Abstract

Objectives

Subclinical myocardial involvement is common in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but differences between new onset and longstanding SLE are not fully elucidated. This study compared myocardial involvement in new onset versus longstanding SLE using cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR).

Materials and methods

We prospectively enrolled 24 drug-naïve new onset SLE patients, 27 longstanding SLE patients, and 20 healthy controls. All participants underwent clinical evaluation and CMR examination. We analyzed left ventricular (LV) morphological, functional parameters, and tissue characterization parameters: native T1, T2, extracellular volume fraction (ECV), and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE).

Results

Both new onset and longstanding SLE groups showed elevated native T1, T2, and ECV values compared to the control group (all P < 0.05). Additionally, the new onset SLE group exhibited higher T2 values compared to the longstanding SLE group [55.3 vs. 52.8 ms, P < 0.05]. The new onset group also demonstrated higher left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic volume index (LVEDVi), LV end-systolic volume index (LVSVi), and LV mass index (LVMi) than controls (all P < 0.05), with LVEDVi significantly higher than in the longstanding group (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

CMR tissue characterization imaging can detect early myocardial involvement in patients with new onset and longstanding SLE. Patients with new onset SLE exhibit more pronounced myocardial edema than those with longstanding SLE. This suggests that SLE patients are at risk of myocardial damage at various stages of the disease, underscoring the need for early monitoring and long-term management to prevent the progression of myocardial remodeling.

Keywords: new onset SLE, longstanding SLE, myocardial involvement, cardiovascular magnetic resonance

Highlight

-

•

Cardiac MR can detect early myocardial involvement in new onset and longstanding SLE.

-

•

Differences in myocardial involvement exist between new onset and longstanding SLE.

-

•

New onset SLE shows pronounced myocardial edema compared to longstanding SLE.

1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic autoimmune disease with the potential to involve multiple organs, including the heart [1]. Cardiac involvement is common in SLE patients and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [2]. The pathogenesis of myocardial involvement in SLE is multifaceted, encompassing immune complex deposition, complement activation, microvascular injury, and reparative fibrosis [1], [2], [3]. Clinical manifestations can vary from asymptomatic subclinical disease to acute heart failure, with the latter often signaling a poor prognosis [4]. Thus, early detection of myocardial injury in SLE patients is pivotal for prompt intervention.

Traditional assessment methods like laboratory tests, electrocardiography (ECG), and echocardiography demonstrate limited sensitivity in identifying subclinical cardiac impairment [5]. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR), with its multi-sequence and multi-parameter capabilities, facilitates a thorough assessment of cardiac morphology, function and myocardial tissue characteristics, providing invaluable information in evaluating cardiac involvement in SLE [6], [7], [8]. While numerous studies have utilized CMR to affirm the pervasive presence of subclinical myocardial involvement in SLE patients [9], [10], [11], research employing CMR to compare cardiac involvement between drug-naïve new onset and longstanding SLE patients is relatively scarce. Comparing myocardial involvement characteristics at different disease stages can illuminate the mechanisms of myocardial damage in SLE, evaluate treatment efficacy, guide personalized therapy, and offer insights into the prevention and management of myocardial involvement in SLE. In this study, we aim to explore the differences in cardiac impairment between drug-naïve new onset SLE patients and those with a more extended disease duration, utilizing multi-parametric CMR imaging, including T1/T2 mapping and extracellular volume fraction (ECV) quantification.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

This prospective study recruited consecutive patients diagnosed with SLE at the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University from August 2020 to April 2023. The inclusion criteria were: (1) a confirmed diagnosis of SLE according to the 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology (EULAR/ACR) classification criteria for SLE [12]; (2) patients who underwent CMR examination. Exclusion criteria for participants were as follows: (1) age < 18 years; (2) patients with concomitant conditions including coronary artery disease (confirmed by coronary artery computed tomography angiography or coronary angiography), congenital heart disease, hypertensive heart disease, and significant valvular disease; (3) a treatment duration ≤ 6 months at the time of the CMR examination; (4) patients with poor CMR image quality; The disease course of SLE patients is defined as the period between the confirmed diagnosis of SLE and the performance of CMR examination. The recruited patients were divided into the following two groups: new onset SLE patients and longstanding SLE patients. New onset SLE was defined as patients who were newly diagnosed within one month prior to the CMR examination and had not received any SLE-related medication. Longstanding SLE referred to patients with an ongoing treatment period of more than six months at the time of the CMR examination. In addition, healthy controls matched by age, sex and body mass index (BMI) were recruited. They all had no history of cardiac disease or any hospitalization. The study was approved by local ethics committee and all subjects gave written informed consent prior to participating in the study.

2.2. Clinical data and immunological assessment

Comprehensive demographic data, laboratory evaluations, and treatment details of the patients were meticulously documented in standardized case report forms. Laboratory assessments encompassed markers indicative of myocardial cell injury (e.g., creatine kinase, creatine kinase-MB, B-type natriuretic peptide, cardiac troponin I) and serum markers pertinent to rheumatic disease (e.g., antinuclear antibodies, anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies), alongside markers reflective of inflammation and immune response (e.g., high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, complement levels, IgG, IgM). The duration, clinical features and measures of disease activity (SLE disease activity index [SLEDAI-2K]) [13] of SLE patients were assessed and recorded by experienced rheumatologists, who were blinded to the CMR results. Disease activity was graded based on EULAR [14] criteria: SLEDAI-2K ≤ 6 for mild activity, 7–12 for moderate, and > 12 for severe. Subjects underwent standard ECG within 24 hours before CMR.

2.3. CMR protocol

CMR was performed on a 1.5 T whole-body MRI system (Ingenia, Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) using a 32-element body array coil. Balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) sequences were used for cardiac cine imaging. Continuous short-axis cine images of 8–10 slices, long-axis two-chamber, three-chamber and four-chamber were acquired. The scanning parameters were as follows: FOV 300 mm × 300 mm, TR 3.4 ms, TE 1.68 ms, flip angle 60°, slice thickness 8 mm, slice gap 8 mm, matrix size 176 × 166. Modified look-locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) sequences were used to acquire T1 mapping images of the left ventricular (LV) short-axis views (basal, mid and apical) before contrast enhancement (native T1). The scanning parameters were as follows: FOV 300 mm × 300 mm, TR 3.0 ms, TE 1.4 ms, flip angle 35°, slice thickness 7 mm, slice gap 14 mm, matrix size 152 × 150. Gradient-spin echo sequences were used to acquire T2 mapping images of the LV short-axis views (basal, mid and apical). The scanning parameters were as follows: FOV 300 mm × 300 mm, fixed TR 650 ms, echo spacing 9.3 ms, echo train length 9, flip angle 90°, slice thickness 7 mm, slice gap 14 mm, matrix size 152 × 150. 8 minutes after injection of gadopentetate dimeglumine, LV short-axis (8–10 slices) and long-axis two-chamber, three-chamber and four-chamber late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) images were acquired using the phase-sensitive inversion recovery sequence. The scanning parameters were as follows: FOV 300 mm × 300 mm, TR 6 ms, TE 3 ms, flip angle 25°, slice thickness 8 mm, slice gap 8 mm, matrix size 188 × 152. Approximately 15 minutes after the injection of gadopentetate dimeglumine (0.2 mmol/kg), post -contrast T1 mapping images were acquired with the same parameters as native T1 mapping.

