Abstract

Background and Aim:

Ascaridia galli, a nematode that frequently infects the digestive tract of chickens, is a significant concern for poultry health. In response, the use of medicinal plant-derived anthelmintics was proposed as a potential solution. This study observed the in vitro effectiveness of a single, graded dose of the ethanol extract of Andrographis paniculata, Phyllanthus niruri L., Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb., and Curcuma aeruginosa Roxb. on the movement activity of adult A. galli every hour for 6 h, followed by an analysis of worm cuticle damage in A. galli.

Materials and Methods:

A randomized block design was used. Adult A. galli were collected from the intestinal lumen of fresh free-range chickens. Each petri dish contained two A. galli for each treatment with three replications. Each plant extract (A. paniculata, P. niruri L., C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb.) was evaluated with three distinct doses, which were 250 μg/mL, 500 μg/mL, and 1000 μg/mL; 0.9% sodium chloride solution was used as a negative control, and 500 μg/mL Albendazole solution was used as a positive control. The active compound content of A. paniculata, P. niruri L., C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb. extracts were analyzed using ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. The movement activity of A. galli was determined by the percentage score value from the 1st to the 6th h in each treatment group, followed by analysis of damage to the A. galli cuticle layer using a nano-microscope and histopathological images.

Results:

Analysis of variance demonstrated that at doses of 250 μg/mL and 500 μg/mL, the ethanol extracts of A. paniculata, P. niruri L., C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb. did not have a significant effect on the effectiveness of A. galli’s motility (>0.005). However, at a dose of 1000 μg/mL, the ethanol extract of A. paniculata, P. niruri L., C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb. reduced the motility of A. galli. Importantly, the motility of A. galli in the dose of 1000 μg/mL A. paniculata and P. niruri L. extract groups was very weak and significantly different (p < 0.001) compared to the negative control group. The content of the active compound Andrographolide in the ethanol extract of A. paniculata and the active compound 5-Methoxybenzimidazole in the extract of P. niruri L. are strongly suspected to play an important role in damaging and shedding the cuticle layer of A. galli.

Conclusion:

All herbal extracts have anthelmintic activity at a concentration of 1000 μg/mL. Extracts of A. paniculata, P. niruri L., C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb. have activities that can damage and dissolve the cuticle layer of A. galli, resulting in the weakening of the motility of A. galli.

Keywords: Ascaridia galli, cuticle, in vitro motility, plant extract

Introduction

Chicken is a poultry commodity and an important source of animal protein. Several factors, such as poultry diseases, affect poultry farming. One chronic poultry disease with an economic impact is infection by a parasitic worm. Ascaridia galli is a nematode that has become the most common helminth parasite in poultry. A. galli is a significant parasitic nematode that affects poultry, particularly in Indonesia and globally. A. galli infection in chickens has various harmful effects on the health and productivity of animals. The results of malnutrition, emaciation, malabsorption, and anemia. It also suppresses the immune system and renders chickens more vulnerable to other infections at the same time. The effects of the parasite on chicken health are further complicated by its capacity to serve as a vector for various infections [1–3].

The routine commercial use of anthelmintics can lead to several problems, including the development of worm resistance, environmental pollution, and accumulation of drug residues in tissues. Among the alternatives to anthelmintics, natural products are more environmentally friendly, consumer-friendly, and host-friendly because of their lower or no toxic effects. Resistance of anthelmintics to A. galli is a major concern in poultry farming. The emergence of drug resistance has hampered the use of commercial synthetic anthelmintics and is frequently attributed to incomplete treatment with prescribed doses and withdrawal times. This resistance has necessitated the development of more sustainable approaches for parasitic infection control in poultry [4, 5]. Using medicinal herbs as traditional medicine is one of the potential ways to treat this parasitic worm infection to gain an optimum chicken health status by following its back-to-nature concept.

Many medicinal plants have antioxidant, antiviral, antibacterial, and antiparasitic activities, including Phyllanthus niruri L., Andrographis paniculata, Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb., and Curcuma aeruginosa Roxb. The P. niruri L. plant has long-standing ethnomedical records from Ayurvedic, Chinese, Malay, and Indonesian. One of the most popular medicinal plants in Asia, America, and Africa is A. paniculata wall (family Acanthaceae). The genus Curcuma mainly originates from Asia, Australia, and South America, and it has been used for medicinal, aromatic, nutritional, and cosmetic purposes [6].

Our research is a promising hope for the poultry industry. By investigating the anthelmintic properties of P. niruri L., A. paniculata, C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb., we aimed to provide a more affordable and effective treatment for anthelmintic resistance. This study aimed to elaborate on the in vitro anthelmintic effects of the ethanol extract of P. niruri L., A. paniculata, C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb. on A. galli motility, analyze damage to the cuticle, and consider the possibility of using plant extracts as an alternative anthelmintic to parasitic infection.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Animal Laboratory Ethical Committee, School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, IPB University (Approval No.: 84/KEH/SKE/II/2024).

Study period and location

The study was conducted from January 2024 to May 2024 in the Veterinary Helminthology Laboratory, Division of Parasitology and Medical Entomology, Division of Veterinary Pathology, Division of Veterinary Pharmacy, School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences IPB University and Tropical Biopharmaca Research Center, IPB University.

