Abstract

Neuromodulation therapy comprises a range of non-destructive and adjustable methods for modulating neural activity using electrical stimulations, chemical agents, or mechanical interventions. Here, we discuss how electrophysiological brain recording and imaging at multiple scales, from cells to large-scale brain networks, contribute to defining the target location and stimulation parameters of neuromodulation, with an emphasis on deep brain stimulation (DBS).

Subject terms: Parkinson's disease, Parkinson's disease

Electrophysiological brain mapping to enhance neuromodulation targeting

Please see Section 4 for an overview of fundamental concepts in signal processing for electrophysiology.

Non-invasive brain recordings

Electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) are non-invasive methods for recording neurophysiological activity at the sub-millisecond time scale. Their unique temporal resolution enables the direct measurement of brain rhythms and other complex features of brain activity in relation to behaviour and symptoms. With high-density scalp recordings, EEG and MEG have substantial source mapping capabilities, especially when the recordings are geometrically co-registered with the individual’s brain anatomy obtained from structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A range of inter-regional functional connectivity measures can also be derived from EEG and MEG source maps, which temporal resolution enables functional explorations across a wide frequency spectrum (from below 1 Hz to 300 Hz and above)1. Combined, these benefits enable the definition of neurophysiological traits for a diversity of neurological conditions. Symmetrically, they can also specify neuromodulation therapies, both for targeting in terms of anatomical location and stimulation parameters. In the next two subsections, we summarize the respective assets of EEG and MEG, with a focus on applications to movement disorders, including Parkinson’s disease (PD), essential tremor (ET), and dystonia.

Electroencephalography (EEG) and Magnetoencephalography (MEG)

Electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) are widely used neuroimaging techniques for studying brain activity. While EEG captures electrical signals through scalp electrodes, MEG detects the magnetic fields generated by neural activity using external sensors. Both techniques provide high temporal resolution, making them essential for understanding neurophysiological processes in real time.

EEG measures the summation of electrochemical signals as they propagate between neurons. These signals are generated by the synchronized activity of large populations of pyramidal neurons aligned geometrically2. While EEG offers high temporal precision and is relatively low-cost and non-invasive3,4, its spatial resolution is limited to detecting signals on the scale of centimeters5,6. Despite this, EEG has become a fundamental tool in cognitive neuroscience research and clinical applications, particularly for studying movement disorders.

Conversely, MEG7 measures the magnetic fields induced by neural activity and offers greater spatial resolution than EEG due to minimal interference from scalp and skull tissues. MEG signals originate from the same neural assemblies that generate EEG signals, primarily cortical pyramidal cells8. However, MEG is also sensitive to subcortical structures such as the amygdala and brainstem9–11, as well as action potential volleys12,13. With potentially millimetre-scale spatial resolution14 and the ability to capture both oscillatory and aperiodic signals15,16, MEG is highly effective for studying brain activations across time and space.

EEG and MEG have both been employed to investigate the alterations in neurophysiological activity associated with movement disorders. For example, in PD, EEG has detected abnormal beta-band oscillations at rest17, which are normalized by deep brain stimulation (DBS), leading to improved motor symptoms18,19. MEG, with its superior spatial resolution, has further refined these findings by showing how alterations in beta oscillations affect movement planning in PD patients20. MEG has also demonstrated the involvement of oscillatory activity across multiple frequency bands, which are crucial for motor control and cognitive functions in PD21,22. These frequency-specific neural markers are critical for refining neuromodulation therapies, including transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which show promise in modulating motor and cognitive functions in PD patients23–28.

Both EEG and MEG are valuable for studying inter-regional brain connectivity. EEG studies have revealed altered directional coherence between the cerebellum and premotor cortex in patients with ET and PD, suggesting that the normal flow of information between these regions is disrupted in movement disorders1,29. MEG, with its ability to detect cortical-subcortical interactions, has further demonstrated how these disruptions extend to deeper brain structures, implicating cortico-thalamo-cerebellar circuits in the pathophysiology of tremors30.

In the case of ET, both techniques have provided critical insights into the neurophysiological basis of tremor. EEG has detected event-related potentials in peri-motor cortical regions at latencies of 0.9–13.9 ms after DBS onset31, aligning closely with findings from invasive recordings32. Similarly, MEG has been used to trace rhythmic activity in the tremor frequency range, offering detailed spatial mapping of the neural oscillations underlying ET33,34. For dystonia, EEG and MEG have uncovered abnormal synchronizations within cortico-striato-pallido-thalamo-cortical circuits and cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathways35,36, highlighting the complex network dysfunctions driving dystonic movements.

Although EEG and MEG have traditionally been regarded as measuring cortical activity due to their sensitivity to large-scale synchronized neural activity near the brain’s surface, both techniques can detect deeper brain signals with the right experimental designs. MEG, in particular, has been shown to pick up signals from subcortical structures, such as the amygdala and brainstem, with greater signal-to-noise ratio when using advanced source localization strategies30. The integration of MEG with invasive electrophysiological methods has further linked subcortical dysfunctions to cortical activity patterns, deepening our understanding of brain networks involved in movement disorders37,38.

Together, EEG and MEG continue to provide complementary insights into the spatiotemporal dynamics of brain activity, and their combined use has proven instrumental in advancing both our theoretical understanding and therapeutic interventions for movement disorders like PD, ET, and dystonia.

Invasive brain recordings

The spatial resolution of existing non-invasive recording methods is not sufficient to examine single neuron activity or local field potentials. Invasive recordings such as local field potentials (LFP) and micro-electrode recordings (MER) fill this gap and provide essential information about neural activity at smaller spatial scales in patients with movement disorders.

Local field potential (LFP)

Local field potentials (LFP) are the electrical potential in the extracellular space surrounding neurons and can be recorded in human participants using invasive electrodes. This is done most commonly in patients with movement disorders in the context of surgery, e.g., during implantation or battery replacement of DBS. These recordings measure the combined local neurophysiological activity of the implanted nucleus and surrounding tissues, and often capture oscillatory patterns relevant for treatment of movement disorders39,40.

