Abstract

During entomopathogenic fungal surveys conducted in Thailand, 15 specimens tentatively classified under Akanthomyces sensu lato were identified. To gain a comprehensive understanding of their taxonomy, molecular phylogenies using combined LSU, TEF1, RPB1, and RPB2 sequence data, together with morphological examination of several Akanthomyces spp. from previous studies were conducted. The analyses revealed distinct clades representing independent lineages within the Cordycipitaceae. These clades were further characterized by different asexual morph types and the respective hosts they parasitize. In this context, we resurrected the genus Lecanicillium to accommodate 12 known species previously classified under Akanthomyces sensu lato, found on diverse hosts. We propose four new genera – Corniculantispora, Corpulentispora, Zarea, and Zouia – from species previously identified as Lecanicillium. Notably, certain Akanthomyces species associated with spiders and parasitic on Ophiocordyceps sinensis were reclassified into the new genera Arachnidicola and Kanoksria, respectively. Moreover, we introduce four novel species in Akanthomyces sensu stricto found across a diverse range of moth families: Ak. buriramensis, Ak. fusiformis, Ak. niveus, and Ak. phariformis. Additionally, we provide descriptions and illustrations of the sexual morph linked to Ak. laosensis and Ak. pseudonoctuidarum, along with a second type of synnemata seen in Ak. noctuidarum and Ak. pseudonoctuidarum. To assist with their identification, keys to the genera Akanthomyces, Arachnidicola, and Lecanicillium are provided, but should not be used to replace molecular identification.

Citation: Khonsanit A, Thanakitpipattana D, Mongkolsamrit S, Kobmoo N, Phosrithong N, Samson RA, Crous PW, Luangsa-ard JJ (2024). A phylogenetic assessment of Akanthomyces sensu lato in Cordycipitaceae (Hypocreales, Sordariomycetes): introduction of new genera, and the resurrection of Lecanicillium. Fungal Systematics and Evolution 14: 271–305. doi: 10.3114/fuse.2024.14.17

Keywords: Cordycipitaceae, molecular phylogeny, new taxa, taxonomy

INTRODUCTION

Cordycipitaceae (Hypocreales, Sordariomycetes, Ascomycota) was reintroduced by Sung et al. (2007), primarily relying on the phylogenetic placement of Cordyceps militaris, the designated type species. This family contains species producing stalked, erect, fleshy, and vividly coloured stromata. Nevertheless, certain species exhibit reduced stipes, giving rise to subiculate, pallid to cream, or white stromata on their insect hosts (Sung et al. 2007, Kepler et al. 2017, Wang et al. 2020, Mongkolsamrit et al. 2022). Species within the Cordycipitaceae are commonly found on various insect hosts, displaying diverse morphological characteristics (Wang et al. 2020). Recent investigations on the phylogenetic relationships and morphological differences within Cordycipitaceae have led to the establishment of a new mycoparasitic genus Niveomyces (Araújo et al. 2022), three additional genera on spiders, Jenniferia, Parahevansia, and Polystromomyces (Mongkolsamrit et al. 2022), the introduction of a new genus Neohyperdermium on scale insects (Thanakitpipattana et al. 2022), as well as Gamszarella from soil, basidiomycete sporocarps and dead insects (Arnold & Castañeda Ruíz 1987, Zhang et al. 2020, Crous et al. 2023). In addition to these newly established genera, 17 known genera have been documented, including Akanthomyces, Ascopolyporus, Beauveria, Blackwellomyces, Cordyceps, Engyodontium, Flavocillium, Gibellula, Hevansia, Lecanicillium, Leptobacillium, Liangia, Neotorrubiella, Parengyodontium, Pseudogibellula, Samsoniella, and Simplicillium. The asexual morphs within Cordycipitaceae are diverse and have been assigned different generic names, such as Acremonium, Akanthomyces, Beauveria, Engyodontium, Gibellula, Isaria, Lecanicillium, Pseudolecanicillium, Simplicillium, and Verticillium (Zare & Gams 2001, Kuephadungphan et al. 2019, 2020, 2022, Wang et al. 2020, Alvez et al. 2022).

The genus Akanthomyces was initially established by Lebert (1858), featuring the type species A. aculeatus discovered on moths in France. Akanthomyces aculeatus is characterized by its white to cream cylindrical synnemata, covered by a hymenium-like layer of phialides that produce catenulate, short, or long chains of conidia. The phialides are hyaline, cylindrical or flask-shaped, gradually or abruptly tapering to a more or less distinct neck (Mains 1950). Currently 42 species are classified within Akanthomyces and despite the diversity within the genus, the morphological characteristics among species significantly overlap, posing challenges for accurate morphological identification to species level (Manfrino et al. 2022). Some Akanthomyces species were described with an asexual morph resembling Isaria, including Akanthomyces bashanensis, Ak. beibeiensis, Ak. araneicola, Ak. araneogenum, Ak. kanyawimiae, Ak. kunmingensis, A. neoaraneogenus, Ak. subaraneicola, Ak. sulphureus, and Ak. waltergamsii (Chen et al. 2017, 2019a, Mongkolsamrit et al. 2018, Wang et al. 2024). Others were identified with a lecanicillium-like morph, such as Ak. lepidopterorum, Ak. noctuidarum, Ak. thailandicus, Ak. tiankengensis, and Ak. tortricidarum (Mongkolsamrit et al. 2018, Aini et al. 2020, Chen et al. 2020a, Chen et al. 2022), or a verticillium-like morph, namely Ak. neocoleopterorum (Chen et al. 2020b).

Akanthomyces species are known to infect a variety of hosts, including moths, scale insects, spiders, and can also be found in soil (Kepler et al. 2017, Chen et al. 2018, Shrestha et al. 2019, Aini et al. 2020). Seven recognized Akanthomyces species were found occurring on moths, viz. Ak. aculeatus (Lebert 1858), Ak. tuberculatus (Samson & Evans 1974), Ak. noctuidarum, Ak. pyralidarum, and Ak. tortricidarum (Aini et al. 2020), as well as Ak. laosensis and Ak. pseudonoctuidarum (Wang et al. 2024). In addition, five Akanthomyces species were identified parasitizing spiders: Ak. aranearum, Ak. kanyawimiae, Ak. sulphureus, Ak. thailandicus, and Ak. waltergamsii (Mains 1950, Mongkolsamrit et al. 2018). Furthermore, through phylogenetic analyses and morphological observations, some species were reclassified into the genera Hevansia (H. arachnophila, H. longispora, H. novoguineensis, H. ovalongata, H. websteri) and Jenniferia (J. cinerea) (Kepler et al. 2017, Mongkolsamrit et al. 2022).

The genera Lecanicillium and Simplicillium were introduced for verticillium-like taxa by Gams & Zare (2001). In Lecanicillium sensu lato, the species are phylogenetically dispersed within Cordycipitaceae, failing to form a single monophyletic clade (Sukarno et al. 2009), and includes more than 30 species (Manfrino et al. 2022). The morphology of Lecanicillium consists of discrete, aculeate phialides tapering to a narrow tip, generating short to long ellipsoidal- to falcate-shaped conidia with pointed ends, which cluster into slimy heads or fascicles (Gams & Zare 2001). Kepler et al. (2017) highlighted that the sexual species Cordyceps confragosa (Torrubiella confragosa) is associated with L. lecanii, the type species of Lecanicillium. This species has a cosmopolitan distribution, being found on a diverse range of insects (Kobe & Leal 2005).

Nevertheless, Kepler et al. (2017) considered the genus Lecanicillium as synonymous with Akanthomyces. Their molecular phylogenetic investigation, using five nuclear loci (SSU, LSU, TEF1, RPB1, and RPB2), revealed that the type species, L. lecanii, was nested within Akanthomyces, thus granting priority to Akanthomyces over Lecanicillium. Consequently, Kepler et al. (2017) proposed the suppression of Lecanicillium along with Isaria, Torrubiella, and other lesser-known names in favour of Akanthomyces. Lecanicillium was therefore considered synonymous with Akanthomyces, and species such as L. attenuatum, L. lecanii, L. longisporum, L. muscarium, L. pissodis, L. sabanense, and L. uredinophilum were transferred into Akanthomyces. Some species from Lecanicillium s.l. were also reassigned to Flavocillium, Gamszarea (Ga.) and Gamszarella (Gam.) based on molecular data, including F. primulinum, F. subprimulinum, Ga. kalimantanensis, Ga. restricta, Ga. testudinea, and Ga. wallacei, Gam. antillana, Gam. magnispora (Kepler et al. 2017, Shrestha et al. 2019, Wang et al. 2020, Zhang et al. 2020, Manfrino et al. 2022, Crous et al. 2023). However, the phylogeny of several species within Lecanicillium s.l. remain unresolved, e.g. L. aphanocladii, L. aranearum, L. cauligalbarum, L. coprophilum, L. dimorphum, L. evansii, L. flavidum, L. fungicola, L. nodulosum, L. psalliotae and L. saksenae (Zare & Gams 2001, Zare & Gams 2008, Sukarno et al. 2009, Zhou et al. 2018, Su et al. 2019).

During a survey of entomopathogenic fungi in Thailand, numerous moth cadavers consistently showed infection by Akanthomyces. The objectives of this study are to clarify the phylogenetic relationships among species in Akanthomyces sensu lato and Lecanicillium sensu lato by examining both their morphology and DNA phylogeny and to offer insights into which functional characteristics could be crucial and beneficial for phenotype-based identification.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates

Samples of entomopathogenic fungi on moths were collected throughout Thailand from 2002 to 2016. Stems of living plants, underside and upper side of leaves and the leaf litter were surveyed for dead moths infected with fungi. The collected specimens were placed in plastic boxes (3 × 6 cm or 6 × 10 cm) and returned to the laboratory for further examination. Fungal isolation was done from both asexual and sexual morphs found on the specimens; for asexual morphs, conidia sporulating from synnemata were streaked onto potato dextrose agar (PDA: 200 g potato, 20 g dextrose, 15 g agar, in 1 L distilled water) plates. After 24 to 48 h, plates were checked for contamination and cultures transferred to new PDA plates. For sexual morphs, the specimen was fastened on the underside of the lid of the Petri plate over the PDA and incubated overnight in a moist chamber to collect discharged ascospores which were then transferred to new PDA plates. All pure cultures were deposited in the BIOTEC culture collection (BCC). Fungal specimens were dried in a food dehydrator and deposited in the BIOTEC Bangkok Herbarium (BBH), Thailand Science Park, Pathum Thani Province, Thailand.

Molecular phylogenetic analyses

Genomic DNA was extracted from fungal cultures following a modified cetyltrimethyl-ammonium bromide (CTAB) method as described in Doyle & Doyle (1987). The DNA of the large subunit of the nuclear ribosomal DNA (LSU), partial regions of the translation elongation factor-1α gene (TEF1), and the largest and second largest subunits of the RNA polymerase II (RPB1, RPB2) were amplified and sequenced. The PCR primers used to amplify these markers are LROR and LR5 for LSU (Vilgalys & Hester 1990, Rehner & Samuels 1994), EF-983F and EF-2218R for TEF1 (Rehner & Buckley 2005), CRPB1 and RPB1-Cr for RPB1 (Castlebury et al. 2004), and fRPB2-5F2 and fRPB2-7cR for RPB2 (Liu et al. 1999, O’Donnell et al. 2007). Thermocycler conditions for PCR amplifications followed previously described protocols by Sung et al. (2007). The PCR products were purified and then sequenced using the same primers used for PCR amplification.

