Abstract

This study explored the effects of training weight and amplitude in whole-body vibration (WBV) on exercise intensity, indicated by oxygen consumption (VO2) and heart rate. In LOAD-study: ten participants performed squats under non-WBV and WBV (30 Hz 2 mm) conditions at 0%, 40%, and 80% bodyweight (BW). In AMPLITUDE-study: eight participants performed squats under non-WBV, low-amplitude WBV (30 Hz 2 mm), and high-amplitude WBV (30 Hz 4 mm) conditions with 0% and 40%BW. heart rate and VO2 were continuously recorded. Metabolic equivalents (METs) for WBV squats with 0–40% BW were ~ 3.8–5.3, and ~ 7.3 for 80% BW. LOAD-study presented a significant vibration × training weight interaction effect for in-exercise VO2 (F = 3.171, P = 0.05, ηp2 = 0.105) and post-exercise VO2 (F = 4.156, P = 0.021, ηp2 = 0.133). In-exercise VO2 of 80%BW squat (P < 0.001) and post-exercise VO2 of both 40% (P = 0.049) and 80%BW squat (P < 0.001) under WBV were significantly higher than those under non-WBV. AMPLITUDE-study presented no significant amplitude × training weight interaction effect for VO2 and heart rate (P > 0.05). WBV squats are moderate-to-vigorous intensity exercise. 30 Hz 2 mm WBV is sufficient for evoking superior oxygen consumption during and after exercise under certain training weight, the response of heart rate to WBV was less pronounced. Increasing training weight could elicit greater oxygen consumption and heart rate under WBV condition.

Keywords: Whole body vibration, Metabolic equivalent, Oxygen consumption, Heart rate, Exercise prescription

Subject terms: Cardiovascular biology, Metabolism, Public health

Scientific research highlighted that whole-body vibration (WBV) combined with resistance exercise positively affects neuromuscular performance and cardiovascular function1–3. Vibration stimulation generated by WBV plate can activate muscle spindles and alpha-motor neuron4, promote blood circulation and reduce arterial stiffness3,5. Squatting targets multiple muscle group, and mimics daily physical activities, such as walking, running, jumping6,7, which is often combined with WBV to augment its health benefits. Previous studies also demonstrated that WBV squat can release lower back pain8, increase lower limb strength9, and improve exercise metabolism10. However, less studies evaluated the intensity of WBV squat.

The intensity of WBV squat primarily determined by vibration amplitude, vibration frequency, as well as the load lifted in the training session, which is typically represented by percentage of bodyweight (%BW)9,11,12, but people cannot calculate the exact intensity of WBV squat based on these parameters, or compare its intensity with other physical activities, which may increase the risk of sports injury when applying WBV squat. The metabolic equivalent (MET) refers to the ratio of the oxygen consumption rate during work relative to a standard resting state, which can differentiate exercise intensity from the perspective of energy metabolism13, but less studies calculated the MET of WBV exercise. In addition, previous studies reported a positive relationship between frequency and VO214,15, the vibration frequency at or greater than 30 Hz is recommended by previous studies in terms of muscle power and strength16–18, but the impact of vibration amplitude and training weight on the VO2 of WBV squats was inconsisten, this may because training variables are diverse in different studies. Serravite et al.10. found 35 Hz 2–3 mm and 50 Hz 5–7 mm could only significantly increase VO2 of 20%BW squat, while no significant increase in 0%BW and 40%BW squat. Bertucci et al.19. reported that 2 mm amplitude effectively increased VO2 for 50%BW squat, while no significant increase existed with 4 mm amplitude. However, Rittweger et al.20. and Kang et al.15. found increasing vibration amplitude induced a greater VO2 for non-weight bearing squat, even though the vibration types were different (side-alternating20 vs. synchronous15), Kang et al.21. also showed that an amplitude smaller than 2 mm could not lead to a significant increase in VO2 for a non-weight bearing squat. On the other hand, although heart rate is a common indicator for monitoring exercise intensity and is strongly correlated with VO2, relevant research has reported no significant increase in exercise heart rate when vibration intervention was applied15,21. Some studies attributed this finding to the blood flow acceleration and the reduced peripheral resistance provoked by WBV22–24, suggesting that vibration stimulation may not exert excessive pressure on the cardiovascular system. However, relevant studies mainly adopted non-weight bearing squat, vibration effect on the exercise heart rate under higher training weights is still unknown.

Therefore, this study was undertaken to calculate MET of WBV squat and analyze VO2 and heart rate response, for the purpose of assessing the intensity of WBV squat with varying vibration amplitudes and training weights, and improving the safety and efficacy of WBV squat prescription.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

The ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Experimentation of the local university [2019085 H]. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration. All participants included in this study signed the paper version of informed consent form after a detailed experimental explanation. The experimental procedure followed the WBV research consensus published in 202125, all necessary information is reported, including subject information, vibration category and equipment type, vibration frequency and amplitude, exercise movement and protocol, adverse effect.

