Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of an integrated patient-specific electronic clinical reminder system on diabetes and coronary artery disease (CAD) care and to assess physician attitudes toward this reminder system.

Design: We enrolled 194 primary care physicians caring for 4549 patients with diabetes and 2199 patients with CAD at 20 ambulatory clinics. Clinics were randomized so that physicians received either evidence-based electronic reminders within their patients' electronic medical record or usual care. There were five reminders for diabetes care and four reminders for CAD care.

Measurements: The primary outcome was receipt of recommended care for diabetes and CAD. We created a summary outcome to assess the odds of increased compliance with overall diabetes care (based on five measures) and overall CAD care (based on four measures). We surveyed physicians to assess attitudes toward the reminder system.

Results: Baseline adherence rates to all quality measures were low. While electronic reminders increased the odds of recommended diabetes care (odds ratio [OR] 1.30, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.67) and CAD (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.01–1.55), the impact of individual reminders was variable. A total of three of nine reminders effectively increased rates of recommended care for diabetes or CAD. The majority of physicians (76%) thought that reminders improved quality of care.

Conclusion: An integrated electronic reminder system resulted in variable improvement in care for diabetes and CAD. These improvements were often limited and quality gaps persist.

In the landmark report “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” the Institute of Medicine suggested that large gaps between evidence-based care and actual clinical practice demand intensified strategies for improving health care quality.1 Quality improvement is particularly important in chronic disease management given that chronic diseases account for 75% of total health care costs in the United States and prevention of long-term complications depends on the provision of essential evidence-based services.2 Despite a variety of quality improvement efforts, the recent National Healthcare Quality Report indicates that care for patients with chronic diseases including diabetes and coronary artery disease remains inadequate.3

Electronic health records may play a critical role in improving health care quality through increasing access to patient information at the point of care and standardizing clinical decision making.4,5 Computer-generated paper reminder systems have increased rates of cancer screening and adult immunizations6,7,8 but have been less successful for more complex disease management such as diabetes.7

Electronic reminders offer several advantages over paper-based reminders, including integration into the workflow and the ability to provide patient-specific recommendations that are immediately responsive to new or updated information within the electronic record, such as a new diagnosis of diabetes or coronary artery disease, a new laboratory result, or new medication prescriptions. However, several previous studies of electronic reminders have also been unsuccessful in improving care for both diabetes9 and heart disease,10,11 perhaps due to design considerations or lack of physician acceptance. We developed an electronic reminder system for diabetes and coronary artery disease management within an existing electronic health record with the goals of (1) assessing the impact of this system on quality of care and (2) understanding physician attitudes toward this system.

Methods

Study Setting

Partners HealthCare System is an integrated health care network consisting of outpatient clinics, community hospitals, and two academic teaching hospitals (Brigham and Women's Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital) in the Boston area. In July 2000, primary care physicians began using an internally developed ambulatory electronic medical record system called the Longitudinal Medical Record. This electronic record allows physicians to maintain patient problem, medication, and allergy lists as well as to view laboratory results. Physicians also use the system to enter patient notes and generate medication prescriptions. At the time of this study, the system was being used by 255 primary care physicians practicing at 20 outpatient clinics for the care of all patients in their panels. These 20 clinics included four community health centers, nine hospital-based clinics, and seven off-site practices. The Partners Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Intervention

We used evidence-based guidelines12,13,14,15 to identify five recommendations for diabetes care and four recommendations for coronary artery disease care. The recommendations for diabetes care included annual low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol testing, biennial hemoglobin A1c testing, annual dilated eye examinations, initiation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor therapy in the presence of hypertension, and initiation of statin therapy for LDL cholesterol ≥130 mg/dL. The recommendations for coronary artery disease care included annual LDL cholesterol testing, initiation of aspirin therapy, initiation of beta-blocker therapy, and initiation of statin therapy for LDL cholesterol ≥130 mg/dL. Diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease were identified using coded diagnoses in the electronic problem list. In our electronic medical record, the positive predictive value based on the presence of a problem list diagnosis is 94% for diabetes and 96% for coronary artery disease, with a negative predictive value of 100% for both.16 All laboratory results were identified from the Partners central data repository and reflected the most current information available. Medication use was based on coded information entered in the electronic medication list.