Preparation of the plant’s simplicial

All plants of P. niruri L., A. paniculata, C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb. provided by the Tropical Biopharmaca Research Center at IPB University were washed with tap water and dried. The dried simplicity of all plants was achieved by meshing 20 mesh to obtain the powder form [7].

Extraction of plants

The extract was prepared according to the book of Indonesian Pharmacopeia, 2nd edition [8]. The dried powder of the plants was extracted using a maceration method for 3 × 24 h with an ethanol concentration of 96%. The ratio of simplicial to ethanol was 1:10. The condensed extracts were obtained by evaporating the extract filtrate using a rotary evaporator at 40°C and 50 rpm and then freeze-dried using a freeze dryer [7].

Phytochemical analysis

Chemical components were identified using the Vanquish method according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Chemical components of the extracts were examined using a Q Exactive Plus ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometer Orbitrap (UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS, ThermoFisher Scientific) equipped with an Accucore C18 (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.5 μm). The mobile phase used was 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B) with a gradient elution system: 0.0–1.0 min (5% B), 1.0–25.0 min (5%–95% B), 25.0–28.0 min (95% B), and 28.0–33.0 min (5% B). The flow rate was maintained at 0.2 mL/min, with an injection volume of approximately 2 μL. Other parameters for the UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS analysis were as follows: The source of mass spectrometry ionization was electrospray ionization (+) using a Q-Orbitrap mass analyzer with an m/z range of 100 m/z–1500 m/z. The collision energies used for fragmentation were 18, 35, and 53 eV. The spray voltage was approximately 3.8 kV, the capillary temperature was 320°C, and the sheath and auxiliary gas flow rates were 15 and 3 mL/min, respectively. We used scan-type full MS/dd MS2 for the positive-ion mode. The metabolites were tentatively identified using the acquired mass spectra and analyzed using Compound Discoverer version 3.2. software (https://www.thermofisher.com) in an untargeted metabolomics workflow. Peak extraction was filtered, and the MzCloud (https://www.mzcloud.org) and ChemSpider databases (https://www.chemspider.com) were employed for annotation with mass accuracies between –5 parts per million (ppm) and 5 ppm.

In vitro motility analysis of the adult A. galli worm

The samples used in this in vitro assay were fresh A. galli adult worms under the criteria that the worm was still active in movement [9]. Adult A. galli were collected from intestine of the kampung chicken (Indonesian Indigenous chicken/local breed) obtained from the slaughterhouse. The study used a completely randomized design. The worms were placed in a Petri dish. Each Petri dish contained two adult worms for each treatment in three replicates. Each plant extract (P. niruri L., A. paniculata, C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb.) was evaluated with three distinct doses, which were 250 μg/mL, 500 μg/mL, and 1000 μg/mL [10]. A 0.9% sodium chloride solution was used for the negative control group, and Albendazole 500 μL was used to validate the effectiveness of the plant extracts. The effectivity of worm motility was determined using a scoring activity from 1- to 6-h post-exposure (PE) as follows: score 0: No movement (worm died); score 1: Weak movement; score 2: Moderate movement; and score 3: Active movement.

Microscopical preparations

The entire A. galli specimen was fixed in 10% neutral buffer formalin. The fixated worms were then cut to a thickness of 5 mm from the 1/3 anterior, 1/3 middle, and 1/3 posterior parts of the worm. Tissues were placed in a tissue cassette and then put in the tissue processor for dehydration in graded ethanol followed by the clearing process using a xylol solution. The tissue samples were then embedded in a paraffin block, cut using a rotary microtome with a thickness of ±3–5 μm, and stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin [11]. The microscopical lesion of the worm cuticle was examined using a state-of-the-art Digital MicroscopeVHX-7000 (Keyence, Japan) and an Olympus Photomicroscope BX5 (Olympus, Japan) showcasing the use of advanced equipment in our research.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using a two-way analysis of variance to determine the effect of plant extracts on A. galli from the PE group in 1 h–6 h. Significant differences among treatment groups are indicated by p < 0.05.

Results

Phytochemical analysis

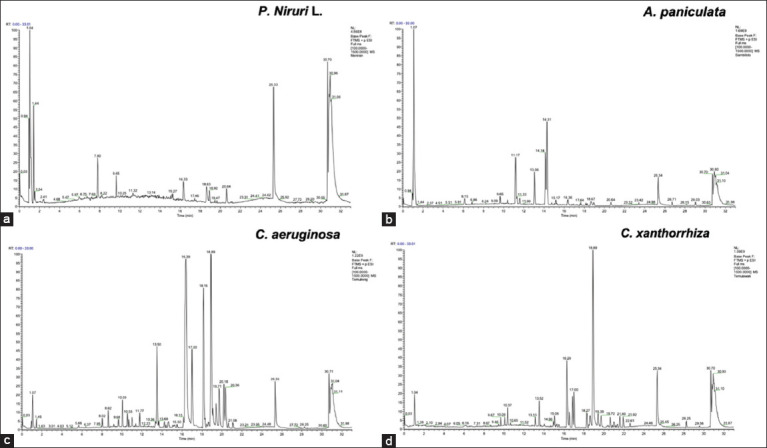

Through UPLC-MS analyses, 100 compounds in P. niruri L., extracts were identified. The chromatogram diagram is shown in Figure-1a. It contains flavonoids, an alkaloid (phyllanthin), coumarin (linamarin), lignan (5-Methoxybenzimidazole), and phenols (zingerol). In the ethanol extracts of A. paniculata (Figure-1b), the detected compounds were terpenoid andrographolide (retention time [RT] 11,265), and 3-O-β-D-glucosyl-14-deoxyandrographolide (RT 14,389 min).