Subjects

The sample size and experimental design was determined according to previous research. Rittweger et al.20. investigated the effect of vibration amplitude, frequency and training load (side-alternative WBV) with 8–10 subjects by conducting three different parts. Serravite et al.10 also reported that a required sample size of 5 subjects is necessary for 3(training load) × 3(WBV intensity) experiment. A power analysis based on the result of Serravite et al.10 (effect size f = 0.79, ηpartial2 = 0.387, power = 0.95) was calculated by GPower 3.1to reconfirm the required sample size. Healthy and active male students with no WBV training experience were recruited by convenient sampling from a local university (10 subjects in LOAD-study, 8 subjects in AMPLITUDE-study). The physical characteristics of the subjects and the exercise conditions of LOAD-study and AMPLITUDE-study are presented in Table 1. No participant withdrew or experienced adverse effect.

Table 1.

Characteristic of subjects and exercise conditions of LOAD-study and AMPLITUDE-study.

| n | Gender | Age (yr) | Height (cm) | Body weight (kg) | Vibration parameters | Training weights | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOAD | 10 | Male | 23.8 ± 1.6 | 177.3 ± 4.3 | 73.3 ± 3.5 | Non-vibration (CON), 30 Hz 2 mm | 0%, 40%, 80% bodyweight | ||

| AMPLITUDE | 8 | Male | 25.1 ± 1.6 | 178.8 ± 4.6 | 75.7 ± 3.7 | Non-vibration (CON), 30 Hz 2 mm, 30 Hz 4 mm | 0%, 40% bodyweight | ||

CON Squat without whole-body vibration.

The inclusion criteria for participants were: (1) enabled to master the squatting skill properly with at least 1-year strength training experience; (2) no history of cardiovascular and neuromuscular disease, no orthopedic injury or any metabolic syndrome that might prohibit exercise. The exclusion criteria for participants were: (1) cardiovascular and neuromuscular disease, or metabolic conditions that might prohibit exercise; (2) lower limb surgery within the previous six months; (3) any contraindications to WBV according to the manufacturer’s criteria (i.e. acute inflammations, gallstones, diabetes, epilepsy, kidney stones, joint problems, cardiovascular diseases, tumors, joint implants, recent thrombosis, recent operative wounds, or intense migraines).

Procedures

We firstly recruited participants and completed LOAD-study, proceeding to AMPLITUDE-study upon its completion. All personnel involved in the procedures were familiarized with the experimental procedure and WBV operating methods. There were seven testing visits of each participant for both two parts in the laboratory. The first visit was to measure the physical characteristics, to obtain informed consent following explanation of the study. To minimize the impact of proficiency and individual stiffness on the experimental results, subjects were also asked to familiarize themselves with the WBV squat and equipment, e.g., WBV platform, metabolic chart, facemask, In the following six formal testing visits, all participants were required to refrain from strenuous physical activity, alcohol, and caffeine for 48 h prior the testing day and to avoid any food except water for at least 2 h before the experiment in the testing day. The interval between each two visits was at least 48 h.

In LOAD-study, subjects performed non-WBV (CON) or WBV (30 Hz 2 mm) barbell squats with 0%, 40% and 80% bodyweight (BW) training weight during each of six exercise protocols, conducting in six formal testing visits respectively. In AMPLITUDE-study, the subjects performed non-WBV (CON), low-amplitude WBV (30 Hz 2 mm), and high-amplitude WBV (30 Hz 4 mm) squats with 0% and 40%BW training weight in six formal testing visits. To mitigate potential order effect, we randomized the order of experimental groups by drawing lots, the rest interval between each two groups was at least 48 h.

For LOAD-study and AMPLITUDE-study, we used a synchronous vertical WBV plate (Model Pro-5, Power Plate, USA) to conduct each exercise protocol. The oxygen consumption during exercise (in-exercise VO2) and post-exercise VO2 were collected by gas analyzer (Cortex MetalyzerII, CORTEX Biophysik, Leipzig, Germany), and in-exercise and post-exercise heart rate by heart rate belt (Polar T31, Polar Electro, Finland). The gas analyzer was calibrated by using standard gas once a week. The beginning and end points of each phase (rest, in- and post-exercise) were recorded, and data was exported every 10 s. The experiment was conducted in a quiet and well-ventilated room. The room temperature was controlled by air-conditioner and set at 25℃ for 30 min before the experiment26,27. Subject performed the squat training with the same clothes and shoes across all conditions.

