Abstract

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is one of the highly fatal cancers and poses a serious threat to human health. Ferroptosis has been widely studied and proved to have an important role in tumor suppression, providing new avenues for cancer therapy; glutathione peroxidase 4(GPX4) and selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase(TXNRD1) are important regulatory targets in ferroptosis.Warburg effect is one of the important energy sources for cancer hypermetabolism, and pyruvate kinase isoenzyme 2 (PKM2) is a key metabolism enzyme that is important in this effect. Shikonin(SKN) is a Chinese herb that has been extensively studied for its anti-tumor ability. The aim of this study was to investigate the mechanism of anti-tumor effect of SKN in ATC cells and to elucidate the role played by ferroptosis and glycolysis in this inhibitory mechanism. The effects of SKN in ATC cell lines CAL-62 and 8505C cells were detected by flow cytometry, Western blotting,real-time quantitative PCR and a fluorescent probe for reactive oxygen species (ROS) to detect changes in intracellular ROS positivity; glucose and lactate assay kits to detect the levels of the raw material of glucose metabolism, glucose (GLU), and the product of glucose metabolism, lactate (LD); and the establishment of the BALB/C nude mice subcutaneous tumor model to analyse the inhibitory effect of SKN on ATC in vivo. The present study demonstrated that SKN inhibits the expression of NF-κB,GPX4,TXNRD1,PKM2,GLUT1.SKN inhibits ATC cell growth by down-regulating the occurrence of intracellular ferroptosis and inhibiting glycolysis in ATC cells.

Keywords: Shikonin, NF-κB, Anaplastic-thyroid-carcinoma, Ferroptosis, PKM2

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma [1] (ATC) is one of rare and highly aggressive malignant tumor, accounting for 2%–3% of all thyroid tumors. Clinically, a certain percentage of patients with ATC are diagnosed at an advanced stage, and treated with systemic treatments, such as chemotherapy and multi-kinase [2] inhibitors. Cytotoxic chemotherapeutic regimens (e.g., paclitaxel/carboplatin or paclitaxel, carboplatin monotherapy), alone or in combination with radiotherapy, are the mainstay of treatment [1]. However, the overall survival remains poor, and has not improved significantly for decades. The search for novel molecular therapeutic chemotherapeutic agents is an urgent requirement and challenge.

Sustaining high lactate production in tumors under aerobic conditions is known as aerobic glycolysis [3]. Human cancer cells have been shown to express only the embryonic M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase (pyruvate kinase M2, PKM2) [4], and PKM2 expression has been shown to be required for aerobic glycolysis. The most important and widely expressed glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) [5] in cells has been shown in recent years to be involved in cancer [6]. And protein levels of GLUT1 are frequently higher in tumors than in normal tissues.

Ferroptosis [7] is a form of programmed cell death, and unlike other forms of regulated cell death (e.g., apoptosis, autophagy). Ferroptosis [7] is dependent on the metabolite reactive oxygen species (ROS), and intracellular signals, environmental stresses [8]. GPX4 [9], as the only enzyme with the function of reducing phospholipid hydroperoxides (PLOOH), is considered to be one of the most important antioxidant enzymes in mammals, and its deficiency promotes ferroptosis. Inhibition of thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) [10], a selenoprotein in the thioredoxin system, results in the inability to complete the reduction of cystine to cysteine, preventing this antioxidant process and promoting the onset of intracellular ferroptosis [11].

Chinese herb Shikonin(SKN) [12], as a natural naphthoquinone small molecule compound, is known to have an anti-tumor effects [13] in recent years, SKN has shown great potential in tumor therapy due to its inhibitory effects on PKM2 [4] and TXNRD1 [13], and recent studies have revealed that SKN is a small-molecule inhibitor [14] targeting NEMO/IKKβ, affecting the formation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which is necessary for the activation of the classical NF-κB pathway.

The aim of this study was to explore the mechanism of action of SKN in inhibiting the growth of ATC cells.

