Summary

Background

There are few studies comparing health status trends among middle-aged and older adults in countries currently experiencing a rapid demographic and economic transition in the Asia-Pacific, relative to their high-income regional counterparts. This study investigates trends in functional limitations among individuals aged 45 years and above in six major Asia-Pacific countries, ranging from middle- to high-income, from 2001 to 2019 and examines disparities across socioeconomic and demographic sub-groups.

Methods

Data on 778,507 individuals from seven surveys in three high-income countries (Australia, Japan, South Korea) and three middle-income countries (China, Indonesia, and India) were used. Activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and mobility measures served as indicators of functional limitations. Age-standardized prevalence was used to assess prevalence trends in functional limitations and their distribution across sex and age. Multivariate linear probability models were used to examine whether the patterns still hold when controlling for birth cohorts and socioeconomic and demographic factors.

Findings

People aged 45 years and above in Australia, Japan, and South Korea experienced declines in functional limitations, whereas increases were observed in India and Indonesia. The findings for China were unclear and varied depending on the indicator. Changes in prevalence of functional limitations over time were more pronounced among people aged over 60 years. Higher prevalence of functional limitations was observed for respondents with lower education and among those are not currently married across countries.

Interpretation

Study findings highlight the potential for cross-national learning to address functional limitations among older populations in low- and middle-income countries.

Funding

Not applicable.

Keywords: Population ageing, Functional limitations, Asia-Pacific, ADL, Disability

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Prior to conducting this study, we searched PubMed for the existing evidence on analyses of comparative country experiences in prevalence of functional limitations and their trends among middle-aged and older adults in the Asia-Pacific region, using the terms “functional limitations”, or “ADL”, or “disability”, combined with “prevalence”, “comparative study” or “trend” for original publications in English from Jan 1, 2010 to July 1, 2024. Studies that examined trends in functional limitations over multiple years were included. The existing literature is primarily from North America and from European countries. The literature from countries in the Asia-Pacific region is limited to mostly to China and high-income countries, and typically focused on single countries. Data from high-income settings (Australia, Japan, and South Korea) generally indicate reductions in functional limitations over time. Evidence from China is inconclusive. Much of this work lacks a comparative perspective, considers trends over short-time periods, and does not include the recent experiences of large countries such as India and Indonesia that are undergoing rapid demographic and economic transitions.

Added value of this study

Our analysis reports on trends in multidimensional measures of functional limitations among middle-aged and older adults between 2000 and 2019 and, to our knowledge, is the first comparative study of these trends across six major Asia-Pacific countries and across population subgroups. Taken together the sample size we consider is significantly larger than previous work conducted in the region -we used data from seven nationally representative household surveys, with 778,507 observations from six countries—Australia, China, Japan, South Korea, India, and Indonesia. We confirmed using more recent data compared to previous work that the prevalence of functional limitations continues to decrease in Australia, Japan, and South Korea over time whereas it is increasing in India and Indonesia, which is especially pronounced among individuals aged 60 years and above. Moreover, we found that the average age of functional limitation onset has been increasing in Japan and South Korea over time while the onset appears to be occurring at younger ages in India and Indonesia. Individuals with lower levels of educational attainment experienced higher prevalence of functional limitations relative to more educated counterparts, respectively, across the study countries.

Implications of all the available evidence

The improvement in physical functioning among older adults over time in high-income countries in the region in line with prevailing trends in high-income western countries. However, our findings suggest that the experience of high-income countries may not be replicated in India and Indonesia, posing challenges for the health and social care of their older populations. Apart from the need for prioritizing prevention and management strategies to address functional limitations in the middle-income countries of Asia-Pacific, our findings suggest the potential for learning from the experiences of high-income countries in the design of effective policies.

Introduction

There is a major demographic, epidemiological and economic transition currently underway in the Asia-Pacific region that contains over 60 percent of the global population and accounts for 34% of the global gross domestic product (GDP).1 By 2050, the share of the population aged over 60 years in this region is projected to increase to approximately 25% of the total, almost doubling its share of 13 percent in 2020.2 The burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), known to be associated with declining health and functional status together with ageing, has also been growing rapidly in the region, rising from 44% of the overall disability-adjusted life years lost in 1990 to 66% in 2019.3,4 Functional limitations, which refer to restrictions in basic physical and mental capabilities that affect the performance of activities of daily living, are associated with lower productivity, reduced quality of life, and increased need for healthcare and support of daily activities.5,6 We believe that the trajectory of these transitions, as captured by the functional limitations in the population, is likely to have major implications not just for the Asia-Pacific, but globally.

The goal of this paper is to undertake a comparative assessment of recent trends in the functional status in adult populations, alongside a set of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, in six countries (Australia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, and South Korea) that collectively account for about three-quarters of the population in the Asia-Pacific region. Along with their large share in the economies and population, the choice of these countries is also motivated by the need to capture the considerable cross-country heterogeneity that exists across the region in ageing and economic circumstances.7 At one end are high-income countries (HICs) in the region such as Australia, Japan and South Korea that have among the highest share of older adult populations in the region (and globally), and are expected to continue to age over the next few decades. In contrast, middle-income countries (MICs), such as India and Indonesia, currently have a high population share of younger and working age groups but are likely to experience significant population ageing in the next few decades (Fig. 1). These countries are likely to become older before they become richer. China is an exception to this group–with rapid population ageing and the share of older adults close to those observed in high-income countries, while still in the upper middle-income category. Along with China, India and Indonesia will likely be the primary drivers of the patterns of demographic changes in the region going forward, given their population sizes. Coping with these challenges in a sustainable manner and designing effective policy responses requires a good understanding of underlying trends in health status and functional limitations, including how and why country and population sub-group experiences vary, along with lessons offered by the experiences of the high-income countries in the region.

Fig. 1.

Share of the population aged 60 years and above in selected countries from the Asia-Pacific. Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2024). World Population Prospects 2024, Data Sources. UN DESA/POP/2024.

