Abstract

Background

Obesity is a multi-faceted problem that requires complex health system responses. While no single program or service is sufficient to meet every individual’s needs, some criteria that increase the likelihood of program/service quality delivery to produce effective outcomes exist. However, although research on health commissioning is available internationally and is growing within the Australian context, no evidence exists of a multi-criteria decision-making framework to address the complexity required for effective commissioning of overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management programs or services. This study aimed to develop a set of criteria to support effective commissioning in this context.

Methods

A mixed-methods co-design approach was used to develop a multi-criteria framework. A literature review informed a three-stage co-design consensus-gathering approach. Participants included Western Australian stakeholders from the Western Australian health system, services and consumers, who reviewed, ranked and validated responses and criteria through ongoing discussions. A deliberative forum was held between the two online, modified Delphi surveys to reach a consensus among stakeholders.

Results

Through the co-design, a total of 63 stakeholders were identified: 24 completed the round 1 Delphi survey assessing 22 proposed criteria, 40 attended the deliberative forum and 30 completed the round 2 Delphi survey. A total of 4 themes arose from the co-design process: (1) reduce duplication, (2) demote criteria, (3) re-organize criteria and (4) simplify language, and 10 criteria were established: safety, collaboration and consultation, appropriateness, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, evidence-based, health service delivery model, sustainability and workforce capacity and competence. The criteria were underpinned by indicators highlighting relevant sub-themes.

Conclusions

A multi-criteria framework was developed and its application to the commissioning process will enable the selection of programs and services that will likely have an impact on individuals’ use of and satisfaction with programs and services, overweight and obesity-related outcomes and inter-agency collaborations to maximize economic and workforce resources.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12961-024-01263-y.

Keywords: Commissioning, Mixed-methods research, Obesity, Co-design, Healthy weight, Overweight

Background

Governments worldwide, including Australia, are responding to an epidemic of obesity [1] through policies and services targeting the prevention, early intervention and management of overweight and obesity [2, 3]. Australia has one of the highest rates of obesity in the world [4]. Specifically in Western Australia, in 2021, 67% of adults aged 16 years and older were classified as overweight (36%) or obese (31%) according to their self-reported body mass index (BMI) [5]. Comparatively, the Global Obesity Observatory [6] reports overweight and obesity prevalence in adults in the United Kingdom (35.6% and 20.1%, respectively), Canada (36.7% and 23.9%, respectively) and the United States (32.2% and 40.2%, respectively), while the World Healt Organisation (WHO) reports 59% of adults in the European Region are overweight or obese [7].

Responses to obesity require a systems approach among organizations, including multi-agency collaboration and engagement, relationship development and trust, good governance, broad policy context, local evaluation and adequate resourcing [8], due to the interplay between environmental, social/cultural, political, commercial, economic and behavioural determinants [9]. The Australian government is targeting obesity through its commitment to the WHO’s global target to halt the rise in overweight and obesity [10] and its recently released National Obesity Strategy 2022–2032 [4]. Aligned to the National Obesity Strategy is the Western Australian (WA) government’s Healthy Weight Action Plan 2019–2024 (hereafter, the Action Plan), developed by the WA Department of Health as a joint initiative with WA Primary Health Alliance (WAPHA) and the Health Consumers’ Council of WA (HCCWA) as one step in a coordinated approach across health to intervene and manage overweight and obesity [11]. The key focus of the Action Plan is early intervention and weight management, while supporting preventive work across the WA health sector. Early intervention involves support or intervention for individuals at risk of overweight and obesity and is aimed at preventing further health declines, while weight management interventions focus on support or intervention for people living with overweight or obesity to improve health and wellbeing outcomes, prevent further weight gain and support weight loss [11]. The Weight Education and Lifestyle Leadership (WELL) Collaborative [12] was established in 2020 to bring practitioners, consumers and community members together to inform the implementation of the Action Plan. In this study, “consumers” is inclusive of terms such as clients, patients, customers and others, and refers to people who use these programs and services.

One strategy to contribute to the aims of the Action Plan is the development of a multi-criteria framework to provide clarity and basis for commissioning and providing obesity-related services relevant to the values and outcomes of importance to policy and practice. Standard obesity service criteria previously existed but commissioning services and programs for early intervention for obesity requires a greater level of complexity. Value has traditionally been measured in terms of effectiveness and efficiency, however, recent use also extends to the personal and societal value of goal attainment [13]. Personal values may include care delivered appropriate to consumers’ individual goals, while societal values may be measured by the contribution of healthcare to social participation and connectedness [13]. Moreover, different stakeholders have different perspectives on the values required to achieve outcomes [14]. Multi-criteria decision-making analysis is an established technique used across government and broader industries to allow for streams of very different information to be included in decision-making, including qualitative and quantitative research and evaluation data, financial, past performance indicators, organizational processes and consumer feedback [15, 16]. The WA Department of Health identified the need for a set of values-based criteria for commissioning overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management programs and services under the Action Plan. This study aimed to identify existing criteria in the literature as relevant to values-based commissioning and develop and refine a multi-criteria decision-making framework.

The Australian health system

The Australian health system is delivered by a mix of program and service (hereafter collectively referred to as services) providers and health professionals who span government and non-government sectors [17]. The federal and state governments broadly share responsibility for funding, operating, managing and regulating the health system [17], with state governments having overall responsibility for hospitals and the federal government funding most of primary care [18, 19]. Decision-making processes are changing to ensure that they respond to the evolving healthcare needs of the community and the need to find market efficiencies [20].

Commissioning of health services is becoming more widespread in Australia and in other countries [21, 22], such as New Zealand [23], the United Kingdom [24, 25], and Canada [27], as well as Europe [26]. Across jurisdictions there is no one common definition of commissioning, however, in its simplest form, commissioning is seen as “a continual and iterative cycle involving the development and implementation of services based on needs assessment, planning, co-design, procurement, monitoring and evaluation” [28]. Commissioning, therefore, requires a multi-faceted, cyclical process with responsibilities ranging from assessing population needs, prioritizing health outcomes and procuring products and services to managing providers [29, 30].

