Abstract

Genital herpes (GH) is a common sexually transmitted disease, which is primarily caused by herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), and continues to be a global health concern. Although our understanding of the alterations in immune cell populations and immunomodulation in GH patients is still limited, it is evident that systemic intrinsic immunity, innate immunity, and adaptive immunity play crucial roles during HSV-2 infection and GH reactivation. To investigate the mechanisms underlying HSV-2 infection and recurrence, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) was performed on immune cells isolated from the peripheral blood of both healthy individuals and patients with recurrent GH. Furthermore, the systemic immune response in patients with recurrent GH showed activation of classical monocytes, CD4+ T cells, natural killer cells (NK cells), and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), especially of genes associated with the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway and T cell activation. Circulating immune cells in GH patients show higher expression of genes associated with inflammation and antiviral responses both in the scRNA-Seq data set and in independent quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis and ELISA experiments. This study demonstrated that localized genital herpes, resulting from HSV reactivation, may influence the functionality of circulating immune cells, suggesting a potential avenue for future research into the role of systemic immunity during HSV infection and recurrence.

Keywords: Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), Genital herpes (GH), Herpes simplex virus (HSV), Immune response

Highlights

-

•

An investigation was conducted into the pivotal genes and mechanisms in the immune response triggered by genital herpes.

-

•

Single-cell analysis of peripheral immune cells from genital herpes patients and healthy individuals was conducted.

-

•

Toll-like receptor signaling pathway and T cell activation enriched at genital herpes relapse.

1. Introduction

Genital herpes (GH), a common sexually transmitted disease (STD), is a global health issue. In 2016, it was estimated that nearly 500 million people aged 15–49 years worldwide were infected with HSV-2, representing a seroprevalence of 13.2%. Additionally, 3.75 billion people aged 0–49 years were infected with HSV-1, with a seroprevalence of 66.6% (James et al., 2020). GH patients are predominantly infected with HSV-2 (Corey and Handsfield, 2000; Groves, 2016). Although severe complications from HSV-2 infections are rare, they increase the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection by three- to five-fold due to the mucosal disruption and recruitment of CD4+ T lymphocytes (Freeman et al., 2006). Vertical transmission from mother to infant may also result in neonatal death despite prompt therapy. Furthermore, repeated incidences of genital lesions are associated with psychological stresses (Arduino and Porter, 2008; Gupta et al., 2007). Antiviral medications such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are commonly prescribed for GH. However, these drugs are unable to prevent GH recurrence (Tuddenham et al., 2022). Unfortunately, a permanent and highly effective cure for HSV infection remains elusive, and there are currently no licensed prophylactic or therapeutic vaccines on the market (Sharma et al., 2023).

HSV-1 and HSV-2 are double-stranded DNA viruses belonging to the family Alphaherpesvirinae. The HSV-1 and HSV-2 genomes show high sequence identity. These viruses can invade skin or mucosal lesions and induce a latent state in the sensory ganglia. The latent virus can periodically reactivate in response to specific triggers, including local trauma (e.g., surgery or UV light), systemic stimuli (e.g., immunosuppression or fever), and social stress (Cliffe et al., 2015; Dong-Newsom et al., 2010; Schiffer and Corey, 2013). These reactivation episodes are more common in HSV-2 infections (Tuddenham et al., 2022), but the specific triggers have not been explicitly identified (Gupta et al., 2007). Some studies have found evidence for a close link between HSV activity and the human immune system (Khanna et al., 2003). Clinical evidence indicates that immunosuppressed patients often have a longer duration, more severe symptoms, and a higher frequency of HSV reactivation than immunocompetent individuals (Gupta et al., 2007). However, these studies have generally focused on local immune responses at the affected skin or mucosal lesions, and the effect of HSV infection on systemic immune responses is less well understood. Studies on the role of the circulating immune system have been limited by the lack of bona fide cell and animal models (Birzer et al., 2020; Lang and Nikolich-Žugich, 2005; Yan et al., 2020).

In contrast to conventional bulk RNA sequencing, which reveals an average gene expression level of an ensemble of different cell types, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) can analyze gene expression in each cell group. ScRNA-seq is a type of high-throughput sequencing technology at the single-cell level, which can uncover new cell subpopulations and reveal features of cellular gene expression, and is particularly suitable for studies of infectious and tumor diseases (Choi et al., 2019; Suomalainen and Greber, 2021; Triana et al., 2021). Here, scRNA-seq profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and granular cell layers from patients with recurrent GH and HSV-2 IgG negative healthy controls was used to identify changes in the circulating immune system and transcriptional regulatory genes of individual immune cell subsets associated with GH recurrence. We uncovered an immunological landscape and showed that the expression of inflammation- and antiviral-related genes was upregulated in GH patients, in particular the Toll-like receptor and IL-17 signaling pathways. These findings reveal the activation of circulating immune cell subsets during GH recurrence, thereby identifying potential genes and pathways associated with GH episodes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects, clinical sample collection, and preparation of single-cell suspensions

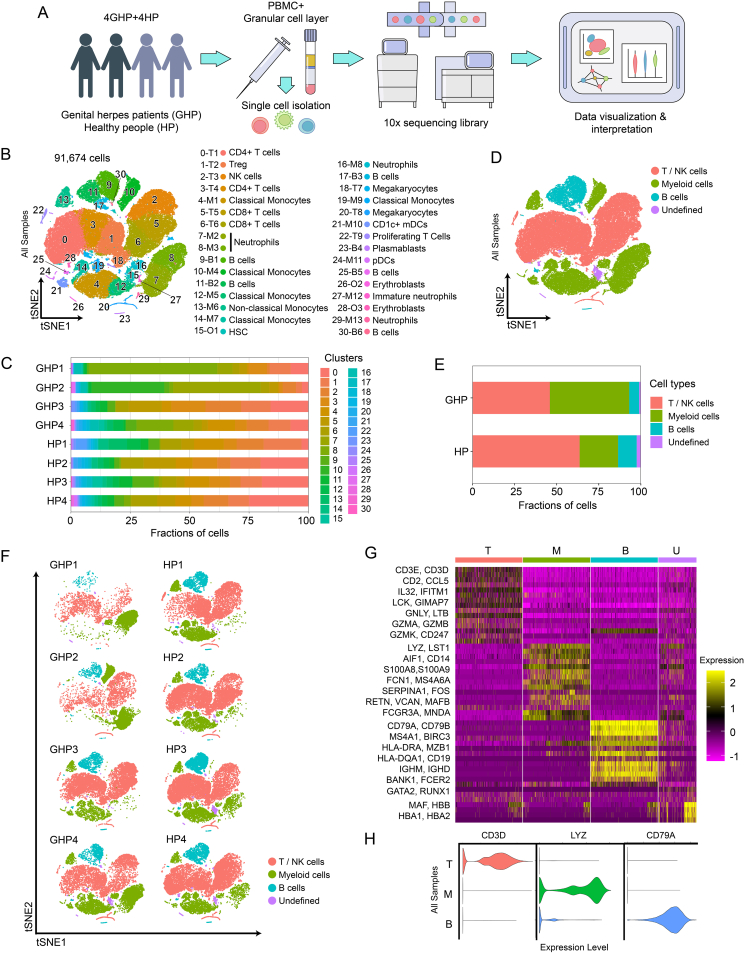

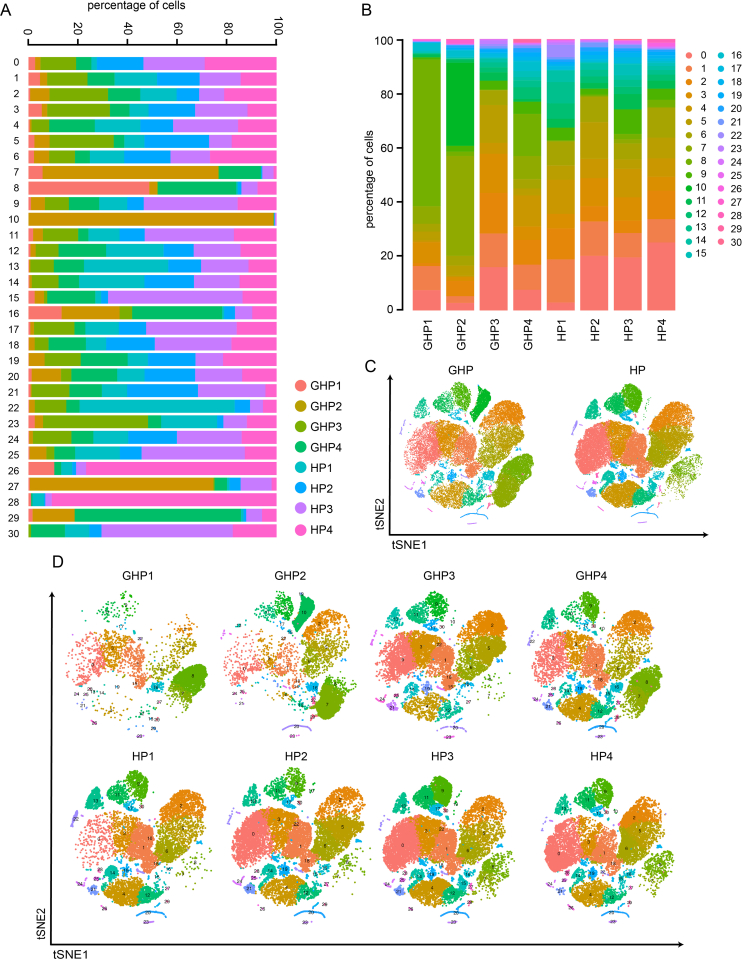

Whole-blood samples were collected from four patients suffering from recurrent GH [genital herpes patient (GHP) group], with at least six episodes per year, during their episodes of GH and four healthy volunteers who are HSV-2 IgG negative as controls [healthy person (HP) group]. They were admitted to the Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital (Hangzhou, China) between July 2020 and August 2020 (Supplementary Table S1). PBMCs and granular cell layers were isolated from blood anticoagulated with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation (Ficoll separation) (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Single-cell transcriptional profiling of PBMCs and granular cells. A The diagram of experimental workflow. B t-SNE projection of single-cell profile with each cell colored for 31 clusters based on the gene expression analysis. C The percent of cells for 31 clusters in 4 genital herpes patients (GHPs) and 4 healthy persons (HPs). D t-SNE projection of single-cell profile with each cell colored for sample type and different cell type based on the gene expression analysis. E The percent of cells for 4 cell types in each donor group. F t-SNE projections of the 8 sequenced samples showing the redistribution of the indicated cell populations. G Heatmap shows the upregulated and downregulated genes in T cell, B cell, myeloid cell, and undefined cell groups. Yellow: high expression; Purple: low/no expression. Each column represents a single cell and each row represents a gene. H Violin plots of specific genes of T cell (T), B cell (B), and Myeloid cell groups (M).

Blood cells and plasma were collected from patients with clinical relapse and from volunteers for subsequent experiments. Plasma was isolated from each participant and stored at −80 °C. Blood cells were lysed using red blood cell lysis solution (Biosharp, China). The immune cells were then collected for flow cytometry and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis.

