Abstract

There is increasing scientific interest in the potential links between meditation practice and pro-environmental behaviours. The present research investigates relationships between Vipassana meditation experience (temporal variables of meditation, five facets of trait mindfulness), positive lifestyle habits (PLH), quality of life (QoL) and per-head carbon footprint (CF) among 25 skilled meditators. Self-reported validated questionnaires were given to a group of native speakers of Sri Lanka to collect data on meditation experience, PLH, and perceived QoL. In estimating CF four domains (food and beverage consumption, electricity consumption, traveling and solid waste disposal) were considered. Correlation analyses revealed that trait mindfulness showed strong associations (r > 0.4) with PLH. None of the temporal variables of meditation experience was significantly correlated with any domain of CF. Two facets of mindfulness (observing and non-reactivity to present-moment experience) demonstrated statistically strong associations (p < 0.05) with perceived QoL. It was found that the PLH significantly mediates the relationship between the observing facet of trait mindfulness and CF associated with food and beverage consumption (indirect effect - 0.002, SE = 0.001 95 % CI [0.010, 0.417]). Further, the relationship between acting with awareness and CF associated with solid waste disposal at landfill sites was significantly mediated by the PLH (indirect effect – (−0.003), SE = 0.003 95 % CI [-0.012, −0.0001]). The current study will serve as a foundation for future longitudinal studies on the same subject by providing evidence for the relationships between meditation experience and PLH, perceived QoL and CF.

Keywords: Meditation, Mindfulness, Carbon footprint, Greenhouse gas, Pro-environmental behaviour

1. Introduction

Meditation has been practised around the world for thousands of years under several religions and philosophies. Research has demonstrated that mindfulness meditation practices have significant positive psychological and physiological impacts. It lays the foundation for understanding the most fundamental concepts of life and reality by tapping into one's mind and behaviour [1]. The current study describes meditation as a collection of mental practices that eventually provide insights into the workings of the mind.

According to Buddhist literature, two major meditation techniques can be introduced: Samatha (concentrative meditation) and Vipasssana. The Pali term "Vipassana" generally means "seeing into something with clarity and precision, recognizing each component as separate, and penetrating all the way through to discern the most fundamental reality of that object" [2]. Since the past, meditation has been practised in various forms, including loving-kindness, body scanning, Zen meditation, mindfulness and breathing.

One major limitation of meditation studies is that they only look at a limited number of variables related to meditation practices, which may make it more difficult to determine whether or not meditation is beneficial [3]. Along with the mindfulness which is the most studied pertinent personality trait to date in meditation-based research [4], Shapiro and Britton [5] highlighted the importance of studying temporal effects of meditation. Length of meditation practice, length of a regular meditation session and frequency of meditation per day could be considered in this regard.

Kabat-Zin [1]mentioned that mindfulness is a core concept of all streams of Buddhist meditation practice. Mindfulness has been examined as an independent variable or a dependent variable in scientific studies [6]. The ability to pay attention to the current moment while retaining an open, nonjudgmental frame of mind is known as mindfulness [4]. The definition of mindfulness may seem familiar to many readers, as one of the primary goals of meditation is to promote present-moment awareness and attention. Moreover, Gunaratana [2] mentioned that mindfulness can be practised during any activity related to Vipassana meditation.

According to theories in Buddhism, people can regularly invoke state mindfulness during meditation sessions, which might improve their predisposition/trait mindfulness [7,8]. In concept, those who practice meditation and achieve deeper levels of mindfulness during meditation sessions are more probable to exhibit mindful attitudes and behaviours in everyday situations. As mentioned by Hosemans [9], trait mindfulness in long-term meditation practitioners is higher than in non-meditators. Further, it has been found that there was no significant difference in trait mindfulness between concentrative meditators and insight meditators. According to the study findings of Bergomi et al. [10], even if there was no difference in trait mindfulness levels among meditation practitioners in Zen, Vipassana and body movement techniques, a significant association between meditation practice and trait mindfulness could be found. The same finding for the relationship between meditation practice and trait mindfulness was found by Falkenström [11], who explored Vipassana meditators.

Meditation could help improve one's quality of life (QoL). Several studies have recommended practicing meditation as a method of improving QoL [[12], [13], [14]]. By practising meditation regularly, a person creates internal peace and clarity that allows them to manage their brain regardless of the circumstances [13]. According to WHO [15], an individual's perception of their status of life is introduced as perceived quality of life. Physical, psychological, environmental and socioeconomic status of a person could be investigated in assessing perceived QoL [16,17]. Dassanayaka et al. [12] mentioned that higher perceived QoL was found in skilled meditators (meditators who practice Vipassana meditation continuously for more than three years and who can maintain continuous attention on the meditation object) compared to age-gender-matched non-meditators. As mentioned by Dargah [18], Vipassana meditation is associated with higher perceived QoL.

People who practice Vipassana meditation reduce obsessive reactivity and increase their ability to behave purposefully by learning to evaluate their sensory experiences, notice thoughts as they occur, and respond with calm detachment and clarity [2]. Sensual desire, ill-will, sloth and torpor, remorse, and skeptical doubt are considered to be five mental hindrances, which are unwholesome negative feelings that obscure one's view and make it difficult for one to act rationally in day-to-day situations [19]. Abblett [20] stated that meditation is the mirror that precisely displays how each of the hindrances is encasing our perspective on life. Therefore, meditation may play a role in promoting positive lifestyle habits (PLH) by inhibiting negative mental states. A positive lifestyle habit is a behaviour, deed, or attitude that a person desires to adopt and incorporate into his or her life because it has beneficial outcomes. According to Lea et al. [21], PLH associates with well-being and good health. As stated by Ee et al. [22], meditation could encourage the initiation and maintenance of healthy living behaviours. Sieja [23] argued that PLH which supports the best performance of college students in academic work could be promoted through meditation. There is a paucity of studies on the relationship between PLH and meditation experience in non-clinical long-term meditation groups, hence the current study concentrated on this relationship.

