Abstract

Background

Acute pulmonary embolism (PE) is a serious and potentially fatal condition that is relatively rare in the pediatric population. In patients presenting with massive/submassive PE, catheter-directed Therapy (CDT) presents an emerging therapeutic modality by which PE can be managed.

Methods

Electronic databases were systematically searched through May 2024. This systematic review was performed in line with recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement guidelines and was registered in PROSPERO (Reg. no. CRD42024534229).

Results

Sixteen case reports/series were included in the quantitative analysis with a total population of 40 children diagnosed with PE. Of them, 21 were females and 19 were males. Massive PE was diagnosed in 15 patients and submassive PE was diagnosed in 17 patients. Complete resolution of PE happened at a rate of 68% (95%CI = 46–80%). Mortality was encountered at a rate of 18% (95%CI = 0.7–36%). PE recurred after CDT at a rate of 15% (95%CI = 2–28%). Non-major bleeding complicated CDT at a rate of 46% (95%CI = 25–66%, p = 0.163).

Conclusion

CDT can be utilized in the management of PE in children as a potential therapeutic option for selected patients. While the results of CDT interventions for pediatric PE are promising, further research -including well-conducted cohort studies- is required to validate those results.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12959-024-00674-9.

Introduction

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a life-threatening condition that arises when a blood clot obstructs a pulmonary artery, impeding blood flow to the lungs. This condition is often associated with significant morbidity and mortality, particularly when not promptly diagnosed and treated. While PE is well-documented in adults, its occurrence in the pediatric population is relatively rare, leading to limited data and a lack of standardized treatment protocols for children [1]. The incidence of pediatric PE is estimated to be approximately 0.9 per 100,000 children per year, significantly lower than in adults, yet the consequences can be equally severe [2].

Historically, the management of pediatric PE has been extrapolated from adult treatment guidelines, due to the paucity of pediatric-specific data. However, children are not simply small adults; they have unique physiological characteristics and disease etiologies that necessitate tailored therapeutic approaches [3]. This is particularly true for massive and submassive PE, which require urgent and effective intervention to restore perfusion and prevent catastrophic outcomes. Traditional treatment options include systemic anticoagulation with agents such as heparin, followed by long-term anticoagulation therapy. Despite their efficacy, these treatments come with significant risks, including bleeding complications, which are especially concerning in the pediatric population [4].Catheter-directed therapy (CDT) has emerged as a promising alternative to systemic thrombolysis, offering targeted delivery of thrombolytic agents directly to the site of the clot. This approach aims to maximize clot dissolution while minimizing systemic exposure and associated risks [5]. In adults, CDT has shown favorable outcomes in terms of clot resolution and survival rates, prompting interest in its potential application for pediatric patients [6]. However, the rarity of pediatric PE and the inherent challenges of conducting large-scale clinical trials in children have resulted in a reliance on case reports and small case series to guide clinical practice [7].

A systematic review and meta-analysis of CDT in pediatric PE can provide crucial insights into its efficacy and safety, addressing the gap in large-scale clinical data. In the past decade, there have been significant advancements in the techniques and technologies used in CDT, making it a viable option even for younger patients. The American Heart Association reports that PE accounts for approximately 10% of all acute pediatric hospital admissions for venous thromboembolism (VTE), underscoring the importance of effective treatment modalities [8]. Moreover, recent data suggest that obesity, a rising concern in pediatric health, is a significant risk factor for PE, further highlighting the need for effective interventions [6].

These findings highlight the potential of CDT as a viable treatment option for pediatric PE, offering substantial rates of thrombus resolution with manageable complication rates. However, the reliance on case reports and small case series indicates a pressing need for larger, controlled studies to validate these outcomes and refine treatment protocols. The synthesis of current evidence provided by this review serves as a foundational step towards improving the management of this critical condition in children.

Methods

We performed the current systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement guidelines and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.3 [9]. Our study protocol was registered in PROSPERO (ID: CRD42024534229).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

The study population comprised pediatric patients (aged ≤ 21 years) diagnosed with pulmonary embolism.

The intervention included the use of catheter-directed Therapy.

The study reported on outcomes such as thrombus resolution, mortality, recurrence of PE, bleeding complications, or hospital stay duration.

Exclusion criteria were:

Studies involving adult populations or mixed populations where pediatric data could not be disaggregated.

Studies without original data (e.g., reviews, editorials, and opinion pieces).

Studies lacking detailed outcome measures relevant to the review.

Literature search

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify studies reporting on the use of catheter-directed therapy (CDT) for treating pulmonary embolism (PE) in pediatric patients. Databases searched included PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library, covering publications up to May 2024. The search terms used were a combination of “catheter-directed therapy,” “pulmonary embolism,” “pediatric,” “children,” and “thrombolytic therapy.” Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to refine the search. The search was limited to articles published in English. Reference lists of relevant articles and reviews were also screened to identify additional studies.

Study selection

We removed all duplicates using Endnote software (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA). To assess their eligibility criteria, all retrieved records were screened by two independent authors. The process included title and abstract screening, followed by full-text screening. Additionally, references of the included studies were reviewed and considered if they met our criteria.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts for relevance. Full-text articles of potentially eligible studies were then retrieved and assessed for inclusion based on the criteria mentioned above. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third reviewer.

Data extracted from each study included:

Study design (case report, case series, observational study).

Demographic information (age, sex).

PE characteristics (massive, submassive, bilateral, unilateral).

Risk factors for PE (e.g., obesity, lower limb deep vein thrombosis).

Details of the CDT procedure (thrombolytic agents used, duration of therapy).

Outcomes (thrombus resolution, mortality, PE recurrence, bleeding complications, hospital stay duration).

Definitions

CDT was defined as either catheter-directed thrombolysis or thrombectomy. Complete resolution of thrombus was defined as no residual thrombus in the arterial lumen seen in angiography. Partial resolution of thrombus was detected when main branches of pulmonary artery are patent and peripheral branches are still occluded. Adverse bleeding events were defined according to the Perinatal and Paediatric Haemostasis Subcommittee of ISTH [10]. Major bleeding according to ISTH is defined as fatal bleeding or symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ and/or bleeding causing a drop in the hemoglobin levels of 2 g/dl or greater. Minor bleeding is defined as any bleeding that does not meet the mentioned definition.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of included studies was evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI Reference)) Critical Appraisal Tools for case reports and case series. The assessment focused on the clarity of patient demographics, the comprehensiveness of case description, and the thoroughness of outcome reporting. Each study was rated as good, fair, or poor quality based on these criteria (Supplementary Tables 1, 2).

Statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were conducted to pool data on thrombus resolution rates, mortality, PE recurrence, and bleeding complications. Heterogeneity a studies was assessed using the I² statistic, with values of 0% indicating no heterogeneity. A fixed-effect model was used for the meta-analysis due to the low heterogeneity observed in the included studies. Pooled estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each outcome.

