Abstract

Bradykinin is a major mediator of swelling in C1 inhibitor deficiency as well as the angioedema seen with ACE inhibitors and may contribute to bronchial hyperreactivity in asthma. Formation of bradykinin occurs in the fluid phase and along cell surfaces requiring interaction of factor XII, prekallikrein, and high Mr kininogen (HK). Recent data suggest that activation of the kinin-forming cascade can occur on the surface of endothelial cells, even in the absence of factor XII. We sought to further define this factor XII-independent mechanism of kinin formation. Both cytosolic and membrane fractions from endothelial cells possessed the ability to catalyze prekallikrein conversion to kallikrein, and activation depended on the presence of HK and zinc ion. We fractionated the cytosol by ion exchange chromatography and affinity chromatography by using corn trypsin inhibitor as ligand. The fractions with peak activity were subjected to SDS gel electrophoresis and ligand blot with biotinylated corn trypsin inhibitor, and positive bands were sequenced. Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) was identified as the protein responsible for zinc-dependent prekallikrein activation in the presence of HK. Zinc-dependent activation of the prekallikrein-HK complex also depended on addition of either α and β isoforms of Hsp90 and the activation on endothelial cells was inhibited on addition of polyclonal Ab to Hsp90 in a dose-dependent manner. Although the mechanism by which Hsp90 activates the kinin-forming cascade is not understood, this protein represents the cellular contribution to the reaction and may become the dominant mechanism in pathologic circumstances in which Hsp90 is highly expressed or secreted.

Activation of the plasma bradykinin-forming cascade requires the interaction of factor XII (Hageman Factor), prekallikrein, and high Mr kininogen (HK), with negatively charged inorganic surfaces (glass, kaolin, and dextran sulfate), or macromolecules with biological properties (lipopolysaccharide and amyloid β). Activation can also occur by interaction of these molecules with cell surfaces. In plasma, HK circulates as a complex with either prekallikrein or factor XI (1–4). Prekallikrein binding to HK serves to promote surface-dependent activation of the zymogen and to position HK for efficient cleavage by kallikrein once it is formed (5). Platelets and endothelial cells express binding sites for HK and factor XII (6–13) and cell-dependent activation requires zinc-dependent binding of HK and factor XII to the cell surface. Once bound to the cell surface, factor XII slowly autoactivates (14, 15) whereas HK functions as a cofactor for the factor XIIa-dependent conversion of prekallikrein to kallikrein (16–18). Kallikrein then digests HK to liberate the vasoactive peptide bradykinin (19).

Activation of the plasma bradykinin-forming cascade can also proceed on endothelial cells in the absence of factor XII (20, 21). This reaction requires prekallikrein, HK, and zinc ion. When the HK-prekallikrein complex is bound to the surface, prekallikrein is converted to kallikrein and HK is then cleaved to generate bradykinin (20, 21). But the identity of the prekallikrein activator in the factor XII-independent system is not known. We have approached this problem by first determining whether this prekallikrein activator exists in the cells, either in the cytosol or on the cell membrane, and then purifying and identifying the activator by using a cell-free activation assay. In this manuscript, we demonstrate that such a factor is present in the cytosol with the same activation requirements as is observed with whole cells. We further characterized this activating factor by partial purification and amino acid sequence analysis. Immunochemical and partial sequence analyses identified this factor to be heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90). In contradistinction to prekallikrein activation by factor XIIa, the effect of Hsp90 requires both HK and zinc ion and Ab to Hsp90 inhibits factor XII-independent activation of the kinin-forming cascade.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Human plasma proteins, HK, prekallikrein, kallikrein, and factor XII were purchased from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN). Before storage they were treated with 0.1 mM (4-amidinophenyl)-methanesulfonylfluoride (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and stored in 4 mM sodium acetate buffer containing 0.15 M NaCl (pH 5.5) at −70°C. Synthetic substrate H-d-prolyl-d-phenylalanyl-d-arginine p-nitrophenylester (S-2302) was purchased from Kabi Pharmacia Hesper (Franklin, OH). Purified Hsp90, recombinant Hsp90α, and recombinant Hsp90β were purchased from Calbiochem. Protease inhibitors and other reagents were obtained from Sigma. Polyclonal Ab to Hsp90 was purchased from Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO).

