Abstract

Recently, there has been growing interest in the role of circular RNAs (circRNAs) in the progression of human cancers. Cellular senescence, a known anti-tumour mechanism, has been observed in several types of cancer. However, the regulatory interplay of circRNAs with cellular senescence in pancreatic cancer (PC) is still unknown. Therefore, we identified circHIF-1α, hsa_circ_0007976, which was downregulated in senescent cells using circRNA microarray analysis. Meanwhile, significantly upregulated expression of circHIF-1α in pancreatic cancer tissue detected by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and in situ hybridization (ISH). High circHIF-1α expression levels were found to independently predict poor survival outcomes. Subsequent treatments with DOX and H2O2 resulted in significantly lower levels of circHIF-1α. CircHIF-1α knockdown induces cellular senescence and suppresses PC proliferation in vitro experiments. The ability of circHIF-1α knockdown to suppress the progression of PC cells was further confirmed in vivo experiments. Our results showed that circHIF-1α is mainly presented in the nucleus of PC cells, also in the cytoplasm. Mechanistically, circHIF-1α inhibited senescence and accelerated the progression of PC cells through miR-375 sponging, thereby promoting HIF-1α expression levels. Nuclear circHIF-1α interacted with human antigen R protein (HUR) to increase HIF-1α expression. Thus, our results demonstrated that circHIF-1α ameliorates senescence and exacerbates growth in PC cells by increasing HIF-1α through targeting miR-375 and HUR, suggesting that targeting circHIF-1α offers a potential therapeutic candidate for PC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12935-025-03645-w.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, circHIF-1α, Senescence, HIF-1α, HUR

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest malignancies in the world [1]. The effectiveness of clinical treatments for pancreatic cancer remains unsatisfactory due to its complex pathogenesis [2]. Patients with early-stage pancreatic cancer found in the clinic can usually be treated with surgical resection [3]. Several therapeutic benefits have been achieved. However, in most cases, pancreatic cancer is diagnosed at an advanced stage, rendering tumor resection an ineffective treatment option. Only radiotherapy, chemotherapy or targeted therapy can be utilized. Chemotherapy is the first choice of treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer [4]. However, there are many problems and limitations, such as the clinical problems of choosing a chemotherapy regimen and the high incidence of cellular resistance [5]. Therefore, the therapeutic effects in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer are limited. The status of poor postoperative outcomes and high recurrence rates of pancreatic cancer have not been fundamentally improved [6]. Thus, there is a great need for in-depth research in the development of pancreatic cancer.

Circular RNA (circRNA) is a newly discovered non-coding RNA produced by reverse splicing that lacks an endogenous 5 cap and 3 tail covalent closed structure. As experimental techniques and analyses continue to be updated and developed, several studies have shown that circRNAs are widely expressed, highly conserved and highly stable, which has led them to be considered as potential biomarkers for a wide range of diseases. CircRNAs can also act as microRNA molecular sponges, participate in selective splicing, and interact with RNA-binding proteins to exert their biological functions. Meanwhile, CircRNAs contribute significantly to cancer development through diverse mechanisms. One such example is the involvement of the circRTN4-miR-497-5p-HOTTIP pathway in promoting tumor growth and liver metastasis in PDAC [7]. CircANAPC7 acts via the CREB-miR-373-PHLPP2 axis as a novel tumour suppressor in pancreatic cancer [8]. Other findings are an indication that pancreatic cancer progression may be driven by circSEC24A via the miR-606/TGFBR2 axis [9]. In addition, hsa_circ_0068631 enhances the stability of the c-Myc mRNA via enlisting EIF4A3, which affects breast cancer tumourigenesis [10]. circTHBS1 was shown to be a driver of gastric cancer progression by increasing INHBA mRNA stability in an RBP-dependent manner [11]. However, it is not clear how circular RNA hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (circHIF-1α) regulates pancreatic cancer progression.

Cellular senescence is a phenomenon of permanent cell proliferation cycle arrest that can occur at all stages of development and growth and is a vital mechanism for the maintenance of organizational homeostasis and the prevention of the proliferation of damaged cells [12]. It was originally thought to be an important tumour suppressor mechanism because of its ability to inhibit the proliferation of tumour cells by blocking the cell cycle [13]. Previous data have demonstrated that senescence is a significant barriers to PC progression [14]. CircRNAs exert significant regulatory functions in cellular senescence owing to their structural stability, abundance, and tissue-specific expression [15]. The circular intronic RNA ciPVT1 is reported to delay senescence, induce proliferation, and increase the angiogenic activity of endothelial cells [16]. In the context of senescence induction, circ-Foxo3 interacts with several senescence-associated proteins, including ID-1, E2F1, FAK, and HIF1α [17]. Similarly, CircLARP4 promotes cellular senescence and suppresses proliferation in HCC [18]. However, the relationship between the regulatory of circRNAs in cellular senescence and the progression of PC remains unclear.

In this study, through sequencing analysis, we identified and characterized a senescence-associated circRNA circHIF-1α, derived from the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) gene exon region, which was found to be upregulated in PC tissues and downregulated in senescent PC cells. Further functional and mechanistic investigations revealed that CircHIF-1α mediates senescence and enhances the proliferation and motility of PC cells through the regulation of the miR-375/HIF-1α and the HUR/HIF-1α axis.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Fourty-three pancreatic cancer patients, who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy at the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University’s Hepatobiliary Surgery Department (Guiyang, China), were chosen for this study. None of these patients underwent preoperative chemoradiotherapy or immunotherapy. Postoperatively, two pathologists confirmed the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in all patients, and comprehensive follow-up data were available. Both tumor tissue and adjacent tissues were subjected to reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and in situ hybridization (ISH) analyses. All participants provided informed consent, and the study adhered to the ethical guidelines approved by the Ethics Committee of Guizhou Medical University, aligning with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell culture and senescence induction

The American Type Culture Collection provided us with a range of pancreatic cancer cell lines, including PANC-1, AsPC-1, Capan-2, SW1990, BXPC-3, MIA PaCa-2, as well as the human normal pancreatic ductal epithelial cell line, HPDE. The cell lines Capan-2, CFPAC-1, PANC-1, MIA PaCa-2, and SW1990 were grown in DMEM medium enriched with 10 g/dl of fetal bovine serum (FBS) from Gibco. Meanwhile, HPDE, AsPc-1, and BXPC-3 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco) fortified with 10% fetal bovine serum. All cell lines were incubated at 37 ℃ in a cell culture chamber with a CO2 concentration of 5 ml/dl. Cell digestion and passaging occurred when the fusion level reached 80–90%. Doxorubicin(DOX)(50nmol/L), procured from Macklin in Shanghai, China, was used to treat MIA PaCa-2 cells for three days to induce senescence, while DMSO-treated MIA PaCa-2 cells served as the control group.

Circular RNA sequencing analysis

RNA was extracted from both MIA PaCa-2 cells exposed to DOX and those treated with DMSO, using the TRIzol ®reagent (Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This RNA was further processed with the Epicenter Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit (Epicenter, USA) to eliminate rRNA. Following this, cDNA was prepared and synthesized using random primers. The cDNA underwent PCR amplification, and the resulting products were purified. Quality control checks were conducted on the libraries before sequencing them on the HiSeq 2500 platform (Illumina, USA). To identify the notably downregulated circRNAs in the DOX-induced group, volcano plots were employed, along with a set fold change (FC) threshold of 1.5.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from PC cells and tissues using the TRIzol reagent (Takara). cDNA was synthesized through reverse transcription with the PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd) for assessing mRNA and circRNA expression levels. Specific miRNAs were reverse transcribed using the miRNA First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Sangon). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on the CFX96 Touch instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with TB Green® Fast qPCR Mix (Takara) as the detection reagent. Internal controls for normalization included U6 and GAPDH. Gene expression quantification was determined using the 2-delta Ct calculation method. The primer sequences used in this study are provided below:

circHIF-1α Forward primer (5′ to 3′): TGAGAGAAATGCTTACACACAGA,

circHIF-1α Reverse primer (5′ to 3′): ACAAAACCATCCAAGGCTTTCA;

miR-375 Forward primer (5′ to 3′): GCGTTTGTTCGTTCGGCTC,

miR-375 Reverse primer (5′ to 3′): AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATT;

HIF-1α Forward primer (5′ to 3′): TCCTTCGGACACATAAGCTCC,

HIF-1α Reverse primer (5′ to 3′): GACAGAAAGATCATGTCACCGT;

U6 Forward primer (5′ to 3′): CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA,

U6 Reverse primer (5′ to 3′): AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT;

GAPDH Forward primer (5′ to 3′): CTCCAAAATCAAGTGGGGCG,

GAPDH Reverse primer (5′ to 3′): TGGTTCACACCCATGACGAA.

In situ hybridization

The in situ hybridization analysis was conducted following previously described methods [19]. Paraffin-embedded PC sections were treated with varying concentrations of xylene and ethanol before undergoing the hybridization step. After exposure to a pre-hybridization solution for 60 min at room temperature in a humid chamber, the sections were incubated overnight with a biotin-labeled circHIF-1α probe obtained from Guangzhou Ribo Biological Co., Ltd. at a constant temperature of 40 °C. Nuclear staining was performed using hematoxylin, and visualization of circHIF-1α signals was facilitated with a digoxin substrate.