Only a handful of research could be found on the role of meditation in pro-environmental behaviours. The term "pro-environmental behaviour" describes the adoption of behaviours to reduce environmental harm or restore the natural environment [24]. As found by Jacob et al. [25], mindfulness meditation is positively associated with sustainable household choices and sustainable food practices. Researchers have found that pro-environmental behaviours such as eating lower Carbon food, using eco-friendly traveling methods, recycling, water-saving and mindful consumption of energy are common practices among meditators and mindfulness practitioners [[26], [27], [28], [29]]. Panno et al. [29] were able to find that the belief in climate change is significantly higher in Zen (mindfulness) meditation practitioners than in non-meditation practitioners. Although Thiermann et al. [30] discovered that mindful compassion meditation practitioners have a deeper sense of environmental motivation and produce less adverse environmental effects, Riordan et al. [31] discovered no discernible difference in ecological footprint between Vipassana meditators and the meditation naïve group. Furthermore, when researching the connection between meditation and pro-environmental behavior, Thriemann et al. [30] emphasized the need of examining the practice of meditation, particularly the frequency of meditation. Given the effects of meditation on specific related variables including attitudes toward the environment and perceived quality of life, pro-environmental behavior can potentially be improved through the use of meditation training [[32], [33], [34], [35]]. Out of a handful of research on the role of meditation in pro-environmental behaviours, a limited number of scientific studies [27,32]have focused on the role of meditation in controlling greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Furthermore, there is a lack of scientific investigations examining the relationships between GHG emissions and the experience of long-term meditation practitioners. Hence, the present study may shed light on this relationship that will have applications in climate change mitigation. Global anthropogenic GHG emissions have continued to increase since the industrial era and increased greenhouse gases (GHGs) have been the dominant cause of the observed global warming trend since the mid-20th century [36]. The increasing GHGs in the troposphere cause long-term climate changes, bringing negative consequences in many parts of the world. Based on the ambitious goal of the Paris Agreement to reduce the temperature rise within the century to well below 2 0C, the majority of the member parties, including Sri Lanka, have developed plans to reach net-zero carbon emissions by the middle of the century. One of the strategies being used to move toward net-zero carbon societies with improved living standards is the shift to sustainable lifestyles. The shift to net-zero carbon society may be aided by meditation-based interventions targeting individual level contributions, which are regarded as lifestyle innovations. Though research is currently ongoing, it is still unclear which meditation associated predictors are connected with greater quality of life and lower per-head greenhouse gas emission. Further, there is a lack of studies on the mediating mechanism of lifestyle factors such as perceived QoL and lifestyle habits on the relationship between meditation experience and per-head carbon footprint (CF; GHG emission in carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2eq) per individual per year).

We follow the argument that meditation experience (study variables -. range of years of practice of continuous meditation preceding to the date of recruitment (RYP), average time duration of a regular meditation session (AtMS), trait mindfulness) may have associations with PLH, per head CF and perceived QoL. Hence the primary objective of the present study was to explore the possible correlations between meditation experience and PLH, per-head CF, perceived QoL. Based on the preliminary observations in the present study and the findings of previous studies, the following argumentation was developed to investigate the mediating role of PLH in the relationship of meditation experience with per head CF as the secondary objective of the present study.

Trait mindfulness which is a variable of meditation experience is significantly associated with proenvironmental behaviours [25,29,33,[37], [38], [39], [40]]. Awareness of the present moment causes us to have better self-awareness. Self-awareness empowers us to affect outcomes, makes us better decision-makers, and boosts our self-esteem [41,42]. Moreover, Lee et al. [43] argued that mindfulness has the potential to increase self-esteem and reduce stress, therefore cultivating positive attitudes about one's life. When one is positive, she or he thinks positively, feels positive, and exhibits positive actions like benevolence and compassion. Therefore, positive lifestyle habits can be expected with enhanced trait mindfulness through practicing meditation. As trait mindfulness relates to both per head-CF and PLH, we assumed that PLH may play a mediating role in the relationship between trait mindfulness and per-head CF. Therefore, the hypotheses tested in the present study were as follows.

Hypothesis 1

Relationship between the observing facet of mindfulness and per-head carbon footprint based on food and beverage consumption is mediated by positive lifestyle habits.

Hypothesis 2

Relationship between trait mindfulness and per-head carbon footprint based on travel behaviour is mediated by positive lifestyle habits.

Hypothesis 3

Relationship between the acting with awareness facet of mindfulness and per-head carbon footprint based on solid waste disposal behaviour is mediated by positive lifestyle habits.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study design

This study was a cross-sectional study which used purposive sampling technique to select study subjects. Correlational analysis and ordinary least squares regression were conducted to identify possible associations and relationships between meditation experience and PLH, per head CF and perceived QoL.

2.2. Selection of study participants

The study participants (114 regular meditation practitioners) aged between 30 and 65 years and had regularly practised Vipassana meditation atleast for 4 h per week for 3 years as the minimum duration of continuous practice of meditation preceding the date of recruitment were selected from meditation centres located in the districts of Colombo, Gampaha, Matale and Kandy in Sri Lanka. The selection of the study participants was assisted by a meditation Guru/trainer of the relevant meditation centre. Meditators who had physical disabilities, diabetes and those who followed a food-based dietary guideline were excluded.

All eligible participants (70 experienced meditators) were further screened using a structured screening test: the “The University of Colombo Intake Interview to identify Skilled Meditators for scientific research (UoC-IISM)” which was a judgmentally validated interviewer-administered questionnaire [44]. Based on the obtained scores for the sections of UOC-IISM (section C1: fall back score (FS) = 7–9 and ideal score (IS) = 10–12, section C2: FS = 14–16 and IS = 17–20, section D: FS = 25–29 and IS = 30–35), skilled meditators were recruited for the current study. Skilled meditators can sustain continuous attention to the meditation object [44]. As in the conceptual framework to identify skilled meditator [45], a skilled meditator is a person who has established meditation practice, overcome mind wandering and forgetting. It is considered that a skilled meditator can be aware of the state of mind at every moment due to extended attention.

2.3. Sample size

G∗power [46] was considered in calculating sample size considering the F test category as suggested by Schoemann et al. [47] for sample size calculation in mediation analysis. When the power and the effect size were set at 0.8 and 0.25 respectively under the statistical test for Linear multiple regression; fixed model, the sample size was 34 (for simple mediation analysis with three variables: X, Y and the mediator variable).

2.4. Characteristics of the study participants

The mean section scores of UOC-IISM and lifestyle characteristics of the study participants (n = 25, (1-β) = 0.66) are outlined in Table 1. The mean age (±SD) of the participants was 44 ± 10.39 years. Fifty-two percent of the study population was males. All the participants had completed secondary education. All the study participants were guided by a meditation Guru/trainer and 19 participants had practised meditation for more than 5 years. The percentage of meditators who practised meditation on daily basis was 81 %. Breath was the meditation object of 68 % of study participants while body parts were used as meditation objects by 52 % of participants. Further, 76 % of participants practised meditation through contemplating word phrases regarding promoting compassion and loving-kindness.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study group (n = 25).

| Mean scores of UOC-IISM | |

|---|---|

| Mean (±SD) - Section C1 | 8.66 ± 1.05 |

| Mean (±SD) - Section C2 | 16.64 ± 2.62 |

| Mean (±SD) - Section D | 29.07 ± 2.97 |

| Lifestyle variables | |

|

92 % |

|

56 % |

|

48 % |

|

92 % |

|

44 % |

|

92 % |

|

36 % |

2.5. Assessment procedures

Questionnaire-based data collection methods were used in the present study. All the research procedures were tested for feasibility and details regarding each tool have been given in Annex 1.

2.5.1. Meditation experience

2.5.1.1. Temporal variables of meditation experience

Buddhist Meditation Experience Questionnaire, BMEQ [48] was used in collecting data on temporal variables of meditation practice (RYP, AtMS). The BMEQ was developed and judgmentally validated (i.e. face validity, content validity and consensual validity were ensured) by the same research group. The range of years of practice of continuous meditation preceding to the date of recruitment (RYP) was assessed using 1 to 4 scale ranging from less than one year of meditation practice to more than five years of meditation practice. A 1–3 scale ranging from less than 30 min of average time duration of a regular meditation session to more than 60 min of average time duration of a regular meditation session was used to assess AtMS.

