Highlights

-

•

Electronic Health Literacy (EHL) among U.S. adults with diabetes rose from 35.3% in 2011 to 46.8% by 2018, yet disparities remained.

-

•

National trends show persistent EHL gaps across age, race, income, and language proficiency groups.

-

•

Older adults and minority groups are most affected by limited EHL, hindering their ability to benefit from digital health tools.

-

•

Insights on reducing disparities in digital health access for diabetes care.

Keywords: Electronic Health Literary, Social Determinants of Health, Diabetes Mellitus, Digital Health, National Health Interview Survey

Abstract

Background

Digital health technologies hold promises for enhancing healthcare and self-management in diabetes. However, disparities in Electronic Health Literacy (EHL) exist among diabetes populations. This study investigates EHL trends and demographic differences among adults with diabetes in the United States from 2011 to 2018.

Methods

We analyzed data from the 2011–2018 National Health Interview Study (NHIS) on 27,096 adults with diabetes. The primary outcome was EHL, determined by responses to internet usage questions. Trends in EHL were assessed using the Rao Scott Chi-Square Test. Multivariate logistic regression was used to investigate the association between EHL and various comorbidities, socioeconomic and demographic subgroups.

Results

Analytic sample (N = 27,096) represents 10.6 million adults (mean age 62.3, 52.5 % Females) in the USA surveyed between 2011 and 2018. The mean rate of EHL was 38.9 % and trended upward from 35.3 % to 46.8 % over the 2011–2018 period. In a fully adjusted logistic regression model, multiple socioeconomic factors were associated with EHL. Age was inversely associated with odds of EHL (aOR 0.95, 95 % CI: 0.95–0.95). Black individuals had lower odds of EHL compared to Whites (aOR 0.63, 95 % CI: 0.56–0.71). Low-income (<100 % and 100–200 % of federal poverty limit) were negatively associated with EHL. Furthermore, limited English proficiency was associated with lower odds of EHL (aOR 0.29, 95 % CI: 0.22–0.38).

Conclusion

The study identified ongoing disparities in EHL among adults with diabetes based on age, race/ethnicity, income, and language proficiency, highlighting the need for targeted interventions to improve digital health access for all.

1. Introduction

DM mellitus (DM) is an important public health issue, affecting an estimated 37.3 million people in the United States (Cdc, 2022). Poor DM control has been associated with greater complications, higher healthcare costs (Mata-Cases et al., 2020), and population-level loss of productivity (Magliano et al., 2018). Despite advances in DM therapeutics, recent evidence suggests that glycemic control in the US population is stagnating, and that racial and ethnic disparities are widening (Venkatraman et al., 2022, Wang et al., 2021, Fang et al., 2021).

The advent of digital health technologies offers the potential for improved DM care through patient empowerment, education, and remote monitoring (Shan et al., 2019). A prior study found that a DM education program delivered via text message improved glycemic control over six months (Fortmann et al., Oct 2017). “Furthermore, a meta-analysis of randomized studies found that telemedicine improved glycemic control in patients with DM compared to usual care, which typically involves standard in-person visits and traditional management without digital interventions (Hu et al., Aug 2019). These findings underscore the potential benefits of digital health interventions in diabetes management, making it a pertinent focus for our study.”

However, the ability to appropriately utilize these technologies is dependent on an individual’s electronic health literacy (EHL), which has been defined as the “ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from electronic sources and apply the knowledge gained to addressing or solving a health problem.” (Norman and Skinner, 2006) Indeed, as healthcare becomes increasingly digital (Norman and Skinner, 2006), EHL will become essential for an individual to navigate the vast realm of online health information, make informed decisions, and participate in managing their own health (Rhee et al., Dec 2020). EHL plays a crucial role in improving healthcare quality, reducing disparities, empowering patients, and facilitating informed decision-making and self-management. These benefits underscore the importance of promoting and enhancing electronic health literacy in both research and practice.

