Abstract

Although alveolar hyperoxia exacerbates lung injury, clinical studies have failed to demonstrate the beneficial effects of lowering the fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Atelectasis, which is commonly observed in ARDS, not only leads to hypoxemia but also contributes to lung injury through hypoxia-induced alveolar tissue inflammation. Therefore, it is possible that excessively low FIO2 may enhance hypoxia-induced inflammation in atelectasis, and raising FIO2 to an appropriate level may be a reasonable strategy for its mitigation. In this study, we investigated the effects of different FIO2 levels on alveolar tissue hypoxia and injury in a mechanically ventilated rat model of experimental ARDS with atelectasis. Rats were intratracheally injected with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to establish an ARDS model. They were allocated to the low, moderate, and high FIO2 groups with FIO2 of 30, 60, and 100%, respectively, a day after LPS injection. All groups were mechanically ventilated with an 8 mL/kg tidal volume and zero end-expiratory pressure to induce dorsal atelectatic regions. Arterial blood gas analysis was performed every 2 h. After six hours of mechanical ventilation, the rats were euthanized, and blood, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and lung tissues were collected and analyzed. Another set of animals was used for pimonidazole staining of the lung tissues to detect the hypoxic region. Lung mechanics, ratios of partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) to FIO2, and partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide were not significantly different among the three groups, although PaO2 changed with FIO2. The dorsal lung tissues were positively stained with pimonidazole regardless of FIO2, and the HIF-1α concentrations were not significantly different among the three groups, indicating that raising FIO2 could not rescue alveolar tissue hypoxia. Moreover, changes in FIO2 did not significantly affect lung injury or inflammation. In contrast, hypoxemia observed in the low FIO2 group caused injury to organs other than the lungs. Raising FIO2 levels did not attenuate tissue hypoxia, inflammation, or injury in the atelectatic lung region in experimental ARDS. Our results indicate that raising FIO2 levels to attenuate atelectasis-induced lung injury cannot be rationalized.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-83992-2.

Keywords: Oxygen, Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Atelectasis, Alveolar hypoxia, Hypoxia-induced inflammation

Subject terms: Preclinical research, Translational research, Acute inflammation, Respiratory distress syndrome

Background

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is characterized by profound pulmonary edema and alveolar collapse1. Moreover, positive pressure ventilation suppressing spontaneous breathing to rescue patients from respiratory failure further augments dorsal alveolar collapse and atelectasis formation2. It has been reported that atelectasis itself enhances lung injury3–6, and alveolar hypoxia is the primary mechanism underlying atelectasis-induced lung inflammation and tissue injury4. Hypoxia enhances chemokine secretion from alveolar epithelial cells via NF-kb activation4 and neutrophilic inflammation7. Mitigating alveolar hypoxia is expected to protect lung tissue from ARDS with atelectasis.

The following two approaches may help attenuate alveolar hypoxia. First, the open lung approach, involving alveolar recruitment and the application of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), can improve the reach of ventilatory gas to the alveoli by reducing atelectasis. Second, increasing the inspired oxygen concentration may enhance oxygenation of the atelectatic lung regions through oxygen diffusion. We previously demonstrated that the open lung approach has a protective effect against experimental ARDS by decreasing the atelectatic lung area5. Furthermore, it has been reported that mechanical ventilation with increased inspired oxygen levels can mitigate atelectasis-induced lung injury in animals without ARDS8. However, the effects of raising fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) on atelectatic lung tissue oxygen tension and injury in subjects with ARDS have not yet been evaluated.

Alveolar hyperoxia has been demonstrated to exacerbate lung tissue injury9,10. However, randomized control trials have not shown the advantageous effects of decreasing the FIO2 in critically ill patients including those with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)11–14. One possible explanation for this is that excessively low FIO2 levels may also be detrimental for patients with atelectasis by enhancing hypoxia-induced inflammation. Consequently, raising FIO2 to an appropriate level may mitigate atelectasis-induced lung tissue hypoxia and injury, while preventing hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Clarifying the biological effects of FIO2 in ARDS with atelectasis will facilitate better future clinical studies.

In this study, we evaluated the effects of three different FIO2 levels on lung tissue hypoxia, inflammation, and injury in a mechanically ventilated rat model of experimental ARDS with atelectasis. We also evaluated the effects of FIO2 on injuries to remote organs other than the lungs.

