Abstract

Introduction

Clinical decision‐making is based on objective and subjective criteria, including healthcare workers impressions and feelings. This research examines the perception and implications of a ‘bad feeling’ experienced by healthcare professionals, focusing on its prevalence and characteristics.

Methods

A cross‐sectional paper‐based survey was conducted from January to July 2023 at the University Medicine Greifswald and the hospital Sömmerda involving physicians, nurses, medical students and trainees from various specialties. With ethics committee approval, participants were recruited and surveyed at regular clinical events. Data analysis was performed using SPSS® Statistics. The manuscript was written using the Strobe checklist.

Results

Out of 250 questionnaires distributed, 217 were valid for analysis after a 94.9% return rate and subsequent exclusions. Sixty‐five per cent of respondents experience the ‘bad feeling’ occasionally to frequently. There was a significant positive correlation between the frequency of ‘bad feeling’ and work experience. The predominant cause of this feeling was identified as intuition, reported by 79.8% of participants, with 80% finding it often helpful in their clinical judgement. Notably, in 16.1% of cases, the ‘bad feeling’ escalated in the further clinical course into an actual emergency. Furthermore, 60% of respondents indicated that this feeling occasionally or often serves as an early indicator of a potential, yet unrecognised, emergency in patient care.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the relevance of clinical experience to decision‐making. As an expression of this, there is a correlation between the frequency of a ‘bad feeling’ and the number of years of experience. It is recommended that the ‘bad feeling’ be deliberately acknowledged and reinforced as an early warning signal for emergency situations, given its significant implications for patient safety. Future initiatives could include advanced training and research, as well as tools such as pocket maps, to better equip healthcare professionals in responding to this intuition.

Keywords: clinical decision‐making, early warning signals, emergency situations, healthcare professionals, intuition, patient care, patient safety

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

This study demonstrates a significant correlation between the experience of healthcare professionals and their intuitive ‘bad feeling’, indicating that increased clinical exposure enhances the acknowledgment of this intuition.

This study reveals that ‘bad feeling’ frequently signal impending emergencies, underscoring the importance of training healthcare professionals in intuitive decision‐making to enhance emergency readiness.

1. INTRODUCTION

Intuition, often referred to as a ‘gut feeling’, plays a crucial role in clinical decision‐making among healthcare professionals. This innate sense of knowing without conscious reasoning is a valuable asset in healthcare, guiding professionals as they navigate complex situations and make swift decisions (McCutcheon & Pincombe, 2001). As McCutcheon et al. describe, intuition intertwines expertise, knowledge and experience, adhering to the human brain's heuristic approach which efficiently finds reasonable solutions with limited time and information (Gigerenzer & Gaissmaier, 2011; Gigerenzer & Gigerenzer, 2015; McCutcheon & Pincombe, 2001; Oliva et al., 2016). Intuitive judgements often arise from pattern recognition and can expedite clinical diagnoses (Norman, 2009; Norman & Eva, 2010; Osman, 2004). This is particularly pertinent in high‐stakes environments such as emergency medicine, where initial impressions have a significant impact on patient outcomes (Beil et al., 2021; Dargahi et al., 2022; Gigerenzer & Gaissmaier, 2011). In addition to intuition, the healthcare professional's emotions can also have an influence on clinical decision‐making (Kozlowski et al., 2017).

In clinical parlance, the specific intuition referred to as a ‘bad feeling’ captures instances where clinicians sense alarm even though a patient's symptoms may not completely align with textbook scenarios. This study defines ‘bad feeling’ as a sustained unease that persists even when objective indicators such as respiratory rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation appear normal. These feelings are not just vague discomforts but are often rooted in the clinician's deep‐seated experiences and subconscious cues that something might be amiss. It is important to pay particular attention to this nuanced type of intuition, which is commonly referred to as a ‘bad feeling’. Unlike general intuitive senses, this type of intuition often specifically signals potential emergencies before they become overt.

In further exploration of intuition, Beglinger et al. highlighted the importance of first impressions in emergency settings, demonstrating a significant correlation between initial assessments of ‘looking ill’ and 30‐day patient mortality and morbidity rates (Beglinger et al., 2015). Additionally, Hassani et al. conducted qualitative interviews with nurses, exploring intuition's manifestations as both ‘feelings’ and ‘thoughts’. Nurses often described intuition as a ‘personal’ or ‘internal feeling’, sometimes viewing it as an alarm signal that prompts them to intensify patient observation and conduct further examinations (Hassani et al., 2016). Similarly, Kosowski et al. found that interviewees described their intuition as a sense that ‘there was something terribly wrong’ (Kosowski & Roberts, 2003). This aligns with Ilgen et al.'s observation in 2020 that clinical practice is fraught with uncertainty (Ilgen et al., 2020; Pomare et al., 2019).

