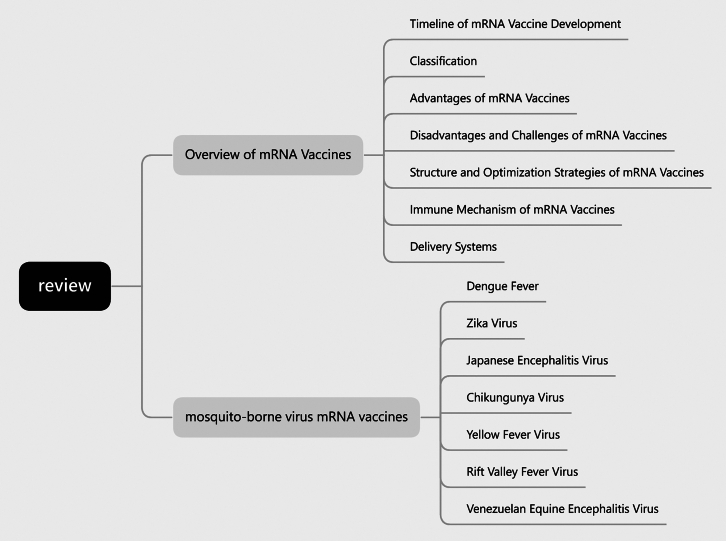

Abstract

In recent years, mRNA vaccines have emerged as a leading technology for preventing infectious diseases due to their rapid development and high immunogenicity. These vaccines encode viral antigens, which are translated into antigenic proteins within host cells, inducing both humoral and cellular immune responses. This review systematically examines the progress in mRNA vaccine research for major mosquito-borne viruses, including dengue virus, Zika virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, Chikungunya virus, yellow fever virus, Rift Valley fever virus, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. Enhancements in mRNA vaccine design, such as improvements to the 5′ cap structure, 5′UTR, open reading frame, 3′UTR, and polyadenylation tail, have significantly increased mRNA stability and translation efficiency. Additionally, the use of lipid nanoparticles and polymer nanoparticles has greatly improved the delivery efficiency of mRNA vaccines. Currently, mRNA vaccines against mosquito-borne viruses are under development and clinical trials, showing promising protective effects. Future research should continue to optimize vaccine design and delivery systems to achieve broad-spectrum and long-lasting protection against various mosquito-borne virus infections.

Keywords: mosquito-borne virus, mRNA vaccine, dengue virus, Zika virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, Chikungunya virus, yellow fever virus, Rift Valley fever virus, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus

Graphical abstract

Zheng, Sun, and Su review mRNA vaccines for mosquito-borne viruses, highlighting improved design and delivery systems that enhance stability and protection against diseases like dengue and Zika.

Introduction

The development and application of vaccines have saved thousands of lives and reduced healthcare costs significantly. For instance, the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, particularly its impact on measles prevention, has helped avert approximately 31.7 million deaths globally between 2000 and 2020.1,2 Traditional vaccines have, over the past several decades, successfully controlled and even eradicated many severe infectious diseases. For example, the measles vaccine, introduced in the 1960s, reduced measles incidence by more than 99% in the United States and dramatically lowered measles outbreaks globally.3 The polio vaccine, introduced in the 1950s, has nearly eradicated most poliomyelitis cases worldwide, with an efficacy of 99%, playing a key role in global polio eradication efforts.4 Similarly, since the introduction of the diphtheria vaccine in the 1950s, the incidence of diphtheria has decreased by more than 90%, with its efficacy thoroughly validated.5 Traditional vaccines have been highly successful in controlling and eliminating many serious infectious diseases by using inactivated or attenuated pathogens (viruses or bacteria) to induce an immune response. These vaccines are widely used to prevent diseases such as measles, influenza, and diphtheria.6 The MMR vaccine, for example, has shown an efficacy of 97% against measles, 88% against mumps, and 97% against rubella after two doses.7 The preparation of traditional vaccines involves culturing pathogens, reducing their pathogenicity through inactivation or attenuation, and then injecting these treated pathogens or their components into the human body to stimulate an immune response.8 Despite their effectiveness, traditional vaccines often require long development and production times and may pose safety and stability issues.9 For example, while traditional vaccines like MMR and polio vaccines have eradicated or controlled many diseases, they typically require cold chain storage, which limits their global distribution, especially in low-resource settings.

With advancements in biotechnology, new types of vaccines, such as DNA vaccines, mRNA vaccines, and vector virus vaccines, have emerged. These new vaccines use advanced biotechnology platforms and introduce genetic information from pathogens to induce both antibody and cellular immune responses. Compared with traditional vaccines, new vaccines are developed and produced more rapidly and flexibly, often with better safety profiles.10 For instance, during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, mRNA vaccines like those developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna demonstrated efficacy rates exceeding 90% in clinical trials,11 contrasting with the traditional vaccine development timeline, which often takes 5–10 years. Recently, mRNA vaccines have gained significant attention due to advancements in structural modification and delivery vector optimization, particularly highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

mRNA vaccines offer several advantages over traditional vaccines, especially in responding to infectious disease outbreaks due to their rapid development timelines. These vaccines simplify the production process by directly synthesizing mRNA, which human cells then use to produce antigens, bypassing the need for complex viral protein culture and synthesis.12 The raw materials and reagents for mRNA vaccines are obtained through standardized supply chains, enhancing production efficiency and safety.13 Moreover, mRNA vaccines do not require toxic chemicals, and the antigens are synthesized within the body, reducing contamination risks.14 They are easy to produce, have a short production time, are easily modifiable, and efficiently express proteins directly in the cytoplasm.12,15 Studies show that mRNA vaccines, due to their synthetic nature, have better scalability and adaptability in terms of targeting emerging infectious diseases.16 For instance, mRNA vaccines can be rapidly adjusted to address mutations in viruses, which is a key advantage over traditional vaccines, where re-engineering the whole pathogen or protein structure is more time-consuming.

One of the most significant immunological advantages of mRNA vaccines is their ability to activate both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses. Traditional protein-based vaccines, like inactivated or subunit vaccines, typically elicit a CD4+ T cell-mediated humoral response, focusing on antibody production.17 In contrast, mRNA vaccines have the unique capability of inducing CD8+ T cell-mediated cellular immunity, which is crucial for eliminating virus-infected cells.18 CD8+ T cells are important for directly killing infected cells and are essential in long-term viral control, especially for intracellular pathogens like viruses.19 This broader immune response makes mRNA vaccines particularly advantageous for certain populations, such as immunocompromised patients, as they may require stronger cellular immunity to fight infections. Several studies have supported these differences, highlighting that mRNA vaccines can provide more durable and comprehensive immune responses compared with traditional vaccines, which is especially critical for emerging or re-emerging pathogens.12

Mosquito-borne viruses are transmitted to humans or other animals through mosquito bites, infecting the host and replicating to cause diseases ranging from mild fever to severe neurological damage and even death.20 Major mosquito-borne viruses include Dengue virus (DENV), Yellow fever virus (YFV), Zika virus (ZIKV), Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV), and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV).21,22,23,24,25,26,27 These viruses are transmitted by different mosquito species, such as Aedes aegypti and A. albopictus.28 Mosquito-borne diseases impose a significant health burden worldwide. Dengue fever, one of the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viruses worldwide, results in approximately 390 million infections annually and can be fatal in severe cases29; Although YF is less common, it remains significant due to its high fatality rate30; The ZIKV, discovered in Uganda in 1947, triggered a major epidemic in the Americas in 2015, leading to severe consequences such as microcephaly in newborns31; CHIKV, an alphavirus, saw a notable resurgence following an Indian Ocean epidemic originating from Kenya’s coast in 2004, and is known for causing severe arthritis and chronic pain.32 JEV, primarily transmitted by Culex mosquitoes, continues to pose a threat in Southeast Asia, primarily affecting the central nervous system and potentially leading to encephalitis, epilepsy, and death.33 RVFV, highly pathogenic to both humans and livestock, is primarily transmitted by mosquitoes and can lead to severe hemorrhagic fever and hepatitis.34 VEEV, another mosquito-borne pathogen, affects both humans and horses, causing encephalitis with high fatality rates.35 These mosquito-borne viruses pose substantial public health challenges due to their rapid spread and severe health outcomes, underscoring the urgent need for effective preventive measures, including advanced vaccine development. Additionally, several emerging mosquito-borne viruses, such as Mayaro, Oropouche, Ross River, and O’nyong-nyong viruses, are attracting increasing attention due to their potential for widespread transmission. Mayaro virus, primarily transmitted by Haemagogus mosquitoes in South and Central America, can cause symptoms similar to dengue fever and may spread to urban areas through Aedes mosquitoes.36 Oropouche virus, mainly found in Latin America, is transmitted by biting midges and sometimes mosquitoes, and has caused multiple outbreaks in the region.37 Ross River virus, endemic to Australia and the South Pacific, is known for causing prolonged joint pain and arthritis.38 O’nyong-nyong virus, primarily transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes in Africa, has the potential to cause significant outbreaks and long-lasting joint issues.39 As climate change continues to expand the geographical range of mosquito vectors, these viruses could become more prevalent globally, emphasizing the need for continued vaccine development efforts.

