Abstract

Recently, doped graphene has emerged as a promising material for gas sensing applications. In this study, we performed first-principles calculations to investigate the adsorption of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) on pristine, nitrogen (N)-doped, ruthenium (Ru)-doped, and N–Ru-co-doped graphene surfaces. The adsorption energies, Mulliken charge distributions, differential charge densities, electronic density of states, and optical properties of NO2 on the graphene surfaces were evaluated. The adsorption energies follow the order N–Ru-co-doped > Ru-doped > N-doped > pristine graphene, suggesting that doped graphene has higher sensitivity to NO2 gas molecules than pristine graphene. Analysis of the charge transfer and differential charge densities indicated weak physisorption of NO2 on pristine and N-doped graphene, whereas stronger chemisorption of NO2 occurred on Ru-doped and N–Ru-co-doped graphene because of the formation of chemical bonds between NO2 and the doped surfaces. The peak absorption and reflection coefficients of NO2 adsorbed on N–Ru-co-doped graphene are approximately 2.88 and 7.75 times higher, respectively, than those of NO2 adsorbed on pristine graphene. The substantial changes of the electronic and optical properties of N–Ru-co-doped graphene upon interaction with NO2 can be exploited for the development of highly sensitive and selective NO2 gas sensors.

1. Introduction

Environmental pollution has reached alarming levels because of the rapid advance of modern industrialized society. A pollutant of considerable concern is nitrogen dioxide (NO2), which is a toxic and hazardous gas that poses a substantial threat to human health and the environment.1 As a major atmospheric contaminant, NO2 infiltrates the ozone layer, catalyzes atmospheric degradation, and reacts with oxygen and water vapor to form nitric acid, which corrodes plants and materials such as metals and concrete, leading to soil acidification and decreased fertility.2−5 Moreover, NO2 can damage the human liver, kidneys, and respiratory system, and it can be fatal in severe cases.6−8 Consequently, the detection and capture of NO2 gas molecules are of great importance for environmental monitoring, industrial chemical processing, public safety, agriculture, medicine, and indoor air quality control.

Over the past few years, ultrathin two-dimensional (2D) materials have attracted remarkable interest owing to their unique structural, optoelectronic, mechanical, and thermal properties.9−11 The excellent sensing properties of some 2D materials, such as graphene and MoS2, have been demonstrated by theoretical and experimental studies.12−14 One of the most popular 2D layered materials is graphene, which consists of sp2-hybridized carbon atoms in a honeycomb lattice. Graphene has excellent optical, electrical, and thermal properties, high carrier mobility, large specific surface area, low electrical noise, and the ability to detect various gas molecules with high resolution even at room temperature, and it has thus been widely investigated as a promising material for gas sensing.15−18 However, the pristine graphene surface is chemically inert, and the zero band gap of graphene decreases its sensitivity to gas molecules.19,20 To overcome these limitations and substantially improve its sensing performance, graphene can be modified by adding impurity atoms to its surface, such as B, N, S, and Si dopants, which strengthens the interaction between graphene and common gases (e.g., CO, CO2, COCl2, and O2).21−27 Doping graphene with transition metals (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni, Ru, Mo, Ti, Ga, Mn, and Pt) also improves its ability to adsorb gases such as O2, SO2, COCl2, and NH3.28−31 Accordingly, adsorption and sensing applications of doped graphene have become research hotspots. However, there have only been a few studies on the gas-sensing capability of nonmetal and metal codoped graphene. In this study, we investigated the adsorption of NO2 molecules on the surfaces of pristine, nonmetal (N)-doped, metal (Ru)-doped, and nonmetal (N)–metal (Ru) codoped graphene by dispersion-corrected density functional theory (DFT) simulations and calculated the geometric, energetic, electronic, and optical properties of the systems. By extending the investigation of doped graphene in the field of adsorption and sensing applications, this study will provide theoretical support for research on graphene-based sensor materials.

2. Model Construction and Calculation Method

All of the DFT calculations to investigate the interaction between NO2 gas molecules and the graphene surfaces were performed with the CASTEP code. To ensure the accuracy of the calculations, the calculations incorporated the Grimme dispersion correction with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange–correlation functional under the generalized gradient approximation, accounting for the effects of the dispersion interactions, long-range electronic correlation effects, and van der Waals forces.32,33 The geometry optimizations were performed using the plane-wave ultrasoft pseudopotential method, where the ionic potentials are replaced with pseudopotentials that describe the electron–ion interactions. The Kohn–Sham equations and energy functionals were solved through self-consistency. A 4 × 4 × 1 supercell model of each graphene surface consisting of 32 atoms was constructed to prevent interlayer interactions. A vacuum layer of 20 Å was introduced, and the plane-wave truncation energy was set to 430 eV. The atomic force convergence accuracy was set to 0.03 eV/Å to ensure accurate calculations. The energy self-consistency accuracy converged to 5 × 10–7 eV/atom and the intra-atomic stress was maintained at 0.05 GPa. The Brillouin zone k-point grid was set to 4 × 4 × 1 to adequately sample the system.

