Abstract

Polygenic prediction of complex trait phenotypes has become important in human genetics, especially in the context of precision medicine. Recently, mr.mash, a flexible and computationally efficient method that models multiple phenotypes jointly and leverages sharing of effects across such phenotypes to improve prediction accuracy, was introduced. However, a drawback of mr.mash is that it requires individual-level data, which are often not publicly available. In this work, we introduce mr.mash-rss, an extension of the mr.mash model that requires only summary statistics from Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and linkage disequilibrium (LD) estimates from a reference panel. By using summary data, we achieve the twin goal of increasing the applicability of the mr.mash model to data sets that are not publicly available and making it scalable to biobank-size data. Through simulations, we show that mr.mash-rss is competitive with, and often outperforms, current state-of-the-art methods for single- and multi-phenotype polygenic prediction in a variety of scenarios that differ in the pattern of effect sharing across phenotypes, the number of phenotypes, the number of causal variants, and the genomic heritability. We also present a real data analysis of 16 blood cell phenotypes in the UK Biobank, showing that mr.mash-rss achieves higher prediction accuracy than competing methods for the majority of traits, especially when the data set has smaller sample size.

Author summary

Polygenic prediction refers to the use of an individual’s genetic information (i.e., genotypes) to predict traits (i.e., phenotypes), which are often of medical relevance. It is known that some phenotypes are related and are affected by the same genotypes. When this is the case, it is possible to improve the accuracy of predictions by using methods that model multiple phenotypes jointly and account for shared effects. mr.mash is a recently developed multi-phenotype method that can learn which effects are shared and has been shown to improve prediction. However, mr.mash requires large data sets of genetic and phenotypic information collected at the individual level. Such data are often unavailable due to privacy concerns, or are difficult to work with due to the computational resources needed to analyze data of this size. Our work extends mr.mash to require only summary statistics from Genome-Wide Association Studies, which are usually publicly available, instead of individual-level data. In addition, the computations using summary statistics do not depend on sample size, making the newly developed mr.mash-rss scalable to extremely large data sets. Using simulations and real data analysis, we show that our method is competitive with other methods for polygenic prediction.

Introduction

Predicting complex trait phenotypes from genotypes is a central task of a few branches of quantitative genetics. In agricultural breeding, there is interest in predicting breeding values (EBV) to select the best individuals for reproduction and achieve an increase in performance over generations [1]. In human genetics, predicting medically relevant phenotypes such as disease risk via polygenic scores (PGS) is important to stratify the population and identify individuals with greater genetic risk [2]. Finally, with the advent of transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS), predicting gene expression as an intermediate step has become of interest [3]. In all these applications, accurate predictions are important. The response to artificial selection is directly proportional to the accuracy of EBVs [4]. Precise identification of individuals at risk for a particular disease requires accurate PGS [2]. The power to discover gene-phenotype associations in TWAS depends on the accuracy of gene expression prediction [5].

Technically, phenotypic prediction is achieved by modeling the phenotype of interest as a multiple regression on genotypes at a set of genetic variants [6]. Both frequentist and Bayesian approaches to multiple regression have been developed for and/or applied to this task, with accuracy spanning from very low to high depending on the genetic architecture of the trait analyzed [7–12]. Multiple phenotypes may be genetically correlated due to pleiotropy (i.e., the sharing of causal variants across traits). In that case, modeling these phenotypes jointly via multivariate multiple regression methods can improve effect sizes estimates by leveraging effect sharing and, thus, increase prediction accuracy [13–17]. Integrative approaches that combine multiple single-phenotype PGSs across phenotypes have also been shown to improve prediction accuracy [18, 19].

Recently, Morgante et al. (2023) introduced the “Multiple Regression with Multivariate Adaptive Shrinkage” or “mr.mash” [20]. mr.mash is a Bayesian approach to multivariate multiple regression that is able learn complex patterns of effect sharing across phenotypes directly from the data. This is achieved through the use of flexible priors on the effect sizes across phenotypes and an empirical Bayes (EB) framework to adapt these priors to the data. Computational effiency is achieved by using Variational Inference (VI) as opposed to the more expensive Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods. For a detailed account of VI and EB in this context, including the advantages, we direct the reader to [20]. Using multi-tissue gene expression prediction from cis-genotypes as an example, the authors showed that mr.mash is competitive in terms of both prediction accuracy and speed [20]. However, while powerful, mr.mash has some limitations. First, mr.mash requires individual-level data, i.e., genotypes and phenotypes for each individual and, mainly for privacy reasons, these data are rarely publicly available [21]. Second, mr.mash does not scale well to datasets with very large sample size, such as modern biobanks. These weaknesses limit the use of mr.mash for PGS prediction in human genetics.

In this work, we overcome both these limitations by introducing “mr.mash Regression with Summary Statistics” or “mr.mash-rss”, an extension of mr.mash that only requires summary-level data. These are effect sizes and their standard errors (or Z-scores) from univariate Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWASs) and Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) estimates from reference panels, which are usually publicly available [21]. mr.mash-rss shares some features with the established Multivariate Adaptive Shrinkage (mash) [22], in that they both use the same mixture-of-multivariate-Normals prior on the effect sizes to leverage effect sharing across conditions (e.g., different phenotypes), and the EB approach to adapt the prior to the data. In fact, both mr.mash and mr.mash-rss “borrow” this framework that was introduced with mash. However, while mash assumes that the input summary statistics come from independent variables (i.e., it does not deal with LD), mr.mash-rss takes a full multivariate multiple regression approach and adjusts effect sizes for both sharing across conditions and correlations among variables (i.e., it takes LD into account). We test mr.mash-rss in the task of PGS prediction for multiple phenotypes jointly via simulations in several scenarios and show that it is competitive in terms of prediction accuracy with currently available methods. We then confirm these results in the analysis of real data for 16 blood cell traits in the UK Biobank [23, 24].