Methods

Animal experiments

All the animal experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Yokohama City University, performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and reported in accordance with ARRIVE guideline. Eight-to-nine-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats were used for the animal experiments. They were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum.

On the first day, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) were intratracheally administered to the rats, as previously described5. The trachea was exposed through a small incision in front of the neck under general anesthesia with intraperitoneal ketamine and xylazine administration. Thereafter, 300 µL of LPS solution in PBS (5 mg/mL) was intratracheally administered with air. Oxygen was administered (0.5 L/min) after intratracheal instillation until recovery from anesthesia on a warming board. The experimenter of LPS instillation was blinded from the group allocation.

The rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal ketamine and xylazine 24 h after LPS instillation. Thereafter, an intravenous catheter was inserted through the left femoral vein, and an arterial catheter was placed through the right carotid artery. General anesthesia was maintained with propofol infusion (5 mg/h) via an intravenous line. Subsequently, the rats were tracheostomized, and mechanical ventilation was initiated. Mechanical ventilation was performed with a small animal ventilator (SN-480-7, Shinano Seisakusho, Tokyo, Japan), and pancuronium bromide was administered to prevent conflict with the ventilator. The initial settings for mechanical ventilation were as follows: FIO2, 0.21; tidal volume (TV), 8 mL/kg; frequency, 80/min; and PEEP, 4 cmH2O. Thereafter, a recruitment maneuver with 30 cmH2O for 10 s was performed three times to ensure consistent lung aeration across all animals.

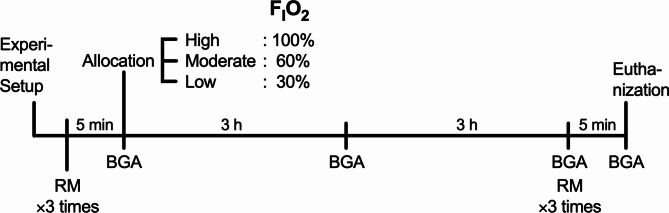

Thereafter, the rats were randomly allocated into three groups according to the FIO2: low FIO2 Group with O2 concentration of 30%, moderate FIO2 Group with O2 concentration of 60%, and high FIO2 Group with O2 concentration of 100% (Fig. 1). The mechanical ventilation settings, except for the FIO2, were the same for all groups: TV, 8 mL/kg; frequency, 80/min; and zero end-expiratory pressure (ZEEP).

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of experimental design. BGA, blood gas analysis; FIO2, fraction of inspiratory oxygen; RM, recruitment maneuver.

Blood pressure and airway pressure were monitored using a medical bedside monitor (BSM-8500, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) and recorded every hour after group allocation. Dynamic driving pressure was calculated as peak inspiratory pressure minus PEEP. Our previous analysis5 revealed that the inspiratory flow generated by the ventilator is nearly zero at the end-inspiratory phase. Therefore, the calculated dynamic driving pressure was assumed to be almost equal to the static driving pressure.

Arterial blood gas analysis was performed before and every 3 h after group allocation. After six hours of mechanical ventilation, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was collected by lavaging the right lung with two separate 4-ml aliquots of PBS containing 0.6 mM EDTA. The right lung was harvested, frozen, and stored for subsequent RNA and protein extraction. The left lung was fixed by intratracheal instillation of 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 20 cmH2O pressure and embedded in paraffin for histopathological examination.

The primary outcome of the study was set as protein concentration of BALF. Based on the pilot data, we estimated the standard deviation and meaningful difference in protein concentration in BALF to be 240 and 500 µg/mL, respectively. The required sample size was determined to be 5 per each group, with an α-level of 0.05 and a power level of 80%.

Computed tomography imaging analysis

A separate group of animals was used for computed tomography (CT) imaging analysis to evaluate regional atelectasis and aerated lung volumes. The rats were euthanized after 3 h of the mechanical ventilation protocol, and their tracheas were ligated at the end-expiratory phase to maintain lung aeration. Immediately afterward, CT images were obtained using a microCT scanner (RIGAKU, Tokyo, Japan). The aerated lung volume was calculated using FIJI ImageJ software15.

