Abstract

Mice deficient in Klotho gene expression exhibit a syndrome resembling premature human aging. To determine whether variation in the human KLOTHO locus contributes to survival, we applied two newly characterized polymorphic microsatellite markers flanking the gene in a population-based association study. In a cohort chosen for its homogeneity, Bohemian Czechs, we demonstrated significant differences in selected marker allele frequencies between newborn and elderly individuals (P < 0.05). These results precipitated a search for functional variants of klotho. We identified an allele, termed KL-VS, containing six sequence variants in complete linkage disequilibrium, two of which result in amino acid substitutions F352V and C370S. Homozygous elderly individuals were underrepresented in three distinct populations: Bohemian Czechs, Baltimore Caucasians, and Baltimore African-Americans [combined odds ratio (OR) = 2.59, P < 0.0023]. In a transient transfection assay, secreted levels of klotho harboring V352 are reduced 6-fold, whereas extracellular levels of the S370 form are increased 2.9-fold. The V352/S370 double mutant exhibits an intermediate phenotype (1.6-fold increase), providing a rare example of intragenic complementation in cis by human single nucleotide polymorphisms. The remarkable conservation of F352 among homologous proteins suggests that it is functionally important. The corresponding substitution, F289V, in the closest human klotho paralog with a known substrate, cBGL1, completely eliminates its ability to cleave p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucoside. These results suggest that the KL-VS allele influences the trafficking and catalytic activity of klotho, and that variation in klotho function contributes to heterogeneity in the onset and severity of human age-related phenotypes.

Mice homozygous for severely hypomorphic alleles of the Klotho gene (klotho mice) exhibit a syndrome resembling human aging, including atherosclerosis, osteoporosis, emphysema, and infertility (1). Based on both macroscopic and histological appearance, klotho mice are developmentally normal until 3–4 weeks of age. Thereafter, they exhibit growth retardation, gradually become inactive, and die prematurely at ≈8–9 weeks of age (1).

The klotho gene encodes a putative type I membrane protein, which consists of an N-terminal signal sequence, an extracellular domain with two internal repeats (KL1 and KL2), a single transmembrane domain, and a short intracellular domain (1). The two internal repeats share homology with members of the family 1 glycosidases and exhibit 20–40% sequence identity to β-glucosidases from bacteria and plants as well as mammalian lactase glycosylceramidase (1, 2).

Analysis of cDNA revealed that the klotho gene also expresses a secreted form, lacking KL2, transmembrane, and intracellular domains, due to alternative RNA splicing. Thus, klotho may also act as a humoral factor (1, 3). Further evidence for this hypothesis includes the observation that klotho mRNA expression was not detectable in many organs in which severe changes occur in klotho mice (1). Similarly, transgenic expression of klotho limited to brain and testis was sufficient to rescue all macroscopic features observed in klotho mice (1).

The mechanism of klotho function remains unclear. Recent experiments have shown that endothelium-dependent vasodilation of the aorta and arterioles was impaired in heterozygous klotho mice, but could be restored by parabiosis with wild-type mice (4). In addition, nitric oxide metabolites (NO2 and NO3) in urine are significantly lower in heterozygous klotho mice (4). These results suggest that klotho protein may protect the cardiovascular system through endothelium-derived NO production (4). Remarkably, in vivo klotho gene delivery can ameliorate vascular endothelial dysfunction, increase nitric oxide production, reduce elevated blood pressure, and prevent medial hypertrophy and perivascular fibrosis in a rat model with multiple atherogenic risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and hyperlipidemia (5).

Human klotho shows 86% amino acid identity with the mouse protein, and is encoded by a gene that spans over 50 kb on chromosome 13q12 (3). To date, no premature-aging syndromes have been linked to this region. Like the mouse Klotho gene, human KLOTHO encodes both membrane-bound and secreted forms; however, in humans the secreted form predominates (3, 6). Expression of KLOTHO mRNA occurs primarily in the placenta, kidney, prostate, and small intestine (3, 6).

To determine whether the KLOTHO gene is involved in human aging, we used a population-based association study employing two newly characterized flanking microsatellite markers. Marker 1 is ≈11 kb 3′ of the last exon, and Marker 2 is ≈66 kb 5′ of the first exon. We present evidence that the KLOTHO locus is associated with human survival, defined as postnatal life expectancy, and longevity, defined as life expectancy after 75. We also identify and functionally characterize a variant of klotho that is associated with a decrease in survival when in homozygosity, in three independent populations: Bohemian Czech, Baltimore Caucasian, and Baltimore African-American.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects.