Research into clinical intuition has mainly focused on nursing, leaving a gap in knowledge about how this phenomenon manifests across other healthcare roles. Furthermore, there is limited empirical evidence on the direct connection between these intuitive feelings and the occurrence of clinical emergencies. The significance of this study lies in its potential to bridge the gap in our understanding of how intuition, specifically ‘bad feelings’, functions across different healthcare roles beyond nursing. The primary objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence and characteristics of the ‘bad feeling’ among healthcare professionals. By delineating the nature and frequency of ‘bad feelings’, we aim to provide insights that could enhance the understanding of the management of these intuitive cues in clinical practice and investigate their role as a predictive tool for identifying emergent patient care situations.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

This cross‐sectional study was designed to systematically assess the prevalence and characterise the nuanced features of ‘bad feelings’ reported by healthcare professionals within two distinct hospital settings. The design aimed to capture a snapshot of attitudes and practices at one point in time. The STROBE cross‐sectional checklist was used to create the manuscript (Appendix S1).

2.2. Setting

This paper‐based survey was conducted from January to July 2023 in two healthcare facilities: University Medicine Greifswald, a tertiary care hospital specialising in a wide range of advanced medical treatments and research, and KMG Hospital Sömmerda, a primary care hospital, which primarily offers general medical care, outpatient services and basic inpatient care for common illnesses and conditions. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of University Medicine Greifswald on 12 December 2022 (registration number BB170/22), and by the Ethics Committee of the Landesärztekammer Thüringen for the KMG Klinikum Sömmerda (registration number 76776/2023/12).

2.3. Participants

In both clinics involved in the study, all employees with patient contact were invited to participate, ensuring a comprehensive inclusion of potential respondents. Participants for the study, including students, trainees, nurses and physicians from all specialties, were recruited during regular educational meetings across various medical departments. At the Sömmerda centre, recruitment from January to March 2023 encompassed specialties such as Emergency Medicine, Cardiology, Gastroenterology, Trauma Surgery, General Surgery, Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine. Similarly, at the Greifswald Centre, recruitment from January to July 2023 included Emergency Medicine, Internal Medicine, Trauma Surgery, General Surgery, Paediatric Surgery, Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine. Eligibility criteria for participation included being at least 18 years old, voluntary engagement and active involvement in direct patient care. To ensure the integrity of the data, each participant was allowed to complete the questionnaire only once. During the recruitment phase, the study's objectives and procedures were succinctly presented and explained, allowing for any questions to be addressed.