Several mosquito-borne virus vaccines are currently in clinical trials or have been approved. The YF vaccine, for instance, has been in use for a long time and is crucial in preventing YFV infection and transmission.40 Dengue vaccines, such as Sanofi’s Dengvaxia and Takeda’s Qdenga, have been approved in some countries, although their effectiveness and safety are continuously evaluated and improved.21 Additionally, the Butantan-DV vaccine has shown promising phase 3 clinical data.41,42,43,44,45 For Japanese encephalitis, JEV vaccines are widely used and effectively prevent the disease.46 RVFV and VEEV vaccines are also under development and clinical trials, showing protective effects.47 With the advent of mRNA technology, researchers are now focusing on developing mRNA-based vaccines for mosquito-borne viruses, which could provide quicker, safer, and more flexible responses to outbreaks.

Researchers continue to develop more effective and safer mosquito-borne virus vaccines to mitigate the health threats these viruses pose. With ongoing scientific and technological advancements, we expect to see more innovative vaccines emerge, providing better means to prevent mosquito-borne virus infections. This article focuses on the progress of mRNA vaccines for mosquito-borne viruses, analyzing their potential and prospects in prevention and control.

Overview of mRNA vaccines

Classification

mRNA can be classified into non-replicating mRNA (nrRNA), virus-derived self-amplifying mRNA (saRNA), trans-amplifying mRNA (taRNA), and circular mRNA (circRNA) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Different types of mRNA vaccines

(A) nrRNA: Composed of a 5′ cap, 5' UTR, ORF, 3′ UTR, and Poly(A) tail. (B) saRNA: Contains two ORFs enabling self-replication, along with a 5' cap, 5′ UTR, 3′UTR, and Poly(A) tail. (C) taRNA: Requires trans-acting factors for amplification, composed of a 5′ cap, 5′UTR, ORF, 3′UTR, and Poly(A) tail. (D) CircRNA: Contains an IRES and ORF, forming a circular structure for translation. IRES, internal ribosome entry site.

nrRNA

nrRNA is a type of linear mRNA synthesized in vitro. It includes a complete gene sequence and can induce an immune response when delivered into the body via a vector. The design of nrRNA features a 5′ cap, 5′UTR, an open reading frame (ORF) encoding the protein antigen, a 3′UTR, and a poly(A) tail. These structural elements are modified to enhance mRNA stability and resistance to degradation, thus extending its half-life in vivo and minimizing unnecessary immune responses.48,49,50

Since nrRNA cannot replicate in vivo, higher doses are typically required to achieve an effective immune response.51,52 Its advantages include a simple structure and validated design, allowing immediate use in vaccine production after in vitro transcription. However, it necessitates a mature optimized process to elicit an effective immune response at lower doses.53

nrRNA vaccines have been used in the prevention and treatment of various diseases. A prominent example is the mRNA vaccines developed for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, which have demonstrated high efficacy and safety in preventing COVID-19. These vaccines use nrRNA to encode the spike protein of the virus, inducing a strong immune response. For instance, in therapeutic vaccine development, nrRNA is used to retrain the specific immune response against HIV-1. These vaccine designs include naked mRNA targeting subdominant and conserved regions of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), and mRNA encoding CD40 and CD70 ligands as adjuvants.54 Additionally, nrRNA vaccines are being explored in cancer immunotherapy by encoding tumor-associated antigens to stimulate the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells. Clinical trials have shown promising results in treating cancers such as melanoma.55 Although some nrRNA vaccines have shown safety and immunogenicity in clinical evaluations, further research and validation are required for others.56,57,58,59

Virus-derived saRNA

saRNA vaccines are based on engineered single-stranded RNA virus genomes, such as alphaviruses, flaviviruses, and small RNA viruses.60 These vaccines retain the replication machinery genes and replace the structural protein regions with the target gene, enabling replication within the host and requiring only a small amount to induce a strong immune response.51 saRNA includes the mRNA sequence encoding the antigen protein and self-amplifying elements, which allow the antigen sequences to self-amplify in vivo. This results in more antigen expression despite potential delays, leading to a small dose, high potency immune response.53

However, saRNA molecules are significantly longer due to the inclusion of viral replicase genes, which can pose challenges in manufacturing and delivery.61 The large size can lead to increased difficulty in encapsulation within delivery vehicles like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and may also trigger stronger innate immune responses, potentially leading to increased reactogenicity. Currently, saRNA vaccines for influenza and COVID-19 have entered clinical research, showing good immunogenicity and protective efficacy (Table 1).65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73 saRNA vaccines can be delivered through various methods, such as DNA plasmid-based saRNA, virus-like particles, and in vitro transcribed (IVT) saRNA, each offering specific advantages to enhance vaccine stability and immune effects.49

Table 1.

saRNA vaccine clinical results

| Vaccine candidate | Target disease | Clinical phase | Immunogenicity | Efficacy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderna mRNA-1083 | influenza and COVID-19 | phase 3 | strong immune responses against both influenza and SARS-CoV-2 strains | non-inferior, with some strains showing higher immune responses than licensed vaccines | 62 |

| ARCT-154 (CSL/Arcturus) | COVID-19 | approved in Japan | high efficacy in stimulating APCs for long-term immunity | >95% efficacy in preventing severe COVID-19 infections | 63 |

| Pfizer-BioNTech Quadrivalent modRNA | influenza | phase 3 | robust immune responses to multiple influenza strains | potential for improved strain match and flexibility for pandemic flu | 64 |

Despite their potential in many animal models, key issues such as optimizing the inflammatory response and overcoming insertion fragment size limitations need to be resolved for saRNA vaccines.65 Overall, saRNA vaccines show significant potential in preventing and treating infectious diseases and cancers, with their value becoming more recognized through ongoing research.

taRNA

taRNA vaccines are a novel type of mRNA vaccine that offer greater safety and broader applicability compared with saRNA. taRNA molecules are shorter in length because they only include the sequences necessary for antigen expression, without the self-replicating machinery present in saRNA, such as the non-structural proteins (nsP1–4).74 These nsPs are responsible for saRNA’s ability to self-replicate, but they also significantly increase the RNA molecule’s size. By excluding these components, taRNA reduces the overall molecular length, which makes it easier to manufacture and deliver the RNA into cells. Producing shorter mRNA is simpler, making taRNA vaccines more cost effective while ensuring high yield and quality.75,76 The reduced length of taRNA not only simplifies the manufacturing process but also reduces the likelihood of triggering excessive innate immune responses, enhancing safety.77 Larger RNA molecules, like those in saRNA, are more likely to be recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in the immune system, potentially leading to stronger inflammatory responses, which may result in adverse effects.78 The taRNA strategy improves upon the limitations of saRNA, providing advantages in safety, manufacturability, and optimization over traditional nrRNA vaccines.49

By splitting the self-amplification components and the antigen-encoding sequences into two separate RNA molecules, taRNA avoids the need to include long viral replication genes in a single RNA strand. This separation not only reduces the molecular size but also minimizes the risk of creating replication-competent RNA viruses, which could raise biosafety concerns. This design reduces the molecular size of each RNA component, facilitating more efficient delivery into cells and lowering the risk of eliciting excessive innate immune responses associated with larger RNA molecules.

The unique feature of taRNA vaccines is the co-delivery of two RNA molecules: one encoding the target antigen without nsP1–4, and the other encoding these nsPs.52 This design ensures efficient antigen expression while reducing the complexity of a single large RNA molecule, simplifying vaccine production and optimization processes. Moreover, this separation strategy enables more flexible optimization of the vaccine design, allowing for adjustments in the self-amplification process or antigen expression without needing to modify the entire RNA sequence. In contrast, saRNA faces several limitations. The inclusion of self-replicating machinery increases the molecular size, complicating the delivery of the RNA into cells.79 The larger the RNA, the more likely it is to trigger unwanted immune responses, which may limit the strength and duration of the antigen-specific immune response. Additionally, saRNA’s complex structure makes it more challenging to manufacture at scale, leading to higher costs and lower yields. Furthermore, the instability of the larger RNA molecules means that they may degrade more rapidly in the body, reducing the effectiveness of the vaccine.

Overall, taRNA vaccines combine safety, manufacturability, and high-efficiency antigen expression, showing significant potential and application prospects in vaccine development. While saRNA may still be useful in contexts where prolonged or more robust immune responses are required, its limitations in safety and production complexity make taRNA a more attractive option for large-scale, rapid vaccine deployment, especially in pandemics where speed and scalability are critical.

circRNA

circRNA is a covalently closed circular molecule with a longer half-life, protecting RNA from degradation.80,81 Endogenous circRNA has been shown to regulate various physiological processes and can be designed as molecules with specific functions.82 IVT circRNA typically employs an intron-splicing strategy to guide target RNA circularization.51 This unique structure and production method provide significant advantages in stability and functionality, offering broad application prospects.