The Bohemian Czech subjects represent an expanded cohort from a study previously described (7). Elderly Baltimore African-American and Caucasian subjects were derived from the Women's Health and Aging Study (8, 9), and newborn controls derived from the Baltimore–Washington Infant Study (10). Each of these studies used Institutional Research Board-approved methods of informed consent and each participant was entirely anonymous during the present study.

Plasmid Construction.

The human KLOTHO expression vector (pSecKlwt-V5) was constructed by amplifying a 1,684-bp fragment from Human Placenta Marathon Ready cDNA (CLONTECH) with primers E1-cDNA and SecNoStop, by using the Advantage-GC cDNA PCR Kit (CLONTECH). The PCR product was cloned into pcDNA3.1/V5/His-TOPO (Invitrogen) and verified by direct sequencing. The substitutions F352V and C370S were introduced with the QuickChange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene).

The human cytosolic β-glucosidase (cBGL1) expression vector (pCBGDF) was constructed by amplifying a 1,474-bp fragment from Human Liver Quick Clone cDNA (CLONTECH) with primers Glu5′ and Glu3′, using Pfu turbo polymerase (Stratagene). The PCR product was cloned into the N-terminal GST-fusion expression vector pDEST15 by using the GATEWAY cloning system (GIBCO/BRL), and verified by direct sequencing. The substitutions F289V and Q307S were introduced as described above. All primer sequences are available on request.

DNA Isolation.

DNA was isolated using the MasterPure DNA Purification Kit (Epicentre) as described (11).

Marker Genotyping.

Multiple dinucleotide repeat sequences were identified by visual inspection of the genomic sequence for KLOTHO and flanking regions (GenBank accession nos. Z92540 and Z92541). Marker 1 (sense, 5′-CATACGCAGACCCAGAGCC; antisense, 5′-GCTTCTCATTACGAAAGTACAGCTGGG, italic sequence is a tail to force reaction to completion) is 11 kb 3′ of exon 5, and Marker 2 (sense, 5′-CTTACCAGCATGTGAGCTATC; antisense, 5′-TTTTACAGGTGATCTGAGACTC) is 66 kb 5′ of exon 1. Size fractionation of PCR products derived from multiple unrelated individuals was used to demonstrate polymorphic variation (data not shown). Markers were amplified using AmpliTaq Gold (Perkin–Elmer). Sense primers were fluorescently labeled, and product size was determined using a Perkin–Elmer (Abd) 373a DNA sequencer.

Mutation Screening.

Exons 1–5 were analyzed by single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis as described (12), using 1× TME (500 mM Tris/350 mM MES/10 mM EDTA) buffer, pH 6.8, at room temperature. Exon 1 PCRs were performed using the Advantage-GC Genomic PCR kit (CLONTECH). Exons 2–5 were amplified using AmpliTaq Gold (Perkin–Elmer). Primer sequences are available on request.

Tissue Culture, Transfections, and Western Analysis.

HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and an antibiotic–antimycotic mixture (GIBCO/BRL). Transfections were carried out with TransIT-HeLaMonster (Panvera, Madison, WI), using 10 μg of plasmid per 10-cm-diameter dish. Twenty-four hours post transfection, the cell culture media was replaced with fresh DMEM supplemented with antibiotic–antimycotic mixture. Forty-eight hours post transfection, the cell culture media was collected and cells were removed by pelleting before concentration in a Vivaspin 20 concentrator (Vivascience, Gloucestershire, U.K.). Sample volume was brought up to 450 μl with 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5)/50 mM NaCl. After adding 150 μl of NuPage LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and 100 μl of 1 M DTT, samples were heated to 70°C for 10 min and centrifuged briefly. Cell extracts were also prepared 48 h after transfection. Following a brief wash with PBS, cells were lysed in 2× SDS sample buffer (13), collected by scraping, and samples were boiled for 5 min and centrifuged briefly. Samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE [NuPage 7% Tris-Acetate (Invitrogen)] and transferred to nitrocellulose.

Immunoblotting with anti-V5 (Invitrogen) and anti-neomycin phosphotransferase II (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) were carried out as specified by the manufacturers.

Protein Purification and Enzyme Assay.

