Abstract

This study investigated the impact of menopause on the progression and management of common benign gynecological conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome, endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and adenomyosis. These conditions often present with menstruation-related symptoms such as irregular cycles, heavy bleeding, and pelvic pain. While these symptoms typically subside after menopause, the underlying pathology of such benign gynecological conditions may be differentially affected by the physiological changes associated with menopause, sometimes leading to exacerbation or additional management challenges. Although rare, the potential for malignant transformation remains a concern. This study aims to elucidate the shifts in management strategies from the reproductive years to postmenopause. It highlights the necessity for a tailored approach to hormone therapy and surgical interventions based on the individual patient's health profile and the specific characteristics of each condition.

Keywords: Adenomyosis, Endometriosis, Leiomyoma, Polycystic ovary syndrome, Postmenopause

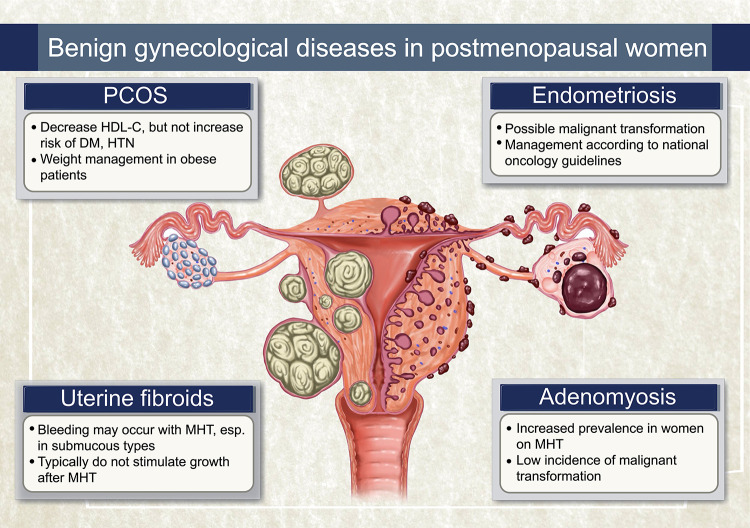

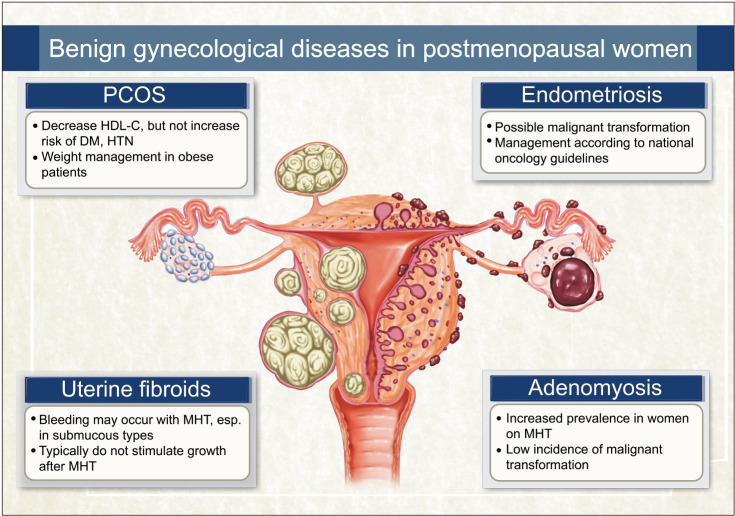

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and adenomyosis are prevalent gynecological conditions in women of reproductive age. These conditions frequently present a variety of symptoms associated with menstruation. For instance, PCOS can lead to irregular menstrual cycles, abnormal bleeding, and infertility [1], while endometriosis is known to cause dysmenorrhea, significantly impairing quality of life, and is also a substantial contributor to infertility [2,3]. Both uterine fibroids and adenomyosis are causes of dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding [4,5]. Thus, many gynecological disorders are linked to menstrual symptoms and are underlying causes of infertility.