Endothelial Cell Culture.

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) were isolated as described earlier (22) and cultured in gelatin-coated dishes in endothelial growth medium (EGM Bullet kit, Clonetics, San Diego). For prekallikrien activation assays, the cells were subcultured into gelatin-coated 96-well plates in 0.2 ml of culture medium. The cells were identified as endothelial cells by their distinct cobblestone morphology and interaction with antiserum to von Willebrand's Factor (23). All of the cells were used at the third cell passage.

Preparation of Affinity Column.

Purified corn trypsin inhibitor (CTI, Enzyme Research Laboratories) was coupled to Ultralink Biosupport medium (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. In brief, 10 mg of CTI was dissolved in 6 ml of 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.0), and sodium citrate was added to a final concentration of 0.6 M. To this, 0.25 g of dry beads were added and mixed for 2 h at room temperature. This mixture was poured into a column and washed with 10 vol of PBS. The eluate and the washings were collected to determine the coupling efficiency, which was calculated to be 65%. Then 6 ml of ethanolamine (pH 9.0) was added to the column and mixed end-over-end for 2.5 h at room temperature. The column was then washed sequentially with 10 vol each of PBS, 1 M NaCl, and PBS.

Cell Isolation and Preparation of Cytosolic (S100) Extracts.

The confluent HUVEC monolayers were washed three times with cold Hepes-buffered saline (HBS, pH 7.4), and the cells were gently scraped into HBS on ice by using a Teflon spatula. The cells were collected gently by low-speed (1,000 × g) centrifugation, resuspended in HBS transferred to a polypropylene ultracentrifuge tube, and collected again by centrifugation. The HBS was aspirated completely from the cell pellet. The cells were then subjected to ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g) for 90 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant fraction was transferred to Eppendorf tubes and stored at −80°C until use.

Biotinylation of Proteins.

Biotinylation of CTI was performed by using NHS-LC-biotin (Pierce) according to the following procedure. CTI (1 mg in 500 μl) were first dialyzed against 0.2 M NaHCO3 buffer (pH 8.3). Labeling was initiated by addition of freshly prepared biotin in dimethyl sulfoxide. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 4 h at room temperature with constant but gentle mixing. After the incubation, the protein was dialyzed against PBS. Biotinylation was verified by ELISA using wells coated with various dilutions of the labeled protein and probing with alkaline phosphatase conjugated avidin or streptavidin.

Purification of CTI-Binding Proteins.

The CTI affinity column was equilibrated with HBS containing 50 μM zinc chloride. The S100 fraction was loaded onto the column and incubated for 1 h with end-over-end mixing. After incubation the flow through was collected and saved for later analysis. The column was washed with 10 vol of HBS followed by 10 vol of 0.25 M NaCl. The washings were also collected and saved. The bound proteins were eluted with 0.5 M NaCl, and 0.5-ml fractions were collected. The fractions from all of the steps were assayed for prekallikrein-activating ability as described below.

Electrophoresis and Ligand Blot Analysis.

Samples were prepared in Laemmli (24) buffer and loaded on to a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel (5% stack) and subjected to gel electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, the gels were either stained or transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and were probed with biotinylated ligand. Bound probes were visualized by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated Avidin.

Protein Determination.

Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (25) by using human IgG as reference protein.

Prekallikrein Activation Assays.

Assays were performed in Hepes buffer (10 mM Hepes/137 mM NaCl/4 mM KCl/11 mM d-glucose/0.5 mg/ml RIA grade BSA, pH 7.4), with a kallikrein-specific substrate (0.6 mM S2302). For assays using the cell-free system, 96-well disposable polystyrene microtiter plates (Dynatech) were used. These microtiter plates were pretreated with 1% polyethylene glycol (Aquacide III, Calbiochem) in HBS for 2 h to prevent adsorption of proteins to polystyrene. The absorbance (OD at 405 nm) was monitored at room temperature on a Molecular Devices THERMOmax microplate reader. Just before the assay, all of the proteins were treated with 2.0 mM (4-amidinophenyl)-methanesulfonylfluoride for 15 min at pH 5.5, after which they were diluted 1:100 with HBS and incubated for 45 min to allow for the decomposition of any unreacted (4-amidinophenyl)-methanesulfonylfluoride at the neutral pH. The inhibition profile (Table 1) for prekallikrein activation was determined by adding each inhibitors to the cytosolic extract. The mixture was immediately incubated with prekallikrein (20 nM), HK (20 nM), and S2302 (0.6 mM) in the presence of 50 μM zinc ion, and the chromogenic activity was monitored at 405 nm.

