Abstract

Phytoene synthase from the bacterium Erwinia uredovora (crtB) has been overexpressed in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv. Ailsa Craig). Fruit-specific expression was achieved by using the tomato polygalacturonase promoter, and the CRTB protein was targeted to the chromoplast by the tomato phytoene synthase-1 transit sequence. Total fruit carotenoids of primary transformants (T0) were 2–4-fold higher than the controls, whereas phytoene, lycopene, β-carotene, and lutein levels were increased 2.4-, 1.8-, and 2.2-fold, respectively. The biosynthetically related isoprenoids, tocopherols plastoquinone and ubiquinone, were unaffected by changes in carotenoid levels. The progeny (T1 and T2 generations) inherited both the transgene and phenotype. Determination of enzyme activity and Western blot analysis revealed that the CRTB protein was plastid-located and catalytically active, with 5–10-fold elevations in total phytoene synthase activity. Metabolic control analysis suggests that the presence of an additional phytoene synthase reduces the regulatory effect of this step over the carotenoid pathway. The activities of other enzymes in the pathway (isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase, geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase, and incorporation of isopentenyl diphosphate into phytoene) were not significantly altered by the presence of the bacterial phytoene synthase.

Keywords: carotenoids‖metabolic engineering

Fruits and vegetables contain an array of phytochemicals that contribute to good health and are often termed “functional foods” (1). Epidemiological and human supplementation studies suggest that carotenoids such as lycopene and β-carotene (pro-vitamin A) reduce the onset of chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease (2), certain cancers (e.g., prostate) (3), and age-related macular degeneration (4). Tomato fruit and its processed products are the principal dietary sources of lycopene and are also useful for their β-carotene contents. Therefore, the elevation of carotenoid biosynthesis in plants, especially the tomato, by genetic manipulation should increase the lycopene and β-carotene levels and hence improve the nutritional quality of the crop.

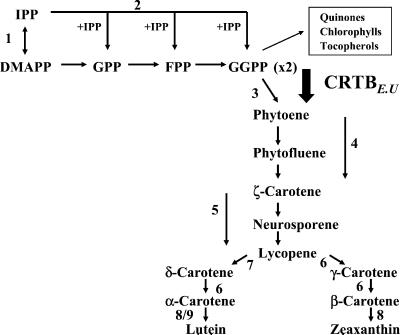

Carotenoids in plants are isoprenoids formed via the mevalonate-independent pathway (5), which is responsible for isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) synthesis in the plastid. Geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP), derived from the ubiquitous isoprenoid pathway, is the precursor of carotenoids as well as tocopherols and phylloquinone (Fig. 1). The conversion of GGPP to phytoene is the first committed step in carotenoid biosynthesis, catalyzed by the enzyme phytoene synthase (Fig. 1). The next two enzymes (phytoene and ζ-carotene desaturases) desaturate phytoene and ζ-carotene, respectively. The product of ζ-carotene desaturase is lycopene, which is responsible for the characteristic red color of ripe tomato fruit. It can undergo cyclization to either β- or α-carotenes followed by hydroxylation to yield xanthophylls such as lutein.

Figure 1.

Summary of carotenoid biosynthesis. The enzymes are numbered 1, IPP isomerase; 2, GGPP; 3, crtB; 4, phytoene desaturase; 5, ζ-carotene desaturase; 6, lycopene β-cyclase; 7, lycopene ɛ-cyclase; 8, β-carotene hydroxylase; and 9, ɛ-hydroxylase. DMAPP, dimethylallyl diphosphate; GPP, geranyl diphosphate; FPP, farnesyl diphosphate; CRTB, crtB from E. uredovora.

Lycopene accumulation arises during tomato fruit ripening as a consequence of reduced lycopene cyclization (6, 7) and the presence of a ripening enhanced phytoene synthase 1 (PSY-1) (6, 8). We have shown that the constitutive expression of Psy-1 in transgenic tomato resulted in a number of pleiotrophic effects (9), including dwarfism caused by the diversion of GGPP from gibberellin formation (10). Most recently, the elevation of β-carotene content in tomato fruit has been achieved by the constitutive expression of phytoene desaturase from the bacterium Erwinia uredovora (crtI) (11) and lycopene cyclase (crtL-β) from Arabidopsis thaliana (12). Several examples of other genetic manipulations of carotenogenesis in plants have been reported. For example, in rice endosperm, low levels of β-carotene have been produced by concurrent expression of the Narcissus pseudonarcissus phytoene synthase, Escherichia uredovora crtI and N. pseudonarcissus lycopene β-cyclase (13). The most dramatic (50-fold increase) of carotenoid synthesis has been achieved in Brassica napus by the seed-specific expression of the E. uredovora phytoene synthase (crtB) (14).