Trends in functional limitations among older adults have been widely studied in the United States and in European countries. Recent evidence suggests that physical functioning of older adults is improving in these high-income settings8,9 but prevalence of functional limitations among the oldest-old population appears to be rising over time.10 These findings suggest a possible postponement of the onset of functional limitations to older ages in high-income countries. Studies in low- and middle-income countries have been fewer, due to limited availability of longitudinal data.11 In the Asia-Pacific region, as elsewhere, existing studies have generally been limited to high income settings (e.g., Australia, Japan, and South Korea), with some recent work on China, mostly in the form of single-country studies. Analyses from Japan and South Korea point to improvements in functioning over time,12,13 whereas the evidence from China is inconclusive.14, 15, 16 Middle-income countries of the Asia-Pacific region are however experiencing a high per capita disease burden from NCDs among middle-aged adults, comparable to that of older adults in their regional high-income country counterparts (Appendix Fig. S1).17 Given that earlier onset of NCDs is likely to be associated with emergence of functional limitations at younger ages, functional limitations may be rising (not falling) among middle aged adults in these countries. Existing literature from the region does not use a comparative lens and many studies are out of date given that several rounds of data have been subsequently collected. Crucially, few analyses have considered socioeconomic differentials in functioning, and thus are unable to offer guidance on how health trajectories are likely to change as countries become richer. It is these gaps this paper intends to address, in addition to new analyses and data for India and Indonesia.

Methods

Data

Data for this work were drawn from seven nationally representative surveys (with one exception that focused mostly on the oldest population) that collected information from respondents over multiple years between 2001 and 2019: The Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA), Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions (CSLC), Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA), China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), The Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), The Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS), and India Human Development Survey (IHDS). HILDA, KLoSA, CHARLS, CLHLS, IFLS, and IHDS collected longitudinal data by following up the same households every survey year while CSLC is designed as a cross-sectional survey, collecting data from a sample of Japanese households every three years. CLHLS has a unique feature in that it has a high representation of oldest-old population in its sample, from selected provinces, while other surveys in this study are designed to ensure national representativeness. CLHLS is included in this study to serve as a supplementary source for China, compensating for the lack of CHARLS data in 2000s. Additional details about survey design and data are available in Appendix A.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 To explore trends between 2000 and 2019, we used data from 19 waves of HILDA (2001–2019), six waves of CSLC (2001–2016), seven waves of KLoSA (2006–2018), four waves of CHARLS (2011–2018), six waves of CLHLS (2002–2018), three waves of IFLS (2000–2014), and two waves of IHDS (2004–2014). Respondents aged 45 years and above were included in the analysis. Observations with any missing data on outcome variables and covariates were excluded, accordingly, our final study sample comprised a total of 778,507 individual observations from seven surveys.

Measurements

Functional limitations

Three measures of functional limitations were considered for the analysis: (i) activities of daily living (ADL); (ii) instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) which are frequently used in ageing studies to indicate individuals’ functional independence; and (iii) mobility measures such as walking, standing, and climbing stairs. ADL indicators could be constructed from all seven surveys. However, due to limited data availability, we only used four surveys for IADL (KLoSA, CHARLS, CLHLS, and IFLS) and five surveys for indicators of mobility (HILDA, CHARLS, CLHLS, IFLS, and IHDS). In general, comparing prevalence in functional limitations across countries in our sample is difficult given the survey questions on functional limitations are not perfectly harmonized; at best within-country comparisons of prevalence are feasible. Instead, we sought to compare trends in similar indicators of functional limitations across countries in three ways: (a) using an indicator of functional limitations that was very close in terms of definition across surveys (ADL: dressing and bathing, IADL: shopping and preparing meals, mobility: walking 1 km); (b) using all variables for which information was available to construct a composite indicator which took the value 1 if any of the limitations in a specific survey was reported; 0 otherwise; and (c) comparing trends in indicators of severity of functional limitations that would conceivably be less sensitive to minor changes in survey questions. Indicators (a) and (b) were highly correlated (0.996 in the KLoSA and greater than 0.90 in other surveys. Results on (c) served as a sensitivity analysis and are reported in the Appendix. Detailed comparisons of questions across the survey instruments are reported in Appendix Tables S1 and S2.

Socioeconomic and demographic sub-groups

Socioeconomic and demographic factors included in this study were age, sex, educational attainment, marital status, and residential area. Age was grouped in five-year intervals. Marital status was classified into three categories—married, never married, and other (separated, divorced, and widowed). Educational attainment was divided into three levels (high, middle, and low) (definitions of education attainment are made available in Appendix Table S3). Residential area was dichotomized as urban and rural.

Statistical analysis

We first describe the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the study sample from each survey dataset. We calculated the shares of respondents with ADL, IADL, and mobility limitations by age, sex, education level, marital status, and residential area to assess the association between functional limitations and socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Trends in ADL, IADL, and mobility limitations were then examined by calculating age-standardized prevalence for each year for which data was available. The population age distribution among people aged 45 years and older from 2020 in each country was used as the standard population for age-standardization. Population data was obtained from United Nations World Population Prospects 2024.7 Age-standardized prevalence was compared across time points within a country to assess trends. To explore trends across different age groups, we plotted the prevalence of each functional limitation measure by five-year age groups for selected survey years between 2000 and 2019. Cross-sectional sampling weights were applied to ensure the representativeness of the sampled population in each survey wave and in each country. The prevalence of functional limitations in the same age group was compared across survey years within a country to evaluate the changes over time by age.

Sensitivity analysis

Considering birth cohort differences, we applied multivariate linear probability models to examine whether the observed trends still hold when controlling for birth cohorts and socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. The specification of the regression equation is available in the Appendix (Equation (1)). To check the robustness of the findings, we assessed whether increased severity of the outcome (functional limitations) affects the results. The severity was defined in two ways, based on respondents' responses to survey questions. Specifically, we considered respondents as having severe functional limitations if (i) they reported not being able to conduct activities even with someone's support, or if (ii) they reported multiple activity limitations. Trends in severe functional limitations also were assessed through changes in age-standardized prevalence over time. Lastly, for the datasets with missing values on outcome variables and covariates resulting in dropping of 5% or more of the original sample of respondents aged 45 years and over (HILDA, CSLC, and IFLS), multiple imputation techniques were used to account for missing data and to assess the sensitivity of our findings on prevalence of functional limitations and associated trends.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by The University of Melbourne Office of Research Ethics and Integrity (Reference number: 2023-26691-42648-4).

