Abstract

Urticarial vasculitis (UV) is a rare and difficult-to-treat, small-vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis presenting with recurrent long-lasting wheals. So far, no guidelines and treatment algorithms exist that could help clinicians with the management of UV. In this review, we describe evidence on systemic treatments used for UV and propose a clinical decision-making algorithm for UV management based on the Urticarial Vasculitis Activity Score assessed for 7 days (UVAS7). Patients with occasional UV-like urticarial lesions and patients with UV with skin-limited manifestations and/or mild arthralgia/malaise (total UVAS7 ≤7 of 70) can be initially treated using the step-wise algorithm for chronic urticaria including second-generation H1-antihistamines, omalizumab, and cyclosporine A. Patients with UV with more severe symptoms (UVAS7 >7), especially those with hypocomplementemic UV, may require a multidisciplinary approach, particularly if underlying diseases, for example, systemic lupus erythematosus, cancer, or infection, are present. Immunomodulatory therapy is based on clinical signs and symptoms, and the drug availability and safety profile, and includes systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, hydroxychloroquine, anti-interleukin-1 agents, and other therapies. The level of evidence for all UV treatments is low. Prospective studies with current and novel drugs are needed and could provide further insights into UV pathogenesis and treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40257-024-00902-y.

Key Points

| Urticarial vasculitis (UV) is a potentially severe and difficult-to-treat condition presenting with long-lasting wheals and often systemic symptoms including fever and arthralgia. Chronic spontaneous urticaria is the main differential diagnosis. |

| We propose a treatment algorithm for patients with UV based on the Urticarial Vasculitis Activity Score assessed for 7 days (UVAS7). |

| Patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria with occasional UV-like urticarial lesions and patients with UV with skin-limited manifestations and/or mild arthralgia/malaise (total UVAS7 ≤7 of 70) can be initially treated using the step-wise algorithm for chronic urticaria including second-generation antihistamines, omalizumab, and cyclosporine A (all off-label in UV). |

| In patients with UV with more severe symptoms (UVAS7 >7), the therapy may require a multidisciplinary approach addressing underlying diseases and applying immunosuppressive therapy including systemic corticosteroids. |

Introduction

Urticarial vasculitis (UV) is a small-vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis presenting with recurrent long-lasting wheals. UV is rare, with an estimated incidence of 0.5 cases per 100,000 person-years [1]. UV is classified into two variants: normocomplementemic (NUV) and hypocomplementemic (HUV). HUV is severe, difficult to treat, often linked to an underlying disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and with systemic symptoms such as fever and arthralgia, whereas NUV is more common and usually limited to the skin. Most UV cases are chronic (>6 weeks), with a median disease duration of 1.5–4.0 years [2]. Most patients with UV report a considerable decrease in quality of life, which is associated with a long disease duration, high symptom burden, and high need for therapy [3]. Disease-specific patient-reported outcome measurements to assess disease control and impact are not yet available. Urticarial vasculitis activity can be measured with the Urticarial Vasculitis Activity Score (UVAS, Table 1) [4], which assesses five key symptoms of UV: wheals, burning or pruritus, residual skin pigmentation, joint pain, and general symptoms such as fatigue or fever.

Table 1.

Urticarial Vasculitis Activity Score (UVAS). Please rate the severity of the following symptoms on a scale from 0 to 10 over the last 24 h

| No symptoms 0 | Very severe symptoms 10 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Score |

| Wheals | ||||||||||||

| Burning, pain, itching of the skin | ||||||||||||

| Residual pigmentation (brownish spots, residue after the rash has subsided) | ||||||||||||

| Joint pain | ||||||||||||

| General symptoms (tiredness, fatigue, chills, fever) | ||||||||||||

| Sum | ||||||||||||

The UVAS was formerly developed as a modification of an instrument previously validated for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome; however, it has not been validated yet to assess UV severity [4]. To calculate daily UVAS, the severity of the five key symptoms is assessed based on their occurrence over the past 24 hours on a scale from 0 to 10 (0 meaning a symptom did not occur and 10 being the strongest possible presentation of a symptom). The individual scores are added and divided by 5 to yield a UVAS score between 0 and 10. To calculate UVAS7, the sum of daily UVAS scores of 7 consecutive days should be taken with the total score range between 0 and 70

A typical patient with UV is a middle-aged woman (82%) with recurrent wheals that appear without any specific or definite external stimuli [5]. Therefore, the main differential diagnosis of UV is chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU, Table 2). In most cases, a clear distinction can be made between UV and CSU based on wheal duration, presence of systemic symptoms, and residual skin signs. In CSU, wheals are transient, lasting from minutes to a few hours. In contrast to the itchy wheals of CSU, which disappear without residual bruising or hyperpigmentation, the wheals associated with UV are commonly associated with burning and pain of the skin and heal with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. UV is associated with systemic symptoms, particularly in the context of HUV, which typically do not occur in CSU. However, an overlap and a continuum between both diseases, UV and CSU, has been observed in individual patients [5, 6]. The occurrence of chronic recurrent wheals and systemic symptoms is also typical for Schnitzler syndrome and cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, i.e., rare urticarial autoinflammatory syndromes, which are further differential diagnoses of UV. Last, wheals can also appear in patients with other types of vasculitis, including Henoch–Schönlein purpura, acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy, cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Table 1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]) [7–9].

Table 2.

Comparison of the characteristics of chronic spontaneous urticaria vs urticarial vasculitis.

| Characteristics | Chronic spontaneous urticaria | Urticarial vasculitis |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristics [6] | ||

| Gender | Female predominance | Female predominance |

| Typical age at onset of disease | Any age, in most cases >30 years of age | Midlife (~45th year of life) |

| Duration of disease | Mean/median: ~1–4 years | Mean/median: ~1–4 years |

| Genetic predisposition | Possible for patients with autoimmune CSU | Unknown |

| Skin symptoms | Wheals and/or angioedema | Wheals with/without angioedema |

| Duration of individual lesions | Transient, minutes to hours | >24 hours in most cases |

| Accompanying symptoms on the skin | Itch, often strong | Rarely itching, but burning, pain, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation |

| Occurrence of angioedema | Possible (in ~40–50% patients with wheals) | Occurrence possible |

| Systemic complaints | Rare | Spectrum: joint pain, fever, muscle pain, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal involvement |

| Investigations [6] | ||

| Inflammatory markers | CRP may be slightly elevated, usually unremarkable | CRP, ESR elevated; In hypocomplementemic form: C1q, C3 and/or C4 decreased, C1q antibodies |

| Histology of the lesional skin | Dermal edema and sparse mixed-cell perivascular infiltrate | Findings of leukocytoclastic vasculitisa |

| Response to treatment | ||

| Second generation H1-antihistamines | Complete disease control is seen in about 8% of patients with CSU [70] | Rarely effective |

| Omalizumab | At least 70% of patients with antihistamine-refractory CSU are partial or complete responders [71] | Can be effective in some patients |

This is a modified version of the table previously published in Allergologie Select [69], used with the kind permission of Dustri-Verlag