2.4. Measurement and data sources

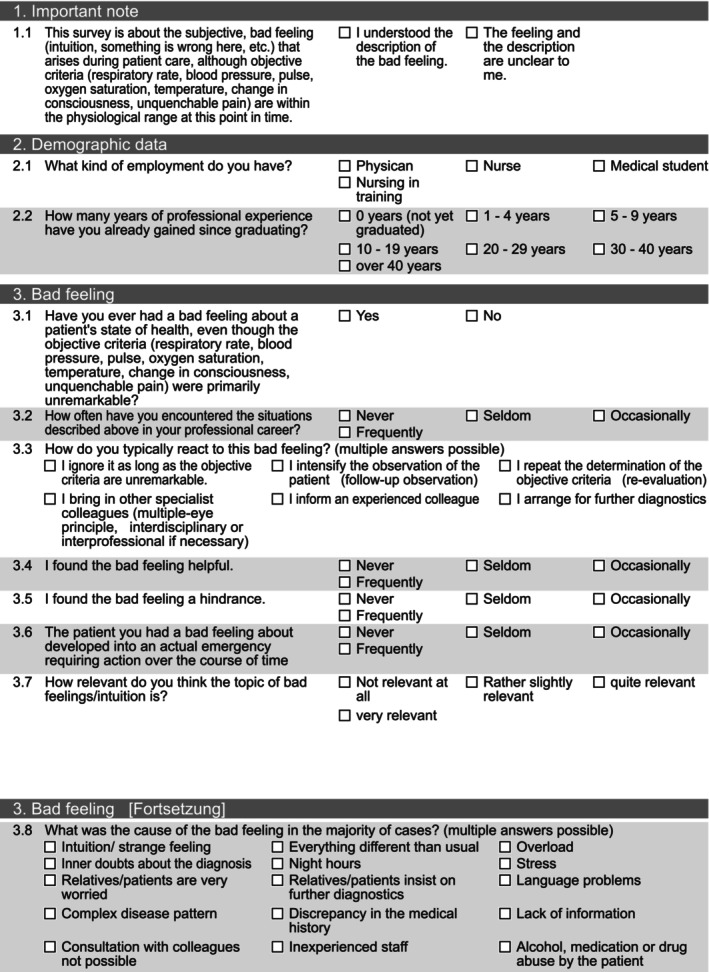

This study aims to analyse both the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the ‘bad feeling’, examine its correlation with work experience and assess its influence and implications in clinical settings. We developed a paper‐based questionnaire (refer to Figure 1) specifically for this study as the primary tool for data collection. In preparation for the survey, we assessed the validity of the questionnaire by testing it with 10 volunteers, including physicians, medical students and nurses. This testing focused on its comprehensibility and structural suitability for the project setting, and the insights gained from these volunteers were carefully used to refine the questionnaire. The questionnaire initially gathers socio‐demographic data, followed by an evaluation of the subjective ‘bad feeling’. This evaluation is conducted quantitatively using a 4‐point Likert scale and qualitatively through diverse categorisations. Additionally, the survey investigates the prognostic significance and impact of the ‘bad feeling’ utilising a similar 4‐point Likert scale approach.

FIGURE 1.

Paper‐based questionnaire on the ‘bad feeling'.

2.5. Study size

Prior to data collection, we conducted an a priori goodness‐of’fit and Spearman power analysis to determine the necessary sample size for detecting group differences. This analysis was based on an alpha error of 0.05 and a power of 0.95. The project team suggested an effect size of .3, which is in the low to medium range. Note that the underlying literature does not explicitly report effect size. The strategic decision to place the effect size between low and medium was made to balance ambition and feasibility. Consequently, the analysis indicated that a minimum sample size of 135 questionnaires would be required. It is worth noting that comparative studies focusing specifically on the ‘bad feeling’ are scarce. Existing research predominantly addresses the broader concept of intuition among nurses, with sample sizes in these studies varying considerably, ranging from as few as 12 to as many as 262 cases. (Hassani et al., 2016; McCutcheon & Pincombe, 2001).

2.6. Statistical methods

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using SPSS® Statistics Version 29 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA), while graphical representations were created with Prism 9® (GraphPad Software Inc., Boston, USA). Nominal data were presented as counts (n) and percentages, including valid percentages. For evaluating interval‐scaled characteristics in groups of more than two, the goodness‐of‐fit test was applied. In the case of ordinal‐scaled data, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to investigate associations. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p ≤ .05 for all tests. Data sets that were incomplete or entirely missing were systematically excluded from the analysis.

3. RESULTS

In this survey, 250 questionnaires were distributed among healthcare professionals across two hospitals, resulting in 237 completed responses and a high response rate of 94.9%. To validate the participants' understanding of the key concept, the ‘bad feeling’ was clearly defined at the survey's outset, followed by a question to confirm comprehension. Nineteen respondents who did not answer this critical question were excluded, leaving 217 questionnaires for analysis.

3.1. Participant characteristics

The participant distribution was as follows: 158 professionals from University Medicine Greifswald and 59 from KMG Klinikum Sömmerda. Regarding professional roles, 58 respondents (28.4%) were physicians, 119 (58.3%) were nurses, 19 (9.3%) were medical students and 8 (3.9%) were nursing trainees. Thirteen participants (6.0%) did not specify their role.

The analysis of professional experience was categorised into seven groups. Among the respondents, 26 (12.0%) had not yet completed their degree. Fifty‐five participants (25.3%) had 1–4 years of experience, 31 (14.3%) had 5–9 years, 38 (17.5%) had 10–19 years and 31 (14.3%) had 20–29 years of experience. For those with 30–40 years of experience, there were 22 respondents (10.1%), while six (2.8%) reported having more than 40 years of experience. Eight participants (3.7%) did not disclose their years of experience.

3.2. Frequency of the ‘bad feeling’

The occurrence of the ‘bad feeling’ varied among participants. Only one (0.4%) reported never experiencing it. A minority, 53 participants (24.4%), seldom felt it, while a notable majority, 102 (47%), experienced it occasionally. A further 40 (18.3%) encountered the feeling frequently. However, 21 respondents (9.6%) did not provide an answer to this question. A significant positive correlation was found between the frequency of experiencing the ‘bad feeling’ and the professionals' work experience, as evidenced by a Spearman correlation coefficient of .363 (p < .001). The frequency of the ‘bad feeling’ does not differ significantly between the University Medicine Greifswald and the KMG Klinikum Sömmerda (p = .577).

