Abstract

Selective catalytic reduction of nitrogen oxides (NOx) by ammonia (NH3–SCR) over supported vanadium catalysts is a commercial technology for NOx abatement in combustion exhaust. The addition of tungsten oxide (WO3) significantly enhances the performance of supported vanadium catalysts (V2O5/TiO2), but the mechanism underlying this enhancement remains controversial. In this study, we employed combined operando spectroscopy (DRIFTS-UV–vis-MS) to investigate the dynamic state of active sites (acid sites and redox sites) on V2O5–WO3/TiO2 during the NH3–SCR reaction. Our findings confirmed that WO3 occupied the TiO2 surface and reduced the available surface sites for V2O5 anchoring, thus promoting the agglomeration of vanadia species. This structural effect significantly improved the reducibility of VOx on V2O5–WO3/TiO2 catalysts, consequently enhancing the efficiency for NOx reduction. The heightened reducibility rendered the reoxidation of vanadia species a rate-limiting step, resulting in the presence of vanadia species in a lower oxidation state (V4+) during the NH3–SCR reaction.

1. Introduction

Nitrogen oxides (NOx) emitted from vehicles and power plants lead to environmental problems, such as photochemical smog, acid rain, and haze.1−4 Selective catalytic reduction of NOx by ammonia (NH3–SCR) is a widely used technology for NOx reduction in heavy-duty diesel vehicles and power plants.5−9 The supported vanadium catalysts are the most important commercial SCR catalysts due to their superior catalytic activity and sulfur tolerance.8,10−18 Moreover, the addition of WO3 remarkably improves the capability of V2O5/TiO2 catalysts in practical applications, boosting low-temperature activity, broadening the operational temperature range, improving N2 selectivity, increasing resistance to toxicity, and enhancing thermal stability.12,19−26

Generally, there are two different types of active sites that participate in the NH3–SCR reaction over V2O5/TiO2 catalysts, which are acid sites and redox sites.27−31 First, NH3 adsorbs on the Lewis or Brønsted acid sites to form coordinated NH3 or NH4+ cations, respectively, which further react with NO or adsorbed nitrates to produce NH2NO or NH4NO2.30−34 Subsequently, these intermediates decompose to generate N2 and H2O. Meanwhile, adsorbed NH3 transfers an H atom to adjacent redox sites and reduces the vanadium species to a lower valence state (V4+), which is further reoxidized to complete the redox cycle.35−41 Recently, it was found that V=O could serve as both a redox site and an acid site in the NH3–SCR reaction, and that NH3 adsorption would suppress the redox cycle of V=O species.42

The promoting effect of WO3 on supported V2O5/TiO2 catalysts in the NH3–SCR reaction has been extensively investigated.16,19,20,43−46 Generally, two kinds of promotion effects, namely, structural and electronic effects, have been proposed for the promotion by WO3. Jaegers and his coworkers20 employed 51V MAS NMR spectroscopy to reveal the structural effects of WO3 on supported V2O5/TiO2 catalysts. They proposed that unreactive WO3 induces the generation of oligomeric vanadia species, which were proposed as the reactive sites for NOx abatement. In contrast, based on EPR spectra and TPR profiles, Grunert et al.46 suggested that WO3 directly interacts with vanadium species and prevents the agglomeration of large surface vanadium oxide islands. Moreover, Li et al.45 used Raman and TPR to research the effects of WO3 on V2O5–WO3/TiO2 catalysts and observed that the dispersion of WO3 on the titania surface significantly altered the acid characteristics and surface species on these catalysts. In contrast, Yang et al.19 proposed that WO3 addition increased the density and strength of Brønsted acid sites on vanadia catalysts, which were suggested to be the active components in NOx reduction.

Despite intensive research, there is still debate regarding whether the promoting effect of WO3 stems from structural or electronic effects. In this study, we employed combined operando spectroscopy (Diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier-transform spectroscopy–ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy–mass spectrometry, DRIFTS-UV–vis-MS)42,47−49 to study the surface intermediates, active sites, and reaction products of the NH3–SCR reaction over V2O5–WO3/TiO2 catalysts. This approach allowed us to resolve the promotion effect of WO3 on these supported vanadium catalysts in this reaction. This study provides new insights for designing high-efficiency SCR catalysts, and the combined operando spectroscopy employed herein can be applied to the study of other heterogeneous catalytic reactions.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Catalyst Preparation

Supported V2O5–WO3/TiO2 catalysts were prepared by a wet impregnation method.28,50 Specifically, an appropriate volume of aqueous ammonium metavanadate or ammonium metatungstate was impregnated into a suspension of TiO2 (Degussa P25) in water. After thorough mixing for 1 h, the water was evaporated in a rotary vacuum evaporator at 60 °C. Then, the samples were dried in an electric oven at 100 °C for 12 h and calcined at 450 °C for 5 h in a muffle furnace. As for the V2O5–WO3/TiO2 sample, the impregnation was repeated with the second component, ammonium metavanadate. Afterward, this sample was evaporated and calcined through the above steps. The V2O5 and WO3 loadings on these catalysts were 2 and 10 wt %, respectively, if applicable.

2.2. Activity Tests

The activity tests were accomplished in a fixed-bed reactor with an inner diameter of 6 mm.47 The reaction gas was comprised of 500 ppm of NO, 500 ppm of NH3, 1% H2O, and 5% O2 in N2 balance with a total flow rate of 500 mL min–1(GHSV = 100,000 h–1). 120 mg of sample with 40–60 mesh was used. The concentration of NO, NH3, NO2, and N2O was analyzed by an FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet iS 10).51 The conversions of NOx and NH3, and selectivity of N2 were calculated according to eqs 13.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where

The kinetics experiments were performed in the above fixed-bed reactor, and the reaction gas was the same as the activity testes. Internal and external diffusion effects had been eliminated according to our previous works.47,48 The NOx and NH3 conversions were kept below 20%. The Arrhenius plots for NOx reduction were drawn, and the apparent activation energies were calculated. The reaction rate (−RNOx) was calculated according to eq 4, where FNOx and XNOx represent the molar flow rate (mol s–1) and NOx conversion (%), respectively. W represents the sample weight (g).

| 4 |

2.3. Operando DRIFTS-MS

Operando diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier-transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS)–mass spectrometer (MS) experiments were carried out on an FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet iS 50).48,49 A powder sample (70 mg) was placed in a Harrick Scientific cell controlled by a Harrick ATC Temperature Controller. Typical reaction components were 500 ppm of NO, 500 ppm of NH3, 5% H2O (when added), and 5% O2 in an Ar balance (100 mL min–1). Water vapor was supplied by passing the gas flow over a water bottle. The DRIFTS spectra were collected in the range of 650–4000 cm–1 with a resolution of 4 cm–1 and an accumulation of 100 scans. Moreover, an online mass spectrometer (InProcess Instruments, GAM 200) was directly connected to the reaction cell to monitor the gaseous product of N2 (m/z = 28).