The present article describes the elevation of lycopene in tomato fruit by the genetic manipulation of carotenoid biosynthesis using the fruit-specific expression of a bacterial phytoene synthase (crtB from E. uredovora). Characterization of the transgenic plants has evaluated the consequences of such an approach on the elevation of carotenoids.

Materials and Methods

Plants and Bacteria.

Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv. Ailsa Craig was the wild-type tomato line used. Plants were grown in the glasshouse under supplementary lighting. Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA 4404 was used for transformation.

Transformation of Tomato Plants and A. tumefaciens.

A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of tomato stem explants was carried out as described (15), using kanamycin resistance as a selection marker.

Construction of Transformation Vector.

The crtB gene (16) and Psy-1 modified transit sequence (ts) (17) were amplified by PCR. PCR products (crtB and ts-Psy-1) were Klenow-treated and gel-purified. The chimeric gene was then produced by PCR, using ts-Psy-1 and crtB as templates. The primers used were ts-Psy-1, 5′-TCG GAT CCA ATG AGC GTG GCA CTT-3′ and crtB, 3′-AGACA GGATCCTAGAGAGCGG GCG CCA GAG ATG-5′. The resulting product was cloned directly into the TA cloning vector pCRII (Invitrogen). The ts-Psy-1-crtB chimeric gene was removed from pCRII by BamHI digestion and cloned into the dephosphorylated BamHI site of the binary vector pRN2 [a pBIN derivative containing the polygalacturonase (PG) promoter] as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Structure of the pRN2 construct containing E. uredovora crtB. PG-5′, PG promoter; chromoplast transit sequence (CTS) modified from the L. esculentum Psy-1; crtBE.U, crtB from E. uredovora; and PG-3′, PG terminator.

Molecular Analysis.

PCR analysis was carried out by using DNA extracted from leaf material (200 mg) as described (11). DNA for Southern blotting was extracted in accordance with the nuclei lysis hexadecyl trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) extraction method (18). Genomic DNA (20–30 μg) was digested with EcoRI or HindIII, fragments were separated on 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose gels, then blotted onto membranes and hybridized at 65°C overnight. Blots were probed with a PCR-derived nptII fragment. Northern blot analysis was performed according to ref. 19. Blots were hybridized with dCTP-labeled gene fragments, crtB BamHI fragments from pRN2, the 1.6-kb pTOM5 cDNA (20), the 1.3-kb EcoRI fragment of phytoene desaturase (Pds) cDNA (21), and GGPP synthase as detailed (22). Analysis of gene expression by reverse transcription–PCR was carried out as described (23). The oligonucleotides for amplification of crtB and the exogenous control (rat transthyretin) were 5′-GATGCTCTACGCCTGGTG-3′ (upstream) and 5′-CGATTGCCCAGGCGGAAC-3′ (downstream), and 5′-AGTCCTGGATGCTGTCCGAG-3′ (upstream) and 5′-CATGGAATGGGGAAATGCCAAG-3′ (downstream), respectively.

Preparation of Subcellular Fractions from Tomato Fruit.

Crude plastid fractions were prepared in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0) containing 0.4 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT as described (6). Typically, pericarp tissue from 3 to 4 ripening tomatoes was used.

Preparation of Protein Extracts for SDS/PAGE.

Proteins were extracted from lyophilized tissue (10 mg) with 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) in 80% (vol/vol) acetone containing 1 mM DTT (5 vol). After a 30-min incubation at −20°C the precipitate was pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 80% (vol/vol) acetone containing 1 mM DTT at −20°C for a further 30 min. The pelleted material was resuspended in SDS/PAGE sample buffer (24) containing DTT. Samples for SDS/PAGE were prepared from subcellular samples by first precipitating proteins using the method described in ref. 25.

Immunodetection by Western Blot Analysis.

Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE (24) on a 12.5% gel electrophoresed for 1.5 h at a constant current of 30 mA. Proteins were transferred onto poly(vinylidene difluoride) (PVDF) membranes, and immunodetection of CRTB was carried out as described (6). Molecular weights were determined by comparison with colored standards (14–200 kDa; Amersham Pharmacia).

Extraction, Analysis, and Determination Isoprenoids.

The method used to analyze and quantify carotenoids and isoprenoids is detailed in ref. 26. Typically, 2–3 fruit per plant were cut in half, seeds were removed, and tissue was frozen completely at −80°C for at least 3 h. The lyophilized tissue (100 mg) was biscuit dry and became a fine powder when ground in a mortar and pestle. HPLC separations were performed on a C30 reverse-phase column (250 × 4.6 mm) purchased from YMC, Wilmington, NC. The mobile phases used were methanol (A), water/methanol (20/80 by vol) containing 0.2% ammonium acetate (B), and tert-methyl butyl ether (C). The gradient used was 95% A/5% B isocratically for 12 min, a step to 80% A/5% B/15% C at 12 min, followed by a linear gradient to 30% A/5% B/65% C by 30 min.

