Abstract

Background

Chemosensory perception plays a vital role in insect survival and adaptability, driving essential behaviours such as navigation, mate identification, and food location. This sensory process is governed by diverse gene families, including odorant-binding proteins (OBPs), olfactory receptors (ORs), ionotropic receptors (IRs), chemosensory proteins (CSPs), gustatory receptors (GRs), and sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs). The oriental mole cricket (Gryllotalpa orientalis Burmeister), an invasive pest with an underground, phyllophagous lifestyle, causes substantial crop damage. This study characterizes the chemosensory gene repertoire of G. orientalis based on de novo genome assembly and transcriptomic analysis.

Results

We present a draft genome of G. orientalis at the scaffold level, spanning 2.94 Gb and comprising 10,497 scaffolds. This assembly encodes 19,155 protein-coding genes, including 158 chemosensory genes: 30 odorant receptors (ORs), 64 ionotropic receptors (IRs), ten gustatory receptors (GRs), 28 odorant-binding proteins (OBPs), 25 chemosensory proteins (CSPs), and a single sensory neuron membrane protein (SNMP). Expression analysis indicated that 71 chemosensory genes were actively expressed in the head, thorax, and legs, with ORs and OBPs showing higher expression in the head and legs. In contrast, GRs and IRs were predominantly expressed in the head.

Conclusions

This study provides the first comprehensive identification of chemosensory gene families in the G. orientalis genome, characterized as a scaffold-level draft genome. These findings provide a basis for future functional studies and highlight the role of chemoreception in the subterranean environment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-025-11217-5.

Keywords: Mole cricket, Genome assembly, Chemosensory genes identification, Transcriptome analysis, Differential expression

Background

The Oriental mole cricket, Gryllotalpa orientalis, is a significant representative of the Gryllotalpoidea superfamily, which includes 221 species across 20 genera [1]. It primarily inhabits southeastern Asia, including countries such as China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, India, and Pakistan, with occasional sightings in Europe and Africa [2, 3]. G. orientalis is recognized by its yellowish-brown coloration, oblong pronotum, short, filiform antennae, and uniquely adapted, robust forelegs that allow efficient burrowing. Its herbivorous feeding poses a significant economic threat to agriculture, as it consumes a variety of crop roots, such as corn, sugarcane, and tobacco [2]. By voraciously consuming plant roots, it not only reduces crop yields but also increases the susceptibility of plants to diseases and environmental stressors. The root damage inflicted by G. orientalis affects soil structure and can lead to ecosystem imbalances, impacting biodiversity within farmland and turfgrass systems [4]. Despite its substantial agricultural impact, studies have largely focused on its ecological traits, including physiology [5], burrowing behavior [6–8], feeding habits, life cycle [9], and specialized adaptations to preferred vegetation [10]. However, research on its genetic composition remains limited, creating a gap in understanding its adaptations to subterranean life and the mechanisms underlying its environmental resilience and specialized feeding. The genetic foundation of G. orientalis could illuminate the adaptive strategies that enable survival in its unique ecological niche.

Insects living in specific ecological niches rely on the olfactory system to perceive and interpret chemical cues essential for survival, such as finding food, selecting mates, avoiding predators, and locating suitable oviposition sites [11]. Chemosensory perception is mediated by a variety of protein families, including odorant-binding proteins (OBPs), odorant receptors (ORs), chemosensory proteins (CSPs), ionotropic receptors (IRs), and gustatory receptors (GRs). These chemosensory proteins play pivotal roles in detecting environmental chemical signals and triggering sensory processes facilitated by specialized structures and chemoreceptors [12]. Chemosensory perception is particularly significant for insects that live underground or have foraging lifestyles, such as burrowing beetles [13], ants [14], and termites [15]. These insects possess diverse chemosensory genes that enable them to adapt to their specific ecological niches. These genes are essential for mediating behaviors crucial for survival in underground environments and contribute to the ecology and evolution of subterranean insect species [16].

ORs are mainly found in olfactory sensory neurons located in the antennae and maxillary palps, where they detect volatile compounds. ORs, part of the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family, possess seven transmembrane domains typically spanning 300 to 500 amino acids. These receptors are categorized into nine major groups, in addition to a conserved coreceptor known as Orco. All Dicondylia (Zygentoma + Pterygota) contain a single, highly conserved Orco receptor, which shares more than 70% of homology across insect taxa [12]. In contrast, the variable OR genes, exhibiting around 20% homology, have diversified within different insect lineages, likely responding to distinct ecological pressures. Each OR forms a ligand-gated ion channel when paired with Orco, enabling the detection of a broad array of odorant molecules [13]. The extensive diversity and specialization of ORs across species make them a key subject of study for understanding how insects adapt their olfactory capabilities to various ecological contexts. OBPs, known for their significant sequence variability, are small, soluble proteins initially identified within olfactory appendages. These proteins are now recognized in other chemosensory and non-chemosensory tissues and perform crucial functions such as binding, solubilizing, and transporting hydrophobic stimuli to chemoreceptors within the sensilla lymph. OBPs are typically classified into four structural groups based on the number and arrangement of conserved cysteine residues: Classic, Plus-C, Minus-C, and Atypical OBPs [17]. Their primary functions include binding, solubilizing, and transporting hydrophobic stimuli to chemoreceptors across the aqueous sensilla lymph. Besides their role in chemoreception, OBPs are hypothesized to buffer rapid changes in odorant levels and contribute to hygro-reception by assisting in the detection of humidity and moisture levels, particularly beneficial in subterranean environments where such conditions are less stable [18].

IRs are descendants of the evolutionarily conserved family of ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs), originating in the basal lineage of the Protostomia clade [12, 19]. IRs possess two extracellular ligand-binding domains and three transmembrane domains, and they are mainly divided into two groups: antennal IRs, primarily expressed in antennal neurons, and divergent IRs, predominantly expressed in non-antennal tissues. IRs interact with coreceptors IR8a and IR25a, which play roles analogous to Orco in ORs, assisting in targeting sensory cilia and tuning IR-based sensory channels [20, 21]. IRs are believed to participate in sensing acids, amines, and amino acids. They may also respond to temperature, humidity, and pH levels, facilitating chemosensory, thermo-sensory, and hygro-sensory responses critical for adaptation to subterranean life [21, 22].

GRs are primitive evolved chemosensory receptors in arthropods and exhibit a conserved structural motif with seven transmembrane domains and approximately 300–500 amino acids [23]. GRs are broadly distributed across various tissues and categorized into four main subfamilies based on their binding ligands: carbon dioxide, fructose, sugar, and bitter receptors [12]. These receptors contribute to various chemosensory behaviors, including detecting taste and non-volatile chemicals. These are especially relevant for soil-dwelling insects that rely on close-range chemical cues in a tactile environment. In addition to ORs, IRs, and GRs, chemosensory proteins (CSPs) are characterized by six alpha-helices surrounding a hydrophobic binding pocket [17]. Though CSPs are commonly involved in signal transmission, they are not confined to chemosensory organs and participate in developmental processes and immune responses [24]. In certain social insects, CSPs play roles in pheromone recognition and nest-mate discrimination, supporting social cohesion and colony defense mechanisms [14].

Most of the research on insect chemoreception is based on Lepidoptera, Diptera, and Coleoptera; limited data exist for Orthoptera, with sequences reported for species such as Locusta migratoria [25–27], Oedaleus asiaticus [28], Ceracris kiangsu [29], Shistocerca gregaria [30]. This study aims to fill the knowledge gap by constructing a high-quality nanopore genome assembly of G. orientalis and examining the diversity and expression patterns of six chemosensory gene families: ORs, OBPs, IRs, GRs, CSPs, and SNMP. We will investigate these gene profiles, evolution, phylogenetic relationships, and spatial expression patterns to enhance our understanding of the genetic basis for adaptation to subterranean environments.