Pimonidazole staining

Another set of animals was used for pimonidazole staining of lung tissues to detect the hypoxic region. The experimental protocols were the same as those described above, up to the step of allocating the experimental group. Four hours after group allocation, 18 mg of pimonidazole hydrochloride (HypoxyprobeTM-1; Hypoxyprobe, MA, USA) was injected via an intravenous femoral catheter. After 2 h, the rats were euthanized, and the lungs were fixed with paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin, as described above. The paraffin-embedded lung sections were immunohistochemically stained using an anti-pimonidazole mouse IgG1 monoclonal antibody or rabbit polyclonal antibody and an avidin-biotin complex (ABC) kit (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The positive area of pimonidazole staining was quantified using FIJI ImageJ software15. Briefly, color deconvolution was applied to separate hematoxylin and DAB staining, and the ratio of the DAB-positive area to the total lung tissue area was calculated.

Analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluids

A portion of the collected bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was stained with Samson’s reagent solution, and the white blood cells were counted. The remaining BALF was centrifuged at 2,000 × g, and the supernatants were collected. The total protein concentration in BALF supernatants was quantified using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The cytokine and myeloperoxidase concentrations were measured using commercially available ELISA kits as follows: TNF-α: DY510 (R&D Systems, MN, USA); IL-1β: DY501 (R&D Systems); IL-6: DY506 (R&D Systems); IL-10: DY522 (R&D Systems); CXCL-1: DY515 (R&D Systems); CCL2: DY3144-05 (R&D Systems); RAGE: DY1616 (R&D Systems); ICAM-1: DY583 (R&D Systems).

Protein analysis of lung tissues

The proteins were extracted from the entire right lung tissue homogenized in Radio-Immunoprecipitation Assay buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail. The concentration of HIF-1α was quantified by ELISA (DYC1935-2, R&D Systems), and the value was normalized to the total protein concentration determined by the BCA assay. We measured the HIF-1α concentrations in the lung tissues from the animals in the present study and those from the ARDS rat model ventilated with an open lung approach. The latter tissue samples had been collected in our previous study5.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis

RNA was extracted from lung tissue homogenates using a spin column (FastGene™ RNA Premium Kit, Nippon Genetics, Tokyo, Japan). The extracted RNA was reverse-transcribed using a reverse transcription kit (RevertraAce, Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan). Quantitative PCR was performed using TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) with specific primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (Table 1) under the following conditions 30 s at 95 °C and 40 cycles for 5 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C (CFX96 real time system, Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA)). The expressions of target genes relative to the expression of beta-actin were calculated.

Table 1.

Primers for qPCR.

| Gene | Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α |

Forward Reverse |

5′-CCACCACGCTCTTCTGTCTAC-3′ 5′-GCTTGGTGGTTTGCTACGAC-3′ |

| IL-1β |

Forward Reverse |

5′-TCTCACAGCAGCATCTCGAC-3′ 5′-CATCATCCCACGAGTCACAG-3′ |

| IL-6 |

Forward Reverse |

5′-GGAACAGCTATGAAGTTTCTCTCC-3′ 5′-GGGTGGTATCCTCTGTGAAGTC-3′ |

| IL-10 |

Forward Reverse |

5′-GACAATAACTGCACCCACTTCC-3′ 5′-CAACCCAAGTAACCCTTAAAGTCC-3′ |

| CXCL-1 |

Forward Reverse |

5′-GCACCCAAACCGAAGTCATA-3′ 5′-GCCATCGGTGCAATCTATCT-3′ |

| CCL-2 |

Forward Reverse |

5′-GCTTCTGGGCCTGTTGTTC-3′ 5′-CTGCTGCTGGTGATTCTCTTGT-3′ |

| ACTB |

Forward Reverse |

5′-TGACGTTGACATCCGTAAAGAC-3′ 5′-AGAGCCACCAATCCACACA-3′ |

Histological analysis

Paraffin-embedded left lung sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histopathological scores were evaluated by a pathologist in a blinded manner following previously described methods5.

