Abstract

Introduction:

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is known to elevate cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, but the extent to which obesity and IIH-specific factors contribute to this risk is not well understood. WE aim to separate the effects of obesity from IIH-specific factors on the risk of stroke and CVD, building on previous findings that indicate a two-fold increase in cardiovascular events in women with IIH compared to BMI-matched controls.

Methods:

An obesity-adjusted risk analysis was conducted using Indirect Standardization based on data from a cohort study by Adderley et al., which included 2,760 women with IIH and 27,125 matched healthy controls from The Health Improvement Network (THIN). Advanced statistical models were employed to adjust for confounding effects of obesity and determine the risk contributions of IIH to ischemic stroke and CVD, independent of obesity. Four distinct models explored the interactions between IIH, obesity, and CVD risk.

Results:

The analysis showed that IIH independently contributes to increased cardiovascular risk beyond obesity alone. Risk ratios for cardiovascular outcomes were significantly higher in IIH patients compared to controls within similar obesity categories. Notably, a synergistic effect was observed in obese IIH patients, with a composite CVD risk ratio of 6.19 (95% CI: 4.58–8.36, p<0.001) compared to non-obese controls.

Conclusions:

This study underscores a significant, independent cardiovascular risk from IIH beyond obesity. The findings advocate for a shift in managing IIH to include comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment and mitigation. Further research is required to understand the mechanisms and develop specific interventions for this group.

Keywords: Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension, Pseudotumor Cerebri, Stroke, Ischemic Stroke, Cardiovascular Disease

1. Introduction

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a condition characterized by elevated intracranial pressure of unknown etiology, typically manifesting as papilledema with associated risks of visual loss and chronic disabling headache [1]. The incidence and economic burden of IIH are rising in parallel with global obesity trends [2]. While obesity is a well-established risk factor for IIH, with over 90% of patients being obese [3], the relationship between IIH and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk remains poorly understood.

In the United States, studies indicate an incidence increase from 1.6 to 2.4 per 100,000 person-years in the general population, rising dramatically to 15–19 per 100,000 in women of childbearing age [4]. This rising disease burden encompasses both economic impacts, with annual costs exceeding millions of dollars in the US [5], and significant quality of life deterioration, including chronic pain, vision problems, and psychological distress [6].

Adderley et al. conducted a retrospective case-control population-based matched controlled cohort study using 28 years of data from The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database in the United Kingdom, THIN database is a longitudinal primary care database containing anonymized electronic health records from over 17 million patients in the United Kingdom, provides researchers with comprehensive clinical data for epidemiological studies and healthcare research. [7]. Their study suggested that women with IIH have a two-fold increased risk of cardiovascular events compared to BMI-matched controls. However, the mechanisms underlying this elevated risk and the relative contributions of obesity versus IIH-specific factors remained unclear.

The relationship between IIH and CVD risk involves multiple pathophysiological mechanisms beyond adiposity alone. Neuroendocrine dysfunction in IIH is characterized by elevated endogenous testosterone and androstenedione levels [8], distinct from exogenous supplementation or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). This hormonal dysregulation may affect both cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) dynamics and cardiovascular function [9]. Additionally, the current literature studies demonstrate elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in IIH patients, potentially contributing to both intracranial pressure elevation and vascular dysfunction [9]. IIH patients exhibit distinct metabolic profiles, including altered glucose homeostasis and lipid metabolism, which may independently contribute to cardiovascular risk [9, 10]. Several additional risk factors may contribute to both IIH and CVD, including hormonal contraceptive use, vitamin A metabolism, sleep apnea, and chronic kidney disease [10–12].

Building upon Adderley et al.’s [7] findings, our study aims to disentangle the effects of obesity and IIH on stroke risk specifically. Obesity is a known independent risk factor for stroke, with an average hazard ratio (HR) of 2.29 reported in large-scale evidence [13]. By adjusting for this obesity-related risk, we seek to isolate the potential contribution of IIH itself to stroke incidence.

Our study employs an established methodological approach adapted from epidemiological research in obesity [14, 15] to simulate predicted ischemic stroke and CVD events in both IIH and control groups under normative weight conditions. This approach has been previously used in obesity literature [16, 17].

Understanding the relationship between IIH and their associated risks, independent of obesity, has important clinical implications. If IIH itself confers additional cardiovascular risk, it may warrant more aggressive management of modifiable risk factors and earlier implementation of preventive strategies in this patient population. Furthermore, elucidating the mechanisms underlying this potential association could reveal new therapeutic targets for reducing cardiovascular morbidity in IIH. Our study aims to build upon the foundational work of Adderley et al. [7] to further investigate the complex interplay between IIH, obesity, and the associated risks. By employing innovative statistical methods to adjust for the confounding effects of obesity, we aim to provide crucial insights into the cardiovascular implications of IIH and inform evidence-based management strategies for this increasingly prevalent condition.

2. Methods

Building upon the foundational work of Adderley et al. [7], we conducted a retrospective analysis using data from their paper which was originally obtained through THIN, a large UK primary care database. Our study focused on women with IIH and matched controls, aiming to elucidate the independent effect of IIH on stroke and cardiovascular risks, distinct from the influence of obesity. Patients were excluded from the Adderley et al. [7], study if they had different diagnostic or clinical codes for conditions that could mimic IIH, specifically hydrocephalus or cerebral venous thrombosis, or any other cause of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP).

Additionally, in the baseline cohort selection, female patients were excluded if they did not have at least one-year of registration with an eligible general practice before cohort entry, to ensure adequate documentation of baseline covariates. For the analysis of individual CVD outcomes, patients with a record of the specific outcome of interest at baseline were excluded from the corresponding analysis, for composite CVD analysis, patients with any CVD at baseline were excluded; for type 2 diabetes analysis, patients with either type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes at baseline were excluded. For sensitivity analyses, additional exclusions were applied, including excluding women diagnosed with IIH after age 60 years, since IIH is rare among older adults and there may be potential misclassification errors in this age group.

2.1. Study Population and Data Source:

We utilized the cohort established by Adderley et al. [7], comprising 2,760 women with IIH and 27,125 matched controls. Participants were identified from THIN database records spanning January 1, 1990, to January 17, 2018. Controls were matched to IIH patients based on age, body mass index (BMI), and sex, with up to 10 controls per IIH case.

2.2. Outcome Measures:

Our primary outcome of interest was the incidence of composite CVD, heart failure, ischemic heart disease (IHD), ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. We extracted the relevant data from the corresponding paper, following the coding and identification methods described by Adderley et al [7].

2.3. Statistical Analysis:

We extended the original analysis to estimate the independent effect of IIH on stroke and cardiovascular risks, accounting for the confounding effect of obesity. Our approach involved indirect standardization and adjustment with the application of a standardized morbidity ratio (SMR) approach [18–22], adapted to account for obesity as a confounding variable in relationship with IIH in women around the UK. To estimate the incidence of events in both the IIH and control cohorts under a hypothetical scenario of normal weight, we employed an adjustment method based on the average HR for obesity contributing to the event risk in women compared to healthy weight women in 13-year interval from the literature. This approach operates under the assumption that the HR remains constant throughout the 13-year study period and that the impact of obesity on the estimated events is independent of IIH status. We utilized Python 3.12 and its’ associated statistical libraries to perform our statistical analysis. Initially, we calculated the observed HR for each event in the IIH group compared to the control group. Subsequently, we adjusted this observed HR by obesity HR to estimate the HR for IIH independent of obesity. Based on the current evidence, the average estimated HR of obesity contributing to composite CVD is 2.89 [23–29]. For obesity, ischemic stroke, and TIA risk, it is estimated around HR= 1.72 [23, 26, 30–36]. For obesity and heart failure risk, it is estimated around HR= 2.61 [37–43]. For obesity and hypertension risk, it is estimated around HR= 2.09 [44–50]. For obesity and IHD risk, it is estimated around HR= 1.8 [23, 24, 26, 28, 30, 51, 52]. And for obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus risk, it is estimated to be around HR= 4.0 [53–60].

We calculated the HR for each event in the IIH group compared to the control group through the following equation:

We then adjusted this observed HR by the established HR for obesity in association with the potential risk to estimate the HR for IIH independent of obesity:

Using this adjusted HR, we predicted the number of events in both groups under normative weight conditions:

For the IIH group:

For the control group:

Using this adjusted HR, we then calculated the predicted number of events in both the IIH and control groups under the assumption of normal weight. This was accomplished by applying the adjusted HR to the control group event rate and scaling for the respective group sizes. For the control group, we divided the observed events by obesity HR to estimate events under normal weight conditions.