Table 1.

Inhibition profile of prekallikrein activation

| Inhibitors | Concentration | % Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| Antipain | 100 μM | 98.6 |

| Aprotinin | 100 μM | 96.4 |

| Captopril | 10 mM | 97.9 |

| Corn trypsin inhibitor | 10 μM | 94.3 |

| Cystatin | 10 μg/ml | 4.5 |

| Cysteine | 10 mM | 59.6 |

| DTT | 10 mM | 69.1 |

| EDTA | 20 mM | 85.4 |

| Glutathione | 100 μM | 18.6 |

| HgCl2 | 1 mM | 98 |

| Iodoacetamide | 10 mM | 7 |

| LBTI | 50 μg/ml | 0 |

| Mercaptoethanol | 5% | 85.5 |

| PMSF | 2 mM | 5 |

| SBTI | 50 μg/ml | 98.6 |

Results

Activation of Prekallikrein.

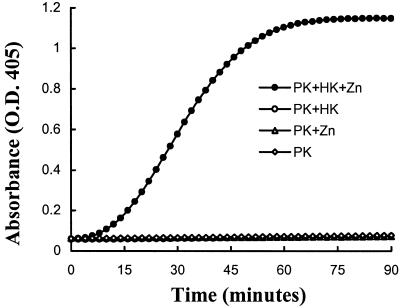

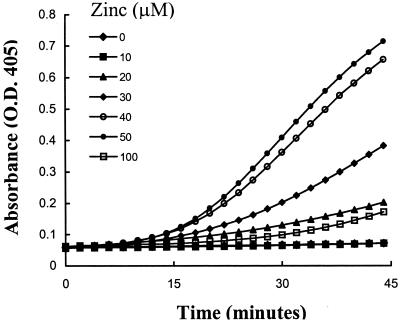

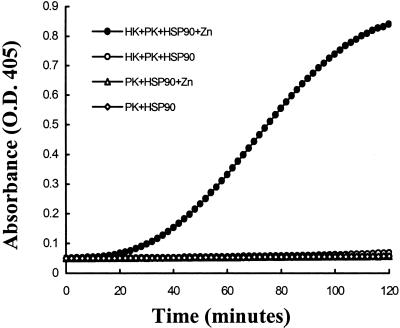

Studies were performed to determine whether prekallikrein alone could be activated on the surface of HUVEC. Prekallikrein was not activated in the absence of other contact proteins, suggesting that HUVEC did not secrete or express factor XIIa or kallikrein activities. However, when HUVEC were incubated with HK and prekallikrein together in the presence of zinc, chromogenic activity was detected indicating progressive conversion of prekallikrein to kallikrein (Fig. 1). There was no activation if either HK or zinc is omitted. We next determined the optimum concentration of zinc by using the cell-free system with the cytosolic extract as the activator in HBS-BSA buffer. The optimum concentration of zinc was found to be 50 μM (Fig. 2) and increasing the concentration to 100 μM was inhibitory. In the absence of zinc, there was no detectable activity. Thus for all subsequent experiments zinc was used at a concentration of 50 μM.

Figure 1.

Prekallikrein activation on endothelial cells. Endothelial cells were incubated with prekallikrein (20 nM) alone or prekallikrein (20 nM) and HK (20 nM) in the presence and absence of 50 μM zinc as indicated. Kallikrein activity was measured by using a synthetic substrate (S2302; 0.6 mM). This experiment was performed six times with identical results. A representative experiment is shown here.

Figure 2.

Effect of zinc on prekallikrein activation. Prekallikrein (20 nM), HK (20 nM), S2302 (0.6 mM), and cytosolic fraction (20 μg of total protein) were incubated with varying concentrations of zinc as indicated. The rate of conversion of prekallikrein to kallikrein was monitored at 405 nm. This experiment was repeated four times, each with maximal activity at 50 μM.