Figure-1.

The UPLC-MS chromatogram of (a) P. niruri L., (b) A. paniculata, (c) C. aeruginosa Roxb., and (d) C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. Several peaks were detected in all extracts. P. niruri=Phyllanthus niruri, A. paniculata=Andrographis paniculata, C. xanthorrhiza Roxb=Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb, C. aeruginosa Roxb=Curcuma aeruginosa Roxb.

The compound analysis of the C. aeruginosa Roxb. ethanol extract (Figure-1c) revealed phenolic curcumin (RT 20,615 min) and terpenoid alantolactone (RT 11,777 min). Similarly, the C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. ethanol extract was found to contain phenolic curcumin (RT 16,848 min), curcumin (RT 20,358 min), and terpenoid alantolactone (RT 17,045 min) (Figure-1d). Table-1 shows the phytochemical active compound composition of the ethanol extract.

Table-1.

Phytochemical active compound composition of the ethanol extract.

| No. | Name | Formula | Annot. DeltaMass (PPM) | MW | Retention time (min) | Classification | Plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | (-)-Nupharamine | C15H25NO2 | 1. 01 | 251.18878 | 16.295 | Alkaloids | C. aeruginosa, C. xanthorrhiza |

| 2. | 8-Methyl-8-azabicyclo[3.2.1] oct-3-yl (3S)-1,2- dithiolane-3-carboxylate | C12H19NO2S2 | −3.5 | 27.308.476 | 1.172 | Alkaloids | P. niruri |

| 3. | 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydro-β- carboline-3-carboxylic acid | C12H12N2O2 | 00.56 | 216.09.00 | 6.416 | Alkaloids | P. niruri |

| 4. | Phenethylamine | C8H11N | 03.29 | 12.108.955 | 0.170833333 | Alkaloids | P. niruri |

| 5. | Genistein | C15H10O5 | 0.052083333 | 27.005.303 | 12.792 | Isoflavone | A. paniculata |

| 6. | 5-Ethyl-3,8-dimethyl-1, 7-dihydroazulene | C14H18 | 1.59 | 186.14115 | 17.96 | Flavonoids | C. aeruginosa |

| 7. | Baicalin | C21H18O11 | −0.06 | 44.608.489 | 0.426388889 | Flavonoids | A. paniculata |

| 8. | Luteolin 7-O-glucuronide | C21H18O12 | 00.39 | 462.08.00 | 10.464 | Flavonoids | A. paniculata |

| 9. | Tectoridin | C22H22O11 | 00.23 | 46.211.632 | 10.083 | Flavonoids | A. paniculata |

| 10. | Favan-3-ol | C15H14O2 | 01.09 | 22.609.981 | 14.383 | Flavonoids | A. paniculata |

| 11. | Tangeritin | C20H20O7 | 00.48 | 37.212.108 | 14.567 | Flavonoids | A. paniculata |

| 12. | Linamarin | C10H17NO6 | 0.085416667 | 24.710.599 | 1.501 | Coumarin | P. niruri |

| 13. | Meranzin | C15H16O4 | 00.03 | 26.010.494 | 19.511 | Coumarin | P. niruri |

| 14. | Aesculin | C15H16O9 | 01.05 | 34.007.979 | 6.836 | Coumarin | P. niruri |

| 15. | Phellopterin | C17H16O5 | 0.050694444 | 30.009.999 | 17.733 | Coumarin | A. paniculata |

| 16. | 4-Hydroxycoumarin | C9H6O3 | 01.32 | 16.203.191 | 6.215 | Coumarin | A. paniculata |

| 17. | Osthol | C15H16O3 | 1.36 | 244.11028 | 13.129 | Coumarin | C. aeruginosa, C. xanthorrhiza |

| 18. | 5-Methoxybenzimidazole | C8H8N2O | 0.100694444 | 14.806.394 | 1.157 | Lignan | P. niruri |

| 19. | Phyllanthin | C24H34O6 | 0.086111111 | 41.823.622 | 0.8 | Lignan | P. niruri |

| 20. | Zingerol | C11H16O3 | 0.063888889 | 19.611.012 | 9.178 | Phenol | P. niruri |

| 21. | Curcumin | C21H20O6 | 0.76 | 368.12627 | 16.848 | Phenol | C. aeruginosa, C. xanthorrhiza |

| 22. | Curcumin II | C20H18O5 | 1.57 | 338.11595 | 16.544 | Phenol | C. aeruginosa, C. xanthorrhiza |

| 23. | Thymol | C10H14O | 2.02 | 150.10477 | 21.35 | Phenol | C. xanthorrhiza |

| 24. | Damascenone | C13H18O | 00.53 | 19.013.587 | 17.323 | Volatile oil | P. niruri |

| 25. | Dehydrocostus lactone | C15H18O2 | 00.52 | 2.301.308 | 0.815972222 | Terpenes | P. niruri |

| 26. | (-)-Andrographolide | C20H30O5 | −0.75 | 35.020.906 | 11.265 | Terpenes | A. paniculata |

| 27. | 3-O- β-D-glucosyl-14- deoxyandrographolide | C26H40O9 | −0.19 | 49.626.714 | 11.41 | Terpenes | A. paniculata |

