Highlight

-

•

Innovative Study on Naringenin Inducing Ferroptosis in Osteosarcoma.

-

•

The Key Role of the STAT3-MGST2 Pathway in Ferroptosis.

-

•

The Clinical Application Value of Naringenin in Osteosarcoma Treatment.

-

•

Therapeutic Targets for Osteosarcoma.

Keywords: Osteosarcoma, Ferroptosis, Naringenin, STAT3, MGST2

Abstract

Osteosarcoma is a common malignant tumor found in adolescents, characterized by a high metastatic potential and poor prognosis, but it is sensitive to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Ferroptosis is a novel form of regulated cell death induced by excessive iron accumulation, leading to lipid peroxidation that results in cellular dysfunction and death. Naringenin is a flavonoid known for its anti-cancer properties, yet its role in osteosarcoma has not been thoroughly studied. In this study, we found that naringenin significantly reduced the viability of osteosarcoma cells while increasing the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), iron overload, and the excessive expression of malondialdehyde (MDA). Bioinformatics analysis revealed that microsomal glutathione S-transferase 2 (MGST2) is highly expressed in osteosarcoma cells. Silencing MGST2 decreased the proliferation, migration, and invasion of these cells and enhanced their sensitivity to ferroptosis. Mechanistically, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) binds to the MGST2 promoter, promoting its transcription. Naringenin inhibits STAT3, blocking the expression of MGST2, while the STAT3 agonist Colivelin reverses this effect. In vivo experiments further confirmed that naringenin inhibited tumor growth in subcutaneous xenograft models and exhibited good biosafety. In summary, our study demonstrates that naringenin induces ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells through the STAT3-MGST2 signaling pathway, providing a promising strategy for osteosarcoma treatment.

1. Introduction

Osteosarcoma is a common malignant bone tumor that primarily occurs at the metaphysis of long bones. It is characterized by a high degree of malignancy and a tendency to lead to pulmonary metastasis, resulting in relatively poor prognosis, especially among adolescents and children [1], [2]. Follow-up data show that the five-year survival rate for osteosarcoma patients without pulmonary metastasis is approximately 70 %, while the survival rate for those with pulmonary metastasis drops to 30 % [3], [4]. For early-stage osteosarcoma, curative outcomes can be achieved through radical wide resection. Osteosarcoma is highly sensitive to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy are crucial for controlling local recurrence and metastasis, as well as improving survival rates. However, the five-year survival rate for osteosarcoma patients remains unsatisfactory [5]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore new therapeutic strategies for the comprehensive treatment of osteosarcoma [6].

Ferroptosis is a novel form of cell death characterized by an iron dependency and the occurrence of lipid peroxidation [7], [8]. Multiple factors can directly or indirectly promote ferroptosis. Biochemically, intracellular iron overload, glutathione (GSH) depletion, reduced activity of glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX), and accumulation of lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS) are major triggers of ferroptosis. Furthermore, lipid peroxides cannot be metabolized in reduction reactions, further promoting oxidative cell death [9], [10], [11]. At the microscopic level, ferroptosis is typically associated with a reduction in mitochondrial volume, an increase in double membrane density, and a decrease or disappearance of mitochondrial cristae. From a genetic perspective, ferroptosis is regulated by multiple signaling pathways. Among these, glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), a member of the GPX family, utilizes glutathione (GSH) as a cofactor to convert lipid peroxides into lipid alcohols, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis [11], [12]. Cysteine is a rate-limiting precursor for the synthesis of glutathione (GSH), while SLC7A11 is a multifunctional transmembrane protein that regulates the reverse transport of cystine and glutamate, influencing GSH synthesis and subsequently modulating ferroptosis [13]. Therefore, small molecules targeting these pathways have been confirmed to induce or inhibit ferroptosis. For instance, Erastin (Era) inhibits the activity of the cystine-glutamate transporter (systemXC-), obstructing GSH synthesis, which leads to the accumulation of lipid peroxides and promotes ferroptosis. Conversely, Deferoxamine (DFO), an iron chelator, can suppress the generation of lipid reactive oxygen species, thereby reducing ferroptosis in cells. Increasing evidence suggests that ferroptosis plays a significant role in cancer therapy [14], [15], [16].

Naringenin is an important plant compound that belongs to the flavanone class of polyphenols. It is mainly found in citrus fruits such as grapefruit, as well as in tomatoes, cherries, and some medicinal plants [17], [18]. Studies have shown that naringenin, as an herbal remedy, possesses significant pharmacological activity and can prevent cancer progression through various mechanisms, including inhibiting the proliferation and migration of cancer cells [19], [20]. In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that pure naringenin, naringenin-loaded nanoparticles, and the combination of naringenin with anticancer drugs can effectively inhibit the carcinogens of various malignant tumors, including colon cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, leukemia, lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, prostate tumors, oral squamous cell carcinoma, brain tumors, skin cancer, cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, bladder tumors, and osteosarcoma [21]. Naringenin inhibits cancer progression through various mechanisms, including affecting the mitochondrial function of tumors, inducing apoptosis, blocking the cell cycle, inhibiting angiogenesis, and regulating multiple signaling pathways [22].

Microsomal glutathione S-transferase 2 (MGST2) is a member of the MAPEG family, which consists of a type of integral membrane proteins involved in the metabolism of eicosanoids and glutathione. MGST2 is an important target for several anti-inflammatory and anticancer drugs that exert their effects by interfering with the biosynthesis of prostaglandins and leukotrienes [23].

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) is a key oncogene that has dual functions in signal transduction and transcriptional activation [24]. The overactivation of STAT3 is a crucial step in the development of most human cancers, playing a significant role in processes such as cell proliferation, angiogenesis, metastasis, and immune suppression [24], [25], [26]. It can bind to common DNA response elements in the promoters of ferroptosis-related genes, such as GPX4, SLC7A11, and FTH1, thereby regulating the expression of these genes [27]. Research has shown that there is a certain association between STAT3 and ferroptosis [28], [29], [30]. Furthermore, STAT3 has also been demonstrated to influence tumor occurrence and progression [27], [31], [32], [33].

In this study, we explored the effects of naringenin on ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells. The results indicated that naringenin significantly reduced the viability and clonogenic ability of osteosarcoma cells while inducing the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), excessive expression of malondialdehyde (MDA), and an increase in ferrous ions. Mechanistically, STAT3 binds to the promoter region of MGST2 to promote its transcription, and naringenin induces ferroptosis by inhibiting the expression of STAT3 protein. Furthermore, while promoting ferroptosis, naringenin exhibited a certain degree of biological safety in vivo. Given the potential clinical value of ferroptosis, our findings provide new strategies for the comprehensive treatment of osteosarcoma.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell lines and cell culture

HOS, U2OS, and MG63 are human osteosarcoma cell lines. The cell culture medium used contains 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 90 % proprietary medium, and is maintained in a 5 % CO2 and 37℃ incubator.

2.2. Cytotoxicity assay

Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. Osteosarcoma cells were seeded into 96-well plates (approximately 8000 cells per well) and allowed to adhere for 24 h. After treating the cells with different drugs as required by the experiment, they were incubated for a specified period. Then, 10 µL of enhanced CCK-8 solution and 90 µL of complete culture medium were added to each well. After incubation in the cell culture incubator for 2 h, absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

2.3. Iron assay

For intracellular iron measurement, osteosarcoma cells were inoculated in a 6-well plate and treated with different drugs. The cells were then washed with PBS and incubated with a working solution of FerroOrange at a concentration of 1 μmol/L. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 incubator for 30 min and observed under a fluorescence microscope.