DNA sequences were assembled and manually edited using BioEdit v. 7.2.5 (Hall 1999). The alignment data were edited with MUSCLE v. 3.6 software (Edgar 2004). The combined dataset was analysed by maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI). Maximum likelihood was performed with RAxML-HPC2 on XSEDE v. 8.2.12 in CIPRES Science Gateway portal with 1 000 bootstrap replicates (Stamatakis 2014). Bayesian analysis was performed using MrBayes on XSEDE v. 3.2.7a (Ronquist et al. 2012), with the best fit model SYM+G model. Four chains for the MCMC variant were run with 5 000 000 generations, with sampling a tree every 1 000 generations and a burn in of 10 % from the total run.

Morphology

Photos of specimens were taken using a digital Nikon D5100 camera and Olympus DP70 Digital Camera installed on an Olympus SZX12 dissecting microscope. The micromorphological characters were photographed using a DP70 digital camera installed on an Olympus BX51 compound microscope. Morphological examination of macroscopic and microscopic features was done on microscope slides using lactophenol cotton blue. For the asexual morph, synnemata with phialides and conidia were observed from host tissue. For the sexual morph, asci and ascospores were removed from perithecia. For colony characteristics on the culture media and microscopic measurements of phialides and conidia, strains were grown on PDA and oatmeal agar (OA, Difco) in white light/dark cycles in the laboratory, after 30 d of incubation at 25 °C. The size and the shape of these morphological characters were measured with a minimum sampling size of 5−20 for perithecia and ca. 50 for phialides, conidia, asci, asci caps, part-spores to obtain an average ± standard deviation with absolute minima and maxima in parentheses. The 6th Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) colour chart was used to describe the colours of fresh specimens and cultures (RHS Media 2015).

RESULTS

Molecular phylogenetic analyses

Sequences from a total of 166 strains in Cordycipitaceae were incorporated into this study, which included newly acquired data from 15 specimens of Akanthomyces species on moths from our collections (Table 1). Trichoderma deliquescens and T. stercorarium served as the outgroup. A final alignment of 3 541 bp from the concatenated four-loci (LSU = 892 bp, TEF1 = 1 029 bp, RPB1 = 722 bp, and RPB2 = 898 bp) was used for the phylogenetic analyses. Our results reveal that while Akanthomyces sensu lato forms a strongly supported and distinct monophyletic clade [88 % ML bootstrap (MLBS) and 0.85 BI posterior probability (BIPP)] (see Fig. 1A), it can be further divided into four monophyletic subclades with distinctive host preferences and morphologies, tentatively identified as Akanthomyces, Arachnidicola, Lecanicillium clades, and Kanoksria.

Table 1.

List of taxa included in the phylogenetic analyses and their GenBank accession numbers. Newly generated sequences in this study are marked in bold font. Ex-type strains are indicated with T.

Fig. 1A, B.

RAxML tree of Akanthomyces, Arachnidicola, Lecanicillium and related genera in the Cordycipitaceae from a combined LSU, TEF1, RPB1 and RPB2 dataset. Number on the nodes are ML bootstrap values/Bayesian posterior probability above 70 %. Bold lines mean support for the three analyses were 100 %. In yellow boxes are species with lecanicillium-like asexual morphs. T = ex-type culture.

The Arachnidicola clade (A) represents a well-supported group (MLBS = 70 %, BIPP = 0.85), consisting exclusively of species found on spiders. These include Ar. sulphurea, Ar. waltergamsii, Ar. kunmingensis, Ar. thailandica, Ar. subaraneicola, Ar. araneicola, Ar. neoaraneogenus, Ar. bashanensis, Ar. beibeiensis, Ar. tiankengensis, and Ar. kanyawimiae. Most of these species exhibit an isaria-like asexual morph, apart from Ar. tiankengensis, which produces a lecanicillium-like asexual morph (Chen et al. 2022). Consequently, we propose transferring all known species in Clade A to the new genus Arachnidicola. It is noteworthy that in our analyses, Ar. coccidioperitheciatus NHJ06709 (Johnson et al. 2009) and Ar. farinosa CBS 541.81 (Kepler et al. 2017) were nested within Ar. kanyawimiae, indicating they are conspecific with Ar. kanyawimiae.

The Lecanicillium clade (B) forms a well-supported monophyletic group (BIPP = 0.79), comprising species that were originally classified in Lecanicillium but were transferred to Akanthomyces sensu Kepler et al. (2017) such as Ak. attenuatus, Ak. lecanii, Ak. dipterigenus, Ak. muscarius, Ak. sabanensis as well as Ak. neoaraneogenus (Shrestha et al. 2019), Ak. lepidopterorum, Ak. pissodis (Chen et al. 2020a), Ak. neocoleopterorum (Chen et al. 2020b), Ak. araneosus (Chen et al. 2022) and Ak. uredinophilus (Manfrino et al. 2022). Given that the type species of Lecanicillium, L. lecanii, is nested within this well-supported clade, we propose the resurrection of the genus Lecanicillium, and suggest transferring all species in this clade to Lecanicillium. Species within clade B exhibit both lecanicilliumlike and verticillium-like asexual morphs, and they have been found on various substrates, including a wide range of insects, spiders, decaying leaves, leaf litter, and mushrooms.

The Akanthomyces clade (C) is strongly supported (MLBS = 98 %, BIPP = 0.85) and distinctly separates from the Arachnidicola (A) and Lecanicillium (B) clades. Within clade C, we identify four new species: Akanthomyces phariformis, Ak. fusiformis, Ak. niveus, Ak. buriramensis, and two new records, Ak. laosensis and Ak. pseudonoctuidarum. Additionally, three Akanthomyces species previously described by Aini et al. (2020), including the type species Ak. aculeatus, are also part of this clade. All species within this clade were observed on adult moths and predominantly exhibit an akanthomyces-like asexual morph. Notably, Ak. niveus and Ak. phariformis did not show evidence of producing an asexual morph. Consequently, this clade can be designated as Akanthomyces sensu stricto.

Basal to the previously mentioned clades A–C is clade D, which exclusively includes Ak. zaquensis strains (Wang et al. 2023). This clade forms a distinct, well-supported group (BIPP = 1.00), separate from the Akanthomyces clade. As a result, it is proposed that this clade does not fall under the classification of Akanthomyces and should be designated as the new genus Kanoksria.

Significantly, Fig. 1 encompasses nearly all species within Lecanicillium. However, some species are represented solely by ITS sequences due to the absence of multigene data, preventing their inclusion in the analysis. The resulting topology in Fig. 1 aligns with earlier phylogenetic studies in Cordycipitaceae. The phylogenetic tree exposes the non-monophyletic nature of the Lecanicillium lineage, revealing it as a polyphyletic genus distributed across various clades within the Cordycipitaceae (Zare & Gams 2008, Wang et al. 2020, Zhou et al. 2022). Certain species, as illustrated in Fig. 1A, B, were transferred to other genera such as Akanthomyces, Flavocillium (clade 3), Gamszarea (clade 9) and Gamszarella (clade 6) (Kepler et al. 2017, Wang et al. 2020, Zhang et al. 2020, Zhou et al. 2022, Crous et al. 2023). In this study, we suggest transferring Lecanicillium huhutii and L. tenuipes from clade 8 to the genus Engyodontium. Additionally, we propose new genera for clades 2, 4, 5 and 7, namely Corniculantispora, Zouia, Zarea, and Corpulentispora. These proposals are moderately to strongly supported based on multilocus phylogeny. Single-locus phylogenetic analyses did not consistently recover these clades. Among the loci, only RPB1 provided all three monophyletic clades with robust support [MLBS: Clade A = 96 %, Clade B = 95 %, Clade C = 100 %], while RPB2 only recapitulated Clade A and Clade C with complete support [MLBS = 100 %], excluding Clade B, which was divided into a clade containing Lecanicillium lecanii + L. sabanense segregating from the rest of Lecanicillium (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Taxonomy

Akanthomyces buriramensis Mongkols., Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, sp. nov. MycoBank MB 842450. Fig. 2.

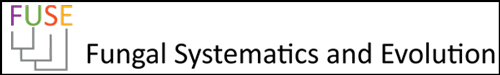

Fig. 2.

Akanthomyces buriramensis (A, C, D, G–N. BBH30240; E, F. BBH30245). A, B. Fungus on adult moths. C, D. Perithecia. E. Asci. F. Asci and ascicaps. G. Ascospores. H. Part-spores. I. Phialides and conidia. J. Conidia. K. Colony obverse on OA in 20 d. L. Colony reverse on OA in 20 d. M. Colony obverse on PDA in 20 d. N. Colony reverse on PDA in 20 d. Scale bars: A, B, K–N = 10 mm; C = 1 mm; D = 100 μm; E–G = 20 μm; H, I, F–L = 10 μm; J = 5 μm.

Etymology: The name is derived from the locality where the specimens were found, Buri Ram Province, Thailand.

Typus: Thailand, Buri Ram Province, Non Din Daeng District, Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary, Pong Kao nature trail, 14°17’46”N, 102°44’11”E, on adult moth (Noctuidae), 11 Dec. 2010, A. Khonsanit, A. Saksrikrom, B. Saracam, K. Tasanathai, K. Sansatchanon, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Noisripoom (holotype BBH30240 preserved in a metabolically inactive state; ex-holotype culture BCC47939). GenBank accession numbers: ON008545 (LSU), ON013548 (TEF1), ON013563 (RPB1).

Asexual morph: Synnemata scattered, arising from the moths’ body, filiform, solitary, occasionally curved, white, pale yellow (18C), light orange yellow (22D), up to 10 mm long. Conidiophores densely compacted into a layer along the synnemata, cylindrical, monophialidic or polyphialidic. Phialides smooth-walled, ampulliform, obpyriform, lageniform, hyaline, (4–)4.5–7(–10) × 3–4 μm. Conidia 1-celled, ellipsoid, fusoid, obovoid, smooth-walled, hyaline, 3–5 × 1–2 μm. Sexual morph: Specimens found on adult moths (Noctuidae, Notodontidae), on the stem of living bamboo twigs and underside of dicotyledonous leaves. Perithecia superficial, crowded in the middle synnemata, mostly on one side of the synnema, ovoid, strong orange yellow (N163B–D), strong yellowish brown (N199D), moderate yellowish brown (N199C), (500–)560–635(–750) × (300–)320– 380(–400) μm. Asci cylindrical, hyaline, 250–450 × 3.5–4 μm. Asci-caps hemispherical 3 × 4–5 μm. Ascospores filiform, multiseptate, breaking into part-spores, hyaline, up to 250 μm long. Part-spores cylindrical, hyaline, (4–)6–14.5 × 0.5–1 μm.