Analysis of the plasma concentrations of GOT, GPT, creatinine, and cystatin C

The plasma concentrations of GOT, GPT, creatinine and cystatin C were determined using commercially available kits following the manufacturer’s instructions : GOT and GPT: Transaminase CII Test Wako (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan); Creatinine: LabAssay™ Creatinine (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical); cystatin C (MSCTC0, R&D systems).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA) was used for all the statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Longitudinal physiological parameters, arterial blood gas analysis data, and lactate values were analyzed using two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance and post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The concentrations of lung tissue HIF-1α, inflammatory mediators, and liver and kidney injury markers were analyzed using one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance and post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Results

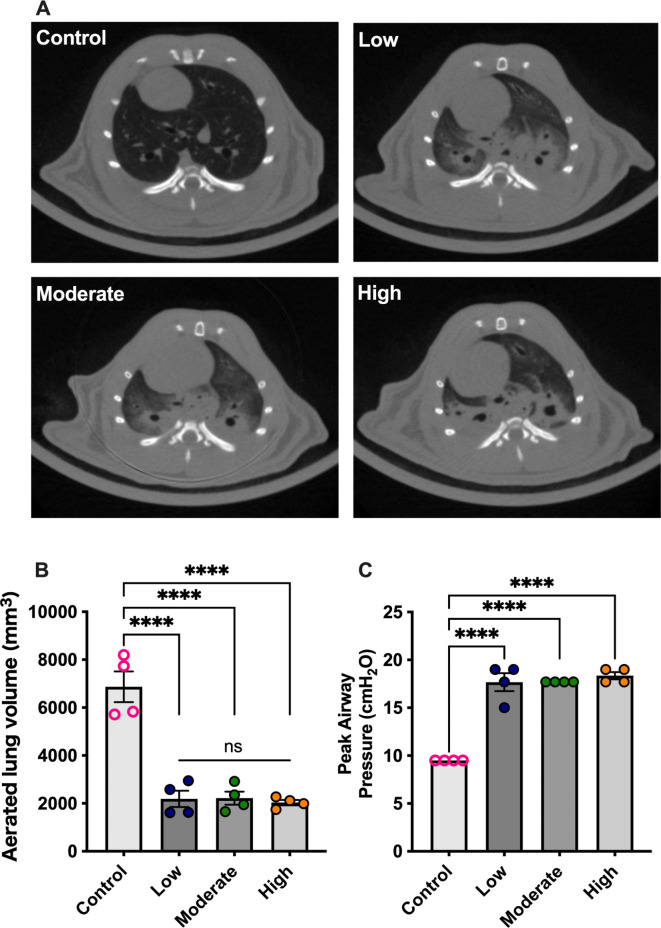

Lung aeration

We evaluated CT images of the lungs held at the end-inspiratory phase during mechanical ventilation. The control group consisted of healthy rats ventilated with a tidal volume of 8 mL/kg of body weight and a PEEP of 4 cm H2O following a recruitment maneuver. In the LPS-induced ARDS model ventilated without PEEP for 3 h exhibited dorsal non-aerated lung regions, regardless of FIO2 levels (Fig. 2A). The aerated lung volumes were significantly higher in the control group (Fig. 2B), despite the lower peak inspiratory pressures in this group (Fig. 2C). However, no significant differences in aerated lung volumes were observed among the low, moderate, and high FIO2 groups.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography analysis. (A) Representative images of lung computed tomography at the T6–T7 vertebral level; and (B) aerated lung volumes at end-inspiratory phase. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Data represent the means ± SEM.