Description of the method

The multivariate multiple regression is used to model the effects of several predictor variables X on multiple responses Y jointly:

| (1) |

where is the response matrix for r responses (phenotypes in our case) in n individuals, is the predictor matrix for p predictors (genetic variants in our case) in n individuals, is the matrix of effects for p predictors and r responses, and , is the matrix of residuals for r responses for n individuals. The residuals follow a Matrix Normal distribution with mean 0 (an n × r matrix of zeroes), covariance across individuals In (an n × n identity matrix), and covariance across responses V (an r × r positive definite matrix).

mr.mash adopts a Bayesian approach by imposing a prior on the effects:

| (2) |

where bj is an r-vector that captures the effects of predictor j, and is the jth row of B. Thus, the effects are assumed to be identically distributed as a mixture of r-variate Normals with K components. The prior is determined by w0 ≔ (w0,1, …, w0,K), the set of non-negative mixture weights, and , the set of r × r covariance matrices across responses. The elements of are prespecified and are intended to capture plausible patterns of effect sharing across responses [20].

To make the model fit computationally efficient for large datasets, mr.mash approximates , the true posterior distribution of the regression coefficients, through variational inference, which uses optimization techniques to find the best approximation within a chosen family of distributions [25]. The optimal approximation is determined by maximizing the evidence lower bound (ELBO), a lower bound on the model’s marginal likelihood. In addition, mr.mash also estimates w0 (and V) from the data by maximizing the ELBO, thereby adapting the prior to the data. This whole procedure has been termed variational empirical Bayes [26].

Extension of mr.mash to summary statistics

Following the approach of [27], we express the updates in mr.mash in terms of sufficient statistics. The likelihood for the mr.mash model is

| (3) |

We can see that X⊺X, X⊺Y, and Y⊺Y are sufficient statistics for the likelihood. Thus, the mr.mash model can be fitted using expressions based only on these sufficient statistics (see S1 Text for detailed derivations) to obtain the same results as using individual-level data X and Y.

The sufficient statistics can be recovered from effect sizes and their standard errors (or Z-scores) from GWAS and LD estimates, following steps provided in [27] and S1 Text. We call mr.mash with summary statistics mr.mash-rss. However, it should be noted that while X⊺Y can be recovered exactly, X⊺X is only approximated when LD estimates come from reference panels, rather than from the data that generated GWAS summary statistics [27]. Thus, using summary data can be seen as fitting the mr.mash model using an approximation to the likelihood in 3 [27]. The quality of the approximation depends on how closely the LD reference panel matches the GWAS summary statistics. Quality control should therefore be performed on summary statistics and LD before model fitting [27, 28]. In addition, Y⊺Y may not be available. However, this quantity is not strictly necessary, unless V is estimated within the mr.mash-rss algorithm [27]. While mr.mash has a way to deal with missing values in Y, mr.mash-rss assumes the summary statistics be computed using the same individuals for each response (i.e., there are no missing values in Y).

The methods introduced in this paper are implemented in the package [29] mr.mash.alpha which is available for download at https://github.com/stephenslab/mr.mash.alpha.

Verification and comparison

Simulations using UK Biobank genotypes

We devised a simulation study where the goal was to compare mr.mash-rss and other competing methods at computing PGS for multiple phenotypes from summary data. We used real genotypes from the UK Biobank array data for n = 105, 000 nominally unrelated White British individuals that were randomly sampled. After applying a series of filters (see S1 Text for details), the data included p = 595, 071 genetic variants.

We simulated r = 5 phenotypes according to three scenarios that differed in the structure of the effect sharing across phenotypes. Causal variants (5,000 for all scenarios) were randomly sampled from all genetic variants.

-

1

“Equal Effects”, where each causal variant affects all the phenotypes and has the same effect across phenotypes. The per-phenotype proportion of variance explained by the causal variants or genomic heritability () is equal to 0.5.

-

2

“Mostly Null”, where the causal variants affect only the first phenotype with equal to 0.5, while the remaining phenotypes are affected only by a non-genetic component (i.e., )

-

3

“Shared Effects in Subgroups”, where the effect of each causal variant is drawn such that it is equally likely to be shared (but not be equal) in phenotypes 1 through 3 or to be shared (but not be equal) in phenotypes 4 and 5. The per-phenotype is 0.3 in phenotypes 1–3 and 0.5 in phenotypes 4 and 5.

These three scenarios were similar to those used in [20], but some parameters (e.g., number of causal variants) were modified to reflect more closely the genetic architecture of complex traits, rather than gene expression. We also simulated a few scenarios based on the Equal Effects scenario (i.e., equal effects of the causal variants across phenotypes) to assess the effect of genomic heritability, polygenicity (i.e., number of causal variants), and number of phenotypes modeled on the performance of the methods:

-

4

“Low ”, where the per-phenotype is 0.2.

-

5

“High Polygenicity”, where the number of causal variants is 50,000.

-

6

“More Phenotypes”, where the number of simulated phenotypes is 10.

For each of the scenarios above, we simulated 20 replicates. Per-phenotype prediction accuracy was computed as the R2 from the linear regression of the true phenotypes on the predicted phenotypes for the test set individuals, which consisted of 5,000 randomly sampled individuals from the total of 105,000. This metric has the attractive property that its upper bound is [30].

Methods compared

We compared mr.mash-rss to a few competing methods that satisfied the following requirements: (1) can be fitted with only summary data; (2) do not require a validation data set to tune model parameters; (3) for multivariate methods, are able to model at least 5 phenotypes jointly. This resulted in the choice of the following methods:

-

1

LDpred2-auto. This is a univariate Bayesian method that imposes a two-component mixture prior on the regression coefficients, consisting of a point-mass at 0 and a zero-centered Normal distribution [10]. This method is labelled “LDpred2” in the results.

-

2

SBayesR. This is a univariate Bayesian method that imposes a four-component mixture prior on the regression coefficients, consisting of a point-mass at 0 and three zero-centered Normal distributions, each with a different variance [9]. This method is labelled “SBayesR” in the results.

-

3

SmvBayesC. This is a multivariate Bayesian method that imposes a two-component mixture prior on the regression coefficients across phenotypes, consisting of a point-mass at 0 and a zero-centered multivariate Normal distribution [31, 32]. This method allows for each genetic variant to affect any combination of phenotypes. This method is labelled “SmvBayesC” in the results. We also tested a “restrictive” version that allows for each genetic variant to affect all or none of the phenotypes only [14, 31]. This method is labelled “SmvBayesC-rest” in the results.