Colony characteristics: Colony obverse on OA compact, raised to the agar surface, entire margin, attaining a diam of 35 mm in 20 d, white. Colony reverse on OA strong yellow (153D). Colony obverse on PDA compact, raised to the agar surface, entire margin, attaining a diam of 35 mm in 20 d, white. Colony reverse on PDA moderate yellow (160D). Conidia and reproductive structures are not observed on both media after 30 d of incubation at 25 °C.

Additional specimens examined: Thailand, Buri Ram Province, Non Din Daeng District, Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary, Headquarter nature trail, 14°17’46”N, 102°44’11”E, on adult moth (Noctuidae), 30 Nov. 2010, A. Khonsanit, A. Saksrikrom, B. Saracam, K. Tasanathai, K. Sansatchanon, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Noisripoom (BBH30105; BBH30106; BBH30107:BCC45157:BCC45158; BBH30108); ibid., Pa Takong nature trail, 14°17’46”N, 102°44’11”E, on adult moth, 10 Dec. 2010, A. Khonsanit, A. Saksrikrom, B. Saracam, K. Tasanathai, K. Sansatchanon, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Noisripoom (BBH30170:BCC45165); ibid., (BBH30119:BCC45166; BBH30249); ibid., Pong Kao nature trail, 14°17’46”N, 102°44’11”E, on adult moth (Notodontidae), 11 Dec. 2010, A. Khonsanit, A. Saksrikrom, B. Saracam, K. Tasanathai, K. Sansatchanon, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Noisripoom (BBH30239:BCC47938; BBH30240).

Notes: Both the asexual and sexual morph of Ak. buriramensis can be found on the same specimen. Phylogenetically, Ak. buriramensis is closely related to Ak. noctuidarum (Fig. 1A). Both species are phylogenetically well-supported and Ak. buriramensis is found in Buri Ram Province, lower northeastern Thailand, while Ak. noctuidarum strains are found throughout Thailand. Morphologically, Ak. buriramensis differs from other related species in producing crowded superficial perithecia laterally at the midsection of the short synnemata (Fig. 2C).

Akanthomyces fusiformis Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, sp. nov. MycoBank MB 842452. Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Akanthomyces fusiformis (BBH27326). A, B. Fungus on adult moths. C. Perithecia. D. Asci. E. Asci-caps. F. Part-spores. G, H. Phialides and conidia on host. I. Conidia on host. J. Colony obverse on OA in 20 d. K. Colony reverse on OA in 20 d. L. Colony obverse on PDA in 20 d. M. Colony reverse on PDA in 20 d. Scale bars: A, B = 1 mm; C, D = 100 μm; E−I = 10 μm; J−M = 10 mm.

Etymology: The name is derived from the fusiform shape of its conidia.

Typus: Thailand, Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Pak Chong District, Khao Yai National Park, Mo Sing To nature trail, 14°26’23”N, 101°22’20”E, on adult moth (Pyralidae), 10 Dec. 2009, A. Khonsanit, K. Tasanathai, M. Sudhadham, P. Srikitikulchai, R. Ridkaew, S. Mongkolsamrit & T. Chohmee (holotype BBH27326 preserved in a metabolically inactive state; ex-holotype strain BCC40756). GenBank accession numbers: ON008549 (LSU), ON0013552 (TEF1), ON0013567 (RPB1), ON0013576 (RPB2).

Asexual morph: White mycelium covering the body of the host. Conidiophores mononematous, smooth-walled, hyaline, with single phialide. Phialides elongate-ampulliform, smooth-walled, hyaline, (4–)6–15(–27) × 1–3 μm. Conidia 1-celled, narrowly fusiform, smooth-walled, hyaline, (4–)7–10(–13) × 1–2 μm. Sexual morph: Specimens found on adult moths (Pyralidae), on the underside of dicotyledonous leaves, white mycelium covered on the host body. Perithecia superficial, scattered on the host body, ovoid, strong orange (26A), light orange yellow (19A), light yellowish pink (19B), 580–640 × 170–210 μm. Asci cylindrical, hyaline, (302–)361–420(–450) × 4–5 μm. Asci-caps abrupt cone-shaped, hyaline, 4.5–5.5 × 4–5 μm. Ascospores filiform, multi-septate, breaking into part-spores, hyaline. Part-spores cylindrical, hyaline, (5–)7–13(–18) × 1 μm.

Colony characteristics: Colony obverse on OA compact, wrinkled, raised to the agar surface, entire margin, attaining a diam of 31– 40 mm in 20 d, white to pale yellow green (195D). Colony reverse on OA moderate yellow (160A). Colony obverse on PDA cottony, convex to the agar surface, entire margin, attaining a diam of 30–32 mm in 20 d, white. Colony reverse on PDA moderate yellow (160A), pale yellow (160D) along the margin. Conidia and reproductive structures are not observed on both media after 30 d of incubation at 25 °C.

Notes: There is only one specimen of A. fusiformis found on an adult moth (Pyralidae) from Khao Yai National Park, Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Thailand. Both asexual and sexual morph can be seen on the same specimen. However, the asexual morph of Ak. fusiformis does not produce synnemata on its host but produces the phialides scattered on white mycelium covering the host body and wings. Phylogenetically, Ak. fusiformis is closely related to Ak. pyralidarum (Fig. 1A). Morphologically, Ak. fusiformis differs from Ak. pyralidarum in producing superficial perithecia, while Ak. pyralidarum produces crowded superficial perithecia at the tip of synnemata (Aini et al. 2020). Akanthomyces fusiformis differs from other related species by producing cone-shaped asci-caps (Fig. 3E), and long narrowly fusiform conidia (Fig. 3I), see Table 2.

Table 2.

Morphological comparisons between an asexual morph of Akanthomyces species on moths.

| Species | Synnemata | Phialides (μm) | Conidia (μm) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ak. aculeatus | Yellowish, cylindrical, narrowing upward, 1–8 mm long, 0.1–0.5 mm wide | Subcylindric, narrowly ellipsoidal, 6–16 × 2.5–4 | Ellipsoidal, obovoid, 3–6 × 2–3 | Lebert (1858) |

| Ak. buriramensis | Scattered, arising from the moths body, white, yellow to orange, up to 10 mm long | Ampulliform, obpyriform, lageniform, 4–10 × 3–4 | Ellipsoid, fusiform, obovoid, 3–5 × 1–2 | This study |

| Ak. fusiformis | — | Elongate-ampulliform, 4–27 × 1–3 | Narrowly fusiform, 4–13 × 1–2 | This study |

| Ak. laosensis | Scattered, arising different parts of the host body, white, 3−20 mm long | Ampulliform, lageniform, obpyriform, 4–10 × 2–3 | Fusiform elliptical, elliptical, 3–6 × 1.5–2 | This study |

| Ak. noctuidarum | Long synnema arising from the thorax of the hosts, filiform, simple, solitary, occasionally curved, white, up to 30 mm long | Cylindrical with papillate end, 4−9 × 2−3 | Cylindrical with rounded end, occasionally elliptical and fusiform, 3−6 × 1−2 | Aini et al. (2020), |

| Short synnemata scattered, arising different parts of the host body and wing veins, simple, solitary, cylindrical with rounded end, white | Cylindrical with papillate end, 4−12 × 2−4 | Cylindrical with rounded end, occasionally elliptical and fusiform, 4−6 × 1−2 | This study | |

| Ak. pseudonoctuidarum | Long synnemata, filiform, occasionally curved | Ampulliform, obclavate, obpyriform, lageniform, 6–13 × 2−4 | Obovoid, 3–6 × 1.5–2 | This study |

| Short synnemata, filiform, occasionally curved, ca. 1–30 mm long | Ampulliform, obclavate, obpyriform, lageniform, 4–17 × 2–4 | Obovoid, 3–5 × 1.5–2.5 | ||

| Ak. tortricidarum | Long synnemata, cylindrical to clavate with acute or blunt end, up to 5 mm long and wide ca. 120–150 μm. | Cylindrical to ellipsoidal with papillate end, 5–10 × 1.8–3 | Fusoid, 2–3.2 × 1–2 | Aini et al. (2020) |

| Short synnemata, cylindrical with subglobose or oblong at the end, 197–300 × 15–40 μm, with diameter of the tip 43–75 μm. | Cylindrical to ellipsoidal with papillate end, 5–10 × 1.8–3 | Fusoid, 1–3 × 1–2 | ||

| Ak. tuberculatus | Scattered, arising from different part of the host body, white to creamish, cylindrical, clavate, 1–6 mm long, 50–300 mm wide. | Cylindrical, 7–10.5 × 2.7–3.5 | Cylindrical, narrowly fusiform, 4.5–6 × 1.2–1.5 | Samson & Evans (1974) |

Akanthomyces niveus Khons., Thanaktip. & Luangsa-ard, sp. nov. MycoBank MB 842453. Fig. 4.

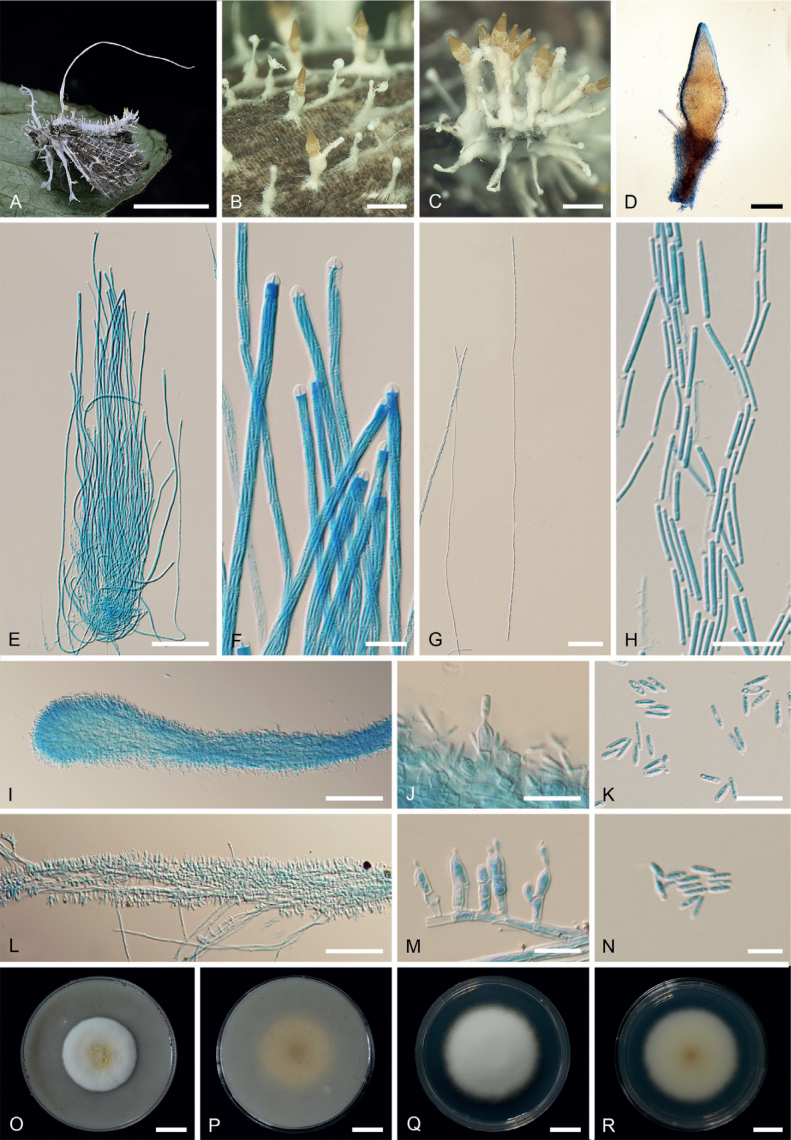

Fig. 4.