Social determinants of health (SDOH), including socioeconomic status, education, and language proficiency, have been associated with an individual's health outcomes and access to healthcare services. Additionally, demographic characteristics such as race/ethnicity play a critical role in understanding disparities in electronic health literacy (EHL) (Hill-Briggs et al., 2020). Recent studies have found that despite digital health utilization increasing from 2011 to 2018, disparities were observed across demographic and other SDOH domains (Mahajan et al., 2021). EHL and internet connectivity have been considered “super social determinants of health” due to their significant impact on individuals' access to health information and services (van Kessel et al., Mar 2022). It is worth noting that individuals facing worse SDOH conditions, especially those with DM, consistently exhibit poorer health behaviors, higher healthcare utilization, and adverse health outcomes (Hill-Briggs et al., Mar 2022, Hill-Briggs et al., 2020, Hill-Briggs and Fitzpatrick, 2023, Levy et al., 2022/10/12 2022;).

Despite the high prevalence of DM and increasing utilization of digital health technology, little is known about EHL among patients with DM. Given the increasing utilization of digital health technologies in the management of DM, we conducted this study to examine trends in EHL among US adults with DM from 2011 to 2018 and to investigate disparities across SDOH and demographic subgroups (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Central Illustration of Study Methodology, Step 1: Pre-processing of National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data to create a cohort of subjects with diabetes mellitus (DM). Step 2: Calculation of Electronic Health Literacy (EHL), defined as a positive response to using the internet for any of the following: looking up health information, filling a prescription, scheduling an appointment, or communicating with a health provider via email. Step 3: Analysis and interpretation of EHL trends across various social determinants of health (SDOH) and demographic subgroups among subjects with DM.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

We used publicly available data from the 2011 – 2018 National Health Interview Study (NHIS) (CDC). This is a nationally representative, annual cross-sectional survey that captures data on demographic, socioeconomic, and health characteristics of the civilian, non-institutionalized population of the United States. We used 2011 – 2018 data because they contained our variables of interest and were not affected by data collection concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.2. Study population and sample Selection

The initial NHIS dataset included a total sample of 563,544 adults aged 18 years and older. To focus on individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM), we excluded all respondents without a self-reported diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes was defined as a self-reported history of being told by a doctor or other health practitioner that they had DM. We extracted patient demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), socioeconomic characteristics (education, limited English proficiency, income), and self-reported medical comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma, cancer, hypertension, and arthritis).

2.3. Variables

Our primary outcome of interest was EHL, defined as a positive answer to any of the following questions, “Did you use the internet to look up health information?”, “Did you use the internet to fill a prescription?”, “Did you schedule an appointment on the internet?”, and “Did you communicate with a health provider using email?” as shown in Fig. 1.

Race/ethnicity was categorized into Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic Other, and Hispanic. Income groups were defined as < 100 % federal poverty limit (FPL), 100–200 % FPL, and > 200 % FPL. Limited English proficiency was reported as responding “Not well” or “Not at all” to the question “How well is English spoken?”. Notably, limited English proficiency (LEP) was not obtained in the 2011 or 2012 NHIS surveys.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We compared patient characteristics based on EHL status. We explored population trends of EHL between 2011–2018. We assessed trends in EHL across age, race, income, and English proficiency groups using the Rao Scott Chi-Square Test. We conducted a multivariable logistic regression evaluating the association of patient sociodemographic characteristics and odds of having EHL, after adjusting for years of survey and medical comorbidities. Interaction analyses were conducted to evaluate whether the association of age, race/ethnicity, income, and English proficiency with EHL were modified by the survey year. All analyses were conducted in SAS v9.4 and accounted for complex survey weighting and variance estimation. Figures were made in GraphPad Prism v10.1.1.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was deemed exempt from the UT Southwestern institutional review board due to the de-identified and publicly available nature of the data.

3. Results

3.1. Population characteristics

The initial sample from the NHIS dataset included 563,544 adults aged 18 years and older. After excluding all respondents without a self-reported diagnosis of diabetes, the final analytical sample comprised 27,096 adults, representing 10.6 million adults (mean age 62.3, 52.5 % Female) in the United States with DM, surveyed between 2011 and 2018 (Table 1). The sample was 63.3 % Non-Hispanic White, 16.3 % Non-Hispanic Black, 6.6 % Non-Hispanic Other Race, and 8.8 % Hispanic. About one in five (21 %) had an education level below high school and one in six (18.9 %) had incomes below 100 % of the Federal Poverty Limit. LEP was reported by 7.1 % of the sample. Myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke were reported in 22.3 % and 9.9 % of the sample, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Clinical Characteristics of U.S. Adults with Diabetes by Electronic Health Literacy (EHL) Status (2011–2018).

