Abstract

Background:

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) has shown satisfactory therapeutic efficacy in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and is regarded as an important conversion treatment. However, limited information is available regarding the optimal timing of HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy. This study aims to determine the optimal timing for HAIC-based conversion surgery in patients with HCC.

Methods:

Data from a retrospective cohort of patients who underwent HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy were reviewed. Oncological outcomes, surgical information, and risk factors were comparatively analyzed.

Results:

In total, 424 patients with HCC who underwent HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy were included and were divided into responder (n=312) and nonresponder (n=112) groups. The overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates of both the whole responder cohort and patients who achieved a response after 4–6 cycles of HAIC were significantly better than those of the nonresponder cohort. Higher OS and RFS were observed in responders than in nonresponders with advanced-stage HCC. Patients in the responder group had a shorter occlusion duration and less intraoperative blood loss than those in the nonresponder group. There were no significant differences in other surgical information or postoperative complications between the two groups. Tumor response, differentiation, postoperative alpha-fetoprotein level, postoperative protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II level, age, microvascular invasion, pre-HAIC neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and preoperative systemic inflammatory response index were independent risk factors for poor long-term survival.

Conclusions:

Conversion surgery should be considered when tumor response is achieved. Our findings may be useful in guiding surgeons and patients in decision-making regarding HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy.

Keywords: conversion, hepatectomy, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy, hepatocellular carcinoma, outcome, tumor response

Introduction

Highlights

The OS and RFS rates of both the whole responder cohort and patients who achieved a response after 4–6 cycles of HAIC were significantly better than those of the nonresponder cohort.

Higher OS and RFS were observed in responders than in nonresponders with advanced-stage HCC.

Patients in the responder group had a shorter occlusion duration and less intraoperative blood loss than those in the nonresponder group did.

Our findings may guide clinicians in developing personalized therapeutic strategies for patients undergoing HAIC-based liver resection.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common liver malignancy, is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates, especially in China1,2. Despite advances in therapeutic strategies, radical surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for patients with HCC. However, over 70% of patients with HCC present with tumors that are not amenable to radical surgery because of unfavorable tumor-related factors at initial diagnosis that limit the potential for improved prognosis3. Recent studies reported that conversion therapies reverse the surgical resectability of unresectable tumors, thereby lengthening patient survival4–6. Consequently, an increase in the conversion and resection rates of unresectable tumors has been advocated7.

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) shows satisfactory therapeutic efficacy in advanced-stage HCC, becoming a vital treatment for patients with unresectable liver cancer8–10. Patients with intermediate-stage or advanced-stage HCC have shown to benefit from cotherapy using tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and HAIC11. This strategy might produce a synergistic anticancer effect, thereby prolonging the survival of this subset of patients. HAIC-based conversion resection has been reported to improve outcomes in patients with HCC12,13. Patients with good tolerance and efficacy have undergone conversion surgery to achieve tumor-free survival13.

Effective conversion therapy induces significant tumor shrinkage or downstaging, leading to higher disease control rates (DCR)14. However, the optimal timing for conversion surgery remains unclear. One option is performing a hepatectomy when patients achieve stable disease (SD) and the future liver remnant (FLR) is evaluated to be of sufficient volume. Alternatively, conversion treatment and surgery could be considered only when complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) is achieved. Unfortunately, the optimal approach has not been established, and no prior studies have reported the timing of conversion to liver resection14,15. Furthermore, no previous studies have reported the timing of conversion to liver resection.

This study retrospectively analyzed patients with HCC who underwent HAIC-based conversion surgery at four medical institutions. Survival rates were compared between patients who achieved CR/PR and those who achieved SD/progressive disease (PD). Moreover, the relationships between tumor response, hepatic portal occlusion time, and intraoperative blood loss were evaluated.

Methods

Patients and study design

This retrospective cohort study included patients who underwent HAIC-based conversion surgery between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2022, at four institutions. Patients who were diagnosed with HCC and unsuitable for radical resection because of vascular invasion, multiple lesions, or insufficient FLR, but with well-compensated liver function (Child-Pugh grade A/B) and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ≤1 were candidates for HAIC.

Patients who received conversion surgery were included based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) their conversion therapy included HAIC, (2) their intrahepatic lesion was controlled following HAIC-based conversion treatment, (3) the tumor was completely removed (R0 resection), (3) well-preserved hepatic function (Child-Pugh grade A/B), and (5) ECOG ≤1. Patients with (1) a history of other concurrent malignant tumors, (2) organ insufficiency during treatment (e.g. pulmonary, cardiocirculatory, or renal insufficiency), or (3) incomplete information or follow-up data were excluded.

Patient clinicopathological information was collected before the initial HAIC therapy, between the last HAIC and conversion hepatectomy, and 1 month after resection. This study was conducted in accordance with strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional, and case–control studies in surgery (STROCSS) criteria16, (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/D307). Routine preoperative assessments were performed to evaluate liver, renal, and coagulation functions, as well as liver cancer-specific tumor markers, including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). Other assessments conducted before liver resection included abdominal imaging using MRI, computed tomography (CT), and ultrasonography; CT scan of the chest; cardiopulmonary function examinations; and ECOG score.