Total protein was isolated from logarithmically growing E. coli strain BL21-SI (GIBCO/BRL) harboring the GST-tagged wild-type or mutant cBGL1 expression constructs. Following salt induction according to the manufacturer's protocol, 100 ml of bacterial culture was pelletted and resuspended in 10 ml PBS supplemented with 1 Complete Mini protease inhibitor mixture tablet (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), and 10 μl 1 M DTT. Cells were disrupted by sonication and further solubilized by the addition of 500 μl of 20% Triton X-100 and gentle mixing for 30 min at 4°C. Samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the GST-tagged protein was purified from the supernatant with a HiTrap affinity column (Amersham Pharmacia). Elution fractions of 1 ml were collected. Purification was monitored by SDS/PAGE [NuPage 4–12% Bis-Tris (Invitrogen)] followed by visualization with Bio-Safe Coomassie (Bio-Rad). β-Glucosidase enzyme assays were performed as described (14).

Statistics.

Individual allele distributions were analyzed using the GAS package Version 2.3 (http://users.ox.ac.uk/∼ayoung), and overall marker comparisons were made using the CLUMP program (15), which employs a Monte Carlo-based method for determining P. Individual genotype distributions were analyzed using Pearson's χ2 test (http://home.clara.net/sisa/binomial.htm) and the CLUMP program was used to determine overall significance. Survival advantage or disadvantage was calculated as an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) (http://home.clara.net/sisa/binomial.htm). Mantel–Haenszel log rank analysis with 1-sided P of Kaplan–Meier survival curves was performed using PRISM, Version 3.0 for Windows (GraphPad, San Diego). The combined population analysis was calculated using the Mantel–Haenszel estimate of joint OR and significance (16).

Results

The initial cohort was comprised of 435 elderly individuals (≥75 years), and 611 contemporary newborns, both drawn at random from the Bohemian Czech population. This group is well suited for an association study because it represents Central European populations without extensive non-European immigration during the past millennium. Both the World Wars of last century did not cause disproportionate changes in population sex ratios (7). The elderly are considered to be “escapees” of strong selective pressure that existed before the introduction of modern health care in the early 1900s (childhood mortality > 20%). The majority were stratified into the “SENIEUR –Apparently Healthy” (141 subjects) and “SENIEUR –Inpatient” (291 subjects) categories of the EURAGE “SENIEUR protocol” (7, 17).

Marker 1 allele frequencies were significantly different (P < 0.04) between newborn and elderly individuals (Table 1). This difference was largely attributable to allele 17, which was more prevalent in newborns (P < 0.0002). These data indicate a detrimental role for this allele in survival, with a 2.19-fold (95% CI 1.45–3.31) increase in the risk of death before age 75. This difference is still highly significant (P < 0.0031) after applying a Bonferroni correction for the number of alleles tested, and did not depend on the sex or health of the individuals (data not shown). The distribution of Marker 2 alleles did not differ significantly between the groups (P > 0.25). These marker data strongly suggest a role for KLOTHO in human survival and precipitated a search for functional variants.

Table 1.

KLOTHO allele distribution in newborn and elderly individuals

| Allele | Newborn, n | Elderly, n | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker 1 | ||||

| 5 | 274 | 196 | 0.14 | 0.71 |

| 7 | 396 | 295 | 0.03 | 0.87 |

| 8 | 13 | 12 | 0.32 | 0.57 |

| 12 | 20 | 17 | 0.19 | 0.66 |

| 13 | 29 | 16 | 0.89 | 0.34 |

| 14 | 36 | 31 | 0.42 | 0.52 |

| 15 | 162 | 137 | 1.60 | 0.20 |

| 16 | 78 | 62 | 0.21 | 0.65 |

| 17 | 91 | 32 | 14.0 | 0.00014 |

| 18 | 21 | 21 | 1.00 | 0.32 |

| 19 | 8 | 10 | 1.30 | 0.26 |

| Totals | 1,153 | 850 | ||

| Overall comparison | 19.3 | P < 0.04 | ||

| Marker 2 | ||||

| 1 | 54 | 29 | 1.50 | 0.23 |

| 2 | 12 | 12 | 0.76 | 0.38 |

| 5 | 15 | 8 | 0.41 | 0.52 |

| 6 | 71 | 34 | 3.60 | 0.06 |

| 7 | 542 | 369 | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| 8 | 285 | 217 | 1.00 | 0.32 |

| 9 | 56 | 55 | 3.30 | 0.07 |

| 10 | 42 | 37 | 1.00 | 0.31 |

| 11 | 44 | 33 | 0.08 | 0.78 |

| 12 | 65 | 41 | 0.32 | 0.57 |

| Totals | 1,196 | 842 | ||

| Overall comparison | 11.5 | P > 0.25 |

Bold type indicates significant χ2 values (P < 0.05). Alleles with frequencies less than 1% in both newborn and elderly groups were not included for analysis, but were included to derive the total n.

