Abstract

Hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome (HIGES) is a rare immunodeficiency characterized by high levels of immunoglobulin E (IgE) in the setting of various clinical features such as cutaneous candidiasis, asthma, recurrent rashes, and fungal infections. This case describes a 70-year-old male with cachexia and dyspnea found to have a cavitary lesion and aspergilloma, with remarkably high IgE and positive 1,3-β-D-glucan and Aspergillus testing. Herein, we describe the aforementioned case, review the available literature, and hypothesize the connection between invasive fungal infections and HIGES. We hope this discussion helps highlight the importance of a broad differential in chronic dyspnea, including infectious etiologies, and allows for a better understanding of immunologic labs in the setting of fungal infections.

1. Background

Hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome (HIGES) is a rare primary immunodeficiency characterized by recurrent pulmonary infections, recurrent rashes, eosinophilia, and elevated immunoglobulin E (IgE) [1]. While mostly sporadic in onset, both autosomal dominant and recessive forms have been identified, with the most common genetic culprit the loss-of-function mutations in STAT3 [2]. DOCK8 is a less commonly implicated gene associated with vasculitic disease and increased malignancy risk [3]. Typically, HIGES presents in infancy with recurrent skin and pulmonary infections, but surprisingly, most genetic variations are not associated with other atopic symptoms such as food allergies, wheezing, allergic rhinitis, or anaphylaxis [4]. These hyper IgE syndromes are mediated by their predisposing genetic mutations, causing an array of phenotypes. HIGES are associated with variably high levels of serum IgE. IgE levels often peak around 2000 IU/mL, fluctuate, and decrease into adulthood. Peripheral eosinophilia can also be implicated in HIGES [4]. Currently, treatment for HIGES remains largely supportive and focused on the prevention of severe systemic disease. Prophylactic options include TMP-SMX, IVIG, TNF-alpha, voriconazole, and compliance with vaccination schedules.