2.4. Reactive oxygen species assay

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection was performed using a ROS assay kit. Osteosarcoma cells were seeded into 24-well plates and treated with different drugs for 24 h. The fluorescent probe DCFH-DA provided in the ROS assay kit was then diluted in serum-free medium at a ratio of 1:1000 and added to the cells. Subsequently, the cells were incubated in a 37 °C incubator for 20 min and washed three times with serum-free cell culture medium to completely remove any DCFH-DA that had not entered the cells. Finally, ROS levels were observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope.

2.5. Malondialdehyde assay

To measure lipid oxidation levels, specifically MDA (malondialdehyde), using the Lipid Oxidation (MDA) Assay Kit, osteosarcoma cells were seeded into 10 cm culture dishes and treated with different drugs for 24 h. Following treatment, cells were collected, homogenized, lysed, and then centrifuged at 10,000–12,000 × g for 10 min to obtain the supernatant. The MDA content was detected using the MDA assay kit. In the cell lysates, MDA reacts with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) to form an MDA-TBA adduct. The absorbance of the adduct was measured at 532 nm using a microplate reader. MDA concentration was determined by comparing the absorbance value to a standard curve.

2.6. Colony formation assay

Seed osteosarcoma cells in 6-well plates (1000 cells per well). After 48 h, once the cells have adhered completely, treat the cells with different stimuli and continue to culture for approximately 14 days. Subsequently, remove the culture medium and wash the cells twice with PBS. Fix the cells with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min, then wash off the excess paraformaldehyde with PBS. Stain the colonies with 0.1 % crystal violet for 30 min, and then capture images to record the results. Quantify the results using ImageJ software.

2.7. Transwell invasion assay

Four hours before the experiment, prepare the matrix gel mixed with serum-free medium at a 1:10 ratio, pre-cooled at 4 °C. Immediately add 50 μL of the prepared matrix gel evenly to the upper chamber. After the gel solidifies,suspend osteosarcoma cells (8 × 10^4 cells per well) in serum-free medium with different treatments, and then seed them onto the upper chamber of a transwell membrane (8 μm pore size, Corning). The lower chamber of the transwell is filled with medium containing 10 % FBS. After 24 h of incubation, use a cotton swab to remove cells from the upper surface of the filter. Fix the cells on the lower surface with 4 % paraformaldehyde and stain them with 0.1 % crystal violet for 15 min. Image and count the migrated cells under a light microscope.

2.8. Transmission electron microscope

Digest, centrifuge, and pellet osteosarcoma cells after different treatments, then collect the cells. Fix them with 3 % glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), followed by 1 % OsO4. After dehydration, prepare 60–80 nm thin sections and stain with uranyl acetate and lead nitrate. Observe under a transmission electron microscope. For each condition, obtain high-resolution digital images from five randomly selected fields.

2.9. Immunofluorescence assay

Seed osteosarcoma cells in a 6-well plate with cover slips and culture until 70 % confluency. After different stimuli, incubate the cells for 24 h. Remove the cover slips, wash gently with PBS three times, fix with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min, and wash with PBS three times. Immerse the cover slips in blocking buffer and seal for 60 min. Remove the cover slips, add primary antibody dilution, and incubate overnight at 4 °C. The next day, gently wash the cover slips with PBS three times, add secondary antibody dilution, and incubate in a 37 °C humid chamber for 60 min. Wash the cover slips with PBS three times, then stain the cell nuclei with DAPI. Observe and photograph the cells under a microscope.

2.10. Reverse transcription and Real-Time quantitative (RT-PCR)Analysis

Extract total RNA from osteosarcoma cells subjected to different treatments using TRIzol reagent. Reverse transcribe the total RNA to cDNA using a reverse transcription kit. Perform quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) using a SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit and the Bio-Rad iQTM5 system.

2.11. Western blot

After scraping and collecting osteosarcoma cells from different treatment groups, add RIPA lysis buffer and PMSF. Perform SDS-PAGE to separate the total protein samples and then transfer them onto a PVDF membrane. Block the membrane with blocking buffer for 30 min and incubate it overnight with the primary antibody at 4 °C. After washing the membrane three times with PBST, incubate it with the secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Finally, wash the membrane three times with PBST and detect protein expression using the ChemiDoc XRS systemwith an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit.

2.12. Cell transfection

When osteosarcoma cells are in the logarithmic growth phase, digest and seed them at 2 × 10^6 cells per well in a 6-well plate. Incubate the cells overnight in a 37 °C, 5 % CO2 incubator. When the cells reach 60–70 % confluency, starve them in serum-free medium for 4–6 h, then transfect the osteosarcoma cells using the transfection reagent Lipo3000, opti-MEM, and plasmids.

2.13. Hematoxylin and Eosin(HE)Staining

Fresh tissue is fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5 μm slices. Stain with hematoxylin for 30 min and eosin for 5 min. Clear with xylene and seal with neutral resin. Observe and photograph the stained sections under an optical microscope at 200 × magnification.

2.14. Immunohistochemistry(IHC)

Fix the isolated tumor tissue in formalin, dehydrate through increasing concentrations of ethanol, embed in paraffin, and section into 4 μm thick slices. After dewaxing and rehydration, incubate the tissue slices in 3 % hydrogen peroxide for 10 min, followed by antigen retrieval using microwaves for 15 min. Block with bovine serum albumin, then incubate the slices with the corresponding primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. Next, incubate with the secondary antibody (1:500) at 37 °C for 30 min. Stain the slices with diaminobenzidine and counterstain with hematoxylin. Finally, observe all tissue slices under an inverted fluorescent microscope.

2.15. Molecular docking

To investigate the interaction between naringenin and the active site of STAT3, molecular docking simulations were performed using the AutoDock online system. The chemical structure of naringenin was obtained from PubChem. The crystal structure of STAT3 was retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank, and PyMOL 2.3.0 software was used to remove water molecules and original ligands. The STAT3 structure was then loaded into AutoDock for hydrogenation, charge assignment, and atom specification. Molecular docking was conducted using AutoDock software, and the docking data were visualized with Discovery Studio.

2.16. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation(ChIP)Assay

After washing the cells with cold PBS containing PMSF, 10 mL of fresh culture medium and 270 μL of 37 % formaldehyde were added. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, followed by the addition of 1.1 mL of 10 × Glycine Solution. The mixture was gently shaken and left at room temperature for 5 min. The liquid in the culture dish was discarded, and the cells were washed with 5 mL of PBS containing a proteinase inhibitor. The cells were scraped, and the sample was disrupted using an ultrasonic device to break the DNA into 400–800 bp fragments. Phenol and chloroform were added and vortexed, followed by agarose gel electrophoresis to analyze the DNA fragmentation. Subsequently, reagents from the kit, including Protein A/G Magnetic Beads/Salmon Sperm DNA, were used for immunoprecipitation. Primary antibody and IgG antibody were added to the experimental and negative control samples, respectively. The samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a rotating mixer. After placing the samples on a magnetic stand for magnetic separation and removing the supernatant, qPCR was performed on the RNA following the previously described method to detect the target gene.

2.17. Dual-Luciferase reporter assay

Seed 293 T cells evenly into a 24-well plate. After 24 h, when the cell density is approximately 50 %-60 %, treat the cells with around 500 μL of Passive Lysis Buffer per well. Incubate at room temperature for 10 min, then centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Transfer 40 μL of the supernatant from each well into a 96-well plate. Next, add 50 μL of Luciferase Assay Reagent II to each well and measure Firefly Luciferase activity at 560 nm using a microplate reader. Then, add 50 μL of Stop & Glo® Reagents to each well and measure Renilla Luciferase activity at 465 nm.