The majority of DBS-LFP research has focused on the STN, as it is the most prominent DBS target for in treating motor symptoms in PD patients. LFP recordings were used to first demonstrate alterations of oscillatory activity in the basal ganglia of patients with PD39,41, which was once contentious but is now considered a pathophysiological hallmark of the disease. These alterations are normalized by dopamine therapy and related to the severity of motor impairments40,42. Further research using LFP recordings has demonstrated that the STN, in collaboration with the globus pallidus externus, serves as the originator of pathological somato-motor cortical beta activity in PD43. LFP recordings from the STN have also revealed neurophysiological alterations relevant to non-motor functions in PD, particularly involving lower frequencies ranging from 5 to 13 Hz44. Frequency-defined functional connectivity can also be assessed between deep-brain nuclei with LFP recordings. For instance, 3–10 Hz coherence between LFP recordings of the GPi and STN, the GPi and thalamus, and the thalamus and cortex are all related to the severity of parkinsonian tremor45–47.

LFP recordings have also revealed that heightened low-frequency (4–12 Hz) oscillatory activity of globus pallidus internus (GPi) neurons are a promising modifiable marker of dystonia48. The severity of dystonic symptoms correlates with the magnitude of these low-frequency GPi oscillations49,50, and they are suppressed by therapeutic DBS with proportional clinical improvement50–53. Consequently, the GPi has emerged as the main target for implanting DBS electrodes in dystonic patients.

Microelectrode recording (MER)

Microelectrode recording (MER) involves the insertion of a fine micro-electrode into brain tissue to record focal electrophysiology. This electrode measures the activity of multiple cells simultaneously and the resulting data need to be post-processed to sort between the contributions of individual neurons. While studies utilizing MER in patients with PD are limited, those that have been conducted primarily focus on localizing, identifying, and confirming target structures for neuromodulation. As the main target for DBS placement in PD patients, the STN is the focus of most MER studies. Utilizing MER enables the identification of more accurate electrode placement54–57. Sensorimotor regions and other sub-territories of the STN can also be demarcated during DBS surgery based on MER55, as can the borders of the GPi for DBS in patients with dystonia and PD58.

MER has also proven valuable in targeting the ventral intermediate nucleus (VIM) of the thalamus for DBS in patients with ET59. By providing real-time electrophysiological feedback, MER enhances the precision of electrode placement during surgery. This technique helps surgeons to differentiate the VIM from adjacent structures, which is crucial for optimizing tremor suppression while minimizing side effects. Studies have demonstrated that the use of MER improves clinical outcomes for DBS in ET patients59,60, allowing for more accurate targeting and potentially reducing post-operative complications.

Multimodal brain recordings

Recording electrophysiology simultaneously using multiple of the aforementioned tools can provide benefits that the methods do not possess in isolation. Most notable among these are improved spatial accuracy (EEG-MEG) and the ability to associate whole-cortex neurophysiological activity to that of deep-brain nuclei in real time (M/EEG-LFP).

Combined EEG-MEG recording

Despite their identical temporal resolutions, the combination of simultaneously-collected MEG and EEG for source imaging consistently demonstrates superior spatial accuracy compared to either modality alone61. This enhanced localization stems from the distinct signals detectable with each modality, rather than from a mere increase in the total channel number. MEG’s capability for more accurate source imaging, owing to low magnetic interference from intervening tissues7, complements EEG’s sensitivity in detecting activity of deeper subcortical areas7,61–63. The activity of the thalamus and cerebellum can also be identified more robustly with combined EEG-MEG compared to when only EEG is used63. Therefore, the integration of MEG and EEG data proves crucial for conducting spatiotemporal studies of the whole human brain with maximal resolution64.

Despite this potential, relatively few studies have employed combined EEG-MEG to investigate the effects of movement disorders and DBS therapy. Future research should leverage these benefits towards the study of patients with movement disorders.

Combined EEG-LFP recording

Concurrent EEG and striatal LFP recordings have suggested that beta activity in the striatum is influenced in a task-dependent manner following dopamine depletion in PD65–67. These results indicate that the absence of dopamine in the sensorimotor striatum does not eliminate typical oscillatory patterns or introduce new frequencies of oscillations, and instead selectively reinforces inherent ones. This reinforcement primarily affects oscillations below 55 Hz, with the frequency band implicated dependent on the task being performed. Notably, this enhancement emerges only after extensive training.

Regarding the effects of STN-DBS on cortical activity, patients with PD exhibit peak frequency enhancement and power reduction in the alpha band68, and cortical alpha power has been positively correlated with clinical improvement following stimulation69. Suppression of beta oscillations in the temporal cortex70 and enhanced high gamma oscillatory activity in the right frontal cortex70 during DBS are also associated with motor improvement in PD.

EEG-LFP recordings have been employed to investigate connectivity between deep brain structures and the cortex in patients with movement disorders. For instance, in patients with PD and dystonia, movement-related coherence with the motor cortex is reduced to the STN and GPi, respectively46,71,72. This research has also distinguished between high (13–20 Hz) and low (20–30 Hz) beta oscillations in their relevance to PD symptoms73–76, with the effect of DBS on cortico-pallidal coherence in PD patients manifesting as a decrease in the high-beta range. Coherence analysis between cortical EEG and LFP signals in the GPi of patients with dystonia has identified two distinct types of dystonic symptoms77: alpha band power and coherence are associated with phasic symptoms, while delta power is linked to tonic symptoms.

Combined MEG-LFP recording

The most common combination of concurrent MEG with deep-brain neurophysiological recordings is in the context of deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) to treat movement impairments in patients with PD. Despite its efficacy across a range of disorders78, the mechanisms underlying the multifaceted effects of DBS remain unclear37,79. MEG is particularly useful in the study of these mechanisms, as it is not as susceptible as EEG to the electromagnetic artifact caused by active DBS37 and to the changes in tissue electrical conductance resulting from the burr holes required for DBS electrode implantation38. Current artefact removal and attenuation techniques enable advanced analyses of MEG-DBS concurrent recording, including during active DBS stimulation37,38.