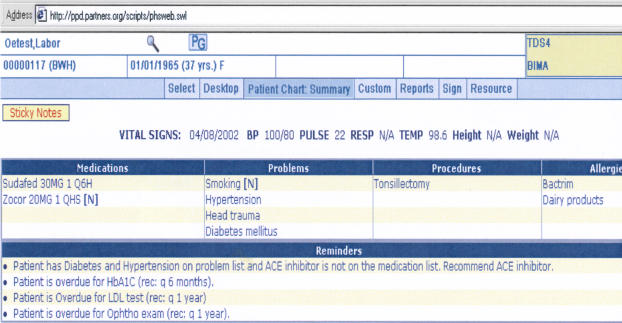

Each time that a clinician opened a patient chart within the Longitudinal Medical Record, the algorithm for all reminders was run to determine whether the patient had received care in accordance with the recommended practice guidelines. This algorithm searched all laboratory and radiology results as well as the problem list, medication list, and allergy list within the Longitudinal Medical Record. For clinicians in the intervention group, the appropriate reminders were then displayed within the main patient summary screen of the Longitudinal Medical Record alongside other pertinent information such as the patient medication list and problem list (▶). The reminders were suppressed for physicians practicing at control sites. In addition to the electronic reminders, sites in both the intervention and control arms were given the option of printing paper versions of the reminders that were generated using the same algorithms as the electronic reminders. These paper reminders were printed on a patient summary page that also included pertinent information such as the patient medication and problem lists, and were distributed to physicians at the beginning of a practice session. The paper reminders were used by 12 (60%) of the clinics in the study.

Figure 1.

Electronic clinical reminders are displayed within the main patient summary screen of the electronic medical record system. Physicians are able to view the reminders in conjunction with other pertinent patient information including active medical problems, medications, and allergies.

Subject Enrollment

Patients and physicians were enrolled on the first occasion during the study period (October 2002 to April 2003) that (1) a primary care physician (attending physician or resident) opened a patient chart within the electronic record and (2) a reminder was generated for a recommended health service. Therefore, all patients with overdue screening examinations or lack of appropriate medication initiation were enrolled in this study at the time their primary care physician accessed their chart and outcomes were assessed for all these patients at the end of the study period. Reminders were not delivered to physicians other than primary care doctors, including cardiologists and endocrinologists. The Partners Institutional Review Board approved a waiver of individual informed consent for physicians and patients in this study, as the goal of the intervention was to promote receipt of services that are widely accepted as the standard of care.

Randomization

We performed a stratified randomization of the 20 primary care sites based on site characteristics to balance the distributions of gender and socioeconomic factors between the intervention and control groups. The specific site characteristics included (1) identification as a women's health center and (2) identification as a community health center. Primary care physicians practicing at all 20 centers received electronic reminders for overdue preventive medicine services based on recommendations of the United States Preventive Services Task Force.17 We randomly assigned ten clinical sites to receive additional electronic reminders for diabetes and coronary artery disease care, with ten clinics serving as control sites that had no previous exposure to these disease-specific reminders.

Data Collection

Baseline patient and physician characteristics were obtained from Partners administrative databases. Data on reminders were stored at the time of generation, including the date of the reminder and the treating physician. Dates and values of subsequent laboratory tests were obtained from the Partners central data repository. Medication initiation was identified from the coded medication list. Screening dilated eye examinations were obtained from either (1) the hospital scheduling system indicating a completed appointment with an ophthalmologist or (2) the coded field for dilated eye examinations within the electronic record that can be updated by physicians. All data were collected for reminders delivered to a patient's primary care physician, who was defined based on (1) coded information within the electronic record or (2) a patient having at least three outpatient visits with the same primary care physician within the past two years.

We collected baseline adherence rates as of October 2002 for the entire sample of patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease receiving care at the 20 outpatient sites using similar methods of automated data extraction.