Enzyme Assays.

Enzyme activities were determined as described (26). In brief, incubations were buffered with 0.4 M Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0) containing 1 mM DTT, 4 mM MgCl2, 6 mM MnCl2, 3 mM ATP, 0.1% (wt/vol) Tween 60, 1 mM potassium fluoride, and the substrate in a total volume of 150 μl. The substrates used were 0.5μCi [1-14C]IPP [56 mCi/mmol, purchased from Amersham plc (Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, U.K.) for the determination of IPP isomerase activity], [1-14C]IPP (0.5μC), and 2 mM dimethylallyl diphosphate for GGPP synthase and [3H]GGPP (15 mCi/mmol, American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis) for phytoene synthase. Extracts (200 μl) were mixed with the cofactor-containing buffer. IPP isomerase assays were carried out for 1 h at 28°C. After incubation, methanol (200 μl) was added, and acid hydrolysis was performed by treatment with conc. HCl (25% final vol) for 1 h at 37°C. The prenyl alcohol derivatives were then extracted with diethyl ether (500 μl × 2). An aliquot of the hyperphase was removed, and the radioactivity present was determined by liquid scintillation counting. To determine incorporation of [14C]IPP into prenyl phosphates and phytoene modifications were necessary. First, incubations were performed for at least 5 h. Nonpolar radiolabeled reaction products (including phytoene) were extracted from incubation mixtures by partitioning with chloroform (500 μl × 2). The remaining aqueous phase was then subjected to acid hydrolysis, and prenyl alcohol derivatives were extracted as described previously. The radiolabeled prenyl derivatives and phytoene formed during the incubations were separated by using the procedures described in ref. 27, with the exception that prenyl alcohols were routinely separated on reverse-phase silica TLC plates developed in methanol/dH2O (95:5). The Rf values for dimethylallyl alcohol (DMA-OH), geranyl alcohol (G-OH), farnesol (F-OH), and geranylgeranyl alcohol (GG-OH) were 0.15, 0.3, 0.42, and 0.64, respectively. GGPP synthase assays and analysis of radiolabeled products formed were carried out as described for IPP isomerase. Phytoene synthase assays were performed in a similar manner to IPP isomerase, and GGPP synthase was performed as detailed in ref. 27. Phytoene was identified by co-chromatography with authentic standards (28). Phytoene desaturase and lycopene cyclase was assayed as described (6).

Other Determinations.

Protein levels were estimated as described (29), after precipitation (25). Determination of radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting was carried out according to ref. 30. Reverse transcription–PCR products were quantified as band intensities by using the Ultraviolet Products gel documentation system grab-it (Cambridge, U.K.).

Metabolic Control Analysis.

Flux control coefficients (CJi/Ei) were calculated as described (31, 32), the latter being especially applicable to transgenic plants. The deviation index (D) for the change in metabolic flux in response to a change in phytoene synthase activity was calculated as D = (δJ/δX) × Xr/Jr, where δJ = Jr − Jo and δX = Xr − Xo in which Xo and Xr are total carotenoid concentrations in wild-type and transgenic lines, respectively, and Jo and Jr are the corresponding metabolic fluxes (33).

Results

Genetic Analysis of crtB Transformants.

After selection on the basis of kanamycin resistance, 27 transgenic plants were regenerated. Southern blot analysis, using the nptII gene, indicated that 51% of the plants contained a single insert, whereas 26% and 22% possessed two or more inserts, respectively. Based on visual observations, the growth and development of the crtB transgenic plants was virtually identical to the wild type, although in some cases increased pigmentation within the internal fruit tissue was observed. Some 33% of the plants yielded fruit that contained up to 50% more carotenoid, 38% showed no change (±8% of the control), whereas in 29% of the population the carotenoid content was lower (<10–30% of the control). Three single-insert crtB homozygous plants showing a range of increased pigmentation (designated B-1, B-3, and B-4) were generated based on kanamycin germination and Southern blot analysis.

crtB Gene Expression and Immunodetection of CRTB Protein.