To investigate whether the doped graphene structure is stable, we calculated the binding energy (Eb)

| 1 |

where E(G+C) is the energy of the doped system, E(C) is the energy of a single dopant atom, and E(G) is the energy of the vacant graphene corresponding to the number of dopant atoms.34 When Eb is negative, the doped structure is stable.

To study the adsorption state of NO2 on the doped graphene sheets, the adsorption energy of NO2 (Eads) was calculated by

| 2 |

where Egas is the energy of a single NO2 gas molecule, Egraphene is the energy of graphene without adsorbed NO2 molecules, and Egas+graphene is the total energy of the whole adsorption system.35 When Eads is positive, the energy of the system is high and adsorption is energetically unfavorable. When Eads is negative, the adsorption process is exothermic, the energy of the system decreases, the structure is stable, and adsorption readily occurs.

3. Results and Discussion

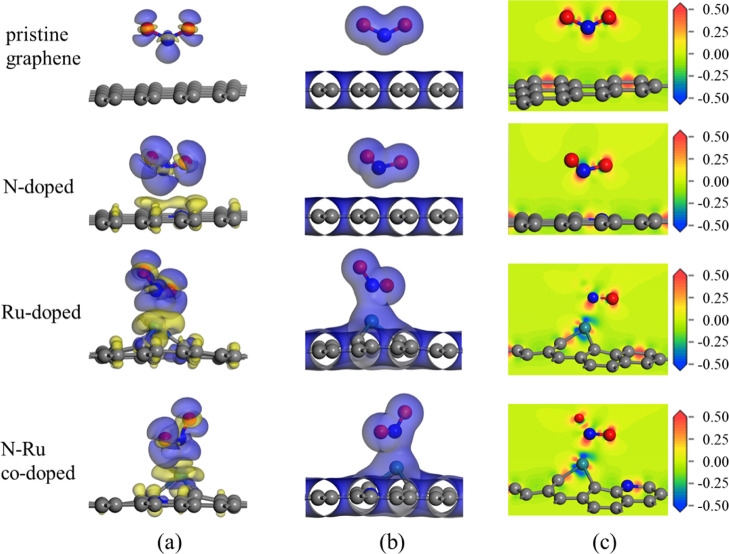

Three adsorption sites were considered for the adsorption of NO2 on the graphene surfaces: the top site above a carbon atom (T), the center of a carbon ring (H), and the bridge site above a C–C bond (B). Through calculation, the orientation of the NO2 molecule was chosen to have the N atom facing downward with an initial adsorption distance of 3 Å, as shown in Figure 1. Based on the combinations of the adsorption sites and doped atoms, a total of 14 models were constructed.

Figure 1.

(a) Top view and (b) side view of a NO2 molecule adsorbed on the surface of pristine graphene.

3.1. Adsorption Distance and Adsorption Energy

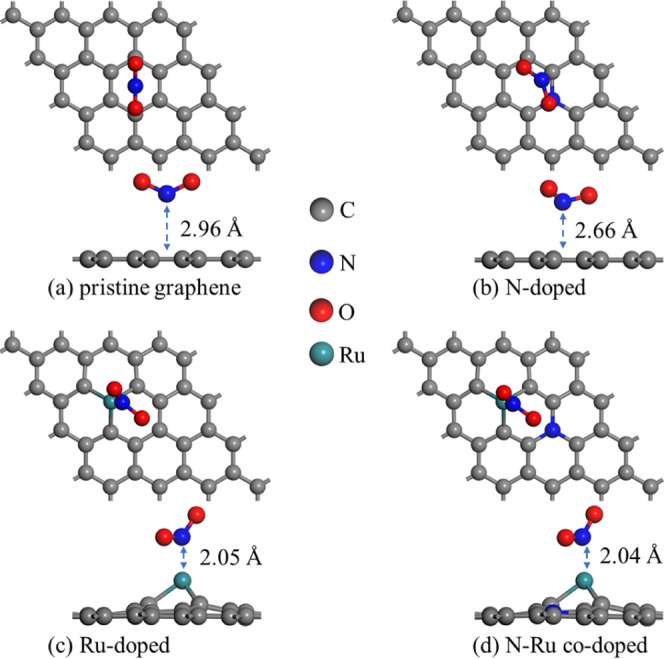

According to the adsorption distances and Eads values (Table S1), the H site was found to be the most stable site for NO2 adsorption among the three sites. Therefore, here, we focus on the data for the H site. The data for the other two sites are provided in the Supporting Information. The atomic structures of NO2 molecules adsorbed on the pristine and doped graphene surfaces after optimization are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Top and side views of NO2 adsorbed on (a) pristine graphene, (b) N-doped graphene, (c) Ru-doped graphene, and (d) N–Ru-co-doped graphene.

