Abstract

Background

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an immune-mediated hepatic disease associated with intense complications. AIH is more common in females and needs effective drugs to treat. Guizhi Fuling Wan (GZFLW) is a traditional Chinese herbal formula for treating various gynecologic diseases. In this study, we aim to extend the new use of GZFLW for AIH.

Methods

The tandem MS-based analysis was used to identify secondary metabolites in GZFLW. Therapeutic effects of GZFLW were tested in a concanavalin A (Con A)-induced AIH model in mice. Ethnopharmacological mechanisms underlying the antiapoptotic, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory protective effects were determined.

Results

Oral administration of GZFLW attenuates AIH in a Con A-induced hepatotoxic model in vivo. The tandem MS-based analysis identified 15 secondary metabolites in GZFLW. The Con A-induced AIH syndromes, including hepatic apoptosis, inflammation, reactive oxygen species accumulation, function failure, and mortality, were significantly alleviated by GZFLW in mice. Mechanistically, GZFLW restrained the caspase-dependent apoptosis, restored the antioxidant system, and decreased pro-inflammatory cytokine production in the livers of Con A-treated mice. Besides, GZFLW repressed the Con A-induced hepatic infiltration of inflammatory cells, splenic T cell activation, and splenomegaly in mice.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate the applicable potential of GZFLW in treating AIH. It prompts further investigation of GZFLW as a treatment option for AIH and possibly other hepatic diseases.

Keywords: Antioxidant system, Apoptosis, Autoimmune hepatitis, Guizhi Fulin Wan, Inflammation

Highlights

-

•

Guizhi Fulin Wan (GZFLW) attenuated Con A-induced autoimmune hepatitis in mice.

-

•

GZFLW inhibited liver cell apoptosis, oxidative stress, and pro-inflammatory cytokines in Con A-treated mice.

-

•

GZFLW reduced hepatic inflammatory cells, splenic T cell activation, and splenomegaly in Con A-induced mice.

-

•

GZFLW has the potential to be developed as a treatment for autoimmune hepatitis.

1. Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an idiopathic immune-mediated disease that causes liver damage and functional failure, particularly in perimenopausal females. It leads to prolonged hepatic injury, characterized by significant elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and autoantibodies. The classic histopathological features of AIH include interface hepatitis with lymphocytic/lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in portal tracts extending into the lobule, hepatocellular apoptosis/necrosis, and architectural disruption of hepatic lobules. Untreated AIH may result in the development of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma and may even warrant liver transplantation [[1], [2], [3]].

AIH can be subtyped by the presence of different autoantibodies, such as either AIH-1 or AIH-2. In East Asia, the predominant type of AIH is AIH-1, while AIH-2 is relatively uncommon. However, in South Asia, the prevalence of AIH-2 is comparable to that in Europe and the USA. The global prevalence of AIH is on the rise, with 12.99, 22.80, and 19.44 per 100,000 individuals in Asia, the US, and Europe, respectively [2,[4], [5], [6]]. The increasing incidence rates may be attributed to heightened awareness of disease concepts; consequently, early detection and treatment of patients with AIH could ameliorate the current situation.

Immunosuppressive therapy with steroids and azathioprine is the standard therapeutic approach for AIH. However, in cases where the liver injury is extensive or standard therapy fails, liver transplantation may be necessary. Prompt diagnosis and timely treatment can improve the outcome of AIH and prevent the development of liver cirrhosis or failure. However, prolonged use of immunosuppressive drugs often leads to adverse effects and increases susceptibility to infection, leading to the exploration of alternative therapeutic options [7,8]. Various natural products or traditional herbal medicines have been documented as an alternative remedy in treating AIH [[9], [10], [11]].

Concanavalin A (Con A), a plant lectin from Canavalia ensiformis (jack bean), can activate T cells by binding to their receptors. It can trigger a cascade of immune responses, rendering it useful for studying autoimmune diseases in mammals. The Con A-induced liver injury mouse model is a well-established model for AIH. Con A-mediated immune responses are not solely dependent on T cells; natural killer T cells, neutrophils, and intrahepatic macrophages (known as Kupffer cells) also play critical roles in the pathogenesis of AIH [2,12,13]. Con A exacerbates the release of a variety of proinflammatory cytokines, including interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukins (ILs), or granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), which maintain immunostimulatory processes and liver damage [2,9,12]. The Con A-induced inflammation triggers oxidative stress that contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of AIH. The inflammatory oxidative stress is primarily caused by the increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or lipid peroxidation as well as inactivation of antioxidant systems, such as a decrease in glutathione (GSH) levels or reduced activity of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). These events often coincide with severe liver inflammation and extensive hepatocyte apoptosis/necrosis [[12], [13], [14]].

Guizhi Fuling Wan (GZFLW), also known as Keishibukuryogan, is composed of five herbs in equal weight ratios, including Chinese cinnamon twig (Gui-zhi: ramulus of Cinnamomum cassia Blume), poria sclerotium (Fu-lin: Poria cocos Wolf), peach kernel (Tao-ren: Prunus persica Batsch), peony root (Bai-Shao: Peonia lactiflora Pall), and moutan bark (Mu-dan-pi: Peonia suffruticosa Andrews). GZFLW is a traditional herbal formula that was used to treat uterine leiomyoma and related bleeding during pregnancy. It is commonly prescribed in Taiwan for the treatment of other gynecologic diseases, such as emmeniopathy, dysmenorrhea, endometriosis, polycystic ovary disease, and infertility [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]]. GZFLW exhibits a myriad of bioactivities, such as vasodilation, antiplatelet aggregation, antifibrotic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic properties, or lipid metabolism control [21,22]. Nonetheless, only a few studies address the hepatoprotective effects of GZFLW. Clinical use of GZFLW was reported to attenuate liver injury and inflammation in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and administration of GZFLW reduced acute liver injury in d-galactosamine or carbon tetrachloride-treated rats [23,24]. Thus, we hypothesized that GZFLW can treat AIH, a female-dominant, immune-mediated inflammatory liver disease.

The present study demonstrates that GZFLW significantly attenuates the AIH symptoms and mortality in Con A-induced mice. GZFLW protected Con A-induced AIH by inhibiting hepatic apoptosis, oxidative stress, pro-inflammatory cytokine, and splenic T cell activation. This is the first study to reveal the potential use of the traditional herbal medicine, GZFLW, as a treatment option for AIH by conferring antioxidant and immunomodulatory protection.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of GZFLW

GZFLW was composed of five herbs in equal weight ratios as follows: Gui-zhi (Batch No. CQT201709), Fu-lin (Batch No. 1803), and Tao-ren (Batch No. 1802) were purchased from Chung Ching Tarng Chinese Medicine Co., LTD (Taipei, Taiwan); Bai-shao (Batch No. M76051) and Mu-dan-pi (Batch No. 017/1006-B50) were obtained from Sun Ten Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (New Taipei City, Taiwan) and Healthy Beautiful Biotech Co., LTD (Taichung, Taiwan), respectively. The five herbs were soaked in 95% ethanol (0.2 g/mL) for 1 week and then heated at 100 °C for 1 h. The dried GZFLW powders (19.6 g; yield 9.8%) were obtained using a rotary evaporator (BÜCHI Rotavapor R-200, Büchi Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland) at 35 °C.