Methods

Sample collection and nucleic acid extraction

G. orientalis samples were collected from natural populations in Suqian City, Jiangsu Province, China (33.9619° N, 118.2755° E). Twelve live specimens were brought to the laboratory, where the whole body of one male was used for DNA extraction to attain comprehensive genomic content. For RNA extraction, three male individuals’ heads, thoraxes, and legs were separately processed to investigate tissue-specific gene expression. Genomic DNA and RNA were extracted using the Tiangen Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) following standard protocols [31].

Library preparation and sequencing

The Illumina library was prepared from 1.5 µg of DNA, fragmented with g-TUBE, repaired, ligated with adaptors, and subjected to exonuclease digestion and 350-bp size selection, then sequenced on the Illumina X-ten platform. For Nanopore sequencing, 5 µg of DNA with a 20 kb average fragment length was prepared using the SQK-LSK109 kit and sequenced on the PromethION platform. Nine tissue-specific cDNA libraries were also prepared with the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit, involving RNA enrichment, fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, end repair, dA tailing, adaptor ligation, and PCR enrichment. Libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 high-throughput sequencing platform, obtaining a sequencing length of 2 × 150 bp.

Genome assembly

Each Nanopore and Illumina raw read was processed for quality assessment using FastQC v0.11.6 [32]. Illumina reads were filtered and trimmed with Trimmomatic v0.39 [33] under default parameters (adapter removal enabled; sliding window = 4 bp, Q15; leading/trailing trim = Q3; length filter = < 50 bp, and quality scores converted to Phred-33). For Nanopore reads, NanoFilt v2.3.0 [34] was employed with default settings (minimum quality score = 20; length filter = < 200 bp; GC content filter = 0–100%). Filtered Illumina and Nanopore reads were combined to construct a hybrid assembly using WTDBG v1.2.8 [35], followed by super scaffold generation with CANU v1.4.1 [36]. Pilon v1.24 [37] was used to polish the assembly, enhancing base-level accuracy. The completeness of the genome assembly and predicted gene set was assessed using BUSCO v5.8.0 [38] and the OrthoDB v10 Insecta database [39]. The raw sequencing reads were re-mapped to the assembled genome using BWA v0.7.17-r1188 [40] with an optimized MEM setting for maximum accuracy. The assembled data have been deposited in GenBank under the Project Accession Number PRJNA1202218, with a BioSample Accession Number SAMN45954316.

Genome annotation

A combination of de novo and homology-based approaches was employed to identify repetitive sequences in the G. orientalis genome. Repetitive elements were annotated using RepeatModeler v1.0.11 [41] for de novo repeat library construction with default parameters. Genome screening was performed with RepeatMasker v4.0.5 against the arthropod Repbase and transposable element databases [42]. Gene prediction utilized both ab initio and homology-based methods. RNA-seq data were pre-assembled using Trinity v2.5.1 [43], and transcriptome sequences were mapped to the genome for gene model refinement using PASA v2.5.1 [44]. For ab initio prediction, Augustus v3.3 [45] and SNAP (http://snap.humgen.au.dk) were employed. In contrast, homologous protein sequences from related Orthoptera species were downloaded, concatenated, and searched using GeneWise v2.4.1 [46]. Pseudogenes were excluded based on translation errors or the presence of premature stop codons. The final non-redundant gene set was generated by integrating ab initio and homology-based predictions using MAKER v2.31.11 [47] and merging them with EVM v1.1.1 [48]. Functional annotation of predicted genes was performed using several bioinformatics tools and databases. BLAST (http://ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/db/) aligned gene sequences against the NR database with an e-value threshold of 1e-5 [49]. Gene Ontology (GO) terms were assigned using Blast2GO v4.1R (https://www.blast2go.com) [50]Metabolic pathway annotation was conducted using the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS; https://www.kegg.jp/) [51]. Protein family classification and domain prediction were performed using InterProScan v5.60–92.0 [52], and additional domain predictions were validated using Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/).

Chemosensory genes identification and comparative analysis

The chemosensory gene families were identified in G. orientalis using a homology-based search approach, leveraging DIAMOND and the NCBI non-redundant (Nr) protein database. Protein sequences from G. orientalis were queried against a custom DIAMOND database constructed from established sequences of key chemosensory gene families, including odorant receptors (ORs), ionotropic receptors (IRs), gustatory receptors (GRs), odorant-binding proteins (OBPs), chemosensory proteins (CSPs), and sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs). To achieve specificity, hits were filtered using an E-value threshold of 1e-05, along with defined identity and coverage criteria to ensure the accuracy of identified sequences. For validation, a secondary DIAMOND BLASTp search was conducted against the NCBI non-redundant (Nr) protein database, retaining only those sequences where the top hit displayed greater than 90% similarity to the anticipated gene family. Open reading frames (ORFs) of the candidate chemosensory genes were identified using the ORF Finder tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html). Signal peptides for candidate CS genes were predicted using SignalP 4.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) [53]. Transmembrane domains in novel CS genes were predicted using TMHMM server v2.0 [54].

The same strategy was applied to Locusta migratoria (GCA_000516895.1) and Gryllus bimaculatus (GCA_017312745.1) to confirm the CS genes. The annotated candidate gene sequences were aligned using MAFFT (v7.453) [55]. These alignments were used to infer the phylogeny of the five gene families using IQ-TREE2 [56] with a GTR model and 1000 bootstrap replicates. The final phylogenetic trees were visualized and customized using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) toolkit [57]. The trees were annotated based on gene family and subfamily annotations from previously published work [11, 25].

Expression profiling of chemosensory genes in head thorax and legs

Gene expression levels were quantified using the fragments per kilobase per million mapped fragments (FPKM) method [58]. RNA-Seq reads from three distinct tissues were aligned to the genome using HISAT2 v2.1.0 [59] and gene expression levels were calculated using StringTie v2.0.6 [60]. Expression analysis was performed using edgeR v3.32.1 [61] to identify significantly differentially expressed genes. Hierarchical clustering and gene expression visualization were conducted using the Heatmap tool in TBtools v2.042 [62]. This workflow enabled a detailed analysis of chemosensory gene expression patterns across body parts.

Validation of tissue-specific expression analyses by qRT-PCR

To validate the tissue-specific expression patterns of 20 chemosensory genes identified in the transcriptome analysis of adult male G. orientalis, qRT-PCR was conducted. Total RNA was extracted from tissue samples using the Sangon Biotech Animal Total RNA Isolation Kit (Sangon, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was carried out using the Vazyme HiScript® II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (+ gDNA wiper) (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) to remove genomic DNA contamination. ß-actin serves as the internal reference gene. Primers were designed using NCBI Primer-BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). qRT-PCR was conducted using the Accurate Biology SYBR Green Premix Pro TaqHS qPCR Kit (High Rox Plus) (Accurate Biology, Hubei, China). Reactions were performed with three replicates on a Thermo Fisher StepOne™ Real-Time PCR System under the following conditions: 95 °C for 30 s; 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s; 65 °C to 95 °C in increments of 0.5 °C. The relative expression levels of genes were calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method, normalized against ß-actin. One-way ANOVA analysis was applied to compare the expression levels between tissues. Data visualization and analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism v10.1.2.

