Abstract

Spin currents have long been suggested as a potential solution to addressing circuit miniaturization challenges in the semiconductor industry. While many semiconducting materials have been extensively explored for spintronic applications, issues regarding device performance, materials stability, and efficient spin current generation at room temperature persist. Nonconjugated paramagnetic radical polymers offer a unique solution to these challenges. Despite the recent observation of organic magnetism and magnetoresistance phenomena in radical polymers, their spin propagation properties have not been thoroughly studied. Here, we show that a nonconjugated radical polymer is an exceptional spin transport medium. It shows large effective spin mixing conductance of 3.2 × 1019 m–2 and a room temperature spin diffusion length of 105 nm. Its temperature-independent spin diffusion length suggests that exchange-mediated transport governs spin transport. The substantial spin mixing conductance is promising, and these results establish the potential of radical polymers in emerging spin-based applications.

Subject terms: Polymers, Spintronics, Polymers

While many semiconducting materials have been extensively explored for spintronic applications, issues regarding device performance, materials stability, and efficient spin current generation at room temperature persist. Here, the authors show that a nonconjugated radical polymer is an exceptional spin transport medium.

Introduction

Traditionally built on non-magnetic semiconductors, the core foundation for information processing and manipulation has relied upon electronic communication. However, the pursuit of extensive data storage1, high-speed functionality2, miniaturization3, and low power consumption4 poses additional challenges for the microelectronics industry. In contrast, spintronic devices hold great promise to revolutionize the current operating paradigm by leveraging both electronic and magnetic communication3. For instance, the discovery of the giant magnetoresistance (MR) effect5,6 and spin-transfer torque7 has led to the development of scalable non-volatile magnetic random-access memories8, which are easily integrated with conventional complementary metal oxide semiconductor technology, resulting in energy-efficient operation and faster switching speeds9. Additionally, generating magnons (quasiparticles) by microwave (MW) excitation of magnetic materials, and detecting them through the inverse spin Hall effect (ISHE), has opened new doors for magnon-based non-Boolean, probabilistic, and neuromorphic computing applications10. However, current spintronic devices remain reliant on traditional inorganic non-magnetic and magnetic semiconductors (e.g., GaMnAs)11. Despite decades of progress, several material drawbacks still fundamentally limit the widespread implementation of these inorganic, current-generation materials12. Most notably, the existence of heavy atoms in these semiconductors exponentially reduces both the spin coherence time and spin diffusion length, posing significant challenges in achieving the performance necessary for practical device applications13.

To address these challenges, widespread efforts have evaluated the applications of organic semiconductors (OSCs), with the development of organic spin valves featuring long-distance spin transport, substantial MR, and large spin retention time being of prime interest13,14. However, organic spin-valve devices suffer conductivity mismatch challenges, making efficient spin injection difficult to achieve13. Recently, spin-pumping and ISHE experiments have been realized in many organic materials15–18. Despite such efforts, low electrical conductivity and the lack of magnetism in these materials impair their ability to properly transport pure-spin currents over long distances18. This is because a high carrier density is required to successfully transfer spin angular momentum between the sites19,20, while magnetism is equally important to capture pure-spin currents from ferromagnetic (FM) materials via exchange interactions21. Chemical doping is commonly utilized to increase electrical conductivity, but it has major drawbacks such as localized charge carriers, long-term device stability, and doping-induced defects22–24. Furthermore, the interfacial properties between materials play a pivotal role in facilitating the transmission of pure-spin currents from an FM to an organic material15,25,26. This interfacial interaction has a substantial impact on critical parameters such as the Gilbert damping parameter (α), effective spin mixing conductance (geff↑↓), and spin backflow (β) at the interface18,26. Consequently, meticulous selection of organic materials as the medium for spin transport becomes imperative to ensure the proper propagation of pure-spin currents over long distances27, and it is a crucial step in advancing spintronics research and technology.

Radical polymers (i.e., nonconjugated macromolecules with stable open-shell pendant groups) present an intriguing solution to these opportunities, thanks to their remarkable attributes such as high electrical conductivity in the undoped form28, densely populated spin sites29, and the potential to enhance α in spin-pumping devices. A prime example of such a polymer is poly(4-glycidyloxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl) (PTEO), which shows an impressive electrical conductivity of ~20 S m−1, and the presence of an anomalous MR in this polymer provides further insights into fundamental physics that governs charge and spin transport28,29. Additionally, radical polymers exhibit a high density of spin centers, which hold significant promise for applications in spin and magnon transport30,31. The presence of pure-spin current transport and long spin diffusion length was demonstrated in our recent study32. While considerable effort has been directed towards understanding their redox-active properties and charge-conducting states33–35, the robust examination of these polymers in spintronic applications remains an underexplored frontier. Thus, an understanding of how these polymers properly propagate pure-spin currents, with full consideration of their specific molecular structure and interactions at the interface with FM thin films, is warranted. This query is intricately linked to the hypothesis that manipulating the local order and alignment among the radical groups has the potential to facilitate efficient spin angular momentum transfer through exchange interactions, where a spin current could be mediated in the form of a spin-wave (magnons), which then generates charge current at the spin sink layer. In this way, connecting the potential of these radical polymers in spintronics is of prime interest and holds the promise of unlocking promising avenues for research and technical innovations in the field.

Here, we report the synthesis and spin-transport properties of a radical polymer with a nonconjugated polyethylene oxide backbone bearing 6-oxoverdazyl radical moieties, poly[3-(4-(1-(3-methoxy-2-methylpropyl)−1H−1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)phenyl)−1,5-dimethyl-1H−1,2λ2,4,5-tetrazin-6(5H)-one] (PVEO). The effective spin-spin communications between the radical sites and high radical density of this polymer facilitate rapid spin transfer, leading to large spin diffusion length (λs) of ~105 nm, which is greater than many organic materials reported to date. The λs obtained from PVEO shows a weak dependence on temperature, indicating the dominant effect of exchange-mediated spin transport in PVEO. The spin-transport properties of PVEO were evaluated in an FM/PVEO/Pd trilayer configuration using MW-generated pure-spin current. This spin current propagates in PVEO layer through exchange interactions between pendant radical sites and then detected as a charge current at the spin sink Pd layer. Furthermore, an impressive geff↑↓ value of 3 × 1019 m−2 was attained at the FM/PVEO interface, attributed to efficient transfer of spin angular momentum. The long λs is indicative of effective exchange-mediated transport of spin angular momentum, while enhancements in α and geff↑↓ imply that unique magnetic interactions exist at FM/PVEO interface that could promote spin transfer at the interface. These unique and distinct results present the fundamentals of spin transport in a nonconjugated radical polymer and highlight its promising potential in realm of spintronics. Thus, these findings pave the way for further advancements in both nonconjugated radical polymer materials and device design, particularly for spintronic applications.