2.2. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

A Shimazu Nexera X2 UPLC system (Shimazu, Kyoto, Japan) was utilized to profile GZFLW. Liquid chromatography was carried out using a YMC-Triart PFP UPLC C18 (12 nm, 1.9 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm) column (YMC, Tokyo, Japan). The mobile phase was prepared by mixing MeCN (A) and water (W, containing 0.1% formic acid); the gradient sequence was executed as follows: 0–10 min, 7–10% A; 10–20 min, 10–15% A; 20–40 min, 15–25% A; 40–50 min, 25–40% A; 50–65 min, 40–50% A; 65–75 min, 50–85% A; 75–85 min, 85–100% A; 85–90 min, 100% A. The flow rate was fixed at 0.4 mL/min, and the column temperature was maintained at 35 °C. To prepare the sample, 2 mg GZFLW was dissolved in 1 mL of methanol and filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filter. The sample injection was executed automatically with 1 μL volume per injection.

The MS1 full scan and MS2 products ion scan experiments (in the positive or negative mode) were performed utilizing Shimazu LCMS-8045 (Shimazu, Kyoto, Japan) and Agilent 6500 Series Q-TOF LC/MS System (Agilent, C.A., U.S.A.) mass spectrometry, respectively. The precursor ion settings of the corresponding profiling peaks were concluded according to the complete scan experiment (50–1000 atomic mass units [amu]). The dwell time was set at 100 ms (msec), and the collision energy (CE) was fixated at 40 electron Volts (eV). All the acquired MS data were processed by LCMS LabSolutions software (Version 5.93, Shimazu, Kyoto, Japan) and Agilent Mass Hunter software version B.09.00 (B9044.0, Agilent, C.A., U.S.A.).

2.3. Experimental animals

All animal experiments were conducted according to institutional guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Chang Gung University, Taiwan (Approval No.: CGU110-141). Female C57BL/7 mice (8–9 weeks old) were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center (NARLabs, Taiwan) and housed in a temperature-controlled environment (22 ± 2 °C) with 60 ± 10% humidity with adequate and unlimited water and diet under a 12-12 h light-dark cycle before and during the experiments. The mice were randomly assigned into 5 groups (n = 6 in each group): (1) vehicle (10% DMSO in glyceryl trioctanoate); (2) vehicle + Con A; (3) GZFLW (25 mg/kg) + Con A; (4) GZFLW (50 mg/kg) + Con A; (5) prednisone (5 mg/kg) + Con A.

2.4. Con A-induced AIH model

Mice received oral administration of GZFLW or prednisone once a day for 7 consecutive days, and then AIH was induced by intravenous injection of Con A (20 mg/kg) under general anesthesia. After 12 h, the livers were fixed in 10% formalin for histological staining [Supplementary Fig. 1]. Pathophysiological liver lesions were scored for inflammation using the following criteria: 0, no inflammation or necrosis; 1, confluent or intralobular inflammation; 2, slight piecemeal necrosis or focal necrosis; 3, medium confluent inflammation and piecemeal necrosis or severe focal necrosis; 4, serious confluent inflammation and piecemeal necrosis or bridging necrosis [25].

2.5. Histological staining

Liver tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, decalcified in 15% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and embedded in paraffin. Liver tissues were serially cut into sections 5 μm thick and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The Nrf2 expression in liver tissues was determined immunohistochemically using the Rabbit-specific HRP/DAB Detection IHC Kit (Cat# ab64261; Abcam, Boston, MA, USA) and the anti-NRF2 Rabbit pAb (Cat# A0674; ABclonal, Woburn, MA, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The Nrf2 area were analyzed using the ImageJ software (version 1.54f, National Institutes of Health, USA).

2.6. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

The TUNEL assay was conducted using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, liver sections were processed by deparaffinization and rehydration, then incubating with TUNEL reaction mix for 1 h at 25 °C. The TUNEL-positive cells were determined using fluorescence microscopy and counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) for nuclear staining.

2.7. Flow cytometry

Spleen cells were isolated by mechanical disruption and passed through a 30 μm steel mesh. Cells were incubated with PE anti-human CD4 Recombinant Antibody (Cat# 302403) or PE anti-human CD8 Recombinant Antibody (Cat# 303803) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA). They were subsequently permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus Kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, US) by the manufacturer's instructions. After that, cells were stained with FITC anti-human IFN-γ Antibody (Cat# 502506; Biolegend). The fluorescence intensity of CD4, CD8, or IFN-γ was measured using a BD Accuri Cytometer (BD Biosciences, CA, USA).

2.8. Western blotting

Liver tissues were collected and homogenized in 100 μL RIPA buffer (Abcam, Boston, MA, USA) for 30 min and quenched by sample buffer at 100 °C for 5 min. SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) and immunoblotting were conducted using primary and secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies. ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to determine the expression of indicated proteins. Antibodies used in this study were cleaved-caspase-3 (Cat# 9661; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), cleaved-caspase-8 (Cat# 8592; Cell Signaling), cleaved-caspase-9 (Cat# 9501; Cell Signaling), Bax (Cat# 633602; Biolegend), Bcl-xl (54H6) (Cat# 2764; Cell Signaling), Bcl-2 (Cat# 05–729; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and beta-actin (E4D9Z) (Cat# 58269; Cell Signaling).

2.9. Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA synthesis and mRNA levels were detected using the Reverse SYBR Select Master Mix kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China), followed by quantitative real-time PCR (Yeasen, Shanghai, China). Primers used for indicated mouse genes were as follows: IL-1β (5′-TCGTGCTGTCGGACCCATA-3′ and 5′-TTGTTGGTTGATATTCTGTCCATTG-3′); TNF-α (5′-GTGGTGGACGGGAAAGAAGA-3′ and 5′-CAACCACGTGACCACT-GAAGAA-3′); IFN-γ (5′-GCAACAGCAAGGCGAAAAAG-3′ and 5′-CTGG-ACCTGTGGGTTGTTGAC-3′); IL-2 (5′-CACATTCAAAGCCCTCTCCTACA-3′ and 5′-TCTTCGGAAACCTCTCTTGCA-3′); IL-17A (5′-CTCCAGAAGGCCCTC-AGACTAC-3′ and 5′-GAGTTCATGGTGCTGTCTTCC-3′); GAPDH (5′-CGTGT-TCCTACCCCCAATGT-3′ and 5′-TGTCATCATACTTGGCAGGTTTCT-3′).