The adsorption distances before and after the adsorption of NO2 molecules, Eads values, and Eb values of the doped graphene surfaces are given in Table 1. The Eb values for the doped graphene surfaces are all negative, indicating that the doped graphene structures are stable. This provides a solid foundation for the subsequent adsorption of NO2 molecules on the doped graphene surfaces.

Table 1. Pre-adsorption Distances (dpre), Post-adsorption Distances (dpost), Adsorption Energies (Eads), and Binding Energies (Eb) of NO2 on the Different Graphene Surfaces.

| model | dpre/Å | dpost/Å | Eads/eV | Eb/eV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pristine graphene | 3 | 2.96 | –0.22 | |

| N-doped | 3 | 2.66 | –0.69 | –15.43 |

| Ru-doped | 3 | 2.05 | –7.20 | –6.29 |

| N–Ru codoped | 3 | 2.04 | –7.41 | –19.73 |

The adsorption energies (Eads) of all of the models are negative, indicating that the systems become more stable and have lower energy after NO2 adsorption. According to the literature, Eads > 0.8 eV indicates chemisorption, whereas Eads < 0.6 eV indicates physisorption.36 Based on these criteria, it can be inferred that NO2 molecules physisorb on pristine and N-doped graphene, suggesting weak adsorption of NO2 on these graphene surfaces. In contrast, Eads of NO2 on Ru-doped and N–Ru codoped graphene exhibited a significant change from that on pristine graphene (approximately −0.2 eV) to approximately −7 eV. The magnitude of Eads suggests strong interactions between the Ru-doped and N–Ru codoped graphene surfaces and NO2 gas molecules, indicating chemisorption. Furthermore, the distances between the NO2 molecules and these two graphene surfaces are smaller than that between pristine graphene and NO2. Considering Eads and the adsorption distances, it can be inferred that chemical bonds form between the Ru-doped and N–Ru codoped graphene surfaces and NO2 molecules.

3.2. Charge Transfer Analysis

The Mulliken charge distributions of the NO2 molecules adsorbed on the different graphene surfaces are given in Table 2. All of the surfaces undergo charge transfer with the NO2 molecules. The amount of charge transfer follows the order N–Ru-co-doped graphene > Ru-doped graphene > N-doped graphene > pristine graphene. These results indicate that NO2 acts as an electron acceptor in the charge transfer process, indicating reduction of NO2 by the graphene surface. Additionally, the bond lengths of the NO2 molecules are affected by adsorption on the graphene surfaces. The observed charge transfer and changes of the NO2 molecule bond lengths indicate strong interactions between the doped graphene surfaces and NO2 molecules. Strong interactions are beneficial for gas sensing because they lead to high sensitivity of the doped graphene surface for NO2.

Table 2. Mulliken Charge Distributions of the NO2 Molecules before and after Adsorption on the Different Graphene Surfaces.

| model | species | selection | p electron | total | charge/e | molecular charge/e | population | bond length/Å |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO2 | N | 1.39 | 3.18 | 4.57 | 0.44 | 0 | 0.68 | 1.23 |