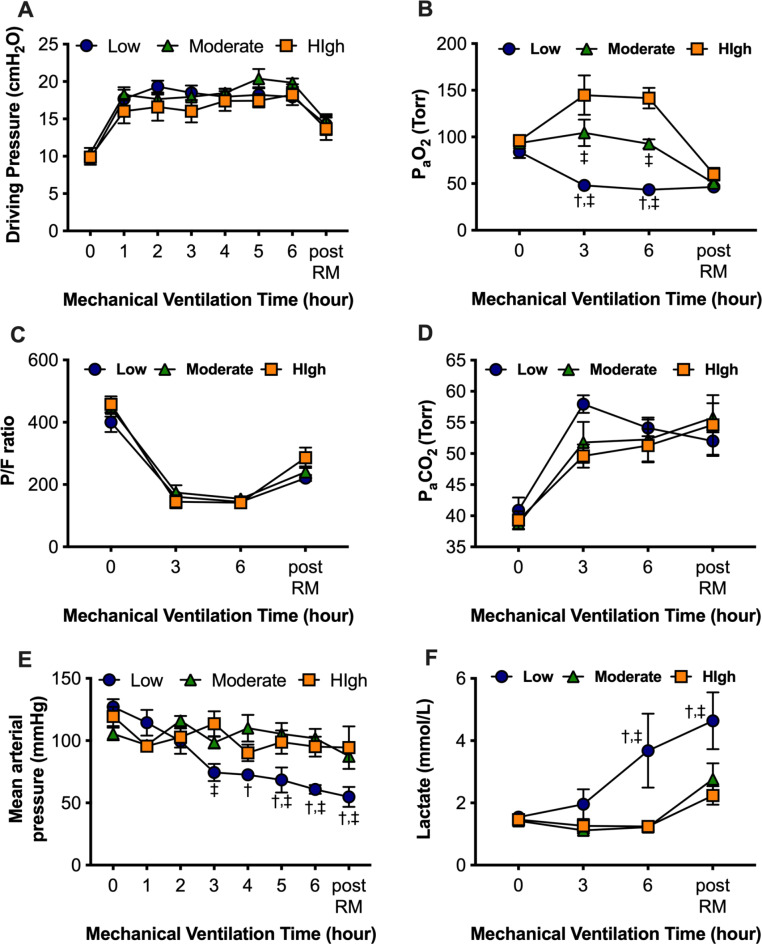

Physiological parameters and arterial blood gas analysis

The physiological parameters and results of the arterial blood gas analysis are shown in Fig. 3. The driving pressures increased after the discontinuation of PEEP application and were not significantly different among the three groups (Fig. 3A). The Partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) changed with the FIO2 (Fig. 3B), while the PaO2/ FIO2 (P/F) ratios (Fig. 3C) and PaCO2 concentrations (Fig. 3D) of the three groups were not significantly different. Collectively, the lung mechanics and respiratory function were not significantly affected by FIO2. In the low FIO2 group, the mean arterial pressure gradually decreased (Fig. 3E), and the lactate concentrations were significantly elevated (Fig. 3F), possibly due to severe hypoxemia.

Fig. 3.

Physiological parameters and arterial blood gas analysis. (A) Dynamic driving pressure. (B) Partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2). (C) PaO2 / fraction of inspiratory oxygen (FIO2) ratio (P/F ratio). (D) Partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2). (E) Mean arterial blood pressure. (F) Blood lactate concentration. †p < 0.05 vs. Moderate FIO2 group, ‡p < 0.05 vs. High FIO2 group. Data represent the means ± SEM.

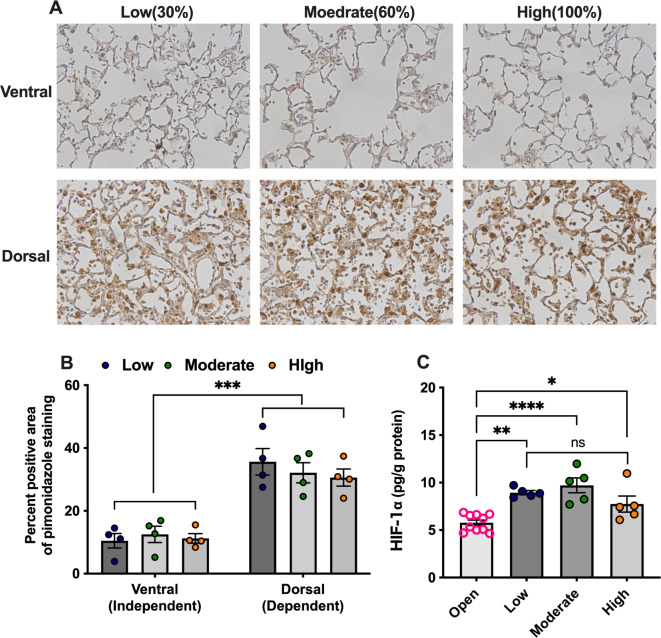

Increased FIO2 did not attenuate atelectasis-induced lung tissue hypoxia

We evaluated the effects of FIO2 on atelectasis-induced alveolar tissue hypoxia. Pimonidazole staining, which indicated hypoxic tissues, showed that dorsal atelectatic alveolar tissues became hypoxic, irrespective of FIO2 (Fig. 4A, B). The HIF-1α concentrations in the lung tissues in all the experimental groups with atelectasis were significantly higher than those in the lung tissue ventilated with the open-lung approach (Fig. 4C). However, FIO2 had non-significant effects on the HIF-1α concentration in the lung tissues with atelectasis (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that elevated FIO2 does not attenuate hypoxia in atelectatic lung tissues.