|

Full Sample (N = 27,096) |

Electronic Health Literacy (n = 9,958) | Low Electronic Health Literacy (n = 17,138) | P-Values* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 62.3 (0.1) | 57.8(0.2) | 65.2(0.1) | <0.0001 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 12,629 (47.5) | 4609 (47.3) | 8020 (47.6) | 0.7513 |

| Female | 14,467 (52.5) | 5349 (52.7) | 9118 (52.4) | |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 15,791 (63.3) | 6862 (72) | 8929 (57.6) | <0.0001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4943 (16.3) | 1384 (12.7) | 3559 (18.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 2071 (6.6) | 739 (6.5) | 1332 (6.7) | |

| Hispanic | 4235 (13.8) | 948 (8.8) | 3287 (17.1) | |

| Income/Poverty, n (%) | ||||

| <100 % Federal poverty limit | 5106 (18.9) | 1070 (10.8) | 4036 (24.4) | <0.0001 |

| 100–200 % FPL | 6207 (23.9) | 1606 (16.5) | 4601 (28.8) | |

| 200+% FPL | 13,834 (57.2) | 6793 (72.8) | 7041 (46.8) | |

| English Proficiency+, n (%) | ||||

| English Proficiency | 17,206 (92.9) | 7120 (98.5) | 10,086 (88.9) | <0.0001 |

| Limited English Proficiency (LEP) | 1415 (7.1) | 112 (1.5) | 1303 (11.1) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| Less than High school education | 6119 (21) | 627 (6.1) | 5492 (30.6) | <0.0001 |

| High School Education and Some College | 12,735 (47.6) | 4490 (53.5) | 8245 (49.3) | |

| College Graduate or Higher | 8089 (31.4) | 4825 (40.4) | 3264 (20) | |

| Marital Status, n (%) | ||||

| Married | 12,570 (46.8) | 5378 (54.2) | 7192 (42) | <0.0001 |

| Widowed /Separated | 10,965 (40.1) | 3149 (31.3) | 7816 (45.8) | |

| Single/Never Married | 3512 (13.1) | 1411 (14.6) | 2101 (12.2) | |

| CV Risk Factors, n (%) | ||||

| Myocardial Infarction | 6096 (22.3) | 1808 (18.1) | 4288 (25.1) | <0.0001 |

| Stroke | 2690 (9.9) | 666 (6.9) | 2024 (11.9) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 20,028 (73.2) | 6957 (69.3) | 13,071 (75.7) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 9716 (35.9) | 3070 (30.9) | 6646 (39.1) | <0.0001 |

| Cancer | 4591 (17.4) | 1724 (17.6) | 2867 (17.2) | 0.4704 |

| Arthritis | 13,361 (49.5) | 4762 (47.9) | 8599 (50.5) | 0.0002 |

| COPD/Asthma | 6144 (22.6) | 2406 (23.8) | 3738 (21.8) | 0.001 |

Statistical significance for differences between groups was assessed using T-tests for continuous variables and Chi-squared tests for categorical variables.

Limited English Proficiency (LEP) was reported by those responding, “Not well” or “Not at all” to the question “How well is English spoken?”

There were significant sociodemographic differences between individuals with and without EHL. Compared to individuals without EHL, individuals with EHL were more likely to be White race (72 % vs. 57.6 %), have incomes > 200 % FPL (72.8 % vs 46.8 %), have greater English proficiency (98.5 % vs 88.9 %) have attained college education or greater (40.4 % vs 20.0 %), and be married (54.2 % vs 42.0 %) (P < 0.0001 for all). Individuals with EHL were less likely to have prevalent myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, hypertension, malignancy, and arthritis than individuals without EHL (Table1).