C1q complement component C1q, C3 complement C3, C4 complement C4, CRP C-reactive protein, CSU chronic spontaneous urticaria, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate

aLeukocytoclasia (present in 76% of urticarial vasculitis vs 3.9% of CSU samples), erythrocyte extravasation (41.3% vs 2.0%), and fibrin deposits (27.9% vs 9.7%) [68]

Management of patients with UV is often challenging for treating physicians. Its etiology varies widely between patients, with up to 30% of patients with UV having an underlying disease including SLE, cancer, and chronic infection [2]. The pathogenesis of UV is not yet fully understood and remains a subject of academic discussion [10]. If identified, triggers such as drugs should be avoided, and known comorbidities should be treated to improve UV symptoms [2]. Because of unpredictable symptom occurrence and extracutaneous involvement, topical therapy is rarely effective. Oral antihistamines seldom suffice to manage symptoms effectively, especially in patients with systemic manifestations of UV. Such patients often respond well to systemic glucocorticosteroids (SGC) but frequently relapse when doses are tapered or treatment is discontinued. Many patients require three or more different drugs in combination or subsequently to manage their illness [2]. So far, guidelines and treatment algorithms to help with the management of UV do not exist. In this review, we describe the evidence on different systemic treatments used for UV with the focus on clinical aspects, and we propose a clinical decision-making algorithm for its management.

Approach to the Literature

Physicians with clinical experience in the management of patients with UV and/or CSU, all coauthors of this publication, were invited to contribute to this review. We compiled a comprehensive list of medications used in UV treatment based on the physicians’ expertise, a literature search in PubMed using the terms “urticarial vasculitis” and “treatment,” and data from a recent systematic review [2]. Each coauthor of this publication was asked to choose one or several medications from the list, and to perform an additional search with search terms “[Selected Drug]” and “urticarial vasculitis” to find relevant papers. Preference was given to clinical trials, randomized controlled trials, and prospective or retrospective studies with larger patient cohorts. Review articles were excluded. A standardized summary table was used to extract relevant data from each study. Based on these data, coauthors prepared a summary of each medication, focusing on the strength of evidence in UV, including the number of patients treated, the number of patients who benefited, and the results of the most poignant research. Furthermore, the summaries addressed the efficacy of the medications regarding skin symptoms (itch, wheals, burning, pain) and systemic symptoms (fever, arthralgia, abdominal pain), combinations with other drugs, safety issues, and the advantages, disadvantages, and limitations in UV treatment. For each drug, a minimum of ten selected papers were included where available (Table 2 of the ESM).

Drug Treatment for UV

In total, 135 studies were selected for inclusion in this review (Table 2 of the ESM). The evidence for all drugs was generally low and limited to retrospective studies, case reports, and case series. The most robust evidence was available for H1-antihistamines, omalizumab, and various immunomodulators (Table 3, Tables 3–17 of the ESM). Specifically, the review included 23 studies on antihistamines, with most focusing on second-generation H1-antihistamines, and 25 studies on omalizumab, reflecting its growing role in UV management. Systemic glucocorticosteroids stood out as a treatment with multiple single-treatment studies featuring larger patient cohorts. Other drugs, such as dapsone (13 studies) and anti-CD20 antibody rituximab (ten studies), were also well represented, highlighting their importance in managing more severe and refractory cases.

Table 3.

Summary of the use of major drugs for systemic therapy in UV

| Drug | Dose used in UV | Administration | Beneficial for skin symptoms | Beneficial for systemic symptoms | Adverse events | Comments | Table in ESM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antihistamines | |||||||

| Second-generation H1-antihistamines | As needed, up to four times the recommended dose | PO | Yes, if itch is present | No evidence | Generally safe. Possible adverse events at higher doses include drowsiness and impaired kidney function | Second-generation H1-antihistamines may be beneficial to treat pruritus symptomatically but show no clear benefits in treating UV | 3 |

| Monoclonal antibodies | |||||||

| Omalizumab (anti-IgE) | 300 mg/4 weeks | SC | Yes | Unclear | Generally safe | Can be effective in NUV patients with mild disease, with predominant cutaneous symptoms | 4 |

| Canakinumab and anakinra (anti-IL-1β/IL-1R) |

Canakinumab: 300 mg/8 weeks Anakinra: 100 mg/day |

SC | Yes | Yes, improvement in joint and gastrointestinal involvement reported | Generally safe. Possible adverse events include headaches, infections, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia | Relapses are frequent when treatment is suspended | 5 |

| Rituximab (anti-CD20) | 375 mg to 1g | IV | Yes | Yes, improvement in renal involvement reported | Possible adverse events include fever, infections, and cytopenia | Relapses are frequent when treatment is suspended | 6 |

| Immunomodulators | |||||||

| Systemic glucocorticosteroids | 0.5–1 mg/kg/day | PO | Yes | Yes | Not suitable for long-term treatment because of an increased risk of adverse events including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, neuropsychiatric conditions, and obesity | Beneficial for severe therapy-refractory cases with systemic symptoms. Taper dose as soon as possible to prevent long-term adverse effects | 7 |

| Cyclosporine A | 2.5–5 mg/kg/day | PO | Yes | Partially | Most common adverse events are elevation of serum creatinine levels, gastrointestinal symptoms, hypertension, paresthesia, headache, hirsutism, and mild infection | Dose was usually divided and administered twice daily | 8 |

| Methotrexate | 5–20 mg/1 week | PO/SC | Yes | Yes | Well tolerated but need for regular blood tests; fatigue and hair thinning possible | Can be used as a corticosteroid-sparing agent | 9 |

| Azathioprine | 100 mg/day | PO | Yes | Partially, showed beneficial effects in in cases with renal or lung involvement | Need for vigilant patient monitoring: leukopenia, hepatotoxicity, and nephritis reported | Adjust doses based on thiopurine methyltransferase levels | 10 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 0.8 –2 mg/kg/day | PO/IV | Yes | Yes | Potentially severe, e.g., myelosuppression, risk for bladder and gonadal toxicity, and cytopenia | Alternatively, 500–1000 mg monthly pulse therapy has been reported | 11 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 0.5–3 g/day | PO | Yes | Yes | Possible adverse events: GI problems, anemia, thrombocytopenia | Frequently used in combination with SGC as a corticosteroid-sparing agent | 12 |

| Dapsone | 100 mg | PO | Yes | Possible improvements in arthralgia, fever, fatigue, and gastrointestinal involvement | Frequent when used at doses 100 mg/day or more already after several weeks of use | Often administered in conjunction with SGC, antihistamines, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine | 13 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 400 mg/day | PO | Often | Improvements in symptoms affecting the joints, lungs, and eyes | Generally safe. Possible adverse events include retinopathy, elevated liver-enzymes, GI problems, photosensitivity | Initially often combined with prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/day) with prednisolone being tapered | 14 |

| IVIG | 1–2 g/kg/4 weeks | IV | Yes | Unclear | Possible adverse events include fever, headaches, fatigue, GI problems | Potentially more successful in patients with concomitant autoimmune disease | 15 |

| Other treatments | |||||||

| NSAIDs | As needed, up to the maximum recommended dose | Differs, usually PO | Unclear | Unclear | Possible adverse events: GI ulcers, cardiovascular events, hypertension, acute renal failure | NSAIDs may be used as a supplementary therapy to manage symptoms of disease activity but have not been assessed as single treatments for UV | 16 |

| Colchicine | 1.0–1.2 mg/day usually divided and administered three times daily | PO | Sometimes | Sometimes, showed beneficial effects in cases with joint or gastrointestinal involvement | Possible adverse events: GI problems, myelosuppression, neuropathy | Only effective in few patients and best used in conjunction with SGCs | 17 |

