Abstract

BACKGROUND

Eagle syndrome is characterized by an elongated styloid process causing mechanical stress on the internal carotid artery (ICA). The authors present the case of a patient who had cervical ICA dissection with a nonelongated styloid process.

OBSERVATIONS

A 43-year-old man presented with left hemiparesis and hemispatial neglect. The patient underwent endovascular treatment for tandem occlusion of the M1 segment of the right middle cerebral artery and right cervical ICA. After M1 segment thrombectomy, stenting of the right cervical ICA dissection was performed. Notably, the tip of the styloid process matched the caudal end of the dissection cavity, which was located on the lateral side of the ICA, where the styloid process was located. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that mechanical stress from the styloid process caused ICA dissection. After reducing antiplatelet therapy, the styloid process was surgically removed.

LESSONS

Mechanical stress from a nonelongated styloid process can lead to ICA dissection–induced occlusion. In patients with cervical ICA dissection, the anatomical relationship between the styloid process and dissection site, as well as the distance between the ICA and styloid process, should be evaluated.

Keywords: dissection, Eagle syndrome, stent, styloid process

ABBREVIATIONS: ASPECTS = Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT Score, CAS = carotid artery stenting, CT = computed tomography, ICA = internal carotid artery, MCA = middle cerebral artery, MRA = magnetic resonance angiography.

Eagle syndrome is a condition in which an elongated styloid process mechanically irritates the internal carotid artery (ICA) or glossopharyngeal nerve, causing symptoms such as ischemic stroke, dysphagia, and ear pain. Classic Eagle syndrome typically presents with pharyngeal pain and swallowing difficulties due to nerve compression, whereas vascular Eagle syndrome primarily involves ICA dissection.1 Historically, attention has been focused on styloid process elongation in vascular Eagle syndrome.2, 3 Moreover, the average age at onset of vascular Eagle syndrome is 52.1 years, which is lower than the typical onset of cerebral infarction.4 We present a case of tandem occlusion caused by ICA dissection secondary to a nonelongated styloid process in an adult.

Illustrative Case

History and Examination

A 43-year-old man experienced a headache after neck hyperextension the night before admission. He was last known to be well at 7:00 am the following morning. While taking a bath, the patient developed movement difficulty and was transported to our hospital 90 minutes after the last known time of wellness. He had no pertinent medical history or history of head or neck trauma or surgery. He was a social drinker and a nonsmoker. Upon arrival at the hospital, the patient presented with left hemiparesis, left hemispatial neglect, and dysarthria, scoring 15 on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

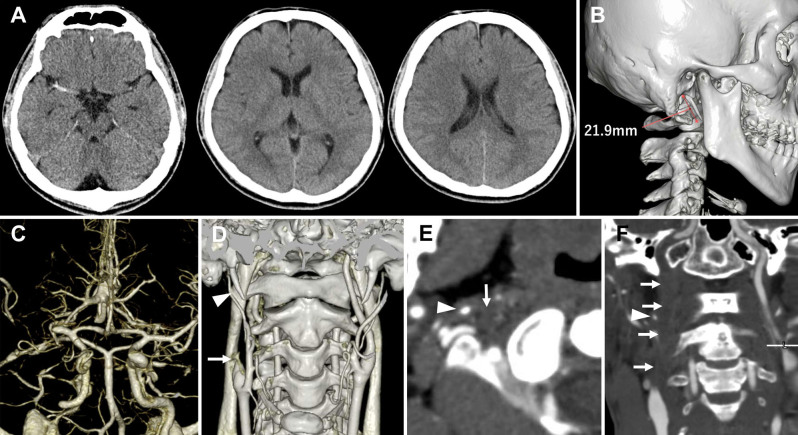

Blood tests, chest radiography, and electrocardiography revealed no abnormalities. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) revealed a hyperdense sign in the M1 segment of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) and early ischemic changes in the right frontal lobe, resulting in an Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT Score (ASPECTS) of 9 (Fig. 1A). The length of the right styloid process was 21.9 mm (Fig. 1B), and there was no calcification of the stylohyoid chain. CT angiography revealed tandem occlusion of the right M1 segment and right cervical ICA (Fig. 1C and D). The distance between the right ICA and styloid process was 2.0 mm (Fig. 1E and F). The distance between the left ICA and styloid process was 1.5 mm. Subsequently, tissue plasminogen activator (0.6 mg/kg) was administered intravenously.