We also included two 2-step approaches:

-

4

MTAG+LDpred2-auto. The first step uses MTAG, which is a multivariate method that adjusts univariate ordinary least squares (OLS) summary statistics based on the (estimated) correlation between the effects across phenotypes [33]. Because MTAG does not account for LD between variants, MTAG-adjusted summary statistics are then fed to LDpred2-auto in the second step. This method is labelled “MTAG+LDpred2” in the results.

-

5

wMT-SBLUP. This is a method that uses SBLUP to convert univariate OLS summary statistics into univariate Best Linear Unbiased Predictor (BLUP) estimates in the first step. In the second step, the univariate BLUP estimates for multiple phenotypes are adjusted based on weights that take into account the genetic correlations among phenotypes and the sample size from which the summary statistics were computed [34]. This method is labelled “wMT-SBLUP” in the results.

Each method was fitted for each chromosome separately using summary statistics calculated using only the training set individuals. The summary statistics (i.e., effect sizes and standard errors) were computed from univariate simple linear regression of each phenotype on each genetic variant, one at a time. Each phenotype was quantile normalized before the analysis. LD between each pair of variants was computed using 146,288 nominally unrelated White British individuals that did not overlap with the 105,000 individuals used for the rest of the analyses. Correlations between variants that were more than 3 cM apart were set to 0 to create a “banded” LD matrix [10]. We fitted mr.mash-rss including both “canonical” and “data-driven” covariance matrices (see S1 Text and [20] for details).

Results

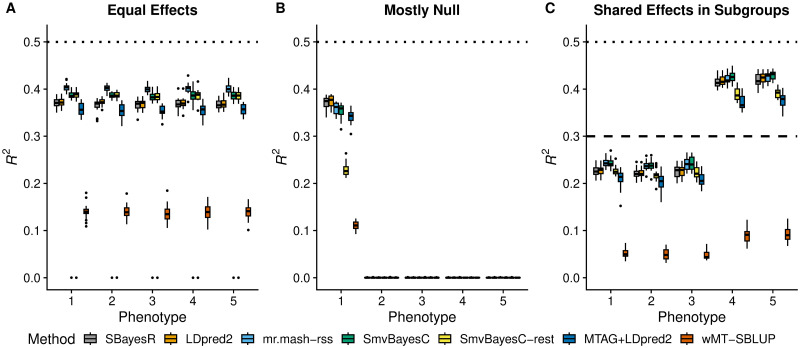

In the Equal Effects scenario (Fig 1A), the three fully multivariate methods (i.e., mr.mash-rss, and the two versions of SmvBayesC) performed better than the two univariate methods. This is expected because the univariate methods assume independence among genetic effects across phenotypes and are unable to learn the pattern of equal genetic effects. Among the multivariate methods, mr.mash-rss produced higher accuracy than SmvBayesC. The “restrictive” version of SmvBayesC performed as well as the unrestricted one because this scenario meets one of the effect combinations allowed by this less flexible method. The two 2-step approaches (i.e., MTAG+LDpred2-auto and wMT-SBLUP) did not perform as well as the other methods. In particular, wMT-SBLUP performed substantially worse than the other methods. We attribute the poor performance to the infinitesimal architecture assumption that wMT-SBLUP makes that does not match our simulation scenarios.

Fig 1. Prediction accuracy in simulations with different patterns of effect sharing across phenotypes.

Each panel summarizes the accuracy of the test set predictions in 20 simulations. The thick, black line in each box gives the median R2. The dotted and dashed lines give the maximum accuracy achievable, i.e., the simulated .

In the Mostly Null scenario (Fig 1B), the genetic effects are present only in the first phenotype. Thus, joint modeling of all the phenotypes is not expected to produce any increase in accuracy compared to a phenotype-by-phenotype analysis. In phenotype 1, while SBayesR and LDpred2-auto were the most accurate methods, mr.mash-rss only had slightly lower mean R2. As for SmvBayesC, the full version performed only slightly worse than mr.mash-rss; however, the “restrictive” version performed much worse. This observation is expected, given that the prior of SmvBayesC “restrictive” only allows for the effects to be present in all or none of the phenotypes. MTAG+LDpred2-auto did a little worse than the other multivariate methods, while wMT-SBLUP performed the worst.

In the Shared Effects in Subgroups scenario (Fig 1C), SBayesR, LDpred2-auto, SmvBayesC, and mr.mash-rss performed very similarly in phenotypes 4 and 5, with SmvBayesC having slightly higher accuracy than the other methods. On the other hand, SmvBayesC and mr.mash-rss outperformed the univariate methods in phenotypes 1–3. This can be explained by the slightly higher sharing of effects across phenotypes, the larger number of phenotypes with shared effects, and the lower , which make the advantage of a multivariate analysis more clear than in phenotypes 4 and 5. The prior of SmvBayesC “restrictive” is not well-suited for this scenario, which resulted in this method not performing well across phenotypes. Similarly, MTAG’s assumption that all genetic variants have the same effect sharing patterns across traits is clearly violated in this scenario. This resulted in MTAG+LDpred2-auto not performing as well as the other methods, with the exception of wMT-SBLUP, which again performed poorly.

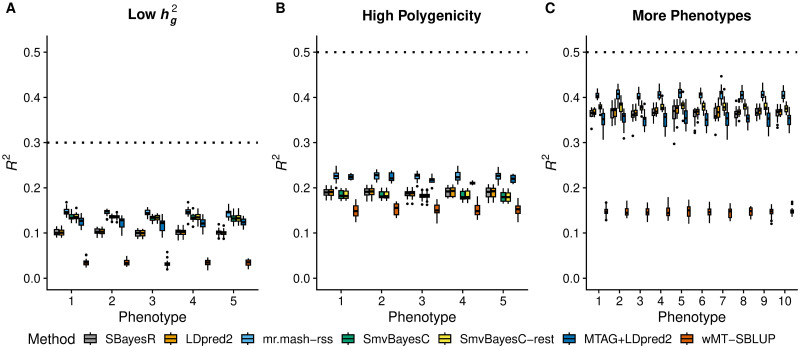

In the Low scenario (Fig 2A), the three fully multivariate methods performed better than the two univariate methods. In addition, the relative improvement provided by the multivariate methods was larger than in the Equal Effects scenario with (Fig 1A). With smaller signal-to-noise ratio, it is harder to estimate effects accurately. Multivariate methods can borrow information across phenotypes and improve accuracy. In this scenario, MTAG+LDpred2-auto also showed better performance than the univariate methods. mr.mash-rss was the best performing method, while wMT-SBLUP was the worst in this scenario.