RNase R digestion

RNA samples were treated with RNase-free water or RNaseR (obtained from Lucigen) in a reaction buffer at 37 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, the samples were purified using the RNeasy MinElute purification kit from Qiagen (Germantown, MD, USA). The processed RNA samples were then analyzed using RT-qPCR following established protocols. In parallel, PC cells were exposed to either 2 µg/mL of actinomycinD (supplied by Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) from Sigma-Aldrich for 12 h. The relative expression levels of circHIF-1α were quantitatively assessed through RT-qPCR, and its half-life was determined after cell harvest.

Nuclear-cytoplasmic RNA isolation cytoplasmic and nuclear

The complete set of subcellular RNA components was isolated from PC cells using the PARIS kit from Life Technologies, following the manufacturer’s guidelines. To normalize the data, GADPH was used as the reference gene for cytoplasmic RNA and U6 for nuclear RNA. The ratio of cytoplasmic to nuclear RNA was then determined through RT-qPCR analysis.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

GenePharma (Suzhou, China) synthesized and provided Cy5-tagged circHIF-1α probes for observing the subcellular localization of circHIF-1α in PC cells. Cells from both experimental and control groups were seeded in a confocal dish at a concentration of 2 × 10^5 and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (supplied by Solarbio Life Sciences). Cell digestion was facilitated by Protease K (from Invitrogen). After permeabilization with a PBS mixture containing 0.5% Triton X-100, the cells underwent prehybridization buffer treatment for 30 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, the probe, diluted in a hybridization solution, was applied to the cell slides, denatured at 73 °C for 3 min, and allowed to hybridize overnight at 42 °C. Prior to imaging with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), the cells were exposed to a DAPI working solution for 15 min.

Cell transfection and lentiviral infection

The reagents used in this study included circHIF-1α-overexpressing lentiviruses, short hairpin RNAs targeting circHIF-1α, MiR-375 mimics, siRNAs against HIF-1α and HUR, as well as their corresponding negative controls, all sourced from Ruibo Biotechnology in Guangzhou, China. Transfection procedures were carried out according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Cells were collected for analysis 48 h post-transfection.

Cell proliferation assays

For the CCK-8 assay, PC cells were transfected at a density of 2000 cells per well and then treated with CCK-8 reagent sourced from the Bosterbio CCK-8 kit in China. Cell proliferative capacity was assessed by measuring absorbance at 450 nm after incubation periods of 0 h for cell attachment, 24, 48, and 72 h at 37 °C. To prepare for the 5-Ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EDU) assay, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, followed by a 5-minute treatment with Triton (1%) to make the cells transparent after washing with PBS. Subsequently, cells were incubated with the EDU stain for 30 min in a dark environment, then stained with 1 × Hoechst 33,342 and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. The resulting images were captured using a fluorescence microscope from Olympus, Japan.

Colony formation assay

The treated cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured for 14 days at 37 °C. Medium changes were performed every 4 days, and the colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Following a wash with PBS, the cells were stained with a 0.5% solution of crystal violet (Solarbio Life Sciences) for 30 min. Finally, the colonies were imaged and counted.

Transwell assay

The transwell assay involved seeding 200 µL of serum-free PC cells (at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well) in the upper chamber, while the lower chamber was filled with a complete medium containing 10% FBS, following the manufacturer’s instructions for the Transwell Cell Migration Assay Kit. After a 24-hour incubation, the medium from the upper chamber was removed, and the migrated cells were fixed with 4 g/dl paraformaldehyde for 30 min and stained with 0.05 g/dl crystal violet for 30 min. Prior to the transwell invasion experiment, the upper chamber was pretreated with 60 µL of Matrigel from Matrigel BD Biosciences, NY, USA. Representative images were captured using an inverted microscope (Olympus).

Wound healing assay

After planting cells in different groups, a 200 µL pipette tip was used to create a scratch in the cell wound. Migration was documented using an inverted microscope (Olympus) at specified times (0 and 48 h), and the migration rate was standardized to the initial scratched area at 0 h.

Luciferase reporter assay

Cells in logarithmic growth phase were cultured in 6-well plates. The cells were transfected with circHIF-1α wild-type and 3’UTRmut mutant fluorescent plasmids containing the miR-375 binding site, as well as HIF-1α wild-type and 3’UTRmut mutant fluorescent plasmids. After 48 h of incubation, the supernatant was collected for analysis following the addition of passive lysis buffer. The absorbance of each well was measured at 580 nm using a microplate reader after adding Luciferase Assay Reagent II. The relative luciferase activity was then normalized using firefly luciferase.

Immunofluorescence (IF) anaylsis

Prior to fixation, the cells were rinsed with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) and then treated with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. Subsequently, a 15-minute incubation with 0.1% Triton X-100 (sourced from Sigma, USA) on ice was conducted, followed by allowing it to reach room temperature. To prevent non-specific binding, the cells were blocked with 3% BSA for 30 min. Next, they were exposed to the primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. Following this, a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled secondary antibody (obtained from Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was applied for an hour. The cell nuclei were then stained with DAPI for 15 min at room temperature. Visualization and capture of the target protein expression were carried out using a confocal laser scanning microscope (manufactured by Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), with analysis of the images performed using ZEN Imaging Software 2.6 (blue edition).

Western blotting

Total proteins were extracted using RIPA buffer (supplied by Boster BiotECHNOLOGY CO., LTD.) with the addition of 1% PMSF (also sourced from Boster BiotECHNOLOGY CO. LTD.). Protein concentration was determined using the BCA assay. The proteins were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to PVDF membranes (obtained from Millipore, MA, USA). To prevent non-specific binding, the membranes were blocked with 5% milk. Subsequently, the membranes containing the proteins of interest were incubated with the respective primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After three washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated with HRP-linked secondary antibodies. Protein bands were visualized using an ECL kit from Boster, and quantification was performed using Image Lab software. The study utilized antibodies against RB, GAPDH, HUR, HIF-1α, Laminb1, P21, γ-H2AX, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and Vimentin. GAPDH and KRAS antibodies were obtained from ABclonal Technology, Wuhan, China, while the rest were procured from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA.All of the complete, unedited blots are exhibited in the supplemental material.

RNA pull-down assay and RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

To conduct the RNA pull-down assay, a biotinylated RNA probe specific to circHIF-1α or a negative control probe was incubated with streptavidin-covered magnetic beads for 30 min at 26 °C to create beads coated with the probe. Subsequently, lysed cells were mixed with these beads and incubated for 4 h at 4 °C with gentle agitation at 20 rpm/min, allowing the biotin-linked RNA complex to be pulled down. The RNA-protein binding complexes were then washed and incubated in an elution buffer for 30 min at 37 °C. Western blotting analysis was performed to identify the proteins present in the pull-down samples. For RIP, PC cells were collected and lysed using a comprehensive RNA immunoprecipitation lysis buffer containing protease and RNase inhibitors. The resulting cell lysates were then incubated with magnetic beads conjugated with Ago2 antibody or IgG (as a control) overnight at 4 °C. To isolate and detect the RNA, Proteinase K was used to digest proteins, and TRIzol was added to the mixture.

Coomassie brilliant blue staining

Following electrophoresis, the gel was immersed in an ample coomassie brilliant blue solution and left to stain for one hour on a shaker at room temperature. After discarding the staining solution, fresh coomassie brilliant blue destaining solution was added, and the gel was allowed to destain at room temperature for 4 to 24 h. Once destaining was finalized, the gel was submerged in ddH2O until reaching a similar length to the non-stained gel. By referencing the marker proteins and comparing them to the non-stained gel, the gel segment containing the target protein was accurately excised for subsequent mass spectrometry analysis.

RNA stability assay

The cells were transfected with sh-HUR and control PC cells, cultured for 24 h, and then treated with 4 µmol/L actinomycin D for 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h. RNA was extracted from the cells at these time points, and the level of HIF-1α mRNA was measured using RT-qPCR.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) staining

SA-β-Gal staining was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions using the Senescence β-galactosidase Staining Kit from Beyotime in Shanghai, China. The staining kit utilizes X-Gal as the substrate, producing a dark blue product when acted upon by senescence-specific β-galactosidase. Cells expressing β-galactosidase can be easily identified under light microscopy due to their blue color. The staining procedure included fixing the cells with a β-galactosidase staining solution for 10 min at room temperature, followed by three 5-minute washes with 0.01 mol/L PBS. Subsequently, the cells were stained by incubating them overnight at 37 ℃ with a mixture of β-galactosidase staining solutions A, B, and C, along with X-gal in a specific ratio. The stained cells were then observed, photographed, and counted under a light microscope. If immediate observation and photography were not possible, the staining solution could be replaced with PBS and stored at 4 ℃ for several days. Ten fields were randomly selected and photographed for each well, and the percentage of β-galactosidase-positive cells was calculated by dividing the number of positively stained cells by the total cell count. This percentage was then compared statistically across different groups.