Brain network analyses have come at the forefront of current approaches to understanding DBS mechanisms80, with MEG contributing valuable insights37. Here too, the frequency-signature of these networks is considered as a key parameter of their clinical significance. For example, beta-frequency signalling between the STN and (pre-)motor regions are distinct from those between STN and temporal cortices in the alpha band81,82. Dysfunction of cortical beta-frequency networks is linked to motor impairments via deficient dopaminergic signalling from the substantia nigra (SN)83, indicating the potential role of STN-DBS in compensating for loss of SN integrity by restoring balanced levels of beta-network connectivity along the hyper-direct pathway. Indeed, although both local STN beta activity and STN-cortical beta coherence are reduced by the application of DBS73,84, the amount of beta-band coherence between STN and cortical regions better predicts DBS efficacy than local STN measures of spectral power85.

Non-invasive measures of cortico-STN beta coherence may help personalize neuromodulation parameters. Potentially, the timing, amplitude, and frequency parameters of DBS may be adapted for each individual to optimally reduce pathological beta synchrony while limiting secondary tissue scarring and desensitization. In a similar vein, brain-computer interfaces have been used to optimize DBS in patients with PD, but have only considered local STN beta synchrony measures to adjust DBS parameterss86. Further research combining DBS-LFP recordings with MEG is required to better understand the cognitive and affective impacts of DBS in patients with PD and other disorders. For example, recent work has shown that DBS applied during specific phases of decision making impacts the delay to decision87, an effect related to how DBS interacts with local STN beta oscillations. Using a similar paradigm during MEG would help understand how this effect may be mediated by network-level interactions across the entire cortex.

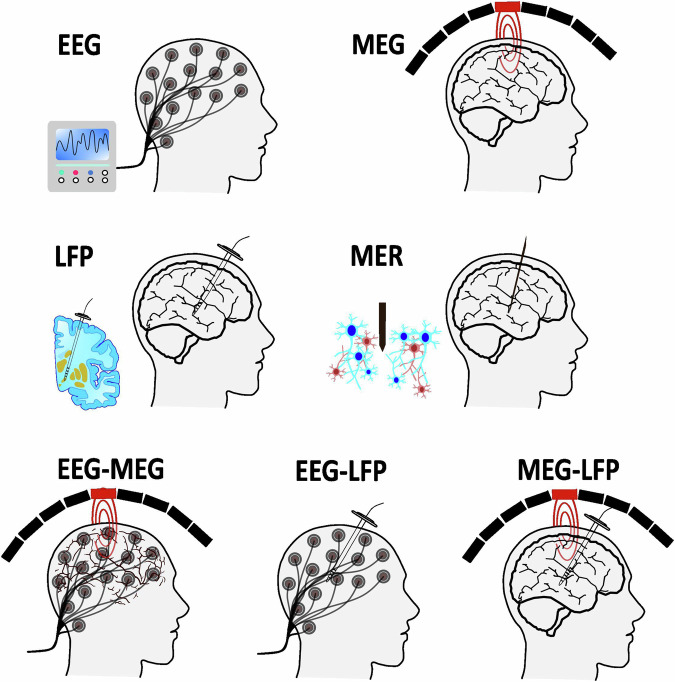

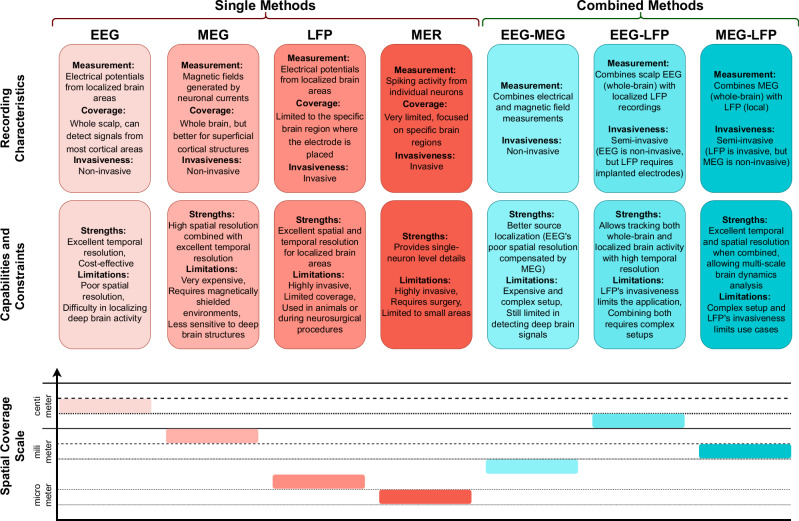

To summarize this section and provide a visual insight, a schematic representation of single and combinedelectrophysiological methods, along with a comparative analysis of electrophysiological recording methods, isdepicted in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of single and combined electrophysiology methods.

Fig. 2. Characteristics and Comparative Analysis of Electrophysiological Recording Methods.

This figure presents the strengths, limitations, and spatial resolution of the single and combined electrophysiological techniques discussed in the paper.

DBS-induced spectral changes in the subthalamic LFP

One way of studying mechanisms underlying DBS and personalising stimulation is to investigate DBS-induced or evoked LFP changes in the subthalamic nucleus such as beta/gamma power suppression, evoked resonant neural activity (ERNA), finely-tuned gamma (FTG) oscillations and the aperiodic exponent of the power spectrum.

DBS-induced power suppression in the STN has been reported in multiple studies, with a focus on the beta range given the correlation with bradykinesia and rigidity in PD patients19,84,88,89. Notably, this power suppression is not specific to the beta range and extends into the low gamma range5. Beta and low gamma oscillations are almost instantaneously suppressed when stimulation is switched on and remain low throughout continuous DBS90. Once stimulation is switched off, both activities return to baseline more slowly, with low gamma recovering faster than beta activity19,84,88–90. DBS-induced power suppression has been suggested as an indicator of good lead placement and may help explain the mechanism underlying DBS: high-frequency stimulation desynchronises excessive beta activity which allows for relay of physiological activity through STN91. The link between beta activity and Parkinsonian symptoms, as well as its rapid suppression by classical DBS, has made beta activity a salient marker for aDBS. However, beta activity is limited by its sensitivity to noise contamination during movement. Furthermore, beta activity decreases at night92,93, which would result in an undesired proportional reduction of stimulation intensity and could be counterproductive in patients that profit from DBS during sleep93–95.

