Abstract

Objective

Rosmarinic acid (RosA) is a natural polyphenol compound that has been shown to be effective in the treatment of inflammatory disease and a variety of malignant tumors. However, its specific mechanism for the treatment of lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) has not been fully elucidated. Therefore, this study aims to clarify the mechanism of RosA in the treatment of LUAD by integrating bioinformatics, network pharmacology and in vivo experiments, and to explore the potential of the active ingredients of traditional Chinese medicine in treating LUAD.

Methods

Firstly, the network pharmacology was used to screen the RosA targets, and LUAD-related differential expressed genes (DEGs) were acquired from the GEO database. The intersection of LUAD regulated by RosA (RDEGs) was obtained through the Venn diagram. Secondly, GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of RDEGs were performed, and protein–protein interaction networks (PPIs) were constructed to identify and visualize hub RDEGs. Then, molecular docking between hub RDEGs and RosA was performed, and further evaluation was carried out by using bioinformatics for the predictive value of the hub RDEGs. Finally, the mechanism of RosA in the treatment of LUAD was verified by establishing a xenograft model of NSCLC in nude mouse.

Results

Bioinformatics and other analysis showed that, compared with the control group, the expressions of MMP-1, MMP-9, IGFBP3 and PLAU in LUAD tissues were significantly up-regulated, and the expressions of PPARG and FABP4 were significantly down-regulated, and these hub RDEGs had potential predictive value for LUAD. In vivo experimental results showed that RosA could inhibit the growth of transplanted tumors in nude mice bearing tumors of lung cancer cells, reduce the positive expression of Ki67 in lung tumor tissue, and hinder the proliferation of lung tumor cells. Upregulated expression of PPARG and FABP4 by activating the PPAR signaling pathway increases the level of ROS in lung tumor tissues and promotes apoptosis of lung tumor cells. In addition, RosA can also reduce the expression of MMP-9 and IGFBP3, inhibit the migration and invasion of lung tumor tissue cells.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that RosA could induce apoptosis by regulating the PPAR signaling pathway and the expression of MMP-9, inhibit the proliferation, migration and invasion of lung cancer cells, thereby exerting anti-LUAD effects. This study provides new insight into the potential mechanism of RosA in treating LUAD and provides a new therapeutic avenue for treatment of LUAD.

Keywords: Lung adenocarcinoma, Rosmarinic acid, Bioinformatics, Apoptosis, MMP-9, PPAR signaling pathway

Introduction

According to statistics, lung cancer will remain one of the most common malignant tumors globally and the leading cause of cancer deaths by 2024 [1]. Based on the histology of cancer cells, lung cancer can be divided into small cell lung cancer (SCLC, 15%) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC, 85%). In the NSCLC classification, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most common subtype [2]. Currently, the main recognized treatments for NSCLC include surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy [3]. However, conventional therapeutic drugs have limitations, and the side effects they produce limit their effectiveness in clinical treatment, and the quality of life and survival of patients remain a concern [4]. Therefore, it is crucial to explore safer and more effective therapeutic measures and anticancer substances to prevent the occurrence and development of lung cancer.

Traditional Chinese medicine is gradually becoming widely accepted as complementary and alternative medicine, bringing beneficial effects to the treatment of cancer [5]. Studies have shown that Chinese herbs can be used as an adjuvant therapy to improve the therapeutic efficacy, alleviate the toxic side effects of radiotherapy or chemotherapy, alleviate drug resistance, and delay recurrence and metastasis, thus improving the quality of life of the patients and increasing the survival rates [6]. These herbs have low toxicity and can exert anti-tumor mechanisms through the overall regulation of multiple channels, multiple links and multiple targets [7]. Studying the effective ingredients of Chinese herbal medicine against lung cancer is of great value and significance for the treatment of cancer.

Rosmarinic acid (RosA) is a natural polyphenol compound belonging to the Lamiaceae family and is widely found in various plants such as rosemary and salvia miltiorrhiza [8, 9]. According to reports, RosA has been proven to have anticancer pharmacological effects [10, 11]. Previous studies have shown that RosA can down-regulate the expression of MDR1 by activating the JNK signaling pathway, inhibit the proliferation of NSCLC cells and induce G1 cell cycle arrest, and reverse drug resistance to DDP [12]. Although many studies have shown that RosA inhibits EMT and tumor metastasis by inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, thereby inhibiting multiple solid tumors [13]. However, the molecular mechanism by which RosA inhibits LUAD remains largely unclear.

Therefore, in order to comprehensively understand the mechanism of action of RosA on LUAD, this study established a lung cancer nude mouse xenograft model to evaluate the inhibitory effect of RosA on the growth of NSCLC in vivo. In addition, we identified and validated the potential targets and pathways of RosA acting on LUAD through bioinformatics, network pharmacology and molecular docking analysis to further explore the mechanism of RosA treatment in LUAD.

Materials and methods

Network pharmacology and bioinformatics analysis

Acquisition of LUAD-DEGs and RosA targets

The microarray dataset of “Lung adenocarcinoma” was obtained from GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), and the species was set as “Homo Sapiens”, the GSE140797 (GPL13497 platform) and GSE116959 (GPL17077 platform) datasets were downloaded. The GSE140797 dataset contains information on 7 LUAD neoplastic samples with 7 adjacent non-neoplastic samples and the GSE116959 dataset contains information on 9 LUAD neoplastic samples with 9 adjacent non-neoplastic samples. The data from the two datasets were normalized using the “sva” package of R (4.3.1). Using the R “limma” package, with |log2FC|> 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 as the screening threshold. Differential expressed genes (DEGs) were collected between lung neoplastic samples and adjacent non-neoplastic samples, and volcano and heat maps were plotted.

Obtained the Canonical SMILES structure and 2D chemical structure of RosA from the Pubchem database (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), entered the SMILES number into the Swiss Target Prediction database (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/), set the species as "Homo sapiens", and screened targets with “Probability” > 0; The 2D chemical structure of RosA was imported into the PharmMapper database (http:/www.lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/) to screen for targets with Norm Fit scores at and above the median. And the target names were normalized by UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org). All the targets were combined and deduplicated to obtain the action targets of RosA. The DEGs obtained from the GSE140797 and GSE116959 datasets were intersected with the targets of RosA to obtain differential genes for RosA regulated LUAD (RDEGs).

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis

To further analyze the function of RDEGs, gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome (KEGG) enrichment analysis were performed on these RDEGs using R “clusterProfiler”, “org.Hs.eg.db” and “ggplot2” software packages. Setting adjusted p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Determination of the hub RDEGs

The PPI networks between RDEGs were constructed using the String platform (https://string-db.org/), the pattern is ‘‘multiple proteins’’, the organism is ‘‘Homo sapiens’’, and the required minimum interaction score is set to “High Confidence (0.700)”. The result files were imported into Cytoscape 3.10.1 software to construct a target interaction network, and the network topology was analyzed. Subsequently, the hub genes were screened using CytoHubba plug-in and maximal clique centrality (MCC) method. The hub RDEGs for RosA treatment of LUAD were obtained, and the differential expression levels of hub RDEGs between lung neoplastic samples and adjacent non-neoplastic samples were displayed using histograms.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking between RosA and hub RDEGs was carried out. The 3D structure of RosA was queried and downloaded from the PubChem database, and converted to Mol2 format using Open Babel GUI software. Find the appropriate 3D conformations of the hub RDEGs in the Uniprot database, screen and obtain its PDB based on the 3D conformations, enter the PDB id into the PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/) and download its corresponding crystal structure. After using AutoDock Tools 1.5.7 and PYMOL software to process RosA and hub RDEGs, molecular docking was performed through Auto Dock Vina, and the results with good binding energy were imported into PyMOL software for result visualization.

The validation of hub RDEGs expression and its clinical significance

The mRNA expression levels of hub RDEGs were verified based on the GSE27262 dataset (GPL570 platform), which included information from 25 LUAD neoplastic samples and adjacent non-neoplastic samples. In addition, we performed a clinical correlation analysis of hub RDEGs through the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) to assess the predictive value of these hub RDEGs.

In vivo experimental verification

Cell lines and reagents

A549 human NSCLC cells (CL-0016) were purchased from Pricella Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Cells were cultured in Ham’s F-12 K medium (PM150910) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, 164,210-50) and 1% Penicillin–Streptomycin solution (PB180120) in an incubator at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The reagents for cell culture were obtained from Pricella Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). RosA (Purity > 98%, B2086) was purchased from Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). RosA stock solution was prepared in sterile water and stored at – 20 ℃. Fluorescein (FITC) Tunel Cell Apoptosis Detection Kit (G1501) was purchased from Servicebio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Dihydroethidium (S0063) was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ultura Pure Total RNA Extraction Kit (5,003,050) was purchased from Simgen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). NovoScript®Plus All-in-one 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (E047-01B) and NovoStart® SYBR High-Sensitivity qPCR SuperMix (E099-01A) were purchased from Novoprotein Technology, Co., Ltd (Suzhou, China). BCA Protein Colorimetric Assay Kit (E-BC-K318-M) was purchased from Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). RIPA Lysis Buffer (CW2333S), SDS-PAGE Loading Buffer (CW0027S), protease inhibitor cocktail (CW2200S), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (CW2383S), SDS-PAGE Gel Kit (CW0022S) were purchased from CWBIO Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China).

