272e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shridharani SM, Magarakis M, Stapleton SM, et al. Breast sensation after breast reconstruction: a systematic review. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2010;26:303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans KK, Rasko Y, Lenert J, et al. The use of calcium hydroxylapatite for nipple projection after failed nipple-areolar reconstruction: early results. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:25–29; discussion 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wellisch DK, Schain WS, Noone RB, et al. The psychological contribution of nipple addition in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gfrerer L, Winograd JM, Austen WG, Jr, et al. Targeted nipple areola complex reinnervation in gender-affirming double incision mastectomy with free nipple grafting. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10:e4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gfrerer L, Sager JE, Ford OA, et al. Targeted nipple areola complex reinnervation: technical considerations and surgical efficiency in implant-based breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10:e4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Remy K, Packowski K, Alston C, et al. Prospective sensory outcomes for targeted nipple areola complex reinnervation (TNR) in gender-affirming double incision mastectomy with free nipple grafting. Ann Surg. 2024. [E-pub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Remy K, Alston C, Gonzales E, et al. Association of targeted reinnervation during gender-affirming mastectomy and restoration of sensation. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2446782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das RK, Remy K, McCarty JC, et al. A relative value unit-based model for targeted nipple-areola complex neurotization in gender-affirming mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:e5605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]