FIG. 1.

Initial imaging findings before endovascular surgery. Noncontrast CT (A) shows a hyperdense sign in the right MCA, with an ASPECTS of 9. A three-dimensional (3D)–reconstructed image from noncontrast CT (B) shows a 21.9-mm-long right styloid process. CT angiography reveals right MCA occlusion (C). A 3D-reconstructed CT angiography image (D) shows occlusion of the right cervical ICA (arrow) and right styloid process (arrowhead). Axial (E) and coronal (F) CT angiography sections show the right styloid process (arrowhead) in proximity (2.0 mm) to the right ICA (arrows).

Endovascular Surgery

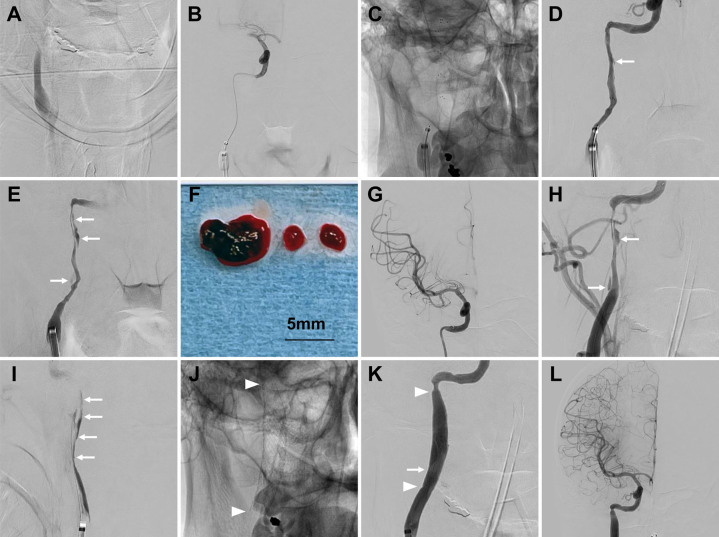

Endovascular surgery was performed 35 minutes after admission. With the patient under local anesthesia, a 9-Fr balloon guide catheter (Optimo, Tokai Medical Products) was placed into the right common carotid artery via the right femoral artery. Heparin was intravenously administered to maintain an activated clotting time of > 200 seconds during surgery. Angiography revealed no stenosis at the origin of the right ICA, but a tapering occlusion was noted in the cervical ICA (Fig. 2A). The 9-Fr Optimo catheter was advanced to the origin of the right ICA. A React 71 aspiration catheter (Medtronic) was guided to the proximal portion of the cervical ICA occlusion, and a Phenom 21 microcatheter (Medtronic) and a Traxcess 14 microguidewire (Terumo) were passed through the cervical ICA occlusion. Microangiography revealed a patent right petrous ICA and right M1 segment occlusion (Fig. 2B). A 6 × 40–mm stent retriever (Solitaire, Medtronic) was deployed to the occlusion site (Fig. 2C). Postdeployment angiography revealed ICA recanalization with contrast flowing along the wall, indicating dissection (Fig. 2D). As a thrombus was possibly present at the ICA occlusion, the Solitaire was retracted into the React 71 aspiration catheter, which was then withdrawn into the Optimo catheter; however, this maneuver failed to retrieve the thrombus. At this time, angiography showed recanalization of the right ICA with narrowing at the dissection site (Fig. 2E). We opted to first perform thrombectomy to recanalize the MCA occlusion. Using a combined technique of retracting a 4 × 40–mm Solitaire stent retriever into the React 71 aspiration catheter navigated to the proximal end of the thrombus, we retrieved a red thrombus from the right M1 segment (Fig. 2F). Angiography confirmed complete recanalization of the right MCA (Fig. 2G).

FIG. 2.