2.2. Chromium 10× Genomics library and sequencing

Single-cell suspensions were counted and loaded onto the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Chip (10× Genomics) according to the manufacturer's instructions for the 10× Genomics Chromium Single-Cell 3′ kit v3. The 12 10× reactions were distributed across 5 chips, with each reaction involving the following numbers of cells: 4,794 (GHP1), 10,597 (GHP2), 11,996 (GHP3), 10,917 (GHP4), 9,873 (HP1), 12,404 (HP2), 16,777 (HP3), and 15,911 (HP4). The following cDNA amplification and library construction steps were performed according to the standard protocol. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencing system (paired-end multiplexing run, 150 bp) by LC-Bio Technology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). Cells representing doublets, low-quality cells, and empty droplets were deleted after they passed severe high-quality filtering (Supplementary Table S2).

2.3. scRNA-seq data alignment and sample aggregating

Sequence data were demultiplexed and converted to FASTQ format using Illumina bcl2fastq software. Sample demultiplexing, barcode processing and single-cell 3′ gene counting were conducted by Cell Ranger version 3.1.0 (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/pipelines/latest/what-is-cell-ranger, 10× Genomics). ScRNA-seq data were aligned to the human reference genome (hg19, GRCh37).

2.4. Dimensional reduction and clustering analysis

The Cell Ranger output was loaded into Seurat version 3.1.1 (Stuart et al., 2019) (https://satijalab.org/) for dimensional reduction, clustering and data analysis of scRNA-seq data. Overall, cells passing the quality control threshold needed to meet the following criteria: genes expressed in less than one cell were removed; the number of genes expressed per cell was set with a lower cutoff (> 500) and an upper cutoff (< 5000); UMI counts exceeded 500; and the percentage of mitochondrial DNA-derived gene expression was < 25%. The LogNormalize method of Seurat software was used to calculate the expression value of genes. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the normalized expression values. The top 10 principal components (PCs) were utilized for clustering and t-SNE analysis. Clusters were identified using a weighted Shared Nearest Neighbor (SNN) graph-based clustering method. Marker genes for each cluster and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the two groups were identified using the ‘bimod’ (likelihood-ratio test) method with default parameters via the FindAllMarkers function in Seurat. Marker genes for each cluster were selected based on expression in more than 10% of the cells in a cluster and an average log (fold change) greater than or equal to 0.26. Cell types were identified and annotated using the SingleR package (Aran et al., 2019), the Cellmarker database (http://biocc.hrbmu.edu.cn/CellMarker/), and the GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/), and subsequently clustered using the Seurat package (Butler et al., 2018).

2.5. GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

The Gene Ontology (GO, http://www.geneontology.org) (Ashburner et al., 2000) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, http://www.genome.jp/kegg) (Kanehisa et al., 2021) enrichment analyses were performed to annotate the functions of DEGs. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp) was performed using the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB).

2.6. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from blood samples through blood RNA kit (Yeasen, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted RNA was quantified via Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and converted to cDNA using the PrimeScrip™ FAST RT reagent Kit with gDNA EraserR (Takara, Japan), following the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

qRT-PCR was performed to evaluate mRNA expression using TB Green Premix Ex TaqTM II (Takara, Japan) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Each reaction was conducted in triplicate. Relative gene expression levels were normalized with human β-actin using the 2^ΔΔCT method. The IFNGR1 primers were: forward 5'-TCTTTGGGTCAGAGTTAAAGCCA-3' and reverse 5'-TTCCATCTCGGCATACAGCAA-3'. The IFNGR2 primers were: forward 5'-CTCCTCAGCACCCGAAGATTC-3' and reverse 5'-GCCGTGAACCATTTACTGTCG-3'. The S100A8 primers were: forward 5'-ATGCCGTCTACAGGGATGAC-3' and reverse 5'-ACTGAGGACACTCGGTCTCTA-3'. The S100A9 primers were: forward 5'-GGTCATAGAACACATCATGGAGG-3' and reverse 5'-GGCCTGGCTTATGGTGGTG-3'. The CXCL8 primers were: forward 5'-ACTGAGAGTGATTGAGAGTGGAC-3′ and reverse 5'-AACCCTCTGCACCCAGTTTTC-3'.

2.8. ELISA

Human IL-8 ELISA Kit (Elabscience, China), Human TLR-2 (Toll-like Receptor 2) ELISA Kit (Elabscience, China), and Human IFN-γ (Interferon Gamma) ELISA Kit (Elabscience, China) were used to measure protein levels in the plasma, according to the manufacturer's protocols.

2.9. Flow cytometry

Immune cells were stained with antibodies targeting CD45-APC-H7 (BD Pharmingen, USA), CD11b-APC (BioLegend, USA), CD66b-FITC (BioLegend, USA), CD14-PE (BioLegend, USA), and 7-AAD staining (BD Pharmingen, USA). Live cells were identified as 7-AAD negative. CD45+ cells were gated as lymphocytes and further subdivided as myeloid cells (CD45+CD11b+), neutrophils (CD45+CD66b+), and CD14+ monocytes (CD45+CD14+). Gates for activation and inhibitory markers were established using isotype control antibodies.

2.10. Quantification statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for scRNA-seq data was described above. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8, using unpaired two-tailed Student's t-tests or pair t-tests where appropriate. Other statistical methods are detailed in Supplementary Table S9.

3. Results

3.1. The myeloid cell population is a predominant immune cell population in some GH patients

To investigate the role of systemic immune responses in GH, we conducted scRNA-seq on PBMCs and granular cells obtained from four patients at the onset of GH and four age- and sex-matched healthy volunteers (Supplementary Table S1). After high-quality filtering, 91,674 PBMCs and granular cells were included in further analyses (GHP group, 37,690 cells; HP group, 53,984 cells) (Fig. 1B). Cells were categorized into 31 clusters based on marker genes and SingleR validation (Supplementary Table S3; Supplementary Fig. S1), which correspond to T cells (CD4+ and CD8+ subsets), B cells (naïve and plasmablasts subsets), natural killer cells, monocytes (CD14+ and CD16+ subsets), neutrophils (mature and immature subsets), and dendritic cells (myeloid DCs and plasmacytoid DCs) (Fig. 1B and C, Supplementary Tables S4–S6). These 31 clusters were then grouped into four categories according to cell types and functions: T and NK cell group, B cell group, myeloid cell group, and undefined cell group (Fig. 1D and E, Supplementary Fig. S2A). The T and NK cell group comprised T cells highly expressing CD3D, CD3E, and CD2, and NK cells expressing GZMB and GNLY (56.4% of total cells). The B cell group contained B cells expressing CD79A, CD79B, and CD20 (MS4A1) (8.9% of total cells) and the myeloid cell group was formed by myeloid cells expressing LYZ, S100A9, and S100A8 (32.8% of total cells), which included monocytes (CD14+ and CD16+ subsets), neutrophils, and DCs (myeloid DCs and plasmacytoid DCs) (Fig. 1D–H, Supplementary Fig. S2B and C). The undefined cell group (1.9% of total cells) included subtypes of cells with high GATA2 or HBB gene expression and is likely a mixture of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and erythroblasts (Fig. 1D–G). Myeloid cells including neutrophils (cluster 7 and 8) and classical monocytes (cluster 10) had a relatively high proportion of GH patients: 36.77% of GHP2 cells were cluster 7 cells, 54.06% of GHP1 cells and 15.53% of GHP4 cells were cluster 8 cells, both neutrophils, and 30.59% of GHP2 cells were classical monocytes (cluster 10). In healthy volunteers, only 1%–2% of cells were found in cluster 7, 8, and 10 (Supplementary Table S3). The elevated myeloid cell populations in patients’ blood support the hypothesis that, in addition to immune cells at skin lesion sites (Adachi et al., 2021; Dhanushkodi et al., 2022), recurrence of GH might influence circulating immune cells.

