Abstract

The actin filament-associated protein and Src-binding partner, AFAP-110, is an adaptor protein that links signaling molecules to actin filaments. AFAP-110 binds actin filaments directly and multimerizes through a leucine zipper motif. Cellular signals downstream of Src527F can regulate multimerization. Here, we determined recombinant AFAP-110 (rAFAP-110)-bound actin filaments cooperatively, through a lateral association. We demonstrate rAFAP-110 has the capability to cross-link actin filaments, and this ability is dependent on the integrity of the carboxy terminal actin binding domain. Deletion of the leucine zipper motif or PKC phosphorylation affected AFAP-110's conformation, which correlated with changes in multimerization and increased the capability of rAFAP-110 to cross-link actin filaments. AFAP-110 is both a substrate and binding partner of PKC. On PKC activation, stress filament organization is lost, motility structures form, and AFAP-110 colocalizes strongly with motility structures. Expression of a deletion mutant of AFAP-110 that is unable to bind PKC blocked the effect of PMA on actin filaments. We hypothesize that upon PKC activation, AFAP-110 can be cooperatively recruited to newly forming actin filaments, like those that exist in cell motility structures, and that PKC phosphorylation effects a conformational change that may enable AFAP-110 to promote actin filament cross-linking at the cell membrane.

INTRODUCTION

The actin filament-associated protein of 110 kDa, AFAP-110, was originally identified as a Src527F binding partner that colocalized with actin filaments (reviewed in Baisden et al., 2001a). AFAP-110 binds to actin filaments via a carboxy terminal actin binding domain and colocalizes with stress filaments and the cortical actin matrix along the cell membrane (Qian et al., 1998, 2000). AFAP-110 also binds to Src via SH3 and SH2 binding motifs (Guappone and Flynn, 1997; Guappone et al., 1998) and contains additional amino terminal protein binding modules including two pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, a leucine zipper motif, a target region for serine/threonine phosphorylation as well as other hypothetical protein-binding sites (Baisden et al., 2001a). AFAP-110 is hyperphosphorylated on ser/thr residues as well as tyrosine residues in Src transformed cells and contains numerous consensus sequences for phosphorylation by PKC (Kanner et al., 1991; Flynn et al., 1993).

Gel filtration analysis demonstrated that AFAP-110 exists as monomers as well as larger multimeric complexes in 1% NP-40 buffer and the multimeric associations were achieved in part through the carboxy terminal leucine zipper motif. Transformation by Src527F induces a change in AFAP-110 conformation that reduces multimeric AFAP-110 into a single complex in 1% NP-40 lysis buffer, predicted to contain either AFAP-110 dimers or trimers. In addition, Src527F coexpression prevented affinity-absorption of cellular AFAP-110 with the GST-cterm fusion proteins (Qian et al., 1998). Thus, it was hypothesized that in Src527F transformed cells, there may be a loss of function for the leucine zipper motif as evidenced by a reduction in its capacity to facilitate multimerization. Therefore, deletion of the leucine zipper motif within AFAP-110 could serve as a model system to study the effects of signaling on AFAP-110 function. Interestingly, deletion of the leucine zipper motif enables AFAP-110 (AFAP-110Δlzip) to induce changes in actin filament integrity in a manner similar to activated Src527F (Qian et al., 1998, 2000). This same deletion mutant is able to direct the activation of cellular tyrosine phosphorylation and Src family activation in an SH3-dependent manner and has the capability to direct changes in actin filament integrity via activation of Src signaling pathways (Baisden et al., 2001b). Thus, conformational changes in AFAP-100 could direct activation of signals that affect cell morphology.

Activation of PKC will alter actin filament organization (Kiley et al., 1992). One of the paradoxes of PKC activation is that there is a loss of stress filament integrity and reduced actin filament cross-linking across the cell; however, at the cell membrane there is general promotion of motility structure formation, which themselves contain increased concentrations of ordered and cross-linked actin filaments (Dwyer-Nield et al., 1996; Coghlan et al., 2000). PKC phosphorylation dramatically decreases the abilities of Fascin, MARCKS, SSeCKS, and VASP to cross-link actin filaments. Similarly, cSrc phosphorylation inhibits the ability of cortactin to cross-link actin filaments, which could be relevant to the loss of actin stress fibers concomitant with PKC activation (Hartwig et al., 1992; Lin et al. 1996; Yamakita et al., 1996; Huang et al., 1997, 1998; Ono et al., 1997; Ishikawa et al., 1998; Bubb et al., 1999; Harbeck et al., 2000; Bourguignon et al. 2001). However, it is also possible that one or more PKC substrates positioned along the cell membrane could contribute to promoting actin filament cross-linking in response to PKC activation, each of which would be important for organizing actin filaments in motility structures that form upon activation of PKC. One candidate effector protein to fulfill this function is AFAP-110. AFAP-110 is a predicted PKC substrate and has the capability to cross-link actin filaments, because it binds actin filaments directly and self-associates to form multimers, in vivo (Qian et al., 1998, 2000). We hypothesize that changes in the profile of multimerization of AFAP-110 in response to cellular signals could have a direct impact on AFAP-110's ability to cross-link actin filaments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Constructs

AFAP-110, AFAP-110Δcterm, and AFAP-110Δlzip DNA fragments were cloned into pGEX-6p-1 vector to construct pGEX-6p-1-AFAP-110, pGEX6p-1-AFAP-110Δcterm, and pGEX-6p-1-AFAP-110Δlzip vectors, respectively, from pGEX-2T-AFAP-110 series cutting with MluI and BamHI restriction enzymes. The pEGFP-c3 Expression system from Amersham Pharmacia (Piscataway, NJ) was used to express GFP-tagged forms of AFAP-110. AFAP-110 was cloned into this vector as previously described (Qian et al., 2000). CMV-AFAP-110Δ180–226 was previously described (Baisden et al., 2001). Fragments from CMV-AFAP-110 and CMV-AFAP-110Δ180–226 were subcloned into pEGFP-c3-AFAP-110 to create full-length, GFP-tagged forms of these mutants. Flag-myr-PKC was a kind gift from Alex Toker.

Reagents and Proteins

Recombinant PKCα was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Recombinant AFAP-110, recombinant AFAP-110Δlzip, and recombinant AFAP-110Δcterm were purified after production as a GST bacterial fusion protein, using the PreScission Protease system (Amersham Pharmacia) as previously described (Qian et al., 2000). G-actin and phalloidin-rhodamine were purchased from Cytoskeleton Co. (Denver, CO) DMEM and Basal Medium Eagle (BME), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), bisindolylmaleimide I, and 4α-phorbol 12,13-didecanoate (4α-PDD) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). AFAP-110 antibodies 4C3 and F1 were generated and characterized as previously described (Kanner et al., 1989; Flynn et al., 1993; Qian et al., 1999).

Actin Binding Assay

G-actin was polymerized to F-actin at 5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM ATP at room temperature (RT) for 1 h. Different concentrations of rAFAP-110 were incubated with 2 μM F-actin in 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM ATP, 50 mM KCl at RT for 30 min. The reactions were centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C, and then both pellets and supernatants were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE gel.

Analysis of Actin Binding

Binding constants were derived from the sedimentation of rAFAP-110 by actin. Accordingly, rAFAP-110 in the pellet and supernatant correspond to the bound and free rAFAP-110, respectively. The sum of densities of rAFAP-110 bands in the supernatant and pellet corresponds to the total mass of rAFAP-110 in the sample. The data representing the bound rAFAP-110 as a function of free rAFAP-110 were fit by nonlinear least squares to both the Langmuir (B = BMAX /(1 + Kd/F)) and Hill assays (B = BMAX/(1 + Kd/F)n) were performed with 2 μM F-actin filaments and different concentrations of rAFAP-110 in 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM ATP, and 50 mM KCl at 20,800 × g for 30 min at 4°C. After the centrifugation, both supernatant and pellets were analyzed by SDS-PAGE gel. Confocal microscopy assays were performed as described (Ishikawa et al., 1998). Briefly, 2 μM F-actin containing 10% rhodamine-phalloidin–labeled F-actin were mixed with different concentrations of rAFAP-110 or other purified recombinant proteins in 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM ATP, and 50 mM KCl at RT for 30 min. After the incubation, the reactions were applied between glass slides and coverslips and observed under confocal microscopy (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Samples for negative staining were adsorbed to grids coated with nitrocellulose and stabilized with carbon (Ernest F. Fullam, Latham, NY). Unbound protein was removed by successive washes with buffer and water before staining with 1% uranylacetate (Cooper and Pollard, 1982; Pollard and Cooper, 1982).