In the Australian healthcare system, there is momentum growing around the use of commissioning in health, but its application has tended to focus on mental health and alcohol and other drug use sectors in Victoria [31] and to public health more broadly in NSW [13, 32]; however, limited evidence exists regarding its use in the context of obesity. Recent healthcare reform reports have highlighted the need for higher value care, defragmentation and meaningful consumer engagement to strengthen healthcare system responses [22]. Successful commissioning must include an increased focus on consumer engagement through co-creation and co-design strategies [33]. The inclusion of a broad range of stakeholders, including consumers, reduces the chance that important considerations will be missed [20].

In recent years, many health systems including Australia have tried to incorporate a values-based approach to commissioning that focusses on improving outcomes that matter to consumers [22]. One of the challenges and opportunities of values-based commissioning relates to defining and measuring the outcomes of importance to consumers and health systems. The use of a multi-criteria framework in health commissioning can be a useful tool in prioritizing values and preferences at all stages of the commissioning cycle [34] and contributing to achievement of the “quintuple aim” – improved consumer experience, improved health outcomes, reduced costs, improved provider satisfaction and health equity [35–37]. Value frameworks support decision-making by determining multiple attributes or criteria of interest to the commissioner and its stakeholders and applying these to weigh up service options [38]. Utilizing a set of criteria to assist in decision-making is particularly helpful when joint commissioners are involved, such that the various priorities and values can be captured in decision-making [22].

The criteria that are available, nationally and internationally, and that are relevant to overweight and obesity, focus on clinical care guidelines for adult obesity treatment (e.g. Australia [39] and the United Kingdom [40–43]). More recently, standards have been proposed specifying contextual factors for care delivery, including what care, by whom and where (e.g. Canada [44] and the United States [45]). No examples of a criteria framework to guide the commissioning of early intervention and weight management services for overweight and obesity could be identified, and broadening the search criteria to include other health issues did not yield further evidence of criteria to apply to the obesity context. One of the reasons for the lack of existing value-based criteria is that previously, commissioning has been implemented as a top-down approach, compared with more recent commissioning, which has utilized more of a bottom-up approach, recognizing the diverse needs and experiences of multiple stakeholders through increased collaboration and co-commissioning involving multiple organizations [19].

Beyond clinical care guidelines, it is necessary to evaluate the performance of services used to respond to the prevalence of overweight and obesity [20, 46] and ensure the sustainability of outcomes attained from participation in these services [47]. Key constructs relevant to assessing performance in healthcare are described in a number of overlapping and complementary terms, including, but not limited to, patient needs and expectations, patient-centredness, coverage, accessibility, appropriateness, equity, effectiveness, safety, quality, productivity, efficiency, effectiveness, impact, sustainability, resourcing, leadership, workforce, resilience and adaptability (e.g. [44, 46, 47]). There is a need to find a balance between selecting too broad [48] and too narrow [49, 50] a set of criteria on which to assess effectiveness, and which reflect stakeholder values.

In the absence of existing criteria, our literature review identified priority actions to increase the likelihood of success from commissioning overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management services, including being evidence based [51], theory informed [52], clear and transparent [32, 52–54], consultative across all levels [31, 51–55], encouraging inter-agency collaboration [32, 53, 55, 56], supporting workforce capacity development [32, 57] and involving the development of transactional and relational trust [53, 55]. Conversely, inadequate consultation across a range of stakeholders [31], resourcing (time, personnel and financial) [32, 56–58], relationship development [32, 56], capacity to participate in the commissioning process [31] and poorly utilized referral pathways [31, 58] would likely reduce the likelihood of success in the commissioning approach. This study addresses this gap, and develops a set of criteria for commissioning overweight and obesity services through a co-design approach.

Methods

Study design

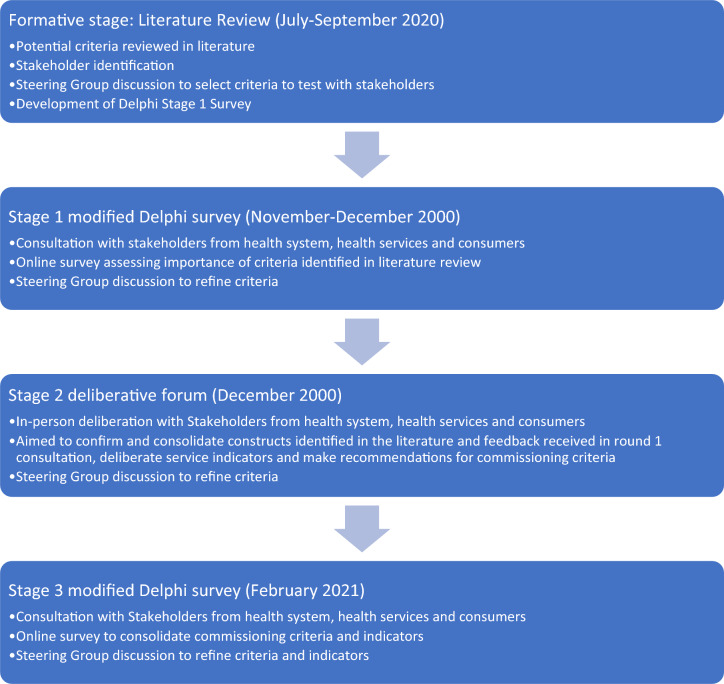

This research followed a mixed-methods sequential design (Fig. 1), guided by a steering committee comprising the stewards of the Western Australian Healthy Weight Action Plan [11] and the research team. The roles of the steering committee included identifying stakeholders to participate in the co-design process, assisting with the interpretation of results and contextualizing findings for practical implementation in the health system. A literature review was conducted to identify the existence of commissioning criteria for overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management programs and services. For expanded literature review methods and results, see Supplementary information 1. On the basis of the findings of the review, a three-stage co-design mixed-methods approach was employed to develop criteria for commissioning early intervention and weight management services. This comprised a deliberative forum held between two modified Delphi survey rounds [59]. The deliberative forums aimed to share insights from the literature review and discussion with the expert advisory group and explore their implications for current and future practices and policies. The forums included presentations, group discussions and ranking of options to be considered in the Delphi rounds. The strength of this design is that it allows for collective time to discuss and deliberate and then individually time for reflection through the Delphi.

Fig. 1.