2.4. CMR analysis

The post-processing of all CMR images was performed by two radiologists (Z.W. and J.Y., both with 2 years' experience in the evaluation of CMR) using CVI42 (Version 5.14.2, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc., Calgary, Canada). Both radiologists independently analyzed the same set of images to quantify the parameters. Any differences between the two observers were adjudicated by a senior observer (X.L., with 15 years’ experience in CMR). Automated delineation of the LV endocardial and epicardial contours (excluding papillary muscle) was conducted at both systole and diastole endpoints within the cine images (with manual adjustment if necessary). Subsequently, automatic calculations were executed, leading to the generation of cardiac functional parameters. CMR two-dimensional global peak LV strain using feature tracking was assessed as previously described [15].

The location and pattern of LGE lesions were evaluated by manually adjusting the endocardial and epicardial contours that automatically delineate the myocardium on LGE images. LGE lesions were defined as signal intensity greater than 5 standard deviations above the remote reference myocardial average signal intensity.

The native T1 maps, post-contrast T1 maps, and T2 maps were automatically generated by importing the original T1 images and T2 images into the corresponding analysis module. Venous blood samples were taken within 24 hours before CMR examination, and the hematocrit level of all subjects was measured. The CMR-derived ECV was calculated using the methods described previously [16]. The calculation formula was as follows:

where ΔR1myo represents the change in the reciprocal of the T1 value of myocardial tissue before and after contrast, and ΔR1blood is the change in the reciprocal of the T1 value of blood. Native T1 maps, T2 maps, and ECV maps were analyzed using the 16 segments model using the classic AHA guide [17] of the LV (excluding the apical segment). To determine reference values for assessing myocardial involvement, we set the upper limits for native T1, T2, and ECV values based on data from healthy controls, using the mean + 2 standard deviations (SD) as the threshold for normal values, as referenced in Feng et al. [18]. Myocardial involvement was considered present if any of the T1, T2, or ECV values exceeded these upper limits.

2.5. Intra- and interobserver reproducibility

Intra- and inter-observer reproducibility of native T1, T2, and ECV values was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). Intra-observer reliability was assessed from repeated measurements made by one radiologist blinded to previous results of 20 random subjects obtained at least 1 week later. Inter-observer reliability was independently assessed on the data of 20 subjects by another radiologist blinded to the first radiologist's measurements. Inter-observer reproducibility for LGE was evaluated using Cohen’s kappa statistic.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 26.0, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism (version 9.0, GraphPad Inc., USA). Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages, and continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median and interquartile range. The normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons among the three groups were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni-corrected post hoc comparisons for normally distributed data, or Kruskal-Wallis tests with post hoc pairwise comparisons for non-normally distributed data. For comparisons specifically between new onset and longstanding SLE, we performed an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with treatment duration included as a covariate to control for heterogeneity in treatment duration within the longstanding SLE group. All reported comparisons between new onset and longstanding SLE parameters are adjusted for treatment duration. For subgroup analysis, the independent t-test was used for normally distributed data, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed data to compare differences between the normal ECG and abnormal ECG subgroups. Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was employed to compare differences between qualitative data. The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to assess reproducibility. All tests were two-tailed, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

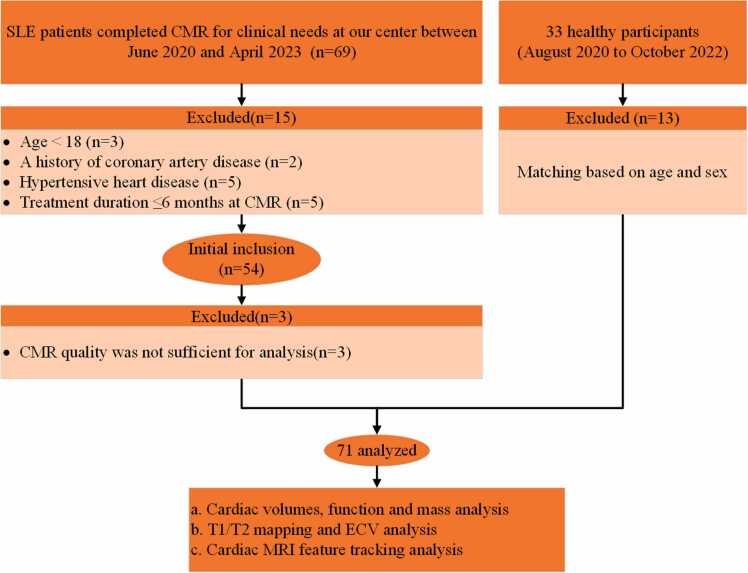

The flowchart of participants is presented in Fig. 1. The final analysis cohort comprised 51 patients and 20 controls. The SLE cohort included 24 new onset patients and 27 longstanding patients. Predominantly, the patients exhibited mild to moderate disease activity (SLE activity: 42 % mild, 50 % moderate, and 8 % severe in new onset SLE; 56 % mild, 41 % moderate, and 4 % severe in longstanding SLE). Clinical characteristics and laboratory results for SLE patients are presented in Table 1. Compared to controls, patients with longstanding SLE exhibited significantly higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures, albeit still within normal range (P < 0.05). The longstanding SLE group had been treated primarily with methylprednisolone, hydroxychloroquine, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participant enrollment. CMR = cardiovascular magnetic resonance; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants.