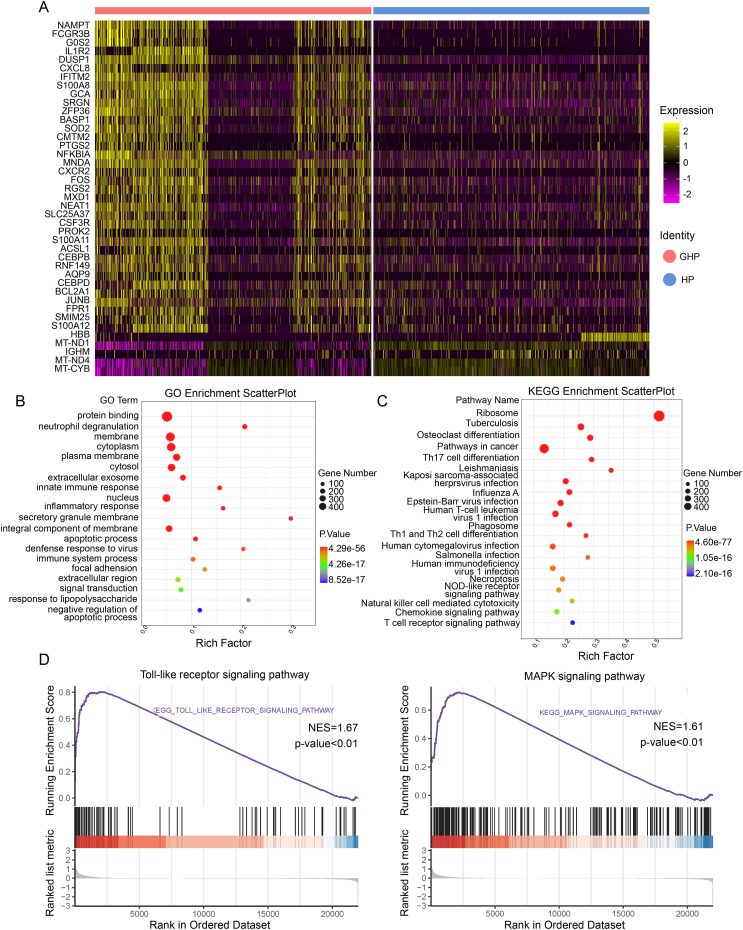

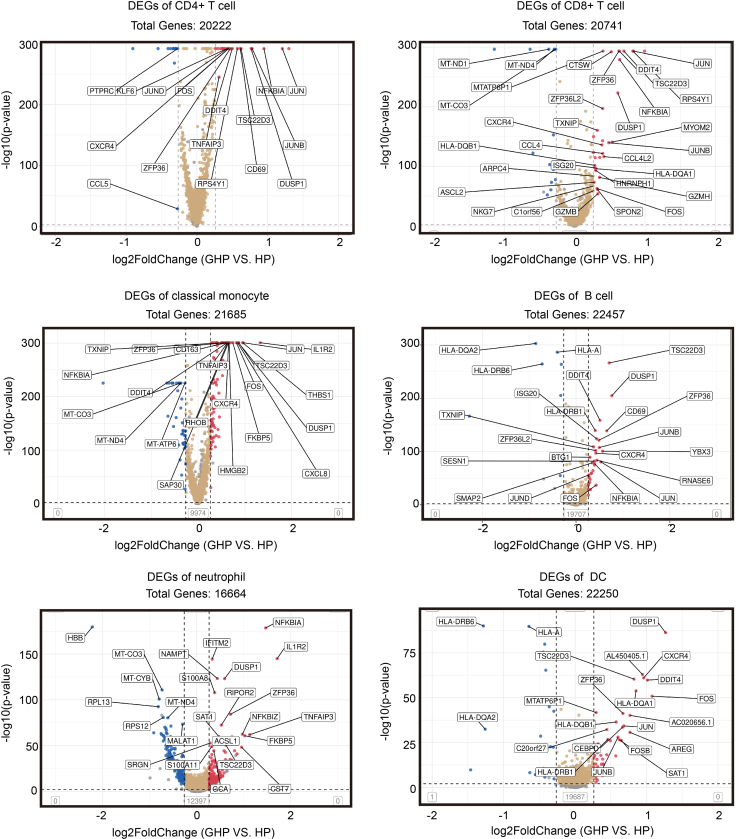

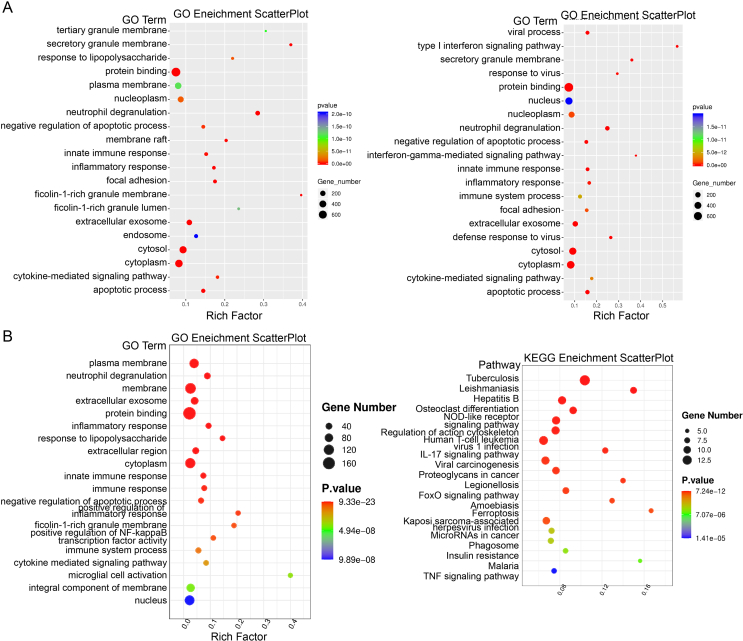

3.2. Activation of inflammatory-related pathways in recurrent GH patients

To explore the immune pathways associated with recurrent GH, we carried out a DEGs analysis between the GHP and HP groups. A total of 651 up-regulated genes and 242 down-regulated genes (log2Fold-change ≥ 0.26, P < 0.01) were identified in the GH group compared with the HP group. The top 10 up-regulated genes include NAMPT, FCGR3B, G0S2, IL1R2, DUSP1, CXCL8, IFITM2, S100A8, GCA, and SRGN (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table S7, Fig. S4). Most of these genes participate in cellular metabolic processes, inflammatory responses, and apoptosis. Identified GO-annotated modules participate in biological process associated with viral infection and immune responses, including neutrophil degranulation (GO: 0043312), innate immune response (GO: 0045087), inflammatory response (GO: 0006954), defense response to virus (GO: 0051607), and immune system process (GO: 0002376). KEGG enrichment pathway analyses also identified Th17 cell differentiation (hsa04659), Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation (hsa04658), NOD-like receptor signaling pathway (hsa04621) and Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity (hsa04650) (Fig. 2B and 2C). Our GSEA analysis showed enrichment in the MAPK signaling pathway (GSEA normalized enrichment score = 1.61, P-adjust < 0.01, q-values < 0.01), Toll-like receptor signaling pathway (GSEA normalized enrichment score = 1.67, P-adjust < 0.01, q-values < 0.01), and JAK-STAT signaling pathway (GSEA normalized enrichment score = 1.53, P-adjust < 0.05, q-values < 0.05) (Fig. 2D). The genes including FOS, JUN, RAC1, MAPK1, MAPK14, IL1B, MAP2K3, are simultaneously involved in both the MAPK signaling pathway and Toll-like receptor signaling pathway.

Fig. 2.

The DEGs analysis between GHP and HP. A Heatmap shows the upregulated and downregulated genes in GHP and HP of single cells. B GO term enrichment analysis for the DEGs between GHP and HP. C KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the DEGs between GHP and HP. D GSEA enrichment analysis reveals significant enrichment of DEGs in both the Toll-like signaling pathway (NES = 1.67, P-adjust < 0.01, q-values < 0.01) and the MAPK signaling pathway (NES = 1.61, P-adjust < 0.01, q-values < 0.01) between two groups.

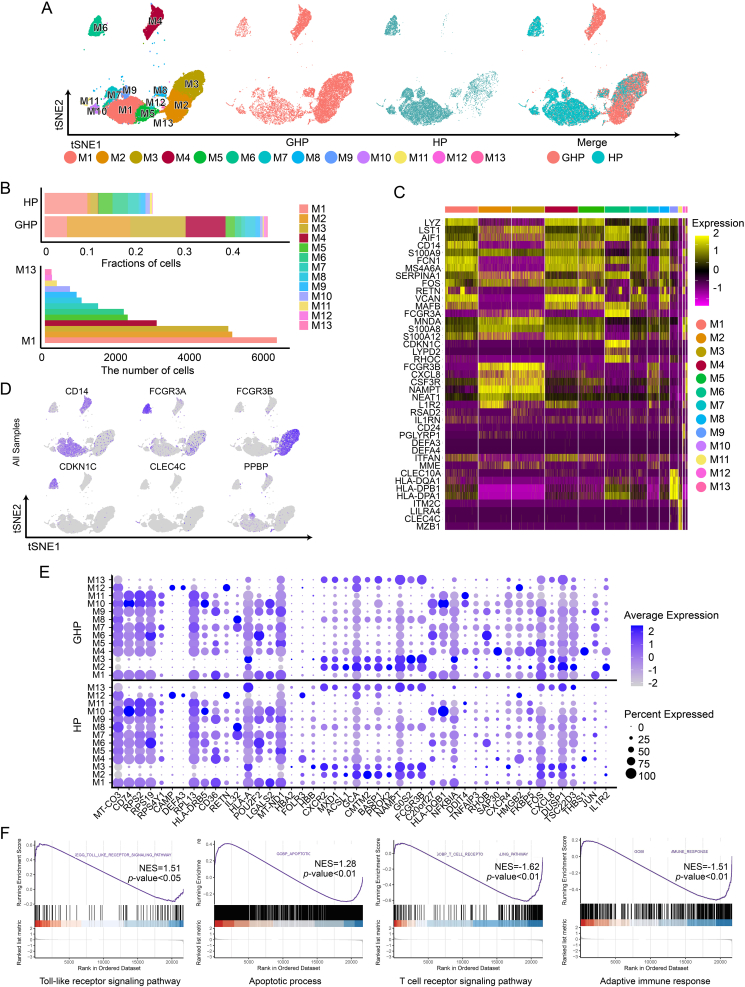

3.3. Myeloid cell clusters highly expressed inflammation-related genes in recurrent GH patients

The myeloid cell group comprised 13 clusters (M1–M13), encompassing classical and non-classical monocytes, neutrophils, myeloid dendritic cells (DCs), and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) (Fig. 3A and 3B). Five clusters (M1, M4, M5, M7, and M9) consisted of classical monocytes (CD14+CD16−). These clusters exhibited high expression of inflammation-related genes such as S100A8, S100A9, S100A12, and RETN (Zeiner et al., 2015) (Fig. 3C and 3D). Cluster M9 showed high expression of PPBP (CXCL7) and PF4 (CXCL4), linked to chemokine release and receptor desensitization (Schwartzkopff et al., 2012). Upregulation of CXCL8, ZFP36, CXCR4, CCL3, PPBP, and CCL3L1, associated with monocyte migration, was observed in cluster M9 (Geissmann et al., 2003). Comparing the changes in M9 gene expression between the GHP and HP groups, we found that the M9 gene cluster in the GHP group exhibited higher levels of monocyte migration-related genes such as CXCL8, ZFP36, CXCR4, CCL3, and CCL3L1 (Supplementary Table S7). This indicates a more pronounced tendency for the classical monocyte population in the GHP group to migrate from blood into tissues, suggesting a potential role of the M9 classical monocyte population in GH relapse by inducing chemotaxis of effector cells to infection sites. The DEGs analysis revealed increased expression of genes such as JUN, DUSP1, FOS, HLA-DQB1, RHOB, TSC22D3, ZFP36, JER2, JUNB, PPBP, G0S2, and NFKBIA in classical monocytes of the GHP group (Fig. 3E; Supplementary Table S7). DEGs in classical monocytes between GHP and HP showed significant enrichment in immune response (GO: 0006955), inflammatory response (GO: 0006954), mitochondrion (GO: 0005739), and oxidative phosphorylation (hsa00190) according to GO and KEGG enrichment analysis (Supplementary Fig. S5). GSEA analysis of these DEGs revealed enrichment in the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway (GSEA normalized enrichment score = 1.51, P-adjust < 0.05, q-values <0.05), apoptotic process (GSEA normalized enrichment score = 1.28, P-adjust < 0.01, q-values < 0.01), T cell receptor signaling pathway (GSEA normalized enrichment score = −1.62, P-adjust < 0.01, q-values < 0.01), and adaptive immune response (GSEA normalized enrichment score = −1.51, P-adjust < 0.01, q-values < 0.01) (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Distinct cell types in the myeloid cell group. A t-SNE projections of single-cell profile with each cell colored for myeloid cell group (left to right): the cell type, the corresponding status (GHP and HP), and merged two status. B The proportion of myeloid cell clusters (M1–M13) in HP and GHP and the number of cells for each cluster (from bottom to top are M1 to M13). C Heatmap shows the upregulated and downregulated genes in myeloid cell group. D t-SNE projections of marker gene expression for the myeloid cell group. E Dot plots indicate the intersection of the DEGs sorted by average log fold change determined for the indicated myeloid cell group of GHP and HP. F GSEA enrichment analysis of the DEGs in classical monocytes.

Cluster M6 was identified as a non-classical monocyte cluster (CD14lowCD16+), which expressed CD16A (FCGR3A), CDKN1C, RHOC, and LYPD2, but without S100A12 expression. These cells are assumed to exercise the function of surveillance in the immune process (Bianchini et al., 2019). In our study, non-classical monocytes exhibited high expression of CDKN1C and RHOC, while the expressions of inflammatory response-associated genes such as S100A8 and S100A12 were low.

Neutrophils are capable of infiltrating GH skin lesions (Shao et al., 2021). Mature and immature neutrophils were classified into clusters M2, M3, M8, M12, and M13. Mature neutrophils (M2, M3, M8, and M13) express high levels of FCGR3B (CD16B). Immature neutrophils (M12) highly express CD24, PGLYRP1, DEFA3, and DEFA4 (Fig. 3C–E). Furthermore, according to our GO enrichment analysis, clusters M2 and M3 were both enriched for similar terms, such as apoptotic process and inflammatory response. However, M3 expressed more genes related to viral response status (Supplementary Fig. S6A). According to the GO and KEGG analysis of DEGs between GHP and HP, neutrophils in the GHP group appeared to be in a more activated state compared to the HP group, which corresponds to these cell populations being predominantly represented in GHP patients, as the upregulated genes were mainly enriched in IL-17 signaling pathway, NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, and immune system process (Supplementary Fig. S6B).