Process of eliciting consensus on criteria components

The Delphi method is a structured, iterative process used to illicit consensus anonymously amongst stakeholders across a number of predefined rounds of consultation [100]. The purpose of the Delphi method used in this study was to achieve a consensus [59] on the importance of criteria to inform value-based commissioning, with a pre-defined number of rounds and value or agreement/consensus. However, this modified method deviated from the original process due to its mixed modality (in-person and online consultation) and use of mapped concepts in the first round of consultation in lieu of an open-ended scoping-style enquiry [101].

In stage 1, a modified Delphi technique was used to assess the importance of criteria identified through the literature review (November 2020). In stage 2, a deliberative forum was held (December 2020) which aimed to (1) confirm and consolidate evidence-based constructs; (2) deliberate service indicators relating to healthy weight and obesity services; and (3) make recommendations on the most relevant constructs and indicators to be used in the commissioning of overweight and obesity services. During a half-day workshop, small group discussions and reporting and a nominal group process [59] were used to achieve these aims. Stage 3 involved a second modified Delphi survey to further refine the stage 2 outcomes and consolidate the components of the commissioning criteria through a group consensus approach (February 2021).

Participants

A key aim of the criteria development was to have a broad representation from the health system, service providers and consumers to increase ownership of the final output, in addition to supporting service commissioning processes. The steering committee compiled a master list of stakeholders representing procurement, policy development, quality and safety, service delivery, community engagement, health consumer advisory councils and service users. Stakeholders were identified from existing networks associated with each stewarding agency, including consumer advocacy groups, the Weight Education and Lifestyle Leadership (WELL) Collaborative [12] and existing staff members. Consumer representatives with lived experience of utilizing early intervention and weight management programs and services from the HCCWA’s Healthy Weight Action Plan Consumer Advocacy Group were invited to participate. Invitations were emailed to 63 stakeholders in November 2020. Online participation was offered to enable engagement with regional stakeholders.

Data collection

Data were collected from stakeholders at three timepoints (Fig. 1): stage 1 modified Delphi survey, stage 2 deliberative forum and stage 3 modified Delphi survey. A modified process was used to accommodate the opportunity for in-person deliberation on criteria relevant to commissioning in this context.

Stage 1 modified Delphi survey: Following registration to attend the deliberative forum, stakeholders were invited to complete a 10-min online survey. The invitation email was sent by the Project Manager (L.T.), including the Participant Information Form as an attachment and a link to the online survey, providing 1 week to complete the questions prior to the deliberative forum. The stage 1 modified Delphi survey was developed on the basis of constructs identified in the literature review as potentially relevant for assessing the performance of overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management services (see Table 1). Stakeholders were asked how important they considered each criterion in facilitating successful commissioning (5-point Likert scale: extremely important to not at all important). Informed by the literature review, 22 criteria were arranged under 6 key themes: health system deliverables (inputs and outputs arising from health service delivery) n = 6; performance – consumer perspective (performance of the health system with a particular emphasis on patient and consumer perspectives) n = 4; performance – technical perspective (performance of the health system with a particular emphasis on the static or constant elements) n = 3; performance – flexibility (dynamic or responsive elements of the health system) n = 3; performance – goal attainment (attainment of goals at a population level) n = 2; and performance – capacity (the capacity of the health system to plan and deliver services) n = 4.

Table 1.

Stage 1 modified Delphi survey responses (n = 35)

| Criterion | Extremely important | Important | Moderately important | Slightly/not important |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumers’ and patients’ needs and expectations | 30 (86%) | 5 (14%) | – | – |

| Accessibility | 29 (83%) | 5 (14%) | 1 (3%) | – |

| Appropriateness | 29 (83%) | 6 (17%) | – | – |

| Equity | 28 (80%) | 5 (14%) | 2 (6%) | – |

| Health outcomes | 28 (80%) | 5 (14%) | 2 (6%) | – |

| Safety | 28 (80%) | 6 (17%) | 1 (3%) | – |

| Effectiveness | 26 (74%) | 7 (20%) | 2 (6%) | – |

| Cultural appropriateness | 23 (68%) | 10 (29%) | 1 (35) | – |

| Consultation and collaboration | 23 (66%) | 10 (28%) | 2 (6%) | – |

| Impact | 23 (66%) | 10 (28%) | 2 (6%) | – |

| Sustainability | 22 (63%) | 11 (31%) | 2 (6%) | – |

| Efficiency | 21 (60%) | 10 (28%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (3%) |

| Coverage | 20 (57%) | 14 (40%) | 1 (3%) | – |

| Workforce competence | 19 (56%) | 15 (44%) | – | – |

| Health system resources and structures | 16 (46%) | 12 (34%) | 7 (20%) | – |

| Health system processes, functions and context | 15 (44%) | 11 (32%) | 6 (18%) | 2 (6%) |

| Resilience | 15 (43%) | 11 (31%) | 8 (23%) | 1 (3%) |

| Adaptability | 14 (40%) | 15 (43%) | 6 (17%) | – |

| Fidelity | 13 (38%) | 13 (38%) | 8 (24%) | – |

| Health services | 11 (31%) | 18 (51%) | 6 (17%) | – |

| Capacity | 10 (29%) | 16 (47%) | 7 (21%) | 1 (3%) |

| Productivity | 10 (28%) | 17 (49%) | 7 (20%) | 1 (3%) |

Stage 2 deliberative forum: During the deliberative forum, a whole-group presentation was delivered to provide background information to stakeholders, including the results of the stage 1 modified Delphi survey, followed by semi-structured small group activities to encourage discussion and shape and reshape ideas. Interactive and visual strategies, including nominal group processes and printed resources, were used to engage stakeholders and encourage further discussion. Forum participants were divided across tables comprising a mix of government (health system), non-government (service providers) and consumers, and included one online group of four stakeholders. A nominated facilitator assisted in guiding the group discussions and key discussion points were recorded by trained scribes and agreed upon within each group. Stakeholders were provided with the opportunity to rename and/or add to the criteria list by writing new names/constructs on their post-it notes. A nominal group process [59] was used to allow the participants to denote the significance of each criterion. Stakeholders were asked to assign 15 votes to their most important criteria by using sticky dots. The online participants responded by emailing a list of votes to the facilitator. Voting from the nominal group process was tallied and added to the qualitative feedback gathered from the forum participants. Findings arising from the forum were presented to the steering committee, and the criteria were reshaped to reflect the feedback provided by stakeholders.