2.10. Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity in the liver was determined by measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA; Cat# MBS741034), GSH (Cat# MBS700004), superoxide dismutase (SOD; Cat# MBS265351), or myeloperoxidase (MPO; Cat# MBS700747), which were purchased from MyBiosource (San Diego, CA, US). All assays were conducted according to the corresponding instructions provided by the manufacturer.

2.11. Nuclear Nrf2-binding activity

Nuclear lysates from livers were extracted using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, US); 10 μg nuclear lysates were used to detect Nrf2-binding activity by TransAM® Nrf2 ELISA kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, US), following the manufacturer's instructions.

2.12. Statistical analysis

This study used GraphPad Prism 10.0.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) as statistical software. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were conducted by unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA and post hoc analysis with Tukey's multiple comparison tests. The significance of the inflammation score of histopathology of the liver was analyzed by the Kruskal–Wallis test due to its ordinal scale nature. The significance of mouse survival time between groups was determined via Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of constituents from GZFLW

The chemical characterization and structures [Fig. 1] of the major constituents from GZFLW using LC-MS/MS led to the putative identification of 15 compounds [Table 1], including 7 monoterpene glycosides [oxypaeoniflorin (1), paeoniflorin (2), mudanpiosides E (3), benzoyloxypaeoniflorin (4), mudanpioside C (5), paeonol (6), benzoyl paeoniflorin (7)], 5 triterpenoids [dehydrotumulosic acid (9), tumulosic acid (10), polyporenic acid C (11), dehydropachymic acid (12), pachymic acid (13)], and 3 fatty acid derivatives [methyl 8-acetoxy-4Z-hexadecenoate (8), linoleic acid (14), and cis-octadecenoic acid (15)].

Fig. 1.

Identification of constituents from GZFLW. (A) The ESI-MS spectra (positive ion mode) of GZFLW. (B) The chemical structures of the identified components from GZFLW.

Table 1.

MSn data of GZFLW constituents.

| No. | tR (min) | Formula | Calculated exact mass (m/z) | Experimental mass (m/z) | ESI-MS/MS Fragment Ions | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.02 | C23H28O12 | 496.1580 | 496.1576 | a281, 177, 165, 137 | Oxypaeoniflorin |

| 2 | 10.00 | C23H28O11 | 480.1631 | 480.1633 | b161, 151, 133, 123, 121, 105 | Paeoniflorin |

| 3 | 12.70 | C24H30O13 | 526.1686 | 526.1681 | a167, 121 | Mudanpiosides E |

| 4 | 35.15 | C30H32O13 | 600.1843 | 600.1840 | a431, 429, 281, 239, 179, 177, 149, 137, 121 | Benzoyloxypaeoniflorin |

| 5 | 36.77 | C30H32O13 | 600.1843 | 600.1838 | a165, 137, 121 | Mudanpioside C |

| 6 | 37.91 | C9H10O3 | 166.0630 | 166.0627 | b103, 102 | Paeonol |

| 7 | 42.66 | C30H32O12 | 584.1894 | 584.1892 | b151, 133, 105 | Benzoyl paeoniflorin |

| 8 | 50.88 | C19H34O4 | 326.2457 | 326.2451 | a290, 237, 213, 183, 132 | Methyl 8-acetoxy-4Z-hexadecenoate |

| 9 | 59.01 | C31H48O4 | 484.3553 | 484.3552 | a437, 423, 421, 337 | Dehydrotumulosic acid |

| 10 | 59.69 | C31H50O4 | 486.3709 | 486.3707 | a437, 423, 337, 221 | Tumulosic acid |

| 11 | 62.14 | C31H46O4 | 482.3396 | 482.3396 | a437, 435, 421, 403, 388, 311 | Polyporenic acid C |

| 12 | 67.89 | C33H50O5 | 526.3658 | 526.3656 | a481, 479, 465, 463, 432, 355 | Dehydropachymic acid |

| 13 | 68.65 | C33H52O5 | 528.3815 | 528.3816 | a481, 467, 465, 221, 193 | Pachymic acid |

| 14 | 69.11 | C18H32O2 | 280.2402 | 280.2404 | b248, 133, 123, 121, 119, 109, 107, 105 | Linoleic acid |

| 15 | 71.32 | C18H34O2 | 282.2559 | 282.2559 | b121, 111, 109, 107 | cis-Octadecenoic acid |

(−)-ESI-MS/MS fragment ions.

(+)-ESI-MS/MS fragment ions.