All statistical analyses were performed using RevMan software (version 5.4). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the results, excluding studies of lower quality or those with small sample sizes to determine their impact on the overall findings.

Results

Study selection

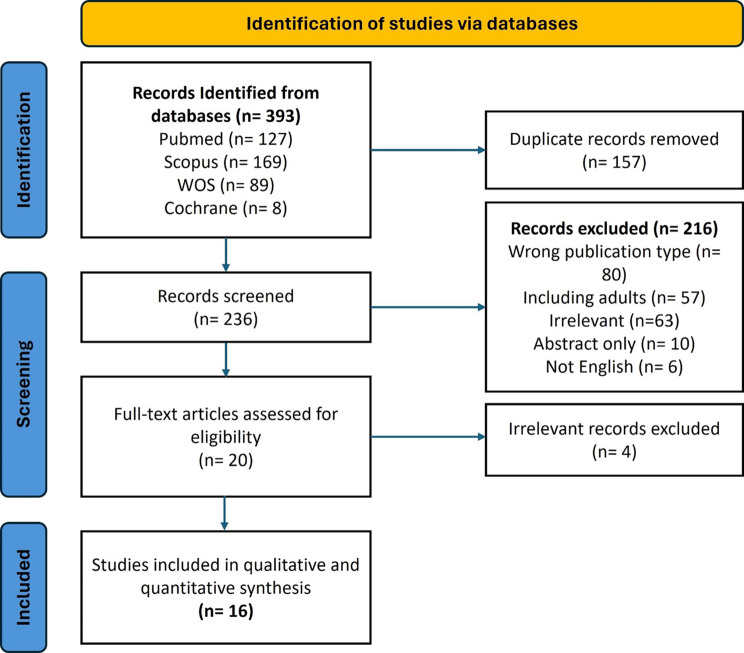

We retrieved 393 records from the literature search. After removing the duplicates, a total of 236 articles were assessed for eligibility, ending with 16 articles included in the analysis. The details of the selection process are demonstrated in the PRISMA flow chart Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The PRISMA chart illustrating the relevant study screening process

Study characteristics

We included 16 studies with a total population sample of 40 cases. Of these, four case series and 12 case reports were included. Our study population comprised 21 females and 19 males, 9 children and 31 adolescents, diagnosed with massive (n = 15) or submassive (n = 17) pulmonary embolism. Bilaterally locating PE (n = 26) predominated over unilaterally locating ones (Right = 11, Left = 5). The characteristics of the included studies and the procedural details reported in the studies are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary of the included studies in the review

| Study ID | Study design | Country | No. of cases | Gender | Age | Risk factors | Thrombophilia profile | Presenting symptoms | Imaging modality used for diagnosis | Location of PE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akam-Venkata et al., 2018 [33] | Case series | United States | 9 | 6 F/3 M | 16 (12–20) | -Recent immobility (5/9) -Oral contraceptive use (4/9) -Underlying haematological diseases (3/9) -Systemic lupus erythematosus (2/9) | N/A | N/A | CTA | -Bilateral PE (5/9) -Unilateral PE (4/9) |

| Bavare et al., 2014 [34] | Case series | United States | 5 | 4 F/1 M | 16.5 (11–17) | -Previous DVT (2/5) -Current DVT (2/5) -Obesity (2/5) -Thrombophilia (3/5) -Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (1/5) | -Factor V Leiden mutation (1/5) -Elevated factor VIII (1/5) -Antiphospholipid syndrome (1/5) | N/A | CTA or conventional angiography | -Bilateral PE (2/5) -Right pulmonary artery (1/5) Main pulmonary artery (1/5) -Segmental PE (1/5) |

| Beitzke et al., 1996 [35] | Case report | Austria | 1 | F | 3 yrs | Congenital heart disease (double-inlet left ventricle and pulmonary atresia) | N/A | Profound cyanosis and syncope | Conventional angiography | Unilateral PE with a thrombus completely occluding the left lower lobe artery |

| Belsky et al., 2019 [36] | Case series | United States | 5 | 3 M/2F | 12 (3–21) yrs | Pregnancy, DKA (1/5) Central venous line, pneumonia (1/5) Smoking, OCP, obesity, postpartum (1/5) | Factor V Leiden (1/5) Antithrombin deficiency and antiphospholipid syndrome (1/5) | Chest pain (5/5) Shortness of breath (3/5) Syncope (2/5) Dizziness (1/5) Palpitations (1/5) | CTA | Bilateral PE in 3 patients and right main PE in 2 patients |

| Cannizzaro et al., 2005 [19] | Case series | Switzerland | 1 | F | 10 yrs | Recent immobility, DVT, OCP | N/A | Mild chest pain and shortness of breath | V/Q scan | Bilateral PE |

| Chan et al., 2022 [13] | Case report | United States | 1 | M | 17 yrs | Obesity | Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) mutation with elevated homocysteine, FVIII, and plasminogen activator inhibitor–1 (PAI-1) heterozygous mutation | Chest pain and shortness of breath | CTA | Bilateral PE (extensive clot burden bilaterally in all five lobes with evidence of increased right ventricle to left ventricle ratio) |

| Claveria et al., 2013 [37] | Case report | United States | 1 | M | 17 yrs | Trauma | N/A | Hemorrhagic shock due to gunshot wound to the right upper quadrant of the abdomen resulting in right hepatic and renal lacerations. | CTA | Unilateral PE involving the right main pulmonary artery, right upper and lower lobe arteries, and segmental branches of the lingula and left lower lobe |

| Feldman et al., 2005 [38] | Case report | United States | 1 | M | 2 days | Congenital heart disease (pulmonary atresia) Cardiac surgery (right ventricular outflow tract reconstruction) | N/A | difficulty weaning from mechanical ventilation with decreased oxygen saturation and CO2 retention post-operatively. | V/Q scan | Unilateral PE involving the right lower lobe pulmonary artery |

| Hirschbaum et al., 2021 [39] | Case report | United States | 1 | M | 21 yrs | COVID-19 infection | N/A | cough, fevers, shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, dizziness with near syncope as well as acutely worsened dyspnoea | CTA | Bilateral PE |

| Hubara et al., 2021 [40] | Case report | Israel | 1 | M | 8 months | Congenital heart disease (hypoplastic left heart syndrome) | N/A | electively admitted for bidirectional Glenn procedure | Cardiac catheterization | Unilateral PE (left pulmonary artery) |

| Ji et al., 2020 [41] | Case series | United States | 9 | 5 F/4 M | 13.9 (6–19) yrs |