This table summarizes data from the reviewed publications on each UV treatment. Detailed information for each individual publication can be found in Tables 3–18 of the ESM indicated in the rightmost column. Results for drugs with limited or no efficacy in the treatment of UV have been excluded from this table and are available in Table 18 of the ESM

anti-IgE anti-immunoglobulin E, anti-IL-1β/IL-1R anti-interleukin-1 beta/interleukin-1 receptor, CD20 surface antigen found on B cells, GI gastrointestinal, IgE immunoglobulin E, IV intravenous, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin, NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-Inflammatory drugs, NUV normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis, PO per os (oral), SC subcutaneous, SGC systemic glucocorticosteroids, UV urticarial vasculitis

Second-Generation H1-Antihistamines

Overall, 141 patients with UV (77 of whom had NUV) from 23 publications received different second-generation anti-histamines (sgAHs) at a standard dose or up-titrated up to four times the standard dose (n = 5). Two patients received concomitant ranitidine (an H2-antihistamine), whereas eight patients received an additional first-generation H1-antihistamine (hydroxyzine, up to 50 mg/day). The duration of treatment varied from 10 days to 8 years. Resolution of skin lesions with the isolated use of sgAHs occurred in 3.5% of patients (n = 5/141), and skin lesions improved in 6.4% (n = 9/141) of patients with concomitant use of oral prednisolone or colchicine. SgAHs, used at standard or higher than the standard dose, failed to effectively improve skin lesions in the remaining 90.1% patients (n = 128/141). These patients commonly switched to the use of SGC, immunomodulators, or omalizumab for their UV. SgAHs have not been reported to have any effect on extracutaneous symptoms, and no treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were reported (Table 3 of the ESM).

In line with our recent systematic review, we found that sgAHs are of limited efficacy in UV [2]. However, given their safety profile, sgAHs can be tried in patients with UV with mild symptoms and pruritus, those who have signs of a CSU/UV overlap, and possibly also in patients with more severe disease as an adjunct therapy, along with systemic immunomodulators or biologics. SgAHs are generally safe, even as a long-term treatment; however, some AEs are possible, such as tiredness and somnolence, especially at high doses [11]. Elderly patients, especially those with renal, hepatic and/or cardiac disorders may be at risk while taking high doses of some sgAHs. Cetirizine and loratadine are considered to be safe in pregnant and breastfeeding women [12, 13].

Monoclonal Antibodies

Among biologic therapies, the most substantial evidence for treating UV is available for omalizumab, a humanized recombinant anti-immunoglobulin E (IgE) monoclonal antibody, and rituximab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the B-lymphocyte antigen CD20. Additionally, there is evidence for the use of canakinumab, an interleukin (IL)-1β antagonist, and anakinra, an IL-1-receptor antagonist.

Omalizumab (Anti-IgE)

Between 2009 and 2023, omalizumab was administered to 108 patients with UV, primarily those with NUV (n = 52/108), across 25 studies, most of which were case reports (Table 4 of the ESM). Cutaneous symptoms improved in 76% of patients (n = 82/108), many of whom achieved full clinical remission. Extracutaneous symptoms, such as arthralgia or abdominal pain, improved in 40% of patients (n = 10/25). Non-serious AEs, including fever and laboratory abnormalities, were reported in 12 patients during or after the treatment.

Omalizumab is approved for the treatment of sgAH-refractory CSU as the second-line therapy, administered at a dose of 300 mg by subcutaneous injection every 4 weeks in adults and adolescents 12 years of age or older [14]. Dosing in CSU is independent of the serum IgE level or body weight, although low and high levels of total IgE have been described as a marker of slow/non-response and fast/good response to omalizumab, respectively [15]. In studies of urticaria and asthma, omalizumab was well tolerated, even with long-term use [16, 17]. It is also considered safe in pregnancy, in younger children, and in elderly individuals, although it is not licensed for these subpopulations of patients with CSU [18].

Canakinumab and Anakinra (Anti-IL-1)

Krause et al. used a single dose of canakinumab (300 mg subcutaneously) in an open-label study in ten patients with UV (9 NUV and 1 HUV). Cutaneous and systemic symptoms, as well as laboratory markers of inflammation, improved within 15 days in 70% of patients (n = 7/10), followed by relapse in one patient after 4 weeks [4]. In a French multicenter study, six patients with UV (two NUV and four HUV) with associated skin, gastrointestinal, and articular symptoms were treated with anakinra (with one case later switching to canakinumab). Five patients experienced a complete remission and one showed a partial improvement of cutaneous and systemic symptoms, but at least four relapsed upon drug discontinuation [19]. In a case report of NUV, presenting for more than 3 years with wheals, fever, and elevated C-reactive protein, the patient responded to anakinra, further supporting the potential of IL-1 inhibition in UV [20] (Table 5 of the ESM).

Rituximab (Anti-CD20)

In two larger case series, rituximab, an anti-CD20 therapy, demonstrated a complete and fast resolution of skin and systemic symptoms, as well as laboratory parameters in 71% of patients (n = 10/14) who had previously not responded to treatment with SGC and other conventional immunosuppressants [21, 22]. In every one of the reviewed publications, all patients treated with rituximab (n = 21) showed improvements in their skin symptoms (Table 6 of the ESM). All patients with systemic involvement who received rituximab also showed improvement in those symptoms (n = 20), including those affecting the kidneys, joints, lungs, eyes, and gastrointestinal tract. Although serious adverse reactions to rituximab, including allergic reactions and severe cytopenia, have been reported in the literature [23], none of the publications reviewed in this study reported any AEs following rituximab therapy.

In summary, omalizumab can be used as an off-label treatment for UV, especially in patients with NUV and those with mild disease, presenting with CSU-like symptoms, including itchy wheals, and minimal or no fever, arthralgia, abdominal pain, or other systemic symptoms. Similar to CSU treatment, omalizumab at higher doses, shorter intervals, or both can be considered in patients with UV with an insufficient response to the licensed dose within 3–6 months [24]. Anti-IL-1 and anti-CD20 therapies can be considered in refractory UV cases but their use is limited by high costs and available evidence.