MMP-9 (N-terminal) Polyclonal antibody (10,375-2-AP), IGFBP3 Polyclonal antibody (10,189-2-AP), PPAR Gamma Polyclonal antibody (16,643-1-AP), FABP4 Polyclonal antibody (12,802-1-AP), Ki67 Polyclonal antibody (27,309-1-AP) were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc (Wuhan, China). GAPDH antibody (AF7021) was purchased from Affinity Biosciences Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG conjugated HRP (ab6721) was purchased from Abcam plc (Cambridge, UK).

Animal models and treatments

A 4 weeks of age SPF Male BALB/C-nu mice, weighing (18 ± 2) g, were purchased from Hunan Slick Jingda Experimental Animal Co., Ltd. (Changsha, China) with the quality certificate number 430727241100650945. The mice were housed in separate cages in the SPF-grade laboratory of the Experimental Animal Center of Hunan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine at a temperature of 20–26 ℃ and a relative humidity of 40–70%. Artificial lighting was used, 12 h alternation of light and dark, and free diet.

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments of Hunan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Approval Number: LL2023051801) and were conducted in strict accordance with its animal experimental guidelines. After adaptative feeding for 3d, each mouse was injected with 5 × 105 A549 cells in the right axilla to establish a subcutaneous tumor model in nude mice. After 7 days, a mass was palpable at the inoculation site, and the nude mice were randomly divided into 3 groups: Control group, RosA low-dose group, and high-dose (25 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg gavage daily). During the intervention period, the body weight of nude mice, the length and width of tumors were measured every 3 days, and the tumor volume was calculated with the formula: tumor volume = 1/2 (length × width2), and the tumor growth curve was plotted. The mice were executed after 14 days of intervention, and the lung tumor tissues were carefully excised, partly frozen rapidly with liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for further analysis, and partly stored in 4% paraformaldehyde for subsequent pathological and immunohistochemical analysis. Before the operation, mice were anesthetized by inhaling 2% isoflurane for 2–3 min. After operation, mice were euthanized using the rapid cervical dislocation method. The maximum tumor size/burden allowed by the Ethics Committee for mice is 2000 mm3, which was not exceeded in our study.

Hematoxylin–Eosin (H&E) staining and Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay

Tumor tissues were taken and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, dehydrated, paraffin-embedded, and cut into sections of 5 μm thickness. The sections were placed on slides, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and the histopathological changes of the tumor were observed under light microscope. IHC was used to detect Ki67 protein expression level in tumor tissues. Paraffin sections of tumor tissues were deparaffinized and processed for antigen repair with citrate buffer. Subsequently, sections were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide solution protected from light for 25 min to block endogenous peroxidase. Afterwards, the sections were blocked with 3% BSA for 30 min, incubated with Ki67 antibody (1:2000) overnight at 4 °C, and incubated with its corresponding secondary antibody (HRP, 1:2000) for 1 h the following day. Finally, freshly configured DAB chromogen solution was added. After rinsing with tap water, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for 3 min, followed by re-blueing with hematoxylin blue solution, rinsed under running water, dehydrated and sealed. Images were taken with a light microscope.

TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

For the assay using the TUNEL kit, tumor paraffin sections were deparaffinized and incubated with proteinase K for 22 min in a 37 °C incubator. Subsequently, the tissues were ruptured with 0.1% triton solution, washed three times with PBS, and incubated with buffer at room temperature for 10 min. Afterwards, TUNEL reaction mixture (TdT enzyme, dUTP and buffer) was added and incubated at 37 ℃ for 1 h. The sections were counterstained with DAPI for 10 min protected from light. Finally, the sections were sealed with anti-fluorescence quenching sealer. Images were observed under an inverted fluorescence microscope.

Determination of reactive oxygen levels

Dihydroethidium was added dropwise to frozen sections of tumor tissue and incubated in an incubator at 37 ℃ protected from light for 30 min. The sections were washed three times with PBS, and DAPI staining solution was added and incubated for 10 min protected from light. Subsequently, the sections were blocked with anti-fluorescence quenching and then the images were observed under an inverted fluorescence microscope.

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

RT-qPCR was used to detect the mRNA expression levels of hub RDEGs MMP-9, PPARG, FABP4, and IGFBP3 in tumor tissues of nude mice bearing lung cancer after RosA intervention. According to the instructions supplied by the reagent manufacturer, Total RNA from tumor tissues of nude mice in the control group and RosA group was extracted using the Ultra Pure Total RNA Extraction Kit, and then reverse transcribed into cDNA using NovoScript® Plus All-in-one 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix. Finally, NovoStart® SYBR High-Sensitivity qPCR SuperMix and specific primers were used for amplification, and quantitative PCR analysis was performed on a real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR instrument. Using GAPDH as the house keeping gene, relative gene expression changes were determined by the 2−ΔΔCT method. The gene sequences are shown in Table 1. All qRT-PCR primers in the table are provided by Sangong Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Table 1.

Primer sequences of target genes

| Gene name | Forward sequence (5′—3′) | Reverse sequence (5′—3′) |

|---|---|---|

| MMP-9 | CGCCACCACAGCCAACTATGAC | CTGCTTGCCCAGGAAGACGAAG |

| PPARG | GCCAAGGTGCTCCAGAAGATGAC | GGTGAAGGCTCATGTCTGTCTCTG |

| FABP4 | TCACCGCAGACGACAGGAAGG | ACATTCCACCAGCTTGTCACCATC |

| IGFBP3 | CCGAGTGACCGATTCCAAGTTCC | AGTTCTGGGTGTCTGTGCTTTGAG |

| GAPDH | GGTTGTCTCCTGCGACTTCA | TGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTACTCC |

Western blotting

Western blotting was used to detect protein expression levels, and lung tumor tissues were lysed using RIPA Lysis Buffer (Strong) containing RIPA added with 1% protease inhibitor with 1% phosphatase inhibitor to extract total protein. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA kit. Each sample protein concentration was normalized with 5 × SDS-PAGE Loading Buffer. The samples were heated in a metal bath at 100 °C for 5–10 min, left to cool and stored at −20 °C for use. Prepare 10% separation gel and 5% concentration gel, and add 10 μl protein to each sample. SDS-PAGE electrophoresis was performed, and the proteins were transferred to the PVDF membrane by wet transfer method. Membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies [anti-MMP-9(1:1000), anti-PPARG(1:2000), anti-FABP4(1:5000), anti-IGFBP3(1:500), anti-GAPDH(1:3000)] at 4 °C overnight. On the following day, incubated with HRP secondary antibody (1:10,000) at room temperature for 1 h. The bands were visualized by ECL and scanned by chemiluminescence imaging system, and quantitative analysis of the associated protein expression was performed by Image J software.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.5 software and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The two groups were compared using a t-test and multiple groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (p < 0.05 marked*, p < 0.01 marked**, p < 0.001 marked***, and p < 0.0001 marked****).