Fig 2. Prediction accuracy in simulations with different genetic architecture.

Each panel summarizes the accuracy of the test set predictions in 20 simulations. The thick, black line in each box gives the median R2. The dotted lines give the maximum accuracy achievable, i.e., the simulated .

In the High Polygenicity scenario (Fig 2B), prediction accuracy achieved by all the methods was much lower than in the Equal Effects scenario with 5,000 causal variants (Fig 1A). This is expected since each causal variant explains a much smaller proportion of phenotypic variance and, consequently, the effects are harder to estimate accurately. However, mr.mash-rss substantially outperformed both univariate and fully multivariate competing methods. SmvBayesC could not adapt well to this scenario, providing accuracies that are similar to or even lower than SBayesR and LDpred2-auto. MTAG+LDpred2-auto was very competitive with mr.mash-rss, essentially matching its performance for almost all phenotypes, while wMT-SBLUP was the worst in this scenario.

In the More Phenotypes scenario (Fig 2C), the results are very similar to the Equal Effects scenario with 5 phenotypes (Fig 1A). The relative improvement in accuracy provided by mr.mash-rss was, however, a little larger in this scenario because the method can borrow information across more phenotypes with equal effects. On the other hand, SmvBayesC “restrictive” did not benefit from the larger number of phenotypes and provided a relative improvement over the univariate methods that was similar to that of the Equal Effects scenario with 5 phenotypes. We could not run the full version of SmvBayesC in this scenario because it was too computationally intensive.

We note that LDpred2-auto had convergence issues when using MTAG-adjusted summary statistics, presumably due to it being designed to use OLS summary statistics. Thus, some trait-scenario combinations are based on fewer than 20 replicates for MTAG+LDpred2-auto.

To evaluate runtime, we selected chromosome 10 as a medium size chromosome and LDpred2-auto, SmvBayesC, and mr.mash-rss as the best performing methods in Shared Effects in Subgroups, i.e., the most complex scenario in our simulations. The results confirm that mr.mash-rss is computationally efficient compared to the other multivariate method (S1 Table).

Robustness to model misspecification

When analyzing real data, it is common to use LD matrices that are computed using a reference panel, rather than the individuals from whom the summary statistics were computed. It is well-known that issues with analyses with summary statistics arise when the reference panel and the GWAS population do not match [27, 35, 36]. Thus, it is important to assess the robustness of mr.mash-rss to the choice of the LD matrix. While we note that all the simulations above used an LD matrix that was computed using a subset of UK Biobank individuals that did not overlap with those used to compute the summary statistics, we also tested the performance of mr.mash-rss with truly external LD matrices. To do so, we used the same setting as the Equal Effects scenario, but computed LD matrices using 503 unrelated European individuals from the 1000G project [37]. This is a very small sample size that has been shown to be problematic when analyzing large GWAS samples [35]. Some preliminary testing highlighted that “banded” LD matrices (as used for the other simulations) resulted in convergence issues for the methods, while “block-diagonal” LD matrices computed as in [38] produced a better performance. Thus, we used the latter for the “External LD” simulation scenario. The results of this analysis are summarized in S1 Fig and show that, as expected, all the methods performed worse compared to the Equal Effects scenario. However, mr.mash-rss remained the best performing method overall.

mr.mash-rss assumes complete sample overlap across phenotypes. However, this might not be the case when analyzing real data. To investigate the robustness of mr.mash-rss to the violation of this assumption, we used the same setting as the Equal Effects scenario and assigned missing values completely at random (MCAR) to individuals in the training set. This was done such that each individual had missing values in any combination of the five phenotypes with equal probability. We simulated two scenarios, one where 20% of the individuals had missing phenotypes and another one where 80% of the individuals had missing phenotypes. The results, summarized in S2 Fig, show that mr.mash-rss' performance was unchanged in the scenario with fewer missing phenotypes. In the scenario with a larger percentage of missing phenotypes, mr.mash-rss’ prediction accuracy was now lower than SmvBayesC, but still higher than the univariate methods and similar to MTAG+LDpred2-auto.

In summary, these analyses show that mr.mash-rss is fairly robust to some model misspecifications.