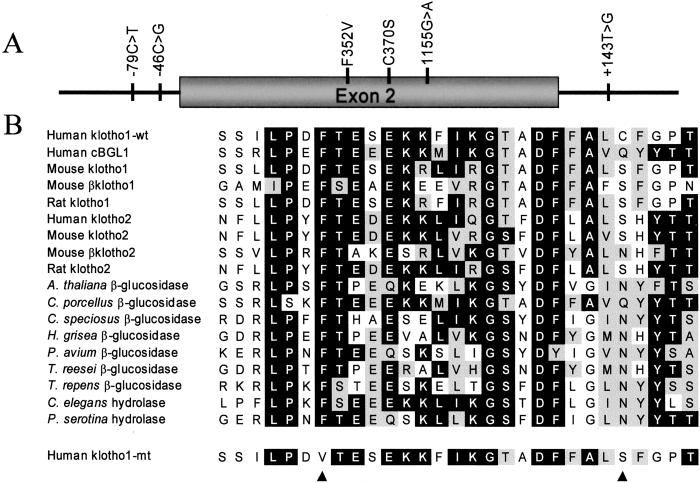

We used SSCP analysis and DNA sequencing to screen for mutations in KLOTHO that could influence human aging and identified an allele, termed KL-VS, that was defined by the presence of six single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that occur within an 800-bp region spanning exon 2 and flanking sequence (Fig. 1A). Allele-specific oligonucleotide hybridization (ASO) analysis was used to demonstrate complete linkage disequilibrium for the coding region mutations (data not shown). Of the three mutations in exon 2, two code for amino acid changes and one is silent. The change at amino acid position 352 was a phenylalanine to valine substitution. Phenylalanine at this position is likely to be important to klotho function, as it is remarkably conserved in homologous proteins in eukaryotic organisms (Fig. 1B). The change at amino acid position 370 was a cysteine to serine substitution. Cysteine at this position is only seen in the first family I glycosidase domain of human klotho.

Figure 1.

Sequence variation in the KLOTHO locus. (A) Schematic of mutations detected in KLOTHO. (B) Amino acid sequence of klotho amino acid positions 346–374 and homologous proteins. Klotho has two homologous domains, here labeled “Klotho1” and “Klotho2.” The common allele of klotho is labeled “Klotho1-wt” and the rare allele is labeled “Klotho1-mt.” Alignment was performed using the CLUSTALW program (MACVECTOR 6.5.1). Amino acids found in at least 9 of 16 positions are shaded in black. Conservation of amino acid character in at least 9 of 16 positions is indicated by gray shading. The black arrow heads indicate amino acid positions at which mutations in klotho have been detected.

The creation of a Mae III restriction site by the F352V mutation allowed for efficient genotyping of large populations. The genotype distribution was different between newborn and elderly Bohemian Czech individuals (P < 0.03), with heterozygosity for these mutations more prevalent in the elderly (P < 0.04) and a trend suggesting that homozygosity is more prevalent in newborns (P ≤ 0.08; Table 2). These data indicate a survival advantage for heterozygosity, with a 1.43-fold (95% CI 1.02–2.01) increased survival rate to age 75, and suggest a 2.70-fold (95% CI 0.84–8.69) survival disadvantage for homozygosity of this allele. No significant differences were seen when the population was stratified by sex or health status (data not shown). The KL-VS allele is found on multiple marker allele haplotypes and is negatively associated with Marker 1 Allele 17 (P < 0.04), indicating that there are additional deleterious mutations in KLOTHO that have yet to be identified.

Table 2.

