Abstract

Hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (Hrs) is well known to terminate cell signaling by sorting activated receptors to the MVB/lysosomal pathway. Here we identify a distinct role of Hrs in promoting rapid recycling of endocytosed signaling receptors to the plasma membrane. This function of Hrs is specific for receptors that recycle in a sequence-directed manner, in contrast to default recycling by bulk membrane flow, and is distinguishable in several ways from previously identified membrane-trafficking functions of Hrs/Vps27p. In particular, Hrs function in sequence-directed recycling does not require other mammalian Class E gene products involved in MVB/lysosomal sorting, nor is receptor ubiquitination required. Mutational studies suggest that the VHS domain of Hrs plays an important role in sequence-directed recycling. Disrupting Hrs-dependent recycling prevented functional resensitization of the β2-adrenergic receptor, converting the temporal profile of cell signaling by this prototypic G protein-coupled receptor from sustained to transient. These studies identify a novel function of Hrs in a cargo-specific recycling mechanism, which is critical to controlling functional activity of the largest known family of signaling receptors.

Keywords: GPCR, Hrs, recycling, resensitization, ubiquitin

Introduction

Endocytic membrane trafficking is well known to play multiple roles in regulating receptor-mediated signal transduction, but specific mechanistic links between signaling and endocytosis remain poorly understood (Raiborg et al, 2001b; Perry and Lefkowitz, 2002; Sorkin and Von Zastrow, 2002; Marchese et al, 2003a). Perhaps the best established connection between signaling and membrane traffic is in the process of receptor ‘downregulation' by endocytic sorting of receptors to the MVB/lysosome pathway (Wiley and Burke, 2001; Katzmann et al, 2002). This endocytic pathway is well described for various G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in yeast (Hicke, 1999; Chen and Davis, 2002), mammals (Pierce et al, 2002; von Zastrow, 2003), and for protein tyrosine kinases such as the EGF receptor (Wiley and Burke, 2001; Dikic, 2003). MVB/lysosome trafficking attenuates cellular responsiveness following prolonged or repeated exposure to activating ligands and contributes to the transient nature of many receptor-mediated signals (Pierce et al, 2002; Sorkin and Von Zastrow, 2002).

Studies of certain GPCRs, such as the mammalian β2-adrenergic receptor (β2ADR), have identified a very different, and essentially opposite, relationship between endocytosis and signaling. The β2ADR undergoes ligand-induced endocytosis, but then is rapidly and efficiently recycled back to the plasma membrane (Kurz and Perkins, 1992; von Zastrow and Kobilka, 1992), mediating sustained (rather than transient) responses to extracellular ligands and promoting rapid recovery (rather than attenuation) of cellular responsiveness following prolonged or repeated ligand exposure (Lefkowitz et al, 1998).

Considerable progress has been made in understanding the mechanism of receptor downregulation by MVB/lysosome sorting. Endocytic sorting to the vacuole/lysosome is mediated by receptor ubiquitination followed by interaction with a conserved set of endosome-associating proteins encoded by the Class E VPS genes, which recognize ubiquitinated receptors and promote their translocation from the limiting membrane to intralumenal vesicles of MVBs (Katzmann et al, 2002; Gruenberg and Stenmark, 2004). At least two of these proteins, Hrs/Vps27p and Tsg101/Vps23p, contain ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs) that are essential for lysosomal/vacuolar sorting of ubiquitinated membrane cargo (Babst et al, 2000; Bilodeau et al, 2002; Raiborg and Stenmark, 2002; Marchese et al, 2003b).

In contrast to this specific mechanism of vacuolar/lysosomal sorting, efficient plasma membrane recycling can occur simply by bulk membrane flow, a ‘default' pathway which does not require any specific sorting signals or sorting protein interactions (Mayor et al, 1993). Indeed, a number of constitutively endocytosed membrane proteins, such as transferrin receptors (TfnRs), can recycle efficiently in the absence of cytoplasmic sorting sequence(s) (Marsh et al, 1995). This simple model of recycling is not sufficient to explain the endocytic trafficking of certain GPCRs, like the β2ADR, whose recycling is critically dependent on protein interaction(s) with a sequence present in the carboxyl-terminal cytoplasmic domain (Cao et al, 1999; Cong et al, 2001; Gage et al, 2001). While endocytosed β2ADRs can also traffic to lysosomes (Gagnon et al, 1998), recycling is the predominant pathway under many physiological conditions and is essential for producing sustained cellular signaling responses (Lefkowitz et al, 1998). Similarly the μ opioid receptor (μOR), another GPCR for which recycling is critical for functional resensitization of signaling (Koch et al, 1998, 2001), also requires a distinct cytoplasmic targeting sequence to recycle efficiently (Tanowitz and von Zastrow, 2003). The β2ADR- and μOR-derived cytoplasmic sequences, while functionally interchangeable, do not share significant structural homology and are thought to bind distinct cytoplasmic proteins (Tanowitz and von Zastrow, 2003). Thus, an emerging concept is that there may exist an array of cis-acting endocytic ‘recycling sequences' in various signaling receptors that, via binding to distinct cytoplasmic linker proteins, mediate specific sorting of endocytosed receptors into a conserved recycling pathway. A key prediction of this hypothesis is that these receptors engage a ‘core' endocytic sorting mechanism. However, to date, no shared component mediating sequence-directed recycling of these distinct signaling receptors has been identified.

In the present study, we show that Hrs plays an essential function in sequence-directed recycling of both the β2ADR and μOR, but not in the recycling of membrane cargo that do not require a cytoplasmic targeting sequence to traverse this pathway. This additional function of Hrs is distinct from its previously defined role in MVB/lysosome sorting since it is independent of Tsg101 and Vps4, and also does not require receptor ubiquitination. Moreover, we confirm that Hrs is required for functional resensitization of, and sustained cellular responsiveness to, the β2ADR. Thus, we propose a new function of Hrs in mediating sequence-directed recycling, which is critical for determining the temporal response profile of the largest known family of signaling receptors.

Results

Evidence for a role of Hrs in plasma membrane recycling

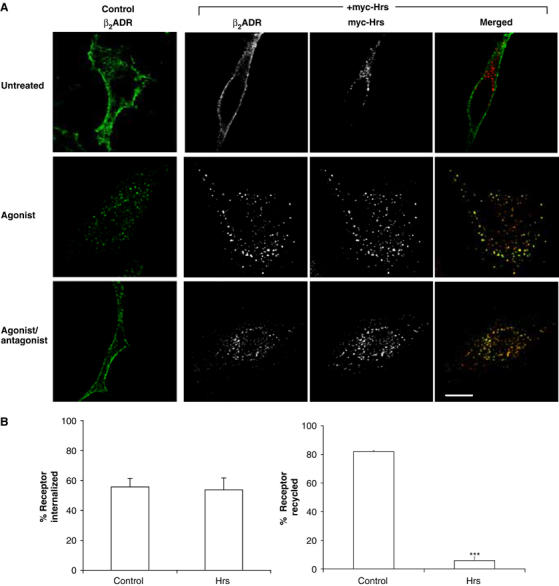

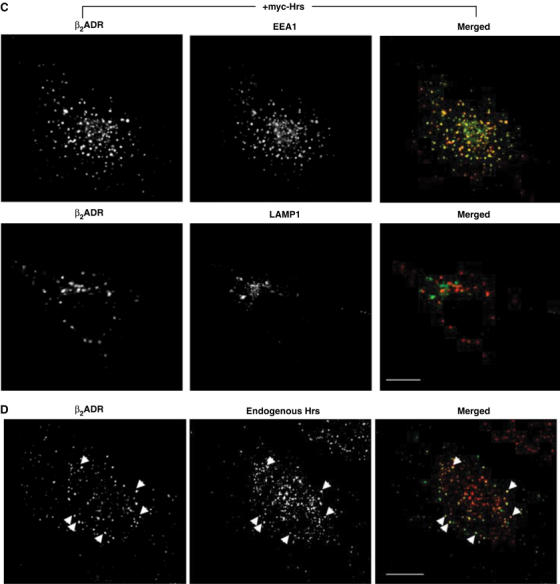

A Flag-tagged β2ADR, both with and without co-expression of myc-Hrs, was localized in the plasma membrane of transfected HeLa cells in the absence of receptor ligand (Figure 1A). Following receptor activation with the agonist isoproterenol, the β2ADR internalized rapidly to endocytic vesicles and, in cells overexpressing myc-Hrs, these endosomes colocalized extensively with myc-Hrs (Figure 1A). In cells expressing normal levels of (endogenous) Hrs, antibody-labeled internalized receptors exited the endosomal pool and recycled to the plasma membrane within 60 min after agonist removal from the culture medium (Figure 1A). However, in cells overexpressing myc-Hrs, internalized β2ADR failed to recycle and remained in myc-Hrs-positive endosomes (Figure 1A). This effect was assayed using fluorescence flow cytometry to accurately quantitate changes in surface receptor fluorescence in individual intact cells, which are then averaged over a large population of cells (10 000), occurring as a result of internalization and recycling. We have previously used this method to effectively measure trafficking of GPCRs (Gage et al, 2001; Tanowitz and von Zastrow, 2003). This analysis confirmed that overexpression of myc-Hrs did not detectably affect agonist-induced internalization of the β2ADR (Figure 1B, left graph), but profoundly inhibited its recycling (Figure 1B, right graph). In the same experiments, Hrs overexpression produced no detectable effect on either endocytosis or recycling of TfnRs (data not shown), as previously reported (Raiborg et al, 2001a, 2002). Internal β2ADRs that were unable to recycle under conditions of myc-Hrs overexpression remained in early endosomes (marked by EEA-1) for ⩾60 min following agonist washout, and were not observed to traffic to late endosome/lysosome compartments marked by lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) during this time period (Figure 1C). This localization is consistent with that of the β2ADR in agonist-treated cells not overexpressing Hrs, where there is colocalization of internalized receptors both with EEA-1 (Figure 5B) and endogenous Hrs (Figure 1D). These results suggest that overexpression of Hrs does detectably perturb agonist-induced endocytosis of the β2ADR, but that this manipulation inhibits recycling of β2ADRs by ‘trapping' internalized receptors in early endosomes.