Applications

Case study: Predicting blood cell traits in the UK Biobank

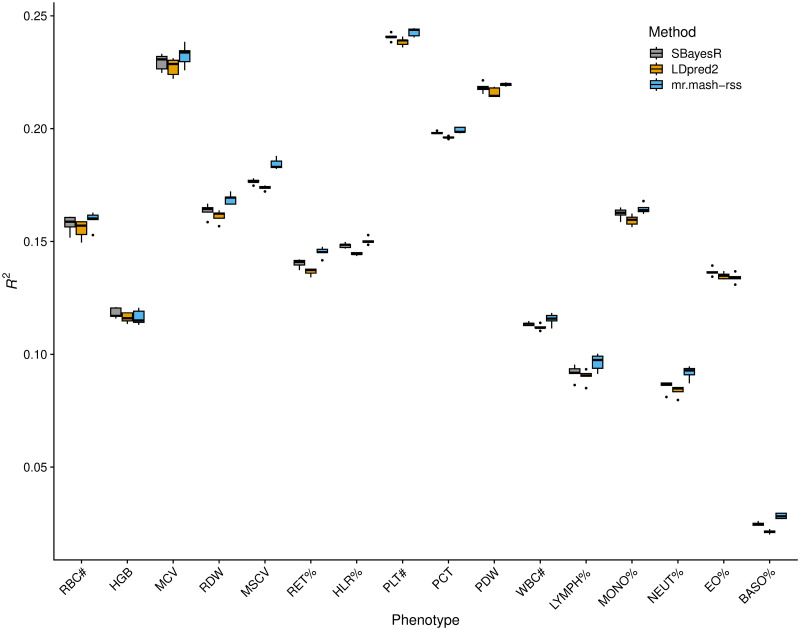

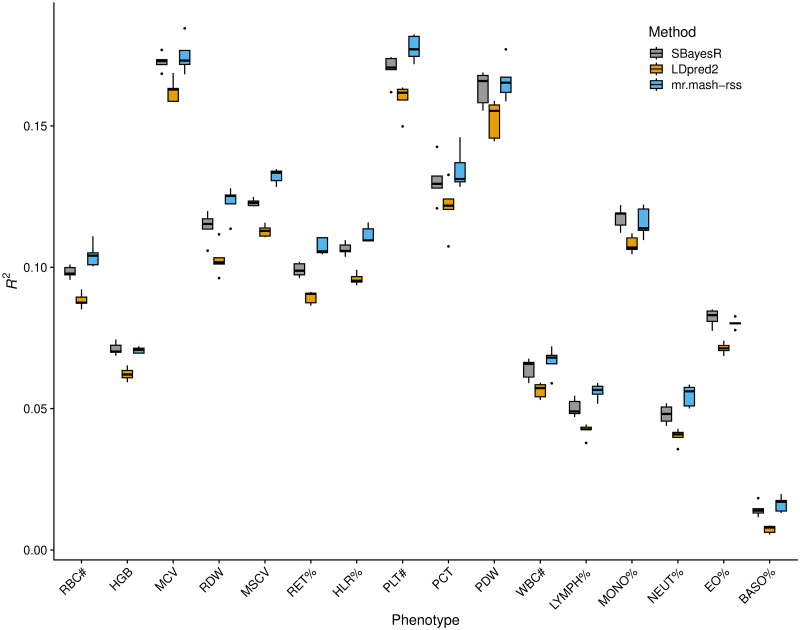

To evaluate mr.mash-rss on a real data application, we sought to predict blood cell traits from genotypes using the UK Biobank data. The UK Biobank is a dataset of roughly 500,000 individuals with genetic and phenotypic data [39]. We focused on a subset of 16 blood cell traits that have been used for quantitative genetic analyses in previous work [24]. After a series of filters (see S1 Text for details), our data consisted of n = 244,049 individuals and p = 1,054,330 HapMap3 variants, as has been previously recommended [40]. The 244K individuals were split into 5 non-overlapping groups to perform 5-fold cross-validation. Each method was trained on the data from 4 groups and prediction accuracy was computed in the remaining fifth group. This procedure was repeated five times, once for each fold. Given that SmvBayesC is too computationally intensive for this many phenotypes, LDpred2-auto suffered from convergence issues when using MATG-adjusted summary statistics, and wMT-SBLUP performed poorly in all simulation scenarios and does not account for sample overlap, we compared mr.mash-rss, LDpred2-auto, and SBayesR in the real data application.

The results of this analysis are summarized in Fig 3 and S2 Table. Overall, the three methods performed similarly. This result is similar to what we found in the “Shared Effects in Subgroup” simulation scenario, which was designed to be reflective of the complex genetic architecture and effect sharing patterns of actual complex traits. However, mr.mash-rss was the most accurate for 14 out 16 blood cell phenotypes. The relative change in mean prediction accuracy compared to LDpred2-auto ranged from -0.6% (Eosinophil Percentage) to 32.8% (Basophill Percentage), with an average of 5.4% (Table 1). The relative change in mean prediction accuracy compared to SBayesR ranged from -1.9% (Eosinophil Percentage) to 13.9% (Basophill Percentage), with an average of 2.7%(Table 1). The better performance of SBayesR compared to LDpred2-auto may be due to a more flexible prior that can better approximate the actual distribution of the genetic effects.

Fig 3. Prediction accuracy for the 16 blood cell traits in the full UK Biobank data.

The thick, black line in each box gives the median R2.

Table 1. Percentage change in mean R2 of mr.mash-rss relative to LDpred2-auto and SBayesR for the 16 blood cell traits in the full and sampled UK Biobank data.

| Phenotype | Full data | Sampled data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDpred2-auto | SBayesR | LDpred2-auto | SBayesR | |

| Red Blood Cell Counts (RBC#) | 2.6 | 1.1 | 18.1 | 6.1 |

| Haemoglobin Concentration (HGB) | 0.1 | -1.6 | 13.5 | -0.7 |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) | 2.3 | 1.3 | 7.7 | 1.3 |

| Red Blood Cell Volume Distribution Width (RDW) | 4.8 | 3.3 | 19.6 | 7.5 |

| Mean Sphered Cell Volume (MSCV) | 6.1 | 4.4 | 17.2 | 7.6 |

| Reticulocyte Percentage (RET%) | 6.3 | 3.5 | 20.1 | 8.3 |

| High Light Scatter Reticulocytes Percentage (HLR%) | 4.0 | 1.4 | 16.3 | 4.7 |

| Platelet Count (PLT#) | 1.8 | 0.9 | 11.3 | 4.3 |

| Plateletcrit (PCT) | 1.6 | 0.6 | 10.9 | 3.0 |

| Platelet Distribution Width (PDW) | 1.7 | 0.7 | 9.0 | 1.7 |

| White Blood Cell Count (WBC#) | 3.2 | 1.8 | 18.3 | 4.3 |

| Lymphocyte Percentage (LYMPH%) | 6.9 | 5.1 | 32.9 | 11.5 |

| Monocyte Percentage (MONO%) | 3.2 | 1.3 | 7.2 | -1.4 |

| Neutrophil Percentage (NEUT%) | 9.7 | 7.1 | 36.0 | 13.8 |

| Eosinophil Percentage (EO%) | -0.6 | -1.9 | 12.4 | -2.4 |

| Basophil Percentage (BASO%) | 32.8 | 13.9 | 122.3 | 13.5 |

Underlined are the negative values, i.e., those instances where mr.mash-rss produces lower accuracy than the competing method.

