Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to compare the marginal adaptation of a cold ceramic (CC) sealer with the single-cone obturation technique with that of an AH-26 sealer with the lateral compaction technique in single-canal teeth.

Materials and methods

In this in vitro experimental study, the root canals of 24 extracted single-rooted single-canal teeth were instrumented to F3 files by the crown-down technique and randomly assigned to 2 groups (n = 12). The root canals were obturated with a CC sealer and single-cone obturation technique with 4% gutta-percha in group 1 and with an AH-26 sealer and lateral compaction technique with 2% gutta-percha in group 2. After 4 weeks of storage at room temperature and 100% humidity, the root ends were sectioned horizontally 3 mm from the apex, and the mean linear distance between the root filling material and the root dentinal wall was measured under a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Comparisons were made by the Mann‒Whitney test (alpha = 0.05).

Results

The mean linear distance (gap) was significantly smaller in the CC sealer/single-cone group than the AH-26/lateral compaction group (6.72 ± 2.57 vs. 12.94 ± 4.82 μm, P = 0.001).

Conclusion

Marginal adaptation was significantly higher with the CC sealer and single-cone obturation technique than with the AH-26/lateral compaction technique, suggesting the suitability of the CC sealer and single-cone obturation technique for a hermetic seal in single-canal teeth.

Keywords: Epoxy Resin AH-26, Dental marginal adaptation, Root Canal Obturation, Electron scanning Microscopy

Introduction

Despite the high success rate of root canal therapy (78–91%), treatment failure still occurs [1]. Evidence shows that over 88% of endodontic failures occur due to apical microleakage [2]. Residual bacteria in the root canal system are mainly responsible for treatment failure [3].

The main goal of endodontic treatment is to create a three-dimensional hermetic seal to prevent the invasion of microorganisms and their recolonization in the root canal system [4]. Gutta-percha and sealer are currently the most commonly used combination for root canal obturation [5]. Sealers fill the irregularities in the root canal walls to enhance an optimal seal [6]. Nonetheless, none of the currently available sealers can provide an ideal seal [7].

The success of endodontic treatment can be maximized to 96% by creating a hermetic seal [8]. An ideal sealer should be biocompatible, nontoxic, and radiopaque. It should have antimicrobial activity, completely fill the root canal, and have dimensional stability and proper adhesion to the root canal walls [9]. Several sealers with different formulations have been proposed over the years to improve apical seal, including zinc oxide eugenol (ZOE)-based sealers, calcium hydroxide-based sealers, silicone sealers, urethane methacrylate sealers, resin-based sealers, and bioceramic sealers.

AH-26 is currently the most commonly used epoxy resin-based sealer and has optimal properties, such as easy mixing and application, suitable flow, antimicrobial activity, acceptable adaptation to root dentinal walls, and proper working time [10]. It has been reported that AH-26 has excellent sealing ability [11]. However, discoloration, relative insolubility in solvents, relative cytotoxicity of its fresh unset form, and relative solubility in oral fluids are among its drawbacks [12].

Bioceramic sealers are ceramic compounds with excellent biocompatibility due to their resemblance to biological hydroxyapatite (HA). In the process of hydration, they produce different products, such as HA, which can induce a regenerative response. Mineral HA has osteoconductive properties in contact with bone, resulting in bone formation at the contact interface. This inherent ability appears to be due to the ability of bioceramics to attract osteoinductive components to the healing site [13]. Dentin remineralization, acceptably low cytotoxicity, optimal antibacterial activity (due to a high pH of up to 12), favorable penetration into dentinal tubules, no polymerization shrinkage, high sealability, and minimal microleakage by chemical bonding to dentinal walls are among the other advantages of bioceramic sealers [14, 15]. Mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA), BioAggregate, Biodentine, iRoot FS and Cold Ceramic (CC) are among the calcium silicate-based bioceramic materials [16].