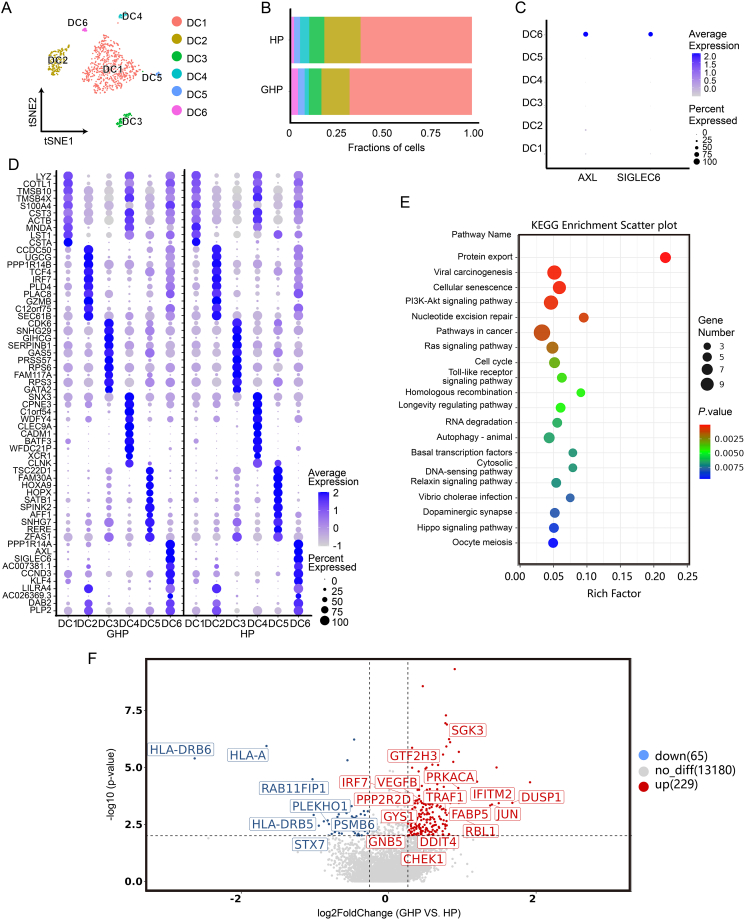

3.4. DC clusters and their potential impact on recurrent GH

Dendritic cells play an important role in HSV infection. We identified two DC clusters: myeloid DCs (mDCs), which expressed the DC-specific marker CLEC10A (M10), and M11, a plasmacytoid DC (pDC) cluster characterized by high expression of ITM2C, LILRA4, and CLEC4C (Cao and Bover, 2010; Murray et al., 2019) (Fig. 3C–E). In GH patients, the proportion of pDCs decreased (0.24% vs. 0.74%, P < 0.01). GO enrichment analysis of DCs showed that upregulated genes in the GHP group are involved in protein binding (GO: 0005515), apoptotic process (GO: 0006915), as well as the MHC class II protein complex (GO: 0042613). Genes associated with the MHC class II protein complex, including upregulated HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DRB5, HLA-DRB6, HLA-DPA1, and downregulated HLA-DQA2, were identified. Additionally, genes associated with the interferon-gamma-mediated signaling pathway and immune response, such as FOS, JUN, CXCR4, and DUSP1 were highly expressed in the pDC cluster of the GHP group (Fig. 3E).

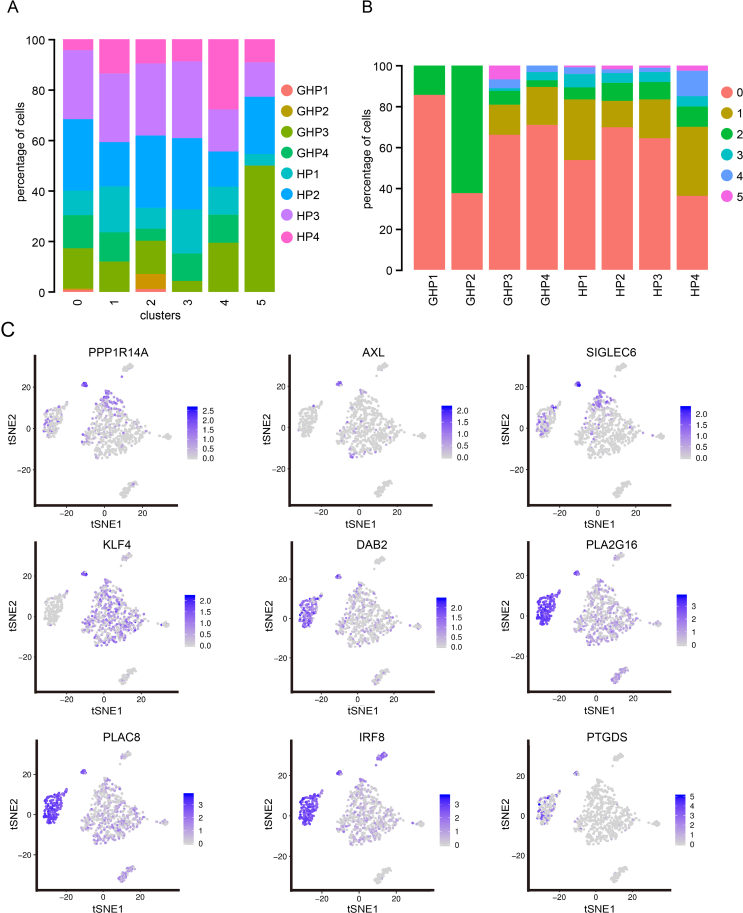

Due to the low levels of DCs in peripheral blood and the controversial nature of each DC subpopulation, we subsequently conducted a more detailed subpopulation analysis of DCs and pDCs. The total of 1058 identified DCs were re-clustered into 6 clusters (DC1–DC6) (Fig. 4A and B, Supplementary Fig. S7A and S7B). Cluster DC6 exhibited high expression of AXL and SIGLEC6 (Fig. 4C), indicating that this cluster represented the AXL+SIGLEC6+ DC (AS DC) subpopulation, a DC subset that constitutes 2% to 3% of the DC population and expresses both conventional DC (cDC) and pDC-associated markers (Alcántara-Hernández et al., 2017; Villani et al., 2017). PPP1R14A, CCND3, KLF4, LILRA4, DAB2, and PLP2 exhibited strong expression in these cells (Supplementary Table S8 and Fig. S7C). The DEGs of GHP AS DCs were enriched in the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (map04151) (Fig. 4D and 4E), including the up-regulated genes SGK3, VEGFB, DDIT4, PPP2R2D, GNB5, and GYS1 (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

The re-clustering analysis of DCs. A t-SNE projection of single-cell profile with each cell colored for 6 DC clusters based on the gene expression analysis. B The proportion of DC clusters (DC1–DC6) in HP and GHP. C Dot plots of AXL and SIGLEC6 expression in DCs. D Dot plots indicate the intersection of the DEGs sorted by average log fold change determined for the indicated DC clusters of GHP and HP. E KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the DEGs of DC6 cluster. F Volcano plot displays the upregulated genes (red) and downregulated genes (blue) for the DC6 cluster.

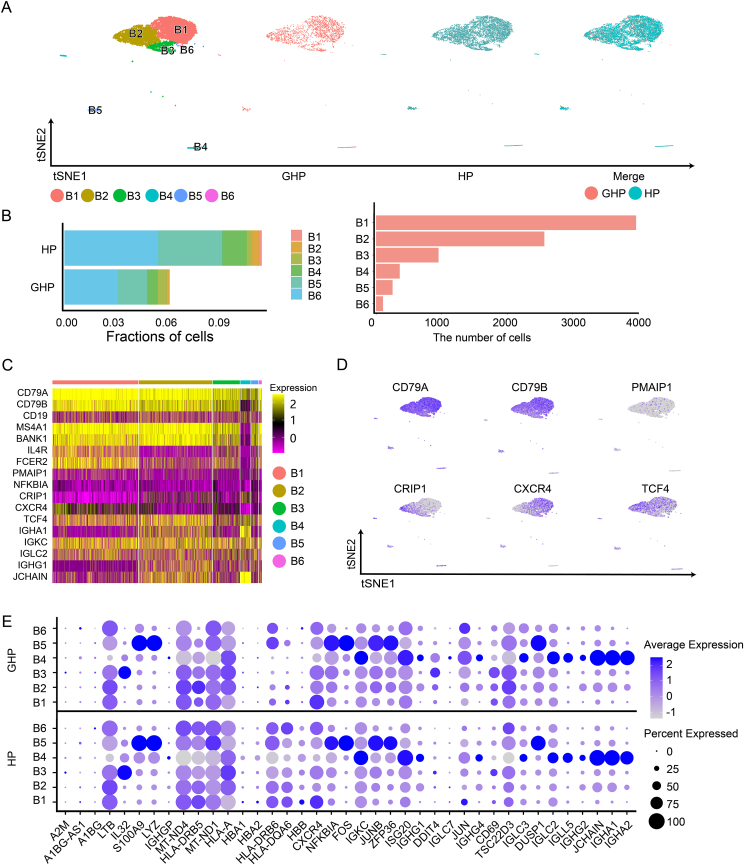

3.5. scRNA-seq identified 6 B cell clusters

Six B cell clusters (B1–B6) expressing CD79A, CD79B, and CD20 (MS4A1) were identified, representing various stages of B cell development in peripheral blood (Fig. 5A and 5B). CD79A and MS4A1, markers of mature B cells, were strongly expressed in clusters B1, B2, B3, B5, and B6. The activated B cell marker TCF4 was also highly expressed in clusters B1, B2, and B3. Immunoglobulin-related genes such as IGHA1, IGKC, and IGLC2, which are characteristic of plasmablasts, were found in B4 (Fig. 5C and 5D). However, genes related to B cell activation such as IGHA1, MZB1, and S100A8 showed no significant difference between the GHP and HP groups (Fig. 5E and Supplementary Table S7).

Fig. 5.

Distinct cell types in the B cell group. A t-SNE projections of single-cell profile with each cell colored for B cell group (left to right): the cell type, the corresponding status (GHP and HP), and merged two status. B The proportion of B cell clusters (B1–B6) in HP and GHP and the number of cells for each cluster. C Heatmap shows the upregulated and downregulated genes in B cell group. D t-SNE projections of marker gene expression for the B cell group. E Dot plots indicate the intersection of the DEGs sorted by average log fold change determined for the indicated B cell clusters of both GHP and HP.