Treatments and evaluation: HAIC and surgery

HAIC was administered using a modified folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) regimen we previously reported8,17. Briefly, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, leucovorin 400 mg/m2, and fluorouracil 400 mg/m2 were administered on day 1, followed by a 46 h infusion of fluorouracil (2400 mg/m2). Each HAIC treatment cycle was 3 weeks long and patients were treated using the same protocol and dose regimen at each center. Tumor response was evaluated using the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST)18 at the end of two HAIC treatment cycles. Radiological assessment using MRI or CT was performed and no more than six cycles of HAIC treatment was recommended for any patient.

The surgical procedures were scheduled 4–8 weeks after the final HAIC treatment and were performed or supervised by two senior consultant surgeons specializing in liver surgery. Ultrasound was routinely performed during surgery to confirm the size, number, and location of the lesions and to identify the relationship between the tumor and major vasculobiliary structures. Hepatic transection instruments were chosen according to the surgeon’s preference, including a harmonic scalpel, Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator, or bipolar electrocoagulation. The extent of the liver resection was determined using preoperative imaging and intraoperative ultrasonography. Hepatic inflow occlusion was performed according to the intraoperative conditions. Hepatectomy was performed with the aim of achieving margin-negative resection (R0) and a drain was placed near the resection surface.

Outcomes and follow-up

Patients were followed up according to a standardized protocol, with regular visits scheduled every 2 months for the first 2 years postsurgery and every 3–6 months thereafter. Routine liver function tests, tumor markers tests, coagulation tests, and abdominal imaging (MRI, CT, or ultrasonography) were performed at each follow-up visit. Thoracic CT or other imaging scans were performed when tumor recurrence was suspected. Primary outcomes were overall survival (OS), calculated from the commencement date of conversion therapy until death, and recurrence-free survival (RFS), calculated from the commencement date of conversion hepatectomy until recurrence or last follow-up visit. Secondary outcomes were tumor response rate, time of hepatic hilum inflow occlusion, intraoperative blood loss, and adverse events.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square, Fisher’s exact, and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare categorical variables between groups, whereas the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous data. Missing values were imputed using a fully conditional specification regression model for continuous values and a discriminant function for categorical values. Survival curves were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to compare differences. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to assess significant prognostic factors with respect to OS and RFS. Differences between results were considered statistically significant at a two-sided P-value <0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program (version 26.0; SPSS Inc.).

Results

Patient characteristics

We retrospectively analyzed 424 eligible patients who underwent HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy between January 2016 and December 2022, and the study inclusion criteria are shown in Figure 1. Among them, 312 (73.9%) and 112 (26.1%) patients achieved CR/PR (responders) and experienced SD/PD (nonresponders), respectively. Baseline and clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The two cohorts exhibited similar profiles across most variables, with the exception of microvascular invasion (MVI) and ALB levels. Most patients in both cohorts were male [256 (82.1%) and 96 (85.7%) in the CR/PR and SD/PD cohorts, respectively]. The patients were relatively young, with a median age of 53 and 52 years in the responder and nonresponder groups, respectively. The majority of patients present with Child-Pugh Class A liver function, hepatitis B virus infection, and large tumor size.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram summarizing the patient enrollment process of this study. CR, complete response; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients.

| Variable | CR/PR (n=312) | SD/PD (n=112) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (range) | 53 (16–79) | 52 (11–82) | 0.844 |

| Sex (male/female) | 256/56 (82.1/17.9) | 96/16 (85.7/14.3) | 0.376 |

| ECOG PS (0/1) | 238/74 (76.3/23.7) | 82/30 (73.2/26.8) | 0.732 |

| Child-Pugh class (Class A/Class B) | 310/2 (99.4/0.6) | 111/1 (99.1/0.9) | 0.785 |

| Hepatitis B (yes/no) | 286/26 (91.7/8.3) | 97/15 (86.6/13.4) | 0.068 |

| Tumor size | 0.960 | ||

| ≤3 cm | 10 (3.2) | 3 (2.7) | |

| 3–5 cm | 27 (8.7) | 10 (8.9) | |

| ≥5 cm | 275 (88.1) | 99 (88.4) | |

| Site | 0.242 | ||

| Left | 54 (17.3) | 15 (13.4) | |

| Right | 223 (71.5) | 89 (79.5) | |

| Bilobar | 35 (11.2) | 8 (7.1) | |

| HAIC cycles (≤2/3–4/ >4) | 175/108/29 (56.1/34.6/9.3) | 60/42/10 (53.6/37.5/8.9) | 0.861 |

| Tumor number (solitary/multiple) | 183/129 (58.7/41.3) | 61/51 (54.5/45.5) | 0.442 |

| MVI | 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 261 (83.7) | 78 (69.6) | |