2. Case report

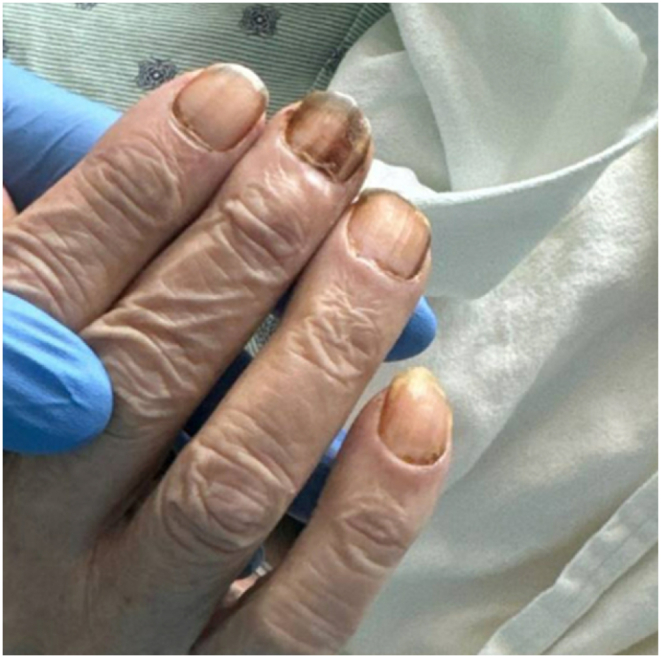

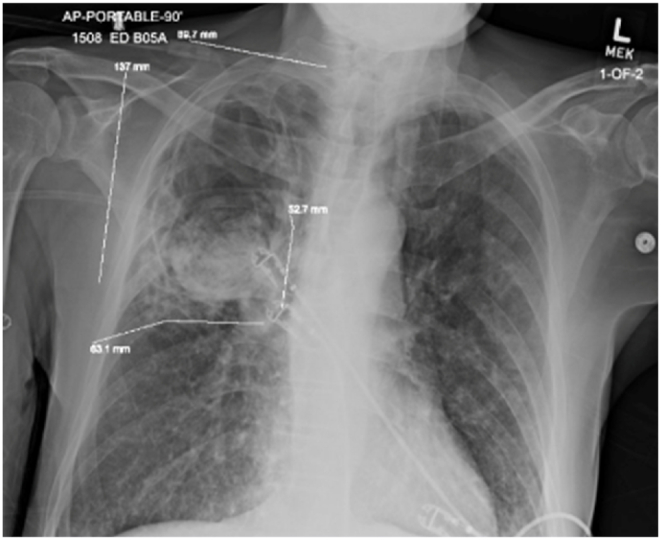

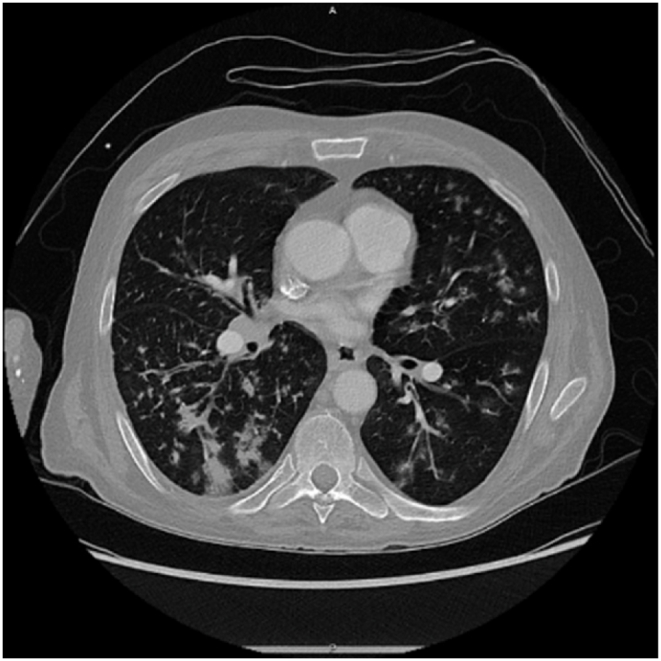

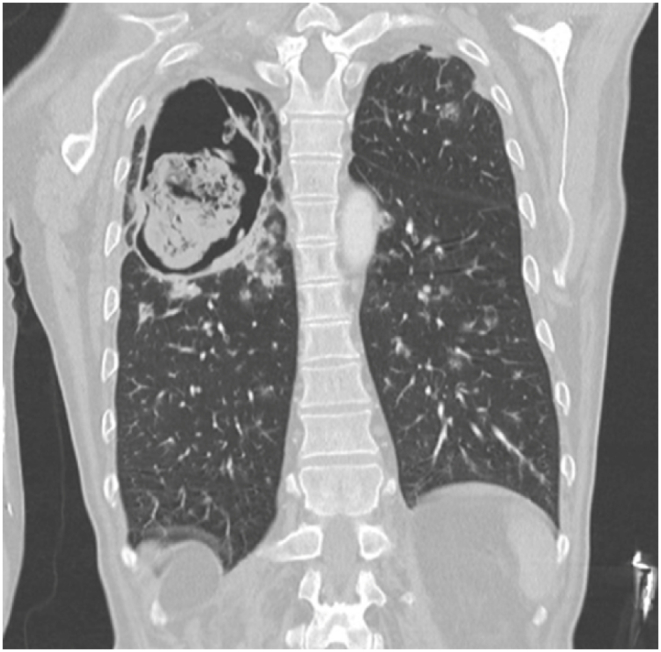

Our patient presented with debility and progressive shortness of breath. He had never seen a physician prior. In addition to a profound smoking history (>50 pack-years) and work history of lawn-and-gardening, he mentioned muscle aches, coughing spells, and frequent illnesses. He appeared malnourished, had dystrophic nails (Fig. 1), and rashes present over extremities. Vital signs noted profound hypoxia (SpO2 80 %) and moderate tachycardia (115–125 bpm). Rapid swab for influenza-A was positive. Chest radiography demonstrated diffuse bilateral interstitial opacities with a large right upper lung lesion, confirmed on CT chest, which also noted a mycetoma versus aspergilloma (Image 2, Image 3, Image 4, Image 5). IgE returned elevated to 58,410 IU/mL (normal <99 IU/mL). 1,3-β-D-glucan was elevated to 436 pg/mL (positive >80 pg/mL). His hypoxia progressed, requiring high-flow nasal cannula at 50 L/min at 100 % FiO2. Allergen panel was pan-positive. Aspergillus galactomannan antigen was positive at 6.32. Aspergillus fumigatus IgG was elevated to >200 μg/mL (normal <99 μg/mL). All other fungal labs were negative. Sputum cultures on admission grew aspergillus species (not fumigatus) and multi-drug resistant (MDRO) Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (Steno). Voriconazole was initiated for the aspergillus, and a combination therapy of Minocycline, TMP-SMX, Ceftazidime-Avibactam, and Aztreonam for the Steno. He was a non-ideal surgical candidate and declined intervention. After weeks of antimicrobial therapy, he ultimately returned to normal oxygen saturations on room air, demonstrated improved appetite and mentation, and was discharged to inpatient rehabilitation.