Figure 1ab.

Hrs overexpression inhibits recycling of the β2ADR. (A) HeLa cells expressing Flag-β2ADR and either pcDNA3 (control) or myc-Hrs were fed with rabbit anti-Flag antibody to label the surface receptor prior to treatment with agonist isoproterenol (30 min, 10 μM). Cells were washed and treated with antagonist alprenolol (1 h, 10 μM) to allow for recycling and prevent further receptor internalization. Cells were fixed and stained for confocal microscopy with anti-myc antibodies as described in Materials and methods. Merged and unmerged images are shown for cells co-expressing Flag-β2ADR (green) and myc-Hrs (red). Yellow indicates colocalization. White bar=10 μm. (B) Cell surface receptor was measured by flow cytometry in HeLa cells co-expressing Flag-β2ADR and GFP together with pcDNA3 (control) or myc-Hrs. Cells were treated as for (A). Percentage of internalization refers to the fractional reduction of surface receptor in response to 30-min agonist exposure. Percentage of receptor recycled refers to the fractional recovery of surface receptor following agonist washout for 1 h. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. from three independent experiments. ***P<0.001.

Figure 1cd.

(C) HeLa cells expressing Flag-β2ADR and myc-Hrs were fed with mouse anti-Flag antibody to label the surface receptor prior to treatment with agonist isoproterenol (30 min, 10 μM). Cells were washed and treated with antagonist alprenolol (1 h, 10 μM) to allow for recycling and prevent further receptor internalization. Cells were fixed and stained for confocal microscopy with anti-EEA-1-FITC or anti-LAMP1 antibodies as described in Materials and methods. Only cells treated with antagonist, following agonist washout, are shown. Merged and unmerged images are shown for cells co-expressing Flag-β2ADR (red), EEA-1 (green) or LAMP1 (green). Yellow indicates colocalization. White bar=10 μm. (D) HeLa cells expressing Flag-β2ADR were fed with mouse anti-Flag antibody to label the surface receptor prior to treatment with agonist isoproterenol (30 min, 10 μM). Cells were fixed and stained for confocal microscopy with rabbit anti-Hrs antibody. Merged and unmerged images are shown for cells co-expressing Flag-β2ADR (green) and Hrs (red). Yellow indicates colocalization. Arrows indicate examples of colocalized vesicles. White bar=10 μm.

Figure 5b.

(B) HeLa cells expressing Flag-β2ADR and either control (nonsilencing) siRNA or Hrs siRNA were fed with anti-Flag antibody to label surface receptor prior to treatment with agonist isoproterenol (30 min, 10 μM). Cells were washed and treated with antagonist alprenolol (1 h, 10 μM) to allow for recycling and prevent further receptor internalization. Cells were fixed and stained for EEA-1 as described in Materials and methods. Merged and unmerged images are shown. Receptor is in red, EEA-1 is in green, and yellow indicates colocalization. White bar=10 μm.

Hrs regulates sequence-directed, but not default, recycling of GPCRs

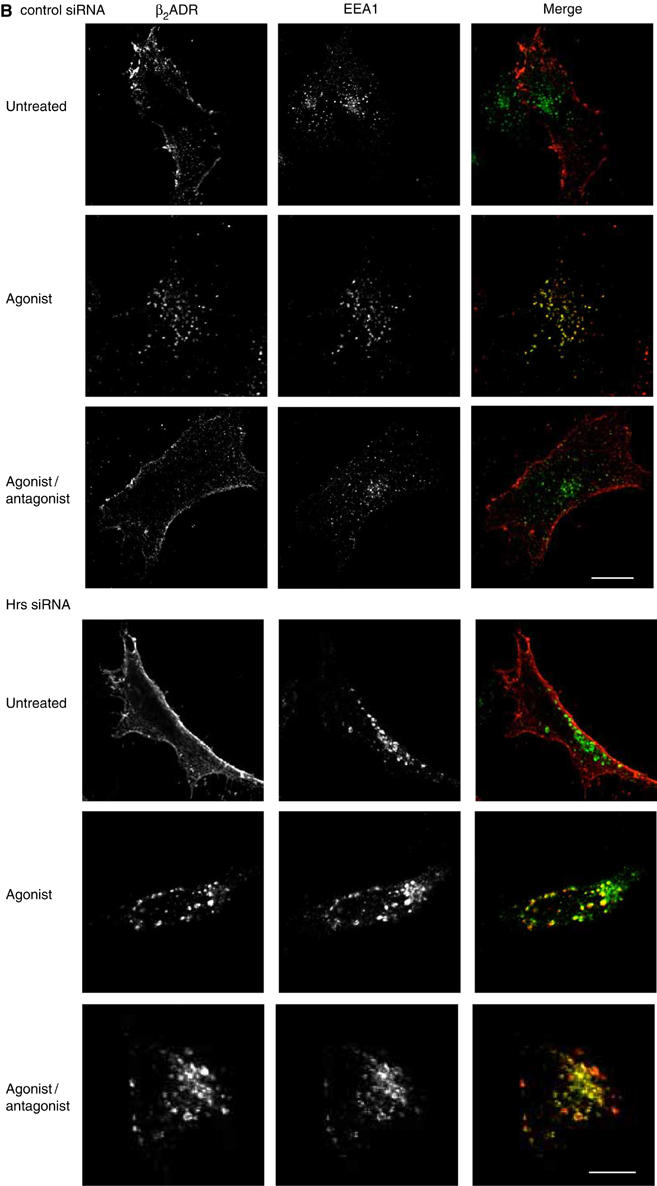

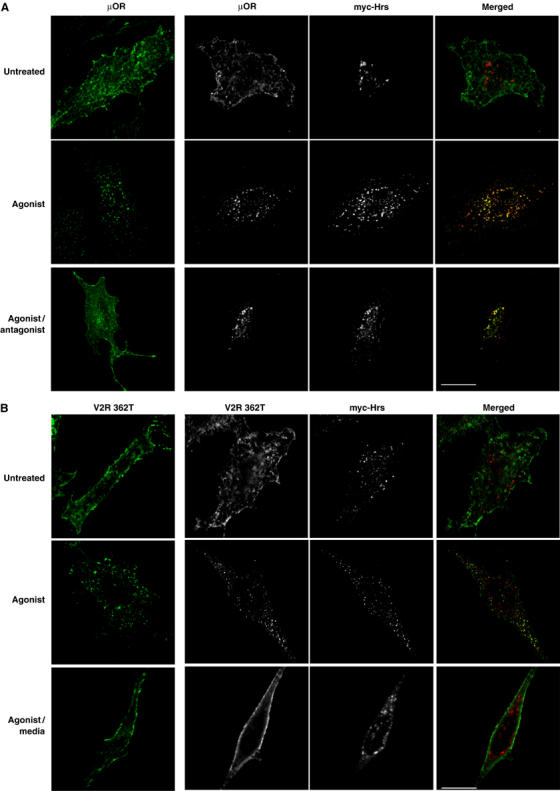

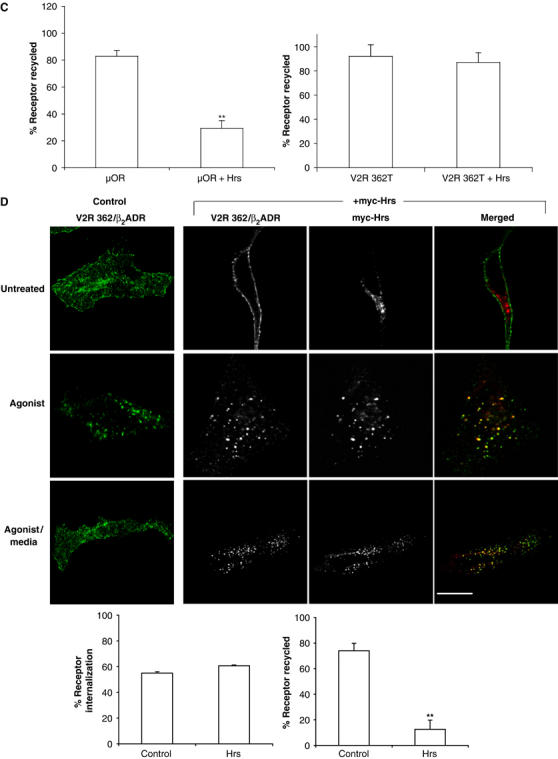

The ability of Hrs overexpression to inhibit recycling of β2ADRs, but not TfnRs (which colocalize in the same endosomes (Cao et al, 1998)), suggests that Hrs might function selectively in endocytic trafficking of membrane cargo that undergoes sequence-directed, rather than default, recycling. Alternatively, the exquisite sensitivity of β2ADR recycling to Hrs expression levels could be an indirect reflection of some other difference between heptahelical GPCRs and single transmembrane proteins (such as the TfnR) that are typically used for studies of endocytic sorting. To distinguish between these possibilities, we examined the effect of Hrs overexpression on the trafficking of two other GPCRs that differ in whether they undergo sequence-directed or default recycling after ligand-induced endocytosis. Like the β2ADR, efficient recycling of the μOR requires a specific cytoplasmic targeting sequence (Tanowitz and von Zastrow, 2003). In contrast, a truncation mutant of the V2 vasopressin receptor (V2R 362T) is missing its cytoplasmic targeting sequence, yet can recycle rapidly after agonist-induced endocytosis, akin to the constitutively cycling TfnR (Innamorati et al, 1998, 2001). As observed with the β2ADR, overexpression of myc-Hrs strongly inhibited recycling of the μOR without detectably affecting its ligand-induced internalization (Figure 2A). In contrast, ‘default' recycling of V2R 362T was not detectably inhibited in cells overexpressing myc-Hrs (Figure 2B). The confocal data were confirmed by flow cytometry analysis of receptor recycling in large populations of transfected cells (Figure 2C). These results suggest that Hrs plays a specific role in recycling of receptors that require specific cytoplasmic targeting sequences for this process (β2ADR and μOR), but is not important for receptors that apparently recycle by ‘default' (TfnR and V2R 362T).