1. Materials and methods

1.1. Materials

The CAL-62 and 8505C human ATC cell line used in this experiment was obtained from the cell bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences(Shanghai, China). Female Balb/c mice (4–5W) were purchased from Beijing Vitalstar Laboratory Animal Centre (Beijing, China). SKN (B21682, HPLC ≥98 %) was purchased from Yuan Ye (Shanghai, China). The main consumables used in this experiment were as follows: cell culture medium, foetal bovine serum, trypsin Vivacell (Shanghai, China), DMSO (Solarbio, China), cDNA Synthesis kit and SYBR qPCR SuperMix Plus kit (Novoprotein, China), lactate and glucose detection kit (Nanjing Jianjian, China).

2. Methods

-

1.

Cell culture: CAL-62 and 8505C ATC cells were grown in DMEM and 1640 medium containing 10 % FBS, respectively, at 37 °C and 5 % CO2 in an incubator. the cells were treated with SKN (1, 3, and 5 μM) for 24 h. Each experiment was repeated in three independent parallel tests.

-

2.

Lactic acid production and glucose uptake: When CAL-62 and 8505C cells seed in six-well plates reached 70–80 % fusion, the culture medium was changed according to the instructions of the glucose assay kit manufacturer and SKN (1, 3, 5 μM) was added for 4h, and then the change of glucose residue in the supernatant of the culture solution was measured after 4 h of treatment with different concentrations of SKN. According to the instructions of the lactate detection kit manufacturer, the amount of intracellular lactate production was monitored after ultrasonic fragmentation by adding SKN (1, 3, 5 μM) for 24 h of treatment.

-

3

ROS fluorescence probe experiment: When 70–80 % of CAL-62 cells inoculated in the 12-well plate were fused, the cells were treated with SKN (1, 3, 5 μM) for 24 h, and then fluorescent probe was added. After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and then placed under inverted fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany) took images of the reduced and oxidized states of cells under different excitation light.

-

4.

qPCR: RNA was extracted using the Trizol method and first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the cDNA Synthesis kit. mRNA levels of PKM2, GLUT1, and GPX4 were assessed using the SYBR qPCR SuperMix Plus kit. for quantitative PCR assessment.

PKM2(5′ATTATTTGAGGAACTCCGCCGCCT3′,5′ATTCCGGGTCACAGCAATGATGG3′),GLUT1(5′GGCCAAGAGTGTGCTAAAGAA3′,5′ACAGCGTTGATGCCAGACAG3′),GPX4(5′GAGGCAAGACCGAAGTAAACTAC3′,5′CCGAACTGGTTACACGGGAA3′) and using the 2 −ΔΔCT method. The amplification reaction included pre-denaturation: 95 °C for 30 s. PCR reaction: 95 °C for 20 s, 60 °C for 1 min, a total of 35∼40 cycles.

-

5

Western blotting(WB) experiment: Total protein was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor (PMSF). After lysis on ice for 20 min the cell extracts were centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 10 min at around 4 °C and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentration was measured using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein quantification kit. Twenty μg of cellular protein (or 80 μg for tissue sample) was separated on an SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane. After closure with protein-free rapid closure solution, PVDF was conjugated with primary antibodies for protein detection, anti-TXNRD1 (ab124954), anti-GLUT1 (ab115730), purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, USA); anti-GAPDH (ET1601-4), anti-PKM2 (R1603-5), anti-GPX4 (ET1706-45), and anti–NF–κB (ET1603-12) were purchased from (Hua'an, China). After binding, it was placed in TBST and washed on a shaker 5 times for 6 min each. followed and PRSPURE HRP-labelled goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (AN19618, ANOLA), PRSPURE HRP-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (AN196117, ANOLA). They were operated on a fully automated multifunctional chemiluminescence imager (Tannen, Shanghai) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

-

6

Flow cytometry assay: Cells were inoculated in 12-well plates at a density of 3.5 × 103 cells per well and treated with SKN for 24 h. Cells were harvested by trypsin digestion for 15 s according to the manufacturer's instructions (Yeason, China) and stained with membrane-bound protein V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI). The cells were detected by flow cytometry (ACEA, USA).