| O | 1.85 | 4.36 | 6.22 | –0.22 | ||||

| O | 1.85 | 4.36 | 6.22 | –0.22 | ||||

| pristine graphene | N | 1.46 | 3.21 | 4.67 | 0.33 | –0.25 | 0.63 | 1.24 |

| O | 1.86 | 4.44 | 6.29 | –0.29 | ||||

| O | 1.86 | 4.44 | 6.29 | –0.29 | ||||

| N-doped | N | 1.51 | 3.23 | 4.74 | 0.26 | –0.48 | 0.60 | 1.25 |

| O | 1.86 | 4.53 | 6.39 | –0.38 | ||||

| O | 1.86 | 4.51 | 6.36 | –0.36 | ||||

| Ru-doped | N | 1.47 | 3.37 | 4.84 | 0.16 | –0.49 | 0.67 | 1.27 |

| O | 1.87 | 4.47 | 6.34 | –0.34 | ||||

| O | 1.86 | 4.45 | 6.31 | –0.31 | ||||

| N–Ru codoped | N | 1.47 | 3.37 | 4.84 | 0.16 | –0.51 | 0.67 | 1.27 |

| O | 1.87 | 4.49 | 6.36 | –0.36 | ||||

| O | 1.86 | 4.45 | 6.31 | –0.31 |

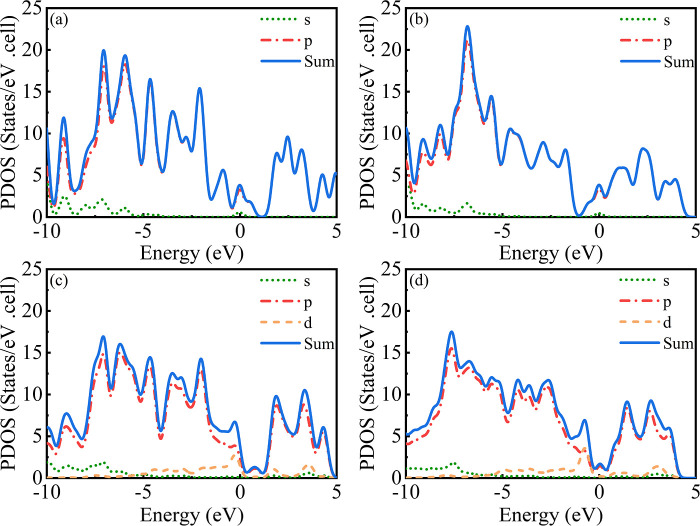

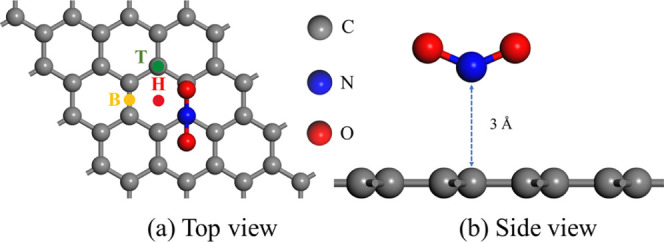

The charge density difference (CDD), total charge density (TCD), and electron density difference (EDD) plots of the NO2 molecules adsorbed on the pristine and doped graphene surfaces are shown in Figure 3. The CDD plots clearly show substantial charge transfer between the pristine and doped graphene surfaces and adsorbed NO2 molecules. During the adsorption process, charge accumulation occurs on the NO2 gas molecules and charge dissipation occurs at the adsorption sites on the graphene surfaces. Analysis of the TCD maps shown in Figure 3b and EDD plots shown in Figure 3c revealed that the electron orbitals of the pristine and N-doped graphene surfaces do not markedly overlap with those of NO2, indicating weak interactions between these surfaces and the NO2 molecules. In contrast, the electron orbitals of the Ru-doped and N–Ru-co-doped graphene surfaces clearly overlap with those of NO2, suggesting the formation of chemical bonds between these surfaces and the gas molecules. These observations confirm the strong interactions between NO2 and the Ru-doped and N–Ru-co-doped graphene surfaces. These findings align with Eads and the Mulliken charge predictions for the interaction of NO2 molecules with the different graphene surfaces.

Figure 3.

(a) Charge density difference, (b) total charge density, and (c) electron density difference plots of NO2 molecules adsorbed on the different graphene surfaces. The isosurfaces of the charge density difference plots are set to 0.01 e/Å3, where blue represents electron accumulation and yellow represents electron depletion. The isosurfaces of the total charge density plots are set to 0.02 e/Å3. In the electron density difference plots, red represents charge accumulation and blue represents charge depletion.