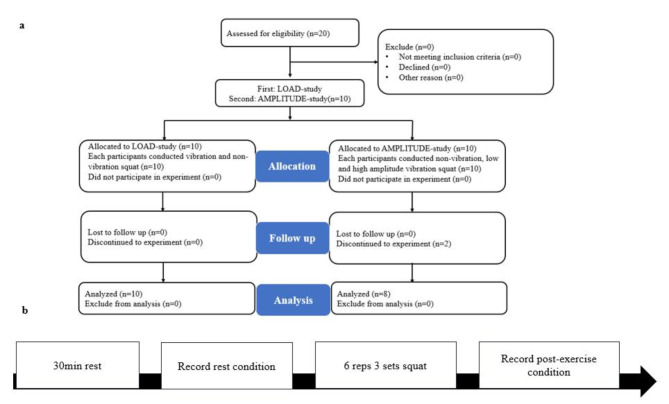

After arriving at the laboratory, the subjects rested for at least 30 min, and then wore metabolic mask and connected heart rate belt. VO2 and heart rate was collected throughout the experiment. The resting condition measurement period could be a minimum of 10 min and the last 5-min segment was recorded as the resting value28. Afterwards six sets of 30-s active squat were performed at a speed of one squat per 3 s (1.5 s up, 1.5 s down) (measured by a metronome) on the WBV plate. To ensure high-quality movement, the subjects were instructed to perform parallel squats with the entire foot on the ground, with the range of motion controlled by setting a horizontal stick as a limit at the lower end of the motion for subject reference15. A 1-min period of recovery was provided between sets. Total duration of training session is 8 min (exercise + rest interval). The first set was treated as warm-up, VO2 and heart rate of the other 5 sets (totally 6.5 min) were recorded as the in-exercise data. After completing the exercise, post-exercise VO2 of subjects was recorded for 15 min29. The heart rate within 1 min immediately after exercise was recorded as the post-exercise heart rate. The resting values, recovery and post-exercise data were all record in a seated position on the same chair. Experimental procedure is presented in Fig. 1, including experimental flowchart and exercise protocol.

Fig. 1.

Experimental procedure. a Experimental flowchart. b Exercise protocol.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by SPSS 24.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) and expressed as means ± standard deviation or otherwise mentioned. Two-way ANOVA was used in LOAD-study and AMPLITUDE-study to determine the vibration × training weight and amplitude × training weight effect respectively on in-exercise and post-exercise VO2, in-exercise and post-exercise heart rate, followed by post-hoc pairwise comparison where appropriate. Statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Partial eta squared (ηp2) statistics were analyzed for each ANOVA, with 0.01, 0.06, and 0.15 corresponding to small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively30. Similarly, Cohen’s d was calculated to quantify the magnitude of differences of training conditions across different training weights. The absolute values of the effect size were interpreted as trivial (d < 0.2), small (0.2 ≤ d < 0.6), moderate (0.6 ≤ d < 1.2), large (1.2 ≤ d < 2), very large (2 ≤ d < 4), and extremely large31.

Results

LOAD-study

The MET values at squat for 0% and 40%BW were 3.7 ± 0.3 and 4.9 ± 0.4 under CON condition, 3.8 ± 0.4 and 5.3 ± 0.6 under WBV condition (30 Hz 2 mm), corresponding to moderate intensity; the MET values for squats at 80% BW was 6.4 ± 0.4 under CON condition, and 7.3 ± 0.7 under WBV condition, equal to vigorous exercise intensity13.

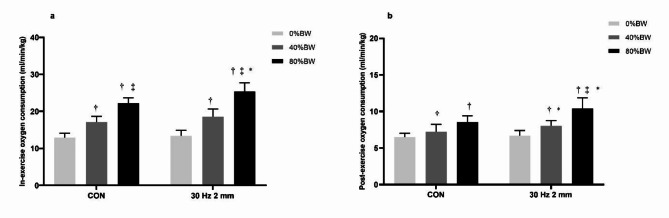

In-exercise oxygen consumption

The vibration × training weight interaction effect was significant for in-exercise VO2 (F = 3.171, P = 0.05, ηp2 = 0.105) as shown in Fig. 2. Subsequent analysis demonstrated that in-exercise VO2 for 80%BW squat under WBV condition was significantly higher than that under CON condition (P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.6). In-exercise VO2 also significantly increased with the increase of training weights (0%<40%<80%BW under either CON or WBV conditions, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d > 2.0).

Fig. 2.