2.4. Operando DR-UV–vis

The ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) experiment was conducted on a UV–vis spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, LAMBDA 650) equipped with the Harrick Praying Mantis Attachment.48,49 Sample powder (70 mg) was placed into a Harrick Scientific cell controlled by a Harrick ATC Temperature Controller. The reaction components were 500 ppm of NO, 500 ppm of NH3, and 5% O2 in N2 balance (100 mL min–1). The spectra were collected in the range of 800–200 nm with a resolution of 1 nm. The DR-UV–vis data were collected by continuously measuring the absorbance at 700 nm with a time resolution of 1 s–1.

2.5. Characterizations

The X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were collected on an AXIS Supra spectrometer equipped with Al Kα radiation.52 The charging effect of the samples was eliminated by using the energy value of C 1s (284.8 eV).

3. Results

Supported vanadium catalysts were prepared using a wet impregnation method with TiO2 (Degussa P25) as the support.27,28,42 As shown in Figures 1 and S1, TiO2 exhibited low activity in the NH3–SCR reaction, achieving less than 5% of NOx conversion at temperatures below 400 °C. In contrast, the V2O5/TiO2 catalyst demonstrated significant activity for NOx reduction at temperatures above 250 °C. Notably, the addition of WO3 substantially enhanced the catalytic activity of V2O5/TiO2, especially at low temperatures. At 250 °C, the NOx conversion of V2O5–WO3/TiO2 was 62%, which was consistent with the literature.53,54 Specifically, the reaction rate for NOx reduction on V2O5–WO3/TiO2 (0.98 μmol g–1 s–1) was 3.5 times higher than that on V2O5/TiO2 (0.28 μmol g–1 s–1) at 250 °C. Moreover, the apparent activation energy for NOx reduction on V2O5–WO3/TiO2 (37.9 kJ mol–1) was higher than that on V2O5/TiO2 (24.1 kJ mol–1),17 but the reaction rate of V2O5–WO3/TiO2 was faster. This was because the reaction rate was not only affected by apparent activation energy but also influenced by the pre-exponential factor. And, the pre-exponential factor of the reaction reflected the collision frequency of the reaction, which was susceptible to the number of active sites and their intrinsic reactivity. Apparently, the pre-exponential factor of V2O5–WO3/TiO2 was larger than that of V2O5/TiO2, which can be seen from Figure 1b that the vertical intercept of V2O5–WO3/TiO2 was larger compared to V2O5/TiO2. Additionally, NH3 conversion exhibited a trend similar to that of NOx conversion, and the N2 selectivity was approximately equal to 100% on these catalysts (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

(a) Reaction rate for NOx reduction over supported vanadium catalysts. (b) Arrhenius plots for the rate of NOx reduction. Feed composition: 500 ppm of NO, 500 ppm of NH3, 5% O2, 1% H2O, N2 balance.

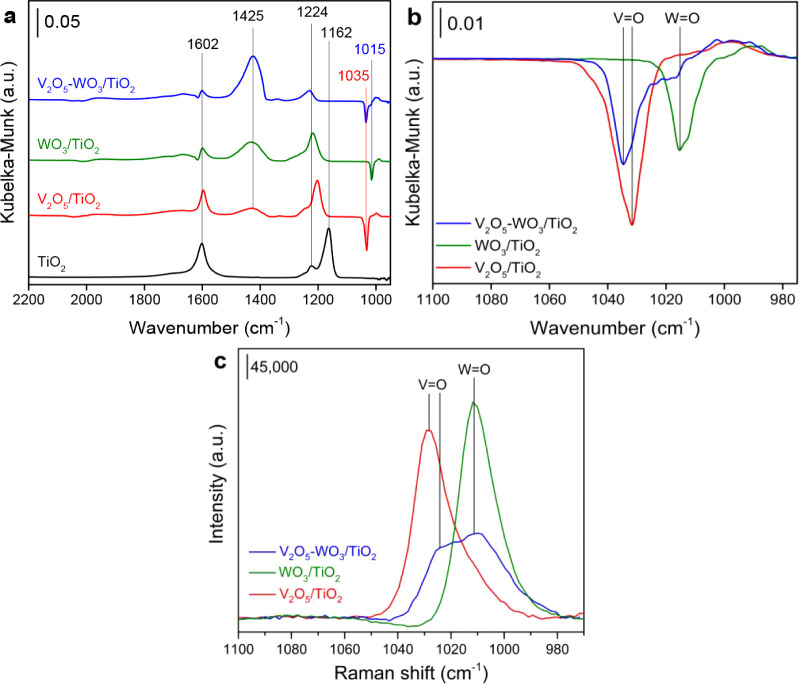

The acidic properties of supported vanadium catalysts were characterized by DRIFTS of NH3 adsorption (Figure 2). The samples were pre-exposed to NH3 at 200 °C for 2 h, followed by Ar purging for 30 min. Three peaks were observed for bare TiO2, which were assigned to the asymmetric stretch (1602 cm–1) and symmetric stretch (1224 and 1162 cm–1) of NH3 adsorbed on Ti sites.27,55 In addition to the above peaks, another band (1425 cm–1) was observed in the spectrum of V2O5/TiO2, attributed to the symmetric deformation mode of NH4+ cations on Brønsted acid sites.30 The Lewis acid sites on V2O5/TiO2 consisted of Ti sites and V sites. Moreover, a negative peak (1035 cm–1) assigned to the V=O stretching vibration was found for the V2O5/TiO2.42,56,57 The addition of WO3 significantly increased the number of Brønsted acid sites on WO3/TiO2, accompanied by a decrease in the number of Lewis acid sites. Thus, the Lewis acid sites on WO3/TiO2 included Ti sites and WOx sites. Similarly, a negative peak at 1015 cm–1 was observed on WO3/TiO2, assigned to the W=O stretching vibration. On the V2O5–WO3/TiO2, the presence of V2O5 and WO3 significantly enhanced the intensity of bands corresponding to Brønsted acid sites, while the number of Lewis acid sites was apparently decreased. In conclusion, the Lewis acid sites almost came from TiO2, and the Brønsted acid sites completely originated from VOx and WOx. More importantly, WO3 addition induced a blue-shift for the IR peak assigned to vanadia species (V=O) (Figure 2b), revealing the agglomeration of vanadia species on the V2O5–WO3/TiO2.56,57 Furthermore, the Raman signal of V=O (1030 cm–1) was observed on V2O5/TiO2, and this signal was weakened on V2O5–WO3/TiO2 (Figure 2c), consistent with previous literature.50 It confirmed that WO3 addition induced the formation of polymeric vanadia species. This structural effect of WO3 on the agglomeration of vanadia species was consistent with Jaegers’ work,20 in which oligomeric vanadia sites were suggested to act as the active sites for NOx reduction.