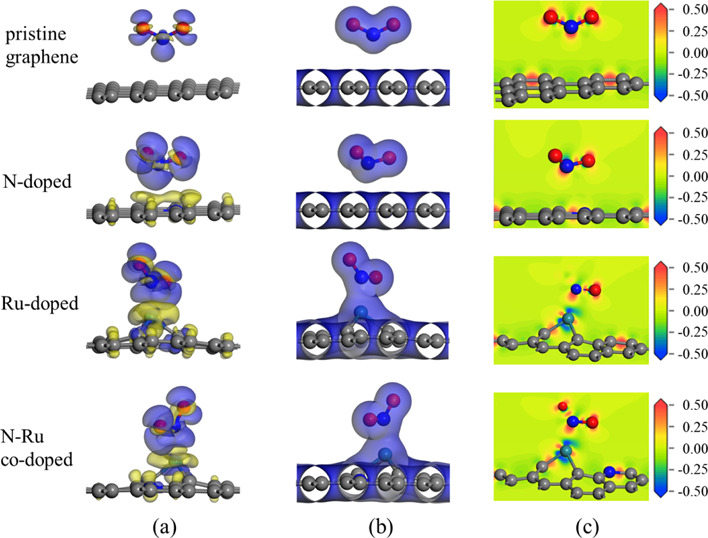

3.3. Surface Electron State Density

To further analyze the electronic energies of the graphene-based systems after the adsorption of NO2 molecules, the density of states (DOS) was calculated following the adsorption of a NO2 molecule on each of the different surfaces (Figure 4). The DOSs of the doped surfaces generally shift toward the valence band compared with that of the pristine graphene surface. Additionally, the number of wave peaks in the valence band increases and the number of wave peaks in the conduction band decreases after doping of the graphene surface. The peaks from the impurity energy levels near the Fermi level also change after doping of the graphene surface. These phenomena suggest that the electronic properties of the doped systems are different from those of pristine graphene. This can be attributed to the electronic hybridization of the dopant atoms, as shown in Figure 4d, where the synergistic interaction of the 2p and 4d electrons of N and Ru with the 2p electrons of C atoms modifies the DOS of the codoped system. These changes of the DOS, particularly in the region near the Fermi level, affect the electronic properties of the doped systems, which is advantageous for sensing applications.

Figure 4.

Partial density of states (PDOS) of adsorbed NO2 molecules on the graphene surfaces. (a) Pristine graphene, (b) N-doped graphene, (c) Ru-doped graphene, and (d) N–Ru-co-doped graphene.

3.4. Optical Properties

The dielectric functions, absorption spectra, and reflection spectra of the four graphene-based systems were calculated before and after NO2 adsorption. The optical properties of a material can be described by the dielectric function. This is because the electron jump energy is much larger than the energy of phonon perturbation, so the effect of the perturbation of the radiated electric field on the electron absorption of the photon energy from low to high energy levels can be ignored. The real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function describe the processes of photon absorption and release in a material. The complex form ε(ω) = ε1(ω) + iε2(ω) describes the process of electron migration, where ω is the angular frequency, ε1 = n2– k2 and ε2 = 2nk, in which n is the refractive index and k is the wavenumber.37 The real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function can be derived from the Kramers–Kronig dispersion relation. In addition, the absorption coefficient I(ω) and reflectivity R(ω) can be derived from the Kramers–Kronig dispersion relation as follows38

| 3 |

| 4 |

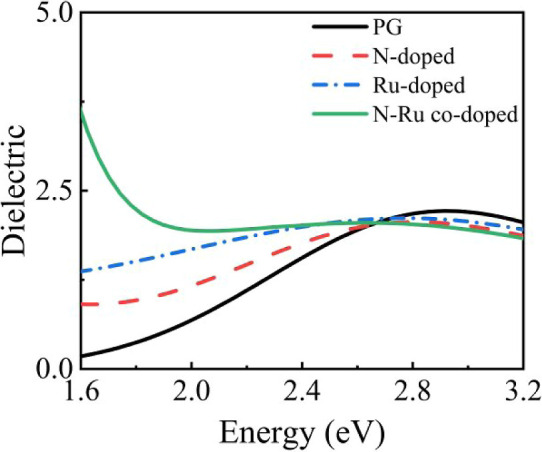

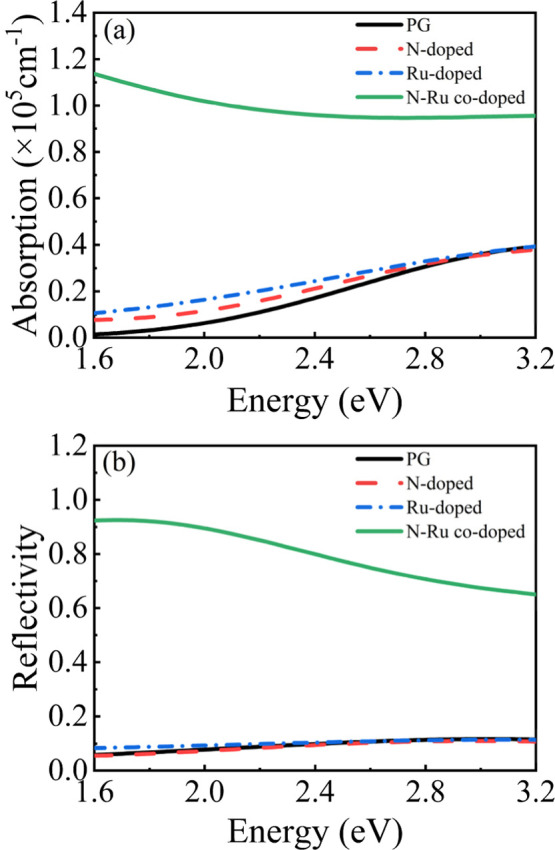

The imaginary parts of the dielectric functions before and after NO2 adsorption on the different graphene surfaces in the visible range (1.6–3.2 eV) are shown in Figure 5. Within the energy range of 1.6–2.6 eV, the imaginary part values on the doped graphene surfaces are higher than those on the pristine graphene surface, with Ru–N-co-doped graphene exhibiting the highest value. In the energy range of 2.6–3.2 eV, the imaginary part values of the doped graphene surfaces are slightly smaller than those of the pristine graphene surface, with Ru–N-co-doped graphene showing the smallest imaginary part value. Therefore, in the visible range, the Ru–N-co-doped graphene surface exhibits the largest variation of the imaginary part of the dielectric function among the graphene-based surfaces.