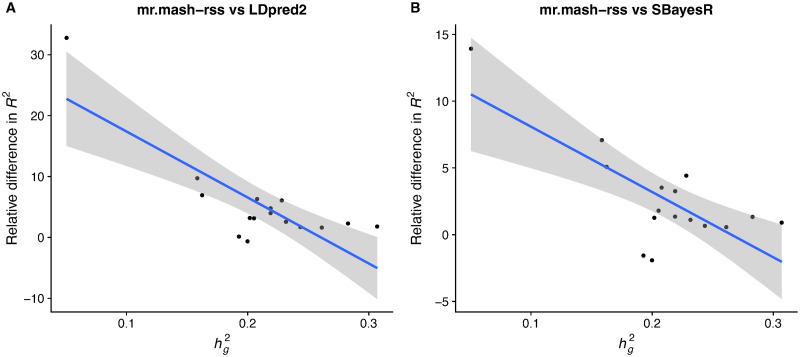

In accordance with the simulations, the improvement in accuracy tended to be largest for phenotypes with lower genomic heritability (though this relationship is only suggestive) as shown in Fig 4. With lower signal-to-noise ratio, leveraging the sharing of effects in a multivariate analysis can give greater improvements. This can be seen, for example, for Neutrophil Percentage (; S3 Table), which has been shown to share putative causal variants with Lymphocyte Percentage (Fig. 3C in [24]) and is one of the phenotypes showing a greater improvement from using mr.mash-rss. On the other hand, the three platelet phenotypes have higher genomic heritability (; S3 Table) and despite some sharing of causal variants (Fig. 3C in [24]), the improvements in accuracy from using mr.mash-rss are very small.

Fig 4. Relationship between improvement in prediction accuracy and genomic heritability in the full UK Biobank data.

Phenotypes are plotted along the x-axis by their genomic heritability () and along the y-axis by the change in R2 relative to the LDpred2-auto (Panel A) and SBayesR (Panel B); that is, (R2(mr.mash-rss)—R2(other method))/R2(other method). The blue line represents the linear regression fit with 95% confidence bands.

Previous analyses have shown that phenotypes with smaller sample size gain more advantage from multivariate modeling [20, 41]. We hypothesized that more substantial improvements in prediction accuracy from using mr.mash-rss could be obtained with a smaller sample size. Thus, we repeated the same analysis on 75,000 individuals, randomly sampled from the total of 244,049. The results, summarized in Fig 5 and S2 Table, showed that this is indeed the case.

Fig 5. Prediction accuracy for the 16 blood cell traits in the sampled UK Biobank data.

The thick, black line in each box gives the median R2.

In fact, the relative change in mean prediction accuracy compared to LDpred2-auto ranged from 7.2% (Monocyte Percentage) to 122.3% (Basophill Percentage), with an average of 23.3% (Table 1). This is about 4 times larger than the average relative change in mean prediction accuracy using the full data. The relative change in mean prediction accuracy compared to SBayesR ranged from -2.4% (Eosinophil Percentage) to 13.5% (Neutrophil Percentage), with an average of 5.2% (Table 1). This is about 2 times larger than the average relative change in mean prediction accuracy using the full data.

Case study: Predicting more polygenic traits in the UK Biobank

We then sought to predict eight more polygenic phenotypes. Based on [42], we chose a group of phenotypes that have high pairwise genetic correlations; namely, body mass index (BMI), trunk fat mass (TFM), body fat percentage (BFP), weight, waist circumference, hip circumference. We also chose two additional phenotypes, namely diastolic blood pressure (DP) and systolic blood pressure (SP), that are highly genetically correlated with each other and are moderately genetically correlated with the phenotypes in the first group. This was meant as a stress test of our methods, given that previous studies have shown that this type of variational empirical Bayes methods are usually less competitive with dense signals [12, 43].

The results of this analysis are summarized in S3 Fig and show that, as expected, mr.mash-rss was outperformed by the other methods for all the phenotypes in this case study. Previous studies have found the source of the under performance to be the M-step update for the prior mixture weights [12]. Here, anecdotally, we also observed the same phenomenon, whereby the weights on the null component and on the components with very small variance in the mixture tended to be over estimated, resulting in over shrinkage of the effects. [12] solved the issue by using a grid search and cross-validation approach to select the combination of mixture weights that maximizes prediction accuracy in a test set. However, this strategy is not feasible for mr.mash-rss wherein the number of mixture components is often more than 100.

Thus, we used a different strategy to try and improve mr.mash-rss’ performance. In particular, we ran mash with the same mixture prior as mr.mash-rss, on the summary statistics for a subset of semi-independent LD-pruned genetic variants for all chromosomes. We extracted the estimated mixture weights, set the weight on the null component to 0.5, and rescaled the other mixture weights accordingly (this step was necessary because mash underestimated the null weight due to it being run on a small sample of genetic variants). These mixture weights were fed to mr.mash-rss, which was then constrained to update the mixture weights for only the first 10 iterations. In this way, we maintained the adaptive nature of the empirical Bayes without incurring over shrinkage of the effects.

The results show that using this strategy (termed “mr.mash-rss mash” in the S3 Fig), the performance of mr.mash-rss improves for every phenotype, becoming comparable to the other methods’ for DP, SP, hip, and weight, and superior for BMI.

Discussion

In this work, we have introduced mr.mash-rss, the summary data version of a recently developed empirical Bayes multivariate multiple regression method [20]. Like mr.mash, mr.mash-rss enjoys (1) the ability to learn patterns of effect sharing across phenotypes; (2) the ability to model dozens of phenotypes jointly; (3) computational efficiency. Additionally, mr.mash-rss addresses two important limitations of mr.mash —the need for individual-level data and the lack of scalability to biobank-size data.

Through an array of simulations and real data analysis using the UK Biobank, we showed that mr.mash-rss is competitive with state-of-the-art univariate and multivariate PGS methods. Of note, mr.mash-rss outperformed competing methods in 14 out of 16 blood cell phenotypes, although the magnitude of the improvement varied across phenotypes, from modest to substantial. This highlights that the general mr.mash model can adapt to either more sparse (e.g., for gene expression [20]) or more dense (e.g., for complex traits) genetic architectures. We also showed that the improvement in prediction accuracy from using mr.mash-rss increased substantially with a smaller sample size. This holds good promise for improving prediction accuracy for phenotypes that are difficult to measure and in samples of individuals of non-European descent, which are usually much smaller [44]. In addition, the performance of the mr.mash model depends on the accuracy of the “data-driven” covariance matrices [20]. Thus, advances in covariance matrix estimation can potentially lead to improvements in prediction accuracy.