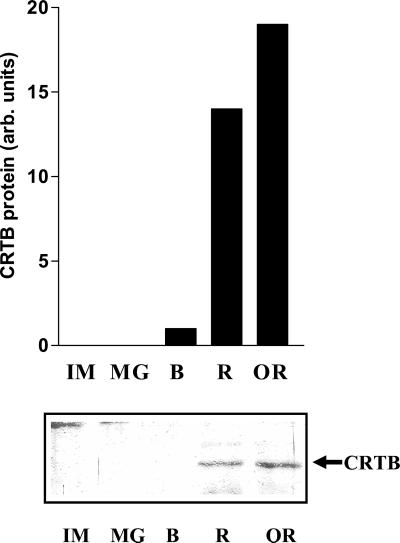

Neither the crtB transcript nor the CRTB protein was detectable in flower, leaf, or stem tissue (data not shown). During fruit development and ripening, crtB transcripts were first observed at the mature green stage, increasing 2.5-fold at the breaker stage, and then decreasing by 40% in ripe [5–8 days post breaker (dpb)] fruit. crtB transcripts could not be detected in overripe (18–20 dpb) fruit. CRTB protein was not detectable in immature and mature green fruit. At the onset of ripening, the CRTB protein was detected at very low levels, and as ripening proceeded, CRTB protein levels increased 9- and 12-fold in ripe and overripe fruit, respectively (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Production of CRTB protein during fruit development and ripening. IM, immature green; MG, mature green; B, breaker; R, ripe; OR, overripe. The crtB line used was B3–15 (T1, second generation). Ten micrograms of protein per sample was applied. The molecular weight of CRTB was 35 kDa.

Analysis of the Carotenoids and Isoprenoids.

The profile of isoprenoids present in ripe fruit from the T0 crtB transgenic lines was identical to the wild type (26). No novel isoprenoids were found.

Studies were performed to determine the inter- and intraplant variation in fruit carotenoids. From three genetically identical plants, six ripe (7 dpb) fruit per plant were sampled. The variation in the total carotenoid content between fruit was 9 ± 3% (n = 18) and individual carotenoids 10 ± 4.5% (n = 18). The carotenoid composition of crtB transgenic and wild-type leaf tissue and fruit were determined at the mature, breaker, ripe, and overripe fruit stages. No significant differences were found in mature green and breaker fruit or leaf tissue. Ripe crtB fruit, however, showed increases in phytoene, lycopene, β-carotene, and total carotenoids (Table 1).

Table 1.

Carotenoid content of ripe tomato fruit from selected lines transformed with the E. uredovora phytoene synthase crtB gene

| Plant | Fruit, dpb | Zygosity | Carotenoid content, μg/g of dry weight

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phytoene | Lycopene | β-Carotene | Total* | |||

| Primaries (T0) | ||||||

| Control | 14 | 52 ± 12 | 2436 ± 650 | 270 ± 27 | 2776 ± 697 | |

| B-1 | 14 | — | 88 ± 4 | 2558 ± 183 | 450 ± 23 | 3173 ± 198 |

| B-2 | 14 | — | 82 ± 3 | 4176 ± 87 | 315 ± 22 | 4561 ± 428 |

| B-3 | 14 | — | 148 ± 2 | 4350 ± 522 | 630 ± 11 | 5155 ± 892 |

| B-4 | 14 | — | 168 ± 2 | 5220 ± 174 | 563 ± 23 | 5949 ± 297 |

| B-5 | 14 | — | 108 ± 5 | 4385 ± 286 | 743 ± 34 | 6048 ± 595 |

| B3 progeny (T1) | ||||||

| Wild type | 16 | — | 37 ± 4 | 2480 ± 750 | 330 ± 40 | 2857 ± 797 |

| Control | 16 | Az | 34 ± 3 | 2834 ± 797 | 165 ± 80 | 2860 ± 613 |

| B3-15 | 16 | H | 71 ± 8 | 4340 ± 177 | 605 ± 138 | 4694 ± 306 |

| B3-17 | 16 | H | 43 ± 2 | 5137 ± 89 | 825 ± 55 | 5918 ± 102 |

| B3-18 | 16 | H | 56 ± 25 | 4604 ± 531 | 110 ± 27 | 4694 ± 816 |

| B4 and B1 Progeny (T1) | ||||||

| Control | 7 | Az | 21 ± 2 | 562 ± 15 | 173 ± 20 | 807 ± 45 |

| B4-19 | 7 | H | 34 ± 13 | 562 ± 100 | 231 ± 29 | 922 ± 144 |

| B1-6 | 7 | H | 29 ± 3 | 522 ± 20 | 346 ± 7 | 922 ± 12 |

| B4-6 | 7 | H | 34 ± 1 | 682 ± 20 | 375 ± 29 | 1153 ± 29 |

| B4-3 | 7 | H | 42 ± 1 | 1265 ± 221 | 346 ± 29 | 1729 ± 144 |

| B3 progeny (T2) | ||||||

| Wild type | 14 | 28 ± 8 | 1238 ± 463 | 33 ± 5 | 1332 ± 489 | |

| Control | 14 | Az | 28 ± 1 | 1333 ± 143 | 34 ± 6 | 1434 ± 102 |

| B3-15 | 14 | H | 47 ± 13 | 2000 ± 214 | 170 ± 30 | 2357 ± 168 |

Analysis of primary transformants was on two fruit per plant in triplicate. T1 values are the mean of triplicate determinations made on two fruit per plant. Data for the T2 generation represent three plants, two fruit per plant determined in triplicate. The wild type is from two plants, two fruit per plant, analyzed in triplicate. The azygous T2 control represents determinations on three plants, six fruit per plant. All values are quoted ± SE.