Cell Culture

Cos-1 cells were maintained and transfected as previously described (Guappone and Flynn, 1997). C3H10T1/2 cells were cultured as previously described (Qian et al., 2000). Transient transfections of C3H10T1/2 cells were carried out using SuperFect (QIAGEN, Santa Clarita, CA) as previously described (Qian et al., 2000).

In Vitro Kinase Assay

PKC kinase assays were carried out according to Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (Carter, 1997). Briefly, 10 μg rAFAP-110 purified as mentioned above was incubated at 30°C for 30 min with 0.5 μg recombinant PKCα in reaction buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 20 μg/ml phosphatidylserine, and 2 μg/ml diolein) to which 1 μCi [γ-32P]ATP was added. Reactions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Affinity-Absorption Assays

Both PH domains of AFAP-110 were amplified by PCR and subcloned from CMV-AFAP-110 into GEX-2T to create the GST-PH1 and GST-PH2 fusion proteins. Site-directed mutagenesis allowed for the in-frame deletion of residues 180–226, resulting in the generation of GST-PH1Δ180–226. For phosphorylation assays, the immobilized fusion proteins were either phosphorylated with recombinant PKCα (CalBiochem) or left unphosphorylated. The rPKCα was washed away from the pellet, and then the rAFAP-110 was released using PreScission protease, according to manufacturer's instructions. The fusion proteins were dialyzed into kinase buffer for kinase assays. For Western blot analysis, the absorbates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. For experiments involving serine/threonine kinase assays, the absorbates were washed five times with MTPBS (4.38 g NaCl, 1.14 g Na2HPO4, 0.24 NaH2PO4 in 500 ml H2O, pH 7.3) + 1% Triton X-100 and then four times with TBS. The absorbate/bead slurry was subjected to a colorimetric PKA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) as per protocol.

FPLC Assays

Protein samples were fractionated on Superdex 200 (bed volume, 24 ml) at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. Ninety-five fractions were collected containing 250 μl each. The molecular weight markers were run as the controls. Fractions were collected and analyzed by Western blot analysis, as previously described (Qian et al., 1998).

Phosphoamino Acid Analysis

C3H10T1/2 cells were grown to 60% confluence in 100-mm culture dishes, serum starved overnight, and then stimulated with 100 nM PMA or 100 nM 4α-PDD for 15 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed with 1 ml RIPA buffer. mAb 4C3, 1.5 μl, was used to immunoprecipitate AFAP-110 from the lysate, which was isolated via SDS-PAGE. The radioactive band was excised from the gel and subjected to partial acid hydrolysis and phosphoamino acid analysis (Boyle et al., 1991). After running the isolated amino acids on 2D TLC, the plates were imaged using a Phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Spots were identified by running labeled phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, and phosphotyrosine markers. Relative intensity compared with background of radiation from spots was quantitated with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Immunofluorescence

For PKC activation with PMA, C3H10T1/2 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding AFAP-110. Twenty-four hours after transfections, the cells were serum starved overnight. PMA at 100 nM was used to activate PKC for 60 min. Cells were fixed and permeablized as previously described (Qian et al., 1998). After washing, cells were labeled with BODIPY 650/665 phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and 4C3 antibody for 20 min. Cells were washed again and then labeled with ALEXA 488 (Molecular Probes) for 25 min. Cells were washed and mounted on slides with Fluoromount (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA). For serum induction experiments, C3H10T1/2 cells were serum starved overnight, and then serum-complete media was added. Cells on coverslips were washed and fixed at 15-min time points >2 h. Polyclonal antibody F1 and TRITC-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody were used to visualize endogenous AFAP-110, with washings as above. BODIPY 650/665 phalloidin was used to visualize actin. A Zeiss LSM 510 microscope (Thornwood, NY) was used to gather images, which were recolored from grayscale. Scale bars were generated and inserted by LSM 510 software (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

RESULTS

rAFAP-110 Cooperatively Binds to Actin Filaments through a Lateral Association

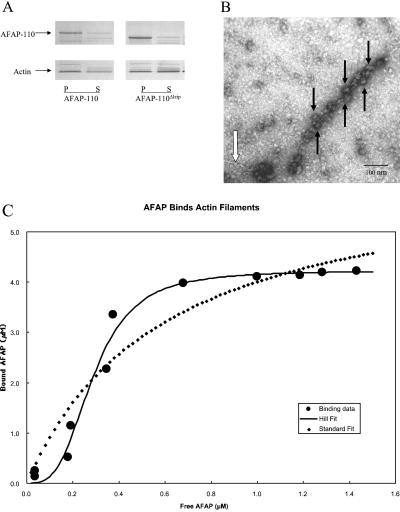

Previous data demonstrated that a polypeptide encoding the carboxy terminal actin binding domain in AFAP-110 was sufficient to direct binding to actin filaments, in vivo and in vitro (Qian et al., 2000). Here we sought to demonstrate that full-length recombinant AFAP-110 (rAFAP-110) was also capable of interacting with actin filaments in order to determine whether rAFAP-110 could cross-link actin filaments. Purified rAFAP-110 was shown to copellet with F-actin by high-speed copelleting assays, demonstrating a direct association, and deletion of the leucine zipper motif (AFAP-110Δlzip) did not abolish this direction association (150,000 × g; Figure 1A). An examination of negative stained actin filaments preincubated with rAFAP-110 revealed that F-actin was decorated with ellipsoid structures having a long axis of 15–30 nm (Figure 1B). These large structures likely represent multimers of rAFAP-110, because F-actin alone revealed no such structures, and this system included only purified rAFAP-110 and purified G-actin that had been polymerized to F-actin. The electron micrographs indicate that rAFAP-110 binds to the sides of actin filaments, which was supported by the fact that one mole of actin in filaments bound up to 1.7 mol of rAFAP-110 (Figure 1C). Interestingly, some actin filaments in the field with rAFAP-110 were occasionally naked and had no rAFAP-110 aggregates decorating them (white arrows, Figure 1B). These results suggested that the binding of rAFAP-110 to actin filaments could be cooperative. Evidence for cooperativity in binding was explored using high-speed copelleting data. The distinctive S-shaped appearance of the binding data when plotted on a linear scale indicated positive cooperativity (Figure 1C), and the data did not fit (least-squares fit) a noncooperative binding isotherm. However, the data were well described with a least-squares fit to the Hill equation, a cooperative model of binding. The best fit parameters Kd, BMAX, and Hill coefficient, n, were 0.29 μM, 4.2 μM, and 3.2, respectively (Figure 1C). Results of a second experiment were 0.24 μM, 1.5 μM, and 2.6 for Kd, BMAX, and n, respectively. A Hill coefficient greater than one confirms cooperative binding. The BMAX was about twofold greater than the 2 μM actin monomer concentration in the assay. The Kd is in the range of concentration of AFAP-110 in the cell (see DISCUSSION). These data indicate that AFAP-110 can bind actin filaments directly and that binding may serve to recruit additional AFAP-110 molecules to bind actin filaments.