Results

Among those aged 45 years and above in the seven datasets (N = 778,507), 8·3% of respondents had missing data on ADL and/or socioeconomic and demographic data, resulting in the final sample size of 714,077 for the analyses on ADL. The final sample size for the analyses on IADL and mobility were 228,077 and 397,659 respectively. Sampling flowcharts can be found in Appendix Fig. S2. Characteristics of observations from the seven datasets used in the study are reported in Table 1. The mean age of sample respondents is higher in the KLoSA and CLHLS datasets compared to the other six datasets. Almost three-quarters of the respondents reported being currently married, except in CLHLS which exclusively sampled individuals who were 65 years or older (in this group 59·9% reported being currently married).

Table 1.

Characteristics of observations from pooled data between 2000 and 2019.

| Australia |

Japan |

South Korea |

China |

Indonesia |

India |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HILDA | CSLC | KLoSA | CHARLS | CLHLS | IFLS | IHDS | |

| Total sample | N = 124,696 | N = 267,211 | N = 56,723 | N = 73,487 | N = 79,580 | N = 25,953 | N = 95,937 |

| Age group | |||||||

| 45–49 | 22,625 (18.2%) | 36,853 (13.7%) | 2941 (6.8%) | 11,868 (16.8%) | – | 6641 (26.1%) | 22,748 (23.5%) |

| 50–54 | 21,460 (17.7%) | 38,958 (14.4%) | 7145 (17.0%) | 12,557 (16.9%) | – | 5239 (21.3%) | 18,811 (19.5%) |

| 55–59 | 19,611 (16.0%) | 38,652 (14.4%) | 9000 (21.0%) | 12,877 (17.0%) | – | 4324 (17.4%) | 15,000 (15.8%) |

| 60–64 | 17,041 (13.5%) | 38,206 (14.3%) | 8341 (17.0%) | 12,876 (16.4%) | – | 3339 (13.5%) | 13,431 (14.3%) |

| 65–69 | 14,513 (11.1%) | 35,478 (13.4%) | 8283 (12.9%) | 9568 (12.5%) | 7036 (35.5%) | 2534 (8.5%) | 10,219 (10.9%) |

| 70–74 | 22,625 (9.0%) | 28,850 (10.8%) | 7886 (10.5%) | 6365 (8.6%) | 8680 (27.6%) | 1869 (6.4%) | 7435 (7.5%) |

| 75+ | 21,460 (14.5%) | 50,214 (19.0%) | 13,127 (14.8%) | 7376 (11.7%) | 63,864 (36.9%) | 2007 (6.9%) | 8293 (8.6%) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 58,027 (48.3%) | 124,867 (46.7%) | 24,398 (46.5%) | 35,617 (48.8%) | 34,445 (47.2%) | 12,201 (48.2%) | 48,033 (50.1%) |

| Female | 66,669 (51.7%) | 142,344 (53.3%) | 32,325 (53.5%) | 37,870 (51.2%) | 45,135 (52.8%) | 13,752 (51.8%) | 47,904 (49.9%) |

| Education | |||||||

| High | 27,558 (20.5%) | 20,406 (17.7%) | 5738 (13.0%) | 1514 (3.1%) | 1626 (2.6%) | 1664 (6.3%) | 5458 (5.1%) |

| Middle | 50,662 (41.2%) | 70,292 (60.9%) | 17,123 (36.5%) | 7555 (12.1%) | 2858 (5.4%) | 3178 (11.8%) | 11,436 (11.2%) |

| Low | 46,746 (38.3%) | 24,895 (21.4%) | 33,862 (50.5%) | 64,418 (84.8%) | 75,096 (92.0%) | 21,111 (81.9%) | 79,043 (83.7%) |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 88,041 (72.4%) | 198,818 (74.3%) | 43,484 (79.2%) | 63,464 (85.1%) | 26,395 (59.9%) | 19,566 (76.7%) | 73,751 (76.4%) |

| Not married | 29,053 (21.6%) | 16,426 (6.2%) | 462 (1.3%) | 554 (0.8%) | 788 (1.2%) | 335 (1.1%) | 895 (0.9%) |

| Other | 7602 (6.0%) | 51,967 (19.5%) | 12,777 (19.5%) | 9469 (14.1%) | 52,397 (38.9%) | 6052 (22.2%) | 21,291 (22.7%) |

| Residential area | |||||||

| Urban | 101,846 (84.5%) | – | 42,849 (78.9%) | 29,559 (49.8%) | 36,948 (43.2%) | 13,361 (46.5%) | 31,585 (29.0%) |

| Rural | 22,850 (15.5%) | – | 13,874 (21.1%) | 43,928 (50.2%) | 43,632 (56.8%) | 12,592 (53.5%) | 64,352 (71.0%) |

Note: Sample includes pooled data of HILDA (The Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia), CSLC (Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions), KLoSA (Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging), CHARLS (China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study), CLHLS (The Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey), IFLS (The Indonesia Family Life Survey), IHDS (India Human Development Survey), and LASI (Longitudinal Ageing Study in India). Data are weighted proportions (%).

Table 2 illustrates the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics associated with difficulty in dressing and bathing which are the most commonly available indicators of ADL limitations across the seven surveys. Prevalence of ADL limitations was higher by more than 10·0% among respondents aged over 75 years compared to the youngest adults in the sample (45–49 years old) in all six countries, with the magnitude of the difference in prevalence varying across countries. ADL limitations were reported to be 0·8% to 2·6% higher among women than men, except for Australia (male: 14·0% vs female: 12·0%). Respondents residing in a rural area reported higher prevalence of ADL limitations compared with those residing in an urban area but estimates from CLHLS showed the opposite pattern. These differences in the prevalence of ADL limitations by sex and residential area generally hold up after controlling for birth cohorts and socioeconomic and demographic factors; however, in South Korea, regression coefficients suggest a higher likelihood of ADL limitations among men compared to women and among urban residents compared to rural residents, but the difference is very small. Groups with lower levels of educational attainment consistently showed higher prevalence rates of ADL limitations. Married respondents reported lower prevalence of functional limitations compared to respondents that were not currently married. Prevalence of IADL limitations and mobility limitations by socioeconomic and demographic groups can be found in Appendix Table S6. In general, prevalence of IADL follows patterns similar to ADL limitations, but IADL limitations were more pronounced among men in South Korea and Indonesia compared to women. Prevalence of mobility limitations was characterized by a larger gap in sex relative to ADL and IADL limitations, with women showing higher prevalence across countries even after controlling for birth cohorts and covariates. Aligned with ADL limitations, although crude prevalence of mobility limitations was higher among rural residents compared to urban residents, this association disappeared when controlling for birth cohorts and covariates in China (CLHLS) and Indonesia.

