Abstract

The correct synthesis and degradation of proteins are vital for numerous biological processes in the human body, with protein degradation primarily facilitated by the ubiquitin‐proteasome system. The SKP1‐CUL1‐F‐box (SCF) E3 ubiquitin ligase, a member of the Cullin‐RING E3 ubiquitin ligase (CRL) family, plays a crucial role in mediating protein ubiquitination and subsequent 26S proteasome degradation during normal cellular metabolism. Notably, SCF is intricately linked to the pathogenesis of various diseases, including malignant tumors. This paper provides a comprehensive overview of the functional characteristics of SCF complexes, encompassing their assembly, disassembly, and regulatory factors. Furthermore, we discuss the diverse effects of SCF on crucial cellular processes such as cell cycle progression, DNA replication, oxidative stress response, cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell differentiation, maintenance of stem cell characteristics, tissue development, circadian rhythm regulation, and immune response modulation. Additionally, we summarize the associations between SCF and the onset, progression, and prognosis of malignant tumors. By synthesizing current knowledge, this review aims to offer a novel perspective for a holistic and systematic understanding of SCF complexes and their multifaceted functions in cellular physiology and disease pathogenesis.

Keywords: CUL1, disease progression, F‐box, molecular target, SKP1

SCF complexes are widely involved in intracellular metabolism. In this paper, we discuss the diverse effects of SCF on crucial cellular processes such as cell cycle progression, cell migration, biological rhythms, DNA replication, cell differentiation, cell, apoptosis, immune response, and disease occurrence.

1. INTRODUCTION

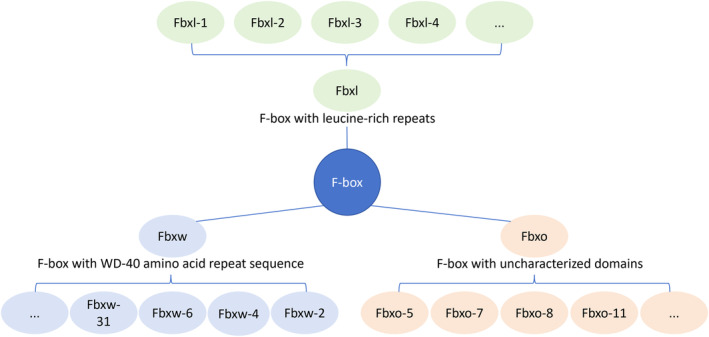

The SCF complex comprises four essential components: RING, CUL1, SKP1, and F‐Box. The scaffold protein CUL1 (cullin‐1) binds to the adaptor protein SKP1 and the substrate recognition protein F‐box at its N‐terminal. Additionally, the C‐terminal binds to the RING protein RBX1 (also known as ROC1) or RBX2/SAG, which interacts with the E2 ubiquitin‐conjugating enzyme. F‐box proteins are categorized into three subfamilies: Fbxl (F‐box with leucine‐rich repeats), Fbxw (F‐box with WD‐40 amino acid repeat sequence), and Fbxo (F‐box with uncharacterized domains) (Figure 1). The human genome contains approximately 22 Fbxl, 10 Fbxw, and 37 Fbxo proteins, alongside other F‐box proteins. The assembly of F‐box with RING, CUL1, and SKP1 forms the SCF (F‐box) complex, such as SCF (Fbxw7).

FIGURE 1.

F‐box proteins are categorized into three subfamilies. Fbxl (F‐box with leucine‐rich repeats), Fbxw (F‐box with WD‐40 amino acid repeat sequence), and Fbxo (F‐box with uncharacterized domains).

2. FUNCTIONAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SCF COMPLEX

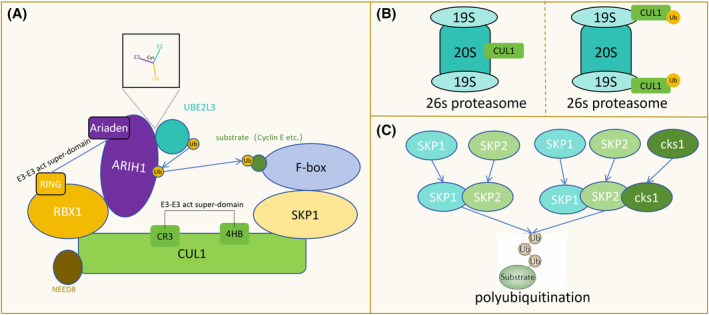

Numerous studies have revealed that same SCF complexes post‐neddylation within cells can assemble into ‘E3‐E3’ superassemblies with other CRLs (Cullin‐RING E3 ligases) and ARIH1 (an E3 ligase). In this process, ubiquitin is transferred from the E2 enzyme UBE2L3, which binds to ARIH1, to the catalytic cysteine of ARIH1, and subsequently to the substrate of the SCF complex. This multifunctional ‘E3‐E3’ superassembly likely serves as the foundation for extensive ubiquitination (Figure 2A). 1 Moreover, polyubiquitination by SCF necessitates the conversion of inactive Cdc34 monomers into highly active GST‐Cdc34 or FKBP‐Cdc34 heterodimers to enhance ubiquitin‐ubiquitin (Ub‐Ub) ligation. 2 Notably, the compatibility of amino acids surrounding the lysine residue of the substrate protein with the E2 catalytic core amino acids influences substrate lysine selection. 3

FIGURE 2.

Functional characteristics of the SCF complex. (A) Both SCF and ARIH1 serve as E3 ubiquitin ligases. A ‘E3‐E3’ super‐domain is formed, involving the CR3 and 4HB fragments of the CUL1 component of SCF and the RING of TBX1 with the Ariaden fragment of ARIH1. Ubiquitin is transferred from the E2 ubiquitin enzyme UBE2L3, which binds to ARIH1, to the catalytic cysteine of ARIH1, and subsequently to the substrate of SCF. (B) During the degradation of substrates mediated by SCF through the 26S proteasome, CUL1 binds to the 20S subcomplex, and the ubiquitinated CUL1 binds to the 19S subcomplex. (C) SKP1 can form SKP1‐SKP2 and SKP1‐SKP2‐cks1 complexes to regulate the polyubiquitination of substrates.

During the 26S proteasome‐mediated degradation of substrates facilitated by SCF, the involvement of the 26 s proteasome (consisting of a 20s subcomplex and two 19 s subcomplexes) is required, the ubiquitinated Cul1 subunit initially binds to the 20S subcomplex of the proteasome. Ubiquitination or neddylation subsequently promotes its binding to the 19S subcomplex without affecting the stability of Cul1 (Figure 2B). 4 The H6, H7, and H8 helices of the Skp1 subunit play crucial roles in recognizing and locking the F‐box. Moreover, complexes like Skp1‐Skp2 and Skp1‐Skp2‐cks1, formed by Skp1 and Skp2, facilitate the polyubiquitination of diverse substrates (Figure 2C). 5 The F‐box component dictates the substrate specificity of SCF. Certain F‐box proteins have multiple subtypes, exemplified by Fbxw7 with three subtypes: Fbxw7α, Fbxw7β, and Fbxw7γ. Depending on the D domain, different Fbxw7 subtypes can form homologous or heterologous dimers and collectively participate in Cyclin E degradation. 6 As an E3 ubiquitin ligase, SCF is directly or indirectly involved in various cellular functions and is regulated by various mechanisms. The efficacy of these regulations hinges on their effects on substrates, F‐box proteins, Cul1 components, Skp1 components, and more. Additionally, phosphorylation plays a pivotal role in the function of F‐box proteins, which will be discussed in greater detail later.

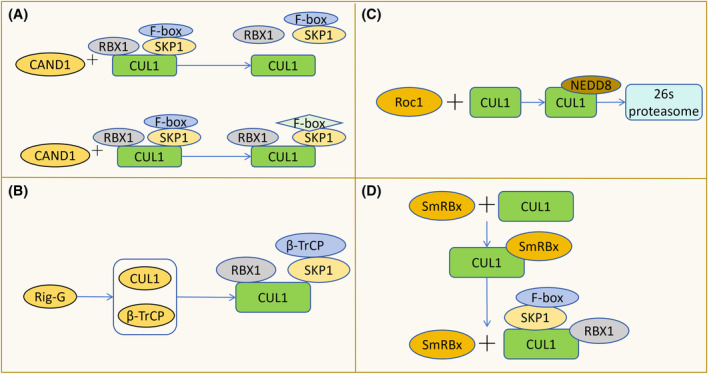

3. ASSEMBLY, DECOMPOSITION OF SCF, AND INFLUENCING FACTORS

The content and binding process of SCF components are influenced by proteins like CAND 1 and interferon, regulating the assembly and decomposition of SCF complexes. CAND1 plays a crucial role in SCF assembly; it binds to and allosterically modifies inactive SCF complexes, leading to the complete recovery of Cul1. CAND1 stimulates the assembly of new SCF complexes by facilitating the exchange of the Skp1‐F‐box protein substrate receptor module. Notably, the activation of SCF complexes requires the degradation of CAND1 (Figure 3A). 7 Additionally, the interferon‐induced antiproliferative protein Rig‐G inhibits the assembly and activity of SCF by down‐regulating CSN5, key components of the COP9 signalosome (CSN). Rig‐G also down‐regulates Cul1 and β‐TrCP, further inhibiting the assembly of SCF (β‐TrCP) (Figure 3B). 8 In vitro, Cul1 is pseudo‐primed by Roc1 and subsequently degraded via the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway, leading to the inhibition of SCF assembly (Figure 3C). 9 Conversely, in worms, SmRbx promotes SCF assembly by binding to Cul1 (Figure 3D). 10

FIGURE 3.

The assembly and disassembly of SCF and its influencing factors. (A) CAND1 binds to and allosterically modulates inactive SCF complexes, causing the separation of CUL1 from RBX1 and SKP1, thereby facilitating the recovery of CUL1. It can also replace the substrate receptor module F‐box, promoting the synthesis of new SCF complexes. (B) Rig‐G inhibits the assembly of SCF (β‐TrCP) by down‐regulating the levels of CUL1 and β‐TrCP. (C) Roc1 promotes the binding of Nedd8 to CUL1, leading to the degradation of CUL1 by the 26S proteasome, thereby inhibiting the assembly of SCF. (D) SmRBx binds to CUL1 to facilitate the assembly of SCF complexes and then dissociates from CUL1.