-

7

Animal experiment: Female Balb/c mice were kept at constant temperature (16–25 °C). constant humidity (65–70 %) and light-dark cycle for 12 h environment. 5 × 106 CAL-62 cells were inoculated into the dorsal subcutis of 4–5 W female Balb/c mice, when the tumor volume reached 90–100 mm3, the mice were randomly divided into two groups of four each, SKN (2 % DMSO, 5 mg/kg/d), control group (gavage of the same solvent), and the mice were gavaged once a day for 14 consecutive days, and the tumor volume was recorded by using vernier calipers every two days. Tumor volume and and body weight changes of mice were monitored every two days. tumor volume (V) was assessed as V = (length × width2)/2. Tumor tissues were taken on the 14th day of administration, and 30–45 mg of tumor tissues were extracted as protein for subsequent experiments. The experimental protocol strictly followed the ethical norms of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the General Hospital of Tianjin Medical University and the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals(IRB2023-DWFL-130).

-

8

Statistics: Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. All data were obtained from three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad software 9.0 (USA). Multiple group comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and t-tests were used to analyse differences between the 2 groups. To quantify protein blotting and ROS fluorescent probes were evaluated using ImageJ software 1.52a (USA). A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. The expression of NF-κB reduced by SKN

The results of flow cytometry demonstrated different degrees of cell death after treatments with 1, 3 and 5 μM SKN for 24 h (all P < 0.05; Fig. 1A–D). The results of WB assay showed that the protein expression of NF-κB was decreased after treatment with 5 μM SKN in both CAL-62 and 8505C cancer cells (all P < 0.05; Fig. 1E and F).

Fig. 1.

Effects of SKN treatment on cell death and intracellular NF-κB expression in ATC cells for 24 h. (a–d) CAL-62 and 8505c cells were treated with 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 µM SKN for 24 h, and cell apoptosis was analyzed using flow cytometry. (e-f) CAL-62 and 8505c cells were incubated with 1,3 or 5 µM shikonin for 24 h. Intracellular expression levels of NF-κB were analyzed using western blotting.*P < 0.05. SKN, Shikonin; FITC, Fluorescein Isothiocyanate; PE, phycoerythrin.

3.2. Glycolysis and glucose uptake were inhibited by SKN

In CAL-62 and 8505C cancer cells treated with 1, 3, and 5 μM concentrations of SKN, qPCR experiments showed that the expression of PKM2 and GLUT1 decreased at the mRNA level (all P < 0.01; Fig. 2A). Expression of GLUT1 in CAL-62 cells decreased after SKN treatment at 3 and 5 μM concentrations (P < 0.05), with the lowest expression at 5 μM concentration. In 8505C cells, GLUT1 significant decreased after SKN treatment at all concentrations (P < 0.05). The expression of PKM2 of both cells line at the mRNA level decreased in a concentration-dependent manner. The results of WB experiments showed that the expression of PKM2 and GLUT1 in both cells at the protein level decreased after SKN treatment at 3 and 5 μM concentrations, and the lowest expression is observed at 5 μM. GLUT1 protein level expression in CAL-62 cells decreased steadily after SKN treatment at 5 μM concentration (all P < 0.05; Fig. 2B and C).

Fig. 2.

Effects of SKN treatment on glycolysis and glucose uptake in ATC cells for 24 h. (a) CAL-62 and 8505c cells were treated with 1, 3 or 5 µM SKN for 24 h, mRNA expression levels of GLUT1,PKM2 were analyzed using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (b–c) Intracellular expression levels of GLUTI,PKM2 were analyzed using western blotting. (d) Intracellular lactate production. (e) Residual glucose in the supernatant of cell culture medium glucose uptake. *P < 0.05. SKN, Shikonin; GLUT1, glucose transporter1; PKM2, pyruvate kinase M2.

