Abstract

Purpose:

Most common treatments for stuttering offer advice that parents modify temporal features of conversational interaction to assist children who stutter (CWS). Advice includes but is not limited to slowing of adult speech, increasing turn-taking/response-time latencies (RTLs), and reducing interruptions. We looked specifically at RTL and parental speech rate in a longitudinal data set that included baseline behaviors.

Method:

We used data from baseline recordings (CWNS = 13 CWS-persistent, 28 CWS-recovered, 21 children who did not stutter) of the Illinois International Stuttering Research Project at FluencyBank, using CLAN software with audio linkage to Praat.

Results:

Group differences in speech rate and RTL at baseline were nonsignificant; parents of CWS-persistent spoke most slowly pre-advisement. No relationships between speech rate or RTL and child fluency were detected.

Conclusions:

This is a retrospective, observational study, and caution must be used in interpreting our findings. However, current results do not add evidentiary support for common advice to adjust temporal parameters of their interactions made to parents of CWS, in terms of therapeutic outcome or concurrent fluency. We are analyzing subsequent samples, after advisement, to determine potential benefits of such guidance not evident in this analysis. Suggestions for future research and implications for clinical focus and practice are offered.

In setting up the study we discuss here, we think it worthwhile to contemplate where our treatment practices come from and the evidence behind them. Treatment of any communication disorder in children should involve parent counseling but is considered particularly crucial in the treatment of young children who stutter (CWS). This may be because many early popular theories of the underlying pathology in stuttering suggested a role for parenting style, early parent–child interactions, or parental perceptions in its onset or persistence. Bloodstein (1993) notes that the popularity of psychoanalytic accounts of stuttering, ranging from Coriat (1943) to Fenichel (1945), fed hypotheses by the “fathers” of modern speech-language pathology (e.g., Johnson, Van Riper) that it could be managed by changing the child's environment. This belief itself was an optimistic change from prior hypotheses that stuttering was physiologically based and thus somewhat irremediable but pivoted attention from the child to their parents.

Various iterations of psychoanalytic theory were supplanted by semantic theory, most famously formulated by Johnson et al. (1942) in his “diagnosogenic” theory (based in part on Bluemel's [1935] study), which hypothesized that atypical responses to a child's normal developmental difficulties in formulating fluent speech might somehow shape the development of atypical profiles of speech fluency. Johnson was not alone in his thinking: As noted by Bloodstein (1993), when Van Riper issued his first textbook in 1939, he suggested that “the way to treat a young stutterer in the primary stage is to let him alone and treat his parents and teachers” (Bloodstein, 1993, p. 151). Bloodstein himself noted that “it is a plausible assumption that how a stuttering child is managed at home may have a great deal to do with whether stuttering is a transient episode or persists into adulthood as a chronic problem” (p. 151).

Studies repeatedly show that speech-language pathologists prefer to treat stuttering in young children “indirectly,” a long-standing legacy of such theories, and that they believe parent counseling to be the most important component in treating early stuttering (Cooper & Cooper, 1996; Gregg, 2015). An indirect approach to treating stuttering in very young children close to onset has been emphasized over many decades, including advice by Bloodstein (1958) and Luper and Mulder (1965). Only recently have direct treatments, such as the Lidcombe Program, achieved similar levels of popularity (McGill et al., 2019).1

We want to make clear that few therapists or researchers currently believe that parents' beliefs or behaviors cause the onset of stuttering. Rather, the diagnosogenic theory has been replaced by a series of related theories about stuttering that can broadly be subsumed under “Demands and Capacities” rubrics: that the environment does not create stuttering but that demands on limited child capacity (specified broadly in a range of linguistic, motor, temperamental, and cognitive skill sets) can limit or hinder the child's ability to produce fluent speech in certain settings. These models include the original Demands and Capacities Model (DCM; Starkweather et al., 1990), Palin Parent–Child Interaction (Kelman & Nicholas, 2020), and RESTART-DCM (Franken & Laroes, 2021), among others. While clearly distinct in philosophy, this general orientation has led to recommendations that sometimes can inadvertently place blame on parents by suggesting their speech behaviors may be capable of affecting fluency outcomes. It is important to note that most now advise the parent to acknowledge the child's difficulty in producing speech easily and fluently and discuss the possibility that the child's stuttering can impact the parent's speech and interaction profiles (see Kelman & Nicholas, 2020, as one example). What has remained relatively constant in work with the families of young children at the onset of stuttering is a continued assumption, even when tempered with discussion that the current evidence base is weak (Kelman & Nicholas, 2020), that changes in parental behaviors might assist the child in speaking more fluently, or achieving recovery, as we discuss further below. In this view, stuttering may be seen as parallel to other childhood chronic diseases, such as diabetes or asthma (Bernstein Ratner & Guitar, 2006), in which parents play little role in disease onset but an important role in managing symptoms. However, unlike those disorders, there is a thread running through at least some parent counseling that parental behaviors cannot just manage symptoms but may “prevent” stuttering from becoming persistent (Bloodstein, 1993).

We make these observations about theories of stuttering onset and persistence because we believe it can be useful to take a step back and ask where counseling components come from, historically. We next delineate the most common advisement to parents, followed by the current evidence base for believing such advice to be helpful, either in the short- or long-term management of childhood-onset stuttering.

What Are the Traditional Components of Parental Counseling in Early Stuttering?

Parents are frequently offered advice to alter their own speech behaviors in an effort to benefit the child's fluency, as seen in numerous treatment approaches. Typical counseling to parents spans temporal changes (reduced parental speech rate, lengthened turn-taking latencies), as well as other behaviors (see Bloodstein, 1993; Bloodstein et al., 2021; and Van Riper, 1973, for extensive discussions). Both professional and self-help organizations (e.g., the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA] and The Stuttering Foundation) specifically present similar advice. In addition, nearly all textbooks on stuttering over the past 50 years contain a chapter providing advice for parents; see early advice from Van Riper (1992), Starkweather et al. (1990), and Guitar and McCauley (2011), among others. Although numerous features of adult–child interaction are often targeted, this study and our review specifically examine temporal parameters, such as pacing of turns between parents and the child, and parental speech rate. Other reports have addressed whether or not parents should change questioning behaviors (Garbarino & Bernstein Ratner, 2022) or the syntactic complexity of language models (Burns & Bernstein Ratner, 2022).

Advisement Regarding Changes to the Timing and Pacing of Speech Between CWS and Their Parents

Charles Van Riper emphasized the importance of parental speech models in assisting young CWS to achieve or maintain fluency. His advice was quite specific, and one can easily follow his reasoning: Van Riper (1973) knew that children were more likely to be disfluent when trying to speak quickly. In his view, the best way to get young children to slow their speech rate was to model what one expected from them: He specifically targeted “improper speech models” (p. 380), concluding with an evocative neologism that “we need to bombard the child's ears with simple phrases and shorter utterances, all unhurried and fluently spoken … let us provide simple models for him to imitate if we desire fluency rather than gluency” (emphasis ours, p. 405). Bloodstein (1993) made similar recommendations, suggesting that

parents may unwittingly make demands on children to speak faster than they are able simply through the rapidity of their own rate of speech… . It is part of the unproven lore (emphasis ours) that one of the most effective ways of causing incipient stuttering to vanish is to train the parents to talk to the child at a slow rate of speech… . Most children who are talked to in a slow, deliberate way unconsciously fall in with that manner of speaking. (p. 152)

Current counseling comes from more recent sources but appears to follow the same reasoning or suggest that slowing conversational pacing provides a more generally relaxed context for parent–child interaction. For example, in the DCM (Starkweather et al., 1990), parents are advised to change their own speech behaviors when interacting with their CWS. The Palin Parent–Child Interaction Model advises (Kelman & Nicholas, 2020; Millard et al., 2008) “giving the child time” as well as modeling “pausing and rate of speech.” The family-centered intervention program published by Yaruss et al. (2006) also contains a parent-counseling component that guides families to reduce the pace of conversations, by both using “easy, relaxed” speech and lengthening pauses between speaking turns.