In-exercise oxygen consumption and excess post-exercise oxygen consumption in LOAD-study. Interaction effect of vibration x training weight for in-exercise oxygen consumption (F = 3.171, P = 0.05, ηp2 = 0.105) and excess post-exercise oxygen consumption (F = 4.156, P = 0.021, ηp2 = 0.133). %BW: percent of body weight; CON: squat without whole-body vibration. †: oxygen consumption was significantly higher than 0%BW squat. ‡: oxygen consumption was significantly higher than 40%BW squat. *: oxygen consumption was significantly higher than that in CON group.

Post-exercise oxygen consumption

The vibration × training weight interaction effect was significant for post-exercise VO2 (F = 4.156, P = 0.021, ηp2 = 0.133) as shown in Fig. 2. Pairwise comparison results showed that post-exercise VO2 for both 40%BW (P = 0.049, Cohen’s d = 0.9) and 80%BW squat in WBV condition were significantly higher than those under CON condition (P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.6). The post-exercise VO2 for 80%BW squat was significantly higher than 40%BW and 0%BW squat in CON condition. The post-exercise VO2 of WBV squat also significantly increased with training weights in (0%<40%<80%BW, P < 0.01, Cohen’s d > 1.2).

In-exercise heart rate

For the in-exercise heart rate, there was no significant vibration × training weight interaction effect (F = 0.252, P = 0.778, ηp2 = 0.013) and no significant vibration main effect (F = 2.16, P = 0.15, ηp2 = 0.052), while the training weight main effect reached to a significant level (F = 33.403, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.631). As displaced in Table 2, the effect size of WBV under each training weight ranged from 0.2 to 0.6, in correspondence to a small effect.

Table 2.

LOAD-study-heart rate (beats/min) response to training weight with or without whole-body vibration in-/post-exercise (n = 10).

| Rest | In-exercisea | Post-exerciseb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | 30 Hz 2 mm | CON | 30 Hz 2 mm | Mean difference (95%CI)c | Cohen’s d | CON | 30 Hz 2 mm | Mean difference (95% CI)c | Cohen’s d | |

| 0%BW | 62 ± 11 | 64 ± 7 | 86 ± 10 | 88 ± 8 | 2.35 (− 10.30, 14.99) | 0.2 | 92 ± 11 | 89 ± 10 | − 2.90 (− 16.88, 11.08) | 0.3 |

| 40%BW | 61 ± 8 | 60 ± 8 | 102 ± 10 | 108 ± 19 | 6.65 (− 8.96, 22.26) | 0.4 | 108 ± 10 | 114 ± 22 | 6.50 (− 7.48, 20.48) | 0.4 |

| 80%BW | 62 ± 8 | 62 ± 8 | 121 ± 15 | 130 ± 13 | 8.82 (− 5.23, 22.88) | 0.6 | 135 ± 17 | 134 ± 19 | − 0.77 (− 15.14, 13.60) | 0.1 |

CON, squat without whole-body vibration. %BW, percent of body weight.

Cohen’s d is interpreted as trivial (d < 0.2), small (0.2 ≤ d < 0.6), moderate (0.6 ≤ d < 1.2), large (1.2 ≤ d < 2), very large (2 ≤ d < 4), and extremely large.

ainteraction effect of vibration x training weight, F= 0.252, P = 0.778, ηp2 = 0.013.

bF = 0.498, P = 0.611, ηp2 = 0.018.

cMean difference between conditions with or without whole-body vibration (95% confidence interval).

Post-exercise heart rate

The post-exercise heart rate data demonstrated no vibration × training weight interaction effect (F = 0.498, P = 0.611, ηp2 = 0.018) and no vibration main effect (F = 0.054, P = 0.817, ηp2 < 0.001), while the main effect of training weight reached a significant level (F = 39.408, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.598). As displaced in Table 2, the effect size of WBV under each training weight ranged from 0.1 to 0.4, equivalent to a trivial to small effect.

AMPLITUDE-study

The MET values for squats at 0% and 40% BW were 3.5 ± 0.5 and 4.5 ± 0.6 under CON conditions, 3.9 ± 0.8 and 5.3 ± 0.9 under 30 Hz 2 mm WBV conditions, and 4.1 ± 0.6 and 5.3 ± 1.0 under 30 Hz 4 mm WBV conditions, corresponding to moderate intensity13.

In-exercise oxygen consumption

The amplitude × training weight interaction effect was not significant for in-exercise VO2 (F = 0.302, P = 0.741, ηp2 = 0.015), while both the amplitude (F = 4.003, P = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.163) and training weight (F = 29.983, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.422) main effects were significant. As displaced in Table 3, the effect sizes of 30 Hz 2 mm and 30 Hz 4 mm WBV under each training weight were 0.6-1.0 (moderate effect) and 1.0 (moderate effect), respectively.

Table 3.