This method allows for a comparative analysis of events risk between IIH and control populations, while attempting to control the confounding effect of obesity. It provides insight into the potential independent risk associated with IIH and allows for estimation of event rates under hypothetical normal weight conditions.

2.4. Ethical Considerations:

This study adhered to the ethical approval obtained by Adderley et al. [7] from the NHS South-East Multicenter Research Ethics Committee. We did not involve direct analysis of the dataset rather than building customized statistical modelling based on the provided data and metrics from Adderley et al. research paper [7].

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics:

The original retrospective cohort study by Adderley et al. [7] encompassed 29,885 participants, stratified into 2,760 (9.2%) women with IIH and 27,125 (90.8%) controls. The incident cohort comprised 48.2% and 46.7% of the IIH and control groups, respectively. Both cohorts were predominantly under 60 years of age (98.1% IIH, 95.2% control), with identical median ages of 32.1 years (IQR: 25.62–42.00 IIH, 25.71–42.06 control). Socioeconomic status, assessed via Townsend Deprivation Quintiles, showed a comparable distribution between groups, with a slight overrepresentation of controls in the least deprived quintiles. Smoking habits differed significantly: the IIH cohort exhibited higher rates of current smoking (30.8% vs 22.6%) and lower rates of non-smoking (46.5% vs 55.5%).

Anthropometric data revealed marginally higher median BMI in the IIH group (34.80, IQR: 29.30–40.30) compared to controls (34.30, IQR: 29.00–39.70). Notably, both groups demonstrated a high prevalence of obesity (BMI >30), affecting 62.6% and 60.9% of the IIH and control cohorts, respectively. Comorbidity profiles and pharmacological interventions showed distinct patterns. The IIH cohort demonstrated a higher prevalence of migraine (21.0% vs. 11.9%), hypertension (13.8% vs. 9.2%), and marginally increased rates of lipid-lowering medication use (6.5% vs. 5.8%). Furthermore, baseline cardiovascular morbidity was more pronounced in the IIH group, with elevated rates of ischemic heart disease (1.3% vs. 0.9%) and ischemic stroke/TIA (1.7% vs 0.7%). Interestingly, type 2 diabetes mellitus prevalence was slightly lower in the IIH cohort (4.7% vs. 5.2%) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of the Included Individuals in the Original Study.

| Variable | Number, (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Women With IIH (Exposed Group) | Women Without IIH (Control Group) | |

| Population | 2760 (9.2) | 27 125 (90.8) |

| Incident Cohort | 1331 (48.2) | 12 679 (46.7) |

| Population Aged < 60 y | 2709 (98.1) | 25 811 (95.2) |

| Age, Median (IQR), y | 32.1 (25.62–42.00) | 32.1 (25.71–42.06) |

| Townsend Deprivation Quintile | ||

| 1 (Least deprived) | 361 (13.1) | 4268 (15.7) |

| 2 | 381 (13.8) | 4397 (16.2) |

| 3 | 532 (19.3) | 5174 (19.1) |

| 4 | 538 (19.5) | 5122 (18.9) |

| 5 (Most deprived) | 454 (16.5) | 4134 (15.2) |

| Missing data | 494 (17.9) | 4030 (14.9) |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Nonsmoker | 1284 (46.5) | 15 058 (55.5) |

| Ex-smoker | 502 (18.2) | 4573 (16.9) |

| Smoker | 849 (30.8) | 6134 (22.6) |

| Missing data | 125 (4.5) | 1360 (5.0) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 34.80 (29.30–40.30) | 34.30 (29.00–39.70) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | ||

| <25 | 246 (8.9) | 2561 (9.4) |

| 25–30 | 416 (15.1) | 4203 (15.5) |

| >30 | 1728 (62.6) | 16 514 (60.9) |

| Missing data | 370 (13.4) | 3847 (14.2) |

| Current lipid prescription | 180 (6.5) | 1572 (5.8) |

| Migraine | 580 (21.0) | 3247 (11.9) |

| Outcomes at Baseline | ||

| Heart Failure | 8 (0.3) | 58 (0.2) |

| IHD | 35 (1.3) | 245 (0.9) |

| Ischemic Stroke / TIA | 46 (1.7) | 189 (0.7) |

| Hypertension | 380 (13.8) | 2500 (9.2) |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | 130 (4.7) | 1425 (5.2) |

Abbreviations: IIH= Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension; IQR= Interquartile Range; BMI= Body Mass Index; IHD= Ischemic Heart Disease; TIA= Transient Ischemic Attack.

3.2. Statistical Analysis:

In this analysis, we employed four distinct statistical models to elucidate the complex interrelationships between IIH, obesity, and CVD risk. These models were strategically designed to disentangle the individual and combined effects of IIH and obesity on CVD outcomes.

Model 1 (Obese IIH vs Obese Control) was constructed to isolate the effect of IIH within an obese population, effectively controlling for the confounding factor of adiposity. Model 2 (Obese IIH vs Non-obese Control) provided a comprehensive view of the combined impact of IIH and obesity compared to individuals without either condition. Model 3 (Non-obese IIH vs Obese Control) offered a unique perspective, juxtaposing the cardiovascular risks associated with IIH in non-obese individuals against those attributed to obesity alone. Model 4 (Non-obese IIH vs. Non-obese Control) isolated the impact of IIH in a non-obese population, providing critical insights into the condition’s effects independent of obesity (Table 2).

Table 2:

Risk Contribution Calculations According to Different Hazard Regression Models.

| Outcome | Women With IIH (Exposed Group) | Women Without IIH (Control Group) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite CVD | |||

| Population, No. | 2613 | 26 356 | NA |

| Outcome events, No. (%) | 68 (2.5) | 328 (1.2) | NA |

| Person-years | 12 809 | 132 930 | NA |

| Crude incidence rate per 1000 person-years | 5.31 | 2.47 | NA |

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 3.50 (1.34–7.11) | 3.72 (1.51–7.39) | NA |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||

| Model 1 | 2.15 [1.66 – 2.79] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 2 | 6.19 [4.58 – 8.36] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 3 | 0.76 [0.50 – 1.15] | NA | 0.2 |

| Model 4 | 2.18 [1.41 – 3.39] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Heart Failure | |||

| Population, No. | 2735 | 26 989 | NA |

| Outcome events, No. (%) | 17 (0.6) | 78 (0.3) | NA |

| Person-years | 13 445 | 136 357 | NA |

| Crude incidence rate per 1000 person-years | 1.26 | 0.57 | NA |

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 3.58 (1.38–7.26) | 3.77 (1.52–7.50) | NA |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||

| Model 1 | 2.21 [1.31 – 3.74] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 2 | 5.75 [3.17 – 10.42] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 3 | 0.91 [0.42 – 1.97] | NA | 0.81 |

| Model 4 | 2.37 [1.04 – 5.39] | NA | 0.04 * |

| IHD | |||

| Population, No. | 2698 | 26 749 | NA |

| Outcome events, No. (%) | 27 (0.9) | 131 (0.5) | NA |

| Person-years | 13 216 | 134 521 | NA |

| Crude incidence rate per 1000 person-years | 2.04 | 0.97 | NA |

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 3.56 (1.37–7.20) | 3.73 (1.51–7.42) | NA |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||

| Model 1 | 2.10 [1.39 – 3.17] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 2 | 3.76 [2.42 – 5.85] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 3 | 1.17 [0.68 – 1.99] | NA | 0.57 |

| Model 4 | 2.09 [1.20 – 3.65] | NA | <.01 * |

| Stroke/TIA | |||

| Population, No. | 2674 | 26 755 | NA |

| Outcome events, No. (%) | 40 (1.5) | 181 (0.7) | NA |

| Person-years | 13 115 | 135 271 | NA |

| Crude incidence rate per 1000 person-years | 3.05 | 1.34 | NA |

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 3.51 (1.34–7.17) | 3.76 (1.52–7.47) | NA |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||

| Model 1 | 2.28 [1.62 – 3.21] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 2 | 3.93 [2.73 – 5.66] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 3 | 1.37 [0.89 – 2.09] | NA | 0.15 |