The RESTART-DCM method (Franken & Laroes, 2021) suggests that one method of reducing demands on the young CWS is “implementing long response time latency (approximately 1–2 seconds), [with] definitely no overlapping in speech turn-taking” (p. 17). Similar advice is also readily available on the Internet. The ASHAWire (Whelan, 2019) provides “Five Tips to Share with Parents of Preschoolers Who Stutter,” which include asking parents to “increase the length of pauses between speaking turns” because “children might feel pressure to get their words out before somebody else begins talking.” The suggestion to adjust conversational timing is also first on ASHA's list of suggestions to parents (Whelan, 2019) and fourth in The Stuttering Foundation's (n.d.) article “Seven Tips for Talking with Your Child.”

Despite the pervasiveness of such advice, a relatively small body of research exists on the effectiveness of these indirect therapy components in the short term. Additionally, no empirical evidence exists regarding whether temporal modifications affect longitudinal recovery and persistence outcomes in stuttering.

Research Efforts to Examine Temporal Features of Parent–Child Speech in Early Stuttering

Turn-Taking Latencies and Interruptions: Observational Studies

Previous research does provide some support for portions of advice. Egolf et al. (1972) and Kasprisin-Burrelli et al. (1972) may have been the first researchers to evaluate impacts of altered turn-taking on the fluency of CWS, albeit children well past preschool age (ages ranged from 6 to 13 years). Egolf et al. implemented a therapy that aimed to “invert” individual profiles of interaction that they observed during assessments in order to increase the child's fluency. Only one of a long list of features targeted for investigation was interrupting behaviors. Parental interruptions and response-time latency (RTL) contrast with one another: An interruption essentially results in negative RTL or talking over the child. If seen frequently in clinical observation, therapy was constructed to increase turn-taking latency. Therapy was judged to be successful in many of the cases they tracked, although interrupting was the only pacing advice included with primarily “message-level” categorization of parents' behaviors, such as negative evaluation or correction of the child's speech.

The first large-scale quantitative analysis of parent–child conversational pacing and interrupting behavior was probably conducted by Meyers and Freeman (1985a, 1985b). Meyers and Freeman (1985a) found that mothers of CWS spoke more quickly than mothers of nonstuttering children, when speaking with either CWS or children who do not stutter (CWNS). Ryan (2000), however, found exactly the opposite pattern: The mothers of 13 nonstuttering 4-year-old children spoke more quickly than the mothers of 13 CWS. Meyers and Freeman (1985b) studied 12 CWS/CWNS and their mothers. They found that mothers in both groups interrupted their child's disfluent speech more than their child's fluent speech. The study also found that both CWS and CWNS were more disfluent when in the act of interrupting their mother's speech. This study supports the idea that disfluencies and interruptions are related in some way. Interruption, by its very nature, reduces RTL and can be considered to be an indicator of a competitive speaking situation, increasing the pressure on the speaker and, thus, disfluency.

Ryan (2000) examined simultalk (the duration of overlapping segments of 13 mothers' and children's speech during free-play); stuttering severity scores were strongly correlated with average duration of simultalk events. Similarly, Kelly and Conture (1992) analyzed RTL in parent–CWS interactions with 13 pairs of male CWS/CWNS. A positive correlation was found between scores on the Stuttering Severity Instrument and the durations of the overlapping portions of their mother's interruptions. The authors speculated that increasing RTL may decrease the conversational pressure on the child and, as a result, decrease disfluency rate. However, the study primarily focused on interrupting behaviors, rather than RTL per se.

Studies That Manipulated Speech Rate and/or Turn-Taking

The studies we have discussed thus far were observational. Some studies have gone further and constructed conversational conditions that manipulate timing of adult–child turns or evaluated the outcome of instructions to parents that change the pacing of conversations. Some of these studies have suggested that slower maternal speech rate may reduce the frequency of stuttered events (Guitar & Marchinkoski, 2001; Guitar et al., 1992; Stephenson-Opsal & Bernstein Ratner, 1988; Zebrowski & Conture, 1989; Zebrowski & Schum, 1993). For example, in a staggered baseline intervention study with only two CWS, Stephenson-Opsal and Bernstein Ratner (1988) trained mothers to slow their base condition speaking rate. In subsequent sessions, when mothers spoke more slowly, their children's stuttering decreased.

However, relevant to Van Riper's and Bloodstein's belief that parental models encourage imitation by children, in this study, the children's speech rate did not entrain to that of their parents. Similarly, Guitar et al. (1992) reported that the single 5-year-old CWS they tracked became more fluent as the child's mother slowed her speech rate, although the child did not decrease their rate. Guitar et al. also divided the child's fluency behaviors into two categories: primary and secondary. Primary stuttering events were those judged to be effortless repetitions; secondary events were those accompanied by tension or accessory physical behaviors. The child's primary stuttering was highly correlated with maternal (but not paternal) speech rate, yet neither correlated well with her frequency of secondary stuttering.

Newman and Smit (1989) studied four 4-year-old children. In their study, the experimenter utilized a 1-s or 3-s RTL when responding to the child. The study found that children demonstrated longer RTLs when the experimenter employed the 3-s condition. The study concluded that children as young as 4 years old could modify their speech behavior, including RTL, to reflect that of their conversational partners. When the shorter, 1-s RTL condition was employed, three of the four children demonstrated increased “stutter-type” disfluencies.

Yaruss (1997) experimentally analyzed the concept of conversational pressure in 45 preschool-age CWS. In his “play with pressure” situation, the clinician was instructed to interrupt the child and increase time pressure. This situation elicited an increase in stuttering-like disfluency. In contrast, in a small study of three CWS by Livingston et al. (2000), where clinicians were instructed to interrupt the children's speech, few interruptions were associated with subsequent fluency of the children's utterances.

Winslow and Guitar (1994) also analyzed alterations in structured turn-taking when used with a single 5-year-old boy who stuttered. Structured turn-taking was employed during dinner conversations by designating speaking turns through passing an item around the table; the child's fluency improved during structured turn-taking.