CC has an almost similar composition to MTA, which was introduced in 2000 as the first white bioceramic material [17]. It is supplied in the form of powder and liquid and is used as a root-end filling material, for perforation repair, as an apical barrier in open-apex teeth, as a potential root canal filling paste, and as a pulp capping agent and in pulpotomy [18–21]. It has a tricalcium silicate base, and its powder contains fine hydrophilic particles that are set in the presence of moisture. It is prepared by mixing its white powder with water at a proper ratio [22]. Its main constituents include silicon oxide, calcium oxide, sulfur trioxide, and barium oxide, accounting for 93% of its ingredients. Other ingredients include K2O, Na2O, Fe2O3, MnO, MgO, and TiO2 [23]. Its initial and final setting times are 15 min and 24 h, respectively [17, 24].

The CC sealer is a new bioceramic sealer created by the addition of a proper solvent to CC material. It is based on CC and is supplied in the form of powder and liquid. It sets in the presence of moisture of the dentinal tubules and the environment.

The single-cone obturation technique is commonly adopted when calcium silicate sealers are used. In this technique, gutta-percha only serves as a carrier. This technique is less operator-dependent and can potentially minimize root canal wall degradation [25]. It is simpler and faster than the conventional lateral compaction technique [26]. However, some irregularities in the root canal wall may remain unfilled with this technique and serve as potential areas for the accumulation of microorganisms and reinfection [27]. Nonetheless, acceptable obturation quality of the single-cone technique has also been reported [28]. However, information regarding the seal provided by the use of a single-cone obturation technique in combination with a CC sealer is scarce. Thus, the purpose of this study was to compare the marginal adaptation of the CC sealer with the single-cone obturation technique versus the AH-26 sealer with the lateral compaction technique in single-canal teeth. The null hypothesis of the study was that no significant difference would be found in marginal adaptation between the CC sealer and the single-cone obturation technique versus the AH-26 sealer and the lateral compaction technique.

Materials and methods

This in vitro experimental study was conducted on 24 single-rooted single-canal human teeth extracted due to periodontal problems or as part of orthodontic treatment. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the university (IR.SSU.DENTISTRY.REC.1402.006).

Sample size

The minimum sample size was calculated to be 10 in each group by PASS 15 software according to a previous study [18], with a 95% confidence interval, 80% study power, a standard deviation of 3, and a 2-unit difference between the CC and AH-26 groups in terms of the mean distance between the root-filling material and canal wall.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were the presence of one single root and one single canal; the absence of cracks, fractures, root caries, or resorption; the presence of a mature apex, straight canals; and the absence of dystrophic calcification.

Teeth with defective obturations and those that were broken during sectioning were excluded and replaced.

The teeth were inspected radiographically, and also under a surgical microscope with x15 magnification to ensure absence of cracks and fractures.

Specimen preparation

The teeth were initially immersed in 5.25% sodium hypochlorite (AV Dent, Iran) for 30 min to eliminate debris. The samples were then stored in saline. A #15 K-file (Mani, Japan) was introduced into the canal. Upon observing its tip at the apex, 1 mm was subtracted from its length to determine the working length.

The root canals were cleaned and shaped by ProTaper nickel‒titanium rotary system (EF-Blue, Sentadent, China) with an endomotor (Endo Mate DT, NSK. Japan) by the crown-down technique using SX, S1, S2, F1, F2, and F3 files to the working length in an orderly manner as instructed by the manufacturer. The root canals were then irrigated with 10 mL of 17% EDTA (NikDarman, Iran), followed by the addition of 10 mL of 5.25% sodium hypochlorite for another 5 min. Finally, the root canals were irrigated with 5 mL of distilled water (Saamen, Iran) and dried.

The teeth were then randomly assigned to 2 experimental groups (n = 12).

In group 1, the root canals were obturated with CC sealer (Sarv Javid Modarres, Iran) and #30/4% gutta-percha (Aria Dent, Iran) by the single-cone technique. For this purpose, CC sealer was delivered into the canal by using a rotary instrument (Endo Mate DT, NSK. Japan) and F2 ProTaper files (EF-Blue, Sentadent, China) by contra-angle rotation of the files; this process was repeated three times to ensure that the canal walls were coated with the CC sealer.

In group 2, the root canals were obturated with AH-26 sealer (Dentsply, Switzerland) and the cold lateral compaction technique. A #35 finger spreader (Mani, Japan), #30/2% gutta-percha as the master point, and also accessory gutta-percha points (Meta BioMed, Korea) were used for this purpose. The teeth were radiographed again to ensure the optimal density of obturation. The teeth were subsequently stored at room temperature and 100% humidity for 4 weeks. Next, horizontal sections were made at the root end 3 mm from the apex with a high-speed handpiece under a water coolant.