AMPLITUDE-study-oxygen consumption (ml/min/kg) response to vibration amplitude and training weight in-/post-exercise (n = 8).

| Rest | In-exercisea | Post-exerciseb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | 30 Hz 2 mm | 30 Hz 4 mm | CON | 30 Hz 2 mmc | 30 Hz 4 mmc | CON | 30 Hz 2 mmc | 30 Hz 4 mm c | |

| 0%BW | 4.49 ± 0.48 | 4.44 ± 0.6 | 4.33 ± 0.41 | 12.28 ± 1.86 |

13.64 ± 2.83 [1.36 (− 1.29, 4.01); 0.6] |

14.35 ± 2.23 [2.07 (− 0.58, 4.72); 1.0] |

5.51 ± 0.50 |

5.96 ± 0.83 [0.45 (− 0.37, 1.47); 0.7] |

6.42 ± 0.76 [0.93 (0.01, 1.85); 1.4] |

| 40%BW | 4.57 ± 0.45 | 4.61 ± 0.71 | 4.49 ± 0.49 | 15.74 ± 2.04 |

18.54 ± 3.10 [1.31 (0.15, 5.45); 1.0] |

18.58 ± 3.45 [2.85 (0.10, 5.59); 1.0] |

6.69 ± 0.59 |

7.61 ± 1.31 [0.91 (− 0.01, 1.83); 0.9] |

7.43 ± 1.22 [0.75 (0.20, 1.70); 0.8] |

CON, squat without whole-body vibration; %BW, percent of body weight.

Cohen’s d is interpreted as trivial (d< 0.2), small (0.2 ≤ d< 0.6), moderate (0.6 ≤ d< 1.2), large (1.2 ≤d< 2), very large (2≤d< 4), and extremely large.

aInteraction effect of amplitude x training weight, F= 0.302, P= 0.741, ηp2= 0.015.

bF= 0.521, P= 0.598, ηp2= 0.025.

cValues represents means ± SD [Mean difference when comparing with control condition without whole-body vibration (95% confidence interval); Cohen’s d].

Post-exercise oxygen consumption

The amplitude × training weight interaction effect was not significant for post-exercise VO2 (F = 0.521, P = 0.598, ηp2 = 0.025), while both the amplitude (F = 3.727, P = 0.033, ηp2 = 0.154) and training weight (F = 23.255, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.362) main effects were significant. As displaced in Table 3, the effect sizes of 30 Hz 2 mm and 30 Hz 4 mm WBV under each training weight were 0.7–0.9 (moderate effect) and 0.8–1.4 (moderate to large effect), respectively.

In-exercise heart rate

The amplitude × training weight interaction effect (F = 0.068, P = 0.934, ηp2 = 0.004) and the amplitude main effect (F = 0.218, P = 0.805, ηp2 = 0.011) were not significant for in-exercise heart rate, but a significant training weight main effect was detected (F = 18.853, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.332). As displaced in Table 4, the effect size was 0.1 (trivial effect) for 30 Hz 2 mm WBV; 0.1–0.3 (trivial to small effect) for 30 Hz 4 mm WBV.

Table 4.

AMPLITUDE-study-heart rate (beats/min) response to vibration amplitude and training weight in-/post-exercise (n = 8).

| Rest | In-exercisea | Post-exerciseb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | 30 Hz 2 mm | 30 Hz 4 mm | CON | 30 Hz 2 mm c | 30 Hz 4 mmc | CON | 30 Hz 2 mmc | 30 Hz 4 mmc | |

| 0%BW | 62 ± 8 | 61 ± 12 | 60 ± 9 | 83 ± 10 |

82 ± 9 [– 0.73 (– 10.62, 9.15); 0.1] |

84 ± 10 [0.79 (– 9.10,10.68); 0.1] |

89 ± 9 |

91 ± 11 [1.26 (– 8.46, 10.98); 0.2] |

92 ± 9 [3.15 (– 6.24, 12.54); 0.3] |

| 40%BW | 62 ± 9 | 62 ± 9 | 63 ± 6 | 94 ± 12 |

95 ± 8 [1.00 (– 9.89, 11.89); 0.1] |

97 ± 6 [3.25 (– 6.30, 12.80); 0.3] |

101 ± 12 |

106 ± 8 [4.63 (– 4.76, 14.01); 0.5] |

108 ± 4 [6.57 (– 3.14, 16.29); 0.8] |

CON, squat without whole-body vibration. %BW, percent of body weight.