3.2. National trends in EHL among patients with DM

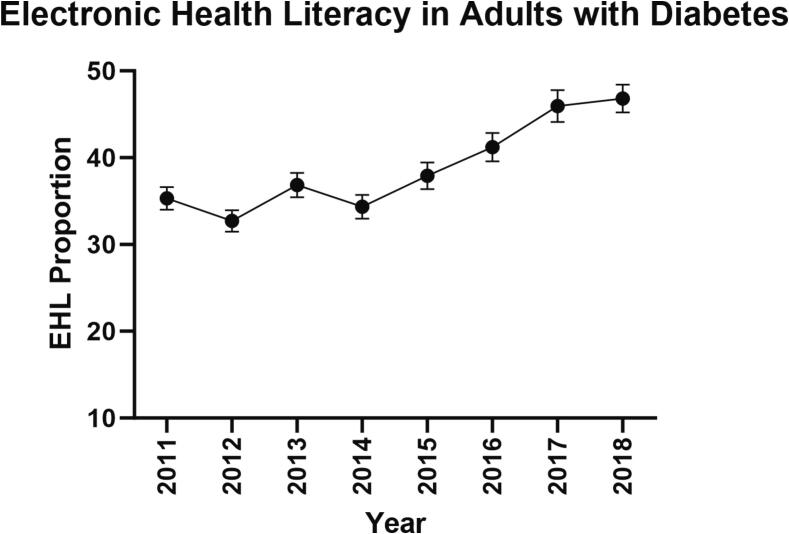

Over the study period from 2011 to 2018, observed mean EHL was 38.8 %, and EHL increased from 35.3 % in 2011 to 46.8 % in 2018 (Fig. 2). Initially, between 2011 and 2014, the EHL rate remained within a range of 35 % to 40 % but has continuously increased after 2014.

Fig. 2.

Overall Trend in Electronic Health Literacy in Adults with DM.

3.3. National trends among patients with DM by patient Subgroup

The EHL trends varied across different demographic groups. (Fig. 3) Throughout the study period, the younger population consistently had higher EHL rates compared to the older age population (age > 65 years). Over time, the difference in EHL between older age and younger population remained stable. EHL increased from 46.0 % in 2011 to 59.5 % in 2018 among young adults, while it rose from 21.9 % in 2011 to 34.0 % in 2018 among older adults (Fig. 3A). Differences were also observed between racial-ethnic groups. Non-Hispanic whites had the highest mean EHL rate at 44.3 %, followed by adults of non-Hispanic other races at 37.6 %, non-Hispanic black adults at 30.5 %, and Hispanic adults at 24.3 %. Between 2011 and 2018, absolute EHL rates increased by 15.6 % for Hispanic adults (21.2 % to 36.9 %), 12.6 % for Non-Hispanic Whites (40.1 % to 52.7 %), 11.1 % for Non-Hispanic Other Race (32.7 % to 43.8 %) and 7.6 % for Non-Hispanic Blacks (27.5 % to 35.1 %) as shown in Fig. 3B. Furthermore, EHL increased across all three income groups over time. The mean prevalence of EHL was highest in the > 200 %+ FPL group at 50.6 % but remained lower at 22.7 % in < 100 % FPL and 27.4 % in 100–200 % FPL groups (Fig. 3C). Striking differences were noted in EHL when stratified by LEP. Among those with LEP, EHL was 5.6 % in 2013 and 11.0 % in 2018. In contrast, EHL among individuals with English proficiency increased from 37.3 % in 2013 to 49.5 % in 2018 (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Trends in Electronic Health Literacy Among Adults with Diabetes Mellitus (DM) in the United States from 2011 to 2018. A: Proportion of Electronic Health Literacy by Age Group (Older Adults > 65 Years vs. Younger Adults ≤ 65 Years). B: Proportion of Electronic Health Literacy by Race/Ethnicity (White, Black, Other Race, Hispanic). C: Proportion of Electronic Health Literacy by Income Levels (<100 % Federal Poverty Limit [FPL], 100–200 % FPL, >200 % FPL). D: Proportion of Electronic Health Literacy by English Proficiency (Limited vs. Proficient English Speakers).