Figure 2ab.

Hrs-dependent recycling is cargo specific. (A, B) HeLa cells expressing Flag-μOR or Flag-V2R 362T with either pcDNA3 (control) or myc-Hrs were fed with anti-Flag antibody to label surface receptor prior to treatment with agonist etorphine for μOR and arginine vasopressin for V2R 362T (30 min, 10 μM). Cells were washed and treated with antagonist naloxone (1 h, 10 μM) for μOR to allow for recycling and prevent further receptor internalization. V2R 362T-expressing cells were incubated in media only following agonist washout.

Figure 2cd.

(C) Cell surface receptor was measured by flow cytometry in HeLa cells co-expressing Flag-μOR or Flag-V2R 362T, together with pcDNA3 (control) or myc-Hrs. Cells were treated as for (A). (D) HeLa cells expressing Flag-V2R 362/β2ADR with either pcDNA3 (control) or myc-Hrs were fed with anti-Flag antibody to label surface receptor prior to treatment with agonist arginine vasopressin (30 min, 10 μM). Cells were washed and incubated in media only for 1 h. Cell surface receptor was measured in HeLa cells co-expressing Flag-V2R 362/β2ADR together with pcDNA3 (control) or myc-Hrs. Cells were treated and measured as in (C). For all images, merged and unmerged images are shown for cells co-expressing receptor (green) and myc-Hrs (red). Yellow indicates colocalization. White bar=10 μm. For all flow cytometry experiments, a minimum of 10 000 cells were counted. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. from three independent experiments. **P<0.01.

To further test the specificity of Hrs function in the sequence-directed recycling mechanism, we examined whether fusion of a previously defined GPCR recycling sequence is sufficient to confer Hrs dependence on a receptor that recycles in an Hrs-independent manner. A distal portion of the β2ADR C-terminal tail (aa 369–413), which can re-route a heterologous receptor from lysosomal to a recycling pathway (Gage et al, 2001), was fused to the cytoplasmic tail of the default-recycling V2R 362T. The V2R 362/β2ADR chimera endocytosed rapidly after agonist activation, as expected, and a major fraction of internalized receptors recycled back to the plasma membrane within 60 min after agonist washout (Figure 2D). However, fusing the β2ADR-derived tail sequence conferred a profound Hrs sensitivity on V2R 362/β2ADR recycling (Figure 2D). Together, these results indicate that Hrs-sensitive recycling is a specific property of certain GPCRs, which is conferred by structural determinant(s) mediating sequence-directed sorting of receptors into the recycling pathway.

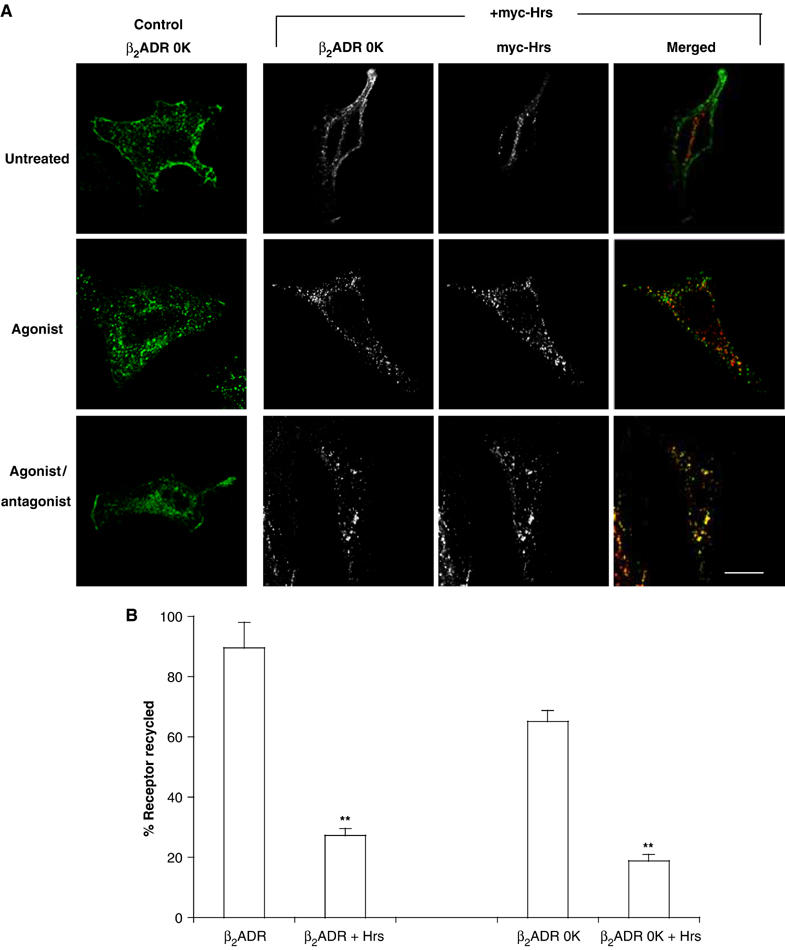

Hrs-sensitive recycling does not require receptor ubiquitination

Hrs is well known to bind ubiquitinated proteins and many of its sorting functions require cargo ubiquitination (Bilodeau et al, 2002; Katzmann et al, 2002; Raiborg and Stenmark, 2002; Marchese et al, 2003b; Gruenberg and Stenmark, 2004). Given the essential role of ubiquitination in mediating β2ADR downregulation by lysosomal trafficking (Shenoy et al, 2001), we were interested to determine if the inhibitory effect of Hrs overexpression on β2ADR recycling also requires receptor ubiquitination. To address this question, we utilized a β2ADR mutant that has all 16 lysines replaced with arginine (β2ADR 0K) (Parola et al, 1997). β2ADR 0K undergoes ligand-induced internalization similar to that of the wild-type (WT) β2ADR, but is defective in agonist-dependent ubiquitination and degradation (Shenoy et al, 2001). Flow cytometry confirmed agonist-induced endocytosis of β2ADR 0K and indicated that a major fraction of these receptors recycled within 60 min after agonist washout (Figure 3A and B). Importantly, recycling of the β2ADR 0K was strongly inhibited by overexpression of myc-Hrs, to a similar degree as that of the WT β2ADR (Figure 3A and B). These results suggest that the β2ADR does not require ubiquitination either for recycling or for selective inhibition of this recycling process by Hrs overexpression.

Figure 3.

Hrs-dependent recycling does not require receptor ubiquitination. (A) HeLa cells expressing Flag-β2ADR 0K with either pcDNA3 (control) or myc-Hrs were treated and stained for confocal microscopy as described in Figure 1A. White bar=10 μm. (B) Cell surface receptor was measured by flow cytometry in HeLa cells co-expressing either Flag-β2ADR or Flag-β2ADR 0 K and either pcDNA3 (control) or myc-Hrs. A minimum of 10 000 cells were counted. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. of four independent experiments. **P<0.01.