Immunomodulators

Systemic Glucocorticosteroids

Systemic glucocorticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory drugs frequently used to manage various inflammatory dermatologic conditions, including UV. They work by suppressing inflammation and modulating immune responses, thereby alleviating symptoms and improving patient outcomes. In seven studies involving 287 patients with UV treated with SGC from 2007 to 2023, a common dosage regimen was 0.5–1 mg/kg per day (Table 7 of the ESM). Treatment typically began with daily administration for 1–2 weeks, followed by gradual tapering of the dosage. Significant improvements in skin symptoms were observed across all studies that ranged from 44.8% (n = 39/87 [3]) to 100% (n = 20 [25]) of patients. Likewise, improvement in extracutaneous symptoms was noted in 32% (n = 57 [21]) to 93.3% (n = 56/60 [5]) of cases. These findings underscore their role as a cornerstone in the therapeutic armamentarium for this condition. However, because of potential side effects such as hyperglycemia, arterial hypertension, adrenal suppression, and osteoporosis, long-term use of SGCs should be avoided [26].

Combined Immunosuppressive Treatment

Other immunosuppressive medications were used in several patients with difficult-to-treat UV including those with underlying conditions such as SLE, often in combination with SGC. Cyclosporine A, methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) are typically employed as second-line therapies for moderate-to-severe cutaneous vasculitis [27, 28]. The combined use of SGC and immunosuppressants has been shown to improve efficacy in controlling both cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations of UV compared with SGC alone, although response rates and treatment duration may vary among different agents [28]. One study reported response rates of 74% for cutaneous symptoms and 63% for immunologic responses, defined as normalization of C3 and/or C4 levels, in cases of refractory and/or relapsing disease when SGCs are combined with conventional immunosuppressive agents [21]. Furthermore, supplementary immunosuppressive therapy has been beneficial in reducing SGC dosages.

Cyclosporine A

In three case reports, female patients with UV received oral cyclosporine A in daily doses that ranged from 2.5 to 5.0 mg/kg (Table 8 of the ESM). The treatment improved urticarial lesions in all cases (n = 3/3), and alleviated arthralgias in one case. In a meta-analysis and systematic review of CSU studies, cyclosporine A was effective in 54–73% of patients at doses of 1–5 mg/kg/day [29]. These findings suggest that cyclosporine A is a viable treatment option, particularly for managing the skin symptoms of UV.

Methotrexate

In three studies including 15 patients, methotrexate at doses of 5–20 mg weekly was effective in achieving skin remission (n = 13/15) and long-lasting complete disease remission as well as reducing the SGC dose [27, 28] (Table 9 of the ESM). Methotrexate is generally reported to be a well-tolerated medication; [30, 31] however, paradoxical exacerbation of UV symptoms [27, 32], fatigue, hair thinning, hepatotoxicity, myelosuppression with pancytopenia, and gastrointestinal symptoms is possible[2].

Azathioprine

Azathioprine was used in refractory UV cases with doses adjusted based on thiopurine methyltransferase levels. Azathioprine allowed a SGC dosage reduction and resolution of cutaneous lesions [27, 33, 34] (Table 10 of the ESM). Two case reports suggested possible benefits in resolving lung and kidney impairment, respectively [33, 35]. In a larger case series of 18 patients, azathioprine improved cutaneous and extracutaneous symptoms in 83% (n = 15) and 72% (n = 13) of patients, respectively [22]. Adverse effects such as dose-dependent leukopenia, hepatotoxicity, and nephritis underscore the need for vigilant patient monitoring [36–38]. In one reviewed case (n = 1/21), azathioprine was discontinued because of an increase in hepatic cytolysis parameters [37].

Cyclophosphamide

In case reports of patients with UV aged between 12 and 65 years (58% female, n = 12) [Table 11 of the ESM], cyclophosphamide reduced skin symptoms in 58% of patients (n = 7/12) and improved extracutaneous symptoms, such as glomerulonephritis [39], in nearly all patients (n = 11/12). Cyclophosphamide is often used in combination with SGC to enhance efficacy and mitigate the severity of side effects. While only one study reviewed reported non-serious AEs in two patients [40], cyclophosphamide can have potentially severe side effects including myelosuppression, bladder and gonadal toxicity, and cytopenia [41]. These risks highlight the importance of careful patient selection, vigilant monitoring, and a thorough assessment of the risk-benefit ratio.

Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF)

In the studies reviewed, MMF improved cutaneous symptoms in 75% of patients (n = 9/12), including a larger study of ten patients where 70% benefited [21] (Table 12 of the ESM). Mycophenolate mofetil also demonstrated positive effects on extracutaneous manifestations of UV in two case reports. Although it has a favorable safety profile with no reported AEs in the studies reviewed, MMF was most commonly used as a fourth-line therapy [21]. Nevertheless, it remains a viable therapeutic option for patients with refractory or severe cases of UV [42]. In addition, MMF has been proposed as maintenance therapy after cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone pulse in patients with UV [43].

Dapsone

Several publications (Table 13 of the ESM) reported the use of dapsone in UV, mainly in HUV, most frequently at a dose of 100 mg daily (range: 25–150 mg daily). Dapsone has been shown to be effective for cutaneous symptoms in almost all cases, including the resolution of wheals, burning, and pain. Dapsone has also been shown to improve musculoskeletal pain, fever, fatigue, and gastrointestinal symptoms. In three of 11 case reports, dapsone therapy was discontinued because of serious side effects, including severe drug reactions, after just a few weeks of use [44–46]. However, this was typically observed at a dose of 100 mg or more. In addition, dapsone was often used in combination with other systemic therapies, making it difficult to assess its independent effectiveness.

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ)

In several publications (Table 14 of the ESM), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) reportedly helped approximately 57% of patients with UV (n = 74/130). Daily dosages ranged from 100 to 400 mg, with 400 mg/day being the preferred dosage [2]. In two larger case series as well as a web-based questionnaire of patients with UV, response rates of 75% (n = 18/24 [22]), 54% (n = 14/26 [47]), and 76% (n = 36/47 [3]), respectively, were reported. HCQ was frequently administered alongside SGCs. Combining HCQ with prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/day) achieved complete remission in 88% (n = 15/17) of HUV cases, with the authors typically initiating treatment with both drugs and then continuing with HCQ alone to mitigate the long-term adverse effects of SGCs [2, 48–50]. One study indicated that HCQ was as effective as SGCs while exhibiting a favorable AE profile [22]. The efficacy of HCQ typically became apparent within 3 months of treatment initiation. It was predominantly used for treating HUV/hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome (HUVS), leading to complete remission of skin symptoms and improvements in extracutaneous symptoms affecting the joints, lungs, and eyes. Additionally, HCQ contributed to improved immunological markers among patients with UV, including increased complement components [2].

Intravenous Immunoglobulins (IVIg)

Intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) exhibit immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties and have been effectively utilized in several cutaneous autoimmune diseases including SLE, dermatomyositis, pemphigus, and chronic urticaria [51]. However, the strength of evidence supporting the use of IVIgs in treating UV is limited. IVIgs were effective at doses of 1–2 g/kg administered every 4 weeks in four case reports involving patients with UV aged between 4 and 76 years. This cohort included two patients with HUV and one patient with HUVS, all of whom achieved full clinical remission (Table 15 of the ESM).