Additionally, analysis revealed a significant variation in the occurrence of the ‘bad feeling’ across different healthcare professional groups (refer to Table 1, p < .001).

TABLE 1.

Incidence ‘bad feeling’ in relation to healthcare professional groups.

| Healthcare professional groups | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physican | Nurse | Medical student | Nurse in training | ||

| Incidence ‘bad feeling’ | |||||

| Never | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Seldom | 21 | 19 | 9 | 4 | 53 |

| Occasionally | 24 | 67 | 9 | 2 | 102 |

| Often | 11 | 28 | 0 | 1 | 40 |

| Total | 56 | 114 | 18 | 8 | 196 |

3.3. Perceived quality of the ‘bad feeling’

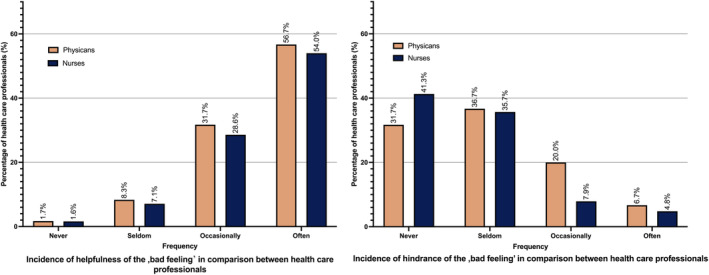

Regarding the perceived helpfulness of the ‘bad feeling’, a small proportion of participants, 2.3%, never found it helpful, while 8.3% rarely did. A larger segment, 27.6%, reported it being occasionally helpful, and the majority, 54.4%, frequently found it beneficial. However, 7.4% of respondents did not provide an answer to this question (refer to Figure 2). Notably, there was no statistically significant difference in the perception of helpfulness between physicians and nurses (p = .85).

FIGURE 2.

Frequency of helpfulness and hindrance of the ‘bad feeling’ in comparison between the health care professionals. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In terms of its hindrance, 39.2% of participants reported never finding the ‘bad feeling’ to be a hindrance, whereas 37.3% rarely found it so. A smaller group, 11.1%, occasionally perceived it as a hindrance, and 4.6% often felt hindered by it. A total of 7.8% did not respond to this question (refer to Figure 2). The frequency of perceiving it as a hindrance did not significantly differ between physicians and nurses (p = .06). In terms of helpfulness and hindrance, the answers did not differ significantly between the University Medicine Greifswald and the KMG Klinikum Sömmerda.