4. SCF AND CELL CYCLE PROGRESSION, AND BIOLOGICAL RHYTHMS

4.1. G0/G phase

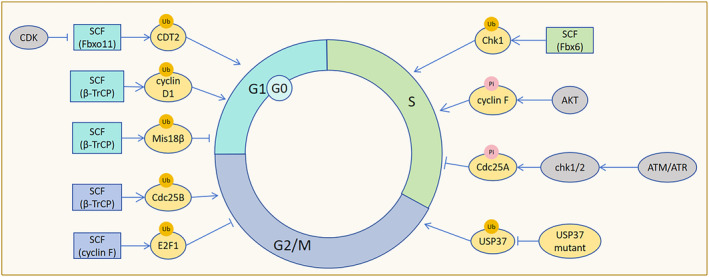

SCF (β‐TrCP) exclusively targets and degrades Mis18β during interphase, thereby restricting the function of the Mis18 complex and subsequently influencing centromere function during the transition from late mitosis to G1 phase. 11 Additionally, SCF (Fbx4‐alphaB crystallin) promotes the ubiquitin‐dependent degradation of Thr (286)‐phosphorylated cyclin D1, thereby accelerating G1 phase progression. 12 What needs attention is that some researchers have pointed out that four SCF‐type ubiquitin ligase (SCF‐Fbxo4, SCF‐Fbxw8, SCF‐Skp2, SCF‐Fbxo31) have no effect on the half‐life of cyclin D1. 13 It has also been suggested that the main regulator of cyclin D is CRL4 (AMBRA1). 14 , 15 Moreover, CDK‐mediated phosphorylation of Thr (464) on CDT2 prevents recognition by SCF (Fbxo11), thereby impeding cell progression from G0/G1 to S phases (Figure 4). 16

FIGURE 4.

SCF regulation of cell cycle progression. SCF (β‐TrCP) ubiquitinates and degrades Mis18β, inhibiting centromere function to limit cell entry into the G1 phase. SCF (β‐TrCP) also promotes the ubiquitin‐dependent degradation of cyclin D1, promoting G1 phase progression. CDK inhibits SCF (Fbxo11) recognition of CDT2 to prevent cells from exiting the G0/G1 phase. SCF (Fbx6) ubiquitinates and degrades Chk1 to terminate the S‐phase checkpoint and promote cell entry into the S phase. AKT phosphorylation of cyclin F accelerates G0/G1 arrested cells into the S phase. Upon activation by ATM and ATR, Chk1/2 phosphorylates Cdc25A to stimulate SCF (β‐TrCP) to down‐regulate Cdc25A, delaying cells in the S phase. Phosphorylation site mutant USP37 resists the ubiquitination and degradation of SCF (β‐TrCP), hindering the transition of cells from the G2 phase to the M phase. SCF (cyclin F) ubiquitinates and degrades E2F1, impeding cell G2/M phase progression. SCF (β‐TrCP) mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of Cdc25B, which promotes cell G2/M phase progression by binding to the non‐phosphorylated motif of Cdc25B.

4.2. S phase

SCF (Fbx6) mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of checkpoint kinase Chk1, terminating the S‐phase checkpoint before cells enter S phase. 17 Deletion of cyclin F disrupts SCF (cyclin F)‐mediated degradation of Cdh1 and delays cell entry into S phase. 18 SCF(Skp2) affects the degradation of p21 and p27 during the S phase of the cell cycle. 19 , 20 Additionally, AKT kinase phosphorylation of cyclin F accelerates cell cycle progression from G0/G1 to S phase, but ultimately inhibits cell proliferation due to DNA replication damage. Mutant cyclin F, resistant to AKT phosphorylation, blocks cell entry into S phase. 21 Furthermore, SCF (Fbx4) facilitates cyclin D1 degradation post G1/S transition to ensure DNA replication fidelity. 22 In addition, CRL4 (AMBRA1) directly ubiquitylates cyclin D1 and promotes subsequent degradation. 14 , 15 DNA damage or replication stalling during S phase activates ATM and ATR protein kinases, leading to hyperphosphorylation of Cdc25A. This triggers SCF (β‐TrCP)‐mediated degradation of Cdc25, delaying cell cycle progression and maintaining genomic stability. 23

The absence of F‐box protein Dia2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae SCF (Dia 2) complex leads to premature entry into S phase and DNA damage. Loss of SCF (Dia2) function results in DNA damage accumulation in S and G2/M phases, which could be mitigated by extending G1 phase (Figure 4). 24

4.3. G2/M phase

Mutations in the ubiquitin‐specific protease USP37 phosphorylation site resist recognition by SCF (β‐TrCP), hindering G2/M transition. 25 E2F1, E2F2, and E2F3A, the three activators are key regulators of the G1/S transition, interacting with the cyclin box of cyclin F via their conserved N‐terminal cyclin binding motifs. 26 SCF (cyclin F) mediates E2F1 ubiquitination and degradation in G2/M phase. E2F1 accumulation following cyclin F deletion impedes DNA replication. Concurrent deletion of cyclin F and Chk1, in the absence of checkpoint control, causes uncontrolled E2F1 activity, leading to DNA replication errors. 27 Moreover, ATR and SCF (cyclin F) synergistically degrade cell cycle progression factors, inhibiting premature stem cell exit dormancy. Cyclin F deficiency stimulates muscle stem cells to exit the resting state. 28 In G2/M phase, β‐TrCP in the SCF(β‐TrCP) complex binds to the non‐phosphorylated DDG motif of Cdc25B, promoting degradation and facilitating cell cycle progression (Figure 4). 29

4.4. SCF in biological rhythms regulation

SCF (Fbxl3) regulates biological rhythms by ubiquitinating and degrading cryptochrome (Cry). 30 Up‐regulation of Cry1 significantly enhances SCF (Fbxl3) formation. Furthermore, an unidentified protein binds to the COOH‐terminal domain of Fbxl3, inhibiting SCF (Fbxl3) formation. 31 Non‐functional I364T‐Fbxl3 mutant cells results in 26‐h‐period phenotypes in mice, indicating that FBXL3 plays an important role in circadian period determination. 32 β‐TrCP stabilizes the circadian clock by directly mediating Per1 degradation, thus controlling endogenous Per1 activity. 33

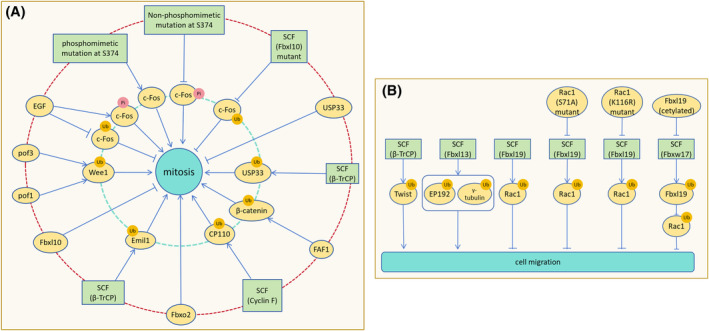

5. SCF IN REGULATION OF CELL PROLIFERATION AND MIGRATION

The SCF complex modulates the rate of cell mitosis entry and cell behavior during mitosis and proliferation by regulating substrate levels, centrosome numbers, and other factors. Following germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) in mammalian oocytes, SCF (β‐TrCP) promotes the degradation of early mitotic inhibitor 1 (Emi1), enhancing anaphase‐promoting complex (APC) activity and facilitating mitosis. 34 Importantly, the in vitro ubiquitinylation and the mitotic degradation of Emi1 are dependent on the availability of Ser145 and Ser149, which are present in a canonical β‐Trcp1 binding site conserved in Emi1 orthologs. 35 The nucleolar tumor suppressor protein SCF(Fbxl10) down‐regulates ribosomal RNA gene transcription to control cell growth. 36 Epidermal growth factor (EGF) phosphorylation S(374) of c‐Fos antagonizes SCF (Fbxl10)‐mediated ubiquitination and degradation S(374) of c‐Fos, thereby promoting cell proliferation. Dephosphorylation and pseudophosphorylation of c‐Fos inhibit and promote cell proliferation, respectively. Mutations in SCF (Fbxl10) do not inhibit cell proliferation. 37 F‐box proteins Pof1 and Pof3 may mediate Wee1 (tyrosine kinase) degradation to promote cell entry into mitosis. 38

Prolonged mitotic arrest triggers SCF (Fbxw7)‐mediated degradation of WDR5, promoting cell death and preventing mitotic slippage. In the absence of Fbxw7, high levels of WDR5 promote mitotic slippage, a condition reversed by WDR5 knockout. 39 Cyclin E, c‐Myc, and Aurora‐A accumulation drive cancer cell growth following Fbxw7 deletion. 40 In glioma, Fbxw7 down‐regulation disrupts cell cycle checkpoints, leading to mitotic defects and aneuploid cell production. 41

SCF (β‐TrCP) enhances cell proliferation and invasion of cervical cancer cells (HeLa), human colorectal cancer cells (HCT116) by mediating USP33 degradation. 42 Deficiency of β‐TrCP1 (subtype 1) results in nuclear accumulation of β‐catenin, reducing mouse embryonic fibroblast proliferation rates while increasing cell size and polyploidy. 43 FAS‐related factor 1 (FAF1) facilitates β‐catenin ubiquitination and degradation by bridging β‐catenin and β‐TrCP, enhancing SCF (β‐TrCP)‐mediated polbiquitination and degradation of β‐catenin. 44 SCF (cyclin F)‐mediated CP110 degradation ensures mitotic fidelity and genomic integrity. 45 Cyclin F down‐regulation in the a‐375 melanoma cell line increases cell viability, promotes epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT), and enhances proliferation. 46 Similarly, ectopic expression of Fbxo2 promotes osteosarcoma (OS) cell proliferation and colony formation. 47 SCF (Slimb/β‐TrCP) and APC/CFZR‐1 synergistically maintain ZYG‐1 activity threshold in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos, ensuring a normal number of centrosomes (Figure 5A). 48

FIGURE 5.

SCF regulation of cell proliferation and migration. (A) After SCF (β‐TrCP) ubiquitinates and degrades Emil1, APC activity increases to promote cell proliferation. Fbxl10 inhibits cell proliferation by suppressing ribosomal RNA expression. Pof1 and Pof3 co‐downregulate Wee1 to increase the rate of cell mitosis entry. Phosphorylation of c‐Fos by EGF antagonizes c‐Fos ubiquitination and promotes cell proliferation. Pseudophosphorylation mutation of c‐Fos S374 stabilizes c‐Fos, promoting cell proliferation, while dephosphorylation mutation destabilizes c‐Fos, hindering cell proliferation. SCF (Fbxl10) mutation loses the ability to inhibit cell proliferation. By mediating USP33 degradation, SCF (β‐TrCP) relieves USP33 inhibition on cell proliferation and promotes proliferation. FAF1 promotes SCF (β‐TrCP) to down‐regulate β‐catenin, preventing β‐catenin from inhibiting cell proliferation. SCF (cyclin F) mediates CP110 degradation to ensure DNA replication correctness and integrity during mitosis. Translocation expression of Fbxo2 promotes osteosarcoma cell proliferation. (B) The degradation of Twist by SCF (β‐TrCP) inhibits the motility and migration of cancer cells. Overexpression of Fbxl13 leads to the ubiquitination and degradation of CEP192 and γ‐tubulin, disrupting the nucleation of centrosome microtubule arrays and promoting cell migration. Ubiquitination and degradation of Rac1 by Fbxl19 reduces the formation of cell migration fronts and inhibits cell migration. S71A‐Rac1 and K166R‐Rac1 mutants resist Fbxl19 degradation and promote cell migration. Fbxw17 promotes cell migration by degrading Fbxl19 and reducing Rac ubiquitination, while acetylation of Fbxl19 resists Fbxw17‐mediated degradation.