-DVT (2/9) -OCP (3/9) -Obesity (3/9) Hypercoagulable state (2/9) |

-ATIII deficiency (1/9) | Dyspnea and chest pain were the most common chief complaints. | CTA | -Bilateral PE (6/9)-Right pulmonary artery (2/9) -Left pulmonary artery (1/9) |

| Kajy et al., 2019 [42] | Case report | United States | 1 | M | 12 yrs | Hereditary spherocytosis and splenectomy | N/A | Chest pain, hemoptysis, and dyspnea for 1 day | CTA | Unilateral PE with a large thrombus in the right main pulmonary artery extending into the segmental branches of the right upper, middle, and lower lobes |

| Ruud et al., 2003 [43] | Case report | Norway | 1 | M | 12 yrs | complex congenital heart defects defined as tricuspid atresia, ventricular septal defect and transposition of the great arteries | N/A | Chest pain and dyspnoea | CTA | Unilateral PE completely obstructing flow to the left lung |

| Stępniewski et al., 2023 [44] | Case report | Poland | 1 | F | 16 yrs | OCP | N/A | Syncope, dyspnea, and chest discomfort. | CTA | Bilateral, proximal PE |

| Sur et al., 2007 [31] | Case report | United States | 1 | M | 10 yrs | -DM type 1 admitted with hyperglycemic, hyperosmolarcoma with associated cerebral edema-Immobility-DVT | N/A | Syncope, dyspnea, and chest discomfort. | CTA | Bilateral PE extending into the fifth and sixth generation pulmonary artery divisions |

| Visveswaran et al., 2020 [45] | Case report | United States | 1 | F | 12 yrs | -Phlegmasia cerulea dolens-COVID-19 infection | Elevated Factor VIII activity | hypotension, bradycardia, and pulseless electrical activity following mechanical thrombectomy for the management of phlegmasia cerulea dolens | Conventional angiography | Bilateral PE with extensive emboli in the superior, middle, and inferior segments of the right lung; the lingular segment of the left lung; and interlobular pulmonary arteries. |

PE: pulmonary embolism, M: male, F: female, yrs: years, DVT: deep vein thrombosis, CTA: computed tomography angiography, V/Q scan: ventilation-perfusion scan, OCP: oral contraceptive, DM: diabetes mellitus, AT III: Antithrombin III

Table 2.

Details of the operative and clinical data reported in the included studies

| Study ID | Indication for CDT | Catheter system | CDT tPA dose and duration | Procedure description | Preceding systemic thrombolysis? | Respiratory/hemodynamic support? | Anticoagulation type | Bleeding events? | Main results of intervention | Length of follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akam-Venkata et al., 2018 [33] | N/A | EkoSonic endovascular system | 10–51 mg | The EkoSonic infusion catheter was positioned via the femoral, internal jugular, or brachial vein approach using a 6-Fr sheath. The ultrasonic core was inserted into the infusioncatheter. Then the patients were monitored in the ICU, while the EkoSonic endovascular system delivered the ultrasoundaccelerated thrombolysis. Tissue plasminogen activator was administered as an initial bolus dose of 2 mg followed by an infusion at the rate of 1 mg/hour through the infusion catheter. During the ultrasound-accelerated fibrinolysis, normal saline was given to cool the EkoSonic ultrasonic core at the rate of 35 ml/hour through each EkoS infusion catheter. Concomitant low-dose intravenous heparin was given at 500 units/hour during EkoS therapy. | 3/9 | Yes (3/9) | -Intravenous heparin (9/9) | Minimal gastrointestinal bleeding in 2 patients | A total of seven patients responded to catheter-directed therapy and concomitant anticoagulation therapy using intravenous heparin infusion. | 11 months (median) |

| Bavare et al., 2014 [34] | The indication for CDT was massive or submassive PE as defined by the presence of either hypotension or severe right ventricular (RV) dysfunction in the setting of complete occlusion of the main or major branch pulmonary arteries. | EkoSonic Endovascular Lysus system | 0.75-2 mg/h | Each CDT intervention was performed with ultrasound-guided accessof femoral vein through which a catheter (5–7 F) was placed in the affected PA. For bilateral PE, catheters were parked in the right and left main PAs, and for unilateral PE, the catheter was parked in the occluded main branch PA. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was delivered at the thrombus site. UCDT involved ultrasonic pulses delivered by EKOS endowave system along with targeted delivery of tPA. All patients received thrombolytic infusion of tPA (0.75e2 mg/hr per catheter port) with the catheters left in situ for 24 h. | 1/5 | Yes (2/5) |

-UFH (4/5) -LMWH (1/5) |

N/A | Complete resolution of thrombus was demonstrated after 4 interventions (67%) and partial resolution occurred in 2 instances. | N/A |

| Beitzke et al., 1996 [35] | N/A | N/A | 0.05 mg/kg/h | Transcatheter lysis with rt-PA 0.05 mg/kg per hour was performed for 12 hours. A second angiography showed no change in size or location of the thrombus and a higher dose of rt-PA using a bolus of 0.25 mg/kg and a continuous infusion of 0.05 mg/kg per hour were tried over a 6-hour period. A repeat angiogram showed canalization of the thrombus along the catheter course and opacification of the left lower lobe. Using a 0.5 mg/kg loading dose of rt-PA together with a continuous infusion in the above-mentioned dose over another 6 h we found the thrombus to have become smaller and mobile on day 3 of rt-PA therapy. Another therapy course was started but was discontinued after 3 h on day 4 when it was necessary to drain the large right-sided pleural effusion. Heparinization was continued over the next 3 days. A final angiogram on day 7 after admission showed the thrombus to have disappeared. | No | Yes | UFH with a bolus of 100 U/kg and continuous infusion of 20 U/kg per hour | N/A | A final angiogram on day 7 after admission showed the thrombus to have disappeared. | 8 months |

| Belsky et al., 2019 [36] | N/A | N/A | Dose: 0.03 mg/kg/h Duration: 11.5–72.5 | Upfront thrombolytic therapy consists of evacuation and reduction of acute intraluminal thrombus content via suction thrombectomy or mechanical clot disruption. Following clot reduction, an infusion catheter is placed into the artery for catheter-directed lysis. | No | N/A | LMWH | N/A | Four patients showed complete thrombus resolution, one showed partial resolution, and one has not undergone follow-up imaging. On follow-up screening echocardiogram, no patient had evidence of right ventricular hypertension suggestive of CTEPH. | 2.3–40.5 months |