Akanthomyces niveus (A. BBH27294; B–K. BBH40778). A, B. Fungus on adult moths. C, D. Perithecia. E. Asci. F. Asci-caps. G. Part-spores. H. Colony obverse on OA in 20 d. I. Colony reverse on OA in 20 d. J. Colony obverse on PDA in 20 d. K. Colony reverse on PDA in 20 d. Scale bars: A = 1 mm; B = 5 mm; C = 500 μm; D = 100 μm; E = 200 μm; F = 20 μm, G = 10 μm; H−K = 10 mm.

Etymology: In Latin “nivea” means white, refers to the colour of the insect hosts of this species.

Typus: Thailand, Chiang Mai Province, Kanlayaniwatthana District, Ban Huai Baba community forest nature trail, 18°59’13”N, 98°17’06”E, on adult moth (Lepidoptera), 25 Nov. 2015, D. Thanakitpipattana, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, R. Promharn, S. Mongkolsamrit, S. Wongkanoun & W. Noisripoom (holotype BBH40778 preserved in a metabolically inactive state; ex-holotype strain BCC79887). GenBank accession numbers: ON008551 (LSU), ON0013554 (TEF1), ON0013578 (RPB2).

Asexual morph: Unknown. Sexual morph: Specimens found on adult moths (Lepidoptera) on the stem of living plants and underside of dicotyledonous leaves, thin whitish mycelium covering the host body. Perithecia superficial, scattered on the host body, ovoid, strong orange (26A), 400–530 × 180–200 μm. Asci cylindrical, hyaline, 273–568 × 4–5 μm. Asci-caps umbonate, hyaline, 2.5–3.5 × 4–5 μm. Ascospores filiform, multi-septate, breaking into part-spores, hyaline. Part-spores cylindrical, hyaline, (5–)6–14(–22) × 0.5–1 μm.

Colony characteristics: Colony obverse on OA compact, raised to the agar surface, cottony, entire margin, attaining a diam of 29–31 mm in 20 d, white, occasionally light yellow (14D) in the middle. Colony reverse on OA pale yellow (11C—11D). Colony obverse on PDA closely appressed to the agar surface, compact, velvet, entire margin, attaining a diam of 29–32 mm in 20 d, white, occasionally pale greenish yellow (2D) in the middle. Colony reverse on PDA moderate orange yellow (164C) and pale yellow (164D) in the middle, pale yellow (11D). Conidia and reproductive structures are not observed on both media after 30 d of incubation at 25 °C.

Additional specimen examined: Thailand, Phetchabun Province, Nam Nao District, Nam Nao National Park, Headquarters nature trail, 16°44’25”N, 101°34’24”E, on adult moth (Pyralidae), 24 Nov. 2009, A. Khonsanit, K. Tasanathai & T. Chohmee (BBH27294:BCC40747).

Notes: Phylogenetically, Ak. niveus is closely related to Ak. tortricidarum (Aini et al. 2020). However, Ak. niveus is only known from its sexual morph, while Ak. tortricidarum is known from its asexual morph. Akanthomyces niveus differs from other related species in producing whitish mycelium covering the host body and wings (Fig. 4A, B).

Akanthomyces phariformis Khons., Thanaktip. & Luangsa-ard, sp. nov. MycoBank MB 842455. Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Akanthomyces phariformis (BBH30086). A. Fungus on adult moth. B, C. Perithecia. D. Asci. E. Part-spores. F. Colony obverse on OA in 20 d. G. Colony reverse on OA in 20 d. H. Colony obverse on PDA in 20 d. I. Colony reverse on PDA in 20 d. Scale bars: A = 5 mm; B = 1 mm; C = 100 μm; D = 20 μm; E = 10 μm; F−I = 10 mm.

Etymology: In Latin “phari” means lighthouse, referring to the form of crowded perithecia at the apex of synnemata, like a lighthouse.

Typus: Thailand, Tak Province, Umphang District, Umphang Wildlife Sanctuary, Thi Lo Su Waterfall nature trail, 15°55’36”N, 98°45’12”E, on adult of Lemyra sp. (Erebidae), 24 Nov. 2010, A. Khonsanit, K. Sansatchanon, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai & W. Noisripoom (holotype BBH30086 preserved in a metabolically inactive state; exholotype strain BCC45148). GenBank accession numbers: ON008556 (LSU), ON00135529 (TEF1), ON0013583 (RPB2).

Asexual morph: Unknown. Sexual morph: Specimens found on adult of Lemyra sp. (Erebidae: Lepidoptera), on the upper side of dicotyledonous leaves and the leaf litter, thin whitish mycelium covering the host body. Perithecia superficial, crowded at the apex of synnemata, ovoid, light olive brown (199B), 360–550 × 200–260 μm. Asci cylindrical, hyaline, 400–470 × 5 μm. Ascospores filiform, multi-septate, breaking into part-spores, hyaline. Part-spores cylindrical, hyaline, (3–)4–8(–11) × 0.5–1 μm.

Colony characteristics: Colony obverse on OA flat, closely appressed to the agar surface, velvety, entire margin, attaining a diam of 37–42 mm in 20 d, white. Colony reverse on OA pale yellow (162D). Colony obverse on PDA flat, closely appressed to the agar surface, velvety, entire margin, attaining a diam of 36– 41 mm in 20 d, white, pale yellow (160D), pale greenish yellow (160C). Colony reverse on PDA moderate yellow (160A) in the middle, and bluish white (N155A) along the margin. Conidia and reproductive structures are not observed on both media after 30 d of incubation at 25 °C.

Additional specimen examined: Thailand, Chiang Mai Province, Kanlayaniwatthana District, Huai Ban Rang Fish Sanctuary nature trail, 18°59’14”N, 98°17’10”E, on adult of Othreis sp. (Noctuidae), 3 Nov. 2014, A. Khonsanit, D. Thanakitpipattana, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Wongkanoun & W. Noisripoom (BBH40632:BCC76537).

Notes: Our Akanthomyces phariformis collections produced only the sexual morph. Phylogenetically, Ak. phariformis is closely related to Ak. laosensis (Fig. 1A). However, both specimens of Ak. phariformis were found only from northern Thailand while Ak. laosensis was found only from southern Thailand. Morphologically, Ak. phariformis differs from Ak. laosensis in producing crowded superficial perithecia at the apex of synnemata (Fig. 5A, B) while Ak. laosensis produces superficial perithecia laterally at the midsection of the synnemata (Fig. 5A–D).

Akanthomyces laosensis H. Yu bis & Y. Wang, MycoKeys 101: 123. 2024. Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Akanthomyces laosensis (A, D, E, H–T. BBH31282; B, F, G. BBH32436; C. BBH37641). A–C. Fungus on adult moths. D, E. Perithecia. F. Asci and asci-caps. G. Ascospores. H. Synnema. I. Phialides and conidia on host. J. Conidia on host.. K. Colony obverse on OA in 20 d. L. Colony reverse on OA in 20 d. M, N. Phialides and conidia on OA. O. Conidia on OA. P. Colony obverse on PDA in 20 d. Q. Colony reverse on PDA in 20 d. R, S. Phialides and conidia on PDA. T. Conidia on PDA. Scale bars: A−C = 5 mm; D = 1 mm; E = 100 μm; F = 20 μm; G, I, J, M−O, R, T = 10 μm; H = 500 μm; K, L, P, Q = 10 mm; S = 50 μm.

Asexual morph: Synnemata scattered, arising from different parts of the host’s body, filiform, simple, occasionally branched, white, 3–20 mm long. Conidiophores densely compacted into a layer along the synnemata, cylindrical, monophialidic or polyphialidic. Phialides smooth-walled, ampulliform, obpyriform, lageniform, hyaline, (4–)5–7(–10) × 2–3 μm. Conidia 1-celled, fusiform elliptical, elliptical, smooth-walled, hyaline, (3–)4–5(–6) × 1.5–2 μm. Sexual morph: Specimens found on adult moths (Lepidoptera), on the underside of dicotyledonous leaves, thin whitish mycelium covering the host body. Perithecia superficial, clustered along the thin whitish synnemata or solitary, ovoid, light yellow (20B), strong orange (26A—26B), (480–)527–729(– 760) × (180–)203–287(–300) μm. Asci cylindrical, hyaline, (223–)299–446(–470) × 3–5 μm. Asci-caps umbonate, hyaline, 2.5–3.5 × 3–3.5 μm. Ascospores filiform, multi-septate, breaking into part-spores, hyaline. Part-spores cylindrical, hyaline, (3.5– )5–9(–11.5) × 0.5–1 μm.

Colony characteristics: Colony obverse on OA compact, cottony, occasionally wrinkled, raised to the agar surface, entire margin, attaining a diam of 42–43 mm in 20 d, white, produced strong greenish yellow (151A—151B) pigment. Sporulation starts at about 14 d after inoculation. Conidiophores mononematous, cylindrical, smooth-walled, hyaline. Phialides solitary, cylindrical, smooth-walled, hyaline, 10–30 × 1–2 μm. Conidia 1-celled, fusiform to elliptical, obovoid, smooth-walled, hyaline, (4–)5–9(–14) × (1.5–)2–3(–5) μm. Colony reverse on OA brilliant greenish yellow (151D). Colony obverse on PDA closely appressed to the agar surface, cottony, entire margin, attaining a diam of 38–42 mm in 20 d, white, produced brilliant greenish yellow (151D) pigment. Colony reverse on PDA dark greenish yellow (152D) in the middle, brilliant greenish yellow (151D). Conidiophores mononematous, cylindrical, smooth-walled, hyaline. Phialides solitary, cylindrical, smooth-walled, hyaline, (5–)11–23(–32) × 1–1.5 μm. Conidia 1-celled, obovoid, smooth-walled, hyaline, (2.5–)4–9(–14) × 1–3 μm.