A limitation of mr.mash-rss is that it does not perform as well for very polygenic phenotypes as highlighted by the second data application. This is a known issue for this type of variational empirical Bayes methods [12, 43]. The problem stems from the update of the hyperparameters (the mixture weights, in particular) by maximization of the ELBO, which gets trapped in sub-optimal local optima [12, 45]. This issue can be overcome by using a grid search and cross-validation approach to select the combination of mixture weights that maximizes prediction accuracy in a test set [11, 12]. However, mr.mash-rss usually includes a large number of mixture components, which makes the grid search and cross-validation approach not feasible. We were able to ameliorate this problem by obtaining good initial estimates of the mixture weights with mash, which were then refined with a few iterations of mr.mash-rss. This simple strategy improved the prediction accuracy of mr.mash-rss, making it competitive for most traits analyzed. Future research is needed to find a more principled way to select hyperparameters that works well with arbitrary patterns of sparsity in the genetic architecture of complex traits.

Another limitation of mr.mash-rss is that it requires the summary statistics to be computed on the same samples for each phenotype. In other words, there should not be missing data in Y in 1. Dealing with arbitrary patterns of missing data in multivariate models is not a trivial problem [46] and is an area where more research is needed. If individual-level data are available, missing values may be imputed before the prediction analysis. In fact, recent work has shown that imputing missing values results in improved prediction accuracy of PGS and power in GWAS [47, 48]. Nonetheless, our results showed that mr.mash-rss is robust to a small to medium amount of missing phenotypes. In addition, in specific cases such as with complete sample non-overlap across phenotypes, some simplifications arise that allow for models like mr.mash-rss to be fitted efficiently [38].

Our work showed that mr.mash-rss is fairly robust to some forms of model misspecification (i.e., external LD and sample non-overlap). However, model misspecification also arises with the use of “imperfect” summary statistics. For example, when summary statistics come from a meta-analysis of multiple cohorts, sample size is often different among genetic variants, and different biases and noise levels likely affect different cohorts [40]. One way to test the robustness of mr.mash-rss to different sources of model misspecification would be to use truly external summary statistics, possibly from a meta-analysis, and evaluate its performance in an independent cohort.

This work evaluated mr.mash-rss using continuous phenotypes. While the theory behind the method assumes the phenotypes to be continuous, it may be possible for mr.mash-rss to be applied to case-control phenotypes, in the same way as methods such LDpred2-auto and SBayesR, which also assume continuous phenotypes. An in-depth investigation of the performance of mr.mash-rss for case-control phenotypes is left for future work.

Supporting information

For LDpred2-auto, the statistics are based on the sum of runtime across phenotypes. Each method was run using 4 CPUs.

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

The figure summarizes the accuracy of the test set predictions in 20 simulations of the Equal Effects scenario. The thick, black line in each box gives the median R2. The dotted line gives the maximum accuracy achievable, i.e., the simulated .

(EPS)

Each panel summarizes the accuracy of the test set predictions in 20 simulations of the Equal Effects scenario. Panel A (B) includes the results of a scenario where 20% (80%) of the individuals have missing values in any combination of the 5 phenotypes. The thick, black line in each box gives the median R2. The dotted line gives the maximum accuracy achievable, i.e., the simulated .

(EPS)

The thick, black line in each box gives the median R2.

(EPS)

Detailed description of the methods, including: derivations of the mr.mash-rss algorithms; data preparation; simulations; methods compared; data analysis.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under application number 129216. We thank Gao Wang, Yuxin Zou, Peter Carbonetto, and Matthew Stephens for useful discussions.

Data Availability

The genotype and phenotype data used in our analyses are available from UK Biobank (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). All code implementing the simulations and data analyses, and the compiled results generated from our simulations have been deposited on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14262333). The methods are implemented in the R package mr.mash.alpha, available for download at https://github.com/stephenslab/mr.mash.alpha.