| Cannizzaro et al., 2005 [19] | N/A | Tracker-18 Infusion Catheters, Boston Scientific Corporate, Natick, MA | 0.025 mg/kg/h for 32 h | Two 3 F end-hole catheters were advanced bilaterally to the clots, and thrombolytic therapy with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) was started with a local bolus injection of 0.03 mg/kg in the left pulmonary artery and 0.02 mg/kg in the right inferior lobe pulmonary artery, followed by a continuous infusion of 0.025 mg/kg/h in each pulmonary artery. | No | No | UFH | large inguinal hematoma at the access site in one patient | After discontinuation of rt-PA therapy, repeated pulmonary angiography revealed complete reperfusion of all lung segments. Right ventricular function had totally recovered. | 12 months |

| Chan et al., 2022 [13] | Massive PE | Triever24 aspiration catheter (Inari Medical, Irvine, CA, USA) | N/A (catheter-directed embolectomy) | A large volume of clot was retrieved with two suctions. The Triever24 aspiration catheter was retracted into the main pulmonary artery and a right lower lobe segmental pulmonary artery branch was selected using a Berenstein catheter and wire. After exchange for an Amplatz wire, the Triever24 aspiration catheter was advanced into the right main pulmonary artery. | No | Yes | UFH | N/A | Repeat pulmonary angiogram demonstrated only small residual nonocclusive subsegmental clots. Repeat pulmonary artery pressures demonstrated a significant decrease to 35/15 mmHg (mean 25 mmHg). The catheter and sheath were removed and hemostasis achieved. Afterward, oxygen requirements decreased from 100% non-rebreather to 2 l nasal cannula. IV epinephrine was discontinued. Repeat echocardiogram showed improved RV function | 3 months |

| Claveria et al., 2013 [37] | Hemodynamic instability and bleeding risk | N/A | 30 mg/h for 2 h | Under fluoroscopy, a catheter was inserted through the left subclavian vein with the tip seated in the right pulmonary artery. Treatment was infused over two hours, the typical interval cited in the guidelines for intra-arterial thrombolysis. During thrombolytic therapy, the patient required blood product transfusions for significant bleeding from his chest tube, intravenous catheter sites, and surgical drains | No | Yes | UFH | N/A | Repeat echocardiogram showed improved right ventricular strain. Inotropic support was discontinued two days after thrombolytic therapy, and the patient was eventually discharged home on warfarin | N/A |

| Feldman et al., 2005 [38] | High bleeding risk and young age. | AngioJet (Possis, Minneapolis, MN) catheter | N/A (catheter-directed thrombectomy) | A 0.014@ Hi-Torque Balance Middleweight Universal Guide Wire (Guidant, Indianapolis, IN) was placed in the distal right lower lobe pulmonary artery. Mechanical fragmentation was first performed with 3.0 and 4.0 mm Slalom angioplasty balloons (Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL). Considerable clot burden remained and oxygenation remained marginal. The short venous sheath was replaced with a 5 Fr long sheath (45 cm Check-Flo Performer Introducer sheath; Cook, Bloomington, IN) and positioned in the right lower lobe pulmonary artery. A 4 Fr AngioJet (Possis, Minneapolis, MN) was advanced through the long sheath and over the wire to the right lower pulmonary artery. | UFH | 30 ml of blood loss associated with the rheolytic process | Postintervention angiography showed excellent results with reconstitution of all major branches of the pulmonary artery and an increase in arterial saturation to 97%. | N/A | ||

| Hirschbaum et al., 2021 [39] | Massive PE | EKOSTM Endowave Infusion Catheter System | 1 mg/h per side over 6 h repeat CDT: 2 mg/h per side over 6 h | N/A | No | Yes | UFH | Right thigh haematoma on hospital Day 40 | Following CDT, the patient improved clinically and was transferred to the general medicine floor on hospital Day 3 with minimal supplemental oxygen | 4 months |

| Hubara et al., 2021 [40] | N/A | N/A | 0.2 mg/kg/hr for 24 h | An urgent catheterization was performed during which the LPA was recanalized using a glide catheter and 0.35” Terumo© glide wire with repeat manual suction of the thrombus. Surgical opinion was to avoid stenting the artery, so the catheter was left in situ in the thrombus for local administration of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) to be given for 24 h at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg/hr. | No | Yes | bivalirudin | mild bleeding at the sheath site | Successful thrombolysis | 3 weeks |

| Ji et al., 2020 [41] | PE symptom duration less than or equal to 14 days, massive or submassive PE present, RV/left ventricular (LV) diameter ratio greater than or equal to 0.9 on CT, or had a proximal PE. | A 4–5 F Unifuse (AngioDynamics, Latham, NY) infusion catheter | 0.03–0.06 mg/kg/hr with a maximum dose of 1 mg/ hr. | A 4–5 F Unifuse (AngioDynamics, Latham, NY) infusion catheter (either 10–20 cm infusion lengths, depending on the size of the patient) was advanced over the wire and positioned with the distal tip in the selected subsegmental PA. tPA was delivered through the infusion catheter into the PAs at a rate of 0.03–0.06 mg/kg/hr with a maximum dose of 1 mg/ hr. | No | Yes (9/9) | UFH or LMWH | N/A | Nine pediatric and adolescent patients underwent PA CDT, with clinical success achieved in seven patients (78%) following CDT alone. One patient subsequently required surgical thrombectomy of chronic thrombi in the setting of acute on chronic PE with severe pulmonary hypertension and one patient died from severe cardiopulmonary compromise with no substantial clinical improvement from CDT. All nine patients underwent technically successful CDT with complete or partial thrombus burden reduction observed in all cases. There were no procedural-related complications and no adverse events related to CDT. Post-CDT mean PA pressures demonstrated a statistically significant decrease from pre-CDT mean PA pressures. | 6 (2–9) months |

| Kajy et al., 2019 [42] | Massive PE | EkoSonic Endovascular System | 1 mg/hr for a total of 32 h | Catheter-directed thrombolysis was started by placing a 12 cm EkoSonic catheter into the main and middle right pulmonary artery. A 2.5 mg bolus of r-tPA was administered selectively, followed by a continuous 1 mg/hr r-tPA infusion for 8 h, yielding a total r-tPA dose of 10.5 mg. A second course of catheterdirected thrombolysis was administered using a similar 12 cm EkoSonic catheter. A total of 25 mg of r-tPA was administered: 2 mg during the first hour, followed by 1 mg/hr for the next 23 h. | No | No | UFH | N/A | Follow-up right heart catheterization confirmed marked hemodynamic improvement, with pulmonary artery pressure of 41/16 mmHg, mean 25 mmHg. Pulmonary angiogram showed markedly improved flow to the pulmonary artery. Clinically, the patient had resolution of hypoxia and tachycardia. He did not experience any bleeding throughout the 2 courses of catheter-directed thrombolysis. | More than 1 year. |