Cohen’s d is interpreted as trivial (d< 0.2), small (0.2 ≤d< 0.6), moderate (0.6 ≤d<1.2), large (1.2≤d<2), very large (2≤d< 4), and extremely large.

aInteraction effect of amplitude x training weight, F= 0.068, P= 0.934, ηp2= 0.004.

bF= 0.174, P= 0.841, ηp2= 0.009.

cValues represents means ± SD [Mean difference when comparing with control condition without whole-body vibration (95% confidence interval); Cohen’s d].

Post-exercise heart rate

The amplitude × training weight interaction effect (F = 0.174, P = 0.841, ηp2 = 0.009) and the amplitude main effect (F = 1.077, P = 0.350, ηp2 = 0.051) were not significant for post-exercise heart rate, but a significant main effect was detected for training weight (F = 26.608, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.399). As displaced in Table 4, the effect size was 0.2–0.5 (small effect) for 30 Hz 2 mm WBV; 0.3–0.8 (small to moderate effect) for 30 Hz 4 mm WBV.

Discussion

It has been demonstrated in this study that WBV could evoke superior VO2 during and after exercise under certain training weight, and increasing training weight could also yield greater VO2 under WBV conditions. However, the response of heart rate to WBV was less pronounced. Our study therefore suggests a combination of vibration intervention and training weight increase to increasing exercise intensity and exergy expenditure. For the individual who cannot bear too much training weight due to cardiovascular diseases, such as arteriosclerosis and hypertension, vibration intervention may be a feasible method. In addition, the selection for training weights should be done carefully, as WBV squats with 80% BW in our study could reached vigorous intensity (with METs of 7.3 ± 0.7).

LOAD-study demonstrated a significant vibration × training weight interaction effect for in-exercise VO2. WBV (30 Hz 2 mm) could significantly increase in-exercise VO2 for 80%BW squat, and its effect was approximate to a significant level for 40%BW squat (P = 0.085). This result indicates that WBV (30 Hz 2 mm) may evoke greater in-exercise VO2 with higher training weight, and a significant level may be observed when the training weight reaches 80%BW. However, AMPLITUDE-study found no further increase in in-exercise VO2 after increasing the amplitude from 2 mm to 4 mm, with a moderate effect size observed for both conditions when a 40% BW training weight was applied (d = 1.0 for both two conditions abovementioned). This finding can be explained by the synergistic interaction between weight bearing and amplitude. The rapid vibration generated by the vibration platform reduces squat stability during exercise, but expose participants to a hyper-gravitational stimulus, which can increase the conversion intensity from centrifugal contraction to centripetal contraction32. Increasing the vibration amplitude from 2 mm to 4 mm further impairs the squat stability and intensifies the hyper-gravity. Thus, an intense squat in this condition may be more prone to sensitize fast muscle fibers that is known to have a low oxidative and high glycolytic capacity. This propriety could explain why in-exercise VO2 was not significantly increased with 4 mm amplitude. A study by Giunta et al.33. also supports this opinion, presenting that WBV significantly increased the blood lactate of weight-bearing [16–20 kg] squat in healthy individuals. For the obese, the blood lactate after WBV training was also significantly higher than that under the CON condition34. Relevant studies also suggested that a higher amplitude might be more effective in activating fast-twitch fibers. Marín et al.35. found that a 4 mm amplitude significantly outperformed a 2 mm amplitude in improving the isokinetic force at a high speed (270°/s). Hazell et al.36. found that the EMG levels in the lower limbs during WBV training with a 4 mm amplitude were significantly higher than those with a 2 mm amplitude. Lienhard et al.9. also presented a similar result in weight-bearing training [0–33 kg] with lower amplitudes (1.2 mm vs. 2 mm).

On the other hand, we found the in-exercise VO2 rose gradually with the increase in amplitude when subjects performed non-weight bearing squat, the effect size rose from 0.6 to 1.0, but it did not reach a significant level. Relevant studies demonstrated that WBV with higher frequency might be more beneficial for increasing in-exercise VO2. Kang J et al.15. found 50 Hz significantly increased VO2 with both 2 mm and 4 mm. Avelar et al.37. found 40 Hz could elicit greater VO2 with 4 mm amplitude. However, our study still recommends a frequency of 30 Hz combined with 2–4 mm amplitude for a beginner, because the effectiveness of WBV approximate to this combination on various aspects has already been proven by meta-analysis in recent years, such as improving body composition38, increasing bone mineral density39 and flexibility40, and increasing frequency rashly may induce a steeply increase in vibration intensity (vibration acceleration is directly proportional to the vibration frequency), which may increase the risk of sports injury.