Funding Statement

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R35GM146868 to FM. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. PS acknowledges support from Open Discovery Innovation Network (ODIN) under grant number NNF20SA0061466. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Hickey JM, Chiurugwi T, Mackay I, Powell W. Genomic prediction unifies animal and plant breeding programs to form platforms for biological discovery. Nature genetics. 2017;49(9):1297–1303. doi: 10.1038/ng.3920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lewis CM, Vassos E. Polygenic risk scores: from research tools to clinical instruments. Genome medicine. 2020;12(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13073-020-00742-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wainberg M, Sinnott-Armstrong N, Mancuso N, Barbeira AN, Knowles DA, Golan D, et al. Opportunities and challenges for transcriptome-wide association studies. Nature genetics. 2019;51(4):592–599. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0385-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walsh B, Lynch M. Evolution and selection of quantitative traits. Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cao C, Ding B, Li Q, Kwok D, Wu J, Long Q. Power analysis of transcriptome-wide association study: Implications for practical protocol choice. PLoS genetics. 2021;17(2):e1009405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meuwissen TH, Hayes BJ, Goddard M. Prediction of total genetic value using genome-wide dense marker maps. genetics. 2001;157(4):1819–1829. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.4.1819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Los Campos G, Hickey JM, Pong-Wong R, Daetwyler HD, Calus MP. Whole-genome regression and prediction methods applied to plant and animal breeding. Genetics. 2013;193(2):327–345. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.143313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ge T, Chen CY, Ni Y, Feng YCA, Smoller JW. Polygenic prediction via Bayesian regression and continuous shrinkage priors. Nature communications. 2019;10(1):1776. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09718-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lloyd-Jones LR, Zeng J, Sidorenko J, Yengo L, Moser G, Kemper KE, et al. Improved polygenic prediction by Bayesian multiple regression on summary statistics. Nature communications. 2019;10(1):5086. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12653-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Privé F, Arbel J, Vilhjálmsson BJ. LDpred2: better, faster, stronger. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(22-23):5424–5431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Q, Privé F, Vilhjálmsson B, Speed D. Improved genetic prediction of complex traits from individual-level data or summary statistics. Nature communications. 2021;12(1):4192. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24485-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zabad S, Gravel S, Li Y. Fast and accurate Bayesian polygenic risk modeling with variational inference. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2023;110(5):741–761. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma Y, Zhou X. Genetic prediction of complex traits with polygenic scores: a statistical review. Trends in Genetics. 2021;37(11):995–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2021.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jia Y, Jannink JL. Multiple-trait genomic selection methods increase genetic value prediction accuracy. Genetics. 2012;192(4):1513–1522. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.144246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grinberg NF, Wallace C. Multi-tissue transcriptome-wide association studies. Genetic Epidemiology. 2021;45(3):324–337. doi: 10.1002/gepi.22374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rohde PD, Nyegaard M, Kjolby M, Sørensen P. Multi-trait genomic risk stratification for type 2 diabetes. Frontiers in Medicine. 2021;8:711208. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.711208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xu C, Ganesh SK, Zhou X. mtPGS: Leverage multiple correlated traits for accurate polygenic score construction. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2023;110(10):1673–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Albiñana C, Zhu Z, Schork AJ, Ingason A, Aschard H, Brikell I, et al. Multi-PGS enhances polygenic prediction by combining 937 polygenic scores. Nature communications. 2023;14(1):4702. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-40330-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Truong B, Hull LE, Ruan Y, Huang QQ, Hornsby W, Martin H, et al. Integrative polygenic risk score improves the prediction accuracy of complex traits and diseases. Cell Genomics. 2024;4(4). doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2024.100523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morgante F, Carbonetto P, Wang G, Zou Y, Sarkar A, Stephens M. A flexible empirical Bayes approach to multivariate multiple regression, and its improved accuracy in predicting multi-tissue gene expression from genotypes. PLoS Genetics. 2023;19(7):e1010539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1010539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pasaniuc B, Price AL. Dissecting the genetics of complex traits using summary association statistics. Nature reviews genetics. 2017;18(2):117–127. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Urbut SM, Wang G, Carbonetto P, Stephens M. Flexible statistical methods for estimating and testing effects in genomic studies with multiple conditions. Nature genetics. 2019;51(1):187–195. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0268-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vuckovic D, Bao EL, Akbari P, Lareau CA, Mousas A, Jiang T, et al. The polygenic and monogenic basis of blood traits and diseases. Cell. 2020;182(5):1214–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zou Y, Carbonetto P, Xie D, Wang G, Stephens M. Fast and flexible joint fine-mapping of multiple traits via the Sum of Single Effects model. bioRxiv. 2023; p. 2023–04. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blei DM, Kucukelbir A, McAuliffe JD. Variational inference: A review for statisticians. Journal of the American statistical Association. 2017;112(518):859–877. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2017.1285773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blei DM, Ng AY, Jordan MI. Latent dirichlet allocation. Journal of machine Learning research. 2003;3(Jan):993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zou Y, Carbonetto P, Wang G, Stephens M. Fine-mapping from summary data with the “Sum of Single Effects” model. PLoS Genetics. 2022;18(7):e1010299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1010299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen W, Wu Y, Zheng Z, Qi T, Visscher PM, Zhu Z, et al. Improved analyses of GWAS summary statistics by reducing data heterogeneity and errors. Nature Communications. 2021;12(1):7117. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27438-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; 2023. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

- 30. Wray NR, Yang J, Hayes BJ, Price AL, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. Pitfalls of predicting complex traits from SNPs. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2013;14(7):507–515. doi: 10.1038/nrg3457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheng H, Kizilkaya K, Zeng J, Garrick D, Fernando R. Genomic prediction from multiple-trait Bayesian regression methods using mixture priors. Genetics. 2018;209(1):89–103. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.300650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rohde PD, Fourie Sørensen I, Sørensen P. Expanded utility of the R package, qgg, with applications within genomic medicine. Bioinformatics. 2023;39(11):btad656. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btad656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Turley P, Walters RK, Maghzian O, Okbay A, Lee JJ, Fontana MA, et al. Multi-trait analysis of genome-wide association summary statistics using MTAG. Nature genetics. 2018;50(2):229–237. doi: 10.1038/s41588-017-0009-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maier RM, Zhu Z, Lee SH, Trzaskowski M, Ruderfer DM, Stahl EA, et al. Improving genetic prediction by leveraging genetic correlations among human diseases and traits. Nature communications. 2018;9(1):989. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02769-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Benner C, Havulinna AS, Järvelin MR, Salomaa V, Ripatti S, Pirinen M. Prospects of fine-mapping trait-associated genomic regions by using summary statistics from genome-wide association studies. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2017;101(4):539–551. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dun Y, Chatterjee N, Jin J, Nishimura A. A Robust Bayesian Method for Building Polygenic Risk Scores using Projected Summary Statistics and Bridge Prior. arXiv preprint arXiv:240115014. 2024;.

- 37. Consortium GP, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68. doi: 10.1038/nature15393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Spence JP, Sinnott-Armstrong N, Assimes TL, Pritchard JK. A flexible modeling and inference framework for estimating variant effect sizes from GWAS summary statistics. BioRxiv. 2022; p. 2022–04. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562(7726):203–209. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Privé F, Arbel J, Aschard H, Vilhjálmsson BJ. Identifying and correcting for misspecifications in GWAS summary statistics and polygenic scores. Human Genetics and Genomics Advances. 2022;3(4). doi: 10.1016/j.xhgg.2022.100136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hu Y, Li M, Lu Q, Weng H, Wang J, Zekavat SM, et al. A statistical framework for cross-tissue transcriptome-wide association analysis. Nature genetics. 2019;51(3):568–576. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0345-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu Y, Burch KS, Ganna A, Pajukanta P, Pasaniuc B, Sankararaman S. Fast estimation of genetic correlation for biobank-scale data. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2022;109(1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim Y, Wang W, Carbonetto P, Stephens M. A flexible empirical Bayes approach to multiple linear regression and connections with penalized regression. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2024;25(185):1–59. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Martin AR, Kanai M, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Neale BM, Daly MJ. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nature genetics. 2019;51(4):584–591. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0379-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ročková V, George EI. EMVS: The EM approach to Bayesian variable selection. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2014;109(506):828–846. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2013.869223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. vol. 793. John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dahl A, Thompson M, An U, Krebs M, Appadurai V, Border R, et al. Phenotype integration improves power and preserves specificity in biobank-based genetic studies of major depressive disorder. Nature Genetics. 2023;55(12):2082–2093. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01559-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. An U, Pazokitoroudi A, Alvarez M, Huang L, Bacanu S, Schork AJ, et al. Deep learning-based phenotype imputation on population-scale biobank data increases genetic discoveries. Nature Genetics. 2023;55(12):2269–2276. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01558-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]