Figure 2.

(a,b) DRIFTS spectra of NH3 adsorption on V2O5–WO3/TiO2 at 200 °C. (c) Raman spectra of V2O5–WO3/TiO2 at 400 °C. Feed composition: (a,b) 500 ppm of NH3 in Ar balance; (c) 10% O2 in N2 balance.

Subsequently, the influence of water vapor on the acid sites of supported vanadium catalysts was further researched (Figure S2). Our previous work confirmed that water vapor could interact with the V=O site and induce the conversion from Lewis acid sites to Brønsted acid sites.42 Lewandowska and his coworkers also proposed that the addition of water vapor resulted in the dissociative adsorption of water on V2O5/TiO2, forming surface hydroxyl groups (V–OH) based on their DFT calculations and in situ Raman measurements.58,59 In this work, the introduction of water vapor also remarkably enhanced the intensity of W–OH Brønsted acid sites on WO3/TiO2, leading to a decrease in Lewis acid sites (Figure S2a). Hence, water vapor could also interact with W=O (Lewis acid site) and convert them into W–OH (Brønsted acid site). Consequently, on the V2O5–WO3/TiO2, the bands corresponding to Brønsted acid sites were much more intense than those of Lewis acid sites, especially under wet conditions (Figure S2b).

The performance of NH3 adsorbed on different acid sites was further evaluated by operando DRIFTS (Figures 3 and S3). The samples were pre-exposed to NH3 for 2 h, followed by Ar purging, and then exposed to NO+O2 for 15 min. The DRIFTS spectra were collected at 200 °C, considering that the reactivity of V2O5–WO3/TiO2 was too low to observe the change of adsorbed NH3 species at temperatures below 200 °C. At temperatures above 250 °C, the reaction rates of surface NH3 species were too fast, leading to hardly any observation of their change in the NH3–SCR process. The peaks for NH3 adsorbed on Lewis acid sites (NH3–Lewis, 1310–1150 cm–1) and Brønsted acid sites (NH3–Brønsted, 1540–1310 cm–1) were integrated (Figure S3). On the V2O5/TiO2, the number of NH3–Lewis was much greater than that of NH3–Brønsted, and the NH3–Lewis were gradually consumed after exposure to NO+O2. Instead, the NH3–Brønsted significantly increased in the first few minutes, followed by a continuous decrease for 15 min. This phenomenon was related to the transformation of Lewis acid sites to Brønsted acid sites under wet conditions, which had been confirmed in previous works.42,60 On WO3/TiO2, the introduction of NO only induced a slight conversion between Lewis acid sites and Brønsted acid sites, while adsorbed NH3 was hardly consumed. On V2O5–WO3/TiO2, by contrast, the number of NH3–Brønsted was much greater than that of NH3–Lewis. Notably, both NH3–Brønsted and NH3–Lewis were rapidly consumed after exposure to NO + O2, indicating their high reactivity for NOx reduction. Meanwhile, the slight increase in the concentration of NH3–Brønsted was attributed to the conversion of NH3–Lewis, consistent with that occurring on V2O5/TiO2. Therefore, it is hard to determine which acid sites show higher reactivity due to their easy interconversion. However, the presence of WO3 did increase the number of acid sites and also promoted their reactivity, especially for the Brønsted acid sites.

Figure 3.

Reactivity of NH3 adsorbed on different acid sites over (a) V2O5/TiO2, (b) WO3/TiO2, and (c) V2O5–WO3/TiO2 catalysts. The samples were pre-exposed to NH3 for 2 h, followed by Ar purging, and then exposed to NO + O2 for 15 min. Feed composition: 500 ppm of NH3, 500 ppm of NO, 5% of the O2 in Ar balance, 200 °C.