| 28. | Linalyl benzoate | C17H22O2 | −0.14 | 25.816.194 | 14.242 | Terpenes | A. paniculata |

| 29. | Valerenic acid | C15H22O2 | −0.42 | 234.16188 | 16.384 | Terpenes | A. paniculata |

| 30. | (+)-Alantolactone | C15H20O2 | 1.2 | 232.14661 | 18.586 | Terpenes | C. aeruginosa, C. xanthorrhiza |

| 31. | (±)-(2E)-Abscisic acid | C15H20O4 | 0.45 | 264.13628 | 11.376 | Terpenes | C. aeruginosa, C. xanthorrhiza |

| 32. | Helenalin | C15H18O4 | 0.55 | 262.12065 | 13.138 | Terpenes | C.aeruginosa |

| 33. | Curcumene | C15H22 | 0.61 | 202.17227 | 20.615 | Terpenes | C. aeruginosa, C. xanthorrhiza |

| 34. | (+)-Nootkatone | C15H22O | 0.79 | 218.16724 | 21.595 | Terpenes | C. xanthorrhiza |

| 35. | (E, E)-alpha-Farnesene | C15H24 | 1.53 | 204.18811 | 22.613 | Terpenes | C. xanthorrhiza |

| 36. | Pristimerin | C30H40O4 | 1.29 | 464.29326 | 26.153 | Terpenes | C. xanthorrhiza |

| 37. | 3,4-Dihydrocadalene | C15H20 | 0.97 | 200.15669 | 21.594 | Terpenes | C. xanthorrhiza |

P. niruri=Phyllanthus niruri, A. paniculata=Andrographis paniculata, C. xanthorrhiza=Curcuma xanthorrhiza, C. aeruginosa=Curcuma aeruginosa, PPM=Parts per million, MW=Molecular weight

In vitro motility analysis of the adult A. galli worm

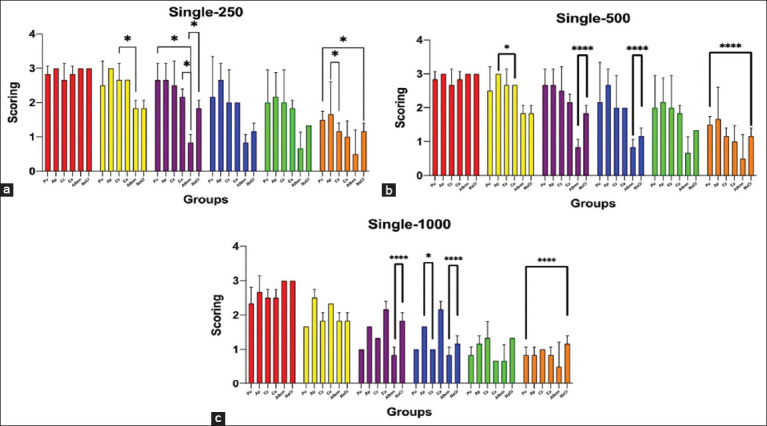

Treatment of A. galli with the ethanol extracts of A. paniculata, P. niruri L., C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb. in a single dose of 250 μg/mL, 500 μg/mL, and 1000 μg/mL revealed a different response on the motility score of A. galli from 1 to 6 h PE (Figure-2). In the 1-h PE in all tested doses of all plant extracts, including the positive and control groups, the effect of antimotility on A. galli was undetected, and all worms were still active and alive (Figure-2). In the 2-h PE, the response was mainly similar to that in the 1-h exposure, except at doses of 250 μg/mL and 500 μg/mL for C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. and A. paniculata, there was a significant difference (p < 0.05) (Figure-2a and b).

Figure-2.

In vitro assay of the ethanol extract of A. paniculata, P. niruri L., C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb. on A. galli motility in several single doses of the extracts. (a) Exposure to a single dose of 250 μg/mL, (b) Exposure to a single dose of 500 μg/mL, and (c) Exposure to a single dose of 1000 μg/mL. Pu: P. niruri L.; AP: A. paniculta; Cz: C xanthorrhiza Roxb; Ca: C. aeruginosa Roxb; Alben: Albendazole; sodium chloride (NaCl): 0.9% NaCl solution. The differences in the bar color groups indicate the different times of PE: Red: 1 h; Yellow: 2 h; Brown: 3 h; Blue: 4 h; Green: 5 h; and Orange: 6 h. The asterisk symbol indicates significant differences among the extracts within the same hour of observation (p < 0.05 = *, p < 0.01 = **, p < 0.001 = ***, p < 0.0001 = ***). A. galli=Ascaridia galli, P. niruri=Phyllanthus niruri, A. paniculata=Andrographis paniculata, C. xanthorrhiza Roxb=Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb, C. aeruginosa Roxb=Curcuma aeruginosa Roxb.

Our study found that the 250 μg/mL dose during the 1-h PE of P. niruri L., C. aeruginosa Roxb., A. paniculata, and C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. did not affect the A. galli motility (Figure-2a). However, we observed a significant decrease in A. galli motility (p < 0.05) in control, P. niruri L., and C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. groups at 2-h PE. At 3 h PE, we noted significant differences (p < 0.05) in the decreasing motility of A. galli in the positive control group compared with the negative control group and the groups of C. aeruginosa Roxb. and P. niruri L. There were no differences in the motility of A. galli in the herbal treatment groups compared with the control groups at 4 and 5 h of PE. Notably, significant differences (p < 0.05) were detected in the groups of P. niruri L. with the group of negative control and the group of A. paniculata with the group of C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. at 6 h of PE.