Figure 5.

Imaginary parts of the dielectric functions of the different graphene surfaces after adsorption of NO2.

The absorption rate is directly related to the number of electrons in the ground state that absorb photon energy and transition to the excited state. This phenomenon reflects the ability of a material to respond to light. Similarly, higher R(ω) indicates that more electrons absorb photon energy and transition to an excited state, which is followed by the release of energy as they transition back to lower energy levels.

The calculated absorption and reflection spectra of NO2 molecules adsorbed on the different graphene surfaces are shown in Figure 6a,b, respectively. In the visible range, the peak absorption coefficient of the pristine graphene surface of approximately 39,200 cm–1 occurs at 3.2 eV and the peak reflection coefficient of approximately 0.12 occurs at 3 eV. The optical properties of the N-doped and Ru-doped graphene surfaces with adsorbed NO2 are similar to those of pristine graphene with adsorbed NO2. However, N–Ru codoping greatly affects the optical properties of the graphene surface with adsorbed NO2. The N–Ru-co-doped system exhibits a peak absorption coefficient of approximately 112,900 cm–1 at 1.6 eV and a peak reflection coefficient of approximately 0.93 at 1.7 eV. These values are approximately 2.88 and 7.75 times higher than the corresponding peak absorption and reflection coefficients of pristine graphene, respectively. Therefore, the N–Ru-co-doped graphene system shows superior optical sensing capability for NO2 to pristine graphene. The trend is the same for the optical properties of the other two adsorption sites (B and T sites) (see Figures S9 and S10).

Figure 6.

Optical properties of the different graphene surfaces after adsorption of NO2. (a) Absorption spectra and (b) reflection spectra.

A comparative analysis of the dielectric functions, absorption spectra, and reflection spectra of NO2 molecules adsorbed on the different graphene surfaces revealed that the trends in the absorption and reflection spectra are consistent with the changes of the dielectric function. In particular, N–Ru codoping markedly enhances the optical properties of NO2 adsorbed on the graphene surface, particularly within the visible range.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we performed DFT-based first-principles calculations to investigate the adsorption behavior of NO2 gas molecules on pristine, metal-doped, nonmetal-doped, and metal–nonmetal-co-doped graphene surfaces. Various properties, including the adsorption energy, Mulliken charge distribution, differential charge density, DOS, and optical properties, were examined to characterize the interaction between NO2 and the different graphene surfaces. The results indicated that NO2 can adsorb to all four types of graphene, with the doped graphene surfaces showing stronger NO2 adsorption than pristine graphene. Pristine and N-doped graphene show physical adsorption of NO2, whereas the introduction of transition metal atoms, such as Ru, leads to strong chemical adsorption because of the formation of chemical bonds between NO2 and the doped graphene surfaces. The N–Ru-co-doped system shows the highest adsorption energy of −7.41 eV. Comparison of the DOS revealed that doped graphene materials are more sensitive to NO2 gas molecules than pristine graphene. The electronic properties of graphene change upon NO2 adsorption, and the optical properties of the doped graphene surfaces are improved compared with those of pristine graphene. Notably, the N–Ru-co-doped graphene surface exhibits the largest changes in the absorption and reflectance coefficients upon NO2 adsorption, which are approximately 2.88 and 7.75 times higher than those of pristine graphene, respectively. The substantial changes in the electronic and optical properties of N–Ru-co-doped graphene upon interaction with NO2 make it a promising candidate for NO2 gas detection applications.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (grant nos. CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0207 and CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0425), the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission, China (grant nos. KJQN202200569, KJQN202200507 and KJQN202300513), the Scientific and Technological Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission, China (grant no. KJZD-K202300516), the Higher Education Teaching Reform Research Project of Chongqing, China (grant no. 223145), and the “Curriculum Ideological and Political” Demonstration Project of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission, China (grant no. YKCSZ23102). We thank Liwen Bianji (Edanz) (www.liwenbianji.cn/) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c09163.