Measurements of glucose uptake after 1, 3, and 5 μM concentrations of SKN treatment for 24 h showed a decrease in both cells. Lactate production in the cells decreased with the rise of SKN treatment concentration (all P < 0.05; Fig. 2D). After 4 h of SKN treatment of CAL-62 and 8505C cancer cells at 1, 3, and 5 μM concentrations, the uptake of glucose by the cells declined and residue glucose in the supernatant increased as the concentration of SKN action rose (all P < 0.05; Fig. 2D).

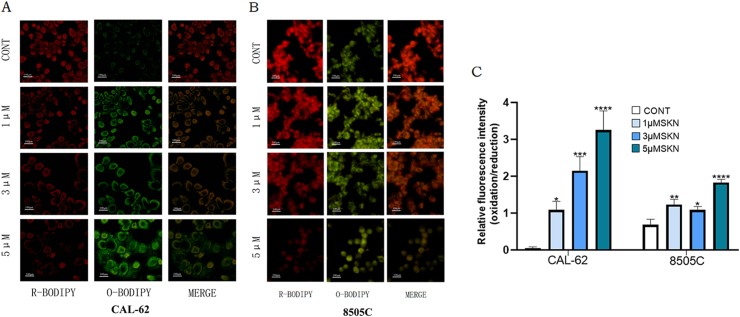

3.3. ROS was promoted by SKN

CAL-62 and 8505C cancer cells were treated with SKN at concentrations of 1, 3, and 5 μM for 24 h and then incubated at 37 °C for 30 min with ROS fluorescent probes. The results under the fluorescence microscope showed that as the concentration of SKN acting on the ATC cells increased, the redox in the cells changed and the rate of ROS positivity increased (all P < 0.05; Fig. 3A and B). In CAL62 cells, cellular ROS increased significantly with the rise in SKN concentration. 8505C cells showed an increase in ROS after 24h of SKN treatment (all P < 0.05; Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Effects of SKN treatment on REDOX environment of ATC cells after 24 h. (a–b) CAL-62 and 8505c cells were treated with 1, 3 or 5 µM SKN for 24 h, after the cell was combined with the probe, the fluorescence signal of the reduction state was weakened and the fluorescence signal of the oxidation state was enhanced. (d) The ratio of fluorescence intensity between oxidation and reduction increased. *P < 0.05. SKN, Shikonin.

3.4. Ferroptosis was promoted by SKN

After pre-treatment with Liproxstatin-1 (L-1), for 2 h prior to the administration of SKN at a concentration of 5 μM to the CAL-62 and 8505C cancer cell lines, the results of flow cytometry experiments showed a reduction in the PI positivity rate in the group co-treated with L-1 and SKN compared to the group treated with SKN alone, suggesting that a portion of the cells treated with SKN had a cell death mode is ferroptosis (all P < 0.05; Fig. 4A and B).

Fig. 4.

Effects of SKN treatment on ferroptosis in ATC cells for 24 h. (a–b) Intracellular death decreased in the group treated with L-1 and SKN for 24 h compared with the group treated with SKN alone for 24 h. (c) CAL-62 and 8505c cells were treated with 1, 3 or 5 µM SKN for 24 h, mRNA expression levels of GPX4 was analyzed using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (d–e) Intracellular expression levels of TXNRD1, GPX4 were analyzed using western blotting. *P < 0.05. SKN, Shikonin; L-1, Liproxstatin-1; TXNRD1, selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase 1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4.

In CAL-62 and 8505C cancer cell lines, qPCR experiments showed that the expression of GPX4 was significantly decreased at the mRNA level in CAL-62 and 8505C cancer cell lines after 24 h of treatment with SKN (all P < 0.05; Fig. 4C). The results of WB experiments after treatment with 1, 3, and 5 μM concentrations of SKN for 24 h (all P < 0.05; Fig. 4D and E) showed that the expression of TXNRD1 and GPX4 at the protein level decreased in CAL-62 cells after 5 μM SKN treatment; the expression of TXNRD1 protein level in 8505C cells decreased with the increase of SKN action concentration (all P < 0.05; Fig. 5B and C).