| Ruud et al., 2003 [43] | Massive PE | N/A | 0.016/kg/h for 6 days | A catheter was inserted via the femoral vein and positioned in the left pulmonary artery, with the tip inside the thrombotic mass. Without an initial bolus, continuous infusion of low-dose alteplase (Actilyse, Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany) was started. Initially, the dose was 0.008 mg/kg/h, but the day after admission the patient’s angiogram was unchanged at a D-dimer level of 10.6 mg/L. Thus, the dose was doubled to 0.016 mg/kg/h and continued for five days. | Yes (alteplase) | No | slight tendency to bleed at puncture sites | N/A | There was a gradual resolution of the thrombus, and after five days of continuous infusion the thrombus disappeared | N/A |

| Stępniewski et al., 2023 [44] | Massive PE not responding to oral anticoagulation for 24 h | Penumbra Lightning 12 system | cumulative alteplase dose of 20 mg delivered over 10 h after embolectomy | Urgent percutaneous embolectomy with the Penumbra Lightning 12 system was performed, which evacuated a substantial thrombus and improved the mean PA pressure (mPAP) measured invasively from 34 to 32 mm Hg and the cardiac index (CI) from 1.48 to 1.58 l/min/m2. To optimize the effect of embolectomy, we decided to supplement it with bilateral low-dose-local-thrombolysis with a cumulative alteplase dose of 20 mg delivered over 10 h. | No | No | UFH | N/A | The procedure resulted in reduction in mean PA pressure (mPAP) to 21 mm Hg, an increase in cardiac index to 2.38 l/min/m2, improvement in symptoms and vital signs, and reduction in N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels to 1608 pg/ml. | N/A |

| Sur et al., 2007 [31] | Massive PE and contraindicated systemic thrombolysis due to cerebral edema | Rheolytic thrombectomy was performed initially using an Angiojet1 Xpeedior1 (Possis Medical, Minneapolis, MN) and subsequently an Angiojet1 DVXTM catheter (Possis Medical, Minneapolis, MN). | N/A (catheter-directed thrombectomy) | Care was taken to perform brief runs of thrombectomy of less than 10 s to avoid significant bradycardia and hypotension. In addition, we restricted the use of the Angiojet1 catheter to vessels greater than 6 mm in diameter. Thrombectomy was performed first in the inferior dorsal and inferior ventral branches of the lower lobe and then in the superior dorsal branch of the left pulmonary artery. These branches were chosen as they contained the maximum thrombus burden | No | Yes (mechanical ventilation and vasopressor support with dobutamine) | LMWH | N/A | There was a significant improvement in the patient’s hemodynamics following thrombectomy in the left pulmonary artery with a postprocedure heart rate of 122 bpm and reduced pulmonary artery pressures of 41/25, (31) mm Hg. | N/A |

| Visveswaran et al., 2020 [45] | Massive PE | EkoSonic UCDT catheters | 1 mg/lung/hour for 6 h (12 mg total dose) | Bilateral UCDT catheters infusing tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) at 1 mg/lung/hour for 6 h (12 mg total dose) facilitated thrombolysis | No | Yes (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO] and on inotropic support with epinephrine and milrinone) | UFH | N/A | Epinephrine was discontinued within 24 h of thrombolysis and a 40mmHg arterial pulse pressure was noted with echocardiogram confirming improvement in RV size and function | N/A |

CDT: catheter-directed thrombolysis, UFH: unfractionated heparin, LMWH: low-molecular-weight heparin, tPA: tissue plasminogen activator, rt-PA: recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

Quality assessment of the included studies

Using the JBI quality assessment tool for case reports and case series, the overall quality of the included studies was fair to good. Of our 12 case reports, 10 were of good quality, and two were of fair quality. All included case reports described the patient’s demographic characteristics, reported the diagnostic methods and results, and provided takeaway messages. The details of the quality assessment for case reports are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Of the four included case series, two studies were of good quality and the other two were of fair quality. All the included case series did not clearly report complete inclusion of participants, and did not clearly provide the demographic information of the study site. The details were described in Supplementary Table 2.

Risk factors

The most frequent risk factor of PE was obesity 40% (16/40) followed by LL DVT 35% (14/40), oral contraceptive (OCP) use 27.5% (11/40), Thrombophilia 22.5% (9/40), history of congenital heart disease 10% (4/40) and smoking 7.5% (3/40).

Outcomes

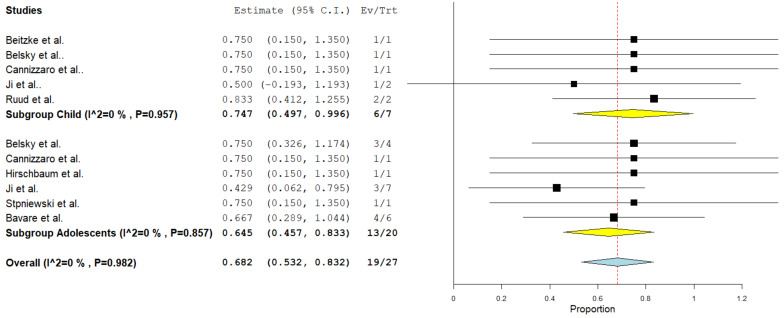

Complete resolution of thrombus

A total of eight studies comprising 27 cases were included in this analysis. Complete thrombus resolution revealed a rate of 68% (95%CI = 46–80%) in a fixed-effect model. No substantial heterogeneity was found among the studies (I²= 0%, p = 0.982). Subgroup analysis for children showed a complete resolution rate of 75% (95%CI = 50–99%) and for adolescents revealed a complete resolution rate of 65% (95%CI = 46–83%). (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pooled estimate of the rate of complete resolution of thrombus following CDT

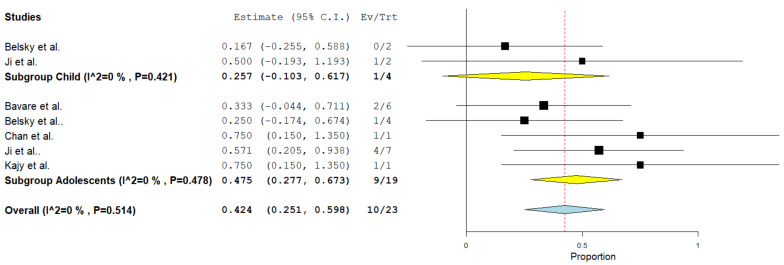

Partial resolution of thrombus

Twenty-three cases from 5 studies were included. The pooled incidence of partial thrombus resolution was 42% (95%CI = 25–60%) using the fixed-effect model. The studies were homogenous (I²= 0%, p = 0.514). (Fig. 3). Subgroup analysis for children showed a complete resolution rate of 25% (95%CI = 10–61%) and for adolescents revealed a complete resolution rate of 47% (95%CI = 28–67%).

Fig. 3.