Data on adsorption energy, density of states, differential charge density, and optical properties of NO2 molecules adsorbed on graphene surfaces (T-site and B-site), among others (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cooper M. J.; Martin R. V.; Hammer M. S.; Levelt P. F.; Veefkind P.; Lamsal L. N.; Krotkov N. A.; Brook J. R.; McLinden C. A. Global fine-scale changes in ambient NO2 during COVID-19 lockdowns. Nature 2022, 601, 380–387. 10.1038/s41586-021-04229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H.; Kwon H.; Kang H.; Jang J. E.; Kwon H. J. Semiconducting MOFs on ultraviolet laser-induced graphene with a hierarchical pore architecture for NO2 monitoring. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3114. 10.1038/s41467-023-38918-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi A.; Sardroodi J. J. A highly sensitive chemical gas detecting device based on N-doped ZnO as a modified nanostructure media: A DFT plus NBO analysis. Surf. Sci. 2018, 668, 150–163. 10.1016/j.susc.2017.10.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S. G.; Choi W. M. Predicting the adsorption and reduction of NO2 on Sr-doped CeO2(111) using first-principles calculations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 612, 155896. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.155896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang A. L.; Mo M.; Kuang M. Q.; Wang B.; Tian C. L.; Yuan H. K.; Wang G. Z.; Chen H. The comparative study of XO2 (X = C, N, S) gases adsorption and dissociation on pristine and defective graphene supported Pt13. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 247, 122712. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2020.122712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almaraz M.; Bai E.; Wang C.; Trousdell J.; Conley S.; Faloona I.; Houlton B. Z. Agriculture is a major source of NOx pollution in California. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, 3477. 10.1126/sciadv.aao3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng X.; Li S. W.; Mawella-Vithanage L.; Ma T.; Kilani M.; Wang B. W.; Ma L.; Hewa-Rahinduwage C. C.; Shafikova A.; Nikolla E.; Mao G. Z.; Brock S. L.; Zhang L.; Luo L. Atomically dispersed Pb ionic sites in PbCdSe quantum dot gels enhance room-temperature NO2 sensing. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4895. 10.1038/s41467-021-25192-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S. G. First-principles prediction of NO2 and SO2 adsorption on MgO/(Mg0.5Ni0.5)O/MgO(100). Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 566, 150650. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.150650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi A.; Sardroodi J. J. Adsorption of O3, SO2 and SO3 gas molecules on MoS2 monolayers: A computational investigation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 469, 781–791. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.11.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi A. Tuning the structural and electronic properties and chemical activities of stanene monolayers by embedding 4d Pd: a DFT study. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 16069–16082. 10.1039/C9RA01472A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi A.; Sardroodi J. J. Exploration of sensing of nitrogen dioxide and ozone molecules using novel TiO2/Stanene heterostructures employing DFT calculations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 442, 368–381. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.02.183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F. Z.; Yang K.; Liu G. J.; Chen Y.; Wang M. H.; Li S. T.; Li R. F. Recent advances on graphene: Synthesis, properties and applications. Composites, Part A 2022, 160, 107051. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2022.107051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi A.; Sardroodi J. J. An Innovative Method for the Removal of Toxic SOx Molecules from Environment by TiO2/Stanene Nanocomposites: A First-Principles Study. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2018, 28, 1901–1913. 10.1007/s10904-018-0832-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi A.; Abdelrasoul A.; Sardroodi J. J. Adsorption of CO and NO molecules on Al, P and Si embedded MoS2 nanosheets investigated by DFT calculations. Adsorption 2019, 25, 1001–1017. 10.1007/s10450-019-00121-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang A. L.; Kuang M. Q.; Yuan H. K.; Wang G. Z.; Chen H.; Yang X. L. Acidic gases (CO2, NO2 and SO2) capture and dissociation on metal decorated phosphorene. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 410, 505–512. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.03.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang A. R.; Lim J. E.; Jang S.; Kang M. H.; Lee G.; Chang H.; Kim E.; Park J. K.; Lee J. O. Ag2S nanoparticles decorated graphene as a selective chemical sensor for acetone working at room temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 562, 150201. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.150201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esfahani S.; Akbari J.; Soleimani-Amiri S.; Mirzaei M.; Ghasemi Gol A. Assessing the drug delivery of ibuprofen by the assistance of metal-doped graphenes: Insights from density functional theory. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 135, 109893. 10.1016/j.diamond.2023.109893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Martínez H.; Rojas-Chávez H.; Montejo-Alvaro F.; Peña-Castañeda Y. A.; Matadamas-Ortiz P. T.; Medina D. I. Recent Developments in Graphene-Based Toxic Gas Sensors: A Theoretical Overview. Sensors 2021, 21, 1992. 