Image 1.

Initial physical examination of patient's right hand with notably dystrophic nails.

Image 2.

Initial chest radiography demonstrating diffuse bilateral interstitial opacities with a large right upper lung lesion.

Image 3.

CT chest axial view demonstrating bilateral interstitial changes with tree-in-bud changes.

Image 4.

CT chest coronal view demonstrating cavitary lesion with ball-like mass.

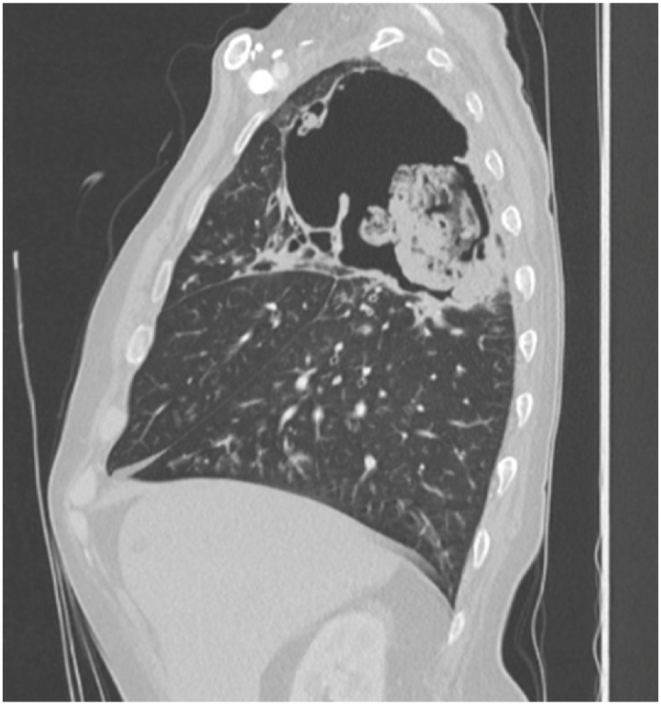

Image 5.

CT chest sagittal view re-demonstrating cavitary lesion with ball-like mass.

3. Discussion

Hyper IgE Syndrome (HIGES), colloquially known as “Job Syndrome,” is estimated to affect one in one million individuals. Diagnostic criteria include elevated serum IgE, dermatitis, and recurrent pulmonary and skin infections [4]. Serum IgE often exceeds 2000 IU/mL in HIGES patients, but a normal IgE does not exclude the disease [5]. Our patient presented with an approximately six-hundred-fold increase of upper limit of normal IgE. Serum IgE levels exceeding 40,000 IU/mL have rarely been described in literature, particularly in the context of a patient presenting with aspergilloma. While these patients frequently present with recurrent respiratory disease, they can also present with dermatologic pathology, including cutaneous candidiasis, eczema, and staphylococcal abscesses. Phenotypic presentations of HIGES are variable, dependent on genotypes; Job Syndrome refers to the autosomal dominant subtype, associated with coarse facial features, joint hyperextensibility, pathologic fractures, and abnormal dental development [6].

Uncovering the presence of a primary immunodeficiency has been a long-established connection to fungal disease [7]. Recently, reactive airway disease secondary to [invasive] fungi has also been described and widely under-reported [8]. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis screening utilizes serum IgE speciation in those with refractory asthma. As such, there are two mechanisms at play. Some patients appear to have fungal infestation causing a modest rise in serum IgE (e.g. ABPA patients). Other patients, like our aforementioned gentleman, have rampant production of serum IgE, as part of an immunodeficiency syndrome, allowing for opportunistic, invasive fungal infections to occur. Aspergillosis describes the chronic, and sometimes cavitary form of pulmonary disease, most commonly caused by Aspergillus fumigatus. Our patient presented with non-fumigatus Aspergillus, which can account for a substantial minority of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis infections [9].

These aspergillus infections are often associated with previous exposures, such as hay, compost, and tree bark. Our patient worked sporadically in outdoor landscaping, but lacked other risk factors for invasive fungal disease (biologic antibodies, high-dose corticosteroids, and previous ICU cares).