In summary, SGC should be considered in moderate-to-severe cases of UV with pronounced systemic manifestations. However, long-term use should be avoided, particularly in vulnerable patient populations, such as older patients with comorbidities. The dosage should be tapered as soon as possible to mitigate long-term adverse effects, though this may not always be possible, especially in refractory UV cases. Other immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive therapies may serve as SGC-sparing agents and can be beneficial for patients with UV with multi-organ involvement and underlying rheumatic diseases, such as SLE. Nonetheless, similarly to SGCs, these therapies can have potentially severe side effects, necessitating a careful evaluation of the risk–benefit ratio and close monitoring of both clinical and laboratory parameters.

Other Treatments

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were used for the treatment of UV in numerous studies (Table 16 of the ESM). Several different agents and dose regimens, often combined with additional drugs, are described in the literature with inconsistent effects on cutaneous and extracutaneous symptoms. Importantly, most reports are single case reports or small case series, and no controlled studies are available, rendering it difficult to assess the benefits of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of UV. We suggest that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be taken as needed or continuously as supplementary therapy by patients with UV with skin pain and pain of other localizations, such as abdominal pain and/or fever.

In three studies reporting on colchicine as a UV treatment, 30% of patients (n = 20/66) benefited from the therapy (Table 17 of the ESM). Both patients with NUV/HUV were treated with doses that ranged between 0.5 mg/day and 0.6 mg three times a day (1.0–1.2 mg/day in most cases), resulting in complete remission of skin symptoms and improvements in extracutaneous symptoms affecting the joints and gastrointestinal system in some cases [2]. In small case series and case reports, colchicine was found to be effective in only around 16% of patients [2, 52], and the response rate in one of our studies was also low [3]. The efficacy seems to increase when colchicine is combined with SGC, and 92% (n = 13) of patients responded to the combined treatment [2, 53]. However, the efficacy in these studies may be associated with the effectiveness of SGC. Reports on the efficacy of H2-antihistamines (no data), anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibodies (no data), anti-IL-6 receptor (tocilizumab), montelukast, tranexamic acid, doxepin, thalidomide, pentoxifylline, plasmapheresis, and danazol (Table 18 of the ESM) are largely limited to individual case reports, and in most of them, the drugs showed very limited or no benefit, or the efficacy was not clear as they were often administered in combination with other medications [30, 44, 48, 54–65].

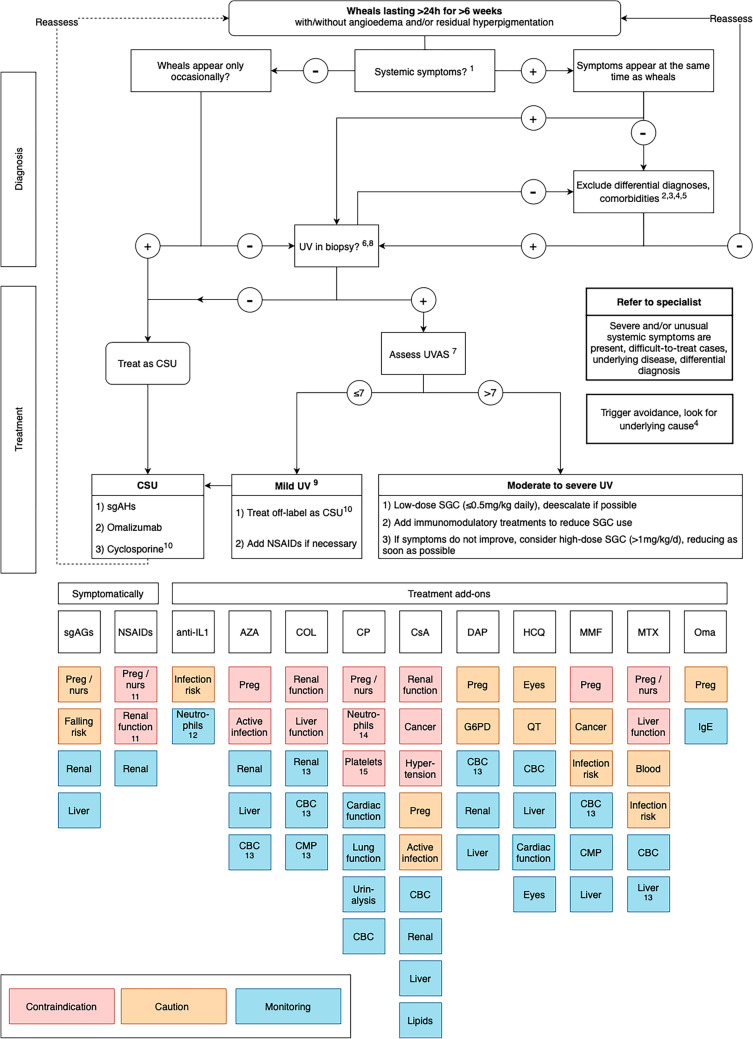

An Algorithm for the Management of UV

We developed an algorithm for UV management based on the aforementioned data (Fig. 1). This algorithm incorporates findings from the literature and the coauthors’ clinical experience in treating patients with UV. An initial draft was modified, and a final version was agreed upon following multiple rounds of feedback among the coauthors.

Fig. 1.

Treatment algorithm for urticarial vasculitis (UV). ANA anti-nuclear antibodies AZA azathioprine, Blood hematotoxicity, CBC complete blood count, CMP complete metabolic panel, COL colchicine, CP cyclophosphamide, CRP c-reactive protein, CsA cyclosporine A, CSU chronic spontaneous urticaria, DAP dapson, ENA extractable nuclear antigen antibodies, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, h hours, HCQ hydroxychloroquine, IgE immunoglobulin E, IL1 interleukin-1, Liver liver function, MMF mycophenolate mofetil, MTX methotrexate, NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, nurs nursing, Oma omalizumab, Preg pregnant, Renal renal function, sgAHs second-generation anti-histamines, SGC systemic glucocorticosteroids, UVAS Urticarial Vasculitis Activity Score, UVAS7 Urticarial Vasculitis Activity Score assessed for 7 days. 1. Examples for systemic symptoms: fever, arthralgia, abdominal pain, eye inflammation. 2. Possible investigations: CBC, CRP, ESR, hepatic panel, ANA/ENA, C3, C4, CH50, C1q, creatinine, urinalysis, serum and urine protein, electrophoresis, serum immunofixation electrophoresis. If C3/C4 complement levels are below normal range class UV as HUV. 3. Neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis in autoinflammatory disease or other vasculitis. 4. Comorbidities: systemic lupus erythematosus, malignancies, active infections. 5. Consider triggers: e.g., drug withdrawal, (treatment of) underlying disease. 6. For UV diagnosis, the following should be present: leukocytoclasia, fibrin deposits, and extravasated erythrocytes [68]. 7. (Re)assess UVAS7 for past 7 days every 4 weeks and de-escalate if possible to avoid adverse events. If wheals are the only symptom present, consider treating as mild UV even if UVAS7 is higher than 7. 8. If mild disease activity with predominantly itchy wheals, treatment with sgAHs and omalizumab can be considered before taking a skin biopsy. 9. Mild UV: skin-limited symptoms with or without mild arthralgia and/or mild general symptoms. 10. When treating sgAH and omalizumab-non-responsive UV, cyclosporine may be substituted with other treatments/add-ons, e.g., low-dose SGC, HCQ or dapsone, based on the patient profile, risk-benefit assessment, and physician and patient preferences (shared decision making). 11. Unless when using paracetamol. 12. When using anakinra. 13. Based on a set schedule. 14. Do not use if neutrophils <1500/mm3. 15. Do not use if platelets <50,000/mm3