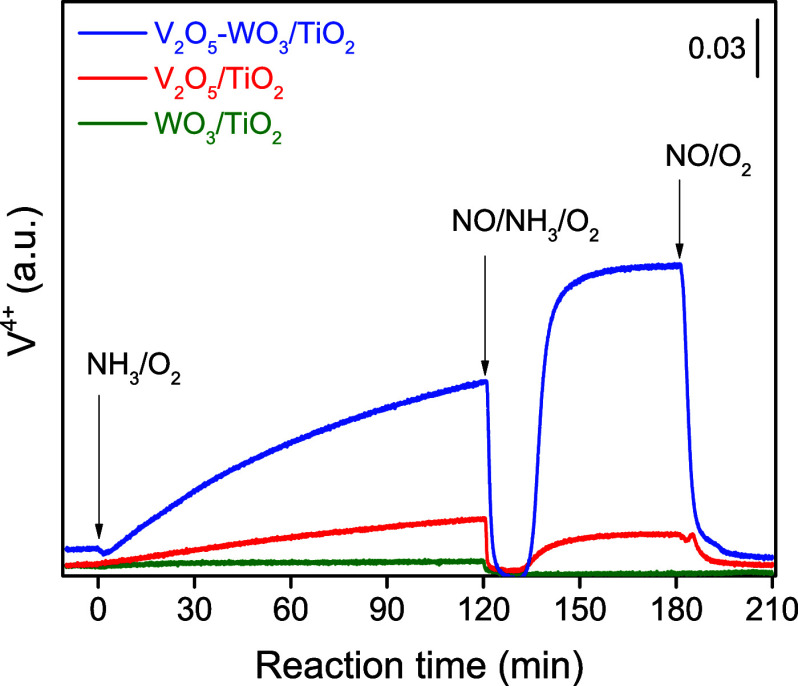

The redox capabilities of supported vanadium catalysts were further investigated by operando DR-UV–vis experiments. UV–vis spectra showed that TiO2 exhibited intense absorption only in the ultraviolet region (Figure S4). WO3/TiO2 showed a similar property to TiO2, indicating that WO3 had negligible influence. By contrast, V2O5/TiO2 showed moderate absorbance in the visible region. Besides, the addition of WO3 significantly enhanced the absorbance in the visible region. According to the literature,27,28 the absorbance at 800–600 nm is due to the d-d transition of V4+, whereas the absorbance at 400 nm is attributed to the charge transfer of V5+ (O2– → V5+). During the operando DR-UV–vis experiment, the dynamic state of the vanadium species (V4+) was investigated by monitoring the absorbance at 700 nm continuously. The absorbance (700 nm) on WO3/TiO2 remained unchanged during the CO reduction, revealing that neither TiO2 nor WO3 could affect this signal (Figure S5). Instead, CO reduction significantly enhanced the absorbance (700 nm) of V2O5/TiO2, indicating that V5+ species were reduced to V4+. Notably, the reduction was more intensive on V2O5–WO3/TiO2, revealing that WO3 addition enhanced the redox properties of vanadia species.

On V2O5/TiO2, the presence of NH3 slowly reduced the vanadia species in the absence of NO (first state in Figure 4). These vanadia species were suddenly reoxidized once exposed to NO, followed by a gradual reduction to reach a balanced state (second state in Figure 4). WO3/TiO2 showed little change during the above gas switching process, revealing that neither TiO2 nor WO3 showed reactivity for NOx reduction. On V2O5–WO3/TiO2, however, the introduction of NH3 remarkably reduced the vanadia species. Notably, this reduction is much slower compared to the reduction observed during the NH3–SCR reaction. When the feed was changed from NH3/O2 to NO/NH3/O2, these VOx species were quickly oxidized. In the steady-state NH3–SCR reaction (second state in Figure 4), vanadia species predominantly exist in the V4+ state, suggesting that the oxidation of the V4+ species occurred more slowly than the reduction of the V5+ species. Upon the removal of NH3 (third state in Figure 4), the V4+ species gradually reoxidized within the first 6 min, indicating that both the oxidation and reduction of vanadia species were rapid on V2O5–WO3/TiO2. Clearly, WO3 addition significantly enhanced the redox ability of vanadia species over V2O5–WO3/TiO2 in the NH3–SCR process.

Figure 4.

Operando DR-UV–vis experiment of a step-response NH3–SCR reaction at 200 °C on supported vanadium catalysts. The samples were pretreated in air for 1 h at 400 °C and successively exposed to (1) NH3/O2 (0–120 min), (2) NO/NH3/O2 (120–180 min), and (3) NO/O2 (180–210 min) at 200 °C.

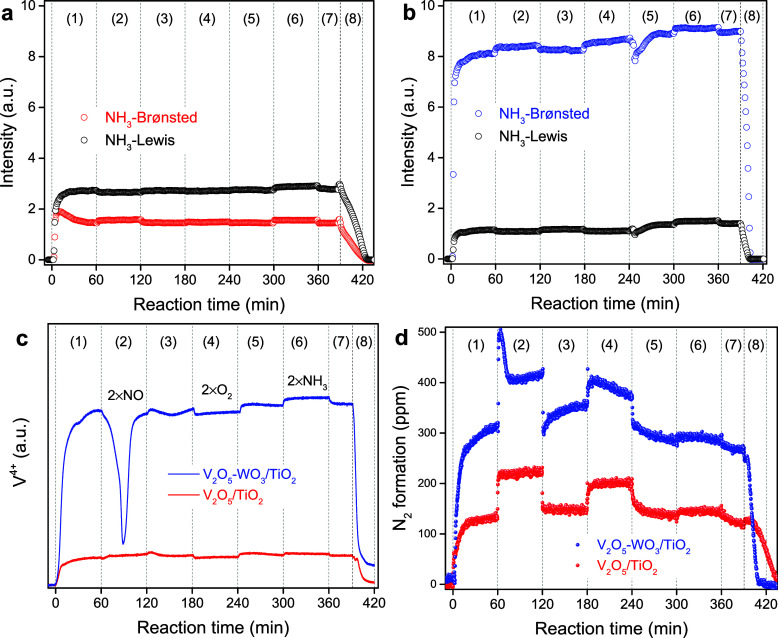

Moreover, a combined operando DRIFTS-UV–vis-MS experiment was performed to study the surface intermediates, active sites, and N2 formation during the NH3–SCR process (Figure 5). The samples were pretreated and successively exposed to different reaction atmospheres. On the V2O5/TiO2, the number of NH3–Lewis was higher than that of NH3–Brønsted, while they exhibited little change during gas switching (Figure 5a). On the V2O5–WO3/TiO2 (Figure 5b), in contrast, the amount of NH3–Brønsted was much more than that of NH3–Lewis, though they also showed little change during the above processes. The vanadia species on these samples were rather different during the above step-response reaction. On V2O5/TiO2, most vanadia species were in a higher valence state (V5+) and remained stable during the above processes. In contrast, the vanadia species on V2O5–WO3/TiO2 were mostly in a lower valence state (V4+). The results of XPS for V 2p (Figure S6) indicated that the vanadia species on V2O5/TiO2 and V2O5–WO3/TiO2 were mainly present in V5+,61 but it mostly existed in the form of V4+ on V2O5–WO3/TiO2 under the reaction conditions. It further proved that the addition of WO3 induced the reduction of vanadia species under reaction atmospheres, thus enhancing the redox capability of V2O5/TiO2 during the NH3–SCR reaction. Notably, the increase in the NO concentration induced a remarkable oxidation of V4+ species (Figure 5c), which were subsequently reduced to their original level. Afterward, the vanadia species were only slightly influenced by the changes in O2 and NH3 concentrations and were suddenly oxidized upon the removal of NH3. On V2O5/TiO2, N2 formation was significantly increased (from 140 to 220 ppm and from 150 to 200 ppm) when the concentrations of NO and O2 were increased, though the surface intermediates and vanadia valence showed little change in this process. On the V2O5–WO3/TiO2, notably, N2 formation was suddenly and greatly increased (from 310 to 500 ppm) by increasing the NO concentration, followed by a decrease to 410 ppm, consistent with the change in vanadia species. Similarly, increasing the O2 concentration also enhanced the N2 generation on this sample, while increasing the NH3 concentration showed little effect on this reaction.