Results

Network pharmacology and bioinformatics analysis

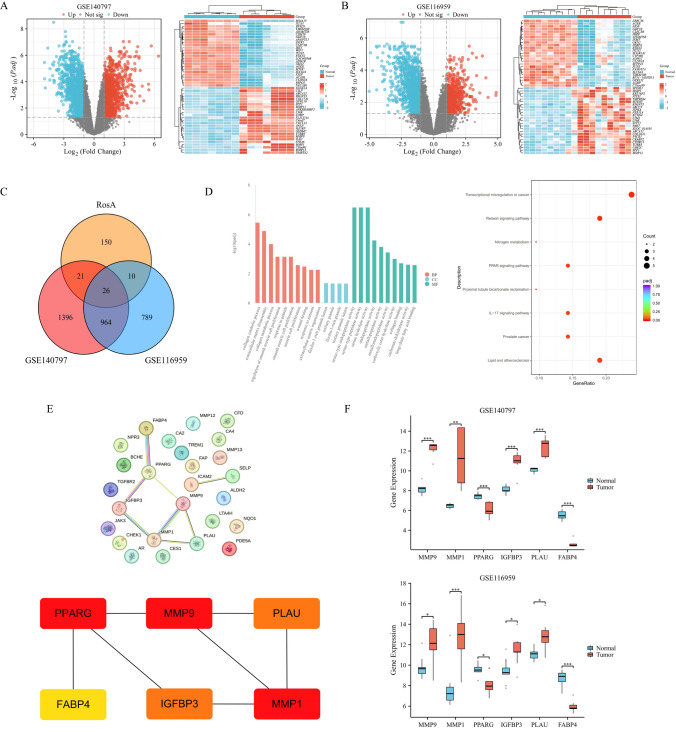

Determination of LUAD-DEGs and RosA targets for LUAD treatment

According to the screening conditions of |log2FC|> 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05, the LUAD groups were compared with the adjacent non-neoplastic groups. A total of 2407 DEGs were identified in the GSE140797 dataset, of which 1061 were up-regulated and 1346 were down-regulated. A total of 1789 DEGs were identified in the GSE116959 dataset, of which 580 were up-regulated and 1209 were down-regulated. The volcano plots and clustered heat maps of DEGs are shown in Fig. 1A and B. A total of 207 RosA drug targets were predicted using the Swiss Target Prediction and PharmMapper databases. We intersected the identified LUAD-DEGs with the targets of RosA, and identified 26 intersecting genes RDEGs of RosA for LUAD (Fig. 1C and Table 2). Subsequently, we performed GO functional and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis on these 26 RDEGs to elucidate the potential biological mechanisms of RosA for LUAD (Fig. 1D). Analysis of GO enrichment results showed that these RDEGs were mainly involved in biological processes such as collagen catabolic process, extracellular matrix disassembly, regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation, etc. The most pronounced enrichment in cellular components was in regions such as the ficolin-1-rich granule lumen and tertiary granule. In molecular function, RDEGs are mainly involved in serine-type endopeptidase activity, serine hydrolase activity, metallopeptidase activity and long-chain fatty acid binding. Analysis of KEGG enrichment results showed that RDEGs are mainly involved in Transcriptional mis-regulation in cancer, PPAR signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway and Prostate cancer.

Fig. 1.

Network pharmacology and bioinformatics analysis A, B Volcano plots of DEGs in GSE140797 and GSE116959 (LUAD group vs. adjacent non-neoplastic group), where red represents up-regulated genes and blue represents down-regulated genes. Heatmap of DEGs in GSE140797 and GSE116959 (blue area in the first row corresponds to adjacent non-neoplastic group, and red area corresponds to LUAD group), where red represents up-regulated genes and blue represents down-regulated genes. C Venn diagram show the overlap between DEGs and RosA-related genes in GSE140797 and GSE116959, with a total of 26 genes RDEGs that intersect with LUAD. D GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of RDEGs. E PPI network of RDEGs based on the STRING database and the top 6 hub RDEGs identified by the MMC method were MMP-9, MMP-1, PPARG, IGFBP3, PLAU, FABP4 (The darker the color, the higher the MCC score). F Box plots show the mRNA expression of 6 hub RDEGs in GSE140797 and GSE116959. The p-value was calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and the differences between groups were statistically significant

Table 2.

List of 26 RDEGs

| Gene symbols | Expression | Number |

|---|---|---|

| MMP-1, MMP-9, MMP-12, MMP-13, IGFBP3, JAK3, FAP, CHEK1, PLAU, NQO1 | Upregulated | 10 |

| CA2, CA4, SELP, BCHE, TREM1, FABP4, PPARG, CFD, AR, CES1, PDE5A, LTA4H, ALDH2, ICAM2, NPR3, TGFBR2 | Downregulated | 16 |

PPI network analysis and determination of the hub RDEGs

PPI network analysis was performed based on the STRING database and visualized by Cytoscape software. Subsequently, we identified the top 6 hub RDEGs based on the MCC method, including MMP-9, MMP-1, PPARG, IGFBP3, PLAU, and FABP4, as shown in Fig. 1E. We extracted the expression matrix of hub RDEGs from the GSE140797 and GSE116959 datasets and plotted the differential expression levels of the genes using box plots (Fig. 1F).

Molecular docking

We docked RosA with hub RDEGs (MMP-9, MMP-1, PPARG, IGFBP3, PLAU, FABP4). The results showed that the binding energy of these targets to the compound were all less than −5 kcal/mol (Table 3), indicating that RosA has strong binding to these targets, with the highest docking binding energy with MMP-9 and FABP4 being −9.2 kcal/mol. The docking results of each target are further visualized in Fig. 2.

Table 3.

Molecular docking of RosA with hub RDEGs

| Compounds | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMP-9 (1gkd) | MMP-1 (1cge) | PPARG (1zgy) | IGFBP3 (7wrq) | PLAU (1c5y) | FABP4 (3p6d) | |

| Rosmarinic acid | − 9.2 | − 8.2 | − 7.6 | − 7.4 | − 7.5 | − 9.2 |

Fig. 2.

Molecular docking map of RosA and hub RDEGs A rosmarinic acid docked with MMP-9. B rosmarinic acid docked with MMP-1. C rosmarinic acid docked with PPARG. D rosmarinic acid docked with IGFBP3. E rosmarinic acid docked with PLAU. E rosmarinic acid docked with PLAU. F rosmarinic acid docked with FABP4

Validation of hub RDEGs

The mRNA expression of 6 hub RDEGs in LUAD samples and adjacent non-neoplastic samples was verified based on the GSE27262 dataset. The results showed that the expression profiles of these genes were similar to those in the GSE140797 and GSE116959 datasets. As shown in Fig. 3A, compared with the adjacent non-neoplastic group, the expressions of MMP-9, MMP-1, IGFBP3, and PLAU in tumor samples were significantly up-regulated (p < 0.001), and the expressions of PPARG, FABP4 were significantly down-regulated (p < 0.001). We assessed the clinical significance of hub RDEGs in LUAD using the TCGA database, which included 598 tumor samples and 59 adjacent non-neoplastic samples. The analysis showed (Fig. 3B) that there were significant differences in the expression of hub RDEGs between LUAD and adjacent non-neoplastic samples, and the expression levels of these genes in TCGA were similar to those in the three GSE datasets mentioned above. In addition, we performed ROC analysis on hub RDEGs. The ROC curves showed that the AUC values of hub RDEGs were all > 0.7 (Fig. 3C), indicating that these genes are accurate and specific in diagnosing LUAD and have potential predictive value. Therefore, we believe that RosA may act as a therapeutic agent for LUAD by regulating the expression of these differential genes.

Fig. 3.

Clinical significance of hub RDEGs. A Expression of 6 hub RDEGs were validated in the GSE27262 dataset. The p-value was calculated using the Wilcoxo rank sum test, and the difference between groups was statistically significant. B Expression of 6 hub RDEGs based on the TCGA database. The p-value was calculated using the paired-samples T-test, and the difference between groups was statistically significant. C ROC analysis curve for hub RDEGs. The closer the AUC is to 1, the better the diagnostic effect of this variable in predicting outcomes

Animal experiments

RosA inhibits tumor growth in nude mice bearing A549 lung cancer

To determine the potential role of RosA in vivo, we used a xenograft model to investigate the inhibitory effect of RosA on tumor growth in nude mice bearing A549 lung cancer. The study found that compared with the control group, the RosA-treated group significantly reduced tumor volume in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. 4A, B). There were no significant changes in body weight in RosA-treated nude mice (Fig. 4C), indicating no adverse reactions. HE staining analysis showed that the tumor tissue in the control group was structurally intact and clear, with many nuclear divisions, abundant cytoplasm, tightly arranged, and few necrotic areas. Tumor tissue in the RosA group was morphologically ambiguous, with dispersed cells, reduced density, cytolysis, cellular breakage, a large number of vacuolated structures, and the presence of a large area of necrotic tumor cells (Fig. 4D). Ki67 immunohistochemical staining was used to detect cell proliferation. The results showed that Ki67 positive expression in RosA-treated nude mice was significantly reduced compared with the control group (Fig. 4E, F). In summary, it can be confirmed that RosA can inhibit the growth of lung tumors.

Fig. 4.