Advantages of mRNA vaccines

Overall, mRNA vaccines offer several advantages over traditional vaccines. First, by eliciting both cellular and humoral immune responses, mRNA vaccines can generate a strong immune response, often without the need for additional adjuvants.83,84 Second, mRNA vaccines are highly specific and precise, capable of encoding multiple antigens to enhance immune responses against adaptive pathogens, and they do not integrate into the genome, which ensures greater safety and controllability.85,86 Additionally, mRNA translation occurs in the cytoplasm, leading to higher translation efficiency. The production efficiency of mRNA using in vitro transcription technology is also high, making mRNA vaccines quick and cost effective to produce.87,88

The development cycle of mRNA vaccines is relatively short and the costs are comparatively low, allowing for the rapid creation of candidate vaccines to respond to viral mutations, which is beneficial for controlling infectious diseases. In terms of production, mRNA vaccines offer a wide range of antigen selection, simple design and synthesis methods, significant flexibility in platform choice, and production based on in vitro cell-free transcription reactions, which reduces safety concerns such as cellular impurities and viral contamination, thereby enhancing production efficiency and safety.

Disadvantages and challenges of mRNA vaccines

mRNA vaccines face several challenges in their development and application. First, mRNA’s structure is similar to that of viruses and bacteria, making it easily recognized by the body’s innate immune system as potential pathogens, leading to strong inflammatory responses, such as fever, which can affect vaccine efficacy. Second, mRNA’s translation efficiency is relatively low, limiting its full expression and translation into protein. Additionally, naked mRNA degrades quickly in vivo due to ribonucleases in biological fluids, resulting in instability.89,90 Exogenous mRNA can also be recognized by the body’s immune surveillance mechanisms, triggering innate immune responses that lead to mRNA degradation and inhibition of antigen expression.50

In terms of delivery, mRNA is a highly negatively charged long-chain macromolecule, hindering its direct crossing of cell membranes.91 Moreover, mRNA needs to be protected from RNAse degradation during systemic administration, and the mononuclear phagocyte system can recognize and eliminate foreign nanoparticles, limiting mRNA transfection efficiency.92 mRNA carriers need to release mRNA from endosomal vesicles to bind to host cell ribosomes and be translated into antigen proteins, but mRNA may be degraded within endosomal vesicles.50,93 Additionally, exogenous mRNA entering the cytoplasm is recognized by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and RIG-I-like receptors, activating the innate immune system, which may limit mRNA functionality.94,95

To address these issues, technological innovations have made progress. For example, high-performance liquid chromatography can remove double-stranded RNA, reducing innate immune activation and significantly increasing translation levels. Chemically modifying the backbone and UTRs of mRNA can improve its stability and translation efficiency. Incorporating modified nucleosides such as pseudouridine can prevent recognition by innate immune sensors, reducing immune activation and translation inhibition.96,97 Additionally, nanoparticles are designed to protect mRNA and help it to escape RNAse degradation, promoting its function in the cytoplasm through mechanisms such as the proton sponge effect and lipid flip.98

However, the stability, storage, and transportation of mRNA vaccines, as well as the selection of vaccine doses, remain technical challenges that need to be addressed.99 Most vaccines require cold chain transportation and storage, and the stringent low-temperature storage requirements for mRNA vaccines increase costs and distribution difficulties.53

Structure and optimization strategies of mRNA vaccines

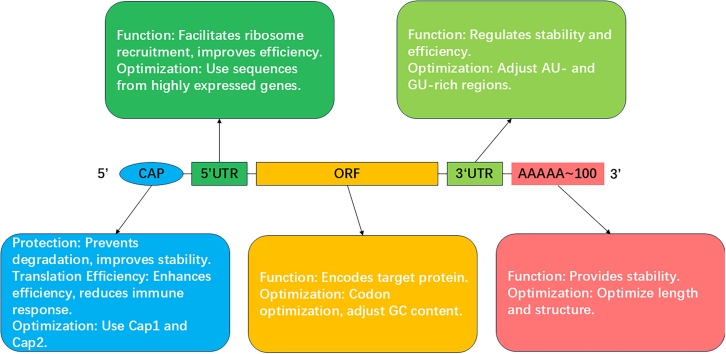

mRNA vaccines are composed of synthetic mRNA and delivery carriers. The mRNA consists of five key components: the 5′ cap, the 5′UTR, the ORF, the 3′UTR, and the 3′ polyadenylated tail (poly(A) tail).14 To enhance the stability and translation efficiency of mRNA, each component is often specifically modified and optimized (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the key structural elements and functions of IVT mRNA, highlighting their roles in stability and translation efficiency

5′ cap structure

The 5′ cap structure (Cap) of mRNA features an inverted 7-methylguanosine connected to the 5′ end via a 5′–5′ triphosphate bridge. This structure is crucial for protecting mRNA from nuclease degradation, promoting stability and enhancing translation efficiency.100,101,102 Capping methods include enzymatic capping103 and co-transcriptional capping.103,104,105 Enzymatic capping mimics the natural capping process in eukaryotes, producing high-quality cap structures despite lower efficiency.106 Co-transcriptional capping, using cap analogs during transcription, offers greater efficiency. Cap structures vary: Cap0 is the basic 7-methylguanosine cap,106,107 Cap1 involves methylation at the 2′-O position of the first nucleotide,108 and Cap2 involves additional methylation at the 2′-O position of the second nucleotide.109 Cap1 and Cap2 structures are commonly used in mRNA vaccines due to their resemblance to natural eukaryotic mRNA caps, which reduces innate immune responses and improves stability and translation efficiency. Trilink’s CleanCap technology enhances capping efficiency by using AG or AU trinucleotides, generating natural Cap1 structures during in vitro transcription and reducing immunogenicity.110 Other capping technologies are also being explored. For example, vaccinia capping enzyme (VCE) is an enzymatic method that produces precise Cap1 and Cap2 structures, though its capping efficiency is relatively lower.111 Anti-reverse Cap analog (ARCA) is a co-transcriptional cap analog that prevents incorrect cap incorporation and improves mRNA translation by ensuring the cap is in the correct orientation.112 Overall, co-transcriptional methods such as CleanCap and ARCA generally offer greater capping efficiency, making them more suitable for large-scale mRNA production. In contrast, enzymatic methods like VCE are known for their accuracy in producing natural cap structures, but may not be as efficient as co-transcriptional technologies for large-scale applications.

5′UTR

The 5′UTR of mRNA, located between the 5′ cap and the ORF, plays a crucial role in regulating translation efficiency and stability. The 5′UTR facilitates ribosome recruitment, scanning, and selection of the translation initiation codon.113 A well-structured 5′UTR, typically free from extensive secondary structures and internal initiation codons, is vital for efficient ribosome recruitment and accurate start site recognition. However, in some cases, secondary structures in the 5′UTR can serve as regulatory mechanisms for translation, particularly in stress responses where translation needs to be selectively activated or repressed.114 Such regulatory structures can modulate ribosome scanning speed or prevent premature translation initiation, which could be useful in highly regulated expression systems. Secondary structures in the 5′UTR, if not carefully optimized, can impede ribosome scanning, thereby reducing translation efficiency. Effective 5′UTRs often derive from highly expressed genes, such as those encoding globin115 and heat shock proteins, and are used to optimize mRNA expression. Other well-characterized 5′UTRs, such as those from viruses (e.g., internal ribosome entry site elements from picornaviruses), can allow translation in the absence of a 5′ cap, adding versatility in translation initiation under specific cellular conditions.116 Additionally, shortening the 5′UTR or modifying the distance between the ribosome binding site and the start codon has been shown to enhance translation efficiency. Adding regulatory elements, such as the Kozak sequence, can further boost translation efficiency and mRNA half-life by improving ribosome binding and increasing translation yield.117 Moreover, high-throughput screening and computational tools allow for the identification of optimal 5′UTR sequences, enabling fine-tuned mRNA translation and expression.118

ORF

The ORF encodes the target protein and directly impacts mRNA stability and translation efficiency. Optimizing the ORF involves codon optimization and GC content adjustment. Codon optimization increases translation efficiency and protein yield by selecting high-frequency synonymous codons that align with the host cell’s tRNA pool, reducing translation pauses and errors.119 In addition, certain rare codons may play a role in specific folding kinetics or co-translational regulation, suggesting that codon optimization should balance translation speed with proper protein folding. Over-optimization may lead to protein misfolding in some systems. Adjusting GC content enhances mRNA stability and translation efficiency, as higher GC content forms more stable secondary structures, protecting mRNA from degradation.120 However, excessive GC content could also introduce strong secondary structures in the ORF, potentially hindering translation elongation. Thus, an optimal balance is necessary to prevent excessive mRNA folding while maintaining stability.121 Reducing uridine content in the ORF decreases unnecessary immune activation. For example, CureVac reduces uridine content to lower mRNA immunogenicity, enhancing vaccine safety and efficacy.120 Modifying codon use and GC content as well as reducing uridine collectively ensure that the ORF supports both high levels of protein expression and reduced immune system activation, which is essential for vaccine efficacy.