Results

Magnetic properties and electrical characterization of PVEO

The PVEO radical polymer was synthesized by utilizing a common glycidyl azide polymer (GAP) that was functionalized with an alkyne-substituted verdazyl molecule via copper-assisted azide-alkyne cycloaddition chemistry to produce the final polymer with pendant 1,5-dimethyl−6-oxoverdazyl radical groups (Fig. 1). The alkyne-substituted verdazyl, 1,5-dimethyl-3-(p-ethynylphenyl)−6-oxoverdazyl (2), was prepared by a four-step synthetic method (Fig. S1). The first step involved the condensation reaction between carbohydrazide and 4-ethynylbenzaldehyde to introduce the alkyne functional group and yield the bishydrazone. Then, methylation of the bishydrazone occurred using dimethyl sulfate and sodium hydride to form the dimethylbishydrazide (1). Subsequently, methanolysis and ring closure proceeded in the presence of p-toluenesulfonic acid as an acid catalyst to produce the tetrazinanone, which was oxidized with potassium ferricyanide to generate the alkyne-substituted verdazyl radical 2. To incorporate the verdazyl radicals and introduce spin sites into a nonconjugated polymer, GAP was synthesized by azidation of polyepichlorohydrin, which was directly obtained from the cationic ring-opening polymerization of epichlorohydrin in the presence of triphenylcarbenium hexafluorophosphate (Fig. S1). The PVEO polymer was eventually realized through the azide-alkyne click reaction between the alkyne-substituted verdazyl (2) and GAP using copper(I) bromide. Detailed structural and molecular characterizations of the intermediates and polymers are included in the Supporting Information (Figs. S2–S9).

Fig. 1. Schematics for chemical synthesis of the PVEO radical polymer.

Reaction conditions: 2 (200 mg, 0.88 mmol) and Copper (I) bromide (6 mg, 0.042 mmol) dissolved in 15 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). The reaction mixture was heated at 40 °C and cooled to room temperature after 6 h. The reaction leads to 56% polymer yield. Mn = 13.2 kg mol−1; Ð = 1.9, as measured against polystyrene (PS) standards.

The presence of the verdazyl radical groups in the alkyne-substituted verdazyl (2) small molecule and the PVEO polymer was confirmed using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. The unpaired electron of a 6-oxoverdazyl radical is delocalized between the four nitrogen atoms on the six-membered ring, and the EPR spectra display the characteristic hyperfine multiline splitting pattern for the small molecule. When the verdazyl radicals are incorporated into the polymer backbone, the EPR spectra of PVEO exhibit a broad singlet of Lorentzian shape (Fig. 2a). This change of the EPR spectra line shape is primarily due to the decreased distances between the verdazyl radical sites, which increases the intrachain spin-spin interactions along the polymer backbone. Figure 2b shows the broad Lorentzian curve of PVEO with a g-factor of 2.01, a behavior consistent with many other radical polymers. Moreover, the doubly integrated EPR spectra were used to quantify the radical content and demonstrate that the radical conversion rate was high using the click reaction to synthesize PVEO. The EPR signals of the alkyne-substituted verdazyl (2) and the PVEO polymer were both integrated twice and compared with that of the 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO-OH) standard. The radical content of compound 2 and the PVEO polymer was calculated to be 97% and 88%, respectively (Fig. 2c). The large incorporation of the radical group into the pre-formed polymer backbone is key as high radical content in PVEO is a prerequisite to exchange-mediated spin transport in spintronic devices.

Fig. 2. The EPR spectra and magnetic susceptibility data of the PVEO radical polymer.

a The first derivative EPR spectra of 2 and PVEO dissolved in chloroform collected at room temperature and at the microwave frequency of 9.8 GHz. b The typical Lorentzian g-factor plot for PVEO. c The doubly integrated EPR spectra of TEMPO-OH standard, alkyne-substituted verdazyl (2) and PVEO. By comparing their EPR signals with the TEMPO-OH standard, the radical content of 2 is determined to be 97%, while PVEO shows the radical content of 88%. d The magnetic susceptibility χm curve from 2 K ≤ T ≤ 300 K with an applied field of 0.1 T, fit to the Curie–Weiss Law with fit shown as black curve, demonstrating paramagnetic behavior. The fit is corrected with the diamagnetic susceptibility which is calculated using Pascal’s correction. The 1/χm curve plotted on right axis shows a clear dependence of susceptibility with temperature where susceptibility decreases at higher temperatures. e Moment vs. field curve from 2 K ≤ T ≤ 20 K, fitted to the paramagnetic Brillouin function for S = 1 and S = ½. f Electrical conductivity of PVEO in NiFe/PVEO/Pd device structure, displaying weak temperature dependence. The inset shows the linear I–V curve, indicating Ohmic conduction in PVEO. The data points represent the average value for four different devices and the error bars represent the standard deviation from this average.

The magnetic properties of the PVEO highlight a unique paramagnetic behavior that cannot be readily achieved in conventional conjugated polymers. The powdered PVEO sample (~4 mg) was encapsulated in a polycarbonate capsule and its magnetic properties were evaluated using superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometry. Figure 2d shows the magnetic susceptibility vs. temperature data that were fit to the Curie–Weiss Law.

| 1 |

Here χm is the mass susceptibility, C is the Curie constant, θ is the Weiss constant, T is the absolute temperature, and χ0 is the diamagnetic susceptibility. The fit returns a small negative θ of −0.15, which suggests the presence of weak antiferromagnetic interactions at temperatures <2 K. This indicates that the spins tend to align antiparallel to each other below 2 K, leading to no net magnetic moment. Moreover, using Pascal’s correction, diamagnetic susceptibility of −6.69 × 10−4 emu g−1 was found for PVEO. This small diamagnetic susceptibility arises due to the presence of closed-shell units in PVEO. The χmT vs T plot is shown in Fig. S10, indicating the presence of spin-spin exchange interaction between the verdazl radicals. This behavior has also been observed in other nonconjugated radical polymers29. The contribution of diamagnetic susceptibility is negligible, which ensures major room-temperature interactions to be paramagnetic in nature. Figure 2e shows the moment vs. field-dependent isotherm fitted to a paramagnetic Brillouin function (Eq. 2) from which the ground-state spin quantum number (S) is estimated.