RosA inhibits tumor growth in nude mice bearing A549 lung cancer. A Images of tumor specimens from different treatment groups. B Changes in tumor volume in nude mice during RosA intervention. C Changes in body weight of nude mice during RosA intervention. D Pathological examination of HE staining of lung tumor tissues (200 ×). E Immunohistochemical analysis of Ki67 expression in lung tumor tissues (200 ×). F Statistical data on the percentage of Ki67-positive cells. All experiments were analyzed using 3 independent analyses, and data were expressed as mean ± SD. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 when compared with control group)

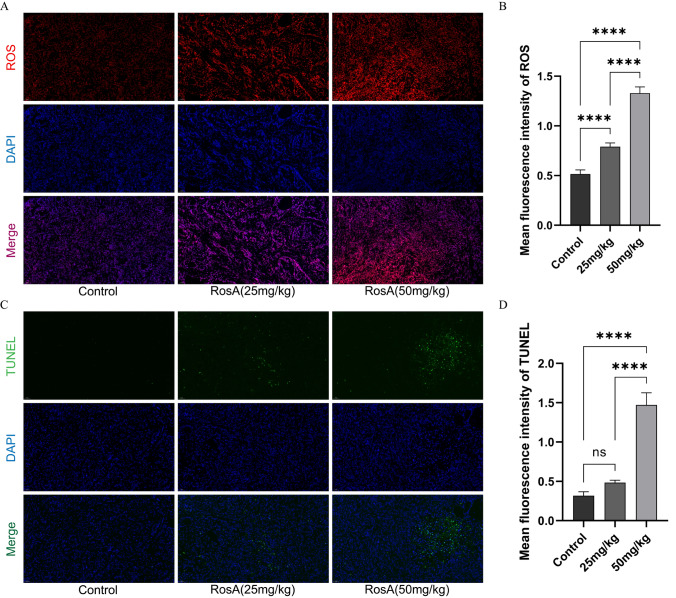

RosA increases ROS levels in lung tumor tissues and induces apoptosis

ROS can damage cell membranes and organelles, while excessive ROS can activate cell death processes such as apoptosis [14]. Therefore, we speculate that RosA-induced apoptosis might be triggered by excessive ROS production. Therefore, we measured ROS levels in tumor tissues of RosA-treated nude mice. As shown in Fig. 5A, compared with the control group, high and low doses of RosA enhanced the fluorescence intensity of ROS to different degrees. The statistical results are shown in Fig. 5B. It indicated that RosA increased ROS levels in tumor tissues in a concentration-dependent manner. Meanwhile, we further measured the level of RosA-induced apoptosis in tumor tissues by TUNEL staining, and the results showed that the number of TUNEL positive cells in the RosA group was significantly higher than that in the control group (Fig. 5C). The statistical results are shown in Fig. 5D. It indicated that RosA could promote apoptosis. In summary, the results of the present study may confirm that RosA promotes apoptosis in lung tumor tissues, which may be caused by the production of excessive ROS.

Fig. 5.

(A) ROS levels in lung tumor tissues were detected by fluorescent staining (200 ×). (B) Statistical data of the mean fluorescence intensity of ROS. (C) Apoptosis in lung tumor tissues were detected by TUNEL assay (200 ×). (D) Statistical data of the mean fluorescence intensity of TUNEL. All experiments were analyzed using 3 independent analyses, and data were expressed as mean ± SD. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 when compared with control group)

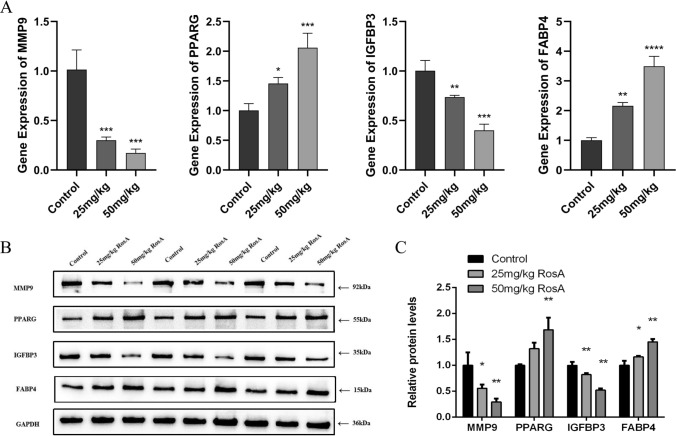

RosA down-regulated the expression of MMP-9 and IGFBP3 and upregulated the expression of PPARG and FABP4

In order to evaluate the results of bioinformatics and network pharmacology, and verify whether the therapeutic effect of RosA on LUAD is related to the regulation of “transcription factors in cancer” and “PPAR signaling pathway”, we used qRT-PCR and Western Blotting to detect the mRNA and protein expression levels of MMP-9, IGFBP3, PPARG, and FABP4. As shown in Fig. 6A, compared with the control group, RosA significantly upregulated the expression of PPARG and FABP4 mRNA, and significantly down-regulated the expression of MMP-9 and IGFBP3 mRNA (P < 0.001). Subsequent Western blotting further detected the significant effect of RosA on mRNA expression (Fig. 6B). Figure 6C shows that compared with the control group, RosA significantly upregulated the expression of PPARG and FABP4 proteins and activated the PPAR signaling pathway, MMP-9 and IGFBP3 protein expression was significantly downregulated (P < 0.01). Importantly, these results are consistent with those predicted by bioinformatics. In summary, RosA treats LUAD by regulating the expression levels of these genes and proteins.

Fig. 6.

mRNA and protein expression levels of hub RDEGs after different doses of RosA intervention. A RT-qPCR to detect the mRNA level of hub RDEGs. B Western blotting to detect protein levels of hub RDEGs. C Relative protein expression. All experiments were analyzed using 3 independent analyses, and data were expressed as mean ± SD. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 when compared with control group)

Discussion

Lung cancer is the malignant tumor with the highest morbidity and mortality rate in China and even in the world, among which LUAD is the most common pathological type, accounting for about 40–45% of lung cancers [15]. In recent years, great progress has been made in cancer management in terms of diagnosis and therapeutic means, which significantly improved patients’ life quality and prolonged their overall survival to a certain extent [16]. However, the anti-LUAD efficiency of these approaches is usually limited by inducing drug resistance and side effects, leading to tumor recurrence and poor prognosis [17]. Therefore, seeking safe and effective drugs and strategies remains a top priority for the treatment of LUAD. More and more studies have shown that traditional Chinese medicines with natural herbs have a wide range of pharmacological activities, and their inhibitory effects on tumors are manifested through multi-components, multi-targets, and multi-pathways, which provide a rational basis for the development of new anti-cancer drugs [18, 19]. Jing Bai et al. [20]found that that both aqueous and ethanol extracts of Salvia militorhiza and the active ingredients danshensu and dihydrotanshinone exhibited anti-tumor effects in vivo and in vitro. These extracts reduced the production of glycolysis metabolites in Lewis’s lung cancer cells, and inhibited aerobic glycolysis by decreasing the expression of the rate-limiting enzyme HK-II, thereby deprived energy of the tumor cells, induced tumor cells to apoptosis, and ultimately exerting anti-lung cancer effects. Haoyi Jin et al. [21] reported that both the Chinese herbal medicine Huaier and its active ingredient kaempferol inhibited growth of cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells in vivo and in vitro. The same extracts of Huaier also induced apoptosis in A549 and cisplatin-resistant A549 cells via inhibition of JNK/JUN/IL-8 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways [21], providing a new rationale for Huaier to be used as a new adjuvant drug in NSCLC patients after cisplatin chemotherapy. In addition to lung cancer, Chinese herbal medicines have also shown significant and potential therapeutic effects against other cancers. Studies have shown that polyphyllin I, the main active ingredient of the Chinese herb Paris polyphylla, inhibited growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. The possible mechanisms of polyphylla were the induction of oxidative stress, disruption of mitochondrial structure and function, and induced ferroptosis through the Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 axis, thereby inhibiting the proliferation, migration, and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells [22]. Celastrol, a triterpenoid compound extracted from the traditional Chinese medicine Tripterygium wilfordii, down-regulated the expression of HIF-α mRNA, inhibited the growth and migration of B16-F10 melanoma cells and induced apoptosis by activating the reactive oxygen species-dependent mitochondrial pathway and inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway [23]. Dandelion flavone, extract from Dandelion, effectively inhibited proliferation, migration and invasion of U266 myeloma cells, induced multiple myeloma cell apoptosis and inhibited M2 polarization of macrophages by targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway [24]. Collectively, these data provided that Chinese medicinal herbs have great potential for develop new anticancer drugs.

RosA is a natural compound widely found in the Chinese herbal medicines rosemary and salvia miltiorrhiza, which has been shown to have a variety of pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-microbial, antihypertensive and anti-cancer potential [25]. RosA treatment significantly inhibited the proliferation of SMMC-7221, liver cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner, and induced G1/S arrest and apoptosis of cells. In addition, RosA down-regulated the expression of MMP-9 and MMP2, regulated epithelial-mesenchymal transition to inhibit cell invasion, and slow down tumor development. This study also confirmed that RosA down-regulated the expression of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway-related proteins. Experimental results showed that RosA inhibited the proliferation and invasion of liver cancer cells and induced apoptosis by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway [26]. Similarly, another study demonstrated that RosA inhibited the PI3K/AKT pathway, down-regulated the expression of MMP-9 and MMP2, inhibited the invasion and migration of HepG2 liver cancer cells, and reduced the expression of Bcl-2 to induce apoptosis [27]. Xiang Zhou et al. [28] reported that RosA inhibited the growth of PDAC tumors by inhibiting Gli1. RosA induced G1/S cycle arrest and apoptosis in PDAC cells by promoting the degradation of Gli1 and regulating the expression of its downstream targets, and inhibited cell migration and invasion via MMP-9 and E-cadherin. In addition, anti-tumor activity of RosA has been observed in the treatment of breast cancer [29], colon cancer [30] and gastric cancers [31]. Although previous studies have demonstrated the inhibitory effects of RosA on multiple cancers, the potential molecular mechanisms of its anticancer effects on LUAD remain largely underexplored.