2.5.1.2. Trait mindfulness

A judgmentally validated (i.e. face validity, content validity and consensual validity were ensured) Sinhala (i.e. native language) version of the FFMQ which is a 39-item psychological questionnaire was used to explore meditators’ trait mindfulness. The original version, the English version of FFMQ was developed by Baer et al. [49] and it addresses five elements of trait mindfulness: i. non-reactivity to present moment experiences, ii. observing/attending to sensations/perceptions/thoughts/feelings on the recent moment, iii. acting with awareness/concentration, iv. describing/labelling experience with words and v. non-judging of experience. A 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true) was used in rating items.

The scientific validation of the Sinhala version of FFMQ was carried out by Outschoorn et al. [50] and the Cronbach's alpha level for the overall scale is 0.91. Moreover, acceptable Cronbach's alpha levels (α ranges from 0.77 to 0.92) for the five subscales indicate good internal reliability of the scale. Baminiwatta et al. [51] who conducted research in a Sri Lankan Buddhist context reported a range of Cronbach's alpha from 0.67 to 0.72 as internal consistency of 5 subscales of a Sinhala version of FFMQ. However, only 21 % of the study sample consisted of regular meditation practitioners and the importance of ensuring the validity of a Sinhala version of FFMQ among regular practitioners of meditation has been emphasized.

2.5.2. Per-head CF

Data collection sheets were prepared using the guidelines for GHG emission inventorying and calculation [[52], [53], [54]]. A participant had to record data for 14 days. A request was made to avoid days when the participant could not follow the usual daily routine. Data collection sheets were bound into a booklet for use in collecting GHG emission data under 4 domains: (i) food and beverage consumption, (ii) electricity consumption at residence, (iii) traveling and (iv) solid waste disposal at residence. All the guidelines for recording data were provided in writing and verbally and data recording was followed up every 3 days during the experimental period. Collected data was used in calculating carbon footprints under the domains.

-

(i)

GHG emissions under food and beverage consumption

Participants recorded food and beverage consumption data under commonly used 7 measurement units (coconut shell spoon, tablespoon, teaspoon, number of teacups, number of water glasses, number of pieces of the food, whole food) in Sri Lanka and spaces were given if food and/or beverage consumption could be mentioned using metric units (kg/g/ml/l). Converting data into grams was assisted by weight conversion factors drawn from Jayawardena and Herath [55], Nette et al. [56], Nutrition Division Ministry of Health [57] and Rahman et al. [58]. Emission factors for 43 food and beverage items were drawn from Carlsson-Kanyama and González [59], Audsley et al. [60], Clune et al. [61], Elapata and De Silva [62], Munasinghe et al. [63], Nette et al. [56] and Pathak et al. [64] to be used in Equation (1). Total GHG emission (considering GHGs; CO2, CH4, N2O) due to food and beverage consumption during the study in Carbon dioxide equivalent (i.e. CF) was calculated using Equation (1).

| Equation 1 |

CFFB = Carbon footprint based on food and beverage consumption (t CO2e per year)

WFB = Weight of the consumed food/beverage in kg.

EF = Emission factor in g CO2e per kg of food/beverage Or else g/kg of food and beverage item.

GWP = Global warming potential for the next 100 years according to IPCC 2007 [65].

(14/365)∗10−6 = converting units of CFFB (g CO2e for 14 days) into t CO2e per year.

-

(ii)

GHG emissions under electricity consumption at residence

Electricity consumption-associated data (i.e. the rate of consumption (W), model, model number, and time used in minutes) were collected for electrical appliances. Using the collected data, electricity consumption in kilowatt-hours (kWh) was calculated and it was used in calculating total indirect GHG emission based on the electricity consumed per year in t CO2eq (CFEC). When the W value wasn't reported by the participants, reference values were drawn from websites of the Presidential task force on energy demand side management, Lanka Electricity Company (Pvt) Ltd (LECO) [66] and Daft Logic [67]. The beta version of the GHG emission calculation tool [68] was used for calculating CFEC using country-specific emission factors for electricity consumption [69].

-

(iii)

Travel behaviour associated with GHG emission

The beta version of the GHG emission calculation tool [54] was used in calculating travel associated GHG emissions (i.e. GHG emissions due to use of personal vehicle/s and employee commuting) per year in tonnes CO2eq (t CO2eq; CFTB). Participants' self-reported travel data: travel distance in kilometers (km), method of travel, and fuel source/s were collected. Default emission factors provided by the calculation tool for mobile combustion and transportation were used in the calculation.

-

(iv)

Solid Waste (SW) disposal (at resident) behaviour associated GHG emission

Data on waste segregation, type/s of SW, waste disposal method/s and weight of collected SW was collected from each participant. A weighing scale (maximum weight: 50 kg, d = 10 g) was provided to measure the weight of the collected SW. The default method of the IPCC tier 1 approach (Equation (2)) was used to estimate CH4 emissions from solid waste sent to disposal sites in Gigagrams per year (Ggyr−1). Equation (3) was used in estimating CO2 in Ggyr−1 from open burning of SW.

| Equation 2 |

Where:

SWT = Total SW generated (Ggyr−1)

SWF = Fraction of SW disposed at a solid waste disposal site.

L0 = Methane generation potential [MCF • DOC • DOCF • F • 16/12 (Gg CH4/Gg waste)]

MCF = Methane correction factor (default = 0.4)

DOC = Degradable organic carbon (calculated using Equation (5.2) in the IPCC Good Practice Guidance and Uncertainty Management in National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, pg 5.9 [70])

DOCF = Fraction DOC dissimilated (default = 0.77)

F = Fraction by volume of CH4 in landfill gas (default = 0.5)

R = Recovered CH4 (Gg/yr) (default = 0)

OX = Oxidation factor (default = 0)

| Equation 3 |

Where:

CO2 emissions = CO2 emissions in inventory year, (Ggyr−1)

SW = total amount of municipal solid waste as wet weight open-burned, Gg/yr.

WFj = fraction of waste type/material of component j in the SW (as wet weight open burned)

dmj = dry matter content in the component j of the SW open-burned, (fraction)

CFj = fraction of carbon in the dry matter (i.e. carbon content) of component j.

FCFj = fraction of fossil carbon in the total carbon of component j.

OFj = oxidation factor, (fraction)

44/12 = conversion factor from C to CO2

with: Σj WFj = 1

j = component of the SW open-burned such as paper/cardboard, textiles, food waste, wood, disposable nappies, rubber and leather and plastics.

Global warming potential (GWP) of CH4 (GWP = 25) and CO2 (GWP = 1) for the next 100 years according to IPCC [71] were used in setting the GHG emission due to solid waste disposal in t CO2eq (carbon footprint based on the SW disposal at unmanaged disposal sites; CFSWDS, carbon footprint based on the SW open burning; CFOB).