Figure 1.

rAFAP-110 cooperatively binds to actin filaments. (A) Both rAFAP-110 and rAFAP-110Δlzip bind to actin filaments directly. Either rAFAP-110 or rAFAP-110Δlzip were incubated with actin filaments at 30°C for 30 min and was centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 1 h. Both supernatant (S) and pellet (P) were applied to 10% SDS-PAGE gel, followed by Coomassie blue stain. (B) EM negative staining. The purified rAFAP-110 was incubated with actin filaments. The negative staining image was taken at 16,000 magnification. Black arrows, rAFAP-110 aggregates; white arrow, actin filaments. (C) Graph of bound rAFAP-110 versus free rAFAP-110. rAFAP-110 at 0.18, 0.29, 0.70, 1.34, 2.63, 3.73, 4.67, 5.11, 5.34, 5.48, and 5.66 μM was incubated with 2 μM concentration of G-actin polymerized into actin filaments and were then centrifuged at 150,000 × g. Both supernatants (S) and pellets (P) were applied to SDS-PAGE gel, followed by Coomassie staining. Density of AFAP-110 determined by scanning densitometry was fit as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS.

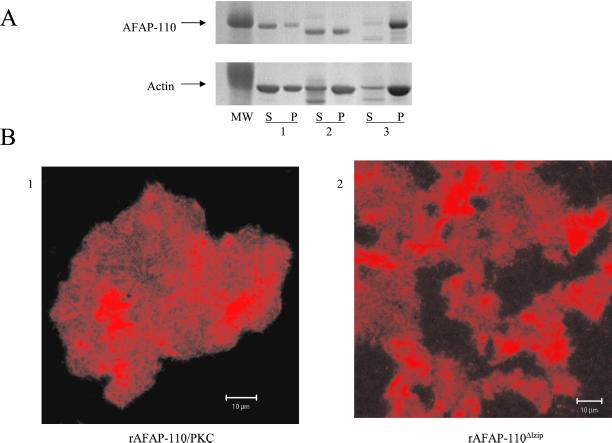

AFAP-110 Requires Its Carboxy Terminus to Cross-link Actin Filaments

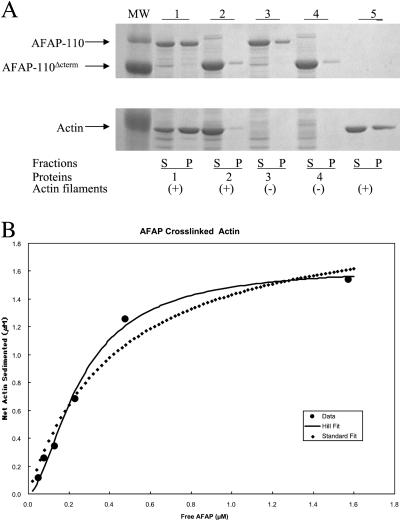

As AFAP-110 self-associates to form multimers in vivo and in vitro and has the capability to bind actin filaments directly, we tested biochemically whether AFAP-110 could cross-link actin filaments, using a low-speed centrifugation assay. Actin filaments are unable to efficiently pellet at 20,800 × g unless cross-linked to form heavier particles (either isotropic networked or bundled actin filaments; Cooper and Pollard, 1982; Pollard and Cooper, 1982; Meyer et al., 1990; Wachsstock et al., 1993; Rybakova et al., 1996). We found actin filaments efficiently sedimented when preincubated with rAFAP-110, whereas constructs of rAFAP-110 lacking the actin binding domain, e.g., rAFAP-110Δcterm or with no addition of rAFAP-110 proteins, were unable to efficiently pellet F-actin (Figure 2A), confirming that rAFAP-110 can cross-link actin filaments. Actin filament cross-linking, as determined by the amount of actin that sedimented at low speed, was dependent on the free concentration of rAFAP-110. At saturation, 81.5% of the actin (1.63 μM/2.0 μM total) was cross-linked and sedimented. Half maximal cross-linking occurred with 0.26 μM rAFAP-110, which is close to the predicted Kd for the association of rAFAP-110 with actin filaments, 0.29 μM AFAP-110 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

rAFAP-110 cross-links actin filaments through the carboxy terminal region. (A) Low-speed cosedimentation assay. The purified recombinant proteins were incubated with actin filaments and then were centrifuged at 20,800 × g. Both supernatants (S) and pellets (P) were applied to SDS-PAGE gel, followed by Coomassie staining. 1, rAFAP-110 with actin filaments; 2, rAFAP-110Δcterm with actin filaments; 3, rAFAP-110 only; 4, rAFAP-110Δcterm only; 5, actin filaments only. (B) Graph of cross-linked actin filaments versus free rAFAP-110. rAFAP-110 at 0.05, 0.11, 0.21, 0.43, 0.86, and 2.14 μM was incubated with the 2 μM concentration of G-actin polymerized into actin filaments. After the incubation, the reactions were centrifuged at 20,800 × g. Both supernatants and pellets were applied to SDS-PAGE gel, followed by the Western blot analysis to detect rAFAP-110 and Coomassie blue staining to detect actin, respectively. The data of cross-linked actin filaments and free rAFA-110 were gathered by scanning densitometry of SDS-PAGE gel analysis. The least-squares fit of the data to the Hill equation gave 0.26 μM for Kd, 1.63 μM for Bmax, and 1.7 for n.

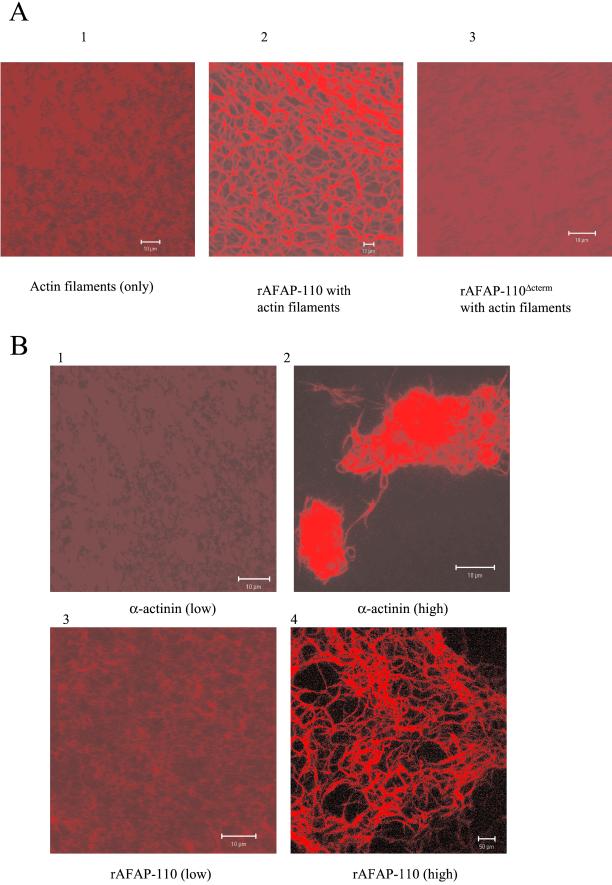

To further test AFAP-110's capability to cross-link actin filaments, we analyzed rhodamine-phalloidin–labeled actin filaments for cross-linking by confocal microscopy. Actin filaments labeled with rhodamine-phalloidin appeared uniformly fluorescent in the absence of an actin binding protein (Figure 3A1). In the presence of 1.3 μM rAFAP-110, actin filaments were organized into a lacy pattern of swollen and interconnected fluorescent tubes (Figure 3A2). Because the varicose pattern was absent when the actin binding-deficient construct rAFAP-110Δcterm were added (Figure 3A3), the confocal fluorescence pattern likely results from actin filament cross-linking. Electron microscopy was used to confirm rAFAP-110's ability to cross-link actin filaments.