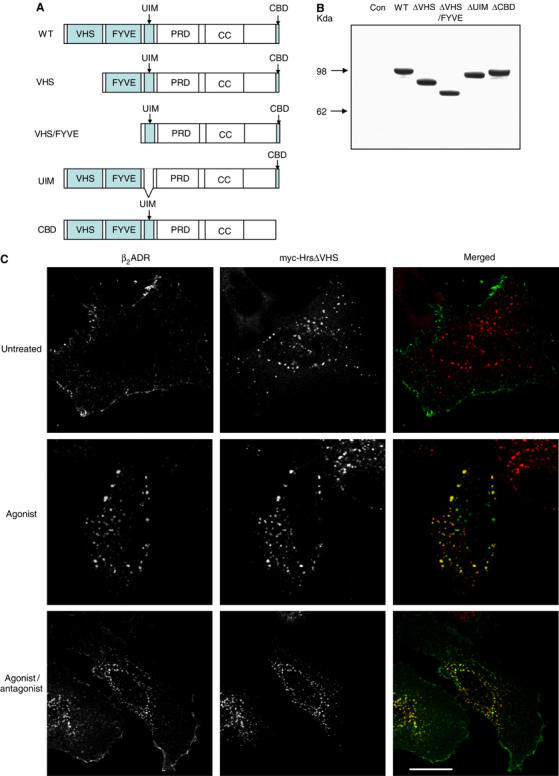

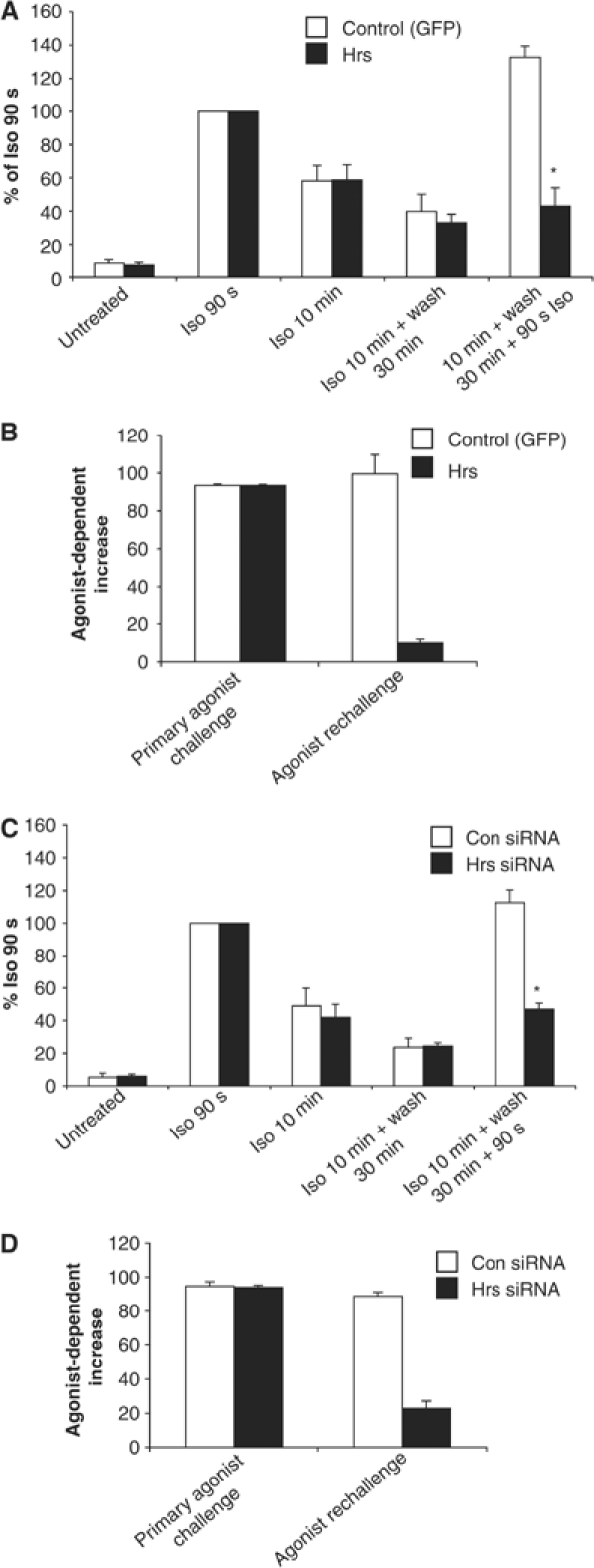

Deletion analysis suggests a specific role of the VHS domain of Hrs in the sequence-directed recycling mechanism

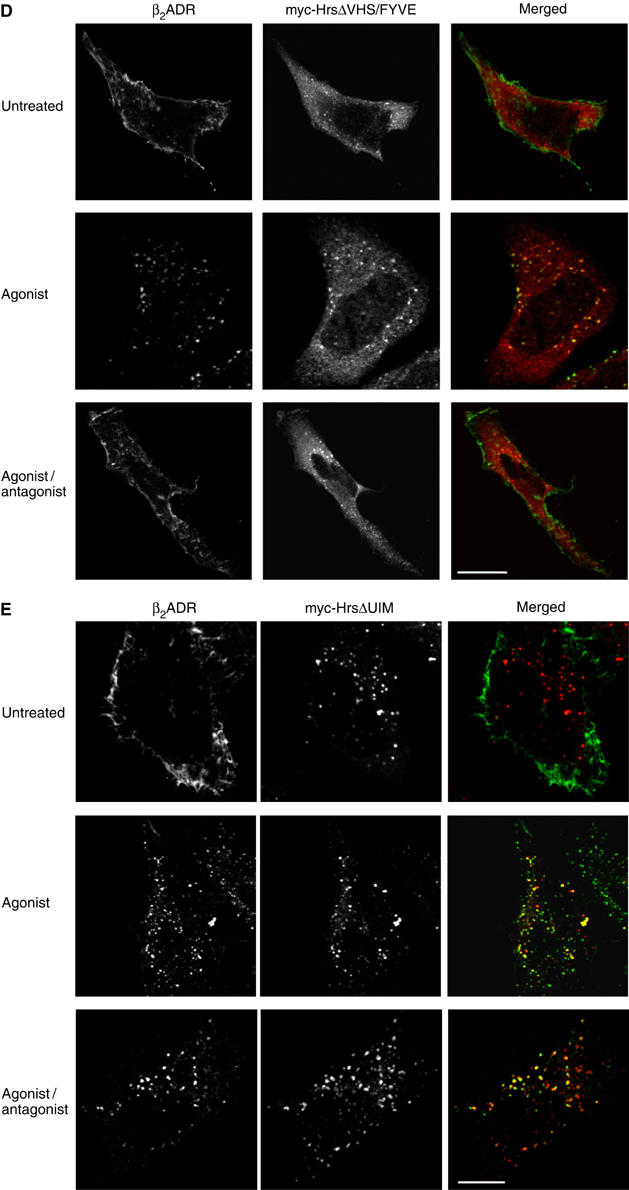

Hrs is a large multi-domain protein with multiple interaction partners that have been shown to be important for endosome membrane localization and/or ubiquitin-directed lysosomal sorting functions (Gruenberg and Stenmark, 2004). As β2ADR ubiquitination is not required either for sequence-directed recycling of receptors or for conferring Hrs sensitivity on this process, we hypothesized that a region of Hrs may be involved in the sequence-directed recycling mechanism that is not required for the lysosomal sorting function of Hrs. To investigate this hypothesis, we constructed a series of truncation and deletion mutants of myc-tagged Hrs (Figure 4A) and tested their ability to inhibit recycling of the β2ADR when overexpressed. All of the mutant Hrs constructs were expressed at similarly high levels as WT myc-Hrs (Figure 4B). Truncation of the N-terminal VHS domain produced a mutant Hrs protein (ΔVHS) that was defective in its ability to inhibit β2ADR recycling when overexpressed, as indicated by the reappearance of FLAG antibody-labeled β2ADR at the plasma membrane observed by fluorescence microscopy after agonist removal (Figure 4C, lower right panel). A more severe truncation, missing both VHS and FYVE domains (ΔVHS/FYVE), also failed to prevent β2ADR recycling (Figure 4D). In contrast, deletion of the ubiquitin-interacting motif (ΔUIM) and clathrin-binding domain (ΔCBD) produced mutant Hrs proteins capable of strongly inhibiting β2ADR recycling (Figure 5E).

Figure 4abc.

The VHS domain of Hrs is required for its effect on β2ADR recycling. (A) Schematic of the domain organization of full-length Hrs and the truncated mutants used as indicated. (B) Western blot to verify similar expression levels of all proteins with an anti-myc antibody in transfected HeLa lysates. (C–F) HeLa cells were transfected with Flag-β2ADR and myc-Hrs truncated mutants as indicated. Cells were treated and stained for receptor and myc-Hrs as for Figure 1A. White bar=10 μm.

Figure 4de.

(C–F) HeLa cells were transfected with Flag-β2ADR and myc-Hrs truncated mutants as indicated. Cells were treated and stained for receptor and myc-Hrs as for Figure 1A. White bar=10 μm.

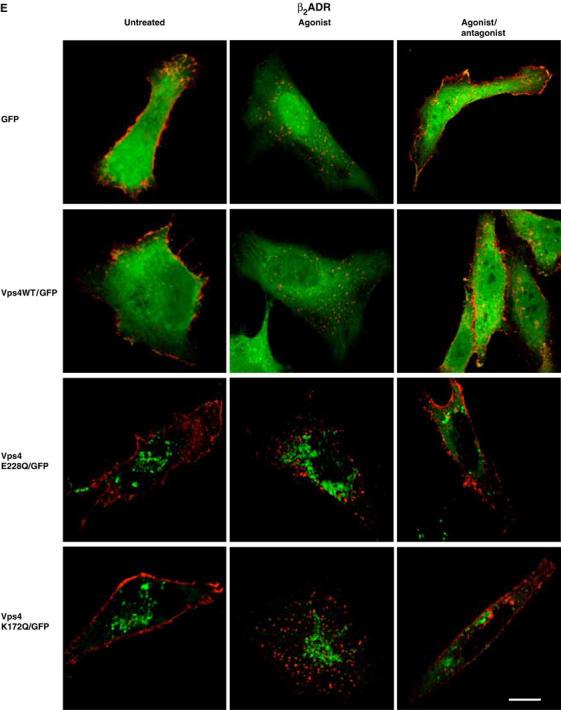

Figure 5e.

(E) Cells transfected with Flag-β2ADR and either GFP, WT Vps4/GFP, Vps4 E228Q/GFP or Vps4 K172Q/GFP were treated as in (B) and assessed by confocal microscopy. White bar=10 μm.