Imaging findings during endovascular surgery, frontal (A–E, G, H, and J–L) and lateral (I) views. Right common carotid artery angiography (A) shows a tapering occlusion of the right ICA. Microangiography (B) of the right ICA shows occlusion of the M1 segment of the MCA. Native imaging (C) shows the deployment of a stent retriever to the occlusion site in the right cervical ICA. After stent retriever deployment, right ICA angiography (D) reveals ICA recanalization with contrast flowing along the wall (arrow). Angiography (E) after retraction of the stent retriever shows recanalization of the right ICA with narrowing at the dissection site (arrows). The retrieved red thrombus from the M1 segment (F). Angiography (G) of the right ICA after thrombectomy confirms complete recanalization of the right MCA. Right ICA angiography (H) after distal filter protection device deployment shows narrowing and dissection (arrows) of the cervical ICA. Venous phase of the right ICA angiography (I) shows the extent of dissection (arrows). Native imaging (J) shows the distal and proximal ends of the deployed carotid artery stent (arrowheads). Poststenting angiography of the right ICA shows successful stent expansion (arrowheads, K) and the caudal end of the dissection cavity (arrow) and patent right ICA and MCA (L).

Subsequently, carotid artery stenting (CAS) was performed to treat the cervical ICA dissection. After confirming the absence of intracranial hemorrhage on Xper CT (Philips Healthcare), aspirin (200 mg) and prasugrel (20 mg) were administered. A 5-mm distal filter protection device (Spider FX, Medtronic) was deployed to the petrous segment of the right ICA. Angiography revealed narrowing and dissection of the cervical ICA (Fig. 2H and I). A 7 × 40–mm carotid artery stent (Precise, Cordis) was deployed to cover the dissection (Fig. 2J). Poststent angiography revealed successful stent expansion and no embolic events in the right ICA (Fig. 2K and L).