| 2 |

In this equation, H is the applied magnetic field, T is the absolute temperature, g is the g-factor, kB is the Boltzmann constant, Ms is the saturation magnetization, and µB is the Bohr magneton. When the high external magnetic field is applied to a paramagnetic PVEO, all radicals in the polymer chain align to the field, and the measured magnetic moment becomes saturated (Ms). The data fit results in S = 1/2, which is consistent with doublet ground state of the polymer. The electrical conductivity of PVEO was evaluated in NiFe/PVEO/Pd multilayer device architecture, resulting in room-temperature electrical conductivity of ~10−3 S m−1. Figure 2f shows the electrical conductivity of PVEO from 2 K ≤ T ≤ 300 K in which conductivity is weakly dependent on temperature. This behavior is consistent with other nonconjugated radical polymers35–37, and indicates that charge conduction mechanism in nonconjugated radical polymers is inherently different from conventional conjugated polymers. These magnetic and electrical measurements provide a baseline to further evaluate the spin-transporting capabilities of this polymer in spintronic devices, where paramagnetic and radical-radical exchange interactions could play a key role.

Ferromagnetic resonance and dynamical spin pumping in PVEO

The interfacial properties of the polymer and the FM electrodes are crucial for facilitating the injection of spin current from FM electrodes into the polymer layer. Due to large difference in electrical conductivity between two layers, proper electrical spin injection is difficult to achieve. To circumvent this challenge, devices that use MW excitation of spin current dynamics instead of electrically injected spin current were fabricated. Figure 3a shows the illustration of spin current generation and detection with a trilayer device structure of NiFe/PVEO/Pd. An in-plane magnetic field (H) is applied along NiFe, and a small radio frequency field produces spin precession with magnetization M. The precessing magnetic moments have reduced Joule heating dissipation, a broad frequency range, and high magnetic tunability38. The excited spin waves propagate towards the PVEO/Pd interface and transfer their spin angular momentum (Js) to the Pd layer by spin pumping, causing a pure-spin current away from the PVEO/Pd interface. This pure-spin current is converted to transverse charge current (Jc) within the Pd layer. Figure 3b shows broadband ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) derivative spectrum for NiFe, NiFe/PVEO/Pd, and NiFe/Pd at 6 GHz, with NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples displaying broader Lorentzian curve. Figure 3c shows the full FMR spectrum for NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples in which peak-to-peak linewidth (ΔH) increases with frequency. The resonance field (Hres) and ΔH were derived from fit of the FMR spectra using a standard Lorentzian function. Then, α was determined from the slope of the FMR linewidth vs. frequency data by fitting the data to Eq. 3.

| 3 |

Fig. 3. FMR spectroscopy and microwave-induced spin-pumping measurement in PVEO.

a Device schematics for FMR and ISHE measurements in NiFe/PVEO/Pd trilayer devices. H represents the direction of applied in-plane field and M is the magnetization precession about H. The red spheres represent electrons with spin that are converted to charge current in palladium. b The first derivative FMR spectrum for NiFe/PVEO/Pd, NiFe/Pd, and NiFe only at microwave frequency of 6 GHz. c The full FMR spectra for NiFe/PVEO/Pd sample from 2–18 GHz. d Linewidth vs. frequency plot fitted to Eq. 3 for NiFe/PVEO/Pd, NiFe/Pd, and NiFe only samples. The data points represent the average value for four different devices and error bar represents the standard deviation from this average. e Frequency vs. resonance field response for NiFe/PVEO/Pd sample fitted to the Kittel equation (Eq. 4). f Linewidth vs. frequency plot for NiFe/Au/PVEO/Pd samples where 5 nm of Au was inserted between NiFe and PVEO. g Linewidth vs. frequency data for NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples with varying thickness of PVEO. h Change in Gilbert damping parameter of NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples with varying thickness of PVEO. i The Gilbert damping parameter for NiFe/PVEO/Pd, NiFe/PVEO, NiFe/Pd, NiFe/Ag, NiFe/Au, NiFe/Au/PVEO, and pure NiFe samples in a sequential order (left to right). NiFe/PVEO samples with no Pd still show large Gilbert damping, excluding the effect of Pd in damping.

Here, ΔH0 denotes an inhomogeneous broadening by structural imperfections, and γ is the gyromagnetic factor. In this fit, ΔH0 was ~0.2 mT for pristine NiFe, 0.4 mT for NiFe/Pd, and −0.9 mT for NiFe/PVEO/Pd (Fig. 3d). These relatively small ΔH0 (<1 mT) values indicate a homogenous magnetic structure, less structural imperfections, reproducible samples, and the reliability of the measurements. From our broadband measurements and using Eq. 3, we obtained α values of 6.6 × 10−3 for NiFe, 7.2 × 10−3 for NiFe/Pd and 1.5 × 10−2 for NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples (Fig. 3d). The larger α observed for FMR in NiFe/PVEO/Pd could originate from excess spin angular momentum loss as compared to NiFe and NiFe/Pd, due to rapid exchange interactions at NiFe/PVEO interface. It has been proposed in numerous reports that surface roughness could significantly affect Gilbert damping due to increased scattering at the interface. The atomic force microscopy analysis of PVEO films coated on NiFe reveals a small surface roughness of ~0.49 nm, indicating that surface roughness does not play a key role in our system (Fig. S11). Moreover, the α parameter has both an intrinsic and extrinsic contribution, where the intrinsic contribution accounts for electronic structure of the material and its magnetic interactions, while the extrinsic contribution is attributed to grain boundaries, structural and magnetic inhomogeneities, lattice imperfections, and two-magnon scattering39. The MW-frequency dependence of the resonance field is evaluated using the Kittel function.

