Abstract

Background

Advances in treatment have swiftly alleviated systemic inflammation of Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK), while subclinical vascular inflammation and the ensuing arterial remodeling continue to present unresolved challenges in TAK. The phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) is regarded as the first step in vascular pathology and contributes to arterial remodeling. Exosomes facilitate the transfer and exchange of proteins and specific nucleic acids, thereby playing a significant role in intercellular communication. Little is known about the modulatory role of serum exosomes in phenotypic switching of VSMC and vascular remodeling in TAK.

Methods

Serum exosomes isolated from TAK patients were co-cultured with VSMC to identify the modulatory role of exosomes. VSMC were transfected with miR-199a-5p mimic and inhibitor. CCK8 assays and EdU assays were performed to measure proliferative ability. The migration of VSMC was evaluated by scratch assays and transwell migration assays. The flow cytometry was employed to identify apoptosis of VSMC. Dual-luciferase reporter assay, RNA immunoprecipitation assay and fluorescence in situ hybridization were utilized to validate the target gene of miR-199a-5p. The correlational analysis was conducted among exosome miRNA, serum MMP2, TIMP2 and clinical parameters in TAK patients.

Results

The coculture of VSMC with serum exosome mediated dedifferentiation of VSMC. Through gain- and loss-of-function approaches, miR-199a-5p over-expression significantly increased expression of VSMC marker genes and inhibited VSMC proliferation and migration, whilst the opposite effect was observed when endogenous miR-199a-5p was knocked down. The overexpression of miR-199a-5p suppressed VSMC apoptosis. Further, MMP2 serves as functional target gene of miR-199a-5p. The correlation analyses revealed an inverse correlation between Vasculitis Damage Index and exosome miR-199a-5p level or serum MMP2, which requires validation in a larger cohort.

Conclusion

Our study indicated that the miR-199a-5p/MMP2 pathway played a role in inhibiting the migration, proliferation and apoptosis of VSMC. The decreased secretion of MMP2 may potentially prompt the intimal infiltration of inflammatory cells within the vascular wall, offering a novel therapeutic opportunity by tackling both inflammatory responses and the neointimal overgrowth associated with TAK arterial damage. Moreover, exosome miR-199a-5p and MMP2 derived from serum possess potential as future biomarkers for vascular injury.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13075-025-03475-1.

Keywords: Takayasu’s arteritis, Vascular remodeling, Vascular smooth muscle cells, Exosome, miRNA

Introduction

Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK) is characterized as an autoinflammatory large-vessel vasculitis (LVV), distinguished by its highly selective tissue tropism for the aorta and its primary branches [1]. TAK predominantly affects young women. At first, non-specific symptoms often predominate, such as low fatigue, fever, emaciation or even asymptomatic. With the progression of disease, vascular ischemic symptoms appear gradually, resulting in stroke, hypertension, vision loss and other chronic vascular complications, which may consequently impair quality of life [2]. With the progression of therapeutic approaches, systemic inflammation can be swiftly managed. Nevertheless, subclinical vascular inflammation and the ensuing arterial remodeling continue to present unresolved challenges in TAK.

Under pathological environments, inflammatory cells and vascular cells participate in vascular remodeling, leading to the thickening of vascular walls, narrowing of lumens and appearance of aneurysms [3, 4]. The prevailing hypothesis, widely acknowledged within the immunological community, posits that the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the vascular wall originates from the adventitial vasa vasorum and mediates both the inflammatory insult and tissue remodeling in LVV [5, 6]. Given that the inflammatory lesions in TAK are confined to large blood vessels, it is plausible to hypothesize that vascular cells may function as local instigators or enhancers of the inflammatory and autoimmune processes within the vascular lesions. Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) are the principal cellular elements of the arterial system, exhibiting considerable functional plasticity [7]. Importantly, VSMC can dedifferentiate from a contractile state into a synthetic phenotype in several pathological conditions. The phenotypic switching of VSMC is regarded as the first step in vascular pathology and has been identified as playing a critical role in intimal remodeling and various cardiovascular diseases [8, 9]. Therefore, targeting the phenotypic switching of VSMC may serve to alleviate persistent subclinical vascular inflammation and vascular remodeling in TAK.

In TAK, along with inflammatory cells infiltrating into the vessel wall from adventitial vasa vasorum, a broad spectrum of molecules involving cytokines, chemokines and small extracellular vesicles from the periphery participate in the regulation of VSMC [10]. Exosomes, a subset of extracellular vesicles, facilitate the transfer and exchange of proteins and specific nucleic acids between cells and tissues. They contribute to numerous pathophysiological processes and are currently utilized as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic approaches in various diseases [11, 12]. In TAK, however, the potential role of serum exosomes in the pathogenesis of vessel damage, remains uncertain. In this study, we investigated the possibility of exosomes serving as promising and reliable biomarkers in patients with TAK, along with its potential role in vascular remodeling and associated mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

Thirty patients and thirty healthy individuals were enrolled from October 2023 to January 2024 in this study (Supplementary Table 1). Patients diagnosed with TAK were recruited from the department of rheumatology and clinical immunology in Peking Union Medical College Hospital. All patients were diagnosed according to the American College of Rheumatology criteria 1990 for Takayasu’s arteritis [13]. The disease activity of TAK was defined by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria ≥ 2 points [14]. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (Approval S-478) and conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. All individuals involved in this study provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Cell culture and transfection

Immortalized human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells (Meisen Chinese Tissue Culture Collections, China) were maintained in smooth muscle cell medium (ScienCell, Carlsbad, USA). The human embryonic kidney epithelial cell line HEK 293T (Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology of Chinese Academy of Sciences, China) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (NCM biotech, Suzhou, China). The cell lines were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) used in cell culturing was purchased from Bio-Channel (Bio-Channel, China).

For the transfection process, the VSMC were transfected with miR-199a-5p mimics or a miR-199a-5p inhibitor, as well as corresponding scrambled controls (Sangon Biotech, China) using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) based on the manufacturer’s instructions. VSMC were incubated in 6-well plates and subjected to transfection at 70% confluency. After 24 h of transfection, the media was changed and continued to cultivate for 24 h. The efficiency of mimic and inhibitor transfection was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Rno-miR-199a-5p mimics:

5′-CCCAGUGUUCAGACUACCUGUUC-3′,

5′-ACAGGUAGUCUGAACACUGGGUU-3′.

Mimic negative control:

5′-UUGUACUACACAAAAGUACUG-3′,

5′-GUACUUUUGUGUAGUACAAUU-3′.

Rno-miR-199a-5p inhibitor: 5′-(mG)(mA)(mA)(mC)(mA)(mG)(mG)(mU)(mA)(mG)(mU)(mC)(mU)(mG)(mA)(mA)(mC)(mA)(mC)(mU)(mG)(mG)(mG)-3′.