Additional specimens examined: Thailand, Ranong Province, Kapoe District, Khlong Nakha Wildlife Sanctuary, Khlong Nakha nature trail, 9°27’33”N, 98°30’15”E, on adult moth (Lepidoptera), 11 Jan. 2006, B. Thongnuch, K. Tasanathai, L.N. Yen, L.T. Huyen, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Chaygate (BBH17548:BCC20119); Narathiwat Province, Waeng District, Hala Bala Wildlife Sanctuary, Headquarters official house nature trail, 5°48’28”N, 101°50’42”E, on adult moth (Lepidoptera), 24 Aug. 2011, A. Khonsanit (BBH31282:BCC49306); Narathiwat Province, Waeng District, Hala Bala Wildlife Sanctuary, Headquarters official house nature trail, 5°48’28”N, 101°50’42”E, on adult moth (Pyralidae), 8 Apr. 2012, A. Khonsanit, K. Tasanathai & W. Noisripoom (BBH32436:BCC52398); Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Pak Chong District, Khao Yai National Park, Mo Sing To nature trail, 14°26’23”N, 101°22’20”E, on adult moth (Lepidoptera), 12 Dec. 2012, A. Khonsanit, D. Thanakitpipattana, K. Tasanathai, R. Somnuk, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Noisripoom (BBH33237:BCC58484); Narathiwat Province, Waeng District, Hala Bala Wildlife Sanctuary, Headquarters official house nature trail, 5°48’28”N, 101°50’42”E, on adult moth (Pyralis sp.: Pyralidae) 13 Oct. 2013, A. Abdulrohman, A. Khonsanit & N. Wiriyathanawudhiwong (BBH37641:BCC68341, BCC68342); Yala Province, Bannang Sata District, Bang Lang National Park, Bang Lang Dam nature trail, 6°11’56”N, 101°10’24”E, on adult moth (Lepidoptera), 30 Aug. 2014, A. Abdulrohman (MY09888:BCC74583).

Notes: Akanthomyces laosensis is a recent established species by Wang et al. (2024) found on adult moths (Noctuidae) on the underside of a dicotyledonous leaf in Oudomxay Province, Laos. Descriptions and illustrations were only from the asexual morph. Furthermore, phylogenetically, Ak. laosensis is closely related to Ak. phariformis (Fig. 1A). In our study, collections of Ak. laosensis were found only from southern Thailand, while Ak. phariformis was found only from northern Thailand. The hosts of Ak. laosensis are mostly adult moths in the family Pyralidae, while Ak. phariformis was found on different moth families, such as Erebidae and Noctuidae. Morphologically, Ak. laosensis differs from other related species by producing superficial perithecia laterally in the middle of the filiform synnemata (Fig. 6A–D), produces conidia on PDA and OA 14 d after inoculation (Fig. 6K–T). Moreover, Ak. laosensis produces a yellow pigment diffusing into the agar media (Fig. 6K, L, P, Q).

Akanthomyces noctuidarum Aini et al., MycoKeys 71: 9. 2020. Fig. 7.

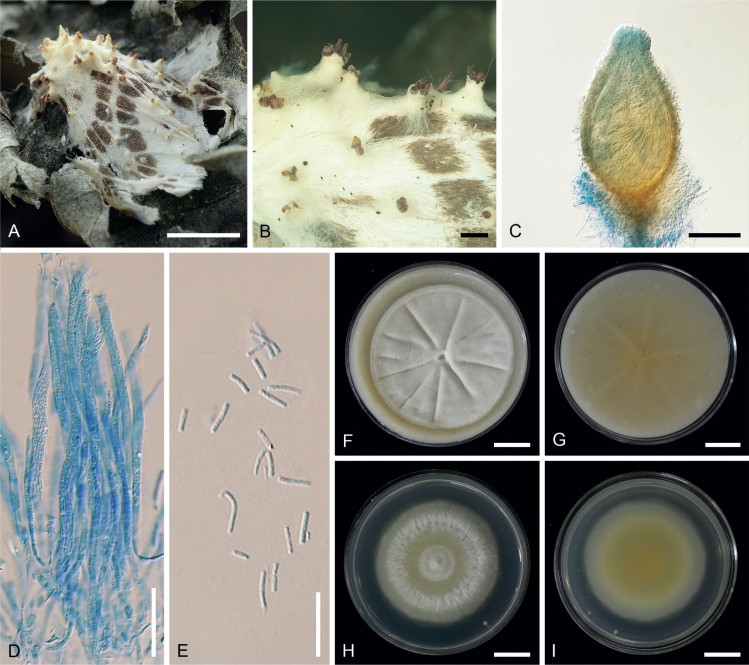

Fig. 7.

Akanthomyces noctuidarum (MY12641). A. Fungus on adult moth. B–D. Perithecia on stipe. E. Asci. F. Asci-caps. G, H. Ascospore. I. Short synnemata. J. Phialides and conidia from short synnemata. K. Conidia from short synnemata. L, M. Phialides and conidia from long synnemata. N. Conidia from long synnemata. O. Colony obverse on OA in 20 d. P. Colony reverse on OA in 20 d. Q. Colony obverse on PDA in 20 d. R. Colony reverse on PDA in 20 d. Scale bars: A, O−R = 10 mm; B, C = 1 mm; D = 200 μm; E, I = 100 μm; F−H, J, K, M, N = 10 μm; L = 50 μm.

Asexual morph: Synnemata scattered, arising from different parts of the host’s body, solitary, occasionally curved. Two types of synnemata were produced on adult moths: Long synnema arising from the thorax of the hosts, filiform, simple, solitary, occasionally curved, white, up to 30 mm long. Conidiophores densely compacted into a layer along the synnemata, cylindrical, mononematous. Phialides solitary, cylindrical with papillate end, monophialidic or polyphialidic, smooth-walled, hyaline, (4–)6–8(–9) × 2–3 μm. Conidia 1-celled, smooth-walled, hyaline, cylindrical with rounded end, occasionally elliptical and fusiform, (3–)4–5(–6) × 1–2 μm. Short synnemata scattered, arising from different parts of the host’s body and wing veins, solitary, cylindrical with rounded ends, white. Conidiophores densely compacted into a layer along the synnemata, cylindrical, mononematous. Phialides solitary, cylindrical with papillate ends, monophialidic or polyphialidic, smooth-walled, hyaline, (4–)5–9(–12) × 2–4 μm. Conidia 1-celled, smooth-walled, hyaline, cylindrical with rounded end, occasionally elliptical and fusiform, 4–6 × 1–2 μm. Sexual morph: Specimens found on adult moths, on the underside of dicotyledonous leaves. Perithecia superficial, scattered on the host body, crowded at the apex of synnemata, occasionally scattered on the lateral of filiform synnemata, obclavate, strong greenish yellow (151C), brilliant greenish yellow (151D), 730–1 050 × 260–450 μm. Asci cylindrical, hyaline, (280–)368–511(–793) × 4–6 μm. Ascicaps umbonate, hyaline, 3–4 × 4–5 μm. Ascospores filiform, multi-septate, breaking into part-spores, hyaline. Part-spores cylindrical, hyaline, 5–11 × 1 μm.

Colony characteristics: Colony obverse on OA compact, raised, cottony, entire margin, attaining a diam of 25–31 mm in 20 d, white, brilliant yellow (9C) in the middle. Colony reverse on OA pale yellow green (157B), light yellowish brown (199C) in the middle. Colony obverse on PDA compact, convex, cottony, entire margin, attaining a diam of 31–33 mm in 20 d, white. Colony reverse on PDA pale greenish white (157D), brownish orange (N167A) in the middle. Conidia and reproductive structures are not observed on both media after 30 d of incubation at 25 °C.

Additional specimens examined: Thailand, Phetchaburi Province, Kaeng Krachan District, Kaeng Krachan National Park, 14°54’13”N, 99°38’03”E, on adult moth (Lepidoptera), 8 Oct. 2002, N.L. Hywel-Jones (NHJ12161); Chaiyaphum Province, Khon San District, Phu Khiao Wildlife Sanctuary, Bung pan nature trail, 16°23’10”N, 101°34’12”E, on adult moth (Lepidoptera), 24 May 2006, B. Thongnuch, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Chaygate (BBH17614:BCC21462); Tak Province, Umphang District, Umphang Wildlife Sanctuary, Thi Lo Su Waterfall nature trail, 15°55’36”N, 98°45’11”E, on adult moth (Lepidoptera), 25 Nov. 2010, A. Khonsanit, K. Sansatchanon, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai & W. Noisripoom (MY06426:BBH30264); Narathiwat Province, Waeng District, Hala Bala Wildlife Sanctuary, 500 nature trail, 5°48’28”N, 101°50’42”E, on adult moth (Lepidoptera), 24 Nov. 2020, A. Khonsanit & K. Tasanathai (MY12641.1:MY12641.2).

Notes: Akanthomyces noctuidarum was reported producing only one type of synnema arising from the hosts’ body and wing veins, cylindrical with papillate end phialides (5–10 × 2–3 μm), and cylindrical with rounded end conidia (3–6 × 1 μm) (Aini et al. 2020). In our study, we describe and illustrate two types of synnemata: one long synnema and numerous short synnemata (NHJ12161, BBH17614, BBH30264 & MY12641.2), collected from various regions in Thailand. However, the size and shape of phialides and conidia are the same (Table 3). Herewith we also describe and illustrate the sexual morph.

Table 3.

Morphological comparisons between sexual-morph of Akanthomyces species on moths

| Species | Perithecia (μm) | Asci (μm) | Asci-caps (μm) | Part-spores (μm) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ak. buriramensis | Superficial, ovoid, 500–750 × 300–400 | 250–450 × 3.5–4 | 3 × 4–5 | 4–14.5 × 0.5–1 | This study |

| Ak. fusiformis | Torrubielloid, superficial, ovoid, 580–640 × 170–210 | 302–450 × 4–5 | 4.5–5.5 × 4–5 | 5–18 × 1 | This study |

| Ak. laosensis | Superficial, ovoid, 480–760 × 180–300 | 223–470 × 3–5 | 2.5–3.5 × 3–3.5 | 3.5–11.5 × 0.5–1 | This study |

| Ak. niveus | Torrubielloid, superficial, ovoid, 400–530 × 180–200 | 273–568 × 4–5 | 2.5–3.5 × 4–5 | 5–22 × 0.5–1 | This study |

| Ak. noctuidarum | Superficial, ovoid, 530–1000 × 290–425 | 170–550 × 2–4 | 3 × 4–5 | 5.5–14.5 × 0.8–1 | Aini et al. (2020), This study |

| Ak. phariformis | Superficial, ovoid, 360–550 × 200–260 | 400–470 × 5 | − | 3–11 × 0.5–1 | This study |

| Ak. pyralidarum | Superficial, ovoid to obpyriform, 290–650 × 150–340 | 170–360 × 2–4 | − | 5–12 × 1 | Aini et al. (2020) |

| Ak. pseudonoctuidarum | Superficial, ovoid, 550–750 × 220–440 | 263–418 × 3–5 | 3–4 × 4–5 | 4–20 × 0.5–1 | This study |

| Ak. tuberculatus | Superficial, narrowly ovoid, dark brown, 420–900 × 180–370 | 300–600 × 4–5 | 4 μm thick | 2–6 × 0.5–1 | Mains (1950) |

Akanthomyces pseudonoctuidarum H. Yu bis & Y. Wang, MycoKeys 101: 124. 2024. Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Akanthomyces pseudonoctuidarum (A, O–P. BBH38012; B. BBH30698; C, D. BBH37920; E–N. BBH40318). A–C. Fungus on adult moths. D, E. Perithecia. F. Asci. G. Asci-caps. H. Ascospore. I. Short synnemata, J. Phialides and conidia from short synnemata. K. Conidia from short synnemata. L. Long synnemata. M. Phialides and conidia from long synnemata, N. Conidia from long synnemata. O. Colony obverse on OA in 20 d. P. Colony reverse on OA in 20 d. Q. Colony obverse on PDA in 20 d. R. Colony reverse on PDA in 20 d. Scale bars: A, O−R = 10 mm; B, C = 5 mm; D, L = 500 μm; E, J = 200 μm; F = 50 μm; G, H, J, K, M, N = 10 μm.