3.4. Predictors of EHL in patients with DM

In a fully adjusted logistic regression model, multiple socioeconomic factors were associated with EHL (Table 2). We observed that each additional year of age was associated with 4.8 % lower odds of EHL (aOR 0.95, 95 % CI [0.95–0.95], P < 0.0001). Furthermore, we observed that compared to the non-Hispanic White group, all other race/ethnic minority groups were far less likely to have EHL (Black aOR 0.63 95 % CI [0.56–0.71], Non-Hispanic Other Race aOR 0.69 95 % CI [0.58–0.83], Hispanic aOR 0.74 95 % CI [0.63–0.87], P < 0.0001 for all). Odds of EHL decreased in a graded fashion with decreasing educational attainment (High school or some college aOR 0.41 [0.38–0.45], Less than high school aOR 0.15 95 % CI [0.13–0.17], P < 0.0001 for all) and decreasing income (100–200 % FPL aOR 0.54 95 % CI [0.48–0.60], <100 % FPL aOR 0.41 95 % CI [0.36–0.47], P < 0.0001 for all). Limited English proficiency was associated 71.3 % lower odds of having EHL (aOR 0.29 95 % CI [0.22–0.38], P < 0.001). Each subsequent year was associated with 14.7 % higher odds in EHL (aOR 1.15, 95 % CI [1.12–1.18], P < 0.0001). Except for cardiovascular disease, prevalent comorbidities such as hypertension, arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer were all associated with higher odds of EHL. No significant interaction was observed between survey year and age (P = 0.21), LEP (P = 0.56), income level (P = 0.12), race/ethnicity (P = 0.57), and education level (P = 0.07), with respect to the probability of having EHL.

Table 2.

Adjusted Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Associated with Electronic Health Literacy (EHL) in U.S. Adults with Diabetes Mellitus (DM) from 2011 to 2018.

| Factors | Adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR, 95 % CI) | P-value (P) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.95 (0.95–0.95) | <0.0001 |

| Female Sex (Ref1: Male) | 1.26 (1.16−1.37) | <0.0001 |

| Race/Ethnicity (Ref: White) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.63 (0.56–0.71) | <0.0001 |

| Non-Hispanic Other Race | 0.69 (0.58–0.83) | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 0.74 (0.63–0.87) | 0.0002 |

| Educational Attainment (Ref: College Graduate or Higher) | ||

| Less than High School | 0.15 (0.13–0.17) | <0.0001 |

| High School Graduate and/or Some college | 0.41 (0.38–0.45) | <0.0001 |

| Marital Status (Ref: married) | ||

| Widowed or divorced | 0.80 (0.73–0.88) | <0.0001 |

| Single, Never Married | 0.76 (0.66–0.87) | 0.0002 |

| Income to Federal Poverty Limit Ratio (Ref: >200 %) | ||

| <100 % | 0.41 (0.36–0.47) | <0.0001 |

| 100–200 % | 0.54 (0.48–0.60) | <0.0001 |

| English Proficiency (Ref: Proficient) | ||

| Limited Proficiency | 0.29 (0.22–0.38) | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| CVD | 0.95 (0.87–1.04) | 0.2651 |

| Hypertension | 1.15 (1.04–1.27) | 0.007 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease or Asthma | 1.21 (1.1–1.33) | 0.0002 |

| Cancer | 1.28 (1.14–1.43) | <0.0001 |

| Arthritis | 1.27 (1.17–1.38) | <0.0001 |

| Year of Survey Administration, per 1-year increment | 1.15 (1.12–1.18) | <0.0001 |

1Reference groups (Ref) for categorical variables are indicated.

4. Discussion

In this nationally representative cohort of individuals with DM, we report trends in EHL over time and across patient demographics. We find that EHL has continued to increase between 2011 and 2018. However, we observed significant differences across age, race/ethnic, income, and English proficiency subgroups, with patients of older age, non-White race, and low English proficiency having less EHL. Furthermore, we observed that the EHL across sociodemographic characteristics remained relatively constant over time. As digital health continues to grow, these findings reveal persistent disparities in EHL and highlight the need to ensure digital health is equitably accessible.