Pooled estimate of the rate of partial resolution of thrombus following CDT

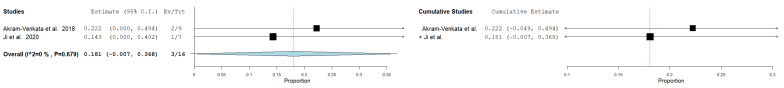

All-cause mortality

Only two studies -enrolling adolescent patients exclusively- reported mortality rate with a total sample of 16 cases considered for analysis. The pooled all-cause mortality rate was 18% (95%CI = 0.7–36%) using the fixed-effect model. No heterogenity was observed (I²= 0%, p = 0.679) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Pooled estimate of the rate of mortality following CDT

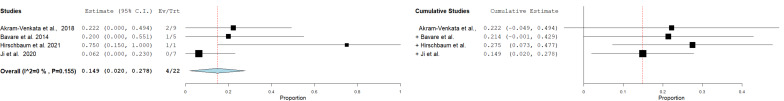

Recurrent pulmonary embolism

Analyzing three studies with 22 cases, the pooled incidence of recurrent pulmonary embolism was 15% (95%CI = 2–28%) in a fixed-effect model. There was no heterogenity among the included studies (I²= 0%, p = 0.155) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Pooled estimate of the rate of recurrent pulmonary embolism following CDT

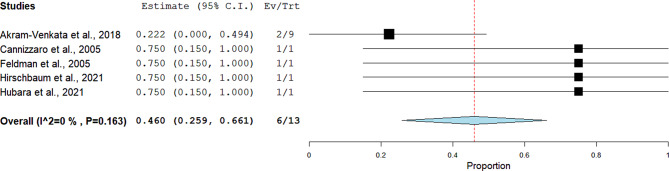

Non-major bleeding

Five studies comprising 13 patients -enrolling adolescent patients exclusively- reported this outcome. The pooled proportions revealed a rate of 46% (95%CI = 26–66%) using the fixed-effect model. No heterogenity was noticed (I²= 0%, p = 0.163) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Pooled estimate of the rate of non-major bleeding following CDT

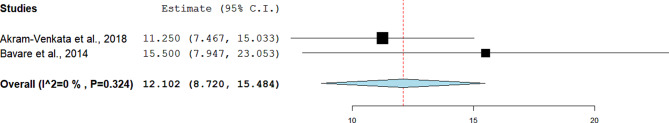

Duration of hospital stay

Two studies reported the mean duration of hospital stay. The pooled effect estimate was 12.1 (95%CI = 8.72 to 15.48). The two studies were homogenous (I²= 0%, p = 0.324) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Pooled estimate of the duration of hospital stay

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the safety and efficacy of CDT in pediatric PE. Although there is scarce data concerning this modality of PE therapy, several outcomes were concluded based on quantitative analyses. CDT was shown to result in complete resolution of thrombus in 63% of cases and all-cause mortality was estimated to be 15%. While CDT was associated with a 27% recurrence rate and a 46% risk of non-major bleeding, sufficient data was not available to estimate the risk of major bleeding.

In general, PE management usually involves the administration of anticoagulants with or without thrombolytic therapy depending on the hemodynamic stability of patients [11]. For stable patients, anticoagulation alone is the mainstay of treatment. Systemic thrombolysis is indicated in PE patients presenting with right ventricular strain shown on echocardiography due to the high risk of right ventricular failure and cardiogenic shock in these patients [12]. However, such intervention might be contraindicated or unfavorable in some patients as it carries significant bleeding risks [13, 14]. Of note, up to 20% of patients who have no absolute contraindications for systemic thrombolysis still experience major bleeding events [15]. Another potential modality for the management of massive PE is surgical embolectomy, though considered a risky procedure given the need for sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass [16]. CDT has been advocated recently as a novel treatment option for patients with massive PE that is both effective and carries a relatively low risk of adverse events [17]. As per recommendations of the American heart association (AHA), CDT is recommended for patients with massive PE in whom systemic thrombolysis fails or is contraindicated. In addition, CDT can be considered in submassive PE cases that are deemed to have poor prognosis [18]. In terms of efficacy, a remarkable reduction in the right ventricular afterload and better hemodynamics are expected shortly following CDT interventions. On the other hand, CDT imposes small risks of bleeding events due to the small doses of thrombolytics that are used in such procedure. Mostly, non-major bleeding as a complication was encountered in 6 patients of the population included in our analysis which was in most cases minimal gastrointestinal bleeding and mild bleeding at the sheath site except for a large inguinal hematoma at the access site in a case report by Cannizzaro et al. [19].

While pharmacologic thrombolysis is the most commonly intervention performed in catheter-directed therapy for PE, many other mechanical modalities are currently employed and are potentially helpful, safe and effective, such as: catheter-mediated fragmentation, aspiration, hydrolyzer thrombectomy, rotarex, and rheolytic techniques [20–22].

The decision regarding which modality to be employed in the treatment of PE in children is not always driven by clear indications as there is paucity of data on the efficacy and safety of different approaches of PE management in pediatrics [23]. Of note, systemic thrombolysis have for too long been used in the treatment of massive/submassive PE. However, systemic thrombolysis have many absolute and relative contraindications including bleeding tendency. This in part determines the preference for CDT in treating pediatric PE. Additionally, the availability of advanced catheterization facilities and the expertise of interventionalists in a center also greatly influence the choice of therapy for such group of patients [5, 24]. While it is not clear which is the safer approach in pediatrics, CDT -in adults- appears to be associated with higher risks of bleeding than anticoagulation alone, on the other hand, systemic thrombolysis is associated with higher risks of bleeding and mortality when compared with both approaches [25].

Compared to systemic thrombolysis, more technically challenging and invasive CDT interventions show many benefits that account for improved procedural safety and less complications. For instance, they provide a more accurate and the gold standard diagnosis through angiography. While CDT therapy aims to deliver very low doses of the thrombolytic agent to reduce the bleeding risks, it results in the delivery of high concentrations of thrombolytics to thrombi. In adults, the consensus is to utilize CDT instead of systemic thrombolysis in intermediate risk/submassive PE cases [24]. On the other hand, evidence still lacks when considering CDT in the pediatric population. Differences between the adult age group and the pediatric age group have to be appreciated in the decision of which strategy to be used for many reasons. Generally, children possess anatomical characteristics that differs from adults as they have significantly smaller vessels than those of the adult population which would require different catheter sizes and more advanced skills and techniques to be used in CDT. Furthermore, pediatric patients develop PE due to risk factors and etiologies that are different from adults [26]. To our knowledge, there are no preferred catheter types or characteristics when it comes to choosing catheters used in CDT in pediatric PE. However, the first catheter type to get the approval of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in adults is the EkoSonic endovascular system and there has been a number of randomized clinical trials supporting its use [27, 28]. The most popular trial to have assessed the utility of EkoSonic system in adults was the SEATTLE II trial which was a prospective multi-center trial enrolling 150 adults with PE treated with the EkoSonic system resulting in resolution of right ventricular strain, pulmonary artery.

obstruction, and pulmonary hypertension [27]. Of note, there have been no cases of intracranial hemorrhage in the patients treated with CDT using the EkoSonic system in that trial. Additionally, many reports have investigated the utility of other catheter types like Cragg-McNamara valved infusion catheters which have emerged as options with similar efficacy and safety [29, 30]. Overall, the results of those trials on adults showed similar efficacy and safety endpoints when compared to the results of this meta-analysis on pediatric patients. Additionally, many reports have investigated the utility of other catheter types like Cragg-McNamara valved infusion catheters which have emerged as options with similar efficacy and safety [29, 30]. Overall, the results of those trials on adults showed similar efficacy and safety endpoints when compared to the results of this meta-analysis on pediatric patients.