2.5.3. Positive Lifestyle Habits (PLH)

Perception-based assessment on PLH was done using 22 self-reported statements (PLH scale; eg. I have a good control over my food consumption pattern, I am not harsh on people who are angry with me, I rarely feel guilty about my mistakes, Unfair events make me angry) [48] on a 5-point Likert scale; 5 – strongly agree and 1 – strongly disagree. Ten items of the PLH scale were reversed-score items. When the total score of the aforementioned perception-based assessment is high, it indicates that the person has more positive habits in his or her daily life. The Cronbach's alpha level for the PLH scale was 0.70.

2.5.4. Perceived Quality of Life (perceived QoL)

The discriminant and convergent validity ensured a brief Sinhala version of the World Health Organization-Quality of Life questionnaire (WHO-QOLBREF) [72] was used in assessing perceived QoL. It provides for a detailed analysis of each domain (DOM; 1. physical health, 2. psychological health, 3. social relationships, and 4. environment) of quality of life. Respondents rated 26 items using a Likert scale (1 -Not at all, 2 - Not much, 3 – Moderately, 4 - A great deal, 5 - Completely) based on the perceptions of quality of life for two weeks before answering the questionnaire. SPSS syntax for carrying out data checking, cleaning and computing total scores [15,46] was used in calculating domain scores. The Cronbach's alpha level for the overall scale was 0.90. With the exception of the social relationship domain, all domains had Cronbach's alpha values above 0.7.

2.5.5. Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS 23 was used in the statistical analysis. The Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted for checking the normality of data sets. Parametric and non-parametric bivariate correlational tests under 95 % confidence level were conducted to identify possible correlations between study variables. To calculate the power of the final sample size, G∗power [46] software was used.

To conduct mediation analysis, we used the Hayes PROCESS macro for SPSS [73] with 5000 bootstrap samples. A bias-corrected bootstrap-confidence interval (CI) for the product of hypothesized paths in mediation that does not include zero [74] was considered evidence of a significant indirect effect. Co-variates were controlled under the mediation analyses.

3. Results

The power of the final sample size was 0.66. Carbon footprints except for CFFB, NYP and SD were not normally distributed. Correlations among meditation experience, perceived QoL and CF are indicated in Table 2.1 and Table 2.2. Three facets of trait mindfulness are strongly associated with PLH (r ≥ 0.54) while acting with awareness and describing facets moderately associated with PLH (r = 0.5). Observing and non-reactivity to present moment experience were only the facets of trait mindfulness which showed significant strong correlations (p < 0.05) with all domains of perceived QoL.

Table 2.1.

Pearson correlations and descriptive statistics for normally distributed variables; PLH, perceived (P.) QoL, trait mindfulness and CFFB

| Variable | i | ii | iii | iv | v | vi | vii | viii | ix | x | xi | xii | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | PLH | 1 | |||||||||||

| ii | Total mindfulness | 0.66∗∗ | 1 | ||||||||||

| iii | FFMQ-i | 0.55∗∗ | 0.76∗∗ | 1 | |||||||||

| iv | FFMQ-ii | 0.55∗∗ | 0.80∗∗ | 0.79∗∗ | 1 | ||||||||

| v | FFMQ-iii | 0.45∗ | 0.75∗∗ | 0.45∗ | 0.40∗ | 1 | |||||||

| vi | FFMQ-iv | 0.46∗ | 0.87∗∗ | 0.60∗∗ | 0.61∗∗ | 0.71∗∗ | 1 | ||||||

| vii | FFMQ-v | 0.50∗ | 0.66∗∗ | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.48∗ | 1 | |||||

| viii | DOM1 | 0.61∗∗ | 0.47∗ | 0.57∗∗ | 0.55∗∗ | 0.16 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 1 | ||||

| ix | DOM2 | 0.58∗∗ | 0.69∗∗ | 0.65∗∗ | 0.67∗∗ | 0.46∗ | 0.64∗∗ | 0.30 | 0.76∗∗ | 1 | |||

| x | DOM3 | 0.50∗ | 0.45∗ | 0.46∗ | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.49∗ | 0.45∗ | 0.57∗∗ | 1 | ||

| xi | DOM4 | 0.50∗ | 0.44∗ | 0.47∗ | 0.51∗∗ | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.57∗∗ | 0.58∗∗ | 0.66∗∗ | 1 | |

| xii | CFFB | −0.16 | −0.39 | −0.28 | −0.51∗∗ | −0.06 | −0.27 | −0.30 | −0.21 | −0.37 | −0.66∗∗ | −0.45∗ | 1 |

FFMQ-i: non-reactivity, FFMQ-ii: observing, FFMQ-iii: acting with awareness, FFMQ-iv: describing, FFMQ-v: non-judging of experience.

DOM1 – P. QoL based on physical health, DOM2 – P. QoL based on psychological health, DOM3 – P. QoL based on social relationships, DOM4- P. QoL based on surrounding environment.

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Table 2.2.

Spearman's rho values for not normally distributed Temporal variables of meditation experience (RYP, AtMS) and individual CF-associated data sets (CFEC, CFTB, CFSWSWDS, CFSWOB).

| Variable | RYP | AtMS | CFEC | CFTB | CFSWSWDS | CFSWOB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLH | 0.16 | 0.25 | −0.34∗ | 0.13 | −0.08 | 0.07 |

| Total mindfulness | 0.05 | 0.21 | −0.11 | 0.40∗ | 0.34 | −0.12 |

| FFMQ-i | 0.26 | 0.43∗ | −0.21 | 0.24 | 0.04 | −0.02 |

| FFMQ-ii | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.32 | 0.19 | −0.09 |

| FFMQ-iii | 0.15 | 0.01 | −0.27 | 0.53∗∗ | 0.53∗∗ | −0.27 |

| FFMQ-iv | 0.26 | 0.28 | −0.14 | 0.34 | 0.21 | −0.12 |

| FFMQ-v | −0.36 | 0.02 | −0.13 | 0.22 | 0.09 | −0.12 |

| DOM1 | 0.25 | 0.39 | −0.27 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.12 |

| DOM2 | 0.34 | 0.37 | −0.24 | 0.12 | 0.18 | −0.13 |

| DOM3 | −0.11 | 0.32 | −0.14 | −0.06 | −0.20 | 0.02 |

| DOM4 | −0.07 | 0.36 | −0.21 | −0.13 | −0.12 | 0.28 |

| RYP | 1 | 0.42∗ | −0.16 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.05 |

| AtMS | 0.42∗ | 1 | −0.28 | −0.09 | −0.23 | 0.16 |

| CFEC | −0.16 | −0.28 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.14 | −0.23 |

| CFTB | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.62∗∗ | −0.43∗ |

| CFSWSWDS | −0.01 | −0.23 | 0.14 | 0.62∗∗ | 1 | −0.53∗∗ |

| CFSWOB | −0.05 | 0.16 | −0.23 | −0.43∗ | −0.53∗∗ | 1 |

FFMQ-i: non-reactivity, FFMQ-ii: observing, FFMQ-iii: acting with awareness, FFMQ-iv: describing, FFMQ-v: non-judging of experience.

DOM1 – P. QoL based on physical health, DOM2 – P. QoL based on psychological health, DOM3 – P. QoL based on social relationships, DOM4- P. QoL based on surrounding environment.