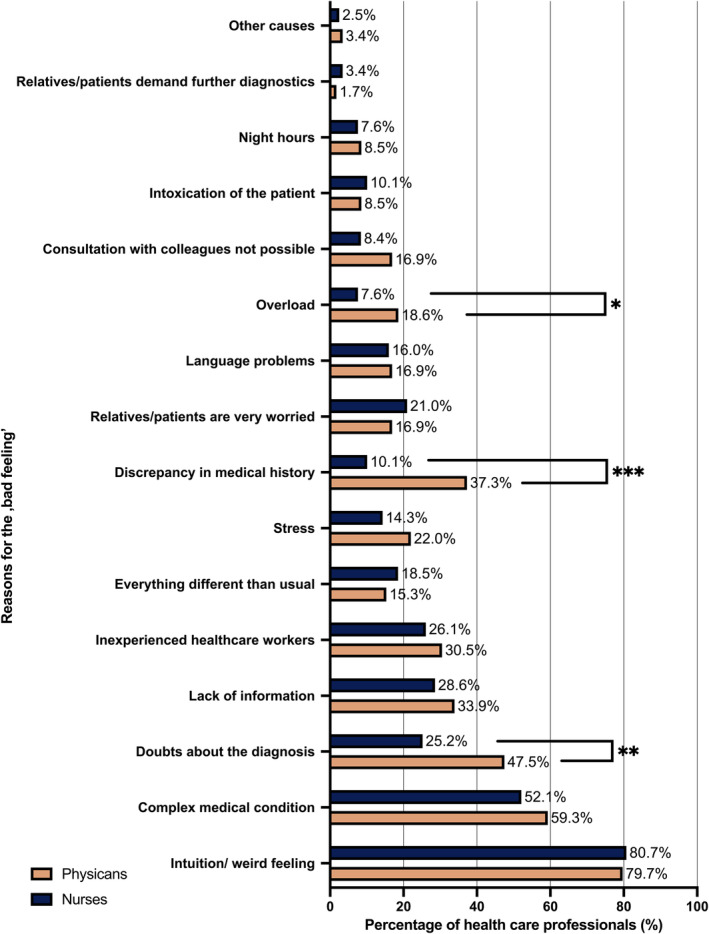

When participants were queried about the ‘bad feeling’ leading to an actual emergency, 4.6% indicated that this never occurred. A portion, 29.0%, reported it rarely leading to emergencies, while 43.3% said it occasionally did. Notably, 16.1% frequently found the ‘bad feeling’ evolving into an emergency, with no significant difference in responses between physicians and nurses (p = .98). The various reasons for the ‘bad feeling’ are detailed in Table 2 and Figure 3. Among these, notable causes included abnormal patient behaviour not aligning with diagnostic data, poor communication with colleagues and previous experiences. The distribution does not differ significantly between the University Medicine Greifswald and the KMG Klinikum Sömmerda (p = .83).

TABLE 2.

Reasons for the ‘bad feeling’.

| Answers | Percentage of cases (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent (%) | ||

| Intuition/weird feeling | 166 | 22.1 | 79.8 |

| Everything different than usual | 41 | 5.5 | 19.7 |

| Overload | 25 | 3.3 | 12.0 |

| Doubts about the diagnosis | 70 | 9.3 | 33.7 |

| Night hours | 17 | 2.3 | 8.2 |

| Stress | 38 | 5.1 | 18.3 |

| Relatives/patients are very worried | 35 | 4.7 | 16.8 |

| Relatives/patients demand further diagnostics | 6 | 0.8 | 2.9 |

| Language problems | 34 | 4.5 | 16.3 |

| Complex medical condition | 115 | 15.3 | 55.3 |

| Discrepancy in medical history | 36 | 4.8 | 17.3 |

| Lack of information | 68 | 9.0 | 32.7 |

| Consultation with colleagues not possible | 23 | 3.1 | 11.1 |

| Inexperienced healthcare workers | 53 | 7.0 | 25.5 |

| Alcohol, medication or drug abuse | 20 | 2.7 | 9.6 |

| Other causes | 5 | 0.7 | 2.4 |

| Total | 752 | 100.0 | 361.5 |

FIGURE 3.

Reason for ‘bad feeling’ as a percentage per health care professional. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.4. Responses to the ‘Bad Feeling’

Participants in this study had the option to provide multiple responses regarding their reactions to the ‘bad feeling’. The comparison between physicians and nurses revealed varied reactions. A minority, comprising two physicians (3.3%) and two nurses (1.6%), admitted to ignoring the feeling, with no significant difference between the groups (p = .32). In contrast, a substantial majority, including 75% of physicians and 85.2% of nurses, indicated they would intensify patient observation (p = .23). A significant number of participants, 61.7% of physicians and 53.3% of nurses, mentioned they would re‐evaluate the objective criteria (p = .29). Consulting other specialist colleagues was a common response, chosen by 58.2% of physicians and 71.3% of nurses (p = .13). Informing other specialists was similarly prevalent, with 45% of physicians and 45.9% of nurses choosing this option (p = 1.0). Notably, initiating further diagnostics was more common among physicians (58.0%) compared to nurses (9.0%), a difference that was statistically significant (p < .001). The response to the ‘bad feeling’ does not differ significantly (p = .89) between the two hospitals.

4. DISCUSSION

This study was designed to explore the subjective experience of the ‘bad feeling’ among healthcare professionals across two hospitals, focusing on its potential influence on patient care. The findings offer significant insights into how often this feeling occurs, its characteristics, underlying causes and its consequences within the realm of patient care. The concept of a ‘bad feeling’ is a kind of intuition, often referred to as a ‘gut feeling’, which healthcare professionals experience in clinical settings. This intuitive sense can alert them to potential issues that may not be immediately evident through objective measures. Understanding this phenomenon is crucial, as it can significantly impact decision‐making processes and patient outcomes.

4.1. Frequency and association with professional experience

The data indicate that the ‘bad feeling’ is a common occurrence among healthcare professionals, with approximately 70% of participants reporting it occasionally or frequently. This aligns with existing literature, which has similarly identified the ‘gut feeling’ as a prevalent phenomenon in clinical settings (Oliva et al., 2016; Stolper et al., 2009). The research findings revealed a significant positive correlation between the frequency of experiencing the ‘bad feeling’ and the healthcare professionals' work experience, indicating that increased professional experience enhances awareness and sensitivity to this phenomenon (p < .001). This observation is consistent with the findings of McCutcheon et al., who conceptualise intuition as a fusion of expertise, knowledge and experience (McCutcheon & Pincombe, 2001; Smith et al., 2020).