| Model 4 | 2.36 [1.51 – 3.67] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Hypertension | |||

| Population, No. | 2232 | 23 566 | NA |

| Outcome events, No. (%) | 148 (6.2) | 1059 (4.3) | NA |

| Person-years | 10 505 | 115 800 | NA |

| Crude incidence rate per 1000 person-years | 14.09 | 9.15 | NA |

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 3.20 (1.26–6.40) | 3.48 (1.43–6.94) | NA |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||

| Model 1 | 1.54 [1.30 – 1.83] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 2 | 3.22 [2.68 – 3.86] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 3 | 0.77 [0.61 – 0.97] | NA | 0.03 * |

| Model 4 | 1.61 [1.26 – 2.05] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Type 2 Diabetes | |||

| Population, No. | 2510 | 24 901 | NA |

| Outcome events, No. (%) | 120 (4.6) | 799 (3.1) | NA |

| Person-years | 12 300 | 125 947 | NA |

| Crude incidence rate per 1000 person-years | 9.76 | 6.34 | NA |

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 3.49 (1.34–6.94) | 3.62 (1.47–7.27) | NA |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||

| Model 1 | 1.54 [1.27 – 1.86] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 2 | 6.14 [4.90 – 7.70] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 3 | 0.40 [0.28 – 0.57] | NA | <.001 ** |

| Model 4 | 1.59 [1.09 – 2.32] | NA | 0.02 * |

Denotes statistical significance,

Denotes high statistical significance

Abbreviations: IIH= Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension; CVD= Cardiovascular Disease; IQR= Interquartile Range; IHD= Ischemic Heart Disease; CI= Confidence Interval.

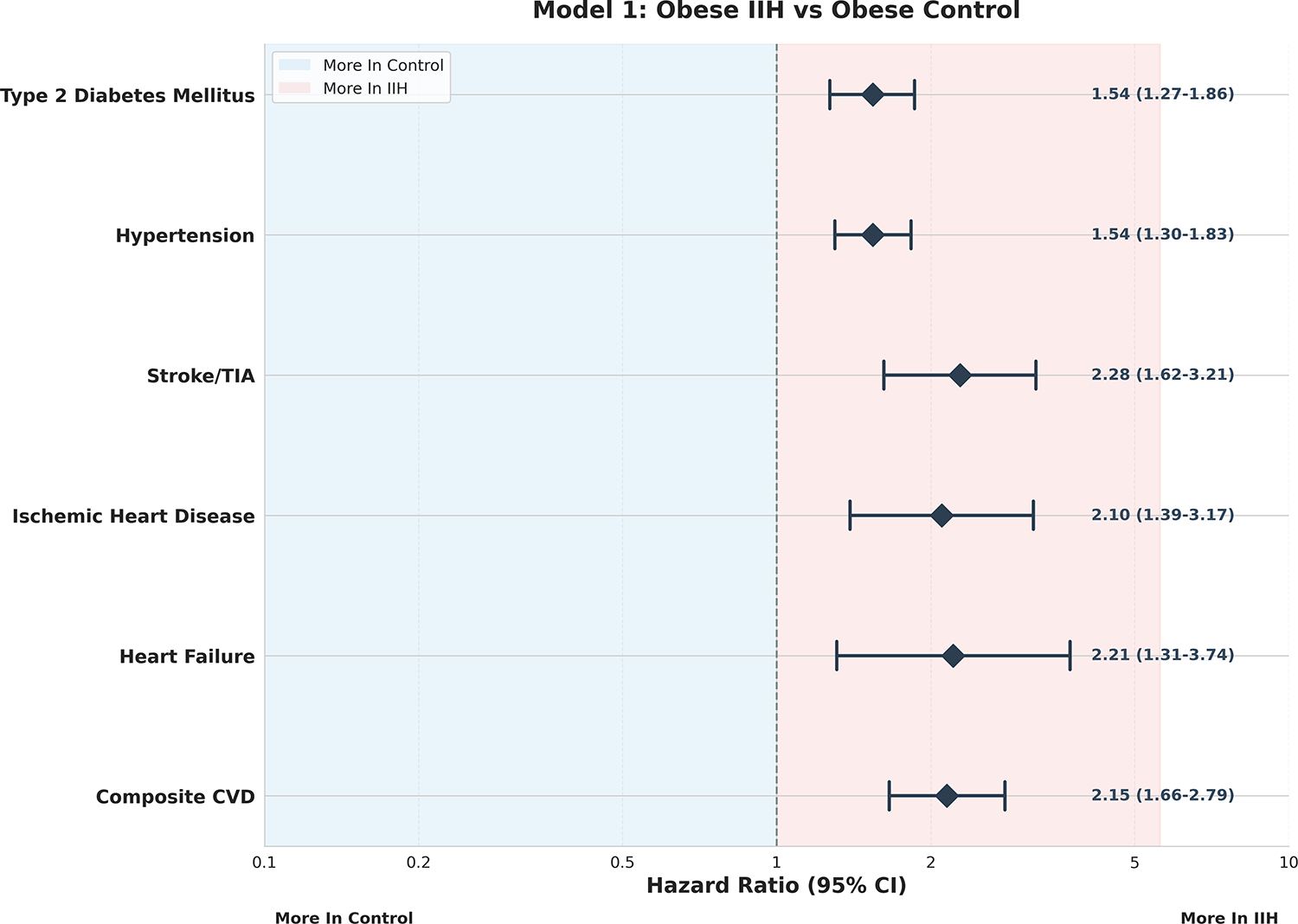

Our findings revealed a nuanced and clinically significant relationship between IIH, obesity, and cardiovascular risk. In Model 1 Figure 1, IIH was consistently associated with elevated risks across all measured outcomes. The risk ratios (RR) ranged from 1.54 (95% CI: 1.27–1.86, p<0.001) for type 2 diabetes mellitus to 2.28 (95% CI: 1.62–3.21, p<0.001) for stroke/TIA. This uniform pattern of risk elevation suggests that IIH confers additional cardiovascular risk beyond that attributed to obesity alone, a finding of relevance in clinical risk stratification.

Figure 1:

Model 1 – Obese IIH vs Obese Control Forest Plot.