2.18. Agarose gel electrophoresis

Pour the prepared agarose gel solution into the electrophoresis tank and insert the comb. Wait for approximately 20 min for the agarose to solidify. Add 10 μL of DNA sample mixed with the appropriate amount of 6 × Loading Buffer to the wells, and add 7 μL of DNA Marker to the adjacent lanes. Perform electrophoresis at a constant voltage of 140 V until the bromophenol blue dye front is approximately 1 cm from the bottom edge of the gel, then stop the electrophoresis. Use a gel imaging system with a wavelength close to 300 nm and an exposure value of 200–300 for imaging.

2.19. Subcutaneous tumor model

Use MG63 cells to establish a subcutaneous tumor model. Resuspend MG63 cells to a density of 2 × 10^7 cells/mL in serum-free medium and mix with matrix at a 1:1 ratio. Inject 100 μL of the cell suspension subcutaneously into 4-week-old female BALB/c nude mice. When the tumor becomes visible to the naked eye (about one week), randomly divide the mice into three groups (five mice per group) and administer different treatments. Measure tumor size three times a week. Collect blood from the mice's eyes to measure serum levels of alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), creatinine (CRE), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) to assess drug safety. Excise the subcutaneous tumors, weigh, fix, and extract proteins. Remove and fix the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys, and perform HE staining to evaluate potential organ toxicity of the drug.

2.20. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. Data are reported as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Differences between two groups were compared using a two-tailed Student's t-test. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way ANOVA was used. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

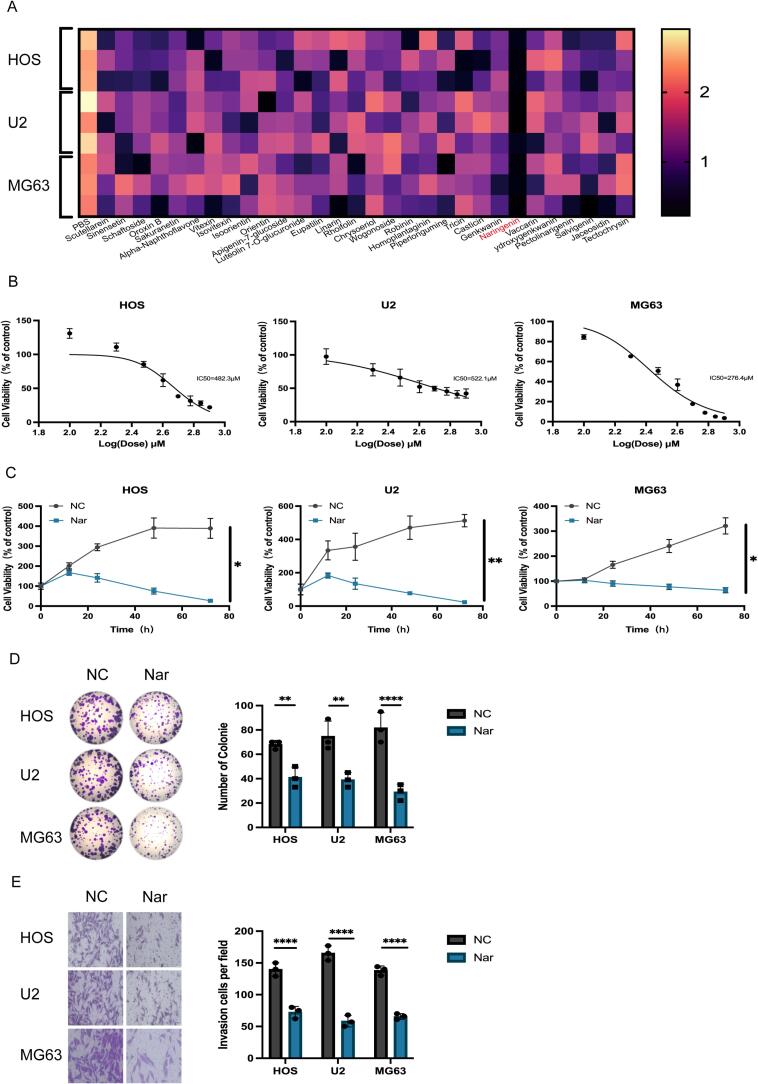

3.1. Naringenin reduces the viability, colony formation, and invasion ability of osteosarcoma cells

Flavonoids have garnered significant attention due to their potential to inhibit tumor cell proliferation. In this study, 30 common flavonoid compounds were screened, and after treating with a uniform concentration of 300 μM for 24 h, cell viability was measured using the CCK-8 assay. The results showed that naringenin significantly inhibited the activity of osteosarcoma cells (Fig. 1A). Additionally, network pharmacology analysis indicated that naringenin exhibits significant target binding capability in osteosarcoma (Fig. S1). The chemical structure of naringenin is shown (Fig. S2).The cell viability of HOS, U2, and MG63 osteosarcoma cells treated with different concentrations (0–800 μM) of naringenin for 24 h was measured using the CCK-8 assay, the results revealed that naringenin significantly inhibited cell growth in a dose-dependent manner, with half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of 482.3 μM, 522.1 μM, and 276.4 μM for HOS, U2, and MG63 cells, respectively (Fig. 1B). Further time gradient experiments(0–72 h) demonstrated that naringenin also inhibited the growth of osteosarcoma cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). Colony formation assays and Transwell invasion assays showed that naringenin significantly suppressed the clonogenic ability (Fig. 1D) and invasion capacity (Fig. 1E) of HOS, U2, and MG63 cells.

Fig. 1.

A: CCK-8 toxicity assay for drug screening. B: CCK-8 assay to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of naringenin in osteosarcoma cell lines. C: CCK-8 assay to assess the time gradient effects of naringenin in osteosarcoma cell lines. (n = 3, **P < 0.01).: Cells were divided into two groups (NC and Nar), and colony formation was observed in each group. (n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). E: Cells were divided into two groups (NC and Nar), and invasion was observed in each group. (n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). S1: Network pharmacology analysis identifying the binding targets of naringenin in osteosarcoma.S2: Chemical structure of naringenin.