| 1 | 40 (12.8) | 29 (25.9) | |

| 2 | 11 (3.5) | 5 (4.5) | |

| BCLC stage | 0.981 | ||

| A | 123 (39.4) | 43 (38.4) | |

| B | 79 (25.3) | 29 (25.9) | |

| C | 110 (35.3) | 40 (35.7) | |

| CNLC stage | 0.270 | ||

| I | 116 (37.2) | 43 (38.4) | |

| II | 84 (26.9) | 30 (26.8) | |

| III | 112 (35.9) | 39 (34.8) | |

| Pre-HAIC serum tests | |||

| Platelets, ×103/μl (<100/≥100) | 9/303 (2.9/97.1) | 1/111 (0.9/99.1) | 0.233 |

| PT (≤13.5/>13.5) | 291/21 (93.2/6.8) | 103/9 (92/8) | 0.695 |

| AFP, ng/ml (<400/≥400) | 124/188 (39.7/60.3) | 57/55 (50.9/49.1) | 0.917 |

| PIVKA-II, mAU/ml (<40/≥40) | 26/286 (8.3/91.7) | 8/104 (7.1/92.9) | 0.768 |

| CA19-9, U/ml (≤35/>35) | 209/103 (67.0/33.0) | 81/31 (72.3/27.7) | 0.115 |

| ALB, g/l (≤35/>35) | 22/290 (7.1/92.9) | 1/111 (0.9/99.1) | 0.011 |

| TBIL, μmol/l (≤20.5/>20.5) | 264/48 (84.6/15.4) | 101/11 (90.2/9.8) | 0.145 |

| Preoperative serum tests | |||

| Platelets, ×103/μl (<100/≥100) | 37/275 (11.9/88.1) | 11/101 (9.8/90.2) | 0.745 |

| PT (≤13.5/>13.5) | 297/15 (95.2/4.8) | 110/2 (98.2/1.8) | 0.198 |

| AFP, ng/ml (<400/≥400) | 232/80 (74.4/25.6) | 70/42 (62.5/37.5) | 0.008 |

| PIVKA-II, mAU/ml (<40/≥40) | 103/209 (33.0/67.0) | 12/100 (10.7/89.3) | <0.001 |

| CA19-9, U/ml (≤35/>35) | 226/86 (72.4/27.6) | 77/35 (68.8/31.2) | 0.459 |

| ALB, g/l (≤35/>35) | 23/289 (7.4/92.6) | 3/109 (2.7/97.3) | 0.051 |

| TBIL, μmol/l (≤20.5/>20.5) | 286/26 (91.7/8.3) | 109/3 (97.3/2.7) | 0.042 |

| Postoperative serum tests | |||

| AFP, ng/ml (≤25/>25) | 252/60 (80.8/19.2) | 72/40 (64.3/35.7) | 0.001 |

| PIVKA-II, mAU/ml (<40/≥40) | 257/55 (82.4/17.6) | 76/36 (67.9/32.1) | 0.004 |

| CA19-9, U/ml (≤35/>35) | 242/70 (77.6/22.4) | 85/27 (75.9/24.1) | 0.771 |

| ALB, g/l (≤35/>35) | 17/295 (5.4/94.6) | 3/109 (2.7/97.3) | 0.163 |

| TBIL, μmol/l (≤20.5/>20.5) | 285/27 (91.3/8.7) | 107/5 (95.5/4.5) | 0.209 |

AFP, alpha‐fetoprotein; ALB, albumin; BCLC, Barcelona‐Clinic Liver Cancer; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CNLC, The China liver cancer; CR, complete response; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score; HAIC, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; INR, international normalized ratio; IQR, interquartile range; MVI, microvascular invasion; PD, progressive disease; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II; PR, partial response; PT, prothrombin time; SD, stable disease; TBIL, total bilirubin.

Subgroup analyses

Survival according to tumor response and cycles of HAIC

The median follow-up period for all patients was 25.9 (Range: 2.9–80.1) months. The median OS was not achieved in the whole cohort, with 96.5, 76.8, and 66.7% survival, and the median RFS was 14.9 (95% CI: 11.455–18.412) months, with 55.7, 36.1, and 33.5% survival at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively. Median OS and RFS were not achieved with values of 53.2 months for the CR/PR group [hazard ratio (HR): 2.581; 95% CI: 1.646–4.046; P<0.001), and 17.7 months and 9.7 months for the SD/PD group (HR: 1.565; 95% CI: 1.189–2.062; P=0.001), respectively (Fig. 2A, B). The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS rates were 97.6, 82.3, and 74.2% for CR/PR patients, and 93.3, 62.5, and 46.5% for SD/PD patients, respectively. The RFS rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 60.1, 39.9, and 38.4% for CR/PR patients and 43.4, 25.3, and 20.5% for SD/PD patients, respectively.

Figure 2.

Survival was shown according to the tumor response and cycles of HAIC. The OS (A) and RFS (B) in patients with tumor response (CR/PR vs SD/PD) according to mRECIST criteria. The OS (C) and RFS (D) of patients who achieved CR/PR in 1–2 cycles and 4–6 cycles of HAIC. The OS (E) and RFS (F) of patients who achieved CR/PR in 4–6 cycles of HAIC and SD/PD. CR, complete response; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; mRECIST, modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RFS, recurrence-free survival; SD, stable disease.