At a dose of 500 μg/mL in 1-h PE of all extract plants and control groups, similar results were obtained as with a dose of 250 μg/mL, where there was no inhibition of motility of A. galli (Figure-2b). At 2-h PE, there were no differences in the motility inhibition of A. galli in all extract plants and the control groups, except for A. paniculata and C. aeruginosa Roxb. (p < 0.05). Significant differences (p < 0.001) existed between the positive and negative control groups in the 3- and 4-h PE. At 5 h of PE, there were no differences in the inhibition motility of A. galli between the extract and control groups. Significant differences (p < 0.001) in decreasing motility of A. galli at the 6 h PE in the P. niruri L. and negative control groups.

In the 1000 μg/mL dose, all plant extracts significantly influenced the motility of A. galli (Figure-2c). At 1 h of PE, a decrease in A. galli motility was observed compared with the control group, although the difference was not significant. However, after 2 h of PE, A. galli motility was decreased compared with that after 1 h of PE in all extracts and control groups. At 3-h PE, the A. galli motility weakened further than that at 2 h PE, with highly significant differences (p < 0.001) in the positive and negative control groups. At 4-h PE, A. galli motility was significantly reduced in the P. niruri L. and C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. groups, with a significant difference (p < 0.05) between A. paniculata and C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. The motility of A. galli remained similar to that of 4 and 5 h of PE. At 6 h of PE, the motility of A. galli was significantly reduced in all plant extract groups and the positive and negative control groups, with significant differences (p < 0.0001) in A. galli motility in the negative control and P. niruri L. groups.

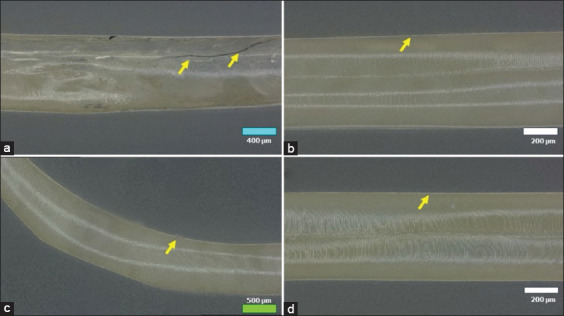

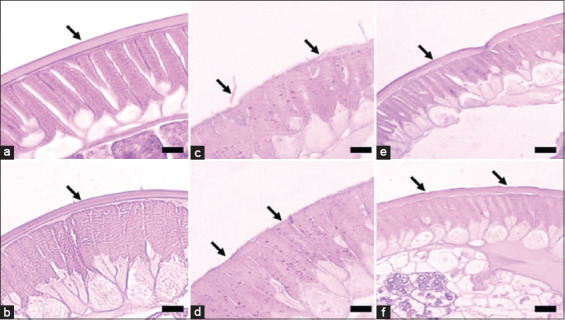

Microscopical observation

Microscopical lesions in the A. galli cuticles were detected in all plant extract groups, and all tested doses started from 2 h to 6 h PE with a gradual gradation of the lesions from the thin cuticle, irregularity of the surface, cracking cuticle wall, erosion, and desquamation of the cuticle layer. Severe lesions in the cuticle were primarily detected in 1000 μg/mL of all plant extract at the 6-h PE. The 1000 μg/mL A. paniculata and P. niruri L. extracts caused the most severe lesions in the A. galli cuticle layer. Observation using a nano-microscope revealed the cracking part of the cuticle wall caused by exposure to the 1000 μg/mL A. paniculata extract at 6 h PE, as shown in Figure-3a. The same severe lesion with desquamation and erosion of the cuticle layer of A. galli was detected on observation by histopathology assay in A. galli exposed to 1000 μg/mL A. paniculata and P. niruri L. extracts, as shown in (Figures-3a and c, 4c and d). On the other hand, there were moderate lesions of irregularity and depletion of the cuticle of A. galli following exposure to the extracts of C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. and C. aeruginosa Roxb. (Figures-3b and 3d, 4e, and f). Importantly, no lesions were found in the cuticle layer of the A. galli in the positive and negative control groups (Figures-4a and b).

Figure-3.

Photomicroscope using a nano microscope of A. galli cuticle exposed to the plant extracts with 1000 μg/mL dose during the 6-h PE. (a) Cracking cuticle layer (arrow) in the A. paniculata extract group, (b) A thin layer of A. galli cuticle (arrow) in the C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. extract group, (c) Cuticle with some desquamated and erosion (arrow) in the P. niruri L. extract group, and (d) A thin layer of A. galli cuticle (arrow) in the C. aeruginosa Roxb. extract group. Bar = 100 μm. A. galli=Ascaridia galli, P. niruri=Phyllanthus niruri, A. paniculata=Andrographis paniculata, C. xanthorrhiza Roxb=Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb, C. aeruginosa Roxb=Curcuma aeruginosa Roxb, PE=Post-exposure.

Figure-4.