4.2. Quality and impact of the ‘bad feeling’

Evaluating the perceived helpfulness and potential hindrance of the ‘bad feeling’ has yielded important insights into its role in clinical decision‐making. A significant majority, nearly 80%, of the participants viewed the ‘bad feeling’ as beneficial either occasionally or often in their practice, whereas only about 20% regarded it as a hindrance in the same frequency. Notably, 60% of the respondents identified the ‘bad feeling’ as a frequent forewarning of emergent situations, suggesting its utility as an early indicator of changing patient conditions. This is in line with the research by Cabrera et al., which demonstrated a nearly 80% accuracy in assessing a patient's condition correctly based on initial impressions and vital signs alone, thus underscoring the practical value of the ‘bad feeling’ in clinical contexts (Cabrera et al., 2015). General practitioners commonly regard the ‘gut feeling’ as a valuable tool in patient care, acknowledging its utility in clinical decision‐making (Hull, 1985; Oliva‐Fanlo et al., 2022). Additionally, concerns for a patient's well‐being, often a component of the ‘bad feeling’, are considered significant. Such concerns not only underscore the clinical relevance of these intuitive feelings but are also used as key alerting criteria by Medical Emergency Teams (MET). This further highlights the essential role of subjective perceptions in ensuring patient safety and effective healthcare delivery (Bagshaw et al., 2010; Bingham et al., 2015).

4.3. Causes and impacts of the ‘bad feeling’

This study reveals that the ‘bad feeling’ experienced by healthcare professionals stems from various factors. Predominantly, intuition or an indistinct sense of concern was identified as the cause in nearly 80% of cases. This aligns with the findings of Melin‐Johansson et al., who describe intuition as a complex and significant aspect of clinical judgement (Melin‐Johansson et al., 2017). Additionally, this study indicates that doubts about diagnoses, complex medical conditions and insufficient information frequently contribute to the emergence of the ‘bad feeling’ underscoring its multifaceted nature. Similarly, Donker et al. demonstrate in their study the multifaceted determinants of ‘gut feeling’ in the diagnosis of cancer by general practitioners. These determinants are analogous to those identified in our study, including patient history and abnormal test results (Donker et al., 2016).

The repercussions of the ‘bad feeling’ are equally diverse. The majority of healthcare professionals reported that this sensation prompted them to take specific actions, such as enhancing patient observation, reassessing objective criteria and seeking consultation or notifying colleagues. Van den Bruel et al.'s recommendations for further diagnostic measures in response to a ‘gut feeling’ corroborate this approach (Bruel et al., 2012). Similarly, Turnbull et al. advocate for enhanced patient observation and consultation, in alignment with recommendations for further diagnostic measures in response to intuitive feelings (Turnbull et al., 2018). Remarkably, only a small number of professionals chose to disregard these intuitive concerns. It is noteworthy that the pursuit of additional diagnostic procedures was more common among physicians than nurses, which likely reflects the regulatory framework in Germany, where only physicians are authorised to initiate and approve further diagnostics.

4.4. Enhancing patient care through acknowledgement of the ‘bad feeling’

Recognising and valuing the ‘bad feeling’ is crucial in patient care, as it often signals potential deteriorations in a patient's condition. Intuition has been demonstrated to be an independent predictor of clinical intervention and patient mortality rates (de Groot et al., 2014). Healthcare professionals, especially those in leadership roles, need targeted training to effectively interpret and respond to these intuitive signals. Open communication and collaborative assessment of the ‘bad feeling’ within the medical team are essential steps towards enhancing patient safety.

Additionally, developing practical tools such as pocket maps that outline common triggers of the ‘bad feeling’ and suggest appropriate responses can greatly aid healthcare providers. These resources can act as quick reference guides in clinical settings, facilitating prompt recognition and action. The successful implementation of checklists in various medical areas further validates the effectiveness of such tools in improving patient care (Boyd et al., 2017).