Twist, a substrate of SCF (β‐TrCP), is a key inducer of epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT). Twist accumulation enhances cervical cancer cells (HeLa) motility and metastasis post‐β‐TrCP deletion. 49 FBXL7 mediates ubiquitination and proteasome degradation of active c‐SRC after phosphorylation at Ser104 site. But in pancreatic cancer and high stage prostate adenocarcinomas, FBXL7 is silenced by promoter hypermethylation. Defects in the FBXL7‐mediated degradation of c‐SRC increase cell migration, invasion, and the expression of EMT markers. 50 Overexpression of Fbxl13 down‐regulates CEP192 and γ‐tubulin, disrupting nucleation of centrosome microtubule arrays and promoting human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T) movement and migration. Conversely, CEP192 and γ‐tubulin enrichment weakens human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T) motility. 51 SCF mediates ubiquitination and degradation of Rac1, inhibiting tumor cell migration by suppressing lamellipodia formation. 52 Fbxl19 down‐regulates Rac1, significantly reducing rat lung epithelial cells (MLE12) migration and migration front formation, while Mutants S71A‐Rac1 and K166R‐Rac1 resist degradation. In Lys (166)‐Rac1 mutant cells, ectopic expression of Fbxl19 does not inhibit the cell migration caused by the overexpression of Rac1. 53 Exogenous Fbxw17 stabilizes Rac1 by targeting Fbxl19 for ubiquitination and degradation, promoting cell migration. Acetylation of Fbxl19 mitigates degradation (Figure 5B). 54 Activated Nrf2 promotes lung cancer metastasis by inhibiting the Fbxo22‐dependent degradation of Bach1. 55

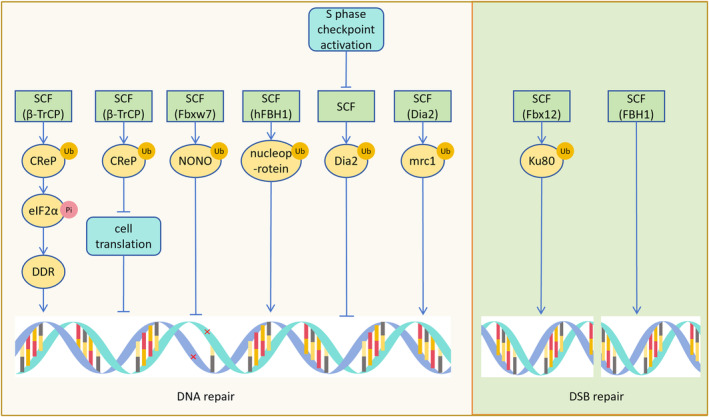

6. SCF IN REGULATION OF DNA REPAIR

Following DNA damage, β‐TrCP targets the degradation of CReP, inducing eIF2α phosphorylation and promoting the expression of DNA repair proteins. CReP down‐regulation contributes to translation mechanism inactivation after DNA damage, reducing translation levels during DNA repair and facilitating the repair process. 56 DNA damage‐induced down‐regulation of cyclin F by ATR leads to accumulation of its substrate RRM2, which catalyzes ribonucleotide conversion into deoxyribonucleotides (dNTPs), thereby promoting DNA replication and repair. 57 NONO, a substrate of Fbxw7, is an RNA‐binding protein involved in DNA repair, mRNA splicing, and checkpoint activation. 58 The SCF (hFBH1) complex possesses ATPase, helicase, and ubiquitinase activities. It ubiquitinates proteins interacting with DNA, facilitating subsequent DNA processes. 59 Cell cycle progression is regulated by pathways for immune examination, activation of the S‐phase checkpoint pathway stabilizes the Dia2 protein, aiding the replication complex in overcoming damaged DNA and natural fragile regions, thus maintaining genomic stability. 60 Moreover, Dia2 mediates Mrc1 degradation in checkpoint‐deficient cells, facilitating cell cycle recovery following S‐phase DNA damage induced by replication stress. 61 EMI1 has a F‐box domain. Which can form SCF (EMI1) complex to target the ubiquitination and degradation of RAD51. CHK1‐mediated phosphorylation of RAD51s EMI1‐dependent degradation by enhancing RAD51's affinity for BRCA2, leading to RAD51 accumulation. Stabilizing RAD51 will help homologous recombination repair and maintain genomic stability. 62

The Ku70 / Ku80 heterodimer is a core component of the non‐homologous end‐joining (NHEJ) pathway for double‐strand break (DSB) repair. During DNA double‐strand break (DSB) repair in Xenopus cells, DNA recruits Fbxl12 to remove Ku80, relieving inhibition of DNA end homologous recombination by the Ku70/80 complex. 63 Removal of Ku80 does not facilitate the completion of non‐homologous end‐joining (NHEJ). 64 The F‐box protein FBH1, housing a DNA helicase domain, collaborates with Skp1 to repair DSBs generated by Rec12, prevent spindle bending, and ensure proper chromosome separation (Figure 6). 65

FIGURE 6.

SCF affects DNA repair. SCF (β‐TrCP) promotes the phosphorylation of eIF2α after degrading CReP, leading to the expression of DNA repair proteins such as DDR and promoting DNA repair. Degradation of CReP by SCF (β‐TrCP) can also decrease cell expression during DNA repair, aiding DNA repair. The substrate NONO of SCF (Fbxw7) assists in the DNA repair process. SCF (hFBH1) degrades DNA binding proteins like nucleoprotein, facilitating the binding of DNA to repair proteins. Activation of the S‐phase checkpoint reduces Dia2 degradation, assisting in DNA repair at damaged sites. SCF (Dia2) degrades mrc1, aiding in the repair of S‐phase DNA damage. SCF (Fbx12) degrades Ku80, relieving Ku80's inhibition on DNA double‐strand break (DSB) repair, and promoting DSB repair. SCF (FBH1) repairs DSBs produced by Rec12.

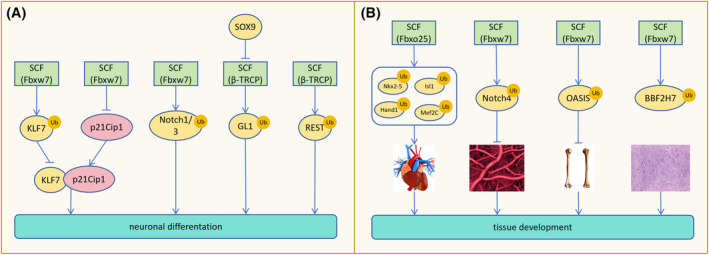

7. SCF IN STEM CELL MAINTENANCE, CELL DIFFERENTIATION, AND TISSUE DEVELOPMENT

Fbxw7 serves as a crucial regulator of brain stem cell viability and differentiation, primarily through its modulation of krüppel‐like factor 7 (KLF7) and Notch (Notch1 and Notch3). Overexpression of Fbxw7 reduces KLF7 levels and inhibits p21Cip1 gene expression, impairing neuronal differentiation and maintenance by disrupting their interaction. 66 Conversely, in Fbxw7‐deficient mice, the accumulation of Notch1 and Notch3, along with up‐regulation of Notch target genes, sustains neural stem cell characteristics. Loss of Fbxw7 causes abnormal Notch signaling leading to altered differentiation of neural stem cells in mice, with a tendency for neural stem cells to differentiate into astrocytes rather than neurons in vitro. Inhibition of the Notch signaling pathway reverses this differentiation trend. 67 SCF (Fbxw7) also targets ubiquitination to degrade SOX9 in neuroblastoma, influencing neural tube‐forming tumor cells plasticity. 68 SOX9 inhibits β‐TrCP‐mediated GLI1 protein degradation, promoting nuclear GLI1 expression and cancer stem cell characteristics. 69 SCF (β‐TrCP) facilitates proper neural differentiation by degrading REST, while abnormal accumulation of REST compromises differentiation (Figure 7A). 70 Moreover, SCF (β‐TrCP)‐mediated degradation of REST starts in G2, and this event requires the DEGXXS degron in the REST C terminus. 71

FIGURE 7.

SCF involves in maintaining stem cell properties, affecting cell differentiation, and tissue development. (A) SCF (Fbxw7) overexpression degrades KLF7, inhibiting p21Cip1 gene expression and impairing neuronal differentiation by reducing the interaction between KLF7 and p21Cip1. SCF (Fbxw7)‐mediated degradation of Notch1/3 is necessary for neuronal differentiation. SOX9 prevents SCF (β‐TRCP)‐mediated degradation of GL1, maintaining the stem cell properties of cancer cells. Normal degradation of REST by SCF (β‐TRCP) promotes normal neuronal differentiation. (B) SCF (Fbxo25) degrades Nkx2‐5, Isl1, Hand1, and Mef2C to assist in heart development. SCF (Fbxw7)‐mediated degradation of Notch4 is required for vascular network development. Degradation of OASIS and BBF2H7 by SCF (Fbxw7) inhibits bone and cartilage formation, while depletion of Fbxw7 promotes bone and cartilage development facilitated by OASIS and BBF2H7.