OS was not achieved in patients who experienced CR/PR in 1–2 cycles and 4–6 cycles of HAIC (HR: 0.880; 95% CI: 0.479–1.617; P=0.680; Fig. 2C). In contrast, the median RFS was 17.7 and 15.3 months for the groups administered with 1–2 and 4–6 cycles of HAIC (HR: 1.108; 95% CI: 0.811–1.515; P=0.519; Fig. 2D). Median OS was not attained in patients who achieved CR/PR following 4–6 cycles of HAIC and SD/PD was not achieved, with a value of 53.2 months (HR: 2.898; 95% CI: 1.671–5.025; P<0.001; Fig. 2E). In contrast, the median RFS was 15.3 months for the CR/PR group administered with 4–6 cycles of HAIC and 9.7 months for the SD/PD group (HR: 1.493; 95% CI: 1.090–2.047; P=0.013; Fig. 2F).

Survival according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stages A, B, and C were identified in 123, 79, and 110 patients with CR/PR and 43, 29, and 40 patients with SD/PD, respectively. Median OS was not achieved in the CR/PR and SD/PD cohorts of patients with BCLC stage A, with a value of 62.3 months (HR: 1.561; 95% CI: 0.660–3.682; P=0.313; Fig. 3A). In contrast, the median RFS of these patients was 45.7 and 14.1 months for the CR/PR and SD/PD groups, respectively (HR: 1.85; 95% CI: 1.150–2.970; P=0.012; Fig. 3B). Median OS was not achieved in the CR/PR and SD/PD groups of patients with BCLC stage B (HR: 3.781; 95% CI: 1.424–10.039; P=0.008; Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Survival was shown according to BCLC staging system. The OS (A, C, E) and RFS (B, D, F) stratified according to BCLC stage A, stage B, and stage C. BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

In contrast, the median RFS of these patients was 13.2 and 9.7 months for the CR/PR and SD/PD groups, respectively (HR: 1.131; 95% CI: 0.659–1.939; P=0.655; Fig. 3D). Moreover, higher OS and RFS values were observed in CR/PR patients than in SD/PD patients with BCLC stage C (median OS: not achieved vs. 39.6 months, HR: 3.402; 95% CI: 1.778–6.513, P<0.001; median RFS: 12.9 vs. 5.8 months, HR: 1.705; 95% CI: 1.105–2.632; P=0.016; Fig. 3E, F).

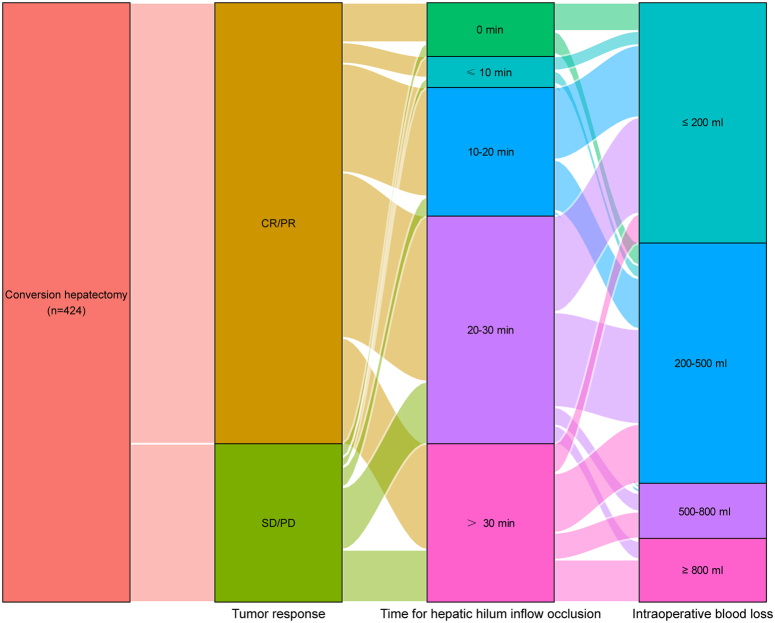

Relationship between tumor response, hepatic hilum inflow occlusion, and intraoperative blood loss

A Sankey diagram was used to further illustrate the relationship between tumor response, hepatic hilum inflow occlusion, and intraoperative blood loss (Fig. 4). The hepatic hilum inflow occlusion time ranged from 10 to 30 min for the CR/PR cohort and 20–30 min and >30 min for the SD/PD cohort. Additionally, intraoperative blood loss was lower in the responder group than it was in the nonresponder group.

Figure 4.

Sankey diagram is presented to visualize the relationship between the tumor response, hepatic hilum inflow occlusion duration, and intraoperative blood loss. CR, complete response; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease.

Surgical information and postoperative complications

The surgical information and postoperative complications of patients are presented in Table 2. No significant differences were observed between both cohorts regarding operative time, hepatic hilum inflow occlusion, or intraoperative red blood cell (RBC) transfusion. The responder group showed less intraoperative blood loss (P=0.046) and a shorter occlusion duration (P=0.041) than the nonresponder group did. The postoperative complication rates were comparable between both cohorts, including pulmonary and abdominal infections, abdominal bleeding, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, bile leakage, liver function abnormalities, obstructive jaundice, abdominal wall hernia, peritoneal and pleural effusion, and thrombosis.