In chronic, untreated cases of invasive aspergillosis such as our patient, progression to a chronic cavitary form of the disease is a high-mortality complication [10]. Additionally, patients with long-standing untreated aspergillosis can suffer from lung-volume loss from aspergilloma formation and secondary fibrosis and scarring. Later in the disease course, patients can develop distressing symptoms of hemoptysis and cachexia [11].

The rarity of this case chiefly lies in the staggering elevation of serum IgE. Currently, there are no documented causes of false-positive IgE elevations, especially at levels >10,000 IU/mL [12]. With levels greater than 1000 IU/mL, guidelines suggest a thorough review for allergies and atopic disease, invasive fungal disease, immunodeficiencies, and parasitic infections. Patients with HIGES warrant a multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach.

4. Conclusion

HIGES is estimated to affect fewer than one in one million individuals. Often, the pathology is demonstrated in youth. In our 70-year-old patient, this is a much rarer disease process. In this light, recognition is equally as rare as its incidence. We have tried to parse through inciting events for this case of HIGES. Did the severely elevated production of IgE allow for opportunistic infections, or did the fungal infections due to job exposures in lawn and gardening and COPD cause an elevated IgE? The profound elevation in IgE to nearly 60,000 ng/mL favors the former, in addition to the dystrophic nails and recurrent rashes. Our patient presented with primary pulmonary and secondary dermatologic manifestations, which sparked the suspicion for invasive fungal and immunologic disease. He was treated with appropriate antimicrobials and returned to his baseline pulmonary status. One of the most valuable takeaways from this case is to maintain a broad differential and investigate immune system functionality in cases of invasive fungal disease. While prevention of severe illness may not always be possible, a thorough history, review of risk factors, monitoring of nutritional status (cachexia), and review of immune history could improve patient quality of life.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Joseph D. Nordin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Stephen Smetana: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Rachel Johnson: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Angela Gableman: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Nicholas Nassif: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Mogensen T.H. Primary immunodeficiencies with elevated IgE. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2016;35(1):39–56. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2015.1027820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minegishi Y. Hyper-IGE syndrome, 2021 update. Allergol. Int. 2021;70(4):407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2021.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonilla F.A., Khan D.A., Ballas Z.K., et al. Practice parameter for the diagnosis and management of primary immunodeficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;136(5) doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.04.049. 1186-205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman A.F., Holland S.M. The hyper-ige syndromes. Immunol. Allergy Clin. 2008;28(2):277–291. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verbsky JW, Routes JR. Recurrent fever, infections, immune disorders, and autoinflammatory diseases. In: Nelson Pediatric Symptom-Based Diagnosis. first ed. Elsevier; :746-773.

- 6.Ochs H.D., Notarangelo L.D. In: Williams Hematology. 10e. Kaushansky K., Prchal J.T., Burns L.J., Lichtman M.A., Levi M., Linch D.C., editors. McGraw-Hill Education; 2021. Immunodeficiency diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanternier F., Cypowyj S., Picard C., Bustamante J., Lortholary O., Casanova J.L., Puel A. Primary immunodeficiencies underlying fungal infections. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2013 Dec;25(6):736–747. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000031. PMID: 24240293; PMCID: PMC4098727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pashley C.H., Wardlaw A.J. Allergic fungal airways disease (AFAD): an under-recognised asthma endotype. Mycopathologia. 2021 Oct;186(5):609–622. doi: 10.1007/s11046-021-00562-0. Epub 2021 May 27. PMID: 34043134; PMCID: PMC8536613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeda K., Suzuki J., Watanabe A., Narumoto O., Kawashima M., Sasaki Y., Nagai H., Kamei K., Matsui H. Non-fumigatus Aspergillus infection associated with a negative Aspergillus precipitin test in patients with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022 Feb 16;60(2) doi: 10.1128/JCM.02018-21. Epub 2021 Dec 8. PMID: 34878803; PMCID: PMC8849204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cadena J., Thompson GR 3rd, Patterson T.F. Aspergillosis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2021 Jun;35(2):415–434. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2021.03.008. PMID: 34016284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denning D.W., Cadranel J., Beigelman-Aubry C., et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur. Respir. J. 2016;47(1):45–68. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00583-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasuga K., Nakamoto K., Doi K., Kurokawa N., Saraya T., Ishii H. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in a patient with hyper-IgE syndrome. Resp. Case Rep. 2021;10 [Google Scholar]