Fbxo25 promotes Nkx2‐5, Isl1, Hand1, and Mef2C degradation, regulating cardiac protein homeostasis and cardiac development during cardiomyocyte development in embryonic stem cells (ESCs). 72 During mammalian embryonic development, Fbxw7 deletion leads to increased Notch4 accumulation and Hey1 expression, impeding vascular network formation. Hence, Fbxw7 is indispensable for vascular development. 73 Additionally, Fbxw7 governs bone and cartilage formation by targeting the degradation of OASIS and BBF2H7, respectively. 74 Under conditions of low tryptophan, SCF mediates TDO polyubiquitination and degradation, preventing excessive tryptophan degradation and aiding in maintaining nerve and immune homeostasis (Figure 7B). 75

8. SCF COMPLEX EFFECTS ON OXIDATIVE STRESS, APOPTOSIS, AND AUTOPHAGY

8.1. Oxidative stress

Fbxl17 modulates the transcription of NRF2 target HMOX1, regulating the NRF2‐dependent gene activation threshold through transcriptional repressor BACH1, irrespective of external oxidative stress. 76 Neurons deficient in Fbxw7β are vulnerable to oxidative stress, whereas Fbxw7β overexpression confers resistance to oxidative stress without altering endoplasmic reticulum stress or sensitivity to other apoptosis inducers. 77

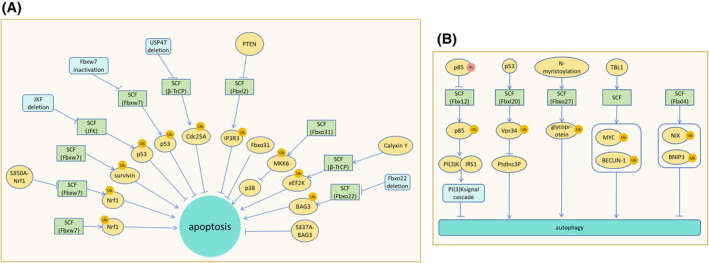

8.2. Apoptosis

Several F‐box proteins have apoptosis‐promoting effects and can be considered as apoptotic factors, such as Fbxw7(Cdc4) and Fbxl7. GSK3‐mediated phosphorylation of the Cdc4 phosphorylation domain (CPD) of Nrf1 leads to Fbxw7‐mediated Nrf1 degradation, promoting neuronal apoptosis under endoplasmic reticulum stress. 78 Interaction between Fbxl7 and Glu(126) in the carboxyl terminal α helix of survivin facilitates survivin polyubiquitination and degradation, impairing mitochondrial structure and function and inducing apoptosis. 79

Some F‐box deletion or loss of function will promote apoptosis. JFK is the only F‐box protein containing the human Kelch domain. After JFK is knocked out, the stable substrate p53 blocks the cells in the G1 phase, which promotes apoptosis and makes the cells sensitive to ionizing radiation‐induced death. 80 Similarly, inactivation of Fbxw7 stabilizes p53, thereby arresting the cell cycle, leading to apoptosis and making cancer cells sensitive to radiation or etoposide. 81 USP47 can enhance the function of SCF (β‐TrCP). However, USP47 deficiency inhibits SCF (β‐TrCP) degradation of Cdc25A, promotes apoptosis, and enhances the cytotoxicity of anticancer drugs.

F‐box dysfunction will affect the survival of tumor cells. Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) inhibits Fbxl2 degradation of IP3R3 and promotes apoptosis. 82 Re‐expression of Fbxo25 in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) lacking Fbxo25 induces apoptosis, while the pro‐survival protein HCLS1‐associated protein X‐1 (HAX‐1) phosphorylation mutant resists apoptosis due to Fbxo25 re‐expression. 83 Fbxo31 is related to the anti‐apoptotic effect of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) cells under different genotoxic stress. 84 In addition, SCF (Fbxo31) mediates ubiquitination and degradation of MKK6, preventing MKK6 from activating p38 to induce apoptosis. 85 Calyxin Y (a unique chalcone diarylheptanoid adduct) enhances the apoptosis of HepG2 and HepG2/CDDP cells through the SCF (β‐TrCP)‐eEF2K pathway and synergistically enhances the cytotoxicity of cisplatin (CDDP). 86 Silencing Fbxw7α in multiple myeloma cells with constitutively non‐canonical NF‐κB activity can lead to cell apoptosis in cellular systems and xenograft models. 87 Fbxo11 gene deletion or mutation has been reported in several invasive diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cell lines. Re‐expression of Fbxo11 promotes substrate ubiquitination and degradation of BCL6 to induce lymphoma cells death. 88 For the degradation of BAG 3 by SCF (Fbxo22), the phosphorylation of BAG 3 by Ser (377) is required by ERK before the ubiquitination of BAG 3 by SCF (Fbxo22) is initiated. Fbxo22‐deficient or stable S377A‐BAG3 mutants would up‐regulate BAG 3 and promote tumor growth through apoptosis defects (Figure 8A). 89 Rsk1/2 mediates phosphorylation of BimEL, a potent proapoptotic BH3‐only protein, on Ser93/Ser94/Ser98. Activation of BimEL on Ser93/Ser94/Ser98 mediates binding to β‐TrCP and degradation via SCF (β‐TrCP). Degradation of BimEL enables tumor cells to escape chemotherapy‐induced apoptosis. 90

FIGURE 8.

Effects of SCF complex on oxidative stress, apoptosis, and autophagy. (A) Fbxw7 degrades Nrf1, promoting neuronal apoptosis during endoplasmic reticulum stress. The S350A‐Nrf1 mutant resists Fbxw7 degradation and apoptosis. SCF (Fbxl7) mediates the polyubiquitination and degradation of survivin, impairing mitochondrial function and promoting apoptosis. Deletion of JKF fails to degrade p53, resulting in cell cycle blockade and apoptosis induction. Inactivation of Fbxw7 halts the cell cycle and induces apoptosis. USP47 deletion inhibits SCF (β‐TrCP) ubiquitination and degradation of Cdc25A, leading to apoptosis. PTEN prevents Fbxl2 from degrading IP3R3, leading to apoptosis. Fbxo31 plays an anti‐apoptotic role in ESCC. SCF (Fbxo31) degrades MKK6, preventing activation of p38 and apoptosis. Calyxin Y promotes apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by enhancing SCF (β‐TrCP) degradation of eEF2K. Fbxo22 deletion fails to degrade BAG3, resulting in high levels of BAG3 and preventing apoptosis. The S337A‐BAG3 mutant, resistant to degradation, inhibits apoptosis. (B) Phosphorylated p85 resists SCF (Fbx12)‐mediated ubiquitination and degradation, hindering PI(3)K binding to IRS1 and inhibiting PI(3)K signaling cascades, ultimately promoting autophagy. P53 promotes SCF (Fbxl20) degradation of Vps34 and inhibits PtdIns3P‐induced autophagy. N‐myristoylation promotes SCF (Fbxo27) ubiquitination of glycoproteins, facilitating lysosomal autophagy. TBL1 promotes SCF‐mediated degradation of MYC and BECLIN‐1, promoting autophagy in damaged cells to stabilize them. SCF (Fbxl4) ubiquitination degrades NIX and BNIP3, inhibiting mitophagy.

Fbxo28 does not regulate the insulin‐secretory function of islet β cells, but its deletion causes apoptosis. Overexpression of Fbxo28 can make cells survive for a long time under high glucose and inflammatory cytokine (recombinant human IL‐1β, IFN‐γ) conditions. 91 In G2 phase, SCF(cyclin F) mediate SLBP degradation to inhibit apoptosis. 92 In Caenorhabditis elegans insulin‐like growth factor‐1 signaling (IIS) mutants, the SCF complex partially increases cell lifespan by promoting DAF‐16/FOXO transcriptional activity, and the underlying mechanism remains to be studied. 93

8.3. Autophagy

Fbxl2 does not recognize phosphorylated p85, which inhibits the binding of p110 subunit of PI(3)K to IRS1, attenuates PI(3)K signaling cascade, and promotes autophagy. 94 After DNA damage, activated p53 promotes SCF (Fbxl20) ubiquitination and degradation of vacuolar sorting protein 34 (Vps34), thereby inhibiting PtdIns3P‐mediated autophagy and receptor endocytosis. 95 N‐myristoylation of Fbxo27 rapidly accumulates around damaged lysosomes and ubiquitinates glycoproteins exposed to lysosomal damage to induce lysosomal autophagy. Preferential ubiquitination of lysosomal protein LAMP2 during lysosomal damage can promote the recruitment of damaged lysosomes. 96 TBL1 promotes SCF‐mediated degradation of MYC and BECLIN‐1 and promotes survival autophagy of damaged cells. 97 SCF (Fbxl4) mediates ubiquitination and degradation of mitochondrial phagocytic receptors NIX and BNIP3 to inhibit mitophagy in the extracellular membrane of non‐stressed cells (Figure 8B). 98 Fbxw5 targets SEC23B to inhibit autophagic. 99

9. SCF INVOLVES IN THE REGULATION OF IMMUNE RESPONSE

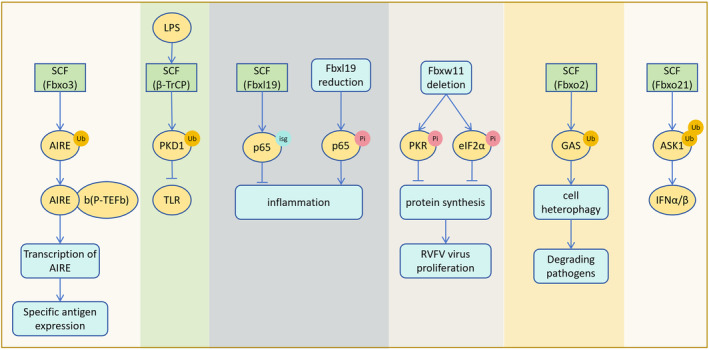

SCF can act as a positive/negative regulator of inflammatory pathways and also play a role in anti‐pathogen infection. SCF (Fbxo3) ubiquitinates AIRE and promotes the binding of positive transcription elongation factor b (P‐TEFb) to enhance AIRE transcriptional activity. This ensures the expression of AIRE‐reactive tissue‐specific antigens in the thymus. 100 Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) promotes SCF (β‐TrCP) to down‐regulate PKD1 and restore the level of NF‐κB inhibitor (I‐κBα), inhibiting TLR inflammatory signals. Knockdown of β‐TrCP can block the down‐regulation of PKD1, indicating that β‐TrCP is a negative regulator of the upstream signal of I‐κBα in the LPS signaling pathway. 101 LPS down‐regulates the protein levels of Sirt1 and p300, affects the binding of PRMT1 and SCF (Fbxl17), stabilizes the protein level of PRMT1, leading to excessive growth of bronchial epithelial cells in pulmonary inflammatory diseases. 102 SCF (Fbxl19) acts as an ISG15 E3 ligase that regulates endothelial cell inflammation. The post‐translational modification (ISGylation) of p65 can reduce the degree of pulmonary inflammation and experimental acute lung injury in humanized transgenic mice. 103

Fbxw11 deletion can partially stabilize the autophosphorylation of protein kinase R (PKR) and the phosphorylation of PKR substrate eIF2α, and block the protein synthesis of Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) host cells. Low levels of β‐TrCP1 can better protect PKR from the influence of viral non‐structural protein NSs. 104 , 105 Fbxo2 recognizes the GlcNAc side chain of GAS (group A streptococcus), promotes ubiquitin‐mediated GAS heterophagy to degrade bacterial pathogens and protect cells. 106 Fbxo21 mediates Lys(29)‐linked polyubiquitination and activation of apoptosis signal‐regulated kinase 1 (ASK1) during viral infection and promotes the production of interferon (IFNα/β) (Figure 9). 107

FIGURE 9.