| New Onset, n = 24 | Longstanding, n = 27 | Control, n = 20 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31 (22, 42) | 40 (32, 51) | 34 (23, 46) | 0.06 |

| Females | 21 (21/24; 88) | 25 (25/27; 93) | 17 (17/20; 85) | 0.67 |

| BSA (m2) | 1.60 (1.49, 1.62) | 1.61 (1.47, 1.74) | 1.63 (1.53, 1.67) | 0.42 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.8 (19.5, 22.7) | 23.31 (20.9, 25.0) | 22.37 (19.95,23.44) | 0.13 |

| BP systolic (mmHg) | 118 (106, 127) | 128 (112, 137) † | 111 (94, 125) | 0.01 |

| BP diastolic (mmHg) | 76 (63, 82) | 80 (74, 86) † | 74 (66, 76) | 0.02 |

| Disease duration (months) | 0.61 (0.33, 0.93) | 60.00 (36.00, 168.00) | – | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0 (0/24; 0) | 0 (0/27; 0) | 0 (0/20; 0) | NA |

| Diabetes | 0 (0/24; 0) | 1 (1/27; 4) | 0 (0/20; 0) | >0.99 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0 (0/24; 0) | 0 (0/27; 0) | 0 (0/20; 0) | NA |

| Smoking | 0 (0/24; 0) | 0 (0/27; 0) | 0 (0/20; 0) | NA |

| NYHA III class | 0 (0/24; 0) | 2 (2/27; 7) | 0 (0/20; 0) | 0.33 |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||

| Cardiac symptoms # | 5 (5/24; 21) | 2 (2/27; 7) | – | 0.33 |

| Fever | 5 (5/24; 21) | 3 (3/27; 11) | – | 0.57 |

| Arthritis | 6 (6/24; 25) | 3 (3/27; 11) | – | 0.35 |

| Facial erythema | 2 (2/24; 8) | 7 (7/27; 26) | – | 0.20 |

| Rash | 2 (2/24; 8) | 6 (6/27; 22) | – | 0.33 |

| Abnormal ECG | 13 (13/24; 54) | 15 (15/27; 56) | – | 0.92 |

| SLE activity | ||||

| SLEDAI-2K ≤ 6 | 10 (10/24; 42) | 15 (15/27; 56) | – | 0.48 |

| SLEDAI-2K 7–12 | 12 (12/24; 50) | 11 (11/27; 41) | – | 0.51 |

| SLEDAI-2K > 12 | 2 (2/24; 8) | 1 (1/27; 4) | – | 0.92 |

| Laboratory measurements | ||||

| Abnormal CK | 12 (12/24; 50) | 9 (9/27; 33) | – | 0.23 |

| Abnormal CM-MB | 2 (2/24; 8) | 3 (3/27; 11) | – | >0.99 |

| Abnormal BNP | 3(3/24; 13) | 7(7/27; 26) | – | 0.39 |

| Abnormal cTNI | 1 (1/24; 4) | 1 (1/27; 4) | – | >0.99 |

| Abnormal ESR | 17(17/24; 71) | 16(16/27; 59) | – | 0.39 |

| Abnormal hs-CRP | 6(6/24; 25) | 2(2/27; 7) | – | 0.18 |

| Abnormal C3 | 19(19/24; 79) | 18(18/27; 67) | – | 0.32 |

| Abnormal C4 | 18(18/24; 75) | 12(12/27; 44) | – | 0.03 |

| Abnormal IgG | 15(15/24; 63) | 8(8/27; 30) | – | 0.02 |

| Abnormal IgM | 6(6/24; 25) | 8(8/27; 30) | – | 0.71 |

| Positive ANA | 23 (23/24; 96) | 25 (25/27; 93) | – | >0.99 |

| Abnormal Anti-dsDNA antibody | 19(19/24; 79) | 12(12/27; 44) | – | 0.01 |

| Concurrent SLE-related medicine | ||||

| Methylprednisolone | 0 (0/24; 0) | 20 (20/27; 74) | – | <0.001 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 0 (0/24; 0) | 19 (19/27; 70) | – | <0.001 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 0 (0/24; 0) | 6 (6/27; 22) | – | 0.01 |

Quantitative variables are expressed as medians followed by first and third quartiles in parentheses (Q1, Q3). Qualitative variables are expressed as raw numbers; numbers in parentheses are proportions followed by percentages. †P < 0.05 versus controls; ‡ P < 0.05 versus patients with longstanding systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). # symptoms refer to chest discomfort, chest pain or short of breath. IQR: interquartile range; BP: blood pressure; BMI: body mass index; BSA: body surface area; ECG: electrocardiogram; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI-2K: systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; hs-CRP: high-sensitive C reactive protein; C3: complement 3; C4: complement 4; ANA: antinuclear antibody; IgG: immunoglobulin G; IgM: immunoglobulin M.

3.2. CMR measurements

Cardiac morphologic and functional parameters are summarized in Table 2. LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volume indices (LVEDVi, LVESVi) and LV mass index (LVMi) were significantly higher in new onset SLE patients compared to controls. Among morphological and functional parameters, only LVEDVi differed significantly between controls and patients with longstanding SLE. Notably, LVEDVi was substantially elevated in new onset compared to longstanding SLE (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

MR parameters of SLE patients.

| Variables | New Onset, n = 24 | Longstanding, n = 27 | Control, n = 20 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF (%) | 63.8 (57.9, 65.6) | 61.9 (58.0, 67.5) | 63.9 (59.2, 66.5) | 0.95 |

| LVESVi (mL/m2) | 30.5 (26.6, 36.8) | 28.5 (22.6, 35.2) | 28.4 (23.5, 31.6) | 0.10 |

| LVEDVi (mL/m2) | 85.3 (75.3, 92.1) †‡ | 74.6 (65.9, 80.8) † | 72.1 (68.1, 83.2) | 0.008 |

| CI (L/min/m2)* | 3.63 ± 0.62 | 3.27 ± 0.69 | 3.33 ± 0.74 | 0.17 |

| LVSVi (mL/m2) | 52.5 (45.8, 58.8) † | 46.2 (42.2, 53.9) | 44.5 (40.8, 50.8) | 0.02 |

| LVMi (g/m2) | 48.3 (41.3, 54.7) † | 42.0 (39.0, 46.1) | 40.2 (35.7, 44.7) | 0.005 |

| LVMWT (mm) | 8.3 (7.1, 9.6) | 9.0 (8.2, 9.4) | 7.7 (7.0, 9.1) | 0.05 |

| GRS (%)* | 30.5 ± 5.8 | 33.9 ± 7.6 | 37.2 ± 6.0 | 0.19 |

| GCS (%) | −17.9 (−19.6, −15.9) | −19.6 (−21.0, −18.0) | −18.8 (−19.9, −17.8) | 0.07 |

| GLS (%)* | −16.4 ± 3.6 | −17.3 ± 3.5 | −18.0 ± 3.6 | 0.23 |

| Native T1 (ms) | 1108.3 (1082.9, 1142.2) † | 1100.8 (1066.4, 1145.9) † | 1052.6 (1028.9, 1073.9) | <0.001 |