Where known, triggers should be avoided in all patients with UV. The selection of an appropriate treatment should be guided by the UVAS [4] assessed over 7 days (UVAS7). Patients with CSU with occasional UV-like urticarial lesions and patients with UV with skin-limited symptoms and/or mild arthralgia/malaise (total UVAS7 ≤7 out of 70) can initially be treated using the step-wise algorithm for chronic urticaria including sgAHs, omalizumab, and cyclosporine A (all off-label in UV). However, there is little evidence on the use of cyclosporine in UV, which should be considered when choosing treatment. In a meta-analysis of randomized trials on systemic treatments for atopic dermatitis, cyclosporine A, administered at a dose of 4–5 mg/kg/day, showed a lower incidence of serious AEs compared with SGCs [66]. This suggests that cyclosporine A may offer a favorable safety profile, particularly in long-term use. However, cyclosporine A may be substituted with other treatments or add-ons based on the patient profile in cases of sgAH and omalizumab-non-responsive UV.

Setting the UVAS7 cut-off at ≤7 ensures that patients with multiple or more severe symptoms are escalated appropriately. However, patients whose illness is limited exclusively to the skin may be considered mild cases of UV even if their UVAS7 score exceeds 7. In patients with UV with more severe symptoms (UVAS7 >7), therapy should be aimed at symptom control and tailored to the organ affected. Some patients with UV, especially those with hypocomplementemic forms, may require a multidisciplinary approach to address an underlying disease, such as SLE, cancer, or infection. The application of immunosuppressive therapy should be based on its availability, the patient’s symptoms, and its safety profile. This may include SGC, dapsone, hydroxychloroquine, and/or anti-IL-1 therapies.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, this is not a systematic review, and some studies were not included. Second, the proposed algorithm is based on the expert opinion of the coauthors of this review and available literature, primarily case reports and case series. Furthermore, few publications specified the treatment of children, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and other vulnerable patients. The treatment algorithm should be adjusted to meet the needs of these populations. Last, drug combinations were used in many studies, making the identification of individual drug efficacy difficult.

Conclusions and Outlook

Urticarial vasculitis treatment continues to be a challenge with no licensed medications available. The proposed algorithm is an attempt to assist treating physicians in selecting an appropriate therapy for patients with UV. The development of a guideline for the management of UV based on an international expert consensus, supported by the international network of Urticaria Centers of Reference and Excellence (UCARE), represents the next step towards establishing a standardized therapy algorithm [67]. In this context, there is a need for standardized patient-reported outcomes, including the validation of the UVAS. Furthermore, the pathomechanisms of the disease, including disease endotypes and corresponding biomarkers, as well as possible coexistence with CSU, must be further investigated. This will provide indications for new therapeutic options to be developed, including disease-modifying therapies. Prospective studies with current and novel drugs are needed and could provide further insights into UV pathogenesis and treatment.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Marcus Maurer for his outstanding leadership. He is sorely missed. We thank Julia Föll for her assistance in proofreading the manuscript and providing corrections to improve the clarity and accuracy of the text.

Declarations

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

Nikolai Dario Rothermel, Carolina Vera Ayala, Leonie Shirin Herzog, Polina Pyatilova, and Sophia Neisinger have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article. Emek Kocatürk was a speaker/consultant and/or advisor for and/or has received research funding from Novartis, Menarini, LaRoche Posey, Sanofi, Bayer, Abdi İbrahim, and Pfizer outside of the submitted work. Indrashis Podder has no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the current work. Outside of it, he is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for Menarini, Sun Pharmaceuticals, Glenmark, Cipla, and Alkem Laboratories. Jie Shen Fok has previously received speaker honorarium or/and travel sponsorship from CSL Behring, Menarini, Viatris, Takeda, and Novartis outside of submitted work. Manuel P. Pereira has received research funding from Almirall and Pfizer; is an investigator for Allakos, Celldex Therapeutics, Incyte, Sanofi, and Trevi Therapeutics; and has received consulting fees, speaker honoraria and/or travel fees from AbbVie, Beiersdorf, Celltrion, Doctorflix, Eli Lilly, GA2LEN, Galderma, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, P.G. Unna Academy, Sanofi, Streamed UP, and Trevi Therapeutics. Margarida Gonçalo is or has been advisor and/or received fees for lectures from AbbVie, Astra-Zeneca, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda outside of the submitted work. Melba Munoz is or recently was, outside of the submitted work, a speaker and/or advisor for and/or has received research funding from Jasper Therapeutics, Celldex Therapeutics, Takeda, GA2LEN, UNEV, Astra Zeneca, and Roche. Karoline Krause has no conflict of interest related to this work. Outside of it, she received research funding and or honoraria from Bayer, Beiersdorf, Berlin Chemie, CSL Behring, Moxie, Novartis, Roche/CHUGAI, Sobi, and Takeda. Marcus Maurer is or recently was, outside of the submitted work, a speaker and/or advisor for and/or has received research funding from Allakos, Alexion, Alvotech, Almirall, Amgen, Aquestive, argenX, AstraZeneca, Celldex, Celltrion, Clinuvel, Escient, Evommune, Excellergy, GSK, Incyte, Jasper, Kashiv, Kyowa Kirin, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Menarini, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Moxie, Noucor, Novartis, Orion Biotechnology, Resoncance Medicine, Sanofi/Regeneron, Santa Ana Bio, Septerna, Servier, Third HarmonicBio, ValenzaBio, Vitalli Bio, Yuhan Corporation, and Zurabio. Hanna Bonnekoh was a speaker/consultant and/or advisor for and/or has received research funding AbbVie, Novartis, Sanofi Aventis, and ValenzaBio outside of the submitted work. Pavel Kolkhir was a speaker/consultant and/or advisor for and/or has received research funding from Novartis, ValenzaBio, and Roche outside of the submitted work.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

This is a review article and does not involve human subjects, therefore no primary data were used. Data from studies presented in this article are summarized in the tables and supplementary tables.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ Contributions

NR, HB, and PK contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, data curation, and writing (original draft). AR, CVA, EK, IP, JF, LH, MP, MG, MMu, PP, and SN contributed to the methodology, data curation, and writing (original draft). MM and KK contributed to data curation and writing (review and editing). All authors contributed to the consensus process that led to this article, reviewed the literature, critically reviewed and revised the article, and proofread and approved the final version.