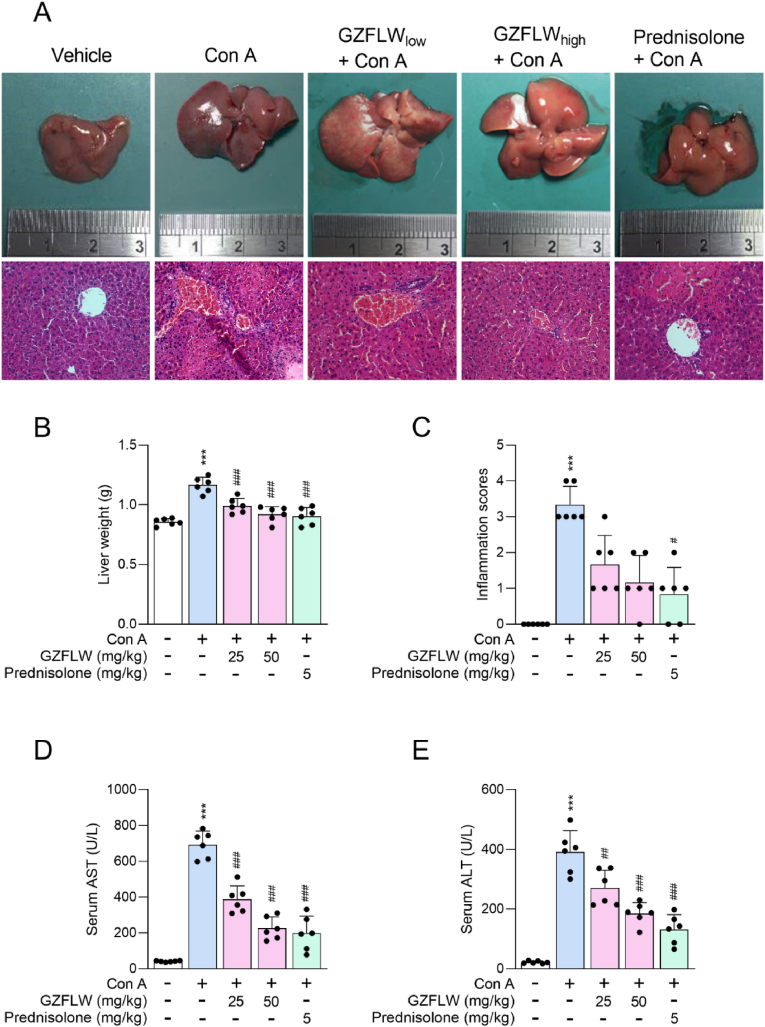

3.2. GZFLW impedes the con A-induced autoimmune hepatitis in mice

This study aimed to determine the applicable potential of GZFLW on AIH. The AIH architectures were evoked in the livers of mice after intravenous injection of Con A (20 mg/kg) for 12 h, including appearance congestion, portal inflammation, periportal necrosis (piecemeal necrosis), hepatocyte damage (ballooning degeneration [swelling], acidophilic change [shrinkage], lobular disarray, or vascular congestion), liver weight increase, and liver function failure (AST and ALT elevation). Pathophysiological liver lesions were also assigned an inflammation score based on the severity of inflammation and necrosis [25]. Significantly, oral administration of both 25 mg/kg (low) and 50 mg/kg (high) GZFLW or prednisone (5 mg/kg) ameliorated Con A-induced AIH [Fig. 2]. The Con A-induced mortality in mice was also impeded using GZFLW or prednisone pre-treatment [Fig. 3A]. Noticeably, the protective effects exhibited no statistical difference between 50 mg/kg GZFLW and prednisone, a standard immunosuppressive therapy in the treatment of AIH, suggesting that GZFLW provides a desirable opportunity for clinical remedy.

Fig. 2.

GZFLW attenuates the Con A-induced autoimmune hepatitis in mice. C57BL/7 mice (n = 6 in each group) were orally administered with the vehicle, GZFLW (25 [low] or 50 [high] mg/kg), or prednisone (5 mg/kg) over a period of 7 consecutive days and then AIH was induced by intravenous injection of Con A (20 mg/kg) for 12 h. (A) Light microscopy images and H&E-stained liver sections, (B) liver weight, and (C) inflammation score were determined. The levels of (D) alanine aminotransferase (AST) and (E) aspartate aminotransferase (ALT) from serum were monitored using an automated clinical chemistry analyzer. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared with the vehicle group; #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001 compared with the vehicle + Con A group.

Fig. 3.

GZFLW reduces the Con A-induced mortality and hepatotoxicity in mice. C57BL/7 mice (n = 6 in each group) were orally administered with the vehicle, GZFLW (25 or 50 mg/kg), or prednisone (5 mg/kg) over a period of 7 consecutive days followed by intravenous injection of Con A (20 mg/kg). (A) The survival rate was monitored for 48 h. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01 compared with the vehicle group; #p < 0.05 compared with the vehicle + Con A group. (B) After 12 h, hepatotoxicity of liver sections was determined by TUNEL assay. DAPI (blue) was used to visualize the cell nucleus.

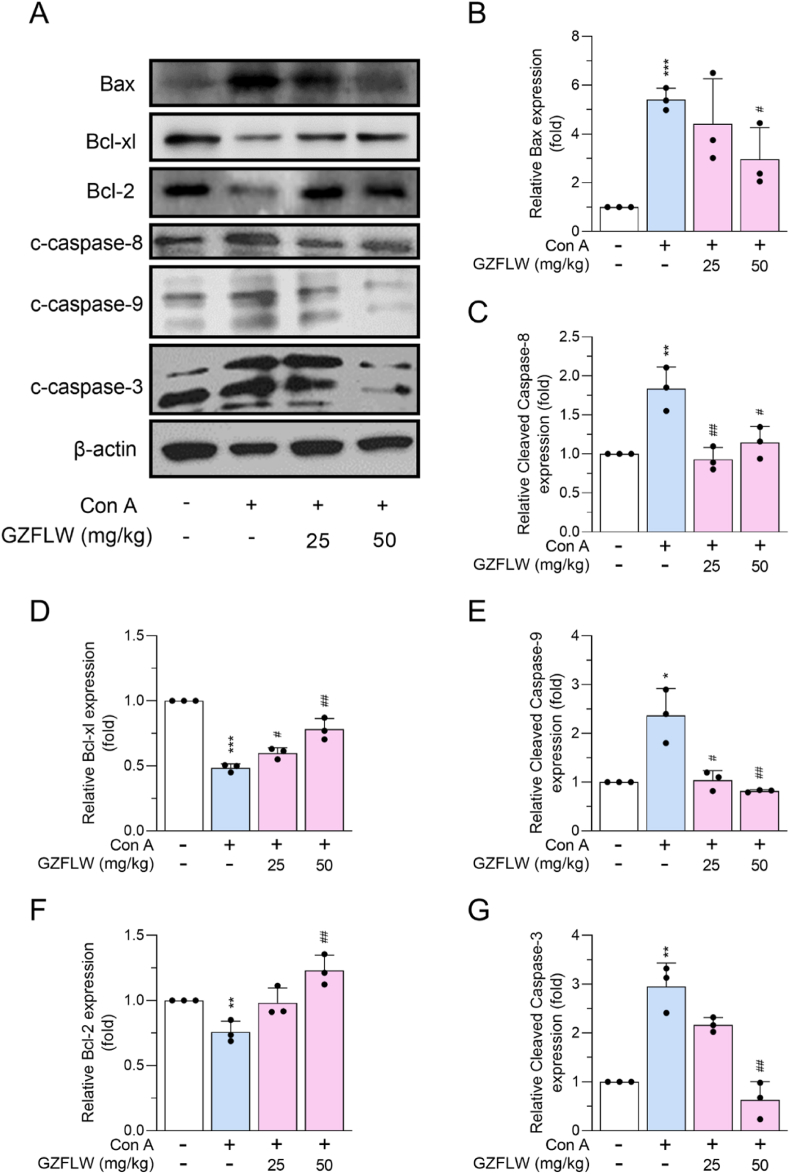

3.3. GZFLW attenuates the con A-induced hepatic apoptosis in mice

During Con A-induced AIH, it triggers an immune-mediated attack on liver cells, leading to hepatocellular apoptosis [12,13]. In the present study, TUNEL staining and expression of proapoptotic or antiapoptotic members were assayed to monitor the apoptotic features in the livers of Con A-induced mice. Con A challenge increased TUNEL-positive DNA fragmentation and expression of proapoptotic Bax, cleaved caspase-3, -8, and -9 in mouse liver; by contrast, expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-xl and Bcl-2 were decreased. The Con A-induced hepatic cell death in mice was curbed by 25 and 50 mg/kg GZFLW by abrogating the apoptotic death pathway [Fig. 3, Fig. 4].

Fig. 4.

GZFLW alleviates the Con A-induced apoptosis in the livers of mice. C57BL/7 mice (n = 6 in each group) were orally administered vehicle or GZFLW (25 or 50 mg/kg) over a period of 7 consecutive days, followed by intravenous injection of Con A (20 mg/kg) for 12 h. (A) Protein expression and (B–G) quantification of Bax, cleaved caspase-8, Bcl-xl, cleaved caspase-9, Bcl-2, cleaved caspase-3, and beta-actin in livers were evaluated using western blotting analysis. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared with the vehicle group; #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001 compared with the vehicle + Con A group.