ERNA presents as a high-frequency, under-damped oscillation that can be observed in the STN and GPe/i of PD patients after DBS to STN or GPi96,97. ERNA is believed to arise from rhythmic inhibitory input from prototypic GPe neurons to STN98,99, however, simpler models utilising a single population of glutamatergic neurons can also model ERNA modulation during continuous STN-DBS by assuming synaptic failure as an underlying mechanism100. ERNA responses comprise fast and slow dynamics90,98: high-frequency DBS modulates its amplitudes and latencies over the first ten pulses, and skipping a single pulse affects subsequent ERNA pulse-responses98. Responses of ERNA dynamics to DBS reach a steady state after about 70 seconds90, and once DBS is stopped they slowly return to baseline levels on a timescale reminiscent of beta power recovery98.

Within STN, ERNA is highly focal and localises to a similar hot spot as the optimal one for clinical DBS benefit101,102. Several groups have also reported correlations between ERNA and clinical scores or beta activity90,97,103–105, and ERNA is modulated by dopaminergic medication98. Therefore, ERNA has been suggested as a marker for DBS contact selection and outcome prediction106. In addition, ERNA has been recorded during general anaesthesia which makes it a suitable intraoperative marker for lead placement107, and scales with increasing stimulation frequency and intensity98. ERNA can also be recorded from the STN of patients with cervical dystonia, which lacks the widespread neurodegeneration observed in PD101, suggesting that ERNA may be present in the healthy STN.

FTG is narrowband activity between 60–90 Hz that can be induced by levodopa or DBS, and less often can be recorded in the absence of either108. It is modulated by movement and both cortical FTG108,109 and cortical-subcortical FTG coherence108,110 have been suggested as potential markers for dyskinesia in PD patients. However, FTG is observed in only a subset of patients and is more prevalent in the superior margin of the STN, which may limit its clinical use108. In light of spurious horizontal line artefacts at sub-harmonics of stimulation, FTG entrainment has to be interpreted with care. DBS-induced subthalamic FTG is not locked at a sub-harmonic of stimulation and decreases with continuous DBS, this activity is unlikely to be artefactual111. Inversely, cortical FTG is entrained at a subharmonic of stimulation, but is affected by levodopa administration and disappears as DBS intensity is increased, which again makes this activity unlikely to be artefactual112.

Long considered noise, the aperiodic exponent of the power spectrum has now been shown to be modulated by several physiological changes and affected by excitation-inhibition balance in several studies of animal models and humans113–115. Aperiodic exponents of high-frequency (30–100 Hz) subthalamic LFPs increase with levodopa and high-frequency DBS, in keeping with increased STN inhibition effects116. As these exponents must be calculated over relatively long periods to reduce noise, they may only be useful in conjunction with slow beta-triggered aDBS117.

Electrophysiological biomarkers which can foster closed-loop deep brain stimulation

In this section, we aim to elucidate the electrophysiological biomarkers that could facilitate the optimization of closed-loop adaptive DBS (aDBS). Classic DBS employs an open-loop stimulation approach, wherein electrical impulses are continuously delivered to the target tissue without any feedback mechanism. In contrast, emerging closed-loop approaches administer electrical stimulation based on the ongoing electrophysiological activities of the target (or connected) regions110. These cortical and/or subcortical electrophysiological feedback signals must be recorded and analysed in real-time alongside delivery of the stimulation pulses, with a specific emphasis on the control policies employed to adjust stimulation delivery118.

As mentioned above, PD is characterized by exaggerated beta oscillations in the LFP recordings of STN in patients, which are closely associated with motor symptoms46,72. The consistency and magnitude of these findings have positioned them as a potential biomarker for DBS feedback in PD119,120. The optimal DBS biomarker should vary meaningfully from patient to patient in a way that is representative of each individual’s symptom profile. Studies have revealed that beta oscillations can be divided into two functionally distinct sub-ranges: low-beta (13–20 Hz) and high-beta (20–30 Hz) oscillations, which seem to signal pathological and healthy motor function, respectively73,121,122. Consequently, it has been proposed to use low-beta frequency activity instead of canonical beta oscillatory power as a biomarker in aDBS123. A combination of several frequency ranges has been suggested to result in a more accurate detection of tremor in PD patients124,125. For instance, low-frequency (3–14 Hz) oscillatory activities in the basal ganglia have been proposed as a biomarker for tremor and non-motor symptom severity (e.g. impulsivity and depression) in PD patients126,127. Slowing of cortical neurophysiology across various frequency bands in PD has been linked to both cognitive and motor impairments. Moreover, this slowing has been shown to be sensitive to individual patient profiles and can be measured non-invasively, making it another emerging target for biomarker development21,22.

In dystonia, there is an enhancement of GPi activity from 4–12 Hz that is closely linked to the severity of symptoms49,52, making this frequency range a promising biomarker for aDBS in dystonic patients53,128. One study50 showed that in the dystonic and parkinsonian GPi, low-frequency and beta alterations, respectively, manifest as increases in phasic bursts characterized by episodes of relatively fast synchrony followed by intervals of quiescence. Further, the application of aDBS in the GPi was feasible and well-tolerated in both diseases. This indicates that heightened low-frequency burst amplitudes could serve as valuable feedback for guiding GPi-aDBS interventions in dystonia.

Unlike in PD and dystonia, robust neurophysiological biomarkers directly correlated with symptoms are lacking in ET, representing a challenge for aDBS in this patient group. Current candidate biomarkers instead include the assessment of tremor activity using external sensors such as accelerometers or electromyography (EMG)128, which measure inertial acceleration and muscular electrical impulses, respectively. Combined EEG-EMG recordings can be used to evaluate cortico-muscular interactions and show great promise in identifying biomarkers during clinical rehabilitation for neuromotor diseases129. Two primary approaches have been suggested towards this goal. Tremor amplitude may be utilized, where the onset of a tremor episode triggers stimulation based on predetermined amplitude thresholds, thus reducing tremor severity130,131. It has also been suggested consider tremor phase: stimulating the motor cortex out-of-phase to disrupt synchrony may modulate tremor severity132,133. Though both approaches have only been demonstrated through proof-of-concept studies, these results suggest that adaptive stimulation based on tremor amplitude and phase could be beneficial in reducing symptoms in ET. Further validation with chronic stimulation in real-world settings and direct comparisons with conventional stimulation therapies are essential.