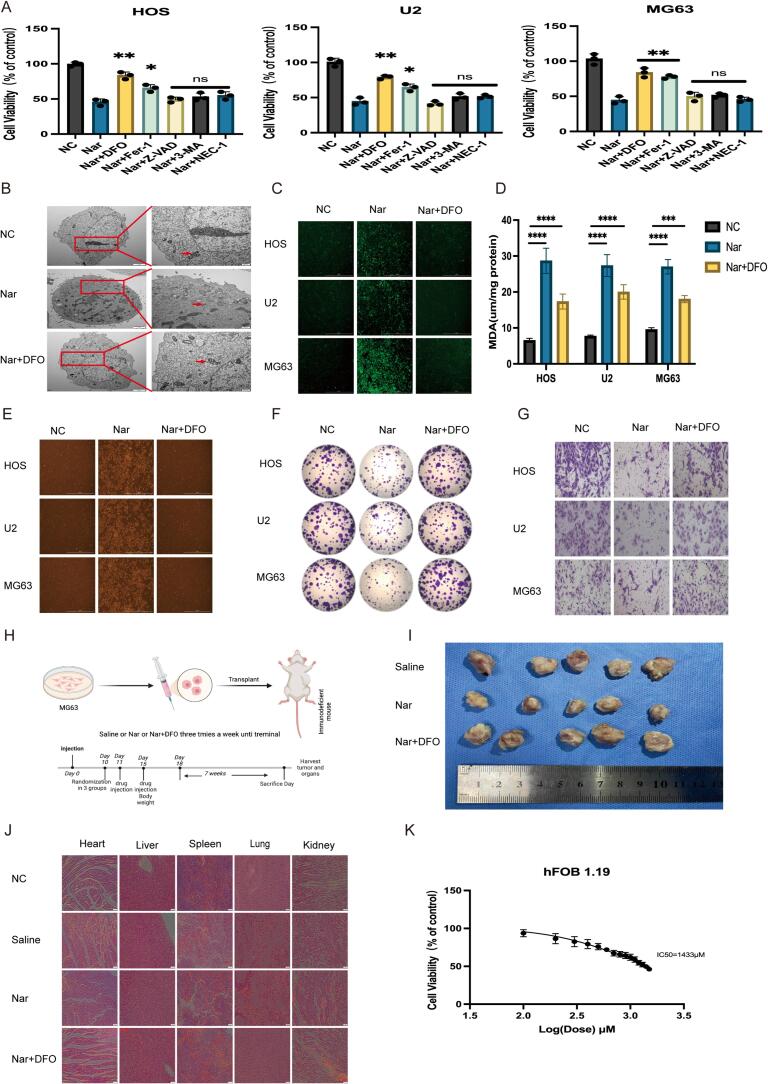

3.2. Naringenin promotes ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells

To investigate the mechanism by which naringenin inhibits the proliferation of osteosarcoma cells, various cell death inhibitors were added alongside naringenin as a control, and the activity of cells in each group was observed. The results showed that the ferroptosis inhibitors DFO and Fer-1 both effectively rescued the activity of osteosarcoma cells, notably, DFO exhibited the strongest rescue effect (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, we attempted to observe the changes in mitochondria associated with ferroptosis after naringenin treatment. We fixed the osteosarcoma cells post-treatment and examined their microstructure using transmission electron microscopy. The results indicated that the volume of mitochondria in the cells treated with naringenin decreased, mitochondrial membrane density increased, and the number of mitochondrial cristae reduced. Importantly, the ferroptosis inhibitor DFO effectively restored the mitochondrial morphology of osteosarcoma cells (Fig. 2B). Based on DFO’s role in rescuing cell vitality and mitochondrial morphology, we speculate that naringenin’s inhibitory effect on osteosarcoma cells is related to ferroptosis. To further explore the specific mechanism by which naringenin induces ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells, we divided the osteosarcoma cell lines into three groups: control group (NC group), naringenin treatment group, and DFO rescue group, and measured the changes in intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Fig. 2C), malondialdehyde (MDA) (Fig. 2D), and ferrous ions (Fe2+) (Fig. 2E). The results showed that the increases in ROS, MDA, and Fe2+ levels induced by naringenin were significantly reversed by DFO. This indicates that naringenin inhibits the proliferation of osteosarcoma through cellular ferroptosis. Further colony formation and Transwell invasion assays demonstrated that the inhibitory effects of naringenin on the colony formation (Fig. 2F, S3) and invasion ability (Fig. 2G, S4) of osteosarcoma cells were also rescued by DFO. To verify the effects of naringenin in vivo, we randomly divided nude mice into three groups (saline group, naringenin group, DFO rescue group) for a tumor-bearing experiment (Fig. 2H). The results indicated that naringenin significantly inhibited the growth of osteosarcoma in vivo (Fig. 2I,S5), and this inhibitory effect could be reversed by DFO. To assess the biosafety of naringenin, we conducted HE staining (Fig. 2J) and biochemical tests (Fig. S6) on the hearts, livers, spleens, lungs, and kidneys of age-matched nude mice without osteosarcoma injection, as well as the aforementioned three groups of nude mice. The results showed no significant differences among the groups. Moreover, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (LC50) of naringenin for normal human osteoblast hFOB 1.19 cells was 1433 μM, which is significantly higher than the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for the three osteosarcoma cell lines (Fig. 2K), indicating that naringenin has good biosafety.

Fig. 2.

A: CCK8 experiment to detect cell viability. B: Transmission electron microscopy to observe the mitochondrial morphological changes in osteosarcoma cells (scale bars: 2 μm and 500 nm). C: Cells were divided into three groups (NC, Nar, and Nar + DFO), and the reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels were observed in each group. D: Cells were divided into three groups (NC, Nar, and Nar + DFO), and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were observed in each group (n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). E: Cells were divided into three groups (NC, Nar, and Nar + DFO), and Fe2+ levels were observed in each group. F, S3: Cells were divided into three groups (NC, Nar, and Nar + DFO), and colony formation was observed in each group(n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). G, S4: Cells were divided into three groups (NC, Nar, and Nar + DFO), and invasion was observed in each group(n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). H: Osteosarcoma cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice. When the tumor diameter reached 2–3 mm, the subcutaneous xenograft model mice were treated with different regimens (saline, 10 mg/kg Nar, and Nar + 10 mg/kg DFO), three times a week until the experiment ended. I: Representative images of the subcutaneous xenograft model mice. J: Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining showing the morphology of the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys of nude mice from different treatment groups (scale bar: 50 μm). K: After 48 h of naringenin (Nar) treatment, the cell viability of hFOB 1.19 cells was measured using the CCK8 method. S3: Size and weight statistics of the osteosarcoma model (n = 5, ***P < 0.001). S4: Liver and kidney function measurements for mice in different groups (n = 5, ns: not significant).