Fig. 5.

ATC cell growth was inhibited SKN in vivo. (a): The tumor volume in vitro was smaller between SKN administration group and solvent control group. (b): The body weight of mice in control group and SKN administration group did not decrease; (c): The growth rate of tumor volume in SKN administration group was smaller than that in control group; (d–e): The changes in the expression levels of ferroptosis and glycometabolism-related proteins in tumor tissues compared with the control group were consistent with in vitro experiments; *P < 0.05. SKN, Shikonin; GLUT1, glucose transporter 1; PKM2, pyruvate kinase M2; TXNRD1, selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase 1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4.

3.5. ATC cell growth was inhibited SKN in vivo

Volume change of tumor during the 14 days observation displayed the tumor growth rate in the SKN group was lower than that in the control solvent group (all P < 0.05; Fig. 5A and B), tumor tissue WB experiments showed that the protein expression levels of GPX4, TXNRD1, NF-κB, PKM2, and GLUT1 in the tumor are all decreased compared to the solvent control group (all P < 0.05; Fig. 5C and D). Consistent with the results of in vitro experiments.

4. Discussion

NF-κB [15] is a transcription factor essential in tumor progression that regulates inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis [16], and inhibition of NF-κB interferes with tumor metabolism and antioxidant effects [17]. In resting cells, typical NF-κB is in an inactive state bound to its inhibitor IκBα [14], which can be phosphorylated by the IKK complex to activate the classical NF-κB pathway. In the classical NF-κB pathway, IKKβ has an important role in the degradation of IκBα, and the binding of NEMO to the C-terminal region of IKKβ usually leads to conformational changes of IKKβ, and last year, it has been demonstrated that SKN [14] can affect its binding at the nanomolar level, which in turn inhibits its phosphorylation and kinase activity. Affecting the activation of the classical NF-κB pathway and inhibiting NF-κB expression. PKM2, as a key enzyme in the regulation of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, many previous cancer-related studies, demonstrated that PKM2 acts upstream of NF-κB, and on the other hand, NF-κB can also indirectly effect on the expression of PKM2 [18]. Reducing NF-κB expression can interfere with tumor metabolism and antioxidant effects potentially also inhibit glycolysis. The results of this study showed that the protein expression of NF-κB and PKM2 decreased in ATC cells after SKN treatment.

SKN [12], the main constituent of dried Shikonin roots. At present, SKN has been widely used in TCM preparations to treat various diseases, such as topical drugs to treat skin diseases. SKN, as its main active ingredient, plays a key role in anti-inflammatory and wound healing [19]. Because of this, SKN is of great significance in anti-tumor therapy. So far, in terms of accurate, adequate and effective delivery of SKN drug molecules, there have been options such as liposomes and nanoparticles, which can achieve the above requirements by improving the physical and chemical properties [20]. The effectiveness of shikonin in anti-tumor has been widely recognized [21], it has been shown to have good anti-tumor capacity, which can inhibit cancer cell metastasis [22] and invasion [23]. In terms of thyroid cancer treatment, we only retrieved two studies related to SKN and thyroid cancer. SKN inhibits DNA methyltransferase 1 and thus the migration of the TPC-1 cell line of papillary thyroid carcinoma [23]. And SKN selectively inhibits cell migration and invasion in medullary thyroid carcinoma [24]. Relevant studies are very limited, which was one of the original reasons for us to carry out the treatment of ATC with SKN. SKN has been found to increase sensitivity to ferroptosis, and recently it was found that SKN can induce ferroptosis in multiple myeloma through ferritin autophagy [25]. Our experiments detail the specific mechanism of action of SKN in inducing intracellular ferroptosis in ATC cells when treating ATC cells, bringing new references to the clinical treatment of ATC.