| 4 |

Here, Hres is the resonance field, and HK is the anisotropy field. From the fit to the experimental data of NiFe/PVEO/Pd sample, we obtained parameters µ0Ms as 1.13 T and HK as 0 T, which is consistent with pristine NiFe saturation field, and confirms that the presence of PVEO does not significantly change the magnetic properties of NiFe film (Fig. 3e). To further understand the role of NiFe/PVEO interface, a thin 5 nm layer of Au was inserted between NiFe and PVEO. Figure 3f shows that no significant increase in α is observed for NiFe/Au/PVEO/Pd samples as compared to pure NiFe film. This implies that some interesting magnetic phenomena exist at the NiFe/PVEO interface, and this is playing a dominant role in increasing the damping. Therefore, α is utilized further utilized to estimate geff↑↓ that describes the efficiency of spin transfer at the NiFe/PVEO interface, and any associated spin backflow during the spin angular momentum transfer process. The change in damping parameter Δα = α−α0 can thus be related to effective spin conductance as follows15

| 5 |

Here, tFM is the thickness of the FM layer, ℏ is the reduced Planck’s constant, and α0 is the damping parameter for pure NiFe film. Using Eq. 5, geff↑↓ value of 3.2 × 1019 m−2 was estimated for NiFe/PVEO/Pd junctions, while 2.1 × 1018 m−2 was estimated for reference NiFe/Pd junctions. An order of magnitude increase in geff↑↓ for NiFe/PVEO/Pd junctions relative to NiFe/Pd junctions is attributed to the significant exchange interactions between radicals in singly occupied molecular orbital of PVEO and unpaired electrons in NiFe at the NiFe/PVEO interface. These exchange interactions assist the transfer of angular momentum into PVEO which then propagates through radical-radical exchange interactions in PVEO. Owing to large spin density (i.e., radical content) and alignment between radicals in PVEO, these radical-radical exchange interactions successfully transport pure-spin current, which is then detected as the charge current in Pd layer. The devices with varying thicknesses of PVEO for NiFe/PVEO/Pd architecture were also fabricated and their FMR response was recorded. Figure 3g shows the ΔH vs. frequency plot for PVEO with varying thicknesses of 121, 86.7, 54.8, 44.3, and 30.3 nm. The α values estimated using Eq. 3 for these samples are 1.5 × 10−2, 8.9 × 10−3, 7.0 × 10−3, 6.3 × 10−3, and 6.0 × 10−3, respectively. The α value decreases with PVEO’s film thickness, indicating that for thin PVEO films, spins start to backflow into the FM layer due to excessive accumulation at the interface. For films with thickness above 125 nm, no significant changes in α were observed and thus the response saturates for higher film thicknesses (Fig. 3h). This is because when the thickness of PVEO is large (i.e., longer than its λs), spins can propagate more easily through the polymer layer and the backflow factor is significantly low. To confirm whether the rise in α stems from pinhole imperfections caused by metal infiltration into the PVEO layer, the damping response of NiFe/PVEO/Pd was compared with NiFe/PVEO, both having identical PVEO thickness (Fig. 3i). The results indicate no notable alterations in α for either sample, confirming the absence of pinhole or interface defects in NiFe/PVEO/Pd devices. Moreover, additional experiments utilizing small spin Hall angle metals such as Ag and Au were conducted, and the data show that no changes in α are observed (Fig. 3i). These results speak to the importance of PVEO in transporting pure-spin currents, and the presence of exchange interactions at the interface that enable additional mechanism to control and manipulate the spin polarization of spin currents. Such behavior is not readily available from conventional OSCs, and thus radical polymers offer a unique approach to spin-transport phenomena.

Inverse spin Hall effect and pure-spin current flow through PVEO

Under FMR conditions for the NiFe/PVEO/Pd device, the process of spin pumping facilitates the transfer of spin angular momentum carried by the excited spin waves from NiFe to PVEO, and subsequently to Pd. The spin current generated at the NiFe/PVEO interface ( Js0) can be defined as follows.

| 6 |

Here, hrf is the small radio frequency field, θM is the angle of magnetization, ω = 2πf is the angular frequency, and αNiFe/PVEO = α0 + Δα. The additional damping here is due to the spin-pumping effect due to the injection and dissipation of spins from NiFe to PVEO films. According to Eqs. 5 and 6, Js0 ∝ geff↑↓ ∝ Δα; therefore large amounts of spin current are injected at the NiFe/PVEO interface due to additional damping. This sequential transfer results in the generation of ISHE voltage that is perpendicular to the spin current, and this voltage can be defined as follows.

| 7 |

Here, l is the length of the NiFe film parallel to the NiFe/PVEO interface plane; θSH and λs are the spin Hall angle and spin diffusion length in the PVEO layer, respectively; tPVEO and dF are the thickness of PVEO and NiFe layer, respectively; σPVEO and σF are the electrical conductivities of PVEO and NiFe, respectively. Because VISHE ∝ Js0, the magnitude of this voltage describes the efficiency of the spin current transfer across the PVEO interface. Figure 4a shows the overall voltage signal of NiFe/PVEO/Pd sample at applied MW of 4 GHz with magnetic field oriented at both 0° and 180° to the plane of the device. Here we represent 0° as +H and 180° as −H for simplicity where H is the applied in-plane magnetic field. A significant voltage is observed for H~Hres, where Hres is the resonance field for NiFe substrate. Voltage with different polarity is observed for different magnetic fields which is a clear signature of spin-pumping effect. Such a signal reversal with H also shows that the field-dependent thermoelectric effects, such as the Seebeck effect, cannot be attributed to the voltage signal. While the pure-spin current signal is highly symmetric in nature, spin rectification effects and the anomalous Hall effect from NiFe has both symmetric (Vsym) and antisymmetric (Vasym) components. The following Lorentzian function (Eq. 8) is used to account for contribution of symmetric and antisymmetric components.

| 8 |

Fig. 4. Dynamical spin pumping and spin transport in PVEO.

a Spin-pumping-induced voltage in NiFe/PVEO/Pd trilayer devices at 4 GHz for + H and −H magnetic fields. The data are fit to Eq. 8 to account for symmetric and antisymmetric voltage components. b Voltage vs. H−Hres for control NiFe/Pd sample at 4 GHz. c Voltage vs. H−Hres for NiFe/PVEO/Au samples where high spin Hall angle is replaced by small spin Hall angle Au. d Voltage vs. H − Hres for NiFe/PVEO/Cu samples where intensity of signal reduces due to small spin Hall angle of Cu. e Voltage response for NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples with variable thickness of PVEO. f The symmetric component fit to the data shown in (e). g VISHE vs. thickness (tPVEO) plot fitted to exponential decay function at 300 K. The fit to the data gives the spin diffusion length (λs) of ~105.1 ± 15 nm. The data points represent the average value for four different devices and error bar represents the standard deviation from this average. h Voltage vs. H for NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples at frequencies of 2, 4, and 6 GHz. i Frequency-dependent VISHE response from 2 to 8 GHz of NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples. Data points represent the average value of voltage from four different PVEO films of same thickness and error bars represent the standard deviation from this value.