3′UTR

The 3′UTR, located downstream of the ORF and near the poly(A) tail, is a critical regulator of mRNA stability, translation efficiency, and subcellular localization. The 3′UTR typically contains regulatory elements, including AU- and GU-rich regions,122 polyadenylation signals,123 and microRNA (miRNA) binding sites,124 all of which modulate mRNA turnover and translational control. Other regulatory elements, such as cytoplasmic polyadenylation elements, are crucial for mRNA localization and translation activation, particularly in oocytes and neurons.125 These elements allow spatially regulated translation during development or in response to cellular stimuli. The presence of AU-rich elements within the 3′UTR can promote mRNA decay, while removal or mutation of destabilizing elements can enhance mRNA stability and prolong half-life.126 By optimizing or truncating specific 3′UTR sequences, researchers can significantly reduce mRNA degradation, promoting intracellular stability and enhancing protein production. For example, the human hemoglobin β-globin 3′UTR is widely used to enhance mRNA stability and expression.127 In addition to human-derived sequences, 3′UTRs from other species or synthetic sequences can be engineered to create customized stability profiles, offering more versatility in mRNA design.128 Additionally, tandem 3′UTRs or synthetic 3′UTR sequences have been used successfully to further improve mRNA stability and translation efficiency.129 miRNA response elements within the 3′UTR also provide opportunities for post-transcriptional regulation, allowing for tissue-specific or condition-specific gene expression.130 Through precise optimization of the 3′UTR, mRNA half-life can be significantly extended, leading to increased protein production and more efficient translation.

Poly(A) tail

Most eukaryotic mRNAs have a poly(A) tail, which is crucial for mRNA stability, nuclear export, and translation efficiency. The poly(A) tail prevents decapping enzymes from binding to the cap and interacts with poly(A) binding proteins to form a closed-loop structure, thereby enhancing ribosome recycling, protecting mRNA from exonuclease-mediated degradation, and promoting translation initiation.131 Dynamic regulation of the poly(A) tail length is particularly important in oocytes, early embryos, and neurons, where translation is temporally controlled by polyadenylation and de-adenylation cycles, coordinating protein synthesis with developmental cues or synaptic activity.132 Optimizing the poly(A) tail length and structure is crucial, as an appropriate length (typically 100–250 nucleotides in mammalian cells) strikes a balance between mRNA stability and translation efficiency.14,133 Shorter poly(A) tails are generally associated with reduced translation and rapid mRNA degradation, while overly long poly(A) tails may lead to inefficient translation due to altered RNA-protein interactions.132 Emerging research also suggests that alternative polyadenylation sites can significantly influence the final 3′UTR length and poly(A) tail regulation, adding an additional layer of post-transcriptional control.134 Furthermore, dynamic regulation of poly(A) tail length, through cytoplasmic polyadenylation or de-adenylation, allows for fine-tuning of mRNA lifespan and translation in response to developmental and environmental signals.135 In addition to length, chemical modifications of the poly(A) tail, such as the addition of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) to adenosine residues, have been shown to enhance mRNA stability and regulate translation efficiency.136 The m6A-modified mRNA can recruit specific reader proteins (such as YTHDF1 and YTHDF2), which further regulate mRNA decay and translation, indicating a multi-layered regulatory mechanism for controlling gene expression.137 m6A modifications in the poly(A) tail also offer potential avenues for therapeutic mRNA design, enabling fine control of protein expression in gene therapies and vaccines.138 These modifications highlight the importance of post-transcriptional regulation in determining mRNA fate and offer potential avenues for therapeutic mRNA design, where fine-tuning the poly(A) tail can enhance mRNA stability and protein expression in vivo.

Immune mechanism of mRNA vaccines

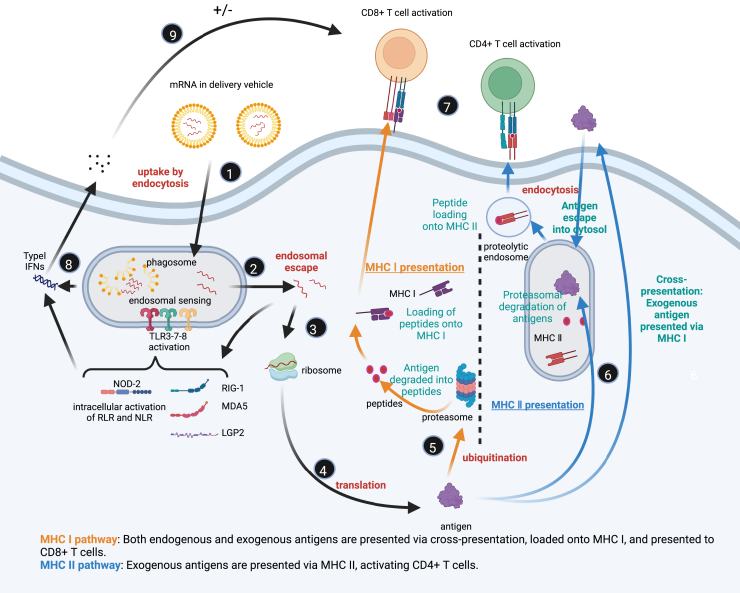

As illustrated in Figure 3, mRNA vaccines enter cells through endocytosis mediated by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), initiating a cascade of immune responses. Initially, mRNA is encapsulated in delivery vehicles, such as LNPs, and internalized by APCs via endocytosis (step 1). APCs, including dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages, are key immune cells responsible for recognizing and processing foreign antigens.139 After entering the cell, mRNA is enclosed in endosomes. For an effective immune response, the mRNA must escape from the endosome into the cytoplasm; otherwise, it will be degraded within the endosomal compartment (step 2).12 The mRNA delivery system, such as LNPs, plays a critical role in this process by protecting mRNA from degradation and facilitating its efficient intracellular delivery and release.53

Figure 3.

Mechanism of mRNA vaccine-mediated immune response

Created in BioRender. sun, n. (2024) BioRender.com/y07k630. (1) mRNA uptake via endocytosis: mRNA vaccines, encapsulated in LNPs, are taken up by cells via endocytosis. (2) Endosomal sensing and escape: Inside endosomes, mRNA is recognized by TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8, activating innate immune responses. mRNA then escapes into the cytosol to avoid degradation. (3) Cytosolic release of mRNA: The escaped mRNA is released into the cytosol, becoming available for translation. (4) Translation of mRNA: The ribosome translates mRNA into antigenic proteins. (5) Antigen processing and MHC I presentation: Antigenic proteins are degraded into peptides, which are transported to the endoplasmic reticulum and loaded onto MHC I molecules, then presented on the cell surface to activate CD8+ T cells. (6) MHC II presentation: Exogenous antigens are processed and loaded onto MHC II molecules, which are presented to CD4+ T cells. (7) T cell activation: CD8+ T cells are activated by MHC I-peptide complexes, inducing CTL responses, while CD4+ T cells are activated by MHC II-peptide complexes to coordinate immune responses. (8) Innate immune activation: Cytosolic receptors (retinoic acid-inducible gene I-like receptors [RLRs], NOD-like receptors [NLRs]) detect mRNA, triggering the production of type I IFNs and antiviral responses. (9) Adaptive immune regulation: CD8+ and CD4+ T cells generate immune memory, regulated by feedback mechanisms to maintain balance.

Once in the cytoplasm, mRNA is recognized by ribosomes and translated into antigenic proteins (steps 3 and 4). These proteins, as endogenous antigens, undergo intracellular processing and trigger adaptive immune responses. In the cytoplasm, antigenic proteins are degraded by the proteasome into smaller peptides (step 5), which are then loaded onto major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and presented to CD8+ T cells on the cell surface (step 7). This pathway primarily activates CTLs, which can recognize and destroy virus-infected or malignant cells. The cytotoxic T cell response induced by the MHC I pathway is one of the key mechanisms through which mRNA vaccines elicit long-lasting antiviral or antitumor immunity.140

In addition to activating CD8+ T cells via the MHC I pathway, some of the antigenic proteins may be secreted extracellularly or released after cell lysis, where they are re-internalized by APCs (step 6).141 Inside the endosomes, these exogenous antigens are degraded into peptides by lysosomal enzymes and loaded onto MHC class II molecules, which are subsequently presented to CD4+ T cells.142 CD4+ T cells activated via the MHC II pathway are crucial for humoral immune responses, assisting B cells in differentiating into plasma cells and producing specific antibodies to neutralize pathogens. The production of humoral immunity is essential for preventing future viral infections and their transmission.