Flow-cytometric analysis confirmed that, while none of the mutant Hrs constructs affected agonist-induced internalization of the β2ADR (Figure 4G, upper graph), there were pronounced differences in the effects of WT and mutant versions of Hrs on recycling of the β2ADR after agonist removal (Figure 4G, lower graph). Overexpression of ΔUIM and ΔCBD mutant versions of Hrs strongly inhibited β2ADR recycling as WT Hrs. Notably, both N-terminal truncation mutants (ΔVHS and ΔVHS/FYVE) were confirmed to be markedly defective in their ability to inhibit β2ADR recycling. The failure of the ΔVHS/FYVE mutant Hrs to inhibit this process could reflect a secondary consequence of reduced association of this mutant on endosome membranes (note the increased cytoplasmic anti-myc staining in middle panels of Figure 4D), consistent with studies demonstrating an important role of the FYVE domain in endosome association of Hrs (Raiborg et al, 2001c). However, the effect of truncating the VHS domain cannot be explained on this basis, as the VHS domain is not required for endosome localization of Hrs (Raiborg et al, 2001c) and the ΔVHS mutant construct used in the present study was highly concentrated on endosomes (middle panels of Figure 4C). Furthermore, it has been shown that similar N-terminal deletions of Hrs, devoid of the VHS domain or VHS/FYVE, retain their ability to produce dominant-negative inhibition of EGF receptor trafficking when overexpressed in HeLa cells (Chin et al, 2001; Morino et al, 2004). Together, these results suggest that the VHS domain of Hrs may be specifically required for a distinct function of Hrs in the sequence-directed recycling mechanism.

Figure 4fg.

(C–F) HeLa cells were transfected with Flag-β2ADR and myc-Hrs truncated mutants as indicated. Cells were treated and stained for receptor and myc-Hrs as for Figure 1A. White bar=10 μm. (G) Quantification of β2ADR internalization and recycling by flow cytometry in the absence and presence of WT and mutant myc-Hrs constructs. Data shown are the mean±s.e.m. of five separate experiments.

Hrs is essential for recycling directed by distinct cytoplasmic targeting sequences

We hypothesized that the inhibitory effect of Hrs overexpression on the sequence-directed recycling mechanism might also indicate an essential role of Hrs in this process. An alternative possibility is that inhibited recycling produced by Hrs overexpression could reflect an indirect or secondary consequence of protein overexpression. To distinguish between these possibilities, we examined the effects of depleting cellular Hrs on sequence-directed recycling by using small interfering RNA (siRNA). A substantial reduction in cellular Hrs was achieved when HeLa cells were transfected with a previously described Hrs-specific siRNA (Bache et al, 2003) but not control (nonsilencing) siRNA, as indicated by Western blot of whole-cell lysates (Figure 5A). Specificity of the Hrs knockdown was also confirmed by blotting the same lysates for the protein GapDH (Figure 5A).

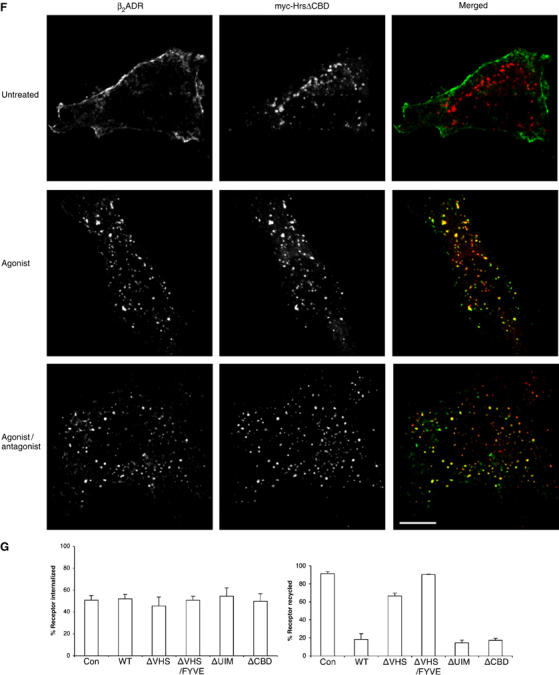

Figure 5acd.

Hrs, but not Tsg101 or Vps4, is essential for the sequence-directed recycling mechanism. (A) Western blot of total cellular levels of Hrs in HeLa cells following transfection with either control (nonsilencing) siRNA or Hrs siRNA. Lysates were also blotted for GapDH to test the specificity of knockdown. (C) Surface receptor was measured by flow cytometry in HeLa cells co-expressing Flag-β2ADR, Flag-μOR, or Flag-V2R 362T, and either control (non-silencing) siRNA or Hrs siRNA. Cells were treated as in Figures 1B and 2C. A minimum of 10 000 cells were counted. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. from three independent experiments. *P<0.05. (D) Tsg101 levels in cells transfected with either control (nonsilencing) siRNA or Tsg101 siRNA were assessed by Western blotting. Lysates were also blotted for GapDH to test the specificity of knockdown. HeLa cells expressing Flag-β2ADR with control (nonsilencing) siRNA or Tsg101 siRNA were assessed for recycling (as in (B)) by flow cytometry. All flow cytometry results shown are the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments.

Recycling of β2ADRs was strongly inhibited by siRNA-mediated depletion of Hrs (Figure 5B). This effect was specific because recycling of β2ADRs was unaffected in cells transfected with a control siRNA (Figure 5B). Consistent with the Hrs overexpression data, internalized β2ADRs ‘trapped' in Hrs-knockdown cells remained localized in early endosomes, as indicated by colocalization with endogenous EEA-1 (Figure 5B) and not with late endosomal markers (not shown). The enlargement of EEA-1-positive early endosomes under conditions of Hrs knockdown has been noted previously (Komada and Soriano, 1999; Lu et al, 2003; Marchese et al, 2003b). An essential role of Hrs in β2ADR recycling was confirmed using flow cytometry (Figure 5C). Knockdown of Hrs also prevented sequence-directed recycling of the μOR, whereas ‘default' recycling of V2R 362T was not detectably inhibited (Figure 5C). In addition, Hrs knockdown did not affect the internalization or recycling of transferrin (not shown). These results further support the conclusion that Hrs is specifically required for sequence-directed recycling of GPCRs.

Sequence-directed recycling does not require other Class E VPS homologues

Hrs/Vps27p mediates other functions in endocytic membrane trafficking, including vacuolar/lysosomal and prevacuole-to-Golgi trafficking (Piper et al, 1995; Katzmann et al, 2002). In these pathways, Hrs/Vps27p functions together with a number of other Class E VPS genes, and depleting or inhibiting any of these gene products produces a similar effect on membrane traffic (Raymond et al, 1992; Katzmann et al, 2002). Thus, we asked if the function of Hrs in sequence-directed recycling also occurs in concert with other Class E homologues. To accomplish this, we focused on two Class E homologues, Tsg101 and Vps4/Skd1. Tsg101 is the mammalian homolog of yeast Vps23p, a core protein component of the ESCRT-I complex required for both vacuolar/lysosomal and prevacuole-to-Golgi sorting of membrane cargo (Raymond et al, 1992; Babst et al, 2000; Katzmann et al, 2001; Bishop et al, 2002). Vps4/Skd1 is a AAA family ATPase that is also required for both vacuolar/lysosomal and prevacuole-to-Golgi sorting (Babst et al, 1997; Marchese et al, 2003b; Hislop et al, 2004).

Knockdown of Tsg101 by siRNA (Garrus et al, 2001), which efficiently inhibits ubiquitination-directed lysosomal sorting in HeLa cells (Bishop et al, 2002; Hislop et al, 2004), did not detectably affect recycling of the β2ADR (Figure 5D). This failure to inhibit β2ADR recycling was significant because effective protein knockdown was confirmed by Western blot (Figure 5D) and effective inhibition of EGF receptor degradation was confirmed previously using the same siRNA and transfection protocol in these cells (Hislop et al, 2004). Furthermore, Tsg101 knockdown did not detectably inhibit (Hrs-sensitive) recycling of the μOR, although effective protein knockdown was confirmed in these experiments as well (not shown).

Two mutants of Vps4/Skd1, E228Q (an ATP hydrolysis-deficient mutant) and K173Q (an ATP-binding-deficient mutant), function as dominant-negative inhibitors of lysosomal sorting when overexpressed (Bishop and Woodman, 2000; Marchese et al, 2003b; Hislop et al, 2004). GFP-tagged versions of these constructs retain potent dominant-negative activity (Garrus et al, 2001), as verified in our hands by inhibition of lysosomal sorting in HeLa cells (Hislop et al, 2004). Agonist-induced internalization of the β2ADR occurred normally in cells expressing both mutant versions of Vps4. In addition, overexpression of mutant Vps4 constructs did not detectably inhibit recycling of either the β2ADR (Figure 5E) or the μOR (not shown). Together, these results indicate that sequence-directed recycling, while strongly dependent on Hrs, does not require other Class E VPS homologues that function together with Hrs in other membrane-trafficking functions.