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Although we expected negative correlations between mindfulness and CF, the CFTB and CFSWDS showed significant positive associations with the facet of acting with awareness of trait mindfulness (p(CFTB/CFSWSD-(FFMQ-iii)) < 0.01). Similarly, CFTB positively correlated with total trait mindfulness (p < 0.05). Observing facet of mindfulness showed a significant negative correlation with CFFB (p < 0.01).

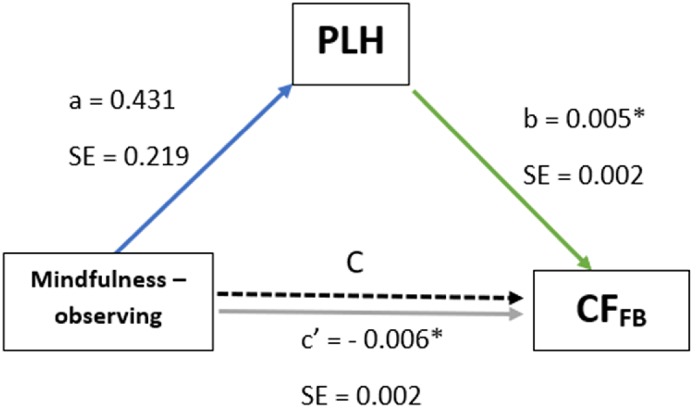

Results revealed that PLH significantly mediates the relationship between observing facet of trait mindfulness and CFFB (indirect effect - 0.002, SE = 0.001 95 % CI [0.010, 0.417]) which warranted accepting Hypothesis 1 (Fig. 1). Hypothesis 2 was rejected as there was no significant indirect effect of trait mindfulness on CFTB through PLH (indirect effect - 0.002, SE = 0.017 95 % CI [−0.028, 0.039]; Fig. 2). Hypothesis 3 was not rejected as there was a significant indirect effect on the relationship between acting with awareness and CFSWDS through PLH (indirect effect – (−0.003), SE = 0.003 95 % CI [−0.0124, −0.0001]; Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Path coefficients for the mediation model-Hypothesis 1

C = c’+ab = −0.004, SE = 0.002

Note. The dotted line denotes the effect of observing facet of mindfulness on CFFB when PLH is not included as a mediator.

“a”, “b”, “c” and “c′” are unstandardized ordinary least square regression coefficients.

R2 for total effect model = 0.521

∗p 0.05

Fig. 2.

Path coefficients for the mediation model-Hypothesis 2

C = c’+ab = 0.008, SE = 0.018

Note. The dotted line denotes the effect of observing facet of mindfulness on CFTB when PLH is not included as a mediator.

“a”, “b”, “c” and “c′” are unstandardized ordinary least square regression coefficients.

R2 for total effect model = 0.210

∗p 0.05

Fig. 3.

Path coefficients for the mediation model-Hypothesis 3

C = c’+ab = 0.016, SE = 0.005

Note. The dotted line denotes the effect of acting with awareness facet of mindfulness on CFSWDS when PLH is not included as a mediator.

“a”, “b”, “c” and “c′” are unstandardized ordinary least square regression coefficients.

R2 for total effect model = 0.195

∗p 0.05

4. Discussion

The present research conducted an in-depth analysis on the relationships among meditation, PLH, perceived QoL and per-head CF. The study found no significant correlations between temporal variables and PLH, perceived QoL and per-head CF. Trait mindfulness which was considered as a variable of meditation experience significantly connected with PLH, per-head CF, and perceived QoL. Investigations on the insights into how and why meditation experience influences per-head CF provide evidence for the mediating role of PLH in the relationship between meditation experience and per-head CF.

The findings of the current study revealed that the relationships between trait mindfulness and carbon emissions based on solid waste disposal behaviour and food-beverage consumption behaviour are partially mediated by PLH. To our knowledge, there is no previous research specifically examining the mediating role of PLH in the relationship between meditation and per-head CF. However, it is plausible that PLH could mediate this relationship, as meditation has been shown to promote a wide range of positive lifestyle habits that are associated with reduced carbon footprints, such as mindful consumption and improved physical activity. Moreover, we believe that as a variable of meditation experience, trait mindfulness makes alternative behavioural choices through meditation and brings positive impacts on lifestyle behaviours and attitudes which may promote nature-friendly, suitable behaviours. Such promotions may lead to engagement in behaviours which cause minimal emission of Carbon to the atmosphere.

The observed low path coefficients in mediation models may be due to the final sample size in the present study. However, as suggested by Schoemann et al. [47], 0.7 which was obtained as the power of the final sample size in the present study is often considered sufficient for detecting effects in mediation analysis with three variables. Moreover, the sample size of the present study was the optimum sample size which could be found through the strict methodology of participant screening. Out of the whole study units in Baminiwatta et al. [51], only 21 % practised meditation and only 1.9 % of regular meditation practitioners followed Vipassana meditation. This indicates that identifying a large sample of long-term experienced Vipassana meditation practitioners could be quite difficult, especially for scientific research. Moreover, it may be taken more time and effort. Therefore, longitudinal research on the topic of present study is recommended for future researchers. Further, indirect effect values presented through this research paper can be considered in sample size calculations in future mediation analysis on the same topic.

Though we used multiple variables of meditation experience, most of the previous research did not consider many variables of meditation in the analyses. In addition to the major outcomes of the present study, we observed that with the increase in the duration of a regular mediation session, the ability to have a nonreactive manner to current events (i.e. conscious choice-making) is increased which may cause greater cognitive control as mentioned by Anicha [75]. This is further supported by the observed significant positive correlations of trait mindfulness with PLH and perceived QoL.

Although both traditional Buddhist teachings on meditation and cutting-edge neuroscience have supported the idea that repeated meditation practice is beneficial, not investigating the frequency of meditation is a limitation of the present study. Further, even if Josefsson and Larsman [76] reported that age and gender as covariates of mindfulness, it was not the same for the sample used in the present research. This study may use as a foundational study that delves deeper into the examination of how a positive lifestyle could mediate the association between carbon emissions and meditation. Since no other research on meditation's role in mitigating climate change has attempted to quantify per-head carbon footprint beyond using methods for recall data collection, findings of the present study will open up the path towards more in-depth research in this area. Meditation has been shown to have a positive effect on a wide range of lifestyle habits, including physical activity [77], healthy eating [78] and stress management [79]. One of the key benefits of meditation is that it helps individuals become more aware of their thoughts, emotions, and behaviours [[80], [81], [82]]. By increasing self-awareness, meditation may help individuals in identifying negative patterns of behaviour and making more conscious choices about their lifestyle habits. These might be the reasons behind the observed significant relationship between trait mindfulness and PLH. Moreover, Zeidan et al. [83], suggest that meditation can improve emotional regulation by increasing activity in the bilateral Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC), a brain region that plays a key role in regulating emotions. By improving emotional regulation, meditation may help individuals to cope with negative emotions and stressors in a more adaptive way, making them resort to more positive lifestyle behaviours. Furthermore, PLH creates a feedback loop that improves mental clarity and emotional stability, both of which are useful for enhancing meditation practice [84]. As a result, the two-way link between meditation and PLH creates a positive feedback loop. The cyclical connection promotes long-term improvements in general health and well-being.