mRNA vaccines not only activate CD8+ and CD4+ T cells through MHC class I and II pathways but also enhance adaptive immunity by triggering innate immune responses (step 8).12 After APCs uptake mRNA, it is recognized by PRRs within the cell.143 These PRRs include TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8 in the endosomes and retinoic acid-inducible gene I-like receptors in the cytoplasm.144,145 Recognition of mRNA by these receptors triggers downstream signaling pathways that induce the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and type I interferons (interferon-alpha and Nod-like receptor beta).124,146 These inflammatory factors help to recruit and activate additional immune cells while also providing critical activation signals to APCs, enhancing their antigen-presenting capabilities.147

However, excessive activation of innate immune responses can negatively affect the efficacy of mRNA vaccines.12 Overproduction of type I interferons may inhibit mRNA translation and accelerate its degradation, thereby reducing antigen production and weakening the immune response.124,148 Therefore, mRNA vaccine design must balance immune activation with the avoidance of excessive inflammation to ensure optimal immunogenicity. For example, pseudouridine-modified mRNA or mRNA purified by high-performance liquid chromatography reduces PRR interactions, thus limiting excessive innate immune activation while prolonging mRNA stability and antigen expression (step 9).149

Furthermore, the delivery systems of mRNA vaccines, such as LNPs, not only protect mRNA and facilitate its delivery but also act as adjuvants to enhance immune responses.150 LNPs expedite intracellular transport by fusing with cell membranes, and their lipid components can directly activate the innate immune system.151 Optimization of delivery systems is therefore crucial for maximizing mRNA vaccine efficacy. The use of LNPs has significantly improved antigen expression efficiency and the immunogenicity of mRNA vaccines, making it a core technology in current mRNA vaccine development.

In conclusion, mRNA vaccines activate both innate and adaptive immune responses through multiple pathways. After entering cells via endocytosis mediated by APCs, mRNA is translated into antigenic proteins by ribosomes, which activate CD8+ and CD4+ T cells through the MHC class I and II pathways, eliciting cytotoxic T cell and humoral immune responses. Additionally, mRNA vaccines trigger innate immune responses through PRRs, further enhancing immune activation and antigen presentation. In vaccine design, optimizing mRNA structure and delivery systems is key to improving stability, expression levels, and immunogenicity.152

Delivery systems

The synthetic mRNA segment of mRNA vaccines requires attachment to a carrier to function effectively. Currently, there are two primary types of carrier molecules in widespread use: viral vectors and non-viral vectors. The delivery system is crucial in mRNA vaccine development because mRNA is a large hydrophilic nucleic acid molecule rich in anionic groups, making it difficult to pass through the similarly negatively charged cell membrane.153 Early research predominantly used viral vectors, including adenovirus, adeno-associated virus, lentivirus, and herpes simplex virus. Although effective, these viral vectors have potential carcinogenicity and high immunogenicity, which may lead to severe clinical adverse events, thus limiting their clinical applications.154

With advancements in materials and preparation techniques, non-viral vectors have emerged as the preferred method for mRNA delivery. These non-viral vectors include liposomes, polymers, peptides, and inorganic nanomaterials. LNPs and polymer nanoparticles are particularly noted for their good biocompatibility and ease of preparation. These non-viral carriers can adsorb and concentrate mRNA, form stable nanoparticles, traverse the cytoplasmic membrane barrier, and safely deliver mRNA to APCs. Consequently, non-viral vectors are the mainstream choice for mRNA vaccine delivery due to their safety and efficacy.

LNPs

Recently, LNPs have made significant strides as delivery systems for mRNA vaccines and gene therapy drugs. LNPs, composed of lipid materials, offer high stability and biocompatibility, making them particularly suitable for mRNA vaccine delivery, as demonstrated in the development of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) mRNA vaccines. LNPs typically comprise ionizable lipids, helper phospholipids, cholesterol, and polyethylene glycol-lipids (PEG-lipids).155 Ionizable cationic lipids stabilize and release mRNA through pH-dependent charge changes, remaining neutral at a neutral pH but becoming positively charged in acidic environments, aiding in endosomal escape and mRNA release.156,157 Cholesterol enhances structural stability and modulates membrane fluidity by filling lipid gaps, helper phospholipids stabilize LNPs and improve delivery efficiency, while PEG-lipids prevent LNP aggregation, control particle size, prolong circulation time, and reduce immune system recognition, thereby enhancing the stability and efficiency of the delivery system.158 These components collectively form stable nanoparticle structures, protecting mRNA from degradation and facilitating its cellular entry.

The preparation methods of LNPs have been continually optimized, with microfluidic technology emerging as a novel method to produce uniform, size-controllable, stable, and reproducible LNPs. Microfluidic tools can precisely control flow rates, mixing, temperature, and time, enhancing transfection efficiency and simplifying the production process, thereby reducing time and cost.156

Researchers have also developed various new LNPs to improve delivery efficiency and stability. For instance, solid LNPs (SLNs) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) have shown promise in vaccine delivery.159 SLNs, when combined with negatively charged DNA molecules to form SLN/DNA complexes, have exhibited effective transfection capabilities and immune potential. NLCs, due to their thermal stability and ability to be freeze dried, remain stable under both room temperature and refrigerated conditions, demonstrating strong immunogenic effects.

Clinically, the success of LNPs is best exemplified by the development of mRNA vaccines. The COVID-19 mRNA vaccines developed by Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech (mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2) both use LNP delivery systems, showing high mRNA stability and efficient antigen delivery. This breakthrough underscores the significant role of LNPs in gene therapy and vaccine development.

Despite the significant advancements in LNP technology, there remain challenges in clinical applications. LNPs can potentially cause allergic reactions and rapid blood clearance.160 Researchers are exploring alternative materials and improved formulations to enhance safety and stability. Additionally, delivering nucleic acids to extrahepatic tissues remains challenging. Emerging selective organ targeting (SORT) technology offers new possibilities for overcoming this challenge, allowing targeted delivery to specific cells and organs in vivo through engineered SORT LNPs.161

Polymer nanoparticles

Polymer-based nanoparticles have also made notable progress in mRNA delivery, showing great potential as delivery carriers. Cationic polymer particles bind to mRNA vaccines through electrostatic interactions, bonding, or encapsulation, characterized by large surface areas and stable pharmacokinetics, enabling the efficient delivery of macromolecules. Additionally, polymer structures can be modified to reduce toxicity or enhance interaction with cell membranes by adding hydrophilic or hydrophobic groups.

Polyethyleneimine

Polyethyleneimine (PEI) is one of the most extensively studied cationic polymers. PEI has a high density of positive charges, binding to mRNA through electrostatic interactions to form stable complexes that protect mRNA from nuclease degradation and promote endosomal escape.162 However, PEI’s high toxicity limits its in vivo applications.163 Researchers have chemically modified PEI to reduce its toxicity, such as adding stearic acid, cyclodextrin, and PEG, significantly improving its biocompatibility and delivery efficiency.52,154,157 For example, PSA/mRNA nanoparticles use PEI’s positive charge to successfully deliver mRNA to DCs.164 Additionally, PEG-modified PEI has shown greater transfection efficiency and lower toxicity.154 The development of GO-PEI complexes has further enhanced mRNA delivery efficiency, demonstrating high reprogramming efficiency.165,166

Poly (β-amino esters)

Poly (β-amino esters) (PBAEs) have gained attention in mRNA delivery research due to their good biodegradability and biocompatibility. PBAEs can activate DCs and enhance antigen presentation while improving mRNA transfection efficiency.165 Chemical modifications have further optimized PBAE performance. For instance, oligopeptide end-modified PBAEs significantly enhance mRNA transfection efficiency.167

The PACE polymer library, prepared by brief vortexing, has demonstrated the potential for spleen-specific mRNA delivery.154 Furthermore, PCL-based PBAE terpolymers can accumulate in the spleen after intravenous administration, facilitating tumor immunotherapy.154

Other polymers

Other polymers have also shown important applications in mRNA delivery. Nanoparticles based on polyhydroxyalkanoates and poly(amino-co-ester) offer good biodegradability and stability.168 These polymers achieve targeted delivery to specific tissues and cells by optimizing terminal structures and molecular weights.

Novel polymers such as hyperbranched PBAE and chitosan-coated PLGA nanoparticles have shown excellent performance in delivering mRNA to specific organs, such as the lungs.165 Charge-altering releasable transporters are biodegradable polymers that effectively load and release mRNA through degradation, charge neutralization, and intramolecular rearrangement, facilitating functional mRNA and protein expression in cells.167

Additionally, PEI-poly(aspartic acid) polymer carriers have demonstrated efficient delivery and release in animal models. Subcutaneous injection delivery systems based on PEG[Glu(DET)]2 polymers have been used for treating muscle atrophy,169 while PEG-PAsp(DET) has been used for delivering brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA to treat spinal cord injuries.170 The application of polymer compounds and their derivatives in mRNA delivery offers new hope for treating various diseases. Through various modifications and improvements, polymer carriers not only enhance delivery efficiency and safety but also show broad application potential in cancer, lung disease, neurological disorders, and muscle atrophy.