Consequently, after menopause, symptoms related to menstruation naturally cease to be clinically problematic. In certain cases, it is advisable to manage the symptoms conservatively in symptomatic women, avoiding surgical intervention until the onset of menopause [6]. However, management should not solely focus on symptoms up to menopause; attention is also required for postmenopausal care. Alongside various physiological changes during menopause, these conditions can exert additional impacts on overall health, and although rare, there is the potential for malignant transformation of pre-existing lesions [2,7]. Therefore, this paper aims to review the management of benign gynecological diseases that primarily cause symptoms in reproductive-aged women, with a focus on their management in postmenopausal women.

POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME

Diagnosis

While individuals with PCOS may exhibit a range of symptoms, the condition commonly presents with irregular menstruation, infertility, and signs of androgen excess such as hirsutism and acne [8]. Moreover, it is associated with multiple cardiovascular risk factors including insulin resistance, hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance, and dyslipidemia. There are also correlations with obstructive sleep apnea, endometrial cancer, and mood disorders. However, a longitudinal study by Carmina et al. [9], which tracked 193 PCOS patients aged 20–25 years over two decades, indicates that with increasing age, menstruation tends to regularize, ovarian size decreases, and the number of follicles reduces, leading to the disappearance of polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM). Furthermore, blood androgen levels were statistically significantly reduced after a decade of follow-up. Notably, irregular menstruation, a major symptom and one of the diagnostic criteria of PCOS, naturally ceases post-menopause. Due to these changes with aging, the diagnosis of PCOS in postmenopausal women becomes challenging. According to the 2023 international evidence-based guidelines for PCOS, a diagnosis can be established if there was a previous diagnosis of PCOS, or a history of long-term oligo-amenorrhea and hyperandrogenism between the ages of 20 and 40, and/or evidence of PCOM in menopausal women [10]. In postmenopausal women, typical diagnostic criteria for PCOS, such as menstrual irregularities and PCOM, cannot be applied. Thus, clinical hyperandrogenism is considered the only applicable diagnostic criterion in postmenopause.

The prevalence of hyperandrogenism in postmenopausal women is not precisely known. This uncertainty arises because there are no established cut-off levels for serum androgen levels in postmenopausal women. There is a limited number of studies comparing serum androgen levels in postmenopausal women, and even among these studies, conflicting results are observed regarding whether postmenopausal women with PCOS exhibit higher androgen levels compared to non-PCOS controls [11,12,13,14].

Furthermore, not all cases presenting with symptoms of hyperandrogenism should be diagnosed as PCOS. Particularly in postmenopausal women, if hyperandrogenism worsens over time or new symptoms emerge, it is prudent to suspect an androgensecreting tumor or hyperthecosis, necessitating careful monitoring and follow-up [10]. It has been reported that ovarian hyperthecosis, which presents with hyperandrogenism, is found in 9.3% of postmenopausal women, whereas the prevalence of androgen-secreting ovarian tumors in postmenopausal women with hyperandrogenism is about 2.7% [15]. For ovarian hyperthecosis and androgen-secreting ovarian tumors, a serum total testosterone level of over 150 ng/dL is indicative, a threshold generally not exceeded in PCOS cases [16].

Clinically, PCOS is characterized by persistent or increasing hirsutism without virilizing symptoms, a history of oligo/amenorrhea, later onset of menopause, overweight, and abdominal obesity, whereas ovarian hyperthecosis typically presents a gradual development of virilizing symptoms and an isolated increase in testosterone, along with bilateral ovarian enlargement [15]. In the case of androgen-secreting ovarian tumors, rapid onset of virilizing symptoms occurs alongside increased levels of testosterone, androstenedione, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone, generally accompanied by a mass in one ovary [15].