Table 2.

Distribution of limitations in activities of daily living across sociodemographic sub-groups.

| Australia |

Japan |

South Korea |

China |

Indonesia |

India |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HILDA |

CSLC |

KLoSA |

CHARLS |

CLHLS |

IFLS |

IHDS |

||||||||

| ADL limitations commonly available across surveys: Difficulty in dressing or bathing? | ||||||||||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Total | 108,385 | 15,762 | 244,626 | 22,585 | 54,298 | 2425 | 69,210 | 3325 | 59,943 | 19,320 | 18,363 | 471 | 93,580 | 2357 |

| Age | ||||||||||||||

| 45–49 | 20,836 (91.3%) | 1733 (8.7%) | 35,998 (97.7%) | 855 (2.3%) | 2924 (99.4%) | 17 (0.6%) | 11,001 (99.0%) | 135 (1.0%) | – | – | 4845 (99.4%) | 29 (0.6%) | 22,621 (99.3%) | 127 (0.7%) |

| 50–54 | 19,506 (90.4%) | 1874 (9.6%) | 37,805 (97.0%) | 1153 (3.0%) | 7108 (99.5%) | 37 (0.5%) | 12,290 (98.5%) | 213 (1.5%) | – | – | 3985 (99.2%) | 35 (0.8%) | 18,645 (99.0%) | 166 (1.0%) |

| 55–59 | 17,438 (87.9%) | 2098 (12.1%) | 37,313 (96.5%) | 1339 (3.5%) | 8922 (99.2%) | 78 (0.8%) | 12,489 (97.7%) | 334 (2.3%) | – | – | 3018 (98.7%) | 41 (1.3%) | 14,820 (98.6%) | 180 (1.4%) |

| 60–64 | 14,918 (86.2%) | 2062 (13.8%) | 36,514 (95.6%) | 1692 (4.4%) | 8231 (98.8%) | 110 (1.2%) | 12,343 (96.3%) | 498 (3.7%) | – | – | 2274 (98.1%) | 46 (1.9%) | 13,136 (97.5%) | 295 (2.5%) |

| 65–69 | 12,678 (87.1%) | 1786 (12.9%) | 33,137 (93.4%) | 2341 (6.6%) | 8095 (97.9%) | 188 (2.1%) | 9029 (95.1%) | 512 (4.9%) | 6822 (96.9%) | 192 (3.1%) | 1708 (96.6%) | 64 (3.4%) | 9895 (96.6%) | 324 (3.4%) |

| 70–74 | 9808 (83.8%) | 1770 (16.2%) | 26,017 (90.2%) | 2833 (9.8%) | 7538 (95.7%) | 348 (4.3%) | 5858 (92.7%) | 486 (7.3%) | 8244 (95.3%) | 398 (4.7%) | 1246 (94.6%) | 70 (5.4%) | 7035 (94.6%) | 400 (5.4%) |

| 75+ | 13,201 (72.1%) | 4439 (27.9%) | 37,842 (75.4%) | 12,372 (24.6%) | 11,480 (87.8%) | 1647 (12.2%) | 6200 (82.9%) | 1147 (17.1%) | 44,877 (86.0%) | 18,730 (14.0%) | 1287 (88.1%) | 186 (11.9%) | 7428 (88.7%) | 865 (11.3%) |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 49,966 (85.2%) | 7805 (14.8%) | 116,060 (92.9%) | 8807 (7.1%) | 23,447 (97.4%) | 951 (2.6%) | 33,662 (95.6%) | 1488 (4.4%) | 28,240 (93.9%) | 6068 (6.1%) | 8687 (98.2%) | 174 (1.8%) | 46,984 (97.7%) | 1049 (2.3%) |

| Female | 58,419 (86.8%) | 7957 (13.2%) | 128,566 (90.3%) | 13,778 (9.7%) | 30,851 (96.7%) | 1474 (3.3%) | 35,548 (95.0%) | 1837 (5.0%) | 31,703 (91.2%) | 13,252 (8.8%) | 9676 (97.3%) | 297 (2.7%) | 46,596 (96.9%) | 1308 (3.1%) |

| Education | ||||||||||||||

| High | 25,749 (93.1%) | 1746 (6.9%) | 35,042 (95.2%) | 1881 (4.8%) | 5641 (98.0%) | 97 (1.2%) | 1447 (98.2%) | 31 (1.8%) | 1309 (94.6%) | 308 (5.4%) | 1381 (99.2%) | 13 (0.8%) | 5404 (98.8%) | 54 (1.2%) |

| Middle | 44,528 (87.2%) | 5955 (12.8%) | 49,742 (93.0%) | 4033 (7.0%) | 16,824 (98.8%) | 299 (1.2%) | 7298 (97.6%) | 172 (2.4%) | 2340 (94.0%) | 499 (6.0%) | 2493 (98.2%) | 46 (1.8%) | 11,264 (98.3%) | 172 (1.7%) |

| Low | 38,108 (81.0%) | 8061 (19.0%) | 20,763 (83.4%) | 4132 (16.6%) | 31,833 (95.2%) | 2029 (4.8%) | 60,465 (94.9%) | 3122 (5.1%) | 56,294 (92.3%) | 18,513 (7.7%) | 14,489 (97.5%) | 412 (2.5%) | 76,912 (97.1%) | 2131 (2.9%) |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||||