Table 2.

Surgical information and postoperative complications.

| CR/PR (n=312) | SD/PD (n=112) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical information | |||

| Operative time, n (range, min) | 143 (120–190) | 145 (125–210) | 0.334 |

| Intraoperative blood loss, median (range, ml) | 300 (30–2100) | 300 (50–3000) | 0.046 |

| Hepatic hilum inflow occlusion, n (%) | 284 (91.0) | 102 (91.1) | 0.988 |

| Occlusion duration, median (range, min) | 23 (5–94) | 26 (5–101) | 0.041 |

| Intraoperative RBCs transfusion, n (%) | 33 (10.6) | 12 (10.7) | 0.968 |

| RBCs, n (range, units) | 2 (2.0–4.0) | 2 (2.0–4.0) | 0.442 |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | |||

| Pulmonary infection | 5 (1.6) | 2 (1.8) | 1.000 |

| Abdominal infection | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.9) | 1.000 |

| Abdominal bleeding | 3 (1.0) | 0 | 0.569 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.8) | 0.611 |

| Bile leakage | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.8) | 0.611 |

| Liver function abnormalities | 7 (2.2) | 2 (1.8) | 1.000 |

| Obstructive jaundice | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.9) | 0.459 |

| Abdominal wall hernia | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0.264 |

| Peritoneal and pleural effusions | 6 (1.9) | 2 (1.8) | 1.000 |

| Thrombosis | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1.000 |

CR, complete response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RBC, Red Blood Cell; SD, stable disease.

Risk factors analysis

The univariate analysis showed that 13 and 19 factors negatively affected the OS and RFS rates, respectively. The multivariate analysis showed that tumor response (HR: 1.969; 95% CI: 1.224–3.167), differentiation (HR: 1.379; 95% CI 1.077–1.766), pre-HAIC systemic immune-inflammation index (SII, HR: 2.315; 95% CI: 1.316–4.075), levels of postoperative AFP (HR: 2.753; 95% CI, 1.350–5.615), and postoperative PIVKA-II (HR: 2.238; 95% CI: 1.360–3.683), were independent risk factors for poor OS. For RFS, age (HR: 1.612; 95% CI: 1.047–2.480), MVI status (HR: 2.118; 95% CI: 1.529–2.935), pre-HAIC neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR; HR: 1.742; 95% CI: 1.132–2.680), preoperative systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI; HR: 1.608; 95% CI: 1.154–2.241), postoperative AFP levels (HR: 2.184; 95% CI: 1.418–3.366), and postoperative PIVKA-II (HR: 2.983; 95% CI: 2.186–4.071) were the independent risk factors. The results for the whole cohort are shown in Tables S1 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/D308 and S2, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JS9/D309). For the responder cohort, differentiation (HR: 1.403; 95% CI: 1.007–1.953), pre-HAIC SII (HR: 2.702; 95% CI: 1.205–6.061), Preoperative NLR (HR: 2.92; 95% CI: 1.08–7.891), and levels of postoperative AFP (HR: 2.92; 95% CI: 1.048–8.133) were independent risk factors for poor OS. For RFS, multiple tumor number (HR: 1.586; 95% CI: 1.148–2.19), differentiation (HR: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.058–1.43), MVI status (HR: 2.142; 95% CI: 1.454–3.153), postoperative AFP levels (HR: 2.314; 95% CI: 1.306–4.099), postoperative PIVKA-II (HR: 3.336; 95% CI: 2.36–4.714), and ECOG score (HR: 1.65; 95% CI: 1.141–2.387) were the independent risk factors. The prognostic factors for the responders cohort are shown in Table S3 (Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/D310 and S4, Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/JS9/D311).

Discussion

In this multicenter cohort study, patients with HCC who achieved CR/PR and underwent HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy exhibited a longer OS and RFS than those who achieved SD/PD did. Additionally, no significant difference was observed in survival between patients who achieved CR/PR after 1–2 cycles and those after 4–6 HAIC cycles. However, patients who achieved CR/PR after 4–6 HAIC cycles exhibited longer OS and RFS than those who achieved SD/PR did. Postoperative complications in the responder group were similar to those in the nonresponder group. Postoperative surgical pathology indicated that patients who achieved CR/PR had a lower incidence of MVI compared to those who did not achieve CR/PR. Responders were more likely to show a greater reduction in AFP and PIVKA-II levels than nonresponders. Patients with well-preserved liver function and a low ECOG score underwent conversion hepatectomy when they achieved CR/PR, which significantly reduced intraoperative bleeding and improved oncological outcomes. MVI is a critical independent risk factor of HCC19. A recent phase III randomized controlled trial suggested that postoperative adjuvant HAIC significantly improves disease-free survival in patients with HCC and MVI20. In this study, the proportion of patients with MVI who achieved CR/PR was lower than that of patients who achieved SD/PD, indicating that responders exhibited a longer survival time than that of nonresponders.