Using ΔH values from FMR measurement, the data in Fig. 4a were fit to Eq. 8. The green dashed curve shows the Vsym contribution, and the black dashed curve shows the Vsym contribution. The data fit well to the Vsym than Vasym with Vsym /Vasym ~10. This suggests that the voltage signal generated has dominant ISHE contribution than artifacts like anomalous Hall effect, anisotropic MR, and spin rectification effects from NiFe. Moreover, NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples show the completely opposite response as compared to a control sample NiFe/Pd. For +H, NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples show the negative voltage response, while NiFe/Pd samples show positive voltage signal (Fig. 4b). This suggests that spin with negative polarization gets injected into PVEO from NiFe, and thus makes it crucial to investigate the magnetic interactions at the NiFe/PVEO interface.

The use of low-spin Hall angle metals (Cu and Au) confirmed the presence of spin-pumping effect and the potential of PVEO as a promising spin-transporting material. Figure 4c shows the voltage vs. H−Hres response for NiFe/PVEO/Au devices where Pd with high spin Hall angle was replaced by Au with low-spin Hall angle. A clear spin-pumping effect with reduced voltage amplitude is still observed, indicating the presence of spin transport through PVEO. Moreover, Au was further replaced by Cu that has a spin Hall angle even lower than both Pd and Au. Surprisingly, spin-pumping-induced voltage is still observed with a slightly reduced amplitude as compared to Au (Fig. 4d). The presence of weak signal in this case could be due to the ISHE effect of PVEO itself due to its relatively weak spin-orbit coupling. The choice of different metals is important to fully evaluate the role of organic layer in sustaining and transporting spin currents. Since, devices with Pd layer showed the strongest signal, we utilized such geometry for additional investigation. Figure 4e shows the thickness-dependent ISHE data for NiFe/PVEO/Pd stack in which the thickness of PVEO was varied and the corresponding ISHE voltage generated in Pd was measured. As the thickness of PVEO increases, the intensity of signal reduces. This is because the original spin current ( Js0) injected at the FM/PVEO interface decays as it traverses through PVEO layer. The symmetric component of the thickness-dependent voltage signal is shown in Fig. 4f, where clear spin pumping with opposite voltage polarity can be observed. The decay relationship can be expressed as Js = Js0 exp (−tPVEO/λs), where Js is the spin current at PVEO/Pd interface. Figure 4g shows the exponential decay fit of VISHE vs. thickness of PVEO, where VISHE is averaged as VISHE = (Vsym(+H)−Vsym (−H))/2). The fit to the data gives the λs of 105.1 nm, indicating that PVEO can transport spins over long distances. Devices with NiFe/Cu(5 nm)/PVEO/Pd geometry gave λs of 118 nm, indicating that spin diffusion length in PVEO is free of magnetic proximity effect at NiFe/PVEO interface (Fig. S12). Furthermore, frequency dependent of the signal was conducted to investigate the spin-pumping effect. Figure 4h shows the frequency-dependent signal for NiFe/PVEO/Pd devices at 2, 4 and 6 GHz for both +H and −H. At each frequency, the signal reverses with sign of −H, and the intensity of signal is weakly dependent on the frequency (Fig. 4i). This weak dependence on frequency is also a clear indication of spin-pumping effect and excludes any contributions from thermoelectric or other spurious effects.

Exchange-mediated spin transport in PVEO

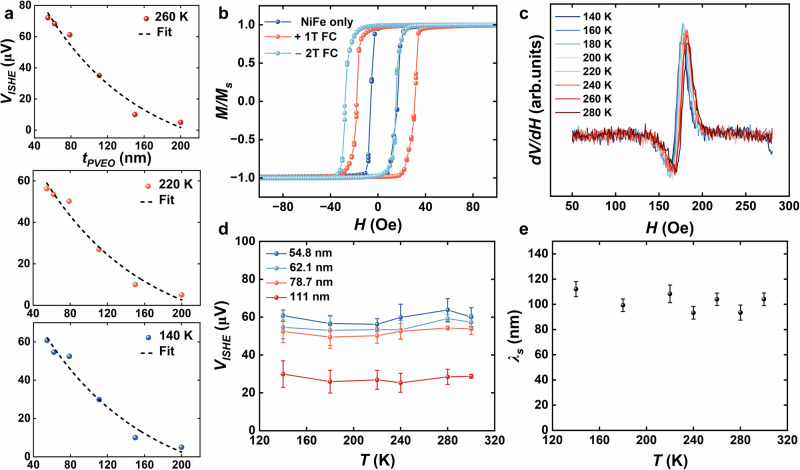

The temperature dependence of ISHE voltages and λs establish that exchange interactions between the pendant radicals are responsible for transporting spins through PVEO layer. Figure 5a shows the VISHE vs tPVEO at temperatures of 260, 220, and 140 K fit to the exponential decay function. At all temperatures, the decay behavior follows a similar trend, and λs is independent of temperature, ruling out hopping contributions from the spin transport since hopping is strongly dependent on temperature. This is further supported by the weak dependence of electrical conductivity of PVEO shown in Fig. 2f, where hopping does not seem to dominate. Furthermore, the high radical content (i.e., spin density) of PVEO (~1021 cm−3) is much higher than the exchange mediation limit (~1017 cm−3) proposed by Yu et al. 40,41 Thus, exchange interactions dominate spin-transport currents in PVEO. To further elucidate the role of exchange interactions at the FM/PVEO interface, SQUID measurements on thin films of pure NiFe and NiFe + PVEO were conducted. Figure 5b shows the field-cooled magnetization curves for pure NiFe and NiFe + PVEO system field cooled under −2T magnetic field. Under same field-cooling condition, the hysteresis loop for NiFe + PVEO broadens, indicating the increase in coercivity and the presence of FM–antiferromagnetic exchange interactions at the NiFe/PVEO interface. When the same sample is field cooled under magnetic field of different magnitude and polarity (+1T), the hysteresis loop shifts right, which is again a clear indication of exchange-bias effect. Note that the exchange bias observed here is located at the interface (i.e., within a few nanometers from the surface) and is different from the conventional FM/AFM exchange-bias effect. The different sign of voltage observed in spin-pumping experiments above can be explained by the presence of FM/AFM exchange interactions where the spin with negative polarization gets injected in NiFe/PVEO/Pd devices while spin with positive polarization is injected in NiFe/Pd devices where FM/AFM exchange interactions are not present. Figure 5c shows the field-modulated (dV/dH) voltage signal across different temperature, where voltage signal appears to be a weak function of temperature. Moreover, NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples with varying thickness of PVEO were also investigated for temperature-dependent spin-pumping voltage (Fig. 5d). For each thickness, the ISHE voltage does not deviate much from the room-temperature value and thus temperature has no effect on the λs of PVEO (Fig. 5e). These results establish the promising nature of PVEO in transporting pure-spin currents and its ability to select spins with specific orientation which provides exciting functionalities for logic design and tunability.