In this study, we combined bioinformatics and network pharmacology to investigate the key anti-LUAD pathways of RosA, and further explored the anti-LUAD mechanism of RosA through in vivo experiments. First, we screened the DEGs in LUAD based on the GEO dataset, with 1061 up-regulated genes and 1346 down-regulated genes in the GSE140797 dataset. 580 up-regulated genes and 1209 down-regulated genes in the GSE116959 dataset. A total of 207 drug targets of RosA were identified by Swiss Target Prediction and PharmMapper databases. Subsequently, we identified 26 potential anti-LUAD DEGs for RosA. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses revealed that these RDEGs are mainly involved in collagen catabolic process, extracellular matrix disassembly, metallopeptidase activity, long-chain fatty acid binding, transcriptional mis-regulation in cancer, PPAR signaling pathway and prostate cancer. Extracellular matrix (ECM) is important for cancer cell proliferation, migration, invasion, angiogenesis and immune escape [32, 33]. Collagen is an important component of the ECM and regulates a wide range of cellular behaviors. Dysregulation of collagen and abnormal deposition of collagen matrix contributes to tumor formation [34]. Furthermore, the ECM is highly dynamic in cancer, with ECM stiffness and remodeling interacting with each other and creating a vicious cycle that drives cancer progression. Increased ECM stiffness triggers mechanotransduction signaling that stimulates cancer cells and stromal cells to secrete MMPs. The increased activity of MMPs promotes the degradation and remodeling of ECM components. The remodeled ECM releases growth factors and cytokines that activate a variety of intracellular signaling programs to promote cancer cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and EMT. These signals also activate the remodeling of the ECM, which leads to further tumor evolution [35, 36]. PPARs are ligand-activated transcription factors belonging to nuclear hormone receptor family and consist of three isoforms: PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ. PPARs are considered to be major metabolic regulators, playing a central role in regulating energy homeostasis and determining many aspects of cell fate [37]. A growing number of studies have demonstrated the critical role of PPARs in malignant tumors, and activation of the PPAR signaling pathway is able to regulate multiple aspects of cancer, including proliferation and apoptosis, energy metabolism, angiogenesis, tumor microenvironment and immunomodulation [38–40].

Subsequently, we constructed a PPI network to further identify hub genes in these RDEGs. Based on the MCC algorithm, six hub RDEGs were finally identified, including MMP-9, MMP-1, PPARG, IGFBP3, PLAU, and FABP4, with MMP-9 having the highest connectivity (Fig. 1). We also performed molecular docking between RosA and these hub RDEGs, and the results showed that MMP-9 and FABP4 had the highest binding to RosA (Fig. 2). It is speculated that RosA regulates these hub RDEGs to exert its inhibitory effect on LUAD. In addition, we also conducted ROC analysis on hub RDEGs, and the results showed that the AUC values of hub RDEGs were all greater than 0.7, indicating that they have good predictive value for LUAD. This means that these genes may serve as reliable biomarkers for LUAD diagnosis and could also serve as potential therapeutic targets. A clinical study by Zhang et al. [41] found that the expression level of MMP-9 in serum of lung cancer patients was significantly higher than that of health persons, and the high expression of MMP-9 was closely associated with and significantly different from the TNM stage, differentiation degree, lymph node metastasis and smoking history of lung cancer. Importantly, the 3-year survival rate of lung cancer patients with high MMP-9 level was 12.67%, while the survival rate with low MMP9 level was 29.33% [41]. Similar result was reported by another group [42]. This suggested that the expression level of MMP-9 can be used as a prognostic indicator for lung cancer. In addition, results from animal studies also showed that the expression of MMP-9 in stage III and IV lung tumor tissues was significantly higher than that in stage I and II tumor tissues, which provides a more adequate theoretical basis that MMP-9 can be used as a prognostic indicator for lung tumors [43]. Other clinical studies have shown that the serum MMP-9 levels in patients with metastatic lung cancer are significantly higher than those in patients with non-metastatic lung cancer. Therefore, we can reduce the risk of metastatic prognosis of lung cancer by inhibiting the expression of MMP-9 [44]. MMP-1, which is in the same family as MMP-9, is also closely related to the prognosis of lung cancer. HoJung An et al. [45] examined preoperative serum and tumor tissue from 85 patients with surgically resected NSCLC and found out that MMP-1 was highly expressed in tumor cells compared to surrounding stromal cells. High serum MMP-1 showed a trend towards shorter overall survival and was strongly associated with early disease recurrence, adversely affecting disease prognosis. A recent study showed that high level of MMP-1/9 independently predicted recurrence and poorer overall survival after complete resection in patients with stage I LUAD, predicting poor survival outcomes [46]. In addition, MMP-1/9 is also involved in tumor drug resistance. Overexpression of MMP-1/9 induces resistance to EGFR-TKIs and platinum drugs in lung cancer cells, and inhibition of their expression helps to reduce the resistance of lung cancer cells to these anticancer drugs [47]. Compared with MMP1/9, other hub RDEGs have fewer reported clinically relevant and prognostic studies of lung cancer in recent years. Research by Jiao Wang et al. revealed that the expression of IGFBP3 mRNA in lung tumor tissues was significantly higher than that in normal tissues and was significantly correlated with poor overall survival in NSCLC patients [48]. FU et al. [49] evaluated PLUA expression levels between stages I and II tumor and reported that high expression levels of PLUA were associated with high stage, and the overall survival of patients with LUAD deteriorated with stage. In addition, immune infiltration was also observed in patients with LUAD, indicating that immune cells are involved in the progression of LUAD, which is regulated by high expression levels of PLUA. Zhang et al. [50] performed single-cell RNA sequencing and identified a new subpopulation of FABP4+C1q+ macrophages. It was found out that FABP4 and C1q could synergistically promoted fatty acid synthesis and enhanced the anti-apoptotic and phagocytic abilities of macrophages. The results suggest that FABP4 plays a critical immunomodulatory role as a novel macrophage biomarker and may improve the clinical outcome of NSCLC patients in the future [50]. In summary, more clinical studies and predictive models to reflect the relationship between gene expression levels and patient prognosis and disease progression are needed.

Next, we verified whether RosA had an inhibitory effect on LUAD. Our animal study showed that RosA significantly inhibited the growth of LUAD xenograft tumors without causing weight loss. In addition, in lung tumor tissues, RosA showed potent anti-proliferative (decrease number of Ki67-positive cells) and pro-apoptotic (increase number of TUNEL-positive cells) effects. In the present study, we also found a significant increase in ROS production after RosA treatment. ROS are highly reactive molecules that play a dual role in cancer. Moderate levels of ROS damage DNA, activate inflammatory responses and induce angiogenesis, promoting cancer development and progression, while high levels of ROS initiate oxidative stress and activate apoptosis signaling pathways to induce tumor cell death, including mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress and DNA damage [51, 52]. Mitochondria are the source and target site of ROS and play an important role in initiating apoptosis. Mitochondria activate caspases through cytochrome c, leading to cell lysis and apoptosis. In addition, ROS can also activate transmembrane death receptors, form death-inducing complexes, block Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic activity, activate Bax, and trigger apoptosis [53]. It has been shown that naringenin is able to promote lung cancer cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by increasing ROS production, leading to caspase cascade activation [54]. Similarly, another experiment also confirmed that apoptosis in lung cancer cells is induced by increased levels of ROS [55]. Based on the results of the present study, we conclude that RosA is able to promote apoptosis in lung tumor tissues by mediating ROS production.