| Prolonged T1 | 11 (11/24; 46) | 11 (11/27; 41) | – | 0.71 |

| T2 (ms)* | 56.0 ± 3.4 †‡ | 53.1 ± 2.8 † | 51.4 ± 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Prolonged T2 | 15 (15/24; 63) | 9 (9/27; 33) | – | 0.04 |

| ECV (%) | 34.1 (30.2, 35.9) † | 33.4 (30.5, 34.9) † | 25.4 (24.8, 26.6) | <0.001 |

| Prolonged ECV | 23 (23/24; 96) | 25 (25/27; 93) | – | >0.99 |

| Positive LGE | 1 (1/24; 4) | 1 (1/27; 4) | – | 0.14 |

Quantitative variables are expressed as medians followed by first and third quartiles in parentheses (Q1, Q3) or * means ± standard deviations followed by ranges in brackets. Qualitative variables are expressed as raw numbers; numbers in parentheses are proportions followed by percentages. †P < 0.05 versus controls; ‡ P < 0.05 versus patients with longstanding systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). IQR: interquartile range; EF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVi: left ventricular end-systolic volume index; LVEDVi: left ventricular end-diastolic volume index; CI: cardiac output index; LVSVi: left ventricular stroke volume index; LVMi: left ventricular mass index; LVMWT: left ventricular maximal wall thickness; GCS: global circumferential strain; GLS: global longitudinal strain; GRS: global radial strain; ECV: extracellular volume fraction; LGE: late gadolinium enhancement.

Additionally, only two LGE-positive patients were observed (one new onset, one longstanding), and both cases exhibited a midwall linear enhancement pattern in the interventricular septum.

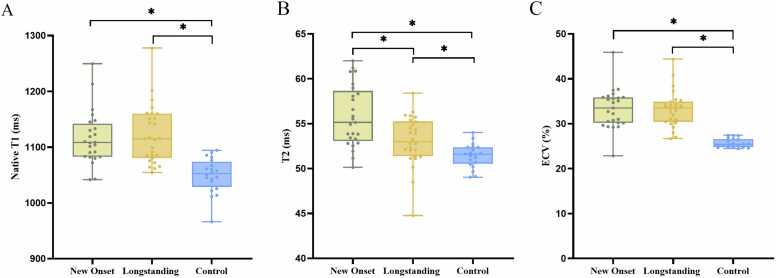

Native T1, ECV, and T2 mapping values were elevated in both new onset and longstanding SLE groups compared to controls (all P < 0.001). Specifically, 46 % of new onset SLE patients and 41 % of longstanding SLE patients exhibited prolonged T1 values. Additionally, 63 % of new onset SLE patients and 33 % of longstanding SLE patients displayed elevated T2 values. Furthermore, 96 % of new onset SLE patients and 93 % of longstanding SLE patients had prolonged ECV values. No significant differences were present in native T1 or ECV between new onset and longstanding SLE (P > 0.05). However, new onset SLE patients exhibited significantly higher T2 values than those with longstanding patients (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Moreover, no significant between-group differences were observed for global radial, circumferential, and longitudinal strain (GRS, GCS, GLS) (P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Box plots showing T1, T2, and extracellular volume fraction (ECV) by group. A, T1 is increased in SLE patients vs. controls. B, T2 is increased in SLE patients vs. controls, and differs between new onset and longstanding SLE. C, ECV is increased in SLE patients vs. controls.

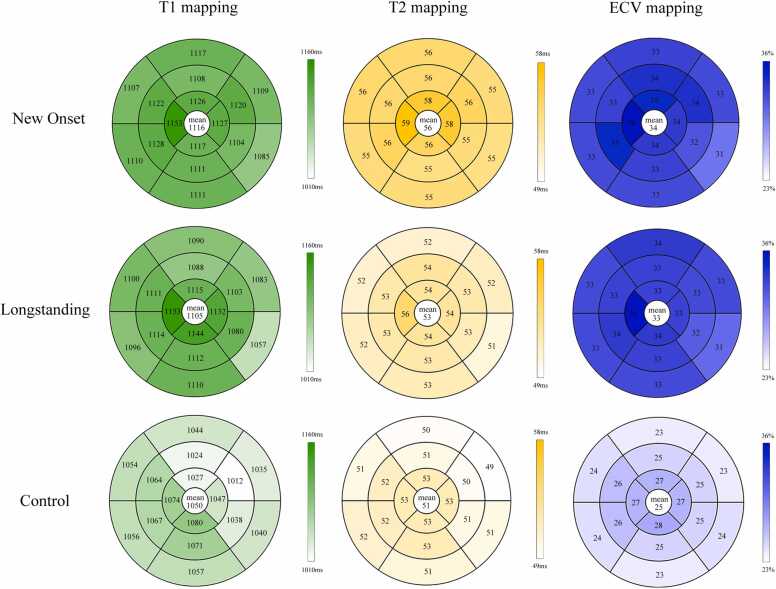

3.3. Segmental analysis

Segmental analysis revealed no significant differences in native T1 and ECV values between new onset and longstanding SLE across 16 myocardial segments (without the apex). However, T2 mapping showed significantly higher segmental values in new onset compared to longstanding SLE. Moreover, the interventricular septum displayed slightly more severe involvement than other segments (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Bull’s eye plots comparing the native T1、T2 and the ECV values of participants. Segmentation was performed according to the AHA 16-segment model in three short-axis slices. Darker colors indicate higher segment values. The average across all segments is given in the centre of the bull’s eye. AHA = American Heart Association; ECV = extracellular volume fraction.