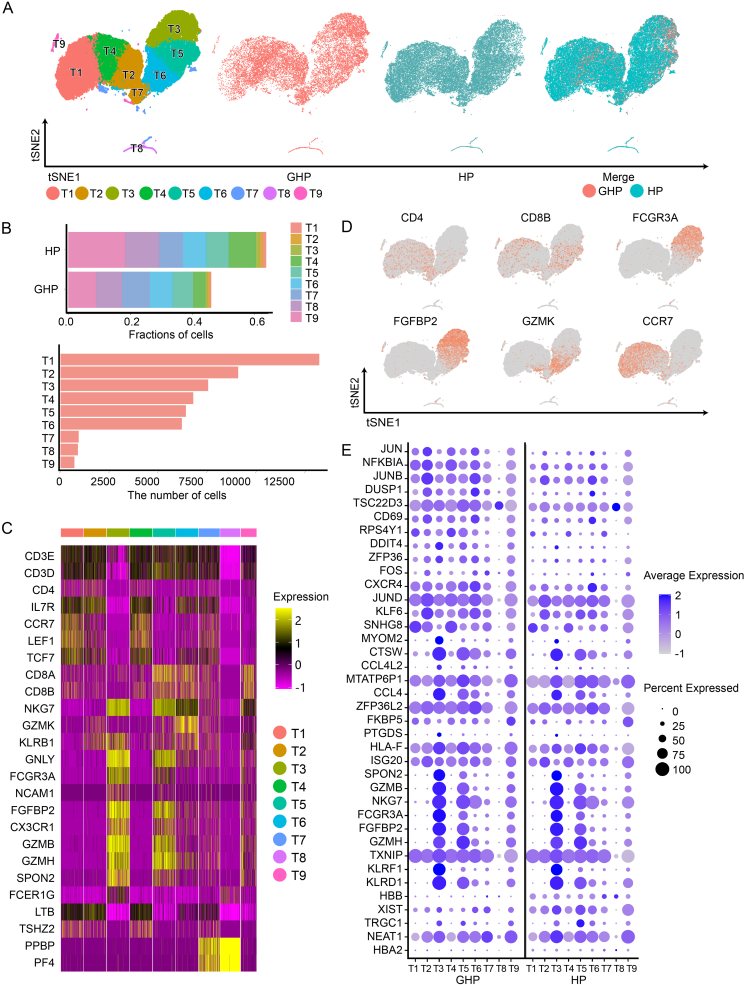

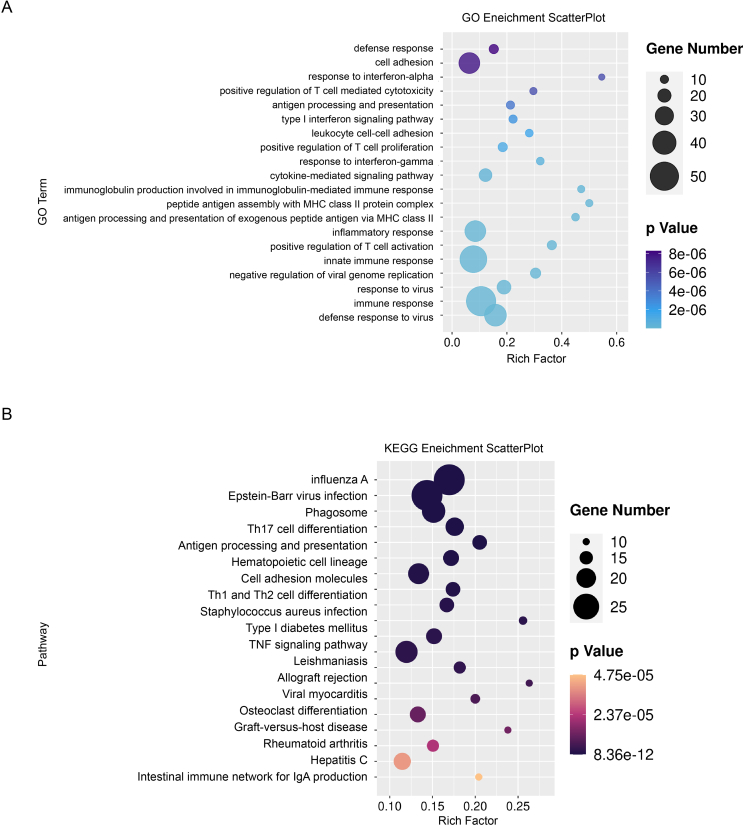

3.6. Up-regulated toll-like receptor signaling pathway genes in T and NK cells of GH patients

T and NK cells were separated into 9 clusters, including 7 CD3high clusters (Fig. 6A and 6B). In the GHP group, the proportions of clusters T1 and T2 were lower than in the HP group (Fig. 6B and Supplementary Table S3). Clusters T1, T2, and T4 were identified as CD4+ T cells. T1 exhibited a high level of CCR7, indicating that it was a naïve T cell cluster; T2 highly expressed FOXP3 and IL2RA, categorizing it as a Treg subset. LTB, a gene associated with activated CD4+ T cells, was highly expressed in T4. T2 also expressed AQP3, LDHB, and GPR183, all linked to T cell migration (Fig. 6C and 6D). Additionally, we identified two CD8+ T cell clusters with high CD8A and CD8B expression. The cytotoxic effector T cells (T5) highly expressed GZMH, NKG7, and FGFBP2, while the transitional CD8+ effector T cells (T6) expressed GZMK and KLRB1. Moreover, T7 and T8 were considered megakaryocyte-like cells as they expressed significant levels of PPBP, PF4, and GNG11. STMN1 and HIST1H4C, associated with proliferating T cells, were concentrated in the remaining T9 cluster (Fig. 6C and 6D). Two CD3low clusters were also identified. Apart from megakaryocyte-like cells (T8), T3 was defined as NK cells. GNLY, NKG7, GZMB, PRF1, KLRF1, and SPON2 were all expressed in this cluster, which are associated with NK cytotoxic activity and memory function.

Fig. 6.

Distinct cell types in the T/NK cell group. A t-SNE projections of single-cell profile with each cell colored for T/NK cell group (left to right): the cell type, the corresponding status (GHP and HP), and merged two status. B The proportion of T/NK cell clusters (T1–T9) in HP and GHP, and the number of cells for each cluster. C Heatmap shows the upregulated and downregulated genes in T/NK cell group. D t-SNE projections of marker gene expression for the T/NK cell group. E Dot plots indicate the intersection of the DEGs sorted by average log fold change determined for the indicated T/NK cell clusters of both GHP and HP.

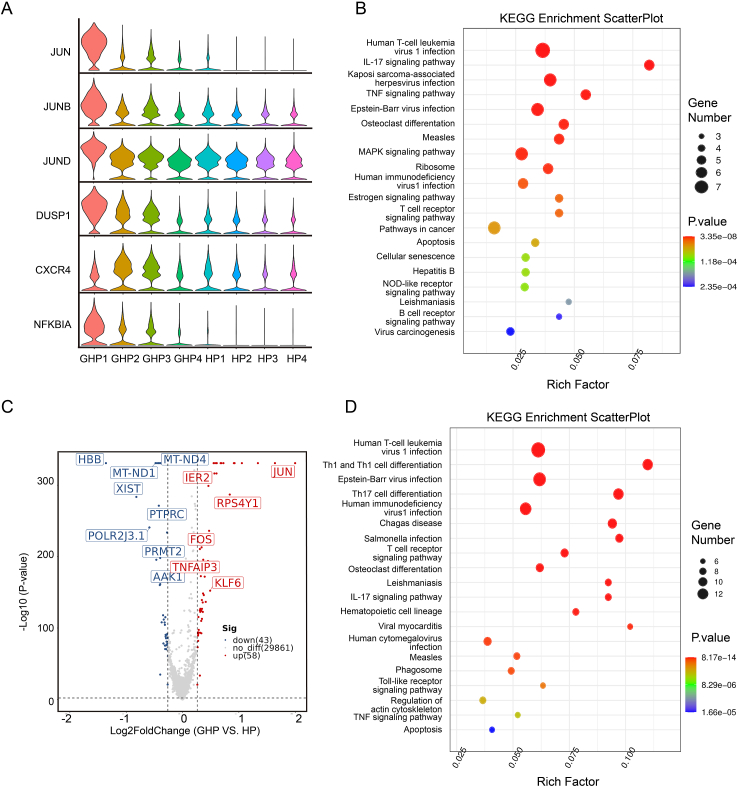

Notably, CD4+ T cells expressed inflammation-related genes, such as FOS, JUN, JUNB, JUND, DUSP1, CXCR4, and NFKBIA. They were significantly up-regulated in the GHP group (Fig. 6, Fig. 7A). These genes were primarily enriched in the TNF signaling pathway (map04668), IL-17 signaling pathway (map04657), Nod-like receptor signaling pathway (map04621), and MAPK signaling pathway (map04010) (Fig. 7B and 7C). Atypical and long-term HSV infections are the most common clinical manifestations of NK cell dysfunction, which is associated with Toll-like receptor and NOD-like receptor signaling pathways (Lenart et al., 2021). We found that the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway was enriched according to GO and KEGG enrichment analysis, with up-regulated NFKBIA, CCL4L2, FOS, JUN, and CCL4 in the GHP group (Fig. 7D and Supplementary Table S7). This result supports that the immune functions associated with GHP recurrence may be related to NK cells.

Fig. 7.

DEGs analysis of CD4+ T cells and NK cells. A Violin plots of specific differential genes in CD4+ T cells. B KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the DEGs in CD4+ T cells. C Volcano plot displays the upregulated genes (red) and downregulated genes (blue) for CD4+ T cells. D KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the DEGs in NK cells.

CD8+ T cells were decreased in the GHP group (T6 4.06% vs. 8.63%, P < 0.01), possibly due to CD8+ T cell exhaustion in GH patients. However, our DEGs analysis did not yield substantial evidence (Supplementary Table S7).