Results

Genome assembly completeness statistics

Nanopore sequencing of G. orientalis generated 286.02 GB of raw data, providing approximately 70× genome coverage. After quality filtering, 217.01 GB of clean reads were retained. The final draft genome assembly comprised 10,497 contigs with a combined length of 2.94 Gb with a GC content of 39.19% (Fig. 1b). This assembly achieved a contig N50 of 2.78 Mb and a median contig length of 280.3 Kb, with the longest contig measuring 28.33 Mb (Fig. 1d). Assembly completeness was assessed using BUSCO, which identified 97.2% complete BUSCOs (95.5% single-copy and 1.7% duplicated), 1.0% fragmented, and 1.8% missing, out of the 1,367 groups searched, indicating high assembly quality and robust gene representation. Additionally, BUSCO evaluation of the predicted gene set yielded a completeness score of 91.7%, underscoring the success of gene prediction in capturing essential genes. The assembly accuracy was validated through the re-mapping of NGS reads, which achieved a high alignment rate of 99.30%, with 99.14% mapped as primary alignments. Additionally, 81.73% of the reads were properly paired, and the singleton rate was low (0.21%), highlighting minimal assembly errors and ensuring suitability for downstream analyses.

Fig. 1.

Genomic analysis and features of Gryllotalpa orientalis. (a) Illustration of Gryllotalpa orientalis habitat. (b) The draft plot of genome assembly metrics, including scaffold length, GC content, gene density, and repetitive content, with a genome size of 2.94 Gb. (c) Venn diagram showing gene annotations in GO, KEGG, Swiss-Prot, and NR databases. (d) The summary table of genome assembly features includes scaffold count, lengths, GC content, N50, annotated genes, and complete BUSCOs

Genome annotation

The genome assembly of G. orientalis predicted a total of 19,155 protein-coding genes, with an average gene length of 11,648 bp. The average coding sequence (CDS) length was 1,030 bp, containing an average of 4.31 exons per gene. Introns constituted a significant portion of the genome, with an average length of 10,617,77 bp, notably surpassing the average exon length. Amino acid composition analysis identified 8,198 amino acids, with leucine (8.6%) and serine (8.5%) being the most abundant residues. Noncoding RNAs were also annotated, including 68 rRNAs with a total length of 57,159 bp and 320 tRNAs totaling 22,384 bp, which are potentially valuable for phylogenetic studies due to their conserved nature. Repetitive elements accounted for 52.79% of the genome, with DNA transposons (46.39%), long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs, 33.69%), and simple repeats (11.88%) being the most abundant categories. Together, these three categories comprised over 91% of the total transposable element content, while short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) were minimal (< 0.01%).

Gene annotation across public databases revealed that 17,969 genes (87.58%) had homologs in the NR database, 8,716 genes (42.48%) in the GO database, 13,812 genes (67.32%) in the COG database, 5,797 genes (28.85%) in the KEGG database, and 14,994 genes (78.24%) in the Swiss-Prot database. KEGG pathway analysis identified genes involved in key pathways such as metabolism, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, genetic and environmental information processing, and signal transduction. The top five KEGG pathways by gene count included signal transduction (374 genes), transport and catabolism (293 genes), translation and degradation (240 genes), the immune system (216 genes), and environmental adaptation (134 genes). Genes associated with human diseases were also identified, including pathways related to cancer (345 genes), infectious diseases (301 genes), and neurodegenerative disorders. Gene ontology (GO) analysis categorized the identified genes into biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions. The majority were associated with molecular functions, particularly transport and catalytic activities, followed by genes involved in cellular processes under biological processes. Cellular component-associated genes were primarily localized to membranes and organelles, highlighting their roles in intracellular and membrane-associated activities.

Comparative analysis of chemosensory (CS) genes

A comprehensive search of the G. orientalis genome identified 158 putative chemosensory (CS) genes, which were manually verified and curated. The gene set includes 64 ionotropic receptors (IRs), 28 odorant-binding proteins (OBPs), 30 odorant receptors (ORs), 10 gustatory receptors (GRs), 25 chemosensory proteins (CSPs), and one sensory neuron membrane protein (SNMP). For comparative analysis, CS genes from two additional Orthoptera species, L. migratoria and G. bimaculatus, were obtained from the NCBI databases (Table 1). Phylogenetic trees were subsequently constructed for each gene family, including ORs (Fig. 2), OBPs (Fig. 3), IRs (Fig. 4), GRs (Fig. 5), and CSPs (Fig. 6).

Table 1.

CS gene counts in G. Orientalis and Orthoptera species (G. Bimaculatus and L. Migratoria)

| Species name | ORs | OBPs | IR | GR | CSP | SNMP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G. orientalis | 30 | 28 | 64 | 10 | 25 | 1 |

| G.bimaculatus | 23 | 14 | 30 | 13 | 4 | 5 |

| L.migratoria | 144 | 24 | 32 | 77 | 20 | - |

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic construction of odorant receptors (ORs) genes observed in the genome of G. orientalis compared with G. bimaculatus and L. migratoria. Relevant clades, following the classification in [15], are colour-coded. Putative orthologs in G. orientalis are highlighted in red. The tree is rooted in the conserved Orco group. Branch support (circles at the branch nodes) was estimated using an approximate likelihood ratio test based on the scale on the top right. Bars indicate branch lengths in proportion to amino acid substitutions per site. Relevant clades are color-coded

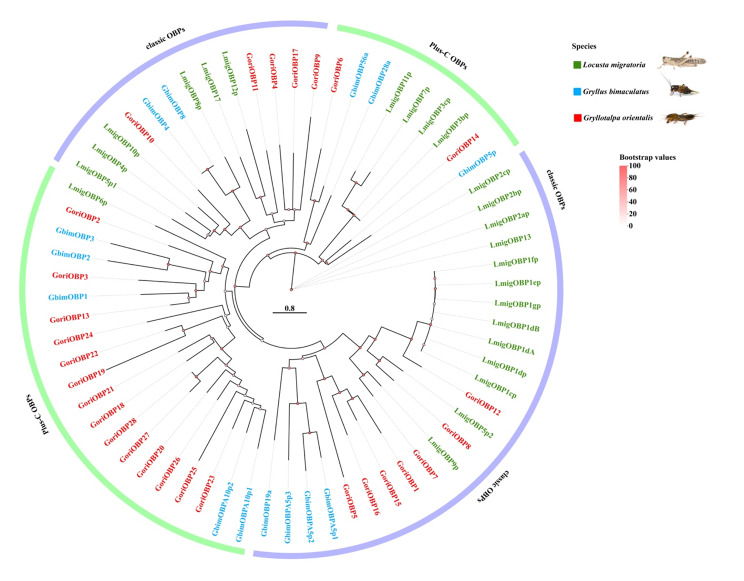

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic construction of odorant-binding proteins (OBPs) genes observed in the genome of G. orientalis compared with G. bimaculatus and L. migratoria. Branch support (circles at the branch nodes) was estimated using an approximate likelihood ratio test based on the scale on the top right. Bars indicate branch lengths in proportion to amino acid substitutions per site. Relevant clades are color-coded