Figure 5.

Dynamic change of adsorbed NH3 on (a) V2O5/TiO2, (b) V2O5–WO3/TiO2, (c) V4+ species, and (d) N2 formation by operando DRIFTS-UV–vis-MS experiment during NH3–SCR reaction. The samples were pretreated in O2/Ar for 1 h at 400 °C and then cooled to 200 °C, followed by successive exposure to (1) NO/NH3/O2, (2) 2NO/NH3/O2, (3) NO/NH3/O2, (4) NO/NH3/2O2, (5) NO/NH3/O2, (6) NO/2NH3/O2, (7) NO/NH3/O2, and (8) NO/O2, respectively. Typical feed conditions: 500 ppm of NO, 500 ppm of NH3, 5% of the O2 in Ar balance. The “2” means 2 times of the reactant concentration (e.g., “2 × NO” refers to 1000 ppm of NO).

A combined operando DRIFTS-UV–vis-MS experiment was further conducted on V2O5–WO3/TiO2 to study the dynamic changes in surface intermediates, vanadia valence, and reaction products during the NH3–SCR process (Figure 6). This sample was pre-exposed to a flow of NO/NH3/O2 for 2 h, and then different reactants (NO, NH3, or NO+NH3) were successively removed from the reaction stream. After the removal of NO (2nd step), both NH3–Brønsted and V4+ species decreased, whereas N2 formation rapidly stopped, revealing that gaseous NO mainly participated in the reaction without adsorption. Meanwhile, the intensity of the NH3–Lewis peaks increased slightly, possibly due to the conversion of NH3–Brønsted. After the removal of NH3 (4th step), both NH3–Brønsted and NH3-Lewis peaks decreased gradually, accompanied by the oxidation of V4+ species. However, the removal of gaseous NH3 had little effect on the formation of N2, indicating that this sample was saturated with excess adsorbed NH3, which could maintain the NOx reduction reaction for more than 10 min. Afterward, the introduction of NO (5th step) resulted in the rapid reduction of V5+ species within the first 3.5 min, which occurred faster than the oxidation of V4+ species observed in the fourth step. Subsequently, the removal of NO and NH3 induced a remarkable decrease in the NH3–Brønsted and V4+ species (6th step), while the introduction of reactants could rapidly restore the reaction. Afterward, NO and NH3 were successively removed, which induced a continuous decrease in the NH3–Brønsted and V4+ species (8th and 9th steps). In contrast, the addition of NO induced the rapid consumption of adsorbed NH3 to generate N2 as well as the rapid oxidation of V4+ species (10th step). Notably, the V4+ species showed precisely the same trend as NH3–Brønsted during the above procedures, revealing the presence of adsorbed NH3 on the V4+–OH Brønsted acid sites. Besides, NH3 adsorption appeared to suppress the oxidation of these V4+ species, which has also been observed on V2O5/TiO2.42 In contrast, NO could react with these adsorbed NH3 and help restore the V4+ species. Notably, the vanadia species were mainly present in a lower valence state (V4+) during this reaction, indicating that the reoxidation of V4+ species was the rate-limiting step of this reaction.

Figure 6.

Dynamic changes in (a) adsorbed NH3, (b) vanadia species, and (c) N2 formation during operando DRIFTS-UV–vis-MS experiment of step–response NH3–SCR reaction. The sample was pre-exposed to NO/NH3/O2 at 200 °C for 2 h and then successively exposed to (1) NO/NH3/O2, (2) NH3/O2, (3) NO/NH3/O2, (4) NO/O2, (5) NO/NH3/O2, (6) O2, (7) NO/NH3/O2, (8) NH3/O2, (9) O2, (10) NO/O2, and (11) NO/NH3/O2, respectively. Typical conditions: 500 ppm of NO, 500 ppm of NH3, and 5% of the O2 in an Ar balance.

4. Discussion

On supported V2O5/TiO2 catalysts, both Ti sites and V sites can serve as Lewis acid sites for NH3 adsorption, and V–OH groups can act as Brønsted acid sites to coordinate with NH3 and form NH4+ cations. WO3 addition remarkably increased the number of Brønsted acid sites on V2O5–WO3/TiO2, contributed by W–OH sites, accompanied by a significant decrease in Lewis acid sites. Similar to vanadia species, moisture could also induce the conversion of W=O (Lewis acid sites) to W–OH (Brønsted acid sites), thus remarkably increasing the number of Brønsted acid sites. On V2O5/TiO2, both Lewis acid sites and Brønsted acid sites participated moderately in NO reduction, while their reactivity was hard to determine due to the interconversion of them, which was induced by water vapor.

Operando DR-UV–vis confirmed that the presence of WO3 significantly enhanced the reducibility of vanadia species on the V2O5–WO3/TiO2, which was likely related to the formation of polymeric vanadyl species.42,62 Moreover, the adsorption of NH3 on Brønsted acid sites would suppress the oxidation of V4+–OH possibly due to the steric effect (Figure 6), which has been confirmed in our previous work.42 Consequently, the valence state of vanadia species was sensitive to the NO concentration such that NO could react with the NH3 adsorbed on V4+–OH, thus releasing the V4+–OH sites, ultimately inducing the rapid oxidation of V4+ species (Figure 5c). During the step–response experiment (Figure 6), the removal of gaseous NH3 induced the gradual consumption of adsorbed NH3 over a period of 10 min, while the formation of N2 was hardly affected. If the NH3 adsorbed on WO3 directly participated in the NOx reduction, the decrease in adsorbed NH3 would induce a gradual decrease in N2 formation. Rather, it was speculated that WO3 served as a pool for NH3 adsorption, which maintained the high efficiency of the catalyst for NOx reduction. Moreover, as WO3 provides active sites for NH3 adsorption, more vanadia species could be released to serve as redox sites, thus contributing to the improved catalytic activity. Another possibility was interactions between neighboring tungsten and vanadia species, such as induction and conjugation.46

On the V2O5/TiO2, the vanadia species were mainly present in a higher oxidation state (V5+) in the NH3–SCR process, indicating that their reduction was slow. On V2O5–WO3/TiO2, however, the vanadia species were mainly present in a lower oxidation state (V4+), attributed to the superior reducibility of vanadia species. The increase in the NO concentration induced a remarkable boost in N2 generation. The increase in O2 concentration greatly enhanced N2 formation, while it only slightly promoted the oxidation of vanadia species, indicating that the dehydrogenation was extremely fast and the reoxidation of V4+ species was the rate-limiting step on this sample under NH3–SCR conditions.