SCF involves in the regulation of immune response. SCF (Fbxo3) ubiquitination of AIRE promotes AIRE binding to b (P‐TEFb) and increases AIRE expression, thereby facilitating the expression of specific antigens in the thymus. LPS promotes SCF (β‐TrCP) to degrade PKD1, inhibiting the TLR inflammatory signaling pathway. SCF (Fbxl19) targets ISGylation of p65 to reduce inflammation and inflammation‐induced damage in mice. Following Fbxl19 deletion, p65 phosphorylation increases, enhancing the inflammatory response. Fbxw11 deletion promotes the phosphorylation of PKR and eIF2α, leading to the shutdown of protein synthesis in RVFV‐infected cells and inhibition of viral proliferation. Fbxo2 ubiquitination of GAS promotes cell heterophagic degradation of bacterial pathogens. SCF (Fbxo21) mediates polyubiquitination of ASK1, promoting the production of interferon IFNα/β.

10. THE EFFECT OF UPSTREAM REGULATORY FACTORS OF SCF COMPLEX ON ITS FUNCTION

10.1. Targeting SCF complex components regulates its function

Brusatol (Bru) significantly inhibits the growth and metastasis of non‐small cell lung cancer by targeting Skp1, up‐regulating p27 and E‐cadherin. 108 EN884 promotes SCF‐mediated degradation of BRD4 and androgen receptors by targeting Skp1. 109 6‐O‐angeloylplenolin (6‐OAP) binds to Skp1 in Skp1‐Skp2, leading to the dissociation and degradation of Skp2 and down‐regulation of its substrate NIPA. It showed strong anti‐lung cancer ability. 110 , 111 The protein factor glomerular protein (Glmn) inhibits ligase activity by inserting between Cul1 and Rbx1 to prevent over‐ubiquitination. 112

The function of F‐box can be inhibited by blocking its ubiquitination ability or inhibiting F‐box gene expression. Drosophila Homeodomain‐interacting protein kinase (Hipk) can block the ubiquitination of β‐catenin by β‐TrCP, and vertebrate homolog Hipk2 has similar ability to block ubiquitination. 113 In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), microRNA‐770 inhibits the expression of Fbxw7 by targeting the 3 ‘‐untranslated region of Fbxw7 and promotes the activation of β‐catenin. 114 The F‐box domain of histone demethylase KDM2B binds to Fbxw7, reduces the degradation of c‐Jun subunit of AP‐1 and induces the expression of AP‐1 signaling pathway, thereby promoting cleaved KSHV infection. 115 SCF (Fbxo28) ubiquitinates and degrades Fbxo28 itself, regulates its own Fbxo28 expression, and may affect its cancer‐promoting effects. 116 Similarly, SCF (Fbwx7) and TRIP12 co‐mediated proteasome degradation of Fbwx7. 117 In addition, ERK phosphorylated Thr (205) of Fbwx7 to promote its down‐regulation. 118

Some proteins promote the function of SCF complex by directly binding to F‐box. Heat shock factor Hsf1 promotes the expression of αB crystallin, while αB crystallin combined with SCF (Fbx4) promotes the down‐regulation of cyclin D1 and p53, which helps cells resist carcinogenic transformation and DNA damage. Phosphorylation of αB crystallin Ser (19) and Ser (45) will promote its binding to Fbx4. 119 , 120 , 121 SLP‐1 binds to the n‐terminal domain of Fbxw7‐γ to promote SCF (Fbxw7‐γ) degradation of c‐Myc, while Fbxl16 antagonizes the down‐regulation of c‐Myc by Fbxw7. 122 , 123 USP7 may inhibit SCF ubiquitination of cyclin F and stabilize cyclin F by independent deubiquitinating enzyme activity. In addition, inhibition of USP7 deubiquitinase activity will down‐regulate cyclin F mRNA. 124

Inhibition of CSN‐related kinase activity or knockdown of CSN5 inhibits SCF(JFK) degradation of p53, enhances p53‐dependent transcription, and leads to cell growth inhibition, cell G1 phase arrest and apoptosis. 125 CDK1 and CDK2 phosphorylate Fbxo28, which is necessary for Fbxo28 effective ubiquitination and degradation of MYC. Fbxo28 deficiency or loss of function can suppresses MYC‐driven transcription, transformation, and tumorigenesis. 126

10.2. Phosphorylation of substrates of SCF complex regulates its function

10.2.1. Phosphorylation of substrates promotes the function of SCF

In cellular glucose metabolism, Snf1 kinase phosphorylates Pfk27 to promote SCF (Grr1) to down‐regulate Pfk27 and Tye7 to inhibit glycolysis. 127 SCF (Fbxw7) recognizes Sic1 in a multi‐site phosphorylation‐dependent manner. The interaction between Fbxw7 and Sic1 can be determined by both high‐affinity diphosphorylated CPD and several low‐affinity monophosphorylated CPD, and the interaction of low‐affinity sites may be related to the phosphorylation threshold. 128

During DNA damage checkpoint silencing, the β‐TrCP binding domain of eEF2K is autophosphorylated and degraded by SCF (β‐TrCP) to rapidly restore translation elongation. 129 Spironolactone promotes CDK7 phosphorylation of XPB Ser (90) and then promotes SCF (Fbxl18) ubiquitination and degradation of XPB. 130

At the beginning of mitosis, polo‐like kinase 1 (Plk1) and Cdc2 phosphorylate Wee1 at Ser (53) and Ser (123), respectively, promoting SCF (β‐TrCP)‐mediated Wee1 ubiquitination and degradation to ensure rapid activation of Cdc2 and cell entry into M phase. 131 In the metaphase of mitosis, PLK1 phosphorylates Ser (332) of Cep68, a centrosomal junction protein, and promotes SCF (β‐TrCP)‐mediated Cep68 down‐regulation. 132 During the transition from metaphase to anaphase, glycogen synthase kinase‐3β (GSK‐3β) phosphorylates PTTG1 (also known as securin) to promote SCF (β‐TrCP) down‐regulation of PTTG1, allowing the activation of segregating enzymes. 133 Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) may promote SCF‐mediated degradation of hsecurin by phosphorylating it, thus allowing sister chromatid separation. 134

Fbxo31‐mediated degradation of EMT transcription factor Snail1 requires Snail1 to phosphorylate. 135 GSK3 kinase phosphorylates Thr (236) of SOX9, prompting SCF (Fbxw7α) to recognize and down‐regulate SOX9. 136 In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, protein kinase CK2 phosphorylates Ser (223) of UBC3B and UBC3 and promotes SCF (β‐TrCP) down‐regulation of UBC3 B and UBC3. 137

10.2.2. Phosphorylated substrates inhibit the function of SCF

Nek7 phosphorylates Ser (114) of telomere repeat binding factor 1 (TRF1) to resist Fbx4 recognition to protect telomeres. 138 The C‐terminal phosphorylation of Sic1 can resist SCF (Fbxw7) and inhibit the process of G1‐S phase. 139 ATM phosphorylation of hSSB1 Thr (117) can block Fbxl5‐mediated ubiquitination and degradation. Overexpression of Fbxl5 abolished the cell response to DSB and increased the radio and chemical sensitivity of cells after genotoxic stress. 140

10.3. Microorganisms regulate host cell function by imitating F‐box proteins or affecting SCF function

Some microbial pathogens inject eukaryotic‐like F‐box effectors into host cells, ubiquitinating host cell‐specific targets to promote pathogen proliferation. Studies have found that the ubiquitination mechanism of the host is destroyed by the F‐box protein, which may be a common strategy in pathogenic bacteria. 141 The ANK (ankyrin repeat) repeats encoded by several chlorine viruses contain the cell F‐box feature domain or the related NCLDV chordopox PRANC (pox protein repeats of ankyrin at C‐terminal) domain, which can regulate the host's ubiquitination and proteasome degradation of the substrate. 142 The host's antibacterial activity rapidly degrades Agrobacterium's F‐box protein Vir F through the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway, which is counteracted by the bacterial effector protein VirD5. 143

Rotavirus infection down‐regulates β‐TrCP to inhibit SCF (β‐TrCP) ubiquitination and degradation of phosphorylated Ikappa Bα, thereby inhibiting nuclear factor‐activated B‐cell κ light chain enhancer, and finally escaping immunity by regulating non‐specific immune signals. 144 HIV‐1 viral protein U (Vpu) inhibits the typical and atypical NF‐κB pathways in the late life cycle of the virus by degrading β‐TrCP1 and binding β‐TrCP2, and promotes viral infection. 145 In addition to the S52A‐Vpu mutant, Vpu binds to β‐TrCP to prevent SCF (β‐TrCP)‐mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53. The accumulation of p53 protein in the late stage of HIV‐1 infection was positively correlated with T cell apoptosis. 146

In HCC infected with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV), viral protein HBx may block SCF recognition of pituitary tumor transforming gene 1 (PTTG1) to stabilize it. 147

11. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SCF AND THE OCCURRENCE, PROGNOSIS, AND TREATMENT OF DISEASE

11.1. SCF and the occurrence of disease

11.1.1. Cancer

Fbxo6 deficiency promotes the proliferation, migration, and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. 148 In addition, SCF (β‐TrCP)‐mediated ubiquitination and degradation of AEBP2 loss of function will make ovarian cancer patients resistant to cisplatin. 149

Down‐regulation of REST by overexpression of β‐TrCP will promote the carcinogenic transformation of human mammary epithelial cells. 70 Studies have found that GSK3 promotes ubiquitination of Fbxw7α and degradation of GATA3, inhibiting the survival of breast cancer cells. 150 SCF (JFK) targets the ubiquitination and degradation of inhibitor of growth 4 (ING4). The loss of control of ING4 will overactivate the typical NF‐κB pathway and promote angiogenesis and metastasis of breast cancer. 151 Overexpression of SCF (Fbxo44) can down‐regulate BRCA1 and promote the development of sporadic breast tumors. 152 The ectopic expression of FAF1 reduces the metastasis and invasion of breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. 44 Additionally, Cul1 significantly promoted the migration, invasion, and tube formation of breast cancer cells in vitro and angiogenesis and metastasis in vivo. 153

In pancreatic cancer, KRAS mutation promotes ERK phosphorylation of Thr (205) of Fbxw7 and promotes down‐regulation of Fbxw7. T205A‐Fbxw7 mutant resists ERK phosphorylation and can significantly inhibit the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. 118 SOX9 and GLI1 transcription factors promote the development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA). 69 Fbxl5 overexpression degrades hSSB1, inhibits DNA damage repair, and promotes tumor growth. 140 Fbxo31 overexpression inhibits EMT by down‐regulating Snail1, thereby inhibiting the colonization of gastric cancer cells in vivo. 135 Fxr1 inhibits the function of SCF (Fbxo4) by down‐regulating Fbxo4 mRNA, further overexpressing Fxr1 and enhancing the pro‐tumor activity of Fxr1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). 154 Fbxl6 ubiquitinates and stabilizes heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) AA1 to activate c‐MYC. Activated c‐MYC directly binds to the promoter region of Fbxl6 to promote its mRNA expression, which may contribute to the development of HCC. 155 Cyclin F can reduce the promoting effect of IDH1R132H on glioma by RBPJ. 156 Mitotic defects caused by Fbxw7 knockdown may promote the occurrence of aneuploidy in progressive gliomas. 41 Fbxw7 is down‐regulated in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and promotes tumor cell migration and invasion through EMT. 157