Figure 3.

rAFAP-110 cross-links actin filaments. (A) Purified rAFAP-110 or rAFAP-110Δcterm were incubated with rhodamine-phalloidin–labeled actin filaments. After the incubation, the reactions were observed with a Zeiss confocal microscope. 1, actin filaments only; 2, rAFAP-110 with actin filaments; 3, rAFAP-110Δcterm with actin filaments. (B) Confocal microscopy images. Different concentrations of α-actinin (top two panels, low = 0.0625 μM and high = 1.25 μM) and rAFAP-110 (bottom two panels, low = 0.106 μM and high = 2.1 μM) were incubated with rhodamine-phalloidin–labeled actin filaments. After the incubation, the reactions were observed with a Zeiss confocal microscope.

Comparison of Cross-linking by α-Actinin and rAFAP-110

There are two major types of cross-linked actin filament structures: networks and bundles. The networked actin filaments would be predicted to be analogous to a meshwork gel without changing the isotropic nature of actin filaments, while bundled actin filaments are predicted to pack in an anisotropic manner (Wachsstock et al., 1993). Here, we sought to determine how different concentrations of rAFAP-110 affect its ability to cross-link actin filaments. First, two different concentrations of α-actinin were used as controls, because α-actinin has the ability to cross-link actin filaments in a dose-dependent manner, networking actin filaments at low concentrations and bundling actin filaments at high concentrations (Meyer and Aebi, 1990; Wachsstock et al., 1993). Figure 3B demonstrates that low concentrations of α-actinin (0.0625 μM) did not change the organization of actin filaments significantly, whereas high concentration of α-actinin (1.25 μM) caused actin filaments to aggregate (Figure 3, B1 and B2). These data indicate that immunofluorescence confocal microscopy is a reliable technique to analyze changes in actin filament cross-linking and organization. To analyze the effects of AFAP-110 on actin filaments in vitro, analogous concentrations of rAFAP-110 were used and the effects examined by confocal microscope immunofluorescence. The data demonstrate that low concentrations of rAFAP-110 (0.105 μM) did not change the organization of actin filaments, whereas the high concentrations of rAFAP-110 (2.1 μM) caused some aggregation of actin filaments into large branched structures (Figures 3B3 and B4). At low concentration, rAFAP-110 may cross-link actin filaments into isotropic network structures, whereas at high concentrations, rAFAP-110 may cross-link actin filaments into anti-isotropic bundle structures. EM results confirm that rAFAP-110 cross-links actin filaments in a dose-dependent manner. The morphology of actin filaments were unchanged when they were incubated with a low concentration of rAFAP-110, whereas high concentration of rAFAP-110 changed the morphology of actin filaments, as evidenced by an increase in the number of cross-linked actin filaments into fiber structures when examined by electron microscopy.

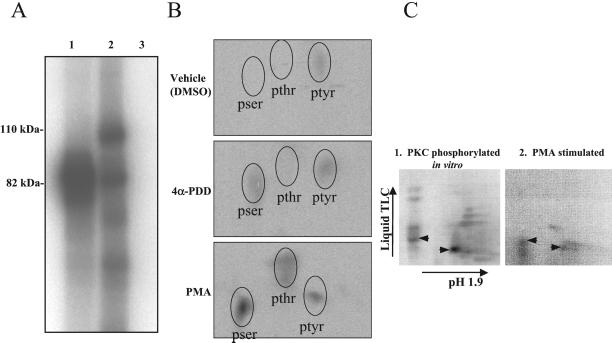

AFAP-110 Is Both a Binding Partner and Substrate of PKCα

Cellular signals directed by Src527F alter the conformation of AFAP-110 and are hypothesized to reduce its capacity to multimerize (Qian et al., 1998), which could affect the ability of AFAP-110 to cross-link actin filaments. Here, we sought to identify a cellular signal that could affect the ability of AFAP-110 to multimerize. Previous data predicted that tyrosine phosphorylation may not be responsible for the change in AFAP-110 conformation in response to Src527F (Qian et al., 1998). Because AFAP-110 is a predicted substrate for PKC phosphorylation (Flynn et al., 1993; Baisden et al., 2001a), PKC is activated in response to Src527F (Spangler et al., 1989) and because PKC activation directs changes in actin filament integrity (Kiley et al., 1992), we sought to determine whether phosphorylation by PKC may affect AFAP-110 function. To test the hypothesis, purified recombinant AFAP-110 was incubated with recombinant PKCα at a molar ratio of 20:1 substrate to enzyme in the presence of radiolabeled ATP. Figure 4A shows that radioactivity was incorporated into rAFAP-110, indicating that it could be phosphorylated by PKCα, in vitro.

Figure 4.

AFAP-110 is a substrate of PKCα. (A) PKCα phosphorylates rAFAP-110 in vitro. rAFAP-110 was incubated with or without recombinant PKCα in the presence of radiolabeled ATP. 1, PKCα (0.5 μg); 2, PKCα (0.5 μg)+rAFAP-110 (10 μg); 3, rAFAP-110 (10 μg). Data are representative of three experiments. (B) AFAP-110 is phosphorylated in vivo in response to PMA treatment. C3H10T1/2 cells were serum starved in phosphate-free media supplemented with radiolabeled 32P-orthophosphate overnight and treated with 100 nM PMA, 100 nM 4α-PDD, or DMSO, the vehicle used. Cells were lysed after 15 min and AFAP-110 was immunoprecipitated using the antibody F1. Radiolabeled AFAP-110 was isolated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to phosphoamino acid analysis. (C) Phosphotryptic analysis reveals common radioactive spots from AFAP-110 phosphorylated by PKC in vitro or phosphorylated in vivo in response to PMA. (C1) A representative tryptic map of rAFAP-110 phosphorylated in vitro by PKCα; (C2) a tryptic map of radio-labeled AFAP-110 purified from Cos-1 cells that were treated with PMA (100 nM, 1 h.). Black arrowheads, radioactive spots common between maps 1 and 2.

To test whether AFAP-110 could be phosphorylated in cells in response to PKC activation in vivo, serum-starved C3H10T1/2 fibroblasts labeled with 32P-orthophosphate were stimulated with 100 nM PMA for 15 min to activate PKC. Phosphoamino acid analysis of AFAP-110 immunoprecipitated from these cells indicates that AFAP-110 was hyperphosphorylated on serine and threonine residues in response to this treatment (Figure 4B). Densitometry of the radioactive spots showed a 5.7-fold increase in phosphothreonine and a 3.9-fold increase in phosphoserine, relative to 4α-PDD treatment. Similar results were also obtained using Cos-1 cells transiently expressing AFAP-110. These data indicate that PMA treatment can induce ser/thr phosphorylation of AFAP-110 in vivo. Additionally, phosphotryptic mapping indicated the presence of similar radioactive spots upon analysis of AFAP-110 phosphorylated in vitro or AFAP-110 purified from PMA-treated Cos-1–expressing cells (Figure 4C). These data do not discriminate between PKC or other activated ser/thr kinases as the enzyme responsible for phosphorylating AFAP-110. However, in agreement with previous predictions (Flynn et al., 1993), these data indicate it is possible that AFAP-110 could represent a potential PKC substrate, in vivo.