Other delivery systems

-

•

Protamine: Protamine, a natural cationic peptide, has made significant strides in mRNA delivery research. By forming stable complexes with mRNA through electrostatic interactions, protamine effectively protects mRNA from RNase degradation. This protection not only ensures mRNA stability but also triggers specific T cell and B cell immune responses against mRNA-encoded antigens, thereby enhancing the efficacy of vaccines and therapies.171 Protamine demonstrates excellent biocompatibility and delivery efficiency, exhibiting adjuvant-like properties. For instance, in the rabies vaccine candidate CV7201, protamine is used as both a stabilizer and immunoadjuvant, with the vaccine designed based on mRNA encoding the rabies virus glycoprotein.172 Studies indicate that functionalization or derivatization of protamine-nucleic acid complexes can further enhance their efficacy. Encapsulating protamine-mRNA complexes with cationic liposomes, for example, can enhance DC maturation, thereby improving immune response effectiveness.173 Moreover, protamine has shown potential in tumor therapy and vaccine development, enhancing mRNA delivery efficiency and broadening its application in biomedical research.52 These features have led to its evaluation in clinical trials, confirming its potential in mRNA delivery systems.

-

•

Inorganic nanoparticles: Inorganic nanoparticles, such as those made from gold, silica, and metal oxides, are being explored for medical applications. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), noted for their chemical inertness and non-toxicity, are particularly promising.174 AuNPs can be functionalized with various ligands, showing great potential in targeted immune cell delivery and enhancing immune responses. For example, polymer-coated AuNPs loaded with antigens can target B lymphocytes and activate CD4 T cell responses, increasing vaccine efficacy.175 However, their chemical inertness can result in prolonged half-lives, limiting clinical use. To address this, researchers are combining Au with copper sulfide to enhance excretion and improve metabolism in hepatocytes.176 Other inorganic nanoparticles, such as silica and iron oxide nanoparticles, are also being studied for targeted delivery and medical applications.177 These studies highlight the broad potential of inorganic nanoparticles in medicine.

-

•

Cationic cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) and anionic peptides: CPPs and anionic peptides are promising in new delivery methods. CPPs are small peptides that can directly penetrate cell membranes, increasing mRNA delivery efficiency, and are particularly useful for inducing immune responses. Common CPPs, include RALA peptide and PepFect14.178 Studies show that CPPs can enhance T cell immune responses, modulate innate immune responses, and increase protein expression in DCs and human cancer cells without cytotoxicity.166 Anionic peptides also offer high delivery efficiency and low cytotoxicity, especially in DCs. Overall, these peptide-based systems have broad potential for enhancing immune responses and protein expression.

-

•

Liposome complexes (LPs): Liposomes are spherical vesicles formed by phospholipid bilayers179,180 and are widely studied for delivering small molecule drugs, gene drugs, protein drugs, and hormones. Cationic liposomes, carrying a positive charge, can effectively condense nucleic acids, offering good pharmacokinetic properties. LP delivery of mRNA offers advantages such as nuclease resistance, high transfection efficiency, no host restriction, and long-term storage stability. Although both LPs and LNPs are LNPs, their preparation and mRNA encapsulation processes differ significantly. Methods for preparing LPs include thin-film dispersion, solvent injection, freeze drying, and pH gradient methods.166 Examples include Michel et al.181 using thin-film dispersion to prepare cationic liposomes encapsulating mRNA, Kuznetsova et al.182 achieving high stability with modified liposomes, Mai et al.173 using specific liposome components to stimulate DCs and induce antitumor responses, Zhang et al.183 enhancing mRNA delivery and DC activation with modified liposomes, and Huang et al.184 inducing SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific antibodies in mice.

-

•

Cationic nanoemulsions (CNEs): CNEs are a promising nucleic acid delivery system first proposed in 1990.185 They have proven effective for delivering nucleic acids to treat various diseases. The inclusion of cationic lipids in CNE formulations is crucial, as they bind to nucleic acids through electrostatic interactions, enhancing stability and transfection efficiency while protecting nucleic acids from nuclease degradation.186 Studies indicate that saRNA CNE systems can enhance local immune environments by recruiting immune cells and inducing antibody and T cell responses with low doses (75 μg) of saRNA.187

-

•

Exosomes: Exosomes, nano-sized vesicles naturally secreted by cells188 with diameters between 30 and 100 nm, have promising potential as mRNA vaccine delivery vectors due to their excellent biocompatibility and low immunogenicity. Exosomes can protect mRNA from degradation and efficiently cross biological barriers to target cells through their natural membrane structures, significantly improving mRNA vaccine stability and immune response.189 The surface of exosomes can be modified with specific ligands or antibodies to enhance targeting and delivery efficiency to specific immune cells or tissues, improving vaccine efficacy and safety.190 Research indicates that exosomes reduce phagocytosis by monocytes and macrophages, enhance uptake by cancer cells, and exhibit tropism for source cells, making them potential tools for targeting cancer cells.191 Additionally, exosomes can efficiently deliver exogenous miRNA to hepatocytes or macrophages with high delivery efficiency and low cytotoxicity.192 Exosomes can also cross the blood-brain barrier,193,194 targeting the brain and showing potential for treating brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, autism, stroke, and Parkinson’s disease with RNA-based drug delivery.165 Thus, exosomes as mRNA vaccine delivery vectors have broad future applications.

Mosquito-borne virus mRNA vaccines

Mosquito-borne viruses that affect humans are primarily found in three families: Flaviviridae (genus Flavivirus), Togaviridae (genus Alphavirus), and Bunyaviridae (mainly genus Orthobunyavirus).195 These viruses have distinct genomic structures (Figure 4). The Flaviviridae family has a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome, approximately 10–12 kb in length.196 It encodes a polyprotein that is processed by host and viral proteases into three structural proteins (C, premembrane [prM], E) and seven nsPs (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5).197 Similarly, the Togaviridae family has a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome that is approximately 11–12 kb long, divided into two parts that encode nsPs (nsP1-nsP4) and structural proteins (C, E1, and E2).198 The Bunyaviridae family (genus Orthobunyavirus) has a more complex genome, consisting of single-stranded negative-sense or ambisense RNA, divided into three segments (S, M, and L). These segments encode nucleoprotein (N), glycoproteins (Gn and Gc), and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L).199

Figure 4.

Mosquito-borne virus genome

(A) Flaviviridae (single-stranded positive-sense RNA): DENV, ZIKV, JEV, YFV (B) Togaviridae (single-stranded positive-sense RNA): CHIKV, VEEV (C) Bunyaviridae (single-stranded negative-sense RNA): RVFV.

Mosquito-borne flaviviruses of medical significance are divided into two categories: those associated with Aedes mosquitoes,200 typically causing hemorrhagic diseases such as dengue fever and YF,201 and those associated with Culex mosquitoes, usually causing encephalitic diseases such as Japanese encephalitis and West Nile virus.202

Monitoring and controlling these mosquito-borne viruses is crucial for public health. Currently, mRNA vaccines focus on genes encoding viral surface proteins, such as the E protein of DENV, ZIKV, JEV, and YFV, as well as the Gn and Gc glycoproteins of RVFV.25,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210 Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of mRNA vaccine development for mosquito-borne viruses, summarizing design strategies, immune responses, and developmental stages. These proteins are essential for the interaction between the virus and host cell receptors, inducing effective immune responses. A detailed understanding of the genomic structure of mosquito-borne viruses and vaccine target proteins is vital for developing and improving measures to control the spread and outbreaks of these diseases.

Table 2.

Overview of mRNA vaccine development for mosquito-borne viruses: Design, immune responses, and developmental stages

| Vaccine name | Target virus | Target | Design | Immune response | Stage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV E-DIII+ NS1 | DENV | E-DIII NS1 | chimeric antigen mRNA vaccine encoding DENV-1/4 (E-DIII 303–395 aa) and DENV-2/3 (NS1 1–302 aa) structural proteins, encapsulated in LNPs | induced strong antiviral immune responses and neutralizing antibody titers, blocking all four types of DENV infection without notable ADE a single injection favored T helper type 1 over T helper type 2 specific T cell responses |

animal model (C57BL/6 mice) | He et al.211 |

| DENV1-NS | DENV-1 | NS3 NS4B NS5 | mRNA-LNP | strong antiviral CD8+ T cell response, significantly reduced viral load | animal model (HLA transgenic mice) | Roth et al.212 |

| prME+ E80 + NS1 mRNA | DENV-2 | prME, E80, NS1 | nucleotide-modified mRNA | three nucleotide-modified DENV-2 mRNA vaccines (prime-mRNA, E80-mRNA, and NS1-mRNA) and the combination vaccine (E80-mRNA + NS1-mRNA) induced high levels of neutralizing antibodies and antigen-specific T cell responses, providing comprehensive protection against DENV-2 in immunocompetent mice | animal model (BALB/c mice) | Zhang et al.203 |

| prM/E mRNA-LNP | DENV-1 | prM, E | nucleotide-modified mRNA-LNP | neutralizing antibody response (EC50 1/400), reduced ADE levels | animal model (AG129 immunodeficient mice) | Wollner et al.204 |