Survey

We surveyed all 255 primary care physicians via an internally developed survey instrument based on a previous survey conducted at our institution.18 The instrument assessed physician attitudes regarding barriers to guideline adherence and attitudes toward the electronic reminder system. We surveyed physicians in the intervention and control arms as both groups were exposed to electronic reminders for routine preventive medicine, although only physicians in the intervention arm received reminders for diabetes and coronary artery disease. Physician perceptions surrounding guideline adherence were recorded on a four-point Likert scale and attitudes regarding electronic reminders were recorded on a seven-point Likert scale. Surveys were mailed to providers after exposure to the reminder system for two months, with a second mailing to nonresponders after three weeks.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was receipt of recommended care at the conclusion of the study period. We calculated a summary proportion of reminders resulting in recommended action at the end of the study period for the set of diabetes reminders and the set of coronary artery disease reminders. We weighted these two proportions by the total number of disease-specific reminders generated. We created a composite outcome for diabetes care as the number of appropriate health services received by a patient from among up to five possible recommendations with which that patient was not compliant, with each service assigned equal value. We created a similar composite outcome for the four coronary artery disease recommendations.

We developed a single multivariate binomial regression model to produce adjusted estimates of the impact of the reminders on overall diabetes care. For each patient, the number of services for which he or she was at risk of receiving was used as the fixed parameter in the binomial model, and the number of these services for which there was compliance was the outcome variable. We used the generalized estimating equations approach, implemented through the GENMOD procedure in the SAS statistical package, to account for clustering of patients within clinical sites. The model was adjusted for total length of follow-up time for each patient as well as for patient age, sex, race, and insurance status and provider age and sex. A similar model was developed to produce adjusted estimates of the impact of the reminders on overall coronary artery disease care.

We analyzed the effect of each individual reminder by developing multivariate Cox proportional hazards models with variances adjusted to account for clustering within sites using the robust estimator inference.19 Time to receipt of each service was calculated for each patient based on the date of the generation of the original reminder. We chose to analyze time to receipt of recommended care to more fully determine the impact of the electronic reminders on receiving care in a timely manner as well as to avoid the inherent difficulties in choosing a static time point for assessment of outcomes that vary in ease of completion (medication ordering versus scheduling referrals for dilated eye examinations). These models were adjusted for the use of a paper reminder system at each clinic, provider age and sex, and patient age, sex, race, and insurance status. We included demographic variables in these models to adjust for potential variation in quality of care due to characteristics such as sex and race.

Before the intervention, we estimated 90% power to detect a 10% absolute increase in compliance rates in the intervention arm compared to the control arm.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

We enrolled 194 primary care physicians caring for 6243 patients with at least one overdue health service, including 4549 patients with diabetes and 2199 patients with coronary artery disease. Patients in the intervention and control arms displayed clinically significant differences in the distribution of race and insurance status (▶). There was a higher proportion of Hispanics in the intervention group (22%) versus the control group (9%) as well as a higher proportion of Medicaid patients in the intervention group (17%) in comparison to the control group (10%). Physicians in the intervention and control groups were similar in age and sex.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient and Physician Characteristics among Enrolled Patients with Overdue Recommendations

| Intervention | Control | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | (n = 2924) | (n = 3319) | |

| Mean age, yr (± SD) | 62.4 (± 14) | 65.3 (± 14) | <0.001 |

| Male (%) | 1201 (41) | 1529 (46) | <0.001 |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 1588 (54) | 2114 (64) | <0.001 |

| Black | 464 (16) | 414 (12) | |

| Hispanic | 631 (22) | 304 (9) | |

| Asian | 35 (1) | 87 (3) | |

| Other | 49 (2) | 58 (2) | |

| Unknown | 157 (5) | 342 (10) | |

| Insurance (%) | |||

| Medicare | 1425 (49) | 1760 (53) | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 501 (17) | 345 (10) | |

| Commercial | 936 (32) | 1157 (35) | |

| Other | 61 (2) | 55 (2) | |

| Physician characteristics | (n = 92) | (n = 102) | |

| Mean age, yr (± SD) | 39.2 (± 10) | 41.4 (± 11) | 0.15 |

| Male (%) | 32 (35) | 49 (48) | 0.06 |

SD = standard deviation.