Cardiometabolic risk of PCOS

PCOS is associated with multiple cardiovascular risk factors in women of reproductive age, notably obesity, insulin resistance, and impaired fibrinolysis, leading to higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome [8]. Menopause in women is linked with weight gain, decreased sex hormonebinding globulin (SHBG), and a relative increase in androgens. These menopausal changes may exacerbate the negative metabolic impacts associated with PCOS, raising concerns about increased cardiometabolic risk. A recent meta-analysis reported that peri/postmenopausal women with PCOS have statistically significant higher values in various parameters, such as body mass index (BMI), waist-hip ratio, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance, fasting insulin, SHBG, and systolic blood pressure, compared to controls and high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) was significantly lower [17]. However, when analyzing women with similar BMI, no differences were found in the PCOS group other than decreased HDL-C and increased blood testosterone and hirsutism, and no significant differences were observed in the incidence of hypertension and diabetes when comparing similar age groups. This suggests that the increased cardiometabolic risk in peri/postmenopausal women with PCOS might be attributable to associated weight gain, implying that the specific cardiometabolic risks linked to PCOS may diminish post-menopause.

Vasomotor symptoms and endometrial cancer risk of PCOS

Conflicting results have been reported regarding menopausal symptoms in women with PCOS. While one study reported more severe symptoms such as hot flashes and sweating [14], others found no significant difference [18,19], leaving the issue unresolved. Regarding endometrial cancer, there is a potential for increased risk with PCOS. However, most women with PCOS take combined oral contraceptives or progestins for endometrial protection, which may counteract this risk. A 21-year follow-up study of a small patient cohort reported no occurrences of endometrial cancer [14].

Management

As previously mentioned, the majority of cardiometabolic comorbidities are predominantly influenced by the common co-occurrence of excess weight and PCOS, particularly during the late-reproductive years and menopause. Thus, for obese patients with PCOS in this age group, weight management is necessary for mitigating cardiometabolic risk [17].

ENDOMETRIOSIS

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

Endometriosis is a prominent condition known to cause dysmenorrhea and infertility in women of reproductive age, affecting 6%–10% of this group. In postmenopausal women, the prevalence varies according to different reports but is generally known to be between 2%–5% [20,21,22,23]. Despite numerous theories surrounding its pathophysiology, endometriosis remains a perplexing condition. The complexity intensifies in postmenopausal endometriosis, as it is unclear whether it persists from previous disease or represents newly developed lesions.

Regardless of the continuation of a previous disease or it develops de novo, estrogen is known to play a vital role in the development of the disease [24]. In postmenopausal women, the source of estrogen is mainly menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) and most cases have been reported to occur after estrogen only therapy, although there have been also reports of occurrences with combined hormone therapy [2]. In the cases without hormone therapy, the source of estrogen is primarily the peripheral conversion of androgens, especially in the adipose tissue and skin [25]. Another hypothetical source of estrogen is the increased aromatase activity found within endometriotic lesions.

Malignant transformation of endometriosis

Endometriosis is associated with a higher risk of ovarian cancers, particularly the clear cell and endometrioid histotypes, as well as breast and thyroid cancers. However, the increase in absolute risk compared to women in the general population is low [26]. As a result, clinicians often provide reassurance to women with endometriosis and recommend general cancer prevention measures [24].

Nonetheless, consideration of the possibility of malignancy should be taken in postmenopausal women with endometriosis, irrespective of symptoms. Two retrospective cohort studies in 2012 and 2013 revealed histologically confirmed ovarian, endometrial, or cervical malignancies in 35% and 14% of postmenopausal patients with endometriosis, respectively [27,28]. While there is insufficient data to accurately estimate the risk of malignancy in postmenopausal women with a history of endometriosis, if a pelvic mass is detected, the work-up and treatment should be performed according to national oncology guidelines [24,29,30,31].

Menopausal hormone therapy and endometriosis

While no studies have specifically examined the efficacy of MHT in women with a history of endometriosis, MHT is generally considered the most effective primary treatment for menopausal symptoms. Therefore, the presence of a history of endometriosis should not deter the use of hormone therapy [2]. The primary concerns for clinicians prescribing MHT in such patients are the potential recurrence of endometriosis lesions and their possible malignant transformation.