Functional requirement of the Hrs-sensitive recycling mechanism for receptor resensitization and sustained cell signaling

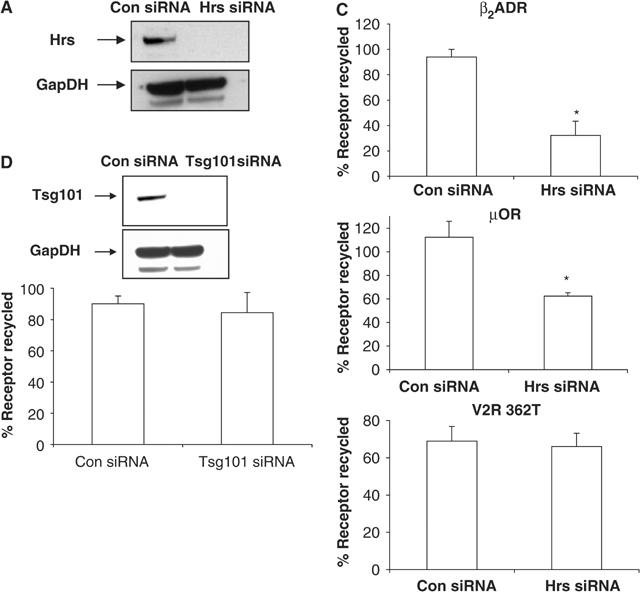

To assess the functional importance of Hrs-sensitive recycling, we investigated the effect of disrupting Hrs function on agonist-dependent β2ADR signaling via adenylyl cyclase. The β2ADR signals by increasing cellular levels of cyclic AMP (cAMP) in response to agonist activation. The receptor then undergoes rapid desensitization, a process mediated by phosphorylation of cytoplasmic Ser/Thr residues followed by endocytosis (Rockman et al, 2002). Recycling of the β2ADR rapidly restores the complement of surface receptors that is critical for ‘resensitization' of cellular responsiveness after agonist removal and for producing sustained cellular responsiveness to agonist (Pippig et al, 1995; Rockman et al, 2002). Measurement of whole-cell cAMP production following acute agonist exposure (90 s) of β2ADR-expressing cells produced a rapid increase in cellular cAMP levels (Figure 6A, bar 2). This response diminished within 10 min after agonist addition (Figure 6A, bar 3), consistent with rapid desensitization of receptor signaling. Neither acute signaling nor rapid desensitization of β2ADR was detectably affected by Hrs overexpression (Figure 6A, bars 1–6). Following agonist washout for 30 min (Figure 6A, bars 7 and 8), control cells recovered full responsiveness to a second agonist challenge, consistent with the process of receptor resensitization (Pippig et al, 1995). In marked contrast, the cAMP response to agonist re-challenge was greatly reduced in Hrs-overexpressing cells (Figure 6A, compare bars 9 and 10). Comparison of the cAMP response to agonist re-challenge, relative to the primary challenge, revealed a nearly complete inhibition of resensitization (Figure 6B). Similar results were observed using siRNA-mediated knockdown of Hrs. Again, Hrs knockdown did not detectably affect basal cAMP levels, acute response to the primary agonist challenge or rapid desensitization of β2ADR signaling (Figure 6C, bars 1–6). However, knockdown of Hrs expression strongly inhibited β2ADR resensitization, as indicated by a loss of a sustained response upon agonist rechallenge (Figure 6C, bars 9 and 10, and Figure 6D). Therefore, Hrs-dependent recycling is critical for functional resensitization and sustained responsiveness of β2ADR signaling in intact cells.

Figure 6.

Manipulation of Hrs prevents functional resensitization of β2ADR signaling. (A, B) HeLa cells co-expressing Flag-β2ADR and either pcDNA3 or myc-Hrs, or (C, D) HeLa cells transfected with Flag-β2ADR and either control (nonsilencing) siRNA or Hrs siRNA were incubated with 0.5 mM IBMX prior to agonist treatment (isoproterenol (Iso), 10 μM) as indicated. Cells were measured for whole-cell cAMP production as described in Materials and methods. For (A) and (C), the concentration of cAMP was normalized to 90 s Iso treatment. (B) and (D) show the agonist-dependent increase from the first and second challenges of agonist. All results shown are the mean±s.e.m. of four independent experiments. *P<0.05.

Discussion

The present results identify an unexpected function of Hrs in mediating recycling of two well-characterized GPCRs that are prototypic of the largest known class of signaling receptors in animal cells (Pierce et al, 2002). This function of Hrs in recycling is distinct from the previously defined role of Hrs in lysosomal sorting and downregulation of signaling receptors via VPS/ESCRT pathway (Katzmann et al, 2002; Raiborg and Stenmark, 2002). These divergent sorting pathways also produce essentially opposite functional effects on cell signaling, contributing to the generation of sustained versus transient cell signaling responses (Sorkin and Von Zastrow, 2002).

While signal-mediated lysosomal/vacuolar sorting is well established, many integral membrane proteins are thought to recycle to the plasma membrane via a process of bulk membrane flow that requires no specific targeting signals (Gruenberg and Stenmark, 2004; Maxfield and McGraw, 2004). However, an increasing number of mammalian signaling receptors are being found to undergo ‘active' sorting to the recycling pathway, via a diverse set of cytoplasmic targeting sequences (Cong et al, 2001; Gage et al, 2001; Li et al, 2002; Galet et al, 2003; Vargas and Von Zastrow, 2004) that appear to bind to distinct cytoplasmic proteins (Tanowitz and von Zastrow, 2003; Vargas and Von Zastrow, 2004). A diversity of GPCR recycling sequences could confer important specificity on the regulation of individual signaling receptors in metazoan cells. However, most studies suggest that distinct GPCRs recycle to the plasma membrane by similar membrane pathway(s) (von Zastrow and Kobilka, 1992; Cao et al, 1998; Marullo et al, 1999; Paasche et al, 2001; Fan et al, 2003). These considerations prompted us to search for a ‘core' sorting mechanism that can actively direct endocytosed receptors, via distinct cis-acting sequences, into a conserved recycling pathway.

The present results indicate that Hrs is required for recycling of both the β2ADR and μOR, distinct GPCRs that contain different cytoplasmic targeting sequences. A role of Hrs in this process was first indicated by the ability of Hrs overexpression to specifically inhibit recycling of these receptors. Furthermore, a cis-acting sequence derived from the β2ADR was sufficient to confer Hrs-dependent recycling when fused to V2R 362T that recycles efficiently by ‘default' (Innamorati et al, 1998, 2001) and independently of Hrs (this study). Depletion of endogenous Hrs using siRNA produced a phenotype identical to overexpression, establishing an essential role of Hrs in sequence-directed recycling. The observation that Hrs overexpression and knockdown both have inhibitory effects on trafficking has been previously reported (Raiborg et al, 2001a; Bache et al, 2003; Hislop et al, 2004). As Hrs has multiple interaction domains and is thought to exist in a large protein complex (Chin et al, 2001), overexpression could titrate out associated proteins present in limiting amount and inhibit their function (Morino et al, 2004), while knockdown could prevent the formation of such protein complexes that may be required for cargo to be transported.

Despite the ability of the β2ADR-derived tail sequence to link receptors functionally to the Hrs-dependent sorting mechanism, we have been unable to detect a specific interaction of β2ADR with Hrs (data not shown). However, the present results implicate the N-terminal VHS domain of Hrs in the sequence-directed recycling mechanism and thus makes a significant step toward defining protein interactions that could link specific GPCRs to Hrs. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence for a specific functional role of the VHS domain in Hrs. It is interesting to note that the VHS domain in another type of sorting protein, the GGA protein, that regulates trafficking between the endosome/lysosome and TGN, has been shown to bind mannose 6-phosphate receptors (Puertollano et al, 2001). We presently favor the hypothesis that the VHS domain interacts with recycling receptors indirectly via another (as yet unidentified) linker protein interaction, or that Hrs may interact with receptor tails in concert with other proteins that increase the avidity of potential sorting interactions. This idea is also in accord with biochemical data indicating that Hrs exists in large multi-protein complex(es) (Bache et al, 2003), the composition of which may be dynamically regulated (Chin et al, 2001). Future studies aim to explore these hypotheses further.

It is interesting that ubiquitination of the β2ADR is not required for Hrs-dependent recycling. While certain membrane cargo have been observed to undergo Hrs/Vps27p-dependent sorting without cargo ubiquitination (Bilodeau et al, 2002; Hislop et al, 2004), in many cases Hrs-dependent sorting activities require cargo ubiquitination (Bishop et al, 2002; Katzmann et al, 2002; Gruenberg and Stenmark, 2004), and ubiquitination is required for lysosomal sorting of the β2ADR (Shenoy et al, 2001). Our results were supported further by the observation that the UIM domain of Hrs is not required for dominant-negative effects on sequence-directed recycling. Interestingly, studies in yeast have demonstrated that the UIM of Vps27p is required for vacuolar targeting of the GPCR Ste3p (ligand-independent process), while cycling of the Golgi protein Vps10p, which also requires Vps27p (see below), does not (Bilodeau et al, 2002). Thus, our results suggest that Hrs may mediate distinct sorting functions on ubiquitinated relative to nonubiquitinated signaling receptors.

Studies in yeast have clearly established an essential role of Hrs/Vps27p both in MVB/vacuolar sorting and in cycling of certain membrane cargo (e.g., Vps10p) from the prevacuolar compartment (PVC) to the Golgi (Piper et al, 1995; Bilodeau et al, 2002). However, both of these functions require other Class E VPS gene products (Raymond et al, 1992; Babst et al, 1997, 2000; Katzmann et al, 2001), which is in marked contrast to the specific requirement of Hrs (but not Tsg101 or Vps4) for recycling of signaling receptors shown in this study. Although there is evidence that Ste3p recycles to the plasma membrane following ligand-dependent activation and endocytosis (Chen and Davis, 2000, 2002), Ste3p can exit the PVC in a Vps27p-independent manner (Gerrard et al, 2000). Furthermore, recycling of Ste3p has been proposed to occur by ‘default' (Chen and Davis, 2002), similar to the Hrs-independent recycling of the TfnR (Raiborg et al, 2001a) and mutant V2 receptors verified in the present study. Moreover, recent studies indicate that plasma membrane recycling of other yeast integral membrane proteins, such as Snc1p and Fur4p, is not detectably inhibited (and may even be enhanced) by disruption of Class E gene function (Bugnicourt et al, 2004). Thus, we believe that the present results identify a novel function of Hrs in a specific sequence-directed sorting mechanism, which is distinct from previously described membrane trafficking functions of Hrs/Vps27p in any cell type.