Inhibitor control: 5′-CAGUACUUUUGUGUAGUACAA-3′.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Blood samples were obtained from individuals with TAK and healthy controls utilizing coagulation-promoting tubes. Subsequent to centrifugation at 1800×g for a duration of 10 min, the supernatant was meticulously collected. The derived serum was then conserved at a temperature of -80℃ for future analytical purposes. The concentrations of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP2) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (TIMP2) within the serum were measured utilizing Human MMP-2 ELISA Kit (MULTI SCIENCES BIOTECH, China) and Human TIMP-2 ELISA Kit (MULTI SCIENCES BIOTECH, China), in strict adherence to the stipulated manufacturer’s protocol. For the quantification of TIMP2, the serum was diluted at a ratio of 1:5 using assay buffer. Absorbance measurements were conducted with a microplate reader (Biotek SynergyNeo2). The ultimate concentrations were deduced from standard curves. Disparities between the cohorts were evaluated employing a paired or unpaired Student’s t-test, depending on the contextual appropriateness of the comparison.

Total exosome isolation

Exosomes present in the serum were extracted utilizing Exosome Isolation and Purification Kit (Umibio, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified exosomes were from serum validated utilizing transmission electron microscope (TEM) and immunoblotting for markers such as calnexin, CD63, CD9, and TSG101. The dimensions and abundance of the purified exosomes were evaluated by NanoFCM N30E (NanoFCM, China).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

The total RNA of transfected cells was extracted using RNA simple Total RNA Kit (TIANGEN BIOTECH, China) and quantified by NanoDrop One ultra-micro UV spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The reverse transcription of total RNA into cDNA was performed using PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit (Perfect Real Time) (Takara Bio, Japan). qRT-PCR was performed on a C1000 Thermal Cycler CFX96 Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) using BeyoFast™ SYBR Green qPCR Mix (2X) (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). The isolation of miRNA was conducted utilizing miRcute miRNA Isolation Kit (Tiangen, China). The quantitative expression levels of miR-199a-5p were ascertained through the application of qPCR, facilitated by the Hifair® miRNA 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Yeasen Biotechnology, China) and Hieff® miRNA UniversalqPCR SYBR Master Mix (Yeasen Biotechnology, China). These procedures were executed in strict accordance with the stipulated instructions provided by the manufacturer. The primer sequences used are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The thermocycler conditions were as follows: 37 °C for 30 s; 95 °C for 15 min; followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s; 55 °C for 30 s; and 72 °C for 30 s. The relative expression of target genes was calculated by the 2 − ΔΔCq method.

Western blot analysis

The transfected cells at approximately 95% confluence were used for protein extraction. Total proteins were extracted by Radio Immunoprecipitation Assay lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and separated by 4–20% SDS-PAGE (ACE Biotechnology, Changzhou, China), and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked with TBST containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and then incubated with primary antibodies at 4 ℃ overnight. After incubation with secondary antibodies for 1 h, the PVDF membranes were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence system kit (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), and the relative protein expression levels were analyzed by ImageJ. The primary antibodies and secondary antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Cell proliferation assays and cell migration assay

The proliferative activity of VSMC was evaluated employing 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) Apollo Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) or Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8; APExBIO, USA). For the EdU assay, the transfected cells were seeded onto a 24-well plate at a density of 1 × 10^5 cells per well. The subsequent procedures were executed in strict accordance with the stipulated instructions provided by the manufacturer. The detection process was facilitated using a fluorescence microscope (IX-73, OLYMPUS, Japan). For the CCK8 assay, the transfected cells were seeded onto a 96-well plate at a cellular density of 1 × 10^3 cells per well, establishing four replicative wells for each experimental group. At designated time points—0 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 96 h—10 µl of CCK8 solution was incorporated into each well. Post-incubation for 2 h at 37 °C, absorbance measurements were acquired at a wavelength of 450 nm utilizing a microplate reader (ELX800, BioTek, USA).

The scratch assays and the migration assay were performed to assess cell migration. The transfected VSMC were incubated in a 6-well dish and a scratch lesion was introduced across the confluent cell monolayer using a 10 µL pipette tip. Images of the scratched area were captured at 0 h, 24 h and 48 h utilizing an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX51, Japan). The migration ability of transfected VSMC was determined using the formula (S0 - St)/ S0, where S0 represents the initial wound area at 0 h, and St corresponds to the wound area at either the 24-hour or 48-hour time point. For the migration assay, a suspension of transfected VSMC was introduced into the upper chamber of a 24-well Transwell plate that contained an 8-µm pored membrane filter (Corning, USA). Following a 48-hour incubation period, cells that had migrated to the lower surface of the Transwell chamber were immobilized using 4% paraformaldehyde for a duration of 30 min. Subsequently, these cells were stained with 0.05% crystal violet for a period of 10 min and subsequently examined under a microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis

The frequency of apoptosis in VSMC was assessed using Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (Beyotime, China). The transfected VSMC were rinsed twice with PBS. This was followed by the addition of 1× Binding buffer to obtain a cell concentration of 1 × 10^6 cells/ml. Propidium iodide was then added in the absence of light. After an incubation period of 30 min in an ice bath protected from light, VSMC were instantly subjected to flow cytometer (BD FACSCalibur, USA).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Cells were seeded onto slides placed at the base of a 24-well plate at a density of 6 × 10^4 cells per well. Prior to the experiment, cell density was adjusted to achieve a confluence of 60–70%. FISH assay was conducted to determine the localization of MMP2 and miR-199a-5p within VSMC. In summary, following a prehybridization step at 37 °C for 35 min, the cell climbing pieces underwent overnight hybridization at 37 °C with 2.5 µL 20 µM FAM-labelled miR-199a-5p probes and Cy3-labelled MMP2 probes (RiboBio, China), followed by staining with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images of the slides were captured using confocal laser scanning microscopy (Zeiss, Germany).

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay

The RIP assays were conducted utilizing the EZ-Magna RNA-binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore, Germany). Following lysis with RIP buffer, VSMC underwent incubation with magnetic beads in conjugation with anti-AGO2 antibodies or immunoglobulin G (Proteintech Group, China). After isolation from the immunoprecipitated protein-RNA complex, the purified RNA underwent quantified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to quantify the expression of MMP2.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

HEK-293 T cells were propagated in 6-well plates a density of 2 × 10^5 cells per well and incubated for a duration of 18 h. Subsequently, HEK-293 T cells underwent co-transfection with MMP2-WT-pmirGLO or MMP2-MUT-pmirGLO reporter plasmids with miR-199a-5p mimics. Dual Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay Kit (Beyotime, China) was employed to measure luciferase activity, with all procedures meticulously adhering to the manufacturer’s prescribed instructions. The relative light units (RLU) of both luciferases were ascertained through biochemical luminescence. Using sea kidney luciferase as an internal reference, the RLU value derived from the firefly luciferase measurement was normalized by dividing it by the RLU value obtained from the sea kidney luciferase measurement. This facilitated the comparison of reporter gene activation levels across different treatments based on the calculated ratios.