After Fbxw 7 was inhibited, Stable SOX9 promotes the migration, metastasis, and drug resistance of medulloblastoma. 136 In medulloblastoma of Gorlin syndrome patients, Fbxl17 degrades Sufu through polyubiquitination, which activates Hh signaling and promotes its cell growth. 158 After cisplatin treatment, the up‐regulation of cyclin F in RPMI‐7951 cells caused the cell cycle to be out of control and more sensitive to cisplatin. Therefore, cyclin F may regulate the drug response of melanoma. 159 Fbxo2 promotes the development of OS by activating the STAT3 signaling pathway. 47 In multiple myeloma, Fbxw7α and GSK3 promote cell survival by degrading p100. 87 In ESCC, overexpression of Cyclin D1 is considered to be a key driver, while Fbxo4 is an inhibitor. 160 Mutations and deletions of Fbxo11 promote the occurrence of DLBCL by stabilizing BCL6. 88 The high expression of Fbxw11 activates NF‐κB and β‐catenin/TCF signaling pathways to up‐regulate Cyclin D1 and promote the proliferation and disease development of L1210 lymphoblastic leukemia cells. 161 TRIP12 inactivation promotes Fbxw7 protein accumulation and proteasome degradation of SCF (Fbxw7) substrate myeloid leukemia 1 (MCL1), making cancer cells sensitive to tubulin chemotherapy. 117 Fbxw7 mutation (p. L443H (previously unreported) and p. R479P) can promote the proliferation, migration, and invasion of cervical cancer cells. 162

11.1.2. Non‐neoplastic diseases

CCNF (cyclin F gene) missense mutation may accumulate TDP‐43 by increasing the ATPase activity of VCP, leading to the occurrence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). 163 , 164 Hepatocyte‐specific overexpression of Fbxw5 aggravates liver metabolic disorders and activates the mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, leading to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). 165 The accumulation of α‐actin caused by knockout of Fbxl22 is associated with severe systolic dysfunction and cardiomyopathy. 166 The accumulation of Snail1 after β‐TrCP deletion will lead to defects in cell adhesion in seminiferous tubules, which will eventually lead to abnormal spermatogenesis. 167 The Fbxw11 expression increased significantly in amyloid‐β stimulated microglia. Fbxw11 May be a functionally important mediator of ASK1 activation and contribute to the development of Alzheimer's disease. 168 The R465C‐Fbxw7 mutation can cause lung developmental defects in mice and lead to perinatal death, occasionally leading to the eye‐opening phenotype and cleft palate at birth. In addition, mice carrying the liver‐specific R468C‐Fbxw7 allele and carcinogenic Kras mutation showed cholangiocarcinoma‐like lesions within 8 weeks of birth and bile duct hyperplasia within 8 months. 169 The absence of Fbxo7 in myelin glia leads to axonal degeneration and axonal peripheral neuropathy in the central nervous system, leading to motor disorders 170 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

The relationship between SCF complex and disease occurrence and treatment.

| Disease name | Relationship between SCF complex and diseases | Mechanism | Potential therapeutic targets | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian cancer |

Tumor progression Drug resistance |

The inability of SCF (β‐TrCP) to degrade AEBP2 will lead to cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer patients; the deletion of Fbxo6 promoted the proliferation, migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells | Cyclin F/KIF20A; Fbxo6 | [148, 149, 171] |

| Breast cancer |

Tumor progression Tumor metastasis |

Overexpression of β‐TrCP promotes REST degradation and leads to carcinogenic transformation of human breast epithelial cells; FBXW7α inhibits the survival of breast cancer cells by degrading GATA3; SCF (JKF)‐mediated ING4 instability leads to excessive activation of typical NF‐κB pathways and promotes angiogenesis and metastasis of breast cancer; Overexpression of SCF (Fbxo44) reduces BRCA1 protein levels and contributes to the development of sporadic breast tumors; fAF1 promotes SCF (β‐Tcrp) to degrade β‐catenin and inhibits cell metastasis and invasion; the deletion of Fbxo28 or the inability to ubiquitinate the expression of MYC mutants will lead to the inhibition of MYC‐driven transcription, transformation and tumorigenesis; CUL1 significantly promotes the migration, invasion, tube formation of breast cancer cells in vitro and angiogenesis and metastasis in vivo | CDK‐Fbxo28‐MYC axis | [44, 70, 126, 150, 151, 152, 153] |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | Tumor progression | The phosphorylation‐deficient T205A‐Fbxw7 mutant is resistant to ERK activation and can significantly inhibit the proliferation and tumorigenesis of pancreatic cancer cells; SOX9 and GLI1 transcription factors play an oncogenic role in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) | [69, 118] | |

| Lung cancer | Tumor progression | Overexpression of Fbxl5 down‐regulates hSSB1, inhibits DNA damage repair, and promotes tumor growth | Fbxl5 | [140] |

| Gastric cancer | Tumor metastasis | Fbxo31 inhibits Snail1 to reduce the occurrence of EMT, thereby inhibiting the colonization of gastric cancer cells in vivo | [135] | |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Tumor progression | Fxr1 inhibits the degradation function of SCF (Fbxo4) and promotes the cell activity of HNSCC | [154] | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Tumor progression | Fbxl6 ubiquitinated 90 (HSP90) AA1 to stabilize it and promote the stability and activation of c‐MYC. c‐MYC induced Fbxl6 mRNA expression. It contributes to HCC development | Fbxl6 | [155] |

| Renal cell carcinoma | Tumor metastasis | Fbxw7 is down‐regulated in RCC and promotes tumor cell migration and invasion through EMT | [156] | |

| Glioma |

Tumor progression Tumor metastasis |

With the increase of glioma grade, the level of IDH1R132H increased and the level of cyclin F decreased, and IDH1R132H mediated tumorigenesis and metastasis; knockdown of Fbxw7 leads to mitotic defects, which may promote aneuploidy in progressive gliomas | Fbxw7 | [41, 157] |

| Medulloblastoma |

Drug resistance Tumor progression Tumor metastasis |

Mutation or down‐regulation of Fbxw7 in medulloblastoma will not degrade SOX9, leading to cell migration, metastasis and drug resistance; Sufu mutation in Gorlin syndrome promotes Fbxl17 degradation of Sufu, leading to sustained Hh signal activation and promoting cell proliferation | SOX9 | [136, 158] |

| Melanoma | Drug resistance | After cisplatin treatment, the expression of cyclin F in RPMI‐7951 cells increased and showed greater susceptibility to cisplatin | [159] | |

| Osteosarcoma | Tumor progression | The increased expression of Fbxo2 in OS promotes the development of OS by activating the STAT3 signaling pathway | Fbxo2 | [47] |

| Myeloma | Tumor progression | Fbxw7α and GSK3 promote cancer cell survival by degrading p100 | [87] | |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma |

Tumor progression Tumor metastasis |

Overexpression of Cyclin D1 is considered to be a key driver of ESCC, but Fbxo4 is an inhibitor of esophageal tumorigenesis; Knockdown of Fbxo31 reduces the tumorigenicity of cancer cells, and silencing Fbxo31 makes cells and tumors sensitive to cisplatin treatment | Fbxo31 | [84, 160] |

| Lymphoma | Tumor progression | The mutation or deletion of Fbxo11 promotes the occurrence of lymphoma by stabilizing the level of BCL6; TBL1 inhibits SCF degradation of PLK1 and MYC, and inhibition of TBL1 can promote DLBCL cell death | TBL1 | [88, 97] |

| Leukemia |

Tumor progression Drug resistance |

The high expression of Fbxw11 activated NF‐κB and β‐catenin / TCF signaling pathways, promoted the expression of cyclin D1, promoted the proliferation of L1210 lymphoblastic leukemia cells, and finally promoted the occurrence and development of leukemia; TRIP12 inactivation leads to increased Fbwx7 protein accumulation and proteasome degradation of MCL1, making cancer cells sensitive to tubulin chemotherapy | Fbxw11 | [117, 161] |

| Cervical cancer |

Tumor progression Tumor metastasis |

Fbxw7 mutation promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells | [162] | |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | disease progression | The missense mutation of CCNF may promote the aggregation of TDP‐43 by increasing the ATPase activity of VCP in the cytoplasm, thus leading to the pathogenesis of ALS | [163] | |

| Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | Disease progression | Overexpression of Fbxw5 exacerbates diet‐induced systemic and liver metabolic disorders, as well as the activation of ASK1‐related MAPK signaling pathways in the liver, leading to the pathogenesis of ALS | Fbxw5 | [165] |

| Cardiomyopathy | Disease progression | Targeted knockout of Fbxl22 leads to the accumulation of α‐Actin, which is associated with severe systolic dysfunction and cardiomyopathy in vivo | [166] | |

| Spermatogenic failure | Disease progression | After the deletion of β‐TrCP, the accumulation of substrate Snail1 will lead to the defect of cell adhesion in seminiferous tubules, which will eventually lead to abnormal spermatogenesis | Snail1 | [22] |

| Alzheimer | Disease progression | Fbxw11 deficiency reduces neuroinflammation and amyloid‐β plaque formation by inhibiting ASK1 signaling pathway, thereby reducing alzheime | [168] | |

| Diabetes | Disease treatment | Fbxo28 promotes the survival of pancreatic β cells in a diabetic environment without affecting insulin secretion; the reduction of Fbxo2 can alleviate the diabetic phenotype of obese mice and reduce glucose intolerance and insulin resistance | Fbxo28; Fbxo2 | [91, 172] |

| HIV | Disease progression | The G allele is associated with low expression of Fbxo10. Fbxo10 targets Bcl‐2 protein degradation, and higher levels of Bcl‐2 can reduce HIV replication and infectivity | G allele | [173] |

| Palatoschisis | Disease progression | The R465C‐Fbxw7 mutant gene may lead to eye‐opening phenotype and cleft palate in mice at birth | [169] | |

| Bile duct hyperplasia and cancer‐like lesions | Disease progression | Mice carrying the liver‐specific R468C‐Fbxw7 allele and carcinogenic Kras mutation showed bile duct hyperplasia within 8 months of birth and cholangiocarcinoma‐like lesions within 8 weeks of birth | [169] | |

| Dyskinesia | Disease progression | The absence of Fbxo7 leads to axonal degeneration and axonal peripheral neuropathy in the central nervous system, leading to movement disorders | [170] |