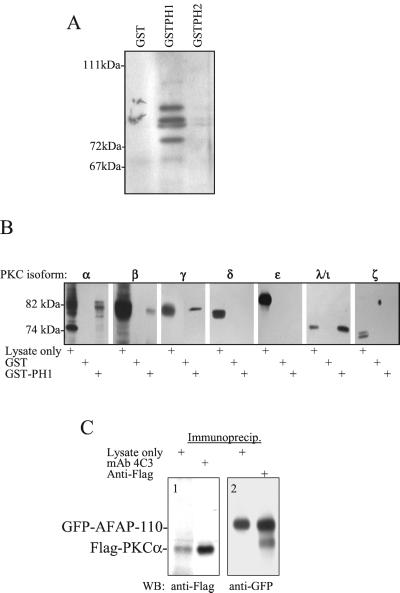

Sequence analysis of both pleckstrin homology (PH) domains of AFAP-110 (Baisden et al., 2001a) revealed highest homology between the amino-terminal PH domain (PH1) and PH domains from β-spectrin and dynamin, which have been shown to forge interactions with PKC (Yao et al., 1997; Rodriguez et al., 1999). The carboxy-terminal PH domain (PH2) was found to share highest homology with the PH domain from Btk, which also directs interactions with PKC (Yao et al., 1997). The amino- and carboxy-terminal PH domains of AFAP-110 were expressed as GST-encoded fusion proteins (GST-PH1 and GST-PH2) and used to affinity-absorb cellular proteins from cell lysates (Figure 5). It was demonstrated that absorbates from both PH domains could affinity-absorb ser/thr kinase activity, based on a colorimetric ser/thr kinase assay designed to detect activated PKC or PKA (Pierce). GST-PH1 appeared to absorb ser/thr kinase activity much more efficiently than GST-PH2. An additional fusion protein used in this study consisted of a deletion mutant of the amino-terminal PH domain (GST-PH1Δ180–226), which lacks consensus sequences associated with binding PKC (Yao et al., 1997), and this fusion protein failed to absorb cellular ser/thr kinase activity. These GST-PH fusion proteins were also used to affinity-absorb from chick brain lysate in order to detect bound PKC. Using an antipan PKC antibody, which is immunoreactive with an epitope common to all PKC family members (Calbiochem), Figure 5A demonstrates that four distinct proteins were affinity-absorbed by GST-PH1 but not by GST-PH2. Additional affinity-absorptions and Western blots were performed using antibodies specific for individual PKC isoforms. Antibodies specific for PKCα, β, γ, and λ/ι isoforms were immunoreactive with proteins affinity-absorbed by GST-PH1, each of which had a Mr equivalent to the known size of these PKC isoforms (Figure 5B). The absorbates were devoid of protein bands immunoreactive with antibodies against PKCδ, ε, and ζ. Thus, the PH1 domain of AFAP-110 exhibits an ability to interact with at least four PKC isoforms. To determine if this interaction could be the result of direct binding, purified rPKCα was used in affinity-absorptions with GST-PH1 domain fusion proteins. It was found that GST-PH1 was able to absorb rPKCα with much higher efficiency than GST-PH2, the GST-PH1Δ180–226 mutant, or the GST protein alone. To determine whether AFAP-110 and PKC could be detected in complex with each other, coimmunoprecipitation experiments were used. Figure 5C demonstrated that Flag-tagged activated PKCα coexpressed with GFP-tagged AFAP-110 will coimmunoprecipitate when using mAb 4C3, which is specific to the avian AFAP-110 construct (Qian et al., 1999). Conversely, GFP-tagged AFAP-110 will coimmunoprecipitate with anti-Flag antibodies that bind to Flag-PKCα. Thus, AFAP-110 has the potential to form a direct interaction with the PKCα isoform.

Figure 5.

AFAP-110 is a binding partner of PKCα. (A) GST-PH1 affinity absorbs α pan-PKC–immunoreactive proteins. Absorptions using fusion proteins as listed were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with a pan-PKC antibody. This blot is representative of three experiments. (B) GST-PH1 affinity-abosorbs the classical PKC isoforms as well as PKCλ. Absorbates from affinity-absorptions using fusion proteins as listed were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with isoform specific PKC antibodies, as listed. Each blot is representative of two experiments. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of AFAP-110 and PKCα. Immunoprecipitation of GFP-AFAP-110 with mAb 4C3 results in the presence of an anti-Flag immunoreactive protein from cells expressing GFP-AFAP-110 and Flag-PKCα. Likewise, an anti-GFP immunoreactive protein is seen in anti-Flag immunoprecipitation from the same lysate, shown in C2.

Either the Deletion of the Leucine Zipper Motif or PKC Phosphorylation Upregulates AFAP-110's Ability to Cross-link Actin Filaments

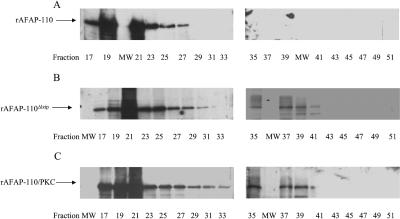

AFAP-110 may cross-link actin filaments through self-association. Therefore, changes in self-association may change AFAP-110's ability to cross-link actin filaments. The deletin of the leucine zipper motif reduces AFAP-110 multimers to dimers in 1% NP-40 buffer (Baisden et al., 2001a), similar to the effects on AFAP-110 in Src527F-transformed cells (Qian et al., 1998). To determine whether interactions with PKC could affect the ability of rAFAP-110 to cross-link actin filaments, gel filtration analysis was applied to determine how deletion of the leucine zipper motif or PKC phosphorylation of rAFAP-110 could affect rAFAP-110's ability to self-associate in vitro, within the context of F-actin binding buffer (Figure 6). The results of FPLC separation by gel filtration show rAFAP-110 has one peak of elution at fraction 21 that corresponds to the molecular weight of 750 kDa (Figure 6A), indicating rAFAP-110 forms large multimeric nonamers in vitro in actin buffer. rAFAP-110Δlzip has two peaks of elution (Figure 6B), one at fraction 21 and the other at fraction 37 (∼250 kDa), indicating that deletion of the leucine zipper motif may destabilize the multimeric AFAP-110Δlzip complex. PKCα phosphorylation of rAFAP-110 also has two peaks of elution (Figure 6C), one at fraction 21 and the other at fraction 37 (∼250 kDa), indicating a change similar to that of AFAP-110Δlzip. The results demonstrate that deletion of the leucine zipper motif or PKCα phosphorylation may destabilize rAFAP-110 multimers, within the context of F-actin binding buffer.

Figure 6.

Either PKC phosphorylation or leucine zipper deletion destabilizes AFAP-110 multmerization. rAFAP-110(A), rAFAP-110Δlzip (B), and rAFAP-110/PKC (C) were separated by gel filtration. Fractions 17–51 were resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE gel. Western blot assays were applied using anti-AFAP-110 F1 antibody. The molecular weight markers were separated by gel filtration using FPLC and eluted as follows: thyglobulin (669 kDa) in fraction 25, ferritin (440 kDa) in fraction 30, catalase (232 kDa) in fraction 37, aldolase (158 kDa) in fraction 39, and albume (67 kDa) in fraction 44.

We next sought to determine whether destabilization of multimer formation may correlate with changes in the ability of rAFAP-110 to cross-link actin filaments. The results of low-speed centrifugation demonstrated that either deletion of the leucine zipper motif or PKCα phosphorylation increased the ability of rAFAP-110 to coprecipitate actin filaments (Figure 7A), indicating that both deletion of the leucine zipper motif or phosphorylation by PKCα induced more extensive F-actin cross-linking capability by AFAP-110. Confocal microscopy of rhodamine-phalloidin–labeled actin filaments in the presence of PKCα phosphorylated rAFAP-110 showed large aggregates of fluorescence (Figure 7B1), similar to the pattern induced by rAFAP-110Δlzip (Figure 7B2) and distinct from the varicose pattern produced by native rAFAP-110 (see Figure 3A). Electron microscopy revealed that both PKCα phosphorylated rAFAP-110, and the leucine zipper deletion mutant induced extensive aggregation of actin filaments.

Figure 7.

Either PKC phosphorylation or leucine zipper deletion increases AFAP-110's ability to cross-link actin filaments. (A) 0.5 μM purified rAFAP-110Δlzip or 0.5 μM PKC phosphorylated rAFAP-110 was incubated with 2 μM actin filaments. After the incubation, the reactions were centrifuged at 20,800 × g. Both supernatants (S) and pellets (P) were applied to SDS-PAGE gel, followed by Coomassie stain. The data are representative of two different experiments. (A1) rAFAP-110; (A2) rAFAP-110Δlzip; (A3) PKC phosphorylated rAFAP-110. (B) Confocal microscopy images. 0.5 μM purified rAFAP-110Δlzip or 0.5 μM PKC phosphorylated rAFAP-110 was incubated with 10% rhodamine-phalloidin–labeled actin filaments (2 μM). After the incubation, the reactions were observed with a Zeiss confocal microscope.