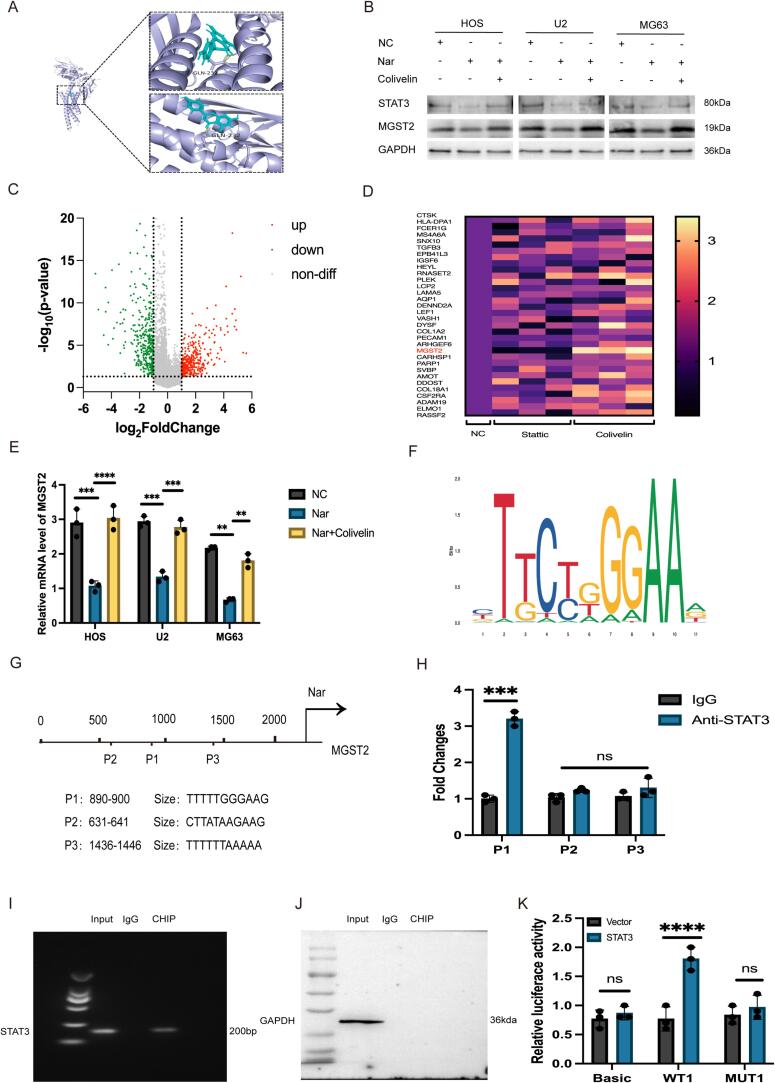

3.3. Naringenin inhibits MGST2 expression through transcriptional regulation via STAT3

STAT3 is an important transcription factor that plays significant roles in immune regulation, stem cell maintenance, and the metastasis of cancer cells. Given the critical role of STAT3 in various diseases, we are focusing on targeted therapeutic strategies against STAT3 to develop new drugs that inhibit its activity. First, molecular docking experiments indicated that hesperetin interacts with a binding site on the STAT3 protein (Fig. 3A, S7). Through Western blot analysis, we verified that hesperetin reduces the expression of STAT3 in osteosarcoma cells, while the STAT3 agonist Colivelin can reverse this effect (Fig. 3B, S8, S9). After screening 32 highly expressed genes from the osteosarcoma gene library (Fig. 3C), we treated osteosarcoma cells with the STAT3 agonist Colivelin and the inhibitor Statiic, and q-PCR analysis revealed that changes in the expression of the MGST2 gene were significantly positively correlated with STAT3 regulation (Fig. 3D). The osteosarcoma cells were divided into control (NC group), hesperetin treatment group, and Colivelin treatment group. The results showed that hesperetin treatment significantly reduced MGST2 expression, and this change could be restored by Colivelin (Fig. 3E, 3B). Therefore, we conclude that hesperetin affects the expression of MGST2 by regulating the STAT3 transcription factor. To further explore how STAT3 regulates the expression of MGST2, we used the JASPAR database to predict the STAT3 binding sites in the MGST2 promoter (Fig. 3F) and identified three potential binding motifs (P1, P2, P3) (Fig. 3G). Subsequently, ChIP-qPCR experiments confirmed the STAT3 binding sites in the MGST2 promoter region, showing that the P1 site is the primary binding site for STAT3, while P2 and P3 are not (Fig. 3H, 3I, 3 J). We further designed wild-type (WT1) and mutant-type (MUT1) luciferase reporter gene plasmids containing the P1 site and transfected them into 293 T cells. The results of luciferase activity assays indicated that STAT3 overexpression significantly increased the activity of the WT1 MGST2 promoter reporter gene, with no significant effect on MUT1 (Fig. 3K).

Fig. 3.

A, S7: Molecular docking experiments predict the binding capability of Nar with STAT3. B: Cells are divided into three groups (NC, Nar, and Nar + Colivelin) to observe the protein expression levels in each group. C: Screening targets from the gene library. D: q-PCR analysis to screen for differentially expressed genes. E: Cells are divided into three groups (NC, Nar, and Nar + Colivelin) to observe the mRNA expression levels in each group (n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). F-G: JASPAR predicts the binding sites of STAT3 and MGST. H-J: ChIP-qPCR validates the binding targets (n = 3, ***P < 0.001).K: Dual-luciferase reporter assay verifies the binding of STAT3 and MGST (n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). S8-9: Relative protein expression(n = 3, ****P < 0.0001).

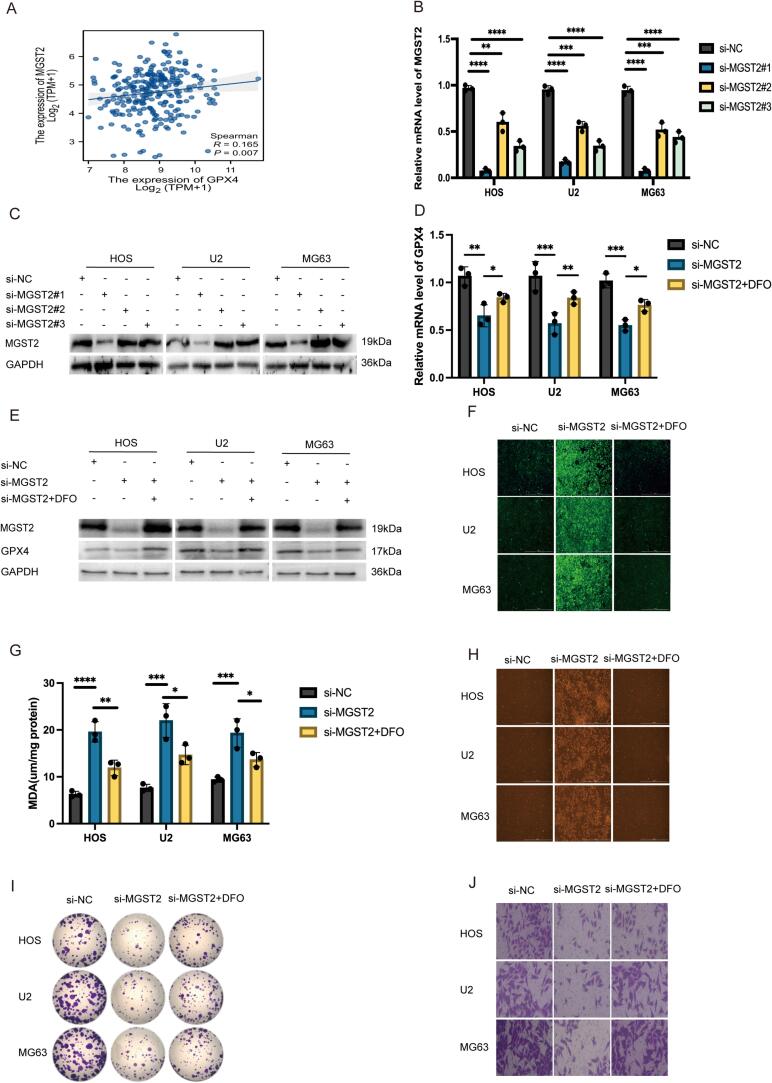

3.4. Silencing MGST2 promotes ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells

Based on bioinformatics analysis, we found a significant positive correlation between MGST2 and GPX4 (Fig. 4A). After validating the transfection efficiency, we selected si-MGST2#1, which had the highest knockdown efficiency, for subsequent experiments (Fig. 4B, 4C, S10). Through q-PCR and Western blot analysis, we discovered that knocking down MGST2 significantly decreased the mRNA and protein expression of GPX4 in osteosarcoma cells, consistent with the bioinformatics predictions. Furthermore, this decrease in expression could be reversed by the ferroptosis inhibitor DFO (Fig. 4D, 4E, S11, S12). We divided the osteosarcoma cells into three groups: the control group (si-NC group), the MGST2 knockdown group (si-MGST2 group), and the DFO rescue group, measuring changes in intracellular ROS (Fig. 4F), MDA (Fig. 4G), and Fe2+ (Fig. 4H). The results showed that the increase in ROS, MDA, and Fe2+ levels caused by MGST2 knockdown was significantly reversed by DFO. Further colony formation assays and Transwell invasion experiments indicated that MGST2 knockdown significantly inhibited the colony formation (Fig. 4I, S13) and invasion abilities (Fig. 4J, S14) of osteosarcoma cells, and this inhibitory effect could be rescued by DFO. These results suggest that MGST2 plays a key role in regulating ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells, and its silencing promotes the ferroptosis process, subsequently inhibiting cell proliferation and invasion.

Fig. 4.