| Married | 78,545 (88.3%) | 9207 (11.7%) | 186,854 (93.9%) | 11,964 (6.1%) | 42,208 (98.0%) | 1276 (2.0%) | 60,179 (96.4%) | 2399 (3.6%) | 23,469 (94.9%) | 2804 (5.1%) | 13,996 (98.4%) | 240 (1.6%) | 72,509 (98.2%) | 1242 (1.8%) |

| Not married | 23,368 (78.7%) | 5462 (21.3%) | 15,309 (93.2%) | 1117 (6.8%) | 435 (95.1%) | 27 (4.9%) | 497 (91.6%) | 49 (8.4%) | 669 (94.8%) | 116 (5.2%) | 268 (97.8%) | 7 (2.2%) | 855 (95.5%) | 40 (4.5%) |

| Other | 6472 (84.8%) | 1093 (15.2%) | 42,463 (81.6%) | 9504 (18.4%) | 11,655 (93.0%) | 1122 (7.0%) | 8534 (89.0%) | 877 (11.0%) | 35,805 (88.5%) | 16,400 (11.5%) | 4099 (95.2%) | 224 (4.8%) | 20,216 (94.5%) | 1075 (5.5%) |

| Residential area | ||||||||||||||

| Urban | 88,654 (86.1%) | 12,724 (13.9%) | – | – | 41,111 (97.3%) | 1738 (2.7%) | 27,873 (95.6%) | 1270 (4.4%) | 26,514 (91.2%) | 10,267 (8.8%) | 9904 (97.8%) | 243 (2.2%) | 30,889 (97.6%) | 696 (2.4%) |

| Rural | 19,731 (85.6%) | 3038 (14.4%) | – | – | 13,187 (95.9%) | 687 (4.1%) | 41,337 (95.1%) | 2055 (4.9%) | 33,429 (93.4%) | 9053 (6.6%) | 8459 (97.7%) | 228 (2.3%) | 62,691 (97.2%) | 1661 (2.8%) |

Note: ADL = Activities of daily living, HILDA = The Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia, CSLC = Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions, KLoSA = Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging, CHARLS = China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, CLHLS = The Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey, IFLS = The Indonesia Family Life Survey, IHDS = India Human Development Survey, LASI = Longitudinal Ageing Study in India. All surveys include dressing and bathing as ADL except for CSLC (difficulty in activities of daily living) and IHDS (dressing only).