Curative liver resection is vital for achieving long-term survival in patients with HCC21. However, more than 50% of patients with advanced disease are not candidates for radical resection because of factors such as large tumor burden, vascular invasion, or metastasis at the time of diagnosis, resulting in a poor prognosis22,23. Conversion therapy reduces the tumor volume and potentially leads to downstaging, making surgical resection a viable option for patients with initially unresectable tumors, thereby significantly improving their survival prospects. Notably, the survival rates of these patients can be comparable to those who initially underwent curative hepatectomy14,24. Conversion treatment reduces the tumor volume or even leads to downstaging to achieve the aim of making surgical resection possible14. Nevertheless, a high rate of postoperative recurrence remains a major clinical challenge for the long-term survival of patients undergoing conversion surgery7. Patients treated with conversion hepatectomy are likely to be at a high risk for tumor recurrence due to multiple unfavorable prognostic factors, such as larger tumor volume, multiple lesions, and vascular invasion14,25. Effective conversion therapy leads to tumor remission and offers an opportunity for patients to undergo safe conversion surgical resection. Moreover, overuse of conversion treatments such as HAIC may cause deterioration of liver function, even delaying optimal surgical timing. Consequently, the timing of the conversion surgery is extremely important.

Transarterial interventional therapy is the most commonly used nonsurgical treatment for HCC26. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and HAIC are widely used for the treatment of HCC and are regarded as important means of conversion13,27. Recent studies have reported that HAIC yields satisfactory efficacy in various stages of HCC8,20,28. For resectable HCC beyond the Milan criteria, HAIC has been proven effective in reducing the risk of postoperative recurrence20. For patients with HCC and portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT), cotreatment with HAIC and sorafenib provides a significant survival advantage over sorafenib monotherapy8. The efficacy of HAIC-based conversion therapy has been investigated at multiple centers, yielding satisfactory results. In this study, 37.5% patients have CNLC stage I disease. Most patients with CNLC stage Ib (maximum diameter of the tumor >5 cm) did not undergo surgical resection at the initial diagnosis due to insufficient remnant liver volume. HAIC is one of the effective treatments for these patients. Patients with CNLC stage Ia account for a small proportion, less than 10 cases. According to medical records, the doctor presented patients with the option of surgery or other therapeutic approaches following their diagnosis. However, the majority of them declined surgical treatment due to limited economic resources, unwillingness to bear the risk of liver resection, advanced age, religious beliefs, or cultural background. Hence, they opted for interventional treatments, such as HAIC, which offered survival benefits. Deng et al.28 showed that compared to TACE, HAIC has led to superior local tumor control, higher conversion rates, and induced longer PFS for patients with potentially resectable huge single HCC. A multicenter, phase III, prospective randomized study revealed that HAIC was associated with better survival and higher conversion rates than TACE in the treatment of large single HCC without vascular invasion and metastasis13. The results of our analysis showed an objective response rate (ORR) of 73.6%. Moreover, the adverse effects were not significantly different between the two cohorts. Notably, the efficacy of HAIC could be further potentiated by combining it with other anticancer treatments. The ORR of patients undergoing HAIC in combination with TACE was 65.9%, with a 48.8% conversion rate29. Furthermore, 31.6% of the patients who underwent conversion resection following combination therapy achieved a pathological CR (pCR), suggesting that HAIC-based combination treatment exhibited better efficacy than TACE alone did30. HAIC combined with TKI and anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1) therapy also yielded superior oncological outcomes compared to HAIC alone or HAIC combined with an anti-PD-1 agent for the treatment of HCC11.

In this study, most patients who exhibited SD received conversion treatment due to the presence of large tumor volumes and insufficient remnant liver volumes at the initial visit. Tumor shrinkage did not achieve CR/PR after treatment. Conversion hepatectomy was performed when the residual liver volume was sufficient after treatment and the patient was strongly willing to undergo surgery. During the study period, four patients experienced PD. Two patients had primary lesions that initially achieved PR, but relapsed with the emergence of new lesions in the same liver lobe. One patient achieved a CR after treatment for an intrahepatic lesion, but later developed a new single lesion in the lungs. Another patient demonstrated significant necrosis of the intrahepatic lesion, followed by the development of a portal vein tumor thrombus. After evaluation, and in accordance with the patient’s willingness, a liver resection was performed.

Currently, several challenges remain in administering conversion therapy for HCC. One notable issue is the relatively low success rate of conversion (approximately 10–20%), which suggests that most patients are unable to undergo surgical resection14,31,32. Additionally, whether adjuvant therapy is required in patients undergoing conversion resection remains controversial. Although surgical resection remains the mainstay treatment modality for patients after successful conversion, some studies have shown that survival after conversion surgery is related to pathological remission24,33,34. These findings imply that even if the patient undergoes surgical resection, survival outcomes may not be improved. While Sun et al.35 proposed that if the tumor achieves CR, postoperative adjuvant therapy may not be required. Studies by Sun et al.35 and Pan et al.36 reported that if tumor markers such as AFP do not drop to normal levels after conversion hepatectomy, postoperative adjuvant therapy may reduce the risk of tumor recurrence and, thus improve survival. Deng et al.12 also reported similar findings, showing that persistently elevated postoperative AFP and PIVKA-II levels are independent risk factors for tumor recurrence in patients undergoing HAIC-based conversion resection, which influences patient outcomes. Furthermore, the original tumor stage is a significant predictor of survival after conversion surgery. Current research suggests that patients with BCLC stage C disease who achieved CR/PR and were treated with conversion hepatectomy had a better prognosis than those who achieved SD/PD. However, the OS and RFS curves of patients with BCLC stages A and B overlapped to varying degrees. Another study suggested that surgery is not the only effective treatment approach for patients after a successful conversion treatment. Systematic therapy and local treatment can also enable the long-term survival of patients35.