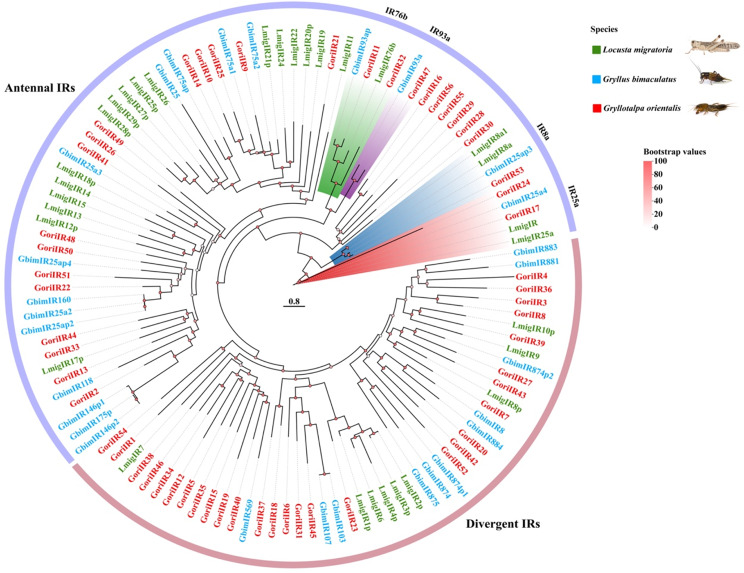

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic construction of ionotropic receptors (IR) genes observed in the genome of G. orientalis compared with G. bimaculatus and L. migratoria. The two annotated clades (antennal and divergent) are color-coded. Putative orthologs in G. orientalis are highlighted in red. Fine-scale subfamily-level annotation of groups is provided in the outermost circle. The different densities of subfamily-level annotation reflect the current limited knowledge of gene-divergent IR subfamilies. The tree is rooted in the conserved IR8a and IR25a clades

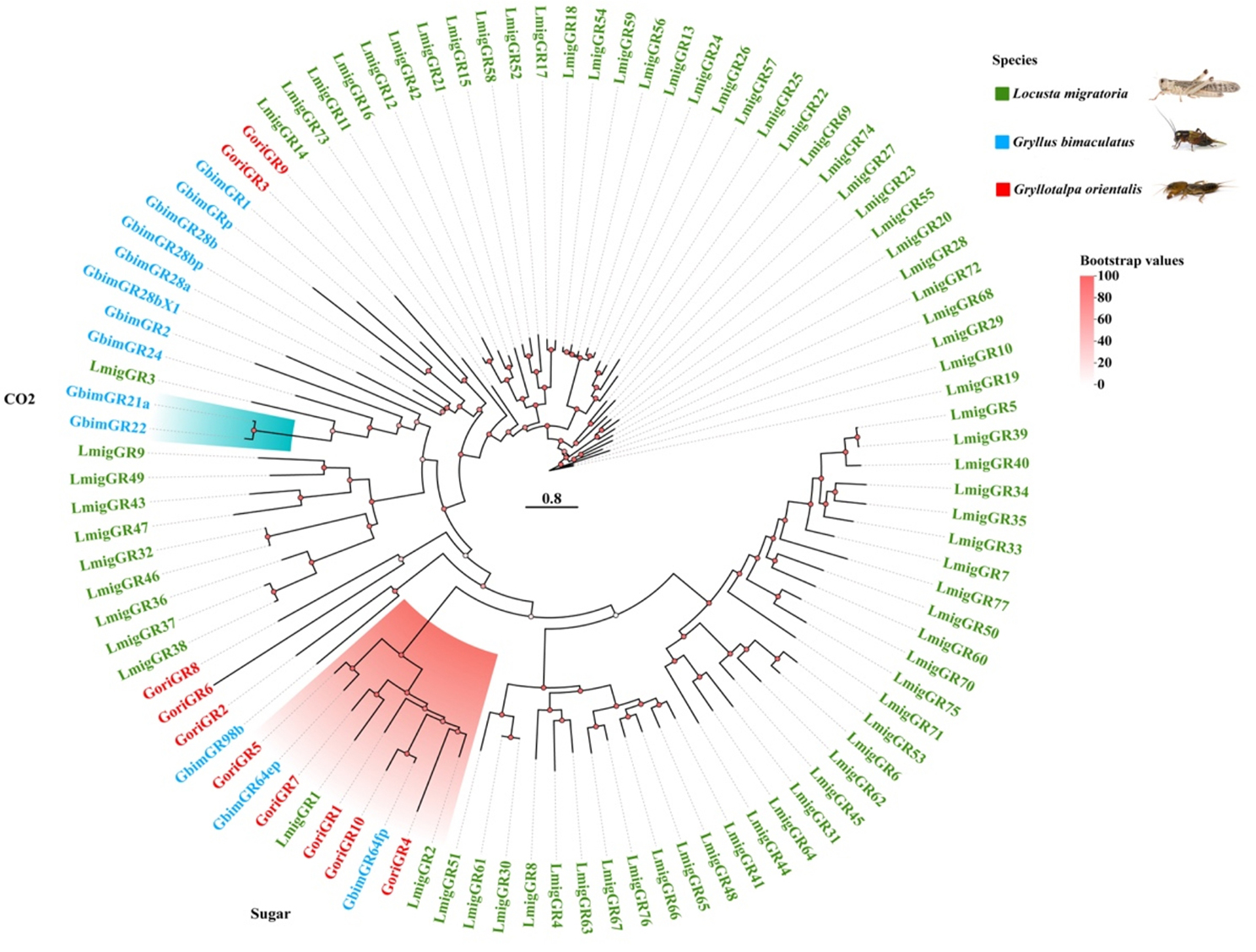

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic construction of Gustatory receptors (GR) genes observed in the genome of G. orientalis compared with G. bimaculatus and L. migratoria. Branch support (circles at the branch nodes) was estimated using an approximate likelihood ratio test based on the scale on the top right. Bars indicate branch lengths in proportion to amino acid substitutions per site. Relevant clades are color-coded