Baseline adherence rates are shown in ▶ for the entire sample of patients with diabetes or coronary artery disease receiving care at the 20 study sites. The adherence rates for both diabetes and coronary artery disease care were among the highest for annual cholesterol monitoring and near the lowest for use of statin drugs in the presence of hypercholesterolemia. We enrolled from 9% to 47% of the total sample of patients with diabetes or coronary artery disease in our study, depending on the specific reminder (▶).

Table 2.

Baseline Adherence Rates in the Entire Population and Impact of Electronic Reminders in the Enrolled Population for Diabetes and Coronary Artery Disease Care

| Baseline Adherence, No. (% of total population)* | Enrolled Patient Population, No. (% of total population)† | Hazard Ratio for Intervention (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | ||||

| Annual cholesterol exam | 4957 (58) | 1185 (14) | 1.41 (1.15–1.72) | <0.001 |

| Biennial hemoglobin Alc exam | 4868 (57) | 2245 (26) | 1.14 (0.89–1.46) | 0.29 |

| Annual dilated eye exam | 1464 (17) | 4049 (47) | 1.38 (0.81–2.32) | 0.23 |

| Hypertension/ACE inhibitor use | 2761 (62) | 711 (16) | 1.42 (0.94–2.14) | 0.10 |

| Statin use for LDL cholesterol ≥130 mg/dL | 476 (31) | 595 (38) | 1.10 (0.65–1.85) | 0.73 |

| Coronary artery disease | ||||

| Annual cholesterol exam | 5039 (53) | 1151 (12) | 0.99 (0.75–1.29) | 0.92 |

| Aspirin use | 2883 (41) | 669 (9) | 2.36 (1.37–4.07) | 0.002 |

| Beta-blocker use | 2701 (38) | 808 (11) | 1.09 (0.72–1.63) | 0.69 |

| Statin use for LDL cholesterol ≥130 mg/dL | 495 (28) | 385 (21) | 1.51 (1.05–2.17) | 0.03 |

CI = confidence interval (adjusted for baseline patient and physician characteristics, as well as for clustering within clinics and the presence of a paper reminder system); ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; LDL = low-density lipoprotein.

This column includes baseline adherence data for the entire population of patients with diabetes or coronary artery disease. To be enrolled, patients had to meet the criteria of (1) nonadherence to at least one quality measure during the study period and (2) primary care physician receiving a reminder during the study period.

This column includes combined (intervention and control arm) sample sizes for patients enrolled in the study, as well as the proportion of the total population represented by each sample size. Enrolled patients met the criteria of (1) nonadherence to at least one quality measure during the study period and (2) primary care physician receiving a reminder during the study period.

Diabetes Reminders

The mean number of reminders per patient generated over the six-month intervention period in the intervention group was 6.1 versus 6.7 (generated but not displayed) in the control group (p = 0.004). Diabetes reminders resulted in the recommended action in 19% of patients in the intervention group versus 14% of patients in the control group. After adjusting for baseline patient and physician characteristics, patients in the intervention group were significantly more likely than control patients to receive recommended diabetes care based on the composite outcome (odds ratio [OR] 1.30, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.67).

Reminders for overdue annual cholesterol testing resulted in increased screening rates after adjusting for the use of a paper reminder system, and baseline patient and physician characteristics (hazard ratio [HR] 1.41, 95% CI 1.15–1.72). In addition, a reminder for the use of ACE inhibitors demonstrated a trend toward increased use in the intervention group (HR 1.42, 95% CI 0.94–2.14), although this effect did not achieve statistical significance. Reminders for statin use in the presence of hypercholesterolemia and for overdue annual dilated retinal examinations had no effect (▶).

Coronary Artery Disease Reminders

The mean number of reminders per patient generated in the intervention group (4.3) was less than that in the control group (5.4, p < 0.001). Coronary artery disease reminders resulted in the recommended action for overdue items in 22% of patients in the intervention group versus 17% of patients in the control group. Using the composite outcome, patients in the intervention group received recommended coronary artery disease care more often than those in the control group (OR 1.25, 95% confidence interval 1.01–1.55) after adjusting for baseline differences.