Results

Characterization of serum exosomes from TAK patients

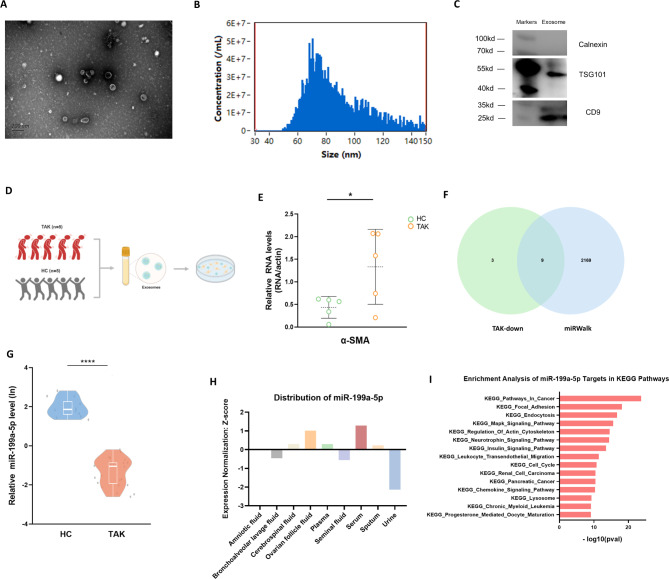

The serum exosomes were meticulously purified from TAK patients and healthy individuals. TEM showed the serum exosomes to exhibit a predominantly cup-shaped or rounded morphology (Fig. 1A). Nanoparticle flow cytometry analysis further elucidated the average particle size of exosomes with an average particle size of approximately 86.9 nanometers (Fig. 1B). In addition, the results from Western blotting indicated that these vesicular structures were characterized by the presence of key exosome markers, including TSG101 and CD9, while lacking the expression of Calnexin, a negative exosomal marker (Fig. 1C). Consequently, these observations unequivocally confirmed the identity of the purified particles as exosomes.

Fig. 1.

The serum exosomes from TAK patients contributed to phenotypic modulation of VSMC. A Transmission electron microscope of serum exosomes from TAK patients. B Nanoparticle flow cytometry analysis showed the average particle size of approximately 86.9 nanometers. C Western blot identified positive expression of exosome markers, including TSG101 and CD9, and negative expression of Calnexin. D The flow chart of VSMC co-cultured with serum exosomes obtained from TAK patients or healthy individuals. E The expression level of α-smooth muscle actin was higher in the co-culture system with serum exosomes from TAK patients analyzed by qRT-PCR. F The intersection of twelve downregulated miRNAs in TAK-derived exosomes with miRNAs related to TAK as catalogued in the miRWalk database. G The qRT-PCR identified the decreased levels of miR-199a-5p in exosomes derived from TAK patients compared to healthy individuals. H The deepBase v3.0 showed the distribution of miR-199a-5p in human exosomes. I The starBase showed the enrichment analysis of miR-199a-5p targets in KEGG. HC: Healthy control; TAK: Takayasu’s arteritis; α-SMA: α-smooth muscle actin; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; qRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. *P ≤ 0.05; ****P ≤ 0.0001

The serum exosomes from TAK patients contributed to phenotypic modulation of VSMC

To investigate the influence of serum exosomes derived from TAK patients on VSMC, we co-cultured immortalized human aortic smooth muscle cells with serum exosomes obtained from five newly-diagnosed TAK patients and five healthy individuals (Fig. 1D). The qRT-PCR analysis suggested the VSMC co-cultured with exosomes from the TAK cohort exhibited higher expression levels of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), a gene of one of the VSMC cytoskeleton protein (Fig. 1E). These findings indicated that serum exosomes played a role in phenotypic modulation of VSMC. MiRNAs, recognized as integral components of exosomes, have been implicated in the regulation of VSMC [15]. To elucidate the mechanisms by which exosome-derived miRNA from TAK patients contributes, we intersected the twelve miRNAs previously identified as downregulated in TAK-derived exosomes [16] with miRNAs related to TAK as cataloged in the miRWalk database [17]. This comparison yielded nine miRNAs as potential candidates for subsequent validation (Fig. 1F). Subsequent qRT-PCR analyses were conducted to quantify the expression of these nine miRNAs (involving miR-1249-3p, miR-141-3p, miR-199a-5p, miR-200a-3p, miR-204-5p, miR-29c-5p, miR-381-3p, miR-4433b-5p and miR-584-5p). Notably, miR-199a-5p exhibited a marked diminution in its expression in TAK patients compared to healthy controls (Fig. 1G). In contrast, the expression profiles of the remaining eight miRNAs did not reveal any significant differences between the TAK and healthy groups (Figure S1).

Furthermore, we interrogated potential functionalities of miR-199a-5p through various databases. Utilizing deepBase v3.0 [18], a comprehensive database detailing human exosome RNA expression profiles, we observed that miR-199a-5p expression levels were predominantly elevated in serum (Fig. 1H). This finding suggests that serum exosomes are the principal conduits for miR-199a-5p activity. Additionally, we performed an enrichment analysis of miR-199a-5p based on microRNA-target interactions using starBase [19] Significantly, among the top 15 pertinent pathways identified in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton was prominently featured (Fig. 1I), aligning with the results depicted in Fig. 1E. In summary, serum exosomes derived from TAK patients may play a pivotal role in modulating VSMC phenotype.

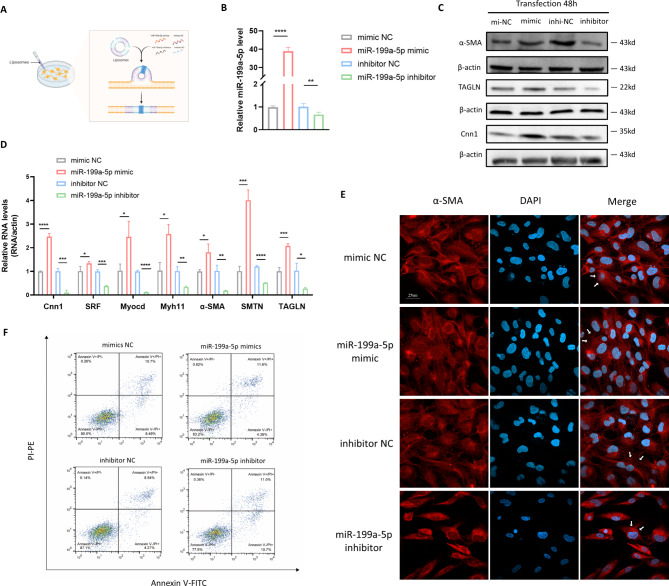

The overexpression of miR-199a-5p induced dedifferentiation of VSMC from a contractile into a synthetic phenotype