Stage 3 modified Delphi survey: A modified Delphi technique was used to present feedback to stakeholders on the criteria refinement as well as consolidation of indicators under each criterion. A modified Delphi survey was developed, and stakeholder agreement was sought regarding the importance of each indicator in assessing overweight and obesity services. Importance was measured as for the stage 1 modified Delphi survey, on a 5-point Likert scale (extremely important to not at all important). See the Supplementary Information for the full list of criteria and indicators. All 63 deliberative forum invitees (including those who were unable to attend) were invited to participate via email in February 2021. The survey was open across a 2-week period, with a reminder email sent 1 week later.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted using SPSS version 27 [60] to determine the level of agreement with the presented criteria and recommendations for changes. The categories “slightly important” and “not at all important” were combined for these analyses due to low response rates in each category. In addition, qualitative data in the form of post-it notes and hand-written edits were collected from the 40 stakeholders attending the forum, and content analysis was performed to code and group comments and align the criteria. The results from the content analysis were combined with quantitative data to guide reflexive changes to criteria organization and wording [61]. Consensus was defined as a general agreement (important/extremely important) of greater than 70% of Delphi respondents. This level of agreement has been considered appropriate in previous Delphi studies [62, 63].

Ethical considerations

Approval was provided by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2020-0619). Potential participants were emailed an information sheet describing the research and interested participants provided online consent. No monetary incentives or gift vouchers were provided to participants to complete the surveys; however, consumers recruited from the HCCWA who were not otherwise paid for their time in attending the deliberative forum were offered payment at a nominal rate as per HCCWA guidelines for the duration of the forum [64].

Results

Literature review

Detailed information on the literature review is provided in Supplementary material 1. However, to provide context for the origin of the first set of criteria tested in this study, a brief summary is included here. We found limited evidence for the existence of a multi-criteria to inform commissioning of overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management services. Much of the available literature referenced health commissioning activity internationally (e.g. United Kingdom, United States, Germany) with no consistency in model preference or superiority [65]. Evident in the literature is a blueprint for the design of multi-criteria (e.g. [44, 51, 52, 66, 67]), however, in many cases, stakeholder consultation is tokenistic [31] and/or inadequate in breadth [31, 51–55]. Involving inadequately trained personnel is likely to impede the development of successful commissioning frameworks that are misaligned to commissioner priorities; hence, there is a need to develop the capacity of stakeholders to engage in the commissioning process [32, 57, 68]. A number of constructs have been specified in general health commissioning and health service performance examples, the most common of which include consultation and collaboration [32, 53–56, 69–72], appropriateness [32, 53–56, 69–72], health outcomes [32, 52, 53, 55, 72, 73], workforce capacity through health system resources and structures [56, 66, 73, 74], effectiveness [32, 53, 69, 73] and resilience [32, 53, 56, 66].

Description of participants

The stakeholder pool included 63 nominees (79% female, 90% metropolitan based) from across the government health system (n = 23), non-government service providers (n = 26), consumers (n = 12) and the university sector (n = 3). Responses to the stage 1 modified Delphi survey were received from 35 of the 63 forum nominees (56% response rate), comprising eight government, 13 non-government, 13 consumer and 1 research stakeholder; 28 of the stakeholders were female (80%).

More than two thirds of the 63 nominees registered to attend the stage 2 deliberative forum (n = 43, 68%). The deliberative forum was attended by 40 stakeholders (63%); the majority were female (n = 34; 85%) and represented government (n = 11), non-government (n = 17) and consumer (n = 12) stakeholders; four stakeholders joined the forum online. Reasons for declining attendance included schedule conflicts and illness.

Following the deliberative forum, a second Delphi survey was distributed to all 63 members of the original stakeholder pool. The survey was completed by 31 stakeholders (49%). No demographic or group representation details were collected in the anonymous stage 3 modified Delphi survey.

Stage 1 modified Delphi survey

Agreement on the importance of the 22-items presented was high (Table 1); 17 of the 22 (77%) presented criteria were identified as being extremely important or important by 80% or more of stakeholders: consumers’ needs and expectations; accessibility; appropriateness; equity; health outcomes; safety; effectiveness; cultural appropriateness; consultation and collaboration; impact; sustainability; efficiency; coverage; workforce competence; health system resources and structures; adaptability and health services. The remaining five criteria were considered extremely important or important by 74–77% of stakeholders: health system, processes, functions and context; resilience; fidelity; capacity; and productivity. No criteria were considered not important.

Stage 2 deliberative forum

Small group deliberation regarding criteria refinement identified four themes: (1) reduce duplication, (2) demote criteria, (3) re-organize criteria and (4) simplify language. Reduce duplication: stakeholders recommended merging several criteria due to definition overlap, interdependencies within criteria and duplication of items. Demote criteria: thematic re-grouping and merging recommendations of stakeholder recommendations resulted in some criteria being demoted to indicator level, a sub-category of criteria. Re-organize criteria: stakeholder recommendations were integrated into the criteria re-design where possible. Some criteria that scored fewer votes in the nominal group process were supported by the peer-reviewed literature. Thus, some items were retained either as criteria or sub-indicators in supporting materials. Simplify language: stakeholders reported the need for simplified language to increase the accessibility of the criteria set to a broader audience. Stakeholder feedback was incorporated into the revision process including criteria naming, definitions and indicator terminology.

In total, 33 items were listed for voting during the forum, and 390 votes were cast. The 9 highest scoring items, each receiving 5% or more of the votes were, holistic (31 votes), appropriateness (26 votes), cultural appropriateness (26 votes), empowerment (26 votes), person-centred (25 votes), sustainability (23 votes), effectiveness (22 votes), partnership (22 votes) and equity (21 votes).

Following the forum, the steering committee discussed the thematic results from the content analysis of stakeholder feedback in the forum and the results of the stage 1 modified Delphi survey. This resulted in the development of a set of 10 criteria: safety, collaboration and consultation, appropriateness, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, evidence based, health service delivery model, sustainability and workforce capacity and competence. The criteria were underpinned by indicators that were subsequently tested with the stakeholder group in the stage 3 modified Delphi survey.