Postoperative Course

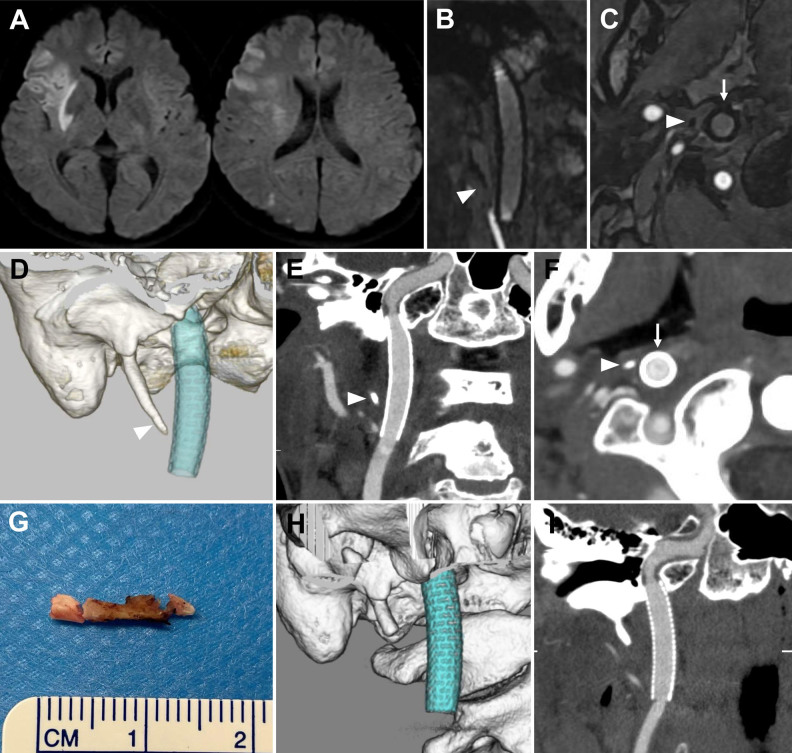

The patient’s neurological symptoms improved immediately after surgery. On the following day, diffusion-weighted imaging revealed cerebral infarction in the right putamen, corona radiata, insular cortex, frontal cortex, and parietal cortex (Fig. 3A). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed that the tip of the styloid process was close to the stented right ICA (Fig. 3B and C); CT also showed the proximity of the styloid process to the right ICA (Fig. 3D–F). The tip of the styloid process corresponded to the caudal end of the dissection cavity, which was located on the lateral side of the ICA (Figs. 2H–K and 3B- F). Based on these findings, the dissection of the ICA can be attributed to the mechanical stress generated by the styloid process. The patient was maintained on aspirin 100 mg/day and prasugrel 3.75 mg/day. Thereafter, mild left facial paresis gradually improved, and the patient was discharged on day 17 with a modified Rankin Scale score of 0. Antiplatelet therapy was reduced to aspirin 100 mg/day at 12 weeks after endovascular treatment, and transcervical styloidectomy was performed 15 weeks after endovascular treatment (Fig. 3G). Postoperatively, the distance between the styloid process and stent increased to 6.3 mm (Fig. 3H and I). During a 5-month follow-up after the last procedure, no recurrence of cerebral infarction was observed.

FIG. 3.

Imaging findings after endovascular surgery. Arrows indicate the ICA, and arrowheads indicate the styloid process. Diffusion-weighted imaging (A) the day after surgery shows high signal intensity in the right putamen, corona radiata, insular cortex, frontal cortex, and parietal cortex. Coronal (B) and axial (C) MRA images show the styloid process in close proximity to the stented right ICA. CT 3D reconstruction (D) and coronal (E) and axial (F) sections from CT angiography show the styloid process tip located 1.4 mm from the stent. Image (G) of the styloid process after resection of a 14-mm portion. Poststyloidectomy CT 3D reconstruction (H) and coronal section (I) from contrast-enhanced CT show an increased distance between the remaining styloid process and stent.

Informed Consent

The necessary informed consent was obtained in this study.

Discussion

Observations

A styloid process is typically considered elongated if it is longer than 30 mm.1 The relationship between ICA dissection and styloid process length has been previously reported. In particular, the styloid process was significantly longer in dissection cases than in nondissection cases, as reported by Raser et al. (30.3 vs 26.6 mm, p = 0.03) and Muthusami et al. (38.9 vs 36.2 mm, p = 0.05).2, 3 Therefore, an elongated styloid process has been considered a risk factor for ICA dissection. However, regardless of styloid process length, the average distance from the styloid process to the external surface of the ICA in patients with dissection was reported to be only 5.6 ± 2.1 mm; this close proximity has also been identified as a risk factor for dissection.5 In our case, the symptomatic styloid process measured 21.9 mm and was not elongated, but it was close to the external surface of the ICA by only 2.0 mm, and its tip corresponded to the caudal end of the dissection. Therefore, the dissection was attributed to mechanical stress from the styloid process. In addition to the styloid process length, the distance between the styloid process and ICA should be considered a factor that adds mechanical stress on the ICA.

There have been previous reports on ICA dissection induced by neck rotation toward the dissection side and dissecting aneurysms that develop after neck hyperextension.6, 7 In our case, the patient experienced headache after neck hyperextension, suggesting that neck movement triggered ICA dissection. Even if the styloid process did not directly compress the ICA, repetitive microvascular trauma caused by neck movement could have eventually led to dissection. In previous studies on stylocarotid syndrome, postoperative stent fracture and occlusion and recurrent cerebral infarction were observed.8, 9 After CAS, cerebral infarction due to mechanical stress from the remaining styloid process has been reported to recur anytime from several days to 3 months after the initial stroke.9 In our patient, styloidectomy was deemed necessary to prevent the recurrence of cerebral infarction. The decision to perform surgery was made after reducing antiplatelet therapy from 2 antiplatelet drugs per day to aspirin 100 mg/day, considering both the lack of recurrence and the bleeding risk associated with dual antiplatelet therapy.

There have been case reports on bilateral Eagle syndrome, in which both styloid processes caused stress on the ICAs, leading to dissection;10 however, in general, conservative management rather than preventive surgery is recommended for the asymptomatic side.11 In our patient, although the styloid process on the asymptomatic left side was close to the ICA (1.5 mm), follow-up observation was chosen because the patient remained asymptomatic on the left side.