Assessment of marginal adaptation

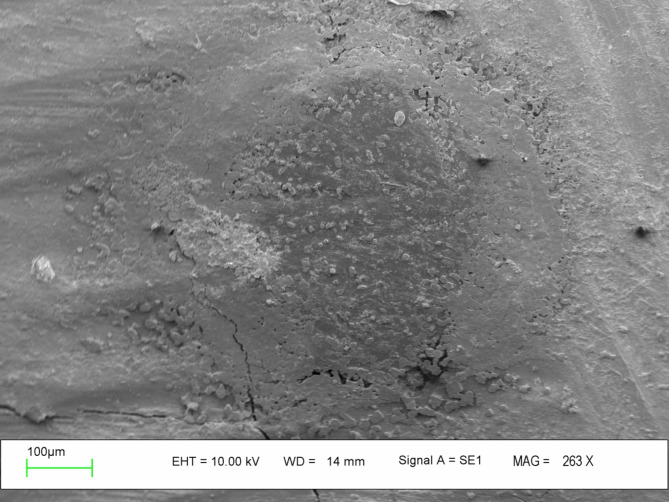

Tooth sections were inspected under a scanning electron microscope (ZEISS Leo-1430 VP, Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany) at ×205–303 magnification. For this purpose, the samples were first gold sputter coated (5 μm thick) by the plasma technique, and then the distance between the sealer and the root canal wall was measured in 4 different directions, and the mean linear distance was reported for each section in micrometers (µm) (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

SEM micrograph of the linear distance between the AH-26 sealer and the root canal wall. Separation of the sealer from the gutta-percha and dentinal wall can be observed

Fig. 2.

SEM micrograph of the linear distance between the CC sealer and the root canal wall

The specimens were coded and were then assessed microscopically. The operator was blinded to the group allocation of specimens.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the data distribution was analyzed by the Kolmogorov‒Smirnov and Shapiro‒Wilk tests, which revealed a normal distribution of data (P = 0.295) in the AH-26 group and a nonnormal distribution of data (P = 0.025) in the CC sealer group. Thus, the marginal adaptations of the two groups were compared by the nonparametric Mann‒Whitney U test at the 0.05 level of significance.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the mean linear distance (gap) was significantly smaller in the CC sealer/single-cone group than the AH-26/lateral compaction group (P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of the mean linear distance (gap) between the CC sealer/single-cone group and the AH-26/lateral compaction group in microns (µm)

| Group | Mean and std. deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AH-26/cold lateral compaction | 4.82 ± 12.94 | 13.54 | 6.83 | 23.77 | 0.001 |

| CC/single-cone | 2.57 ± 6.72 | 5.85 | 4.07 | 12.91 |

Discussion

This study compared the marginal adaptation of the CC sealer with the single-cone obturation technique versus the AH-26 sealer with the lateral compaction technique in single-canal teeth. The null hypothesis of the study was that no significant difference would be found in marginal adaptation between the two groups. The apical 2–3 mm of the root was assessed in this study since this area is the most critical part in the success of endodontic treatment [29]. The results revealed significantly higher marginal adaptation (smaller gap at the interface) in the CC sealer/single-cone obturation technique. Thus, the null hypothesis of the study was rejected. This result could be due to the formation of a layer of apatite crystals between the bioceramic sealer and the dentinal wall, which can enhance the seal [30].