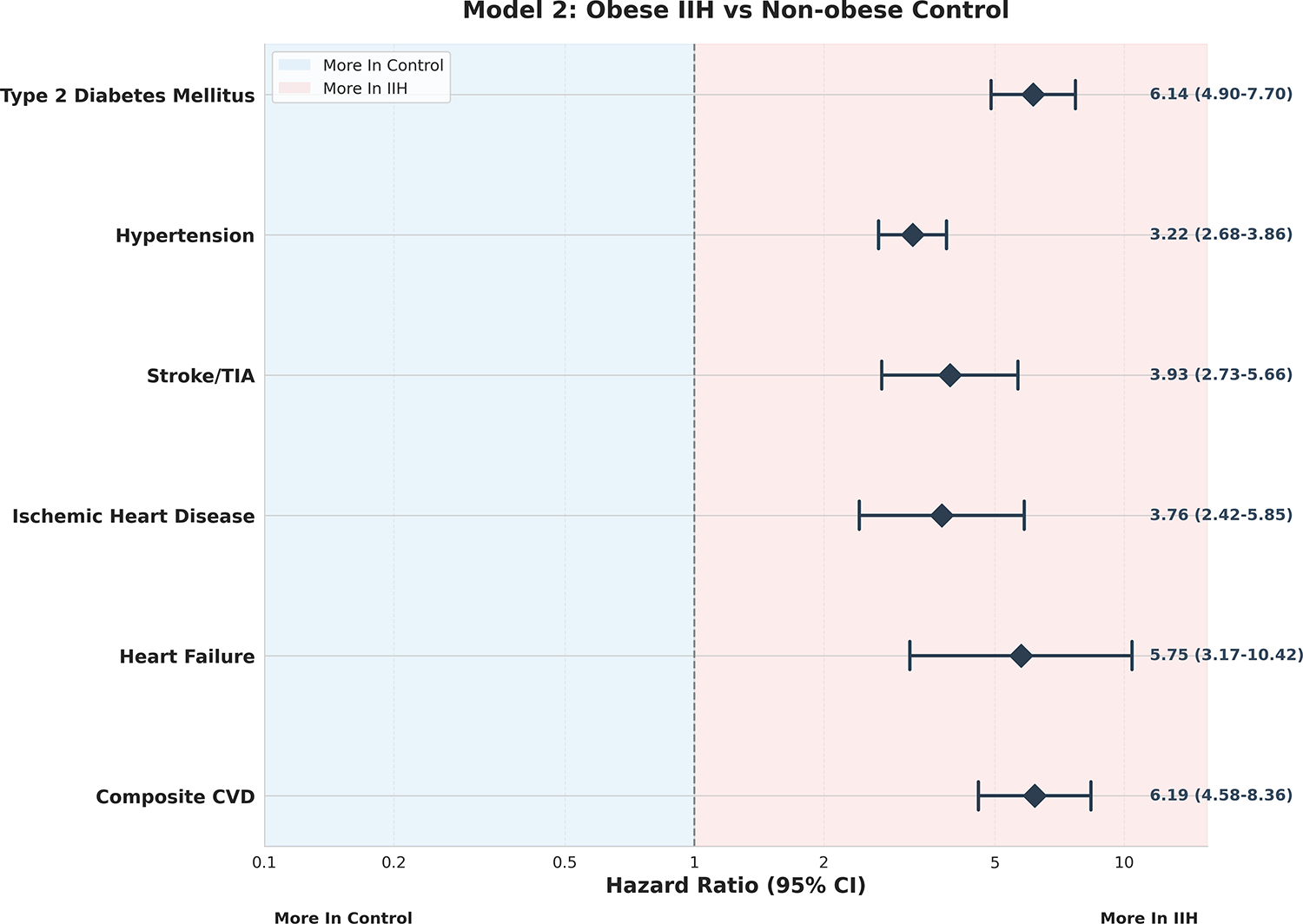

Model 2, Figure 2 demonstrated even more pronounced risk elevations, with the composite CVD risk reaching a striking RR of 6.19 (95% CI: 4.58–8.36, p<0.001). This marked increase suggests a potential synergistic effect between IIH and obesity on cardiovascular health, which may have significant implications for patient management and therapeutic interventions. Notably, the risk for heart failure in this model was particularly elevated (RR 5.75, 95% CI: 3.17–10.42, p<0.001), highlighting the need for vigilant cardiac monitoring in obese IIH patients.

Figure 2:

Model 2 – Obese IIH vs Non-Obese Control Forest Plot.

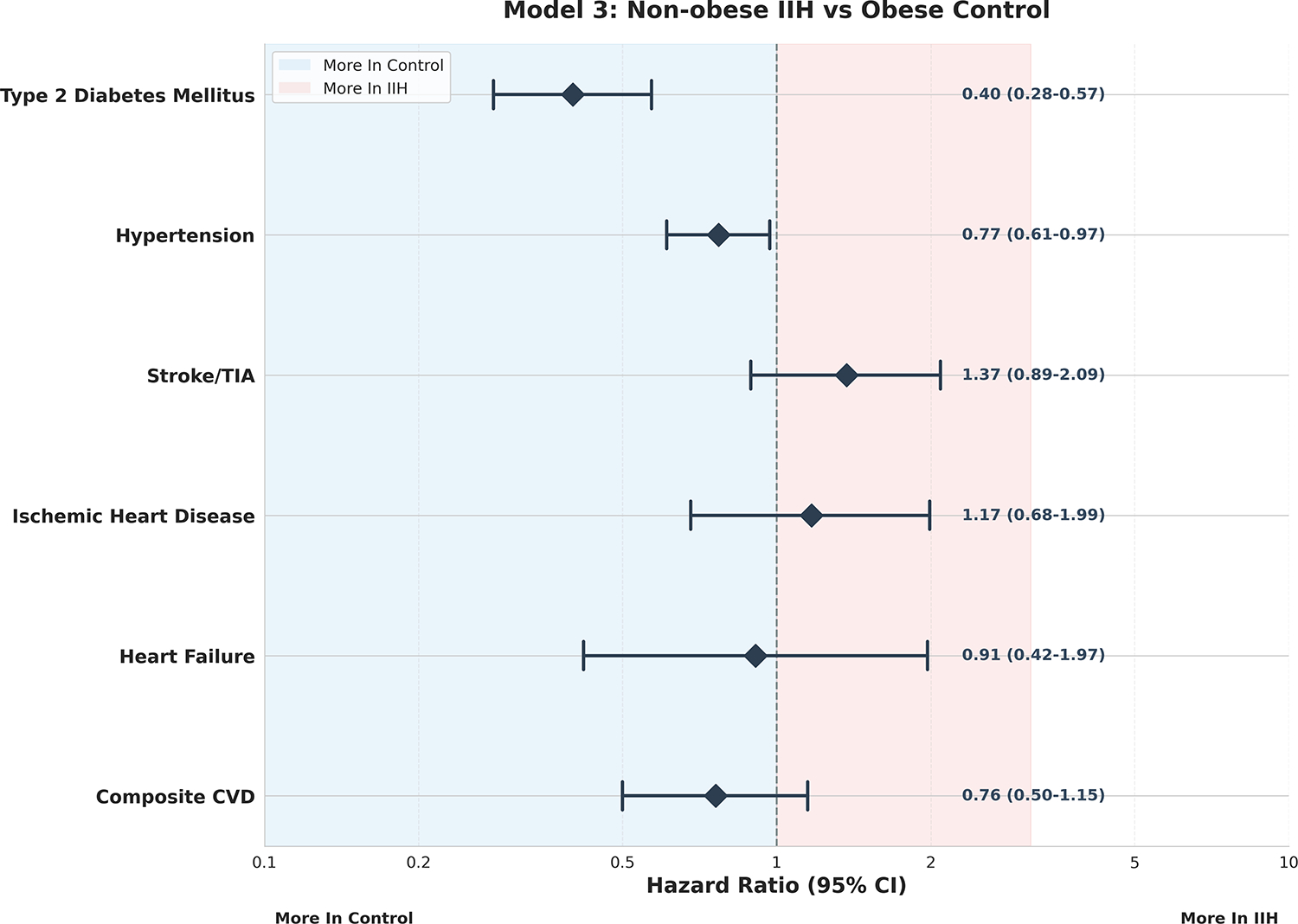

Interestingly, Model 3, Figure 3, presented a more complex picture. The non-significant risk ratios for most outcomes in this model suggest that non-obese individuals with IIH may not have significantly different CVD risks compared to obese individuals without IIH. This finding underscores the profound impact of obesity on cardiovascular health, potentially rivaling or even overshadowing the effects of IIH in certain contexts. Of note in this model was the significantly reduced risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in non-obese IIH patients compared to obese controls (RR 0.40, 95% CI: 0.28–0.57, p<0.001). This intriguing paradox may offer valuable insights into the underlying pathophysiology of both conditions and warrants further mechanistic investigation.

Figure 3:

Model 3 – Non-Obese IIH vs Obese Control Forest Plot.