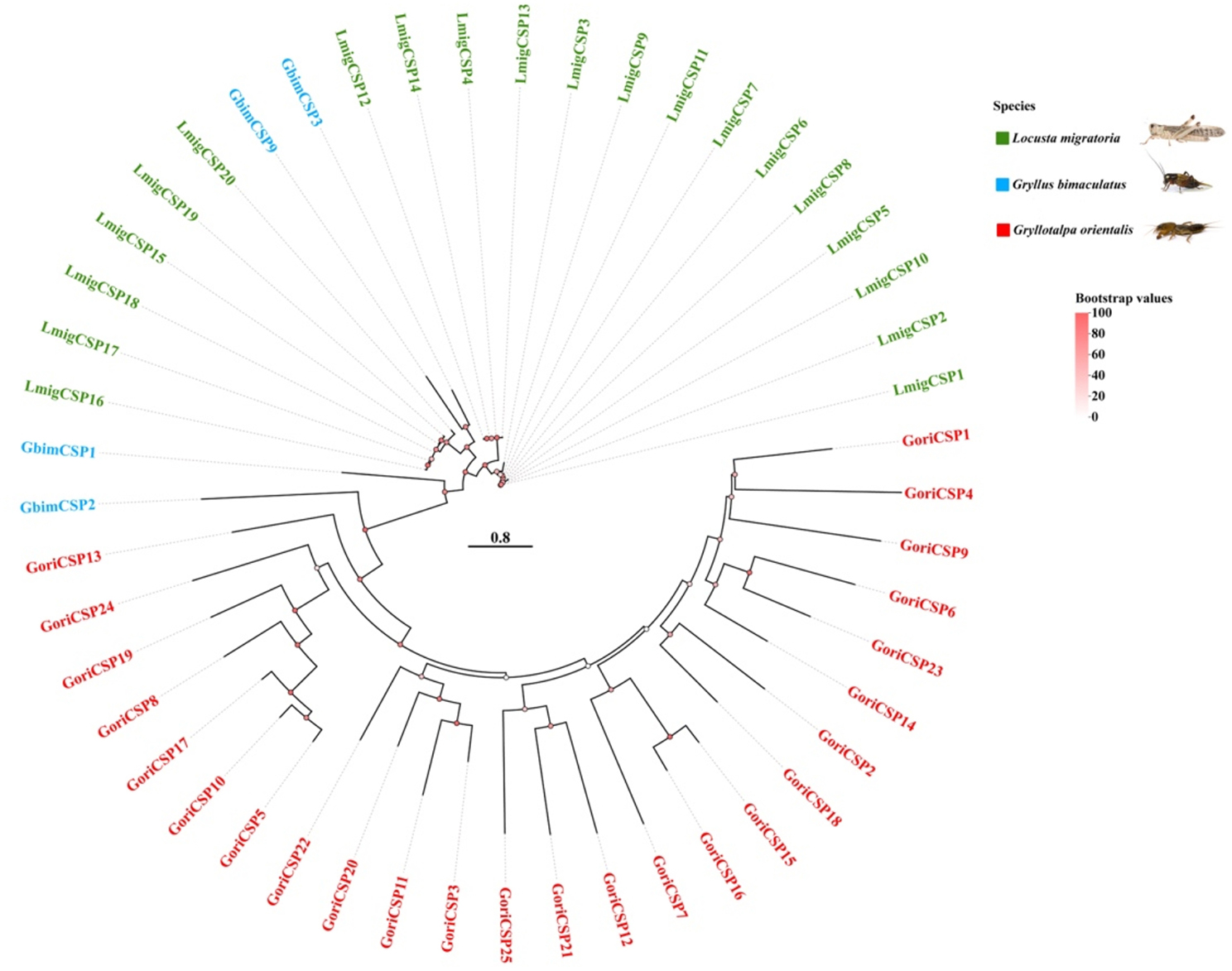

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic construction of CSP genes observed in the genome of G. orientalis compared with G. bimaculatus and L. migratoria. Branch support (circles at the branch nodes) was estimated using an approximate likelihood ratio test based on the scale on the top right. Bars indicate branch lengths in proportion to amino acid substitutions per site. Relevant clades are color-coded

Odorant receptors

A total of 30 odorant receptor (OR) genes were identified in the genome of G.orientalis. Phylogenetic analysis, based on the classification framework proposed by [63], categorized these ORs into three clades: Clade I, Clade II, and the conserved Orco clade (Fig. 2). Clade I comprised 19 genes, representing the largest cluster, whereas Clade II contained a smaller subset of ten genes, organized into two subclades, with all genes clustering within one subgroup. The Orco clade included two orthologous genes that exhibited unique characteristics distinct from those observed in other Orthoptera species. Rooting the phylogeny with the Orco clade, which is the most conserved group, revealed that Clades I and II formed a well-supported, monophyletic cluster. The amino acid lengths of the ORs ranged from 69 to 632 codons, whereas the Orco gene showed a distinct length of 221 codons, consistent with its high degree of functional conservation. Notably, this phylogenetic pattern underscores the strong representation of ORs in Clades I and II while highlighting the absence of Clade III OR genes in G. orientalis.

Odorant binding protein

A total of 28 odorant-binding protein (OBP) genes were identified in the genome. The OBP family is generally categorized into five major subclasses: classic (6 cysteines), minus-C (4 cysteines, lacking C2 and C5), plus-C (8 cysteines and one proline), dimers (two six-cysteine signatures), and atypical (9–10 cysteines and a long C-terminus) [64, 65]. Among these, 12 OBPs were classified as classic, while 14 belonged to the plus-C subclass. The genome did not identify the remaining subclasses, including minus-C, dimers, and atypical OBPs. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the classic OBPs (GoriOBP1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17) were distributed across several clades, forming small subgroups with OBPs from G. bimaculatus and L. migratoria. In contrast, the plus-C OBPs (GoriOBP2, 3, 6, 13, 14, 18–28) clustered within a single, well-defined clade (Fig. 3). The clustering pattern suggests that OBP genes in G. orientalis share higher homology with those of G. bimaculatus compared to L. migratoria, reflecting conserved divergence within the Orthoptera lineage.

Ionotropic receptors

The 64 ionotropic receptor (IR) genes were discerned within the genomic framework of G. orientalis. Phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 4), along with comparative annotations from L. migratoria [25] and G. bimaculatus [66], indicated that IRs are a major chemosensory gene family in G. orientalis. The IR repertoire in G. orientalis includes members of both antennal clades (IR25a, IR8a, IR76b, and IR93a) and divergent clades. The antennal IRs, particularly the conserved subfamilies IR25a and IR8a, formed monophyletic clades in the tree, while the more variable divergent IRs appeared polyphyletic, with some sequences clustering among antennal IRs. Interestingly, a monophyletic clade of G. orientalis IR sequences was identified near the tree’s base, with no known orthologs, tentatively designated as the “G. orientalis IR basal group” [11]. The diversity observed within individual IR subfamilies in G. orientalis corresponds with findings in other orthopteran species. Notably, subfamilies IR8a, IR25a, IR76b, and IR93a each exhibit a single, highly conserved sequence across all three species.

Gustatory receptors

The analysis of gustatory receptors (GRs) in G. orientalis identified ten genes. Phylogenetic analysis and gene annotation revealed two conserved clusters related to sugar and carbon dioxide receptors (Fig. 5). Within the sugar receptor clade, only five GRs (GoriGR3, GoriGR8, GoriGR9, GoriGR13, and GoriGR18) were identified in G. orientalis, fewer than other species. The number of GR genes in G. orientalis is similar to G. bimaculatus (13) but substantially lower than in L. migratoria (77) (Fig. 5), suggesting divergence in gustatory receptor evolution among these species. While three carbon dioxide receptor genes are generally conserved across insect species, none were detected in G. orientalis. Additionally, fructose receptors were absent from the G. orientalis genome. These three subfamilies contribute only minimally to the overall GR gene diversity across species, with many GR genes remaining functionally uncharacterized. The G. orientalis GR repertoire is characterized by few orthologous copies, with substantial paralogy in certain branches (Fig. 5).

Chemosensory protein

A total of 25 chemosensory protein (CSP) genes were identified in the G. orientalis genome. All predicted GoriCSPs contain the highly conserved four-cysteine motif characteristic of CSPs. A phylogenetic tree of GoriCSPs clustering patterns indicative of species-specific expansions and evolutionary trajectories. G. orientalis exhibited notable diversity, forming multiple distinct clusters. The basal clades at the tree’s root include CSPs from both G. bimaculatus (GbimCSP1 and GbimCSP2) and G. orientalis (GoriCSP13 and GoriCSP24), suggesting these CSPs represent some of the earliest-diverging groups. The clustering pattern highlights unique evolutionary pathways, with L. migratoria and G. orientalis showing substantial CSP diversity [63]. The basal positioning of certain G. bimaculatus and G. orientalis CSPs offers insights into early evolutionary events among these proteins (Fig. 6).

Transcriptome data evaluation

We analyzed gene expression profiles using fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM). Initially, 21.99 GB of raw sequencing data was generated. After performing quality trimming and filtering to remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences, this was refined to 21.80 GB of clean data. Our primary goal was to obtain a high-quality dataset, ensuring that over 95% of the sequences were valid for robust FPKM analysis. Detailed sequencing statistics are provided in (Table 2,) offering a comprehensive overview of the transcriptome samples and insights into their characteristics.

Table 2.