Animal experiments

In the animal experiments section, sh-NC and sh-circHIF-1α vectors were constructed and introduced into PC cells using a transfection reagent. All animal procedures were approved by Guizhou Medical University in Guiyang, China. The cell concentration was adjusted to 2.0 × 10^7 cells/mL, and 0.2mL of the vector suspension was injected into the armpits of nude mice, with 5 mice assigned to each group. Tumors became palpable in the right armpit of the nude mice after 2 weeks, indicating successful inoculation. Tumor growth was monitored by measuring the length (L) and width (W) of the tumor using a caliper at 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks post-inoculation. The mice were euthanized on day 30, and the tumors were dissected, accurately weighed, and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis. To assess the impact of circHIF-1α on the metastatic ability of PC cells in vivo, a 100 µL cell suspension was injected into the caudal vein of mice. The mice were euthanized 8 weeks post-injection, and their livers were harvested and stained with haematoxylin-eosin for further analysis.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

For immunohistochemistry (IHC), tissue sections underwent a series of processing steps. Initially, they were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated in ethanol solutions of decreasing concentration (100%, 90%, and 70%). The sections were then placed in cups containing sodium citrate antigen repair solution and heated in a microwave oven at 100 °C for 15 min to retrieve antigens. Subsequently, non-specific binding was blocked using 3% H2O2 and 5% BSA. Primary antibodies were applied to the tissue surfaces and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Prior to coverslipping, DAPI staining solution was added dropwise to the tissue sections, and staining was visualized under orthogonal fluorescence microscopy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 software, with all data presented as mean ± SD. Group differences were assessed using an unpaired Student’s t-test. Viability was evaluated through Kaplan-Meier curves. The correlation between circHIF-1α, miR-375, and HIF-1α expression was analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis, with the r-value indicating the strength of the correlation. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

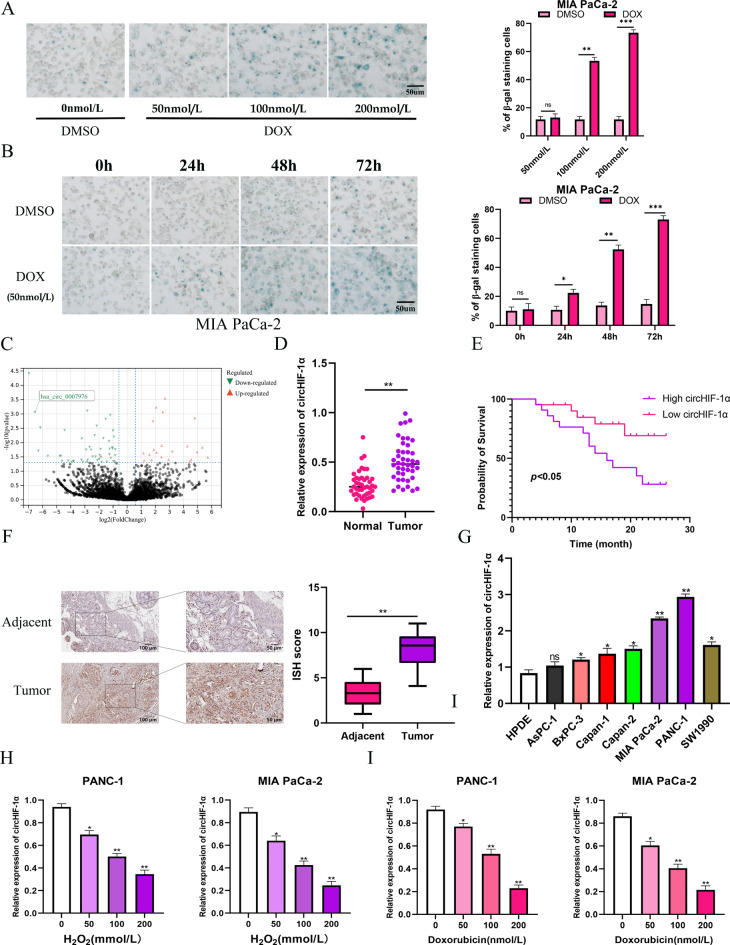

Identification of senescence-associated circRNA in PC cell

With different time and concentration of DOX treatment, senescent MIA PaCa-2 cells displayed a flattened and enlarged morphology with increased SA-β-Gal activity as shown in Fig. 1A-B. The result of above experiment were also confirmed in PANC-1 cells (Supplementary Fig. S1A-B). Analysis of our previous RNA-seq data revealed a significant downregulation of circHIF-1α (circBase ID: hsa_circ_0007976) in these cells, indicating a potential role of circHIF-1α in pancreatic cancer cell senescence (Fig. 1C). Examination of circRNA expression in forty-three paired samples of pancreatic cancer tissues and adjacent pancreatic tissues showed a notable reduction of circHIF-1α in normal pancreatic tissues compared to cancerous tissues (Fig. 1D). Patients were stratified into high and low circHIF-1α expression groups based on median levels, with elevated circHIF-1α expression correlating with decreased overall survival (Fig. 1E). Both ISH and RT-qPCR techniques demonstrated higher circHIF-1α expression in pancreatic cancer tissues and cell lines compared to adjacent normal tissues and normal pancreatic epithelium HPDE, particularly notable in PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines (Fig. 1F-G). RT-qPCR validation confirmed the expression patterns of circHIF-1α consistent with our RNA-seq results. Subsequent treatments with DOX and H2O2 resulted in significantly lower levels of circHIF-1α, further supporting its association with pancreatic cancer senescence (Fig. 1H-I).

Fig. 1.

Identification of senescence-associated circRNAs in PC cells. (A-B) Detection of senescence representative images of SA-β-Gal staining by time and concentration in DMSO-treated and DOX-treated MIA PaCa-2 cells. (C) Volcano plot showing circRNA expression in DOX-treated and DMSO-treated cells (senescent versus proliferation). The red and green dots represent circRNAs with statistically significant differences in expression. (D) RT-qPCR analysis of the levels of circHIF-1α in PC tissues and adjacent tissues. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showing the overall survival of PC patients with high or low levels of circHIF-1α expression. (F) In situ hybridization was performed to determine the expression of circHIF-1α in PC tissues. (G) The expression of circHIF-1α in pancreatic cancer cell lines. (H) RT-qPCR analysis was performed to detected mRNA levels after DOX-treated in MIA PaCa-2 cells. (I) RT-qPCR analysis was performed to detected mRNA levels after H2O2-treated in MIA PaCa-2 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

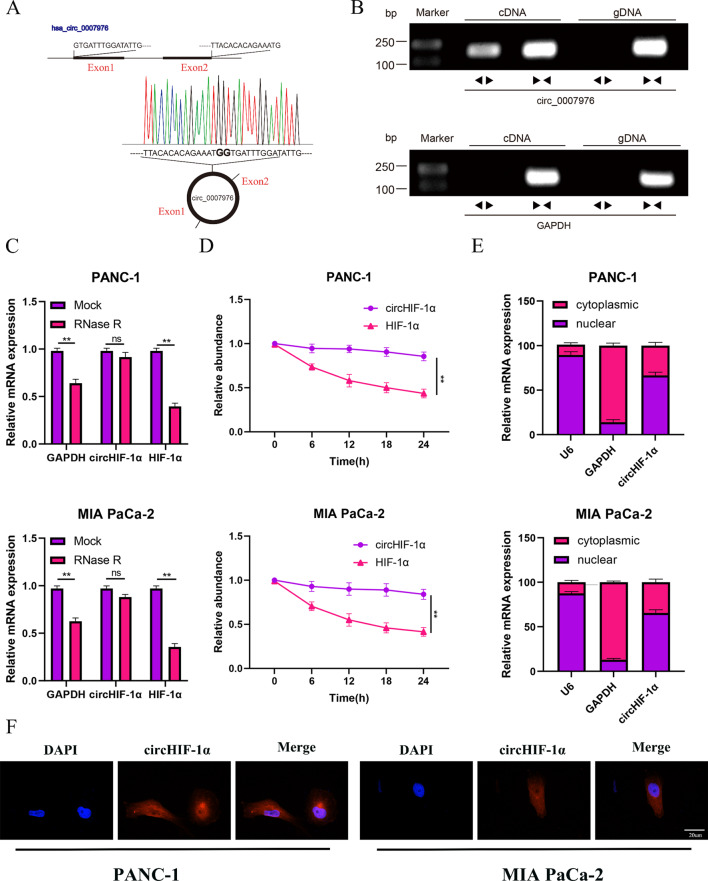

CircHIF-1α was derived from HIF-1α, and located in cytoplasm and nucleus

CircHIF-1α was generated through circularization of exons 1–2 from the host gene HIF-1α, and the head-to-tail splicing was further verified by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 2A). The templates for this process were obtained from both cDNA and gDNA of PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells. Notably, circHIF-1α was only detectable in the cDNA samples and not in the gDNA samples (Fig. 2B). To evaluate the stability of circHIF-1α, RT-qPCR experiment was performed on PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells treated with RNase R. The results demonstrated that circHIF-1α expression remained relatively constant, while the HIF-1α RNA level significantly decreased after RNase R treatment (Fig. 2C). Additionally, our observations indicated that circHIF-1α exhibited notably higher stability compared to its linear counterpart, HIF-1α, in both cell lines after amanitin treatment (Fig. 2D). To determine the subcellular localization of circHIF-1α, we utilized FISH assay and nucleocytoplasmic fractionation. These analyses provided evidence that circHIF-1α is mainly presented in the nucleus of PC cells, also in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2E-F).

Fig. 2.