The recurrence of endometriosis after menopause is believed to increase, particularly in cases where surgical menopause has occurred due to treatment of endometriosis lesions, and may be associated with cyclic estrogen-progesterone therapy or persistent macroscopic implants following surgery [2]. The malignant transformation of endometriosis lesions related to hormone therapy is very rare. A report by Gemmell et al. [2] noted that among 25 cases, endometrioid adenocarcinoma was found in 18 patients and adenosarcoma in 2, with 19 of these cases having received unopposed estrogen therapy. Furthermore, Giannella et al. [32] reported a higher occurrence of malignant transformation in patients with a history of endometriosis, particularly those who had undergone major definitive surgeries like hysterectomy before menopause or had longterm estrogen-only therapy. Based on these findings, continuous combined estrogen-progesterone therapy is recommended over estrogen-only therapy for women with a history of endometriosis, particularly for those who experienced surgical menopause before the typical age of natural menopause. It is advised to continue combined estrogen-progestogen therapy up to the age of natural menopause.

Regarding tibolone, Fedele et al. [33] reported the comparison of tibolone with transdermal estrogen plus cycling medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). After 12 months, they concluded that tibolone might be safer. The recurrence of pain was 4 out of 10 patients in the transdermal estrogen/MPA group and 1 out of 11 in the tibolone group. However, currently, based on a Danish study that found an increase in endometrial cancer cases among general postmenopausal women taking tibolone with an unknown history of the endometriosis, tibolone is not recommended as a first-line medication in the latest European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology guideline on endometriosis [24,34].

Management

In postmenopausal women, if a mass suggestive of endometriosis is detected, histological confirmation through surgery is necessary [24]. When a pelvic mass is identified via ultrasound and exhibits characteristics suspicious of endometriosis, the approach should follow general guidelines for abdominal masses in postmenopausal women rather than the various diagnostic approaches applied in women of reproductive age. If symptoms such as pelvic pain are present, surgical treatment is typically considered first. If surgery is not feasible, treatment with an aromatase inhibitor may be considered as a pharmacological option [24].

Similarly, in premenopausal women, the reproductive and hormonal benefits of avoiding surgery or opting for conservative procedures gradually diminish. As in postmenopausal women, surgical treatment may be considered as a primary option for managing endometriosis in premenopausal women, even though the risk of malignancy remains rare [35,36].

UTERINE FIBROIDS

Epidemiology

Uterine fibroids are known to be one of the most common benign gynecological conditions, affecting up to 80% of reproductive-age women and causing symptoms in up to 30% of them [37,38]. The growth of fibroids is influenced by estrogen. Typically, they enlarge during reproductive years, are barely observed before menarche, and generally tend to shrink following menopause [39,40]. Although in premenopausal women, there is a wide variation in the growth of individual fibroids. Previous reports indicate that during a six-month follow-up period, fibroid sizes varied significantly, with reductions up to 89% and increases up to 138%, while generally showing an average growth rate of about 1.2 cm over 2.5 years. It is generally believed that symptoms associated with fibroids diminish after menopause, and although not all fibroids decrease in size, most are thought to reduce.

Menopausal hormone therapy and uterine fibroids

In postmenopausal women with uterine fibroids, a key area of interest is the impact of MHT on the size of fibroids and the new onset of symptoms associated with fibroids. Due to the conflicting data available, drawing definitive conclusions about the effect of hormone therapy on fibroid size remains challenging [41]. Furthermore, most of the research in this area was conducted in the late 90s with limited sample sizes and lacked thorough statistical analysis. The outcomes from hormone replacement therapy studies are mixed; certain estrogen and progestin combinations seem to considerably impact fibroid growth and the occurrence of new myomas during menopause. However, many studies showed no significant change in fibroid size, although there was a tendency towards growth. Significantly, the studies reporting major increases in fibroid size frequently used different types of progestins, especially MPA in various dosages, underscoring the substantial role of progesterone in influencing fibroid growth [42].

Five studies specifically examined tibolone, suggesting it does not significantly affect myoma growth compared to placebo or estrogen-progestin therapy, and it tends to be associated with fewer incidents of irregular spotting [43,44,45,46,47]. Efforts to find potential indicators of fibroid growth during MHT have included measuring the uterine artery pulsatility index, which might predict fibroid growth risks, though its effectiveness remains controversial [46,48]. Regarding selective estrogen receptor modulators, raloxifene has demonstrated a suppressive effect on fibromatous tissue in both animal and human studies, yet only two studies have explored its impact on leiomyomas, and both were conducted over a short duration [49,50].