A: Correlation analysis of MGST2 and GPX4 in the database. B-C: Verification of knockdown efficiency of MGST2 (n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). D-E: Dividing cells into three groups (si-NC, si-MGST2, and si-MGST2 + DFO) to observe the mRNA and protein expression levels in each group (n = 3, ***P < 0.001). F: Dividing cells into three groups (si-NC, si-MGST2, and si-MGST2 + DFO) to observe the ROS expression levels in each group. G: Dividing cells into three groups (si-NC, si-MGST2, and si-MGST2 + DFO) to observe the MDA expression levels in each group (n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). H: Dividing cells into three groups (si-NC, si-MGST2, and si-MGST2 + DFO) to observe the Fe2+ expression levels in each group. I, S13: Dividing cells into three groups (si-NC, si-MGST2, and si-MGST2 + DFO) to observe the colony formation status in each group(n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). J, S14: Dividing cells into three groups (si-NC, si-MGST2, and si-MGST2 + DFO) to observe the invasion status in each group(n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). S10-12: Relative protein expression(n = 3, ****P < 0.0001).

3.5. Naringenin promotes ferroptosis in osteosarcoma both in vivo and in vitro via the STAT3-MGST2 pathway

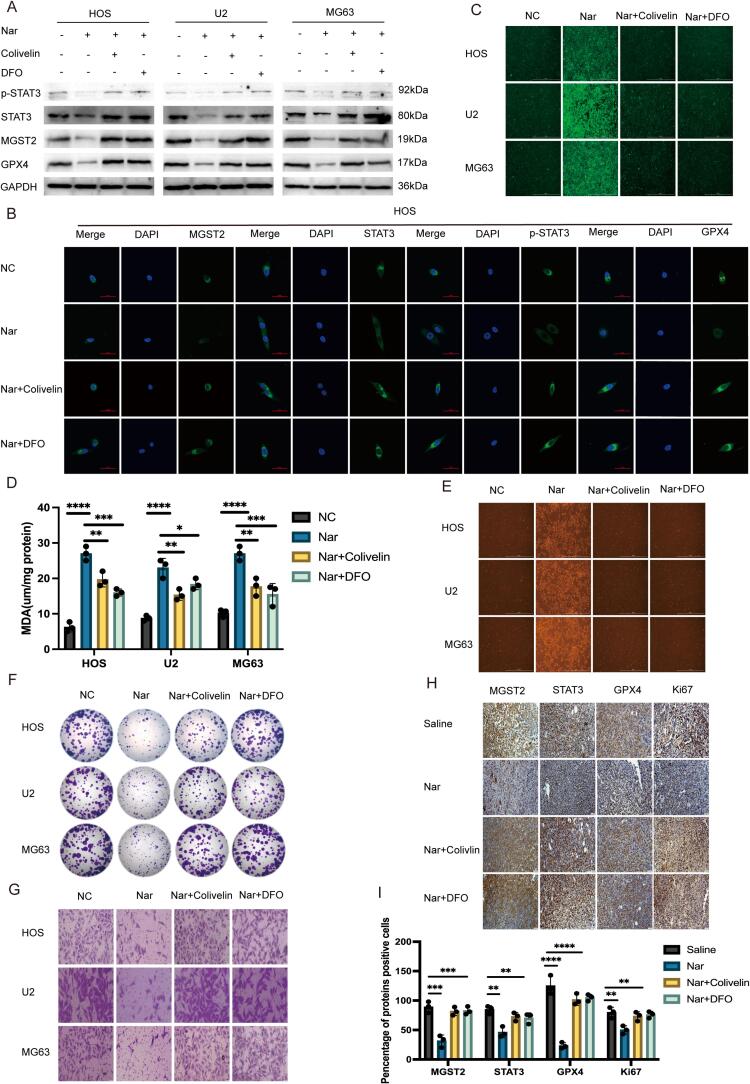

This study divided osteosarcoma cells into four groups: control group (NC group), naringenin treatment group, Colivelin rescue group, and DFO rescue group. Through q-PCR (Fig. S15), Western blot (Fig. 5A, S16-19), and immunofluorescence (Fig. 5B and S20) analyses, we found that naringenin significantly reduced the mRNA and protein expression levels of MGST2, STAT3, phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3), and GPX4 in osteosarcoma cells. However, this reduction effect could be reversed by the STAT3 agonist Colivelin and the ferroptosis inhibitor DFO. In further experiments, we assessed the levels of ROS (Fig. 5C), MDA (Fig. 5D), and Fe2+ (Fig. 5E) in each group of cells. The results showed that the increases in ROS, MDA, and Fe2+ levels caused by naringenin treatment were significantly reversed by Colivelin and DFO. In colony formation assays (Fig. 5F and S21) and Transwell invasion assays (Fig. 5G and S22), naringenin treatment significantly inhibited the colony formation and invasive capacity of osteosarcoma cells, and this inhibitory effect could also be rescued by Colivelin and DFO. In the in vivo experiments, we randomly divided nude mice into four groups (saline group, naringenin group, Colivelin group, and DFO group). Tumor growth results showed that both Colivelin and DFO were able to reverse the inhibitory effect of naringin on osteosarcoma growth (Figs S23, S24). Further immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of tumor tissues revealed that naringin treatment significantly reduced the expression of MGST2, STAT3, GPX4, and the proliferative marker Ki67, while treatment with Colivelin and DFO restored the expression of these genes (Fig. 5H, 5I). In summary, naringenin effectively promotes ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells in vitro and in vivo through the STAT3-MGST2 pathway, and this effect can be reversed by the STAT3 agonist and ferroptosis inhibitors.

Fig. 5.

A: Cells were divided into four groups (NC, Nar, Nar + Colivelin, and Nar + DFO) to observe the protein expression levels in each group. B: Cells were divided into four groups (NC, Nar, Nar + Colivelin, and Nar + DFO) to examine the levels of antigen–antibody expression in each group. C: Cells were categorized into four groups (NC, Nar, Nar + Colivelin, and Nar + DFO) to assess the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in each group. D: Cells were divided into four groups (NC, Nar, Nar + Colivelin, and Nar + DFO) to evaluate the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) in each group (n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). E: Cells were separated into four groups (NC, Nar, Nar + Colivelin, and Nar + DFO) to measure the levels of Fe2+ in each group. F,S21: Cells were organized into four groups (NC, Nar, Nar + Colivelin, and Nar + DFO) to observe colony formation in each group(n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). G,S22: Cells were grouped into four (NC, Nar, Nar + Colivelin, and Nar + DFO) to analyze the invasion capabilities of cells in each group(n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). H-I: Immunohistochemical analysis was conducted on tumor tissues from subcutaneous tumor-bearing nude mice, assessing the expression levels of various indicators (scale bar: 50 μm, n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). S15: Cells were divided into four groups (NC, Nar, Nar + Colivelin, and Nar + DFO) to examine mRNA expression levels in each group (n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). S16-19: Relative protein expression(n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). S20: Cells were classified into four groups (NC, Nar, Nar + Colivelin, and Nar + DFO) to study antigen–antibody expression levels. S23: Representative images of the subcutaneous xenograft model mice. S24: Size and weight statistics of the osteosarcoma model (n = 5, ***P < 0.001). S25: Diagram illustrating the mechanism of action of naringenin.

4. Discussion

Osteosarcoma is a malignant tumor with a high incidence among adolescents, characterized by strong local infiltration and a tendency to metastasize. Although surgery and chemotherapy have significantly improved the prognosis for osteosarcoma patients, the overall prognosis remains unsatisfactory [34]. Surgery is typically the first-line treatment, while chemotherapy is considered to improve the prognosis for patients with localized osteosarcoma. With the application of multi-drug chemotherapy regimens, long-term survival rates can increase to 70 % [35]. However, the effectiveness of chemotherapy for osteosarcoma still faces several challenges, including toxicity to normal tissues, the development of drug resistance, and the rapid clearance of drugs from the body. Although multiple studies have shown that certain drugs can enhance the sensitivity of osteosarcoma to chemotherapy in vitro, their clinical application still requires considerable time [36], [37]. Although progress has been made in the treatment of osteosarcoma, many unresolved issues remain, such as tumor recurrence, drug resistance, and distant metastasis, particularly in patients with advanced or metastatic osteosarcoma, where prognosis is still poor. Therefore, there is an urgent need to conduct in-depth research on the mechanisms of chemoresistance, develop novel adjunctive drugs, explore the potential mechanisms underlying osteosarcoma progression, optimize existing treatment strategies, and implement more precise, individualized therapies to improve patient survival rates and quality of life.