We also demonstrated that Hrs-dependent recycling is functionally important for producing sustained cellular responsiveness following activation of the β2ADR, a prototypic signaling receptor for which recycling is thought to mediate critical signaling functions in vivo (Lefkowitz et al, 1998; Xiang and Kobilka, 2003). Therefore, the physiological function of Hrs may not simply be to attenuate signaling responses, but could also prolong certain signaling responses mediated by receptors for which recycling/resensitization represents a major regulatory pathway. This consideration may provide useful insight for interpreting the profound and varied effects of Hrs deletion on embryonic development, which have been interpreted so far only in the context of Hrs attenuating signal transduction via the MVB/lysosome pathway (Lloyd et al, 2002).

In conclusion, the present results identify an unanticipated function of Hrs as a core component of a specialized mechanism of recycling, and demonstrates an essential function of this mechanism in producing sustained signaling responsiveness by a prototypic GPCR. This provides novel insight into the diverse cellular functions of Hrs, and suggests a new mechanistic link between processes of receptor membrane trafficking and cell signaling in complex metazoan cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

Isoproteronol, alprenolol, etorphine and naloxone were obtained from Sigma. [Arg8]vasopressin was obtained from Bachem.

Eukaryotic expression constructs and siRNA oligos

Flag-human β2ADR, Flag-human V2 vasopressin truncation mutant (V2R 362T) and Flag-mouse μOR have been previously described (Innamorati et al, 1998; Cao et al, 1999; Tanowitz and von Zastrow, 2003). The myc-tagged Hrs in pcDNA3 was a gift from Harald Stenmark (Norwegian Radium Hospital, Norway). The chimera of V2R 362T/β2ADR C-terminal tail was constructed by introducing an EcoRV site in the full-length V2R at residue 362 by site-directed mutagenesis (Quick Change, Stratagene). Then, both the β2ADR and V2R were digested with EcoRV/Xba1 (β2ADR has an endogenous EcoRV site) and ligated to form a fusion of V2R 362/β2ADR. Myc-Hrs ΔVHS was created by introducing an EcoR1 site at residue 145. An EcoR1 site exists 3′ of the myc-tag; thus an EcoR1 digestion released an N-terminal fragment of myc-Hrs (aa 1–145), religation of which resulted in Myc-Hrs ΔVHS (aa 146–776). Myc-Hrs ΔVHS/FYVE was created by introducing an EcoR1 site at position 225. An EcoR1 digestion and religation results in Myc-Hrs ΔVHS/FYVE (aa 226–776). Myc-Hrs ΔUIM was created by sequential introduction of two BamH1 sites flanking the UIM (aa 258–280). A HindIII/BamH1 digestion was performed, followed by religation of the HindIII/BamH1 fragments. Myc-Hrs ΔCBD was created by introducing a stop codon at Leucine 772. Flag-β2ADR 0K (all 16 lysines mutated to arginine) was provided by B Kobilka (Stanford University, California). GFP-tagged WT and mutant Vps4 was provided by W Sundquist (University of Utah). Knockdown of Tsg101 and Hrs using siRNA was achieved by transfection of duplex RNA oligos (Qiagen) corresponding to the part of the coding region of human Tsg101 or human Hrs as previously described (Garrus et al, 2001; Bache et al, 2003). Control cells were transfected with nonsense duplex RNA oligos (AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACG, Qiagen).

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FCS, glutamine (0.3 mg/ml) and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Transient transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and cells assayed 24 h post-transfection, except for siRNA transfections where cells were assayed 72 h post-transfection.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal imaging

Visualization of flag receptors and myc-Hrs was carried out using indirect immunofluorescence of HeLa cells. Transfected cells were plated onto coverslips 4–6 h after transfection. Following incubation with rabbit anti-Flag antibody (Sigma), treatments with agonist were carried out within 24 h post-transfection and cells fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were incubated with mouse anti-myc antibody in blocking solution (PBS plus 1% BSA and 10% goat serum, pH 7.4). The anti-myc antibody (9E10) developed by J Michael Bishop was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City, IA 52242. Cells were then incubated with goat anti-mouse Texas red and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated antibodies (Molecular Probes) in blocking solution. For EEA-1 localization, an EEA-1 antibody directly conjugated to FITC was used (Transduction Laboratories), followed by incubation with rabbit anti-FITC antibody (Zymed) to amplify the signal. Late endosomes/lysosomes were localized using LAMP1 monoclonal antibody obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Data Bank. Cells were examined using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal laser microscope under an oil immersion × 63 lens.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was used to quantitate internalization and recycling of receptors by measuring levels of cell surface Flag-tagged receptor. Adherent cells were fed with M1 anti-Flag antibody (30 min, 37°C) prior to treatment with agonist (10 μM, 20 min). Cells were then washed and treated with either the appropriate antagonist (for β2ADR- and μOR-expressing cells) or media only (V2R 362T). Cells were then lifted with trypsin, washed with PBS and incubated with sheep anti-mouse IgG conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE, Sigma). As an internal control for transfection efficiency, cells were also transfected with GFP and values obtained for cells positive for both GFP and PE staining. The fluorescence intensity of 10 000 cells was collected for each sample and treatments were performed in duplicate using a flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Palo Alto, CA). All experiments were conducted at least three times. Percentage of receptor recycling was calculated from the proportion of internalized receptor (as indicated by a decrease of immunoreactive surface receptor with agonist compared to unstimulated cells) that was recovered at the cell surface.

Western blotting

Immunoblotting of total cellular levels of Hrs and Tsg101 was as previously described (Hislop et al, 2004). The proteins were probed for Hrs (provided by H Stenmark, The Norwegian Radium Hospital), Tsg101 (sc-7964, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or GapDH (Chemicon) by immunoblotting using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG or sheep anti-mouse IgG (Amersham Biosciences), and SuperSignal detection reagent (Pierce). Immunoblots were analyzed by densitometry using FluorChem 2.0 software (AlphaInnotech Corp.).

Whole-cell cAMP measurements

Receptor signaling was determined by agonist-induced accumulation of cAMP. Cells were pretreated with 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX, Sigma) for 5 min prior to stimulation with agonist isoproterenol (10 μM) for the indicated time periods in the continued presence of IBMX. To measure resensitization, cells were desensitized by a 10-min agonist treatment, washed in DMEM/0.1% BSA and incubated in media for 30 min to allow for recycling, then re-challenged with agonist (90 s). Cells were then rapidly washed with ice-cold PBS and solubilized with 0.1 M HCl/0.1% Triton X-100 and centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min. The lysates (100 μl) were used to measure levels of cAMP with a competitive immunoassay kit (Assay Designs) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each treatment was performed in duplicate and experiments repeated at least three times. All cAMP concentrations were corrected for protein levels.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using paired Student's t-test. Differences are considered significant at P<0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Harald Stenmark for reagents and advice, Brian Kobilka for β2ADR 0K and Wesley Sundquist for providing Vps4 constructs. We also thank James Hislop for the Hrs ΔUIM construct, Keith Mostov and Michael Tanowitz for helpful comments concerning the manuscript. These studies were supported by research funds from the National Institutes of Health. ACH was funded by a postdoctoral research fellowship from the American Heart Association, Western States Affiliate.