Asexual morph: Synnemata scattered, arising from different parts of the hosts’ body, simple, occasionally curved. Two types of synnemata were observed on adult moths: Long synnemata arising from the thorax and abdomen of the hosts, filiform, simple, occasionally curved, white, (163D). Conidiophores densely compacted into a layer along the synnemata, cylindrical, mononematous. Phialides solitary, monophialidic or polyphialidic, ampulliform, obclavate, obpyriform, lageniform, smooth-walled, hyaline, (6–)8–11(–13) × 2–4 μm. Conidia 1-celled, obovoid, smooth-walled, hyaline, (3–)4–5(–6) × 1.5–2 μm. Short synnemata scattered, arising different parts of the host body, filiform, simple, solitary, occasionally curved, white, light yellow (163D), pale yellow (158A), 1–30 mm long. Conidiophores densely compacted into a layer along the synnemata, cylindrical, mononematous. Phialides solitary, monophialidic or polyphialidic, ampulliform, obclavate, obpyriform, lageniform, smooth-walled, hyaline, (4–)7–11(–17) × 2–4 μm. Conidia 1-celled, obovoid, smooth-walled, hyaline, 3–5 × 1.5–2.5 μm. Sexual morph: Specimens found on adult moths (Arctiidae, Erebidae, Lymantriidae), on the stem of living plants and underside of dicotyledonous leaves. Perithecia superficial, scattered on the host body, crowded at the apex of synnemata, occasionally scattered on the lateral of filiform synnemata, ovoid, strong orange (N163B), brownish orange (165B), (550–)604–737(–750) × (220–)266–388(–440) μm. Asci cylindrical, hyaline, (263–)311–388(–418) × 3–5 μm. Ascicaps umbonate, hyaline, 3–4 × 4–5 μm. Ascospores filiform, multi-septate, breaking into part-spores, hyaline. Part-spores cylindrical, hyaline, (4–)7–15(–20) × 0.5–1 μm.

Colony characteristics: Colony obverse on OA compact, umbonate, cottony, entire margin, attaining a diam of 29–32 mm in 20 d, white, occasionally pale greenish yellow (2D) in the middle. Colony reverse on OA pale yellow (8D). Colony obverse on PDA compact, umbonate, cottony, entire margin, attaining a diam of 31–34 mm in 20 d, white with light greenish yellow (3D). Colony reverse on PDA pale greenish yellow (2D).

Additional specimens examined: Thailand, Kamphaeng Phet Province, Klong Lan District, Klong Lan National Park, Khlong Lan Waterfall nature trail, 16°07’49”N, 99°16’35”E, on adult moth, 24 Sep. 2008, A. Khonsanit, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, R. Ridkaew & W. Chaygate (BBH24658:BCC32598, BCC32599); Songkhla Province, Hat Yai District, Ton Nga Chang Wildlife Sanctuary, Lamnao Phrai nature trail, 6°56’59”N, 100°14’02”E, on adult moth, 10 Aug. 2008, A. Khonsanit, B. Thongnuch, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Chaygate (BBH25301:BCC32161); Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, Nopphitam District, Khao Luang National Park, Krung Ching Waterfall nature trail, 8°43’06”N, 99°41’29”E, on adult moth, 17 Feb. 2009, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, R. Promharn, S. Mongkolsamrit & T. Chohmee (BBH26442:BCC35979, BCC35980); Phetchabun Province, Nam Nao District, Nam Nao National Park, Headquarters nature trail, 16°44’25”N, 101°34’24”E, on adult moth, 19 Feb. 2009, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & T. Chohmee (BBH26449:BCC36300, BCC36301); Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Pak Chong District, Khao Yai National Park, Mo Sing To nature trail, 14°26’20”N, 101°22’19”E, on adult moth, 19 Jul. 2009, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, R. Ridkaew, S. Mongkolsamrit & T. Chohmee (BBH26350:BCC37665:BCC37666); Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Pak Chong District, Khao Yai National Park, Mo Sing To nature trail, 14°26’20”N, 101°22’19”E, on adult moth, 19 Jul. 2009, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, R. Ridkaew, S. Mongkolsamrit & T. Chohmee (BBH26350:BCC37665:BCC37666); ibid., on adult moth, 14 Aug. 2009. K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, R. Ridkaew, S. Mongkolsamrit & T. Chohmee (BBH26530:BCC37916); ibid., on adult moth, 19 Sep. 2009, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, R. Ridkaew, S. Mongkolsamrit & T. Chohmee (BBH26583:BCC39698); ibid., on adult moth (Lymantriidae), 7 Jul. 2011, A. Khonsanit, K. Tasanathai, K. Sansatchanon, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Noisripoom (BBH30740:BCC48709); Chiang Mai Province, Chiang Dao District, Ban Huathung community forest nature trail, 19°25’07”N, 98°57’21”E, on adult moth (Arctiidae), 16 Jul. 2011, A. Khonsanit, K. Tasanathai, K. Sansatchanon, P. Srikitikulchai & S. Mongkolsamrit (BBH26350:BCC37665, BCC37666); ibid., on adult moth, 31 Aug. 2011, A. Khonsanit, K. Tasanathai, K. Sansatchanon, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Noisripoom (BBH31342:BCC49336); Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Pak Chong District, Khao Yai National Park, Chao Ying nature trail, 14°26’20”N, 101°22’19”E, on adult moth (Lymantriidae), 9 Aug. 2012, A. Khonsanit, K. Tasanathai, K. Sansatchanon, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Noisripoom (BBH35668:BCC54481, BCC54889); Chiang Rai Province, Phan District, Doi Luang National Park, Pu Kaeng Waterfall nature trail, 19°27’02”N, 99°43’00”E, on Erebus macrops (Erebidae), 12 Nov. 2013, C. Suriyachadkun (BBH38012:BCC69011); Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Pak Chong District, Khao Yai National Park, Kong Kaeo Waterfall nature trail, 14°26’21”N, 101°22’25”E, on adult moth (Lymantriidae), 28 Nov. 2013, A. Khonsanit, D. Thanakitpipattana, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Mongkolsamrit & W. Noisripoom (BBH37920:BCC69056); Chiang Mai Province, Chiang Dao District, Ban Huathung community forest nature trail, 19°25’07”N, 98°57’21”E, on adult moth (Arctiidae), 29 Oct. 2014, A. Khonsanit, D.Thanakitpipattana, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Wongkanoun & W. Noisripoom, (BBH40206:BCC76478); ibid., on adult moth (Arctiidae), 30 Oct. 2014, A. Khonsanit, D.Thanakitpipattana, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, S. Wongkanoun & W. Noisripoom, (BBH40318:BCC75746, BCC76483); Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, Nopphitam District, Khao Luang National Park, Krung Ching Waterfall nature trail, 8°43’06”N, 99°41’29”E, on adult moth, 26 Jan. 2016, D.Thanakitpipattana, K. Tasanathai, P. Srikitikulchai, R. Promharn, S. Mongkolsamrit, S. Wongkanoun & W. Noisripoom (BBH41238:BCC80356).

Notes: Akanthomyces pseudonoctuidarum is a recently described species by Wang et al. (2024) found on adult moths (Noctuidae) on the underside of leaves from Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. However, they reported only from the asexual morph. In our study, we describe and illustrate the asexual and sexual morph from the same specimen, and the presence of two types of synnemata: a long synnema and short synnemata. We found additional moth families Arctiidae, Erebidae and Lymantriidae as their hosts. Phylogenetically, Ak. pseudonoctuidarum is closely related to Ak. buriramensis (Fig. 1A). Morphologically, Ak. pseudonoctuidarum differs from other related species by producing superficial perithecia at the basal part of the long filiform synnemata (Fig. 8C) and superficial perithecia at the tip of short synnemata (Fig. 8D).

Keys to species of Akanthomyces on moth

Based on asexual morph characters

1a. No synnema, mononematous .............................................................................................................................................................. Ak. fusiformis

1b. Produce two types of synnemata .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2

1c. Produces one type of synnemata .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3

2a. Phialides cylindrical with papillate end, 4–12 × 2–4 μm, conidia cylindrical with round end, ellipsoid, 4–6 × 1–2 μm .................. Ak. noctuidarum

2b. Phialides cylindrical with papillate end, ampulliform, obclavate, obpyriform, lageniform, 4–17 × 2–4 μm, ................................................................ conidia ellipsoidal to long oval, obovoid, 2.6–6.4 × 1.5–2.5 μm ........................................................................................... A. pseudonoctuidarum

2c. Phialides cylindrical to ellipsoidal with papillate end, 5–10 × 1.8–3 μm, conidia fusoid, 1–3.2 × 1–2 μm ..................................... Ak. tortricidarum

3a. Phialides ɥ 10 μm long subcylindrical, narrowly ellipsoidal, 6–16 × 2.5–4 μm, conidia ellipsoid, obovoid, 3–6 × 2–3 μm ................... Ak. aculeatus

3b. Phialides ≤ 10 μm long .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4

4a. Conidia ellipsoid, fusiform, obovoid, 3–5 × 1–2 μm, found only in Buri Ram Province, Thailand ................................................... Ak. buriramensis

4b. Conidia fusiform elliptical, elliptical, 3–6 × 1.5–2 μm, produced yellow pigment into agar media, found only in ........................................................ Southern Thailand .................................................................................................................................................................................. Ak. laosensis

4c. Conidia cylindrical, narrowly fusiform, 4.5–6 × 1.2–1.5 μm, found in Ghana ................................................................................... Ak. tuberculatus

Based on sexual morph characters

1a. Produces torrubielloid perithecia .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2

1b. Produces superficial perithecia on the synnemata ................................................................................................................................................... 3

2a. Asci-caps cone-shaped, 4.5–5.5 × 4–5 μm ........................................................................................................................................... Ak. fusiformis

2b. Asci-caps umbonate, 2.5–3.5 × 4–5 μm ..................................................................................................................................................... Ak. niveus

3a. Produces only crowded perithecia at the apex of synnemata ........................................................................................................... Ak. phariformis

3b. Produces only superficial perithecia in the middle of synnemata ............................................................................................................................. 4

3c. Produces crowded perithecia at the apex and superficial perithecia in the middle of synnemata ........................................................................... 5

4a. Perithecia crowded in the middle of short filiform synnemata ....................................................................................................... Ak. buriramensis

4b. Perithecia clustered in the middle of long filiform synnemata ............................................................................................................... Ak. laosensis

5a. Perithecia ≥ 750 μm long ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 6

5b. Perithecia ≤ 750 μm long ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 7

6a. Perithecia ovoid, 530–1000 × 290–425 μm. Part-spore cylindrical 5.5–14.5 × 0.8–1 μm ............................................................... Ak. noctuidarum

6b. Perithecia narrowly ovoid, 420–900 × 180–370 μm. Part-spores cylindrical 2–6 × 0.5–1 μm .......................................................... Ak. tuberculatus

7a. Perithecia ovoid to obpyriform, 290–650 × 150–340 μm. Part-spores cylindrical 5–12 × 1 μm ...................................................... Ak. pyralidarum

7b. Perithecia ovoid, 550–750 × 220–440 μm. Part-spores cylindrical 4–20 × 0.5–1 μm ........................................................... Ak. pseudonoctuidarum

Residual species of Akanthomyces

The following species of Akanthomyces s. l. could not be confidently assigned in the new classification because they were not sampled as part of our phylogenetic analyses. These species are provisionally retained within Akanthomyces s. l. until further molecular phylogenetic studies are made to classify them in a phylogenetic system, or when we find the sexual morph connection for the species of Akanthomyces s. l.