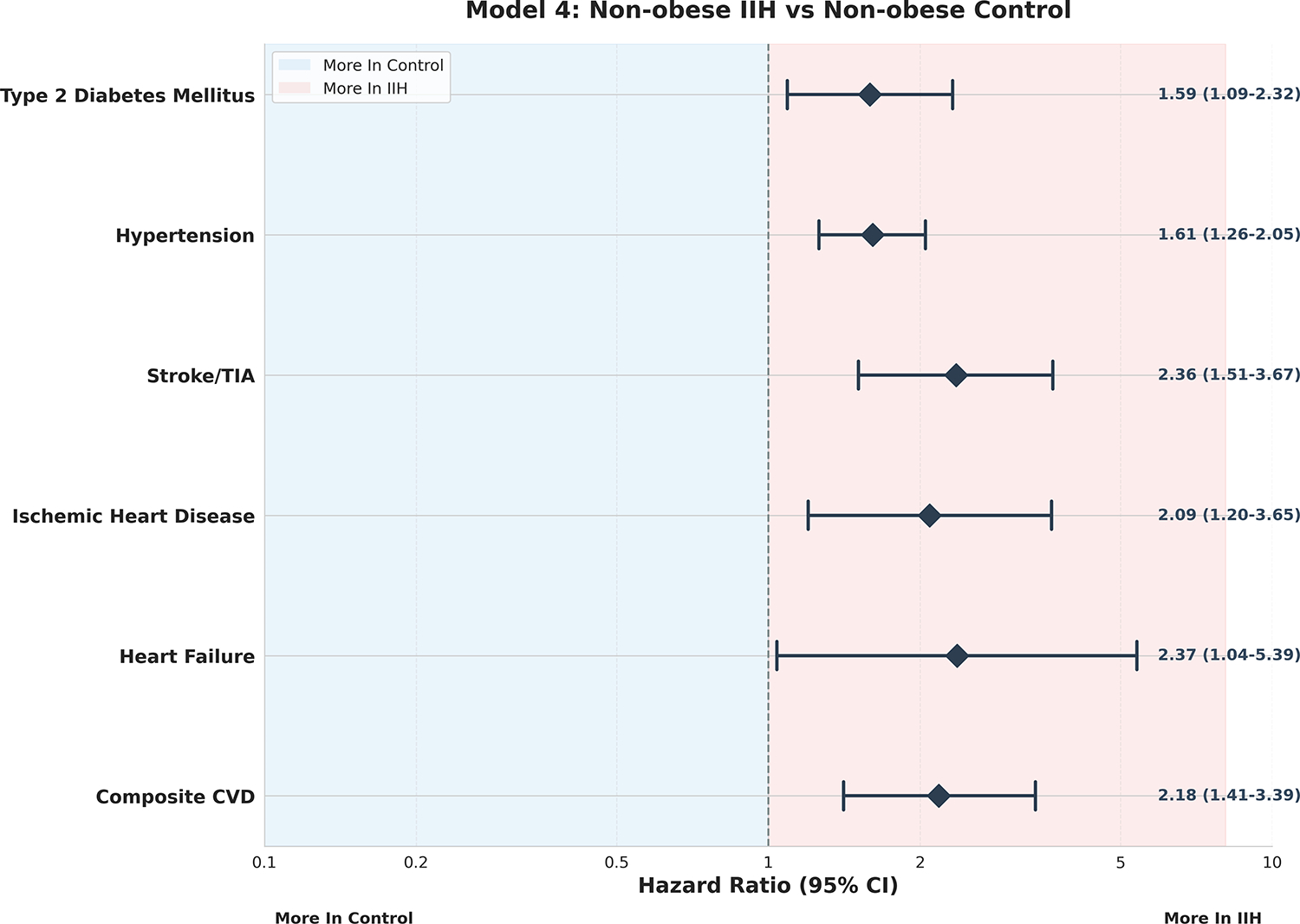

Model 4, Figure 4 provided robust corroboration of IIH as an independent risk factor, with significant risk elevations observed across all outcomes in non-obese IIH patients compared to non-obese controls. The composite CVD risk in this model (RR 2.18, 95% CI: 1.41–3.39, p<0.001) closely mirrored that observed in Model 1, further supporting the notion that IIH confers cardiovascular risk independent of obesity status. This finding has important implications for the management of non-obese IIH patients, who may be at underappreciated cardiovascular risk.

Figure 4:

Model 4 – Non-Obese IIH vs Non-Obese Control Forest Plot.

Ranking the CVD risks for IIH patients based on our data reveals the highest risk ratios in Model 2, with the following hierarchy: composite CVD (RR 6.19) > heart failure (RR 5.75) > stroke/TIA (RR 3.93) > ischemic heart disease (RR 3.76). This stratification underscores the critical importance of addressing both IIH and obesity in our highest-risk patients and may inform the development of targeted screening and intervention protocols. The data on type 2 diabetes mellitus warrant special consideration. The 6.14-fold increased risk (95% CI: 4.90–7.70, p<0.001) observed in obese IIH patients compared to non-obese controls (Model 2) is particularly striking. This marked elevation, coupled with the paradoxical risk reduction in non-obese IIH patients (Model 3), suggests a complex interplay between IIH, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction. These findings raise intriguing questions about potential shared pathophysiological mechanisms and may open new avenues for research into the neuroendocrine aspects of IIH. Hypertension, a known risk factor for both CVD and IIH progression, showed a consistent pattern of elevated risk across Models 1, 2, and 4. However, the reduced risk observed in Model 3 (RR 0.77, 95% CI: 0.61–0.97, p=0.03) adds another layer of complexity to our understanding of the relationship between IIH, obesity, and blood pressure regulation.

4. Discussion

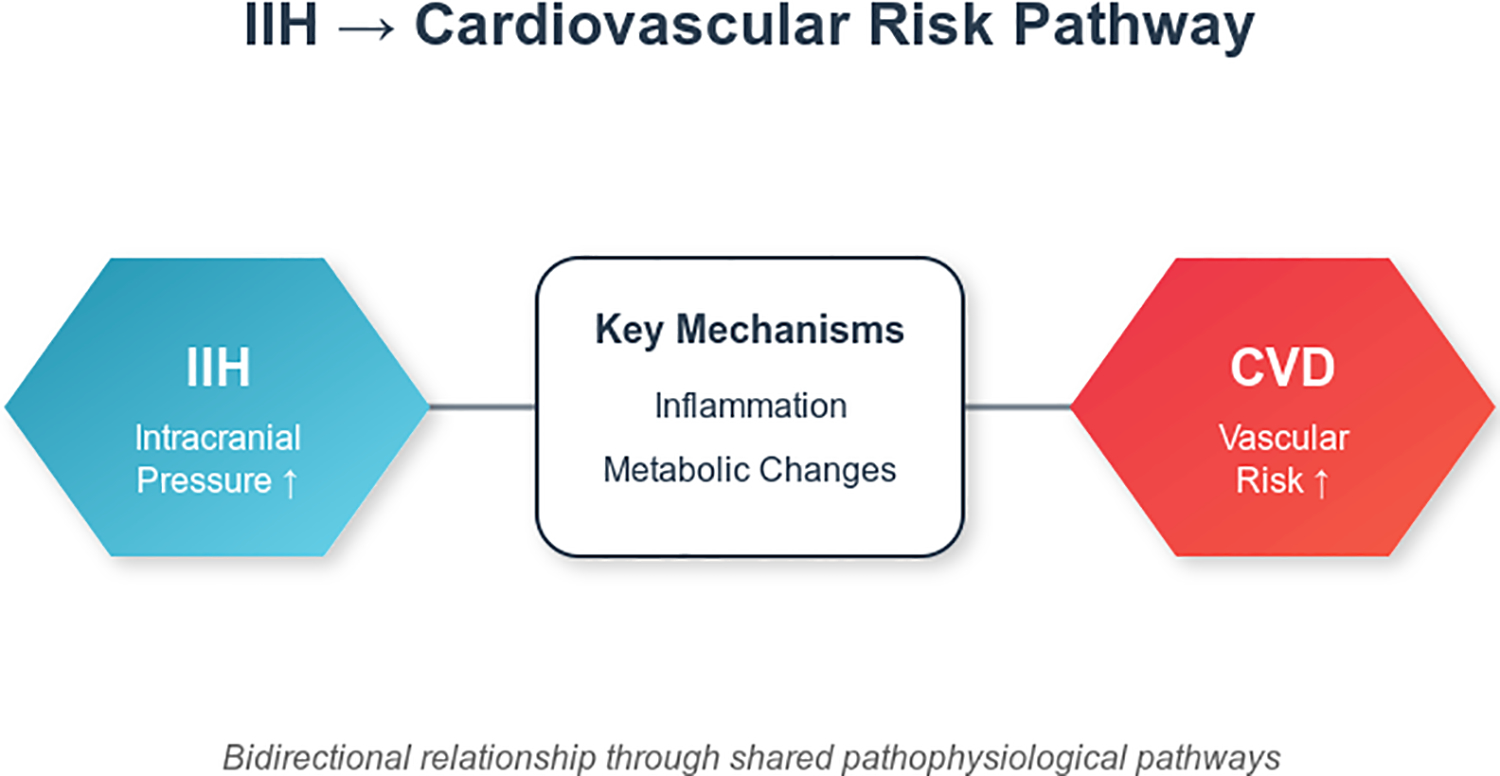

In our obesity-adjusted analysis, we have uncovered several significant findings that advance our understanding of how IIH influences CVD outcomes. Our primary analysis demonstrated that IIH independently raises CVD risk, as we observed consistent risk elevations (RR= 1.54 to 2.28) across CVD outcomes in our obesity-matched cohorts. Perhaps our most striking finding was the synergistic interaction between IIH and obesity, we found a 6.19-fold increased risk of composite CVD events (95% CI: 4.58–8.36, p<0.001) in obese IIH patients compared to non-obese controls. Through our modelling, we also discovered a metabolic relationship: non-obese IIH patients showed CVD risks comparable to obese controls which is significantly higher than non-obese controls (RR 2.18, 95% CI: 1.41–3.39, p<0.001). We were particularly intrigued by the paradoxical relationship we observed with type 2 diabetes risk which was elevated in obese IIH patients but reduced in non-obese IIH patients compared to obese controls, suggesting more complex metabolic mechanisms than previously recognized (Figure 5).