Fig. 5. Temperature-dependent spin-pumping effect in PVEO and magnetic interactions at NiFe/PVEO interface.

a VISHE vs. tPVEO at different temperatures of 260, 220, and 140 K fitted to the exponential decay function. b Magnetic moment vs. field response for pure NiFe (40 nm) and NiFe (40 nm)/PVEO samples. Samples were field cooled under the presence of both positive and negative external magnetic field with different magnitude. The hysteresis loop broadens and shifts with respect to x-axis under field-cooling condition, indicating the presence of exchange bias at NiFe/PVEO interface. c Temperature-dependent field-modulated voltage signal for NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples at 4 GHz. d VISHE vs. temperature response for NiFe/PVEO/Pd samples with variable thickness. The data points represent the average value for four different devices and error bar represent the standard deviation from this average. VISHE seems to be weakly dependent on temperature. e Spin diffusion length (λs) as a function of temperature. The weak dependence of λs on temperature indicates that exchange interactions among pendant verdazyl radicals in PVEO dominate in transporting spin currents through PVEO.

In the absence of device optimization, this nonconjugated radical polymer rivals long-researched metallic systems and swiftly emerging organic and inorganic semiconductor materials in diverse applications. For instance, traditional high SOC metals (Pt, Pd, Ta) typically exhibit geff↑↓ values in the range of (~1018–1019 m−2), but their practical application suffers due to challenges such as limited spin diffusion lengths and costly fabrication processes42–44. Topological insulators such as Bi2Te345, numerous inorganic oxides46–48 (NiO, LaNiO3, SVO, and IrO3), and inorganic antiferromagnets39,49,50 (FeMn, PdMn, IrMn, Mn2Au, Mn3Ga Co3O4) have also been investigated with values in the similar range as of metals (~1018–1019 m−2), and they are considered good candidates for spintronic applications (Fig. 6). Despite such values, expensive device fabrication and film growth techniques are required for their successful implementation. Recently conventional conjugated polymers51–54 (P3HT, PEDOT: PSS, P3MT) have also shown high performance with P3MT showing highest geff↑↓ to the order of 1021 m−2 by tuning its SOC (Fig. 6). In contrast, the strong performance of PVEO, with geff↑↓ of 3 × 1019 m−2, is achieved in a simple device trilayer device architecture, and such devices are easily fabricated in a rapid, high-throughput, and cost-effective manner (i.e., solution processing). We demonstrate that nonconjugated radical polymers offer multiple advantages such as achieving large spin mixing conductance and long spin diffusion lengths, ease of fabrication, and presence of exchange interactions among pendant sites that promote propagation of pure-spin currents. This impressive level of performance holds immense potential for comprehending the dynamic nature of spin currents within radical polymers, and this unique approach in utilizing paramagnetic systems in spin/magnon-based devices offer a solid roadmap to realize effective spintronic devices.

Fig. 6. Overall performance of PVEO benchmarked with other organic and inorganic materials in FMR and spin-pumping devices.

Comparison of effective spin mixing conductance of PVEO against heavy metals42–44, topological insulators45, inorganic oxides46–48, inorganic antiferromagnets39,49,50, and doped/undoped conjugated polymers51–54. The spin mixing conductance of PVEO surpasses many heavily studied inorganic and organic materials, and thus PVEO can be an effective choice for spin-transport medium for spintronic applications.

Discussion

The intrinsic paramagnetic properties of PVEO, coupled with effective radical-radical exchange interactions, contribute to the development of high-performance spintronic devices like spin valve and FMR spin pumping. When integrated with magnetically polarized electrodes, PVEO functions as an exceptional spin-transporting medium, effectively propagating spins over long distances. This capability arises from the intricate interplay between its electronic/spin structure and spin-dependent charge transfer with magnetic electrodes. Alongside its straightforward chemical synthesis, chemical stability, and solution processability, these characteristics synergize to deliver exceptional performance. Remarkably, a single trilayer device exhibits significant spin mixing conductance and spin diffusion length at room temperature. This work demonstrates that nonconjugated radical polymers offer a rare combination of advantages such as radical-radical exchange interactions, magnetic interactions with FM thin films and high sensitivity to magnetic fields, effectively overcoming inherent limitations within OSC technologies. These findings lay a robust foundation for exploring an extensive range of radical polymers in the forefront of spin-based applications, leveraging their chemical stability and facile synthetic pathways.

Methods

Device fabrication for electrical measurements

Glass wafers from Delta Technologies were sonicated in toluene, acetone, and isopropanol, in a sequential manner. The cleaned substrates were baked in the oven at 120 °C to remove any residual solvent. The substrates were then loaded into a substrate holder and moved to a nitrogen-filled glovebox equipped with a thermal evaporator and spin coater. Using a shadow mask with width of 200 µm, 40 nm of NiFe was thermally evaporated with a base pressure of 1 × 10−6 mbar and a rate of 1 Å s−1. After NiFe deposition, devices were transported to a glove box equipped with spin coater and a 20 mg mL−1 PVEO dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF) solution was deposited through spin-coating at rotational speed of 1000 rpm. The thickness of the polymer was measured using the Bruker profilometer. Then, the devices were annealed at 40 °C for 10 min, and they were transferred back to the thermal evaporator. At this point, 20 nm of palladium was thermally evaporated with another shadow mask of width 100 µm to produce final devices in a crossbar configuration with cross sectional area of 2 × 10−8 m2. A slow evaporation rate (i.e., <0.1 Å s−1) was employed for top metal deposition to avoid damaging the PVEO thin film. After deposition, the devices were thermally annealed again at 40 °C to remove any residual solvent.