A search of the literature by the authors yielded only a few studies on the properties of CC sealers. However, many studies are available on other bioceramic sealers and CC materials. Oshaghi [31] compared the solubility of the CC sealer and the AH-26 sealer and reported that both sealers had solubilitiy within the standard range. The solubilitiy of the two sealers were not significantly different on day 1. However, the solubility of the CC sealer was significantly higher than that of AH-26 after 7, 14, and 28 days, which can be attributed to its solvent. Ballullaya et al. [32] compared the microleakage of ZOE-based, epoxy resin-based, and bioceramic (EndoSequence BC) sealers and reported that EndoSequence BC had the lowest microleakage, whereas the ZOE-based sealer had the highest microleakage. They reported that the hydrophilicity of bioceramic sealers results in higher sealability than that of resin-based and ZOE-based sealers. Patri et al. [33] compared the marginal adaptation of epoxy resin-based, MTA-based, and bioceramic sealers via SEM and reported significantly higher sealability and marginal adaptation of bioceramic sealers. Their results were in line with the present findings, although they used a different bioceramic sealer in their study. Bakhtiari-nia et al. [34] compared the marginal adaptations of root canals filled with gutta-percha and CC sealer with those of gutta-percha and AH-26 sealer via SEM and reported a significantly smaller gap between the root filling and dentin in the CC group. These findings support the use of CC as a root-filling material as an alternative to gutta-percha and AH-26 sealers because of its higher sealability and superior marginal adaptation. Padmawar et al. [35] compared the marginal adaptations of EndoSequence BC, AH-26 and EndoRez via SEM and reported a significantly smaller gap at the interface in the bioceramic sealer group, which was in agreement with the present findings, although they used the EndoSequence BC bioceramic sealer. Mirzaeeian et al. [36] compared the marginal adaptations of AH-26, Endoseal MTA, and CC sealers via the lateral condensation technique and reported significant differences among the three sealers such that the CC sealer resulted in the smallest gap, whereas AH-26 yielded the largest gap at the sealer‒root dentin interface. Compared with AH-26, Bagheri-Hariri et al. [37] also demonstrated a significantly smaller gap between the CC sealer and root dentin, both of which were achieved via the lateral condensation technique. Rafiee et al. [38] compared the microleakage of root fillings with gutta-percha and AH-26 versus gutta-percha and CC sealer by the dye penetration test and reported significantly lower microleakage in the CC sealer group. The abovementioned findings were all in accordance with the present results.

However, some studies reported contrary results. Polineni et al. [39] assessed the marginal adaptation of resin-based, MTA-based, and bioceramic sealers to dentin via SEM and reported the smallest gap in the resin-based sealers. Additionally, Kim et al. [40] reported no significant difference in microleakage between Endoseal MTA and AH-Plus. Remy et al. [41] reported superior marginal adaptation of AH-Plus compared with MTA Fillapex and Endo Fill sealer. The difference between the abovementioned results and the present findings may be attributed to different methodologies, i.e., the use of different types of tests for the assessment of microleakage or marginal adaptation, duration of the experiment, formulation of sealers, or root canal instrumentation and irrigation protocols.

The optimal sealability of bioceramic sealers could be due to the formation of a layer of apatite crystals between the bioceramic sealer and the dentinal wall, which can enhance the seal [42]. The formation of this layer increases with increasing pyrophosphate activity, which is enhanced by the formation of calcium ions [42]. Khedmat et al. [43] reported that both CC and MTA can increase the enzymatic activity of alkaline phosphatase, which plays an important role in initial mineralization and the induction of HA deposition.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the bonding of bioceramic sealers to root dentin, such as the formation of biomechanical bonds by the penetration of sealer particles into dentinal tubules, the alkaline pH of these sealers, which can cause collagen denaturation and enhance sealer penetration into intertubular dentin, the reaction of phosphate with calcium silicate hydrogel and the formation of calcium hydroxide through the calcium silicate reaction in the presence of moisture in dentinal tubules, and the formation of HA [44]. Owing to the small size of bioceramic particles (2 μm), their hydrophilicity, and small contact angle, bioceramic sealers easily form chemical bonds with root dentin, fill the accessory microcanals, and create a gap-free seal. Additionally, hydrophilic sealers have higher tubular penetration than hydrophobic sealers [45, 46].

As mentioned earlier, the single-cone obturation technique is often selected for bioceramic sealers [47] and was therefore selected for root canal obturation with gutta-percha and CC sealer in the present study. Najafzade et al. compared the marginal adaptation and tubular penetration depth of bioceramic and epoxy resin sealers with cold lateral compaction and single-cone obturation techniques. They reported significantly superior marginal adaptation and higher tubular penetration depth in the coronal, middle, and apical thirds of the root in the bioceramic sealer group, irrespective of the obturation technique [48]. Thus, owing to easier and faster root canal obturation with the single-cone technique, this technique may be recommended as an alternative to the conventional cold lateral compaction technique with bioceramic sealers.