Footnotes

Marcus Maurer is deceased.

Hanna Bonnekoh and Pavel Kolkhir have contributed equally and are designated as last co-authors.

References

- 1.Arora A, Wetter DA, Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Davis MD, Lohse CM. Incidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, 1996 to 2010: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(11):1515–24. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolkhir P, Grakhova M, Bonnekoh H, Krause K, Maurer M. Treatment of urticarial vasculitis: s systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(2):458–66. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnekoh H, Jelden-Thurm J, Butze M, Krause K, Maurer M, Kolkhir P. In urticarial vasculitis, long disease duration, high symptom burden, and high need for therapy are linked to low patient-reported quality of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(10):2734-41.e7. 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krause K, Mahamed A, Weller K, Metz M, Zuberbier T, Maurer M. Efficacy and safety of canakinumab in urticarial vasculitis: an open-label study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(3):751-4.e5. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonnekoh H, Jelden-Thurm J, Allenova A, Chen Y, Cherrez-Ojeda I, Danilycheva I, et al. Urticarial vasculitis differs from chronic spontaneous urticaria in time to diagnosis, clinical presentation, and need for anti-inflammatory treatment: an international prospective UCARE study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11(9):2900-10.e21. 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krause K, Bonnekoh H, Jelden-Thurm J, Asero R, Gimenez-Arnau AM, Cardoso JC, et al. Differential diagnosis between urticarial vasculitis and chronic spontaneous urticaria: an international Delphi survey. Clin Transl Allergy. 2023;13(10): e12305. 10.1002/clt2.12305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kausar S, Yalamanchili A. Management of haemorrhagic bullous lesions in Henoch-Schonlein purpura: is there any consensus? J Dermatol Treat. 2009;20(2):88–90. 10.1080/09546630802314670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazandjieva J, Antonov D, Kamarashev J, Tsankov N. Acrally distributed dermatoses: vascular dermatoses (purpura and vasculitis). Clin Dermatol. 2017;35(1):68–80. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathur AN, Mathes EF. Urticaria mimickers in children. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26(6):467–75. 10.1111/dth.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marzano AV, Maronese CA, Genovese G, Ferrucci S, Moltrasio C, Asero R, et al. Urticarial vasculitis: clinical and laboratory findings with a particular emphasis on differential diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(4):1137–49. 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao X, Xue P, Shi Y, Yao J, Cao W, Zhang L, et al. The efficacy and safety of high-dose nonsedating antihistamines in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2023;24(1):23. 10.1186/s40360-023-00665-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber-Schoendorfer C, Schaefer C. The safety of cetirizine during pregnancy: a prospective observational cohort study. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;26(1):19–23. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarz EB, Moretti ME, Nayak S, Koren G. Risk of hypospadias in offspring of women using loratadine during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Saf. 2008;31(9):775–88. 10.2165/00002018-200831090-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US FDA. Highlights of prescribing information: Xolair® (omalizumab) injection, for subcutaneous use. Initial U.S. approval: 2003. 2024. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/103976s5245lbl.pdf. [Accessed 17 Apr 2024].