CircHIF-1α is a conventional circRNA derived from HIF-1α and is located in the cell nucleus and cytoplasm. (A-B) The circHIF-1α was back-spliced by HIF-1α and verified by Sanger sequencing. (C) RT-qPCR was used to detect the expression of circHIF-1α and HIF-1α in PC cells under RNase R treatment. (D) RT-qPCR was used to determine the expression of circHIF-1α and HIF-1α in PC cells under amanitin treatment. (E) Nucleocytoplasmic fractionation revealed the subcellular localization of circHIF-1α in PC cells. (F) FISH revealed the subcellular localization of circHIF-1α in PC cells. **, P < 0.01

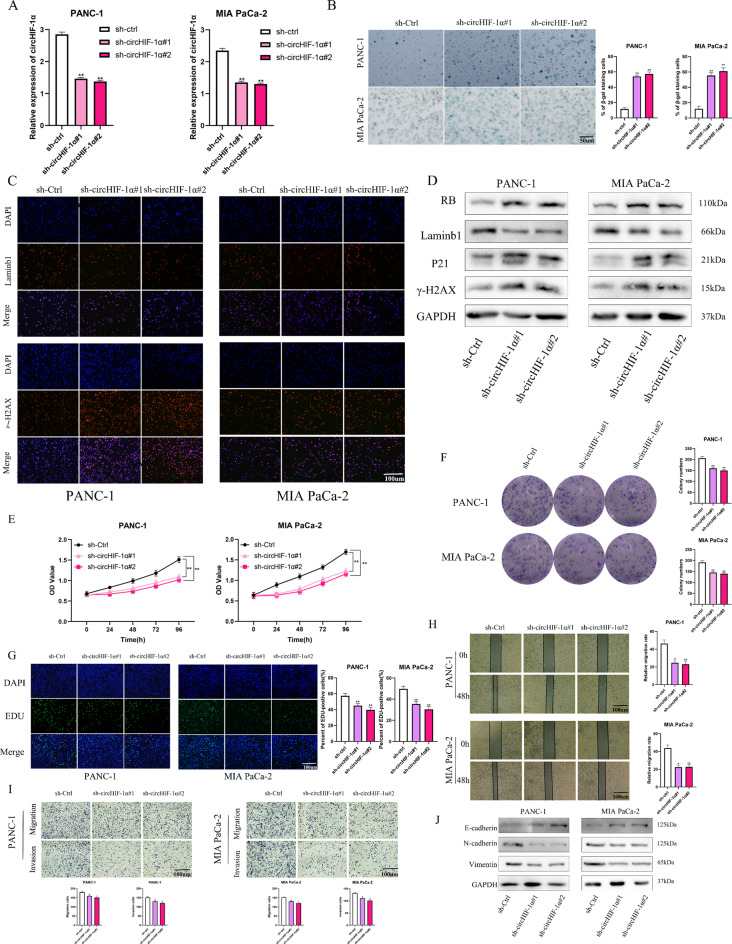

CircHIF-1α delayed senescence and increased the proliferation and motility of PC cells in vitro

Function-related experiments were performed to clarify the function of circHIF-1α in PC cells in order to determine the role of circHIF-1α in PC cells. Compared to the control group, the expression of circHIF-1α was significantly reduced in PC cells with low circHIF-1α expression lentivirus, indicating that the lentiviral construction was successful (Fig. 3A). Treatment with the circHIF-1α silencing sequence significantly induced an enlarged and flattened cell morphology, accompanied by increased SA-β-Gal-positive cells (Fig. 3B). Laminb1 and γ-H2AX are important markers of cellular senescence. Using immunofluorescence, increased levels of γ-H2AX and the loss of laminb1 were observed in PC cells lowly expressing circHIF-1α (Fig. 3C). Western blotting analysis showed that PC cells with downregulated circHIF-1α expressed increased RB, γ-H2AX and P21 protein levels, whereas laminb1 protein levels were decreased (Fig. 3D).The CCK-8 assay result showed that cell viability was rapidly decreased in PANC-1 and MIA-PaCa-2 cell lines(Fig. 3E). In addition, the colony formation assay confirmed a significant inhibition of the cell growth of PC cells that were pre-treated with circHIF-1α shRNA (Fig. 3F). The suppression of circHIF-1α had a reduced effect on PC cells in the EdU assay (Fig. 3G). Similarly, both the wound healing (Fig. 3H) and transwell(Fig. 3I) assays indicated that the invasiveness and migratory ability of PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells were downregulated in the circHIF-1α knockdown groups compared to those in the control group. We then investigated whether biomarkers of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) were altered by the loss of circHIF-1α, as EMT has been shown to play an important role in the process of cancer cell metastasis. Western blotting analysis showed that PC cells with downregulated circHIF-1α expressed lower levels of vimentin and N-cadherin and higher levels of E-cadherin (Fig. 3J). Taken together, these results implicate circHIF-1α in the regulation of the senescent phenotype and proliferative capacity of PC cells.

Fig. 3.

CircHIF-1α delays senescence and promotes the proliferation and mobility of PC cells in vitro. (A) Effectiveness of lentivirus transfection of sh-circHIF-1α verified by RT-qPCR. (B) SA-β-Gal staining assay was performed to determine the senescent PC cells with circHIF-1α knockdown. (C) Immunofluorescence experiment verified the effect of circHIF-1α on the expression of senescence-related biomarker including laminb1 and γ-H2AX. (D) Western blotting was performed to examine the expression of senescence-related protein levels, including RB, laminb1, γ-H2AX and P21. (E) The CCK-8 assay was used to determine the proliferation of PC cells with circHIF-1α loss. (F) Colony formation assay was used to detect the number of colonies in the circHIF-1α-knockdown, and negative control groups. (G) EDU assay was used to determine the EDU positivity of PC cells with circHIF-1α- knockdown. (H-I) Wound healing and transwell assays were used to determine the migration and invasion of PC cells with circHIF-1α- knockdown. (J) Western blotting analysis of EMT markers, including N- cadherin, E-cadherin and vimentin expression, in each group of PC cells. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

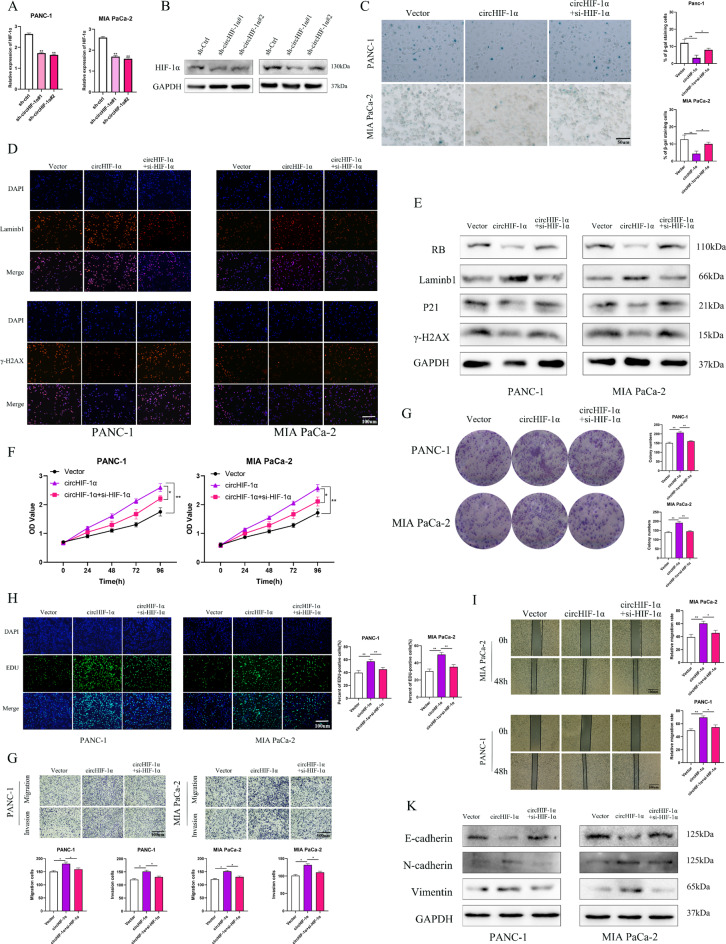

Inhibition of HIF-1α reversed the effects of circHIF-1α on the cell proliferation, motility, and senescence of PC cells in vitro

The involvement of circRNAs in bioregulation has been linked to maternal-dependent processes [20]. To elucidate the interaction between HIF-1α and circHIF-1α, we employed circHIF-1α-overexpressing to upregulated circHIF-1α and siRNAs to downregulate HIF-1α. Our findings revealed that manipulation of circHIF-1α levels altered both the mRNA and protein levels of HIF-1α (Fig. 4A-B). Assessment of cellular senescence in PC cells revealed that circHIF-1α overexpression reduced the SA- β-gal-positive cell population. Conversely, the introduction of anti-HIF-1α effectively counteracted the senescence induced by circHIF-1α (Fig. 4C). The result of immunofluorescence assay showed that the loss of γ-H2AX and increased levels laminb1 in PC cells lowly expressing circHIF-1α were reversed by HIF-1α knockdown (Fig. 4D). Western blotting further showed that circHIF-1α overexpression led to elevated P21 and γ-H2AX levels while decreasing laminb1 and RB expression. These effects were abrogated by HIF-1α suppression (Fig. 4E). By utilizing HIF-1α siRNA, we observed a notable attenuation in PC cell proliferation and colony formation upon HIF-1α knockdown, which were previously accelerated by circHIF-1α (Fig. 4F-H). Functionally, both wound healing and transwell assays demonstrated that HIF-1α inhibition in PC cells curtailed their migratory and invasive capabilities, which were enhanced by circHIF-1α overexpression (Fig. 4I-G). Western blotting analysis in our study indicated that overexpression of circHIF-1α repressed E-cadherin protein levels while concurrently upregulating N-cadherin and vimentin. However, the upregulation of mesenchymal markers mediated by circHIF-1α was negated by HIF-1α deletion, with an inverse trend observed for E-cadherin expression (Fig. 4K).