Includes minor carotenoids.

The phytoene content of the crtB transgenic lines showed the greatest increase (1.6–3.1-fold) above wild type (Table 1). Besides phytoene, lycopene and β-carotene were also increased 1.8–2.1-fold and 1.6–2.7-fold, respectively, compared with the wild type (Table 1). The lutein content was unchanged with the exception of 3 lines (B-3, B-4, and B-5), which also possessed the greatest increases in total carotenoids. Typically, lutein levels in these lines were increased 1.6-fold. Less abundant tomato carotenoids such as phytofluene and ζ-carotene content were elevated 2.5- and 1.6-fold, respectively, in most of the crtB transgenics. Typically, the qualitative composition of carotenoids in the transgenic fruit was very similar to that found in wild-type ripe fruit. For example, the proportion of lycopene in crtB lines and wild type was 86 ± 4% (n = 6) and 91 ± 3% (n = 3), respectively; phytoene, 3.2 ± 0.3% (n = 3) and 2.0 ± 0.1% (n = 3); β-carotene, 13.2 ± 1% (n = 5) and 11 ± 2% (n = 3); and lutein, 0.5 ± 0.3% (n = 5) and 0.5 ± 0.2% (n = 3).

Homozygous lines were generated from three crtB T0 lines, two showing increased total (B-3 and B-4) carotenoid content and the other (B-1) an unchanged level of total carotenoids but increased phytoene and β-carotene content (Table 1). Azygous plants in the T1 (second generation) and T2 (third generation) generations showed similar carotenoid contents to the wild type. Homozygotes from B-1, B-3, and B-4 inherited the phenotype observed in the T0 generation in further generations (B-1 and B-4 second generation and B3 line third generation). The B-1 and B-4 second generations were sampled at 7 dpb. Interestingly, they indicate greater increases in β-carotene at this stage of ripening. Lycopene levels increased more dramatically as ripening proceeded (e.g., 10 dpb onwards), correlating with CRTB protein levels.

The same geometric isomers of carotenoids were found in the azygous and transgenic fruit. In the case of lycopene, 13-cis, 9-cis, 5-cis (6% in total), and all-trans isomers were detected. Tocopherol and quinone levels were unaffected by changes in the carotenoid content.

Phytoene Synthase Enzyme Activity and Gene Expression.

(i) Subcellular location of phytoene synthase.

Western blot analysis of crude tissue and purified plastid extracts determined the molecular weight (MW) of the immunoreactive CRTB protein to be 35.9 ± 2.8 kDa (n = 4), compared with the predicted MW of CRTB without the Psy-1 transit sequence of 35.6 kDa (Fig. 3B). Phytoene synthase activity was mainly (77 ± 4% of the total activity) present in the plastid fractions (Table 2). Plastid fractions from the crtB lines contained about 4-fold more activity compared with the azygous control; activity in the nonplastid fractions was also increased in the crtB and azygous lines (Table 2). However, as a proportion of the total activity present in both nonplastid and plastid, both the crtB and azygous total activity is similar 22 and 24%, respectively, indicating that intact plastid recovery is similar in both preparations enabling reliable comparisons to be made. A comparison of the phytoene synthase activities and CRTB in the subplastidic fractions suggested that a greater proportion of the CRTB protein was membrane-associated in the crtB plastids. The membrane activity could be solubilized with strong ionic buffer or mild detergent.

Table 2.

Phytoene synthase activity in subcellular fractions prepared from ripening tomato fruit

| Plant | Phytoene synthase activity (disintegrations/min/h/mg of protein × 10−3)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-plastid | Plastid | Subplastid fractions

|

||

| Stroma | Membrane | |||

| crtB | 4.2 ± 1.8 (22%) | 15.0 ± 4.0 (78%) | 10.0 ± 2.9 | 9.1 ± 1.7 |

| Control | 1.3 ± 0.2 (24%) | 4.2 ± 0.3 (76%) | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| Ratio crtB:control | 3.2 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 10.0 |

Data are from four determinations ± SE. The crtB line is B3-15 and the control is a respective azygous (B3-11) line. Values in parentheses are the percent total activity in each case.

(ii) Activity and gene expression in transgenic lines.

All 3 homozygous lines (B-1, B-3, and B-4) showed increases in phytoene synthase activity, ranging from 6- to14-fold (Table 3). The expression levels of Psy-1 in the crtB transgenics compared with the azygous control were unaltered (control 1.0 ± 0.2 and crtB 1.0 ± 0.1, relative amounts), and PSY-1 levels were unaffected by the presence of CRTB (data not shown).