Two studies have studied nonstuttering children's conversations with their mothers. Bernstein Ratner (1993) instructed two groups of 10 mothers of CWNS to alter aspects of their speech following a baseline play interaction. The first group was told to slow their speech rate, while the second group was asked to both slow speech rate and simplify utterance structure. The majority of children in each condition did not entrain to changes in their mothers' rates, which approximated roughly 25%. Maternal interspeaker latencies, which were not instructed, lengthened for both groups, albeit nonsignificantly. Similarly, RTLs increased nonsignificantly for the children as well, suggesting a minimal degree of temporal synchrony. Levels of typical disfluency were low in all conditions but increased slightly when mothers were asked to simultaneously change both pacing and linguistic complexity of their speech. Guitar and Marchinkoski (2001) taught six mothers of preschool-age children to slow their speech rate by roughly 50%. Fluency changes were not reported, but five of the six children reduced their speech rate in response to that of the mother's rate reduction.

Congruity Between Parental and Child Speech Rate in Stuttering

Finally, it has been suggested that one cannot examine either temporal parameters of parent–child interactions independently. Rather, it may be the relative difference between the children's and parent's pacing that is most important in impacting the child's fluency. Kelly (1994) introduced the notion of “dyadic rate” after noticing that when her study's fathers spoke much more quickly than their children, stuttering was more severe. Similarly, Zebrowski and Schum (1993) found that a disparity in speech rate between parent and child correlated with disfluency rate and emphasized the role of “temporal congruence or synchrony” in facilitating children's fluency.

Almost 20 years ago, Bernstein Ratner and Guitar (2006) discussed the impact of turn-taking and interrupting behaviors on fluency, citing many of the articles discussed above; few articles since then have examined impacts of parent counseling components on children's fluency, while a large number of studies that utilize parental advice to adjust pacing of conversations as part of a much larger “tool kit” have appeared. Bernstein Ratner and Guitar concluded that parent counseling yielded promising results; however, the number of children studied was, at the time, quite limited and continues to be so two decades later. Others have strongly criticized the evidence base for advice to parents of CWS (e.g., Nippold, 2018; Nippold & Rudzinski, 1995). Evidence-based recommendations to adjust parent–child interactions in stuttering require a more significant number of cases in which recommendations can be linked to even short-term changes in children's fluency profiles. Thus, we need greater evaluation of the degree to which our clinical advice to parents actually helps CWS.

To “help” the CWS, we will use original definitions, which were, for the most part, originally directed toward helping them achieve more fluent speech/stutter less frequently. We do consider this to be a very narrow definition of desired outcomes of parent counseling, and many of the currently implemented programs we have referenced go far beyond this narrow criterion in their therapeutic goal setting. However, insofar as many clinicians (and numerous parents) seek help to improve their child's fluency, we will ask whether or not specific components of parental advice accomplish this goal. We will return to goal setting for young CWS in discussion but do not wish to suggest that fluency is, or should be, the primary goal of informed intervention with preschool-age CWS.

What the Illinois International Stuttering Research Project Can Contribute to Our Understanding of RTL and Fluency in CWS

The Illinois International Stuttering Research Project (IISRP), conducted by Ehud Yairi, Nicoline Ambrose, and colleagues (for full details, see Yairi & Ambrose, 2005), was one of the most significant longitudinal studies of early stuttering and produced valuable information regarding factors that appear to contribute to stuttering persistence and recovery. These data have been donated to the open-access FluencyBank project (fluency.talkbank.org; Bernstein Ratner & MacWhinney, 2018). The entire IISRP database contains 440 samples from 88 CWS.

The IISRP, by its design, provides an interesting and unique natural experiment in the relationships among parent and child speech rates and turn-taking profiles. This is because families were seen 5 times each, at 6-month intervals, following a baseline parent–child play interaction conducted before any advice was offered to the parents of the CWS. At the time that the study began, parents' access to counseling advice was more limited than it is today: There was no World Wide Web to use in searching for information. The study also tracked appropriately matched CWNS. The longitudinal manner in which these files were collected, together with the inclusion of parent–child interactions, both before and following counseling that parents make speech rate and turn-taking changes, has the unique potential to strengthen or diminish the indirect therapy advice given to parents of CWS. Thus, our aim was to analyze parent–child turn-taking in early stuttering using the large cohort collected by the IISRP. In doing so, we posed the following questions:

Are there differences between the temporal features of speaking turns between parents and children who do and do not stutter, and those who recover as opposed to those who do not when first observed in a research setting? Do parents of CWS differ from parents of CWNS in terms of speech rate and RTL patterns? For RTL, does average duration or predictability (range of observed RTLs) play a role in short-term or long-term fluency profiles? Finally, does either parental speech rate or RTL distinguish between cadres of children who later recover from stuttering or remain persistent?

Based on existing research, we hypothesized that RTL may differ between dyads. For example, mothers of children who persist might use shorter RTLs than parents of children who recover. We also hypothesized that, if RTL played a role in fluency, then predictability of RTL might reduce conversational pressure and thus increase child fluency. Finally, we hypothesize that parents of CWS who recovered (CWS-R) might use a slower speech rate than parents of CWS who remained persistent (CWS-P).

Method

Participants

As a first-phase project, we analyzed all mother–child play interactions collected during Sample 1 of the IISRP (see Yairi & Ambrose, 2005; now publicly available at FluencyBank [https://www.fluency.talkbank.org]). Sample 1 is defined as when the children were seen for the first time. As analysis of archival, de-identified behavior, this project was determined to be exempt from human subject protections by the university institutional review board.

Sample 1 of the IISRP data contains 88 files with matched audio files. Thirty-nine were CWS-R, while 14 of the files were interactions with CWS-P. Additionally, 27 of the files were from CWNS.

Out of these 80 files, 62 consisted of a mother–child play interaction and were determined fit for analysis that kept parent role (mother/father) controlled (28 CWS-R, 13 CWS-P, and 21 CWNS). Some demographics for this sample are known for groups rather than individuals. Yairi and Ambrose (2005) noted that most children in their study were White and that small numbers of children from other racial/ethnic groups prevented any formal analysis of this factor. Finally, most children in the larger sample were from middle-income, two-parent families “with only a few that could be considered very low or very high income” (p. 41).

Files were contributed to FluencyBank with limited demographic information. However, we do know age and sex specific to each file we analyzed. Because we will discuss eventual fluency outcomes, sex and treatment history can be considered germane. As noted for the entire sample reported in Yairi and Ambrose (2005), girls were in the minority of all three groups examined in this report, but chi-square analysis found no difference in distribution by sex (χ2 = 1.691, df = 2, p = .4293). Similarly, although recovered children were noted to be younger than persistent children for the entire data set, in the sample report, no significant age effects were detected among groups. CNSs and CWS-P were roughly 41.9 and 41.1 months old, respectively; CWS-R were, on average, 38 months old. Individual therapy history is unknown for the contributed samples. However, Yairi and Ambrose (2005, p. 177) note that all but two of the original total cohort of CWS-P received treatment “at some point,” while Yairi and Ambrose (1999) note that none of the recovered children received formal treatment.

While parents did not have uniform information about stuttering prior to baseline recordings, all parents of CWS were given fairly uniform instruction following intake observation. In Yairi and Ambrose's (2005) study, general counseling of CWS families is described; extensive scripts are available in Chapter 11 that include instructions to decrease pressure (provide a relaxed environment, p. 36) and slowing speech.

All files are in TalkBank CHAT format (MacWhinney, 2000), with audio linkage that enables immediate Praat analysis to measure timing of selected acoustic segments. Although only children's speech was transcribed initially, University of Maryland researchers augmented files with transcription of the children's conversational partners.