10.3390/s21061992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamim S. U. D.; Roy D.; Alam S.; Piya A. A.; Rahman M. S.; Hossain M. K.; Ahmed F. Doubly doped graphene as gas sensing materials for oxygen-containing gas molecules: A first-principles investigation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 596, 153603. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.153603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B.; Li D. B.; Qi L.; Li T. B.; Yang P. Thermal properties of triangle nitrogen-doped graphene nanoribbons. Phys. Lett. A 2019, 383, 1306–1311. 10.1016/j.physleta.2019.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P. C.; Tang F.; Wang S. F.; Cao W.; Wang Q. Adsorption performance of CNCl, NH3 and GB on modified graphene and the selectivity in O2 and N2 environment. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104280. 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.104280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia X. T.; Zhang H.; Zhang Z. M.; An L. B. First-principles investigation of vacancy-defected graphene and Mn-doped graphene towards adsorption of H2S. Superlattices Microstruct. 2019, 134, 106235. 10.1016/j.spmi.2019.106235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia X.; An L. The adsorption of nitrogen oxides on noble metal-doped graphene: The first-principles study. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2019, 33, 1950044. 10.1142/S0217984919500441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhuri I.; Patra N.; Mahata A.; Ahuja R.; Pathak B. B-N@Graphene: Highly Sensitive and Selective Gas Sensor. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 24827–24836. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b07359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y.; Li F.; Zhu Z. H.; Zhao M. W.; Xu X. G.; Su X. Y. An ab initio study on gas sensing properties of graphene and Si-doped graphene. Eur. Phys. J. B 2011, 81, 475–479. 10.1140/epjb/e2011-20225-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Odey D. O.; Edet H. O.; Louis H.; Gber T. E.; Nwagu A. D.; Adalikwu S. A.; Adeyinka A. S. Heteroatoms (B, N, and P) doped on nickel-doped graphene for phosgene (COCl2) adsorption: insight from theoretical calculations. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 21, 100294. 10.1016/j.mtsust.2022.100294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J.; Yuan J.; Giannozzi P. Gas adsorption on graphene doped with B, N, Al, and S: A theoretical study. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 95, 232105. 10.1063/1.3272008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T.; Sun H.; Wang F. G.; Zhang W. Q.; Tang S. W.; Ma J. M.; Gong H. W.; Zhang J. P. Adsorption of phosgene molecule on the transition metal-doped graphene: First principles calculations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 425, 340–350. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.06.229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasehnia F.; Seifi M. Adsorption of molecular oxygen on VIIIB transition metal doped graphene: A DFT study. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2014, 28, 1450237. 10.1142/S0217984914502376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. Y.; Ding N.; Ng S. P.; Wu C. M. L. Adsorption of gas molecules on Ga-doped graphene and effect of applied electric field: A DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 411, 11–17. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.03.178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. P.; Luo X. G.; Lin X. Y.; Lu X.; Leng Y.; Song H. T. Density functional theory calculations on the adsorption of formaldehyde and other harmful gases on pure, Ti-doped, or N-doped graphene sheets. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 283, 559–565. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.06.145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basiuk V. A.; Henao-Holguin L. V. Dispersion-corrected density functional theory calculations of meso-tetraphenylporphine-C60 complex by using DMol3 module. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2014, 11, 1609–1615. 10.1166/jctn.2014.3539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. H.; Wang Z. Y.; Su X. P. First-principles investigation of cohesive energy and electronic structure in vanadium phosphides. J. Cent. South Univ. 2012, 19, 1796–1801. 10.1007/s11771-012-1210-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; Zhang J. M.; Xu K. W.; Ji V. A first-principles study on gas sensing properties of graphene and Pd-doped graphene. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 343, 121–127. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.03.068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J. Y.; Liu Y.; Chen Y. M. Enhancement of SO2 sensing performance of micro-ribbon graphene sensors using nitrogen doping and light exposure. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 608, 155059. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.155059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X.; Zhou Q.; Wang J. X.; Xu L. N.; Zeng W. Adsorption of SO2 molecule on Ni-doped and Pd-doped graphene based on first-principle study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 517, 146180. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z.; Dumitrica T.; Frauenheim T. First-principles prediction of infrared phonon and dielectric function in biaxial hyperbolic van der Waals crystal -α-MoO3. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 19627–19635. 10.1039/D1CP00682G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping L. K.; Mohamed M. A.; Mondal A. K.; Taib M. F. M.; Samat M. H.; Berhanuddin D. D.; Menon P. S.; Bahru R. First-Principles Studies for Electronic Structure and Optical Properties of Strontium Doped β-Ga2O3. Micromachines 2021, 12 (4), 348. 10.3390/mi12040348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.