Stage 3 modified Delphi survey

There was a high level of agreement amongst stakeholders regarding the importance of most of the indicators included in the stage 3 modified Delphi survey (Supplementary Material 1). For 59 of the 62 indicators, 70% or more of the stakeholders agreed that the item was important or extremely important as a criterion for commissioning early intervention and weight management services for overweight and obesity.

In total, three items were considered important or extremely important by between 62% and 69% of the stakeholders, respectively (Table 2). These indicators relate to cross-agency partnerships and waste reduction. One item (waste reduction) was repeated thrice in the framework. Qualitative responses to the stage 3 modified Delphi survey highlighted the need for language simplification and a reduction in duplication to improve the understanding and application of these criteria.

Table 2.

Stage 3 modified Delphi survey responses (selected items) (n = 31)

| CRITERION indicator | Sub-indicator | Extremely important | Important | Moderately important | Slightly important/not important |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEALTH SERVICE DELIVERY MODEL | |||||

| Cross-agency partnerships | The program/service describes how their infrastructure supports effective planning, development, implementation and evaluation | 8 (28%) | 12 (41%) | 6 (21%) | 3 (10%) |

| Cross-agency partnerships | The program/service considers influences in the micro, meso and macro levels affect effectiveness | 6 (21%) | 12 (41%) | 6 (21%) | 5 (17%) |

| SUSTAINABILITY | |||||

| Waste reduction | The program/service endeavours to reduce waste (e.g. financial, personnel) by developing innovative programs and reducing duplication | 6 (20%) | 14 (47%) | 6 (20%) | 4 (13%) |

Usability testing

To finalize and operationalize the criteria, the steering committee discussed the language of the criteria and indicators, the appropriateness of the associated outcomes and the identification of sample measures relating to the criteria and indicators. Minor adjustments were made to simplify the language, but specific terms used by the consultative group were retained where possible to maintain ownership across the stakeholder group. The steering committee also considered the number of criteria and indicators. As per discussions in the deliberative forum, it was deemed crucial to have multiple criteria that could be adjusted to align with the specific commissioning context and the desired outcomes. This allows commissioners and their stakeholders to mutually determine the criteria pertinent to their commissioning requirements, acknowledging that this may result in different criteria being applied in different commissioning activities.

Discussion

This study co-designed a multi-criteria framework to guide the commissioning of overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management services. To the best of our knowledge, this type of criterion has not been developed by the government previously for this purpose in Australia, and criteria developed in other countries focus on clinical guidelines [44] or on selecting the right program for consumers [43]. Health commissioning in Australia is in its infancy; however, research has demonstrated how embedding multi-criteria in decision-making is linked to improved outcomes for consumers through more targeted investment [75]. The increased use of relevant criteria in commissioning decisions will translate into improved consumer and provider experiences [76], improved health outcomes [77, 78], reduced costs and greater value-for-money [75].

Through a co-design approach, 10 key criteria were identified as being comprehensive in assessing the characteristics of overweight and obesity services: safety, collaboration and consultation, appropriateness, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, evidence based, health service delivery model, sustainability and workforce capacity and competence. The consultative nature of the co-design approach used in this research helped shape, organize and prioritize the constructs discussed to determine the final criteria. These criteria are supported by literature as being relevant to commissioning for overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management and obesity related health issues. Importantly, these criteria also align with frameworks for intervention design, such as the Acceptability, Practicability, Effectiveness, Affordability, Side-effects and Equity (APEASE) criteria used in the United Kingdom [102], reiterating the usability across all stages of the commissioning cycle.

The findings of this study demonstrated the need to focus on the person receiving healthcare to ensure value [79] and outcome achievement [13]. Notably, stakeholders identified safety as being of particular importance, recognized through its inclusion as the first criterion listed in the multi-criteria decision-making framework. Safety encompasses the safe provision of care, the avoidance of harm and quality and appropriateness of the service or program [46]. It also includes person-centred care, with tailored planning, development, implementation and evaluation relevant to population-specific needs. Sensitivity to culture and responsiveness to harm caused by weight stigma [44, 80] and individuals with physical and mental illness are included in this criterion.

Research has identified the importance of consultation and collaboration, in terms of care coordination and community support, on health outcomes, program attendance and patient experiences [32, 47, 53–56, 69–72, 81]. Stakeholders in our study argued for the importance of a patient-centred approach, with the patient as a key partner in the healthcare journey and in decisions made about their care, treatment or experiences. This is particularly important given the individualized and holistic responses needed to achieve outcomes in overweight and obesity [82].

Previously developed guidelines consider appropriateness in relation to the treatment or care provided, consumer satisfaction and experience of care, the program or service being patient-centred and responsive to patient needs [32, 46, 52–54, 56, 70, 73]. In addition, stakeholders in this research noted the importance of cultural safety, adaptability, holistic and person-centredness under the appropriateness criteria.

The effectiveness of the program or service in terms of clinical care, quality and safety [46] and outcome achievement [32, 53, 69, 73, 81] is established on the basis of existing criteria. Effectiveness is undoubtedly important for understanding the success of a program or service. Less commonly attributed to the effectiveness of a program or service is the need for the program or service to empower consumers [83] and to contribute to improved health literacy [84].

The cost-effectiveness of a commissioned program or service is an important component in measuring efficiency [46]. Resource efficiencies and minimizing waste through duplication were identified by stakeholders as key considerations in determining a program’s efficiency and are echoed by research focussed on improving health efficiencies [56, 72, 73, 85].

Stakeholders noted that the criteria for equity involves access to programs and services through appropriate locations, costs and availability. Further, responsivity in program planning, development, delivery and evaluation of vulnerable groups and cultures that have different ethnic, religious and/or linguistic backgrounds contributes to equitable access to programs and services [86], a component of the quintuple aim [37]. Equity is of particular importance as Western Australia is the second largest state in the world, resulting in sparse regional population and geographical challenges in providing services.

The evidence base for what works in early intervention for overweight and obesity is still emerging and opportunities to contribute to the evidence should be sought, especially when innovation is a feature of a commissioned program or service. Best or good practice (when best practice is not available) should be adhered to and used to individualize program content [81]. Evaluation methods will demonstrate program fidelity and quality as key components in understanding the evidence base [87]. Program evaluation can inform service prioritization and effective resource allocation [20], and importantly, to stakeholders in this research, provide insights into participant retention and service quality. A holistic approach to overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management, considering the whole person, was identified by stakeholders as a key component in participants’ goal attainment.