Ferroptosis is a unique form of regulated cell death that is significantly different from other forms of cell death such as apoptosis, autophagy, and necrosis. Its main characteristics include the substantial accumulation of lipid peroxides and reactive oxygen species [12]. The occurrence of ferroptosis is mediated by iron and is associated with distinct morphological changes observed under electron microscopy, such as a decrease in mitochondrial volume, increased membrane density, and a reduction or disappearance of cristae [38], [39]. Studies have shown that inducing ferroptosis can reduce the resistance of tumor cells to chemotherapy drugs to some extent, and its inhibitory effects on the occurrence and progression of osteosarcoma have also been confirmed [40], [41], [42], [43]. Therefore, the mechanisms of ferroptosis can be utilized to address tumor resistance and explore new chemotherapeutic agents, thereby updating existing clinical treatment strategies [44]. Additionally, research on ferroptosis in immune evasion, changes in the tumor microenvironment, and its impact on immunotherapy has provided new perspectives for its potential as a novel strategy in cancer treatment. However, the clinical application of ferroptosis still faces many challenges, such as the precise regulation of iron metabolism and its potential toxicity to normal cells, which require further in-depth research and optimization.

Naringenin has been confirmed to have an inhibitory effect on tumor growth [45], [46], [47], [48], but its specific role in osteosarcoma has not yet been clarified. This study aims to investigate the in vitro and in vivo therapeutic effects of naringenin on osteosarcoma and its underlying mechanisms. In vitro experiments showed that naringenin significantly reduced the viability, clonogenic ability, and invasiveness of osteosarcoma cells. Next, we sought to explore the mechanisms by which naringenin inhibits osteosarcoma cells. Observations using transmission electron microscopy revealed that the morphology of mitochondria in naringenin-treated osteosarcoma cells was similar to that in cells undergoing ferroptosis. The characteristics of ferroptosis include reduced mitochondrial volume, increased membrane density, decreased or absent cristae, and outer membrane rupture. Our study indicates that naringenin treatment leads to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), overexpression of malondialdehyde (MDA), and accumulation of Fe2+ in osteosarcoma cells, all of which can be reversed by the ferroptosis inhibitor DFO. The inhibitory effects of DFO are consistent with previous research findings [49]. Based on these experimental results, we propose that ferroptosis plays a crucial role in naringenin-induced osteosarcoma cell death [50], [51], [52]. Although naringenin has demonstrated significant antitumor activity in experimental models, its efficacy and safety in clinical applications still require further validation. Current research provides a theoretical basis for naringenin as a potential candidate for cancer treatment, but its clinical translation still faces challenges such as bioavailability and optimization of drug delivery systems. With further research, naringenin is expected to become an adjunctive or combination therapy in cancer treatment.

Next, we will investigate the molecular mechanisms by which naringenin induces ferroptosis. Studies have found that naringenin can inhibit the expression of STAT3, thereby reducing the expression of the downstream gene MGST2. We confirmed that STAT3 can bind to the promoter region of MGST2, promoting its transcription. However, further exploration is needed to validate the mutations at other binding sites. Naringenin prevents the expression of MGST2 by regulating STAT3 and its phosphorylation status, but the specific regulatory mechanisms of phosphorylation still require in-depth study. GPX4, as an important regulator of ferroptosis, can convert lipid hydroperoxides into non-toxic lipid alcohols, thereby preventing ferroptosis. Our experiments show that silencing MGST2 leads to a significant decrease in GPX4 levels in osteosarcoma cells, accompanied by a series of ferroptosis-related changes. Finally, through in vivo experiments, we observed that naringenin effectively slowed the growth of subcutaneously transplanted tumors with minimal damage to other cells and tissues, demonstrating good biosafety and laying a theoretical foundation for its clinical application. It is worth noting that although subcutaneous xenograft models offer high operability and reliability, they still have certain limitations. These models cannot fully replicate the appropriate tumor microenvironment, and the location of tumor growth may affect its biological characteristics, including tumor size, metastatic potential, and chemotherapy sensitivity. Therefore, to obtain more clinically relevant and translatable research results, this study still requires the integration of multiple animal models and techniques to comprehensively evaluate the biological characteristics and therapeutic effects of osteosarcoma.

5. Conclusions

This study found that naringenin is an effective anti-osteosarcoma drug. It induces ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells by inhibiting the STAT3-MGST2 signaling pathway (Fig. S25). Therefore, this compound may represent an emerging and promising approach for the treatment of osteosarcoma.

6. Patents

Author Contributions: Y.L. conducted in vitro and in vivo experiments and analyzed the results. X.B. guided this experiment, and reviewed and corrected this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Li Yingang and Bai Xizhuang promised that this research has been conducted in accordance with international, national, and institutional regulations, while also considering the rights of animals in research and biodiversity.The cell lines used in this study were obtained from a public cell bank (ATCC), and their use complies with the ethical review requirements of the institution.This study involves experiments on animals, and all procedures have been approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University (Ethics No.: CMU2023949), with approval date: September 2023. The experimental procedures comply with the Regulations for the Administration of Experimental Animals and the 3Rs principle.

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yingang Li: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Xizhuang Bai: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thankWC Zhang from Liaoning Provincial Cancer Hospital andP Wu from Shengjing Hospital Affiliated to China Medical University for their continuous encouragement and support. I also want to express my gratitude to the teachers in the Infection Immunology and Metabolism research group at the Academy of Military Sciences for their guidance and assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbo.2024.100657.

Contributor Information

Yingang Li, Email: liyingang98@163.com.