Post-exercise VO2 is known to be strongly correlated with training intensity and the fatigue elicited by resistance training29,41. A previous study also presented that the accuracy in assessing the intensity of push-ups, lunge squats, and pull-ups by using post-exercise VO2 was higher than using in-exercise VO242. However, fewer studies have explored the effects of vibration and training weight on the intensity of WBV squat as measured by post-exercise VO2. Our study presented a significant vibration × training weight interaction effect for post-exercise VO2 in LOAD-study and found a significant vibration [30 Hz 2 mm] effect for 40%BW and 80%BW squat, the increase of post-exercise VO2 was the most pronounced in 80%BW condition. This result proves the effectiveness of WBV for increasing post-exercise VO2, and indicates that training weight increase may expand the vibration effect on increasing post-exercise VO2.

Both vibration stimulation and training weight increase provoked greater in-exercise and post-exercise VO2, but the response of heart rate to WBV was less pronounced, this may be related with the vasodilatory effect of WBV. Vibration stimulation could increase the blood flow velocity, the shear force between the blood flow and vascular endothelium also triggers the release of endothelium derived relaxing factor, which can relax the vessels and reduce the peripheral resistance of the blood circulation, potentially promoting the energy supply of the aerobic metabolic pathway23,24.

Strength and limitation of study

Previous research less studied the WBV squat intensity, our study explored the synergistic interaction between training weight and vibration amplitude on WBV squat intensity from the perspective of metabolic equivalent and heat rate response, which could provide reference for WBV prescription. Oxygen consumption rate of WBV squat was also analyzed, this could help people calculated the aerobic energy expenditure of vibration squat. The limitation of our study is the limited sample size. More participants and a greater variety of WBV conditions could allow for more comprehensive calculations. In addition, more experimental benchmarks (i.e. creatine kinase, blood lactate, RPE) may help us obtain a more comprehensive outcome.

Conclusion

WBV squats are moderate-to-vigorous intensity exercise. 30 Hz 2 mm WBV is sufficient for evoking superior oxygen consumption during and after exercise under certain training weight, the response of heart rate to WBV was less pronounced. Increasing training weight could elicit greater oxygen consumption and heart rate under WBV condition.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all subjects who participated in this experiment. This research was funded by a grant from “The Special Fund for Basic Scientific Research Operating Fees of the Central University” [grant number 2013019].