AFAP-110 Mediates the Effects of PKC on the Structural Changes of the Cells

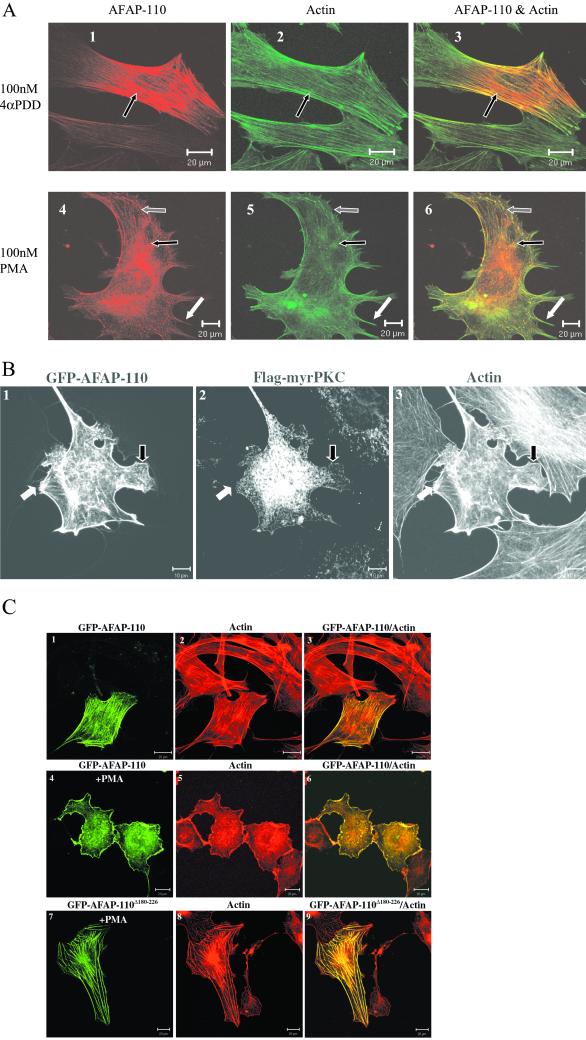

AFAP-110 has been previously demonstrated to exist in dynamic actin structures in response to Src activation (Qian et al., 1998). Figure 8A confirms that AFAP-110 similarly exists in these structures detected in serum-starved fibroblasts upon treatment with PMA, a PKC activator. Lamellipodia, filopodia, and rosettes appear in these cells upon PMA treatment, whereas stress filaments become less apparent. These changes occur within 15 min and largely revert by 2 h after treatment with 100 nM PMA. By 6 h after treatment, the cells have completely reverted to a quiescent phenotype and AFAP-110 retains its localization with actin filaments over this time course. The cells shown represent transient transfections of C3H10T1/2 cells, and similar results are seen with endogenous AFAP-110 in these cells. To further demonstrate the effects of PKCα on AFAP-110, active PKCα was overexpressed in cells. Figure 8B shows that AFAP-110 similarly exists in these structures seen in fibroblasts upon coexpression of active PKCα. GFP-tagged AFAP-110 and Flag-tagged myristoylated PKCα were coexpressed in C3H10T1/2 fibroblasts. Anti-Flag antibodies were used to label Flag-Myr-PKCα (Figure 8B2), and FITC-phalloidin was used to label actin filaments (Figure 8B3). Lamellipodia and filopodia appear in these cells, whereas stress filaments become less apparent. GFP-AFAP-110 is found in motility structures, as designated with white arrows (filopodia) and black arrows (lamellipodia). These results indicate AFAP-110 is properly positioned to play a role in the formation of these structures in cells in response to PKC activation.

Figure 8.

AFAP-110 mediates the effects of PKC on actin filaments. (A) AFAP-110 localizes to dynamic actin structures seen upon PMA stimulation. Immunofluorescence labeling and imaging was carried out as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. C3H10T1/2 cells expressing AFAP-110 were treated with either 100 nM PMA (A1–A3) or 100 nM 4α-PDD (A4–A6) for 15 min after overnight serum starvation. AFAP-110 is represented in red (A1 and A4), whereas actin is represented in green (A2 and A5). (A3 and A6) Overlap images of AFAP-110 and actin. Arrows indicate colocalization of AFAP-110 with dynamic actin structures: white arrows, filopodia; gray arrows, lamellipodia; black arrows, actin filaments in the top panel and disrupted actin filaments/rosettes in the bottom panel. (B) AFAP-110 localizes to lamellipodia/filopodia seen upon expression of active PKC. Immunofluorescence labeling and imaging were carried out as described in Experimental Procedures. C3H10T1/2 cells coexpressing GFP-AFAP-110 (B1) and myristoylated, Flag-tagged PKC were labeled to show Flag-tagged PKC (B2) and actin (B3). Arrows indicate colocalization of AFAP-110 with dynamic actin structures: white arrows label filopodia and black arrows label lamellipodia. (C) AFAP-110 mediates the effects of PKC on the changes of cell structures. Immunofluorescence labeling and imaging were carried out as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. C3H10T1/2 cells were transfected with pCMV-GFP-AFAP-110 (C1–C6) and pCMV-GFP-AFAPΔ180–226 (C7–C9). PMA at 100 nM was used to stimulate the cells for 1 h. C1, C4, and C7; green GFP fusion protein images; C2, C5, and C8; X actin images; C3, C6, and C9, overlap images of GFP fusion protein and actin images.

PKCα has the capability to phosphorylate AFAP-110 and the potential to bind AFAP-110 via its amino terminal PH domain (PH1; see Figure 5). Here, we sought to determine whether deletion of the PH1 domain of AFAP-110 could impede the effects of PMA on changes in actin filament integrity and the formation of motility structures. A deletion mutant of the PH1 domain of AFAP-110, AFAP-110Δ180–226, was subcloned into the pGFP vector. Both pGFP-AFAP-110 and pGFP-AFAP-110Δ180–226 were transiently transfected into C3H10T1/2 cells. GFP-AFAP-110 colocalized with actin filaments and the cell membrane (Figure 8, C1–C3). PMA, a PKC activator, was applied to stimulate these cells. It was found that PMA stimulation of GFP-AFAP-110 cells disrupted the integrity of actin filaments, induced the formation of cell motility structures, and positioned GFP-AFAP-110 into these structures (Figure 8, C4–C6). However, GFP-AFAPΔ180–226 appeared to interfere with the effects of PMA on actin filaments, whereby GFP-AFAPΔ180–226 was evenly localized upon well-formed actin filaments and the cell membrane (Figure 8, C7–C9). There results indicate that AFAP-110 can play a role in mediating the effects of PMA on actin filaments.

DISCUSSION

AFAP-110 binds to actin filaments directly and can self-associate in vivo, which indicated that AFAP-110 could cross-link actin filaments. The results presented here demonstrate that AFAP-110 does have the capability to cross-link actin filaments into both network and bundle structures. Previously, we demonstrated that AFAP-110 overexpressed in Cos-1 cells self-associated to form multimers, as detected in 1% NP-40 buffer cell lysates (Qian et al., 1998). In this report, gel filtration analysis indicated that rAFAP-110 self-associated to form larger complexes within the context of actin binding buffer, predicted to be nonamers (750-kDa complex/82 kDa per monomer). The reason for the different profiles of AFAP-110 self-association may be due to 1% NP-40 buffer environment and/or the environment of the cellular lysates used in previous studies could affect hydrophobic interactions, whereas the actin buffer used in this study may differentially affect this type of interaction. We do not know at this time which profile is physiologically more relevant as the formation of actin filaments into bundle and network structures would be dependent on the stoichiometry of actin cross-linking proteins. The confocal microscopy data demonstrated that there were two different phenotypes of cross-linked actin filaments that coexisted when 0.5 μM concentrations of rAFAP-110 were incubated with 2 μM concentrations of actin filaments, indicating a dose-response effect of rAFAP-110 upon actin filament cross-linking.