The health service delivery model criteria recognizes the need for a whole-of-systems approach throughout planning, development, implementation and evaluation [58, 88]. This criteria seeks to demonstrate a strong governance and organizational structure [32, 46, 53, 56, 66] to support program or service delivery and strive for innovation in this delivery.

The sustainability of the outcomes achieved through participation in a service and of the organization itself are important components in overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management. As supported by previous research, the participants noted the importance of program fidelity [87], flexibility [47] and transition strategies [47, 82]. In addition, the organization providing the program needs to be innovative [53, 56, 69, 73], resilient [32, 53, 56, 66, 89] and seek to reduce waste by reducing duplication within and between programs [85].

An adequately sized and skilled workforce is essential to deliver overweight- and obesity-related outcomes [56, 66, 73, 74, 90]. Stakeholders in this study highlighted the relationships between health professionals and consumers as key elements in achieving outcomes, noting that they take time to develop and the process restarts when staff turnover occurs. Similar to Whelan et al. [47], this criterion indicates the need for ongoing training for new and existing workforce on planning, implementation, evaluation and content.

To operationalize our criteria in the commissioning cycle, a multi-criteria decision-making analysis (MCDA) approach [65] is recommended, which would involve taking our criteria and working with commissioners and relevant stakeholders to decide on which of the criteria are relevant to the commissioning program objectives. Utilizing the MCDA approach enables selection of criteria that reflect a variety of perspectives, values and needs [91]. Deliberation on these perspectives, values and needs is a key component in the success of the MCDA approach in selecting programs/services that meet the needs of the target population and deliver quality outcomes. Embedding the selected criteria across the three stages of the commissioning cycle – planning, contracting and monitoring and evaluation – provides increased opportunities for improved program and service performance, quality improvement and outcome achievement [15]. Given the relative infancy of this type of health commissioning in Australia, we suggest a user guide be developed to support commissioners through the process and training for all stakeholders engaged in decision-making and responding to commissioning opportunities. This suggested guide and training may outline commissioning and the process of using multi-criteria in decision-making; how to design a multi-criteria approach to decision-making; when and how to engage stakeholders; and opportunities for reflection for process improvement.

Strengths and limitations

The criteria developed in this research were strengthened by the involvement of multiple levels of stakeholders in the development process. The representation of government, non-government and consumer stakeholders is important for the co-design approach and provides the potential for greater buy-in in the implementation of these quality criteria in the commissioning process. Repeated consensus-building processes enabled the refinement of criteria and facilitated the opportunity for clarification of the feedback provided by the participants. The response rates achieved in this study were similar to those of other similar studies, noting that higher numbers of items included in consensus approaches are likely to result in lower response rates [92]. The Delphi rounds in this study included 22 and 62 items. The development of these quality criteria is an emerging technique to support the commissioning of programs and services related to overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management, and adaptations will be required to implement this approach in existing processes. Key stakeholder involvement in relevant departments, including procurement functions, will assist in translating these criteria into practice.

While these criteria were developed on the basis of a review of the literature and stakeholder recommendations, they are yet to be tested in the commissioning process applied to the overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management field. It is possible that further modifications could be required following implementation testing; however, this was beyond the scope of this study. While the criteria may also be applicable to related conditions, including chronic conditions, they have not been built for this purpose, and thus relevant testing would need to occur for appropriateness amid the program/service funding and policy context.

Conclusions/implications

Commissioning for health is still in its infancy in Australia. However, its use can strengthen the procurement process owing to the increased transparency, opportunities for inter-agency collaboration and partnerships and focus on evidence- and theory-based decisions afforded by the process. When combined with a multi-criteria framework to guide decision-making, commissioning can contribute to positive outcomes for the community by prioritizing and valuing a range of perspectives, including those of consumers. This approach is beneficial in regards to overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management programs and services in Australia to help halt the rise in overweight and obesity. Engaging all stakeholders, including consumers, through a multi-criteria decision-making analysis approach using quality criteria to select, manage and evaluate programs and services across the commissioning cycle is likely to improve the success of programs and services with regard to positive consumer outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the stakeholders across the health system, services and consumers who contributed their views about commissioning of overweight and obesity early intervention and weight management programs and service. This research was funded by the Western Australian Department of Health and the WA Primary Health Alliance (WAPHA).

Author contributions

L.T. developed the instruments and collected and analysed the data to inform the development of criteria; S.R., A.B. and S.B. led the research, delivered the deliberative forum, reviewed the data to confirm themes and supported L.T. across project activities; and H.M. provided guidance to the research in the role of commissioner and confirmed the relevance and contextual application of the criteria. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Western Australian Department of Health and WA Primary Health Alliance (WAPHA).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2020-0619). All participants provided informed written consent to participate.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jaacks LM, Vandevijvere S, Pan A, McGowan CJ, Wallace C, Imamura F, et al. The obesity transition: stages of the global epidemic. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(3):231–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Hara L, Gregg J. The war on obesity: a social determinant of health. Health Promot J Austr. 2006;17(3):260–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos SX. The ineffectiveness and unintended consequences of the public health war on obesity. Can J Public Health. 2015;106(2):e79-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Commonwealth of Australia. The National Obesity Strategy 2022–2032. Health Ministers Meeting; 2022.

- 5.Epidemiology Directorate. Health and Wellbeing of Adults in Western Australia 2021. Western Australia: Department of Health; 2022.

- 6.World Obesity Federation. Global Obesity Observatory United Kingdom: World Obesity Federation; 2024. https://data.worldobesity.org/.

- 7.World Health Organisation. WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022. Contract No.: Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 8.Bagnall A-M, Radley D, Jones R, Gately P, Nobles J, Van Dijk M, et al. Whole systems approaches to obesity and other complex public health challenges: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li B, Alharbi M, Allender S, Swinburn B, Peters R, Foster C. Comprehensive application of a systems approach to obesity prevention: a scoping review of empirical evidence. Front Public Health. 2023. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1015492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organisation. European Regional Obesity Report 2022. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022. Report No.: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 11.Western Australian Department of Health. WA healthy weight action plan 2019–2024. Perth: Western Australian Department of Health; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Western Australian Department of Health. The WELL Collaborative Perth: Western Australian Department of Health; 2021. https://thewellcollaborative.org.au/.