GPX4 [8] is a central regulator of ferroptosis induced by the ferroptosis inducers erastin and RSL3, which prevents ferroptosis by converting lipid hydroperoxides to non-toxic lipohydrols. And GPX4 has a catalytic reduction of PLOOH to prevent it from synthesising polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are the initiating substances of ferroptosis, and it plays an important role in initiation of the ferroptosis process, and serves as a classical target of ferroptosis inhibition. As a classical target of ferroptosis inhibition, GPX4 deficiency promotes the occurrence of ferroptosis. TXNRD1 [26], as a key enzyme in the thioredoxin system, scavenges ROS driven by the transcriptional activation of nuclear factor-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) [27], which is involved in the process of cystine reduction to cysteine. And TXNRD1's inhibition prevents this antioxidant process, which plays an important role in the maintenance of the cellular redox environment. TXNRD1 was recently found to be another inhibitory target of ferroptosis [11]. In this study, we found that the expression of GPX4 and TXNRD1 was significantly decreased after SKN treatment of ATC cells.

In conclusion, this experiment demonstrated that SKN treatment of ATC cells could reduce intracellular NF-κB expression, decrease glycolysis and lactate production by inhibiting the expression level of PKM2. By inhibiting the expression of GLUT1, the uptake of glucose by ATC cells was reduced. SKN, as an inhibitor of TXNRD1, could simultaneously reduce the expression of GPX4, change the intracellular redox environment, promoting ROS generation and ferroptosis in ATC cells.

This study and its experimental procedures were approved by the Experimental Animal Welfare Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital (Approval number:IRB2023-DWFL-130). All animals are raised and tested in strict accordance with the institution's standards of care and use.

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article (and its supplementary materials), as well as requesting corresponding authors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chen Yang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Lei Yang: Supervision, Investigation. Dihua Li: Supervision, Methodology. Jian Tan: Supervision. Qiang Jia: Supervision. Huabing Sun: Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. Zhaowei Meng: Validation, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Yan Wang: Supervision, Methodology.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Tianjin Science and Technology Committee Foundation grant (#21JCYBJC01820), the National Natural Science Foundation of China grants (#81571709 and #81971650). This work was also supported by Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (TJYXZDXK-001A).

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34291.

Contributor Information

Chen Yang, Email: yc666666333@163.com.

Lei Yang, Email: nkyanglei@126.com.

Dihua Li, Email: dhli2013@163.com.

Jian Tan, Email: 892415346@qq.om.

Qiang Jia, Email: jiaqiangde4321@163.com.

Huabing Sun, Email: sunhuabing@tmu.edu.cn.

Zhaowei Meng, Email: jamesmencius@163.com, zmeng@tmu.edu.cn.

Yan Wang, Email: wangyan@tjutcm.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

figs2.

figs3.

figs4.

figs5.

figs6.

figs7.

figs8.

figs9.

figs10.

figs11.

figs12.

figs13.

figs14.

figs15.

figs16.

figs17.

figs18.

figs19.

figs20.

figs21.

figs22.