HAIC-based conversion therapy for tumors in patients who achieve CR/PR often results in extensive necrosis of tumor cells, and the blood supply to the liver segment or lobe where the lesion is located is relatively reduced. This results in shorter hepatic portal occlusion time and less intraoperative bleeding during hepatectomy. Consistent with previous reports, our study demonstrated the reduction of hepatic portal occlusion time and intraoperative bleeding in the responder cohort compared to the nonresponder cohort. In addition, patients who achieved CR/PR and subsequently underwent surgical resection exhibited a more favorable prognosis than those who achieved SD/PD, which is related to the number of residual active tumors in the liver. On the other hand, studies have also reported that tumors can be infiltrated by various distinct immune cell subsets after HAIC therapy, and that patients with satisfactory efficacy have higher densities of immune cells11,37. Oxaliplatin, the key reagent in FOLFOX-HAIC, is a widely used antitumor agent38. Studies have revealed that chemotherapeutic drugs trigger programmed cell death in tumor cells39,40, Potentially inducing antitumor immunity that synergizes with chemotherapy41. In this study, patients who achieved CR/PR demonstrated extensive necrotic areas in their treated tumors and a robust antitumor immune response. This profound and long-lasting immune effect may underlie the superior outcomes observed in the responder group that underwent conversion resection compared to the nonresponder group. However, further investigation is required to elucidate the specific in-depth mechanisms.

One of the major limitations of this study is its retrospective design, which could have led to selection and information biases. Although most baseline characteristics between the two cohorts were comparable, it was essential to exclude residual selection bias and confounding effects caused by unknown or unmeasured factors when randomization was not possible. In addition, our multicenter study design entailed considerable variability in the treatment time of the patients as well as the surgical experience and techniques across different surgeons at each center. Despite these limitations, our findings demonstrate generalizability and external validity, providing valuable insights into the application of HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy in contemporary medical practice.

Conclusions

HAIC-based conversion therapy responders who underwent a liver resection presented with longer OS and RFS duration, shorter occlusion duration, and less intraoperative blood loss than nonresponders did. Therefore, conversion surgery should be considered when CR or PR is achieved after HAIC treatment. Our findings may be useful in guiding surgeons and patients in decision-making regarding HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of SYSUCC (No. B202031801). This study was a retrospective review of medical records.

Source of funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82303156, No. 82172579); Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou (No. 2023A04J1777, No. 2023A04J1781); Clinical Trials Project (5010 Project) of Sun Yat-sen University (No. 5010-2017009, No. 5010-2023001).

Author contribution

M.D.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, and visualization, and writing – original draft; C.Z. and D.L.: data curation, methodology, and writing – original draft; R.G.: formal analysis, software, and visualization; C.L.: methodology, software, and visualization; H.C. and W.Q.: methodology; H.C.: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, and writing – review and editing; R.G.: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, supervision, and writing – review and editing; Z.C.: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, supervision, and writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

1. Name of the registry: Research Registry; Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy-based conversion hepatectomy in responders versus nonresponders with hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter cohort study.

2. Unique identifying number or registration ID: researchregistry10316.

3. Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-theregistry#.home/registrationdetails/664b4d8cfd972d0028c5eb32/.

Guarantor

Zubing Chen and Rongping Guo.

Data availability statement

All data used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge and express their deepest gratitude to the participants of this research.

Footnotes

Min Deng, Chong Zhong, and Dong Li contributed equally to this work.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.lww.com/international-journal-of-surgery.

Contributor Information

Min Deng, Email: 103561732@qq.com.

Chong Zhong, Email: zhongchongtcmg@outlook.com.

Dong Li, Email: 47723543@qq.com.

Renguo Guan, Email: dengmin0207@126.com.

Carol Lee, Email: carolleecuhk@outlook.com.

Huanwei Chen, Email: zjwsysucc@outlook.com.

Wei Qin, Email: dengmin0207@outlook.com.

Hao Cai, Email: 263385180@qq.com.

Rongping Guo, Email: guorongpingsysucc@outlook.com.