Data Selection

The total data set available for analysis consisted of 20,013 child utterances (average = 323, range: 136–196). Maternal utterances totaled 21,002 (average per sample = 339, range: 100–1,154). We computed latencies differently than speech rate, given the need to measure times between utterances rather than within individual speaker turns. Thus, for all Sample 1 files in which there was a mother–child play interaction, we examined 20 consecutive child utterances and 20 mother utterances. Due to the time-consuming nature of acoustic analysis, 20 turn-taking interactions were seen to provide an adequate picture of what interactions may look like throughout the entirety of the sample. The utterances that were measured for RTL were the first 20 eligible utterances in the file. For the utterance to be considered eligible for analysis, the child needed to perform a meaningful speech act. Fillers such as “uh” and “um,” one-word responses, and sound play (e.g., pretending to be a race car or animal) were not considered. Additionally, to account for differences in paternal and maternal communication, we opted only to examine mother–child interactions (Berko Gleason, 1975; see VanDam et al., 2022, for a review).

Acoustical Analysis

Utilizing CLAN software, we aligned the files to include the target mother and child utterances in a single “bullet” or paired transcript/sound segment. Then, we utilized the “send to sound analyzer” feature on CLAN to transfer the segment to Praat (van Lieshout, 2003). Using CLAN sonic mode, we identified the RTL between the end of the child's utterance and when the mothers began speaking. RTL was measured in seconds; any parent overlap/interruption was coded as negative RTL.

Fluency Analysis

We then ran FluCalc, a function available through CLAN, which provides a detailed disfluency profile, proportioned over words in the sample, including the weighted stutter like disfluency (SLD) score (Ambrose & Yairi, 1999). The formula for weighted SLD multiplies the sum of part-word and whole-word repetitions by the mean number of observed repetition units in the sample; it then adds this value to twice the sum of prolongations and blocks. We analyzed all eligible mother–child dyads in Sample 1 for fluency score for all utterances within that file (not just the 20 selected for RTL analysis). We also hypothesized that parents who used more predictable RTL would foster fewer disfluencies in their child's speech because the child might better predict how much time was available to formulate their response; allowing insufficient time for a child to plan an upcoming utterance is in fact explicitly mentioned in numerous discussions of parent counseling in early stuttering. Thus, we took the mean and standard deviation of RTL for each individual parent–child interaction. This enabled us to look at the correlation between parental speech “predictability” and their child's weighted SLD score.

Speech rate computation is done automatically in FluCalc once a transcript is appropriately aligned with the speaker audio. We utilized the Batchalign utility (Liu et al., 2023) to abstract a generalized speech rate (words per minute) derived by tallying the length of an utterance in words or syllables, divided by the duration of the extracted audio signal.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was performed on each of the cohorts (CWS-R, CWS-P, and CWNS) to determine how the RTL of parents differed among the groups. This was done utilizing a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) between groups for RTLs. A repeated-measures ANOVA was used because our measurements of turn-taking were based on repeated observations (n = 20) of individual participants at a point in time. For RTL consistency, a Group × RTL ANOVA was run using the standard deviation of measured RTLs as a proxy for variability among turn latencies within a single mother's speech sample. Speech rate was assessed using a between-groups ANOVA. In addition, as noted above, relationships among maternal RTL and RTL variability were computed using regression analysis.

Results

RTL

Our baseline Sample 1 analysis consisted of 28 files from CWS-R and 13 files from interactions with CWS-P. In addition, 21 files from CWNS were analyzed. From these 62 files, 1,500 total data points (RTL latency values) were collected. Utilizing a repeated-measures ANOVA, we analyzed these 1,500 data points.

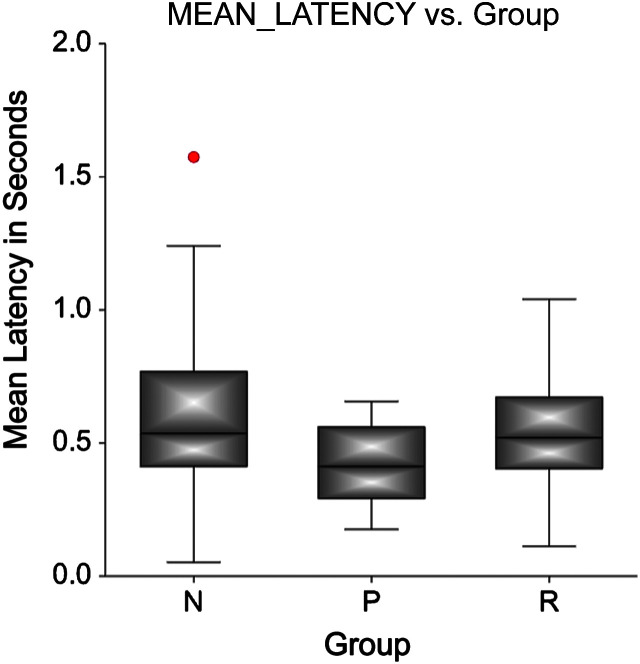

Findings show a slight but nonsignificantly higher parental RTL for children who recovered, as compared to those who became persistent. In the 20 turn-taking interactions analyzed for each mother–child dyad, it was found that parents of CWS-R used mean RTLs of 0.55 s, whereas parents of CWS-P used mean RTL times of 0.43 s. Additionally, parents of CWNS used mean RTL times of 0.62 s (see Figure 1). These differences were nonsignificant, F(2, 59) = 2.35, p = .10, ns. In contrast, differences in RTL across individual parent–child interactions (within-group variability) were highly significant, F(2, 59) = 2.58, p = .00005. This suggests marked differences across parent–child dyads in conversational tempo, regardless of group membership.

Figure 1.

Mean parental response-time latency in seconds for each dyad. N = nonstuttering; P = persistent; R = recovered.

For CWS–mother dyads only, a linear regression was used to determine whether the child's weighted SLD score was correlated with average mother–child RTL in the completed files. The relationship between mean RTL and weighted SLD was r = .019, p = .9058, ns (see Figure 2). This finding suggests that length of parents' time between speaking turns does not relate to children's fluency profiles. We also examined the predictability of turn-taking by plotting the standard deviation of the mothers' RTLs against the fluency profiles of the CWS (see Figure 3). Once again, this relationship was not significant, r = .1017, p = .527.

Figure 2.

Linear regression plot of mean latency times (in seconds) and stutter like disfluency (SLD) of individual children who stutter.

Figure 3.

Plot of standard deviation (SD) for mother's speech and fluency profile for children who stuffer (CWS) as measured using stutter like disfluency (SLD) score.

Speech Rate

We first computed average speech rate for both the children and their mothers (in words per minute; see Figure 4). Data violated assumptions of normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, and therefore, we utilized a Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks. For both maternal and child average speech rate, mothers and children in the recovered CWS group spoke more quickly than participants in the other two groups (for mothers: χ2 = 29.567, p < .0001; for children: χ2 = 13.205, p = .0014). A Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) multiple comparisons test showed that mothers of recovered CWS spoke significantly more quickly than the mothers in the other two groups. The same was found for child speech rate: CWS-R spoke more quickly than either typically fluent children or CWS-P.

Figure 4.

Maternal (MOT) and child (CHI) words per minute (WORD_MIN) for each group. N = nonstuttering; P = persistent; R = recovered.