In order to investigate the hypothesis that miR-199a-5p influences VSMC phenotype transition, we transfected VSMC with either miR-199a-5p mimics or miR-199a-5p inhibitors, and subsequently subjected these transfected cells to a series of analyses (Fig. 2A). The qRT-PCR results revealed a significant upregulation of miR-199a-5p expression in VSMCs treated with miR-199a-5p mimics, and a downregulation in those treated with the miR-199a-5p inhibitor (Fig. 2B), confirming the efficacy of the transfection process. Overexpression of miR-199a-5p induced cytoskeletal reorganization in VSMC, as evidenced by an increased amount of cells exhibiting well-defined α-SMA stress fibers (Fig. 2E). These morphological changes strongly imply that miR-199a-5p modulates the differentiation state of VSMC. Further analysis of VSMC differentiation markers, including Calponin 1 (Cnn1), α-SMA and Transgelin (TAGLN) through western blotting (Fig. 2C, Figure S2) and RT-qPCR (Fig. 2D) corroborated this hypothesis. Additionally, other genes pivotal for VSMC differentiation, such as Myosin Heavy Chain 11 (Myh11), Serum Response Factor (SRF), Myocardin (Myocd) and Smoothelin (SMTN), also exhibited significant upregulation (Fig. 2D). These data suggested that the overexpression of miR-199a-5p induced dedifferentiation of VSMC from a contractile state into a synthetic phenotype.

Fig. 2.

MiR-199a-5p modulated VSMC differentiation and apoptosis. A The flow chart of transfection process of VSMC with miR-199a-5p mimic, miR-199a-5p inhibitor and corresponding controls. B The qRT-PCR identified the successful transfection of miR-199a-5p mimic or inhibitor. C Western blotting identified that miR-199a-5p mimic enhanced the expression of synthetic phenotype markers, and miR-199a-5p inhibitor decreased the expression of synthetic phenotype markers (α-SMA, TAGLN and Cnn1). D The qRT-PCR identified miR-199a-5p mimic enhanced the expression of synthetic phenotype markers of VSMC, and miR-199a-5p inhibitor decreased the expression of synthetic phenotype markers (α-SMA, TAGLN, SRF, Myocd, Myh11, SMTN and Cnn1). E Staining of VSMC transfected with miR-199a-5p mimic and inhibitor for α-SMA stress fibers (indicated by white arrow) and DAPI (Representative images chosen for similarity; Scale bar: 25 μm). F Flow cytometric analysis showed VSMC transfected with miR-199a-5p mimic exhibited an increased level of apoptosis relative to negative control, and VSMC transfected with miR-199a-5p inhibitor showed increased level of apoptosis relative to negative control. α-SMA: α-smooth muscle actin; TAGLN: Transgelin; Cnn1: Calponin 1; SRF: Serum Response Factor; Myocd: Myocardin; Myh11: Myosin Heavy Chain 11; SMTN: Smoothelin; DAPI: 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; NC: negative control; qRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P < 0.0001

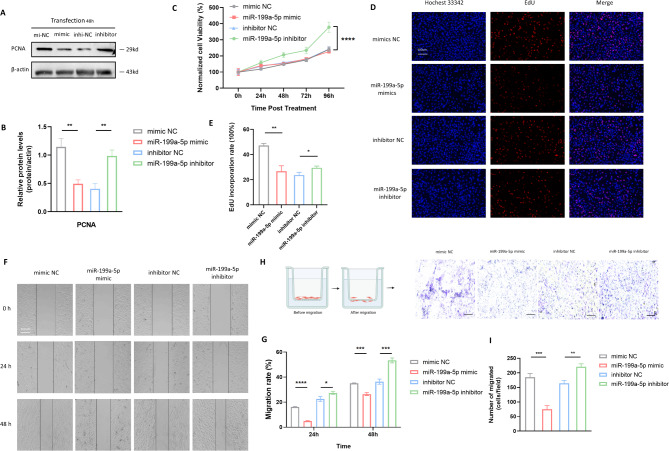

The overexpression of miR-199a-5p inhibits the proliferation and migration of VSMC

The proliferation and migration of VSMC are pivotal in intimal remodeling of the artery wall. Thus, we undertook a comprehensive investigation into the influence of miR-199a-5p on VSMC proliferative and migratory function. Western blot analysis disclosed a diminished expression of Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) in VSMC upon miR-199a-5p overexpression, whereas there was an elevated PCNA level in the miR-199a-5p inhibitor group (Fig. 3A and B). In CCK8 assays, the knockout of miR-199a-5p VSMC exhibited increased cell viability compared to negative control (Fig. 3C), suggesting the inhibitory capacity of miR-199a-5p mimics. In a consistent manner, EdU incorporation assays revealed that miR-199a-5p negatively regulates cell proliferation. Beyond the realm of VSMC proliferation, miR-199a-5p overexpression notably impeded VSMC migration, as evidenced by scratch assays (Fig. 3F and G) and transwell migration assays (Fig. 3H and I). In summation, these results substantiate the prospective role of miR-199a-5p as a therapeutic target for mitigating the degradation of arterial wall integrity.

Fig. 3.

MiR-199a-5p modulated VSMC proliferation and migration. A Western blotting identified that miR-199a-5p mimic reduced the expression of PCNA, and miR-199a-5p inhibitor increased the expression of PCNA. B Statistical analysis of western blotting results. C CCK8 assays showed that VSMC with miR-199a-5p knocked out exhibited increased cell viability compared to negative control. D Staining of VSMC transfected with miR-199a-5p mimic and inhibitor, and corresponding controls for Hoechst 33342 and EdU (Representative images chosen for similarity; Scale bar: 25µm). E Statistical analysis of EdU results showed significantly decreased incorporation rate of VSMC transfected with miR-199a-5p mimic, and increased incorporation rate of VSMC transfected with miR-199a-5p inhibitor. F Images of the scratch assays captured at 0 hour, 24 hours and 48 hours. G Statistical analysis of scratch assays revealed that miR-199a-5p overexpression notably impeded VSMC migration, whereas miR-199a-5p knockout promoted it. H The flow chart of transwell migration assays and the images after migration. I Statistical analysis of transwell migration assays showed that miR-199a-5p overexpression suppressed VSMC migration, and the knockout of miR-199a-5p prompted VSMC migration. All statistical analyses mentioned above represented the average (mean ± Standard Error of the Mean) derived from three separate experiments. PCNA: Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen; NC: negative control; qRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; EdU: 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P < 0.0001

The apoptosis of VSMC is inhibited by miR-199a-5p mimics

Beyond VSMC migration and proliferation, the reduction in VSMC within the aorta’s medial layer, resulting from apoptosis, serves as an initial warning sign of aortic aneurysm formation [20]. Besides, aortic aneurysms serve as a severe complication associated with TAK and intimately linked to theunfavorable prognosis of the disease. Therefore, we explored the potential roles of miR-199a-5p in modulating VSMC apoptosis. Results from flow cytometry revealed that the proportions of apoptotic VSMC were greatly reduced upon miR-199a-5p overexpression, whereas there was an elevated apoptotic level in the miR-199a-5p inhibitor group (Fig. 2F). These findings suggest that miR-199a-5p may mitigate aneurysm formation by suppressing VSMC apoptosis.