3.4. Subgroup analysis

Abnormal ECGs were observed in 13 of 24 new onset SLE patients (54 %) and 15 of 28 longstanding SLE patients (54 %) (Table 1). The ECG abnormalities primarily manifested as ST-T changes, premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), and atrioventricular conduction delays. Subgroup analysis revealed significantly elevated native T1 values in SLE patients with abnormal ECGs, for both new onset and longstanding SLE groups (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Electrocardiogram results and magnetic resonance parameters.

| New Onset, n = 24 | Abnormal ECG, n = 11 | Normal ECG, n = 13 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF (%) | 62.4 (56.5, 64.2) | 65.4 (63.3, 66.7) | 0.04 |

| LVESVi (mL/m2) | 83.4 (76.9, 100.3) | 84.7 (72.7, 91.4) | 0.12 |

| LVEDVi (mL/m2) | 36.3 (26.8, 39.6) | 29.7(24.6, 34.0) | 0.54 |

| CI (L/min/m2)* | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 0.65 |

| LVSVi (mL/m2) | 50.4 (44.4, 56.6) | 56.2 (45.1, 59.1) | 0.50 |

| LVMi (g/m2) | 49.1 (41.8, 61.1) | 43.6 (39.0, 50.0) | 0.13 |

| LVMWT (mm) | 9.5 (8.1, 10.3) | 7.9 (7.0, 8.9) | 0.04 |

| GRS (%)* | 28.9 ± 6.6 | 31.8 ± 4.9 | 0.23 |

| GCS (%) | −17.6 (−19.3, −15.7) | −18.4 (−19.8, −16.9) | 0.49 |

| GLS (%)* | −15.7 ± 3.5 | −16.9 ± 3.7 | 0.46 |

| Native T1 (ms) | 1133.4 (1087.3, 1153.5) | 1090.4 (1062.1, 1099.9) | 0.006 |

| Prolonged T1 | 8 (8/11; 73) | 3 (3/13; 23) | 0.02 |

| T2 (ms)* | 55.4 ± 3.7 | 55.8 ± 4.6 | 0.80 |

| Prolonged T2 | 5 (5/11; 46) | 9 (9/13; 69) | 0.45 |

| ECV (%) | 35.4 (31.0, 35.9) | 32.7 (29.8, 36.1) | 0.42 |

| Prolonged ECV | 11 (11/11; 100) | 12 (12/13; 92) | >0.99 |

| Longstanding, n = 27 | Abnormal ECG, n = 12 | Normal ECG, n = 15 | |

| LVEF (%) | 63.3 (58.2,67.7) | 61.1 (57.8,67.3) | 0.55 |

| LVESVi (mL/m2) | 27.2 (23.2, 35.8) | 29.8 (22.1, 35.9) | 0.65 |

| LVEDVi (mL/m2) | 75.4 (65.1, 80.5) | 75.1(69.0, 89.0) | 0.58 |

| CI (L/min/m2)* | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 0.86 |

| LVSVi (mL/m2) | 45.5 (42.6, 52.7) | 51(42.3, 53.9) | 0.61 |

| LVMi (g/m2) | 41.3 (38.3, 45.6) | 44.4 (39.0, 47.7) | 0.52 |

| LVMWT (mm) | 9.3 (9.0, 10.5) | 8.3 (7.9, 9.1) | 0.02 |

| GRS (%)* | 35.4 ± 9.9 | 32.7 ± 5.3 | 0.37 |

| GCS (%) | −20.1 (−22.6, −17.1) | −19.4 (−20.2, −18.0) | 0.66 |

| GLS (%)* | −17.1 ± 3.5 | −17.4 ± 3.5 | 0.81 |

| Native T1 (ms) | 1128.7(1089.9,1154.4) | 1071.5 (1054.3, 1140.2) | 0.03 |

| Prolonged T1 | 7 (7/12; 58) | 4 (4/15; 27) | 0.20 |

| T2 (ms)* | 53.4 ± 4.3 | 53.6 ± 2.9 | 0.94 |

| Prolonged T2 | 6 (6/12; 50) | 5 (5/15; 33) | 0.63 |

| ECV (%) | 34.0 (32.1, 36.6) | 31.1 (29.2, 34.9) | 0.10 |

| Prolonged ECV | 12 (12/12; 100) | 13 (13/15; 87) | 0.49 |

Quantitative variables are expressed as medians followed by first and third quartiles in parentheses (Q1, Q3) or * means ± standard deviations followed by ranges in brackets. Qualitative variables are expressed as raw numbers; numbers in parentheses are proportions followed by percentages. IQR: interquartile range; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVi: left ventricular end-systolic volume index; LVEDVi: left ventricular end-diastolic volume index; CI: cardiac output index; LVSVi: left ventricular stroke volume index; LVMi: left ventricular mass index; LVMWT: left ventricular maximal wall thickness; GCS: global circumferential strain; GLS: global longitudinal strain; GRS: global radial strain; ECV: extracellular volume fraction; LGE: late gadolinium enhancement.

3.5. Intra- and interobserver reliability

Intra- and inter-observer reproducibility of native T1, T2, and ECV values were excellent. Intra-observer ICCs for native T1, T2, and ECV were 0.93 (95 % CI: 0.85–0.97), 0.92 (95 % CI: 0.81–0.96), and 0.96 (95 % CI: 0.91–0.98), respectively. Inter-observer ICCs were 0.91 (95 % CI: 0.86–0.95) for native T1, 0.89 (95 % CI: 0.84–0.93) for T2, and 0.94 (95 % CI: 0.89–0.97) for ECV. The inter-observer reproducibility for LGE cine was robust (κ = 0.79).

4. Discussion

This study suggests the value of CMR tissue characterization imaging by detecting myocardial involvement characteristics in new onset and longstanding SLE patients. Our main findings are as follows: Firstly, native T1, T2, and ECV values were elevated in both new onset and longstanding SLE patients compared to controls. Secondly, longstanding SLE patients exhibited reduced myocardial edema compared to new onset SLE patients. Finally, a subgroup of SLE patients with abnormal electrocardiograms showed more severe signs of cardiac involvement.

Cardiac involvement in SLE patients is prevalent, and it does not necessarily correlate with symptoms or markers of systemic disease [19]. Significant LVEF impairment typically occurs in late stages, and early identification of myocardial involvement can help tailor treatment plans to prevent high cardiovascular morbidity and premature mortality [20]. While numerous studies have affirmed that early myocardial damage in SLE patients can be detected by measuring CMR-based native T1, T2, and ECV values [11], [19], consensus is lacking regarding the disparities in cardiac involvement between new onset and longstanding SLE patients. Moreover, the role of quantitative tissue mapping techniques in monitoring anti-inflammatory treatment responses requires further exploration. Direct and quantifiable myocardial tissue characterization through T1, T2, and ECV mapping provides a reliable approach for disease identification and assessment of myocardial inflammation activity, aiding in personalized treatment guidance.