3.4. GZFLW exhibits antioxidant activity to alleviate con A-induced hepatic oxidative stress in mice

Oxidative stress is an important pathogenic factor for Con A-induced liver injury [26,27], and the antioxidant activity of GZFLW has been described [28,29]. Therefore, we propose that GZFLW may exhibit antioxidant activity to alleviate Con A-induced oxidative stress. To address this hypothesis, the redox dynamics were examined in the livers of Con A-treated mice, including MDA levels (lipid peroxidation), GSH levels (vital antioxidants in cells), and SOD activities (free-radical scavengers). As the results show, Con A increased the MDA levels and decreased the GSH levels and SOD activities in mouse livers, which were alleviated by GZFLW pre-treatment [Fig. 5A–C]. It has been documented that activation of Nrf2, a master antioxidant transcription factor, can protect Con A-induced AIH [30,31]. Intravenous injection of Con A significantly repressed the nuclear Nrf2 binding activity and Nrf2 expression in mouse livers, suggesting that the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathways were also suppressed. Both 25 and 50 mg/kg GZFLW rescued the Nrf2 inhibition of binding activity and expression in mice [Fig. 5D and E]. Together, we suggest that the protective role of GZFLW on Con A-induced AIH may depend on its antioxidant activity in livers.

Fig. 5.

GZFLW inhibits the Con A-induced oxidative stress via antioxidant activation in the livers of mice. C57BL/7 mice (n = 6 in each group) were orally administered with vehicle, GZFLW (25 or 50 mg/kg), or prednisone (5 mg/kg) over a period of 7 consecutive days, followed by intravenous injection of Con A (20 mg/kg) for 12 h. (A) MDA levels, (B) GSH levels, (C) SOD activity, and (D) nuclear Nrf2-binding activity in the liver were determined. (E) The Nrf2 expressions were examined using histological staining and quantified as a percentage of area. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared with the vehicle group; #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001 compared with the vehicle + Con A group.

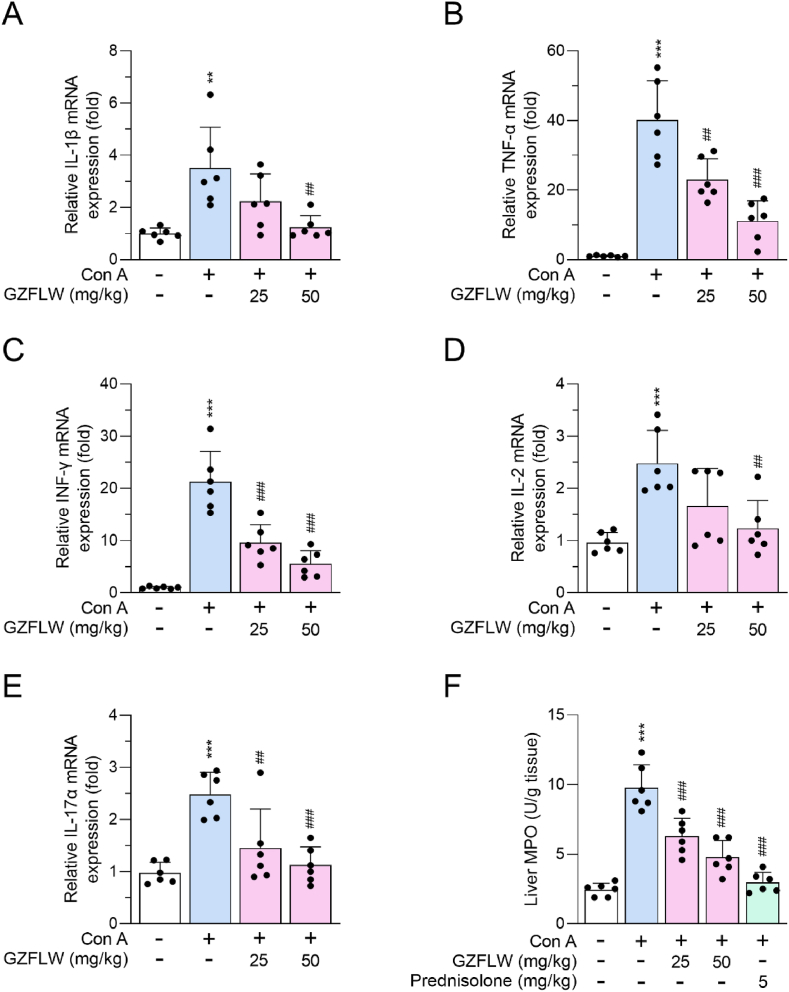

3.5. GZFLW curves the inflammatory responses in con A-induced mice

A variety of inflammatory responses is the canonical injury in the Con A-induced AIH, and AIH may be treated by targeting inflammatory responses [9,12]. Here, we found that the levels of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β, TNF-α, INF-γ, IL-2, and IL-17α, were upregulated in livers from Con A-induced mice that were alleviated by GZFLW (25 and 50 mg/kg) pre-treatment [Fig. 6A–E]. The increased MPO activity, expressed mainly in inflammatory neutrophils and monocytes, also served as an inflammatory indicator in Con A-induced AIH. Administration of GZFLW (25 and 50 mg/kg) or prednisone (5 mg/kg) significantly ameliorated Con A-activated MPO in the liver [Fig. 6F], suggesting that GZFLW may repress the infiltration and activation of inflammatory immune cells in the liver.

Fig. 6.

GZFLW decreases expression of Con A-induced cytokines in the livers of mice. C57BL/7 mice (n = 6 in each group) were orally administered with vehicle or GZFLW (25 or 50 mg/kg) over a period of 7 consecutive days, followed by intravenous injection of Con A (20 mg/kg) for 12 h. Levels of (A) IL-1β, (B) TNF-α, (C) IFN-γ, (D) IL-2, (E) IL-17α, and (F) MPO activity from hepatitis liver were determined. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared with the vehicle group; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001 compared with the vehicle + Con A group.

Furthermore, the splenomegaly (shape and weight) and activation of splenic T cells (CD4+INF-γ+ and CD8+INF-γ+) were observed in spleens from Con A-treated mice. Oral feeding of GZFLW (25 and 50 mg/kg) mitigated the Con A-induced splenic inflammation in mice [Fig. 7]. GZFLW may serve as a protective immunomodulator against Con A-induced AIH by targeting inflammatory responses. The protective effect of GZFLW against Con A-induced AIH in mice is represented in [Fig. 8].

Fig. 7.

GZFLW ameliorates the Con A-induced inflammation of splenomegaly in mice. C57BL/7 mice (n = 6 in each group) were orally administered with vehicle or GZFLW (25 or 50 mg/kg) over a period of 7 consecutive days, followed by intravenous injection of Con A (20 mg/kg) for 12 h. (A) Light microscopy images of the spleen. (B–E) T cell activation in the spleen was detected by flow cytometry, using PE-labeled anti-CD4, PE-labeled anti-CD8, or FITC-labeled IFN-γ antibodies. (F) Spleen weight was determined. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared with the vehicle group; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001 compared with the vehicle + Con A group.