KLOTHO genotypes in newborn and elderly individuals

| Genotype at codon 352 | Newborn, n (frequency, %) | Elderly, n (frequency, %) | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bohemian Czech | ||||

| FF | 307 (78.7) | 308 (74.2) | 2.26 | 0.13 |

| FV | 73 (18.7) | 103 (24.8) | 4.38 | 0.036 |

| VV | 10 (2.6) | 4 (1.0) | 3.01 | 0.08 |

| Total | 390 | 415 | ||

| Baltimore Caucasian | ||||

| FF | 309 (73.6) | 530 (73.3) | 0.01 | 0.92 |

| FV | 100 (23.8) | 185 (25.6) | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| VV | 11 (2.6) | 8 (1.1) | 3.72 | 0.05 |

| Total | 420 | 723 | ||

| Baltimore African- American | ||||

| FF | 156 (69.0) | 169 (69.8) | 0.04 | 0.85 |

| FV | 58 (25.7) | 68 (28.1) | 0.35 | 0.55 |

| VV | 12 (5.3) | 5 (2.1) | 3.60 | 0.06 |

| Total | 226 | 242 | ||

| Combined analysis* | ||||

| VV | 9.31 | 0.0023 |

The common allele is denoted as F and the rare allele, defined by six mutations in complete linkage disequilibrium, is denoted as V.

P is the probability that the joint odds ratio for the 3 populations is not greater than 1.

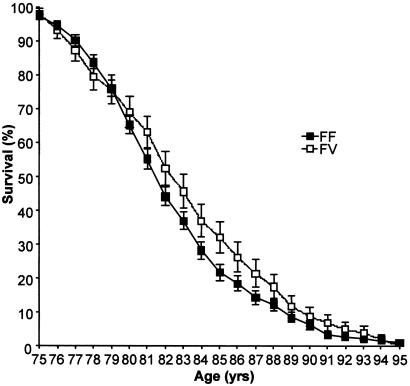

To determine whether the heterozygote advantage associated with the KL-VS allele was specific to survival or also promoted longevity, we generated Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the Czech elderly population stratified by genotype (Fig. 2). A positive effect on lifespan was seen in individuals over 80 years old who were heterozygous for the KL-VS allele (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for Czech elderly stratified by genotype. Error bars depict standard error. Individuals homozygous for V352 were too few to generate a survival curve.

We analyzed two additional populations for the presence of the KL-VS allele. The cohorts used consisted of 965 elderly individuals (≥65 years) collected for the Baltimore Women's Health and Aging Study (WHAS) (8, 9) and 646 control infants collected for the Baltimore Washington Infant Study (BWIS) (10) stratified by race (Caucasian and African-American). ASO analysis was performed on at least 120 individuals from each race (60 infant, 60 elderly), and again demonstrated complete linkage disequilibrium for all of the coding region mutations in the allelic variant marked by the presence of V352 (data not shown). Whereas the heterozygous advantage was not observed, the frequency of elderly individuals homozygous for the KL-VS allele was decreased relative to that observed in infants in both the Caucasian (P ≤ 0.05), and African-American populations (P ≤ 0.06; Table 2). Thus, a homozygous disadvantage for survival was observed in three distinct populations. Use of the Mantel–Haenszel (16) estimate of joint odds ratio and significance demonstrates a 2.59-fold survival disadvantage for individuals homozygous for the KL-VS allele, independent of race (P < 0.0023).

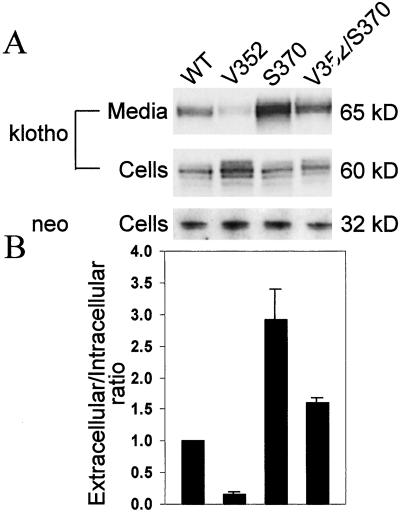

Oligomerization of family I glycosidases is a common characteristic (2), and can often be a prerequisite for secretion from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (18, 19). We tested whether the F352V mutation alters extracellular levels of klotho. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with an expression construct encoding either wild-type or mutant klotho (secreted form) fused to a V5 tag. To control for transfection efficiency, the levels of klotho were expressed as a ratio of extracellular to intracellular protein. These ratios were then normalized to wild type. Extracellular steady-state levels of klotho harboring V352 are reduced greater than 6-fold (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, extracellular levels of klotho harboring S370 are increased 2.9-fold, and the double mutant V352/S370 displays an intermediate phenotype, with a 1.6-fold increase in extracellular klotho levels, demonstrating intragenic complementation in cis (Fig. 3). These results have been replicated in transiently transfected fibroblasts (data not shown). Intracellular levels of klotho harboring V352 alone are increased 1.56 ± 0.20-fold, suggesting a defect in klotho secretion rather than stability (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Extracellular and intracellular levels of klotho from transiently transfected HeLa cells. (A) Western blot probed with anti-V5 or anti-NPTII antibody. Extracellular klotho is glycosylated, resulting in a 5-kDa increase in molecular mass (data not shown). (B) Bar graph depicting the extracellular to intracellular ratio of klotho protein normalized to wild-type from at least three independent assays. Error bars represent 1 SD. All ratios are significantly different from each other and wild-type (P < 0.05).