To validate the results of bioinformatics and network pharmacology analysis, we selected MMP-9 and IGFBP3 in cancer transcription factors, and PPARG and FABP4 in PPAR signaling pathway for further analysis. We determined the expression of these genes and proteins by qRT-PCR and Western blotting. qRT-PCR results showed that the expression of MMP-9 and IGFBP3 in RosA-treated nude mice was significantly lower than that in Control group, while the expression of PPARG and FABP4 in RosA was significantly higher than that in Control group. The proteins corresponding to these genes obtained similar trends in the WB assay. This proved to be consistent with the results predicted by bioinformatics.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc-dependent endopeptidases, and gelatinases are an important type of the MMPs family, including MMP-9. MMP-9 plays an important role in cancer angiogenesis, apoptosis, invasion and metastasis. Activation of MMP-9 in cancer degrades and reshapes ECM and releases membrane-bound growth factors to provide a favorable microenvironment for tumors [56, 57]. Several clinical studies have shown that the expression of MMP-9 in lung cancer tissues is significantly higher than that in adjacent non-neoplastic tissues, and is associated with the pathological type and clinical stage of lung cancer [41, 42, 58]. Experimental studies have also confirmed these ideas. Jie Lang [59] demonstrated that Puerarin can significantly reduce the expression level of MMP-9 protein in lung cancer cells and inhibit cell invasion and metastasis. In addition, Ki-Eun Hwang [60] showed that Salinomycin inhibits EMT through down-regulation of MMP-9 via the AMPK/SIRT pathway, which in turn inhibits invasion and metastasis of NSCLC cells. Another study [61] showed that Eupafolin was able to inhibit the proliferation, migration and invasion of lung cancer A549 cells and H1299 cells, which was achieved by inhibiting the expression of MMP-9 through the FAK/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Therefore, the invasion and metastasis of cancer cells can be inhibited by suppressing the expression of MMP-9.

The insulin growth factor (IGF) pathway plays a carcinogenic role in the occurrence and development of many malignant diseases. The IGF pathway consists of the ligands IGF-1/2, receptors IGF-1/2R, and the binding protein IGFBP1-6. Aberrant expression of IGF, IGFR and IGFBP has been shown to be associated with metastasis, treatment resistance and poor prognosis in a variety of malignant tumors [62]. IGFBP3 is the most widely studied IGFBP protein, and it has a dual role in cancer development. Some studies have found that IGFBP3 can inhibits both apoptosis and tumor growth, which may be related to the protein it binds to [63, 64]. However, IGFBP3 expression was generally higher in NSCLC tissues than in normal tissues, which may be related to the disruption of IGFBP3 at the transcriptional and post-translational levels [65]. IGFBP3 is able to enhance the activity of IGF by proteolytically cleaving IGFBPs or binding to heparin and proteoglycans, which promotes NSCLC cell growth and migration [66, 67]. Lishi Yang et al. [68] found that the expression of IGFBP3 in lung tumor specimens was significantly higher than that in normal lung tissues, and in vitro experiments demonstrated that IGFBP3 was able to promote the migration, invasion and EMT of lung cancer A549 cells through the TGF-β/Smad4 signaling pathway. In addition, another study showed that down-regulation of IGFBP3 could alleviate XBP1-induced MMP-9 overexpression and inhibited NSCLC tumor invasion, metastasis and EMT [69].

Fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) is a fatty acid carrier protein widely found in adipocytes and macrophages. It is mainly involved in lipid metabolism homeostasis, inflammatory response and intracellular signaling [70].The function of FABP4 in tumors is extremely complex, and it can play multiple roles depending on the type of tumor and participate in the regulation of multiple signaling pathways. Recently, it was shown that overexpression of FABP4 was able to inhibit endometrial cancer proliferation, migration and invasion in vitro by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [71]. In addition, FABP4 was able to inhibit the growth of liver tumors in vivo, as well as inhibit the proliferation and migration of liver cancer cells by modulating Snail and p-STAT3 signaling [72]. Notably, Zhen LI et al. demonstrated that FABP4 was lowly expressed in NSCLC, and knocking down SIRT5 significantly elevated FABP4 expression and inhibited NSCLC cell progression [73]. Similarly, another analysis also demonstrated that FABP4 has an anti-cancer effect in LUAD [74].

PPARG is the most widely studied member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, and its expression has been explored in a variety of cancers, including liver cancer [75], bladder cancer [76], breast cancer [77], colorectal cancer [78], and lung cancers [79]. PPARG plays an important role in lipid and glucose metabolism, immune regulation, inflammatory pathways and tumor progression [80]. Activation of PPARG can promote cancer cell cycle arrest, induce apoptosis, inhibit cell migration, invasion and EMT, reduce the production of pro-inflammatory factors, thereby inhibiting tumors [81]. It was shown that DHA-PC and EPA-PC were able to inhibit tumor growth in Lewis’s lung cancer mice by activating the expression of PPARG, which in turn down-regulated the NF-κB pathway and reduced the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2 to promote tumor cell apoptosis. In addition, the level of MMP-9 was also significantly reduced, inhibiting ECM degradation and thus suppressing lung metastasis [82]. Another study also showed that CLA was able to inhibit the proliferation of A549 cells by enhancing the expression of PPARG, enhance the expression level of apoptotic genes, and induce apoptosis [83]. Interestingly, activation of PPARG can induce apoptosis in A549 cells through a ROS-dependent mechanism [84, 85]. This is consistent with the mechanism of ROS being able to induce apoptosis as discussed above. In addition, PPARG modulates lipid metabolism in cancer by regulating lipid accumulation and lipolysis in adipocytes [86]. It has been shown that PPARG-mediated lipid synthesis reduces NADPH levels, leading to increased mitochondrial ROS levels, which in turn induces oxidative stress and inhibits the growth of lung cancer cells [87]. FABP4 is reported to be a downstream target gene of PPARG in lipid metabolism, FABP4 promotes PPARG activation by translocating ligands to PPARG, and the expression of PPARG and FABP4 is positively correlated. By activating the expression of the PPARG/FABP4 signaling axis can reduce lipid accumulation and promote lipolysis, thereby increasing endogenous ROS levels and helping to inhibit cancer progression [88–90] (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Molecular mechanism of RosA inhibiting LUAD in nude mice bearing A549 lung cancer

Conclusion

In summary, our study demonstrated that RosA effectively inhibited tumor growth in lung cancer A549 tumor-bearing nude mice and promoted apoptosis of lung tumor cells by increasing ROS levels. The molecular mechanism of RosA action was further elucidated by bioinformatics analysis, qRT-PCR and Western blotting, revealing that it could induce apoptosis in lung tumor cells by activating the PPAR signaling pathway. In addition, the downregulation of MMP-9 expression inhibited the metastasis and invasion of lung tumor cells. This study elucidated the mechanism of RosA in LUAD, which provides a new way and mechanism for the prevention and treatment of LUAD.

This study has some limitations. 1. We only verified that RosA could promote apoptosis in lung tumor cells by TUNEL staining, and did not detect the expression of apoptosis-related proteins such as Bcl-2 or Bax. 2. Lack of cellular experiments to further confirm the inhibitory effect of RosA on the migration and invasion of lung tumor cells. 3. Whether RosA promotes apoptosis of lung cancer cells by mediating the generation of ROS has not been sufficiently confirmed. Whether RosA promotes apoptosis by mediating ROS generation has not been fully demonstrated, and the reactive oxygen species scavenger N-acetylcysteine (NAC) should be used to test whether intracellular reactive oxygen species generation leads to cell death. 4. Whether RosA inhibits the progression of LUAD by regulating lipid metabolism needs to be further investigated and demonstrated. Although the exact mechanism of action remains to be further investigated, this study provides a theoretical basis for future experiments. Next, we will continue to perform transcriptomics and metabolomics on lung tumor tissues from nude mice in the Control group and RosA group to deeply explore the regulatory mechanisms of complex physiological processes, and provide more evidence for the mechanism of RosA in treating LUAD.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Traditional Chinese Medicine Diagnostics and Hunan Engineering Technology Research Center for Medicinal and Functional Food for providing the experimental platform and technical support. We are grateful to Prof. Mengzhou Xie, Dr. Zuomei He and Xiaoning Tan for providing financial support. We thank Prof. Jianzhong Cao for his valuable comments and suggestions.

Author contributions

Zhou designed and performed most of the experiment and wrote draft manuscript. Zhong analyzed the data. Zhou, Zhang, Luo, Lei performed animal study. Cao instructed the experiment and made modification on manuscript. Li, Yuan, Qu, Yang discussed the data and made modification on manuscript. Xie, He, Tan instructed the experiment and provided the funding for the experiment.

Funding

This study supported by National Natural Youth Science Foundation, (No.8220154434), Key Research and Development Program of Hunan Province of China, (2023SK2057).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Traditional Chinese Medicine Diagnostics. All animal experimental procedures were carried out following the Hunan University of Chinese Medicine Animal Experimentation Ethics Guidelines (Approval Number: LL2023051801). This study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines, and all subcutaneous tumors in mice were less than 20 mm in diameter, meeting IRB criteria.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mengzhou Xie, Email: xiemz64@163.com.

Haoyu Qu, Email: quhaoyu@hnucm.edu.cn.