- 15.Chuang KW, Hsu CY, Huang SW, Chang HC. Association between serum total IgE levels and clinical response to omalizumab for chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11(8):2382-9.e3. 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menzella F, Fontana M, Contoli M, Ruggiero P, Galeone C, Capobelli S, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab treatment over a 16-year follow-up: when a clinical trial meets real-life. J Asthma Allergy. 2022;15:505–15. 10.2147/jaa.S363398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai T, Wang S, Xu Z, Zhang C, Zhao Y, Hu Y, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with persistent uncontrolled allergic asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8191. 10.1038/srep08191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Türk M, Carneiro-Leão L, Kolkhir P, Bonnekoh H, Buttgereit T, Maurer M. How to treat patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria with omalizumab: questions and answers. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(1):113–24. 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bettuzzi T, Deroux A, Jachiet M, Farhat MM, Wipff J, Fabre M, et al. Dramatic but suspensive effect of interleukin-1 inhibitors for persistent urticarial vasculitis: a French multicentre retrospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(10):1446–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Botsios C, Sfriso P, Punzi L, Todesco S. Non-complementaemic urticarial vasculitis: successful treatment with the IL-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007;36(3):236–7. 10.1080/03009740600938647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jachiet M, Flageul B, Deroux A, Le Quellec A, Maurier F, Cordoliani F, et al. The clinical spectrum and therapeutic management of hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis: data from a French nationwide study of fifty-seven patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(2):527–34. 10.1002/art.38956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jachiet M, Flageul B, Bouaziz JD, Bagot M, Terrier B. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis. Rev Méd Interne. 2018;39(2):90–8. 10.1016/j.revmed.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasi PM, Tawbi HA, Oddis CV, Kulkarni HS. Clinical review: serious adverse events associated with the use of rituximab: a critical care perspective. Crit Care. 2012;16(4):231. 10.1186/cc11304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuberbier T, Abdul Latiff AH, Abuzakouk M, Aquilina S, Asero R, Baker D, et al. The international EAACI/GA2LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2022;77(3):734–66. 10.1111/all.15090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satapathy A, Biswal B, Priyadarshini L, Sirka C, Das L, Mishra P, et al. Clinicopathological profile and outcome of childhood urticaria vasculitis: an observational study. Cureus. 2020;12(11): e11489. 10.7759/cureus.11489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ledford D, Broder MS, Antonova E, Omachi TA, Chang E, Luskin A. Corticosteroid-related toxicity in patients with chronic idiopathic urticariachronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2016;37(6):458–65. 10.2500/aap.2016.37.3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson JA, Cavaliere LF, Grant-Kels JM. Cutaneous vasculitis: diagnosis and management. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24(5):414–29. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gu SL, Jorizzo JL. Urticarial vasculitis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(3):290–7. 10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kulthanan K, Chaweekulrat P, Komoltri C, Hunnangkul S, Tuchinda P, Chularojanamontri L, et al. Cyclosporine for chronic spontaneous urticaria: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(2):586–99. 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez A, Woods A, Grattan CE. Methotrexate: a useful steroid-sparing agent in recalcitrant chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(1):191–4. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teles C, Gaspar E, Gonçalo M, Santos L. Normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis secondary to Lyme disease: a rare association with challenging treatment. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2023;53(1):27–9. 10.1177/14782715221144167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borcea A, Greaves MW. Methotrexate-induced exacerbation of urticarial vasculitis: an unusual adverse reaction. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(1):203–4. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smets K, Van Baelen A, Sprangers B, De Haes P. Correct approach in urticarial vasculitis made early diagnosis of lupus nephritis possible: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16(1):314. 10.1186/s13256-022-03477-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macêdo PA, Garcia CB, Schmitz MK, Jales LH, Pereira RMR, Carvalho JF. Juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis associated with urticarial vasculitis syndrome: a unique presentation. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(11):3643–6. 10.1007/s00296-010-1484-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breda L, Nozzi M, Harari S, Del Torto M, Lucantoni M, Scardapane A, et al. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis (HUVS) with precocious emphysema responsive to azathioprine. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(5):891–5. 10.1007/s10875-013-9886-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venzor J, Lee WL, Huston DP. Urticarial vasculitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2002;23(2):201–16. 10.1385/CRIAI:23:2:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filosto M, Cavallaro T, Pasolini G, Broglio L, Tentorio M, Cotelli M, et al. Idiopathic hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis-linked neuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 2009;284(1):179–81. 10.1016/j.jns.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knowles SR, Gupta AK, Shear NH, Sauder D. Azathioprine hypersensitivity-like reactions: a case report and a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20(4):353–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1995.tb01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vallianou K, Skalioti C, Liapis G, Boletis JN, Marinaki S. A case report of hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis presenting with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):351. 10.1186/s12882-020-02001-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Worm M, Muche M, Schulze P, Sterry W, Kolde G. Hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis: successful treatment with cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone pulse therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(4):704–7. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogino MH, Tadi P. Cyclophosphamide. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis MDP, van der Hilst JCH. Mimickers of urticaria: urticarial vasculitis and autoinflammatory diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(4):1162–70. 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Worm M, Sterry W, Kolde G. Mycophenolate mofetil is effective for maintenance therapy of hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(6):1324. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christiansen J, Kahn R, Schmidtchen A, Berggård K. Idiopathic angioedema and urticarial vasculitis in a patient with a history of acquired haemophilia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(2):227–8. 10.2340/00015555-1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leslie KS, Gaffney K, Ross CN, Ridley S, Barker TH, Garioch JJ. A near fatal case of the dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome in a patient with urticarial vasculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28(5):496–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chun JS, Yun SJ, Kim SJ, Lee SC, Won YH, Lee JB. Dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome with circulating 190-kDa and 230-kDa autoantibodies. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(8):e798-801. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mehregan DR, Hall MJ, Gibson LE. Urticarial vasculitis: a histopathologic and clinical review of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(3 Pt 2):441–8. 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70069-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wisnieski JJ, Baer AN, Christensen J, Cupps TR, Flagg DN, Jones JV, et al. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome: clinical and serologic findings in 18 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74(1):24–41. 10.1097/00005792-199501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bostan E, Akdogan N, Gokoz O, Dogan S. Rapid response to combination of hydroxychloroquine and prednisolone in a patient with refractory hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6): e14531. 10.1111/dth.14531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boyer A, Gautier N, Comoz F, Hurault de Ligny B, Aouba A, Lanot A. Néphropathie associée à une vascularite urticarienne hypocomplémentémique: présentation d’un cas clinique et revue de la littérature. Nephrol Ther. 2020;16(2):124–35. 10.1016/j.nephro.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prins C, Gelfand EW, French LE. Intravenous immunoglobulin: properties, mode of action and practical use in dermatology. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87(3):206–18. 10.2340/00015555-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Serarslan G, Okyay E. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in patients with urticarial vasculitis. North Clin Istanb. 2021;8(5):513–7. 10.14744/nci.2020.55476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fujii M, Kishibe M, Ishida-Yamamoto A. Case of hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis with Sjögren’s syndrome successfully treated with oral corticosteroid and colchicine. J Dermatol. 2021;48(2):e112–3. 10.1111/1346-8138.15712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mukhtyar C, Misbah S, Wilkinson J, Wordsworth P. Refractory urticarial vasculitis responsive to anti-B-cell therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(2):470–2. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Asherson RA, D’Cruz D, Stephens CJ, McKee PH, Hughes GR. Urticarial vasculitis in a connective tissue disease clinic: patterns, presentations, and treatment. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1991;20(5):285–96. 10.1016/0049-0172(91)90029-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Asherson RA, Buchanan NM, d’Cruz D, Hughes GR. Urticarial vasculitis, IgA deficiency and C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency in the presence of an IgG monoclonal gammopathy: a case report. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17(2):137–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Athanasiadis GI, Pfab F, Kollmar A, Ring J, Ollert M. Urticarial vasculitis with a positive autologous serum skin test: diagnosis and successful therapy. Allergy. 2006;61(12):1484–5. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown NA, Carter JD. Urticarial vasculitis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9(4):312–9. 10.1007/s11926-007-0050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lipman MC, Carding SK. Successful drug treatment of immune reconstitution disease with the leukotriene receptor antagonist, montelukast: a clue to pathogenesis? AIDS. 2007;21(3):383–4. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011cb38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koch PE, Lazova R, Rosen JR, Antaya RJ. Urticarial vasculitis in an infant. Cutis. 2008;81(1):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morgan M. Treatment of refractory chronic urticaria with sirolimus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(6):637–9. 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buck A, Christensen J, McCarty M. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5(1):36–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Díez LS, Tamayo LM, Cardona R. Omalizumab: therapeutic option in chronic spontaneous urticaria difficult to control with associated vasculitis, report of three cases. Biomedica. 2013;33(4):503–12. 10.7705/biomedica.v33i4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fueyo-Casado A, Campos-Muñoz L, González-Guerra E, Pedraz-Muñoz J, Cortés-Toro JA, López-Bran E. Effectiveness of omalizumab in a case of urticarial vasculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42(4):403–5. 10.1111/ced.13076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garcıa Ponce JPC, Jimenez Timon S, Maghfour Martin Y, Ahmida T, Hernandez Arbeiza FJ. Urticarial vasculitis (leucocytoclastic vasculitis) treated with omalizumab: case report. Allergy. 2014;69(3):321. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chu AWL, Wong MM, Rayner DG, Guyatt GH, Díaz Martinez JP, Ceccacci R, et al. Systemic treatments for atopic dermatitis (eczema): systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;152(6):1470–92. 10.1016/j.jaci.2023.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maurer M, Metz M, Bindslev-Jensen C, Bousquet J, Canonica GW, Church MK, et al. Definition, aims, and implementation of GA(2) LEN Urticaria Centers of Reference and Excellence. Allergy. 2016;71(8):1210–8. 10.1111/all.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Puhl V, Bonnekoh H, Scheffel J, Hawro T, Weller K, von den Driesch P, et al. A novel histopathological scoring system to distinguish urticarial vasculitis from chronic spontaneous urticaria. Clin Transl Allergy. 2021;11(2): e12031. 10.1002/clt2.12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bonnekoh H, Krause K, Kolkhir P. Chronic recurrent wheals: if not chronic spontaneous urticaria, what else? Allergol Select. 2023;7:8–16. 10.5414/alx02375e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kolkhir P, Laires PA, Salameh P, Asero R, Bizjak M, Košnik M, et al. The benefit of complete response to treatment in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: CURE results. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11(2):610-20.e5. 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bernstein JA, Kavati A, Tharp MD, Ortiz B, MacDonald K, Denhaerynck K, et al. Effectiveness of omalizumab in adolescent and adult patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review of “real-world” evidence. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18(4):425–48. 10.1080/14712598.2018.1438406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.