4.5. Study limitations

A notable limitation of this study is the ambiguous nature of the ‘bad feeling’. The lack of a universally accepted definition could lead to inconsistencies in how participants understand and describe their experiences. Although the questionnaire provided an open‐ended option labelled ‘Other reasons’ for respondents to specify alternative causes of ‘bad feeling’, the formulation of this question may not have been clear enough to elicit detailed responses, which could affect the depth and accuracy of the data collected. Additionally, the reliance on self‐reported data may introduce subjective biases and affect the accuracy of recall. While the sample size was adequate for statistical analysis, it may not be large enough to ensure the findings are representative of all healthcare professionals, given the variety of specialties and levels of experience. The over‐representation of nursing staff in the study population was a further limitation. This study's focus on only two hospital environments also potentially limits the applicability of its conclusions to a wider healthcare context. However, despite these limitations, the core findings and insights of the study are likely to be relevant and applicable in practical settings.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This study sheds light on the ‘bad feeling’ experienced by healthcare professionals and its prevalence in clinical settings. The findings reveal a noteworthy correlation between the occurrence of the ‘bad feeling’ and the healthcare professionals' years of experience, suggesting its increased recognition with greater clinical exposure. Notably, over half of the participants reported that the ‘bad feeling’ often or occasionally precedes critical developments in a patient's condition, leading to emergency situations.

These results underscore the ‘bad feeling’ as a significant and frequently encountered aspect of clinical practice, emphasising its importance in patient care. This study advocates for the integration of this concept into routine clinical practices, potentially through enhanced educational programmes, training workshops and the use of practical tools like pocket cards.

As we look to the future, it becomes imperative to explore deeper into understanding the ‘bad feeling’ phenomenon, focusing on its implications for both patient outcomes and the decision‐making processes of healthcare professionals.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CRH has contributed to: Conceptualisation, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, project administration, final approval and agreement. JL has contributed to: Validation, investigation, writing—review and editing and final approval and agreement. ST has contributed to: Validation, investigation, writing—review and editing and final approval and agreement. AB has contributed to: Conceptualisation, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing, project administration and final approval and agreement.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee in Greifswald on 12 December 2022 under registration number BB170/22. In addition, the Ethics Committee of the Medical Association of Thuringia approved the study for the KMG Klinikum Sömmerda under registration number 76776/2023/12.

Supporting information

Appendix S1.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly, we thank all participants. We also thank the KMG Klinikum Sömmerda and explicitly MD Axel Plessmann and Dr. med. Peter Brand. Finally, we also thank Alexander Ruback from the Patient Safety and Quality division for providing the survey software. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Hölzing, C. R. , van der Linde, J. , Kersting, S. , & Busemann, A. (2025). Prevalence and characteristics of the ‘bad feeling’ among healthcare professionals in the context of emergency situations: A Bi‐Hospital Survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 34, 507–516. 10.1111/jocn.17374