Integration of digital health into DM care has provided notable improvements in patient outcomes and education. Telehealth, for example, enables remote management of diabetes patients, with studies showing its effectiveness in improving glycemic control, particularly among Black and Hispanic patients (Anderson et al., Dec 2022). Digital diabetes management tools, including continuous glucose monitors and mobile apps, enhance self-care and health outcomes (Huang et al., 2023). Diabetes-specific mobile health apps have demonstrated significant reductions in HbA1c levels across various diabetes types, including prediabetes (Stevens et al., 2022). However, the ability to benefit from these technologies is contingent on adequate EHL. A joint review by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) confirmed the benefits of digital health applications in diabetes care, such as improved glycemic control, increased patient engagement, and potential cost reductions. Yet, the review highlighted that digital literacy is a significant barrier hindering the full potential of these technologies, along with issues of accessibility and integration into current healthcare systems (Fleming et al., 2020). Studies show that patients with higher EHL are more likely to effectively use diabetes management apps and tools and engage in telehealth consultations. Guo et al. found that patients with higher levels of EHL were more proficient in using these digital tools (Guo et al., 2021). Similarly, Wong et al. demonstrated that eHealth literacy and perceived social support are key factors predicting self-care behaviors among homebound older adults (Wong et al., May 2022). Kim et al. found that EHL is significantly positively correlated with various health-related behaviors, including self-management, medication adherence, disease management, and preventive actions. Health-promoting activities showed the strongest correlation with EHL (Kim et al., 2023). These findings highlight that adequate eHealth literacy is indeed crucial for patients to fully benefit from digital health technologies in diabetes management. Patients with higher EHL are better equipped to navigate digital platforms, interpret health data, and make informed decisions based on the information provided by these technologies. Our findings highlight significant disparities in EHL among older adults, racial/ethnic minorities, lower-income individuals, and those with limited English proficiency, suggesting that targeted interventions are needed to bridge these gaps and ensure equitable access to digital health resources.“.

Our study adds to the existing DM digital health literature by describing the growing rates of EHL from 2011 to 2018 and highlighting ongoing areas for improvement. Older individuals with DM displayed significantly lower odds of having EHL compared to younger individuals. This is consistent with previously published literature which has shown gaps in digital access among older adults (Chesser et al., 2016). For example, one study in Texas found that adults over 60 years were half as likely to use the internet than younger adults (Choi and Dinitto, 2013). Successful efforts have been made by the NIH to address these disparities through an eHealth online computer training program aimed at improving older adults' ability to seek, find, and understand health information from these websites (Xie, 2012). As the average age of the US population continues to increase, continued efforts will be needed to ensure that digital health technologies remain accessible to older age patients.

Furthermore, race/ethnicity was identified as a factor associated with variations in EHL. Non-Hispanic White patients had the highest EHL rate, compared to other minoritized race/ethnicity groups. The findings align with literature which demonstrate that older patients of racial and ethnic minorities are less likely than Whites to use certain technologies when managing their health (Estacio et al., 2019, Azzopardi-Muscat and Sørensen, 2019). Patients who were Hispanic had a 41 % lower chance of having a telehealth visit than White patients who were not Hispanic (Estacio et al., 2019). Additionally, limited English proficiency was found to be associated with lower EHL rates. Individuals with limited English proficiency were less likely to possess EHL compared to those with English proficiency. These racial and language proficiency disparity emphasizes the importance of considering cultural and linguistic factors in promoting equitable access to digital health information and services (Azzopardi-Muscat and Sørensen, 2019, Wang and Luan, 2022). The income level also showed a significant association with EHL, with higher income groups demonstrating higher rates of EHL. Overall, these disparities are a result of lessor use of digital health tools by older adults, lower awareness of electronic tools among vulnerable SDOH and demographic subgroups with possible inadequate access to computers and internet which are not as easy to be used by non-English speakers. This finding suggests that socioeconomic factors play a role in determining EHL levels, potentially creating disparities in access to digital health resources and benefits. A vast majority of literature reports the income disparity for EHL (Lee et al., 2022). Efforts should be made to ensure that individuals from lower income groups are not left behind in the digital health revolution.

This study has important clinical, research, and policy implications. The clinical implications include the need for targeted clinical interventions to support vulnerable populations as our findings suggest persistence of EHL disparities. Clinically, there is a need for developing and implementing personalized digital literacy training programs for older adults, racial/ethnic minorities, lower-income individuals, and those with limited English proficiency. Enhanced support services, such as multilingual and culturally sensitive digital health resources, should be provided to ensure non-English speakers benefit from digital health technologies. Healthcare providers should also proactively engage patients in discussions about digital health tools, emphasizing their benefits and offering assistance with their use (Wang and Luan, 2022).

From a research perspective, conducting longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impact of improved EHL on diabetes management and overall health is crucial. Additionally, investigating specific barriers preventing different demographic groups from achieving higher EHL and identifying effective strategies to overcome these obstacles is necessary. Testing and evaluating interventions designed to improve EHL in diverse populations will provide valuable insights into their effectiveness in enhancing digital health tool usage and health outcomes.