Consistent with previous studies in SLE patients [11], [21], [22], we observed that native T1, T2, and ECV values of myocardium can reflect abnormal myocardial tissue characteristics even when overall function remains within the normal range. In addition, we also noted reduced myocardial edema in longstanding SLE patients compared to new onset SLE patients. Previous MRI studies on myocardial involvement in SLE have primarily focused on the T2 signal intensity ratio between myocardium and adjacent skeletal muscle on T2WI images, known as the T2 edema ratio, often using a ratio > 2 as the threshold for myocardial edema [6], [23], [24]. Guo et al. [11] used the T2 edema ratio and found similar positive percentages in new onset and longstanding treated SLE patients. In contrast, our study used T2 quantification imaging techniques, specifically T2 mapping, and found that new onset SLE patients had more severe myocardial edema. This discrepancy may be because the T2 edema ratio is based on the assumption of normal skeletal muscle signals and may not be applicable to systemic inflammatory diseases like SLE [22]. Furthermore, limitations of T2WI assessment include subjective evaluation, myocardial artifacts in the presence of arrhythmias, and high signal interference from slow/stagnant blood flow in the ventricular cavity [22]. These reasons may account for the differences in our results compared to those of Guo et al. [11]. Recently, Pamuk et al. [25] reported a case of an SLE patient who had developed cardiac symptoms. The baseline CMR examination showed normal global and regional left ventricular contractile function, but abnormal elevation in local T2 values, indicating regional myocardial edema. Two months after treatment, a repeat CMR showed a reduction in myocardial edema, and there were no longer any cardiovascular symptoms. Similarly, in this study, we observed not only a statistically significant decrease in T2 values in the longstanding SLE group compared to the new onset SLE patients, but also a reduced proportion of abnormal T2 values, suggesting that anti-inflammatory treatment may have alleviated myocardial edema.

We found that native T1 and ECV values were elevated in new onset SLE patients, with no statistical difference compared to patients with a longer disease course and medication history (i.e. longstanding SLE patients). These findings align with the results of Guo et al. [11]. Elevated T1 and ECV in new onset SLE patients may be attributed to acute-phase inflammation leading to cell edema, increased extracellular space, and increased water content [26]. We observed that in longstanding SLE patients, despite undergoing treatment for a prolonged period, their T1 and ECV values remain elevated. This finding suggests that while the acute inflammatory response may be managed or suppressed with treatment, myocardial damage caused by sustained low-grade inflammation may still exist. However, myocardial damage from long-term use of antimalarial drugs cannot be ruled out [27]. Since SLE can be a small vessel disease, cardiac involvement in SLE can include inflammation, fibrosis replacement, or myocardial ischemia [28]. All of these can lead to elevated T1 and ECV values. Notably, the majority of SLE patients, regardless of disease stage, show prolonged ECV values, whereas only nearly half of SLE patients show prolonged native T1 values. Since native T1 represents the combined signal from intracellular, intravascular, and interstitial components, it cannot pinpoint which specific component is abnormal, potentially obscuring abnormalities [29]. ECV, however, reflects only the extracellular matrix and is less influenced by factors such as CMR parameters or field strength, making it more sensitive than native T1 [18].

Compared to previous studies reporting LGE positivity rates ranging from 12 % to 40 % in SLE patients [11], [30], [31], the present study found a lower LGE positivity rate of 4 % in both the new onset and longstanding SLE groups. This discrepancy may be attributed to the following factors. Firstly, patients with new onset SLE had a very short disease duration (median duration of only 0.61 months) and were in the very early stage of the disease. At this point, acute myocardial injury and edema are the main pathological changes, while chronic fibrosis was not yet evident, resulting in mostly negative LGE findings. This observation is similar to the low LGE positivity rate (12 %) reported by Guo et al. [11] in patients with new onset SLE. Secondly, the patients in the longstanding SLE group in this study had a relatively short disease duration (median 60 months, i.e., 5 years), and the extent of myocardial fibrosis may not be as pronounced as in SLE patients with much longer disease durations, such as those in the studies by Myhr et al. [30] (median 19 years) and Seneviratne et al. [31] (median 11 years). Prolonged disease duration may lead to more significant myocardial fibrosis and scarring, which can be detected by LGE. Moreover, the spatial resolution of LGE is limited, and some of the tiny fibrotic foci may be overlooked due to partial volume effect, leading to false-negative results. This result suggests that myocardial fibrosis in SLE patients at relatively early stages of disease may need to be validated in higher field strength magnetic resonance imaging devices [32]. Although the number of LGE-positive patients was limited, myocardial T1, T2, and ECV values in new onset and longstanding SLE patients were elevated compared to the controls. This suggests that T1, T2, and ECV mapping techniques are more sensitive in detecting early diffuse myocardial lesions in SLE compared to LGE. However, LGE remains important for assessing late irreversible myocardial injury. Integrated use of both can more comprehensively determine the presence and severity of myocardial lesions at different stages of SLE. In our cohort of SLE patients, LV volume and function were normal, and no clinical symptoms of heart failure were observed, though this does not rule out the potential impact of myocardial inflammation. The need for careful monitoring of potential myocardial involvement is highlighted not only by quantitative CMR imaging techniques, but also by ECG abnormalities including ST-T changes, PVCs, and AV conduction delays. Although this study focused on CMR parameters related to myocardial edema, we also noted a significant reduction in LVEDVi in the longstanding treated SLE group compared to the new onset group, reflecting positive myocardial remodeling after immune suppression.

Our subgroup analysis of ECG results indicates that patients with SLE exhibiting ECG abnormalities generally display more severe myocardial involvement, suggesting that they may have progressed beyond the asymptomatic "preclinical" phase of cardiac damage. For such patients, timely further imaging studies are recommended to determine the underlying causes of the electrocardiogram abnormalities. However, it is important to emphasize that for SLE patients whose electrocardiograms do not yet show abnormalities, CMR technology offers significant value and advantages in the early detection and monitoring of myocardial damage. As a highly sensitive imaging technique, CMR can detect not only evident structural and functional abnormalities but also identify subtle myocardial changes at the tissue level through quantitative parameters such as T1, T2, and ECV. Therefore, for SLE patients with normal electrocardiogram results but potential cardiac risks, regular CMR examinations could facilitate the timely detection of occult myocardial damage.