Table 3.

Comparison of crtB RNA and protein levels, phytoene synthase activity, end products, flux control coefficients, and deviation indices among crtB lines

| Plant | crtB mRNA | CRTB | PSY activity (-fold) | Carotenoids (-fold) | C

|

Deviation index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | NA | NA | 1.0 ± 0.09 | 1.0 ± 0.20 | 0.36 ± 0.040 | NA |

| B3-15 | 0.43 | 0.6 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.17 | 0.15 ± 0.080 | −3.35 |

| B1-6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 14.4 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.06* | 0.01 ± 0.001 | −576.2 |

| B4-19 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 7.5 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.10 | 0.12 ± 0.040 | −4.50 |

Control plants are respective azygous lines. B3, B1, and B4 are homozygous lines. crtB RNA and protein are relative units and were determined by densitometric scanning. PSY activity represents the mean of three determinations. A relative unit (-fold) of 1 typically represents 3.4 × 103 disintegrations/min/mg of protein/h. Fold increases in carotenoids are the sum of lycopene, β-carotene, phytoene, and lutein, and the means of 6 to 9 determinations on 10 dpb ripe fruit. NA, not applicable; C , flux control coefficients during the onset of ripening (breaker to ripe).

, flux control coefficients during the onset of ripening (breaker to ripe).

Indicates an increase in the carotenoid content of 1.1-fold, but β-carotene increased 2-fold. Flux control coefficients and deviation indices for phytoene synthase during ripening are the mean of 2–3 experimental determinations.

Activities of Other Isoprenoid Enzymes.

IPP isomerase and GGPP synthase enzyme activities were unchanged (Table 4). When the incorporation of 14C-IPP and 14C-IPP and dimethylallyl diphosphate into prenyl phosphates and phytoene were determined, only small increases in phytoene were found (Table 4). The relative amounts of the intermediates GPP, farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), and GGPP in ripe fruit were very similar in the crtB and control lines (data not shown).

Table 4.

Comparison between crtB and control lines, enzyme activities involved in the formation of phytoene, and the incorporation of [14C]IPP and [14C]IPP + DMAPP into phytoene

| Plant | Enzyme activity (disintegrations/min/h/mg of protein × 10−4)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPP isomerase

|

GGPP synthase

|

Phytoene synthase

|

||||

| Plastid | Stroma | Plastid | Stroma | Plastid | Stroma + membranes | |

| crtB | 218 ± 12.8 | 332.0 ± 25.3 | 218.5 ± 6.6 | 411.7 ± 50.0 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.04 |

| Control | 166.2 ± 14.3 | 286.2 ± 25.1 | 240.4 ± 8.9 | 440.7 ± 14.7 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.3 ± 0.06 |

| Ratio crtB:control | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 5.0 | 5.6 |

| Phytoene formation (disintegrations/min/h/mg of protein × 10−2)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From [14C]IPP

|

From [14C]IPP + DMAPP

|

|||

| Plastid | Stroma | Plastid | Stroma | |

| crtB | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 7.0 ± 0.9 | 14.8 ± 4.2 | 10.8 ± 0.1 |

| Control | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 8.0 ± 0.8 | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 0.1 |

| Ratio crtB:control | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.3 |

Activities are the mean of four determinations ± SE. DMAPP, dimethylallyl diphosphate.

Flux Coefficients.

The values for GGPP synthase, phytoene synthase, phytoene desaturase, and lycopene cyclase in control fruit were 0.1 ± 0.02, 0.36 ± 0.03, 0.1 ± 0.03, and 0.07 ± 0.01 (n = 3), respectively. The coefficient for phytoene synthase was reduced in transgenic fruit (Table 3).

Discussion

The stable inheritance of the Erwinia crtB gene in tomato and its spatial and temporal expression in ripening fruit (Fig. 3) has led to an increase in fruit carotenoids of some 1.6-fold (Table 1). No qualitative differences, nor change to the isomers of the unsaturated carotenes such as lycopene (13-cis, 9-cis, and all-trans) were detected. The small amount of variation between individual fruit (<10%) suggests that increases above 1.2-fold are genuine elevations and not a consequence of biological variation. Nutritionally, the crtB transgenic lines not only possess higher levels of the antioxidant lycopene but also the content of β-carotene has been elevated, so that a typical crtB fruit can provide virtually all of the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of provitamin A. In comparison with high carotenoid-containing tomatoes from conventional breeding programs, the crtB lines are comparable to the high pigment (hp-1) mutant, which has increased lycopene (1.8-fold) and β-carotene (2.0) (33).