Zuomei He, Email: 281144800@qq.com.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024. 10.3322/caac.21820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, Meza R, Kong CY, Cronin KA, et al. The effect of advances in lung-cancer treatment on population mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020. 10.1056/NEJMoa1916623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stefani D, Plönes T, Viehof J, Darwiche K, Stuschke M, Schuler M, et al. Lung cancer surgery after neoadjuvant immunotherapy. Cancers. 2021. 10.3390/cancers13164033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Scordilli M, Michelotti A, Bertoli E, De Carlo E, Del Conte A, Bearz A. Targeted therapy and immunotherapy in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: current evidence and ongoing trials. Int J Mol Sci. 2022. 10.3390/ijms23137222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiang Y, Guo Z, Zhu P, Chen J, Huang Y. Traditional Chinese medicine as a cancer treatment: Modern perspectives of ancient but advanced science. Cancer Med. 2019. 10.1002/cam4.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Qiu H, Li C, Cai P, Qi F. The positive role of traditional Chinese medicine as an adjunctive therapy for cancer. Biosci Trends. 2021. 10.5582/bst.2021.01318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang K, Chen Q, Shao Y, Yin S, Liu C, Liu Y, et al. Anticancer activities of TCM and their active components against tumor metastasis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng W, Wang SY. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in selected herbs. J Agric Food Chem. 2001. 10.1021/jf010697n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen M, Abdullah Y, Benner J, Eberle D, Gehlen K, Hücherig S, et al. Evolution of rosmarinic acid biosynthesis. Phytochemistry. 2009. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulgakov VP, Inyushkina YV, Fedoreyev SA. Rosmarinic acid and its derivatives: biotechnology and applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2012. 10.3109/07388551.2011.596804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ijaz S, Iqbal J, Abbasi BA, Ullah Z, Yaseen T, Kanwal S, et al. Rosmarinic acid and its derivatives: current insights on anticancer potential and other biomedical applications. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao XZ, Gao Y, Sun LL, Liu JH, Chen HR, Yu L, et al. Rosmarinic acid reverses non-small cell lung cancer cisplatin resistance by activating the MAPK signaling pathway. Phytother Res. 2020. 10.1002/ptr.6584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao J, Xu L, Jin D, Xin Y, Tian L, Wang T, et al. Rosmarinic acid and related dietary supplements: potential applications in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Biomolecules. 2022. 10.3390/biom12101410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redza-Dutordoir M, Averill-Bates DA. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863(12):2977–92. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song Y, Kelava L, Kiss I. MiRNAs in lung adenocarcinoma: role, diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. 10.3390/ijms241713302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang M, Herbst RS, Boshoff C. Toward personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2021;27(8):1345–56. 10.1038/s41591-021-01450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo H, Vong CT, Chen H, Gao Y, Lyu P, Qiu L, et al. Naturally occurring anti-cancer compounds: shining from Chinese herbal medicine. Chin Med. 2019;14:48. 10.1186/s13020-019-0270-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su XL, Wang JW, Che H, Wang CF, Jiang H, Lei X, et al. Clinical application and mechanism of traditional Chinese medicine in treatment of lung cancer. Chin Med J. 2020;133(24):2987–97. 10.1097/cm9.0000000000001141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai J, Qin Q, Li S, Cui X, Zhong Y, Yang L, et al. Salvia miltiorrhiza inhibited lung cancer through aerobic glycolysis suppression. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;331:118281. 10.1016/j.jep.2024.118281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin H, Liu C, Liu X, Wang H, Zhang Y, Liu Y, et al. Huaier suppresses cisplatin resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by inhibiting the JNK/JUN/IL-8 signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;319(Pt 2):117270. 10.1016/j.jep.2023.117270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang R, Gao W, Wang Z, Jian H, Peng L, Yu X, et al. Polyphyllin I induced ferroptosis to suppress the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma through activation of the mitochondrial dysfunction via Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 axis. Phytomedicine. 2024;122:155135. 10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao P, He XB, Chen XY, Li ZL, Xing WJ, Liu W, et al. Celastrol inhibits mouse B16–F10 melanoma cell survival by regulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and repressing HIF-1α expression. Discov Oncol. 2024;15(1):178. 10.1007/s12672-024-01045-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gui H, Fan X. Anti-tumor effect of dandelion flavone on multiple myeloma cells and its mechanism. Discov Oncol. 2024;15(1):215. 10.1007/s12672-024-01076-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noor S, Mohammad T, Rub MA, Raza A, Azum N, Yadav DK, et al. Biomedical features and therapeutic potential of rosmarinic acid. Arch Pharm Res. 2022;45(4):205–28. 10.1007/s12272-022-01378-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Yang H, Wang C, Shi X, Li K. Rosmarinic acid inhibits proliferation and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells SMMC 7721 via PI3K/AKT/mTOR signal pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;120:109443. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.An Y, Zhao J, Zhang Y, Wu W, Hu J, Hao H, et al. Rosmarinic acid induces proliferation suppression of hepatoma cells associated with NF-κB signaling pathway. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2021;22(5):1623–32. 10.31557/apjcp.2021.22.5.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou X, Wang W, Li Z, Chen L, Wen C, Ruan Q, et al. Rosmarinic acid decreases the malignancy of pancreatic cancer through inhibiting Gli1 signaling. Phytomedicine. 2022;95:153861. 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Messeha SS, Zarmouh NO, Asiri A, Soliman KFA. Rosmarinic acid-induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;885:173419. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han YH, Kee JY, Hong SH. Rosmarinic acid activates AMPK to inhibit metastasis of colorectal cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:68. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li W, Li Q, Wei L, Pan X, Huang D, Gan J, et al. Rosmarinic acid analogue-11 induces apoptosis of human gastric cancer SGC-7901 cells via the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)/Akt/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2019;25:63–75. 10.12659/msmbr.913331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eble JA, Niland S. The extracellular matrix in tumor progression and metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2019;3:171–98. 10.1007/s10585-019-09966-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang Y, Zhang H, Wang J, Liu Y, Luo T, Hua H. Targeting extracellular matrix stiffness and mechanotransducers to improve cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):34. 10.1186/s13045-022-01252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Martino D, Bravo-Cordero JJ. Collagens in cancer: structural regulators and guardians of cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2023;83(9):1386–92. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-22-2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Felice D, Alaimo A. Mechanosensitive piezo channels in cancer: focus on altered calcium signaling in cancer cells and in tumor progression. Cancers. 2020. 10.3390/cancers12071780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker AL, Cox TR. The role of the ECM in lung cancer dormancy and outgrowth. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1766. 10.3389/fonc.2020.01766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Pan Y, Zhao X, Wu S, Li F, Wang Y, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: a key link between lipid metabolism and cancer progression. Clin Nutr. 2024;43(2):332–45. 10.1016/j.clnu.2023.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagner N, Wagner KD. PPAR beta/delta and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Cells. 2020. 10.3390/cells9051133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner N, Wagner KD. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and the hallmarks of cancer. Cells. 2022. 10.3390/cells11152432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Xiao B, Liu Y, Wu S, Xiang Q, Xiao Y, et al. Roles of PPAR activation in cancer therapeutic resistance: Implications for combination therapy and drug development. Eur J Pharmacol. 2024;5(964):176304. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.176304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang H, Zhao B, Zhai ZG, Zheng JD, Wang YK, Zhao YY. Expression and clinical significance of MMP-9 and P53 in lung cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(3):1358–65. 10.2355/eurrev_202102_24844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Badrawy MK, Yousef AM, Shaalan D, Elsamanoudy AZ. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in lung cancer patients and its relation to serum mmp-9 activity, pathologic type, and prognosis. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2014;21(4):327–34. 10.1097/lbr.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang DH, Zhang LY, Liu DJ, Yang F, Zhao JZ. Expression and significance of MMP-9 and MDM2 in the oncogenesis of lung cancer in rats. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7(7):585–8. 10.1016/s1995-7645(14)60099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balla MMS, Patwardhan S, Melwani PK, Purwar P, Kumar A, Pramesh CS, et al. Prognosis of metastasis based on age and serum analytes after follow-up of non-metastatic lung cancer patients. Transl Oncol. 2021. 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.An HJ, Lee YJ, Hong SA, Kim JO, Lee KY, Kim YK, et al. The prognostic role of tissue and serum MMP-1 and TIMP-1 expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2016;212(5):357–64. 10.1016/j.prp.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu CH, Di YP. Matrix metallopeptidase-gene signature predicts stage I lung adenocarcinoma survival outcomes. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. 10.3390/ijms24032382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei C. The multifaceted roles of matrix metalloproteinases in lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1195426. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1195426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pohlman AW, Moudgalya H, Jordano L, Lobato GC, Gerard D, Liptay MJ, et al. The role of IGF-pathway biomarkers in determining risks, screening, and prognosis in lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2022;13:393–407. 