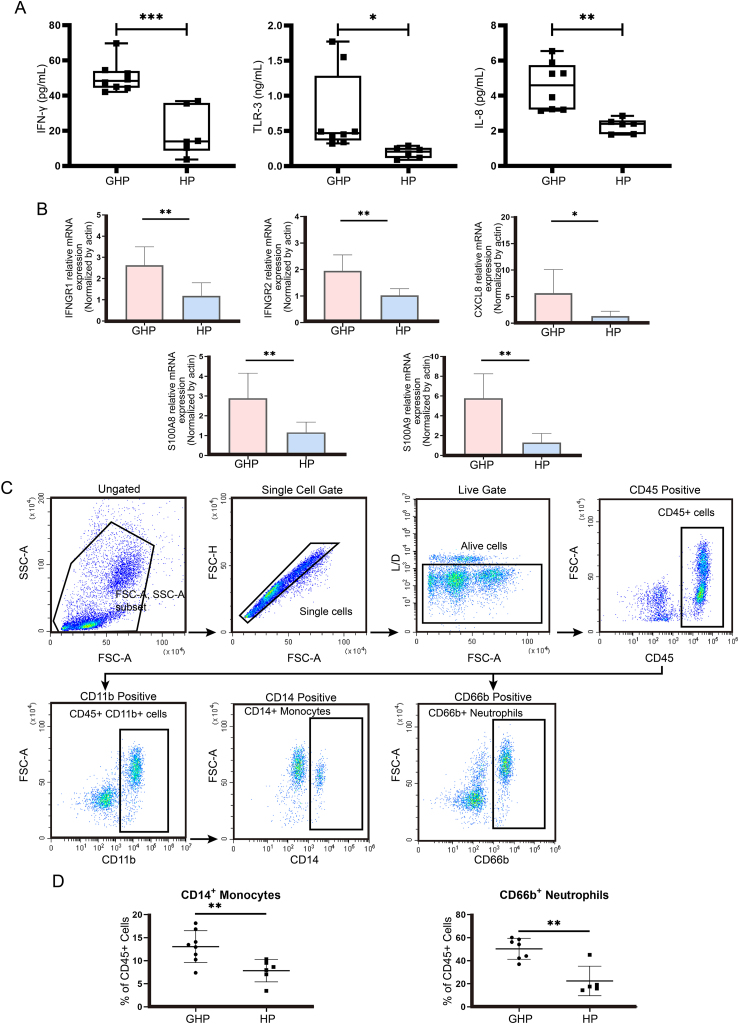

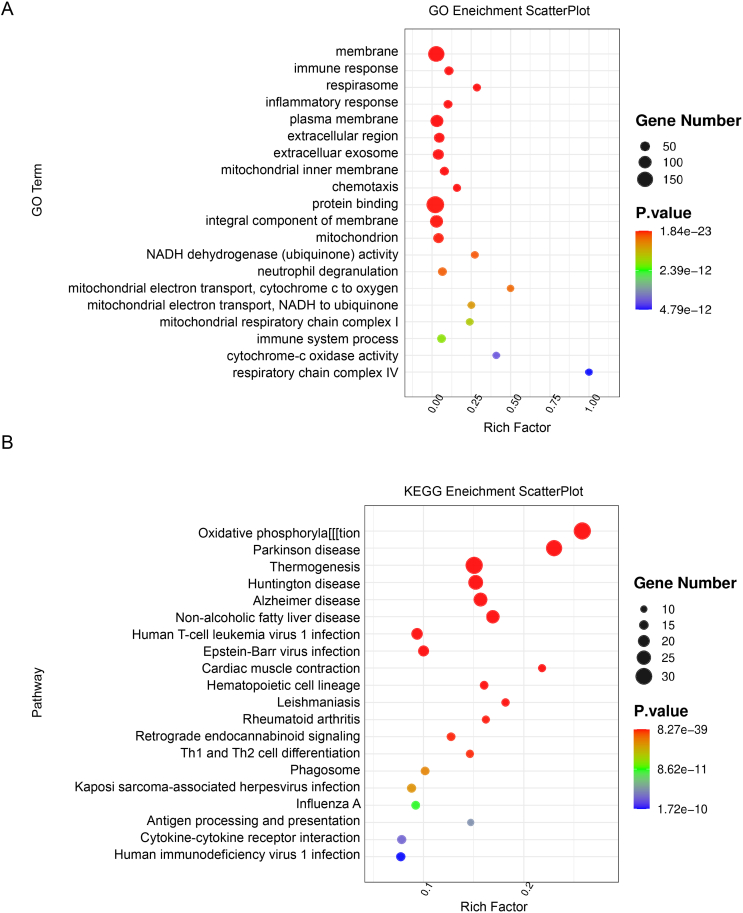

3.7. Experimental validation of elevated gene expression associated with immune inflammation and antiviral responses in genital herpes patients

We then sought to validate the scRNA-seq findings through flow cytometry analysis, ELISA, and qRT-PCR, involving 8 patients with genital herpes who experience more than 10 recurrences per year and had an outbreak within the last 3 days, as well as 6 healthy volunteers. None of these subjects were included in the scRNA-seq analysis.

The IFN-γ level in GHP plasma (50.59 ± 8.79 pg/μL) was significantly higher compared to HP plasma (19.03 ± 13.78 pg/μL; P < 0.001) (Fig. 8A). Similarly, the TLR-2 level in GHP plasma (0.73 ± 0.58 ng/μL) was elevated compared to HP plasma (0.19 ± 0.08 ng/μL; P < 0.05) (Fig. 8A). The IL-8 concentration in GHP plasma (4.55 ± 1.35 pg/μL) was markedly greater than in HP plasma (2.29 ± 0.42 pg/μL; P < 0.01) (Fig. 8A). The level of IFNGR1, IFNGR2, CXCL8, S100A8, and S100A9 mRNA expression in blood immune cells was determined by qRT-PCR. These mRNA expressions were significantly higher in GHP than in HP (P < 0.01, P < 0.05) (Fig. 8B). Likewise, CD14+ monocytes (13.07 ± 3.47% vs 7.84 ± 2.42%; P < 0.01) and neutrophils (50.35 ± 9.09% vs 22.44 ± 12.81%; P < 0.01) were more abundant in GHP than HP (Fig. 8C and 8D). These experimental results validated the results of scRNA-seq data.

Fig. 8.

ELISA, qRT-PCR and flow cytometry experiments confirm the scRNA-seq data. A The expression of IFN-γ, TLR-2 and IL-8 were detected using ELISA. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. B IFNGR1, IFNGR2, CXCL8, S100A8 and S100A9 expression was examined using qRT-PCR in GHP and HP blood immune cells and the data was analyzed using a Student's t-test. The experiments were performed with three replicates. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. C Gating strategy for detection of monocytes and neutrophils. Example of flow cytometry gating strategy plots from HP group. D Distribution analysis of CD14+ monocytes and CD66b+ neutrophols based on flow cytometry data. ∗∗P < 0.01.

4. Discussion

Recurrent GH represents a significant global health concern, given the inadequacy of current prevention and treatment strategies. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate the potential mechanisms underlying the host's response to recurrent GH. While research has primarily focused on local immune responses associated with GH, debates have arisen regarding the systemic regulation of immunity (Smith et al., 2022). For instance, previous studies examining CD4+ T cell-mediated immune responses following in vitro stimulation with HSV antigens found no significant differences between GH patients and HSV seropositive healthy controls (Franzen-Röhl et al., 2011). However, a cross-sectional study in HIV-infected individuals revealed a negative correlation between the frequency of circulating HSV-2-specific CD8+ T cells and the severity of GH (Sheth et al., 2008). Several studies have suggested an association between CD8+ T cell exhaustion and recurrent GH episodes (Moss et al., 2012; Posavad et al., 1997). Additionally, CD8+ T cells from patients with recurrent GH are more likely to express genes linked to depletion (Coulon et al., 2020; Lind et al., 2021).

In the local immune response, the immune system is already primed for an antiviral immune response associated with T cell activation in HSV-2 skin lesions. We analyzed publicly available RNA-sequence data of genital herpes from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). The differentially expressed genes between lesions and control skin profiles were derived from 26 lesion samples from patients with recurrent HSV-2 infection and 29 healthy genital skin samples (GSE#172423) and revealed significant enrichment for innate immune response, positive regulation of T cell activation (Th17 cell differentiation and Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation; P < 0.01 for both), inflammatory response and viral defense response (TNF signaling pathway and NOD-like receptor signaling pathway; P < 0.01 for both) (Supplementary Fig. S8). However, these data are solely based on local immune responses. This study aimed to elucidate the influence of HSV infection on circulating immune cell subsets during episodes of GH recurrent utilizing scRNA-seq on peripheral blood samples from GH patients and healthy controls to explore differences in distribution frequencies and immune cell subsets between the two groups. Remarkably, our analysis revealed that neutrophils (cluster 7 and 8) and classical monocytes cluster (cluster 10) were the predominant components of immune cells in GHP. The marker genes in these cells were enriched in GO terms such as viral process, innate immune response, and inflammatory response. These observed alterations are consistent with prior studies that have investigated changes in the cellular composition of peripheral blood during the pathophysiological response to infection (Garand et al., 2018).

Our investigation showed an upregulation of genes related to inflammation and antiviral responses within the immune cells of GH patients. In general, the DEGs exhibited enrichment in several pathways, including the NF-kappa B signaling pathway, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, Th17 cell differentiation, and IL-17 signaling pathway. Notably, these pathways encompassed genes such as NFKBIA, CXCL8, S100A8, and FOS, which collectively manifest the host response to HSV infection. The links between these pathways and HSV infection or relapse have been supported by various studies. For example, research has indicated that the diminished TLR3 response of NK cells is associated with susceptibility to herpes labialis, offering insight into why symptomatic outbreaks of herpes labialis tend to occur when the host's co-stimulatory functions are disrupted, such as during periods of stress or prolonged UV light exposure (Yang et al., 2012). Furthermore, another study highlighted the potential of vaccines targeting TLR-2 to elicit both local and systemic CD8+ T cell responses, thereby conferring protection against HSV-2 (Truong et al., 2019). Our findings are consistent with other research exploring the interplay between Toll-like receptor signaling pathway-related genes and HSV's interaction with the human immune system (Carty et al., 2014; Gao et al., 2021; Samudio et al., 2016). Importantly, the immune response to infection hinges on achieving a delicate equilibrium between protection against the pathogens and mitigation of potential immunopathological consequences.

The function and heterogeneity of myeloid cells in recurrent GH remain unclear and potentially associated with antigens. We proceeded to focus on the changes in gene expression within each cell type. Monocytes, which patrol various body tissues in search of infection signs, have the capacity to differentiate into dendritic cells and macrophages at infection sites. Monocyte-derived antigen-presenting cells (APCs) can stimulate effector Th1 cells to secrete IFN-γ, an essential mediator of cytotoxic T cells, for antiviral protection when viruses such as HSV-2 invade the body (Iijima et al., 2011). Research shows that IFN-γ has the potential to exert broad-spectrum antiviral effects within neurons and may also have additional effects on HSV-1 reactivation (Danastas et al., 2023). Our data suggest that GH may also influence the proliferation and development of circulating classical monocytes. These differences may be related to genes associated with immune cell activity, such as JUN, DUSP1, FOS, JUNB, and NFKBIA. While previous studies have reported sustained expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) within vaginal neutrophils after HSV-2 infection in a mouse model (Lebratti et al., 2021), our scRNA-seq data did not reveal a significant increase in ISG-related genes within the neutrophil population in GH patients.

Mature DCs function as primary APCs and secrete different cytokines depending on the stimulus. They can differentiate naïve T cells through the Th1 or Th2 pathway to exert immune effects. After recognizing the virus, DCs release IFN-I to inhibit HSV replication. pDCs efficiently release IFN-I (Macleod et al., 2014), thereby regulating the body's immunity and bridging innate and adaptive immunity to effectively suppress viral infections (Collins et al., 2017; Shin et al., 2016). Vaginal and low-grade systemic infections may require pDCs to control HSV infection (Kumamoto et al., 2013). However, the study did not find a significant association between GH severity and circulating pDC function (Sozzani et al., 2010; Swiecki et al., 2013). We found that changes in major histocompatibility complex genes, like HLA-A, HLA-DQA2, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DRB5, and HLA-DQA1, suggest potential alterations in pDC antigen presentation function during HSV episodes. We identified a cell population labeled AS DCs, characterized by high expression of AXL and SIGLEC6 (Chen et al., 2020; Leylek et al., 2019). KEGG pathway analysis revealed that DEGs in AS DCs were mainly enriched in the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway.

HSV-specific CD4+ T cells have been identified as infiltrating genital ulcerations caused by HSV-2 and secreting IFN-γ (Iijima and Iwasaki, 2016; Khanna et al., 2003). Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells play a vital role in limiting HSV infection and reactivation (Zhu et al., 2007). They can monitor HSV-1 gene expression in sensory neurons where the virus establishes lifelong latency (Iijima and Iwasaki, 2014). As for T cells, CD4+ T cells exhibited higher expression levels of genes associated with the TNF signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway, Nod-like receptor signaling pathway, and Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Additionally, upregulation of genes related to the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway was observed in NK cells. However, there was no evidence of exhaustion in terms of gene expression for circulating CD8+ T cells.