Previous attempts to increase phytoene synthesis in transgenic tomatoes to increase carotenoid levels yielded unintended pleiotrophic effects. For example, reduced levels of carotenoids have been caused by cosuppression and gene silencing (9), as well as dwarfism as a result of metabolic perturbations, specifically in the GGPP content of green fruit (10). In the present study, the use of a bacterial phytoene synthase with <35% homology to the endogenous tomato phytoene synthases circumvented cosuppression and gene silencing. The use of the PG promoter enabled expression of the crtB gene in a ripening-specific manner. Temporal expression has avoided dwarfism and unscheduled pigmentation (10), presumably because the larger pool of GGPP in ripening fruit (8-fold more than in green tissue) could be utilized for phytoene formation without limiting the amounts needed for associated isoprenoid pathways such as gibberellin formation.

Both CRTB protein levels and carotenoids increase throughout ripening (Fig. 3, Table 1), indicating that CRTB remains active and that the turnover of carotenoids is probably low in ripe fruit. The timing of crtB expression under PG control is similar to Psy-1 expression found in earlier studies (6, 7). Thus, the expression of crtB is synchronized with the endogenous fruit-specific Psy-1. Biochemical characterization of the crtB transgenic lines has shown that the Psy-1 target sequence is an effective tool for chromoplast localization of CRTB, which is located in an active form within the plastid (Table 2). Interestingly, some activity was found in the cytoplasm in both control and transgenic lines, although this may be caused by the rupture of plastids during isolation.

Increased transcript levels and enzyme activity of phytoene synthase-1 during fruit ripening have led to its assignment as the key step in the synthesis of tomato fruit carotenoids (6, 7). An approach to analyzing the influence of an enzyme on a pathway involves the determination of flux control coefficients. These determinations define the ratio between the fractional change in flux and the fractional change in enzyme activity. The sum of all of the flux control coefficients in a metabolic pathway is theoretically 1. The closer an individual flux control coefficient is to 1, the more important that enzyme is in regulating the pathway. Determination of flux control coefficients in the crtB fruit indicates that phytoene synthase has a value that is 3-fold greater than other enzymes in the pathway, supporting previous evidence that phytoene synthase is the most influential step in the pathway. Regulatory sites in starch and sucrose formation, i.e., ADP glucose-pyrophosphorylase and sucrose-phosphate, respectively, have been shown to have flux control coefficients between 0.2–0.45 (31), similar to that determined for phytoene synthase (0.36). In the transgenic fruit, however, the coefficient for phytoene synthase was significantly reduced (Table 3). The change is reflected by the negative deviation indices, which show that the additional phytoene synthase reduces the influence of phytoene synthesis on pathway flux. Therefore, despite phytoene synthase enzyme activity being substantially elevated in crtB fruit (Table 2), there was only a moderate increase in the total carotenoid content and no linear correlation between protein levels and enzyme activity, or enzyme activity and total carotenoid levels (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 3). Metabolic engineering aimed at quantitative increases of products has focused on manipulating the enzyme with the greatest regulatory influence over pathway flux. The present data suggest that this is not the most appropriate strategy in all cases and that several steps may need to be targeted simultaneously.

The largest increases in carotenoids of transgenic plants have been reported for plant tissues with either low basal levels of carotenoids [e.g., canola seeds, a 50-fold increase (14)] or carotenoid-free tissue [e.g., rice (13)]. In high-yielding carotenoid plants, proportional increases have been less dramatic. For example, in carrot root increases of 2-fold were obtained (34). The increases in crtB tomato fruit (1.6–2.0-fold; about 200 μg/g of fresh weight) are comparable with carrot. It would seem, therefore, that high carotenoid-containing tissues are less amenable to genetic manipulation of the pathway. However, although overexpression in high-yielding carotenoid tissues may not result in dramatic increases in total content, compositional changes have been significant.

Several possibilities for this finding can be postulated. In ripe tomato fruit, carotenoid storage mechanisms could already be saturated, thus limiting further increases. However, mutant tomato lines such as old gold crimson (Ogc) have carotenoid levels greater than those in crtB fruit [e.g., Ogc 6,250 ± 1,569 μg/g of dry weight (DW) compared with 4,333 ± 1,976 μg/g of DW for crtB]. The increase in PSY activity in the transgenic fruit (Table 2) has shifted the regulatory step from PSY to a later enzyme (Table 4), as indicated by the accumulation of phytoene in the fruit (Table 1). Compensation by other enzymes in the pathway can arise, as found previously after expression of a bacterial phytoene desaturase (CRTI) in tomato (11), but this seems not to be the case in the crtB fruit. The activities of earlier enzymes leading to the formation of phytoene have also not changed (Table 4). It is possible that the additional phytoene produced in the transgenic fruit cannot be accessed by phytoene desaturase, especially as the major increase of CRTB is on plastid membranes, rather than in the stroma (Table 2). Such metabolite channeling has been reported for phytoene formation in tomato (23).