10.18632/oncotarget.28202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu D, Hu Z, Ma H, Xiong X, Chen X, Wang J, et al. PLAU and GREM1 are prognostic biomarkers for predicting immune response in lung adenocarcinoma. Medicine. 2024;103(5):e37041. 10.1097/md.0000000000037041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang D, Wang M, Liu G, Li X, Yu W, Hui Z, et al. Novel FABP4(+)C1q(+) macrophages enhance antitumor immunity and associated with response to neoadjuvant pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in NSCLC via AMPK/JAK/STAT axis. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(10):717. 10.1038/s41419-024-07074-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moloney JN, Cotter TG. ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tuli HS, Kaur J, Vashishth K, Sak K, Sharma U, Choudhary R, et al. Molecular mechanisms behind ROS regulation in cancer: A balancing act between augmented tumorigenesis and cell apoptosis. Arch Toxicol. 2023;97(1):103–20. 10.1007/s00204-022-03421-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakamura H, Takada K. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: current findings and future directions. Cancer Sci. 2021. 10.1111/cas.15068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang TM, Chi MC, Chiang YC, Lin CM, Fang ML, Lee CW, et al. Promotion of ROS-mediated apoptosis, G2/M arrest, and autophagy by naringenin in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20(3):1093–109. 10.7150/ijbs.85443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang FY, Li RZ, Xu C, Fan XX, Li JX, Meng WY, et al. Emodin induces apoptosis and suppresses non-small-cell lung cancer growth via downregulation of sPLA2-IIa. Phytomedicine. 2022;95:153786. 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mondal S, Adhikari N, Banerjee S, Amin SA, Jha T. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and its inhibitors in cancer: a minireview. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;194:112260. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Almeida LGN, Thode H, Eslambolchi Y, Chopra S, Young D, Gill S, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases: from molecular mechanisms to physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 2022;74(3):712–68. 10.1124/pharmrev.121.000349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gong L, Wu D, Zou J, Chen J, Chen L, Chen Y, et al. Prognostic impact of serum and tissue MMP-9 in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(14):18458–68. 10.18632/oncotarget.7607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lang J, Guo Z, Xing S, Sun J, Qiu B, Shu Y, et al. Inhibitory role of puerarin on the A549 lung cancer cell line. Transl Cancer Res. 2022;11(11):4117–25. 10.21037/tcr-22-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hwang KE, Kim HJ, Song IS, Park C, Jung JW, Park DS, et al. Salinomycin suppresses TGF-β1-induced EMT by down-regulating MMP-2 and MMP-9 via the AMPK/SIRT1 pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18(3):715–26. 10.7150/ijms.50080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X, Huang M, Xie W, Ding Q, Wang T. Eupafolin regulates non-small-cell lung cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by suppressing MMP9 and RhoA via FAK/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. J Biosci. 2023. 10.1007/s12038-022-00323-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen YM, Qi S, Perrino S, Hashimoto M, Brodt P. Targeting the IGF-axis for cancer therapy: development and validation of an igf-trap as a potential drug. Cells. 2020. 10.3390/cells9051098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cai Q, Dozmorov M, Oh Y. IGFBP-3/IGFBP-3 receptor system as an anti-tumor and anti-metastatic signaling in cancer. Cells. 2020. 10.3390/cells9051261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Varma Shrivastav S, Bhardwaj A, Pathak KA, Shrivastav A. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3): unraveling the role in mediating IGF-independent effects within the cell. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:286. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang J, Hu ZG, Li D, Xu JX, Zeng ZG. Gene expression and prognosis of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein family members in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2019;42(5):1981–95. 10.3892/or.2019.7314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bach LA. IGF-binding proteins. J Mol Endocrinol. 2018;61(1):T11-t28. 10.1530/jme-17-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu X, Qiu Y, Chen S, Wang S, Yang R, Liu B, et al. Different roles of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) axis in non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2022;28(25):2052–64. 10.2174/1381612828666220608122934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang L, Li J, Fu S, Ren P, Tang J, Wang N, et al. Up-regulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 Is associated with brain metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Cells. 2019;42(4):321–32. 10.14348/molcells.2019.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Luo Q, Shi W, Dou B, Wang J, Peng W, Liu X, et al. XBP1- IGFBP3 signaling pathway promotes NSCLC Invasion and Metastasis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:654995. 10.3389/fonc.2021.654995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Y, Zhang W, Xia M, Xie Z, An F, Zhan Q, et al. High expression of FABP4 in colorectal cancer and its clinical significance. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2021;22(2):136–45. 10.1631/jzus.B2000366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu Z, Jeong JH, Ren C, Yang L, Ding L, Li F, et al. Fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4) suppresses proliferation and migration of endometrial cancer cells via PI3K/Akt pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:3929–42. 10.2147/ott.S311792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhong CQ, Zhang XP, Ma N, Zhang EB, Li JJ, Jiang YB, et al. FABP4 suppresses proliferation and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells and predicts a poor prognosis for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2018;7(6):2629–40. 10.1002/cam4.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li Z, Yu DP, Wang N, Tao T, Luo W, Chen H. SIRT5 promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression by reducing FABP4 acetylation level. Neoplasma. 2022;69(4):909–17. 10.4149/neo_2022_220107N28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hsu YL, Hung JY, Lee YL, Chen FW, Chang KF, Chang WA, et al. Identification of novel gene expression signature in lung adenocarcinoma by using next-generation sequencing data and bioinformatics analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(62):104831–54. 10.18632/oncotarget.21022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu YM, Li XQ, Zhang XR, Chen YY, Liu YP, Zhang HQ, et al. Uncovering the key pharmacodynamic material basis and possible molecular mechanism of extract of Epimedium against liver cancer through a comprehensive investigation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;317:116765. 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tate T, Xiang T, Wobker SE, Zhou M, Chen X, Kim H, et al. Pparg signaling controls bladder cancer subtype and immune exclusion. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):6160. 10.1038/s41467-021-26421-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wilson HE, Stanton DA, Rellick S, Geldenhuys W, Pistilli EE. Breast cancer-associated skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction and lipid accumulation is reversed by PPARG. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021. 10.1152/ajpcell.00264.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schöckel L, Woischke C, Surendran SA, Michl M, Schiergens T, Hölscher A, et al. PPARG activation promotes the proliferation of colorectal cancer cell lines and enhances the antiproliferative effect of 5-fluorouracil. BMC Cancer. 2024. 10.1186/s12885-024-11985-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang L, Wang Z, Ni Y, Wang X, Zhang T, Hu M, et al. Elucidating the mechanism of action of Isobavachalcone induced autophagy and apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer by network pharmacology and experimental validation methods. Gene. 2024;5(918):148474. 10.1016/j.gene.2024.148474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yuvaraj S, Kumar BRP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ as a novel and promising target for treating cancer via regulation of inflammation: a brief review. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2022;22(1):3–14. 10.2174/1389557521666210422112740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang X, Yang R, Zhang Y, Shi Y, Ma M, Li F, et al. Xianlinglianxiafang Inhibited the growth and metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer via activating PPARγ/AMPK signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu Y, Tian Y, Cai W, Guo Y, Xue C, Wang J. DHA/EPA-enriched phosphatidylcholine suppresses tumor growth and metastasis via activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in lewis lung cancer mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(2):676–85. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Słowikowski BK, Drzewiecka H, Malesza M, Mądry I, Sterzyńska K. The influence of conjugated linoleic acid on the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ and selected apoptotic genes in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cell Biochem. 2020;466(1–2):65–82. 10.1007/s11010-020-03689-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ge LN, Yan L, Li C, Cheng K. Bavachinin exhibits antitumor activity against non-small cell lung cancer by targeting PPARγ. Mol Med Rep. 2019;20(3):2805–11. 10.3892/mmr.2019.10485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim TW, Hong DW, Hong SH. CB13, a novel PPARγ ligand, overcomes radio-resistance via ROS generation and ER stress in human non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(10):848. 10.1038/s41419-020-03065-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Muzio G, Barrera G, Pizzimenti S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and oxidative stress in physiological conditions and in cancer. Antioxidants. 2021. 10.3390/antiox10111734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Phan ANH, Vo VTA, Hua TNM, Kim MK, Jo SY, Choi JW, et al. PPARγ sumoylation-mediated lipid accumulation in lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;47:82491–505. 10.18632/oncotarget.19700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hua TNM, Kim MK, Vo VTA, Choi JW, Choi JH, Kim HW, et al. Inhibition of oncogenic Src induces FABP4-mediated lipolysis via PPARγ activation exerting cancer growth suppression. EBioMedicine. 2019. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lamas Bervejillo M, Bonanata J, Franchini GR, Richeri A, Marqués JM, Freeman BA, et al. A FABP4-PPARγ signaling axis regulates human monocyte responses to electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkenes. Redox Biol. 2020. 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ballav S, Biswas B, Sahu VK, Ranjan A, Basu S. PPAR-γ partial agonists in disease-fate decision with special reference to cancer. Cells. 2022. 10.3390/cells11203215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.