Fig. 8.

Schematic model illustrates the protective effect of GZFLW against Con A-induced AIH in mice. Con A-induced AIH was demonstrated with T cell activation in the spleen, oxidative stress, inflammation cytokine release, and liver apoptosis (left two red boxes). Additionally, there was a decrease in antioxidant and anti-apoptosis activities (right green box), ultimately leading to the mortality of mice. Oral treatment with GZFLW significantly reversed these manifestations of AIH.

4. Discussion

AIH is an immune-inflammatory and life-threatening disease of the liver, possibly leading to functional failure, cirrhosis, and cancer [[1], [2], [3]]. Steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs remain the standard approach for treating AIH despite their long-term use, triggering adverse outcomes and harmful effects [32]. GZFLW has been used as a traditional herbal formula to treat gynecologic diseases. Emerging evidence suggests that GZFLW may be used to treat inflammatory diseases by its diverse bioactivities [21,22]. It has also been listed as a candidate treatment for liver injury [23,24]; however, the applicable potential of GZFLW on AIH is still unknown.

Our study demonstrated that GZFLW substantially impaired AIH-associated symptoms and severity in Con A-treated mice. Con A-induced AIH is a well-established CD4+ T helper cell activated model in vivo, whereby hepatocytic death, AST/ALT elevation, or inflammatory phenotype can be detected within 8–12 h after Con A injection [9,12,33]. GZFLW suppressed the Con A-induced apoptosis, oxidative stress, and proinflammatory cytokine production in livers or T cell activation in spleens from mice. Our findings provide mechanistic insight into the roles of GZFLW and its immunomodulatory protection in the development of AIH.

Fifteen major constituents from GZFLW were determined by LC-MS/MS [Fig. 1 and Table 1]. Among these, the monoterpene glycosides (1–7) are known to be representative metabolites of Paeonia plants [34]. The triterpenoids (9–13) were found to be the major compounds derived from Poria cocos [35]. Additionally, seed-based herbs such as P. persica were often characterized by fatty acid derivatives (8, 14–15) [36]. The pharmacological profiles of monoterpene glycosides, triterpenoids, or fatty acid derivatives against oxidative inflammatory responses have been widely described [[37], [38], [39], [40], [41]], suggesting that these compounds from GZFLW may serve as the characteristic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory components in the treatment of AIH.

Approximately 10–20% of patients with AIH exhibit an inadequate response or intolerable adverse effects to standard treatment, leading to the need for alternative treatment options [7,42]. A growing body of studies reveals that traditional herbal medicines can be used to protect against liver injury in Con A-induced mice or patients with AIH [10,11,43,44]. The possibility of GZFLW in protecting against liver injury is also considered [23,24]. In this study, we demonstrated that Con A-induced AIH warning signs, including congestion, portal inflammation, periportal necrosis, hepatocyte damage, liver weight increase, and AST/ALT elevation, were significantly impeded by oral administration of GZFLW (25 or 50 mg/kg) in mice [Fig. 2]. In addition, GZFLW mitigated Con A-induced mortality and hepatocyte death [Fig. 3]. This is an exploratory investigation of the applicable potential of GZFLW in the treatment of AIH.

The standard immunosuppressive therapy with prednisone is typically used at a dose of 30–60 mg/day (approximately 0.5–1 mg/kg) for 4 weeks and then followed by a tapering off period during remission-induction therapy for AIH [7,42]. In this study, the high dose of GZFLW administered orally was 50 mg/kg/day in mice, equivalent to approximately 2.5 g of dried crude herbs (yielding 9.8%) in 60-kg humans based on body surface area transformation. This dose is much lower than the clinically average daily dosage of 4.7 g [20]. Additionally, there is no statistical difference between 50 mg/kg GZFLW and 5 mg/kg prednisone pre-treatment [Fig. 2, Fig. 3A]. Therefore, we suggest that GZFLW may be a beneficial alternative in treating AIH.

Hepatocyte apoptosis is a hallmark of AIH that can be classified into extrinsic and intrinsic. Association between death receptor Fas and its ligand FasL initiates the extrinsic caspase-8 and -10 activation. ROS triggers the proapoptotic Bak and Bax to increase mitochondrial permeability, which induces cytochrome c release and intrinsic caspase-9 activation. Both extrinsic and intrinsic cascades activate the executioner caspases-3 and -7, resulting in DNA fragmentation and apoptotic body formation [45,46]. Targeting apoptosis has been proposed as a helpful strategy for treating AIH [[47], [48], [49], [50]]. We found that GZFLW can restrain Con A-induced DNA fragmentation (TUNEL assay), pro-apoptotic Bax expression, and caspase-3, -8, and -9 activation. Conversely, the anti-apoptotic Bcl-xl and Bcl-2 were upregulated by GZFLW pre-treatment [Fig. 3, Fig. 4]. GZFLW limited both extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic signaling, suggesting that its protective effects may be achieved by targeting extrinsic Fas/FasL activation and intrinsic ROS production.

Inflammatory oxidative stress is an important pathogenic factor in AIH, leading to the overwhelming production of ROS or lipid peroxidation in the liver. Besides, the destruction of antioxidant systems is also a characteristic symptom, indicated by antioxidant levels, nuclear activation of Nrf2, or activity of antioxidant enzymes [12,13,26,27]. As described above, ROS is an inducer of intrinsic apoptosis in hepatocytes. Several natural components, such as dihydroquercetin, pristimerin, or the traditional herbal formula Jiang-Xian HuGan, serve in the capacity of antioxidants to treat Con A-induced AIH, which is dependent on activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway [30,31,51]. GZFLW is an antioxidant that attenuates free radical-induced lysis in rat red blood cells and thoracic aorta relaxation in cholesterol-fed rabbits [28,29]. We demonstrated that GZFLW successfully improved the Con A-induced hepatic oxidative stress in mice via inhibition of MDA levels (lipid peroxidation) and elevation of GSH levels (cellular antioxidant), SOD activity (antioxidant enzyme), or nuclear Nrf2 binding ability [Fig. 5], suggesting that the protective effects of GZFLW may rely on its antioxidant activity in the treatment of AIH.

Multicellular signals mediate Con A-induced hepatic apoptosis. Con A triggers the differentiation of Th1 and Th17 cells, which induce hepatocyte necrosis and apoptosis by secreting TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 [12,13]. TNF-α and IFN-γ also facilitate the infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells into the necrotic area of the damaged liver [52]. Natural killer T cells directly induce the death of hepatocytes or sinusoid endothelial cells by expressing TNF-α and IFN-γ after binding to Con A [53]. CD8+ and natural killer T cells furnish the Fas/FasL-dependent apoptosis in hepatic cells [52]. Significantly, the upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β, TNF-α, INF-γ, IL-2, and IL-17α, were restricted by GZFLW pre-treatment in livers from Con A-primed mice [Fig. 6]. Furthermore, GZFLW relieved the Con A-induced inflammatory splenomegaly and splenic CD4+INF-γ+ or CD8+INF-γ+ T cell activation in mice (Fig. 7). GZFLW may be utilized as an immunomodulator to confine hepatic apoptosis of AIH.