In summary, we have shown that the ripening-specific expression of a bacterial phytoene synthase can overcome previous unintended pleiotrophic effects and elevate nutritionally important carotenoids in ripe tomato fruit. The changes in flux coefficients have revealed a shift in the regulatory step of carotenogenesis, which has important implications on future metabolic engineering strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Gerrish (Royal Halloway, Univ. of London) for technical assistance and Karen Bacon (Syngenta) for excellent horticultural support. Syngenta is gratefully acknowledged for the provision of greenhouse space. Financial support was principally from the European Community BIOTECH Program (no. B102 CT-930400, as part of the project of Technological Priority 1993–1996).

Abbreviations

- crtB

phytoene synthase

- dpb

days post breaker

- GGPP

geranylgeranyl diphosphate

- IPP

isopentenyl diphosphate

- PG

polygalacturonase

- Psy-1

phytoene synthase 1

- T0

primary transformants

- ts

transit sequence

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Present address: Biochemistry Unit, Institute of Child Health, 30 Guilford Street, London, United Kingdom.

References

- 1.Grusak M, DellaPenna D. Annu Rev Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:133–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton-Duell P. Endocrinologist. 1995;5:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giovannucci E. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:317–331. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.4.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seddon J M, Ajani U A, Speruto R D, Hiller R, Blair N, Burton T C, Farber M D, Gragoudas E S, Haller J, Miller D T, et al. J Am J Med Assoc. 1994;272:1413–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenthaler H K. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:47–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraser P D, Truesdale M, Bird C R, Schuch W, Bramley P M. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:405–413. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.1.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ronen G, Cohen M, Zamir D, Hirschberg J. Plant J. 1999;17:341–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fray R, Grierson D. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;22:589–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00047400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truesdale M R. Ph.D. thesis. Univ. of London; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fray R G, Wallace A, Fraser P D, Valero D, Hedden P, Bramley P M, Grierson D. Plant J. 1995;8:693–701. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romer S, Fraser P D, Kiano J W, Shipton C A, Misawa N, Schuch W, Bramley P M. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:666–669. doi: 10.1038/76523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosati C, Aquilani R, Dharmapuri S, Pallara P, Marusic C, Tavazza R, Bouvier F, Camara B, Giuliano G. Plant J. 2000;24:413–419. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye X, Al-Babili S, Kloti A, Zhang J, Lucca P, Beyer P, Potrykus I. Science. 2000;287:303–305. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shewmaker C K, Sheehy J A, Daley M, Colburn S, Yang Ke D. Plant J. 1999;20:401–412. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bird C R, Smith C J S, Ray J A, Moureau P, Bevan M W, Bird A S, Hughes S, Morris P C, Grierson D, Schuch W. Plant Mol Biol. 1988;11:651–662. doi: 10.1007/BF00017465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neudert U, Martinez-Ferez I M, Fraser P D, Sandmann G. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1392:51–58. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuch, W., Drake, R. D. & Bird, C. R. (1996) U.S. Patent W097/46690.

- 18.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuntz M, Romer S, Suire C, Hugueney P, Weil J H, Schantz R, Camara B. Plant J. 1992;2:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1992.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maudinas B, Holdsworth M, Slater A, Knapp J, Bird C R, Schuch W, Grierson D. Plant Cell Environ. 1987;10:177–184. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pecker I, Chamovitz D, Linden H, Sandmann G, Hirschberg J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;9:4962–4966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romer S, Hugueney P, Bouvier F, Camara B, Kuntz M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;196:1414–1421. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraser P D, Kiano J W, Truesdale M R, Schuch W, Bramley P M. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;40:687–698. doi: 10.1023/a:1006256302570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli U K. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wessel D, Flugge U I. Anal Biochem. 1984;118:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraser P D, Pinto M E S, Holloway D E, Bramley P M. Plant J. 2000;24:551–558. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraser P D, Schuch W, Bramley P M. Planta. 2000;211:361–369. doi: 10.1007/s004250000293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraser P D, De las Rivas J, Mackenzie A, Bramley P M. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:3971–3976. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradford M M. Anal Biochem. 1976;247:942–950. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bramley P M, Davies B H, Rees A F. In: Liquid Scintillation Counting. Crook M A, Johnson P, editors. Vol. 3. London: Heyden; 1973. pp. 76–85. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stitt M, Sonnewald U. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:341–368. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas S, Fell D A. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1998;38:65–85. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(97)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris W M, Spurr A R. Am J Bot. 1969;56:369–379. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hauptmann, R., Eschenfeldt, W. H., English, J. & Brinkhaus, F. L. (1997) U.S. Patent 5,618,988.