11.2. The relationship between protein expression changes and disease prognosis

In breast cancer tissues, the expression of Fbx6 and β‐TrCP is increased. 17 , 70 High expression and phosphorylation of Fbxo28 serve as poor prognostic indicators for breast cancer. 126 The up‐regulation of JFK in breast cancer correlates positively with invasive clinical behavior. 151 Overexpression of Fbxo2 leads to hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance, 172 and it is significantly up‐regulated in osteosarcoma (OS). 47 Fbxl6 expression is significantly increased in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). 155 Decreased expression of cyclin F in HCC correlates with tumor size, clinical stage, serum alpha‐fetoprotein level, tumor diversity, and negatively correlates with tumor differentiation. Low cyclin F expression is an independent poor prognostic marker for overall survival in HCC patients. 174 Low expression of Fbx8 is an important factor in the overall survival of patients with colorectal cancer, 175 and the absence of Fbx8 accelerates chemo‐induced colon cancer. 176 High expression of Fbxo31 is associated with a poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) cancer. 84

The shortening of the half‐life of SCF (Fbxo3) substrate aromatic receptor interacting protein (AIP) is positively correlated with the occurrence and development of pituitary tumors. 177 Fbxw7 expression serves as an independent predictor of overall survival in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients, 157 and mutation or down‐regulation of Fbxw7 in medulloblastoma significantly increases SOX9 levels. 136 With the increase of glioma grade, the increase of IDH1R132H is associated with the decrease of cyclin F. 156 Fbxw7 is a prognostic indicator in patients with glioblastoma, and down‐regulation of Fbxw7 is positively correlated with decreased survival rate. 41 High expression of Fbxo6 is associated with poor overall survival (OS) in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. 148 Increased expression of FOXM1 and overexpression of Cyclin F and KIF20A are associated with poor prognosis of ovarian cancer. 171 Increased expression of Fbxl5 in lung cancer is associated with poor prognosis 140 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

The relationship between the expression of F‐box protein and the development and prognosis of disease.

| Disease name | Protein expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Overexpression of β‐TrCP and Fbx6; The high expression and phosphorylation of Fbxo28 are poor prognostic indicators of breast cancer and are associated with poor prognosis; The increased expression of JFK was positively correlated with invasiveness | [17, 70, 126, 151] |

| Diabetes | Overexpression of Fbxo2 leads to hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance and insulin resistance | [172] |

| Osteosarcoma | The expression of Fbxo2 was significantly increased | [47] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | The expression of Fbxl6 was increased; the decrease of cyclin F expression was correlated with tumor size, clinical stage, serum alpha‐fetoprotein level and tumor diversity, and negatively correlated with tumor differentiation. Low cyclin F expression is an independent poor prognostic marker for overall survival | [155, 174] |

| Colorectal cancer | The low expression of Fbx8 is an important factor in the overall survival of patients with colorectal cancer; The absence of Fbx8 accelerates the development of chemically induced colon cancer | [175, 176] |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | High expression of Fbxo31 is associated with poor prognosis | [84] |

|

Pituitary tumor |

The shortening of the half‐life of SCF (Fbxo3) substrate AIP is positively correlated with the occurrence and development of pituitary tumors | [177] |

| Renal cell carcinoma | The decrease of Fbxw7 expression is associated with stage and metastasis, and is an independent factor in predicting overall survival | [156] |

| Medulloblastoma | Down‐regulation of Fbxw7 expression is associated with poor prognosis | [136] |

| Glioma | The expression level of cyclin F decreased with the increase of glioma grade; The decrease of Fbxw7 is positively correlated with the decrease of survival rate, and Fbxw7 is a prognostic indicator for patients with glioblastoma | [41, 157] |

| Ovarian cancer | FOXM1, Cyclin F and KIF20 A are generally overexpressed, which is associated with poor prognosis; Increased expression of Fbxo6 is associated with poor prognosis | [148, 171] |

| Lung cancer | Increased expression of Fbxl5 is associated with poor prognosis | [140] |

11.3. The relationship between SCF and potential therapeutic targets of diseases

Cyclin F and KIF20A emerge as potential targets for treating ovarian cancer. 171 Fbxo2 may offer a novel therapeutic target for managing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), related metabolic diseases, and osteosarcoma (OS). 47 , 172 Fbxl5 presents a promising therapeutic target for lung cancer treatment. 140 Developing analogues of Fbxw5 (S1) or Fbxw5 (S3) could be a viable approach for treating nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. 165 Inhibiting Fbxo6 might be an effective strategy for ovarian cancer treatment, 148 and inhibiting Fbxl6 could be a promising therapeutic strategy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). 155 Inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activity with drugs disrupts SOX9 stability in a GSK3/Fbxw7‐dependent manner, rendering medulloblastoma cells sensitive to cell inhibition therapy. 136 Interfering with Fbxw7 or its downstream targets could open up new therapeutic avenues for glioblastoma treatment. 41 Investigating the relationship between the G allele and Fbxo10 expression offers new insights into reducing HIV risk. 173 Fbxw11 may serve as a potential molecular target for treating lymphocytic leukemia. 161 Restoring Fbxo28 expression may represent a novel therapeutic approach for promoting β‐cell survival in diabetes. 91 The CDK‐Fbxo28‐MYC axis stands out as a potential therapeutic pathway for MYC‐driven cancers, including breast cancer. 126 Silencing Fbxo31 could sensitize esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) cells and tumors to cisplatin treatment. 84 Combining calyxin Y and cisplatin (CDDP) might be an appealing therapeutic strategy for treating chemosensitive and chemoresistant liver cancer cells. 86 Targeted inhibition of TBL1 has the potential to induce diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cell death in vitro and in vivo. 97

There have been some studies on the development of small molecule inhibitors of the specific carcinogenic form of F‐box protein as anticancer therapeutic agents. Genistein can stop oncogenic progression in Pancreatic cancer (PC) by Fbxw7 up‐regulation and inhibiting the targeted site of Fbxw7, i.e., miR‐223 expression to induces apoptosis and block cell growth in PC cells. 178 Erioflorin holds anti‐tumorigenic potential as it selectively stabilizes a number of β‐TrCP target and inhibits AP‐1 and NF‐κB transcriptional activity, and interferes with cell cycle progression and proliferation of tumor cells. 179 Imatinib, the inhibitors targeting Fbxw7, is highly effective in tumor killing in chronic myelogenous leukemia, however, the drug fails to kill the cancer‐initiating cells frequently quiescent in the bone marrow. 180

Proteolysis‐targeting chimeras (PROTACs) show promise in tumor treatment. A representative compound, BWA‐522, effectively induces degradation of both AR‐FL and AR‐V7 and is more potent than the corresponding antagonist against prostate cancer (PC) cells in vitro. 181 ARV‐825 was identified as an agent that can selectively kill senescent liver cancer cells. 182 By employing a tumor‐specific mRNA‐responsive translation strategy, ClickRNA‐PROTAC system can selectively degrade protein of interest in tumor cells. ClickRNA‐PROTAC demonstrated strong efficacy in targeted cancer therapy in a xenograft mouse model of adrenocortical carcinoma (Table 3). 183

TABLE 3.

The known substrates of major F‐box proteins.

| Subfamily of F‐box proteins | Members | Substrates | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fbxl | Fbxl1 | p27; p21 | [19, 20] |

| Fbxl2 | IP3R3; p85 | [82, 94] | |

| Fbxl3 | Cryptochrome | [30, 31, 32] | |

| Fbxl4 | NIX and BNIP3 | [98] | |

| Fbxl5 | hSSB1 | [140] | |

| Fbxl6 | HSP90 | [155] | |

| Fbxl7 | c‐SRC; survivin | [50, 79] | |

| Fbxl10 | c‐Fos | [37] | |

| Fbxl12 | Ku80 | [63] | |

| Fbxl13 | CEP192 | [51] | |

| Fbxl17 | BACH1; PRMT1; Sufu | [76, 102, 158] | |

| Fbxl18 | XPB | [129] | |

| Fbxl19 | Rac1 | [53] | |

| Fbxl20 | Vps34 | [95] | |

| Fbxl22 | α‐Actin | [166] | |

| Others a | |||

| Fbxw | β‐TrCP(Fbxw1) | Mis18β; Cdc25; Cdc25B; Per1; Emi1; USP33; FAF1; Twist; CReP; REST; PKD1; eEF2K; Wee1; Cep68; PTTG1; p53; AEBP2; Snail1 | [11, 23, 29, 33, 34, 42, 44, 49, 51, 56, 70, 71, 129, 131, 132, 133, 146, 149, 167] |

| Fbxw5 | SEC23B | [99] | |

| Fbxw7 | Cyclin E; WDR5; NONO; KLF7; Notch; SOX9; OASIS and BBF2H7; Nrf1; p53; BimEL; AP‐1; Fbwx7; c‐Myc; Sic1; GATA3; p100 | [6, 39, 58, 66, 67, 68, 74, 78, 80, 87, 90, 115, 117, 122, 128, 136, 150] | |

| Fbxw11 | PKR | [104, 105] | |

| Others a | |||

|

Fbxo |

Fbxo2 | GAS | [106] |

| Fbxo3 | AIRE | [100] | |

| Fbx4‐alphaB crystallin | Cyclin D1 | [12] | |

| Fbx4 | Cyclin D1; p53; TRF1 | [22, 121, 138, 160] | |

| Fbx6 | Chk1 | [17] | |

| Fbxo11 | CDT2; BCL6 | [16, 88] | |

| Fbxo22 | BAG3; BACH1 | [55, 89] | |

| Fbxo25 | Nkx2‐5, Isl1, Hand1, and Mef2C | [72] | |

| Fbxo28 | Fbxo28; MYC | [116, 126] | |

| Fbxo31 | MKK6; Snail1 | [85, 135] | |

| Fbxo44 | BRCA1 | [152] | |

| Cyclin F | Cdh1; E2F1; CP110; RRM2; SLBP | [18, 26, 27, 45, 57, 92] | |

| Others a |

Others represent F‐box proteins in the subfamily that have not been discovered or whose functions are unclear.

12. PROBLEMS AND EXPECTATIONS

As research on SCF complexes expands, their involvement in various cellular processes such as cell cycle progression, DNA replication, oxidative stress response, apoptosis, cell differentiation, stem cell maintenance, tissue development, immune regulation, and cancer becomes increasingly evident. However, the vast family of F‐box proteins still harbors many mysteries, with numerous members' functions yet to be elucidated. Additionally, several popular F‐box proteins hold promise for further investigation into their potential mechanisms.

For instance, understanding how F‐box proteins Pof1 and Pof3 facilitate the degradation of Wee1 to promote cell mitosis, as well as the role of Dia2 protein in DNA repair and overcoming fragile sites, remains a priority for future research. Phosphorylation plays a crucial role in regulating SCF function, and comprehending the intricate dynamics of phosphorylation, particularly the role of low‐affinity sites, may shed light on general mechanisms governing phosphorylation thresholds in biological processes.