Addition of factor XII along with HK and prekallikrein augmented the activation such that maximal activity was seen in 15 min rather than 45 min (data not shown). Because factor XII-independent prekallikrein activation was not observed in the absence of HUVEC, we considered the possibility that an alternative prekallikrein activator is present either on the surface of HUVEC or secreted by the cells. To determine whether the prekallikrein activator was membrane bound or intracellular, the activation assay was performed in a cell-free system by using cytosolic extract or membrane fraction as activators. Both, cytosolic extract and the membrane fraction activated the system to a similar extent and in each instance activation was observed only in the presence of both HK and zinc. We chose to purify and identify the activating factor from the cytosolic extract.

Effect of HK.

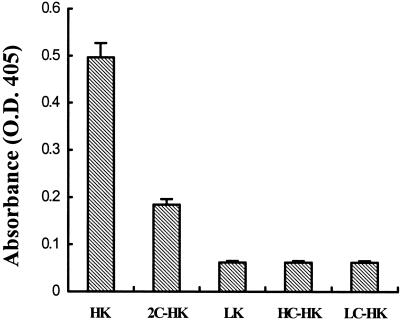

To determine whether heavy or light chain of HK is required as a cofactor for prekallikrein activation, we tested low Mr kininogen (has the identical heavy chain), purified light chain, heavy chain, and cleaved HK at equimolar concentrations. There was no effect of low Mr kininogen, heavy chain, or light chain at any dose tested, and cleaved HK was not as effective as the single chain precursor (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of HK on prekallikrein activation. Cytosol (20 μg) was incubated with 20 nM of either HK, low Mr kininogen (LK), cleaved HK (2C-HK), purified heavy chain of HK (HC-HK), or light chain of HK (LC-HK) in the presence of 20 nM prekallikrein, 50 μM zinc, and 0.6 mM S2302. After 2 h the chromogenic activity was measured at 405 nm.

Inhibition of Prekallikrein Activation.

Inhibitors such as antipain, aprotinin, captopril, CTI, cystatin, cysteine, DTT, EDTA, glutathione, HgCl2, iodoacetamide, lima bean trypsin inhibitor, mercaptoethanol, PMSF, and soybean trypsin inhibitor were tested to identify an inhibitor of the prekallikrein-activating factor. Antipain, aprotinin, captopril, CTI, EDTA, mercaptoethanol, and soy bean trypsin inhibitor were good inhibitors as shown in Table 1. However, aprotinin and SBTI inhibit the kallikrein generated, whereas the other inhibitors do not. Inhibition by antipain and mercaptoethanol suggest that a cysteine protease may be present, as reported (20). However inhibition by CTI suggests a factor XIIa-like serine protease whereas inhibition by captopril and EDTA suggests either a metalloproteinase or they may be chelating-free zinc and thereby prevent prekallikrein activation. The nature of the protease is not clearly identified by this analysis and more than one factor might be present.

Purification of the Prekallikrein-Activating Factor.

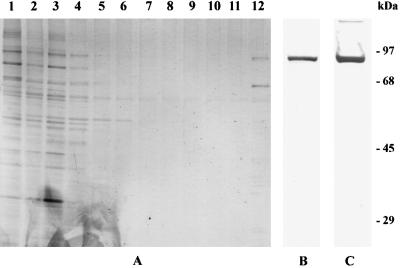

When cytosol was passed over SP Sepharose equilibrated with HBS, all of the activity was present in the effluent, suggesting a negatively charged activator. Alternately, when cytosol was passed over Q Sepharose, all of the activity bound and remained in the Sepharose after washing with buffer containing 0.25 M NaCl. Most of the activity was eluted with 0.5 M NaCl. Although a sequential chromatographic procedure was envisioned, we also attempted to isolate the factor by CTI affinity chromatography (see Materials and Methods). The activity was retained on the column as applied and was eluted with 0.5 M NaCl in Hepes buffer. The eluted fractions were dialyzed in HBS and assayed. Fig. 4A is a silver-stained gel showing the protein pattern of fractions eluted from the column. The proteins eluted with 0.5 M NaCl are in lane 12, which has two prominent bands at 90 kDa and 65 kDa. A ligand blot using biotinylated CTI of the 0.5 M NaCl eluted fraction interacted with the 90-kDa band (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