The location of fibroids could be an important factor for the occurrence of new symptoms during MHT, particularly in cases of submucosal myomas which may be associated with bleeding during hormone treatment. It is necessary to verify if bleeding persists after discontinuation of MHT, and if bleeding does persist, further evaluation is warranted.

While there is concern about fibroid growth and the onset of new symptoms due to MHT, significant increases in fibroid size and the risk of malignancy are considered very rare with the standard dosages of MHT used in postmenopausal women [51]. Despite the low level of concern, regular pelvic examinations and transvaginal ultrasounds remain necessary. If significant size increases and persistent bleeding are confirmed, consideration should be given to the possibility of uterine malignancy.

ADENOMYOSIS

Epidemiology

The prevalence of adenomyosis varies depending on the diagnostic method used. Regarding the radiologic diagnosis of adenomyosis, the prevalence can change based on the number of characteristic ultrasound features observed when diagnosing the condition. According to research by Meredith et al. [52], the probability of adenomyosis in a woman with heavy bleeding and positive ultrasound features was 68.1%, compared with a 65.1% probability in a woman with positive ultrasound features undergoing a hysterectomy for any symptom. In a study involving 1,334 patients who underwent hysterectomy, histological examination confirmed adenomyosis in 332 patients (24.9%), and among 544 postmenopausal women, adenomyosis was found in 132 (24.3%) [53].

The California Teacher Study highlighted that the odds ratio (OR) for adenomyosis was significantly higher in premenopausal and perimenopausal women compared to postmenopausal women who were not receiving hormone therapy, with ORs of 4.72 (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.22 to 6.91) and 3.40 (95% CI, 2.10 to 5.51), respectively [54]. In postmenopausal women who received hormone therapy, the OR varied between 2.09 and 4.93 depending on the type of hormone treatment received. Notably, while obesity increased the OR in premenopausal women, it did not significantly increase the OR in overweight or obese postmenopausal women.

Menopausal hormone therapy and adenomyosis

Adenomyosis generally does not cause symptoms or increase in size after menopause. One concern associated with hormone therapy is the potential for malignant transformation, although only a limited number of case reports have been documented on this matter. According to a report by Yuan and Zhang [7], to date, there have been 50 cases reported. It has been challenging to identify specific symptoms that could predict malignant transformation, and it is believed that the transition from endometrial epithelium to monolayer tumor cells occurs before malignancy develops, though the specific molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

Based on the reported cases, clear risk factors for malignant transformation have not been definitively identified. However, studies suggest that the risk may be higher in elderly or postmenopausal patients who are taking MHT or tamoxifen, particularly if they also have a history of uterine leiomyoma or benign endometrial hyperplasia [55,56].

CONCLUSION

The considerations for benign gynecologic diseases in postmenopausal women have been summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1. Women experiencing hyperandrogenism after menopause can be diagnosed with PCOS, and it is necessary to differentiate it from hyperthecosis and androgen-secreting tumors. Postmenopausal women with a history of PCOS do not appear to have an increased cardiometabolic risk compared to those without a history of PCOS. Endometriosis can persist or recur after menopause, with potential malignancy concerns. Surgical confirmation and careful monitoring are essential for suspected cases. Uterine fibroids and adenomyosis usually shrink post-menopause. However, with rare risks becoming symptomatic or undergoing malignant transformation, regular monitoring and individualized management are crucial in postmenopausal women.