Given the association between aberrant SCF expression and the onset and progression of various diseases, the development of specific inhibitors holds significant promise for therapeutic interventions. These inhibitors could potentially target SCF complexes to mitigate disease pathology, offering a broad spectrum of therapeutic opportunities for diverse ailments. Overall, ongoing research efforts aimed at unraveling the complexities of SCF complexes and F‐box proteins hold immense potential for advancing our understanding of cellular biology and disease mechanisms, ultimately paving the way for innovative therapeutic strategies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

XZ wrote the manuscript and drew the figures. JC, JX, ZZ and CL collected the related papers and helped to revise the manuscript. JT and YZ designed and revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the review.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The present study was supported by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2022JJ70032, 2021JJ30915).

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All authors approved the final manuscript and the submission to this journal.

Supporting information

Data S1.

Data S2.

Data S3.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

Zeng X, Cao J, Xu J, et al. SKP1‐CUL1‐F‐box: Key molecular targets affecting disease progression. The FASEB Journal. 2025;39:e70326. doi: 10.1096/fj.202402816RR

Contributor Information

Yanhong Zhou, Email: zhouyanhong@csu.edu.cn.

Jingqiong Tang, Email: tangjingqiong423@csu.edu.cn.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable.

REFERENCES

- 1. Horn‐Ghetko D, Krist DT, Prabu JR, et al. Ubiquitin ligation to F‐box protein targets by SCF‐RBR E3‐E3 super‐assembly. Nature. 2021;590(7847):671‐676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gazdoiu S, Yamoah K, Wu K, et al. Proximity‐induced activation of human Cdc34 through heterologous dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(42):15053‐15058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sadowski M, Suryadinata R, Lai X, Heierhorst J, Sarcevic B. Molecular basis for lysine specificity in the yeast ubiquitin‐conjugating enzyme Cdc34. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(10):2316‐2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bloom J, Peschiaroli A, DeMartino G, Pagano M. Modification of Cul1 regulates its association with proteasomal subunits. Cell Div. 2006;1:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chandra Dantu S, Nathubhai Kachariya N, Kumar A. Molecular dynamics simulations elucidate the mode of protein recognition by Skp1 and the F‐box domain in the SCF complex. Proteins. 2016;84(1):159‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang W, Koepp DM. Fbw7 isoform interaction contributes to cyclin E proteolysis. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4(12):935‐943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baek K, Scott DC, Henneberg LT, King MT, Mann M, Schulman BA. Systemwide disassembly and assembly of SCF ubiquitin ligase complexes. Cell. 2023;186(9):1895‐1911.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu GP, Zhang ZL, Xiao S, et al. Rig‐G negatively regulates SCF‐E3 ligase activities by disrupting the assembly of COP9 signalosome complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;432(3):425‐430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morimoto M, Nishida T, Nagayama Y, Yasuda H. Nedd8‐modification of Cul1 is promoted by Roc1 as a Nedd8‐E3 ligase and regulates its stability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301(2):392‐398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Santos DN, Aguiar PHN, Lobo FP, et al. Schistosoma mansoni: heterologous complementation of a yeast null mutant by SmRbx, a protein similar to a RING box protein involved in ubiquitination. Exp Parasitol. 2007;116(4):440‐449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim IS, Lee M, Park JH, Jeon R, Baek SH, Kim KI. betaTrCP‐mediated ubiquitylation regulates protein stability of Mis18beta in a cell cycle‐dependent manner. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;443(1):62‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin DI, Barbash O, Kumar KGS, et al. Phosphorylation‐dependent ubiquitination of cyclin D1 by the SCF(FBX4‐alphaB crystallin) complex. Mol Cell. 2006;24(3):355‐366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kanie T, Onoyama I, Matsumoto A, et al. Genetic reevaluation of the role of F‐box proteins in cyclin D1 degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(3):590‐605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simoneschi D, Rona G, Zhou N, et al. CRL4(AMBRA1) is a master regulator of D‐type cyclins. Nature. 2021;592(7856):789‐793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chaikovsky AC, Li C, Jeng EE, et al. The AMBRA1 E3 ligase adaptor regulates the stability of cyclin D. Nature. 2021;592(7856):794‐798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rossi M, Duan S, Jeong YT, et al. Regulation of the CRL4(Cdt2) ubiquitin ligase and cell‐cycle exit by the SCF(Fbxo11) ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell. 2013;49(6):1159‐1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang YW, Brognard J, Coughlin C, et al. The F box protein Fbx6 regulates Chk1 stability and cellular sensitivity to replication stress. Mol Cell. 2009;35(4):442‐453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Choudhury R, Bonacci T, Arceci A, et al. APC/C and SCF(cyclin F) constitute a reciprocal feedback circuit controlling S‐phase entry. Cell Rep. 2016;16(12):3359‐3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carrano AC, Eytan E, Hershko A, Pagano M. SKP2 is required for ubiquitin‐mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1(4):193‐199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bornstein G, Bloom J, Sitry‐Shevah D, Nakayama K, Pagano M, Hershko A. Role of the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase in the degradation of p21Cip1 in S phase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(28):25752‐25757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Choudhury R, Bonacci T, Wang X, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase SCF(cyclin F) transmits AKT signaling to the cell‐cycle machinery. Cell Rep. 2017;20(13):3212‐3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vaites LP, Lee EK, Lian Z, et al. The Fbx4 tumor suppressor regulates cyclin D1 accumulation and prevents neoplastic transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(22):4513‐4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Busino L, Donzelli M, Chiesa M, et al. Degradation of Cdc25A by beta‐TrCP during S phase and in response to DNA damage. Nature. 2003;426(6962):87‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koepp DM, Kile AC, Swaminathan S, Rodriguez‐Rivera V. The F‐box protein Dia2 regulates DNA replication. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(4):1540‐1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burrows AC, Prokop J, Summers MK. Skp1‐Cul1‐F‐box ubiquitin ligase (SCF(betaTrCP))‐mediated destruction of the ubiquitin‐specific protease USP37 during G2‐phase promotes mitotic entry. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(46):39021‐39029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clijsters L, Hoencamp C, Calis JJA, et al. Cyclin F controls cell‐cycle transcriptional outputs by directing the degradation of the three activator E2Fs. Mol Cell. 2019;74(6):1264‐1277.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burdova K, Yang H, Faedda R, et al. E2F1 proteolysis via SCF‐cyclin F underlies synthetic lethality between cyclin F loss and Chk1 inhibition. EMBO J. 2019;38(20):e101443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Salvi JS, Kang J, Kim S, et al. ATR activity controls stem cell quiescence via the cyclin F‐SCF complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119(18):e2115638119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kanemori Y, Uto K, Sagata N. Beta‐TrCP recognizes a previously undescribed nonphosphorylated destruction motif in Cdc25A and Cdc25B phosphatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(18):6279‐6284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Busino L, Bassermann F, Maiolica A, et al. SCFFbxl3 controls the oscillation of the circadian clock by directing the degradation of cryptochrome proteins. Science. 2007;316(5826):900‐904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yumimoto K, Muneoka T, Tsuboi T, Nakayama KI. Substrate binding promotes formation of the Skp1‐Cul1‐Fbxl3 (SCF(Fbxl3)) protein complex. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(45):32766‐32776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Siepka SM, Yoo SH, Park J, et al. Circadian mutant overtime reveals F‐box protein FBXL3 regulation of cryptochrome and period gene expression. Cell. 2007;129(5):1011‐1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shirogane T, Jin J, Ang XL, Harper JW. SCFbeta‐TRCP controls clock‐dependent transcription via casein kinase 1‐dependent degradation of the mammalian period‐1 (Per1) protein. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(29):26863‐26872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marangos P, Verschuren EW, Chen R, Jackson PK, Carroll J. Prophase I arrest and progression to metaphase I in mouse oocytes are controlled by Emi1‐dependent regulation of APC(Cdh1). J Cell Biol. 2007;176(1):65‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guardavaccaro D, Kudo Y, Boulaire J, et al. Control of meiotic and mitotic progression by the F box protein beta‐Trcp1 in vivo. Dev Cell. 2003;4(6):799‐812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Frescas D, Pagano M. Deregulated proteolysis by the F‐box proteins SKP2 and beta‐TrCP: tipping the scales of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(6):438‐449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Han XR, Zha Z, Yuan HX, et al. KDM2B/FBXL10 targets c‐Fos for ubiquitylation and degradation in response to mitogenic stimulation. Oncogene. 2016;35(32):4179‐4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Qiu C, Yi YY, Lucena R, et al. F‐box proteins Pof3 and Pof1 regulate Wee1 degradation and mitotic entry in fission yeast. J Cell Sci. 2018;131(3):jcs202895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hanle‐Kreidler S, Richter KT, Hoffmann I. The SCF‐FBXW7 E3 ubiquitin ligase triggers degradation of histone 3 lysine 4 methyltransferase complex component WDR5 to prevent mitotic slippage. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(12):102703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fujii Y, Yada M, Nishiyama M, et al. Fbxw7 contributes to tumor suppression by targeting multiple proteins for ubiquitin‐dependent degradation. Cancer Sci. 2006;97(8):729‐736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hagedorn M, Delugin M, Abraldes I, et al. FBXW7/hCDC4 controls glioma cell proliferation in vitro and is a prognostic marker for survival in glioblastoma patients. Cell Div. 2007;2:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cheng Q, Yuan Y, Li L, et al. Deubiquitinase USP33 is negatively regulated by beta‐TrCP through ubiquitin‐dependent proteolysis. Exp Cell Res. 2017;356(1):1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nakayama K, Hatakeyama S, Maruyama SI, et al. Impaired degradation of inhibitory subunit of NF‐kappa B (I kappa B) and beta‐catenin as a result of targeted disruption of the beta‐TrCP1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(15):8752‐8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang L, Zhou F, Li Y, et al. Fas‐associated factor 1 is a scaffold protein that promotes beta‐transducin repeat‐containing protein (beta‐TrCP)‐mediated beta‐catenin ubiquitination and degradation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(36):30701‐30710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. D'Angiolella V, Donato V, Vijayakumar S, et al. SCF(cyclin F) controls centrosome homeostasis and mitotic fidelity through CP110 degradation. Nature. 2010;466(7302):138‐142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Krajewski A, Gagat M, Mikołajczyk K, Izdebska M, Żuryń A, Grzanka A. Cyclin F downregulation affects epithelial‐mesenchymal transition increasing proliferation and migration of the A‐375 melanoma cell line. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:13085‐13097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhao X, Guo W, Zou L, Hu B. FBXO2 modulates STAT3 signaling to regulate proliferation and tumorigenicity of osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20:245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]