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Bagshaw, S. M. , Mondor, E. E. , Scouten, C. , Montgomery, C. , Slater‐MacLean, L. , Jones, D. A. , Bellomo, R. , Noel Gibney, R. T. , & for the Capital Health Medical Emergency Team Investigators . (2010). A survey of nurses' beliefs about the medical emergency team system in a Canadian tertiary hospital. American Journal of Critical Care, 19(1), 74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beglinger, B. , Rohacek, M. , Ackermann, S. , Hertwig, R. , Karakoumis‐Ilsemann, J. , Boutellier, S. , Geigy, N. , Nickel, C. , & Bingisser, R. (2015). Physician's first clinical impression of emergency department patients with nonspecific complaints is associated with morbidity and mortality. Medicine, 94, e374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beil, M. , Sviri, S. , Flaatten, H. , De Lange, D. W. , Jung, C. , Szczeklik, W. , Leaver, S. , Rhodes, A. , Guidet, B. , & van Heerden, P. V. (2021). On predictions in critical care: The individual prognostication fallacy in elderly patients. Journal of Critical Care, 61, 34–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, G. , Fossum, M. , Barratt, M. , & Bucknall, T. K. (2015). Clinical review criteria and medical emergency teams: Evaluating a two‐tier rapid response system. Critical Care and Resuscitation, 17(3), 167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, J. M. , Wu, G. , & Stelfox, H. T. (2017). The impact of checklists on inpatient safety outcomes: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 12(8), 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruel, A. V. , Thompson, M. , Buntinx, F. , & Mant, D. (2012). Clinicians' gut feeling about serious infections in children: Observational study. BMJ. British Medical Journal, 345, e6144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, D. , Thomas, J. F. , Wiswell, J. L. , Walston, J. M. , Anderson, J. R. , Hess, E. P. , & Bellolio, F. (2015). Accuracy of ‘my gut feeling:’comparing system 1 to system 2 decision‐making for acuity prediction, disposition and diagnosis in an academic emergency department. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 16(5), 653–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargahi, H. , Monajemi, A. , Soltani, A. , Hossein Nejad Nedaie, H. , & Labaf, A. (2022). Anchoring errors in emergency medicine residents and faculties. Medical journal of the Islamic Republic of. Iran, 36(1), 941–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, N. , van Oijen, M. , Kessels, K. , Hemmink, M. , Weusten, B. , Timmer, R. , Hazen, W. L. , van Lelyveld, N. , Vermeijden, J. R. , Curvers, W. L. , Baak, L. C. , Verburg, R. , Bosman, J. H. , de Wijkerslooth, L. R. H. , de Rooij, J. , Venneman, N. G. , Pennings, M. , van Hee, K. , Scheffer, R. C. H. , … Bredenoord, A. J. (2014). Prediction scores or gastroenterologists' gut feeling for triaging patients that present with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. United European Gastroenterology Journal, 2(3), 197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donker, G. A. , Wiersma, E. , van der Hoek, L. , & Heins, M. (2016). Determinants of general practitioner's cancer‐related gut feelings—A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open, 6(9), e012511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigerenzer, G. , & Gaissmaier, W. (2011). Heuristic decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 451–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigerenzer, G. , & Gigerenzer, G. (2015). 107Heuristic decision making. In Simply rational: Decision making in the real world. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, P. , Abdi, A. , Jalali, R. , & Salari, N. (2016). The perception of intuition in clinical practice by Iranian critical care nurses: A phenomenological study. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 9, 31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull, F. M. (1985). The consultation process. In Decision‐making in general practice (pp. 13–26). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen, J. S. , Bowen, J. L. , de Bruin, A. B. H. , Regehr, G. , & Teunissen, P. W. (2020). “I was worried about the patient, but I Wasn't feeling worried”: How physicians judge their comfort in settings of uncertainty. Academic Medicine, 95(11S), S67–S72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosowski, M. M. , & Roberts, V. W. (2003). When protocols are not enough. Intuitive decision making by novice nurse practitioners. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 21(1), 52–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski, D. , Hutchinson, M. , Hurley, J. , Rowley, J. , & Sutherland, J. (2017). The role of emotion in clinical decision making: An integrative literature review. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon, H. H. I. , & Pincombe, J. (2001). Intuition: An important tool in the practice of nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 35(3), 342–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melin‐Johansson, C. , Palmqvist, R. , & Rönnberg, L. (2017). Clinical intuition in the nursing process and decision‐making—A mixed‐studies review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23–24), 3936–3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, G. (2009). Dual processing and diagnostic errors. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14, 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, G. R. , & Eva, K. W. (2010). Diagnostic error and clinical reasoning. Medical Education, 44(1), 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, B. , March, S. , Gadea, C. , Stolper, E. , & Esteva, M. (2016). Gut feelings in the diagnostic process of Spanish GPs: A focus group study. BMJ Open, 6(12), e012847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva‐Fanlo, B. , March, S. , Gadea‐Ruiz, C. , Stolper, E. , Esteva, M. , & On behalf of the Cg. (2022). Prospective observational study on the prevalence and diagnostic value of general Practitioners' gut feelings for cancer and serious diseases. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(15), 3823–3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman, M. (2004). An evaluation of dual‐process theories of reasoning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 11(6), 988–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomare, C. , Churruca, K. , Ellis, L. A. , Long, J. C. , & Braithwaite, J. (2019). A revised model of uncertainty in complex healthcare settings: A scoping review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 25(2), 176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C. F. , Drew, S. , Ziebland, S. , & Nicholson, B. D. (2020). Understanding the role of GPs' gut feelings in diagnosing cancer in primary care: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of existing evidence. British Journal of General Practice, 70(698), e612–e621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolper, E. , Van Royen, P. , Van de Wiel, M. , Van Bokhoven, M. , Houben, P. , Van der Weijden, T. , & Jan Dinant, G. (2009). Consensus on gut feelings in general practice. BMC Family Practice, 10(1), 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, S. , Lucas, P. J. , Redmond, N. M. , Christensen, H. , Thornton, H. , Cabral, C. , Blair, P. S. , Delaney, B. C. , Thompson, M. , Little, P. , Peters, T. J. , & Hay, A. D. (2018). What gives rise to clinician gut feeling, its influence on management decisions and its prognostic value for children with RTI in primary care: A prospective cohort study. BMC Family Practice, 19(1), 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.