4.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the relatively small sample size may reduce the statistical power for group comparisons and limit the generalizability of our findings. Larger studies with more balanced distribution of control and patient groups are necessary to further validate these results. Secondly, the gender imbalance, with fewer male participants, reflects SLE’s higher prevalence in women but limits assessment of potential gender differences in cardiac involvement. Future research should include more male participants to explore sex-specific effects of SLE on the heart. Thirdly, the heterogeneity in treatment protocols among longstanding SLE patients may introduce variability and impact the internal validity of our findings. Standardizing treatment protocols or conducting subgroup analyses by specific treatments would better clarify their impact on cardiac involvement. Fourth, as a cross-sectional study, this research captures only a snapshot of myocardial involvement in SLE, without establishing causal relationships. To compare myocardial involvement between new onset and longstanding SLE patients, we excluded patients who had received treatment for ≤ 6 months at the time of CMR examination. The rationale for this exclusion was that, although these patients had initiated SLE-related therapy, the efficacy might not have been stable. Including them in the analysis alongside longstanding SLE group could potentially lead to an underestimation of the suppressive effects of long-term standardized therapy on myocardial inflammation and the severity of cardiac involvement during the chronic persistent stage of the disease. Future longitudinal follow-up studies with large samples should be conducted to capture the dynamic changes in the myocardium after initiation of therapy and to provide a more comprehensive picture of the disease process. Lastly, we lack histological details of the myocardium to correlate with CMR findings. However, previous studies have documented the presence of inflammatory cells and chronic fibrosis in SLE-related cardiac involvement through histological examination [10], [33], [34], supporting the use of CMR for detecting subclinical myocardial changes in SLE when biopsy is not routinely feasible.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, subclinical myocardial injury is present in patients with new onset and longstanding SLE, even in the absence of significant cardiac insufficiency. In addition, myocardial edema was more pronounced in patients with new onset SLE, likely indicating more active inflammation due to the absence of timely and effective anti-inflammatory treatment. These findings emphasize the importance of early detection and continuous monitoring of myocardial health in SLE patients, especially through advanced imaging techniques such as CMR tissue characterization imaging. This approach may allow for more targeted treatment strategies, thereby mitigating long-term cardiac damage. Further longitudinal studies are warranted to assess the impact of anti-inflammatory therapies on myocardial remodeling in SLE patients.

Ethics approval

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee. All participants provided written informed consent before taking part in the study.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of the Higher Education Institutions of Anhui Province, China (2022AH020071). Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2308085Y48, 202304295107020027, 202304295107020028, 202304295107020029).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ren zhao: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Formal analysis, Data curation. Xiaohu Li: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Zongwen shuai: Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Hui gao: Formal analysis, Data curation. Jinxiu yang: Formal analysis, Data curation. Yuchi han: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Yongqiang Yu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Zhen wang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Xing Tang: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Chaohui Hang: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Ren Zhao, Email: zhaoren@ahmu.edu.cn.