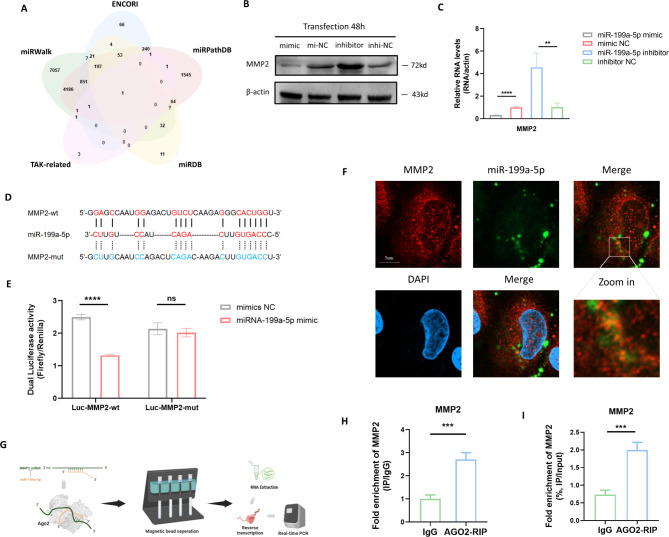

MMP2 serves as a functional target gene of miR-199a-5p

The above results showed the important role of miR-199a-5p in vascular remodeling, while what is the underlying mechanism of miR-199a-5p remains unclear. To further investigate how miR-199a-5p functions, nine genes in common related to TAK were first collected from the four databases, CTD, GENE, DisGeNET and GeneCards (Figure S3A). Next, four miRNA target prediction databases, including miRWalk, ENCORI, miRPathDB and miRDB, were used to intersect with the TAK-related genes (Fig. 4A) and MMP2 was ultimately analyzed as the sole target gene of miR-199a-5p. For the validation of the predicting result, the transcriptional level (Fig. 4B) and protein expression level (Fig. 4C, S3B) of MMP2 were measured after overexpression and inhibition of miR-199a-5p, which showed that miR-199a-5p significantly restrained the expression of MMP2 at the transcriptional and protein levels. To further clarify the specific binding sites of MMP2, the binding region and binding sites were predicted by the ENCORI database and then the plasmids for the dual luciferase assay were designed (Fig. 4D). After co-transfecting Luc-MMP2-wt and Luc-MMP2-mut with miR-199a-5p mimics in HEK293T cells, the dual luciferase reporter assays revealed that the luciferase activity decreased after co-transfecting Luc-MMP2-wt with miR-199a-5p mimics (Fig. 4E), while the luciferase activity did not change (with no statistical significance) in the cells co-transfected with Luc-MMP2-mut and miR-199a-5p mimics. The results indicated the binding between MMP2 and miR-199a-5p. Furthermore, the binding relationship was also validated by confocal microscopy analysis. The FISH assay was used to display the location of the MMP2 mRNA (FISH probe labeled with CY5) and FAM-labeled miR-199a-5p was transfected into the VSMC cells. Imaged by the confocal microscopy, it is shown that miR-199a-5p bound to MMP2 mRNA (the yellow points) in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5F). AGO2, the key regulator for the competing endogenous RNA regulation, recognizes and degrades the miRNA binding complex [21]. In the present study, the AGO2 recognition of miRNA binding complex containing MMP2 was also measured by AGO2-RIP (Fig. 5G), which showed that MMP2 mRNA enriched in the AGO2-beads (Fig. 5H-I). The results indicated that after the binding of miR-199a-5p and MMP2 mRNA, AGO2 recognized the binding complex and eventually led to the degradation of MMP2 mRNA, which elucidated the entire regulatory process of miR-199a-5p on MMP2. Taken together, the present study revealed the binding and relevant regulatory modes of miR-199a-5p and MMP2 mRNA for the first time in TAK.

Fig. 4.

MMP2 serve as functional target gene of miR-199a-5p. A The intersection of miRWalk, ENCORI, miRPathDB and miRDB to predict miR-199a-5p targets. B-C Western blotting and qRT-PCR validated of the predicted results that miR-199a-5p significantly restrained the expression of MMP2 at transcription and protein expression level. D The binding sites of MMP2 were predicted by the ENCORI database and the plasmids for the dual luciferase assay were designed. E The dual luciferase reporter assays revealed that the luciferase activity decreased after co-transfecting Luc-MMP2-wt with miR-199a-5p mimics. F The Image utilizing the confocal microscopy showed the binding of miR-199a-5p to MMP2 mRNA (the yellow points) in the cytoplasm. G The AGO2 recognition of miRNA binding complex containing MMP2 was measured by AGO2-RIP. H-I MMP2 mRNA was enriched in the AGO2-beads. MMP2: matrix metalloproteinase-2; NC: negative control; DAPI: 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; qRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. ns: P > 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P < 0.0001

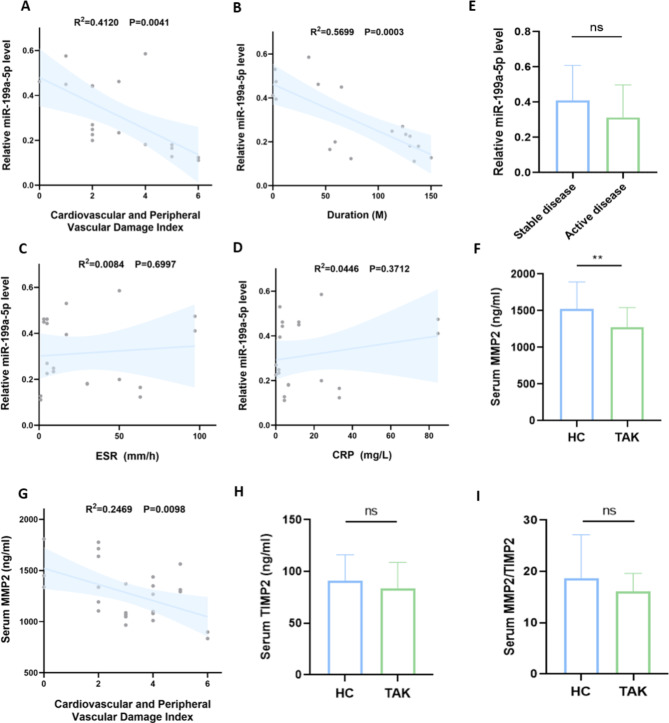

Fig. 5.