The policy implications of the study include supporting digital inclusion initiatives that provide affordable internet access and digital devices to low-income households, ensuring they can access digital health tools. Allocating funding for community-based digital literacy programs aimed at improving EHL among disadvantaged populations is also essential. Promoting the creation of multilingual and culturally appropriate digital health resources will cater to non-English speakers. Finally, advocating for policies that facilitate the integration of digital health technologies into existing healthcare systems will make them more accessible and user-friendly for all patients.

This study has several strengths to note. Our data is nationally representative and leverages NHIS data to characterize EHL in an important population with DM. Further, we selected a study population that with high levels of interaction with the healthcare system due to the chronic nature of DM care. Thus, we avoided potential sampling bias that may have occurred by including a healthy subpopulation that requires no regular medical care. Our focus on diabetes doesn't diminish EHL's importance in other groups; it allows us to gain valuable insights into EHL's role in chronic disease management.

This study has multiple limitations. Since this study relies on self-reported survey data, recall bias may be present. The assessment of EHL in NHIS ends in 2018 and our data are unable to study the rapid changes in EHL that occurred because of the COVID-19 pandemic. We anticipate EHL trajectories likely continued and potentially may have accelerated following the pandemic. The study did not distinguish between different levels of DM severity and lacked qualitative insights. We could not link EHL to clinical outcomes due to limitations in the dataset.

Ultimately, the findings of the study highlight the presence of disparities in EHL across different socioeconomic and demographic groups and the need for targeted interventions to address these disparities. Improving EHL is crucial for empowering individuals to effectively navigate digital health resources, make informed decisions, and engage in instructed management of their metabolic health. Future research and interventions should focus on reducing barriers to EHL and promoting health equity in the digital era.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Aditya Nagori: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Neil Keshvani: Writing – review & editing. Lajjaben Patel: Writing – review & editing. Ritika Dhruve: Writing – review & editing. Andrew Sumarsono: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr. Thomas Wang, MD, Dr. Ambarish Pandey, MD, and Michael Mitakidis, MD for their inputs and support.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Anderson A., O'Connell S.S., Thomas C., Chimmanamada R. Telehealth Interventions to Improve Diabetes Management Among Black and Hispanic Patients: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. Dec 2022;9(6):2375–2386. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzopardi-Muscat N., Sørensen K. Towards an equitable digital public health era: promoting equity through a health literacy perspective. The European Journal of Public Health. 2019;29(Suppl 3):13–17. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckz166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/health-equity/diabetes-by-the-numbers.html.

- CDC. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).