SDS/PAGE analysis of proteins eluted from CTI affinity column. Fractions collected from CTI affinity column were subjected to SDS/PAGE analysis. (A) After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with silver stain showing the starting material in lane 1, effluent in lane 2, washes with 0.25 M NaCl in lanes 3–11, and the final eluate with 0.5 M NaCl in lane 12. (B) Ligand blot of the final eluate with 0.5 M NaCl (lane 12 of A) with biotinylated CTI. (C) Western blot of 0.5 M NaCl eluate fraction with polyclonal Ab to Hsp90.

Amino Acid Sequence Analysis and Identification of the Isolated Proteins.

Proteins separated by SDS/PAGE were transferred to immobilonPSQ membranes and stained with Coomassie blue stain. Individual bands were cut out and sequenced after digestion to obtain an internal peptide. Sequence analysis was done by Midwest Analytical (St. Louis). A sequence of 12 aa (EEVHHGEEEVE) obtained from the analysis of the 90-kDa band matched residues 2–13 of Hsp90 and the 65-kDa band corresponded to calreticulin with an internal sequence of EPAVYFKEQFL. Western blot analysis by using Ab to Hsp90 confirmed the identity of the 90-kDa band (Fig. 4C).

Prekallikrein Activation Using Purified Hsp90.

We then tested purified Hsp90 and calreticulin as a prekallikrein activator and as shown in Fig. 5; Hsp90 was functionally indistinguishable from the cytosolic extract. The activation was HK- and zinc-dependent and was inhibited by CTI. Calreticulin did not activate the system.

Figure 5.

Prekallikrein activation on Hsp90. Purified Hsp90 (2 μg) was incubated with prekallikrein (20 nM), HK (20 nM), zinc (50 μM), and S2302 (0.6 mM), and chromogenic activity was monitored. Controls were either in the absence of zinc or HK or both.

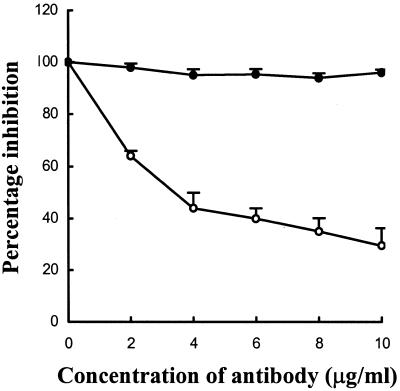

Inhibition of Prekallikrein Activation with Ab to Hsp90.

We then used polyclonal Ab to Hsp90 to determine whether it will inhibit factor XII-independent conversion of prekallikrein to kallikrein by using endothelial cells as a source of the prekallikrein activator. As shown in Fig. 6, there was dose-dependent inhibition of prekallikrein activation with Ab to Hsp90 as compared to a nonimmune rabbit IgG control.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of prekallikrein activation by using Ab to Hsp90. Endothelial cells were preincubated with polyclonal Ab to Hsp90 (○) or nonimmune rabbit IgG (●) and assayed for prekallikrein activation.

Discussion

The proteins of the contact activation cascade namely, HK, factor XII, prekallikrein, and factor XI, have been shown to assemble along the surface of cells, including platelets (6–8), endothelial cells (9–13), and neutrophils (26). We have focused on the endothelial cell because it is a major site of action for bradykinin. Two mechanisms of activation of the bradykinin-forming cascade along the surface of vascular endothelial cells have been reported. First is the classical mechanism of contact activation in which factor XII autoactivates on binding to the cell surface proteins (14, 15) and the activated factor XII converts prekallikrein to kallikrein whereas HK functions as a cofactor (16–18). Kallikrein then digests HK to liberate bradykinin (19). The second mechanism is an alternate pathway in which activation of the cascade on endothelial cells can proceed in the absence of factor XII (20, 21). It has been reported that interaction of endothelial cells with HK leads to the expression of a cysteine protease, which activates prekallikrein in the absence of factor XII (20, 21). The inhibition profile we observe (Table 1) does not, however, allow clear classification of this enzymatic activity although we agree that cysteine protease inhibitors such as DTT and antipain are effective. A sulfhydryl protease is suggested unless these agents also sequester zinc ion. Inhibition by CTI, however, suggests a serine protease, perhaps one containing a critical sulfhydryl or disulfide bond. Inhibition by metalloproteases is expected because zinc is required when cytosol or purified Hsp90 is tested. Thus the effect of zinc ion is independent of the zinc requirement for binding HK to the cell surface (6–13).