Chiesa and Serretti [85] found that meditation improves attention and cognitive function in healthy individuals. It leads to better performance in tasks that require cognitive control, working memory, and other cognitive abilities. By improving cognitive function, meditation may improve perceived QoL in areas such as work and relationships, where cognitive skills are often necessary for success. Previous research has shown that individuals who score higher on the non-reactivity facet of mindfulness tend to have better emotional regulation and coping skills and may be less likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors as a way of coping with stress [49,86]. This, in turn, may lead to better-perceived QoL, as individuals are better able to manage stress and maintain positive emotional well-being. Further, the significant relationships between the observing facet and perceived QoL in all aspects may be due to the developed sense of detachment and perspective through meditation which may lead to greater emotional stability and resilience. Further, as life improves with meditation, higher quality of life may strengthen the commitment to meditation, creating a cyclical effect of well-being and mindfulness.

In the present study, out of all facets of mindfulness, the observing facet and the acting with awareness facet played a significant role with per-head CF. The observing facet of mindfulness is the strongest predictor of the relationship between mindfulness and connectedness to nature, according to Barbaro and Pickett [87] and Howell et al. [88]. To feel emotions like awe and wonder in the natural world, one must slow down and actively pay attention to it. When one's emotions and sentiments are influenced, he or she is more likely to commit to having acceptable behaviours or avoiding unpleasant behaviours [89]. With the practice of meditation, one's compassion and sympathy towards nature might be promoted and subsequently, it may lead to positive changes in his or her behaviour at different levels [90]. Therefore, more mindful people may have fewer greenhouse gas emissions. However, the unexpected positive associations between mindfulness and per-head CF in the present study may be because of the confounding factors associated with environmental education. As indicated in Table 1, the percentage of sample units having knowledge on CF was less than 50 %. Even if meditation can certainly play a role in enhancing moral values and ethical behaviour [91], environmental education is needed to share knowledge of what should be done for sustainability of the environment.

Acting with awareness which is a component of trait mindfulness may grow along with observing facet of mindfulness. Since increased awareness inhibits automatic behavioral responses [41] and encourages behavioral management [42], the authors of the current study believe that raising awareness of acceptable behavioural options, such as low carbon-emitting behaviours (e.g., recycling waste, eating plant-based foods), could be encouraged. As mentioned before, meditation has been shown to promote well-being, which may in turn reduce the desire for material possessions and consumption. By reducing materialism and promoting a simpler lifestyle, individuals may be more likely to make choices that are environmentally sustainable and reduce their carbon footprint.

Although the study has certain limitations such as potential biases inherent in self-reported data, the cross-sectional nature of the study, and lack of a control group, etc., significant findings of the current study provide evidence that cultivating mindfulness not only enhances personal well-being, but also encourages environmentally conscious actions. The continued practice of meditation can make individuals become more aware of the impact of their actions on the environment, fostering low-carbon behaviours and lifestyles in them. Such individual-level action is crucial in dealing with climate change as the most threatening environmental issue of the century. Conclusions.

The present study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on meditation PLH, perceived QoL and pro-environmental behaviour. In the present study, we have presented (i) possible correlations of meditation experience with PLH, perceived QoL and per-head CF and (ii) statistical models illustrating a relevant and broad potential mechanism underlying the observed significant associations between meditation experience and the per-head CF. The findings of the present study suggest that meditation experience correlates with PLH, perceived QoL and per-head CF of a skilled meditator and PLH plays a mediating role in the relationships between meditation experience and per-head CF. Since this is the first effort by a group of environmental researchers to investigate the role of meditation in per head CF along with PLH and perceived quality of life, the results of the current study will help future researchers to develop more comprehensive research designs in relation to meditation and pro environmental behaviours. In light of this study and its findings, meditation-based interventions could potentially be further explored in the future to support low-carbon lifestyles and perceived quality of life.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

E.A.S.K. Somarathne: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. M.W. Gunathunga: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. E. Lokupitiya: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Faculty of Medicine (FOM) at University of Colombo (UOC), Sri Lanka (EC/19/103). All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Accelerating Higher Education Expansion and Development (AHEAD) Operation of the Ministry of Higher Education funded by the World Bank [Grant No. 6026-LK/8743-LK].

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e41144.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003;10:144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunaratana H. twentieth ed. ReadHowYouWant. com; 2010. Mindfulness in Plain English. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas J.W., Cohen M. A Methodological review of meditation research. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown K.W., Ryan R.M. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003;84:822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro S.L., Britton W.B. 2014. An Analysis of Recent Meditation Research and Suggestions. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everyday Sociology Blog: Mindfulness and Methodological Confusion. [cited 27 Jan 2024]. Available: https://www.everydaysociologyblog.com/2016/04/mindfulness-and-methodological-confusion.html.