Clinical relevance analysis of exosome miR-199a-5p, serum MMP2 and TIMP2. A-D Correlation analysis of exosome miR-199a-5p and cardiovascular and peripheral vascular damage index, disease duration, ESR and CRP levels respectively. The cardiovascular and peripheral vascular damage index refers to the score of vascular-related events including cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disease in VDI. E Levels of exosome miR-199a-5p between active and stable groups showed no significant difference. F Levels of serum MMP2 in TAK patients were significantly lower than that in healthy controls. G Correlation analysis of serum MMP2 and cardiovascular and peripheral vascular damage index. H Levels of serum TIMP2 between TAK patients and healthy controls showed no significant difference. I The ratio of MMP2/TIM2 level between TAK patients and healthy controls showed no significant difference. All correlation analyses mentioned above were assessed using Spearman’s correlation analysis. Vasculitis Damage Index: VDI; TAK: Takayasu’s arteritis; HC: healthy control; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; MMP2: matrix metalloproteinase-2; TIMP2: tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2. ns: P > 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01

Exosome miR-199a-5p and serum MMP2 serve as vascular damage biomarkers in TAK

We have previously elucidated that exosome miR-199a-5p is downregulated in TAK and involved in the process of vascular injury and remodeling. Given that TAK is a form of idiopathic inflammatory disorder marked by vascular fibrosis, it is postulated that serum miR-199a-5p potentially serve as a marker for overall fibrotic activity. To explore this hypothesis, we performed a correlation analysis between miR-199a-5p levels and clinical indicators of vascular damage. Vasculitis damage index (VDI) is a standardized indicator for monitoring organ damage caused by vasculitis and treatment-related toxicity in ANCA-associated vasculitis [22]. After excluding treatment-related drug toxicity, we used the score of vascular-related events including cardiovascular damage and peripheral vascular disease in VDI to evaluate the vascular damage in TAK. Our findings revealed an inverse correlation between the relative exosome miR-199a-5p level and the cardiovascular and peripheral vascular damage index (R2 = 0.4120, P = 0.0041; Fig. 5A), suggesting that exosome miR-199a-5p might be utilized as a biomarker for vasculitis damage in TAK. Consistently, we observed an inverse relationship between exosome miR-199a-5p level and the duration of the disease (R2 = 0.5699, P = 0.0003; Fig. 5B). The chronicity of the disease can partially reflect the repair and fibrotic processes associated with vasculitis. Patients were stratified into stable and active cohorts based on disease activity. Notably, there was no significant disparity in the relative miR-199a-5p levels between these two groups (P = 0.2436, Fig. 5E). Furthermore, no discernible correlations were found between the exosome miR-199a-5p level and the ESR (R2 = 0.0084, P = 0.6997; Fig. 5C) or CRP (R2 = 0.0446, P = 0.3712; Fig. 5D). These findings indicate that exosome miR-199a-5p is not intimately associated with systemic inflammatory responses.

We have elucidated the potential role of MMP2 as a miRNA target at the tissue level. Given that several studies have reported dysregulation of serum MMPs, we proceeded to verify the levels of serum MMP2 and TIMP2 in our cohort. While no significant disparity in MMP2 levels was discerned between patients with active and inactive disease states (P = 0.8690, Figure S4), serum MMP2 levels were notably diminished in TAK patients relative to healthy controls (P = 0.0072, Fig. 5F). Furthermore, the serum concentration of MMP2 exhibited a negative correlation with cardiovascular and peripheral vascular damage index (R2 = 0.2469, P = 0.0098; Fig. 5G). In addition, the precise role of TIMP-2, an inherent suppressor of MMP2’s proteolytic functions, remains contentious in the context of TAK. Our findings suggest that no significant variance exists in serum TIMP2 levels (P = 0.3044, Fig. 5H) and MMP2/TIMP2 equilibrium (P = 0.1630, Fig. 5I) between TAK patients and healthy subjects.

Discussion

TAK is characterized by granulomatous inflammation of uncertain origin that impacts large and medium arteries. Despite advances in treatment that swiftly alleviate systemic inflammation, challenges like arterial stenosis and aneurysmal dilatation remain unaddressed [23]. These persistent obstructive lesions can block the artery. Significantly, the phenotypic switching of VSMC plays a crucial role in the development of TAK, as VSMC adopt proliferative and migratory properties upon transitioning to a synthetic phenotype, thereby contributing to vascular remodeling.

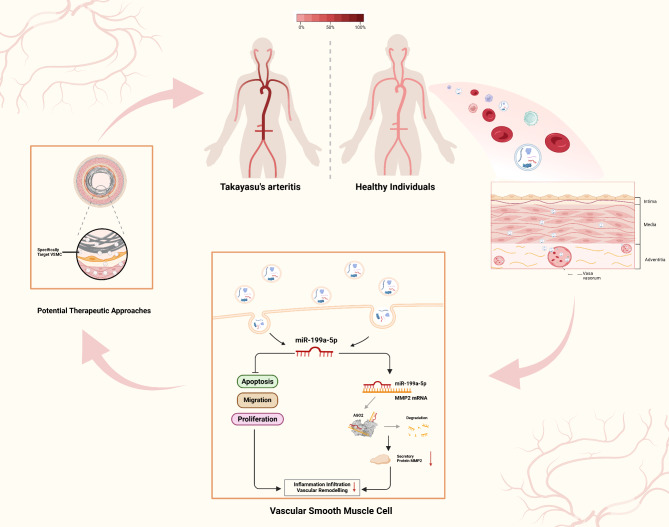

In our investigation, we elucidated the potential function of exosome miR-199a-5p in vascular remodeling and its related mechanisms (Fig. 6). Within particular disease models, the administration of extracellular vesicles suppressed proliferative and migration abilities of VSMC, as well as neointima formation [24–27]. Our study demonstrated that a decrease in miR-199a-5p in serum-derived exosomes induced the dedifferentiation of VSMC, while the absence of miR-199a-5p facilitated proliferation and migration of VSMC. The observations regarding miR-199a-5p align with those of earlier research, which indicated that miR-199a-5p suppression enhances tumor cell proliferation and motility [28, 29]. In contrast, prior studies have shown elevated levels of miR-199a-5p might enhance cellular proliferation and metastasis via targeting PIAS3 in cervical cancer [30], while the downregulation of miR-199a-5p has been found to impede osteoblast differentiation by targeting TET2 [31]. The results suggest that the role of miR-199a-5p is context-dependent, varying with the specific cell type and molecular targets involved.

Fig. 6.

Mechanism of exosomal miR-199a-5p in maintaining normal vascular morphology and function and the potential therapeutic approaches in Takayasu’s arteritis

Another intriguing facet of miR-199a-5p’s impact on VSMC pertains to its role in apoptosis regulation. Aortic aneurysm, a grave complication associated with TAK, can manifest at various locations along the aorta [32]. Typically, aneurysms arise from the swift or intense inflammation that leads to the depletion of VSMC and the degradation of the medial layer in TAK. In our investigation, miR-199a-5p exhibited a potential to suppress VSMC apoptosis relative to the negative control group. This strategy of targeting VSMC presents a promising avenue for mitigating aneurysm development.