References

- 1.Amaral M., Afonso R.A., Gaspar M.M., et al. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: HOW far can we go? Excli Journal. 2020;19:800–812. doi: 10.17179/excli2020-1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo J.T., Wang Y., Zhao L.K., et al. Anti-anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) effects and mechanisms of PLX3397 (pexidartinib), a multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) Cancers. 2023;15(1):15. doi: 10.3390/cancers15010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heiden M.G.V., Cantley L.C., Thompson C.B. Understanding the warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324(5930):1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai Y.T., Liu Y.P., Li J.Y., et al. Shikonin inhibited glycolysis and sensitized cisplatin treatment in non-small cell lung cancer cells via the exosomal pyruvate kinase M2 pathway. Bioengineered. 2022;13(5):13906–13918. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2022.2086378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Q., Ba-Alawi W., Deblois G., et al. GLUT1 inhibition blocks growth of RB1-positive triple negative breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berlth F., Monig S., Pinther B., et al. Both GLUT-1 and GLUT-14 are independent prognostic factors in gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg Oncol. 2015;22:S822–S831. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stockwell B.R., Jiang X.J., Gu W. Emerging mechanisms and disease relevance of ferroptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2020;30(6):478–490. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shintoku R., Takigawa Y., Yamada K., et al. Lipoxygenase-mediated generation of lipid peroxides enhances ferroptosis induced by erastin and RSL3. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(11):2187–2194. doi: 10.1111/cas.13380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang W.S., Sriramaratnam R., Welsch M.E., et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156(1–2):317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felix L., Mylonakis E., Fuchs B.B. Thioredoxin reductase is a valid target for antimicrobial therapeutic development against gram-positive bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.663481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheff D.M., Huang C.Y., Scholzen K.C., et al. The ferroptosis inducing compounds RSL3 and ML162 are not direct inhibitors of GPX4 but of TXNRD1. Redox Biol. 2023;62:10. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan C.M., Li Q.X., Sun Q., et al. Promising nanomedicines of shikonin for cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023;18:1195–1218. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S401570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan D.Z., Zhang B.X., Yao J., et al. Shikonin targets cytosolic thioredoxin reductase to induce ROS-mediated apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;70:182–193. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Z.L., Gao J., Zhang X.L., et al. Characterization of a small-molecule inhibitor targeting NEMO/IKK beta to suppress colorectal cancer growth. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2022;7(1):13. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00888-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayden M.S., Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappa B signaling. Cell. 2008;132(3):344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fei M., Li Z., Cao Y.W., et al. MicroRNA-182 improves spinal cord injury in mice by modulating apoptosis and the inflammatory response via IKK beta/NF-kappa B. Lab. Invest. 2021;101(9):1238–1253. doi: 10.1038/s41374-021-00606-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan M.J., Liu Z.G. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-kappa B signaling. Cell Res. 2011;21(1):103–115. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang W.W., Xia Y., Cao Y., et al. EGFR-induced and PKC epsilon monoubiquitylation-dependent NF-kappa B activation upregulates PKM2 expression and promotes tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell. 2012;48(5):771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo C.J., He J.L., Song X.M.T., et al. Pharmacological properties and derivatives of shikonin-A review in recent years. Pharmacol. Res. 2019:149. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Q., Gong T., Liu M.L., et al. Shikonin, a naphthalene ingredient: therapeutic actions, pharmacokinetics, toxicology, clinical trials and pharmaceutical researches. Phytomedicine. 2022;94 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boulos J.C., Rahama M., Hegazy M.E.F., et al. Shikonin derivatives for cancer prevention and therapy. Cancer Lett. 2019;459:248–267. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L.L., Zhan L., Jin Y.D., et al. SIRT2 mediated antitumor effects of shikonin on metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017;797:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y., Sun B., Huang Z., et al. Shikonin inhibites migration and invasion of thyroid cancer cells by downregulating DNMT1. Med. Sci. Mon. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2018;24:661–670. doi: 10.12659/MSM.908381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasenoehrl C., Schwach G., Ghaffari-Tabrizi-Wizsy N., et al. Anti-tumor effects of shikonin derivatives on human medullary thyroid carcinoma cells. Endocrine Connections. 2017;6(2):53–62. doi: 10.1530/EC-16-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W.X., Fu H.J., Fang L.Y., et al. Shikonin induces ferroptosis in multiple myeloma via GOT1-mediated ferritinophagy. Front. Oncol. 2022;12:15. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1025067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee D., Xu I.M.J., Chiu D.K.C., et al. Induction of oxidative stress through inhibition of thioredoxin reductase 1 is an effective therapeutic approach for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2019;69(4):1768–1786. doi: 10.1002/hep.30467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao Q.Z., Zhang G.J., Zheng Y.Q., et al. SLC27A5 deficiency activates NRF2/TXNRD1 pathway by increased lipid peroxidation in HCC. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27(3):1086–1104. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0399-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.