Histopathological picture of the A. galli cuticle exposed to 1000 μg/mL of plant extracts at 6 h PE. (a) Normal cuticle from the negative control group; (b) Cuticle from the positive control group, similar to the negative control group; (c) Cuticle exposed to A. paniculata extract, the cuticle was desquamated, erosion, and thin with irregular surface (arrow); (d) Cuticle exposed to P. niruri L. extract, similar to the A. paniculata extract group (arrow). (e) Cuticle exposed to C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. extract, the lesions of the cuticle were thin, moderately desquamated in some parts, and irregularity of the cuticle surface (arrow); F: Cuticle exposed to C. aeruginosa Roxb. extract, the lesions were similar to the C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. extract group. Hematoxylin-Eosin staining. A. galli=Ascaridia galli, P. niruri=Phyllanthus niruri, A. paniculata=Andrographis paniculata, C. xanthorrhiza Roxb=Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb, C. aeruginosa Roxb=Curcuma aeruginosa Roxb, PE=Post-exposure.

Discussion

Ascaridiasis, a prevalent and noteworthy poultry disease, is caused by the soil-transmitted helminth A. galli (Schrank, 1788), which is the largest nematode in chickens and the most frequently encountered problem in indigenous chickens [12]. A. galli infection involves a thickened intestinal wall with petechial hemorrhage, edema, and infiltration of lymphoid cells mixed with eosinophils [13]. The intestinal epithelium acts as a communication network for this gut-dwelling nematode; thus, gastrointestinal nematode infection could cause damage to the mucosal epithelial cells of the chicken’s digestive tract and increased mucus production, leading to desquamation, adhesion of mucous villi, epithelial cell necrosis, and goblet cell hyperplasia [14, 15]. A. galli infection not only results in problems with nutrient absorption but also has complex immunomodulatory effects that can alter the host’s immune response to the disease [16].

The results of this study revealed the potential of herbal plant extracts as treatments for A. galli. It was found that increasing the single extract dose and observation time significantly affected A. galli motility. The active compounds from P. niruri L. extract, such as flavonoids, alkaloids (phyllanthin), coumarin (linamarin), lignans (5-Methoxybenzimidazole), and phenolics (zingerol), appear to cause A. galli cuticles to desquamate and erosion, resulting in the cuticle becoming thin with an irregular surface, which influences the weakening of A. galli motility. It is worth noting that Oxfendazole, an anthelmintic derivative of Benzimidazole [17], remains a highly effective treatment for A. galli [18], providing reassurance in the fight against this parasite. Furthermore, the metabolite of A. paniculata containing the terpenoid Andrographolide can damage and cause desquamation and erosion of the cuticle layer, resulting in an irregular surface and decreased A. galli motility. The results of another study stated that Thymoquinone, the main terpenoid compound in black cumin seed (Nigella sativa), has an anthelmintic strong activity in reducing the motility of A. galli and damages the tegument of Paramphistomum spp. [19, 20]. Further, the phenolic curcumin and terpenoid alantolactone metabolite compounds from C. xanthorrhiza Roxb. and C. aeruginosa Roxb. extracts caused the cuticle to become thin, slightly desquamate, and irregular, inhibiting A. galli motility. Another study by Mubarokah et al. [21] reported that tannin and saponin in Areca catechu crude aqueous extract cause morphological changes in adult A. galli.

The role of secondary metabolites of herbal plants with anthelmintic activity, such as terpenes (glycosides and saponins), phenolics (alkaloids and tannins), and nitrogen content (alkaloids, cyanogenic glycosides, and non-protein amino acids), is fascinating due to their diverse mechanisms. These mechanisms include damaging the worm’s mucopolysaccharide membrane, which affects the worm’s active movement, inhibiting the worm’s fecundity, and damaging the worm’s cuticle [22]. It is understandable that the cuticle is the main target for deworming. The nematode cuticle, a complex extracellular structure, is metabolically active and morphologically varies between the genera of worms, larvae, and adults. It consists of three parts, with many layers containing glycoproteins and lipids. However, specific collagen and insoluble protein (cuticlin) truly define the nematode cuticle. These two components, which are rich in the cuticle, are crucial in structure and function. The epicuticle, which forms the cuticle’s outermost layer, also contains insoluble proteins. The middle layer of the cuticle is the matrix divided into a fibril layer containing aromatic amino acids and a thick homogeneous layer consisting of albumin protein and fibrous proteins resembling fibrin or elastin, as well as carbohydrates, lipids, and esterase enzymes [23].

Previous studies [4, 5, 21, 24, 25] have been conducted on the effects of medicinal plants on poultry worms. Clove leaf extract (Syzygium aromaticum) was reported to change the surface and damage the cuticle of A. galli, resulting in the death of A. galli at 3, 6, and 9 h after exposure to 140 mg/mL of the clove leaf ethanol extract [26]. At a dose of 100 mg/mL, the ethanol extract of Juglans regia L. leaves inhibited the motility of adult A. galli by 96.5% 24 h after exposure [5]. The ethanol extract of black cumin seeds at a concentration of 45% can kill A. galli in 10 h [20]. The water extract of Areca catechu can cause morphological changes and result in the death of A. galli [21]. Nyctanthes arbor-tristis and Butea monosperma leaf extracts have significant in vivo anthelmintic activity against A. galli [24]. Mimosa pudica leaf ethanol extract and Carica papaya seed extract were also reported to reduce egg per gram feces and affect blood and fat parameters in Kabir chickens infected with A. galli in Cameroon [25]. Anthelmintic effects were observed at a 20% Jatropha curcas Linn leaf extract concentration against A. galli [27]. The crude methanol extract of Saussurea costus inhibits worm motility inhibition in A. galli at 100 mg/mL after 24 h of exposure [4]. In addition to anthelmintic activity against gastrointestinal parasitic infections, anti-protozoan activity against gastrointestinal protozoan parasitic infections has been reported. Curcumin, a polyphenol from turmeric (Curcuma spp.), has been known to have anti-coccidial effects [28]. Curcumin is also known to have anti-malarial activity [29].