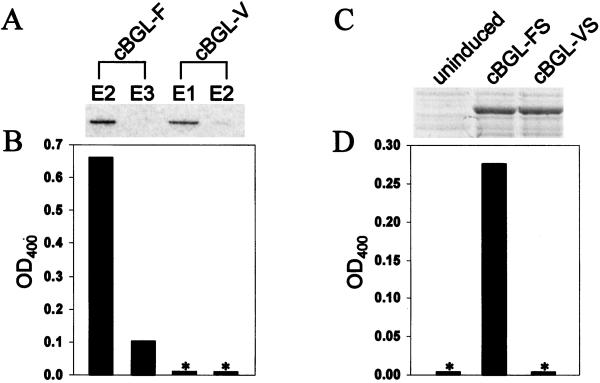

Because of the absence of a known klotho substrate, the biochemical consequences of the F352V and C370S amino acid substitutions could not be determined directly. We therefore performed enzymatic assays on the closest klotho paralog for which there is a known substrate, human cytosolic β-glucosidase (cBGL1) (20, 21). As in most eukaryotic klotho homologues identified, phenylalanine is found at the position corresponding to klotho amino acid 352 (amino acid 289); however, neither cysteine nor serine is found at the position corresponding to klotho amino acid 370 (amino acid 307; Fig. 1B). When valine was substituted for phenylalanine at amino acid position 289, cBGL1 demonstrated a complete loss of ability to cleave p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucoside (Fig. 4 A and B). The introduction of serine at amino acid position 307 was unable to restore activity (Fig. 4 C and D).

Figure 4.

Enzymatic activity of wild-type and F289V substituted human cytosolic β-glucosidase (cBGL1). (A) Coomassie-stained gel demonstrating protein purification of cBGL1-GST fusions in elution fractions E2 + E3 (cBGL1-F) and E1 + E2 (cBGL1-V). No other proteins were visualized in these lanes (data not shown). (B and D) Bar graphs depicting enzymatic activity against p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucoside. (C) Coomassie-stained gel demonstrating protein expression of cBGL1-FS and cBGL1-VS. *, No measurable enzymatic activity.

Discussion

Disruption of the mouse klotho gene results in a syndrome resembling human aging, with phenotypes including atherosclerosis, emphysema, osteoporosis, and infertility (1). We therefore decided to explore the role of KLOTHO in human aging by using a population-based association study. We identified an allele of KLOTHO, termed KL-VS, defined by the presence of six SNPs in complete linkage disequilibrium. A homozygous disadvantage for KL-VS carriers was seen in three geographically and/or ethnically distinct populations (P < 0.0023). Interestingly, a heterozygote advantage was seen in the Bohemian Czech population (P < 0.04), but not in either of the Baltimore populations. Multiple examples of heterozygote advantage in conjunction with homozygote disadvantage exist, including both CFTR allele ΔF508 (22) and hemoglobin S (23). The heterozygote advantage displayed by these alleles is associated with specific environmental pressures, cholera and malaria, respectively. It is therefore plausible that the apparent lack of heterozygote advantage in the two Baltimore groups may manifest the absence of an environmental pressure that was specific to the Bohemian Czech population. A homozygote disadvantage can generally be observed independent of environmental factors.

One aging theory, antagonistic pleiotropy, proposes that individuals with alleles that are beneficial to survival through reproductive age could be selected for by evolution even if the same alleles had negative effects at later ages (24). To test whether the KL-VS allele of KLOTHO followed this model, we generated Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the Czech elderly and demonstrated that heterozygosity for KL-VS contributed to improved longevity, defined as life expectancy after age 75, and not just survival (P < 0.05 for individuals ≥80 years).