Electrical characterization of PVEO spin valves

Electrical characterization measurements were carried out on a Quantum Design physical property measurement system (PPMS). Devices were mounted on a rotator sample board, and a four-wire connection with contacts was made by using silver paste. A Keithley 2450 source meter was used to control the device with the LabVIEW interface. Four-point measurements were performed in which current was applied across two contacts and voltage was measured across other two contacts. Current-voltage (I–V) measurements were acquired by sweeping voltages across the range of −2 V ≤ V ≤ +2 V, and 2 K ≤ T ≤ 300 K and the sample was left at each temperature for 30 min to equilibrate at the given temperature. The devices were initially cooled to 2 K and then the temperature was raised slowly to collect I–V curves across different temperature. These I–V curves are useful to determine the quality of devices and getting insights into charge/spin-transport mechanisms within the PVEO layer.

Fabrication of ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) and spin-pumping devices

FMR is a powerful tool for studying FM materials in which the gyromagnetic ratio, anisotropy field constant, and damping constant can be evaluated. The main advantage of using the FMR and ISHE techniques to quantify spin transport is that these devices do not rely on electrical charge injection. Thus, there is no net charge current flow associated with spin current injection. This helps in avoiding conductance mismatch issues. This technique has become widely prevalent to study pure-spin transport in plethora of both inorganic and OSCs.

In this study, NiFe/Pd multilayer thin film stacks were deposited on pre-cleaned Si/SiO2 wafers using thermal evaporation with a base pressure of 3 × 10−7 mbar in a similar fashion to that of spin-valve devices. The dimensions of the wafers were 5 × 6 mm2. NiFe/PVEO/Pd devices. The thickness of PVEO thin films was measured using the profilometer. The FMR response was measured with a broadband coplanar waveguide (CPW) (NanOSsc), embedded in the Quantum Design PPMS system. Electrical insulation from the CPW was attained by applying cellophane tape on the CPW and underneath the sample. To measure the ISHE, copper wires were soldered with the pins on the CPW, and the sample was placed on the top of wires insulated from CPW. The measurements were typically performed by keeping a fixed frequency while sweeping the magnetic field (Hdc) to eliminate the dominant frequency-dependent background. As Hdc is swept through the resonance condition, the magnetization resonantly precessed and absorbed energy from CPW. The broadband RF diode then converted this decrease in transmitted energy into a DC voltage.

The direction of the magnetic field was also changed to verify if the voltage signal is due to spin-pumping effect or arises due to any other artifacts. Here, we represent a positive magnetic field (as applied 0° to the plane of the device), and a negative magnetic field (as applied 180° to the plane of the device). Due to spin-pumping and the ISHE effect, the voltage signal was expected to change its polarity upon changing the applied field direction. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was improved by adjusting the input gain of the lock-in amplifier. A built-in internal relay in NanOSC is used to pulse the ISHE voltage to create a square wave that lock-in detector can measure. This results in characteristic pulsed-modulated signal exhibiting a single absorption peak as the direct non-derivative ISHE voltage (i.e Lorentzian shape). The final values of the voltage were normalized with the input gain of the lock-in amplifier which is used to improve the SNR of the voltage signal.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR), under the support provided by the Organic Materials Chemistry program (FA9550-23-1-0240, Program Manager: Dr. Kenneth Caster, awarded to B.W.B. and B.M.S.). We thank the AFOSR for this generous support.

Author contributions

H.T. conducted device fabrication, electrical measurements, FMR, ISHE, and SQUID characterization, and analyzed the data under the supervision of B.M.S. and B.W.B. K.L. conducted materials synthesis and performed material characterizations. Y.-F.Y. assisted with FMR and ISHE measurements and helped to verify the results. K.B. helped with reviewer comments and performing additional experiments. H.T., K.L., B.M.S., and B.W.B. wrote the draft of the paper, and all authors contributed to the reading and editing of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Veerabhadrarao Kaliginedi, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The main data supporting the findings of this study is available with in the paper, and its supplementary information file. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Brett M. Savoie, Email: bsavoie@purdue.edu

Bryan W. Boudouris, Email: boudouris@purdue.edu

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-56056-w.