Neutrophils and Kupffer cells also involve AIH [54,55]. Con A is capable of binding to the mannose receptor in neutrophils and Kupffer cells to increase superoxide anions and ROS release as well as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, or macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) expression, which in turn deteriorates hepatic apoptosis and AIH [2,12,13]. MPO is predominantly expressed in neutrophils and monocytes, and MPO activity can be employed as an inflammatory indicator in vivo [56]. The hepatic MPO activity was increased in Con A-primed mice and curbed by oral administration of GZFLW [Fig. 6F]. Together, we convey that GZFLW may occupy the position of an inclusive immunomodulator against hepatic apoptosis and oxidative inflammatory responses of AIH.

5. Conclusion

Our study highlights the significant potential of traditional herbal medicine, GZFLW, in treating AIH. The therapeutic efficacy of GZFLW appears to be associated with its antiapoptotic, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties, as evidenced in Con A-induced mice. Moreover, GZFLW demonstrates comparable effectiveness to the standard immunosuppressive drug prednisone. We suggest that GZFLW could serve as a promising alternative for treating AIH.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan [112-2320-B-650-001, 112-2321-B-182-003, 112-2321-B-255-001, 111-2320-B-255-006-MY3, 111-2321-B-255-001, and 111-2321-B-182-001], Chang Gung University of Science and Technology [ZRRPF3L0091 and ZRRPF3N0101], Chang Gung Memorial Hospital [CMRPG3M0431-2, CMRPF1M0131-2, CMRPF1M0101-2, CMRPF1N0021, and BMRP450], and E-Da Hospital [EDAHS111002]. The funding sources had no role in the study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit this article for publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2024.100731.

Contributor Information

Chi-Chen Lin, Email: lincc@email.nchu.edu.tw.

Po-Jen Chen, Email: ed113510@edah.org.tw.