Table 1. Summary of special consideration for benign gynecological diseases in postmenopausal women.

| Disease | Condition | Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| PCOS | Diagnostic challenge | Past history of PCOS or PCOS stigma and hyperandrogenism (serum total testosterone < 150 ng/dL) |

| Cardiometabolic risk | Decreased serum HDL-C*/DM, HTN risk; not increase of prevalence** | |

| Endometrial cancer risk | No case reported in 32 PCOS patients after 21 years follow-up study | |

| Management | Weight management: essential for cardiometabolic risk reduction in obese patients | |

| Endometriosis | Malignant transformation | Possible, especially after history of endometriosis, estrogen-only therapy for relatively long time |

| MHT regimen | Combined MHT, avoiding estrogen-only regimens | |

| Management | According to national oncology guidelines | |

| Uterine fibroids | Size change | Most, but not all, shrinkage of leiomyoma |

| Symptoms | Bleeding, possible with MHT especially submucous type | |

| Effect of MHT | Conflicting data regarding size of myoma after MHT, but commonly not stimulate to grow | |

| Adenomyosis | Prevalence | Increase in women with hormone therapy |

| Malignant transformation | Low incidence; unclear risk factors (possibly - elderly, MHT and tamoxifen user) |

PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome, HDL-C: high density lipoprotein-cholesterol, DM: diabetes mellitus, HTN: hypertension, MHT: menopausal hormone therapy.

*Compared with controls who were similar in terms of body mass index;

**Compared postmenopausal women who were similarly aged controls

Fig. 1. Illustrated summary of benign gynecological conditions in postmenopausal women. PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome, HDL-C: high density lipoprotein-cholesterol, DM: diabetes mellitus, HTN: hypertension, MHT: menopausal hormone therapy.

The transition to menopause significantly alters the management strategies for various benign gynecological diseases. While some symptoms may abate, the long-term management of these conditions must consider the potential for new symptoms and risks, underscoring the need for personalized treatment plans and continuous research.

Footnotes

FUNDING: This work was supported by clinical research grant from Pusan National University Hospital in 2024.