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of HIF-1α reversed the promotive effects of circHIF-1α on PC cell proliferation, mobility, and senescence. PC cells were treated with empty vector, circHIF-1α- overexpressing lentivirus, and circHIF-1α-overexpressing lentivirus plus HIF-1α siRNA. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of HIF-1α in PC cells after transfection with sh-circHIF-1α. (B) Western blotting analysis of HIF-1α in PC cells after transfection with sh-circHIF-1α. (C) Representative SA-β-Gal staining images are presented to assess senescence in each group of PC cells. (D) Immunofluorescence experiments verified the expression of senescence-related biomarkers, including laminb1 and γ-H2AX, in each group. (E) Western blotting was used to detect biomarkers of senescence in each group, including RB, laminb1, γ-H2AX and P21 protein levels. (F) The CCK-8 assay was used to determine the rate of PC cell proliferation in each group. (G) Colony formation assay was used to detect colony formation in each group. (H) EDU assay was performed to determine the rate of EDU positivity in each group. (I-G) Wound healing and transwell assays were used to determine the rates of migration and invasion in each group. (K) western blotting results of the altered levels of N- cadherin, E-cadherin and vimentin in each group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Cytoplasmic circHIF-1α increased the mRNA level of HIF-1α via sponging miR-375

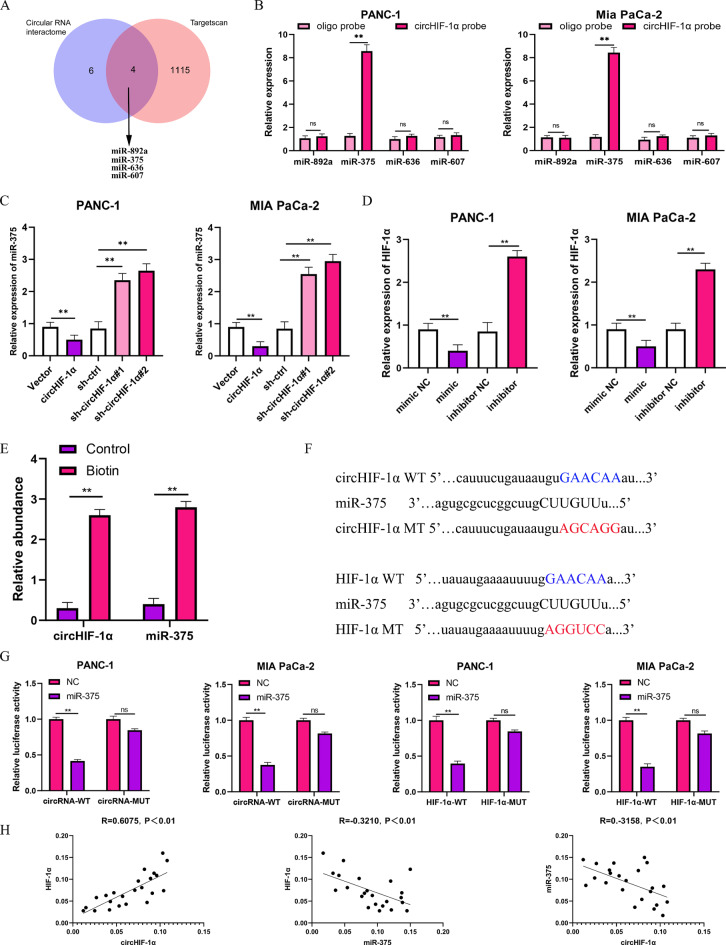

Next, we further investigated the potential mechanism of circHIF-1α in PC. We identified miR-375, miR-892a, miR-636, and miR-607 as possible candidates for the potential targets of circHIF-1α from online bioinformatics prediction databases (Fig. 5A), including circinteractome (https://circinteractome.irpnia.nih.gov/) and TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/). Among these, miR-375 showed the highest enrichment in the circHIF-1α probes in MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells (Fig. 5B). The downregulation of miR-375 by circHIF-1α overexpression was verified by RT-qPCR. In circHIF-1α knockdown cells, miR-375 expression was found to be upregulated. Furthermore, we found that the mRNA levels of HIF-1α in PC cells showed significant changes after overexpression of miR-375, and silencing of miR-375 had an effect on the overexpression of HIF-1α (Fig. 5C). We also found that circHIF-1α and miR-375 were significantly less enriched in the control probes compared to the biotin-labelled miR-375 probes (Fig. 5D). Meanwhile, we found that the potential binding sites of miR-375 were found within the sequence of both circHIF-1α and HIF-1α (Fig. 5E). Dual-luciferase reporter gene assay revealed that miR-375 negatively regulated the luciferase activity of wild-type circHIF-1α and HIF-1α, but not the mutant one (Fig. 5F). It is interesting to note that the expression of circHIF-1α, miR-375 and HIF-1α showed a strong correlation with each other according to the RT-qPCR experiment (Fig. 5G). Taken together, the above results demonstrate that circHIF-1α in the cytoplasm increases the mRNA level of HIF-1α by acting as a sponge for miR-375.

Fig. 5.

Cytoplasmic circHIF-1α increased the mRNA level of HIF-1α via sponging miR-375. (A) Venn diagram of differentially potential miRNAs regulated by circHIF-1α that can bind with HIF-1α identified in Circinteractome and TargetScan. (B) CircHIF-1α probes were used to analyze the enrichment of miR-375, miR-892a, miR-636, and miR-607. (C) miR-375 expression was detected by RT-qPCR in PC cells with circHIF-1α gain or loss. (D) HIF-1α expression was detected by RT-qPCR in PC cells with miR-375 gain or loss. (E) CircHIF-1α was significantly enriched in the miR-375 probes. (F) Binding sites between circHIF-1α, miR-375, and HIF-1α are shown. (G) Luciferase activity assay was used to detect the binding between circHIF-1α, miR-375, and HIF-1α. (H) RT-qPCR was used to evaluate the relationship between circHIF-1α, miR-375, and HIF-1α expression. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

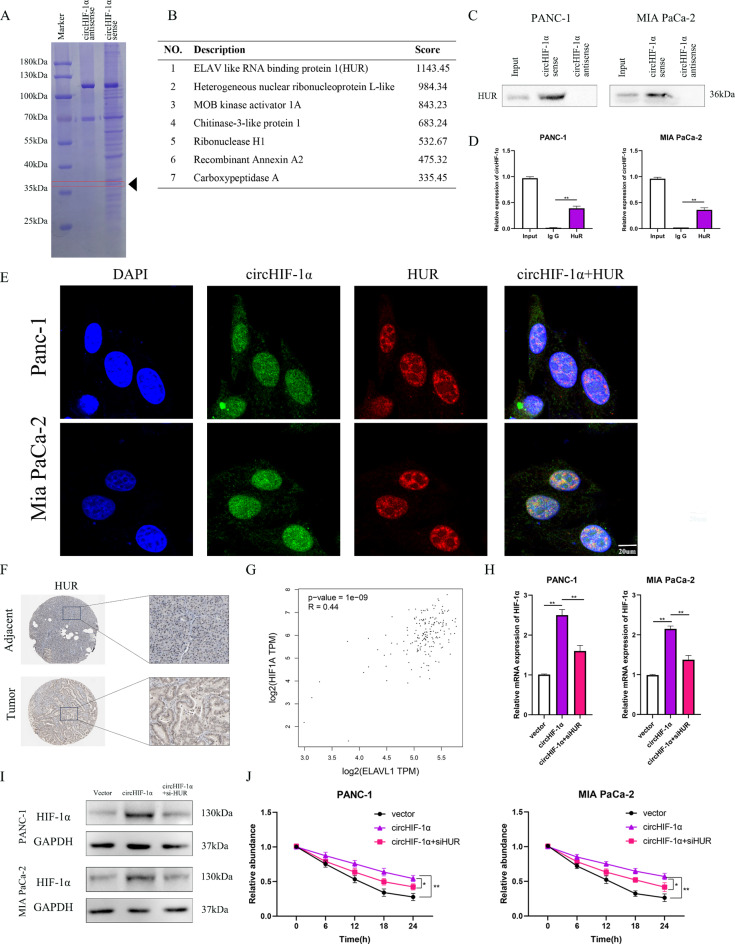

Nuclear circHIF-1α increased the stability of HIF-1α mRNA by recruiting HUR

As circHIF-1α regulates tumor growth and metastasis via protein interactions, we employed a biotin-labeled RNA pull-down combined with Coomassie brilliant blue staining and mass spectrometry (MS) to identify proteins that bind to circHIF-1α in PC cells. A distinct protein band of approximately 36 kDa, was detected by Coomassie brilliant blue staining and subsequently characterized by MS (Fig. 6A). Multiple proteins emerged as potential interaction partners for circHIF-1α, with HUR emerging as the top candidate based on its high score (Fig. 6B). The direct association between circHIF-1α and HUR was verified using immunoprecipitation with an anti-HUR antibody (Fig. 6C) and RIP assay (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, an immunofluorescence (IF) assay demonstrated the colocalization of endogenous circHIF-1α and HUR within the nucleus, and a confocal laser scanning microscope was used for these images (Fig. 6E). IHC analysis from HPA revealed a positive correlation between HUR and HIF-1α expression in PC tissues (Fig. 6F). This positive association was further supported by data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (Fig. 6G). In PC cells overexpressing circHIF-1α and treated with HUR siRNA, the positive feedback effects of circHIF-1α on HIF-1α protein and mRNA levels were notably suppressed (Fig. 6H-I). Cells with elevated circHIF-1α levels exhibited enhanced HIF-1α stability compared to the control group. Conversely, reducing HUR expression in circHIF-1α-overexpressing cells led to a significant decrease in HIF-1α mRNA rates (Fig. 6J). Collectively, these findings suggested that circHIF-1α physically interacts with HUR to upregulate HIF-1α mRNA expression by enhancing its stability.