- 13.Dawda P, True A, Dickinson H, Janamian T, Johnson T. Value-based primary care in Australia: how far have we travelled? Med J Aust. 2022;216(S10):S24–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landon SN, Padikkala J, Horwitz LI. Defining value in health care: a scoping review of the literature. Int J Quality Health Care. 2021. 10.1093/intqhc/mzab140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams I, Robinson S, Dickinson H. Multi-criteria decision analysis and priority setting processes. In: Williams I, Robinson S, Dickinson H, editors. Rationing in health care: the theory and practice of priority setting. Bristol: Bristol University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baltussen R. Question is Not Whether but How to use MCDA. Value & Outcomes Spotlight. 2015; 14–6.

- 17.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health system overview Canberra: Australian government; 2022. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-system-overview.

- 18.Robinson S, Dickinson H, Durrington L. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue? Reviewing the evidence on commissioning and health services. Aust J Prim Health. 2016;22(1):9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bates S, Harris-Roxas B, Wright M. Understanding the costs of co-commissioning: early experiences with co-commissioning in Australia. Aust J Public Adm. 2023;82(4):462–87. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atwal S, Schmider J, Buchberger B, Boshnakova A, Cook R, White A, et al. Prioritisation processes for programme implementation and evaluation in public health: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2023. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1106163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bates S, Wright M, Harris-Roxas B. Strengths and risks of the primary health network commissioning model. Aust Health Rev. 2022;46(5):586–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koff E, Pearce S, Peiris DP. Collaborative commissioning: regional funding models to support value-based care in New South Wales. Med J Aust. 2021;215(7):297-301.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan T, Hansen P. Determining criteria and weights for prioritizing health technologies based on the preferences of the general population: a New Zealand pilot study. Value Health. 2017;20(4):679–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheaff R, Charles N, Mahon A, Chambers N, Morando V, Exworthy M, et al. NHS commissioning practice and health system governance: a mixed-methods realistic evaluation. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2015. 10.3310/hsdr03100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddy BP, Thokala P, Iliff A, Warhurst K, Chambers H, Bowker L, et al. Using MCDA to generate and interpret evidence to inform local government investment in public health. EURO J Decis Proc. 2016;4(3–4):161–81. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gansen F, Klinger J, Rogowski W. MCDA-based deliberation to value health states: lessons learned from a pilot study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laba TL, Jiwani B, Crossland R, C M. Can multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) be implemented into real-world drug decision-making processes? A Canadian provincial experience. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2020;7:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Australian Government Department of Health. A commissioning overview in the PHN context Canberra: Australian Government; 2018. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/PHNCommissioningResources

- 29.Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA). Chapter 16: Commissioning United Kingdom: HFMA; 2023. https://www.hfma.org.uk/publications/hfma-introductory-guide-to-nhs-finance.

- 30.Murray JG. Towards a common understanding of the differences between purchasing, procurement and commissioning in the UK public sector. J Purch Supply Manag. 2009;15(3):198–202. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joyce C. Person-centred services? Rhetoric versus reality. Aust J Prim Health. 2017;23(1):10–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris M, Gardner K, Powell Davies G, Edwards K, McDonald J, Findlay T, et al. Commissioning primary health care: an evidence base for best practice investment in chronic disease at the primary-acute interface: an evidence check. Australia: Sax Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vargas C, Whelan J, Brimblecombe J, Allender S. Co-creation, co-design, co-production for public health – a perspective on definitions and distinctions. Public Health Research & Practice. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Thokala P, Devlin N, Marsh K, Baltussen R, Boysen M, Kalo Z, et al. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health care decision making—An introduction: report 1 of the ISPOR MCDA emerging good practices task force. Value Health. 2016;19(1):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Modica C, Lewis JH, Bay RC. The value transformation framework: applied to diabetes control in federally qualified health centers. J Multidiscip Healthcare. 2021;14:3005–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansen P, Devlin N. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) in healthcare decision-making. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Health and Medical Research Council. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity for adults, adolescents and children in Australia. Canberra: Australian Government; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Institute for Health and Care Excellent (NICE). Obesity: clinical assessment and management. In: NICE, editor. London, UK 2016.

- 41.National Institute for Health and Care Excellent (NICE). Obesity in adults: prevention and lifestyle weight management programmes. In: NICE, editor. London, UK 2016.

- 42.National Institute for Health and Care Excellent (NICE). A guide to delivering and commissioning Tier 2 weight management services for children and their families. In: NICE, editor. London, UK 2017.

- 43.National Institute for Health and Care Excellent (NICE). Weight management: lifestyle services for overweight or obese adults. In: NICE, editor. London, UK 2014.

- 44.Wharton S, Lau DCW, Vallis M, Sharma AM, Biertho L, Campbell-Scherer D, et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. CMAJ. 2020;192(31):E875–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dietz WH, Gallagher C. A proposed standard of obesity care for all providers and payers. Obesity. 2019;27(7):1059–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levesque J-F, Sutherland K. Combining patient, clinical and system perspectives in assessing performance in healthcare: an integrated measurement framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whelan J, Love P, Millar L, Allender S, Bell C. Sustaining obesity prevention in communities: a systematic narrative synthesis review. Obes Rev. 2018;19:839–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Committee on Core Metrics for Better Health at Lower C, Institute of M. In: Blumenthal D, Malphrus E, McGinnis JM, editors. Vital Signs: Core Metrics for Health and Health Care Progress. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2015 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. 2015. [PubMed]

- 49.Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Porter ME, Lee TH. From volume to value in health care: the work begins. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1047–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiecha JL, Hall G, Gannett E, Roth B. Development of healthy eating and physical activity quality standards for out-of-school time programs. Child Obes. 2012;8(6):572–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greenhalgh T, Kristjansson E, Robinson V. Realist review to understand the efficacy of school feeding programmes. BMJ. 2007;335(7625):858–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Naylor C, Goodwin N. Building High Quality Commissioning: What role can external organisations play? London, UK: The Kings Fund; 2010.