Akanthomyces angustisporus Mains, Mycologia 42: 573. 1950.

Akanthomyces aranearum (Petch) Mains, Mycologia 42: 574. 1950.

Basionym: Hymenostilbe aranearum Petch, Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 16: 221. 1932.

Akanthomyces clavata (Mains) K.T. Hodge, In: White et al., Clavicipitalean Fungi: Evolutionary Biology, Chemistry, Biocontrol, and Cultural Impacts (New York): 87. 2003.

Basionym: Insecticola clavata Mains, Mycologia 42: 577. 1950.

Akanthomyces fragilis (Petch) (Mains) K.T. Hodge, In: White et al., Clavicipitalean Fungi: Evolutionary Biology, Chemistry, Biocontrol, and Cultural Impacts (New York): 87: 2003.

Basionym: Hymenostilbe fragilis Petch Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 21: 56. 1937.

Akanthomyces gracilis Samson & H.C. Evans, Acta Bot. Neerl. 23: 29. 1974.

Akanthomyces johnsonii (Massee) Vincent et al., Mycologia 80: 685. 1988.

Basionym: Pistillaria johnsonii Massee, Bull. Misc. Inf., Kew: 165. 1901.

Novel genera and new combinations

Arachnidicola Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, gen. nov. MycoBank MB 848891.

Etymology: Refers to the hosts of this genus that is colonizes — spiders (Araneae).

Typus: Arachnidicola sulphurea (Mongkol. et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard

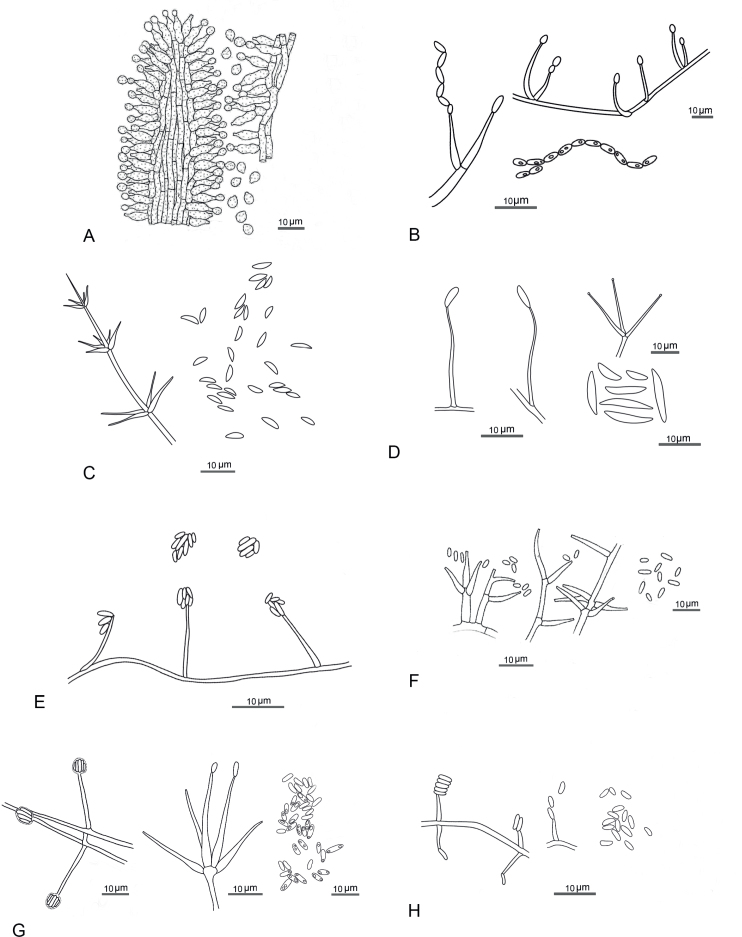

Diagnosis: Isaria-like or lecanicillium-like. Synnemata numerous, covered by dense white to cream, or yellowish white mycelia bearing numerous conidiophores with powdery conidia. Conidiophores loosely grouped together, arising from different parts of the spider, verticillate with phialides in whorls of two to five. Phialides hyaline, cylindrical to ellipsoidal basal portion, tapering into a thin, distinct neck, somewhat inflated base. Conidia in chains, hyaline, cylindrical to ellipsoidal, fusiform to ellipsoidal (Fig. 9B). Sexual morph: Stromata consisting of dense hyphae, completely covering the host. Perithecia torrubiellalike, scattered on the abdominal part of the host, dark orange, deep yellow, superficial, narrowly ovoid. Asci hyaline, cylindrical, 8-spored, apex and bottom of asci thicker than the middle part. Ascospores hyaline, cylindrical, filiform dissociating into part-spores.

Fig. 9.

Types of conidiogenous cells and conidia of known and new genera. A. Akanthomyces aculeatus on host after Seifert et. al. (2011), plate 84C. B. Arachnidicola sulphurea on culture media adapted from fig. 3 in Mongkolsamrit et al. (2018). C. Corniculantispora psalliotae on culture media adapted from fig. 12 in Zare & Gams (2001). D. Corpulentispora magnispora on culture media adapted from fig. 30 in Zhang et al. (2020). E. Kanoksria zaquensis on culture media adapted from fig. 3 in Wang et al. (2023). F. Lecanicillium lecanii on culture media adapted from fig. 3 in Zare & Gams (2001). G. Zarea fungicola on culture media adapted from fig. 3 in Zare & Gams (2008). H. Zouia cauligalbarum on culture media adapted from fig. 3 in Zhou et al. (2018). Line drawings by P. Wongpitakchai (B–E, G–H).

Habitat: On spiders (Araneae).

Distribution: Thailand and China.

Arachnidicola araneicola (W.H. Chen et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 849875.

Basionym: Akanthomyces araneicola W.H. Chen et al., Phytotaxa 409: 228. 2019.

Arachnidicola araneogena (Z.Q. Liang et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 849877.

Basionym: Akanthomyces araneogenus Z.Q. Liang et al., Phytotaxa 379: 69. 2018.

Arachnidicola bashanensis (W.H. Chen et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 852005.

Basionym: Akanthomyces bashanensis W.H. Chen et al., MycoKeys 98: 305. 2023.

Arachnidicola beibeiensis (W.H. Chen et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 852006.

Basionym: Akanthomyces beibeiensis W.H. Chen et al., MycoKeys 98: 307. 2023.

Arachnidicola kanyawimiae (Mongkol. et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 849878.

Basionym: Akanthomyces kanyawimiae Mongkol. et al., Mycologia 110: 237. 2018.

Arachnidicola kunmingensis (H. Yu bis et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 852008.

Basionym: Akanthomyces kunmingensis Hong Yu bis et al., MycoKeys 101: 121. 2024.

Arachnidicola subaraneicola (H. Yu bis et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 852009.

Basionym: Akanthomyces subaraneicola H. Yu bis et al., MycoKeys 101: 126. 2024.

Arachnidicola sulphurea (Mongkol. et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 849883.

Basionym. Akanthomyces sulphureus Mongkol. et al., Mycologia 110: 237. 2018.

Arachnidicola thailandica (Mongkol. et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 849879.

Basionym: Akanthomyces thailandicus Mongkol. et al., Mycologia 110: 240. 2018.

Arachnidicola tiankengensis (W.H. Chen et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 852012.

Basionym: Akanthomyces tiankengensis W.H. Chen et al., Microbiol. Spectr. 10: 6. 2022.

Arachnidicola waltergamsii (Mongkol. et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 852013.

Basionym: Akanthomyces waltergamsii Mongkol et al., Mycologia 110: 241. 2018.

Key to species of Arachnidicola on spiders

1a. Produces lecanicillium-like asexual morph ................................................................................................................................................................ 2

1b. Produces isaria-like asexual morph ........................................................................................................................................................................... 3

2a. Conidia cylindrical to ellipsoid, (3–5 × 1–2 μm), found in Thailand ..................................................................................................... Ar. thailandica

2b. Conidia obovoid, sub-globose, ellipsoid, (2–3 × 1–2 μm), found in China ...................................................................................... Ar. tiankengensis

3a. Phialides cylindrical, inflated base, tapering into a thin neck, ≤ 12 μm long ............................................................................................................. 4

3b. Phialides cylindrical, inflated base, tapering into a thin neck, ≥ 12 μm long ............................................................................................................. 7

4a. Conidia ellipsoid, found in Thailand ...................................................................................................................................................... Ar. sulphurea

4b. Conidia fusiform to ellipsoid, found in China ............................................................................................................................................................ 5

4c. Conidia sub-globose, ellipsoid, obovoid .................................................................................................................................................................... 6

5a. Conidia fusiform to ellipsoid, 1.7–2.6 × 1.6–1.8 μm ......................................................................................................................... Ar. bashanensis

5b. Conidia fusiform to ellipsoid, 2.0–3.3 × 2.0–2.6 μm ........................................................................................................................... Ar. beibeiensis

6a. Spider host covered with dense white to cream mycelia, found in Thailand ................................................................................. Ar. waltergamsii

6b. Spider host covered with dense white to cream mycelia with powdery conidia, found in Thailand .............................................. Ar. kanyawimiae

7a. Conidia ellipsoid, obovoid (2–5 × 1–2 μm), found in China ..................................................................................................................Ar. araneicola

7b. Conidia ellipsoid, globose (2–3 × 1–2 μm), found in China ............................................................................................................. Ar. araneogenum

7c. Conidia ellipsoid, to long oval (1.9–3.5 × 1.1–1.8 μm), found in China .......................................................................................... Ar. kunmingensis

7d. Conidia ellipsoidal to long oval (3.0–5.4 × 1.8–3.4 μm), found in China .........................................................................................Ar. subaraneicola

Corniculantispora Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, gen. nov. MycoBank MB 851978.

Etymology: From the Latin “corniculantis” means crescent-shaped, refers to the shape of the macroconidia produced in this genus.

Typus: Corniculantispora psalliotae (Treschew) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard

Diagnosis: Conidiogenous cells aculeate, aphanophialides, rather long, inflated, verticillate, arising from undifferentiated prostrate conidiophores, first flask-shaped, tapering into thread-like neck, but soon collapsing and becoming reduced to very fine denticles with solitary conidia still remaining at apex, solitary or more often 3 or 6 in whorls. Conidia dimorphic, can be macro- and microconidia formed from phialides, typically solitary or in small clusters at right angles to phialide tip, commonly falcate with pointed ends, subsequent ones oval to ellipsoidal. Macroconidia crescent-shaped, slightly curved, usually with sharply pointed ends, 1-celled. Microconidia formed subsequently, ellipsoidal to fusoid with round ends, oval to ellipsoidal, sub globose, nearly straight to slightly curved. Octahedral crystals present or absent (Fig. 9C). Sexual morph: Unknown.