Because all advice is predicated upon reducing differences in speech rate between parents and children, we then computed an average difference score for each individual child–mother dyad. These results are shown in Figure 5. Speech rate differences were highest for the dyads in which a CWS went on to recover and lowest in interactions between nonstuttering children and their mothers. These profiles were significantly different, χ2 = 15.286, p = .0005. The Fisher's LSD multiple comparisons test showed dyads where the CWS recovered had significantly greater disparities between child and maternal speech rate than dyads involving typically fluent children and their mothers, but not significantly greater than those seen between CWS-P and their mothers.

Figure 5.

Difference (DIF) in child (CHI) and mother (MOT) speech rate for each group. N = nonstuttering; P = persistent; R = recovered.

Discussion

We wish to begin this section with an important premise: We have nothing but the highest level of respect for the many thoughtfully developed and administered programs for helping young CWS and their families. Rather, our goal here is to use an important and unique set of data to ask whether or not it can provide support for two major components of most therapies that seek to manage children's fluency by adjusting the temporal parameters of parent–child interactions. Parents are frequently advised to change the way that they interact verbally with their young CWS, and a recent survey (Panico et al., 2021) reports that SLPs consider “educating parents to reduce communication demands” to be one of the most common situations they encounter in work with preschoolers who stutter. The list of strategies for reducing demand includes, among other approaches, lengthening RTLs and slowing parental speech rate. However, despite common advice to parents, a limited literature links parental rate or RTL to fluency in CWS, both during individual interactions, as well as to long-term outcomes, something that some of the programs themselves acknowledge (see discussion in Kelman & Nicholas, 2020, p. 18, for example), which prefaces some of their recommendations. Analysis of the unique longitudinal IISRP data set has the potential to either strengthen or diminish the evidence base for such this component of parent counseling.

In this sample, all parents and children provided baseline conversational play data before investigators instructed all parents of CWS to use a list of strategies that included slowed parental rate and taking longer time between conversational turns. This set of instructions was scripted and uniform and was provided only after baseline recordings were completed. Because this study was initially begun before common consumer use of the Internet, we can be somewhat confident that parents did not have access to these or similar strategies before entering the study. We cannot be certain of this, but even if pre-instructed, the results from this data set do not provide strong evidence that rate and turn-taking instructions reduce disfluencies in CWS, either in the short or long term.

Prior studies have analyzed the effect of RTL on fluency in highly structured environments, could not follow up the children they studied, and used very few participants (e.g., Meyers & Freeman, 1985a; Newman & Smit, 1989; Winslow & Guitar, 1994). While our study used free-play naturalistic samples to evaluate RTL and adult speech rate profiles and their impacts on fluency of CWS, we had the unique advantage of knowing what happened to the children over the course of the longitudinal study, unlike all prior work in this topic area. We asked whether or not RTL or parental speech rate related to fluency at stuttering onset before parent counseling and whether or not we could detect patterns of behavior that distinguished between groups of children who recovered from stuttering and those who did not.

This is the first stage of our analyses; our ongoing work examines temporal profiles seen after parents were advised to adjust the timing parameters of their interactions. Given the current technology, we had to limit RTL measurements to a standard subset of interactions that approximated the first 10% of the average sample, given the total number of turns available for analysis. We will be examining whether or not parents changed their behaviors when seen in subsequent visits and, if so, whether or not such changes related in systematic ways with the child's follow-up fluency profiles, or eventual status as recovered or persistent.

Currently, our results do not appear to provide strong support that parental rate of speech and RTL result in changes in SLD when SLD is the dependent variable. These results do not provide further evidentiary support for common advice given to parents of CWS; differences among groups in RTL were nonsignificant, as were correlations within sessions for variability in RTL and child fluency. Results from Sample 1, prior to parent counseling, suggest that the most variability between RTL existed across individual parent–child interactions. That is, individual parent–child pairs had their own personal “timing” rhythm that distinguished them from other dyads, while differences among groups were fairly insubstantial.

We found no statistically significant evidence that, at stuttering onset, parent turn-taking latencies differ between groups of children who will recover and those who will not. In addition, our research does not appear to provide strong support for the notion that, at stuttering onset, before advisement, parental RTL or predictability of RTL or general speech rate plays a role in the short-term facilitation of fluency. There was no correlation between RTL or consistency of RTL and children's stuttering rate during the same sessions. Our goal in this article, therefore, was only to examine two discrete components found in many multifaceted therapies for stuttering in young children (Sjøstrand et al., 2024).

Limitations

As with any retrospective study, this one did have substantive limitations that must temper any strong conclusions based on our findings. First, we examined only one cohort of children and only the speech behaviors of that cohort and their mothers; we cannot weigh multiple additional factors reported to impact recovery in this very same set of children (such as family history and initial language skills; see Yairi & Ambrose, 2005). Given that this was a retrospective study, it is thus possible that the available corpus was underpowered to distinguish differences between groups. While we can say that statistically significant differences were not observed among the groups of parent–child dyads, we cannot reject the possibility that a larger, prospective study would detect clinically relevant differences, in either a naturalistic or guided intervention context.

A number of confounds may complicate the interpretation of our current results. It is possible that stuttering severity or general rate of disfluency provoked changes in parental behaviors, rather than the inverse. By definition, CWNS differed in rate of disfluency from those who did. A post hoc analysis of the baseline disfluency rates of children who did and did not recover showed that children who recovered had minimally higher rates of disfluency; this is consistent with general reports from the original IISRP that initial profiles of stuttering severity were not predictive of eventual recovery status (Yairi & Ambrose, 2005). However, some factors did distinguish the two groups, such as sex; girls were more numerous in the recovered group. The recovered group was slightly younger, at roughly 38 months old, than the typically fluent or persistent group, at roughly 42 months old each, although this difference was not statistically significant; the original study did find that earlier stuttering onset (which might have coincided with earlier first experimental recordings) was more predictive of recovery. Other factors that might confound our analysis are simply unknown at the individual case level for the available data, although group demographics are available. These include speech and language abilities and therapy history, to name just two possible major confounds.

In addition, we did not have the ability to collect these speech samples ourselves. This limited our control over how the samples were collected and whether they were representative of typical parent–child interactions within that specific family. We were also unable to gather information about the home speech environment of the child. These samples were taken in a foreign environment with new people present, which may have resulted in higher anxiety or unnatural behavior among the children and parents. No outside information is available about the children other than what presents itself in the archived speech samples, which were used as a proxy of the parent–child interactions outside of the clinic.

While we seriously doubt whether parents had been given much advice about changing their profiles of interaction with their children before seeing the research team at the IISRP, we cannot of course know this definitively. However, we note that, if parents had been so instructed and were implementing the advice, it still did not result in an interpretable level of support for the advice—that is, whatever the speech rate before, it did not seem to relate to concurrent or outcome child stuttering profiles, and neither did patterns of RTL. The only possible impact of such advice, had it been given and followed prior to baseline taping, would have been to distinguish dyads of CWS and their parents from CWNS and their parents, and no clear pattern of behavior emerged in those comparisons.