Various worm medicines such as Albendazole, Piperazine, Levamisole, and Ivermectin are often used to control A. galli. The use of anthelmintics for an extended period can result in worm resistance. Some researchers have proven that fenbendazole is resistant to Ascaridia dissimilis, a digestive tract worm in turkey [30]. Since a vaccine for digestive tract worms, especially A. galli has not yet been developed, the worm control program has been based only on administering worm medicine. This study proposes a control approach for the ethanol extracts of A. paniculata, P. niruri L., C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb. as medicinal plants with anthelmintic activity against A. galli. The use of herbal plant-based anthelmintics in chickens can significantly impact parasitology by reducing the development of anthelmintic resistance. Furthermore, the need for in vivo studies to assess the efficacy of A. paniculata, P. niruri L., C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb. as anthelmintics in chickens infected with A. galli is paramount. These studies will provide valuable insights into the effects of these medicinal plants in natural infection, enhancing our understanding of their potential as anthelmintics. This research is necessary and interesting as it will serve as a reference for future in vivo studies using chickens and guide us toward more effective worm disease control strategies.

Conclusion

The ethanol extracts of A. paniculata, P. niruri L., C. xanthorrhiza Roxb., and C. aeruginosa Roxb. have shown promising anthelmintic activity at a concentration of 1000 μg/mL. Notably, the extracts of A. paniculata and P. niruri L. at this concentration exhibit intense anthelmintic activity, damaging and dissolving the cuticle layer of A. galli, thereby weakening the ability of adult A. galli to move. These findings hold great potential for the development of novel anthelmintic treatments.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Directorate of Research and Innovation, IPB University, Indonesia, for the grant of research funding through the Competitive Fundamental Research to RT and LNS (Grant No. 450/IT3.D10/PT.01.03/P/B/2023). The authors also thank the Tropical Biopharmaca Research Center IPB University for providing and processing the plant extracts and also the Laboratory Unit of IPB University Advanced Research Center for the metabolomic and nano microscopic analysis.

Author’s Contributions

RT: Designed and conducted the study. LNS: Prepared and analyzed the herb extracts. ABN: Analyzed the data. MS: Prepared and analyzed histopathological samples. RT, LNS, ABN, and MS: Performed data collection, statistical analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. RT and LNS: Supervised the study and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Veterinary World remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