Figure 5:

IIH and CVD Risk Pathway.

The consistent elevation of risk ratios across Models 1 and 4, which compare IIH patients to controls within the same obesity strata, strongly suggests a distinct pathophysiological process intrinsic to IIH that exacerbates cardiovascular vulnerability. This finding aligns with emerging research on the neuroendocrine and metabolic perturbations in IIH. Recent metabolomic profiling by O’Reilly MW et al [8]. revealed a unique signature of altered androgen metabolism in CSF of IIH patients, characterized by elevated levels of testosterone and androstenedione. This androgen excess may represent a crucial link between IIH and cardiovascular risk through multiple mechanisms, including vascular dysfunction, inflammatory modulation, and metabolic dysregulation. Duckles and Miller [61] demonstrated that testosterone could induce vasoconstriction through both genomic and non-genomic pathways, potentially contributing to hypertension and altered cerebrovascular autoregulation in IIH.

The chronic elevation of in ICP is a characteristic of IIH may have direct and indirect effects on cardiovascular functions. Recent work by Wardlaw et al. [62] on the glymphatic system and intracranial fluid dynamics suggests that altered CSF flow and clearance in IIH may impair the removal of metabolic waste products from the brain. This accumulation of potentially toxic metabolites could exacerbate oxidative stress and vascular inflammation, contributing to the observed CVD risk.

The striking risk elevations observed in Model 2 (Obese IIH vs Non-obese Control) reveal a synergistic interaction between IIH and obesity that amplifies CVD risk beyond the sum of their individual effects. This synergy likely arises from the convergence of multiple pathophysiological processes, including adipokine dysregulation, neuroendocrine activation, and hemodynamic alterations. Recent work by Hornby et al. [63] demonstrates that IIH patients exhibit a distinct adipokine signature, with particularly elevated CSF leptin levels. The combination of systemic and central adipokine dysregulation may create a uniquely pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic state. Moreover, the evidence by Markey K et al. [64] suggests that IIH patients may have altered cortisol metabolism, potentially exacerbating the metabolic and CVD consequences of obesity-related hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction.

The paradoxical findings regarding type 2 diabetes risk in our study—elevated in obese IIH patients but reduced in non-obese IIH patients compared to obese controls—challenge our current understanding of metabolic risk in IIH. This observation may be explained by the concept of “metabolic flexibility” proposed by Goodpaster and Sparks [65]. In non-obese IIH patients, the altered androgen metabolism and potential changes in adipose tissue function may confer a degree of metabolic protection. The evidence by Mariniello et al. [66] on androgen effects on adipose tissue suggests that certain androgen profiles can enhance insulin sensitivity and improve glucose uptake in adipocytes. The specific androgen milieu in IIH may thus have differential effects depending on the overall metabolic context. Conversely, in obese IIH patients, this potential metabolic benefit may be overwhelmed by the profound insulin resistance and chronic inflammation associated with obesity. The interaction between obesity-related metabolic dysfunction and IIH-specific neuroendocrine perturbations may create a “perfect storm” for accelerated progression to type 2 diabetes [66].

Our findings necessitate a paradigm shift in the approach to cardiovascular risk management in IIH patients. We propose a multi-tiered strategy that includes enhanced risk stratification, targeted interventions, personalized metabolic management, and neuroendocrine modulation. The development of IIH-specific CVD risk calculators that incorporate novel biomarkers such as CSF androgen levels, adipokine profiles, and measures of intracranial pressure dynamics could significantly improve risk assessment in this population. Exploration of IIH-specific pharmacological interventions that address the unique pathophysiology of CVD risk in this population is warranted. For example, the potential use of selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs) to mitigate the adverse cardiovascular effects of androgen excess while preserving potential metabolic benefits merits investigation.

Future research directions should include longitudinal studies employing advanced imaging techniques to elucidate the temporal relationship between IIH onset, progression, and cardiovascular remodelling. Multi-omics approaches integrating genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics could unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed synergy between IIH and obesity in cardiovascular risk.

Interventional trials exploring the cardiovascular impact of IIH-specific treatments, including the potential cardioprotective effects of CSF diversion procedures or novel pharmacological agents targeting ICP regulation, are crucial. Additionally, investigation of sex-specific aspects of cardiovascular risk in IIH is essential, given the strong female predominance of the condition and the potential interaction with sex hormones.

The findings from our study reveal a complex, multifaceted relationship between IIH, obesity, and CVD risk that challenges existing paradigms and opens new frontiers in personalized medicine. The independent risk conferred by IIH, the synergistic effects with obesity, and the paradoxical metabolic findings underscore the need for a nuanced, mechanism-based approach to cardiovascular risk management in this unique patient population. As we continue to unravel the intricate pathophysiology of IIH, we move closer to developing targeted interventions that may not only alleviate the neurological symptoms of the condition but also mitigate its long-term cardiovascular consequences. The implications of our findings extend beyond IIH, offering potential insights into the broader interplay between neuroendocrine function, metabolic regulation, and cardiovascular health. The methodology of our paper has several limitations, at first the approach assumes that the HR and the values provided from the original data and the HR for obesity remains constant over the 13-year period and its applicable to both the IIH group and control group.

Secondly, it assumes that the effect of obesity on the events is independent of IIH status in each patient. Thirdly, the predicted events are based on the average HR for obesity from the current literature, which may not be fully representative of the study population in larger populations or another cohort. Also, the adjusted for IIH independent from obesity should be interpreted with caution, as it is an estimation based on the available data and assumptions. To further validate the findings, it would be better to perform tailored individual-level data analysis based on BMI subgroup analysis and sensitivity tests for IIH patients and counting for other potential cofounding variables in the cohort. Additionally, conducting a prospective study that directly compares IIH patients with normal weight controls would provide more comprehensive evidence for the independent effect of IIH on the proposed events.

5. Conclusions

Through our findings, we have established compelling evidence that IIH independently contributes to CVD risk beyond obesity alone. Our statistical modelling has revealed that IIH operates through both independent and obesity-synergistic pathways to elevate CVD risk. We consistently observed elevated risks across our obesity-stratified models, leading us to believe that IIH involves an intrinsic pathophysiological process that worsens CVD outcomes vulnerability. These findings align with emerging research on neuroendocrine dysregulation in IIH. Based on our results, we strongly advocate for a fundamental shift in IIH management to include comprehensive CVD risk assessment and mitigation. We believe developing IIH-specific CVD risk assessment tools and targeted interventions should be a priority. While we acknowledge the limitations of our study, including our assumptions about hazard ratio consistency and obesity effects, we have established a crucial foundation for future studies. We recommend prospective studies comparing IIH patients with normal-weight controls and deeper investigation of underlying mechanisms through multi-omics approaches. Our findings have significant implications for both clinical practice and future research in IIH management.