A related concern is that we cannot evaluate the impacts of any interventions or counseling that occurred between the baseline recordings and the final sessions during which recovery or persistence was determined. Parental speech rate and turn-taking can only constitute one small part of the many facets of household and professional interaction that transpired during the course of the IISRP and were not tracked (in any surviving fashion, at least) for possible impacts on outcomes.

Our goal in this particular analysis was to assess baseline behaviors prior to training or advice. Thus, it cannot answer the question of whether instructed changes (and the ways in which they are taught, modeled, or given feedback) change parental styles of interaction or whether any such changes impact fluency outcomes in CWS. In our next phase of work, we do intend to track whether parents did appear to change the temporal features of their child-directed speech, given their own individual baseline profiles, and whether or not such changes appear to relate to eventual fluency outcomes.

This was a pilot study, and as noted, we did not analyze every single turn in the parent–child interactions for RTL, although we were able to compute speech rate and fluency over the entirety of the samples. The number of turns we could analyze (over 1,500) was limited due to the time-consuming manner in which these data must be analyzed (exporting utterances to waveform measurement utilities). We also analyzed only the first 20 mother–child interactions in each sample; this amounts to roughly 10% of available turns (some interactions were as long as 200 or more turns involving the participant mother and child) and may not give us a large-enough sample to see the impact of RTL entirely. Further work could verify our initial findings using all eligible turns; whether or not behavior in the experimental setting mirrors turn-taking behavior in the children's natural environment cannot be known. However, future work could utilize increasingly popular all-day recording technologies for this purpose.

We measured fluency across the entire sample, not only those utterances for which we had computed acoustical information. We also limited our attention to mothers; fathers are known to differ in their interactions with young children along a number of parameters (minimally including questioning behavior, vocabulary choice, and use of corrections), and we did not have statistical power to consider both mother–child and father–child interactions properly (see Berko Gleason, 1975; Bernstein Ratner, 1988; Schwab et al., 2018). Whether father–child interactions differ among groups or impact fluency in CWS could not be addressed in this study.

We do have follow-up data at both 6 months and 1 year for the CWS and parents (but not always the same parents recorded at Time 1). A next step is to examine whether or not parents changed behaviors and whether any degree of change in temporal features of interaction appears to have related to final diagnostic status. We are currently engaged in these analyses now.

The IISRP design was a fairly unique opportunity to conduct a retrospective analysis of advice to parents of CWS but cannot hope to match the robustness of a prospective project with the same set of goals. We are not sure of a world in which we could find parents who are relatively untouched by societal advice these days, unlike our first forays into quite limited exploration of how parental speech rate might impact children's stuttering (Stephenson-Opsal & Bernstein Ratner, 1988), a project that found only two “naive” parents, even before the advent of Internet searches (and did not follow the families for very long).

We also selected RTL and parental speech rates as the sole measures to evaluate in this study. It is possible that temporal adjustment, when combined with other types of advice, such as modification of the semantic content or linguistic features of parental speech, is part of a holistic, multipronged, and effective treatment to reduce stuttering. In ongoing work, however, using the same data set, parental language complexity does not appear to differentiate between the CWS who recover and do not (Burns & Bernstein Ratner, 2022), nor does parental questioning (using a different cohort of CWS/CWNS and their parents; Garbarino & Bernstein Ratner, 2022). Put succinctly, we have yet to determine a specific component within the multipronged set of advice often offered to parents that, considered on its own, appears to relate to short-term or long-term fluency profiles in a reasonably large group of CWS. Thus, while the flexible application of numerous pieces of advice may be helpful to children's fluency or eventual recovery from stuttering, speech rate and prolonged RTL by themselves may not influence fluency in predictable ways when considered in isolation.

We also note that some parent counseling results in changes not explicitly targeted. In Bernstein Ratner's (1993) study, instructions to speak more slowly led to simplification of input language in one group of mothers. More recently, Lidcombe researchers noted that RTLs of clinicians lengthened during their administration of the therapy in lieu of parents (Amato Maguire et al., 2023), although changes in the pacing of adult–child interaction are not targeted by that treatment approach.

Our current findings do not support a conclusion that indirect therapy approaches do not work; they simply do not support that they do. It is crucial that this work be replicated in order to draw stronger conclusions as to whether indirect therapy techniques are effective in the management of stuttering.

We also do not mean to suggest that, even if current advice to parents does not impact stuttering frequency or diagnostic outcome, parents and therapists should interpret such research by feeling that their ability to influence positive outcomes for CWS has been diminished. For many childhood disorders, parental engagement and involvement, under the guidance of specialists, is critical for management of the child's condition and successful outcome, particularly when the outcome is not (or cannot be) defined as “curing” the disorder or eliminating all of its symptoms. The literature is quite voluminous and compelling in this regard, from asthma to diabetes to rheumatoid arthritis and beyond. Self-management/self-efficacy and positive outcomes derive from early parental engagement in diverse chronic health conditions and impact both parents and the child (e.g., Kieckhefer et al., 2014). Joint parent–child problem solving of both behavioral and cognitive/emotional challenges has documented advantages in an array of chronic childhood conditions (e.g., Friedrich et al., 2016).

Concluding Thoughts

In summary, two pieces of common advice given to parents of CWS (speak more slowly and increase RTL, or “count to 2 before responding to your child” as advised by https://myhealth.alberta.ca/speech-language-hearing/stuttering/learn-more/when-a-child-stutters-what-you-can-do-to-help) were not supported by this limited, retrospective analysis of a major stuttering project. If confirmed by further research, this could have wide-reaching ramifications for clinical practice with young children close to stuttering onset.

Because the second author conducted some of the earlier research used to support these recommendations, this report may seem somewhat at odds with a prior published orientation to indirect therapy and its components. In writing this article, both authors were somewhat dismayed by the relative lack of more recent basic or applied research conducted since early efforts to estimate the effectiveness of selected components of indirect therapy advice. We continue to emphasize the need for this type of research.

In asking parents to modify speech behaviors, clinicians may also unknowingly (or knowingly) suggest that the primary or even a primary overarching goal of therapy is to reduce disfluency in CWS. This has the strong potential to send the message that continued stuttering represents a failure of therapeutic intervention or, more pointedly, a failure of the parent to successfully implement therapeutic advice. Van Riper, even as he himself recommended that parents speak more slowly and slow the pacing of conversational interactions together with more direct interaction with the beginning CWS, somewhat sarcastically noted that, if indirect therapy was the only option that clinicians utilized, “they content themselves with giving some superficial advice to the parent and thereby absolve themselves of unwanted responsibility. If the child grows worse, the parents have all the blame, and if he gets better, the therapist can claim the credit” (p. 399).

In recent years, new frameworks for stuttering therapy have emerged, although they are more obviously detailed in therapies for older children and adults, such as avoidance reduction therapy (Sisskin, 2018), but are moving down in the age range (Sisskin & Goldstein, 2022) and are components of many of the therapies we discuss in our background section: Rather than encouraging parents to work toward reducing or eradicating stuttering in the child's speech, it may be more useful to educate parents and children in acceptance of stuttering and ways to move past stuttering moments more easily and with fewer adverse secondary behaviors. Again, we emphasize that most current parent counseling contains this messaging; we seek only to question whether some of these counseling “packages” would be more effective if they contained fewer pieces of advice rather than more.