References

- 1.Höglund J, Daş G, Tarbiat B, Geldhof P, Jansson D.S, Gauly M. Ascaridia galli - An old problem that requires new solutions. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs. Drug Resist. 2023;23:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2023.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma N, Hunt P.W, Hine B.C, Ruhnke I. The impacts of Ascaridia galli on performance, health, and immune responses of laying hens:New insights into an old problem. Poult. Sci. 2019;98(12):6517–6526. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shohana N.N, Rony S.A, Ali M.H, Hossain M.S, Labony S.S, Dey A.R, Farjana T, Alam M.Z, Alim M.A, Anisuzzaman Ascaridia galli infection in chicken:Pathobiology and immunological orchestra. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2023;11:e10011. doi: 10.1002/iid3.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mir F.H, Tanveer S, Bharti P, Para B.A. Anthelmintic activity of Saussurea costus (Falc.) against Ascaridia galli, a pathogenic nematode in poultry:in vitro and in vivo studies. Acta Parasitol. 2024a;69(2):1192–1200. doi: 10.1007/s11686-024-00837-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mir F.H, Tanveer S, Para B.A. Evaluation of anthelmintic efficacy of ethanolic leaf extract of Juglans regia L on Ascaridia galli:A comprehensive in vitro and in vivo study. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024b;48(4):2321–2330. doi: 10.1007/s11259-024-10411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poudel D.K, Ojha P.K, Rokaya A, Satyal R, Satyal P, Setzer W.N. Analysis of volatile constituents in Curcuma species, viz C. Aeruginosa, C. zedoaria and C. Longa, from Nepal. Plants (Basel) 2022;11(15):1932. doi: 10.3390/plants11151932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Priosoeryanto B.P, Rostantinata R, Harlina E, Nurcholis W, Ridho R, Sutardi L.N. In vitro antiproliferation activity of Typhonium flagelliforme leaves ethanol extract and its combination with canine interferons on several tumor-derived cell lines. Vet. World. 2020;13(5):931–939. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2020.931-939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Indonesian Health Ministry. Indonesian Herbal Pharmacopoeia. 2nd ed. Jakarta: Indonesian Health Ministry; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mumed H.S, Nigussie D.R, Musa K.S, Demissie A.A. In vitro anthelmintic activity and phytochemical screening of crude extracts of three medicinal plants against Haemonchus contortus in sheep at Haramaya Municipal Abattoir, Eastern Hararghe. J. Parasitol. Res. 2022;2022:6331740. doi: 10.1155/2022/6331740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva L.P, Debiage R.R, Bronzel-Junior J.L, da Silva R.M.G, Mello-Peixoto E.C.T. In vitro anthelmintic activity of Psidium guajava hydroalcoholic extract against gastro-intestinal sheep nematodes. An. Acad. Bras. Sci. 2020;92(Supp 2):e20190074. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765202020190074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hambal M, Efriyendi R, Vanda H, Rusli R. Anatomical pathology and histopathological changes of Ascaridia galli in layer chicken. J. Med. Vet. 2019;13(2):239–247. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shifaw A, Feyera T, Walkden-Brown S.W, Sharpe B, Elliott T, Ruhnke I. Global and regional prevalence of helminth infection in chickens over time:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Poult. Sci. 2021;100(5):101082. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levkut M, Levkutová M, Grešáková Ľ, Bobíková K, Revajová V, Dvorožňáková E, Ševčíková Z, Herich R, Karaffová V, Žitňan R, Levkut M. Production of intestinal mucins, sIgA, and metallothionein after administration of zinc and infection of Ascaridia galli in chickens:Preliminary data. Life. 2022;13(1) doi: 10.3390/life13010067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jerica M.S, Tiuria R, Mayasari N.L.P.I, Nugraha A.B, Subangkit M. Goblet cell hypertrophy in small intestine of free-range chicken in Jakarta traditional market with cestode worms. Curr. Biomed. 2024;2(2):93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritu S.N, Labony S.S, Hossain M.S, Ali M.H, Hasan M.M, Nadia N, Shirin A, Islam A, Shohana N.N, Alam M.M, Dey A.R, Alim M.A, Anisuzzaman Ascaridia galli, a common nematode in semi scavenging indigenous chickens in Bangladesh:Epidemiology, genetic diversity, pathobiology, ex vivo culture, and anthelmintic efficacy. Poult. Sci. 2024;103(3):103405. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.103405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das G, Aurbach M, Stehr M, Surie C, Metges C.C, Gauly M, Rautenschlein S. Impact of nematode infections on non-specific and vaccine-induced humoral immunity in dual purpose or layer-type chicken genotypes. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021;8:659959. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.659959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebenezer O, Joshua F.E, Omotoso O.D, Shapi M. Benzimidazole and its derivates:Recent advances (2020–2022) Res. Chem. 2023;5(3):100925. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feyera T, Sharpe B, Elliott T, Shifaw A.Y, Ruhnke I, Walkden-Brown S.W. Anthelmintic efficacy evaluation against different developmental stages of Ascaridia galli following individual or group administration in artificially trickle-infected chickens. Vet. Parasitol. 2022;301:109636. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2021.109636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hambal M, Vanda H, Ayuti S.R. Nigella sativa seed extract affected tegument and internal organs of trematode Paramphistomum cervi. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2021;9(4):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanda H, Abadi A.K, Hambal M, Athailah F, Sari W.E, Frengki F, Daniel D. Black cumin seed ethanol extract decrease motility and shortening mortality time of Ascaridia galli worm in vitro. J. Vet. 2023;24(1):63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mubarokah W.M, Nurcahyo W, Prastowo J, Kurniasih K. In vitro and in vivo Areca catechu crude aqueous extract as an anthelmintic against Ascaridia galli infection in chickens. Vet. World. 2019;12(6):877–882. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2019.877-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaman M.A, Qamar M.F, Abbas R.Z, Mehreen U, Qamar W, Shahid Z, Kamran M. Role of secondary metabolites of medicinal plants against Ascaridia galli. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2020;76(3):639–655. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betschart B, Bisoffi M, Alaeddine F. Identification and characterization of epicuticular proteins of nematodes sharing motifs with cuticular proteins of arthropods. PLoS One. 2022;17(10):e0274751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hazarika A, Debnath S, Sarma J, Deka D. Evaluation of in vivo anthelmintic efficacy of certain indigenous plants against experimentally-induced Ascaridia galli infection in local birds (Gallus domesticus) Exp. Parasitol. 2023;247:108476. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2023.108476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nghonjuyi N.W, Keambou C.T, Sofeu-Feugaing D.D, Taiwe G.S, Aziz A.R.A, Lisita F, Juliano R.S, Kimbi H.K. Mimosa pudica and Carica papaya extracts on Ascaridia galli - experimentally infected Kabir chicks in Cameroon:Efficacy, lipid and hematological profile. Vet. Parasitol. 2020;19:100354. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2019.100354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anggrahini S, Widiyono I, Indarjulianto S, Prastowo J. In vitro anthelmintic activity of clove-leaf extract (Syzygium aromaticum) against Ascaridia galli. Livestock Res. Rural Develop. 2021;33(7):91. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ainun H, Ris A, Amir M.N, Jamaluddin A.W. Anthelmintic activity of Jatropha (Jatropha curcas linn) leaf against Ascaridia galli worms in vitro. J. Indones. Vet. Res. 2022;6(1):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geevarghese A.V, Kasmani F.B, Dolatyabi S. Curcumin and curcumin nanoparticles counteract the biological and managemental stressor in poultry production:An updated review. Res. Vet. Sci. 2023;162:104958. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2023.104958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotha R.R, Luthria D.L. Curcumin:Biological, pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and analytical aspects. Molecules. 2019;24(16) doi: 10.3390/molecules24162930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins J.B, Jordan B, Baldwin L, Hebron C, Paras K, Vidyashankar A.N, Kaplan R.M. Resistance to fenbendazole in Ascaridia dissimilis, an important nematode parasite of turkeys. Poult. Sci. 2019;98(11):5412–5415. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]