Statistical outcomes of the transcriptome sequencing analysis for G. Orientalis

| Sample | Raw Reads | Clean Reads |

|---|---|---|

| Head | 47,802,540 | 47,482,030 |

| Percentage (%) | 100 | 99.32 |

| Thorax | 49,530,304 | 49,259,822 |

| Percentage (%) | 100 | 99.45 |

| leg | 49,325,462 | 49,090,802 |

| Percentage (%) | 100 | 99.52 |

Gene expression pattern of G. Orientalis

Through transcriptome analysis, we identified the expression of 71 chemosensory (CS) genes in G. orientalis, with distribution across different body parts: 52 in the head, 53 in the thorax, and 46 in the legs. These genes include 8 OR genes, 17 OBP genes, 35 IR genes, 6 GR genes, 4 CSP genes, and 1 SNMP gene. FPKM-based expression profiling (Fig. 7) revealed that IR and OR genes were predominantly expressed in the head, with lower expression levels in the thorax and legs. Other gene families showed tissue-specific patterns. For instance, GoriOBP28 exhibited notable expression in the legs but was absent in the head and thorax. Distinct expression patterns were observed in specific genes. The head expressed 12 ionotropic receptor genes (GoriIR17, GoriIR30, GoriIR31, GoriIR37, GoriIR39, GoriIR41, GoriIR44, GoriIR45, GoriIR48, GoriIR49, GoriIR50, GoriIGluR02), the thorax expressed 11 (e.g., GoriIR4, GoriIR11, GoriIR13), and the legs expressed 3 (GoriIR1, GoriIGluR03, GoriIGluR08).

Fig. 7.

Heat map displaying genes’ log value expression levels across three body parts: Head, Thorax, and Leg. The dendrogram on the left represents the hierarchical clustering of the genes on the right side with similar expression profiles. The color gradient ranges from red (high expression) to blue (low expression)

Five gustatory receptor genes (GoriGR3, GoriGR4, GoriGR5, GoriGR7, GoriGR8) showed elevated expression in the head, with minimal expression in the legs and thorax. Consistent expression across all body parts was noted for GoriOR5, GoriGR3, GoriGR4, GoriGR5, GoriGR7, GoriGR8, GoriIR50, and GoriIGluR02. Gene-specific patterns were observed; for example, GoriIR50 had high expression in the head but lower levels in the thorax and legs, suggesting a specialized role in head chemo sensation. GoriOBP22 displayed uniform expression across all regions, indicative of a generalized chemosensory role. Hierarchical clustering grouped genes with similar expression patterns, such as GoriIR54, GoriIR23, and GoriIR50, which were highly expressed in the head and less expressed in other regions.

Validation of chemosensory gene expression by qPCR

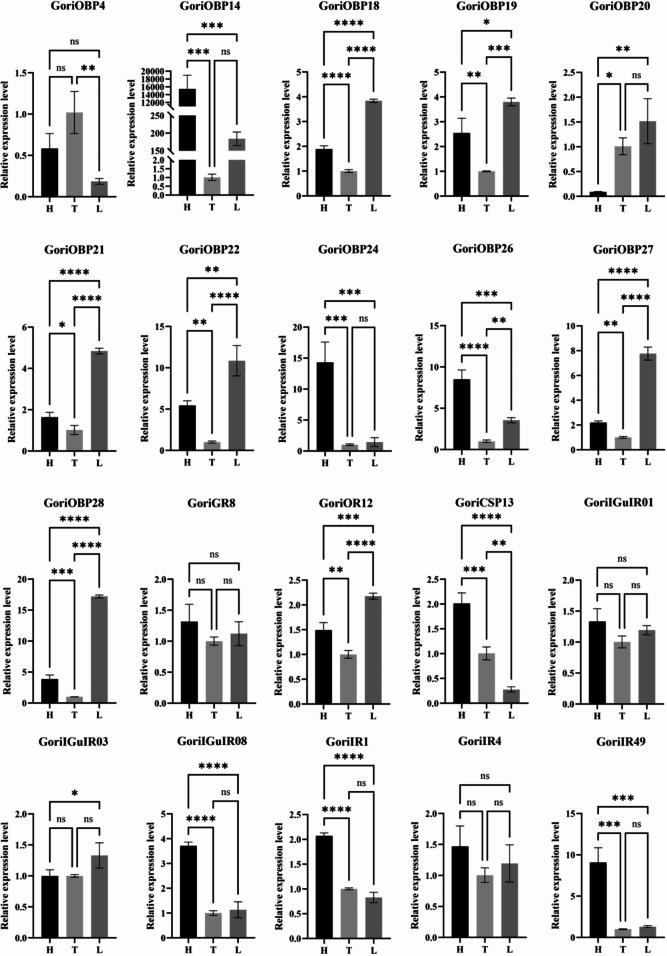

To validate our transcriptome findings, we performed qPCR on 20 CS genes, with results presented as relative expression levels across the head (H), thorax (T), and leg (L) tissues in (Fig. 8). The qPCR result is consistent with transcriptome data, GoriOBP4, GoriOBP14, GoriOBP18, and GoriOBP28 showed significant differential expression across body parts. For instance, GoriOBP28 demonstrated high expression in the leg (p < 0.0001), validating transcriptome data that suggested its role in leg-based chemosensation. Additionally, GoriIR4 and GoriIR1 were highly expressed in the thorax and head, respectively, aligning with FPKM-based findings. Statistical analysis revealed significant differences in gene expression among body regions for most genes (p-values ranging from p < 0.05 to p < 0.0001), confirming the spatial expression patterns observed in the transcriptome. Genes like GoriGR8 and GoriGluIR01 exhibited minimal expression variation, supporting their broadly conserved roles across body parts. Together, qPCR results validate the spatial expression profile from the transcriptome analysis, confirming that key CS genes exhibit distinct tissue-specific expression patterns that align with their proposed sensory functions in different body parts of G. orientalis.

Fig. 8.

qPCR validation of selected chemosensory genes across the head, thorax, and legs of Gryllotalpa orientalis. Relative expression levels were normalized to the ß-actin gene using the ΔΔCt method. The relative expression level of CS genes in G. orientalis Thorax is set at one

Discussion

Genome assembly & annotation

This is the first study to assemble the draft genome of G. orientalis and investigate the molecular intricacies of its subterranean lifestyle through its chemosensory gene repertoire. We obtained a 2.94 GB draft genome using a hybrid methodology merging Illumina and Nanopore sequencing technologies. The assembly consists of 10,497 scaffolds and uncovered 19,155 genes, with repetitive sequences comprising 52.79% of the genome. The large proportion of repetitive sequences in the G. orientalis genome might indicate adaptations to a subterranean lifestyle, as repetitive DNA often plays a role in genome plasticity and adaptability. These repetitive sequences may influence the regulation of chemosensory genes critical for detecting chemical cues in low-light environments. Despite the value of this resource, the scaffold-level assembly limits the annotation accuracy, highlighting the need for chromosome-level assemblies and manual curation. This reference genome offers a foundation for understanding evolutionary and ecological adaptations in G. orientalis and related subterranean species.

Comparative chemosensory gene analysis

Our study identified 158 chemosensory genes spanning six families: olfactory receptors (ORs), odorant-binding proteins (OBPs), ionotropic receptors (IRs), gustatory receptors (GRs), chemosensory proteins (CSPs), and sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs). This differential gene distribution may be attributed to the prevailing focus of previous studies on tissue-specific gene distributions derived primarily from transcriptomic analyses in other orthopterans, such as Ceracris kiangsu [29] and Tachycines meditationis [67], O. infernalis [68], O. asiaticus [28], and S. gregaria [69]. This study uniquely integrates both genomic and transcriptomic approaches, offering a more holistic understanding of the genetic landscape of this intriguing species. Comparative analysis with related species G. bimaculatus [66] and L. migratoria [26](Table:1) revealed distinct trades of the chemosensory repertoire in G. orientalis. Key findings include a reduction in the number of genes in the odorant receptor (OR) and gustatory receptor (GR) families, alongside an expansion in the ionotropic receptor (IR) and chemosensory protein (CSP) families, suggesting adaptations for underground life.