Individual reminders effective for improving care for patients with coronary artery disease included those for the use of statins in the presence of hypercholesterolemia (HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.05–2.17) and the use of aspirin therapy (HR 2.36, 95% CI 1.37–4.07). Reminders for overdue annual cholesterol monitoring and the use of beta-blocker therapy had no effect (▶).

Physician Survey

A total of 159 physicians responded to the survey, including 78 in the intervention arm and 81 in the control arm (62% response rate). Survey respondents were older than nonrespondents (39.4 years versus 36.5 years, p = 0.03), but similar proportions were women (59% for respondents versus 55% for nonrespondents, p = 0.57). The most common barriers to guideline adherence reported by physicians included lack of time during office visits (51%) and patient noncompliance or refusal (42%) (▶). There were multiple barriers to guideline adherence cited by physicians that are potentially amenable to a clinical decision support system, including lack of familiarity with specific guideline recommendations (40%), lack of awareness of guideline existence (38%), and forgetting to apply a guideline recommendation during an office encounter (26%).

Table 3.

Primary Care Physician Attitudes Regarding Guideline Adherence and Electronic Clinical Decision Support

| No. of Physicians Agreeing (%) | |

|---|---|

| Barriers to guideline adherence* | |

| Lack of time during patient visit | 81 (51) |

| Patient noncompliance or refusal of treatment | 66 (42) |

| Lack of knowledge of specific guideline recommendation | 64 (40) |

| Lack of awareness of guideline existence | 61 (38) |

| Disagree with guideline recommendation | 54 (34) |

| Agree with guideline, but forgot to apply during office visit | 42 (26) |

| Lack of reimbursement for services | 8 (5) |

| Electronic clinical decision support† | |

| Notice electronic reminders during a patient encounter | 60 (38) |

| Electronic reminders prompt physician to take specific action | 55 (35) |

| Electronic reminders useful for diabetes disease management‡ | 53 (68) |

| Electronic reminders useful for coronary artery disease management‡ | 41 (53) |

| Electronic reminders improve quality of patient care | 121 (76) |

Defined as either moderately (3) or extremely (4) significant on a 4-point Likert scale.

Defined as at least 5 on a 7-point Likert scale.

Among physician respondents in the intervention group (n = 78).

A large majority (71%) of physicians preferred to receive clinical decision support in an electronic format over a paper-based system, although only one third reported noticing the electronic reminders and acting on the recommendations (▶). Among physicians who noticed reminders, approximately 70% reported acting on the recommendation. In addition, a majority of physicians in the intervention group found electronic reminders for diabetes care (68%) and coronary artery disease (53%) useful for disease management. Overall, 76% of physicians thought that this clinical decision support system helps to improve quality of care for patients.

Discussion

While we now have a large scientific evidence base about what care to provide, practice has lagged substantially behind,20 suggesting that better tools for translating evidence into practice are urgently needed. Electronic decision support represents one such tool and has been highly touted,1 but a series of recent studies have demonstrated no benefit.10,11,21,22,23 In this study, we found that substantial quality gaps exist for the management of diabetes and coronary artery disease. Electronic clinical reminders improved the chance that patients would receive recommended care beyond the effect of existing paper reminder systems, although there was variability by service and gaps persisted. We were encouraged by the finding that the reminders were well received by the physicians and that the majority preferred electronic reminders to paper-based reminders.

Our findings of suboptimal care for diabetes and coronary artery disease are consistent with those of previous studies. A recent analysis of diabetes management among commercial managed care organizations demonstrated an annual cholesterol screening rate of only 63% and an annual HbA1c screening rate of 83%.24 Among patients with coronary artery disease, only 40% receive beta-blocker therapy and 38% receive aspirin therapy.25 Our physician survey and other meta-analyses26 provide insight into why rates of guideline adherence remain so low. While external factors such as lack of visit time and patient noncompliance are perceived as important issues, it is important to note that physician-related factors continue to be an issue, including lack of familiarity with guidelines and lack of agreement with guideline recommendations.