There is a debate over the use of EkoSonic endovascular system in young children due to possible fluid overload. Another device that is utilized in many case reports is the AngioJet (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) which is used on an off-label fashion despite the adverse cardiovascular and hemodynamic effects reported concerning its use in pediatric population [31, 32].

Limitations

While this is the first meta-analysis to assess the utility of catheter-directed therapies in the treatment of acute pulmonary embolism in the pediatric population, it has some limitations. As there is paucity in the existing literature concerning the topic of this study (i.e., no randomized trials or strong observational studies on the topic), the data we incorporated into our analysis is collected mainly from case reports and series which are considered to have low strength of evidence. Additionally, the analysis is limited by the low number of included patients and the lack of data needed to conduct comparative analyses between systemic thrombolysis and catheter-directed therapies as well as to evaluate the performance of different catheter types/models.

Conclusion

CDT represents an emerging as a novel modality in the treatment of acute PE in children particularly in patients with massive/submassive PE. Despite the lack of evidence regarding its use in pediatric PE, it should be considered in selected patient populations. Further research -particularly cohort studies comparing CDT against the standard anticoagulation approach or systemic thrombolysis approach- is required to confirm the utility of CDT in PE pediatric patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Basel F. Alqeeq (BA) and Dina Essam (DE) are considered the first authors. They participated in the screening and selection of the studies, contributed to the conception, formulation, and drafting of the article, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. DE and BA also conducted the research strategy and participated in the screening of the studies. Mohamed Rifai (MR) participated in the screening of the studies. DE and MR conducted the data extraction and quality assessment of the included studies. DE, BA, and Mohammed Alsabri (MA) conducted the analysis, wrote the results chapter, and helped in writing the original manuscript and critical revision. MA is the corresponding author, who proposed the project, wrote the protocol, participated in screening and selecting studies, contributed to conception, formulation, and drafting of the article, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Luis L. Gamboa (LG), Ibrahim Qattea (IQ), Mohammed Hamzah (MH), and Khaled M. Al-Farawi (KA) helped in revising the final manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Data availability

All data used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Protocol registration

The protocol of this study was registered in PROSPERO (Reg. no. CRD42024534229).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Basel F. Alqeeq and Dina Essam Abo-elnour contributed equally to this work and should be considered first authors.