The ability of AFAP-110 to be recruited in vivo depends on the concentration of AFAP-110 found in the cell and may correlate with the actin filament binding parameters determined in vitro. The actin concentration in cells is estimated to be ∼200 μM (Blikstad et al., 1978), about half of which is filamentous, and concentration of actin in the leading edge may be as high as 400 μM (Hartwig and Shevlin, 1986). These concentrations of actin are well above the concentration of actin used in our binding assay. Given a total concentration of AFAP-110 in the cell of 0.16 μM (Baisden et al., 2001a), AFAP-110 could occupy 13% of available actin binding sites (Figure 1C). Thus, AFAP-110 could be recruited to the lamellipodium by mass action.

Cooperative binding can be explained by nearest neighbor interactions among multimers of AFAP-110 along the length of the actin filament. This model is favored by the coexistence of fully decorated and bare actin filaments in the same field of negatively stained preparations. The nearest neighbor packing of AFAP-110 would be constrained by the steric volume of the multimer. A reduction in the steric volume of the multimer that accompanies either PKC phosphorylation or amino acid deletion in the leucine zipper domain could increase the packing density and thereby condense the cross-linked structure seen in PKC phosphorylated preparations.

Our results demonstrate that AFAP-110 has an intrinsic capability to promote actin filament cross-linking, which is revealed by deletion of the leucine zipper motif. Deletion of the leucine zipper motif appears to alter the conformation of AFAP-110, enabling it to reposition stress filaments into rosettes and induce the formation of lamellipodia, filopodia and membrane ruffles (Qian et al., 1998 and 2000). Deletion of the leucine zipper motif also appears to destabilize multimeric AFAP-110. Interestingly, these results also demonstrated that PKC phosphorylation upregulated rAFAP-110's capability to cross-link actin filaments in a manner similar to the effects of rAFAP-110Δlzip. AFAP-110 appears smaller on F-actin, based on electron microscopy analysis, when it is either phosphorylated by PKC or when the leucine zipper is deleted. Within the context of actin binding buffer, AFAP-110, PKC-phosphorylated AFAP-110 or AFAP-110Δlzip each separated as an ∼750-kDa multimeric protein. However, a second smaller peak was identified with PKC-phosphorylated AFAP-110 and AFAP-110Δlzip at a MW of 250 kDa. Therefore, we hypothesize that either the process of binding to F-actin or centrifugation of the AFAP-110/F-actin complexes may result in the formation of smaller aggregates of phosphorylated AFAP-110 or AFAP-110Δlzip when bound to actin filaments, which can be visualized by electron microscopy. Therefore, it is possible that interactions with PKC or loss of intramolecular leucine zipper interactions could destabilize AFAP-110 multimers and transition AFAP-110 from a large, loose actin filament cross-linking protein to a smaller, more efficient actin filament cross-linking protein (when bound to F-actin), which would enable it to tightly cross-link actin filaments and possibly promote bundle formation. The formation of cell motility structures is associated with many newly forming actin filaments and actin filament cross-linking (Condeelis, 1993; Roberts and Stewart, 2000). It has been found that the cross-linking of actin filaments is an essential force necessary to protrude the cell membrane forward (Condeelis, 1993), such as the major sperm protein (MSP; Italiano et al., 1996) and the actin filament cross-linking protein ABP-120 (Cox et al., 1995 and 1996). AFAP-110 is evenly distributed along stress filaments, and the cell membrane in the cell body of quiescent cells, but shows relatively high concentrations in cell motility organelles such as lamellipodia, filopodia, and membrane ruffles, upon activation of cellular signals. It is possible that increasing concentrations of AFAP-110 might be recruited to these newly forming actin filaments through cooperative binding and could promote actin filament cross-linking and interconversion between networks and bundles, which may contribute to protrusive force and the formation of cell motility structures.

Activation of PKC in vivo induces the formation of motility organelles such as filopodia, lamellipodia, and membrane ruffles at the leading edge (Dwyer-Nield et al., 1996; Coghlan et al., 2000). Interestingly, AFAP-110Δlzip also promotes a dissolution of stress filaments and the formation of motility structures (Qian et al., 1998, 2000). Recent data indicate that AFAP-110Δlzip can activate cellular tyrosine kinases and cSrc family kinases in an SH3-dependent manner (Baisden et al., 2001b). Therefore, AFAP-110 is also a cSrc-activating protein, and it is possible that upon activation of PKC, AFAP-110 could affect actin filament integrity through two mechanisms: 1) an indirect mechanism that utilizes cSrc signaling pathways to relax stress filaments and 2) a direct mechanism whereby AFAP-110 could contribute to actin filament cross-linking at the cell membrane.

Interestingly, AFAP-110 can also bind PKC via its PH domain and mutants of AFAP-110 that fail to bind PKC and impede the effects of activated PKC upon actin filaments, indicating the in vitro biochemical results may be relevant to in vivo cellular functions of AFAP-110. We do not know whether the effects seen in Figure 8C may be due to the inability of AFAP-110 to bind phospholipid products. Based on structural analysis of the PH domains of AFAP-110, the position of lysine residues predicted to coordinate phospholipid binding indicates that AFAP-110 may have the capability to bind phospholipid products through amino terminal PH domain (Baisden et al.; 2001a). It is noteworthy that although Baisden et al. demonstrated that AFAP-110Δlzip could alter actin filament integrity by activating cSrc family kinases in an SH3-dependent manner, deletion of the PH1 amino acids 180–226 also prevented activation of cSrc kinases by AFPA-110Δlzip (Baisden et al., 2001b). These data indicate that AFAP-110 may facilitate changes in actin filament integrity in response to cellular signals that may permit it to link signaling between PKC and cSrc. The ability of AFAP-110 to both activate cellular signals that direct changes in stress filament bundling and to promote the formation of actin filament cross-linking may answer a paradox of PKC signaling. PKC activation directs a dissolution of actin stress fibers across the cytoplasm, yet directs increases in the formation of cell motility structures at the cell membrane (Dwyer-Nield et al., 1996; Coghlan et al., 2000). It is possible that when PKC is activated and moves to the cell membrane, it interacts with AFAP-110 as well as other substrates. Phosphorylation of substrates such as VASP, Fascin, and MARCKS may facilitate a relaxation of stress filaments, whereas interactions with AFAP-110 may promote actin filament bundling at the cell membrane and the concomitant formation of motility structures. Cooperatively in binding may facilitate AFAP-110–mediated actin filament cross-linking. Although AFAP-110 also exists on stress filaments, it may not promote cross-linking of stress filaments in this environment because activated PKC is targeted to the cell membrane (Dwyer-Nield et al., 1996; Toker, 1998; Coghlan et al., 2000). Here, our report demonstrated that interactions with PKC upregulated AFAP-110's capability to cross-link actin filaments, which is novel and may be more relevant to the formation of motility organelles upon PKC activation. We hypothesize that interactions with activated PKC directly enable AFAP-110 to tightly cross-link actin filaments, which may contribute to the increase of actin filament cross-linking activity in lamellipodia during its growth and the formation of filopodia and membrane ruffles.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant to D.C.F. from the National Cancer Institute (CA60731) and a grant from the American Cancer Society (RPG-99–088-01-MBC). J.M.B. was supported by a fellowship from the West Virginia University Medical Scientist Training Program. J.M.S. was supported by the Arlen G. and Louise Stone Swiger Predoctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E01–12–0148. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E01–12–0148.