Fig. 6.

Nuclear circHIF-1α increased the stability of HIF-1α mRNA by recruiting HUR. (A-B) The result of RNA pull-down combined with Coomassie brilliant blue staining and mass spectrometry (MS) demonstrated that HUR significantly bound to circHIF-1α. (C) RNA pull-down and western blotting were used to confirm the binding of circHIF-1α to HUR. (D) HUR antibodies were used to evaluate the circHIF-1α enrichment. (E) Confocal experiments were used to observe the co-localization of circHIF-1α and HUR in the cell nucleus. (F) Expression of HUR in PC tissues and adjacent normal tissues based on the data from HPA. (G) The relationship between circHIF-1α and HUR was determined according to the data from TCGA. (H–I) HIF-1α expression was detected using RT-qPCR and western blotting in PC cells with circHIF-1α overexpression plus HUR knockdown. (J) The stability of HIF-1α mRNA was evaluated in PC cells with circHIF-1α overexpression plus HUR knockdown. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.015

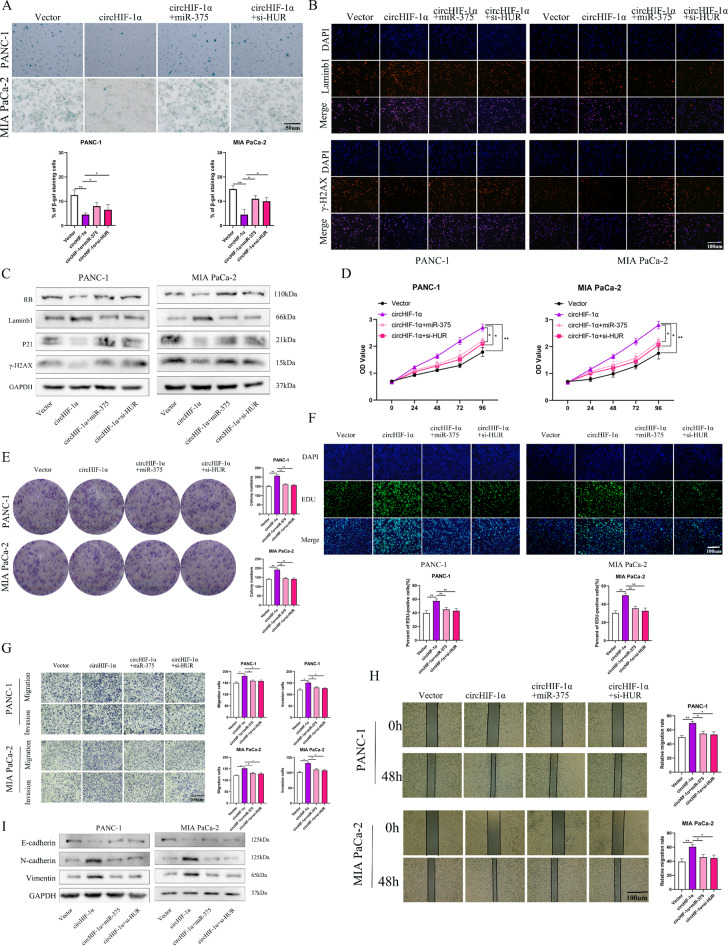

CircHIF-1α delayed senescence, and promoted the proliferation, and motility in vitro via miR-375 and HUR

In subsequent studies, to further confirm the precise role of circHIF-1α in PC cell functions, we designed a series of functional rescue experiments. Overexpression of circHIF-1α decreased the number of SA-β-Gal-positive cells. There was a rescue trend in response to the miR-375 mimic and HUR knockdown in PC cells (Fig. 7A). In PC cells co-transfected with circHIF-1α lentivirus/miR-375 mimic and circHIF-1α lentivirus/HUR siRNA, the decreased levels of lambin1 and the increased levels of γ-H2AX were also clearly visible in immunofluorescence staining compared to cells transfected with circHIF-1α lentivirus, which were reversed after interference with miR-375 and HUR (Fig. 7B). Western blotting showed the similar result (Fig. 7C). The CCK8 and colony formation assays showed that the miR-375 mimic and HUR inhibition abrogated the proliferation-promoting effects induced by circHIF-1α overexpression in PC cells (Fig. 7D-E). Similar results were obtained in the EDU assay (Fig. 7F). Meanwhile, both wound healing and transwell assays showed that the acceleration of proliferation, migration and invasive ability in PC cells induced by overexpression of circHIF-1α was also partially abolished by miR-375 mimic and HUR siRNA (Fig. 7G-H). Changes in EMT-related proteins in were reversed PC cells with circHIF-1α overexpression were reversed by miR-375 mimic and HUR siRNA (Fig. 7I).

Fig. 7.

CircHIF-1α delayed senescence and promoted the proliferation and motility of PC cells in a miR-375- and HUR-dependent manner. The rescue effects of miR-375 mimic and HUR knockdown on circHIF-1α- overexpressing lentivirus. (A) Total cells and β-Gal staining positive cells were counted, and the percentage of β-Gal staining positive cells was calculated in each group of PC cells. (B) Immunofluorescence experiments verified the expression of senescence-related biomarkers in each group, including laminb1 and γ-H2AX. (C) The expression of RB, laminb1, γ-H2AX and P21 was examined using western blotting in each group. (D) The CCK-8 assay was used to determine the rate of PC cell proliferation in each group. (E) Colony formation assay was used to detect colony formation in each group. (F) EDU assay was performed to detect the rate of EDU positivity in each group. (G-H) Wound healing and transwell assays were used to determine the rates of migration and invasion in each group. (I) The expression of EMT markers was examined using western blotting in each group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

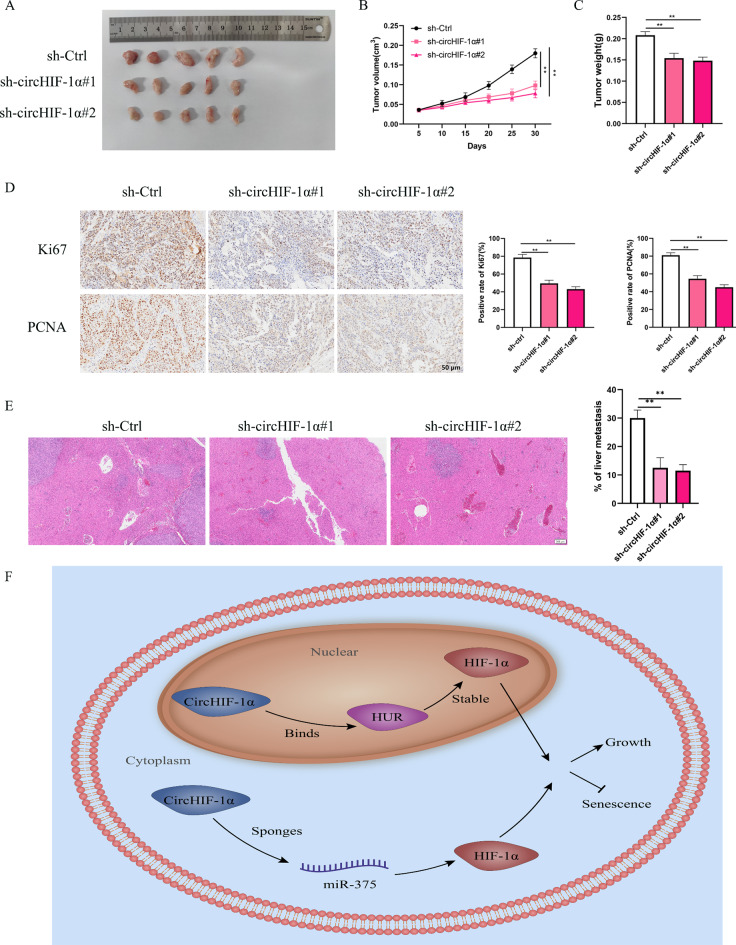

CircHIF-1α promoted the proliferation and metastasis of PC cells in vivo

We created both a xenograft tumor model and a spleen capsule-injected liver metastasis model, which allowed us to delve deeper into the possible effects of circHIF-1α on PC cells. By administering cholesterol-linked circHIF-1α-knockdown plasmid directly into the tumors of nude mice with PC, we observed that the absence of circHIF-1α led to a notable retardation in tumor progression (Fig. 8A-C). Immunohistochemical (IHC) examination further revealed a reduction in Ki-67 and PCNA levels in the group treated with the circHIF-1α-knockdown plasmid compared with the untreated controls (Fig. 8D). The RT-qPCR experiment also revealed a reduction in circHIF-1α and HIF-1α levels in the group treated with the circHIF-1α-knockdown plasmid compared with the untreated controls (Supplementary Fig.S2A). Additionally, liver tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (hue) (H&E) indicated that a decrease in circHIF-1α expression hampered liver metastasis when compared to the negative control group (Fig. 8E). In conclusion, our xenograft tumor model experiments confirmed that suppressing circHIF-1α mitigated the proliferative capabilities of PC in living organisms.