Trends in age-standardized prevalence of functional limitations

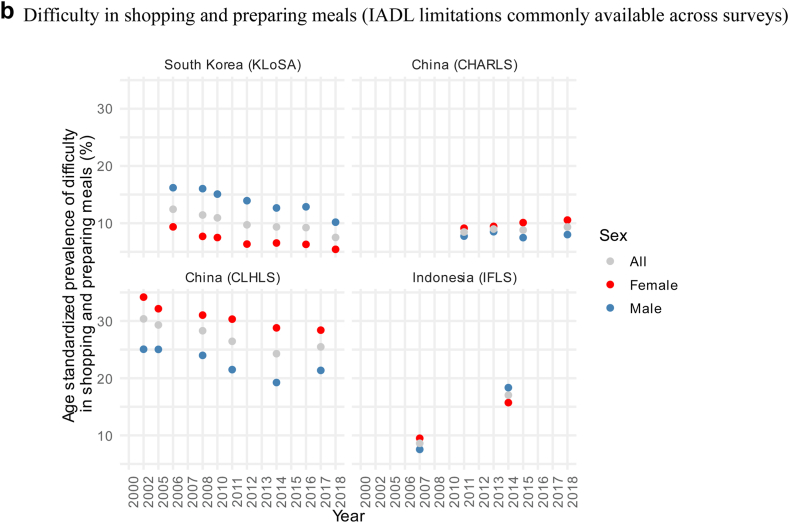

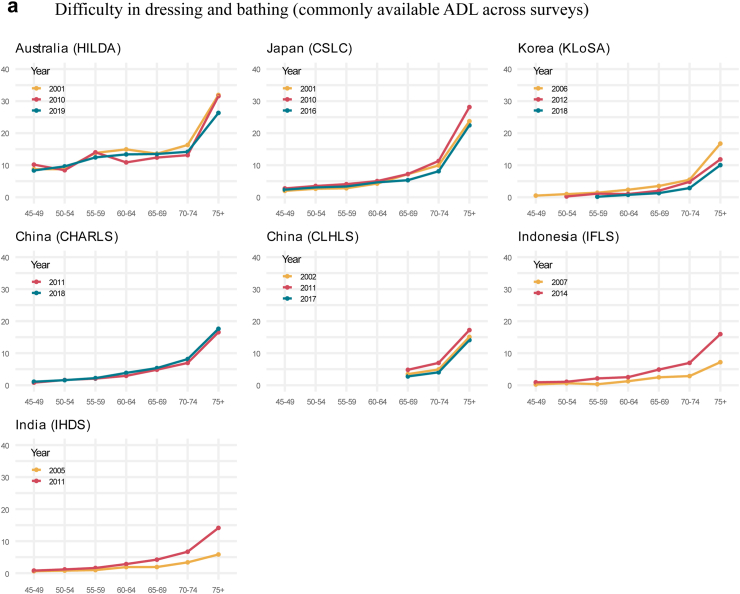

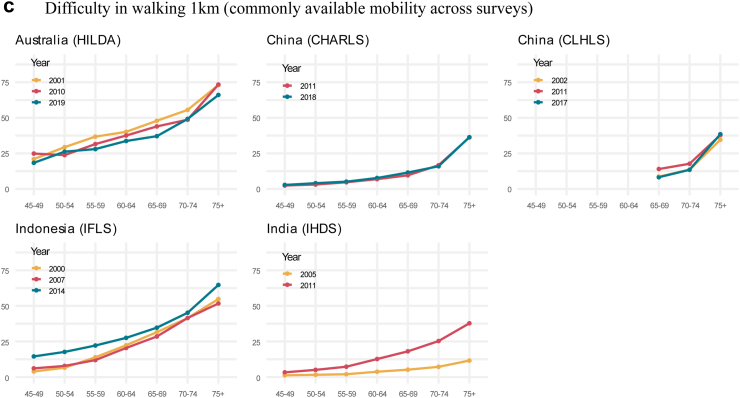

Fig. 2 reports age-standardized prevalence of ADL limitations, IADL limitations, and mobility limitations, that were available across all surveys, for the years between 2001 and 2019. We report average annual changes of the age-standardized prevalence obtained from a simple comparison of the point estimates in the first and last year of each survey. In general, prevalence of ADL limitations appears to be declining in Japan and South Korea, consistent with previous work, even with more updated datasets. Prevalence of ADL limitations in Australia did not show a clear trend but fluctuated between 12·0% and 14·9%. The prevalence of ADL limitations declined in South Korea by an average of 0·2% per year from 2006 to 2018. The prevalence of ADL limitations in Japan did not exhibit any significant trend until 2010 but then declined by an average of 0·4% per year from 2010 to 2016. Similarly, IADL limitation prevalence decreased by an average of 0·4% per year between 2006 and 2018 in South Korea and mobility limitation prevalence decreased by an average of 0·4% annually between 2001 and 2019 in Australia. Although there is a gap in the prevalence of IADLs between men and women (with higher rates among women), it is consistent with the pattern observed in Table 2, and both sexes show largely similar decreasing trends.

Fig. 2.

Age-standardized prevalence of functional limitations by sex. (a) Difficulty in dressing and bathing (ADL limitations commonly available across surveys). (b) Difficulty in shopping and preparing meals (IADL limitations commonly available across surveys). (c) Difficulty in walking 1 km (mobility limitation commonly available across surveys). Note: Population was adjusted using 2020 UN population data, ADL = Activities of daily living, IADL = instrumental activities of daily living. HILDA = The Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia, CSLC = Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions, KLoSA = Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging, CHARLS = China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, CLHLS = The Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey, IFLS = The Indonesia Family Life Survey, IHDS = India Human Development Survey. Those aged 65 years and above. Due to the sample availability, age-standardized prevalence for KLoSA is based on those aged 55 years and above and CLHLS is based on those aged 65 years and above.

In China, evidence from CHARLS data shows no change for ADL and IADL limitations. In contrast, in CLHLS data, which comprises respondents aged over 65 years suggested fluctuations in the prevalence of ADL limitations between 2002 and 2017 and a decline in the prevalence of IADL by an average of 0·3% per year. Estimates based on data from CHARLS suggested an increase in the prevalence of mobility limitations while estimates based on CLHLS data showed no change over time. The prevalence of these functional limitations was higher among women throughout the observed period but there was no apparent difference in the annual rate of change over time between men and women.

Conversely, Indonesia and India experienced an increase in the prevalence of ADL limitations annually by an average of 0·3% in Indonesia and 0·4% in India, and in mobility limitations by an average of 0·6% and 1·4%, respectively, although only a limited set of data points are available. In Indonesia, IADL limitations increased by an average of 1·2% per year between 2007 and 2014. Prevalence of ADL and mobility limitations among women rose more sharply than men. In Indonesia, prevalence of ADL limitations increased by an average of 0·4% per year for women compared to 0·3% per year for men. In India, ADL limitations rose by an average of 0·5% per year for women and 0·3% per year for men. Similarly, prevalence of mobility limitations increased by an average of 0·7% per year for women and 0·6% for men in Indonesia, while in India, it increased by an average of 1·7% per year for women and 1.0% per year for men. Age-standardized prevalence of other indicators of functional limitations are reported in Appendix Fig. S3.

Prevalence of functional limitations by age

The prevalence of functional limitations varied considerably across the different age groups. Fig. 3 presents this variance in prevalence by age for selected years. Consistent with the trends observed in Fig. 2, Japan and South Korea exhibit a steady decline in ADL limitation prevalence, particularly among those aged 60 and older. Likewise, declines in the prevalence of IADL and mobility were observed in South Korea and Australia, across all age groups.

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of difficulty in physical functioning by age in selected survey years. (a) Difficulty in dressing and bathing (commonly available ADL across surveys). (b) Difficulty in shopping and preparing meals (commonly available IADL across surveys). (c) Difficulty in walking 1 km (commonly available mobility across surveys). Note: ADL = Activities of daily living, IADL = instrumental activities of daily living. HILDA = The Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia, CSLC = Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions, KLoSA = Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging, CHARLS = China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, CLHLS = The Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey, IFLS = The Indonesia Family Life Survey, IHDS = India Human Development Survey. Analysis based on data from HILDA, CLSC, KLoSA, CHARLS, IFLS, and IHDS. X axis is age group and y axis is prevalence of functional limitations (%). All prevalence were weighted according to survey weight.

In China, there were inconsistencies in the results between CHARLS and CLHLS. Estimates based on CHARLS data suggested that the prevalence of functional limitations remained largely unchanged between 2011 and 2018 across ages, whereas estimates based on CLHLS data indicated declining prevalence of functional limitations among people 65 years and over the same period.

Data from Indonesia and India, on the other hand, show increased prevalence of ADL limitations starting around the ages of 55–64 years, with even higher prevalence among older age groups. A similar pattern was observed for prevalence in mobility limitations in India. Prevalence in IADL and mobility limitations in Indonesia also increased over time, with the increase occurring across all age groups.

These results indicate that the average age of functional limitation onset is at increasingly older ages in Japan and South Korea over time; however, the reverse appears to be true for India and Indonesia, with onset occurring at younger ages over time. Information on prevalence of additional functional limitation indicators are reported in Appendix Fig. S4.

Sensitivity analyses

Multivariate linear probability models were applied to assess whether the observed prevalence patterns and changes over time were affected once birth cohort effects were controlled for, along with other socioeconomic and demographic variables. Regression coefficients continued to indicate a declining trend in functional limitations in Australia, Japan, and South Korea, and increasing trends in Indonesia and India. In sum, the main conclusions remained generally unaffected by the inclusion of these covariates (Appendix Fig. S5). Further sensitivity analyses using different measures of severity of functional limitations revealed that accounting for severity did not affect the main conclusions (Appendix Figs. S7 and S8). Lastly, we compared our results and estimates from data with imputed values for missing data and found that the main conclusions did not change (Appendix Figs. S9 and S10).