Xizhuang Bai, Email: xizhuang_bai2021@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Damron T.A., Ward W.G., Stewart A. Osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing's sarcoma: national cancer data base report. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2007;459:40–47. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318059b8c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar R., Kumar M., Malhotra K., et al. Primary osteosarcoma in the elderly revisited: current concepts in diagnosis and treatment. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2018;20(2):13. doi: 10.1007/s11912-018-0658-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sajadi K.R., Heck R.K., Neel M.D., et al. The incidence and prognosis of osteosarcoma skip metastases. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2004;426:92–96. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000141493.52166.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang X., Zhao J., Bai J., et al. Risk and clinicopathological features of osteosarcoma metastasis to the lung: a population-based study. J Bone Oncol. 2019;16 doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2019.100230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaste S.C., Pratt C.B., Cain A.M., et al. Metastases detected at the time of diagnosis of primary pediatric extremity osteosarcoma at diagnosis. Cancer. 1999;86(8):1602–1608. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991015)86:8<1602::aid-cncr31>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu C.C., Livingston J.A. Genomics and the Immune Landscape of Osteosarcoma. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020;1258:21–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-43085-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bystrom L.M., Guzman M.L., Rivella S. Iron and reactive oxygen species: friends or foes of cancer cells? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20(12):1917–1924. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang X., Stockwell B.R., Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;22(4):266–282. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul B.T., Manz D.H., Torti F.M., et al. Mitochondria and Iron: current questions. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2017;10(1):65–79. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2016.1268047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muckenthaler M.U., Rivella S., Hentze M.W., et al. A Red Carpet for Iron Metabolism. Cell. 2017;168(3):344–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J., Cao F., Yin H.L., et al. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(2):88. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2298-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon S.J., Lemberg K.M., Lamprecht M.R., et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koppula P., Zhuang L., Gan B. Cystine transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: ferroptosis, nutrient dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein Cell. 2021;12(8):599–620. doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00789-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gan B. DUBbing Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2019;79(8):1749–1750. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang C., Zhang X., Yang M., et al. Recent Progress in Ferroptosis Inducers for Cancer Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2019;31(51):e1904197. doi: 10.1002/adma.201904197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockwell B.R., Jiang X. A Physiological Function for Ferroptosis in Tumor Suppression by the Immune System. Cell Metab. 2019;30(1):14–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhia M., Motallebi M., Abadi B., et al. Naringenin Nano-Delivery Systems and Their Therapeutic Applications. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(2) doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13020291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arafah A., Rehman M.U., Mir T.M., et al. Multi-Therapeutic Potential of Naringenin (4',5,7-Trihydroxyflavonone): Experimental Evidence and Mechanisms. Plants (basel) 2020;9(12) doi: 10.3390/plants9121784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frydoonfar H.R., Mcgrath D.R., Spigelman A.D. The variable effect on proliferation of a colon cancer cell line by the citrus fruit flavonoid Naringenin. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5(2):149–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L., Xu X., Jiang T., et al. Citrus aurantium Naringenin Prevents Osteosarcoma Progression and Recurrence in the Patients Who Underwent Osteosarcoma Surgery by Improving Antioxidant Capability. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018;2018:8713263. doi: 10.1155/2018/8713263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee C.W., Huang C.C., Chi M.C., et al. Naringenin Induces ROS-Mediated ER Stress, Autophagy, and Apoptosis in Human Osteosarcoma Cell Lines. Molecules. 2022;27(2) doi: 10.3390/molecules27020373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Todoric J., Antonucci L., Karin M. Targeting Inflammation in Cancer Prevention and Therapy. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 2016;9(12):895–905. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thulasingam M., Orellana L., Nji E., et al. Crystal structures of human MGST2 reveal synchronized conformational changes regulating catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):1728. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21924-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song J.I., Grandis J.R. STAT signaling in head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19(21):2489–2495. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mora L.B., Buettner R., Seigne J., et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 in human prostate tumors and cell lines: direct inhibition of Stat3 signaling induces apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62(22):6659–6666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke W.M., Jin X., Lin H.J., et al. Inhibition of constitutively active Stat3 suppresses growth of human ovarian and breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2001;20(55):7925–7934. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouyang S., Li H., Lou L., et al. Inhibition of STAT3-ferroptosis negative regulatory axis suppresses tumor growth and alleviates chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Redox Biol. 2022;52 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y., Liao S., Bennett S., et al. STAT3 and its targeting inhibitors in osteosarcoma. Cell Prolif. 2021;54(2):e12974. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai N., Zhou W., Ye L.L., et al. The STAT3 inhibitor pimozide impedes cell proliferation and induces ROS generation in human osteosarcoma by suppressing catalase expression. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017;9(8):3853–3866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuo D., Zhou Z., Wang H., et al. Alternol, a natural compound, exerts an anti-tumour effect on osteosarcoma by modulating of STAT3 and ROS/MAPK signalling pathways. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2017;21(2):208–221. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo Y., Gao X., Zou L., et al. Bavachin Induces Ferroptosis through the STAT3/P53/SLC7A11 Axis in Osteosarcoma Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021:1783485. doi: 10.1155/2021/1783485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao L., Ma X., Ye L., et al. IL-9/STAT3/fatty acid oxidation-mediated lipid peroxidation contributes to Tc9 cell longevity and enhanced antitumor activity. J. Clin. Invest. 2022;132(7) doi: 10.1172/JCI153247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang C.Y., Chen L.J., Chen G., et al. SHP-1/STAT3-Signaling-Axis-Regulated Coupling between BECN1 and SLC7A11 Contributes to Sorafenib-Induced Ferroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(19) doi: 10.3390/ijms231911092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C., Xie L., Ren T., et al. Immunotherapy for osteosarcoma: Fundamental mechanism, rationale, and recent breakthroughs. Cancer Lett. 2021;500:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miwa S., Shirai T., Yamamoto N., et al. Current and Emerging Targets in Immunotherapy for Osteosarcoma. J. Oncol. 2019;2019:7035045. doi: 10.1155/2019/7035045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hattinger C.M., Tavanti E., Fanelli M., et al. Pharmacogenomics of genes involved in antifolate drug response and toxicity in osteosarcoma. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2017;13(3):245–257. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2017.1246532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luetke A., Meyers P.A., Lewis I., et al. Osteosarcoma treatment - where do we stand? A state of the art review. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2014;40(4):523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stockwell B.R., Jiang X., Gu W. Emerging Mechanisms and Disease Relevance of Ferroptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2020;30(6):478–490. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y., Zeng X., Lu D., et al. Erastin induces ferroptosis via ferroportin-mediated iron accumulation in endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2021;36(4):951–964. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin H., Chen X., Zhang C., et al. EF24 induces ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells through HMOX1. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;136 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lv H., Zhen C., Liu J., et al. beta-Phenethyl Isothiocyanate Induces Cell Death in Human Osteosarcoma through Altering Iron Metabolism, Disturbing the Redox Balance, and Activating the MAPK Signaling Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020;2020:5021983. doi: 10.1155/2020/5021983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lv H.H., Zhen C.X., Liu J.Y., et al. PEITC triggers multiple forms of cell death by GSH-iron-ROS regulation in K7M2 murine osteosarcoma cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020;41(8):1119–1132. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0376-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Q., Wang K. The induction of ferroptosis by impairing STAT3/Nrf2/GPx4 signaling enhances the sensitivity of osteosarcoma cells to cisplatin. Cell Biol. Int. 2019;43(11):1245–1256. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X., Du S., Wang S., et al. Ferroptosis in osteosarcoma: A promising future. Front. Oncol. 2022;12:1031779. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1031779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Motallebi M., Bhia M., Rajani H.F., et al. Naringenin: A potential flavonoid phytochemical for cancer therapy. Life Sci. 2022;305 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slika H., Mansour H., Wehbe N., et al. Therapeutic potential of flavonoids in cancer: ROS-mediated mechanisms. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022;146 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J., Wang N., Zheng Y., et al. Naringenin in Si-Ni-San formula inhibits chronic psychological stress-induced breast cancer growth and metastasis by modulating estrogen metabolism through FXR/EST pathway. J. Adv. Res. 2023;47:189–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2022.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang T.-M., Chi M.-C., Chiang Y.-C., et al. Promotion of ROS-mediated apoptosis, G2/M arrest, and autophagy by naringenin in non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024;20(3):1093–1109. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.85443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rauf A., Shariati M.A., Imran M., et al. Comprehensive review on naringenin and naringin polyphenols as a potent anticancer agent. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022;29(21):31025–31041. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-18754-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wen R.J., Dong X., Zhuang H.W., et al. Baicalin induces ferroptosis in osteosarcomas through a novel Nrf2/xCT/GPX4 regulatory axis. Phytomedicine. 2023;116 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan C., Fan R., Zhu K., et al. Curcumin induces ferroptosis and apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells by regulating Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2023;248(23):2183–2197. doi: 10.1177/15353702231220670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.He T., Lin X., Yang C., et al. Theaflavin-3,3'-Digallate Plays a ROS-Mediated Dual Role in Ferroptosis and Apoptosis via the MAPK Pathway in Human Osteosarcoma Cell Lines and Xenografts. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022;2022:8966368. doi: 10.1155/2022/8966368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.