Fig. 8.

CircHIF-1α promoted the proliferation of PC cells in vivo. (A-B) The rate of proliferation in tissues with circHIF-1α knockdown. (C) The weight of tumor tissues with circHIF-1α knockdown. (D) The expression of PCNA and Ki67 was determined in tumor tissues with circHIF-1α knockdown using immunohistochemical staining. (E) A metastatic liver model was used to detect the metastatic ability of PANC-1 cells with circHIF-1α knockdown. (F) Schematic diagram of circHIF-1α facilitates tumor progression of PC. **p < 0.01

Discussion

CircRNA, a circular non-coding RNA lacking the 5’ and 3’ ends, plays a significant role in the progression and metastasis of tumor cells [21]. CircRNAs come in three primary forms: exonic (ecircRNA), exon-intron hybrids (EIcircRNA), and intronic (ciRNA), with intergenic circRNAs also existing [22]. These circular transcripts exhibit diverse localization within subcellular domains, and a significant portion of them demonstrate stability and conservation across various species [23]. CircRNAs are able to regulate the development of PC in multiple ways. In our study, we demonstrated that circHIF-1α could regulate senescence, tumor growth and aggressiveness by interacting with miR-375 and HUR to modulate the expression of HIF-1α.

To some extent, cellular senescence has an inhibitory effect on tumour growth [24]. CHING et al. found that in the AY-27 mouse bladder cancer cell line and a mouse model of bladder cancer, the tumour suppressor gene WWOX (an ROS-dependent senescence-inducible gene) induced cellular senescence to inhibit bladder cancer growth [25]. CircRNAs have recently attracted attention for their role in regulating various cellular processes [26]. The specific expression of circRNAs in tumour cells is closely linked to the process of tumour cell senescence [27]. Meanwhile, a link between altered circRNAs and the pathogenesis of PC has been identified in recent studies [28]. In particular, the role of circRNAs in cellular senescence during the development of tumors has yet to be elucidated. Here, we investigated the differentially expressed circRNAs in control and DOX-induced senescent PC cells using RNA-seq. In senescent PCs, a novel circ RNA, circHIF-1α (hsa_circ_0007976), was found to be reduced. Interestingly, circHIF-1α was found to be significantly enriched in PC tissues and cell lines when compared to adjacent normal tissues and pancreatic epithelial cells, suggesting that circHIF-1α may be involved in regulating the function of pancreatic cancer. Our data showed that circHIF-1α overexpression attenuated senescence and promoted PC proliferation. Conversely, circHIF-1α knockdown had the opposite effects. Also, the expression of circHIF-1α is associated with the prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Our findings suggest that circHIF-1α is a novel senescence -associated circRNA that plays an important role in PC.

Previous researches have demonstrated that circRNAs competitively bind miRNAs to modulate the expression of downstream target genes [29]. This enables circRNA to engage in a competition with mRNA for miRNA binding, functioning as a so-called competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA). MicroRNAs (miRNAs), consisting of single-strand, non-coding RNA molecules with a length of 18 to 25 nucleotides, play a pivotal role in the post-transcriptional modulation of gene expression. They impact mRNA stability and translational processes, thereby exerting their influence across a wide spectrum of complex organisms [30]. For example, in colorectal cancer, circ-ITGA7 upregulates its linear isoform, ITGA7, via the miR-370-3p/neurofibromin 1/Ras pathway [31]. Kong et al. found that circNFIB1 was able to inhibit pancreatic cancer lymphatic metastasis by competitively binding to miR-486-5p, thereby upregulating the expression of PIK3R1 [32]. Circ-PDE8A promotes PC invasion via the miR-338/MACC1/MET signaling axis [33]. Inhibition of hsa_circ_0000977 promoted miR-874-3p expression and inhibited PLK1-mediated pancreatic cancer development [34]. It has also been reported that there is a relationship between circRNAs and biological functions in cells via regulating its parental gene expression [35]. Therefore, we considered that the effect of circHIF-1α on PC progression via modulating HIF-1α expression. Consistent with our suspicions, HIF-1α was significantly downregulated following oncogenic circHIF-1α knockdown. In some contexts, HIF-1a-dependent mechanisms have been implicated in the suppression of cellular senescence [36]. Meanwhile, overexpression of HIF-1α in pancreatic cancer tissues promotes tumour progression, invasion and metastasis and is strongly correlated with the sensitivity to pancreatic cancer chemotherapy [37]. In this study, depletion of HIF-1α attenuated the effect of circHIF-1α overexpression on PC growth and senescence. Given its cytoplasmic location, we speculated that circHIF-1α may act as a miRNA sponge to regulate its parent. According to bioinformatics analyses, a conserved miR-375 target site was validated by luciferase assays and molecular biological experiments. The exploration of miR-375 initially emerged in the context of pancreatic endocrine cells, where it was initially cloned and recognized as a distinctive islet-specific miRNA and rapidly becomes an emerging research hot spot later [38]. We also found that the upregulation of miR-375 significantly rescued the increased proliferation rate and decreased cellular senescence induced by circHIF-1α overexpression, implying that circHIF-1α could sponge miR-375, which directly interacts with its host gene to affected cellular senescence and proliferation.

In addition to competing with endogenous RNA, the role of circRNAs as protein sponges has been shown to be closely linked to tumour development [39]. To determine the nuclear mechanism of circHIF-1α, we found that circHIF-1α binds to and co-localizes with HUR through mass spectrometry analysis. HUR is an important RNA-binding protein that is widely expressed in various tissues [40]. HUR is mainly located in the nucleus and binds to the mRNA of the target gene, forming a complex that prevents the mRNA degradation [41]. Recent studies have shown that HUR is closely linked to the development of inflammatory diseases [42] and plays an important role in the regulation of cell division, cellular senescence, immune cell activation and other vital activities in tumours via regulating the stability and translational efficiency of mRNA [43, 44]. Interestingly, we found that nuclear-localized circHIF-1α could directly interact with HUR to coordinately increase HIF-1α mRNA stability. In this study, overexpression of circHIF-1α delayed senescence and aggravated growth in PC cells, whereas the effect of circHIF-1α was ameliorated by HUR knockdown. Taken together, our study displayed that HUR could bind to circHIF-1α and HIF-1α. is associated with circHIF-1α- mediated cellular senescence and proliferation in PC.

To summary, our study provides a portrayal of the role of senescence-associated circHIF-1α in the inhibition of PC progression. Mechanistic studies showed that circHIF-1α delayed cellular senescence, thereby promoting PC progression via the miR-375/HIF-1α and HUR /HIF-1α axis. This makes circHIF-1α a potential therapeutic candidate for the treatment of PC.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 2: Figure. S1 (A-B) Detection of senescence representative images of SA-β-Gal staining by time and concentration in DMSO-treated and DOX-treated PANC-1 cells.

Supplementary Material 3: Figure. S2 A. The expression of circHIF-1α and HIF-1α were determined in tumor tissues with circHIF-1α knockdown using RT-qPCR.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the authors of the primary studies.

Abbreviations

- circHIF-1α

Circular RNA hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- RBP

RNA binding protein

- miRNA

microRNA

- IF

Immunofluorescence

- FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- gDNA

Genomic DNA

- cDNA

Complementary DNA

- ceRNA

Competitive endogenous RNA

- circRNA

Circular RNA

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- RIP

RNA immunoprecipitation

- HUR

Human antigen R protein

- PC

Pancreatic cancer

- SA-β-Gal

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase

- CCK-8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- EdU

5-Ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine

- IHC

Immunohistochemical streptavidin-peroxidase staining

- HE

Hematoxylin and eosin

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- RT-qPCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- WB

Western blotting

- GEPIA

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis

- FBS

Foetal bovine serum

- DOX

Doxorubicin

- EDU

5-Ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- EMT

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- HPA

The Human Protein Atlas

Author contributions

Hua Hao: Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Deng Yazu: Conceptualization, Methodology. Zheng Dijie: Visualization, Investigation. Chen Liwen and Shi Binbin: Software, Validation. He Zhiwei: Supervision. Yu Chao: Writing- Reviewing and Editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This article was financially supported by the following funds: the National Nature Science Foundation of China [grant number: 82360519]; Hundred-Level Personnel (Qiankehe Platform Talents-GCC[2023]082); Discipline Leading Personnel in 2023 (gyfyxkyc-2023-03).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed after approval by the ethics committee of Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University. Pancreatic cancer specimens were obtained from patients undergoing surgical resection at Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University. All experiments involving human specimens were approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University. Written informed consent from the donors for the research use of tissues in this study were obtained prior to the acquisition of the specimens. All animal experimentation protocols and procedures were approved by the Animal Committees of Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to publish.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hao Hua and Yazhu Deng have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Zhiwei He, Email: 2268272794@qq.com.