| Quadrivalent Modified Nucleotide mRNA Vaccine for DENV | DENV | NS1, prM, and EIII protein domains | nucleotide-modified mRNA encoding optimized codon sequences for NS1, prM, and EIII proteins | predicted to induce B cell and T cell responses, including CTL and helper T lymphocyte targets | research and development phase, including immunoinformatics analysis, molecular modeling, and immuno-simulation experiments | Mukhtar et al.213 |

| ZIKV prM-E mRNA-LNP | Zika | prM, E | mRNA-LNP | specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies, T cell response, reduced viral load | animal model (AG129 mice) | Medina-Magües et al.214 |

| Modified mRNA Vaccine | Zika | structural genes | nucleotide-modified mRNA with N7mGpppG cap, enzymatic modifications, and specific UTR sequences | high levels of neutralizing antibodies and antigen-specific T cell responses | animal model (immunocompetent rodents) | Richner et al.215 |

| saRNA (CNE) Vaccine | Zika | prM and envelope (E) glycoproteins | saRNA, encoding ZIKV prM and E glycoproteins, delivered using CNE | induced potent neutralizing antibody responses and protection in mice and non-human primates, particularly VRC5283 candidate vaccine fully protected non-human primates from ZIKV infection | animal model (mice and non-human primates) | Luisi et al.216 |

| sr-prM-E-mRNA Vaccine | Zika | prM, E glycoproteins | self-replicating mRNA, encoding ZIKV prM, and E glycoproteins, using N7mGpppG cap sequence, enzymatic modifications, specific UTR sequences | induced potent humoral and cellular immune responses in IFNAR1 knockout mice, low antibody titers in wild-type mice, strong type I IFN response | animal model (IFNAR1 knockout mice, BALB/c mice, C57BL/6 mice) | Zhong et al.208 |

| mRNA-1325 and mRNA-1893 | Zika | prM, E | mRNA-based vaccine encoding prME from ZIKV isolates (Micronesia 2007 for mRNA-1325 and RIO-U1 for mRNA-1893) | induced specific neutralizing antibody responses; mRNA-1893 demonstrated strong immune response and good tolerance at all dose levels without baseline flavivirus serostatus impact | phase 1 clinical trial (healthy adults, 18–49 years, flavivirus seronegative or positive) | Essink et al.217 |

| Nucleotide-modified mRNA-LNP | Zika | prM, E | nucleotide-modified mRNA encapsulated in LNPs encoding prME from the 2013 ZIKV outbreak strain | single low-dose intradermal immunization induced potent and durable neutralizing antibody responses in mice and non-human primates, with protective effects lasting for ≥5 months | animal model (mice and non-human primates [rhesus monkeys]) | Pardi et al.218 |

| mRNA-LNP (prM and E proteins) | JEV | prM, E | modified mRNA-LNP | high-level protein expression, effective neutralizing antibody and CD8+ T cell immune responses, protected mice from lethal JEV challenge, reduced virus-induced neuroinflammation | animal model (mice) | Chen et al.25 |

| mRNA Vaccine | CHIKV | structural proteins | mRNA encoding CHIKV structural proteins | strong neutralizing antibody and T cell responses | animal model (mice) | Liu et al.219 |

| mRNA-LNP Vaccine | CHIKV | E2-E1 antigens | mRNA-LNP expressing CHIKV E2-E1 antigens | strong neutralizing antibody and cellular immune responses, particularly CD8+ T cell responses | animal model (mice) | Ge et al.220 |

| mRNA Monoclonal Antibody Vaccine | CHIKV | monoclonal antibody (CHKV-24) | mRNA encoding CHIKV monoclonal antibody | protected mice from arthritis, musculoskeletal tissue infection, and lethality; significantly expressed antibody levels in monkeys | animal model (mice, monkeys) | Kose et al.221 |

| mRNA-1388 Candidate Vaccine | CHIKV | structural proteins | mRNA encapsulated in LNPs, encoding CHIKV-specific antigens | induced high and durable neutralizing antibody responses in healthy adults, particularly at 50 μg and 100 μg doses, maintaining high antibody levels for 1 year after vaccination | phase 1 clinical trial | Shaw et al.207 |

| taRNA Candidate Vaccine | CHIKV | non-structural and envelope proteins | comprising nrRNA encoding CHIKV nsPs and a trans replicon RNA encoding CHIKV envelope proteins | induced potent CHIKV-specific humoral and cellular immune responses; two 1.5-μg RNA vaccine doses protected mice from high-dose CHIKV challenge infection | animal model (mice) | Schmidt et al.222 |

| mRNA Vaccine | CHIKV | envelope glycoproteins | mRNA designed through reverse vaccinology | predicted to induce effective humoral and cellular immune responses | computational design and simulation phase | Jaan et al.223 |

| mRNA-1944 | CHIKV | CHIKV-specific monoclonal neutralizing antibody (CHKV-24) | mRNA-LNP encoding heavy and light chains of the CHKV-24 neutralizing antibody | produced neutralizing CHKV-24 IgG antibodies with dose-dependent increase and duration of ≤16 weeks | phase 1 clinical trial | August et al.206 |

| E1988 | YFV | envelope protein | vaccine candidate system designed based on alignment of 216 envelope protein sequences, using codon optimization, RNA secondary structure prediction, immunological prediction tools, and molecular dynamics simulations | high immunogenicity and conservativeness, effectively stimulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses; validated T and B cell epitopes showed high-affinity interactions with HLA alleles and antigen clearance response through immunosimulation, with efficient translation and stability in host cells | computational design and simulation phase | Khan et al.205 |

| mRNA YF candidate vaccine | YFV | prM-E and NS1 proteins | mRNA-LNP | prM-E immune sera showed 100% protection, NS1 immune sera showed partial protection, induced both humoral and cellular immune responses, sustained high-level responses in mice and monkeys for ≥5 months | animal model (A129 mice and rhesus monkeys) | Medina-Magües et al.22 |

| mRNA-GnGc | RVFV | Gn and Gc proteins | six nucleotide-modified mRNA vaccines encoding different regions of RVFV Gn and Gc proteins; mRNA vaccines encoding full-length Gn and Gc proteins induced the strongest immune responses | induced strong cellular and humoral immune responses in mice, with vaccinated mice protected from lethal RVFV challenge | animal model (IFNAR−/−) mice and rhesus monkeys) | Bian et al.224 |

| A38-mRNA-LNP | RVFV | neutralizing antibody A38 protein | mRNA-LNP platform expressing RVFV neutralizing antibody A38 protein | A38 protein encoded by mRNA showed high binding and neutralization capability, longer circulating half-life, and sustained protein levels compared with directly injected free A38 protein | animal model (in vivo pharmacokinetic studies in mice) | Mahony et al.24 |

Dengue fever

DENV affects approximately 130 countries, with nearly 390 million cases reported annually, 96 million of which (25%) manifest significant clinical symptoms, with 500,000 requiring hospitalization.225 Dengue causes more human illnesses than any other mosquito-borne virus, with cases increasing by more than 400% in recent decades.226,227 The virus comprises four main serotypes, and its extensive sequence and genetic diversity complicate vaccine development.228,229,230 DENV-2 is most closely associated with dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS), followed by DENV-1 and DENV-3, while DENV-4 generally causes milder disease.231 Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) is a key theory in the pathogenesis of DHF/DSS, with higher DHF/DSS risk in secondary infections due to antibody-enhanced viral replication and immune activation.232

Traditional live-attenuated vaccines have shown some promise in clinical trials but face challenges such as balancing seroconversion, cross-immune responses, and cellular response levels. The inherent risks of live-attenuated vaccines necessitate the search for safer vaccine alternatives.

The mRNA vaccine platform has shown great potential, particularly highlighted by the success of COVID-19 vaccines, spurring interest in dengue vaccine development. mRNA vaccines can induce broad-spectrum and durable neutralizing antibody responses with potentially lower ADE risk.

Multi-target design has shown significant promise in mRNA vaccine development.211 Using mRNA-LNP technology to encode DENV envelope domain III (E-DIII) and nsP 1 (NS1) can induce broad-spectrum immune protection. A study211 developed an improved mRNA vaccine containing E-DIII and NS1, encapsulated in LNPs, demonstrating potential in inducing broad-spectrum neutralizing antibodies. This multi-target mRNA vaccine blocked all four DENV types in a mouse model.