This study had some limitations. The gap at the sealer‒dentinal wall interface was measured via SEM. Although accurate, this technique has some drawbacks. For example, it only assesses the adaptation in one surface two-dimensionally. Additionally, sectioning of samples to obtain transverse cross-sections of the root may cause artifacts [49]. Additionally, the size of the gap at the sealer‒root dentin interface, which may be problematic in the clinical setting, has yet to be clearly identified. Nonetheless, it is obvious that a sealer with higher marginal adaptation is preferable for use in the clinical setting. Moreover, this study had an in vitro design and could not simulate complex intraoral conditions, such as host defense mechanisms. Thus, the results should be interpreted with caution. The limited sample size and the unavailability of several longitudinal and transverse cross-sections for a more precise assessment of the root canal system were among the other limitations of this study.

Further in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to better simulate the clinical setting and obtain more generalizable results. Also, the relationships between marginal adaptation and bacterial leakage and the development of periapical inflammation should be investigated in future studies. Additionally, future studies should assess a greater number of longitudinal and transverse root sections with different methods of microleakage assessment to obtain more comprehensive information. Finally, clinical trials on the application of CC sealer after confirming its other physical and chemical properties through in vitro investigations are needed. Last but not least, future studies with a longer period are required to assess the marginal adaptation of CC sealer in the long-term.

Conclusion

Marginal adaptation was significantly higher with the CC sealer with the single-cone obturation technique than with the AH-26/lateral compaction technique, suggesting the suitability of the CC sealer and the single-cone technique for a hermetic seal in single-canal teeth.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Author contributions

J.M. devised the study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, administrative, technical, and material support and study supervision. E.Kh. devised the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and statistical analysis. F.M.devised the study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, administrative, technical, and material support and study supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Yazd Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study complies with all the relevant regulations, institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the ethics committee of Yazd Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences (IR.SSU.DENTISTRY.REC.1402.006). This in vitro, experimental study was conducted on 24 single-rooted human teeth extracted for purposes not related to this study such as periodontal disease, and irreparable coronal caries and informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Consent for publication