Chao Yu, Email: yuchao2002@gmc.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Pisignano G, Michael DC, Visal TH, Pirlog R, Ladomery M, Calin GA. Going circular: history, present, and future of circRNAs in cancer. Oncogene. 2023;42(38):2783–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao B, Li Z, Qin C, Li T, Wang Y, Cao H, Yang X, Wang W. Mobius strip in pancreatic cancer: biogenesis, function and clinical significance of circular RNAs. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(17–18):6201–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Q, Li J, Shen P, Yuan H, Yin J, Ge W, Wang W, Chen G, Yang T, Xiao B, et al. Biological functions, mechanisms, and clinical significance of circular RNA in pancreatic cancer: a promising rising star. Cell Biosci. 2022;12(1):97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Al Hallak MN, Philip PA, Azmi AS, Mohammad RM. Non-Coding RNAs in Pancreatic Cancer Diagnostics and Therapy: Focus on lncRNAs, circRNAs, and piRNAs. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(16). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Lin Z, Lu S, Xie X, Yi X, Huang H. Noncoding RNAs in drug-resistant pancreatic cancer: a review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;131:110768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bao H, Li J, Dong Q, Liang Z, Yang C, Xu Y. Circular RNAs in pancreatic cancer progression. Clin Chim Acta. 2024;552:117633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong CH, Lou UK, Fung FK, Tong JHM, Zhang CH, To KF, Chan SL, Chen Y. CircRTN4 promotes pancreatic cancer progression through a novel CircRNA-miRNA-lncRNA pathway and stabilizing epithelial-mesenchymal transition protein. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi X, Yang J, Liu M, Zhang Y, Zhou Z, Luo W, Fung KM, Xu C, Bronze MS, Houchen CW, et al. Circular RNA ANAPC7 inhibits Tumor Growth and muscle wasting via PHLPP2-AKT-TGF-β Signaling Axis in Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(7):2004–17. e2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Xu S, Liu X, Jiang X, Jiang J. CircSEC24A upregulates TGFBR2 expression to accelerate pancreatic cancer proliferation and migration via sponging to miR-606. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Chen M, Fang L. hsa_circ_0068631 promotes breast cancer progression through c-Myc by binding to EIF4A3. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;26:122–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu S, Li B, Xia Y, Xuan Z, Li Z, Xie L, Gu C, Lv J, Lu C, Jiang T, et al. CircTHBS1 drives gastric cancer progression by increasing INHBA mRNA expression and stability in a ceRNA- and RBP-dependent manner. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(3):266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muñoz-Espín D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(7):482–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. Hallmarks of aging: an expanding universe. Cell. 2023;186(2):243–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng Q, Ouyang X, Zhang R, Zhu L, Song X. Senescence-associated genes and non-coding RNAs function in pancreatic cancer progression. RNA Biol. 2020;17(11):1693–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang D, Yang K, Yang M. Circular RNA in Aging and Age-Related diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1086:17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Min X, Cai MY, Shao T, Xu ZY, Liao Z, Liu DL, Zhou MY, Wu WP, Zhou YL, Mo MH, et al. A circular intronic RNA ciPVT1 delays endothelial cell senescence by regulating the miR-24-3p/CDK4/pRb axis. Aging Cell. 2022;21(1):e13529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du WW, Yang W, Chen Y, Wu ZK, Foster FS, Yang Z, Li X, Yang BB. Foxo3 circular RNA promotes cardiac senescence by modulating multiple factors associated with stress and senescence responses. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(18):1402–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Z, Zuo X, Pu L, Zhang Y, Han G, Zhang L, Wu J, Wang X. circLARP4 induces cellular senescence through regulating miR-761/RUNX3/p53/p21 signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2019;110(2):568–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He Z, Cai K, Zeng Z, Lei S, Cao W, Li X. Autophagy-associated circRNA circATG7 facilitates autophagy and promotes pancreatic cancer progression. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(3):233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan L, Zhang L, Fan K, Cheng ZX, Sun QC, Wang JJ. Circular RNA-ITCH Suppresses Lung Cancer Proliferation via Inhibiting the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016;1579490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Meng S, Zhou H, Feng Z, Xu Z, Tang Y, Li P, Wu M. CircRNA: functions and properties of a novel potential biomarker for cancer. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang P, Chao Z, Zhang R, Ding R, Wang Y, Wu W, Han Q, Li C, Xu H, Wang L et al. Circular RNA regulation of Myogenesis. Cells. 2019;8(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Zhou MY, Yang JM, Xiong XD. The emerging landscape of circular RNA in cardiovascular diseases. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;122:134–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyasaka Y, Nagai E, Ohuchida K, Fujita H, Nakata K, Hayashi A, Mizumoto K, Tsuneyoshi M, Tanaka M. Senescence in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Hum Pathol. 2011;42(12):2010–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu CW, Chen PH, Yu TJ, Lin KJ, Chang LC. WWOX modulates ROS-Dependent senescence in bladder Cancer. Molecules. 2022;27(21). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Barrett SP, Salzman J. Circular RNAs: analysis, expression and potential functions. Development. 2016;143(11):1838–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang Y, Jiang M, Jiang HM, Ye ZJ, Huang YS, Li XS, Qin BY, Zhou RS, Pan HF, Zheng DY. The roles of circRNAs in Liver Cancer immunity. Front Oncol. 2020;10:598464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Li Z, Jiang P, Peng M, Zhang X, Chen K, Liu H, Bi H, Liu X, Li X. Circular RNA IARS (circ-IARS) secreted by pancreatic cancer cells and located within exosomes regulates endothelial monolayer permeability to promote tumor metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kristensen LS, Andersen MS, Stagsted LVW, Ebbesen KK, Hansen TB, Kjems J. The biogenesis, biology and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(11):675–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruggieri F, Jonas K, Ferracin M, Dengler M, Jӓger V, Pichler M. MicroRNAs as regulators of tumor metabolism. Endocrine-related Cancer. 2023;30(8). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Li X, Wang J, Zhang C, Lin C, Zhang J, Zhang W, Zhang W, Lu Y, Zheng L, Li X. Circular RNA circITGA7 inhibits colorectal cancer growth and metastasis by modulating the Ras pathway and upregulating transcription of its host gene ITGA7. J Pathol. 2018;246(2):166–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kong Y, Li Y, Luo Y, Zhu J, Zheng H, Gao B, Guo X, Li Z, Chen R, Chen C. circNFIB1 inhibits lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis via the miR-486-5p/PIK3R1/VEGF-C axis in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Yanfang W, Li J, Jiang P, Peng T, Chen K, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Zhen P, Zhu J, et al. Tumor-released exosomal circular RNA PDE8A promotes invasive growth via the miR-338/MACC1/MET pathway in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;432:237–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang WJ, Wang Y, Liu S, Yang J, Guo SX, Wang L, Wang H, Fan YF. Silencing circular RNA hsa_circ_0000977 suppresses pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression by stimulating mir-874-3p and inhibiting PLK1 expression. Cancer Lett. 2018;422:70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X, Lu N, Wang L, Wang Y, Li M, Zhou Y, Yan H, Cui M, Zhang M, Zhang L. Circular RNAs and esophageal cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20:362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsai CC, Chen YJ, Yew TL, Chen LL, Wang JY, Chiu CH, Hung SC. Hypoxia inhibits senescence and maintains mesenchymal stem cell properties through down-regulation of E2A-p21 by HIF-TWIST. Blood. 2011;117(2):459–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamada S, Matsumoto R, Masamune A. HIF-1 and NRF2; key molecules for malignant phenotypes of pancreatic Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, Kuwajima S, Ma X, Macdonald PE, Pfeffer S, Tuschl T, Rajewsky N, Rorsman P, et al. A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature. 2004;432(7014):226–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang S, Li Z, Zhu G, Hong L, Hu C, Wang K, Cui K, Hao C. RNA-binding protein IGF2BP2 enhances circ_0000745 abundancy and promotes aggressiveness and stemness of ovarian cancer cells via the microRNA-3187-3p/ERBB4/PI3K/AKT axis. J Ovarian Res. 2021;14(1):154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu X, Xu L. The RNA-binding protein HuR in human cancer: a friend or foe? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022;184:114179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blanco FF, Jimbo M, Wulfkuhle J, Gallagher I, Deng J, Enyenihi L, Meisner-Kober N, Londin E, Rigoutsos I, Sawicki JA, et al. The mRNA-binding protein HuR promotes hypoxia-induced chemoresistance through posttranscriptional regulation of the proto-oncogene PIM1 in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene. 2016;35(19):2529–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shao Z, Tu Z, Shi Y, Li S, Wu A, Wu Y, Tian N, Sun L, Pan Z, Chen L, et al. RNA-Binding protein HuR suppresses inflammation and promotes Extracellular Matrix Homeostasis via NKRF in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:611234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zucal C, D’Agostino V, Loffredo R, Mantelli B, NatthakanThongon, Lal P, Latorre E, Provenzani A. Targeting the multifaceted HuR protein, benefits and caveats. Curr Drug Targets. 2015;16(5):499–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De S, Das S, Sengupta S. Involvement of HuR in the serum starvation induced autophagy through regulation of Beclin1 in breast cancer cell-line, MCF-7. Cell Signal. 2019;61:78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 2: Figure. S1 (A-B) Detection of senescence representative images of SA-β-Gal staining by time and concentration in DMSO-treated and DOX-treated PANC-1 cells.

Supplementary Material 3: Figure. S2 A. The expression of circHIF-1α and HIF-1α were determined in tumor tissues with circHIF-1α knockdown using RT-qPCR.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.