The major finding of the present study is the identification of Hsp90 as a protein factor that can catalyze the conversion of prekallikrein to kallikrein on endothelial cells. The results also suggest that the substrate is the prekallikrein-HK complex rather than prekallikrein. HK possesses zinc-binding sites that may cause conformational changes to HK (27, 28) and the role of zinc may be related to this requirement. It is not known whether zinc can interact with Hsp90. It appears that the role of HK is complex and multifaceted because the isolated light chain of HK binds to prekallikrein equally well as does intact HK but is ineffective in activating this system. Heavy chain also was inactive, but cleaved HK, lacking the bradykinin moiety will allow prekallikrein activation to proceed although much less effectively than the intact HK. This cell-free assay facilitated identification of the activating factor from the cytosol by using affinity chromatography using CTI as ligand. The 90-kDa band was the major protein that interacted with CTI, and amino acid sequence analysis identified this protein to be Hsp90. Addition of Hsp90 to a mixture of HK and prekallikrein in zinc containing buffer reproduced the factor XII-independent activity present in endothelial cell-derived cytosol. Furthermore, Ab to Hsp90 inhibited activation seen on incubation of endothelial cells with HK, prekallikrein, and zinc. It should be noted that Hsp90 is a generic term used to describe two isoforms whose actual Mrs are 86 and 84 kDa termed Hsp90 α and β. The amino acid sequence we obtained corresponded to the β isoform; however α and β, when tested separately, showed identical activities (data not shown).

Heat shock proteins are a family of cellular proteins characterized by their up-regulation in response to stress and the presence of a weak ATPase activity (29). They were initially described as chaperones that facilitate the folding of other proteins. However, recent studies (30–34) indicate that heat shock proteins also play a role in cytoprotection, anti-apoptosis, and signal transduction. Hsp90 is constitutively expressed in the cytoplasm of cells, and it has been shown to be secreted from cells in response to stress (35). Hsp90 also stimulated extracellular response kinase one and two activity in vascular smooth muscle cells (35).

Our data do not allow us to determine which component in this mixture contains the active site(s) concerned with prekallikrein activation. Hsp90 is not known to possess proteolytic activity although binding to CTI suggests that it might. HK is not only the substrate from which bradykinin is cleaved, but it also has cysteine protease inhibitory activity in two of its domains (36–38), and it is conceivable that it has enzymatic activity if Hsp90 interacts with it. A third possibility is that a complex of Hsp90 and HK with prekallikrein exposes a site within prekallikrein, analogous to the site in plasminogen on interaction with streptokinase (39, 40), before cleavage.

It has been proposed that this factor XII-independent activation pathway is the true vascular initiator of bradykinin formation (20, 21) and that the marked augmentation on addition of factor XII (which is always present except for factor XII-deficient patients) depends on activation of factor XII by the kallikrein generated (20, 21). This was supported by the inability of factor XII to autoactivate on cell surfaces. Our earlier data are not, however, in agreement with this conclusion. We have reported activation in plasma that is strictly factor XII-dependent and that one factor XII and HK-binding protein, namely gC1qR, catalyzes factor XII autoactivation (41). Heparan sulfate that is present along the cell surface (42) would behave similarly. Nevertheless, this alternate mechanism may be operative in pathologic circumstances in which Hsp90 is highly expressed or secreted, and we view it as an alternate mechanism of activation rather than an exclusive one. Conditions causing cell stress such as hypoxia, or conversely, exposure to oxidants, or stimulation by inflammatory cytokines are examples of such processes.