Author contributions

Zhengji QIAO: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing. Feifei LI: writing - review & editing, methodology, formal analysis. Zhengyang YE: methodology, writing - original draft. Yang WANG: conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, project administration. Yanchun LI: writing - review & editing. Longyan YI: writing - review & editing. Bing YAN: writing - review & editing. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jo, N. G. et al. Effectiveness of whole-body vibration training to improve muscle strength and physical performance in older adults: prospective, single-blinded, randomized controlled trial[C]//Healthcare. MDPI9(6), 652 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang, M. et al. Whole-body vibration modulates leg muscle reflex and blood perfusion among people with chronic stroke: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Sci. Rep.10(1), 1473 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim, E. et al. The acute effects of different frequencies of whole-body vibration on arterial stiffness. Clin. Exp. Hypertens.42(4), 345–351 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalaoglu, E. et al. Whole body vibration activates the tonic vibration reflex during voluntary contraction. J. Phys. Therapy Sci.35(6), 408–413 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betik, A. C. et al. Whole-body vibration stimulates microvascular blood flow in skeletal muscle. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.53(2), 375–383 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Araújo, D. L. et al. Electromyographic activation levels of gluteus maximus, hamstrings, and quadriceps in squat and hip thrust exercises: a systematic review. Brazilian J. Health Rev.6(4), 17985–17999 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee, J. H. et al. Differences in the muscle activities of the quadriceps femoris and hamstrings while performing various squat exercises. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabilitation. 14(1), 1–8 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang, J., Jeong, D. & Choi, H. The effects of squat exercises with vertical whole-body vibration on the center of pressure and trunk muscle activity in patients with low back pain. J. Int. Acad. Phys. Therapy Res.11(4), 2253–2260 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lienhard, K. et al. Determination of the optimal parameters maximizing muscle activity of the lower limbs during vertical synchronous whole-body vibration. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.114(7), 1493–1501 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serravite, D. H., Edwards, D., Edwards, E. S., Gallo, S. E. & Signorile, J. F. Loading and concurrent synchronous whole-body vibration interaction increases oxygen consumption during resistance exercise. J. Sports Sci. Med.12(3), 475–480 (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollock, R. D. et al. Muscle activity and acceleration during whole body vibration: Effect of frequency and amplitude. Clin. Biomech. Elsevier Ltd. 25(8), 840–846 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaidell, L. N. et al. Lower body acceleration and muscular responses to Rotational and Vertical Whole-Body vibration at different frequencies and amplitudes. Dose-Response17, 1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ainsworth, B. E. et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc.43(8), 1575–1581 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gojanovic, B. et al. Physiological response to whole-body vibration in athletes and sedentary subjects. Physiol. Res.63, 6 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang, J. et al. Metabolic responses to whole-body vibration: Effect of frequency and amplitude. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.116(9), 1829–1839 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritzmann, R., Gollhofer, A. & Kramer, A. The influence of vibration type, frequency, body position and additional load on the neuromuscular activity during whole body vibration. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.113, 1–11 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marín, P. J., Hazell, T., García-Gutiérrez, M. T. & Cochrane, D. J. Acute unilateral leg vibration exercise improves contralateral neuromuscular performance. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact.14, 58–67 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petit, P. D. et al. Optimal whole-body vibration settings for muscle strength and power enhancement in human knee extensors. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.20, 1186–1195 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertucci, W. M. et al. Effect of whole body vibration in energy expenditure and perceived exertion during intense squat exercise. Acta Bioeng. Biomech.17(1), 87–93 (2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rittweger, J. et al. Oxygen uptake in whole-body vibration exercise: influence of vibration frequency, amplitude, and external load. Int. J. Sports Sci. Med.23(6), 428–432 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang, J. et al. Acute effects of whole-body vibration on energy metabolism during aerobic exercise. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness. 56(7), 834 (2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.González, A. I. et al. Whole-body vibration exercise in the management of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther.36, 20–29 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, K. C. et al. Low-frequency vibration facilitates post-exercise cardiovascular autonomic recovery. J. Sports Sci. Med.20(3), 431 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Betik, A. C. et al. Whole-body vibration stimulates microvascular blood flow in skeletal muscle. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc.53(2), 375–383 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nordlund, M. M. & Thorstensson, A. Strength training effects of whole-body vibration? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 17, 12–17 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giunta, M. et al. Combination of external load and whole body vibration potentiates the gh-releasing effect of squatting in healthy females. Horm. Metab. Res.45(8), 611–616 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giunta, M., Cardinale, M., Agosti, F., Patrizi, A. & Sartorio, A. Growth hormone-releasing effects of whole body vibration alone or combined with squatting plus external load in severely obese female subjects. Obes. Facts. 5(4), 567–574 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martínez-Pardo, E., Romero-Arenas, S. & Alcaraz, P. E. Effects of different amplitudes (high vs. low) of whole-body vibration training in active adults. J. Strength. Conditioning Res.27(7), 1798–1806 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazell, T. J., Jakobi, J. M. & Kenno, K. A. The effects of whole-body vibration on upper- and lower-body EMG during static and dynamic contractions. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab.32(6), 1156–1163 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avelar, N. C. P. et al. Oxygen consumption and heart rate during repeated squatting exercises with or without whole-body vibration in the elderly. J. Strength. Conditioning Res.25(12), 3495–3500 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melo, F. A. T. et al. Whole-body vibration training protocols in obese individuals: a systematic review. Revista Brasileira De Med. do Esporte. 25, 527–533 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marín-Cascales, E. et al. Whole-body vibration training and bone health in postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine97(34), e11918 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Đorđević, D. et al. Whole-body vibration effects on flexibility in artistic Gymnastics—A systematic review. Medicina58(5), 595 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panissa, V. L. G. et al. Magnitude and duration of excess of post-exercise oxygen consumption between high‐intensity interval and moderate‐intensity continuous exercise: a systematic review. Obes. Rev.22(1), e13099 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott, C. B. Quantifying the immediate recovery energy expenditure of resistance training. J. Strength. Conditioning Res.25(4), 1159 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vezina, J. W., Ananian, D., Campbell, C. A., Meckes, K. D., Ainsworth, B. E. & N., & An examination of the differences between two methods of estimating energy expenditure in resistance training activities. J. Strength. Conditioning Res.28(4), 1026–1031 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Heuvelen, Marieke, J. G. et al. Reporting guidelines for whole-body vibration studies in humans, animals and cell cultures: a consensus statement from an international group of experts. Biology10(10), 965 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang, X. et al. Basal energy expenditure in southern Chinese healthy adults: measurement and development of a new equation[J]. Br. J. Nutr.104(12), 1817–1823 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohkawara, K. et al. Twenty-four–hour analysis of elevated energy expenditure after physical activity in a metabolic chamber: models of daily total energy expenditure. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.87(5), 1268–1276 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Popp, C. J. et al. Approximate time to steady-state resting energy expenditure using Indirect Calorimetry in Young, healthy adults. Front. Nutr., 3, 10 Suppl 2 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Hopkins, W., Marshall, S., Batterham, A. & Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc.41(3), 3 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gignac, G. E. & Szodorai, E. T. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Pers. Indiv. Differ.102, 74–78 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.