- 54.Dickinson H, Peck E, Durose J, Wade E. Efficiency, effectiveness and efficacy: towards a framework for high-performance in healthcare commissioning. Public Money Manag. 2010;30(3):167–74. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Addicott R, Ham C. Commissioning and funding general practice: making the case for family care networks. London, UK: The King’s Fund; 2014.

- 56.Gardner K, Davies GP, Edwards K, McDonald J, Findlay T, Kearns R, et al. A rapid review of the impact of commissioning on service use, quality, outcomes and value for money: implications for Australian policy. Aust J Prim Health. 2016;22(1):40–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bradley F, Elvey R, Ashcroft D, Noyce P. Commissioning services and the new community pharmacy contract: (2) drivers, barriers and approaches to commissioning. Pharm J. 2006;277(7413):189–92. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mears R, Jago R, Sharp D, Patel A, Kipping R, Shield JPH. Exploring how lifestyle weight management programmes for children are commissioned and evaluated in England: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Gonsalves C, Wood TJ. Using consensus group methods such as Delphi and Nominal Group in medical education research. Med Teach. 2017;39(1):14–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.von der Gracht HA. Consesnsus measurement in Delphi studies: review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2012;8:1525–36.

- 101.Kelly SE, Moher D, Clifford TJ. Defining rapid reviews: a modified Delphi consensus approach. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2016;32(4):265–75. 10.1017/S0266462316000489. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; Released 2020.

- 61.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Slade S, Dionne C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Standardised method for reporting exercise programmes: protocol for a modified Delphi study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Health Consumers' Council of Western Australia. CCE Engagement Policy Perth: HCCWA; 2020. https://www.hconc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/SAA_05_CCE_Engagement-Policy-PAYMENT-TABLE-ONLY-Dec-2019.pdf.

- 65.Gongora-Salazar P, Rocks S, Fahr P, Rivero-Arias O, Tsiachristas A. The use of multicriteria decision analysis to support decision making in healthcare: an updated systematic literature review. Value Health. 2023;26(5):780–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oberst S, van Harten W, Sæter G, de Paoli P, Nagy P, Burrion JB, et al. 100 European core quality standards for cancer care and research centres. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(8):1009–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kenneth L, Jonathan K. In-DEPtH framework: evidence-informed, co-creation framework for the design, evaluation and procurement of health services. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e026482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Checkland K, Coleman A, Harrison S, McDermott I, Snow S. Commissioning in the English national health service: what’s the problem? J Soc Policy. 2012;41(3):533–50. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanderson J, Lonsdale C, Mannion R. What’s needed to develop strategic purchasing in healthcare? Policy lessons from a realist review. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2019;8(1):4–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sobanja M. What is world-class commissioning? United Kingdom: Hayward Medical Communications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chappel D, Miller P, Parkin D, Thomson R. Models of commissioning health services in the British National Health Service: a literature review. J Public Health Med. 1999;21(2):221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dykgraaf SH, Barnard A. The role of cost-effectiveness analysis in investment decision making by primary health networks. Med J Aust. 2020. 10.5694/mja2.50689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peskett S. The challenges of commissioning healthcare: a discussion paper. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2009;24(2):95–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.NHS Diabetes and Kidney Care. Commissioning Diabetes and Kidney Care Services. In: Care NDaK, editor. United Kingdom: NHS; 2011.

- 75.Robin B, Shamesh N, Cameron A, Geoffrey B, Amanda D, Nicholas G. Development and pilot of a multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) tool for health services administrators. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e025752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Islam MK, Ruths S, Jansen K, Falck R, Mölken MR-V, Askildsen JE. Evaluating an integrated care pathway for frail elderly patients in Norway using multi-criteria decision analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cleemput I, Devriese S, Kohn L, Westhovens R. A multi-criteria decision approach for ranking unmet needs in healthcare. Health Policy. 2018;122(8):878–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Marsh K, Dolan P, Kempster J, Lugon M. Prioritizing investments in public health: a multi-criteria decision analysis. J Public Health. 2012;35(3):460–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.West R, Michie S, Atkins L, Chadwick P, Lorencatto F. Achieving behaviour change: a guide for local government and partners. London: Public Health England; 2019.

- 79.Dawda P, Janamian T, Wells L. Creating person-centred health care value together. Med J Aust. 2022. 10.5694/mja2.51531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rubino F, Puhl RM, Cummings DE, Eckel RH, Ryan DH, Mechanick JI, et al. Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):485–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Funnell MM, Brown TL, Childs BP, Haas LB, Hosey GM, Jensen B, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 1):S89-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fastenau J, Kolotkin RL, Fujioka K, Alba M, Canovatchel W, Traina S. A call to action to inform patient-centred approaches to obesity management: development of a disease-illness model. Clin Obesity. 2019;9(3):e12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hardt J, Canfell OJ, Walker JL, Webb K-L, Brignano S, Peu T, et al. Healthier together: co-design of a culturally tailored childhood obesity community prevention program for Māori & Pacific Islander children and families. Health Promot J Austr. 2021;32(S1):143–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zaidman EA, Scott KM, Hahn D, Bennett P, Caldwell PH. Impact of parental health literacy on the health outcomes of children with chronic disease globally: a systematic review. J Paediatr Child Health. 2023;59(1):12–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Productivity Commission. Efficiency in health. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thomas SL, Wakerman J, Humphreys JS. Ensuring equity of access to primary health care in rural and remote Australia—What core services should be locally available? Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3):327–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Blackford K, Leavy J, Vidler A-C, Chamberlain D, Pollard C, Riley T, et al. Initiatives and partnerships in an Australian metropolitan obesity prevention system: a social network analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021. 10.1186/s12889-021-11599-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Anderson JE, Ross AJ, Macrae C, Wiig S. Defining adaptive capacity in healthcare: a new framework for researching resilient performance. Appl Ergon. 2020;87:103111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Begley A, Pollard CM. Workforce capacity to address obesity: a Western Australian cross-sectional study identifies the gap between health priority and human resources needed. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Glaize A, Duenas A, Di Martinelly C, Fagnot I. Healthcare decision-making applications using multicriteria decision analysis: a scoping review. J Multi-Criteria Decis Anal. 2019;26(1–2):62–83. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gargon E, Crew R, Burnside G, Williamson PR. Higher number of items associated with significantly lower response rates in COS Delphi surveys. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;108:110–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.