- 7.Bravo A.J., Pearson M.R., Wilson A.D., Witkiewitz K. When traits match states: examining the associations between self-report trait and state mindfulness following a state mindfulness induction. Mindfulness (N Y) 2018;9:199–211. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0763-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoury B., Knäuper B., Pagnini F., Trent N., Chiesa A., Carrière K. Embodied mindfulness. Mindfulness (N Y) 2017;8:1160–1171. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0700-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hosemans D. Meditation: a process of cultivating enhanced well-being. Mindfulness (N Y) 2015;6:338–347. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0266-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergomi C., Tschacher W., Kupper Z. Meditation practice and self-reported mindfulness: a cross-sectional investigation of meditators and non-meditators using the comprehensive inventory of mindfulness experiences (CHIME) Mindfulness (N Y) 2015;6:1411–1421. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0415-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falkenström F. Studying mindfulness in experienced meditators: a quasi-experimental approach. Pers Individ Dif. 2010;48:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dasanayaka N.N., Sirisena N.D., Samaranayake N. Impact of meditation-based lifestyle practices on mindfulness, wellbeing, and plasma telomerase levels: a case-control study. Front. Psychol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.846085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bajpai C., Kiran U.V. Meditation and quality of life: a comparative study among meditators and NON-meditators. Journal of Seybold Report. 2020;15:330–343. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348690081 Available: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levin A.B., Hadgkiss E.J., Weiland T.J., Marck C.H., Van Der Meer D.M., Pereira N.G., et al. Can meditation influence quality of life, depression, and disease outcome in multiple sclerosis? Findings from a large international web-based study. Behav. Neurol. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/916519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO . 2024. WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life.https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol/whoqol-bref [cited 16 Dec 2024]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higuchi M., Liyanage C. Factors affecting quality of life among independent community-dwelling senior citizens in Sri Lanka: a narrative study. Asian Journal of Social Science Studies. 2019;4:20. doi: 10.20849/ajsss.v4i1.554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong F.Y., Yang L., Yuen J.W.M., Chang K.K.P., Wong F.K.Y. Assessing quality of life using WHOQOL-BREF: a cross-sectional study on the association between quality of life and neighborhood environmental satisfaction, and the mediating effect of health-related behaviors. BMC Publ. Health. 2018;18:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5942-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dargah M. Faculty of The Chicago School of Professional Psychology; 2017. The Impact of Vipassana Meditation on Quality of Life. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyanaponika . Kandy; Buddhist Publication Society; 2006. The Five Mental Hindrances and Their Conquest Selected Texts from the Pali Canon and the Commentaries Compiled and Translated by.https://www.bps.lk/olib/wh/wh026_Nyanaponika_Five-Mental-Hindreances-and-Their-Conquest.pdf Available: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abblett M. First Eddition. Colorado. Shambhala publications, Inc.; 2018. The five hurdles to happiness: and the mindful path to overcoming them - mitch abblett - google books.https://books.google.lk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=UuDrDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=meditation+inhibits+five+hindrances&ots=wsmttseDuf&sig=9KZI-p9WVChekRNjFXbYlDHVHLA&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false Available: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lea J., Cadman L., Philo C. Changing the habits of a lifetime? Mindfulness meditation and habitual geographies. 2014;22:49–65. doi: 10.1177/1474474014536519. 101177/1474474014536519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ee C., Singleton A.C., de Manincor M., Elder E., Davis N., Mitchell C., et al. A qualitative study exploring feasibility and acceptability of acupuncture, yoga, and mindfulness meditation for managing weight after breast cancer. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2022;21 doi: 10.1177/15347354221099540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sieja J. Eastern Michigan University; 2019. Mindfulness-based Meditation and its Effects on College Students.https://commons.emich.edu/honors/626 Available: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steg L., Vlek C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour : an integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009;29:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacob J., Jovic E., Brinkerhoff M.B. Personal and planetary well-being: mindfulness meditation, pro-environmental behavior and personal quality of life in a survey from the social justice and ecological sustainability movement. Soc Indic Res. 2009;93:275–294. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9308-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dharmesti M., Merrilees B., Winata L. “I'm mindfully green”: examining the determinants of guest pro-environmental behaviors (PEB) in hotels. J. Hospit. Market. Manag. 2020;00:1–18. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2020.1710317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grabow M., Bryan T., Checovich M.M., Converse A.K., Middlecamp C., Mooney M., et al. Mindfulness and climate change action: a feasibility study. Sustainability. 2018;10:1–24. doi: 10.3390/su10051508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunecke M., Richter N. Mindfulness, construction of meaning, and sustainable food consumption. Mindfulness (N Y). 2019;10:446–458. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-0986-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panno A., Giacomantonio M., Carrus G., Maricchiolo F., Pirchio S., Mannetti L. Mindfulness, pro-environmental behavior, and belief in climate change: the mediating role of social dominance. Environ. Behav. 2018;50:864–888. doi: 10.1177/0013916517718887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiermann U.B., Sheate W.R., Vercammen A., Dumitru A.C. vol. 11. 2020. pp. 1–18. (Practice Matters : Pro-environmental Motivations and Diet-Related Impact Vary with Meditation Experience). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riordan K.M., MacCoon D.G., Barrett B., Rosenkranz M.A., Chungyalpa D., Lam S.U., et al. Does meditation training promote pro-environmental behavior? A cross-sectional comparison and a randomized controlled trial. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022;84 doi: 10.1016/J.JENVP.2022.101900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett B., Grabow M., Middlecamp C., Mooney M., Checovich M.M., Converse A.K., et al. Mindful climate action: health and environmental co-benefits from mindfulness-based behavioral training. Sustainability. 2016;8 doi: 10.3390/su8101040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geiger S.M., Otto S., Schrader U. vol. 8. 2018. pp. 1–11. (Mindfully Green and Healthy : an Indirect Path from Mindfulness to Ecological Behavior). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thiermann U.B., Sheate W.R. Motivating individuals for social transition: the 2-pathway model and experiential strategies for pro-environmental behaviour. Ecol. Econ. 2020;174 doi: 10.1016/J.ECOLECON.2020.106668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wamsler C., Osberg G., Osika W., Herndersson H., Mundaca L. Linking internal and external transformation for sustainability and climate action: towards a new research and policy agenda. Global Environ. Change. 2021;71 doi: 10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2021.102373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.IPCC Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Summaries, frequently asked questions, and cross-chapter boxes. Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2009.11.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown K.W., Kasser T. Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Soc Indic Res. 2005;74:349–368. doi: 10.1007/s11205-004-8207-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amel E.L., Manning C.M., Scott B.A. Mindfulness and sustainable behavior: pondering attention and awareness as means for increasing green behavior. Ecopsychology. 2009;1:14–25. doi: 10.1089/eco.2008.0005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barbaro N., Pickett S.M. Mindfully green : examining the effect of connectedness to nature on the relationship between mindfulness and engagement in pro-environmental behavior. PAID. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanley A.W., Bettmann J.E., Kendrick C.E., Deringer A., Norton C.L. Dispositional mindfulness is associated with greater nature connectedness and self-reported ecological behavior. Ecopsychology. 2020;12:54–63. doi: 10.1089/eco.2019.0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang Y., Gruber J., Gray J.R. Emotion Review. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2013. Mindfulness and de-automatization; pp. 192–201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chatzisarantis N.L.D., Hagger M.S. Mindfulness and the intention- behavior relationship within the theory of planned behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007;33:663–676. doi: 10.1177/0146167206297401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee J., Weiss A., Ford C.G., Conyers D., Shook N.J. The indirect effect of trait mindfulness on life satisfaction through self-esteem and perceived stress. Curr. Psychol. 2022:1–13. doi: 10.1007/S12144-021-02586-7/METRICS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Outschoorn N.O. vols. 1–19. 2022. (Development of “ the Colombo Intake Interview to Identify Skilled Meditators for Scientific Research). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yates J. The mind illuminated. 2017. https://www.academia.edu/36926981/John_Yates_Culadasa_with_J_Graves_M_Immergut_The_Mind_Illuminated_pdf

- 46.Faul F., Erdfelder E., Bunchner A., Lang A. Statistical power analyses using G ∗ Power 3 . 1 :Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schoemann A.M., Boulton A.J., Short S.D. vol. 8. 2017. pp. 379–386. (Determining Power and Sample Size for Simple and Complex Mediation Models). 101177/1948550617715068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Somarathne E.A.S.K., Lokupitiya E., Gunathunga M.W. Open University; Sri Lanka: 2021. Adaptation And Validation of The Connectedness To Nature Scale for the use In Sri Lanka.https://ours.ou.ac.lk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ID-56_ADAPTATION-AND-VALIDATION-OF-THE-CONNECTEDNESS-TO-NATURE-SCALE-FOR-THE-USE-IN-SRI-LANKA-.pdf Available: [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baer R.A., Smith G.T., Hopkins J., Krietemeyer J., Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13:27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Outschoorn N.O., Herath H.M.J.C., Amarasuriya S.D. CONTENT VALIDATION THROUGH EXPERT JUDGEMENT AND INTERNAL CONSISTENCY. Sri Lanka Open University; Colombo: 2021. Sinhala version of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ-39-SIN) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baminiwatta A., Alahakoon H., Herath N.C., Kodithuwakku K.M., Nanayakkara T. Psychometric evaluation of a sinhalese version of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire and development of a six-facet short form in a Sri Lankan buddhist context. Mindfulness (N Y) 2022;13:1069–1082. doi: 10.1007/S12671-022-01863-1/METRICS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.IPCC Volume 1 Chapter 4: Methodological Choice and Identification of Key Categories. 2006:1–30. https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/pdf/1_Volume1/V1_4_Ch4_MethodChoice.pdf Available: [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guidelines I., Greenhouse N., Inventories G. Chapter 1: introduction (principles for developing the guidelines) Respirology. 2006;11:1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00937_1.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.WBCSD/WRI GHG Protocol. 2004. http://www.ghgprotocol.org/standards/corporate-standard