Fundamental concepts in signal processing for electrophysiology

Understanding signal processing concepts is critical for interpreting electrophysiological findings and their implications for therapeutic interventions. This section outlines key terms and principles related to signal processing that are essential for comprehending the methodologies employed in electrophysiology.

Power bands: Refers to specific frequency ranges of brain oscillations (e.g., delta: 2–4 Hz, theta: 5–7 Hz, alpha: 8–12 Hz, beta: 15–30 Hz, gamma: > 30 Hz). Each band is associated with different computational processes and cognitive and motor functions in the brain.

Frequency resolution: The ability to distinguish between different frequencies of brain activity in an electrophysiological recording. Higher resolution allows for more precise identification of activity in faster frequencies.

Temporal resolution: Refers to the precision of timing in capturing changes in neural activity and is directly related to frequency resolution. Different modalities (e.g., EEG, MEG) have varying temporal resolutions, affecting how quickly each can detect changes in brain activity.

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): A measure that compares the level of a desired signal to the level of background noise. High SNR is essential for electrophysiological recordings, especially when trying to discern patterns of brain activity that are subtle or highly variable.

Spatial resolution: The ability to localize the origins of brain activity accurately. Different modalities offer different spatial resolutions, affecting the understanding of where in the brain specific electrophysiological changes occur.

Filtering techniques: Methods used to isolate specific frequency bands from raw “broadband” data, which can include low-pass, high-pass, band-pass, or notch filters.

Event-related potentials/Fields (ERPs/ERFs): Measured electrophysiological responses in the brain that follow sensory, cognitive, or motor events. These are typically quantified after averaging across multiple stimulus presentations, and understanding their amplitude, latency, and other characteristics can help refine therapeutic interventions.

Functional connectivity: A class of analytical approaches that are used to assess the statistical interactions between electrophysiological signals from different brain areas. These measures are used to examine functional networks between regions, and how these networks may be influenced by disease states and therapeutic interventions.

Spectral analysis: Techniques such as the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) that decompose electrophysiological time series into their constituent frequencies, allowing for the examination of different frequency bands.

Aperiodic activity: Non-oscillatory/arrhythmic signals that can provide insights into the underlying biophysical and computational features of an electrophysiological signal, such as the relative excitability of a brain region.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information for Review Paper: Key Concepts in Neurophysiological Data Analysis for Parkinson’s Disease

Acknowledgements

This work was supported to A.I.W. by a grant F32-NS119375 from the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship (BPF-186555) and the Tier-2 Canada Research Chair in Neurophysiology of Aging and Neurodegeneration (CRC-2023-00300) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG): SFB-TRR-295, MU 4354/1-1, and the Fondazione Grigioni per il Morbo di Parkinson (to M.M.). S.B. is supported by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH, R01-EB026299-05), the Tier-1 CIHR Canada Research Chair of Neural Dynamics of Brain Systems (CRC-2017-00311), and a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (436355-13). H.T. and C.W. are supported by the Medical Research Council UK [MC_UU_00003/2, MR/V00655X/1, MR/P012272/1], the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) and the Rosetrees Trust.

Author contributions

M.M. conceived and designed the study. A.A., A.I.W., C.W. performed the investigation. A.A., A.I.W., C.W. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. A.A., A.I.W, C.W., S.B., H.T., and M.M. contributed to manuscript revision and read and approved the submitted version.

Data availability

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

Author M.M. is the Deputy Editor-in-Chief of npj Parkinson’s Disease. This did not influence the peer review or editorial decision process.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41531-024-00847-3.