In order to explain some observations, we correlated them with the clinical conditions of the patients. For instance, compared with the other two patients, GHP3 and GHP4 exhibited higher numbers of classical monocytes (clusters 4 and 12) and fewer neutrophils (clusters 7 and 8) in the t-SNE plots (Fig. 1F). According to analyzing the time from the most recent herpes outbreak to blood sampling, we found that GHP3 had the shortest interval of 1 day, followed by GHP4 with 2 days, while both GHP1 and GHP2 had 5 days (Supplementary Table S1), with relatively alleviated lesions. These changes may be due to incomplete immune cell activation in the early phase, which may later result in an increase in neutrophil and monocyte activity, gradually alleviating genital herpes (Iijima et al., 2011). Experimental validation was also conducted to preliminarily confirm the scRNA-seq data. The results demonstrated that patients with genital herpes exhibited elevated levels of IFN-γ, IL-8, and soluble TLR-2 in their plasma compared to healthy controls. Additionally, qRT-PCR confirmed increased mRNA expression of certain inflammation and antiviral-related genes identified through scRNA-seq in GHP. These findings are consistent with the sequencing results. Furthermore, the proportions of monocytes and neutrophils were higher in the GHP group, suggesting that the impact of genital herpes on myeloid cells might be a factor contributing to the observed elevations of these markers in the blood.

Despite analyzing the state of immune cell subsets during recurrent genital herpes infections through single-cell sequencing, our study has some limitations, such as a small sample size of patients and poor consistency between the patient and control groups. Additionally, there was some intergroup variability in the data, making the association between the disease and certain observations relatively weak. However, unlike bulk RNA-seq, scRNA-seq detects RNA expression levels in individual cells, identifying functionally related cell groups across different samples through dimensional reduction and marker gene expression. This allows researchers to compare cell groups with the same function between the two groups and explore differences in the same cell types. The study requires validation in the future, such as large-scale clinical sample collection.

5. Conclusions

Overall, this study utilized single-cell sequencing to analyze changes in gene expression in peripheral blood immune cells of patients with recurrent genital herpes during the relapse period compared to healthy controls. In patients with recurrent genital herpes, inflammatory responses in peripheral blood immune cells can be activated, and genes related to cell metabolism, inflammatory signaling, and apoptosis process are up-regulated, suggesting that, in addition to immune cells that locally infiltrate the herpes lesion sites, peripheral blood immune cells may also play a significant role in the recurrence of genital herpes, particularly genes associated with the Toll-like receptor pathway, TNF signaling pathway, and IL-17 signaling pathway. This study provides a clinical single-cell atlas of peripheral blood immune cells during relapse in patients with recurrent genital herpes, offering new insights into potential immune changes of HSV infection.

Data availability

The original data presented in the study are included in the article and supplementary material. The raw sequence data reported in this paper are available in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) for human database (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA005450) and in the ScienceDB (https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.14155).

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China (study no. 20200106-14). Each participating patient and healthy control provided written informed consent. All experiments and sampling were carried out according to approved ethical and biosafety protocols following the Institutional guidelines. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Siji Chen: data curation, formal analysis, project administration, investigation, methodology, software, visualization, writing - original draft; Jiang Zhu: conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, resources, validation, funding acquisition; Chunting Hua: data curation, project administration, writing - reviewed&editing; Chenxi Feng: data curation, project administration; Xia Wu: formal analysis, writing - reviewed&editing; Can Zhou: data curation, methodology; Xianzhen Chen: formal analysis, resources; boya zhang: supervision, funding acquisition; Yaohan Xu: visualization, writing - reviewed&editing; Zeyu Ma: software, writing - reviewed&editing; Jianping He: writing - reviewed&editing; Na Jin: writing - reviewed&editing; Yinjing Song: data curation, conceptualization, supervision, project administration, writing - reviewed&editing, funding acquisition; Stijn van der Veen: supervision, methodology, writing - reviewed&editing; Hao Cheng: conceptualization, supervision, resources, project administration, investigation, writing - reviewed&editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 82471846, 82103740 and 82103743] and Medical Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province [grant number 2022RC198].

We are grateful to thank Hangzhou LC-BIO Co., Ltd for assisting in sequencing and bioinformatics analysis.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virs.2024.10.003.

Contributor Information

Yinjing Song, Email: 3315023@zju.edu.cn.

Stijn van der Veen, Email: stijnvanderveen@zju.edu.cn.

Hao Cheng, Email: chenghao1@zju.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Supplementary Figure S1.

The proportion of 31 subpopulations of immune cells in 8 donors. A The percentage of cells for 8 donors in each cluster. B The percentage of cells for 31 clusters in each donor. C t-SNE projections of single cell profile with each cell color-coded for cell clusters in different groups (GHP and HP). D t-SNE projections of the 8 sequenced samples colored for clusters showing repartition of the indicated cell populations.

Supplementary Figure S2.

Cells grouped by marker genes. A t-SNE projections of the 8 sequenced samples colored for groups showing repartition of the indicated cell populations. B Violin plots of genes from all samples used to identify cell types (T = T and NK cell group, B = B cell group, M = myeloid cell group). C Dot plots of genes used to identify cell types.

Supplementary Figure S3.

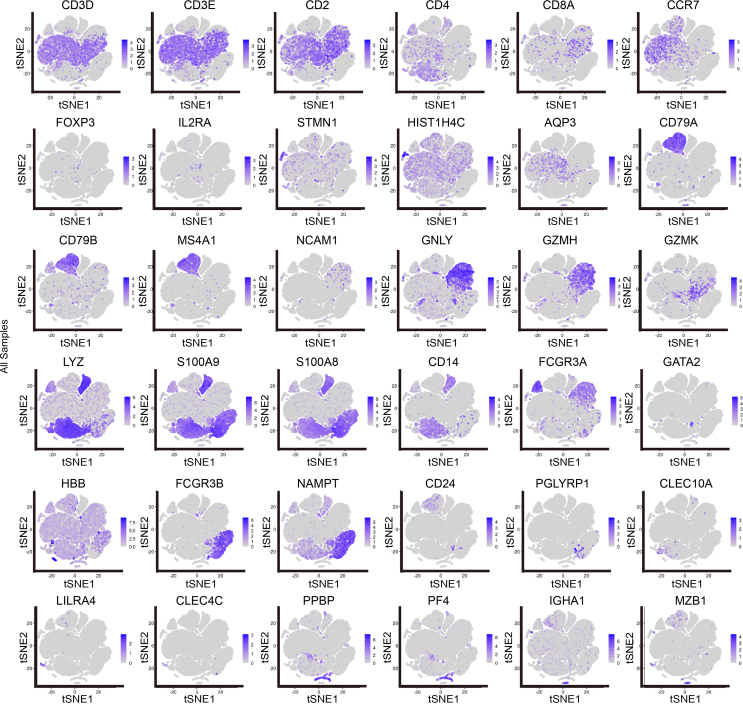

Expression of marker genes used to identify cell types. t-SNE projections of 36 marker genes showing expression in cell clusters.

Supplementary Figure S4.

DEGs in different cell types. Volcano plots display the upregulated genes (red) and downregulated genes (blue) of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, classical monocytes, B cells, neutrophils, and DCs.

Supplementary Figure S5.

GO terms and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of classical monocytes DEGs between the GHP and HP. A GO term enrichment analysis for the DEGs. B KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the DEGs.

Supplementary Figure S6.

GO terms and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of classical monocytes marker genes and DEGs of neutrophils between the GHP group and HP group. A GO term enrichment analysis of M2 and M3 DEGs show the distinct function of M2 (left) and M3 (right). B GO terms and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the DEGs in neutrophils.

Supplementary Figure S7.

The re-clustering analysis of DCs. A The fraction of re-clustering DC subsets for 8 donors in each cluster. B The fraction of re-clustering DC subsets for 6 clusters in each donor. C t-SNE projections of marker genes expression for DCs of all samples.

Supplementary Figure S8.

GO terms and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the DEGs between the HSV-2 infection and healthy genital skin samples from GSE#172423. A GO term enrichment analysis for the DEGs. B KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the DEGs.