In our mechanistic investigation, we have ascertained that MMP2 serves as the authentic downstream target of miR-199a-5p during phenotypic transition in VSMC. MMP2, recognized as type II collagenase, is categorized within the zinc-dependent metalloendopeptidase family, which is instrumental in the degradation or cleavage of the extracellular matrix (ECM). From a physiological perspective, it has been demonstrated that activated MMP2 can induce myofibroblasts and augment the influx of monocytes/macrophages, thereby causing oxidative stress, inflammation, and concomitant vascular wall damage [33]. The overproduction of MMP2 is associated with various vascular pathologies. For instance, within the basal membrane of atherosclerotic plaques, MMP2-mediated degradation facilitates the recruitment of inflammatory cells and the fragmentation of the fibrous cap; events that precipitate plaque instability and eventual rupture [34]. In giant cell arteritis, the activities such as infiltration of vasculogenic T cells and monocytes, formation of new angiogenic networks, and growth of the neointima, all hinge on the enzymatic function of MMP9. This underscores the significant role the MMP family plays in vasculitis. In the context of TAK, it has been documented that MMP2 co-expresses with a glycoprotein known as non-metastatic melanoma protein B, which is implicated in ECM production [34]. Our study revealed that treatment with miR-199a‐5p mimics notably attenuated MMP2 expression in VSMC. The diminished secretion of MMP2 at the tissue level could potentially hinder the intimal infiltration of inflammatory cells within the vascular wall.

Arterial surgeries continue to be a crucial intervention in TAK, particularly when medical therapy fails or to address severe vascular damage consequences. While the 15-year survival rate has seen an improvement from 43 to 67.5% with surgical intervention [35], stent implantation-induced vascular injury consistently results in restenosis due to uncontrolled VSMC proliferation and migration. The rapid and inevitable infiltration of various inflammatory cells into the neointima and surrounding the stent follows stent implantation. Recent studies have highlighted the elevated rates of restenosis and recurrence following stent procedures in patients with TAK [36–39]. Literature on the application of drug-eluting stents in TAK is scarce. Furthermore, VSMC constitute a significant portion of neointimal tissue following stenting or arterial injury, a finding substantiated in mouse models [24]. Our research suggested that miR-199a-5p within exosomes exhibited potential as a therapeutic strategy in TAK by tackling both inflammatory responses and the neointimal overgrowth associated with TAK arterial trauma. Our research may lay the groundwork for therapeutic strategies in TAK utilizing drug-eluting stents that target VSMC, specifically for occlusive and proliferative arterial progression. The discovery that the miR-199a-5p/MMP2 signaling axis plays a crucial role in VSMC phenotypic modulation and arterial remodeling could provide a mechanistic rationale for its positive impact on in-stent restenosis. This implies that addressing the abnormal regulation of miR-199a-5p in TAK-associated exosomes via targeted delivery of miR-199a-5p mimics to the vessels with stents using techniques such as miR-199a-5p-coated balloons or stents, or ultrasound-stimulated nanodelivery, could potentially suppress or minimize in-stent restenosis in TAK patients.

In our study, we identified a novel role of exosome miR-199a-5p as a promising and reliable biomarkers for vasculitis damage in TAK. Despite clinically dormant disease, the angiographic severity of TAK may escalate during the whole progression of disease. Currently, no clinically verified monitors of damage that might indicate arterial fibrosis exist in TAK [40]. Work carried out recently demonstrated that the augmented liver fibrosis score is moderately associated with VDI and Takayasu Arteritis Damage Score, and it is strongly linked to angiographically evaluated vascular damage utilizing the Combined Arteritis Damage Score in 24 TAK patients [41]. Our research findings indicated that a reduction in exosome miR-199a-5p suggested a worsening of vascular injury rather than systemic inflammation in TAK patients. Another intriguing observation was the inverse correlation between exosome miR-199a-5p levels and the duration of the disease. The chronicity of the disease may partially reflect the repair and fibrotic processes associated with vasculitis. In addition, we evaluated the expression of MMP2 and TIMP2 at the serological level. Contrary to the increased expression of MMP2 at the histological level, the serum level of MMP2 was significantly downregulated in our TAK cohort compared to healthy individuals, exhibiting a negative correlation with vascular injury. In a consistent manner, an observation reported decreased levels of MMP2 in TAK patients, and an augment in MMP2 levels has been related to disease improvement [42]. These insights suggested that the serum concentration of MMP2 could potentially function as a valuable biomarker for gauging disease improvement and inhibiting vascular damage or fibrosis. However, several studies have reported conflicting results, involving high levels of MMP2 in TAK [43] and no significance of MMP2 levels between TAK patients and healthy controls [44]. The discrepancies in these results may be attributed to small sample sizes, ethnic differences, and variations in ELISA detection methods. Further validation of the serological level of MMP2 and its association with disease activity and vascular injury is required in a larger cohort.

Our research has certain limitations that must be addressed. Firstly, our findings are derived from in vitro experiments due to the absence of a suitable animal model in TAK [6]. The contribution of miR-199a-5p deficiency in exosomes to vascular injury through the regulation of VSMC phenotype transition necessitates further verification within an animal model. Secondly, aside from MMP2, the potential mediation of the VSMC phenotype transition by miR-199a-5p through other molecular targets requires exploration in forthcoming studies. Thirdly, it remains unproven whether miR-199a‐5p can induce injury in alternative cell types, such as endothelial cells and fibroblasts, thereby exacerbating arterial injury in TAK.

In conclusion, our study indicated that the miR-199a-5p/MMP2 pathway played a role in inhibiting the migration, proliferation, and apoptosis of VSMC. The decreased secretion of MMP2 may prompt the intimal infiltration of inflammatory cells within the vascular wall, offering a novel therapeutic opportunity by tackling both inflammatory responses and the neointimal overgrowth associated with TAK arterial damage. Notably, exosome miR-199a-5p and MMP2 derived from serum possessed potential as future biomarkers for vascular injury, which require validation in a larger cohort. The discovery of exosome miR-199a-5p presents novel therapeutic opportunities for TAK, targeting both arterial wall inflammation and vascular remodeling in future treatments.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- α-SMA

α-smooth muscle actin

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- CCK8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- Cnn1

Calponin 1

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- EdU

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

- FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LVV

Large-vessel vasculitis

- MMP2

Matrix metalloproteinase-2

- Myh11

Myosin Heavy Chain 11

- Myocd

Myocardin

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- PCNA

Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen

- PVDF

Polyvinylidene Fluoride

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RLU

Relative light units

- RIP

RNA immunoprecipitation

- SMTN

Smoothelin

- SRF

Serum Response Factor

- TAGLN

Transgelin

- TAK

Takayasu’s arteritis

- TEM

Transmission electron microscope

- TIMP2

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2

- VDI

Vasculitis Damage Index

- VSMC

Vascular smooth muscle cells

Author contributions

S.G. and JH.L. conceived the study and completed the main experiments, S.G. wrote the main manuscript text. J.L., S.P. and X.T. critically revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding

This study was supported by CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2021-I2M-1-005), National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-A-006, 2022-PUMCH-B-013 and 2022-PUMCH-C-068).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Consent for publication

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study of human sample was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (S-478) and complied with all relevant ethical guidelines. The informed consent forms of the subjects have been obtained.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shuning Guo and Jiehan Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jing Li, Email: lijing6515@pumch.cn.