- 55.Jayawardena R., Herath M.P. Development of a food atlas for Sri Lankan adults. BMC Nutr. 2017;3 doi: 10.1186/s40795-017-0160-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nette A., Wolf P., Schlüter O., Meyer-Aurich A. A comparison of carbon footprint and production cost of different pasta products based on whole egg and pea flour. Foods. 2016;5:1–13. doi: 10.3390/foods5010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ministry of Health S.L. Nutrition division Ministry of health 2 nd edition 2011. collaboration with World Health Organization Food Based Dietary GUIDELINES for S R I L A N K A N S. 2011;99 http://www.fao.org/3/as886e/as886e.pdf Available: [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rahman M.M., Roy T.S., Chowdhury I.F., Afroj M., Bashar M.A. Identification of physical characteristics of potato varieties for processing industry in Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Bot. 2017;46:917–924. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carlsson-Kanyama A., González A.D. Potential contributions of food consumption patterns to climate change. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;89:1704–1709. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Audsley E., Brander M., Chatterton J., Murphy-bokern D., Webster C., Williams A. How Low Can We Go? An assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from the UK food system and the scope to reduce them by 2050. WWF-UK and Food Climate Research Network. 2009:1–83. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:HOW+LOW+CAN+WE+GO?#0%255Cn http://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/how_low_report_1.pdf Available: [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clune S., Crossin E., Verghese K. Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories. J. Clean. Prod. 2017;140:766–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elapata M.S., Silva A De. 2018. Ecological and Energy Foot Print of Fish Processing in the Southern Coast of Sri Lanka. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Munasinghe M., Deraniyagala Y., Dassanayake N., Karunarathna H. Economic, social and environmental impacts and overall sustainability of the tea sector in Sri Lanka. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2017;12:155–169. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2017.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pathak H., Jain N., Bhatia A., Patel J., Aggarwal P.K. Carbon footprints of Indian food items. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010;139:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2010.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.IPCC Climate Change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel. Genebra, Suíça. 2007 doi: 10.1256/004316502320517344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Energy Consumption Calculator - Lanka Electricity Company (Pvt) Ltd. [cited 27 Jan 2024]. Available: https://www.leco.lk/energyCal_e.php.

- 67.Power Consumption of Typical Household Appliances. [cited 27 Jan 2024]. Available: https://www.daftlogic.com/information-appliance-power-consumption.htm.

- 68.Schmitz S., Dawson B., Spannagle M., Thomson F., Koch J., Eaton R. 2000. A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brander A.M., Sood A., Wylie C., Haughton A., Lovell J., Reviewers I., et al. Ecometrica; 2011. Electricity-specific Emission Factors for Grid Electricity; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 70.IPCC Good practice IPCC Good Practice Guidance and Uncertainty Management in National Greenhouse Gas Inventories . 2000. Waste. Montral: Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- 71.IPCC . 2014. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Working Group III Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumarapeli V., Seneviratne R. de A., Wijeyaratne C.N. Validation of WHOQOL-BREF to measure quality of life among women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of the College of Community Physicians of Sri Lanka. 2006;11:1. doi: 10.4038/jccpsl.v11i2.8252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hayes A.F., Scharkow M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013;24:1918–1927. doi: 10.1177/0956797613480187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Preacher K.J., Hayes A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anicha C.L., Ode S., Moeller S.K., Robinson M.D. Toward a cognitive view of trait mindfulness: distinct cognitive skills predict its observing and nonreactivity facets. J. Pers. 2012;80:255–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Josefsson T., Larsman P., Broberg A.G., Lundh L.G. Self-reported mindfulness mediates the relation between meditation experience and psychological well-being. Mindfulness (N Y) 2011;2:49–58. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0042-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tang Y.Y., Lu Q., Fan M., Yang Y., Posner M.I. Mechanisms of white matter changes induced by meditation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10570–10574. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.1207817109/ASSET/615B9D4E-0502-4104-8D73-DD0D32C8D099/ASSETS/GRAPHIC/PNAS.1207817109FIG04.JPEG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mantzios M., Giannou K. Group vs. single mindfulness meditation: exploring avoidance, impulsivity, and weight management in two separate mindfulness meditation settings. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2014;6:173–191. doi: 10.1111/APHW.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Khoury B., Sharma M., Rush S.E., Fournier C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: a meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015;78:519–528. doi: 10.1016/J.JPSYCHORES.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Creswell J.D. Mindfulness interventions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2017;68:491–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hölzel B.K., Carmody J., Evans K.C., Hoge E.A., Dusek J.A., Morgan L., et al. Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2010;5:11–17. doi: 10.1093/SCAN/NSP034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lutz A., Jha A.P., Dunne J.D., Saron C.D. Investigating the phenomenological matrix of mindfulness-related practices from a neurocognitive perspective. Am. Psychol. 2015;70:632–658. doi: 10.1037/A0039585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zeidan F., Martucci K.T., Kraft R.A., Gordon N.S., Mchaffie J.G., Coghill R.C. 2011. Behavioral/Systems/Cognitive Brain Mechanisms Supporting the Modulation of Pain by Mindfulness Meditation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lutz A., Slagter H.A., Dunne J.D., Davidson R.J. Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chiesa A., Serretti A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. J. Alternative Compl. Med. 2009;15:593–600. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Garland E.L., Farb N.A., R, Goldin P., Fredrickson B.L. Mindfulness Broadens Awareness and Builds Eudaimonic Meaning: A Process Model of Mindful Positive Emotion Regulation. 2015;26:293–314. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294. 101080/1047840X20151064294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Barbaro N., Pickett S.M. Mindfully green : examining the effect of connectedness to nature on the relationship between mindfulness and engagement in pro-environmental behavior. PAID. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Howell A.J., Dopko R.L., Passmore H.A., Buro K. Nature connectedness: associations with well-being and mindfulness. Pers Individ Dif. 2011;51:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bowles M.A. Measuring implicit and explicit attitudes. Stud. Sec. Lang. Acquis. 2011:247–271. doi: 10.1017/S0272263110000756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lengyel A. Mindfulness and sustainability: utilizing the tourism context. J. Sustain. Dev. 2015;8:35. doi: 10.5539/jsd.v8n9p35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Franquesa A, Cebolla A, García-Campayo J, Demarzo M, Elices M, Carlos Pascual J, et al. Meditation Practice Is Associated with a Values-Oriented Life: the Mediating Role of Decentering and Mindfulness. doi:10.1007/s12671-017-0702-5.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.