Zubing Chen, Email: chenzubingsysush@outlook.com.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma, eng. N Eng J Med 2019;380:1450–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anwanwan D, Singh SK, Singh S, et al. Challenges in liver cancer and possible treatment approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2020;1873:188314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilgoff IS, Kahlstrom E, MacLaughlin E, et al. Long-term ventilatory support in spinal muscular atrophy. J Pediatr 1989;115:904–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krenzien F, Schmelzle M, Struecker B, et al. Liver transplantation and liver resection for cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of long-term survivals. J Gastrointest Surg 2018;22:840–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang X, Xu H, Zuo B, et al. Downstaging and resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with extrahepatic metastases after stereotactic therapy. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2021;10:434–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou J, Sun H, Wang Z, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (2019 Edition). Liver Cancer 2020;9:682–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He M, Li Q, Zou R, et al. Sorafenib plus hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin vs sorafenib alone for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein invasion: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:953–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi JH, Chung WJ, Bae SH, et al. Randomized, prospective, comparative study on the effects and safety of sorafenib vs. hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2018;82:469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nouso K, Miyahara K, Uchida D, et al. Effect of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy of 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in the Nationwide Survey of Primary Liver Cancer in Japan. Br J Cancer 2013;109:1904–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mei J, Li SH, Li QJ, et al. Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy improves the efficacy of hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2021;8:167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng M, Lei Q, Wang J, et al. Nomograms for predicting the recurrence probability and recurrence-free survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after conversion hepatectomy based on hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy: a multicenter, retrospective study. Int J Surg 2023;109:1299–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li QJ, He MK, Chen HW, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus transarterial chemoembolization for large hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:150–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu XD, Huang C, Shen YH, et al. Downstaging and resection of initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with tyrosine kinase inhibitor and anti-PD-1 antibody combinations. Liver Cancer 2021;10:320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao HT, Cai JQ. Chinese expert consensus on neoadjuvant and conversion therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2021;27:8069–8080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathew G, Agha R, Group S. STROCSS 2021: strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case-control studies in surgery. Int J Surg 2021;96:106165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li S, Deng M, Wang Q, et al. Transarterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFOX could be an effective and safe treatment for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Oncol 2022;2022:2724476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2010;30:52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim KC, Chow PK, Allen JC, et al. Microvascular invasion is a better predictor of tumor recurrence and overall survival following surgical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma compared to the Milan criteria. Ann Surg 2011;254:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li SH, Mei J, Cheng Y, et al. Postoperative adjuvant hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFOX in hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion: a multicenter, phase III, randomized study. J Clin Oncol 2023;41:1898–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: the 2022 update. J Hepatol 2022;76:681–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.European Association for the Study of the Liver . Electronic address eee, European Association for the Study of the L, EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018;69:182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021;7:6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou H, Song T. Conversion therapy and maintenance therapy for primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci Trends 2021;15:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang W, Hu B, Han J, et al. Surgery after conversion therapy with PD-1 inhibitors plus tyrosine kinase inhibitors are effective and safe for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a pilot study of ten patients. Front Oncol 2021;11:747950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sieghart W, Hucke F, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Transarterial chemoembolization: modalities, indication, and patient selection. J Hepatol 2015;62:1187–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He MK, Le Y, Li QJ, et al. Hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy using mFOLFOX versus transarterial chemoembolization for massive unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective non-randomized study. Chin J Cancer 2017;36:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng M, Cai H, He B, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus transarterial chemoembolization, potential conversion therapies for single huge hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective comparison study. Int J Surg 2023;109:3303–3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B, Qiu J, Zheng Y, et al. Conversion to resectability using transarterial chemoembolization combined with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Open 2021;2:e057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan Y, He W, Yang Z, et al. TACE-HAIC combined with targeted therapy and immunotherapy versus TACE alone for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumour thrombus: a propensity score matching study. Int J Surg 2023;109:1222–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee HS, Choi GH, Choi JS, et al. Surgical resection after down-staging of locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma by localized concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:3646–3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Byun HK, Kim HJ, Im YR, et al. Dose escalation by intensity modulated radiotherapy in liver-directed concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced BCLC stage C hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiother Oncol 2019;133:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu XD, Huang C, Shen YH, et al. Hepatectomy after conversion therapy using tyrosine kinase inhibitors plus anti-PD-1 antibody therapy for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2023;30:2782–2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li B, Wang C, He W, et al. Watch-and-wait strategy vs. resection in patients with radiologic complete response after conversion therapy for initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity score-matching comparative study. Int J Surg 2024;110:2545–2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun HC, Zhou J, Wang Z, et al. Chinese expert consensus on conversion therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (2021 edition). Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2022;11:227–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan Y, Yang L, Cao Y, et al. Factors influencing the prognosis patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing salvage surgery after conversion therapy. Transl Cancer Res 2023;12:1852–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deng M, Li S, Wang Q, et al. Real-world outcomes of patients with advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma treated with programmed cell death protein-1-targeted immunotherapy. Ann Med 2022;54:803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qin S, Bai Y, Lim HY, et al. Randomized, multicenter, open-label study of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin versus doxorubicin as palliative chemotherapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma from Asia. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3501–3508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Gao W, Shi X, et al. Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin, eng. Nature 2017;547:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Xia S, et al. Gasdermin E suppresses tumour growth by activating anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2020;579:415–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang R, Xu J, Zhang B, et al. Ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in anticancer immunity. J Hematol Oncol 2020;13:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.