Despite the support for our reminder system expressed by physicians, many of the reminders did not affect provision of services. This finding is similar to other electronic reminder systems. In a recent investigation, Tierney et al.11 studied an electronic reminder system for coronary artery disease and congestive heart failure and found no significant impact on the management of heart disease. A similar system of electronic reminders within the Veterans Affairs health care system did not increase rates of beta-blocker use or cholesterol screening for patients with coronary artery disease and had a variable impact on diabetes quality measures.27

Our study provides insight into the mechanisms behind the successes and limitations of electronic reminder systems. We were able to demonstrate improvements in areas such as medication initiation where other systems have not succeeded. We attribute these successes to both effective design and physician acceptance. It is important for electronic decision support systems to provide actionable recommendations in a simple format to maximize their effectiveness.28 Our reminders provided succinct messages generally shorter than ten words in length with an immediately actionable item. In addition, we achieved physician acceptance by including many of the primary care physicians in the development process to maximize the integration of the system into the existing workflow. We also limited our reminder system to providing recommendations for aspects of care in which there is very little disagreement on appropriate management and kept the recommendations somewhat conservative to avoid inappropriate recommendations (for example, using an LDL cholesterol goal of 130 mg/dL for coronary artery disease instead of 100 mg/dL). This strategy avoids the pitfall of generating physician distrust of the reminder system while also capturing those patients in most need of improved disease management.

We also learned that requiring physician acknowledgment of reminders may be a critical step in achieving success, as highlighted by the small proportion of physicians who reported noticing the reminders during office encounters. The impact of this limitation is highlighted by the finding that among physicians who report noticing reminders, nearly three fourths acted on the recommendations. This suggests that our reminders could have a much larger impact by requiring physician acknowledgment of the recommendation.29 This is a challenging area, and there is a major tension between making reminders more intrusive and generating resentment among physicians. Our study also suggests that reminder systems may exhibit differential effectiveness depending on the service being recommended and the particular disease. For example, reminders for annual cholesterol testing were effective for patients with diabetes, but not coronary artery disease. Similarly, reminders for statin use were effective for patients with coronary artery disease but not diabetes. Future work should focus on these subtle usability and workflow issues of electronic decision support systems.

Previous studies on the factors affecting the success of reminder systems shed additional light on why our reminder system was successful in some areas but not others. Our reminder system likely benefited from both our efforts to maximize the accuracy of the recommendations30 and the fact that decision support systems are more likely to be used for conditions that are the focus of performance measurement, such as for diabetes and coronary artery disease care.31 However, physicians report that reminder systems often lengthen office visits,32 and this likely limited the effectiveness of our intervention given that lack of time was reported by physicians in our study as a significant barrier to guideline adherence. In addition, the concurrent use of paper forms in our study clinics likely also limited the effectiveness of our electronic intervention, as physicians were possibly less focused on the electronic record during the office encounter.30

Our study has several limitations. To date, a minority of ambulatory practices in the United States are using electronic medical record systems with integrated laboratory and medication data; however, their use is routine in many other countries and there are active efforts to increase their use in the United States.4 In addition, we had to rely on physician data entry into the electronic record for some measures. The low rates of baseline performance of dilated eye examinations likely reflect deficiencies in documentation rather than abnormally low adherence for this measure. We did not assess outcomes of care, although most of the process measures that we assessed have been demonstrated to result in improved outcomes in controlled trials, and outcome differences may take years to identify.

We used physician report to assess how often our reminders were noticed, which would be more rigorously assessed by direct methods of studying eye movement tracking. We did not assess physician-reported barriers to guideline adherence for specific aspects of care, such as for appropriate medication initiation or laboratory testing; however, the general domains that we assessed have been validated in previous studies.26 Finally, our reminder system lacked direct integration with computerized ordering, which could have potentially increased its effectiveness.

Conclusion

We developed an integrated electronic clinical reminder system that improved care for diabetes and coronary artery disease and was well received by physicians. Despite this, quality gaps persist, as our impact on care was limited. Future work should focus both on improving the design of clinical decision support tools and combining these tools with other methods for improving quality.

This work was presented in part at the 2003 Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Conference in Chicago, IL.

Supported by grant 5 U18 HS011046 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as part of the Translating Research into Practice (TRIP) program.