Xiaohu Li, Email: lixiaohu@ahmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Tincani A., Rebaioli C.B., Taglietti M., Shoenfeld Y. Heart involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus, anti-phospholipid syndrome and neonatal lupus. Rheumatology. 2006;45(4):iv8–13. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doria A., Iaccarino L., Sarzi-Puttini P., Atzeni F., Turriel M., Petri M. Cardiac involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2005;14:683–686. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2200oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knockaert D.C. Cardiac involvement in systemic inflammatory diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2007;28:1797–1804. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appenzeller S., Pineau C., Clarke A. Acute lupus myocarditis: clinical features and outcome. Lupus. 2011;20:981–988. doi: 10.1177/0961203310395800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mavrogeni S., Koutsogeorgopoulou L., Dimitroulas T., Markousis-Mavrogenis G., Kolovou G. Complementary role of cardiovascular imaging and laboratory indices in early detection of cardiovascular disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2017;26:227–236. doi: 10.1177/0961203316671810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mavrogeni S., Bratis K., Markussis V., Spargias C., Papadopoulou E., Papamentzelopoulos S., Constadoulakis P., Matsoukas E., Kyrou L., Kolovou G. The diagnostic role of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in detecting myocardial inflammation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Differentiation from viral myocarditis. Lupus. 2013;22:34–43. doi: 10.1177/0961203312462265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seneviratne M.G., Grieve S.M., Figtree G.A., Garsia R., Celermajer D.S., Adelstein S., Puranik R. Prevalence, distribution and clinical correlates of myocardial fibrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a cardiac magnetic resonance study. Lupus. 2016;25:573–581. doi: 10.1177/0961203315622275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mavrogeni S., Smerla R., Grigoriadou G., Servos G., Koutsogeorgopoulou L., Karabela G., Stavropoulos E., Spiliotis G., Kolovou G., Papadopoulos G. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance evaluation of paediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and cardiac symptoms. Lupus. 2016;25:289–295. doi: 10.1177/0961203315611496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du Toit R., Herbst P.G., Ackerman C., Pecoraro A.J., Claassen D., Cyster H.P., Reuter H., Doubell A.F. Outcome of clinical and subclinical myocardial injury in systemic lupus erythematosus – A prospective cohort study. Lupus. 2021;30:256–268. doi: 10.1177/0961203320976960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winau L., Hinojar Baydes R., Braner A., Drott U., Burkhardt H., Sangle S., D’Cruz D.P., Carr-White G., Marber M., Schnoes K., Arendt C., Klingel K., Vogl T.J., Zeiher A.M., Nagel E., Puntmann V.O. High-sensitive troponin is associated with subclinical imaging biosignature of inflammatory cardiovascular involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018;77:1590–1598. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo Q., Wu L., Wang Z., Shen J., Su X., Wang C., Gong X., Yan Q., He Q., Zhang W., Xu J., Jiang M., Pu J. Early detection of silent myocardial impairment in drug-naive patients with new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a three-center prospective study. Arthritis Rheuma. 2018;70:2014–2024. doi: 10.1002/art.40671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aringer M., Costenbader K., Daikh D., Brinks R., Mosca M., Ramsey-Goldman R., Smolen J.S., Wofsy D., Boumpas D.T., Kamen D.L., Jayne D., Cervera R., Costedoat-Chalumeau N., Diamond B., Gladman D.D., Hahn B., Hiepe F., Jacobsen S., Khanna D., Lerstrøm K., Massarotti E., McCune J., Ruiz-Irastorza G., Sanchez-Guerrero J., Schneider M., Urowitz M., Bertsias G., Hoyer B.F., Leuchten N., Tani C., Tedeschi S.K., Touma Z., Schmajuk G., Anic B., Assan F., Chan T.M., Clarke A.E., Crow M.K., Czirják L., Doria A., Graninger W., Halda-Kiss B., Hasni S., Izmirly P.M., Jung M., Kumánovics G., Mariette X., Padjen I., Pego-Reigosa J.M., Romero-Diaz J., Rúa-Figueroa Fernández Í ., Seror R., Stummvoll G.H., Tanaka Y., Tektonidou M.G., Vasconcelos C., Vital E.M., Wallace D.J., Yavuz S., Meroni P.L., Fritzler M.J., Naden R., Dörner T., Johnson S.R. 2019 European league against rheumatism/american college of rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheuma. 2019;71:1400–1412. doi: 10.1002/art.40930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yee C.-S., Farewell V.T., Isenberg D.A., Griffiths B., Teh L.-S., Bruce I.N., Ahmad Y., Rahman A., Prabu A., Akil M., McHugh N., Edwards C., D’Cruz D., Khamashta M.A., Gordon C. The use of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index-2000 to define active disease and minimal clinically meaningful change based on data from a large cohort of systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Rheumatology. 2011;50:982–988. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fanouriakis A., Kostopoulou M., Alunno A., Aringer M., Bajema I., Boletis J.N., Cervera R., Doria A., Gordon C., Govoni M., Houssiau F., Jayne D., Kouloumas M., Kuhn A., Larsen J.L., Lerstrøm K., Moroni G., Mosca M., Schneider M., Smolen J.S., Svenungsson E., Tesar V., Tincani A., Troldborg A., Van Vollenhoven R., Wenzel J., Bertsias G., Boumpas D.T. 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019;78:736–745. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X., Wang H., Zhao R., Wang T., Zhu Y., Qian Y., Liu B., Yu Y., Han Y. Elevated extracellular volume fraction and reduced global longitudinal strains in participants recovered from COVID-19 without clinical cardiac findings. Radiology. 2021;299:E230–E240. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor A.J., Salerno M., Dharmakumar R., Jerosch-Herold M. T1 mapping. Basic Tech. Clin. Appl., JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2016;9:67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerqueira M.D., Weissman N.J., Dilsizian V., Jacobs A.K., Kaul S., Laskey W.K., Pennell D.J., Rumberger J.A., Ryan T., Verani M.S. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105:539–542. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng C., Liu W., Sun X., Wang Q., Zhu X., Zhou X., Xu Y., Zhu Y. Myocardial involvement characteristics by cardiac MR imaging in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Rheumatology. 2022;61:572–580. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinojar R., Foote L., Sangle S., Marber M., Mayr M., Carr-White G., D’Cruz D., Nagel E., Puntmann V.O. Native T1 and T2 mapping by CMR in lupus myocarditis: disease recognition and response to treatment. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016;222:717–726. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourg C., Curtis E., Donal E. Cardiac involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: can we do better? Int. J. Cardiol. 2023;386:157–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2023.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puntmann V.O., D’Cruz D., Smith Z., Pastor A., Choong P., Voigt T., Carr-White G., Sangle S., Schaeffter T., Nagel E. Native myocardial T1 mapping by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in subclinical cardiomyopathy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2013;6:295–301. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y., Corona-Villalobos C.P., Kiani A.N., Eng J., Kamel I.R., Zimmerman S.L., Petri M. Myocardial T2 mapping by cardiovascular magnetic resonance reveals subclinical myocardial inflammation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2015;31:389–397. doi: 10.1007/s10554-014-0560-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdel-Aty H., Siegle N., Natusch A., Gromnica-Ihle E., Wassmuth R., Dietz R., Schulz-Menger J. Myocardial tissue characterization in systemic lupus erythematosus: value of a comprehensive cardiovascular magnetic resonance approach. Lupus. 2008;17:561–567. doi: 10.1177/0961203308089401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mavrogeni S., Markousis-Mavrogenis G., Koutsogeorgopoulou L., Dimitroulas T., Bratis K., Kitas G.D., Sfikakis P., Tektonidou M., Karabela G., Stavropoulos E., Katsifis G., Boki K.A., Kitsiou A., Filaditaki V., Gialafos E., Plastiras S., Vartela V., Kolovou G. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging pattern at the time of diagnosis of treatment naïve patients with connective tissue diseases. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017;236:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pamuk O.N., Bandettini W.P., Vargha J., Shanbhag S.M., Hasni S. Clinical images: cardiovascular magnetic resonance to detect and monitor inflammatory myocarditis in systemic lupus erythematosus. ACR Open Rheuma. 2022;4:134–135. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreira V.M., Piechnik S.K., Dall’Armellina E., Karamitsos T.D., Francis J.M., Ntusi N., Holloway C., Choudhury R.P., Kardos A., Robson M.D., Friedrich M.G., Neubauer S. T1 mapping for the diagnosis of acute myocarditis using CMR: comparison to T2-weighted and late gadolinium enhanced imaging, JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2013;6:1048–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shalmon T., Thavendiranathan P., Seidman M.A., Wald R.M., Karur G.R., Harvey P.J., Akhtari S., Osuntokun T., Tselios K., Gladman D.D., Hanneman K. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging T1 and T2 mapping in systemic lupus erythematosus in relation to antimalarial treatment. J. Thorac. Imaging. 2023;38:W33–W42. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGill L., Gill C., Schoepf U.J., Bayer R.R., Suranyi P., Varga-Szemes A. Visualization of concurrent epicardial and microvascular coronary artery disease in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus by magnetic resonance imaging. Top. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2022;31:3–8. doi: 10.1097/RMR.0000000000000294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aherne E., Chow K., Carr J. Cardiac T1 mapping: techniques and applications. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2020;51:1336–1356. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myhr K.A., Zinglersen A.H., Pecini R., Jacobsen S. Myocardial fibrosis associates with lupus anticoagulant in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2024;40:127–137. doi: 10.1007/s10554-023-02970-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seneviratne M.G., Grieve S.M., Figtree G.A., Garsia R., Celermajer D.S., Adelstein S., Puranik R. Prevalence, distribution and clinical correlates of myocardial fibrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a cardiac magnetic resonance study. Lupus. 2016;25:573–581. doi: 10.1177/0961203315622275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo Y., Lin L., Zhao S., Sun G., Chen Y., Xue K., Yang Y., Chen S., Zhang Y., Li G., Zhu Y., Vliegenthart R., Wang Y. Myocardial fibrosis assessment at 3-T versus 5-T myocardial late gadolinium enhancement MRI: early results. Radiology. 2024;313 doi: 10.1148/radiol.233424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guglin M., Smith C., Rao R. The spectrum of lupus myocarditis: from asymptomatic forms to cardiogenic shock. Heart Fail. Rev. 2021;26:553–560. doi: 10.1007/s10741-020-10054-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gartshteyn Y., Tamargo M., Fleischer S., Kapoor T., Li J., Askanase A., Winchester R., Geraldino-Pardilla L. Endomyocardial biopsies in the diagnosis of myocardial involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2020;29:199–204. doi: 10.1177/0961203319897116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]