For the treatment of tandem occlusions, 2 thrombectomy approaches have been proposed. The anterograde approach first attempts to recanalize the cervical ICA, whereas the retrograde approach first addresses intracranial occlusion. Both approaches yield similar outcomes in terms of improvement in activities of daily living and symptomatic hemorrhage.12 In patients with dissection, we prefer the retrograde approach because it allows rapid intracranial reperfusion and assessment of hemorrhage before considering CAS of the cervical ICA. In this case, ICA dissection was diagnosed first after deploying the stent retriever to the occlusion site. At that time, we considered that retracting the stent retriever at the dissection site could worsen the dissection, despite the fact that the thrombus remained. In retrospect, it may have been better to resheathe the stent retriever and prioritize the MCA occlusion after diagnosing the dissection.

The safety of acute CAS for tandem lesions caused by ICA dissection has been reported.13 In this patient, emergency CAS was performed to maintain ICA patency. Considering the requirement for antiplatelet therapy, Xper CT was used to evaluate the risk of postoperative intracranial hemorrhage before CAS.

Lessons

Mechanical stress from a nonelongated styloid process can cause occlusion due to ICA dissection. For patients with cervical ICA dissection, it is crucial to assess the positional relationship between the styloid process and dissection as well as the distance between the ICA and styloid process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Enago for English-language editing services.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Ikeda, Osuki. Acquisition of data: Ikeda, Osuki, Hata. Analysis and interpretation of data: Ikeda. Drafting the article: Ikeda, Osuki, Kurosaki. Critically revising the article: Ikeda, Chin. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: Ikeda, Osuki, Uezato, Fujiwara, Kinosada, Kurosaki. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Ikeda. Administrative/technical/material support: Ikeda, Fujiwara. Study supervision: Chin.

Supplemental Information

Previous Presentations

This work was presented as a poster at the 83rd Annual Meeting of the Japan Neurosurgical Society, Yokohama, Japan, October 16–18, 2024.

Correspondence

Hiroyuki Ikeda: Kurashiki Central Hospital, Kurashiki, Japan. hiroyuki.ikeda930@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Pagano S, Ricciuti V, Mancini F, et al. Eagle syndrome: an updated review. Surg Neurol Int. 2023;14:389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raser JM, Mullen MT, Kasner SE, Cucchiara BL, Messé SR. Cervical carotid artery dissection is associated with styloid process length. Neurology. 2011;77(23):2061-2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muthusami P, Kesavadas C, Sylaja PN, Thomas B, Harsha KJ, Kapilamoorthy TR. Implicating the long styloid process in cervical carotid artery dissection. Neuroradiology. 2013;55(7):861-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torikoshi S, Yamao Y, Ogino E, Taki W, Sunohara T, Nishimura M. A staged therapy for internal carotid artery dissection caused by vascular Eagle syndrome. World Neurosurg. 2019;129:133-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venturini G, Vuolo L, Pracucci G, et al. The proximity between styloid process and internal carotid artery as a possible risk factor for dissection: a case–control study. Neuroradiology. 2023;65(5):915-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demirtaş H, Kayan M, Koyuncuoğlu HR, Çelik AO, Kara M, Şengeze N. Eagle syndrome causing vascular compression with cervical rotation: case report. Pol J Radiol. 2016;81:277-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brassart N, Deforche M, Goutte A, Wery D. A rare vascular complication of Eagle syndrome highlighted by CTA with neck flexion. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15(8):1408-1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hooker JD, Joyner DA, Farley EP, Khan M. Carotid stent fracture from stylocarotid syndrome. J Radiol Case Rep. 2016;10(6):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sveinsson O, Kostulas N, Herrman L. Internal carotid dissection caused by an elongated styloid process (Eagle syndrome). BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vigilante N, Khalife J, Badger CA, et al. Surgical management of stylocarotid Eagle syndrome in a patient with bilateral internal carotid artery dissection: illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2024;7(5):CASE23682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldino G, Di Girolamo C, De Blasis G, Gori A. Eagle syndrome and internal carotid artery dissection: description of five cases treated in two Italian institutions and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;67:565.e17-565.e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Donna A, Muto G, Giordano F, et al. Diagnosis and management of tandem occlusion in acute ischemic stroke. Eur J Radiol Open. 2023;11:100513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marnat G, Lapergue B, Sibon I, et al. Safety and outcome of carotid dissection stenting during the treatment of tandem occlusions: a pooled analysis of TITAN and ETIS. Stroke. 2020;51(12):3713-3718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]