Discussion

This study highlights, in a comparative framework, several important trends in the prevalence of functional limitations among middle-aged and older adults within and across countries in the Asia-Pacific region over the last two decades. Although population ageing is a common challenge for most countries worldwide, this study demonstrated differences in trends in ageing-related functional limitations across countries and socioeconomic and demographic groups.

Australia, Japan, and South Korea generally show decreases over time in the prevalence of functional limitations, even after adjusting for birth cohorts and other socioeconomic and demographic factors. This is consistent with a large body of studies from other HICs including US and European countries.8,9 Our findings therefore suggest that more recent data from South Korea and Japan supports the continuing decline in functional limitations noted in earlier decades.12,13 In contrast, the prevalence of functional limitations in Indonesia and India has risen over time. While this conclusion is based on longitudinal data that were available only at two points in time, evidence from other sources, such as prevalence of disability based on cross-sectional surveys conducted by India's National Sample Survey Organization over 2001–2018, and various cross-sectional surveys and census data for Indonesia supports these conclusions.26,27 Although comparable evidence from low- and middle-income countries is limited, these findings are largely aligned with evidence from Mexico and Philippines.28,29 The different prevalence trends observed in the CHARLS and CLHLS datasets could be attributed to differences in sample population characteristics. While trends in functional limitations observed from CHARLS capture the health profiles of general population of China over a wider age range, CLHLS provides information on trends in functional limitation prevalence among oldest-old population of China; functional limitations among people aged 65 years and above, however, might be affected by sample characteristics including sampling people living in proximity to the oldest old group.

Our analysis not only indicates the direction of the trends but also identified key age groups driving these trends. The observed trends in the prevalence of functional limitations are primarily due to the changes within the population aged 60 and above, particularly for ADL limitations. In Japan and Korea, the prevalence of ADL limitations remained consistently low among middle aged adults over the years, with declines in prevalence among older adults aged 60 years and above. These findings may indicate a postponement of functional limitations to older ages in these countries as in European settings.10 Nevertheless, younger adults also seem to have experienced increase in prevalence of mobility limitations in India and Indonesia, indicating that the challenges of functional limitations may extend beyond the older adults in these countries. These observations align with the growing burden of NCDs and their contributions to DALYs within the younger demographics in these countries,4 pointing to an urgent need to develop health strategies targeting prevention and effective management of chronic conditions among younger age-groups.

These differential trends observed across countries cannot be adequately explained without considering the variations in countries’ performance in effective prevention, treatment, and management of health conditions, especially NCDs. Access to these health services have improved significantly in the last two decades in Australia, Japan, and South Korea.30 A reduction in the prevalence of functional limitations observed among the older adults in high-income countries may have resulted from improvements in individual health behaviors and lifestyle, as well as improvements in early diagnosis, healthcare treatment, and post-care rehabilitation which limit functional decline and potentially postpone onset of functional limitations to older ages. In the case of Indonesia and India, growing prevalence of functional limitations likely reflects an increasing burden of NCDs, compounded by limited access to timely and high-quality health services, especially primary care. Additionally, significant reductions in premature mortality associated with the improvement in access to life saving interventions may also play a role.31 This improvement would likely have resulted in an increase in a survival rate of people with functional limitations.

Further, our analyses highlight socioeconomic and demographic disparities in functional limitations. In line with existing international studies,32 our study identified higher education attainment was negatively associated with functional limitations, which we used as a proxy of socioeconomic status of respondents in all countries in our study. Our findings also indicated women have higher prevalence of mobility limitations than men even after adjusting for covariates, which generally applicable to ADL limitations with exceptions of Australia and South Korea.33 The sex difference was more pronounced in MICs compared to HICs, and appeared to be widening over time in India and Indonesia. One of the reasons for this sex difference could lie in socioeconomic disadvantages faced by women in these countries, including lower earnings, limited access to healthcare, and lower education attainment which are likely to have compounded their risk of developing functional limitations.33 It should be emphasized that functional limitations in turn is likely to further disadvantage them by imposing additional social and economic burdens associated with healthcare costs and productivity losses. Therefore, there is a pressing need for public policy to address these disparities by promoting gender equity in healthcare, enhancing education and work opportunity among women, and implementing financial support to vulnerable ageing populations, especially in India and Indonesia.

Functional limitations are an important determinant of long-term care demands. With the projected growth of future older adult populations in both HICs and LMICs, the demand for long-term care is expected to increase significantly over time. If current trends in declines in functional limitations among older adults hold up in future decades in the HIC context, the growth of expenditures associated with long-term care may not be as concerning. However, our study also provided insights on the pattern of functional limitations among older populations in Indonesia and India, and here the demand for long-term care is likely to rise sharply as their populations age. Along with population ageing then, increasing caregiving burdens and change in family structures (as families become smaller) will pose further pressures on maintaining current family support systems in these countries.34,35 Policymakers in these countries will need to focus on strengthening long-term care and implementing prevention measures to curtail the projected increases in the burden of functional limitations in their populations.

Though the prevalence estimates reported above are based on the best available data from selected countries in the Asia-Pacific region, the study has several limitations. For instance, absolute levels of reported functional limitation prevalence estimates across countries could not be compared due to differences in sampling designs and lack of harmonization of survey instruments. In addition, all data are self-reported and may capture functional limitations at different level of severity if respondents’ perceptions about their condition are influenced by cultural and economic factors specific to countries. Although the prevalence of functional limitations was tracked over two decades, only two points of time were used for intertemporal comparisons in Indonesia and India due to limited data availability. Further, this study used household surveys that did not include residents in institutional care such as aged care facilities and hospitals. While representative of the general population, these exclusions are likely to result in a healthier than average sample of respondents relative to the general population, and thus, the prevalence obtained in this research might be underestimated. Lastly, this study did not include psychological and cognitive dimensions of functional limitations due to lack of data, and these too are important determinants of healthcare needs.