Habitat: The genus is found on a wide range of hosts including Araneae, cicadellid on leaf of Theobroma cacao, collembola, eggs of Meloidogyne, greenhouse whitefly (Trialeurodes vaporariorum), mites, mosquito larvae, nymphs of Ixodes (tick), silk moth (Bombyx mori) and associated with Agaricus bisporus and A. bitorquis, Puccinia coronata, Sphaerotheca fuliginea, S. pannosa. It was also reported from leaf litter and soil.

Distribution: Bulgaria, China, Cuba, Germany, Ghana, Netherlands, India, Indonesia, Israel, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Spain, UK, USA.

Corniculantispora aranearum (Petch) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 851984.

Basionym: Acremonium aranearum Petch, Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 16: 242. 1932.

Synonyms: Aphanocladium aranearum (Petch) W. Gams, Cephalosporium-artige Schimmelpilze: 198. 1971. Aphanocladium aranearum var. sinense C.D. Chen, Acta Mycol. Sin. 3: 96. 1984.

?Acremonium fimicola Massee & E.S. Salmon, Ann. Bot. 16: 79. 1902.

?Sporotrichum roseolum Oudem. & Beij., Ned. Kruidk. Arch. 3, 2: 910. 1903.

Lecanicillium aphanocladii Zare & W. Gams, Nova Hedwig. 73: 27. 2001.

Corniculantispora dimorpha (J.D. Chen). Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 851985.

Basionym: Aphanocladium dimorphum J.D. Chen, Acta Mycol. Sin. 4: 230. 1985.

Synonym: Lecanicillium dimorphum (J.D. Chen) Zare & W. Gams, Nova Hedwig. 73: 24. 2001.

Corniculantispora psalliotae (Treschew) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 851987.

Basionym: Verticillium psalliotae Treschew, Dan. Bot. Arkiv. 11(1): 7. 1941.

Synonym: Lecanicillium psalliotae (Treschew) Zare & W. Gams, Nova Hedwig. 73: 21. 2001.

Corpulentispora Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, gen. nov. MycoBank MB 851994.

Etymology: Latin “Corpulentus” means large or larger, refers to its large conidia.

Typus: Corpulentispora magnispora (Z.F. Zhang & L. Cai) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard

Diagnosis: Mycelium hyaline, septate, smooth. Conidiophores arising from aerial hyphae, erect, smooth, hyaline. Phialides arising from aerial hyphae solitary, or in whorls of 2–5 at the apex of conidiophores, straight or slightly curved, tapering to the apex, smooth, hyaline. Conidia rare, unicellular, smooth, hyaline, variable in size. Macroconidia long fusiform or falcate. microconidia much fewer than macroconidia (Fig. 9D). Sexual morph: Unknown.

Habitat: Soil.

Distribution: China.

Corpulentispora magnispora (Z.F. Zhang & L. Cai) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 851995.

Basionym: Lecanicillium magnisporum Z.F. Zhang & L. Cai, Fungal Divers. 106: 75. 2020.

Synonym: Gamszarella magnispora (Z.F. Zhang & L. Cai) Crous, Persoonia 51: 390. 2023.

Kanoksria Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, gen. nov. MycoBank MB 851982.

Etymology: Kanoksria is named in honour of Miss Kanoksri Tasanathai, who is working on invertebrate pathogenic fungi research in BIOTEC for more than 20 years.

Typus: Kanoksria zaquensis (Y.H. Wang et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard

Diagnosis: The vegetative hyphae delicate, hyaline, smooth-walled. Phialides occurring directly on the aerial hyphae, simple. Conidia produced on PDA, one-celled, smooth-walled, hyaline, adhering in heads at the apex of the phialides, long-ellipsoidal to almost cylindrical (Fig. 9E). Sexual morph: Unknown.

Habitat: Stroma and the sclerotium of O. sinensis on the ground.

Distribution: China.

Kanoksria zaquensis (Y.H. Wang et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 851983.

Basionym: Akanthomyces zaquensis Y.H. Wang et al., Phytotaxa 579: 203. 2023.

Lecanicillium (Zimm) Zare & Gams, Nova Hedwig. 72: 50. 2001.

Refers to members of the clade B of our phylogenetic analyses consisting of the type of the genus Lecanicillium (L. lecanii) and other Lecanicillium species. We propose that the genus Lecanicillium should be resurrected to accommodate species in this clade.

Typus: Lecanicillium lecanii (Zimm.) Zare & W. Gams

Diagnosis: Conidiophores arising from aerial hyphae, prostrate and occasionally from the subtending hyphae, erect short bearing one or two whorls phialides. Phialides discrete, aculeate, tapering to a narrow tip, in which collarette and periclinal wall thickening are hardly visible, verticillate or solitary. Conidia adhering in slimy heads or fascicles, sometimes forming chains, short to long ellipsoidal to falcate with point ends (Fig. 9F, Zare & Gams 2001). Sexual morph: White to cream thin mycelium covering on scale insect, slightly tufted, pulverulent. Perithecia irregularly scattered to crowded, superficial or slightly embedded, ovoid, reddish brown to dark chestnut brown. Asci cylindrical, thickened at the apex. Ascospores filiform, multiseptate (Mains 1949).

Habitat: On scale insects [e.g. Pulvinaria floccifera, Coccus viridis (Coccidae)] on the underside of leaves of forest plant, ladybug (Coleoptera), spider (Araneae), lepidopteran pupa and adult moths (Lepidoptera), weevil (Coleoptera) and soil.

Distribution: China, Canada, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Germany, Indonesia, Iran, Jamica, Kenya, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Turkey, UK, and USA.

Lecanicillium attenuatum Zare & W. Gams, Nova Hedwig. 73: 19. 2001.

Synonym: Akanthomyces attenuatus (Zare & W. Gams) Spatafora et al., IMA Fungus 8: 342. 2017.

Lecanicillium araneogenum Z.Q. Liang et al., Phytotaxa 379: 69. 2018.

Synonym: Akanthomyces neoaraneogenus (Z.Q. Liang et al.), Shrestha et al., Mycol. Progr. 18: 986. 2019.

Lecanicillium araneosum (W.H. Chen et al.) Khons. et al., comb. nov. MycoBank MB 848900.

Basionym: Akanthomyces araneosus W.H. Chen et al., Microbiol. Spectr. 10: 6. 2022.

Lecanicillium lecanii (Zimm.) Zare & Gams, Nova Hedwig. 72: 51. 2001.

Basionym: Cephalosporium lecanii Zimm., Teysmannia 9: 241. 1899.

Synonyms: Verticillium lecanii (Zimm.) Viégas, Revista Inst. Café São Paulo 14: 754. 1939.

Akanthomyces lecanii (Zimm.) Spatafora et al., IMA Fungus 8: 343. 2017.

Torrubiella confragosa Mains, Mycologia 41: 305. 1949.

Cordyceps confragosa (Mains) G.H. Sung et al., Stud. Mycol. 57: 49. 2007.

Hirsutella confragosa Mains, Mycologia 41: 305. 1949.

Lecanicillium lepidopterorum (W.H. Chen et al.) Khons., Thanakitp. & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 848901.

Basionym: Akanthomyces lepidopterorum W.H. Chen et al., Phytotaxa 459: 121. 2020.

Lecanicillium longisporum (Petch) Zare & W. Gams, Nova Hedwig. 73: 16. 2001.

Basionym: Cephalosporium longisporum Petch, Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 10: 166. 1925.

Synonyms: Cephalosporium dipterigenum Petch, Naturalist (Hull) 56: 102. 1931.

Akanthomyces dipterigenus (Petch) Spatafora et al., IMA Fungus 8: 343. 2017.

Lecanicillium muscarium (Petch) Zare & W. Gams, Nova Hedwig. 73: 13. 2001.

Basionym: Cephalosporium muscarium Petch, Naturalist (Hull), ser. 3: 102. 1931.

Synonym: Akanthomyces muscarius (Petch) Spatafora et al., IMA Fungus 8: 343. 2017.

Lecanicillium neocoleopterorum (W.H. Chen et al.), Khons., Thanakitp., Mongkols., Kobmoo & Luangsa-ard, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 848903.

Basionym: Akanthomyces neocoleopterorum W.H. Chen et al., Phytotaxa 432: 122. 2020.

Lecanicillium pissodis Kope & I. Leal, Mycotaxon 94: 334. 2006.

Synonym: Akanthomyces pissodis (Kope & I. Leal) W.H. Chen et al., Phytotaxa 459: 120. 2020.

Lecanicillium sabanense Chir.-Salom. et al., Phytotaxa 234: 68. 2015.

Synonym: Akanthomyces sabanensis (Chir.-Salom. et al.) Chir.-Salom. et al., IMA Fungus 8: 343. 2017.

Lecanicillium uredinophilum M.J. Park et al., Mycotaxon 130: 997. 2015.

Synonym: Akanthomyces uredinophilus (M.J. Park et al.) Manfrino & Leclerque, Diversity 118: 5. 2022.

The following Lecanicillium species were placed in the genus based on morphological characteristics. We retain them in Lecanicillium pending future phylogenetic analyses:

Lecanicillium aranearum (Petch) Zare & W. Gams, Nova Hedwig. 73: 30. 2001.

Basionym: Cephalosporium aranearum Petch, Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 16: 226 .1932.

Lecanicillium evansii Zare & W. Gams, Nova Hedwigia Beih. 73: 32. 2001.

Lecanicillium fusisporum (W. Gams) Zare & W. Gams, Nova Hedwig. 73: 34. 2001.

Basionym: Verticillium fusisporum W. Gams, Cephalosporiumartige Schimmelpilze (Stuttgart): 182. 1971.

Lecanicillium nodulosum (Petch) Zare & W. Gams, Nova Hedwig. 73: 18. 2001.

Basionym: Cephalosporium nodulosum Petch, Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 23: 144. 1939.

Lecanicillium tenuipes (Petch) Zare & W. Gams, Nova Hedwig. 73: 29. 2001.

Basionym: Acremonium tenuipes Petch, Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 21: 66. 1937.

Synonyms: Verticillium tenuipes (Petch) W. Gams, Cephalosporium-artige Schimmelpilze (Stuttgart): 176. 1971.

Sporotrichum aranearum Cavara, Fung. Long. Exsicc. 5: 240. 1895.

Engyodontium aranearum (Cavara) W. Gams et al., Persoonia 12: 138. 1984.

Note: Since there is already a species called Lecanillium aranearum, Zare & Gams (2001) used the next oldest epithet available in order to avoid homonymy.

Lecanicillium saksenae (Kushwaha) Kurihara & Sukarno, Mycoscience 50: 377. 2009.

Basionym: Verticillium saksenae Kushwaha, Curr. Sci. 49: 948. 1980.

Keys to species of Lecanicillium

Based on asexual morph characters