Pending replication of our findings, which is critical, we would suggest that continued use of parental advice that is not supported by research risks a number of potential adverse impacts, to both the family and child in treatment, as well as to the field at large. Indirect therapy that does not target the child's speech directly does target the parent: Fluency outcomes that bear no reasonable relationship to their implementation of our advice cannot but elevate the risk of increased parental guilt over aspects of their child's development that they actually cannot control in foreseeable ways. It risks sending a message that is difficult to “recall”: that if they follow our instructions, the child will stutter less, or not at all, and that is how we define success of our treatments. For the clinicians and researchers among us, there appears to be a default impression that such advice works, or certainly cannot hurt (a concept we ourselves previously endorsed but now doubt pending further research support). In taking for granted that we know certain things, we do not extend our lens to investigate other potential determinants, not only of child fluency but also of child and parent well-being. We believe that it is time to take a more careful look at the individual components of therapeutic advice to parents (or to the children themselves) to see if they work (and understand why it makes sense that they do, a long-standing problem we have tackled in trying to detangle the basis for, and outcomes of, operant treatments, such as Lidcombe; Bernstein Ratner, 2005).

Most research reports that investigate outcomes of early interventions for childhood stuttering take speech fluency as their primary measure. They also use adult judgment of outcomes as a proxy for actual speaker outcomes. In this sense, the work of Franken and Laroes (2021) is somewhat of a call to re-alignment, insofar as some of their child participants disagreed with parental and therapist assessments of “recovery.” In this regard, it seems probable that overt fluency is not the ultimate or sole indicator of optimum therapeutic outcome and that we need to consider affective and cognitive outcomes, and overall quality of life, over the long term, of any early intervention program for childhood-onset stuttering. This type of longitudinal research is difficult and expensive to conduct but may shed more light on preferred practices in early childhood stuttering than information we currently possess.

One reading of our research might put greater emphasis on alternative therapy components, such as self-acceptance and ability to move past stuttering moments more comfortably, as opposed to ones primarily targeted at reducing disfluency. As we noted earlier, many programs already do this—but, like any techniques or approaches, these take time to instruct and counsel and could profit from time otherwise used to advise parents in techniques with poor evidence base that also send contradictory messages: that our advice will reduce stuttering frequency or change eventual outcomes. If our work is confirmed by further efforts, and suggests eliminating advice that may have long outlived both its theoretical underpinnings and efforts to validate its effectiveness, we would be able to create more time, space, and discussion to ask what more we can do to improve quality of life for young CWS and their families.

Data Availability Statement

All primary data for this project are available at FluencyBank (http://fluency.talkbank.org).

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by the National Stuttering Association CASE Grant to Nan Bernstein Ratner and by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R01DC307764 to Brian MacWhinney and Nan Bernstein Ratner. We wish to thank the original participants and researchers in the Illinois International Stuttering Research Project as well as Yairi and Ambrose, who donated the study data to FluencyBank so that others could continue their important work. Finally, we wish to thank University of Maryland students in the Language Fluency Lab for their assistance with this project.

Funding Statement

Funding for this project was provided by the National Stuttering Association CASE Grant to Nan Bernstein Ratner and by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R01DC307764 to Brian MacWhinney and Nan Bernstein Ratner.

Footnote

We note, in passing, that outcome data from the Lidcombe Program itself tend to further discount diagnosogenic accounts of stuttering, since parents are advised to directly provide feedback to children's fluency as a major component of the treatment, something that Johnson would have found inadvisable, to say the least.

References

- Amato Maguire, M., Onslow, M., Lowe, R., O'Brian, S., & Menzies, R. (2023). Searching for Lidcombe Program mechanisms of action: Inter-turn speaker latency. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 37(12), 1091–1103. 10.1080/02699206.2022.2140075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, N. G., & Yairi, E. (1999). Normative disfluency data for early childhood stuttering. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42(4), 895–909. 10.1044/jslhr.4204.895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berko Gleason, J. (1975). Fathers' speech and other strangers: Men's speech to young children. In Dato D. P. (Ed.), Developmental psycholinguistics: Theory and applications (pp. 289–297). Georgetown University School of Languages and Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein Ratner, N. (1988). Patterns of parental vocabulary selection in speech to very young children. Journal of Child Language, 15(3), 481–492. 10.1017/S0305000900012514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein Ratner, N. (1993). Parents, children, and stuttering. Seminars in Speech and Language, 14(3), 238–250. 10.1055/s-2008-1064174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein Ratner, N. (2005). Evidence-based practice in stuttering: Some questions to consider. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 30(3), 163–188. 10.1016/j.jfludis.2005.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein Ratner, N., & Guitar, B. (2006). Treatment of very early stuttering and parent-administered therapy: The state of the art. In Bernstein Ratner N. & Tetnowski J. (Eds.), Current issues in stuttering research and practice (pp. 99–124). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein Ratner, N., & MacWhinney, B. (2018). Fluency Bank: A new resource for fluency research and practice. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 56, 69–80. 10.1016/j.jfludis.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloodstein, O. (1958). Stuttering: A symposium. Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Bloodstein, O. (1993). Stuttering: The search for a cause and a cure. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bloodstein, O., Bernstein Ratner, N., & Brundage, S. B. (2021). A handbook on stuttering (7th ed.). Plural. [Google Scholar]

- Bluemel, C. S. (1935). Stammering and allied disorders. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, M., & Bernstein Ratner, N. (2022). It's just that simple: Parental language complexity in early childhood stuttering. In Wagovich S. (Ed.), Joint World Congress on Stuttering and Cluttering Proceedings. https://web.archive.org/web/20231022192016/https://www.theifa.org/ifa-congresses-2/ifa-congress-proceedings/2022-jwc-proceedings.html

- Cooper, E. B., & Cooper, C. S. (1996). Clinician attitudes towards stuttering: Two decades of change. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 21(2), 119–135. 10.1016/0094-730X(96)00018-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coriat, I. H. (1943). The psychoanalytic conception of stammering. Nervous Child, 2, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Egolf, D. B., Shames, G. H., Johnson, P. R., & Kasprisin-Burrelli, A. (1972). The use of parent–child interaction patterns in therapy for young stutterers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 37(2), 222–232. 10.1044/jshd.3702.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenichel, O. (1945). The psychoanalytic theory of neurosis. W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Franken, M. C., & Laroes, E. (2021). RESTART-DCM method. Revised edition. Retrieved February 24, 2024, from https://restartdcm.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/RestartDCM-Method-2021_online.pdf [PDF]