- Chesser A.K., Keene Woods N., Smothers K., Rogers N. Health Literacy and Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Gerontol Geriatr Med. Jan-Dec. 2016;2 doi: 10.1177/2333721416630492. 2333721416630492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi N.G., Dinitto D.M. The digital divide among low-income homebound older adults: Internet use patterns, eHealth literacy, and attitudes toward computer/Internet use. J Med Internet Res. May 2. 2013;15(5):e93. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estacio E.V., Whittle R., Protheroe J. The digital divide: Examining socio-demographic factors associated with health literacy, access and use of internet to seek health information. J. Health Psychol. 2019;24(12):1668–1675. doi: 10.1177/1359105317695429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang M, Wang D, Coresh J, Selvin E. Trends in Diabetes Treatment and Control in U.S. Adults, 1999-2018. N Engl J Med. Jun 10 2021;384(23):2219-2228. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa2032271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fleming GA, Petrie JR, Bergenstal RM, Holl RW, Peters AL, Heinemann L. Diabetes digital app technology: benefits, challenges, and recommendations. A consensus report by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) Diabetes Technology Working Group. Diabetologia. Feb 2020;63(2):229-241. doi:10.1007/s00125-019-05034-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fortmann A.L., Gallo L.C., Garcia M.I., et al. Dulce Digital: An mHealth SMS-Based Intervention Improves Glycemic Control in Hispanics With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. Oct 2017;40(10):1349–1355. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S.H., Hsing H.C., Lin J.L., Lee C.C. Relationships Between Mobile eHealth Literacy, Diabetes Self-care, and Glycemic Outcomes in Taiwanese Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Cross-sectional Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. Feb 5. 2021;9(2):e18404. doi: 10.2196/18404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Briggs F., Ephraim P.L., Vrany E.A., et al. Social Determinants of Health, Race, and Diabetes Population Health Improvement: Black/African Americans as a Population Exemplar. Curr Diab Rep. Mar 2022;22(3):117–128. doi: 10.1007/s11892-022-01454-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Briggs F., Fitzpatrick S.L. Overview of Social Determinants of Health in the Development of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(9):1590–1598. doi: 10.2337/dci23-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Briggs F., Adler N.E., Berkowitz S.A., et al. Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes: A Scientific Review. Diabetes Care. 2020;44(1):258–279. doi: 10.2337/dci20-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Wen X., Wang F., et al. Effect of telemedicine intervention on hypoglycaemia in diabetes patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Telemed Telecare. Aug 2019;25(7):402–413. doi: 10.1177/1357633x18776823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Yeung A.M., DuBord A.Y., et al. Diabetes Technology Meeting 2022. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2023;17(4):1085–1120. doi: 10.1177/19322968221148743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Shin S., Kim S., Lee E. The Relation Between eHealth Literacy and Health-Related Behaviors: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023;25:e40778. doi: 10.2196/40778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Chang A., Pal A., Tran T.-A., Cui X., Quach T. Understanding and Addressing the Digital Health Literacy Needs of Low-Income Limited English Proficient Asian American Patients. Health Equity. 2022;6(1):494–499. doi: 10.1089/heq.2022.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy N.K., Park A., Solis D., et al. Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes-Related Distress in Patients With Insulin-Dependent Type 2 Diabetes: Cross-sectional. Mixed Methods Approach. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(10):e40164. doi: 10.2196/40164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magliano D.J., Martin V.J., Owen A.J., Zomer E., Liew D. The productivity burden of diabetes at a population level. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):979–984. doi: 10.2337/dc17-2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan S., Lu Y., Spatz E.S., Nasir K., Krumholz H.M. Trends and Predictors of Use of Digital Health Technology in the United States. Am. J. Med. 2021/01/01/ 2021,;134(1):129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata-Cases M., Rodríguez-Sánchez B., Mauricio D., et al. The Association Between Poor Glycemic Control and Health Care Costs in People With Diabetes: A Population-Based Study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(4):751–758. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman CD, Skinner HA. eHEALS: The eHealth Literacy Scale. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2006;8(4):e27-e27. doi:10.2196/jmir.8.4.e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Norman C.D., Skinner H.A. eHealth Literacy: Essential Skills for Consumer Health in a Networked World. J. Med. Internet Res. 2006;8(2):e9. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8.2.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S.Y., Kim C., Shin D.W., Steinhubl S.R. Present and Future of Digital Health in Diabetes and Metabolic Disease. Diabetes Metab J. Dec 2020;44(6):819–827. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2020.0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan R., Sarkar S., Martin S.S. Digital health technology and mobile devices for the management of diabetes mellitus: state of the art. Diabetologia. 2019;62(6):877–887. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4864-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens S., Gallagher S., Andrews T., Ashall-Payne L., Humphreys L., Leigh S. The effectiveness of digital health technologies for patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Front Clin Diabetes Healthc. 2022;3 doi: 10.3389/fcdhc.2022.936752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kessel R., Wong B.L.H., Clemens T., Brand H. Digital health literacy as a super determinant of health: More than simply the sum of its parts. Internet Interv. Mar 2022;27 doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2022.100500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman S., Echouffo-Tcheugui J.B., Selvin E., Fang M. Trends and Disparities in Glycemic Control and Severe Hyperglycemia Among US Adults With Diabetes Using Insulin, 1988–2020. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022;5(12):e2247656–e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.47656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Li X., Wang Z., et al. Trends in Prevalence of Diabetes and Control of Risk Factors in Diabetes Among US Adults, 1999–2018. JAMA. 2021;326(8):704–716. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.9883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Luan W. Research progress on digital health literacy of older adults: A scoping review. Front Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.906089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong A.K.C., Bayuo J., Wong F.K.Y. Investigating predictors of self-care behavior among homebound older adults: The role of self-efficacy, eHealth literacy, and perceived social support. J Nurs Scholarsh. May 2022;54(3):278–285. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B. Improving older adults' e-health literacy through computer training using NIH online resources. Libr Inf Sci Res. 2012;34(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.lisr.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.