References

- 1.Puebla, J., Kim, J., Kondou, K. & Otani, Y. Spintronic devices for energy-efficient data storage and energy harvesting. Commun. Mater.1, 24 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farkhani, H., Tohidi, M., Farkhani, S., Madsen, J. K. & Moradi, F. A low-power high-speed spintronics-based neuromorphic computing system using real-time tracking method. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst.8, 627–638 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dieny, B. et al. Opportunities and challenges for spintronics in the microelectronics industry. Nat. Electron.3, 446–459 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo, Z. et al. Spintronics for energy- efficient computing: an overview and outlook. Proc. IEEE109, 1398–1417 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binasch, G., Grünberg, P., Saurenbach, F. & Zinn, W. Enhanced magnetoresistance in layered magnetic structures with antiferromagnetic interlayer exchange. Phys. Rev. B39, 4828–4830 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baibich, M. N. et al. Giant magnetoresistance of (001)Fe/(001)Cr magnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett.61, 2472–2475 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ralph, D. C. & Stiles, M. D. Spin transfer torques. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.320, 1190–1216 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatti, S. et al. Spintronics based random access memory: a review. Mater. Today20, 530–548 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent, A. D. & Worledge, D. C. A new spin on magnetic memories. Nat. Nanotechnol.10, 187–191 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chumak, A. V., Vasyuchka, V. I., Serga, A. A. & Hillebrands, B. Magnon spintronics. Nat. Phys.11, 453–461 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahn, E. C. 2D materials for spintronic devices. npj 2D Mater. Appl.4, 17 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camarero, J. & Coronado, E. Molecular vs. inorganic spintronics: the role of molecular materials and single molecules. J. Mater. Chem.19, 1678–1684 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, D. & Yu, G. Innovation of materials, devices, and functionalized interfaces in organic spintronics. Adv. Funct. Mater.31, 2100550 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gobbi, M., Novak, M. A. & Del Barco, E. Molecular spintronics. J. Appl. Phys.125, 9–12 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun, D. et al. Inverse spin Hall effect from pulsed spin current in organic semiconductors with tunable spin–orbit coupling. Nat. Mater.15, 863–869 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qaid, M. M., Mahani, M. R., Sinova, J. & Schmidt, G. Quantifying the inverse spin-Hall effect in highly doped PEDOT:PSS. Phys. Rev. Res.2, 13207 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghising, P., Biswas, C. & Lee, Y. H. Graphene spin valves for spin logic devices. Adv. Mater.35, 2209137 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng, N., Liu, H. & Zeng, Y.-J. Dynamical behavior of pure spin current in organic materials. Adv. Sci.10, 2207506 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe, S. et al. Polaron spin current transport in organic semiconductors. Nat. Phys.10, 308–313 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, S. J. et al. Long spin diffusion lengths in doped conjugated polymers due to enhanced exchange coupling. Nat. Electron.2, 98–107 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coronado, E. Molecular magnetism: from chemical design to spin control in molecules, materials and devices. Nat. Rev. Mater.5, 87–104 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi, H., Liu, C., Jiang, Q. & Xu, J. Effective approaches to improve the electrical conductivity of PEDOT:PSS: a review. Adv. Electron. Mater.1, 1500017 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 23.You, J. et al. Improved air stability of perovskite solar cells via solution-processed metal oxide transport layers. Nat. Nanotechnol.11, 75–81 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroon, R. et al. Thermoelectric plastics: from design to synthesis, processing and structure–property relationships. Chem. Soc. Rev.45, 6147–6164 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun, D. et al. Spintronic detection of interfacial magnetic switching in a paramagnetic thin film of tris(8-hydroxyquinoline)iron(III). Phys. Rev. B95, 54423 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harii, K. et al. Spin pumping in a ferromagnetic/nonmagnetic/spin-sink trilayer film: spin current termination. Key Eng. Mater.508, 266–270 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koopmans, B. Pumping spins through polymers. Nat. Phys.10, 249–250 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joo, Y., Agarkar, V., Sung, S. H., Savoie, B. M. & Boudouris, B. W. A nonconjugated radical polymer glass with high electrical conductivity. Science359, 1391–1395 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akkiraju, S., Gilley, D. M., Savoie, B. M. & Boudouris, B. W. Anomalous magnetoresistance in a nonconjugated radical polymer glass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA120, e2308741120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan, Y. et al. Electronic and spintronic open-shell macromolecules, Quo Vadis? J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 626–647 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeo, H. et al. Electronic and magnetic properties of a three-arm nonconjugated open-shell macromolecule. ACS Polym. Au2, 59–68 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tahir, H. et al. Spintronic pathways in a nonconjugated radical polymer glass. Adv. Mater. 36, 2406727 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Tomlinson, E. P., Hay, M. E. & Boudouris, B. W. Radical polymers and their application to organic electronic devices. Macromolecules47, 6145–6158 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukherjee, S. & Boudouris, B. W. Organic Radical Polymers (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

- 35.Baradwaj, A. G., Rostro, L., Alam, M. A. & Boudouris, B. W. Quantification of the solid-state charge mobility in a model radical polymer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 213306 (2014).

- 36.Rostro, L., Baradwaj, A. G. & Boudouris, B. W. Controlled radical polymerization and quantification of solid state electrical conductivities of macromolecules bearing pendant stable radical groups. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces5, 9896–9901 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rostro, L., Wong, S. H. & Boudouris, B. W. Solid state electrical conductivity of radical polymers as a function of pendant group oxidation state. Macromolecules47, 3713–3719 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghader, D., Gao, H., Radaelli, P. G., Continenza, A. & Stroppa, A. Theoretical study of magnon spin currents in chromium trihalide hetero-bilayers: implications for magnonic and spintronic devices. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.5, 15150–15161 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy, K. et al. Spin to charge conversion in semiconducting antiferromagnetic Co3O4. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater.5, 1575–1580 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu, Z. G. Suppression of the Hanle effect in organic spintronic devices. Phys. Rev. Lett.111, 16601 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu, Z. G. Spin-orbit coupling, spin relaxation, and spin diffusion in organic solids. Phys. Rev. Lett.106, 106602 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, W., Han, W., Jiang, X., Yang, S.-H. & Parkin, S. S. P. Role of transparency of platinum–ferromagnet interfaces in determining the intrinsic magnitude of the spin Hall effect. Nat. Phys.11, 496–502 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chudo, H. et al. Spin pumping efficiency from half metallic Co2MnSi. J. Appl. Phys.109, 73915 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tao, X. et al. Self-consistent determination of spin Hall angle and spin diffusion length in Pt and Pd: the role of the interface spin loss. Sci. Adv.4, eaat1670 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pandey, L. et al. Topological surface state induced spin pumping in sputtered topological insulator (Bi2Te3)–ferromagnet (Co60Fe20B20) heterostructures. J. Appl. Phys.134, 43906 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, H., Du, C., Hammel, P. C. & Yang, F. Antiferromagnonic spin transport from Y3Fe5 O12 into NiO. Phys. Rev. Lett.113, 1–5 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hauser, C. et al. Enhancement of spin mixing conductance in La0.7Sr0.3MnO3/LaNiO3/SrRuO3 heterostructures. Phys. Status Solidi257, 1900606 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Macià, F., Mirjolet, M. & Fontcuberta, J. Efficient spin pumping into metallic SrVO3 epitaxial films. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.546, 168871 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh, B. B., Roy, K., Chelvane, J. A. & Bedanta, S. Inverse spin Hall effect and spin pumping in the polycrystalline noncollinear antiferromagnetic Mn3Ga. Phys. Rev. B102, 174444 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang, W. et al. Spin Hall effects in metallic antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett.113, 196602 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gupta, R., Pradhan, J., Haldar, A., Murapaka, C. & Chandra Mondal, P. Chemical approach towards broadband spintronics on nanoscale pyrene films. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202307458 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manoj, T. et al. Giant spin pumping at the ferromagnet (permalloy)—organic semiconductor (perylene diimide) interface. RSC Adv.11, 35567–35574 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vetter, E. et al. Tuning of spin-orbit coupling in metal-free conjugated polymers by structural conformation. Phys. Rev. Mater.4, 85603 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wittmann, A. et al. Tuning spin current injection at ferromagnet-nonmagnet interfaces by molecular design. Phys. Rev. Lett.124, 27204 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The main data supporting the findings of this study is available with in the paper, and its supplementary information file. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.