Chemosensory gene profiling of conserved gene families

The olfactory receptor (OR) gene repertoire in G.orientalis comprises 30 genes, with a predominant association in Clade I, fewer representatives in Clade II, and a notable expansion in the Orc clade. While Clade III OR is completely absent (Fig. 2), suggesting a lineage-specific loss likely tied to its subterranean lifestyle. This absence may reflect reduced reliance on environmental cues associated with Clade III ORs, with adaptations favoring olfactory mechanisms crucial for detecting subterranean food sources and pheromones. In contrast, the gustatory receptor (GR) repertoire is reduced to ten genes (Fig. 5), with the absence of GRs for CO2 and fructose detection, indicating dietary specialization on root-based feeding. The lack of Clade III ORs and reduced GRs suggests G. orientalis relies on alternative sensory mechanisms or enhancements in existing pathways to navigate its niche. Similar adaptations are seen in species like Apis mellifera, which compensate for receptor loss through alternative sensory strategies [70]. These findings highlight the evolutionary adjustments in sensory systems to ecological challenges.

Chemosensory gene profiling of expanded gene families

The genome of G. orientalis exhibits significant expansions in OBPs, IRs, and CSPs, indicating advanced chemical sensing capabilities. Identifying 28 OBP genes, categorized into classical and plus-C subfamilies, suggests distinct evolutionary trajectories shaped by environmental pressures [71]. The notable absence of minus-C, plus-C, and atypical OBPs implies a selective refinement of OBPs that enhance odor sensitivity, which is crucial for interactions with their subterranean habitat [72]. The prominence of IRs, particularly within the antennal subfamily (64 genes), further emphasizes the sophisticated chemosensory capabilities of G. orientalis. The discovery of a unique clade of six IR genes, designated “G. orientalis basal IRs” (Fig. 4), highlights the species-specific adaptations that warrant further investigation. The observed increase in IRs parallels findings in other subterranean insects, such as certain beetles, suggesting that chemosensory gene evolution is critical to environmental adaptation [73]. The 25 CSP genes identified, all exhibiting a conserved four-cysteine profile, underscore species-specific expansions that enhance chemical signal detection in subterranean environments, which is imperative for navigation and communication in burrowing insects [12, 16, 19].

Spatial expression patterns of chemosensory genes and qPCR validation

The transcriptomic analysis of 71 chemosensory genes across various body regions—head, thorax, and legs—reveals intricate spatial expression patterns that underscore the significance of distinct sensory adaptations across body regions, enhancing its subterranean foraging and navigation. Notably, olfactory receptors (ORs), particularly GoriOR10, GoriOR22, GoriOR29, and GoriOR30, demonstrated heightened expression in the head, aligning with their roles in detecting volatile cues. In contrast, OBPs such as GoriOBP18, GoriOBP19, GoriOBP22, GoriOBP26, GoriOBP27, and GoriOBP28 exhibited notable expression in the legs, suggesting their involvement in detecting environmental cues, facilitating soil-based contact chemoreception, an adaptation for detecting chemical signals during burrowing. Gustatory receptors (GRs), including GoriGR3, GoriGR4, GoriGR5, GoriGR7, and GoriGR8, were prominently expressed are consistently expressed across the head, thorax, and legs, indicating a cross-regional sensory role that may improve environmental responsiveness. qPCR validation supported these spatial patterns, with minor discrepancies attributed to methodological differences. These findings highlight the molecular underpinnings of sensory adaptations in G. orientalis, offering insights into its specialized foraging and navigation strategies. Future research focusing on detailed anatomical structures (e.g., antennae, brain) could further elucidate gene-function relationships.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. Mention of any trade names or commercial products in this article is solely to provide specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by any other authority.

Abbreviations

- CS

Chemosensory Genes

- OBP

Odorant-binding protein

- OR

Odorant Receptors

- IR

Ionotropic receptor

- GR

Gustatory receptor

- CSP

Chemosensory protein

Author contributions

A.C. conceived the study, planned experiments, conducted the analysis, and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. D.L.G., X.Y.D, T.J. Y.L. C.M.Y, M.S.K, and W.H. Z edited the manuscript and provided technical support for genomic analysis, transcriptomic analysis, qPCR validation, and figure creation. S-Q.X provided supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 31872273, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant numbers GK201903063 and GK202105003.

Data availability

All sequence data were deposited in GenBank under the Project Accession Number PRJNA1202218, with a BioSample Accession Number SAMN45954316.

Declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

De-Long Guan, Email: 2023660006@hcnu.edu.cn.

Sheng-Quan Xu, Email: xushengquan@snnu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Cigliano MM, Braun H, Eades DC, Otte D. Orthoptera Species File. Orthoptera Species File. Version 5.0/5.0. 2024. https://orthoptera.speciesfile.org/. Accessed 28 May 2024.

- 2.Sun K, Guan DL, Huang HT, Xu SQ. Genome Survey sequencing of the Mole Cricket Gryllotalpa Orientalis. Genes (Basel). 2023;14:255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halimullah PW, Mehmood, Xu S, Ilahi I, Ahmed S. Study on the oriental mole cricket, Gryllotalpa orientalis (orthoptera: gryllotalpidae: gryllotalpinae). Int J Adv Res (Indore). 2017;5:592–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graaf J, Schoeman A, Brandenburg R. Seasonal development of Gryllotalpa africana (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae) on turfgrass in South Africa. Fla Entomol. 2004;87:130–5.

- 5.Endo C. Seasonal wing dimorphism and life cycle of the mole cricket Gryllotalpa Orientalis (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae). Eur J Entomol. 2006;103:743–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker E, Broom YS. Natural history Museum Sound Archive I: Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae Leach, 1815, including 3D scans of burrow casts of Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa (Linnaeus, 1758) and Gryllotalpa Vineae Bennet- Clark, 1970. Biodivers Data J. 2015;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Zhang Y, Cao J, Wang Q, Wang P, Zhu Y, Zhang J. Motion characteristics of the appendages of Mole crickets during burrowing. J Bionic Eng. 2019;16:319–27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Huang H, Liu X, Ren L. Kinematics of terrestrial locomotion in mole cricket Gryllotalpa Orientalis. J Bionic Eng. 2011;8:151–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.MASAKI S. Geographical variation of life cycle in crickets (Ensifera: Grylloidea). http://www.eje.cz/artkey/eje-199603-0001_Geographical_variation_of_life_cycle_in_crickets_Ensifera_Grylloidea.php. 2013;93:281–302.