Conclusion

This population-based study provided evidence of disparity in the trends of functional limitations of middle-aged and older adults between HICs and MICs and unequal distribution of functional limitations across socioeconomic and demographic groups in the Asia-Pacific region. These findings underscore the importance of strengthening long-term care system to cope with increasing demands with the growth of older adult population, particularly in MICs, as well as upscaling programs for prevention and management of noncommunicable diseases that are a major driver of functional limitations. Health trajectories in older adults should be continuously monitored and considered when projecting future health and economic burdens.

Contributors

MI and AM developed the research questions and designed the study. MI conducted data analysis and produced the initial draft of the manuscript with inputs provided by SK, TL, and VF. MI had access to, and verified, the raw data. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. MI and AM had final responsibility to submit for publication.

Data sharing statement

Data will not be shared by the authors as they were collected by third party institutions. The survey datasets used can be downloaded from the data portals of each survey following registration. Data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request.

Declaration of interests

None.

Acknowledgements

We obtained approval from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan (MHLW) to utilize de-identifiable data of CSLC in accordance with Article 36 of the Statistics Act of Japan. The results obtained using CSLC were independently created and processed by the authors, and these differ from those produced and released by MHLW.

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT-4o to enhance the readability and proofread the English text. After using this service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the contents of the publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2024.101267.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.World Bank Group World Bank open data. 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/ Available from:

- 2.United Nations . 2022. Economic and social commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). Asia-pacific report on population ageing 2022: trends, policies and good practices regarding older persons and population ageing (ST/ESCAP/3041) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong J.H. Disability incidence and functional decline among older adults with major chronic diseases. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):323. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1348-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHEM) IHME, University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 2024. GDB results.https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verbrugge L.M., Jette A.M. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falck R.S., Percival A.G., Tai D., Davis J.C. International depiction of the cost of functional independence limitations among older adults living in the community: a systematic review and cost-of-impairment study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):815. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03466-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Population Prospects; 2024. https://population.un.org/wpp/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuller-Thomson E., Ferreirinha J., Ahlin K.M. Temporal trends (from 2008 to 2017) in functional limitations and limitations in activities of daily living: findings from a nationally representative sample of 5.4 million older Americans. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3) doi: 10.3390/ijerph20032665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahrenfeldt L.J., Lindahl-Jacobsen R., Rizzi S., Thinggaard M., Christensen K., Vaupel J.W. Comparison of cognitive and physical functioning of Europeans in 2004-05 and 2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(5):1518–1528. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Timmermans E.J., Hoogendijk E.O., Broese van Groenou M.I., et al. Trends across 20 years in multiple indicators of functioning among older adults in the Netherlands. Eur J Publ Health. 2019;29(6):1096–1102. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckz065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatterji S., Byles J., Cutler D., Seeman T., Verdes E. Health, functioning, and disability in older adults--present status and future implications. Lancet. 2015;385(9967):563–575. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61462-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jang S.N., Cho S.I., Kawachi I. Is socioeconomic disparity in disability improving among Korean elders? Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(2):282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishii S., Ogawa S., Akishita M. The state of health in older adults in Japan: trends in disability, chronic medical conditions and mortality. PLoS One. 2015;10(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu N., Cadilhac D.A., Kilkenny M.F., Liang Y. Changes in the prevalence of chronic disability in China: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Publ Health. 2020;185:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding H., Wang K., Li Y., Zhao X. Trends in disability in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living among Chinese older adults from 2011 to 2018. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2024;36(1):27. doi: 10.1007/s40520-023-02690-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo Y., Wang T., Ge T., Jiang Q. Prevalence of self-care disability among older adults in China. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):775. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03412-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrit Mn M., Ruest M., Mahal A. World Bank; Suva, Fiji: 2024. Mo bulabula, bula balavu: health sector review and action plan for Fiji. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, GENERAL RELEASE 22 (waves 1-22) ADA Dataverse; 2024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Health LaW Comprehensive survey of living conditions 2024. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/20-21.html Available from:

- 20.Korea Employment Information Service . 2024. Korean longitudinal study of ageing.https://survey.keis.or.kr/eng/klosa/klosa01.jsp Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y., Hu Y., Smith J.P., Strauss J., Yang G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS) Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):61–68. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng Y., Vaupel J., Xiao Z., Liu Y., Zhang C. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2017. Chinese longitudinal Healthy longevity survey (CLHLS), 1998-2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss J., Witoelar F., Sikoki B. 2016. The fifth wave of the Indonesia family life survey (IFLS5): overview and field report. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desai S., Vanneman R., India Human Development Survey-II (IHDS-II), 2011-12 . 2018. Inter-university consortium for political and social research [distributor] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The longitudinal ageing study in India 2017-18 - national report. International Institute for Population Sciences, National Programme for Health Care of Elderly, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Chan School of Public Health, and the University of Southern California; Harvard T. H: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Statistical Office . Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation; 2018. Persons with disabilities in India. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Australia Indonesia Partnership for Economic Governance . 2017. Disability in Indonesia: what can we learn from the data? [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cruz G.T., Cruz C.J.P., Saito Y. Is there compression or expansion of morbidity in the Philippines? Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2022;22(7):511–515. doi: 10.1111/ggi.14398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Payne C.F., Wong R. Expansion of disability across successive Mexican birth cohorts: a longitudinal modelling analysis of birth cohorts born 10 years apart. J Epidemiol Community. 2019;73(10):900–905. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-212245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fullman N., Yearwood J., Abay S.M., et al. Measuring performance on the healthcare access and quality index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2018;391(10136):2236–2271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30994-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization . 2024. Global health observatory.https://www.who.int/data/gho Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ni Y., Zhou Y., Kivimäki M., et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in physical, psychological, and cognitive multimorbidity in middle-aged and older adults in 33 countries: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023;4(11):e618–e628. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bloomberg M., Dugravot A., Landré B., et al. Sex differences in functional limitations and the role of socioeconomic factors: a multi-cohort analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(12):e780–e790. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00249-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harbishettar V., Gowda M., Tenagi S., Chandra M. Regulation of long-term care homes for older adults in India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2021;43(5_suppl):S88–S96. doi: 10.1177/02537176211021785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asian Development Bank . 2021. Country diagnostic study on long-term care in Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.