5. Conclusions

The promotion effect of WO3 on NH3–SCR over supported vanadium catalysts was researched by combined operando spectroscopy. WO3 occupied the surface of TiO2, reducing the available surface sites for vanadia anchoring and inducing the agglomeration of vanadia species. This structural effect significantly enhanced the reducibility of vanadia species on V2O5–WO3/TiO2, thus greatly improving the efficiency of NOx reduction. Furthermore, the increased reducibility made the reoxidation of vanadia species the rate-limiting step, resulting in their presence in a lower oxidation state (V4+) during the NH3–SCR reaction. Moreover, the addition of WO3 greatly increased the number of Brønsted acid sites on V2O5–WO3/TiO2, especially in the presence of water vapor.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC3704400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22276203), and the project of eco-environmental technology for carbon neutrality (RCEES-TDZ-2021-6).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c06372.

Catalytic activity of vanadia catalysts, DRIFTS spectra, UV–vis spectra, and XPS spectra (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through the contributions of all authors. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Anenberg S. C.; Miller J.; Minjares R.; Du L.; Henze D. K.; Lacey F.; Malley C. S.; Emberson L.; Franco V.; Klimont Z.; Heyes C. Impacts and mitigation of excess diesel-related NOx emissions in 11 major vehicle markets. Nature 2017, 545, 467–471. 10.1038/nature22086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter A.; Burrows J. P.; Nuss H.; Granier C.; Niemeier U. Increase in tropospheric nitrogen dioxide over China observed from space. Nature 2005, 437, 129–132. 10.1038/nature04092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu B. W.; Ma Q. X.; Liu J.; Ma J. Z.; Zhang P.; Chen T. Z.; Feng Q. C.; Wang C. Y.; Yang N.; Ma H. N.; Ma J. J.; Russell A. G.; He H. Air pollutant correlations in China: secondary air pollutant responses to NOx and SO2 control. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett 2020, 7, 695–700. 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P. J.; Tang X. G.; He Z. H.; Liu Y. X.; Wang Z. H. Alkali metal poisoning and regeneration of selective catalytic reduction denitration catalysts: recent advances and future perspectives. Energy Fuels 2022, 36 (11), 5622–5646. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c01036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granger P.; Parvulescu V. I. Catalytic NOx abatement systems for mobile sources: from three-way to lean burn after-treatment technologies. Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 3155–3207. 10.1021/cr100168g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvulescu V. I.; Grange P.; Delmon B. Catalytic removal of NO. Catal. Today 1998, 46, 233–316. 10.1016/S0920-5861(98)00399-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G.; Shan W.; Yu Y.; Shan Y.; Wu X.; Wu Y.; Zhang S.; He L.; Shuai S.; Pang H.; Jiang X.; Zhang H.; Guo L.; Wang S.; Xiao F.-S.; Meng X.; Wu F.; Yao D.; Ding Y.; Yin H.; He H. Advances in emission control of diesel vehicles in China. J. Environ. Sci 2023, 123, 15–29. 10.1016/j.jes.2021.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian Z. H.; Li Y. J.; Shan W. P.; He H. Recent progress on improving low-temperature activity of vanadia-based catalysts for the selective catalytic reduction of NOx with ammonia. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1421. 10.3390/catal10121421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Liu J.; Jin Z. S.; Guo S. Q.; Cheng D. H.; Deng J.; Zhang D. S. Gas-phase regeneration of metal-poisoned V2O5-WO3/TiO2 NH3-SCR catalysts via a masking and reconstruction strategy. Environ. Sci. Technol 2024, 58 (30), 13574–13584. 10.1021/acs.est.4c05260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak J. H.; Tonkyn R. G.; Kim D. H.; Szanyi J.; Peden C. H. F. Excellent activity and selectivity of Cu-SSZ-13 in the selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3. J. Catal 2010, 275, 187–190. 10.1016/j.jcat.2010.07.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beale A. M.; Gao F.; Lezcano-Gonzalez I.; Peden C. H. F.; Szanyi J. Recent advances in automotive catalysis for NOx emission control by small-pore microporous materials. Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44, 7371–7405. 10.1039/C5CS00108K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busca G.; Lietti L.; Ramis G.; Berti F. Chemical and mechanistic aspects of the selective catalytic reduction of NOx by ammonia over oxide catalysts: a review. Appl. Catal., B 1998, 18, 1–36. 10.1016/S0926-3373(98)00040-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J. K.; Wachs I. E. A perspective on the selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NO with NH3 by supported V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalysts. ACS Catal 2018, 8, 6537–6551. 10.1021/acscatal.8b01357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han L.; Cai S.; Gao M.; Hasegawa J. Y.; Wang P.; Zhang J.; Shi L.; Zhang D. Selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3 by using novel catalysts: state of the art and future prospects. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 10916–10976. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan W. P.; Yu Y. B.; Zhang Y.; He G. Z.; Peng Y.; Li J. H.; He H. Theory and practice of metal oxide catalyst design for the selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3. Catal. Today 2021, 376, 292–301. 10.1016/j.cattod.2020.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Y. Y.; Ford M. E.; Zhu M. H.; Liu Q. C.; Tumuluri U.; Wu Z. L.; Wachs I. E. Influence of catalyst synthesis method on selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NO by NH3 with V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalysts. Appl. Catal., B 2016, 193, 141–150. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. D.; Chen J. J.; Chen X. P.; Yin R. Q.; Li K. Z.; Li J. H. Monolith or powder: improper sample pretreatment may mislead the understanding of industrial V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalysts operated in stationary resources. Environ. Sci. Technol 2022, 56 (22), 16394–16399. 10.1021/acs.est.2c05022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. I.; Choi Y. J.; Lee M. S.; Lee D. H. Nitration-promoted vanadate catalysts for low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3. ACS Omega 2023, 8 (37), 34152–34159. 10.1021/acsomega.3c05423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. P.; Yang R. T. Role of WO3 in mixed V2O5-WO3/TIO2 catalysis for selective catalytic reduciton of nitric-oxide with ammonia. Appl. Catal., A 1992, 80, 135–148. 