Funding Source:

The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through CTSA award number: UM1TR004400. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

N/A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mollan SP, Davies B, Silver NC, Shaw S, Mallucci CL, Wakerley BR, Krishnan A, Chavda SV, Ramalingam S, Edwards JJJoN, Neurosurgery, Psychiatry. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: consensus guidelines on management 2018: 1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mollan SP, Aguiar M, Evison F, Frew E, Sinclair AJ. The expanding burden of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Eye (London, England). 2019: 478 [ 10.1038/s41433-018-0238-5] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels AB, Liu GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta SL, Moster ML, Newman NJ, Biousse V, Lee AG, Wall M, Kardon R, Acierno MD, Corbett JJ, Maguire MG, Balcer LJ. Profiles of obesity, weight gain, and quality of life in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). American journal of ophthalmology. 2007: 635 [ 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.12.040] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kilgore KP, Lee MS, Leavitt JA, Mokri B, Hodge DO, Frank RD, Chen JJJO. Re-evaluating the incidence of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in an era of increasing obesity 2017: 697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wall M, McDermott MP, Kieburtz KD, Corbett JJ, Feldon SE, Friedman DI, Katz DM, Keltner JL, Schron EB, Kupersmith MJJJ. Effect of acetazolamide on visual function in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension and mild visual loss: the idiopathic intracranial hypertension treatment trial 2014: 1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalyvas AV, Hughes M, Koutsarnakis C, Moris D, Liakos F, Sakas DE, Stranjalis G, Fouyas IJAn. Efficacy, complications and cost of surgical interventions for idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a systematic review of the literature 2017: 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adderley NJ, Subramanian A, Nirantharakumar K, Yiangou A, Gokhale KM, Mollan SP, Sinclair AJ. Association Between Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension and Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases in Women in the United Kingdom. JAMA neurology. 2019: 1088 [ 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1812] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Reilly MW, Westgate CS, Hornby C, Botfield H, Taylor AE, Markey K, Mitchell JL, Scotton WJ, Mollan SP, Yiangou A, Jenkinson C, Gilligan LC, Sherlock M, Gibney J, Tomlinson JW, Lavery GG, Hodson DJ, Arlt W, Sinclair AJ. A unique androgen excess signature in idiopathic intracranial hypertension is linked to cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. JCI insight. 2019: [ 10.1172/jci.insight.125348] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colman BD, Boonstra F, Nguyen MN, Raviskanthan S, Sumithran P, White O, Hutton EJ, Fielding J, van der Walt AJJoN, Neurosurgery, Psychiatry. Understanding the pathophysiology of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH): a review of recent developments 2024: 375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yiangou A, Mollan SP, Sinclair AJJNRN. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a step change in understanding the disease mechanisms 2023: 769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Libien J, Kupersmith M, Blaner W, McDermott M, Gao S, Liu Y, Corbett J, Wall M, sciences NIIHSGJJotn. Role of vitamin A metabolism in IIH: Results from the idiopathic intracranial hypertension treatment trial 2017: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alimajstorovic Z, Mollan SP, Grech O, Mitchell JL, Yiangou A, Thaller M, Lyons H, Sassani M, Seneviratne S, Hancox T, Jankevics A, Najdekr L, Dunn W, Sinclair AJ. Dysregulation of Amino Acid, Lipid, and Acylpyruvate Metabolism in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension: A Non-targeted Case Control and Longitudinal Metabolomic Study. Journal of proteome research. 2023: 1127 [ 10.1021/acs.jproteome.2c00449] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Cairella G, Garbagnati F, Cappuccio FP, Scalfi L. Excess body weight and incidence of stroke: meta-analysis of prospective studies with 2 million participants. Stroke. 2010: e418 [ 10.1161/strokeaha.109.576967] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenland S, Morgenstern HJAroph. Confounding in health research 2001: 189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernán MA, Robins JMJAjoe. Using big data to emulate a target trial when a randomized trial is not available 2016: 758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu Y, Hajifathalian K, Ezzati M, Woodward M, Rimm EB, Danaei G, D’Este C. Metabolic mediators of the eff ects of body-mass index, overweight, and obesity on coronary heart disease and stroke: a pooled analysis of 97 prospective cohorts with 1.8 million participants 2014: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preston SH, Mehta NK, Stokes AJE. Modeling obesity histories in cohort analyses of health and mortality 2013: 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions: john wiley & sons; 2013.