References

- 1.Goldenberg NA, Bernard TJ. Venous thromboembolism in children. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24(1):151 – 66. 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.11.005. PMID: 20113900. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Van Ommen CH, Peters M. Acute pulmonary embolism in childhood. Thromb Res. 2006;118(1):13–25. 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.05.013. Epub 2005 Jun 29. PMID: 15992866. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Monagle P, Cuello CA, Augustine C, Bonduel M, Brandão LR, Capman T, Chan AKC, Hanson S, Male C, Meerpohl J, Newall F, O’Brien SH, Raffini L, van Ommen H, Wiernikowski J, Williams S, Bhatt M, Riva JJ, Roldan Y, Schwab N, Mustafa RA, Vesely SK. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of pediatric venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3292–316. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024786. PMID: 30482766; PMCID: PMC6258911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Ommen CH, Luijnenburg SE. Anticoagulation of pediatric patients with venous thromboembolism in 2023. Thromb Res. 2024;235:186–93. 10.1016/j.thromres.2023.12.019. Epub 2024 Feb 10. PMID: 38378308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaidi AU, Hutchins KK, Rajpurkar M. Pulmonary embolism in children. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:170. 10.3389/fped.2017.00170. PMID: 28848725; PMCID: PMC5554122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monagle P, Chan AK, Goldenberg NA, Ichord RN, Journeycake JM, Nowak-Göttl U, Vesely SK. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(7):590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanslik A, Thom K, Winston J, Kunisaki SM, Trent J, Berman D, Connolly B, Goldenberg NA. Thromb Res. 2019;173:128–35. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biss TT, Brandão LR. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117(10):1863–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaatz S, Ahmad D, Spyropoulos AC, Schulman S, Anticoagulation, tSoCo. Definition of clinically relevant non-major bleeding in studies of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolic disease in non-surgical patients: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(11):2119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan SM, Laage Gaupp FM, Lee JM, Pollak JS, Khosla A. Catheter-directed embolectomy for massive pulmonary embolism in a pediatric patient. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022;10:2050313X221112361. 10.1177/2050313X221112361. PMID: 35847425; PMCID: PMC9280839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel. Executive summary: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):7Se47S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alpert JS, Smith R, Carlson J, et al. Mortality in patients treated for pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1976;236:1477e80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Olschewski M, et al. Association between thrombolytic treatment and the prognosis of hemodynamically stable patients with major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. Circulation. 1997;96:882e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldhaber SZ, Haire WD, Feldstein ML, et al. Alteplase versus heparin in acute pulmonary embolism: randomized trial assessing right-ventricular function and pulmonary perfusion. Lancet. 1993;341:507e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiumara K, Kucher N, Fanikos J, et al. Predictors of major hemorrhage following fibrinolysis for acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:127e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robison RJ, Fehrenbacher J, Brown JW, et al. Emergent pulmonary embolectomy: the treatment for massive pulmonary embolus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;42:52e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo WT, Gould MK, Louie JD, et al. Catheter directed therapy for the treatment of massive pulmonary embolism: systematic review and meta-analysis of modern techniques. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1431e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cannizzaro V, Berger F, Kretschmar O, Saurenmann R, Knirsch W, Albisetti M. Thrombolysis of venous and arterial thrombosis by catheter-directed low-dose infusion of tissue plasminogen activator in children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27(12):688 – 91. 10.1097/01.mph.0000193489.80612.d4. PMID: 16344680. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:1788e830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta AA, Leaker M, Andrew M, et al. Safety and outcomes of thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator for treatment of intravascular thrombosis in children. J Pediatr. 2001;139:682e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skaf E, Beemath A, Siddiqui T, et al. Catheter-tip embolectomy in the management of acute massive pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:415e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu S, Shi HB, Gu JP, et al. Massive pulmonary embolism: treatment with the rotarex thrombectomy system. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34:106e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gayou EL, Makary MS, Hughes DR, et al. Nationwide trends in use of catheter-directed therapy for treatment of pulmonary embolism in Medicare beneficiaries from 2004 to 2016. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30:801–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang RS, Maqsood MH, Sharp ASP, Postelnicu R, Sethi SS, Greco A, Alviar C, Bangalore S. Efficacy and safety of Anticoagulation, Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis, or systemic thrombolysis in Acute Pulmonary Embolism. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16(21):2644–51. Epub 2023 Oct 18. PMID: 37855802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thacker PG, Lee EY. Pulmonary embolism in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(6):1278–88. PMID: 26001239. 10.2214/AJR.14.13869 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Piazza G, Hohlfelder B, Jaff MR, et al. A prospective, single-arm, multicenter trial of ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose fibrinolysis for acute massive and submassive pulmonary embolism: the SEATTLE II study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1382–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kucher N, Boekstegers P, Muller OJ, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2014;129:479–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroupa J, Buk M, Weichet J, Malikova H, Bartova L, Linkova H, Ionita O, Kozel M, Motovska Z, Kocka V. A pilot randomised trial of catheter-directed thrombolysis or standard anticoagulation for patients with intermediate-high risk acute pulmonary embolism. EuroIntervention. 2022;18(8):e639-e646. 10.4244/EIJ-D-21-01080. PMID: 35620984. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Sadeghipour P, Jenab Y, Moosavi J, Hosseini K, Mohebbi B, Hosseinsabet A, Chatterjee S, Pouraliakbar H, Shirani S, Shishehbor MH, Alizadehasl A, Farrashi M, Rezvani MA, Rafiee F, Jalali A, Rashedi S, Shafe O, Giri J, Monreal M, Jimenez D, Lang I, Maleki M, Goldhaber SZ, Krumholz HM, Piazza G, Bikdeli B. Catheter-Directed thrombolysis vs anticoagulation in patients with Acute Intermediate-High-risk pulmonary embolism: the CANARY Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(12):1189–97. 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.3591. PMID: 36260302; PMCID: PMC9582964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sur JP, Garg RK, Jolly N. Rheolytic percutaneous thrombectomy for acute pulmonary embolism in a pediatric patient. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70(3):450–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudzinski DM, Giri J, Rosenfield K. Interventional treatment of pulmonary embolism. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:e004345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akam-Venkata J, Forbes TJ, Schreiber T, Kaki A, Elder M, Turner DR, Kobayashi D. Catheter-directed therapy for acute pulmonary embolism in children. Cardiol Young. 2019;29(3):263–9. Epub 2018 Dec 21. PMID: 30572968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bavare AC, Naik SX, Lin PH, Poi MJ, Yee DL, Bronicki RA, Philip JX, Desai MS. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for severe pulmonary embolism in pediatric patients. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(7):1794.e1-7. 10.1016/j.avsg.2014.03.016. Epub 2014 Mar 31. PMID: 24698774. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Beitzke A, Zobel G, Zenz W, Gamillscheg A, Stein JI. Catheter-directed thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute pulmonary embolism after fontan operation. Pediatr Cardiol. 1996 Nov-Dec;17(6):410-2. 10.1007/s002469900091. PMID: 8781096. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Belsky J, Warren P, Stanek J, Kumar R. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for submassive pulmonary embolism in children: a case series. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(4):e28144. 10.1002/pbc.28144. Epub 2019 Dec 25. PMID: 31876109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Claveria JK, Meyer MT, Wakeham MK, Sato TT. Pulmonary embolism in two patients after severe hepatic trauma. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2013;2(3):127–30. 10.3233/PIC-13061. PMID: 31214434; PMCID: PMC6530726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feldman HM, Dale PS, Campbell TF, Colborn DK, Kurs-Lasky M, Rockette HE, Paradise JL. Concurrent and predictive validity of parent reports of child language at ages 2 and 3 years. Child Dev. 2005 Jul-Aug;76(4):856–68. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00882.x. PMID: 16026501; PMCID: PMC1350485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Hirschbaum JH, Bradley CP, Kingsford P, Mehra A, Kwan W. Recurrent massive pulmonary embolism following catheter directed thrombolysis in a 21-year-old with COVID-19: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2021;5(4):ytab140. 10.1093/ehjcr/ytab140. PMID: 34268475; PMCID: PMC8276601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hubara E, Borik S, Kenet G, Mishaly D, Vardi A. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for in situ pulmonary artery thrombosis in children. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2021 Apr-Jun;14(2):211–4. 10.4103/apc.APC_162_20. Epub 2021 May 3. PMID: 34103863; PMCID: PMC8174625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Ji D, Gill AE, Durrence WW, Shah JH, Paden ML, Patel KN, Williamson JL, Hawkins CM. Catheter-Directed Pharmacologic Thrombolysis for Acute Submassive and Massive Pulmonary Emboli in Children and Adolescents-An Exploratory Report. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21(1):e15-e22. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002172. PMID: 31688811. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Kajy M, Blank N, Alraies MC, Akam-Venkata J, Aggarwal S, Kaki A, Mohamad T, Elder M, Schreiber T. Treatment of a child with Submassive Pulmonary Embolism Associated with Hereditary Spherocytosis using Ultrasound-assisted Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis. Ochsner J 2019 Fall;19(3):264–70. 10.31486/toj.18.0147. PMID: 31528140; PMCID: PMC6735608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Ruud E, Holmstrøm H, Aagenaes I, Hafsahl G, Handeland M, Kyte A, Brosstad F. Successful thrombolysis by prolonged low-dose alteplase in catheter-directed infusion. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92(8):973-6. 10.1080/08035250310004270. PMID: 12948076. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Stępniewski J, Magoń W, Waligóra M, Jonas K, Wilczek Ł, Zauska-Pitak B, Góreczny S, Kopeć G. Catheter-directed therapy for treatment of acute pulmonary embolism in a teenage patient: the role of close cooperation between the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team and pediatric physicians. Kardiol Pol. 2023;81(12):1300–1. 10.33963/v.kp.97954. Epub 2023 Nov 24. PMID: 37997840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Visveswaran GK, Morparia K, Narang S, Sturt C, Divita M, Voigt B, Hawatmeh A, McQueen D, Cohen M. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 infection and thrombosis: Phlegmasia Cerulea Dolens presenting with venous gangrene in a child. J Pediatr. 2020;226:281–e2841. Epub 2020 Jul 13. PMID: 32673617; PMCID: PMC7357514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.