REFERENCES

- Baisden JM, Qian Y, Zot HG, Flynn DC. The actin filament associated protein, AFAP-110, is an adaptor protein that modulates changes in actin filament integrity. Oncogene. 2001a;20:6435–6447. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baisden JM, Gatesman AS, Cherezova L, Jiang BH, Flynn DC. The intrinsic ability of AFAP-110 to alter actin filament integrity is linked with its ability to also activate cellular tyrosine kinases. Oncogene. 2001b;20:6607–6616. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blikstad I, Markey F, Carlsson L, Persson T, Lindberg U. Selective assay of monomeric and filamentous actin in cell extracts using inhibition of deoxyribonuclease I. Cell. 1978;55:935–943. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon LY, Zhu H, Shao L, Chen YW. CD44 interaction with c-Src kinase promotes cortactin-mediated cytoskeleton function and hyaluronic acid (HA)-dependent ovarian tumor cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7327–7336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006498200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle WJ, van der Geer P, Hunter T. Phosphopeptide mapping and phosphoamino acid analysis by two-dimensional separation on thin-layer cellulose plates. Methods Enzymol. 1991;201:110–149. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)01013-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubb MR, Lenox RH, Edison AS. Phosphorylation-dependent conformational changes induce a switch in the actin-binding function of MARCKS. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36472–36478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AN. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Vol. 18. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1997. pp. 7.1–18. , 7.22. [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan MP, Chou MM, Carpenter CL. Atypical protein kinases Clambda and -zeta associate with the GTP-binding protein Cdc42 and mediate stress fiber loss. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2880–2889. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2880-2889.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condeelis J. Life at the leading edge: the formation of cell protrusions. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:411–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.002211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JA, Pollard TD. Methods to characterize actin filament networks. Methods Enzymol. 1982;85(Pt B):182–210. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)85022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D, Ridsdale JA, Condeelis J, Hartwig J. Genetic deletion of ABP-120 alters the three-dimensional organization of actin filaments in Dictyostelium pseudopods. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:819–835. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D, Wessels D, Soll DR, Hartwig J, Condeelis J. Re-expression of ABP-120 rescues cytoskeletal, motility, and phagocytosis defects of ABP-120− Dictyostelium mutants. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:803–823. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.5.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer-Nield LD, Miller AC, Neighbors BW, Dinsdale D, Malkinson AM. Cytoskeletal architecture in mouse lung epithelial cells is regulated by protein-kinase C-alpha and calpain II. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:L526–L534. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.4.L526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn DC, Leu TH, Reynolds AB, Parsons JT. Identification and sequence analysis of cDNAs encoding a 110-kilodalton actin filament-associated pp60src substrate. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7892–7900. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guappone AC, Flynn DC. The integrity of the SH3 binding motif of AFAP-110 is required to facilitate tyrosine phosphorylation by, and stable complex formation with, Src. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;175:243–252. doi: 10.1023/a:1006840104666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guappone AC, Weimer T, Flynn DC. Formation of a stable src-AFAP-110 complex through either an amino-terminal or a carboxy-terminal SH2-binding motif. Mol Carcinog. 1998;22:110–119. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199806)22:2<110::aid-mc6>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbeck B, Huttelmaier S, Schluter K, Jockusch BM, Illenberger S. Phosphorylation of the vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein regulates its interaction with actin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30817–30825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig JH, Shevlin P. The architecture of actin filaments and the ultrastructural location of actin-binding protein in the periphery of lung macrophages. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1007–1020. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.3.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig JH, Thelen M, Rosen A, Janmey PA, Nairn AC, Aderem A. MARCKS is an actin filament crosslinking protein regulated by protein kinase C and calcium-calmodulin. Nature. 1992;356:618–622. doi: 10.1038/356618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Ni Y, Wang T, Gao Y, Haudenschild CC, Zhan X. Down-regulation of the filamentous actin cross-linking activity of cortactin by Src-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13911–13915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Liu J, Haudenschild CC, Zhan X. The role of tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin in the locomotion of endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25770–25776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa R, Yamashiro S, Kohama K, Matsumura F. Regulation of actin binding and actin bundling activities of fascin by caldesmon coupled with tropomyosin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26991–26997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Italiano JE, Jr, Roberts TM, Stewart M, Fontana CA. Reconstitution in vitro of the motility apparatus from the amoeboid sperm of Ascaris shows that filament assembly and bundling move membranes. Cell. 1996;84:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner SB, Reynolds AB, Parsons JT. Immunoaffinity purification of tyrosine-phosphorylated cellular proteins. J Immunol Methods. 1989;120:115–124. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90296-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner SB, Reynolds AB, Wang HC, Vines RR, Parsons JT. The SH2 and SH3 domains of pp60src direct stable association with tyrosine phosphorylated proteins p130 and p110. EMBO J. 1991;10:1689–1698. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiley SC, Parker PJ, Fabbro D, Jaken S. Hormone- and phorbol ester-activated protein kinase C isozymes mediate a reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton associated with prolactin secretion in GH4C1 cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:120–131. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.1.1738365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Tombler E, Nelson PJ, Ross M, Gelman IH. A novel src- and ras-suppressed protein kinase C substrate associated with cytoskeletal architecture. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28430–28438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RK, Aebi U. Bundling of actin filaments by alpha-actinin depends on its molecular length. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:2013–2024. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono S, Yamakita Y, Yamashiro S, Matsudaira PT, Gnarra JR, Obinata T, Matsumura F. Identification of an actin binding region and a protein kinase C phosphorylation site on human fascin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2527–2533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard TD, Cooper JA. Methods to characterize actin filament networks. Methods Enzymol. 1982;85(Pt B):211–233. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)85022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Baisden JM, Westin EH, Guappone AC, Koay TC, Flynn DC. Src can regulate carboxy terminal interactions with AFAP-110, which influence self-association, cell localization and actin filament integrity. Oncogene. 1998;16:2185–2195. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Guappone AC, Baisden JM, Hill MW, Summy JM, Flynn DC, Qian Y, Guappone AC, Baisden JM, Hill MW, Summy JM, Flynn DC. Monoclonal antibodies directed against AFAP-110 recognize species-specific and conserved epitopes. Hybridoma. 1999;18:167–175. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1999.18.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Baisden JM, Zot HG, Van Winkle WB, Flynn DC. The carboxy terminus of AFAP-110 modulates direct interactions with actin filaments and regulates its ability to alter actin filament integrity and induce lamellipodia formation. Exp Cell Res. 2000;255:102–113. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TM, Stewart M. Acting like actin. The dynamics of the nematode major sperm protein (msp) cytoskeleton indicate a push-pull mechanism for amoeboid cell motility. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:7–12. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MM, Ron D, Touhara K, Chen CH, Mochly-Rosen D. RACK1, a protein kinase C anchoring protein, coordinates the binding of activated protein kinase C and select pleckstrin homology domains in vitro. Biochemistry. 1999;38:13787–13794. doi: 10.1021/bi991055k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybakova IN, Amann KJ, Ervasti JM. A new model for the interaction of dystrophin with F-actin. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:661–672. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler R, Joseph C, Qureshi SA, Berg KL, Foster DA. Evidence that v-src and v-fps gene products use a protein kinase C-mediated pathway to induce expression of a transformation-related gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7017–7021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toker A. Signaling through protein kinase C. Front Biosci. 1998;3:d1134–d1147. doi: 10.2741/a350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachsstock DH, Schwartz WH, Pollard TD. Affinity of alpha-actinin for actin determines the structure and mechanical properties of actin filament gels. Biophys J. 1993;65:205–214. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81059-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakita Y, Ono S, Matsumura F, Yamashiro S. Phosphorylation of human fascin inhibits its actin binding and bundling activities. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12632–12638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L, Suzuki H, Ozawa K, Deng J, Lehel C, Fukamachi H, Anderson WB, Kawakami Y, Kawakami T. Interactions between protein kinase C and pleckstrin homology domains. Inhibition by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13033–13039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]