Although cryptic population stratification has the potential to confound the interpretation of association studies, it is unlikely to be a significant factor in the study described here. First, the same survival disadvantage for homozygosity of the KL-VS allele was observed in three distinct populations [odds ratio (OR) = 2.70, 2.40, 2.66]. Second, large differences in allele frequencies were not observed between ethnically and/or geographically diverse populations for a given age group. For example, the KL-VS genotype frequencies were not significantly different for Baltimore Caucasian and Czech infants (P > 0.20) or for Baltimore Caucasian and Czech elderly (P > 0.93). Yet the difference in allele frequencies between the combined Caucasian (Baltimore and Czech) infants and combined Caucasian elderly was significant (P < 0.006). Third, if one considers the overall similarities within an age group, the differences between age groups that we observe would require truly massive migrations to have occurred within one generation.

Dimerization is a common characteristic of family 1 glycosidases (2) and, for many integral membrane proteins, is essential for export out of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (18, 19). Indeed, extracellular levels of klotho protein harboring V352 are reduced 6-fold. It remains to be determined whether this mutation influences klotho dimerization or interaction with other proteins that may be required for klotho export, such as ER chaperones.

Surprisingly, extracellular levels of klotho harboring S370 are increased 2.9-fold. This substitution has the ability to complement the V352 phenotype in cis, as demonstrated by the V352/S370 double mutant which exhibits an intermediate phenotype (1.6-fold increase). In screening a total of over 300 individuals taken from the geographically and/or ethnically distinct cohorts used in this study, we have not found any individuals who harbor only V352 or S370. Although individuals harboring either of these mutations alone may exist at a low frequency in the population, it is also possible that neither genotype is viable. This hypothesis requires that secretion is essential to klotho function. In this scenario the V352 phenotype would correspond to that of a severe hypomorph, similar to the klotho mouse, and would be negatively selected. Likewise, if the homozygous disadvantage exhibited by KL-VS allele-containing individuals is due, at least in part, to increased extracellular klotho levels, individuals harboring only S370 would experience an even greater negative selection. Because the mutation identified at C370 results in a serine residue, which is present in this position in mice (1) and rats (25), it is possible that this substitution contributes to species-specific differences in age-related phenotypes. Additional examples exist, including α-synuclein, in which protein coding changes that result in amino acids present in other organisms can lead to phenotypic variation in humans, including disease (26).

The remarkable evolutionary conservation of the F352 amino acid among homologous proteins suggests that it is likely to be important to klotho function. Indeed, the substitution of valine for phenylalanine at the corresponding residue in the closest human klotho paralog with a known substrate, cBGL1, completely eliminates the ability to cleave p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucoside. The introduction of serine at the position corresponding to klotho aa 370 failed to restore enzymatic activity. These results suggest that the KL-VS allele may exhibit both altered secretion and a loss of catalytic activity. Whereas both KL1 and KL2 lack one of two conserved glutamate residues found in active centers of many glycosidases (2, 27), it has been proposed that other residues, perhaps N239 and S872 in human klotho, may serve as proton donor and nucleophile, respectively, or support alternative hydrolysis pathways. Interestingly, a novel mouse protein termed βklotho also lacks the corresponding glutamates, perhaps defining a distinct subset within the family 1 glycosidase superfamily (28). Thus, homozygotes for the KL-VS allele could have a severe deficiency of extracellular klotho function despite increased secretion of the protein. This scenario would recapitulate the situation in the hypomorphic mouse model of premature aging. Clearly, more details regarding klotho biology are needed to derive the precise pathogenetic mechanism.

Multiple models of aging invoke accelerated or excessive posttranslational modification of proteins including glycation. Resultant advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) elicit a wide range of responses that have been proposed to contribute to many age related phenotypes, including atherosclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, diabetic complications, and microvascular changes (29). It is possible that the proposed glycosidase activity of klotho retards the accumulation of AGEs. Alternatively, klotho may contribute to or regulate signaling cascades with downstream targets that influence aging. Based on observations in klotho-deficient mice, these targets may include factors involved in NO production and maintenance of proper endothelial function (4, 5). These hypotheses remain to be tested in humans or mouse models of normal or accelerated aging.