References

- Babst M, Odorizzi G, Estepa EJ, Emr SD (2000) Mammalian tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101) and the yeast homologue, Vps23p, both function in late endosomal trafficking. Traffic 1: 248–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M, Sato TK, Banta LM, Emr SD (1997) Endosomal transport function in yeast requires a novel AAA-type ATPase, Vps4p. EMBO J 16: 1820–1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bache KG, Raiborg C, Mehlum A, Stenmark H (2003) STAM and Hrs are subunits of a multivalent ubiquitin-binding complex on early endosomes. J Biol Chem 278: 12513–12521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilodeau PS, Urbanowski JL, Winistorfer SC, Piper RC (2002) The Vps27p Hse1p complex binds ubiquitin and mediates endosomal protein sorting. Nat Cell Biol 4: 534–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop N, Horman A, Woodman P (2002) Mammalian class E vps proteins recognize ubiquitin and act in the removal of endosomal protein–ubiquitin conjugates. J Cell Biol 157: 91–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop N, Woodman P (2000) ATPase-defective mammalian VPS4 localizes to aberrant endosomes and impairs cholesterol trafficking. Mol Biol Cell 11: 227–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugnicourt A, Froissard M, Sereti K, Ulrich HD, Haguenauer-Tsapis R, Galan JM (2004) Antagonistic roles of ESCRT and Vps Class C/HOPS complexes in the recycling of yeast membrane proteins. Mol Biol Cell 15: 4203–4214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao TT, Deacon HW, Reczek D, Bretscher A, von Zastrow M (1999) A kinase-regulated PDZ-domain interaction controls endocytic sorting of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Nature 401: 286–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao TT, Mays RW, von Zastrow M (1998) Regulated endocytosis of G-protein-coupled receptors by a biochemically and functionally distinct subpopulation of clathrin-coated pits. J Biol Chem 273: 24592–24602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Davis NG (2000) Recycling of the yeast a-factor receptor. J Cell Biol 151: 731–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Davis NG (2002) Ubiquitin-independent entry into the yeast recycling pathway. Traffic 3: 110–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin LS, Raynor MC, Wei X, Chen HQ, Li L (2001) Hrs interacts with sorting nexin 1 and regulates degradation of epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem 276: 7069–7078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong M, Perry SJ, Hu LA, Hanson PI, Claing A, Lefkowitz RJ (2001) Binding of the beta2 adrenergic receptor to N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor regulates receptor recycling. J Biol Chem 276: 45145–45152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikic I (2003) Mechanisms controlling EGF receptor endocytosis and degradation. Biochem Soc Trans 31: 1178–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan GH, Lapierre LA, Goldenring JR, Richmond A (2003) Differential regulation of CXCR2 trafficking by Rab GTPases. Blood 101: 2115–2124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage RM, Kim KA, Cao TT, von Zastrow M (2001) A transplantable sorting signal that is sufficient to mediate rapid recycling of G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem 276: 44712–44720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon AW, Kallal L, Benovic JL (1998) Role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in agonist-induced down-regulation of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem 273: 6976–6981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galet C, Min L, Narayanan R, Kishi M, Weigel NL, Ascoli M (2003) Identification of a transferable two-amino-acid motif (GT) present in the C-terminal tail of the human lutropin receptor that redirects internalized G protein-coupled receptors from a degradation to a recycling pathway. Mol Endocrinol 17: 411–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrus JE, von Schwedler UK, Pornillos OW, Morham SG, Zavitz KH, Wang HE, Wettstein DA, Stray KM, Cote M, Rich RL, Myszka DG, Sundquist WI (2001) Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell 107: 55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard SR, Levi BP, Stevens TH (2000) Pep12p is a multifunctional yeast syntaxin that controls entry of biosynthetic, endocytic and retrograde traffic into the prevacuolar compartment. Traffic 1: 259–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg J, Stenmark H (2004) The biogenesis of multivesicular endosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L (1999) Gettin' down with ubiquitin: turning off cell-surface receptors, transporters and channels. Trends Cell Biol 9: 107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hislop JA, Marley A, von Zastrow M (2004) Role of mammalian VPS proteins in ubiquitination-independent trafficking of G protein-coupled receptors to lysosomes. J Biol Chem 279: 22522–22531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innamorati G, Le Gouill C, Balamotis M, Birnbaumer M (2001) The long and the short cycle. Alternative intracellular routes for trafficking of G-protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem 276: 13096–13103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innamorati G, Sadeghi HM, Tran NT, Birnbaumer M (1998) A serine cluster prevents recycling of the V2 vasopressin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 2222–2226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann DJ, Babst M, Emr SD (2001) Ubiquitin-dependent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway requires the function of a conserved endosomal protein sorting complex, ESCRT-I. Cell 106: 145–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann DJ, Odorizzi G, Emr SD (2002) Receptor downregulation and multivesicular-body sorting. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 893–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch T, Schulz S, Pfeiffer M, Klutzny M, Schroder H, Kahl E, Hollt V (2001) C-terminal splice variants of the mouse mu-opioid receptor differ in morphine-induced internalization and receptor resensitization. J Biol Chem 276: 31408–31414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch T, Schulz S, Schroder H, Wolf R, Raulf E, Hollt V (1998) Carboxyl-terminal splicing of the rat mu opioid receptor modulates agonist-mediated internalization and receptor resensitization. J Biol Chem 273: 13652–13657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komada M, Soriano P (1999) Hrs, a FYVE finger protein localized to early endosomes, is implicated in vesicular traffic and required for ventral folding morphogenesis. Genes Dev 13: 1475–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz JB, Perkins JP (1992) Isoproterenol-initiated beta-adrenergic receptor diacytosis in cultured cells. Mol Pharmacol 41: 375–381 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz RJ, Pitcher J, Krueger K, Daaka Y (1998) Mechanisms of beta-adrenergic receptor desensitization and resensitization. Adv Pharmacol 42: 416–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JG, Chen C, Liu-Chen LY (2002) Ezrin-radixin-moesin-binding phosphoprotein-50/Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor (EBP50/NHERF) blocks U50,488H-induced down-regulation of the human kappa opioid receptor by enhancing its recycling rate. J Biol Chem 277: 27545–27552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd TE, Atkinson R, Wu MN, Zhou Y, Pennetta G, Bellen HJ (2002) Hrs regulates endosome membrane invagination and tyrosine kinase receptor signaling in Drosophila. Cell 108: 261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Hope LW, Brasch M, Reinhard C, Cohen SN (2003) TSG101 interaction with HRS mediates endosomal trafficking and receptor down-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 7626–7631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchese A, Chen C, Kim YM, Benovic JL (2003a) The ins and outs of G protein-coupled receptor trafficking. Trends Biochem Sci 28: 369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchese A, Raiborg C, Santini F, Keen JH, Stenmark H, Benovic JL (2003b) The E3 ubiquitin ligase AIP4 mediates ubiquitination and sorting of the G protein-coupled receptor CXCR4. Dev Cell 5: 709–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh EW, Leopold PL, Jones NL, Maxfield FR (1995) Oligomerized transferrin receptors are selectively retained by a lumenal sorting signal in a long-lived endocytic recycling compartment. J Cell Biol 129: 1509–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marullo S, Faundez V, Kelly RB (1999) Beta 2-adrenergic receptor endocytic pathway is controlled by a saturable mechanism distinct from that of transferrin receptor. Receptors Channels 6: 255–269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield FR, McGraw TE (2004) Endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor S, Presley JF, Maxfield FR (1993) Sorting of membrane components from endosomes and subsequent recycling to the cell surface occurs by a bulk flow process. J Cell Biol 121: 1257–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morino C, Kato M, Yamamoto A, Mizuno E, Hayakawa A, Komada M, Kitamura N (2004) A role for Hrs in endosomal sorting of ligand-stimulated and unstimulated epidermal growth factor receptor. Exp Cell Res 297: 380–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paasche JD, Attramadal T, Sandberg C, Johansen HK, Attramadal H (2001) Mechanisms of endothelin receptor subtype-specific targeting to distinct intracellular trafficking pathways. J Biol Chem 276: 34041–34050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola AL, Lin S, Kobilka BK (1997) Site-specific fluorescence labeling of the beta2 adrenergic receptor amino terminus. Anal Biochem 254: 88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SJ, Lefkowitz RJ (2002) Arresting developments in heptahelical receptor signaling and regulation. Trends Cell Biol 12: 130–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ (2002) Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 639–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper RC, Cooper AA, Yang H, Stevens TH (1995) VPS27 controls vacuolar and endocytic traffic through a prevacuolar compartment in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 131: 603–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pippig S, Andexinger S, Lohse MJ (1995) Sequestration and recycling of beta 2-adrenergic receptors permit receptor resensitization. Mol Pharmacol 47: 666–676 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puertollano R, Aguilar RC, Gorshkova I, Crouch RJ, Bonifacino JS (2001) Sorting of mannose 6-phosphate receptors mediated by the GGAs. Science 292: 1712–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C, Bache KG, Gillooly DJ, Madshus IH, Stang E, Stenmark H (2002) Hrs sorts ubiquitinated proteins into clathrin-coated microdomains of early endosomes. Nat Cell Biol 4: 394–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C, Bache KG, Mehlum A, Stang E, Stenmark H (2001a) Hrs recruits clathrin to early endosomes. EMBO J 20: 5008–5021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C, Bache KG, Mehlum A, Stenmark H (2001b) Function of Hrs in endocytic trafficking and signalling. Biochem Soc Trans 29: 472–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C, Bremnes B, Mehlum A, Gillooly DJ, D'Arrigo A, Stang E, Stenmark H (2001c) FYVE and coiled-coil domains determine the specific localisation of Hrs to early endosomes. J Cell Sci 114: 2255–2263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C, Stenmark H (2002) Hrs and endocytic sorting of ubiquitinated membrane proteins. Cell Struct Funct 27: 403–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond CK, Howald-Stevenson I, Vater CA, Stevens TH (1992) Morphological classification of the yeast vacuolar protein sorting mutants: evidence for a prevacuolar compartment in class E vps mutants. Mol Biol Cell 3: 1389–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockman HA, Koch WJ, Lefkowitz RJ (2002) Seven-transmembrane-spanning receptors and heart function. Nature 415: 206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy SK, McDonald PH, Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ (2001) Regulation of receptor fate by ubiquitination of activated beta 2-adrenergic receptor and beta-arrestin. Science 294: 1307–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin A, Von Zastrow M (2002) Signal transduction and endocytosis: close encounters of many kinds. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 600–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanowitz M, von Zastrow M (2003) A novel endocytic recycling signal that distinguishes the membrane trafficking of naturally occuring opioid receptors. J Biol Chem 278: 45978–45986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas GA, Von Zastrow M (2004) Identification of a novel endocytic recycling signal in the D1 dopamine receptor. J Biol Chem 279: 37461–37469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zastrow M (2003) Mechanisms regulating membrane trafficking of G protein-coupled receptors in the endocytic pathway. Life Sci 74: 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zastrow M, Kobilka BK (1992) Ligand-regulated internalization and recycling of human beta 2-adrenergic receptors between the plasma membrane and endosomes containing transferrin receptors. J Biol Chem 267: 3530–3538 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley HS, Burke PM (2001) Regulation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling by endocytic trafficking. Traffic 2: 12–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Kobilka B (2003) The PDZ-binding motif of the beta2-adrenoceptor is essential for physiologic signaling and trafficking in cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 10776–10781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]