Abbreviations

- HK

high Mr kininogen

- Hsp90

heat shock protein 90

- CTI

corn trypsin inhibitor

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- HBS

Hepes-buffered saline

References

- 1.Bock P E, Shore J D. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:15079–15086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock P E, Shore J D, Tans G, Griffin J H. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:12434–12443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandle R, Jr, Colman R W, Kaplan A P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:4179–4183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.4179. .R. J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson R E, Mandle R, Jr, Kaplan A P. J Clin Invest. 1977;60:1376–1380. doi: 10.1172/JCI108898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiggins R C, Bouma B N, Cochrane C G, Griffin J H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;77:4636–4640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gustaafson E J, Schutsky D, Knight L, Schmaier A H. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:310–318. doi: 10.1172/JCI112567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greengard J S, Griffin J H. Biochemistry. 1984;23:6863–6869. doi: 10.1021/bi00321a090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meloni E J, Gustafson E J, Schmaier A H. Blood. 1992;79:1233–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmaier A H, Kuo A, Lundberg D, Murray S, Cines D B. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:16327–16333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Iwaarden F, de Groot P G, Bouma B N. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4698–4703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddigari S R, Kuna P, Miragliotta G, Shibayama Y, Nishikawa K, Kaplan A P. Blood. 1993;81:1306–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasan A A, Cines D B, Herwald H, Schmaier A H, Muller-Esterl W. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19256–19261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddigari S R, Shibayama Y, Brunnee T, Kaplan A P. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11982–11987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverberg M, Dunn J T, Garen L, Kaplan A P. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:7281–7286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tankersley D L, Finlayson J S. Biochemistry. 1984;23:273–279. doi: 10.1021/bi00297a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffin J H, Cochrane C G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;73:2554–2558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.8.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meier H L, Pierce J V, Colman R W, Kaplan A P. J Clin Invest. 1977;60:18–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI108754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiggins R C, Loscutoff D J, Cochrane C G, Griffin J H, Edgington T S. J Clin Invest. 1980;65:197–206. doi: 10.1172/JCI109651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerbiriou D M, Griffin J H. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:12020–12027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motta G, Rojkjaer R, Hasan A A K, Cines D B, Schmaier A H. Blood. 1998;91:516–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rojkajaer R, Hasan A A K, Motta G, Schousboe I, Schmaier A H. Thromb Haemostasis. 1998;80:74–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joseph K, Ghebrehiwet B, Peerschke E I, Reid K B, Kaplan A P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8552–8557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaffe E A. Transplant Proc. 1980;12:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli U K. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradford M M. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gustafson E J, Schmaier A H, Wachtfogel Y T, Kaufman N, Kucich U, Colman R W. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:28–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI114151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Y, Pixley R A, Colman R W. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5104–5110. doi: 10.1021/bi992048z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herwald H, Morgelin M, Svensson H G, Sjobring U. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:396–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2001.01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richter K, Muschler P, Hainzl O, Buchner J. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33689–33696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aligue R, Akhavan-Niak H, Russell P. EMBO J. 1994;13:6099–6106. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cutforth T, Rubin G M. Cell. 1994;77:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90442-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nathan D F, Lindquist S. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3917–3925. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nathan D F, Vos M H, Lindquist S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12949–12956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pratt W B, Toft D O. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:306–360. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao D F, Jin Z G, Baas A S, Daum G, Gygi S P, Aebersold R, Berk B C. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:189–196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muller-Esterl W, Fritz H, Machleidt W, Ritonja A, Brzin J, Kotnik M, Turk V, Kellerman J, Lottspeich F. FEBS Lett. 1985;182:310–314. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higashiyama S, Ohkubo I, Ishiguro H, Kunimatsu M, Sawaki K, Ssaki M. Biochemistry. 1986;25:1669–1675. doi: 10.1021/bi00355a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishiguro H, Higashiyama S, Ohkubo I, Sasaki M. Biochemistry. 1987;26:7021–7029. doi: 10.1021/bi00396a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McClintock D K, Bell P H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971;43:694–702. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(71)90670-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reddy K N N, Markus G. J Biol Chem. 1971;247:1683–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joseph K, Shibayama Y, Ghebrehiwet B, Kaplan A P. Thromb Haemostasis. 2001;85:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Renne T, Dedio J, David G, Muller-Esterl W. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33688–33696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]