Acknowledgments

We thank Charlotte Ferencz for access to epidemiologic data from the Baltimore–Washington Infant Study (supported by NHLBI R37-HL25629) and Christopher Loffredo for access to samples. We thank Aravinda Chakravarti for useful suggestions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AR21135 (to H.C.D.) and AR44702 (to I.M.); Grants IGA MZCR (6497-3, 6411-3, 6462-3, 6250-3, 6464-3, 00000064203) and MSMT CR (ME457, LN00AO79, 111300003) from the Czech Republic (to M.M., Jr., A.K., and M.M., Sr.); and U.S. Department of Energy Contract No. DE-AC03-76SF00098 (to I.S.M.). The Women's Health and Aging Study is supported by NOI-AG-1-2112 (to L.F.). H.C.D. is an investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, Ohyama Y, Kurabayashi M, Kaname T, Kume E, et al. Nature (London) 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mian I S. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 1998;24:83–100. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1998.9998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Shiraki-Iida T, Nagai R, Kuro-o M, Nabeshima Y. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:626–630. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagai R, Saito Y, Ohyama Y, Aizawa H, Suga T, Nakamura T, Kurabayashi M, Kuroo M. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:738–746. doi: 10.1007/s000180050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito Y, Nakamura T, Ohyama Y, Suzuki T, Iida A, Shiraki-Iida T, Kuro-o M, Nabeshima Y, Kurabayashi M, Nagai R. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:767–772. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiraki-Iida T, Aizawa H, Matsumura Y, Sekine S, Iida A, Anazawa H, Nagai R, Kuro-o M, Nabeshima Y. FEBS Lett. 1998;424:6–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macek M, Jr, Macek M, Sr, Krebsova A, Nash E, Hamosh A, Reis A, Varon-Mateeva R, Schmidtke J, Maestri N E, Sperling K, Krawczak M, Cutting G R. Hum Genet. 1997;99:565–572. doi: 10.1007/s004390050407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guralnik, J. M., Fried, L. P., Simonsick, E. M., Kasper, J. D. & Lafferty, M. E. (1995) National Institute of Aging, National Institutes of Health Pub. No. 95-4009.

- 9.Fried L P, Bandeen-Roche K, Chaves P H, Johnson B A. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M43–M52. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.1.m43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferencz C, Rubin J D, Loffredo C A, Magee C A. Perspectives in Pediatric Cardiology. Epidemiology of Congenital Heart Disease: The Baltimore–Washington Infant Study, 1981–1989. Mt. Kisko, NY: Futura Publishing; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iovannisici D M. Epicentre Forum. 2000;7:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi K, Kukita Y, Inazuka M, Tahira K. In: Mutation Detection: A Practical Approach. Cotton R G H, Edkins E, Forrest S, editors. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1998. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Springs Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gopalan V, Pastuszyn A, Galey W R, Jr, Glew R H. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14027–14032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sham P C, Curtis D. Ann Hum Genet. 1995;59:97–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1995.tb01608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantel N, Haenszel W. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ligthart G J, Corberand J X, Geertzen H G, Meinders A E, Knook D L, Hijmans W. Mech Ageing Dev. 1990;55:89–105. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(90)90108-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurtley S M, Helenius A. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1989;5:277–307. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.05.110189.001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelham H R. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1989;5:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.05.110189.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yahata K, Mori K, Arai H, Koide S, Ogawa Y, Mukoyama M, Sugawara A, Ozaki S, Tanaka I, Nabeshima Y, Nakao K. J Mol Med. 2000;78:389–394. doi: 10.1007/s001090000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Graaf M, Van Veen I C, Van Der Meulen-Muileman I H, Gerritsen W R, Pinedo H M, Haisma H J. Biochem J. 2001;356:907–910. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroeder S A, Gaughan D M, Swift M. Nat Med. 1995;1:703–705. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth E F, Jr, Friedman M, Ueda Y, Tellez I, Trager W, Nagel R L. Science. 1978;202:650–652. doi: 10.1126/science.360396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams G C. Evolution (Lawrence, Kans) 1957;11:398–411. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohyama Y, Kurabayashi M, Masuda H, Nakamura T, Aihara Y, Kaname T, Suga T, Arai M, Aizawa H, Matsumura Y, et al. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:920–925. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polymeropoulos M H, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide S E, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, et al. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies G, Henrissat B. Structure. 1995;3:853–859. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito S, Kinoshita S, Shiraishi N, Nakagawa S, Sekine S, Fujimori T, Nabeshima Y I. Mech Dev. 2000;98:115–119. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00439-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bierhaus A, Hofmann M A, Ziegler R, Nawroth P P. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37:586–600. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]