10.1016/0926-860X(92)85113-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaegers N. R.; Lai J. K.; He Y.; Walter E.; Dixon D. A.; Vasiliu M.; Chen Y.; Wang C. M.; Hu M. Y.; Mueller K. T.; Wachs I. E.; Wang Y.; Hu J. Z. Mechanism by which tungsten oxide promotes the activity of supported V2O5/TiO2 catalysts for NOx abatement: structural effects revealed by V51 MAS NMR spectroscopy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 12609–12616. 10.1002/anie.201904503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata Y.; Kubota H.; Hata S.; Kiyonaga E.; Morita K.; Yoshida K.; Sakaguchi N.; Toyao T.; Shimizu K.-I.; Ishikawa S.; Ueda W.; Haruta M.; Murayama T. Bulk tungsten-substituted vanadium oxide for low-temperature NOx removal in the presence of water. Nat. Commun 2021, 12 (1), 557. 10.1038/s41467-020-20867-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Yi W.; Zeng Y. J.; Chang H. Z. Novel methods for assessing the SO2 poisoning effect and thermal regeneration possibility of MOx-WO3/TiO2 (M = Fe, Mn, Cu, and V) catalysts for NH3-SCR. Environ. Sci. Technol 2020, 54, 12612–12620. 10.1021/acs.est.0c02840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Du X.; Liu S.; Yang G.; Chen Y.; Zhang L.; Tu X. Understanding the deposition and reaction mechanism of ammonium bisulfate on a vanadia SCR catalyst: a combined DFT and experimental study. Appl. Catal., B 2020, 260, 118168. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marberger A.; Elsener M.; Nuguid R. J. G.; Ferri D.; Krocher O. Thermal activation and aging of a V2O3/WO3-TiO2 catalyst for the selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3. Appl. Catal., A 2019, 573, 64–72. 10.1016/j.apcata.2019.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L. W.; Wang C. Z.; Chang H. Z.; Wu Q. R.; Zhang T.; Li J. H. New Insight into SO2 poisoning and regeneration of CeO2-WO3/TiO2 and V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalysts for low-temperature NH3-SCR. Environ. Sci. Technol 2018, 52, 7064–7071. 10.1021/acs.est.8b01990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W.; Wu X.; Si Z.; Weng D. Influences of impregnation procedure on the SCR activity and alkali resistance of V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci 2013, 283, 209–214. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.06.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M.; Lai J.-K.; Tumuluri U.; Wu Z.; Wachs I. E. Nature of active sites and surface intermediates during SCR of NO with NH3 by supported V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (44), 15624–15627. 10.1021/jacs.7b09646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marberger A.; Ferri D.; Elsener M.; Krocher O. The significance of Lewis acid sites for the selective catalytic reduction of nitric oxide on vanadium-based catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55 (39), 11989–11994. 10.1002/anie.201605397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G.; Lian Z.; Yu Y.; Yang Y.; Liu K.; Shi X.; Yan Z.; Shan W.; He H. Polymeric vanadyl species determine the low-temperature activity of V-based catalysts for the SCR of NOx with NH3. Sci. Adv 2018, 4 (11), eaau4637 10.1126/sciadv.aau4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topsoe N.-Y. Mechanism of the Selective Catalytic Reduction of Nitric Oxide by Ammonia Elucidated by in Situ On-Line Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Science 1994, 265 (5176), 1217–1219. 10.1126/science.265.5176.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuguid R. J. G.; Ferri D.; Marberger A.; Nachtegaal M.; Krocher O. Modulated excitation Raman spectroscopy of V2O5/TiO2: mechanistic insights into the selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3. ACS Catal 2019, 9 (8), 6814–6820. 10.1021/acscatal.9b01514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnarson L.; Falsig H.; Rasmussen S. B.; Lauritsen J. V.; Moses P. G. A complete reaction mechanism for standard and fast selective catalytic reduction of nitrogen oxides on low coverage VOx/TiO2(001) catalysts. J. Catal 2017, 346, 188–197. 10.1016/j.jcat.2016.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H. C.; Chen Y.; Zhao Z.; Wei Y. C.; Liu Z. C.; Zhai D.; Liu B. J.; Xu C. M. Periodic DFT study on mechanism of selective catalytic reduction of NO via NH3 and O2 over the V2O5 (001) surface: competitive sites and pathways. J. Catal 2013, 305, 67–75. 10.1016/j.jcat.2013.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M. M.; Lee Z. R.; Vasiliu M.; Wachs I. E.; Dixon D. A. Initial steps in the selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 by TiO2-supported vanadium oxides. ACS Catal 2020, 10 (23), 13918–13931. 10.1021/acscatal.0c03693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M.; Lai J. K.; Tumuluri U.; Ford M. E.; Wu Z.; Wachs I. E. Reaction pathways and kinetics for selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of acidic NOx emissions from power plants with NH3. ACS Catal 2017, 7 (12), 8358–8361. 10.1021/acscatal.7b03149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ek M.; Ramasse Q. M.; Arnarson L.; Moses P. G.; Helveg S. Visualizing atomic-scale redox dynamics in vanadium oxide-based catalysts. Nat. Commun 2017, 8 (1), 305. 10.1038/s41467-017-00385-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godiksen A. L.; Rasmussen S. B. Identifying the presence of [V = O]2+ during SCR using in-situ Raman and UV Vis spectroscopy. Catal. Today 2019, 336, 45–49. 10.1016/j.cattod.2019.02.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doronkin D. E.; Benzi F.; Zheng L.; Sharapa D. I.; Amidani L.; Studt F.; Roesky P. W.; Casapu M.; Deutschmann O.; Grunwaldt J.-D. NH3-SCR over V–W/TiO2 investigated by operando X-ray absorption and emission spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 14338–14349. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b00804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnarson L.; Falsig H.; Rasmussen S. B.; Lauritsen J. V.; Moses P. G. The reaction mechanism for the SCR process on monomer V5+ sites and the effect of modified Brønsted acidity. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2016, 18 (25), 17071–17080. 10.1039/C6CP02274J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnarson L.; Rasmussen S. B.; Falsig H.; Lauritsen J. V.; Moses P. G. Coexistence of square pyramidal structures of Oxo vanadium (+5) and (+4) species over low-coverage VOx/TiO2 (101) and (001) anatase catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119 (41), 23445–23452. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b06132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Y.; Miao J. F.; Huang B. Y.; Chen Y. T.; Chen J. S.; Wang J. X. Effect of carious acid anions on potassium poisoning and the mechanism of commercial V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalysts for SCR of NOx. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 2024, 63 (5), 2167–2176. 10.1021/acs.iecr.3c03785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G.; Li H.; Yu Y.; He H. Dynamic change of active sites of supported vanadia catalysts for selective catalytic reduction of nitrogen oxides. Environ. Sci. Technol 2022, 56 (6), 3710–3718. 10.1021/acs.est.1c07739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X.; Xiong S.; Li B.; Geng Y.; Yang S. Role of WO3 in NO reduction with NH3 over V2O5-WO3/TiO2: a new insight from the kinetic study. Catal. Lett 2016, 146 (11), 2242–2251. 10.1007/s10562-016-1852-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Ford M. E.; Zhu M.; Liu Q.; Wu Z.; Wachs I. E. Selective catalytic reduction of NO by NH3 with WO3-TiO2 catalysts: influence of catalyst synthesis method. Appl. Catal., B 2016, 188, 123–133. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.01.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Yang S.; Chang H.; Peng Y.; Li J. Dispersion of tungsten oxide on SCR performance of V2O5-WO3/TiO2: Acidity, surface species and catalytic activity. Chem. Eng. J 2013, 225, 520–527. 10.1016/j.cej.2013.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kompio P.; Bruckner A.; Hipler F.; Auer G.; Loffler E.; Grunert W. A new view on the relations between tungsten and vanadium in V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalysts for the selective reduction of NO with NH3. J. Catal 2012, 286, 237–247. 10.1016/j.jcat.2011.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G.; Ma J.; Wang L.; Lv Z.; Wang S.; Yu Y.; He H. Mechanism of the H2 effect on NH3-selective catalytic reduction over Ag/Al2O3: kinetic and diffuse reflectance infrared fourier transform spectroscopy studies. ACS Catal 2019, 9 (11), 10489–10498. 10.1021/acscatal.9b04100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G. Y.; Zhang Y.; Lin J. G.; Wang Y. B.; Shi X. Y.; Yu Y. B.; He H. Unraveling the mechanism of ammonia selective catalytic oxidation on Ag/Al2O3 catalysts by operando spectroscopy. ACS Catal 2021, 11 (9), 5506–5516. 10.1021/acscatal.1c01054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G.; Wang H.; Yu Y.; He H. Role of silver species in H2-NH3-SCR of NOx over Ag/Al2O3 catalysts: operando spectroscopy and DFT calculations. J. Catal 2021, 395, 1–9. 10.1016/j.jcat.2020.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M. H.; Lai J. K.; Tumuluri U.; Wu Z. L.; Wachs I. E. Nature of active sites and surface intermediates during SCR of NO with NH3 by supported V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (44), 15624–15627. 10.1021/jacs.7b09646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G. Y.; Ma J. Z.; Wang L.; Xie W.; Liu J. J.; Yu Y. B.; He H. Insight into the origin of sulfur tolerance of Ag/Al2O3 in the H2-C3H6-SCR of NOx. Appl. Catal., B 2019, 244, 909–918. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.11.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillot S.; Tricot G.; Vezin H.; Dacquin J. P.; Dujardin C.; Granger P. Induced effect of tungsten incorporation on the catalytic properties of CeVO4 systems for the selective reduction of NOx by ammonia. Appl. Catal., B 2018, 234, 318–328. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.04.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Z.; He G. Z.; Ge Y. L.; Liu Y. C.; Yu Y. B.; He H. Effects of WO3 and MoO3 loadings on vanadia-based catalysts for NH3-SCR: revealed by infrared and two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy. Fuel 2024, 359, 130472. 10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L. W.; Wang C. Z.; Chang H. Z.; Wu Q. R.; Zhang T.; Li J. H. New insight into SO2 poisoning and regeneration of CeO2-WO3/TiO2 and V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalysts for low-temperature NH3-SCR. Environ. Sci. Technol 2018, 52 (12), 7064–7071. 10.1021/acs.est.8b01990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topsoe N. Y.; Dumesic J. A.; Topsoe H. Vanadia-titania catalysis for selecitve catalytic reduction of nitric-oxide by ammonia. 2. Studies of active-sites and formulation of catalytic cycles. J. Catal 1995, 151 (1), 241–252. 10.1006/jcat.1995.1025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron M.; Abbott H.; Bondarchuk O.; Stacchiola D.; Uhl A.; Shaikhutdinov S.; Freund H. J.; Popa C.; Ganduglia-Pirovano M. V.; Sauer J. Resolving the atomic structure of vanadia monolayer catalysts: monomers, trimers, and oligomers on ceria. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2009, 48 (43), 8006–8009. 10.1002/anie.200903085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magg N.; Immaraporn B.; Giorgi J. B.; Schroeder T.; Bäumer M.; Döbler J.; Wu Z. L.; Kondratenko E.; Cherian M.; Baerns M.; Stair P. C.; Sauer J.; Freund H. J. Vibrational spectra of alumina- and silica-supported vanadia revisited: An experimental and theoretical model catalyst study. J. Catal 2004, 226, 88–100. 10.1016/j.jcat.2004.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska A. E.; Calatayud M.; Tielens F.; Banares M. A. Hydration dynamics for vanadia/titania catalysts at high loading: a combined theoretical and experimental study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117 (48), 25535–25544. 10.1021/jp408836d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska A. E.; Calatayud M.; Tielens F.; Banares M. A. Dynamics of hydration in vanadia-titania catalysts at low loading: a theoretical and experimental study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115 (49), 24133–24142. 10.1021/jp204726b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen S. B.; Portela R.; Bazin P.; Avila P.; Banares M. A.; Daturi M. Transient operando study on the NH3/NH4+ interplay in V-SCR monolithic catalysts. Appl. Catal., B 2018, 224, 109–115. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.10.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R.; Li L.; Zhang N.; He J.; Song L.; Zhang G.; Zhang Z.; He H. Enhancement of low-temperature NH3-SCR catalytic activity and H2O & SO2 resistance over commercial V2O5-MoO3/TiO2 catalyst by high shear-induced doping of expanded graphite. Catal. Today 2021, 376, 302–310. 10.1016/j.cattod.2020.04.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lian Z.; Deng H.; Xin S.; Shan W.; Wang Q.; Xu J.; He H. Significant promotion effect of the rutile phase on V2O5/TiO2 catalysts for NH3-SCR. Chem. Commun 2021, 57 (3), 355–358. 10.1039/D0CC05938B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.