Tsong-Long Hwang, Email: htl@mail.cgust.edu.tw.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Manns MP, Lohse AW, Vergani D. Autoimmune hepatitis--Update 2015. J Hepatol. 2015;62(1 Suppl):S100–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Covelli C, Sacchi D, Sarcognato S, Cazzagon N, Grillo F, Baciorri F, et al. Pathology of autoimmune hepatitis. Pathologica. 2021;113(3):185–193. doi: 10.32074/1591-951X-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McFarlane IG. Definition and classification of autoimmune hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22(4):317–324. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vuerich M, Wang N, Kalbasi A, Graham JJ, Longhi MS. Dysfunctional immune regulation in autoimmune hepatitis: from pathogenesis to Novel therapies. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.746436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katsumi T, Ueno Y. Epidemiology and surveillance of autoimmune hepatitis in Asia. Liver Int. 2022;42(9):2015–2022. doi: 10.1111/liv.15155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hahn JW, Yang HR, Moon JS, Chang JY, Lee K, Kim GA, et al. Global incidence and prevalence of autoimmune hepatitis, 1970-2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;65 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Autoimmune hepatitis: standard treatment and systematic review of alternative treatments. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(33):6030–6048. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i33.6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muratori L, Lohse AW, Lenzi M. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. BMJ. 2023;380 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibrahim SRM, Sirwi A, Eid BG, Mohamed SGA, Mohamed GA. Summary of natural products ameliorate concanavalin A-induced liver injury: structures, sources, pharmacological effects, and mechanisms of action. Plants(Basel) 2021;10(2):228. doi: 10.3390/plants10020228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park J, Kim H, Lee IS, Kim KH, Kim Y, Na YC, et al. The therapeutic effects of Yongdamsagan-tang on autoimmune hepatitis models. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;94:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang T, Men R, Hu M, Fan X, Yang X, Huang X, et al. Protective effects of Punica granatum (pomegranate) peel extract on concanavalin A-induced autoimmune hepatitis in mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;100:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.12.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Hao H, Hou T. Concanavalin A-induced autoimmune hepatitis model in mice: mechanisms and future outlook. Open Life Sci. 2022;17(1):91–101. doi: 10.1515/biol-2022-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webb GJ, Hirschfield GM, Krawitt EL, Gershwin ME. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of autoimmune hepatitis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2018;13:247–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Bai Y, Gao M, Zhang J, Dong G, Yan F, et al. Hepatoprotective effect of capsaicin against concanavalin A-induced hepatic injury via inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(5):3029–3038. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park JS, Park S, Cheon CH, Jo SC, Cho HB, Lim EM, et al. Effects and safety of gyejibongnyeong-hwan on dysmenorrhea caused by blood stagnation: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/424730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang RC, Tsai YT, Lai JN, Yeh CH, Wu CT. The traditional Chinese medicine prescription pattern of endometriosis patients in taiwan: a population-based study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/591391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yen HR, Chen YY, Huang TP, Chang TT, Tsao JY, Chen BC, et al. Prescription patterns of Chinese herbal products for patients with uterine fibroid in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;171:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai PJ, Lin YH, Chen JL, Yang SH, Chen YC, Chen HY. Identifying Chinese herbal medicine network for endometriosis: implications from a population-based database in taiwan. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/7501015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung YC, Kao CW, Lin CC, Liao YN, Wu BY, Hung IL, et al. Chinese herbal products for female infertility in taiwan: a population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltim) 2016;95(11) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo Y, Mao P, Chen P, Li C, Fu X, Zhuang M. Effect of Guizhi Fuling Wan in primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized controlled trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;307 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M, Hung A, Li H, Yang AWH. A classic herbal formula guizhi fuling wan for menopausal hot flushes: from experimental findings to clinical applications. Biomedicines. 2019;7(3):60. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines7030060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka K, Chiba K, Nara K. A review on the mechanism and application of keishibukuryogan. Front Nutr. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.760918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujimoto M, Tsuneyama K, Kinoshita H, Goto H, Takano Y, Selmi C, et al. The traditional Japanese formula keishibukuryogan reduces liver injury and inflammation in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1190:151–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai CC, Kao CT, Hsu CT., Lin CC, Lin JG. Evaluation of four prescriptions of traditional Chinese medicine: syh-mo-yiin, guizhi-fuling-wan, shieh-qing-wan and syh-nih-sann on experimental acute liver damage in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;55(3):213–222. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(96)01503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye T, Wang T, Yang X, Fan X, Wen M, Shen Y, et al. Comparison of concanavalin a-induced murine autoimmune hepatitis models. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;46(3):1241–1251. doi: 10.1159/000489074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pemberton PW, Aboutwerat A, Smith A, Burrows PC, McMahon RF, Warnes TW. Oxidant stress in type I autoimmune hepatitis: the link between necroinflammation and fibrogenesis? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1689(3):182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaffe ET, Rigopoulou EI, Koukoulis GK, Dalekos GN, Moulas AN. Oxidative stress and antioxidant status in patients with autoimmune liver diseases. Redox Rep. 2015;20(1):33–41. doi: 10.1179/1351000214Y.0000000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sekiya N, Goto H, Shimada Y, Terasawa K. Inhibitory effects of Keishi-bukuryo-gan on free radical induced lysis of rat red blood cells. Phytother Res. 2002;16(4):373–376. doi: 10.1002/ptr.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekiya N, Goto H, Tazawa K, Oida S, Shimada Y, Terasawa K. Keishi-bukuryo-gan preserves the endothelium dependent relaxation of thoracic aorta in cholesterol-fed rabbit by limiting superoxide generation. Phytother Res. 2002;16(6):524–528. doi: 10.1002/ptr.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao M, Chen J, Zhu P, Fujino M, Takahara T, Toyama S, et al. Dihydroquercetin (DHQ) ameliorated concanavalin A-induced mouse experimental fulminant hepatitis and enhanced HO-1 expression through MAPK/Nrf2 antioxidant pathway in RAW cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;28(2):938–944. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang HH, Li HL, Li YX, You Y, Guan YY, Zhang SL, et al. Protective effects of a traditional Chinese herbal formula Jiang-Xian HuGan on Concanavalin A-induced mouse hepatitis via NF-kappaB and Nrf2 signaling pathways. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;217:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pellicano R, Ferro A, Cicerchia F, Mattivi S, Fagoonee S, Durazzo M. Autoimmune hepatitis and fibrosis. J Clin Med. 2023;12(5):1979. doi: 10.3390/jcm12051979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heymann F, Hamesch K, Weiskirchen R, Tacke F. The concanavalin A model of acute hepatitis in mice. Lab Anim. 2015;49(1 Suppl):12–20. doi: 10.1177/0023677215572841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang XL, Feng ST, Wang YT, Chen NH, Wang ZZ, Zhang Y. Paeoniflorin: a neuroprotective monoterpenoid glycoside with promising anti-depressive properties. Phytomedicine. 2021;90 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lai KH, Lu MC, Du YC, El-Shazly M, Wu TY, Hsu YM, et al. Cytotoxic lanostanoids from poria cocos. J Nat Prod. 2016;79(11):2805–2813. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dabbou S, Lussiana C, Maatallah S, Gasco L, Hajlaoui H, Flamini G. Changes in biochemical compounds in flesh and peel from Prunus persica fruits grown in Tunisia during two maturation stages. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;100:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michalak A, Mosinska P, Fichna J. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their derivatives: therapeutic value for inflammatory, functional gastrointestinal disorders, and colorectal cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:459. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SR, Lee S, Moon E, Park HJ, Park HB., Kim KH. Bioactivity-guided isolation of anti-inflammatory triterpenoids from the sclerotia of Poria cocos using LPS-stimulated Raw264.7 cells. Bioorg Chem. 2017;70:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nie A, Chao Y, Zhang X, Jia W, Zhou Z, Zhu C. Phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of wolfiporia cocos (F.A. Wolf) ryvarden & gilb. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.505249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei C, Wang H, Sun X, Bai Z, Wang J, Bai G, et al. Pharmacological profiles and therapeutic applications of pachymic acid. Exp Ther Med. 2022;24(3):547. doi: 10.3892/etm.2022.11484. (Review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou YX, Gong XH, Zhang H, Peng C. A review on the pharmacokinetics of paeoniflorin and its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;130 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lohse AW, Sebode M, Jorgensen MH, Ytting H, Karlsen TH, Kelly D, et al. Second-line and third-line therapy for autoimmune hepatitis: a position statement from the European reference network on hepatological diseases and the international autoimmune hepatitis group. J Hepatol. 2020;73(6):1496–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang Y, Li F, Wei S, Liu X, Wang Y, Liu H, et al. Metabolomics profiling in a mouse model reveals protective effect of Sancao granule on Con A-Induced liver injury. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;238 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.111838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chi XL, Xiao HM, Xie YB, Cai GS, Jiang JM, Tian GJ, et al. Protocol of a prospective study for the combination treatment of Shu-Gan-jian-Pi decoction and steroid standard therapy in autoimmune hepatitis patients. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):505. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1486-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Czaja AJ. Targeting apoptosis in autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(12):2890–2904. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwabe RF, Luedde T. Apoptosis and necroptosis in the liver: a matter of life and death. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(12):738–752. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0065-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tian X, Liu Y, Liu X, Gao S, Sun X. Glycyrrhizic acid ammonium salt alleviates Concanavalin A-induced immunological liver injury in mice through the regulation of the balance of immune cells and the inhibition of hepatocyte apoptosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;120 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li M, Zhao H, Wu J, Wang L, Wang J, Lv K, et al. Nobiletin protects against acute liver injury via targeting c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-Induced apoptosis of hepatocytes. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(27):7112–7120. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c01722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feng J, Niu P, Chen K, Wu L, Liu T, Xu S, et al. Salidroside mediates apoptosis and autophagy inhibition in concanavalin A-induced liver injury. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15(6):4599–4614. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fan X, Men R, Wang H, Shen M, Wang T, Ye T, et al. Methylprednisolone decreases mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and autophagy dysfunction in hepatocytes of experimental autoimmune hepatitis model via the akt/mTOR signaling. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1189. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El-Agamy DS, Shaaban AA, Almaramhy HH, Elkablawy S, Elkablawy MA. Pristimerin as a novel hepatoprotective agent against experimental autoimmune hepatitis. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:292. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ge W, Gao Y, Zhao Y, Yang Y, Sun Q, Yang X, et al. Decreased T-cell mediated hepatic injury in concanavalin A-treated PLRP2-deficient mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;85 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takeda K, Hayakawa Y, Van Kaer L, Matsuda H, Yagita H, Okumura K. Critical contribution of liver natural killer T cells to a murine model of hepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(10):5498–5503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040566697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Y, Yan M, Zhang H, Wang X. Substance P participates in immune-mediated hepatic injury induced by concanavalin A in mice and stimulates cytokine synthesis in Kupffer cells. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6(2):459–464. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bonder CS, Ajuebor MN, Zbytnuik LD, Kubes P, Swain MG. Essential role for neutrophil recruitment to the liver in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. J Immunol. 2004;172(1):45–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen PJ, Tseng HH, Wang YH, Fang SY, Chen SH, Chen CH, et al. Palbociclib blocks neutrophilic phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity to alleviate psoriasiform dermatitis. Br J Pharmacol. 2023;180(16):2172–2188. doi: 10.1111/bph.16080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.