- 10.Endo C. An analysis of the horizontal burrow morphology of the oriental mole cricket (Gryllotalpa Orientalis) and the distribution pattern of surface vegetation. Can J Zool. 2008;86:1299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cucini C, Boschi S, Funari R, Cardaioli E, Iannotti N, Marturano G, et al. De novo assembly and annotation of Popillia japonica’s genome with initial clues to its potential as an invasive pest. BMC Genomics. 2024;25:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eyun S, Il, Soh HY, Posavi M, Munro JB, Hughes DST, Murali SC, et al. Evolutionary history of Chemosensory-related gene families across the Arthropoda. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:1838–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell RF, Schneider TM, Schwartz AM, Andersson MN, McKenna DD. The diversity and evolution of odorant receptors in beetles (Coleoptera). Insect Mol Biol. 2020;29:77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozaki M, Wada-Katsumata A, Fujikawa K, Iwasaki M, Yokohari F, Satoji Y, et al. Ant nestmate and non-nestmate discrimination by a chemosensory sensillum. Science. 2005;309:311–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johny J, Diallo S, Lukšan O, Shewale M, Kalinová B, Hanus R, et al. Conserved orthology in termite chemosensory gene families. Front Ecol Evol. 2023;10:1065947. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson HM. Molecular evolution of the Major Arthropod Chemoreceptor Gene Families. Annu Rev Entomol. 2019;64:227–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozaki K, Utoguchi A, Yamada A, Yoshikawa H. Identification and genomic structure of chemosensory proteins (CSP) and odorant binding proteins (OBP) genes expressed in foreleg tarsi of the swallowtail butterfly Papilio xuthus. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38:969–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sokolinskaya EL, Kolesov DV, Lukyanov KA, Bogdanov AM. Molecular principles of Insect Chemoreception. Acta Naturae. 2020;12:81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen R, Yan J, Wickham JD, Gao Y. Genomic identification and evolutionary analysis of chemosensory receptor gene families in two Phthorimaea pest species: insights into chemical ecology and host adaptation. BMC Genomics. 2024;25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Abuin L, Bargeton B, Ulbrich MH, Isacoff EY, Kellenberger S, Benton R. Functional Architecture of olfactory ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron. 2011;69:44–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ni L. The structure and function of ionotropic receptors in Drosophila. Front Mol Neurosci. 2021;13:638839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knecht ZA, Silbering AF, Cruz J, Yang L, Croset V, Benton R et al. Ionotropic receptor-dependent moist and dry cells control hygrosensation in Drosophila. Elife. 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.He H, Crabbe MJC, Ren Z. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the chemosensory relative protein genes in Rhus gall aphid Schlechtendalia Chinensis. BMC Genomics. 2023;24:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Zhao M, Aikeremu F, Huang H, You M, Zhao Q. Involvement of three chemosensory proteins in perception of host plant volatiles in the tea green leafhopper, Empoasca Onukii. Front Physiol. 2022;13:1068543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Yang P, Chen D, Jiang F, Li Y, Wang X, et al. Identification and functional analysis of olfactory receptor family reveal unusual characteristics of the olfactory system in the migratory Locust. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:4429–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo W, Ren D, Zhao L, Jiang F, Song J, Wang X, et al. Identification of odorant-binding proteins (OBPs) and functional analysis of phase-related OBPs in the migratory Locust. Front Physiol. 2018;9(JUL):387746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Fang X, Yang P, Jiang X, Jiang F, Zhao D et al. The Locust genome provides insight into swarm formation and long-distance flight. Nat Commun. 2014;5:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Pang B, Zhang L. Novel odorant-binding proteins and their expression patterns in grasshopper, Oedaleus Asiaticus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;460:274–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li R, Jiang GF, Shu XH, Wang YQ, Li MJ. Identification and expression Profile Analysis of Chemosensory genes from the Antennal Transcriptome of Bamboo Locust (Ceracris Kiangsu). Front Physiol. 2020;11:549157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pregitzer P, Jiang X, Grosse-Wilde E, Breer H, Krieger J, Fleischer J. In search for pheromone receptors: certain members of the odorant receptor family in the Desert Locust Schistocerca Gregaria (Orthoptera: Acrididae) are co-expressed with SNMP1. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13:911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Usman T, Yu Y, Liu C, Fan Z, Wang Y. Comparison of methods for high quantity and quality genomic DNA extraction from raw cow milk. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:3319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babraham. FastQC A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data.Bioinformatics https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/. Accessed 21 Nov 2024.

- 33.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Coster W, D’Hert S, Schultz DT, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. NanoPack: visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:2666–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Liu B, Zhang Y, Jiang F, Ren Y, Yin L et al. Estimation of genome size using k-mer frequencies from corrected long reads.ARXIV.> q-bio.GN.2020;26,03.

- 36.Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27:722–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S, et al. Pilon: an Integrated Tool for Comprehensive Microbial Variant Detection and Genome Assembly Improvement. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seppey, Manni M, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: Assessing Genome Assembly and Annotation Completeness. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1962:227–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kriventseva EV, Kuznetsov D, Tegenfeldt F, Manni M, Dias R, Simão FA, et al. OrthoDB v10: sampling the diversity of animal, plant, fungal, protist, bacterial and viral genomes for evolutionary and functional annotations of orthologs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D807–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen FC, Vallender EJ, Wang H, Tzeng CS, Li WH. Genomic divergence between Human and Chimpanzee estimated from large-scale alignments of genomic sequences. J Hered. 2001;92:481–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinf. 2009;Chap. 4 SUPPL. 25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature Protocols 2013 8:8. 2013;8:1494–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Hung JH, Weng Z. Sequence alignment and homology search with BLAST and ClustalW. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2016;1016–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burge C, Karlin S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:78–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 2004;14:988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cantarel BL, Korf I, Robb SMC, Parra G, Ross E, Moore B, et al. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 2008;18:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haas BJ, Salzberg SL, Zhu W, Pertea M, Allen JE, Orvis J, et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li W, Kondratowicz B, McWilliam H, Nauche S, Lopez R. The annotation-enriched non-redundant patent sequence databases. Database (Oxford). 2013;2013:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Williams TD, Nagaraj SH, Nueda MJ, et al. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3420–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35 suppl2:W182–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petersen TN, Brunak S, Von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krogh A, Larsson B, Von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katoh K, Asimenos G, Toh H. Multiple alignment of DNA sequences with MAFFT. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;537:39–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:268–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W293–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, Van Baren MJ, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:907–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:290–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, et al. TBtools: an integrative Toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big Biological Data. Mol Plant. 2020;13:1194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cui Y, Kang C, Wu Z, Lin J. Identification and expression analyses of olfactory gene families in the rice grasshopper, oxya chinensis, from antennal transcriptomes. Front Physiol. 2019;10:SEP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zafar Z, Fatima S, Bhatti MF, Shah FA, Saud Z, Butt TM. Odorant binding proteins (OBPs) and odorant receptors (ORs) of Anopheles Stephensi: identification and comparative insights. PLoS ONE. 2022;17 3 March. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Torres-Huerta B, Segura-León OL, Aragón-Magadan MA, González-Hernández H. Identification and motif analyses of candidate nonreceptor olfactory genes of Dendroctonus adjunctus Blandford (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) from the head transcriptome. Sci Rep. 2020;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Zeng V, Ewen-Campen B, Horch HW, Roth S, Mito T, Extavour CG. Developmental Gene Discovery in a Hemimetabolous insect: De Novo Assembly and Annotation of a transcriptome for the Cricket Gryllus Bimaculatus. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lu JH, Guan DL, Xu SQ, Huang H. De Novo Assembly and characterization of the transcriptome of an omnivorous Camel Cricket (Tachycines Meditationis). Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y, Tan Y, Zhou XR, Pang BP. A whole-body transcriptome analysis and expression profiling of odorant binding protein genes in Oedaleus Infernalis. Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics Proteom. 2018;28:134–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jiang X, Ryl M, Krieger J, Breer H, Pregitzer P. Odorant binding proteins of the desert Locust Schistocerca Gregaria (Orthoptera, Acrididae): topographic expression patterns in the antennae. Front Physiol. 2018;9 APR:369053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Robertson HM, Wanner KW. The chemoreceptor superfamily in the honey bee, Apis mellifera: expansion of the odorant, but not gustatory, receptor family. Genome Res. 2006;16:1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou JJ, He XL, Pickett JA, Field LM. Identification of odorant-binding proteins of the yellow fever mosquito aedes aegypti: genome annotation and comparative analyses. Insect Mol Biol. 2008;17:147–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hekmat-Scafe DS, Scafe CR, McKinney AJ, Tanouye MA. Genome-wide analysis of the odorant-binding protein Gene Family in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 2002;12:1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Balart-García P, Bradford TM, Beasley-Hall PG, Polak S, Cooper SJB, Fernández R. Highly dynamic evolution of the chemosensory system driven by gene gain and loss across subterranean beetles. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2024;194:108027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All sequence data were deposited in GenBank under the Project Accession Number PRJNA1202218, with a BioSample Accession Number SAMN45954316.