- Friedrich, E., Jawad, A. F., & Miller, V. A. (2016). Correlates of problem resolution during parent–child discussions about chronic illness management. Children's Health Care, 45(3), 323–341. 10.1080/02739615.2015.1038681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, J., & Bernstein Ratner, N. (2022). What is the role of questioning in young children's fluency? American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 31(5), 2061–2077. 10.1044/2022_AJSLP-21-00209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg, B. A. (2015). Academic training in initial counseling of parents of preschoolers who stutter: A simulated caregiver model. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 193, 123–130. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guitar, B., & Marchinkoski, L. (2001). Influence of mothers' slower speech on their children's speech rate. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 44(4), 853–861. 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitar, B., & McCauley, R. J. (2011). Treatment of stuttering: Established and emerging interventions. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Guitar, B., Schaefer, H. K., Donahue-Kilburg, G., & Bond, L. (1992). Parent verbal interactions and speech rate: A case study in stuttering. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35(4), 742–754. 10.1044/jshr.3504.742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, W., Van Riper, C., Davis, D., Scarbrough, H., Hunsley, Y., Bakes, F., Travis, L., & Dwyer, S. (1942). A study of the onset and development of stuttering. Journal of Speech Disorders, 7(3), 251–257. 10.1044/jshd.0703.251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprisin-Burrelli, A., Egolf, D. B., & Shames, G. H. (1972). A comparison of parental verbal behavior with stuttering and nonstuttering children. Journal of Communication Disorders, 5(4), 335–346. 10.1016/0021-9924(72)90004-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, E. M. (1994). Speech rates and turn-taking behaviors of children who stutter and their fathers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 37(6), 1284–1294. 10.1044/jshr.3706.1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, E. M., & Conture, E. G. (1992). Speaking rates, response time latencies, and interrupting behaviors of young stutterers, nonstutterers, and their mothers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35(6), 1256–1267. 10.1044/jshr.3506.1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, E., & Nicholas, A. (2020). Palin parent–child interaction therapy for early childhood stammering. Routledge and CRC Press. 10.4324/9781351122351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kieckhefer, G. M., Trahms, C. M., Churchill, S. S., Kratz, L., Uding, N., & Villareale, N. (2014). A randomized clinical trial of the Building on Family Strengths Program: An education program for parents of children with chronic health conditions. Maternal & Child Health Journal, 18(3), 563–574. 10.1007/s10995-013-1273-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., MacWhinney, B., Fromm, D., & Lanzi, A. (2023). Automation of language sample analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 66(7), 2421–2433. 10.1044/2023_JSLHR-22-00642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, L. A., Flowers, Y. E., Hodor, B. A., & Ryan, B. P. (2000). The experimental analysis of interruption during conversation for three children who stutter. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 12(4), 235–266. 10.1023/A:1009465828258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luper, H. L., & Mulder, R. L. (1965). Stuttering: Therapy for children. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, B. (2000). The CHILDES project: Tools for analyzing talk (3rd ed.). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, M., Noureal, N., & Siegel, J. (2019). Telepractice treatment of stuttering: A systematic review. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health, 25(5), 359–368. 10.1089/tmj.2017.0319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, S. C., & Freeman, F. J. (1985a). Interruptions as a variable in stuttering and disfluency. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 28(3), 428–435. 10.1044/jshr.2803.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, S. C., & Freeman, F. J. (1985b). Mother and child speech rates as a variable in stuttering and disfluency. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 28(3), 436–444. 10.1044/jshr.2803.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard, S. K., Nicholas, A., & Cook, F. M. (2008). Is parent–child interaction therapy effective in reducing stuttering? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51(3), 636–650. 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/046) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, L. L., & Smit, A. B. (1989). Some effects of variations in response time latency on speech rate, interruptions, and fluency in children's speech. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 32(3), 635–644. 10.1044/jshr.3203.635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nippold, M. A. (2018). Stuttering in preschool children: Direct versus indirect treatment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(1), 4–12. 10.1044/2017_LSHSS-17-0066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nippold, M. A., & Rudzinski, M. (1995). Parents' speech and children's stuttering: A critique of the literature. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 38(5), 978–989. 10.1044/jshr.3805.978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panico, J., Daniels, D. E., Yarzebinski, C., & Hughes, C. D. (2021). Clinical experiences of school-based clinicians with stuttering: A mixed methods survey. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 6(2), 356–367. 10.1044/2020_persp-20-00193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, B. P. (2000). Speaking rate, conversational speech acts, interruption, and linguistic complexity of 20 pre-school stuttering and non-stuttering children and their mothers. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 14(1), 25–51. 10.1080/026992000298931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, J. F., Rowe, M. L., Cabrera, N., & Lew-Williams, C. (2018). Fathers' repetition of words is coupled with children's vocabularies. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 166, 437–450. 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisskin, V. (2018). Avoidance reduction therapy for stuttering (ARTs). In Amster B. & Klein E. (Eds.), More than fluency: The social, emotional, and cognitive dimensions of stuttering (pp. 157–186). Plural. [Google Scholar]

- Sisskin, V., & Goldstein, B. (2022). Avoidance reduction therapy for school-age children who stutter. Seminars in Speech and Language, 43(2), 147–160. 10.1055/s-0042-1742695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjøstrand, Å., Næss, K. A. B., Melle, A. H., Hoff, K., Hansen, E. H., & Guttormsen, L. S. (2024). Treatment for stuttering in preschool-age children: A qualitative document analysis of treatment programs. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 67(4), 1020–1041. 10.1044/2024_JSLHR-23-00463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkweather, C. W., Ridener Gottwald, S., & Halfond, M. M. (1990). Stuttering prevention: A clinical method. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson-Opsal, D., & Bernstein Ratner, N. (1988). Maternal speech rate modification and childhood stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 13(1), 49–56. 10.1016/0094-730X(88)90027-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stuttering Foundation. (n.d.). Seven tips for talking with your child. Retrieved February 24, 2024, from https://www.stutteringhelp.org/7-tips-talking-your-child

- van Lieshout, P. (2003). Praat short tutorial: A basic introduction. https://web.stanford.edu/dept/linguistics/corpora/material/PRAAT_workshop_manual_v421.pdf

- Van Riper, C. (1973). The treatment of stuttering. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Van Riper, C. (1992). The nature of stuttering (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- VanDam, M., Thompson, L., Wilson-Fowler, E., Campanella, S., Wolfenstein, K., & De Palma, P. (2022). Conversation initiation of mothers, fathers, and toddlers in their natural home environment. Computer Speech & Language, 73, Article 101338. 10.1016/j.csl.2021.101338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan, A. (2019, May 15). 5 tips to share with parents of preschoolers who stutter. The ASHA LeaderLive. https://leader.pubs.asha.org/do/10.1044/5-tips-to-share-with-parents-of-preschoolers-who-stutter/full/ [Google Scholar]

- Winslow, M., & Guitar, B. (1994). The effects of structured turn-taking on disfluencies: A case study. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 25(4), 251–257. 10.1044/0161-1461.2504.251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yairi, E., & Ambrose, N. G. (1999). Early childhood stuttering I: Persistency and recovery rates. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42(5), 1097–1112. 10.1044/jslhr.4205.1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yairi, E., & Ambrose, N. G. (2005). Early childhood stuttering. Pro-Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Yaruss, J. S. (1997). Clinical implications of situational variability in preschool children who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 22(3), 187–203. 10.1016/s0094-730x(97)00009-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yaruss, J. S., Coleman, C., & Hammer, D. (2006). Treating preschool children who stutter: Description and preliminary evaluation of a family-focused treatment approach. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37(2), 118–136. 10.1044/0161-1461(2006/014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowski, P. M., & Conture, E. G. (1989). Judgments of disfluency by mothers of stuttering and normally fluent children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 32(3), 625–634. 10.1044/jshr.3203.625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowski, P. M., & Schum, R. L. (1993). Counseling parents of children who stutter. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 2(2), 65–73. 10.1044/1058-0360.0202.65 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All primary data for this project are available at FluencyBank (http://fluency.talkbank.org).