- 19.Greenland SJE. Quantifying biases in causal models: classical confounding vs collider-stratification bias 2003: 300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneeweiss SJP, safety d. Sensitivity analysis and external adjustment for unmeasured confounders in epidemiologic database studies of therapeutics 2006: 291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernan M, Robins J. Causal inference: What if. boca raton: Chapman & hill/crc; 2020: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin DY, Psaty BM, Kronmal RAJB. Assessing the sensitivity of regression results to unmeasured confounders in observational studies 1998: 948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmiegelow MD, Andersson C, Køber L, Andersen SS, Olesen JB, Jensen TB, Azimi A, Nielsen MB, Gislason G, Torp-Pedersen C. Prepregnancy obesity and associations with stroke and myocardial infarction in women in the years after childbirth: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2014: 330 [ 10.1161/circulationaha.113.003142] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li TY, Rana JS, Manson JE, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rexrode KM, Hu FB. Obesity as compared with physical activity in predicting risk of coronary heart disease in women. Circulation. 2006: 499 [ 10.1161/circulationaha.105.574087] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song X, Tabák AG, Zethelius B, Yudkin JS, Söderberg S, Laatikainen T, Stehouwer CD, Dankner R, Jousilahti P, Onat A, Nilsson PM, Satman I, Vaccaro O, Tuomilehto J, Qiao Q. Obesity attenuates gender differences in cardiovascular mortality. Cardiovascular diabetology. 2014: 144 [ 10.1186/s12933-014-0144-5] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dikaiou P, Björck L, Adiels M, Lundberg CE, Mandalenakis Z, Manhem K, Rosengren A. Obesity, overweight and risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality in young women. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2021: 1351 [ 10.1177/2047487320908983] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medina-Inojosa JR, Batsis JA, Supervia M, Somers VK, Thomas RJ, Jenkins S, Grimes C, Lopez-Jimenez F. Relation of Waist-Hip Ratio to Long-Term Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. The American journal of cardiology. 2018: 903 [ 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.12.038] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kip KE, Marroquin OC, Kelley DE, Johnson BD, Kelsey SF, Shaw LJ, Rogers WJ, Reis SE. Clinical importance of obesity versus the metabolic syndrome in cardiovascular risk in women: a report from the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. Circulation. 2004: 706 [ 10.1161/01.Cir.0000115514.44135.A8] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Czernichow S, Kengne AP, Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Batty GD. Body mass index, waist circumference and waist-hip ratio: which is the better discriminator of cardiovascular disease mortality risk?: evidence from an individual-participant meta-analysis of 82 864 participants from nine cohort studies. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2011: 680 [ 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00879.x] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Rexrode KM, Kase CS, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE. Prospective study of body mass index and risk of stroke in apparently healthy women. Circulation. 2005: 1992 [ 10.1161/01.Cir.0000161822.83163.B6] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sánchez-Iñigo L, Navarro-González D, Fernández-Montero A, Pastrana-Delgado J, Martínez JA. Risk of incident ischemic stroke according to the metabolic health and obesity states in the Vascular-Metabolic CUN cohort. International journal of stroke : official journal of the International Stroke Society. 2017: 187 [ 10.1177/1747493016672083] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zahn K, Linseisen J, Heier M, Peters A, Thorand B, Nairz F, Meisinger C. Body fat distribution and risk of incident ischemic stroke in men and women aged 50 to 74 years from the general population. The KORA Augsburg cohort study. PloS one. 2018: e0191630 [ 10.1371/journal.pone.0191630] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen MQ, Shi WR, Wang HY, Sun YX. Sex Differences of Combined Effects Between Hypertension and General or Central Obesity on Ischemic Stroke in a Middle-Aged and Elderly Population. Clinical epidemiology. 2021: 197 [ 10.2147/clep.S295989] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaudhary D, Khan A, Gupta M, Hu Y, Li J, Abedi V, Zand R. Obesity and mortality after the first ischemic stroke: Is obesity paradox real? PloS one. 2021: e0246877 [ 10.1371/journal.pone.0246877] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horn JW, Feng T, Mørkedal B, Strand LB, Horn J, Mukamal K, Janszky I. Obesity and Risk for First Ischemic Stroke Depends on Metabolic Syndrome: The HUNT Study. Stroke. 2021: 3555 [ 10.1161/strokeaha.120.033016] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yatsuya H, Toyoshima H, Yamagishi K, Tamakoshi K, Taguri M, Harada A, Ohashi Y, Kita Y, Naito Y, Yamada M, Tanabe N, Iso H, Ueshima H. Body mass index and risk of stroke and myocardial infarction in a relatively lean population: meta-analysis of 16 Japanese cohorts using individual data. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2010: 498 [ 10.1161/circoutcomes.109.908517] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cordola Hsu AR, Xie B, Peterson DV, LaMonte MJ, Garcia L, Eaton CB, Going SB, Phillips LS, Manson JE, Anton-Culver H, Wong ND. Metabolically Healthy/Unhealthy Overweight/Obesity Associations With Incident Heart Failure in Postmenopausal Women: The Women’s Health Initiative. Circulation Heart failure. 2021: e007297 [ 10.1161/circheartfailure.120.007297] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Padwal R, McAlister FA, McMurray JJ, Cowie MR, Rich M, Pocock S, Swedberg K, Maggioni A, Gamble G, Ariti C, Earle N, Whalley G, Poppe KK, Doughty RN, Bayes-Genis A. The obesity paradox in heart failure patients with preserved versus reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. International journal of obesity (2005). 2014: 1110 [ 10.1038/ijo.2013.203] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halldin AK, Schaufelberger M, Lernfelt B, Björck L, Rosengren A, Lissner L, Björkelund C. Obesity in Middle Age Increases Risk of Later Heart Failure in Women-Results From the Prospective Population Study of Women and H70 Studies in Gothenburg, Sweden. Journal of cardiac failure. 2017: 363 [ 10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.12.003] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mørkedal B, Vatten LJ, Romundstad PR, Laugsand LE, Janszky I. Risk of myocardial infarction and heart failure among metabolically healthy but obese individuals: HUNT (Nord-Trøndelag Health Study), Norway. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014: 1071 [ 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.035] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawada T. Metabolically healthy obesity and cardiovascular events: A risk of obesity. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism. 2022: 763 [ 10.1111/dom.14628] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chandramouli C, Tay WT, Bamadhaj NS, Tromp J, Teng TK, Yap JJL, MacDonald MR, Hung CL, Streng K, Naik A, Wander GS, Sawhney J, Ling LH, Richards AM, Anand I, Voors AA, Lam CSP. Association of obesity with heart failure outcomes in 11 Asian regions: A cohort study. PLoS medicine. 2019: e1002916 [ 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002916] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kenchaiah S, Ding J, Carr JJ, Allison MA, Budoff MJ, Tracy RP, Burke GL, McClelland RL, Arai AE, Bluemke DA. Pericardial Fat and the Risk of Heart Failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021: 2638 [ 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.003] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee SK, Kim SH, Cho GY, Baik I, Lim HE, Park CG, Lee JB, Kim YH, Lim SY, Kim H, Shin C. Obesity phenotype and incident hypertension: a prospective community-based cohort study. Journal of hypertension. 2013: 145 [ 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835a3637] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kabootari M, Akbarpour S, Azizi F, Hadaegh F. Sex specific impact of different obesity phenotypes on the risk of incident hypertension: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Nutrition & metabolism. 2019: 16 [ 10.1186/s12986-019-0340-0] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewandowska M, Więckowska B, Sajdak S. Pre-Pregnancy Obesity, Excessive Gestational Weight Gain, and the Risk of Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of clinical medicine. 2020: [ 10.3390/jcm9061980] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nurdiantami Y, Watanabe K, Tanaka E, Pradono J, Anme T. Association of general and central obesity with hypertension. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2018: 1259 [ 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.05.012] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Curhan GC, Chertow GM, Willett WC, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Speizer FE, Stampfer MJ. Birth weight and adult hypertension and obesity in women. Circulation. 1996: 1310 [ 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1310] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gus M, Fuchs SC, Moreira LB, Moraes RS, Wiehe M, Silva AF, Albers F, Fuchs FD. Association between different measurements of obesity and the incidence of hypertension. American journal of hypertension. 2004: 50 [ 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.08.010] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Behboudi-Gandevani S, Ramezani Tehrani F, Hosseinpanah F, Khalili D, Cheraghi L, Kazemijaliseh H, Azizi F. Cardiometabolic risks in polycystic ovary syndrome: long-term population-based follow-up study. Fertility and sterility. 2018: 1377 [ 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.08.046] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Croft JB, Ballew C, Byers T. Relation of body fat distribution to ischemic heart disease. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I (NHANES I) Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. American journal of epidemiology. 1995: 53 [ 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117545] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quesada O, Lauzon M, Buttle R, Wei J, Suppogu N, Kelsey SF, Reis SE, Shaw LJ, Sopko G, Handberg E, Pepine CJ, Bairey Merz CN. Body weight and physical fitness in women with ischaemic heart disease: does physical fitness contribute to our understanding of the obesity paradox in women? European journal of preventive cardiology. 2022: 1608 [ 10.1093/eurjpc/zwac046] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okamura T, Hashimoto Y, Hamaguchi M, Obora A, Kojima T, Fukui M. Ectopic fat obesity presents the greatest risk for incident type 2 diabetes: a population-based longitudinal study. International journal of obesity (2005). 2019: 139 [ 10.1038/s41366-018-0076-3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee DH, Keum N, Hu FB, Orav EJ, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Comparison of the association of predicted fat mass, body mass index, and other obesity indicators with type 2 diabetes risk: two large prospective studies in US men and women. European journal of epidemiology. 2018: 1113 [ 10.1007/s10654-018-0433-5] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park SK, Ryoo JH, Oh CM, Choi JM, Jung JY. Longitudinally evaluated the relationship between body fat percentage and the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus: Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES). European journal of endocrinology. 2018: 513 [ 10.1530/eje-17-0868] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carey VJ, Walters EE, Colditz GA, Solomon CG, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Speizer FE, Manson JE. Body fat distribution and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. The Nurses’ Health Study. American journal of epidemiology. 1997: 614 [ 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009158] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anagnostis P, Paparodis RD, Bosdou JK, Bothou C, Macut D, Goulis DG, Livadas S. Risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with obesity: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Endocrine. 2021: 245 [ 10.1007/s12020-021-02801-2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sluik D, Boeing H, Montonen J, Pischon T, Kaaks R, Teucher B, Tjønneland A, Halkjaer J, Berentzen TL, Overvad K, Arriola L, Ardanaz E, Bendinelli B, Grioni S, Tumino R, Sacerdote C, Mattiello A, Spijkerman AM, van der AD, Beulens JW, van der Schouw YT, Nilsson PM, Hedblad B, Rolandsson O, Franks PW, Nöthlings U. Associations between general and abdominal adiposity and mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus. American journal of epidemiology. 2011: 22 [ 10.1093/aje/kwr048] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang J, Qian F, Chavarro JE, Ley SH, Tobias DK, Yeung E, Hinkle SN, Bao W, Li M, Liu A, Mills JL, Sun Q, Willett WC, Hu FB, Zhang C. Modifiable risk factors and long term risk of type 2 diabetes among individuals with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus: prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2022: e070312 [ 10.1136/bmj-2022-070312] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hong S, Park JH, Han K, Lee CB, Kim DS, Yu SH. Association Between Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease in Elderly Patients With Diabetes: A Retrospective Cohort Study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2022: e515 [ 10.1210/clinem/dgab714] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duckles SP, Miller VM. Hormonal modulation of endothelial NO production. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 2010: 841 [ 10.1007/s00424-010-0797-1] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wardlaw JM, Benveniste H, Nedergaard M, Zlokovic BV, Mestre H, Lee H, Doubal FN, Brown R, Ramirez J, MacIntosh BJ, Tannenbaum A, Ballerini L, Rungta RL, Boido D, Sweeney M, Montagne A, Charpak S, Joutel A, Smith KJ, Black SE. Perivascular spaces in the brain: anatomy, physiology and pathology. Nature reviews Neurology. 2020: 137 [ 10.1038/s41582-020-0312-z] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hornby C, Mollan SP, Botfield H, OʼReilly MW, Sinclair AJ. Metabolic Concepts in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension and Their Potential for Therapeutic Intervention. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society. 2018: 522 [ 10.1097/wno.0000000000000684] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Markey K, Mitchell J, Botfield H, Ottridge RS, Matthews T, Krishnan A, Woolley R, Westgate C, Yiangou A, Alimajstorovic Z, Shah P, Rick C, Ives N, Taylor AE, Gilligan LC, Jenkinson C, Arlt W, Scotton W, Fairclough RJ, Singhal R, Stewart PM, Tomlinson JW, Lavery GG, Mollan SP, Sinclair AJ. 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 inhibition in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Brain communications. 2020: fcz050 [ 10.1093/braincomms/fcz050] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goodpaster BH, Sparks LM. Metabolic Flexibility in Health and Disease. Cell metabolism. 2017: 1027 [ 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.015] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mariniello B, Ronconi V, Rilli S, Bernante P, Boscaro M, Mantero F, Giacchetti G. Adipose tissue 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 expression in obesity and Cushing’s syndrome. European journal of endocrinology. 2006: 435 [ 10.1530/eje.1.02228] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]