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of lung tissue hypoxia. (A) Representative images; and (B) percent positive area of pimonidazole staining in lung tissue. (C) hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α protein levels in lung tissue. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Data represent the means ± SEM.

Increased FIO2did not attenuate alveolar inflammation or tissue injury in mechanically-ventilated ARDS lungs with atelectasis

Next, we evaluated the effects of FIO2 on alveolar inflammatory responses and tissue injury in mechanically ventilated animals with ARDS and atelectasis. The mRNA expressions of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, CXCL-1, and CCL-2 in lung tissue were not significantly different among the groups (Fig. 5A). The protein concentrations of these cytokines and chemokines in the BALF were also not significantly different (Fig. 5B). Moreover, there were no significant differences in the BALF leukocyte counts or myeloperoxidase concentrations among the three groups (Fig. 5C, D).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of inflammatory mediators and leukocytes in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALF). (A) mRNA expressions of cytokines and chemokines in the lung tissues. (B) Protein concentrations of cytokines and chemokines in the BALF. (C) White blood cell counts and (D) myeloperoxidases (MPO) in the BALF. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Data represent the means ± SEM.

The concentrations of alveolar tissue injury markers, total protein, ICAM-1, and sRAGE in the BALF were not significantly different among the three groups (Fig. 6A-C). The lung histological scores of both the dorsal and ventral alveolar regions were not significantly different among the three groups (Fig. 6D, E). Collectively, FIO2 did not affect the inflammatory responses or alveolar tissue injury in the animals with ARDS with accompanying atelectasis.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of tissue injury markers in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALF) and histology. (A) total protein concentration; (B) soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE); and (C) intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 in the BALF. (D) Representative images of lung sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (E) Histological scores assessed in a blinded manner. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Data represent the means ± SEM.

In addition, we evaluated lung damage in the LPS-induced ARDS model before the application of the mechanical ventilation protocol and compared it with lung damage in all the animals receiving 6 h of mechanical ventilation without PEEP. The results showed that mechanical ventilation markedly increased protein concentrations and leukocyte counts in the BALF of the LPS-induced ARDS model (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). Histological scores were consistently higher in the dorsal regions both before and after the mechanical ventilation protocol (Supplementary Fig. 1C, D). However, histological damage increased in both the ventral and dorsal areas (Supplementary Fig. 1C, D). These data suggest that atelectasis in the dorsal area, along with mechanical stretching in the ventral area, exacerbates LPS-induced lung injury.

Severe hypoxemia induced damage in organs other than lungs

Finally, we evaluated the effects of FIO2 on organs other than the lungs. The GOT and GPT concentrations were significantly increased in the low FIO2 group (Fig. 7A, B), possibly due to hypoxemia and hypotension. The creatinine concentrations also tended to increase in the low FIO2 group (Fig. 7C), and the cystatin C levels were significantly higher in the low FIO2 group than in the high FIO2 group (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Analysis of liver and kidney injury markers in plasma. (A) glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT); (B) glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT); (C) Creatinine; and (D) Cystatin C in the plasma. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Data represent the means ± SEM.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that increasing FIO2 levels did not rescue tissue hypoxia in the atelectatic lung regions of a mechanically ventilated animal model of ARDS. Moreover, FIO2 did not affect atelectasis-induced inflammation or tissue injury. These findings suggest that raising FIO2 levels to attenuate hypoxia-induced lung inflammation and injury cannot be rationalized. However, organs other than the lungs are more vulnerable to hypoxemia, and caution should be exercised to maintain oxygen tension above the limit inducing organ damage.