Identified images or other personal or clinical details of participants are Not Applicable in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K. A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment: part 1: periapical health. Int Endod J. 2011;44(7):583–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Chevigny C, Dao TT, Basrani BR, et al. Treatment outcome in endodontics: the Toronto study–phases 3 and 4: orthograde retreatment. J Endod. 2008;34(2):131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alves FR, Andrade-Junior CV, Marceliano-Alves MF, et al. Adjunctive steps for disinfection of the Mandibular Molar Root Canal System: a correlative Bacteriologic, Micro-computed Tomography, and Cryopulverization Approach. J Endod. 2016;42(11):1667–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Economides N, Kokorikos I, Kolokouris I, Panagiotis B, Gogos C. Comparative study of apical sealing ability of a new resin-based root canal sealer. J Endod. 2004;30(6):403–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirai VH, Machado R, Budziak MC, Piasecki L, Kowalczuck A, da Silva Neto UX. Percentage of gutta-percha-, sealer-, and void-filled areas in oval-shaped root canals obturated with different filling techniques: a confocal laser scanning microscopy study. Eur J Dent. 2020;14(01):008–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee KW, Williams MC, Camps JJ, Pashley DH. Adhesion of endodontic sealers to dentin and gutta-percha. J Endod. 2002;28(10):684–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasconcelos BC, Bernardes RA, Duarte MA, Bramante CM, Moraes IG. Apical sealing of root canal fillings performed with five different endodontic sealers: analysis by fluid filtration. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19(4):324–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maden M, Gorgul G, Tinaz AC. Evaluation of apical leakage of root canals obturated with nd: YAG laser-softened gutta-percha, System-B, and lateral condensation techniques. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2002;3(1):16–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sagsen B, Er O, Kahraman Y, Orucoglu H. Evaluation of microleakage of roots filled with different techniques with a computerized fluid filtration technique. J Endod. 2006;32(12):1168–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Razmi H, Ashofteh Yazdi K, Jabalameli F, Parvizi S. Antimicrobial effects of AH26 Sealer/Antibiotic combinations against Enterococcus Faecalis. Iran Endod J. 2008;3(4):103–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pappen AF, Bravo M, Gonzalez-Lopez S, Gonzalez-Rodriguez MP. An in vitro study of coronal leakage after intraradicular preparation of cast-dowel space. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;94(3):214–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naulakha D, Hussain M, Alam M, Howlader M. An in vitro dye leakage study on apical microleakage of root canal sealers. J Nepal Dent Assoc. 2011;12(1):33–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng L, Ye F, Yang R, Lu X, Shi Y, Li L, et al. Osteoinduction of hydroxyapatite/beta-tricalcium phosphate bioceramics in mice with a fractured fibula. Acta Biomater. 2010;6(4):1569–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvalho CN, Grazziotin-Soares R, de Miranda Candeiro GT, Gallego Martinez L, de Souza JP, Santos Oliveira P, Bauer J, Gavini G. Micro push-out bond strength and Bioactivity Analysis of a Bioceramic Root Canal Sealer. Iran Endod J. 2017 Summer;12(3):343–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Jardine AP, Rosa RA, Santini MF, Wagner M, Só MV, Kuga MC, Pereira JR, Kopper PM. The effect of final irrigation on the penetrability of an epoxy resin-based sealer into dentinal tubules: a confocal microscopy study. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20(1):117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raghavendra SS, Jadhav GR, Gathani KM, Kotadia P. Bioceramics in endodontics - a review. J Istanb Univ Fac Dent. 2017;51(3 Suppl 1):S128–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasheminia SM, Nejad SL, Dianat O, Modaresi J, Mahjour F. Comparing the sealing properties of mineral trioxide aggregate and an experimental ceramic based root end filling material in different environments. Indian J Dent Res. 2013;24(4):474–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mokhtari F, Modaresi J, Javadi G, Davoudi A, Badrian H. Comparing the marginal adaptation of Cold Ceramic and Mineral Trioxide Aggregate by means of scanning Electron microscope: an in vitro study. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7(9):7–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Modaresi J, Bahrololoomi Z, Astaraki P. In vitro comparison of the apical microleakage of laterally condensed gutta percha after using calcium hydroxide or cold ceramic as apical plug in open apex teeth. J Dent. 2006;7(1, 2):63–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jahromi MZRS, Ebrahimi B. The comparative effect of cold ceramic and proroot on the inflammation of periodontal tissues after sealing furcal perforation in dog teeth (a histologic study). Dent Res J. 2006;24:439–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zareh JMRS, Esfahanian V, Feyzi G. Histological evaluation of inflammation after sealing furcating perforation in dog’s teeth by four materials. Dent Res J. 2006;3:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Modaresi J, Aghili H. Sealing ability of a new experimental cold ceramic material compared to glass ionomer. J Clin Dent. 2006;17(3):64–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Modaresi J, Talakoob M. Comparison of two root-end filling materials. J Isfahan Dent School. 2015;11(5):379–86. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parirokh M, Torabinejad M. Mineral trioxide aggregate: a comprehensive literature review–part I: chemical, physical, and antibacterial properties. J Endod. 2010;36(1):16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guivarc’h M, Jeanneau C, Giraud T, Pommel L, About I, Azim AA, et al. An international survey on the use of calcium silicate-based sealers in nonsurgical endodontic treatment. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24(1):417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomes BP, Pinheiro ET, Sousa EL, Jacinto RC, Zaia AA, Ferraz CC, et al. Enterococcus faecalis in dental root canals detected by culture and by polymerase chain reaction analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102(2):247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moinzadeh AT, Zerbst W, Boutsioukis C, Shemesh H, Zaslansky P. Porosity distribution in root canals filled with gutta percha and calcium silicate cement. Dent Mater. 2015;31(9):1100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira AC, Nishiyama CK, de Castro Pinto L. Single-cone obturation technique: a literature review. RSBO Revista sul-brasileira De Odontologia. 2012;9(4):442–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alothmani OS, Chandler NP, Friedlander LT. The anatomy of the root apex: a review and clinical considerations in endodontics. Saudi Endod j. 2013;3(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaur M, Singh H, Dhillon JS, Batra M, Saini M. MTA versus Biodentine: review of literature with a comparative analysis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(8):ZG01–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oshshaghi M. comparison of solubility of Cold Ceramic sealer and AH26 sealer [dissertation]. Yazd: Shahid sadoughi university of medical sciences; 2024.