A prM/ENV mRNA vaccine targeting DENV-1 induced high-titer neutralizing antibody responses at both high (10 μg) and low (3 μg) doses, with half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) values reaching 1/400.233,234 This vaccine induced anti-DENV CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses and enhanced antiviral T cell responses by increasing NS1 RNA.233,234 The DENV1-NS mRNA vaccine induced strong antiviral CD8+ T cell responses in HLA-transgenic mice and significantly reduced viral load upon DENV1 challenge. Additionally, Zhang et al.203 demonstrated that combined E80+NS1 mRNA vaccination elicited antigen-specific T cell responses, enhancing vaccine protection. Inoculation of BALB/c mice with mRNA encoding the soluble part of the DENV-2 ENV (E80) elicited humoral and cell-mediated immune responses, preventing lethal homologous serotype DENV2 challenge. Adding NS1 RNA to the E80 RNA vaccine increased antiviral T cell responses.233,235

Using LNPs to encapsulate mRNA improves vaccine stability and immunogenicity.204 Wollner et al.204 proposed constructing a nucleotide-modified mRNA vaccine for DENV serotype 1, encoding membrane and envelope structural proteins (prM/E mRNA-LNP). This vaccine induced neutralizing antibody responses with EC50 values reaching 1/400 through an intramuscular prime-boost strategy and significantly reduced heterologous ADE levels in K562 cells.235 Additionally, vaccination showed significant protective effects in AG129 immunodeficient mice.

Roth et al.212 developed an mRNA-LNP vaccine named DENV1-NS, targeting the most immunogenic parts of the nsPs NS3, NS4B, and NS5 of DENV-1. This vaccine elicited strong antiviral CD8+ T cell responses212,233,234,235 and significantly reduced viral load upon DENV1 challenge. Due to the homology among NS protein parts in DENV serotypes, antiviral T cells induced by vaccination exhibited partial cross-reactivity among all four dengue serotypes.233

Despite the great potential of mRNA vaccines in dengue vaccine development, challenges remain. Evaluating the broad-spectrum activity of DENV vaccines requires further optimization of design and evaluation methods. Selecting appropriate animal models and measuring viral load are crucial for evaluating vaccine efficacy. Additionally, comprehensively considering humoral and cellular immune responses is important for fully assessing vaccine protection. In summary, the mRNA vaccine platform offers new possibilities for developing safer and more effective DENV vaccines. The application of multi-target design and LNP technology has significantly improved vaccine stability and immunogenicity, providing new ideas for dengue vaccine development. Future research should continue to optimize mRNA vaccine design and evaluation, comprehensively considering humoral and cellular immune responses to achieve broad-spectrum and durable protection against DENV infection.

ZIKV

ZIKV was first discovered in 1947 in the Zika Forest of Uganda and has gained widespread attention in recent years due to global outbreaks.233,236,237 ZIKV is mainly transmitted by A. aegypti mosquitoes, but can also be transmitted through sexual contact, blood transfusion, and the placenta, leading to fetal developmental abnormalities during pregnancy.238,239 Approximately 2.17 billion people live in areas at risk of ZIKV transmission,192 and more than 40% of pregnant women infected with ZIKV have fetuses with congenital neurological abnormalities, such as postnatal neurodevelopmental deficits, ocular abnormalities, and microcephaly.240 These severe diseases place a heavy burden on public health systems. In response to the ZIKV epidemic, researchers rapidly developed various vaccines, including mRNA vaccines. Medina-Magües et al.214 constructed an mRNA vaccine (ZIKV prM-E mRNA-LNP) and evaluated its efficacy in AG129 mouse models. Experimental results showed that vaccination induced specific immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 and IgG2a isotype antibodies and T cell responses, significantly reducing viral load in vivo. Additionally, modified mRNA vaccines encoding wild-type or mutant ZIKV structural genes, encapsulated by LNPs, induced high-titer neutralizing antibodies.215 A nucleotide-modified mRNA vaccine encoding ZIKV prM and envelope glycoproteins also induced effective and durable neutralizing antibody responses through a single low-dose intradermal immunization.241 Some studies found that using CNEs to deliver saRNA vaccines encoding ZIKV prM glycoproteins induced effective neutralizing antibodies in mice and non-human primates.216 Additionally, saRNA vaccines encoding prM glycoproteins induced strong humoral and cellular immune responses in IFNAR1−/− C57BL/6 mice, providing complete protection against ZIKV infection.208 Moderna’s ZIKV mRNA vaccine, mRNA-1893, has completed phase 1 clinical trials, showing higher efficacy than mRNA-1325, with phase 2 clinical trials underway and expected to be available soon.217 Pardi et al.218 immunized mice and non-human primates with mRNA-LNPs targeting ZIKV prM-E, resulting in the rapid induction of high-titer neutralizing antibodies and durable immune effects with a single immunization.

JEV

JEV is a significant zoonotic pathogen that causes central nervous system symptoms in humans and reproductive disorders in pigs, seriously affecting human health and the swine industry. There are an estimated 50,000 clinical cases and 10,000 deaths annually in Asia, with a high incidence of neuropsychiatric sequelae among survivors.202,242 With no effective treatment available, vaccination is the best measure to prevent the disease.

A study25 developed a modified mRNA vaccine encoding the prM and E proteins of the JEV P3 strain, delivered through LNP. This vaccine showed high levels of protein expression in vitro and significant immunogenicity in mouse models, inducing effective neutralizing antibody and CD8+ T cell-mediated immune responses. The results indicate that this mRNA vaccine could protect mice from lethal JEV challenge and reduce virus-induced neuroinflammation. This study lays the foundation for further development of Japanese encephalitis mRNA vaccines, providing a more efficient and safer vaccine option.

CHIKV

In recent years, the global spread of CHIKV infection has presented significant challenges to public health. CHIKV infection typically manifests as an acute viral illness, with key symptoms including fever, rash, and joint pain. Some patients may develop chronic arthritis, which can even be life-threatening. Although CHIKV infection does not have a high fatality rate, its long-term consequences severely impact patients' quality of life. Currently, there are no approved vaccines or specific antiviral drugs for the prevention or treatment of CHIKV infection, underscoring the need for vaccine development to control this virus’s spread.

Significant progress has been made in CHIKV vaccine development in recent years. Among these advancements, mRNA vaccine technology has become a major focus of research. Studies have shown that mRNA-based CHIKV vaccines demonstrate good immunogenicity and ease of production. Specifically, one study23 used mRNA-encoding CHIKV structural proteins to elicit an immune response against CHIKV in host cells through mRNA delivery. In mice, this vaccine induced strong neutralizing antibody and T cell responses. Another study220 developed an mRNA-LNP vaccine expressing CHIKV E2-E1 antigens. Compared with traditional protein vaccines, the mRNA-LNP vaccine induced stronger neutralizing antibody and cellular immune responses, particularly CD8+ T cell responses, demonstrating more pronounced protective effects.

Additionally, another study243 used attenuated live RNA hybrid vaccine technology, delivering the attenuated viral genome transcribed in vitro to the inoculation site to achieve vaccine production in a cell-free environment. This vaccine elicited high levels of neutralizing antibodies and effective protective capacity in animal models, providing a novel approach for CHIKV infection control. Another study22 used ultra-potent neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies isolated from naturally infected CHIKV survivors, encoding them into mRNA molecules and delivering them via infusion. This approach demonstrated significant protective capacity in animal models, providing a new therapeutic method for CHIKV prevention. Similarly, Kose et al.221 encoded CHIKV monoclonal antibodies into mRNA, demonstrating potential in preventing infection in animal models. The mRNA-1388 candidate vaccine207 demonstrated a favorable safety profile and reactivity in the first human trials in healthy adults, especially in the 50 μg and 100 μg dose groups, inducing large and persistent neutralizing antibody responses lasting up to one year after vaccination. Another candidate vaccine based on taRNA222 induced strong immune responses and good safety in mouse models, providing protection with minimal dosage. Using reverse vaccinology, researchers designed an mRNA vaccine targeting the envelope glycoproteins223 and validated its efficacy. The mRNA-1944 demonstrated safety and pharmacological advantages in human clinical trials, showing neutralizing activity after a single infusion and increased IgG levels after a second injection, presenting potential as a treatment option for CHIKV infection.206

Overall, these studies provide novel insights and approaches for the development of CHIKV mRNA vaccines, showing potential for future clinical applications. However, despite significant progress, further clinical studies and evaluations are needed to verify their safety and efficacy in humans, contributing more significantly to the control and prevention of CHIKV infection.

YFV

YF, caused by the YFV, is a severe infectious disease primarily endemic in Africa and South America. Despite the availability of an effective vaccine for nearly 80 years, YF continues to pose a threat to travelers and residents in endemic areas.40 Annually, YF causes approximately 60,000 deaths and threatens the health of 900 million residents and travelers in 44 endemic countries in Latin America and Africa.244 Due to the limited supply of the current YF vaccine, there is an urgent need for new vaccines to alleviate future outbreak pressures.

Researchers have designed mRNA vaccines targeting envelope proteins. One study22 evaluated the immunogenicity and protective activity of mRNA vaccines expressing YFV prM and envelope proteins or nsP1. Experiments in mice and rhesus monkeys demonstrated that these mRNA vaccines effectively prevent lethal YFV infections by inducing high levels of humoral and cell-mediated immune responses. In monkeys, these vaccines sustained high levels of humoral and cellular immune responses for at least 5 months after vaccination, indicating long-term immunoprotection.