Pressures on poor countries to ban the insecticide DDT because of fears that its use would harm the environment have led to a resurgence of malaria in the world, yet the environmental impact of its use are “negligible,” a study published this week has said.

The study shows that after malaria was eradicated in wealthy countries and DDT was banned in those places, poor countries were pressured by health and donor agencies and environmental groups to stop using DDT spraying programmes. The agencies feared that they would harm the environment and adversely affect human health.

But these fears were unsubstantiated, the study's authors believe. “No scientific peer reviewed study has ever replicated any case of negative human health impacts from DDT,” said Dr Roger Bate, media and development director for the International Policy Network and joint author of the study with Richard Tren, director of economic policy at the non-governmental organisation Africa Fighting Malaria.

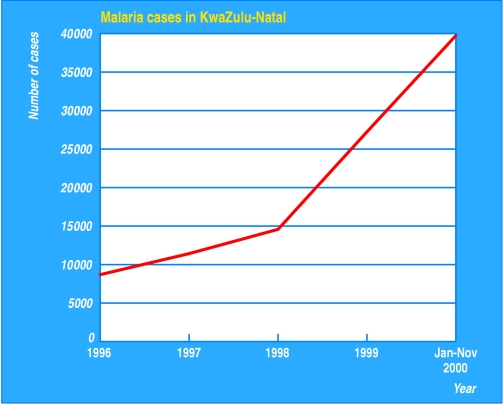

A surge in malaria in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa coincided with the withdrawal of DDT from malaria control programmes in 1996. Synthetic pyrethroids were used in its place. But some mosquitoes, most notably the Anopheles funestus, which is a highly efficient vector of the disease, had developed resistance to these chemicals, and when it returned to South Africa in the second half of the 1990s, malaria rates began to increase.