CONFILCT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Hoeger KM, Dokras A, Piltonen T. Update on PCOS: consequences, challenges, and guiding treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:e1071–e1083. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gemmell LC, Webster KE, Kirtley S, Vincent K, Zondervan KT, Becker CM. The management of menopause in women with a history of endometriosis: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23:481–500. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Missmer SA, Tu FF, Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Soliman AM, Chiuve S, et al. Impact of endometriosis on life-course potential: a narrative review. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:9–25. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S261139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourdon M, Santulli P, Marcellin L, Maignien C, Maitrot-Mantelet L, Bordonne C, et al. Adenomyosis: an update regarding its diagnosis and clinical features. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:102228. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallach EE, Vlahos NF. Uterine myomas: an overview of development, clinical features, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:393–406. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000136079.62513.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ulin M, Ali M, Chaudhry ZT, Al-Hendy A, Yang Q. Uterine fibroids in menopause and perimenopause. Menopause. 2020;27:238–242. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan H, Zhang S. Malignant transformation of adenomyosis: literature review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299:47–53. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-4991-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helvaci N, Yildiz BO. Polycystic ovary syndrome and aging: health implications after menopause. Maturitas. 2020;139:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmina E, Campagna AM, Lobo RA. A 20-year follow-up of young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:263–269. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823f7135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teede HJ, Tay CT, Laven JJE, Dokras A, Moran LJ, Piltonen TT, et al. Recommendations from the 2023 international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:2447–2469. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forslund M, Schmidt J, Brännström M, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Dahlgren E. Reproductive hormones and anthropometry: a follow-up of PCOS and controls from perimenopause to older than 80 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:421–430. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markopoulos MC, Rizos D, Valsamakis G, Deligeoroglou E, Grigoriou O, Chrousos GP, et al. Hyperandrogenism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome persists after menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:623–631. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinola P, Piltonen TT, Puurunen J, Vanky E, Sundström-Poromaa I, Stener-Victorin E, et al. Androgen profile through life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a Nordic multicenter collaboration study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:3400–3407. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt J, Brännström M, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Dahlgren E. Reproductive hormone levels and anthropometry in postmenopausal women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a 21-year follow-up study of women diagnosed with PCOS around 50 years ago and their age-matched controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2178–2185. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirschberg AL. Approach to investigation of hyperandrogenism in a postmenopausal woman. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:1243–1253. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoldemir T. Postmenopausal hyperandrogenism. Climacteric. 2022;25:109–117. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2021.1915273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millán-de-Meer M, Luque-Ramírez M, Nattero-Chávez L, Escobar-Morreale HF. PCOS during the menopausal transition and after menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2023;29:741–772. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmad015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahlgren E, Johansson S, Lindstedt G, Knutsson F, Odén A, Janson PO, et al. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome wedge resected in 1956 to 1965: a long-term follow-up focusing on natural history and circulating hormones. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:505–513. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54892-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin O, Zacur HA, Flaws JA, Christianson MS. Association between polycystic ovary syndrome and hot flash presentation during the midlife period. Menopause. 2018;25:691–696. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haas D, Chvatal R, Reichert B, Renner S, Shebl O, Binder H, et al. Endometriosis: a premenopausal disease? Age pattern in 42,079 patients with endometriosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286:667–670. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2361-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henriksen E. Endometriosis. Am J Surg. 1955;90:331–337. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(55)90765-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikkanen V, Punnonen R. External endometriosis in 801 operated patients. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1984;63:699–701. doi: 10.3109/00016348409154666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ranney B. Endometriosis. 3. Complete operations. Reasons, sequelae, treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;109:1137–1144. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(71)90653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, Horne A, Jansen F, Kiesel L, et al. ESHRE Endometriosis Guideline Group. ESHRE guideline: endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open. 2022;2022:hoac009. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoac009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inceboz U. Endometriosis after menopause. Womens Health (Lond) 2015;11:711–715. doi: 10.2217/whe.15.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kvaskoff M, Mahamat-Saleh Y, Farland LV, Shigesi N, Terry KL, Harris HR, et al. Endometriosis and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27:393–420. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmaa045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morotti M, Remorgida V, Venturini PL, Ferrero S. Endometriosis in menopause: a single institution experience. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286:1571–1575. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun PR, Leng JH, Jia SZ, Lang JH. Postmenopausal endometriosis: a retrospective analysis of 69 patients during a 20-year period. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:4588–4589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michelle S, Paula JAH. In: Berek & Novak’s gynecology. 16th ed. Berek JS, editor. Wolters Kluwer; 2020. Adult gynecology: reproductive years; p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- 30.