The authors thank the study participants, including the patients and the primary care physicians within the Partners HealthCare System.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Burden of Chronic Diseases and Their Risk Factors. National and State Perspectives, 2004. February 2004. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/burdenbook2004./ Accessed May 26, 2005.

- 3.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Quality Report. Available from: http://qualitytools.ahrq.gov/qualityreport/download_report.aspx./ Accessed May 26, 2005.

- 4.Bates DW, Ebell M, Gotlieb E, Zapp J, Mullins HC. A proposal for electronic medical records in U.S. primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Electronic technology: a spark to revitalize primary care? JAMA. 2003;290:259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shea S, DuMouchel W, Bahamonde L. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials to evaluate computer-based clinical reminder systems for preventive care in the ambulatory setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3:399–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt DL, Haynes RB, Hanna SE, Smith K. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 1998;280:1339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stone EG, Morton SC, Hulscher ME, Maglione MA, Roth EA, Grimshaw JM, et al. Interventions that increase use of adult immunization and cancer screening services: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:641–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilasena DS, Lincoln MJ. A computer-generated reminder system improves physician compliance with diabetes preventive care guidelines. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1995:640–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Eccles M, McColl E, Steen N, Rousseau N, Grimshaw J, Parkin D, et al. Effect of computerised evidence based guidelines on management of asthma and angina in adults in primary care: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;325:941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tierney WM, Overhage JM, Murray MD, et al. Effects of computerized guidelines for managing heart disease in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:967–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:213–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan TJ, Antman EM, Brooks NH, Califf RM, Hillis LD, Hiratzka LF, et al. 1999 Update: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction: executive summary and recommendations: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation. 1999;100:1016–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, Daley J, Deedwania PC, Douglas JS, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina—summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina). Circulation. 2003;107:149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Cholesterol Education Program. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maviglia SM, Teich JM, Fiskio J, Bates DW. Using an electronic medical record to identify opportunities to improve compliance with cholesterol guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:531–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. , 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996.

- 18.Murff HJ, Gandhi TK, Karson AK, Mort EA, Poon EG, Wang SJ, et al. Primary care physician attitudes concerning follow-up of abnormal test results and ambulatory decision support systems. Int J Med Inf. 2003;71:137–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin DY, Wci LJ. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1074–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subramanian U, Fihn SD, Weinberger M, Plue L, Smith FE, Udris EM, et al. A controlled trial of including symptom data in computer-based care suggestions for managing patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Med. 2004;116:375–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rousseau N, McColl E, Newton J, Grimshaw J, Eccles M. Practice based, longitudinal, qualitative interview study of computerised evidence based guidelines in primary care. BMJ. 2003;326:314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray MD, Harris LE, Overhage JM, et al. Failure of computerized treatment suggestions to improve health outcomes of outpatients with uncomplicated hypertension: results of a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:324–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerr EA, Gerzoff RB, Krein SL, et al. Diabetes care quality in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System and commercial managed care: the TRIAD study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:272–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stafford RS, Radley DC. The underutilization of cardiac medications of proven benefit, 1990 to 2002. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demakis JG, Beauchamp C, Cull WL, et al. Improving residents' compliance with standards of ambulatory care: results from the VA Cooperative Study on Computerized Reminders. JAMA. 2000;284:1411–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bates DW, Kuperman GJ, Wang S, et al. Ten commandments for effective clinical decision support: making the practice of evidence-based medicine a reality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10:523–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Litzelman DK, Dittus RS, Miller ME, Tierney WM. Requiring physicians to respond to computerized reminders improves their compliance with preventive care protocols. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:311–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patterson ES, Nguyen AD, Halloran JP, Asch SM. Human factors barriers to the effective use of ten HIV clinical reminders. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11:50–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fung CH, Woods JN, Asch SM, Glassman P, Doebbeling BN. Variation in implementation and use of computerized clinical reminders in an integrated healthcare system. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:878–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyons SS, Tripp-Reimer T, Sorofman BA, et al. VA QUERI informatics paper: information technology for clinical guideline implementation: perceptions of multidisciplinary stakeholders. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12:64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]