References

- 1.Muthuraman, M. et al. Cerebello-cortical network fingerprints differ between essential, Parkinson’s and mimicked tremors. Brain141, 1770–1781 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson, A. F. & Bolger, D. J. The neurophysiological bases of EEG and EEG measurement: A review for the rest of us. Psychophysiology51, 1061–1071 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoffelen, J. M. & Gross, J. Source connectivity analysis with MEG and EEG. Hum. brain Mapp.30, 1857–1865 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalal, S. S. et al. Five-dimensional neuroimaging: localization of the time–frequency dynamics of cortical activity. Neuroimage40, 1686–1700 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuffin, B. N., Schomer, D. L., Ives, J. R. & Blume, H. Experimental tests of EEG source localization accuracy in spherical head models. Clin. Neurophysiol.112, 46–51 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs, M., Kastner, J., Wagner, M., Hawes, S. & Ebersole, J. S. A standardized boundary element method volume conductor model. Clin. Neurophysiol.113, 702–712 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baillet, S. Magnetoencephalography for brain electrophysiology and imaging. Nat. Neurosci.20, 327 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakami, S. & Okada, Y. Contributions of principal neocortical neurons to magnetoencephalography and electroencephalography signals. J. Physiol.575, 925–936 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meehan, C. E. et al. Differences in Rhythmic Neural Activity Supporting the Temporal and Spatial Cueing of Attention. Cerebral Cortex. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Coffey, E. B., Herholz, S. C., Chepesiuk, A. M., Baillet, S. & Zatorre, R. J. Cortical contributions to the auditory frequency-following response revealed by MEG. Nat. Commun.7, 1–11 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khanna, M. M. et al. Veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder exhibit altered emotional processing and attentional control during an emotional Stroop task. Psychological medicine. 47 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Hämäläinen, M., Hari, R., Ilmoniemi, R. J., Knuutila, J. & Lounasmaa, O. V. Magnetoencephalography—theory, instrumentation, and applications to noninvasive studies of the working human brain. Rev. Mod. Phys.65, 413 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baillet, S., Mosher, J. C. & Leahy, R. M. Electromagnetic brain mapping. IEEE Signal Process. Mag.18, 14–30 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasiotis, K., Clavagnier, S., Baillet, S. & Pack, C. C. High-resolution retinotopic maps estimated with magnetoencephalography. NeuroImage145, 107–117 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donoghue, T. et al. Parameterizing neural power spectra into periodic and aperiodic components. Nat. Neurosci.23, 1655–1665 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson, L. E., da Silva Castanheira, J. & Baillet, S. Time-resolved parameterization of aperiodic and periodic brain activity. Elife11, e77348 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moazami-Goudarzi, M., Sarnthein, J., Michels, L., Moukhtieva, R. & Jeanmonod, D. Enhanced frontal low and high frequency power and synchronization in the resting EEG of parkinsonian patients. Neuroimage41, 985–997 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meissner, W. et al. Deep brain stimulation in late stage Parkinson’s disease: a retrospective cost analysis in Germany. J. Neurol.252, 218–223 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kühn, A. A. et al. High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus suppresses oscillatory β activity in patients with Parkinson’s disease in parallel with improvement in motor performance. J. Neurosci.28, 6165–6173 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinrichs-Graham, E. et al. Neuromagnetic evidence of abnormal movement-related beta desynchronization in Parkinson’s disease. Cereb. cortex.24, 2669–2678 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiesman, A. I. et al. Adverse and compensatory neurophysiological slowing in Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 102538 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Wiesman, A. I. et al. Aberrant neurophysiological signaling associated with speech impairments in Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinson’s Dis.9, 61 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerra A., et al. Effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation on repetitive finger movements in healthy humans. Neural Plast. 2018 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Spooner, R. K. & Wilson, T. W. Spectral specificity of gamma-frequency transcranial alternating current stimulation over motor cortex during sequential movements. Cereb. Cortex.33, 5347–5360 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerra, A. et al. Driving motor cortex oscillations modulates bradykinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Brain145, 224–236 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerra, A. et al. Enhancing gamma oscillations restores primary motor cortex plasticity in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci.40, 4788–4796 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiesman, A. I. et al. Polarity-dependent modulation of multi-spectral neuronal activity by transcranial direct current stimulation. Cortex108, 222–233 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koshy, S. M. et al. Multielectrode transcranial electrical stimulation of the left and right prefrontal cortices differentially impacts verbal working memory neural circuitry. Cereb. Cortex.30, 2389–2400 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellwig, B. et al. Tremor-correlated cortical activity in essential tremor. Lancet357, 519–523 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andersen, L. M., Jerbi, K. & Dalal, S. S. Can EEG and MEG detect signals from the human cerebellum? NeuroImage215, 116817 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker, H. C. et al. Short latency activation of cortex by clinically effective thalamic brain stimulation for tremor. Mov. Disord.27, 1404–1412 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartmann, C. et al. Distinct cortical responses evoked by electrical stimulation of the thalamic ventral intermediate nucleus and of the subthalamic nucleus. NeuroImage: Clin.20, 1246–1254 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Louis, E. D., Ottman, R. & Allen Hauser, W. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Estimates of the prevalence of essential tremor throughout the world. Mov. Disord.13, 5–10 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Louis E. D. Treatment of medically refractory essential tremor. Mass Medical Soc; p. 792–793 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Lehéricy, S., Tijssen, M. A., Vidailhet, M., Kaji, R. & Meunier, S. The anatomical basis of dystonia: current view using neuroimaging. Mov. Disord.28, 944–957 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neychev, V. K., Fan, X., Mitev, V., Hess, E. J. & Jinnah, H. The basal ganglia and cerebellum interact in the expression of dystonic movement. Brain131, 2499–2509 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harmsen, I. E., Rowland, N. C., Wennberg, R. A. & Lozano, A. M. Characterizing the effects of deep brain stimulation with magnetoencephalography: a review. Brain Stimul.11, 481–491 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Litvak, V., Florin, E., Tamás, G., Groppa, S. & Muthuraman, M. EEG and MEG primers for tracking DBS network effects. Neuroimage224, 117447 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown, P. Oscillatory nature of human basal ganglia activity: relationship to the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.18, 357–363 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levy, R. et al. Dependence of subthalamic nucleus oscillations on movement and dopamine in Parkinson’s disease. Brain125, 1196–1209 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Little, S. & Brown, P. The functional role of beta oscillations in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord.20, S44–S48 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinberger, M. et al. Beta oscillatory activity in the subthalamic nucleus and its relation to dopaminergic response in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurophysiol.96, 3248–3256 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asadi A., Madadi Asl M., Vahabie A.-H., Valizadeh A. The origin of abnormal beta oscillations in the Parkinsonian corticobasal ganglia circuits. Parkinson’s Dis. 2022 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Bočková, M. et al. Involvement of the subthalamic nucleus and globus pallidus internus in attention. J. Neural Transm.118, 1235–1245 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volkmann, J. et al. Central motor loop oscillations in Parkinsonian resting tremor revealed magnetoencephalography. Neurology46, 1359–1359 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown, P. et al. Dopamine dependency of oscillations between subthalamic nucleus and pallidum in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci.21, 1033–1038 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams, D. et al. Dopamine-dependent changes in the functional connectivity between basal ganglia and cerebral cortex in humans. Brain125, 1558–1569 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piña-Fuentes, D. et al. Direct comparison of oscillatory activity in the motor system of Parkinson’s disease and dystonia: a review of the literature and meta-analysis. Clin. Neurophysiol.130, 917–924 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neumann, W. J. et al. A localized pallidal physiomarker in cervical dystonia. Ann. Neurol.82, 912–924 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piña-Fuentes, D. et al. The characteristics of pallidal low-frequency and beta bursts could help implementing adaptive brain stimulation in the parkinsonian and dystonic internal globus pallidus. Neurobiol. Dis.121, 47–57 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barow, E. et al. Deep brain stimulation suppresses pallidal low frequency activity in patients with phasic dystonic movements. Brain137, 3012–3024 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piña-Fuentes, D. et al. Adaptive deep brain stimulation as advanced Parkinson’s disease treatment (ADAPT study): protocol for a pseudo-randomised clinical study. BMJ Open.9, e029652 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piña-Fuentes, D. et al. Low-frequency oscillation suppression in dystonia: implications for adaptive deep brain stimulation. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord.79, 105–109 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moran, A., Bar-Gad, I., Bergman, H. & Israel, Z. Real-time refinement of subthalamic nucleus targeting using Bayesian decision-making on the root mean square measure. Mov. Disord.21, 1425–1431 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zaidel, A., Spivak, A., Shpigelman, L., Bergman, H. & Israel, Z. Delimiting subterritories of the human subthalamic nucleus by means of microelectrode recordings and a Hidden Markov Model. Mov. Disord.24, 1785–1793 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raz, A., Eimerl, D., Zaidel, A., Bergman, H. & Israel, Z. Propofol decreases neuronal population spiking activity in the subthalamic nucleus of Parkinsonian patients. Anesth. Analges.111, 1285–1289 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koirala, N. et al. Mapping of subthalamic nucleus using microelectrode recordings during deep brain stimulation. Sci. Rep.10, 19241 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valsky, D. et al. Real-time machine learning classification of pallidal borders during deep brain stimulation surgery. J. Neural Eng.17, 016021 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reddy, S., Fenoy, A., Furr-Stimming, E., Schiess, M. & Mehanna, R. Does the use of intraoperative microelectrode recording influence the final location of lead implants in the ventral intermediate nucleus for deep brain stimulation? Cerebellum16, 421–426 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kundu, B., Brock, A. A., Thompson, J. A. & Rolston, J. D. Microelectrode recording in neurosurgical patients. Stereotact. Funct. Neurosurg.: Principles Appl. 93–106. (2020).