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology Practice bulletin no. 174: evaluation and management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e210–e226. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (RCOG)’s green-top guideline no. 34: the management of ovarian cysts in postmenopausal women. RCOG; 2016. [cited 2024 Sep 17]. Available from: https://icl-ref-dryad.maxarchiveservices.co.uk/uploads/r/null/7/1/2/7124cb55e6d1865c6baca004aa2435ef2ec06249937b344838cb4aacba3c4ca8/32a8973e-c664-4173-b235-f407a51b803e-_C__Royal_College_of_Obstetricians_and_Gynaecologists_Green_Top_Guideline_number_34_for_the_management_of_Ovarian_cysts_in_Postmenopausal_women.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giannella L, Marconi C, Di Giuseppe J, Delli Carpini G, Fichera M, Grelloni C, et al. Malignant transformation of postmenopausal endometriosis: a systematic review of the literature. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:4026. doi: 10.3390/cancers13164026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fedele L, Bianchi S, Raffaelli R, Zanconato G. Comparison of transdermal estradiol and tibolone for the treatment of oophorectomized women with deep residual endometriosis. Maturitas. 1999;32:189–193. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Løkkegaard ECL, Mørch LS. Tibolone and risk of gynecological hormone sensitive cancer. Int J Cancer. 2018;142:2435–2440. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomsen LH, Schnack TH, Buchardi K, Hummelshoj L, Missmer SA, Forman A, et al. Risk factors of epithelial ovarian carcinomas among women with endometriosis: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:761–778. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vercellini P, Viganò P, Buggio L, Makieva S, Scarfone G, Cribiù FM, et al. Perimenopausal management of ovarian endometriosis and associated cancer risk: when is medical or surgical treatment indicated. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:151–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moravek MB, Bulun SE. Endocrinology of uterine fibroids: steroid hormones, stem cells, and genetic contribution. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27:276–283. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seracchioli R, Manuzzi L, Vianello F, Gualerzi B, Savelli L, Paradisi R, et al. Obstetric and delivery outcome of pregnancies achieved after laparoscopic myomectomy. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Segars JH, Parrott EC, Nagel JD, Guo XC, Gao X, Birnbaum LS, et al. Proceedings from the Third National Institutes of Health International Congress on Advances in Uterine Leiomyoma Research: comprehensive review, conference summary and future recommendations. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:309–333. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sener AB, Seçkin NC, Ozmen S, Gökmen O, Doğu N, Ekici E. The effects of hormone replacement therapy on uterine fibroids in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:354–357. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moro E, Degli Esposti E, Borghese G, Manzara F, Zanello M, Raimondo D, et al. The impact of hormonal replacement treatment in postmenopausal women with uterine fibroids: a state-of-the-art review of the literature. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019;55:549. doi: 10.3390/medicina55090549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palomba S, Sena T, Morelli M, Noia R, Zullo F, Mastrantonio P. Effect of different doses of progestin on uterine leiomyomas in postmenopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;102:199–201. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(01)00588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Aloysio D, Altieri P, Penacchioni P, Salgarello M, Ventura V. Bleeding patterns in recent postmenopausal outpatients with uterine myomas: comparison between two regimens of HRT. Maturitas. 1998;29:261–264. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fedele L, Bianchi S, Raffaelli R, Zanconato G. A randomized study of the effects of tibolone and transdermal estrogen replacement therapy in postmenopausal women with uterine myomas. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;88:91–94. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(99)00115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gregoriou O, Konidaris S, Botsis D, Papadias C, Makrakis E, Creatsas G. Long term effects of Tibolone on postmenopausal women with uterine myomas. Maturitas. 2001;40:95–99. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(01)00234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gregoriou O, Vitoratos N, Papadias C, Konidaris S, Costomenos D, Chryssikopoulos A. Effect of tibolone on postmenopausal women with myomas. Maturitas. 1997;27:187–191. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(97)00036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simsek T, Karakus C, Trak B. Impact of different hormone replacement therapy regimens on the size of myoma uteri in postmenopausal period: tibolone versus transdermal hormonal replacement system. Maturitas. 2002;42:243–246. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(02)00081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colacurci N, De Franciscis P, Cobellis L, Nazzaro G, De Placido G. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on postmenopausal uterine myoma. Maturitas. 2000;35:167–173. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palomba S, Orio F, Jr, Russo T, Falbo A, Tolino A, Lombardi G, et al. Antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects of raloxifene on uterine leiomyomas in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palomba S, Sammartino A, Di Carlo C, Affinito P, Zullo F, Nappi C. Effects of raloxifene treatment on uterine leiomyomas in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:38–43. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01849-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hugh ST, Lubna P, Emre S. In: Speroff’s clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 9th ed. Taylor HS, Pal L, Sell E, editors. Wolthers Kluwer; 2019. Menopause transition and menopause hormone therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meredith SM, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal sonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:107.e1–107.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vercellini P, Parazzini F, Oldani S, Panazza S, Bramante T, Crosignani PG. Adenomyosis at hysterectomy: a study on frequency distribution and patient characteristics. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:1160–1162. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Templeman C, Marshall SF, Ursin G, Horn-Ross PL, Clarke CA, Allen M, et al. Adenomyosis and endometriosis in the California Teachers Study. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ismiil ND, Rasty G, Ghorab Z, Nofech-Mozes S, Bernardini M, Thomas G, et al. Adenomyosis is associated with myometrial invasion by FIGO 1 endometrial adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2007;26:278–283. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000235064.93182.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gizzo S, Patrelli TS, Dall’asta A, DI Gangi S, Giordano G, Migliavacca C, et al. Coexistence of adenomyosis and endometrioid endometrial cancer: role in surgical guidance and prognosis estimation. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:1213–1219. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]