- 32.Ballullaya SV, Vinay V, Thumu J, Devalla S, Bollu IP, Balla S. Stereomicroscopic dye leakage measurement of six different Root Canal Sealers. J Clin Diagn Research: JCDR. 2017;11(6):ZC65–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patri G, Agrawal P, Anushree N, Arora S, Kunjappu JJ, Shamsuddin SV. A Scanning Electron Microscope Analysis of Sealing Potential and marginal adaptation of different Root Canal Sealers to dentin: an in Vitro study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2020;21(1):73–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakhtiari-nia Z. Experimental evaluation and comparison of marginal adaptation of obturated root canals with Gutta Percha and cold ceramic [dissertation]. Yazd: Shahid sadoughi university of medical sciences; 2021.

- 35.Padmawar N, Moapagr V, Vadvadgi V, Vishwas J, Joshi S, Padubidri M. Scanning Electron microscopic evaluation of marginal adaptation of three endodontic sealers: an Ex-vivo Study. J Pharm Res Int. 2021:49–57.

- 36.Mirzaeeian A. Comparison of the marginal adaptation of different root canal sealers with the dentin using an electron microscope: An in vitro study [dissertation]. Yazd: Shahid sadoughi university of medical sciences; 2023.

- 37.Bagheri-Hariri A. Comparing the marginal adaptation of an AH26 sealer with a bioceramic CC sealer by means of Scanning Electron Microscope [master’s thesis]. Yazd: Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciencess; 2023.

- 38.Rafiee F. comparison of microleakage of filled canals with cold ceramic sealer and AH26 sealer by dye penetration method [dissertation]. Yazd: Sahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences; 2024.

- 39.Polineni S, Bolla N, Mandava P, Vemuri S, Mallela M, Gandham VM. Marginal adaptation of newer root canal sealers to dentin: a SEM study. J Conserv Dent. 2016;19(4):360–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim M, Park H, Lee J, Seo H. Microleakage assessment of a pozzolan cement-based mineral trioxide aggregate root canal sealer. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 2017;44(1):20–7. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Remy V, Krishnan V, Job TV, Ravisankar MS, Raj CVR, John S. Assessment of marginal adaptation and sealing ability of Root Canal Sealers: an in vitro study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2017;18(12):1130–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maru V, Dixit U, Patil RSB, Parekh R. Cytotoxicity and bioactivity of Mineral Trioxide Aggregate and Bioactive Endodontic Type cements: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2021;14(1):30–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khedmat S, Sarraf P, Seyedjafari E, Sanaei-Rad P, Noori F. Comparative evaluation of the effect of cold ceramic and MTA-Angelus on cell viability, attachment and differentiation of dental pulp stem cells and periodontal ligament fibroblasts: an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Haddad A, Che Ab Aziz ZA. Bioceramic-based Root Canal Sealers: a review. Int J Biomater. 2016;2016:9753210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pius A, Mathew J, Theruvil R, George S, Paul M, Baby A, Jacob J. Evaluation and comparison of the marginal adaptation of an epoxy, calcium hydroxide-based, and bioceramic-based root canal sealer to root dentin by SEM analysis: an in vitro study. Cons Dent Endod J. 2019;4:6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 46.El Hachem R, Khalil I, Le Brun G, Pellen F, Le Jeune B, Daou M, El Osta N, Naaman A, Abboud M. Dentinal tubule penetration of AH Plus, BC Sealer and a novel tricalcium silicate sealer: a confocal laser scanning microscopy study. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(4):1871–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sayed ME, Al Husseini MAA. Apical dye leakage of two single-cone root canal core materials (hydrophilic core material and gutta-percha) sealed by different types of endodontic sealers: an in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2018;21(2):147–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Najafzadeh R, Fazlyab M, Esnaashari E. Comparison of bioceramic and epoxy resin sealers in terms of marginal adaptation and tubular penetration depth with different obturation techniques in premolar teeth: a scanning electron microscope and confocal laser scanning microscopy study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(5):1794–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohammed A, Abdullah A. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM): A review. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Hydraulics and Pneumatics—HERVEX, Băile Govora, Romania. 2018 (Vol. 2018, pp 7–9).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.