References

- Adachi A., Honda T., Dainichi T., Egawa G., Yamamoto Y., Nomura T., Nakajima S., Otsuka A., Maekawa M., Mano N., Koyanagi N., Kawaguchi Y., Ohteki T., Nagasawa T., Ikuta K., Kitoh A., Kabashima K. Prolonged high-intensity exercise induces fluctuating immune responses to herpes simplex virus infection via glucocorticoids. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021;148:1575–1588.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara-Hernández M., Leylek R., Wagar L.E., Engleman E.G., Keler T., Marinkovich M.P., Davis M.M., Nolan G.P., Idoyaga J. High-dimensional phenotypic mapping of human dendritic cells reveals interindividual variation and tissue specialization. Immunity. 2017;47:1037–1050.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aran D., Looney A.P., Liu L., Wu E., Fong V., Hsu A., Chak S., Naikawadi R.P., Wolters P.J., Abate A.R., Butte A.J., Bhattacharya M. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20:163–172. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0276-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arduino P.G., Porter S.R. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 infection: overview on relevant clinico-pathological features. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2008;37:107–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., Ball C.A., Blake J.A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J.M., Davis A.P., Dolinski K., Dwight S.S., Eppig J.T., Harris M.A., Hill D.P., Issel-Tarver L., Kasarskis A., Lewis S., Matese J.C., Richardson J.E., Ringwald M., Rubin G.M., Sherlock G. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini M., Duchêne J., Santovito D., Schloss M.J., Evrard M., Winkels H., Aslani M., Mohanta S.K., Horckmans M., Blanchet X., Lacy M., von Hundelshausen P., Atzler D., Habenicht A., Gerdes N., Pelisek J., Ng L.G., Steffens S., Weber C., Megens R.T.A. PD-L1 expression on nonclassical monocytes reveals their origin and immunoregulatory function. Sci Immunol. 2019;4 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aar3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birzer A., Krawczyk A., Draßner C., Kuhnt C., Mühl-Zürbes P., Heilingloh C.S., Steinkasserer A., Popella L. HSV-1 modulates IL-6 receptor expression on human dendritic cells. Front. Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A., Hoffman P., Smibert P., Papalexi E., Satija R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:411–420. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W., Bover L. Signaling and ligand interaction of ILT7: receptor-mediated regulatory mechanisms for plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunol. Rev. 2010;234:163–176. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carty M., Reinert L., Paludan S.R., Bowie A.G. Innate antiviral signalling in the central nervous system. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-L., Gomes T., Hardman C.S., Vieira Braga F.A., Gutowska-Owsiak D., Salimi M., Gray N., Duncan D.A., Reynolds G., Johnson D., Salio M., Cerundolo V., Barlow J.L., McKenzie A.N.J., Teichmann S.A., Haniffa M., Ogg G. Re-evaluation of human BDCA-2+ DC during acute sterile skin inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2020;217(jem) doi: 10.1084/jem.20190811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K., Raghupathy N., Churchill G.A. A Bayesian mixture model for the analysis of allelic expression in single cells. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5188. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13099-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliffe A.R., Arbuckle J.H., Vogel J.L., Geden M.J., Rothbart S.B., Cusack C.L., Strahl B.D., Kristie T.M., Deshmukh M. Neuronal stress pathway mediating a histone methyl/phospho switch is required for herpes simplex virus reactivation. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;18:649–658. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins N., Hochheiser K., Carbone F.R., Gebhardt T. Sustained accumulation of antigen-presenting cells after infection promotes local T-cell immunity. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2017;95:878–883. doi: 10.1038/icb.2017.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey L., Handsfield H.H. Genital herpes and public health. JAMA. 2000;283:791. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.6.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulon P.-G., Roy S., Prakash S., Srivastava R., Dhanushkodi N., Salazar S., Amezquita C., Nguyen L., Vahed H., Nguyen A.M., Warsi W.R., Ye C., Carlos-Cruz E.A., Mai U.T., BenMohamed L. Upregulation of multiple CD8+ T cell exhaustion pathways is associated with recurrent ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J. Immunol. 2020;205:454–468. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danastas K., Guo G., Merjane J., Hong N., Larsen A., Miranda-Saksena M., Cunningham A.L. Interferon inhibits the release of herpes simplex virus-1 from the axons of sensory neurons. mBio. 2023;14 doi: 10.1128/mbio.01818-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanushkodi N.R., Prakash S., Srivastava R., Coulon P.-G.A., Arellano D., Kapadia R.V., Fahim R., Suzer B., Jamal L., Vahed H., BenMohamed L. Antiviral CD19+ CD27+ memory B cells are associated with protection from recurrent asymptomatic ocular herpesvirus infection. J. Virol. 2022;96 doi: 10.1128/jvi.02057-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong-Newsom P., Powell N.D., Bailey M.T., Padgett D.A., Sheridan J.F. Repeated social stress enhances the innate immune response to a primary HSV-1 infection in the cornea and trigeminal ganglia of Balb/c mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 2010;24:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzen-Röhl E., Schepis D., Lagrelius M., Franck K., Jones P., Liljeqvist J.-Å., Bergström T., Aurelius E., Kärre K., Berg L., Gaines H. Increased cell-mediated immune responses in patients with recurrent herpes simplex virus type 2 meningitis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:655–660. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00333-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman E.E., Weiss H.A., Glynn J.R., Cross P.L., Whitworth J.A., Hayes R.J. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. AIDS. 2006;20:73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198081.09337.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao D., Ciancanelli M.J., Zhang P., Harschnitz O., Bondet V., Hasek M., Chen J., Mu X., Itan Y., Cobat A., Sancho-Shimizu V., Bigio B., Lorenzo L., Ciceri G., McAlpine J., Anguiano E., Jouanguy E., Chaussabel D., Meyts I., Diamond M.S., Abel L., Hur S., Smith G.A., Notarangelo L., Duffy D., Studer L., Casanova J.-L., Zhang S.-Y. TLR3 controls constitutive IFN-β antiviral immunity in human fibroblasts and cortical neurons. J. Clin. Invest. 2021;131 doi: 10.1172/JCI134529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garand M., Goodier M., Owolabi O., Donkor S., Kampmann B., Sutherland J.S. Functional and phenotypic changes of natural killer cells in whole blood during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and disease. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:257. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissmann F., Jung S., Littman D.R. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with Distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves M.J. Genital herpes: a review. Am. Fam. Physician. 2016;93:928–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R., Warren T., Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet. 2007;370:2127–2137. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61908-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima N., Iwasaki A. Access of protective antiviral antibody to neuronal tissues requires CD4 T-cell help. Nature. 2016;533:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature17979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima N., Iwasaki A. A local macrophage chemokine network sustains protective tissue-resident memory CD4 T cells. Science. 2014;346:93–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1257530. (1979) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima N., Mattei L.M., Iwasaki A. Recruited inflammatory monocytes stimulate antiviral Th1 immunity in infected tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:284–289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005201108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James C., Harfouche M., Welton N.J., Turner K.M., Abu-Raddad L.J., Gottlieb S.L., Looker K.J. Herpes simplex virus: global infection prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020;98:315–329. doi: 10.2471/BLT.19.237149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Furumichi M., Sato Y., Ishiguro-Watanabe M., Tanabe M. KEGG: integrating viruses and cellular organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D545–D551. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna K.M., Bonneau R.H., Kinchington P.R., Hendricks R.L. Herpes simplex virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells are selectively activated and retained in latently infected sensory ganglia. Immunity. 2003;18:593–603. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00112-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto Y., Linehan M., Weinstein J.S., Laidlaw B.J., Craft J.E., Iwasaki A. CD301b+ dermal dendritic cells drive T helper 2 cell-mediated immunity. Immunity. 2013;39:733–743. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A., Nikolich-Žugich J. Development and migration of protective CD8+ T cells into the nervous system following ocular herpes simplex virus-1 infection. J. Immunol. 2005;174:2919–2925. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebratti T., Lim Y.S., Cofie A., Andhey P., Jiang X., Scott J., Fabbrizi M.R., Ozantürk A.N., Pham C., Clemens R., Artyomov M., Dinauer M., Shin H. A sustained type I IFN-neutrophil-IL-18 axis drives pathology during mucosal viral infection. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.65762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenart M., Działo E., Kluczewska A., Węglarczyk K., Szaflarska A., Rutkowska-Zapała M., Surmiak M., Sanak M., Pituch-Noworolska A., Siedlar M. miRNA regulation of NK cells antiviral response in children with severe and/or recurrent herpes simplex virus infections. Front. Immunol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.589866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leylek R., Alcántara-Hernández M., Lanzar Z., Lüdtke A., Perez O.A., Reizis B., Idoyaga J. Integrated cross-species analysis identifies a conserved transitional dendritic cell population. Cell Rep. 2019;29:3736–3750.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind L., Svensson A., Thörn K., Krzyzowska M., Eriksson K. CD8+ T cells in the central nervous system of mice with herpes simplex infection are highly activated and express high levels of CCR5 and CXCR3. J. Neurovirol. 2021;27:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00940-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod B.L., Bedoui S., Hor J.L., Mueller S.N., Russell T.A., Hollett N.A., Heath W.R., Tscharke D.C., Brooks A.G., Gebhardt T. Distinct APC subtypes drive spatially segregated CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell effector activity during skin infection with HSV-1. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss N.J., Magaret A., Laing K.J., Kask A.S., Wang M., Mark K.E., Schiffer J.T., Wald A., Koelle D.M. Peripheral blood CD4 T-cell and plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC) reactivity to herpes simplex virus 2 and pDC number do not correlate with the clinical or virologic severity of recurrent genital herpes. J. Virol. 2012;86:9952–9963. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00829-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L., Xi Y., Upham J.W. CLEC4C gene expression can be used to quantify circulating plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Immunol. Methods. 2019;464:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posavad C.M., Koelle D.M., Shaughnessy M.F., Corey L. Severe genital herpes infections in HIV-infected individuals with impaired herpes simplex virus-specific CD8 + cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:10289–10294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samudio I., Rezvani K., Shaim H., Hofs E., Ngom M., Bu L., Liu G., Lee J.T.C., Imren S., Lam V., Poon G.F.T., Ghaedi M., Takei F., Humphries K., Jia W., Krystal G. UV-inactivated HSV-1 potently activates NK cell killing of leukemic cells. Blood. 2016;127:2575–2586. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-639088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer J.T., Corey L. Rapid host immune response and viral dynamics in herpes simplex virus-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2013;19:280–288. doi: 10.1038/nm.3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzkopff F., Petersen F., Grimm T.A., Brandt E. CXC chemokine ligand 4 (CXCL4) down-regulates CC chemokine receptor expression on human monocytes. Innate Immun. 2012;18:124–139. doi: 10.1177/1753425910388833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Q., Wu F., Liu Tong, Wang W., Liu Tianli, Jin X., Xu L., Ma Y., Huang G., Chen Z. JieZe-1 alleviates HSV-2 infection-induced genital herpes in Balb/c mice by inhibiting cell apoptosis via inducing autophagy. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.775521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D., Sharma S., Akojwar N., Dondulkar A., Yenorkar N., Pandita D., Prasad S.K., Dhobi M. An insight into current treatment strategies, their limitations, and ongoing developments in vaccine technologies against herpes simplex infections. Vaccines. 2023;11:206. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11020206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth P.M., Sunderji S., Shin L.Y.Y., Rebbapragada A., Huibner S., Kimani J., MacDonald K.S., Ngugi E., Bwayo J.J., Moses S., Kovacs C., Loutfy M., Kaul R. Coinfection with herpes simplex virus type 2 is associated with reduced HIV-specific T cell responses and systemic immune activation. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;197:1394–1401. doi: 10.1086/587697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H., Kumamoto Y., Gopinath S., Iwasaki A. CD301b+ dendritic cells stimulate tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells to protect against genital HSV-2. Nat. Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.B., Herbert J.J., Truong N.R., Cunningham A.L. Cytokines and chemokines: the vital role they play in herpes simplex virus mucosal immunology. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.936235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sozzani S., Vermi W., Del Prete A., Facchetti F. Trafficking properties of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in health and disease. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart T., Butler A., Hoffman P., Hafemeister C., Papalexi E., Mauck W.M., Hao Y., Stoeckius M., Smibert P., Satija R. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell. 2019;177:1888–1902.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suomalainen M., Greber U.F. Virus infection variability by single-cell profiling. Viruses. 2021;13:1568. doi: 10.3390/v13081568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiecki M., Wang Y., Gilfillan S., Colonna M. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells contribute to systemic but not local antiviral responses to HSV infections. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triana S., Stanifer M.L., Metz-Zumaran C., Shahraz M., Mukenhirn M., Kee C., Serger C., Koschny R., Ordoñez-Rueda D., Paulsen M., Benes V., Boulant S., Alexandrov T. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals immune response of intestinal cell types to viral infection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2021;17:e9833. doi: 10.15252/msb.20209833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong N.R., Smith J.B., Sandgren K.J., Cunningham A.L. Mechanisms of immune control of mucosal HSV infection: a guide to rational vaccine design. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:373. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuddenham S., Hamill M.M., Ghanem K.G. Diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections. JAMA. 2022;327:161. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.23487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villani A.-C., Satija R., Reynolds G., Sarkizova S., Shekhar K., Fletcher J., Griesbeck M., Butler A., Zheng S., Lazo S., Jardine L., Dixon D., Stephenson E., Nilsson E., Grundberg I., McDonald D., Filby A., Li W., De Jager P.L., Rozenblatt-Rosen O., Lane A.A., Haniffa M., Regev A., Hacohen N. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science. 2017;356 doi: 10.1126/science.aah4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C., Luo Z., Li W., Li X., Dallmann R., Kurihara H., Li Y.-F., He R.-R. Disturbed Yin–Yang balance: stress increases the susceptibility to primary and recurrent infections of herpes simplex virus type 1. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2020;10:383–398. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.-A., Raftery M.J., Hamann L., Guerreiro M., Grütz G., Haase D., Unterwalder N., Schönrich G., Schumann R.R., Volk H.-D., Scheibenbogen C. Association of TLR3-hyporesponsiveness and functional TLR3 L412F polymorphism with recurrent herpes labialis. Hum. Immunol. 2012;73:844–851. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiner P.S., Preusse C., Blank A., Zachskorn C., Baumgarten P., Caspary L., Braczynski A.K., Weissenberger J., Bratzke H., Reiß S., Pennartz S., Winkelmann R., Senft C., Plate K.H., Wischhusen J., Stenzel W., Harter P.N., Mittelbronn M. MIF receptor CD74 is restricted to microglia/macrophages, associated with a M1-polarized immune Milieu and prolonged patient survival in Gliomas. Brain Pathol. 2015;25:491–504. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Koelle D.M., Cao J., Vazquez J., Huang M.L., Hladik F., Wald A., Corey L. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells accumulate near sensory nerve endings in genital skin during subclinical HSV-2 reactivation. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:595–603. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are included in the article and supplementary material. The raw sequence data reported in this paper are available in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) for human database (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA005450) and in the ScienceDB (https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.14155).