This study is the first to directly demonstrate the effects of FIO2 on oxygen tension in atelectatic lung tissues. Our results indicated that these effects were negligible. A previous study demonstrated that high FIO2 levels rescued right-sided heart failure in animals with atelectasis8, which reflects pulmonary hypertension due to lung tissue hypoxia. However, the study did not evaluate oxygen tension in the atelectatic lung tissue, and it is possible that elevated oxygen partial pressure in the ventilated lung region, rather than in the atelectatic lung region, may lower pulmonary vascular resistance. Based on the concentrations of HIF-1α and pimonidazole staining of lung tissues, the oxygen diffusion to atelectatic lung regions seems very limited and cannot rescue atelectatic lung tissue hypoxia. On the other hand, HIF-1α stabilization in lung tissue was suppressed by the open lung approach with PEEP and recruitment maneuver. Our results suggest that the open-lung approach is the only efficient method for rescuing lung tissue from hypoxia.

Alveolar tissue hypoxia causes inflammation. We previously demonstrated that alveolar hypoxia during atelectasis increases CXCL-1 expression in alveolar epithelial cells through NF-kB activation4. Other previous studies have also demonstrated alveolar macrophage16–18 and neutrophil7,19,20 activation under hypoxic conditions. Moreover, our previous study showed that improving lung aeration through an open-lung approach can reduce lung inflammation and injury5, possibly by attenuating lung tissue hypoxia. However, the present study demonstrated that changes in FIO2 levels did not significantly affect alveolar tissue damage or inflammatory responses in animals with experimental ARDS and atelectasis. As mentioned above, this may be attributed to the inability of the inspiratory gas to diffuse into the atelectatic lung tissue, not significantly affecting inflammation or tissue injury. In other words, lowering FIO2 levels in patients with ARDS with atelectasis does not seem to aggravate lung tissue inflammation or injury.

Hyperoxia also causes lung injury through the generation of reactive oxygen species9,10,21. Based on these observations, several randomized controlled trials have evaluated the efficacy of conservative oxygen therapy in critically ill patients11–14. However, all the studies have not demonstrated the benefits of conservative oxygen therapy. Consistent with these clinical studies, our study did not demonstrate the harmful effects of high FIO2 concentrations, although the duration of exposure was relatively short. In the discussion regarding oxygen toxicity, attention should be paid to the fact that several experimental animal studies have evaluated oxygen toxicity in small rodents, which are more vulnerable to hyperoxia than large mammals10. Further clinical investigations are necessary to evaluate whether conservative oxygen therapy truly has beneficial effects.

We observed that hypoxemia in the low FIO2 group led to hypotension, lactic acidosis, and liver and kidney injury. A recent clinical study evaluating the effects of FIO2 on ARDS demonstrated that conservative oxygen therapy was associated with mesenteric ischemia in patients with ARDS12 Moreover, targeting lower arterial partial oxygen pressure may impair cognitive function and adversely affect long-term outcomes in survivors of ARDS22,23. Oxygen toxicity has mainly been demonstrated in the lungs. In contrast, the toxicity of oxygen to other organs is not clear, except in special settings such as ischemia-reperfusion injury. Oxygen tension was highest in the lungs and decreased thereafter to the end organs. Caution should be exercised to prevent hypoxemia in organs other than the lungs.

This study had some limitations. First, the duration of mechanical ventilation was shorter than that used in the clinical setting. Therefore, the observed effects of increasing FIO2 might be minimal. However, analysis of mRNA, which changes promptly after the stimulus, also showed no significant changes, suggesting that the effects of FIO2 against atelectasis-induced lung injury are minimal. Second, we used LPS, not bacteria, to induce experimental ARDS. Therefore, the effects of FIO2 on pathogen load and immunological responses are unclear. Several studies have demonstrated that atelectasis causes immunosuppression in the lungs. Therefore, FIO2 may affect immunological responses in infection-induced ARDS accompanied by atelectasis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, increasing FIO2 levels did not attenuate tissue hypoxia, inflammation, or injury in the atelectatic lung regions during short-term mechanical ventilation for LPS-induced ARDS. On the other hand, hypoxemia with a too low FIO2 level had detrimental effects on the liver and kidneys. Our results indicate that increasing the FIO2 concentration to attenuate atelectasis-induced lung injury cannot be rationalized. However, attention should be paid to preventing severe hypoxemia because it is harmful to organs other than the lungs.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Akiko Adachi and Ms. Yuki Yuba for their technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BALF

Broncho-alveolar lavage fluid

- CT

Computed tomography

- FIO2

Fraction of inspired oxygen

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- PaCO2

Partial pressure of arterial carbondioxide

- PaO2

Partial pressure of arterial oxygen

- PEEP

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- P/F ratio

PaO2/ FIO2 ratio

- TV

Tidal volume

- ZEEP

Zero end-expiratory pressure

Author contributions

K. Tojo conceived and designed the study, performed experiments, and wrote the manuscript. T. Yazawa performed histological examinations and revised the manuscript.