Xinping Tian, Email: tianxp6@126.com.

References

- 1.Zaldivar Villon MLF, de la Rocha JAL, Espinoza LR. Takayasu Arteritis: Recent Developments. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2019;21:45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Rimland CA et al. Outcome Measures in Large Vessel Vasculitis: Relationship Between Patient-, Physician-, Imaging-, and Laboratory-Based Assessments. Arthr Care Res. 2020;72:1296–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Méndez-Barbero N, Gutiérrez-Muñoz C, Blanco-Colio LM. Cellular Crosstalk between Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cells in Vascular Wall Remodeling. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Lamplugh Z, Fan Y. Vascular Microenvironment, Tumor Immunity and Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2021;12:811485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Watanabe R, Hashimoto M. Pathogenic role of monocytes/macrophages in large vessel vasculitis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:859502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Chu CQ. Animal models for large vessel vasculitis - The unmet need. Rheumatol Immunol Res. 2023;4:4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Frismantiene A, Philippova M, Erne P, Resink TJ. Smooth muscle cell-driven vascular diseases and molecular mechanisms of VSMC plasticity. Cell Signal. 2018;52:48–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Miano JM, Fisher EA, Majesky MW. Fate and State of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2021;143:2110–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Petsophonsakul P et al. Role of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotypic Switching and Calcification in Aortic Aneurysm Formation. Arterioscler, Thromb Vas Biol. 2019;39:1351–1368. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Pugh D et al. Large-vessel vasculitis. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2022;7:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Yao J et al. Exosomes: mediators regulating the phenotypic transition of vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Cell Commun Signal: CCS. 2022;20:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Yang B, Chen Y, Shi J. Exosome Biochemistry and Advanced Nanotechnology for Next-Generation Theranostic Platforms. Adv Mat (Deerfield Beach, Fla.). 2019;31:e1802896. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Arend WP et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthr Rheum. 1990;33:1129–1134. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kerr GS et al. Takayasu arteritis. Annals Int Med. 1994;120:919–929. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Wang G et al. MicroRNA regulation of phenotypic transformations in vascular smooth muscle: relevance to vascular remodeling. Cell Mole Life Sci: CMLS. 2023;80:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Huang BQ, Li J, Tian XP, Zeng XF. Analysis of differentially expressed microRNA and protein expression profiles carried by exosomes in the plasma of patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2023;62:61–69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Sticht C, De La Torre C, Parveen A, Gretz N. miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA binding sites. PloS one. 2018;13:e0206239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Xie F et al. deepBase v3.0: expression atlas and interactive analysis of ncRNAs from thousands of deep-sequencing data. Nucl Acid Res. 2021;49:D877-d883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Li JH, Liu S, Zhou H, Qu LH, Yang JH. starBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucl Acid Res. 2014;42:D92-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Rombouts KB et al. The role of vascular smooth muscle cells in the development of aortic aneurysms and dissections. Europ J Clin Invest. 2022;52:e13697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Nakanishi K. Anatomy of four human Argonaute proteins. Nucl Acid Res. 2022;50:6618–6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Kronbichler A, Bajema IM, Bruchfeld A, Mastroianni Kirsztajn G, Stone JH. Diagnosis and management of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Lancet (London, England). 2024;403:683–698. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Keser G, Aksu K, Direskeneli H. Discrepancies between vascular and systemic inflammation in large vessel vasculitis: an important problem revisited. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2018;57:784–790. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Yan W et al. M2 macrophage-derived exosomes promote the c-KIT phenotype of vascular smooth muscle cells during vascular tissue repair after intravascular stent implantation. Theranostics. 2020;10:10712–10728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Wang D et al. Exosomes from mesenchymal stem cells expressing miR-125b inhibit neointimal hyperplasia via myosin IE. J Cell Mole Med. 2019;23:1528–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Li X, Ballantyne LL, Yu Y, Funk CD. Perivascular adipose tissue-derived extracellular vesicle miR-221-3p mediates vascular remodeling. FASEB J: Ffficial publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2019;33:12704–12722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Sharma H et al. Macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles mediate smooth muscle hyperplasia: role of altered miRNA cargo in response to HIV infection and substance abuse. FASEB J: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2018;32:5174–5185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Ahmadi A, Khansarinejad B, Hosseinkhani S, Ghanei M, Mowla SJ. miR-199a-5p and miR-495 target GRP78 within UPR pathway of lung cancer. Gene. 2017;620:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Ma S, Jia W, Ni S. miR-199a-5p inhibits the progression of papillary thyroid carcinoma by targeting SNAI1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;497:181–186. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Qu D, Yang Y, Huang X. miR-199a-5p promotes proliferation and metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition through targeting PIAS3 in cervical carcinoma. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:13562–13572. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Qi XB et al. Role of miR-199a-5p in osteoblast differentiation by targeting TET2. Gene. 2020;726:144193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Yang KQ et al. Aortic Aneurysm in Takayasu Arteritis. The Am J Med Sci. 2017;354:539–547. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Harvey A, Montezano AC, Lopes RA, Rios F, Touyz RM. Vascular Fibrosis in Aging and Hypertension: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. The Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:659–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Deguchi JO et al. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: visualizing matrix metalloproteinase action in macrophages in vivo. Circulation. 2006;114:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Miyata T, Sato O, Koyama H, Shigematsu H, Tada Y. Long-term survival after surgical treatment of patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Circulation. 2003;108:1474–1480. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Park HS et al. Long term results of endovascular treatment in renal arterial stenosis from Takayasu arteritis: angioplasty versus stent placement. Europ J Radiol. 2013;82:1913–1918. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Sharma S, Gupta A. Visceral Artery Interventions in Takayasu’s Arteritis. Sem Interven Radiol. 2009;26:233–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Jeong HS, Jung JH, Song GG, Choi SJ, Hong SJ. Endovascular balloon angioplasty versus stenting in patients with Takayasu arteritis: A meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96:e7558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Peng M et al. Selective stent placement versus balloon angioplasty for renovascular hypertension caused by Takayasu arteritis: Two-year results. Int J Cardiol. 2016;205:117–123. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Misra DP et al. Outcome Measures and Biomarkers for Disease Assessment in Takayasu Arteritis. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2022;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Stojanovic M et al. Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Score as a Biomarker for Vascular Damage Assessment in Patients with Takayasu Arteritis-A Pilot Study. J Cardio Dev Dis. 2021;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Kong X et al. Treatment of Takayasu arteritis with the IL-6R antibody tocilizumab vs. cyclophosphamide. Int J Cardiol. 2018;266:222–228. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Matsuyama A et al. Matrix metalloproteinases as novel disease markers in Takayasu arteritis. Circulation. 2003;108:1469–1473. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Ishihara T et al. Diagnosis and assessment of Takayasu arteritis by multiple biomarkers. Circulation J: Official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2013;77:477–483. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.