- 61.Hari, R. et al. IFCN-endorsed practical guidelines for clinical magnetoencephalography (MEG). Clin. Neurophysiol.129, 1720–1747 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ahlfors, S. P., Han, J., Belliveau, J. W. & Hämäläinen, M. S. Sensitivity of MEG and EEG to source orientation. Brain Topogr.23, 227–232 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Muthuraman, M. et al. Beamformer source analysis and connectivity on concurrent EEG and MEG data during voluntary movements. PloS One9, e91441 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharon, D., Hämäläinen, M. S., Tootell, R. B., Halgren, E. & Belliveau, J. W. The advantage of combining MEG and EEG: comparison to fMRI in focally stimulated visual cortex. Neuroimage36, 1225–1235 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lemaire, N. et al. Effects of dopamine depletion on LFP oscillations in striatum are task-and learning-dependent and selectively reversed by L-DOPA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.109, 18126–18131 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berke, J. D., Okatan, M., Skurski, J. & Eichenbaum, H. B. Oscillatory entrainment of striatal neurons in freely moving rats. Neuron43, 883–896 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Courtemanche, R., Fujii, N. & Graybiel, A. M. Synchronous, focally modulated β-band oscillations characterize local field potential activity in the striatum of awake behaving monkeys. J. Neurosci.23, 11741–11752 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jech, R. et al. Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus affects resting EEG and visual evoked potentials in Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol.117, 1017–1028 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cao, C. et al. Resting state cortical oscillations of patients with Parkinson disease and with and without subthalamic deep brain stimulation: a magnetoencephalography study. J. Clin. Neurophysiol.32, 109–118 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cao, C.-Y. et al. Modulations on cortical oscillations by subthalamic deep brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson disease: a MEG study. Neurosci. Lett.636, 95–100 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Averna, A. et al. Pallidal and cortical oscillations in freely moving patients with dystonia. Neuromodul. Techno. Neural Interface. (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Kühn, A. A., Kupsch, A., Schneider, G. H. & Brown, P. Reduction in subthalamic 8–35 Hz oscillatory activity correlates with clinical improvement in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci.23, 1956–1960 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oswal, A. et al. Deep brain stimulation modulates synchrony within spatially and spectrally distinct resting state networks in Parkinson’s disease. Brain139, 1482–1496 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.De Hemptinne, C. et al. Therapeutic deep brain stimulation reduces cortical phase-amplitude coupling in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Neurosci.18, 779–786 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fogelson, N. et al. Frequency dependent effects of subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett.382, 5–9 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Malekmohammadi, M. et al. Pallidal stimulation in Parkinson disease differentially modulates local and network β activity. J. Neural Eng.15, 056016 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yokochi, F. et al. Resting-state pallidal-cortical oscillatory couplings in patients with predominant phasic and tonic dystonia. Front. Neurol.9, 375 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perlmutter, J. S. & Mink, J. W. Deep brain stimulation. Annu Rev. Neurosci.29, 229–257 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dostrovsky, J. O. & Lozano, A. M. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. Mov. Disord.: Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc.17, S63–S68 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hollunder, B. et al. Toward personalized medicine in connectomic deep brain stimulation. Prog. Neurobiol.210, 102211 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hirschmann, J. et al. Distinct oscillatory STN-cortical loops revealed by simultaneous MEG and local field potential recordings in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neuroimage55, 1159–1168 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Litvak, V. et al. Resting oscillatory cortico-subthalamic connectivity in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Brain134, 359–74 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jenkinson, N. & Brown, P. New insights into the relationship between dopamine, beta oscillations and motor function. Trends Neurosci.34, 611–618 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eusebio, A. et al. Deep brain stimulation can suppress pathological synchronisation in parkinsonian patients. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry82, 569–573 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hirschmann, J., Steina, A., Vesper, J., Florin, E. & Schnitzler, A. Neuronal oscillations predict deep brain stimulation outcome in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Stimulation. (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.Little, S. et al. Adaptive deep brain stimulation in advanced Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol.74, 449–457 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herz, D. M. et al. Mechanisms underlying decision-making as revealed by deep-brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Biol.28, 1169–1178. e6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Quinn, E. J. et al. Beta oscillations in freely moving Parkinson’s subjects are attenuated during deep brain stimulation. Mov. Disord.30, 1750–1758 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Whitmer, D. et al. High frequency deep brain stimulation attenuates subthalamic and cortical rhythms in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Hum. Neurosci.6, 155 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wiest, C. et al. Local field potential activity dynamics in response to deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis.143, 105019 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Herrington, T. M., Cheng, J. J. & Eskandar, E. N. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. J. Neurophysiol.115, 19–38 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.van Rheede, J. J. et al. Diurnal modulation of subthalamic beta oscillatory power in Parkinson’s disease patients during deep brain stimulation. npj Parkinson’s Dis.8, 88 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mizrahi-Kliger, A. D., Kaplan, A., Israel, Z., Deffains, M. & Bergman, H. Basal ganglia beta oscillations during sleep underlie Parkinsonian insomnia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.117, 17359–17368 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bjerknes, S., Skogseid, I. M., Hauge, T. J., Dietrichs, E. & Toft, M. Subthalamic deep brain stimulation improves sleep and excessive sweating in Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinson’s Dis.6, 29 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Anjum, M. F. et al. Multi-night cortico-basal recordings reveal mechanisms of NREM slow-wave suppression and spontaneous awakenings in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun.15, 1793 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johnson, K. A. et al. Globus pallidus internus deep brain stimulation evokes resonant neural activity in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Commun.5, fcad025 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sinclair, N. C. et al. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation evokes resonant neural activity. Ann. Neurol.83, 1027–1031 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wiest, C. et al. Evoked resonant neural activity in subthalamic local field potentials reflects basal ganglia network dynamics. Neurobiol. Dis.178, 106019 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Neumann, W.-J., Steiner, L. A. & Milosevic, L. Neurophysiological mechanisms of deep brain stimulation across spatiotemporal resolutions. Brain146, 4456–4468 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sermon, J. J., Wiest, C., Tan, H., Denison, T. & Duchet, B. Evoked resonant neural activity long-term dynamics can be reproduced by a computational model with vesicle depletion. bioRxiv. 2024.02. 25.582012 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 101.Wiest, C. et al. Subthalamic Nucleus Stimulation–Induced Local Field Potential Changes in Dystonia. Mov. Disord.38, 423–434 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Horn, A., Neumann, W. J., Degen, K., Schneider, G. H. & Kühn, A. A. Toward an electrophysiological “sweet spot” for deep brain stimulation in the subthalamic nucleus. Hum. Brain Mapp.38, 3377–3390 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schmidt, S. L., Brocker, D. T., Swan, B. D., Turner, D. A. & Grill, W. M. Evoked potentials reveal neural circuits engaged by human deep brain stimulation. Brain Stimul.13, 1706–1718 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Awad, M. Z. et al. Subcortical short-term plasticity elicited by deep brain stimulation. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol.8, 1010–1023 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sinclair, N. C. et al. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease modulates high-frequency evoked and spontaneous neural activity. Neurobiol. Dis.130, 104522 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lee, W.-L. et al. Can brain signals and anatomy refine contact choice for deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease? J. Neurol., Neurosurg. Psychiatry93, 1338–1341 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sinclair, N. C. et al. Electrically evoked and spontaneous neural activity in the subthalamic nucleus under general anesthesia. J. Neurosurg.137, 449–458 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wiest, C. et al. Finely-tuned gamma oscillations: Spectral characteristics and links to dyskinesia. Exp. Neurol.351, 113999 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Swann, N. C. et al. Gamma oscillations in the hyperkinetic state detected with chronic human brain recordings in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci.36, 6445–6458 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gilron, R. et al. Long-term wireless streaming of neural recordings for circuit discovery and adaptive stimulation in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Biotechnol.39, 1078–1085 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wiest, C. et al. Subthalamic deep brain stimulation induces finely-tuned gamma oscillations in the absence of levodopa. Neurobiol. Dis.152, 105287 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sermon, J. J. et al. Sub-harmonic entrainment of cortical gamma oscillations to deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: Model based predictions and validation in three human subjects. Brain Stimul.16, 1412–1424 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gao, R., Peterson, E. J. & Voytek, B. Inferring synaptic excitation/inhibition balance from field potentials. Neuroimage158, 70–78 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Waschke, L. et al. Modality-specific tracking of attention and sensory statistics in the human electrophysiological spectral exponent. Elife10, e70068 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lendner, J. D. et al. An electrophysiological marker of arousal level in humans. elife9, e55092 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wiest, C. et al. The aperiodic exponent of subthalamic field potentials reflects excitation/inhibition balance in Parkinsonism. Elife12, e82467 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Arlotti, M., Rosa, M., Marceglia, S., Barbieri, S. & Priori, A. The adaptive deep brain stimulation challenge. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord.28, 12–17 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Neumann, W. J., Gilron, R., Little, S. & Tinkhauser, G. Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation: From Experimental Evidence Toward Practical Implementation. Movement disorders., (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 119.Little, S. & Brown, P. What brain signals are suitable for feedback control of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.1265, 9–24 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Khawaldeh, S. et al. Balance between competing spectral states in subthalamic nucleus is linked to motor impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Brain145, 237–250 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Priori, A. et al. Rhythm-specific pharmacological modulation of subthalamic activity in Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol.189, 369–379 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tinkhauser, G. et al. Beta burst coupling across the motor circuit in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis.117, 217–225 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tinkhauser, G. et al. The modulatory effect of adaptive deep brain stimulation on beta bursts in Parkinson’s disease. Brain140, 1053–1067 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hirschmann, J., Schoffelen, J.-M., Schnitzler, A. & Van Gerven, M. Parkinsonian rest tremor can be detected accurately based on neuronal oscillations recorded from the subthalamic nucleus. Clin. Neurophysiol.128, 2029–2036 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Shah, S. A., Tinkhauser, G., Chen, C. C., Little, S. & Brown, P. Parkinsonian tremor detection from subthalamic nucleus local field potentials for closed-loop deep brain stimulation. IEEE; 2320–2324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 126.Ricciardi, L. et al. Neurophysiological correlates of trait impulsivity in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.36, 2126–2135 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.de Hemptinne, C. et al. Prefrontal physiomarkers of anxiety and depression in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci.15, 748165 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Beudel, M., Cagnan, H. & Little, S. Adaptive brain stimulation for movement disorders. Curr. Concepts Mov. Disord. Manag.33, 230–242 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Brambilla, C. et al. Combined use of EMG and EEG techniques for neuromotor assessment in rehabilitative applications: A systematic review. Sensors21, 7014 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Graupe, D., Basu, I., Tuninetti, D., Vannemreddy, P. & Slavin, K. V. Adaptively controlling deep brain stimulation in essential tremor patient via surface electromyography. Neurol. Res.32, 899–904 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yamamoto, T. et al. On-demand control system for deep brain stimulation for treatment of intention tremor. Neuromodulation: Technol. Neural Interface16, 230–235 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Brittain, J.-S., Probert-Smith, P., Aziz, T. Z. & Brown, P. Tremor suppression by rhythmic transcranial current stimulation. Curr. Biol.23, 436–440 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Cagnan, H. et al. The nature of tremor circuits in parkinsonian and essential tremor. Brain137, 3223–3234 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information for Review Paper: Key Concepts in Neurophysiological Data Analysis for Parkinson’s Disease

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.