Funding

Supported, in part, by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (17K17062, 22K09146).

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All experimental animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Research Committee of Yokohama City University, Japan.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Puybasset, L. et al. Regional distribution of gas and tissue in acute respiratory distress syndrome. I. consequences for lung morphology. Intensiv. Care Med26, 857–869 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert, R. K. The role of ventilation-induced surfactant dysfunction and atelectasis in causing acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med.185, 702–708 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Retamal, J. et al. Non-lobar atelectasis generates inflammation and structural alveolar injury in the surrounding healthy tissue during mechanical ventilation. Crit. Care18, 505 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tojo, K. et al. Atelectasis causes alveolar hypoxia-induced inflammation during uneven mechanical ventilation in rats. Intensiv. Care Med. Exp.3, 18 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tojo, K., Yoshida, T., Yazawa, T. & Goto, T. Driving-pressure-independent protective effects of open lung approach against experimental acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care22, 228 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinelli, E. et al. Pathophysiological profile of non-ventilated lung injury in healthy female pigs undergoing mechanical ventilation. Commun. Med.4, 18 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoenderdos, K. et al. Hypoxia upregulates neutrophil degranulation and potential for tissue injury. Thorax71, 1030 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duggan, M. et al. Oxygen attenuates atelectasis-induced injury in the in vivo rat lung. Anesthesiology103, 522–531 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochberg, C. H., Semler, M. W. & Brower, R. G. Oxygen toxicity in critically ill adults. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med.204, 632–641 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lilien, T. A., van Meenen, D. M. P., Schultz, M. J., Bos, L. D. J. & Bem, R. A. Hyperoxia-induced lung injury in acute respiratory distress syndrome: What is its relative impact? Am. J. Physiol-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol.325, L9–L16 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Group I-RI and the A and NZICSCT, Mackle D, Bellomo R, BaileyM, Beasley R, Deane A et al. Conservative oxygen therapy during mechanical ventilation in the ICU. N. Engl. J. Med.382, 989–998 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Barrot, L. et al. Liberal or conservative oxygen therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl. J. Med.382, 999–1008 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schjørring, O. L. et al. Lower or higher oxygenation targets for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl. J. Med.384, 1301–1311 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Wal, L. I. et al. Conservative versus liberal oxygenation targets in intensive care unit patients (ICONIC): A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med.208, 770–779 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leeper-Woodford, S. K. & Detmer, K. Acute hypoxia increases alveolar macrophage tumor necrosis factor activity and alters NF-κB expression. Am. J. Physiol-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol.276, L909–L916 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chao, J., Wood, J. G., Blanco, V. G. & Gonzalez, N. C. The systemic inflammation of alveolar hypoxia is initiated by alveolar macrophage–borne mediator(s). Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol.41, 573–582 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chao, J., Donham, P., van Rooijen, N., Wood, J. G. & Gonzalez, N. C. Monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 released from alveolar macrophages mediates the systemic inflammation of acute alveolar hypoxia. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol.45, 53–61 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watts, E. R. et al. Hypoxia drives murine neutrophil protein scavenging to maintain central carbon metabolism. J. Clin. Investig. 131. 10.1172/jci134073 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Lodge, K. M. et al. Hypoxia increases the potential for neutrophil-mediated endothelial damage in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med.205, 903–916 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minkove, S. et al. Effect of low-to-moderate hyperoxia on lung injury in preclinical animal models: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensiv Care Med. Exp.11, 22 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hopkins, R. O., Weaver, L. K., Pope, D., Orme Jr, J. F., Bigler, E. D. & Larson-Lohr, V. Neuropsychological sequelae and impaired health status in survivors of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med.160, 50–56 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikkelsen, M. E. et al. The adult respiratory distress syndrome cognitive outcomes study. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med.185, 1307–1315 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.